Abstract

Acoustic radiation force impulse (ARFI) imaging characterizes the mechanical properties of tissue by measuring displacement resulting from applied ultrasonic radiation force. In this paper, we describe the current status of ARFI imaging for lower-limb vascular applications and present results from both tissue-mimicking phantoms and in vivo experiments. Initial experiments were performed on vascular phantoms constructed with polyvinyl alcohol for basic evaluation of the modality. Multilayer vessels and vessels with compliant occlusions of varying plaque load were evaluated with ARFI imaging techniques. Phantom layers and plaque are well resolved in the ARFI images, with higher contrast than B-mode, demonstrating the ability of ARFI imaging to identify regions of different mechanical properties. Healthy human subjects and those with diagnosed lower-limb peripheral arterial disease were imaged. Proximal and distal vascular walls are well visualized in ARFI images, with higher mean contrast than corresponding B-mode images. ARFI images reveal information not observed by conventional ultrasound and lend confidence to the feasibility of using ARFI imaging during lower-limb vascular workup.

I. Introduction

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is one of the leading causes of morbidity and mortality in the United States [1]. Estimates suggest that 79 400 000 American adults (1 in 3) have one or more forms of CVD, and the disease is responsible for approximately 871 500 deaths annually [1]. Three-quarters of CVD mortality are attributable to atherosclerosis. This process involves the narrowing of the arteries caused by the buildup of plaque (fat, cholesterol, calcium) on the interior of arteries. Over time, atherosclerotic plaque can grow large enough to restrict blood flow through the vessel, and the disease forms the etiological basis for coronary artery disease [2], [3], renal failure [4], [5], stroke [6], and peripheral arterial disease (PAD) of the lower extremities [7], [8].

PAD caused by atherosclerotic occlusions that impair arterial blood flow to the lower extremities is a major health problem. The adjusted prevalence of lower-limb PAD is approximately 12 percent, and the disease affects men and women in nearly equal numbers [1]. Approximately one-third of subjects with PAD have typical intermittent claudication (IC), defined as pain in one or both legs during walking that is relieved by rest [9]. Ten percent of PAD cases will require surgical intervention with 1 to 2 percent of cases requiring amputation of the limb. The mortality rate for PAD is similar to breast and colorectal cancer with a 5-year mortality rate of 30% and a 10-year mortality rate of 50% [8], [10].

Of particular clinical interest with PAD patients is the prevention of acute lower-limb ischemia. Acute lower-limb ischemia is sudden arterial occlusion due to trauma, arterial thrombosis or embolism, leading to significant or complete loss of blood flow in the affected artery; the amputation rate for acute lower-limb ischemia is between 10% and 30% [11]. Acute lower-limb ischemia can be especially severe in arteries with poor collateral networks, such as the popliteal artery, in which tissue damage can be rapid due to the lack of an alternative blood route. Many acute lower-limb ischemic events are caused by rapid thrombotic occlusion due to plaque rupture [12]. Although plaque rupture mechanics are not fully understood, it is currently believed that soft, lipid-core plaques with thin fibrous caps may be more prone to rupture and thrombosis-formation [13], [14]. As a result, current standards of care are aimed at reducing plaque lipid content (HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors, or statins) and decreasing the likelihood of thrombosis [clopidogrel bisulphate, such as Plavix (Sanofi-Aventis, Bridgewater, NJ), and aspirin]. Imaging modalities that can reliably characterize plaque, especially potentially rupture-prone plaque, may be useful for lower-limb vascular workup and selection of drug therapy.

Common techniques currently used for PAD diagnosis include ankle-brachial index (ABI) measurements, segmented blood pressure recordings, duplex ultrasound, angiography, and cardiovascular magnetic resonance (MR) imaging. The ABI computes the ratio of dorsalis pedis and posterior tibial arterial systolic pressures to the brachial systolic pressure; ABI values below 0.9 show high sensitivity and specificity for detection of occlusions greater than 50% in major peripheral vessels, with values below 0.4 correlating with increased vascular obstruction and severe ischemia [15]. Duplex ultrasound, magnetic resonance angiography (MRA), X-ray angiography, and cardiac MR provide excellent measurements of luminal diameter, identification of stenosis in the lower extremities [16], [17], and, in the case of cardiovascular MR imaging and duplex ultrasound, additional information regarding plaque composition. Most current clinical approaches to the evaluation of the lower-limb vasculature, however, remain limited to identification of stenosis and luminal reduction, rather than plaque characterization.

For several years, elastography has been used to measure the mechanical properties of vascular tissue directly and provide insight into plaque morphology and vulnerability. Intravascular ultrasound (IVUS) elastography provides high-resolution, cross-sectional images of vascular strain induced by vessel pulsation. Regions of low strain in IVUS images have been correlated to calcification in ex vivo experiments [18], in vitro in coronary and femoral arteries [19], and in vivo in coronary arteries [20], [21]. More recently, noninvasive vascular elastography has been demonstrated to differentiate mechanical properties in simulation [22], in vitro and in vivo in the arteries of rats [23], and in vivo in the human carotid artery [24], [25]. Estimates of Young’s modulus can then be computed from these strain maps using a model-based approach [26], [27].

Atherosclerotic imaging has also been realized through radiation-force-based methods. Radiation force results from a transfer of momentum from the propagating ultrasonic wave to the insonifed region and can be described by

| (1) |

where I is the local time-averaged spatial intensity, c is the speed of sound, and α is the material’s attenuation coefficient [28]. Radiation force has been demonstrated to generate propagating waves within tissue; estimates of vascular stiffness can be derived by measuring the velocity of the propagating wave [29], [30].

Radiation force has also been successfully used in acoustic radiation force impulse (ARFI) imaging. Briefly, ARFI imaging uses short-duration, high-intensity acoustic pulses to displace tissue away from the transducer using a localized radiation force [31]; the resulting tissue displacement is estimated using correlation or Doppler-based techniques [31], [32]. ARFI displacement images reflect local tissue mechanical properties and have a spatial resolution comparable to B-mode imaging [33]–[35]. ARFI imaging has previously been demonstrated both in excised arteries [35], [36] and in vivo in the healthy, carotid artery [35]. In our previous investigation into imaging excised vessels, we found that a region of relative high displacement observed in the ARFI image correlated histologically with a lipid-core plaque [35]. We also found that the in vivo healthy carotid artery showed a largely homogeneous response to the ARFI-excitation, with displacements significantly lower than the surrounding tissue [35].

The goal of this study is to evaluate the potential of ARFI imaging for lower-limb arterial workup, and to demonstrate the feasibility of ARFI imaging for imaging healthy and diseased lower-limb arteries. We first describe the adaptation of ARFI imaging techniques for visualizing the popliteal artery, an artery that is 2 to 3 cm deeper than the carotid artery and is a common site for plaque formation and acute lower-limb ischemic events. We present phantom experiments evaluating the method’s ability to distinguish layers and occlusions of different modulus, including compliant occlusions mimicking a soft lipid-pool plaque. Finally, we present preliminary results from an observational pilot study in which both healthy subjects and patients diagnosed with PAD are imaged using ARFI imaging techniques. To the best of our knowledge, this study presents the first in vivo ARFI images of both healthy and diseased lower-limb arteries in humans.

II. Methods

A. ARFI Imaging Methods

ARFI imaging was implemented on a Siemens (Siemens Medical Solutions, USA, Ultrasound Division, Issaquah, WA) SONOLINE Antares ultrasound scanner using the VF7–3 hand-held transducer. Briefly, an ARFI imaging sequence consists of 1 or 2 A-line (reference) pulses acquired at a given location, followed by an extended-duration (excitation) pulse at the same location that displaces tissue a small amount (1 to 10 µm). Following the pushing pulse, an ensemble of A-line (tracking) pulses is acquired at the same location to estimate ARFI-induced motion. A 2-D ARFI image is then formed by repeating this sequence laterally over a given region-of-interest.

ARFI imaging techniques described previously in [35], [37] were modified to facilitate deep vascular imaging. In our prior work [35], pulse durations of 28 µs (7.2 MHz) were used to generate radiation force in vivo in a healthy carotid artery, at an imaging depth of 8 mm from the skin surface. Because the popliteal artery is significantly deeper than the carotid artery (2–3 cm deeper), the excitation pulse-duration was increased to 71 µs, and the excitation transmit frequency lowered to 4.2 MHz to increase the applied radiation force at depth. For popliteal arteries located more than 35 mm from the skin surface, the excitation-pulse duration was increased to 140 µs. A frequency of 7.2 MHz was used in tracking pulses to increase spatial resolution and displacement estimation during tracking.

Prior to data acquisition, the axial imaging focus was adjusted to match the location of the vascular wall; the proximal and distal arterial walls were interrogated separately. The response of each vascular wall to the excitation pulse was observed for approximately 6 ms using a pulse repetition frequency of 9.4 kHz. Two-dimensional ARFI images were formed by electronically translating the aperture 0.5 mm to 1.2 mm across a 14 mm to 28 mm lateral field of view. For each ARFI image acquired, a B-mode image was acquired immediately before the ARFI image to provide anatomical reference and to help correlate features revealed by ARFI with structure observed in the B-mode image.

For in vivo imaging, 2 techniques were used to minimize artifacts from motion external to the applied radiation force. First, clinical sequences were synchronized to vessel diastole to limit artifacts from vessel pulsation. Second, acquisition time for clinical sequences was reduced using parallel-receive beamforming techniques described previously in [37]. Parallel-receive ARFI imaging allows for the simultaneous tracking of 4 locations for every excitation pulse transmitted [37]. With conventional ARFI imaging, approximately 400 ms are required to interrogate a 28 mm field-of-view with 80 excitation beams. Using parallel techniques, the same region can be interrogated with 20 excitation beams in approximately 110 ms. Experience has demonstrated that an approximately 300 ms window exists between the QRS complex and the onset of vessel systole in the popliteal artery. Shortening the acquisition time with parallel-receive ARFI imaging reduces tissue heating and the likelihood of artifacts from vascular and patient motion.

B. ARFI Image Processing and Display

Displacements were computed by correlating the reference pulse with sequentially acquired tracking pulses transmitted after the radiation force excitation pulse. A phase-shift estimator algorithm [38] was used to compute displacements quickly and provide feedback during experimentation. Data were then processed offline using normalized cross-correlation, which improves tracking performance at the expense of increased computational time [39]. Linear motion filters were applied to the processed data to reduce artifacts resulting from physiological and transducer motion [32]. The data are then spatially median filtered using a 0.5 mm (axial) × 0.5 mm (lateral) kernel. The resulting ARFI images reflect the displacement of tissue away from the transducer, with white pixels indicating greater displacement.

Displacements within the lumen were masked using a temporal variance filter because information within the lumen is reflective of radiation-force-induced fluid streaming and blood flow [35], rather than the mechanical properties of vascular tissue. Briefly, the temporal variance filter computes the displacement variance during the last 0.8 ms of tracking, approximately 6 ms after cessation of radiation force. Previous work has demonstrated that tissue displaced from radiation force has largely recovered 5 ms after application of radiation force [32], [40]; relatively low values in temporal variance are expected within tissue following recovery from the applied radiation force. In comparison, displacements within the lumen show a high variance due to fluid streaming, blood flow, and poor correlation. A threshold is then used to select the variance magnitude for masking.

C. Phantom Construction

Tissue-mimicking phantoms were constructed for basic evaluation of the method. All phantoms were made using polyvinyl-alcohol cryogel (PVA-C), a material that has shown to be well suited for vascular modeling in MRI and ultrasound applications [41]–[44]. PVA-C has several properties that make it attractive for vascular modeling: it is nontoxic, able to withstand physiological relevant pressures, and has mechanical properties that can be adjusted during construction [41]. PVA-C rigidity can be modified by increasing the number of freeze-thaw cycles or adjusting the thaw rate [41], [44]. The PVA-C mixture was prepared by dissolving 15 g of polyvinyl-alcohol into 200 mL of water heated to 85°C, and then mixing in graphite powder (4 to 8 µm, Superior Graphite, Chicago, IL) at a 6% by weight concentration to form a scattering medium.

Three vessel types were modeled using PVA-C: homogeneous cylinder phantoms to estimate cryogel modulus, a bi-layer vessel to evaluate layer resolution and contrast, and compliant-plaque phantoms to evaluate the modality’s ability to discriminate a softer material (representing a potential lipid-pool, thrombosis-prone plaque) from a stiffer vascular wall, and also to assess the spatial uniformity of the ARFI-induced response for varying plaque loads. For modulus testing, 4 homogeneous cylinder phantoms were constructed using 5 freeze-thaw cycles, 4 freeze-thaw cycles, 3 freeze-thaw cycles, and 2 freeze-thaw cycles. The outer and inner diameters of the modulus-test phantoms were 7 mm and 11 mm, respectively. The bi-layer phantom consisted of a 0.8 mm-thick outer wall and a 2.2 mm-thick inner wall constructed with 5 freeze-thaw cycles and 3 freeze-thaw cycles, respectively.

To evaluate performance as a function of plaque size, compliant-plaque phantoms were made with occlusion sizes of 12%, 44%, and 80% diameter stenosis to model increasing plaque load. For the compliant-plaque phantoms, a 3 mm homogeneous wall of 5 freeze-thaw cycles was constructed with embedded plaques made using 2 freeze-thaw cycles. A freeze-thaw cycle consisted of 12 h of freezing at −18°C and 12 h of thawing in a water bath at 23°C.

D. Measurement of Cryogel Modulus

The PVA-C modulus was determined by pressure-diameter tests of the 4 homogeneous phantoms. Fig. 1 shows a schematic of the measurement system. Each phantom was mounted in a closed-loop pressure system and then pressurized with a gravity head. Changes in internal pressure inside the vessel were measured using a Millar pressure catheter (Millar Instruments, Houston, TX). Changes in external phantom diameter were measured using conventional ultrasound (10 MHz). Diameter change was then plotted as a function of pressure. The Young’s modulus for each sample, Ey, was estimated using linear elasticity theory [45]:

| (2) |

where ro, ri are the initial internal and external radii, do, di are the initial internal and external diameters, and P/(δdo) is the change of pressure versus diameter. The initial internal and external diameters of the phantoms were 7 mm and 11 mm. Each cryogel sample was tested 4 times.

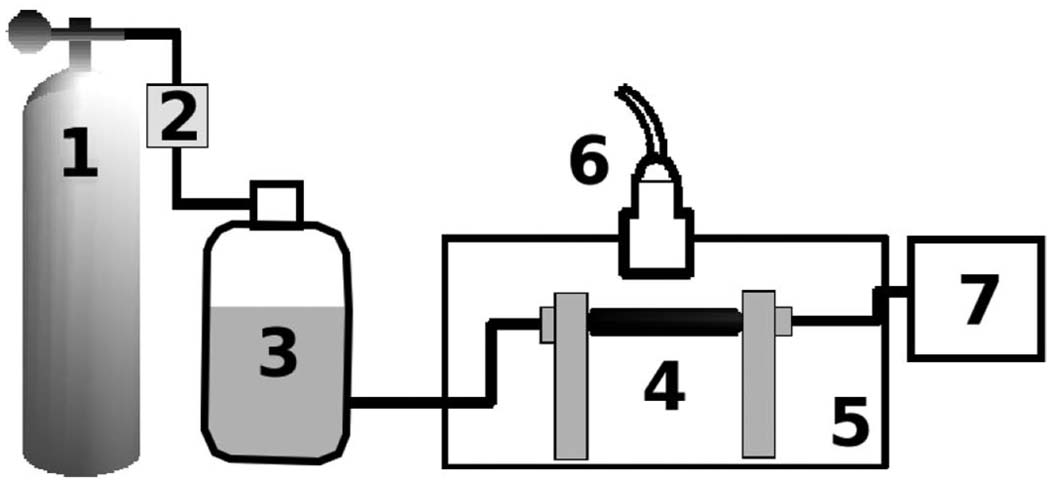

Fig. 1.

Experimental setup for phantom imaging: Compressed air (1) is controlled with a pressure regulator (2) and is used to drive the gravity head (3) that hydrostatically pressurizes mounted vessels. Phantoms (4) are mounted in a water tank (5) and imaged with a transducer mounted on a translation stage (6). Internal vessel pressure is recorded with a Millar pressure catheter and display (7).

E. Phantom Imaging Protocol

Phantoms were mounted in the closed-loop pressure system shown in Fig. 1, pressurized to 16 kPa, and imaged using conventional B-mode and ARFI imaging. B-mode and ARFI images were then analyzed qualitatively to evaluate the visualization of plaque and layer boundaries and quantitatively to compare plaque contrast between the 2 modalities.

Plaque contrast was computed from log-compressed, envelope-detected B-mode data and raw ARFI-induced displacement data with the phantoms imaged lengthwise. Contrast was calculated between selected regions-of-interest (ROIs) inside the plaque and in the adjacent wall outside the plaque. Selected ROIs inside and outside the plaque were identical in size and shape, and the same ROIs were used for both B-mode and ARFI imaging data. Contrast was then computed using the following equation:

| (3) |

where Po and Pb are the mean ARFI and B-mode pixel values inside and outside the plaque.

ARFI-induced displacement values were then compared with measured cryogel moduli to determine the accuracy of using ARFI-induced displacement as a surrogate measurement of material stiffness. Mean ARFI-induced displacements and standard deviations were calculated for each phantom to evaluate spatial-uniformity.

F. Patient Population and In Vivo Imaging Protocol

In an ongoing study approved by the Duke University Institutional Review Board, in vivo data were acquired from the left and right popliteal arteries of 8 healthy, normal volunteers (5 male, 3 female, mean age 48, range 40–58) and 10 patients (7 male, 3 female, mean age 57, range 45–74) currently undergoing treatment for lower-limb peripheral arterial disease. All subjects gave informed consent as outlined by the Duke University Institutional Review Board. In some cases, results were only collected for one artery due to protocol time constraints.

A registered vascular sonographer obtained ankle-brachial systolic pressures according to a standardized protocol. Blood pressure cuffs were applied to both arms and both ankles, and systolic pressure was recorded from the brachial artery of each arm, the posterior tibial artery, and the dorsalis pedis of each leg using an 8 MHz Doppler pen probe. The ABI was computed by dividing the systolic pressure in the posterior tibial artery and the systolic pressure in the dorsalis pedis artery by the highest of the 2 brachial systolic pressures. The lowest ABI value between the tibial artery and the dorsalis pedis is reported for each leg.

Subjects were scanned in the prone position, using a Siemens VF7–3 transducer (Siemens Medical Solutions, USA) oriented to provide a longitudinal view of the popliteal artery. The popliteal artery was located by the sonographer using duplex ultrasound and the popliteal-tibial bifurcation as a landmark. B-mode and ARFI imaging data were then collected from the proximal and distal popliteal walls in both legs using diastolic electrocardiogram (ECG) gating. To assess the potential impact of vascular physiological motion on ARFI imaging data, RF data were acquired using tracking-pulse-only sequences. Plaque observed in the B-mode image was annotated by the sonographer to facilitate comparison between the B-mode and ARFI displacement image.

ARFI images were analyzed qualitatively to assess vascular boundary definition and resolution of disease. Vascular image quality was also assessed by calculating image contrast between vascular tissue and the tissue immediately above or below the wall. ROIs were selected within an identifiable intima-media region on the B-mode image, while blinded to the ARFI image. Vascular ROIs were selected to contain as much as the intima-media as possible, while still remaining within the borders of the vessel. Selected ROIs outside the intima-media were identical in shape and size as those selected within the artery and were located either immediately above the vascular wall ROI (for proximal walls) or immediately below the vascular wall ROI (for distal walls). The same ROIs were used in both B-mode and ARFI images. Contrast was computed from mean displacements occurring 0.7 ms following force cessation using the formula described in (3).

G. Thermal and Mechanical Safety

Because ARFI imaging uses high-intensity, long-duration excitation pulses, heating and mechanical effects associated with ARFI imaging sequences are potentially nontrivial. Heating effects associated with ARFI imaging have been described extensively in earlier reports [46], [47]. For sequences used in this study, a simulation of tissue heating was performed using a previously validated tissue-heating model [46], [47]. Maximum heating associated with the described sequences was determined to be 0.38°C in tissue. Peak in vivo heating is expected to be significantly lower due to perfusion.

Excitation pulses used in this study have high mechanical indices (MI), ranging from 1.5 to 2.3, which is slightly above the FDA-recommended limit of 1.9 for diagnostic imaging [48]. No contrast agents are used with ARFI imaging, and unlike lung or intestinal tissue, thigh muscle and thigh vasculature are not expected to contain gas microbubbles. Risk of cavitation in vivo is expected to be much lower due to the relatively high attenuation found in muscle (0.7–2.5 dB/cm/MHz) and fat (0.6 dB/cm/MHz), the 2 dominant tissue types found in the thigh [49]–[51].

III. Results

A. Measurement of Cryogel Modulus

Fig. 2 shows the measured pressure data plotted as a function of the change in external diameter for the 4 homogeneous phantoms. From (2), the estimated Young’s moduli are 19.7 ± 1.8 kPa, 36.9 ± 1.1 kPa, 51.3 ± 7.0 kPa, and 121.8 ± 12.9 kPa for the 2-cycle, 3-cycle, 4-cycle, and 5-cycle phantoms.

Fig. 2.

Diameter change plotted as a function of pressure for 4 homogeneous phantoms made using PVA-C with 2 freeze-thaw cycles, 3 freeze-thaw cycles, 4 freeze-thaw cycles, and 5 freeze-thaw-cycles.

B. Cryogel Phantom Results

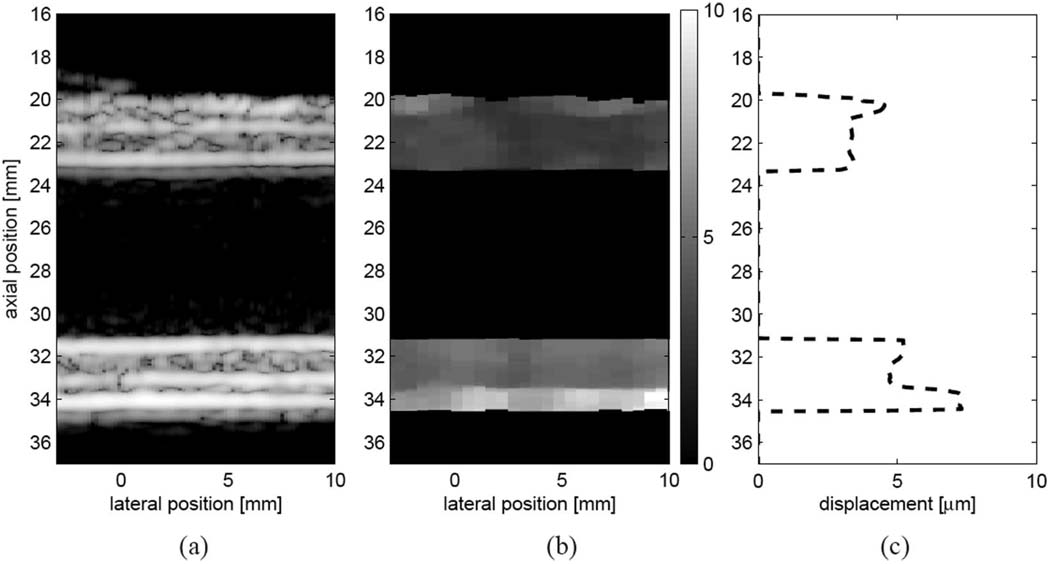

Fig. 3 shows reference B-mode (a) and ARFI (b) images of the bilayer phantom mounted lengthwise and pressurized to 16 kPa. Fig. 3(b) shows the measured ARFI-induced displacement 0.5 ms after force cessation with the tracking and excitation beam focus set to the distal wall. Thin regions of high displacement are observed in the outer sections of the proximal and distal walls, corresponding to the more compliant, 3-cycle outer layer. For the proximal wall, the mean ARFI displacement in the outer layer is 4.6 ± 0.7 µm while the mean ARFI displacement in the inner layer is 3.3 ± 0.3 µm, suggesting a stiffness ratio of approximately 1.4:1. For the distal wall, the mean ARFI-induced displacement in the outer layer is 7.0 ± 0.8 µm while the mean ARFI displacement in the inner layer is 4.9 ± 0.4 µm, suggesting a stiffness ratio of approximately 1.4:1. Displacements are slightly larger in the distal wall due to the increased radiation force from focusing the excitation beam on the distal wall. The expected modulus ratio based on pressure-diameter testing is 121.8 kPa : 36.9 kPa, or 3:1.

Fig. 3.

Matched (a) B-mode image, (b) ARFI image (0.7 ms following force cessation), and (c) laterally-averaged displacement for the bilayer phantom at 16 kPa. ARFI images show displacement away from the transducer in microns.

Fig. 3(c) plots the lateral average of the displacement data as a function of depth from the same data set, revealing that good spatial registration exists between the layers revealed in the ARFI displacement image and the actual layers of the constructed phantom. The ARFI images suggest an average outer proximal wall thickness of 0.9 mm and an average outer distal wall thickness of 1.0 mm, which compares favorably to the 0.8 mm wall thickness specified in the phantom. The inner proximal wall thickness (1.9 mm) and distal wall thickness (2.0 mm) also appear to compare favorably to the 2.2 mm layer thickness specified in the phantom.

Fig. 4 shows cross-sectional (left-side) and lengthwise (right-side) B-mode and ARFI displacement images (0.5 ms following force cessation) for the 3 occlusion phantoms. For all 3 occlusion phantoms, the compliant plaque section (19.7 kPa) displaces approximately 3 times more than the stiffer wall (121.8 kPa). Wall-plaque boundaries are well defined in both cross-sectional and lengthwise ARFI images, but they are poorly visualized in the matched B-mode images. Mean plaque displacement values from the lengthwise scans were computed to be 11.5 ± 2.8 µm, 9.2 ± 2.3 µm, and 9.4 ± 1.6 µm for the 12%, 44%, and 80% occlusion phantoms. Mean wall displacement from the lengthwise scans was computed to be 2.7 ± 0.3 µm, 2.8 ± 0.4 µm, and 3.4 ± 0.7 µm. Mean ARFI imaging plaque contrast for the 3 phantoms was found to be 10.5 dB (range 8.9 dB to 12.6 dB), a significant improvement over the 1.2 dB (range 0.5 dB to 1.7 dB) observed in the B-mode images.

Fig. 4.

Top row: cross-sectional and longitudinal B-mode and ARFI images (0.7 ms following force cessation) for the 12% occlusion phantom. Middle row: cross-sectional and longitudinal B-mode and ARFI images for the 44% occlusion phantom. Bottom row: cross-sectional and longitudinal B-mode and ARFI images for the 80% occlusion phantom. Displacements are shown in microns. The ARFI images reveal that the more compliant plaque section displaces significantly more than the wall.

C. In Vivo Results

Tables I (8 normal subjects, 12 popliteal arteries) and Table II (10 patients, 17 popliteal arteries) show ABI measurements, mean proximal and distal ARFI-induced displacements, and calculated ARFI and B-mode imaging contrasts for the proximal and distal vascular walls. Mean ABI was found to be significantly lower (P < 0.01) for the patient population (mean = 0.90, range 0.48–1.16) than the normal population (mean = 1.18, range 0.93–1.36). ABI values below 0.9 are associated with lower-limb vascular disease. Approximately half of the lower limbs (n = 8) examined from the patient group had an ABI below 0.9. No lower limbs from the normal group were found to have an ABI below 0.9.

TABLE I.

ABI, Mean ARFI-Induced Wall Displacement, B-Mode, and ARFI Imaging Contrast from Normal Subjects.

| Subject | ABI | ARFI Mean Disp (µm) Proximal/Distal |

B-mode Contrast (dB) Proximal/Distal |

ARFI Contrast (dB) Proximal/Distal |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Figure 5 | 1.20 | 1.0/0.9 | 3.8/4.5 | 12.5/18.0 |

| Figure 9 | 1.30 | 1.1/0.8 | 1.1/3.0 | 4.0/14.8 |

| (NS 1 Right)* | 1.16 | 2.1/1.7 | 1.5/0.9 | 14.5/10.3 |

| (NS 2 Right)** | 1.00 | 2.8/1.6 | 1.5/1.7 | 2.2/9.0 |

| (NS 3 Left) | 0.96 | 2.4/1.3 | 3.1/2.3 | 14.9/8.4 |

| (NS 4 Left) | 1.21 | 1.8/1.4 | 1.5/0.6 | 10.7/13.5 |

| (NS 4 Right) | 1.31 | 1.5/1.3 | 8.3/3.4 | 7.1/9.0 |

| (NS 5 Left) | 1.35 | 3.2/1.3 | 1.8/0.7 | 6.3/4.0 |

| (NS 5 Right) | 1.17 | 2.4/2.0 | 2.0/0.7 | 9.8/8.8 |

| (NS 6 Right) | 0.93 | 2.0/2.5 | 0.8/0.9 | 7.6/5.4 |

| (NS 7 Left) | 1.16 | 3.1/0.7 | 0.4/0.6 | 3.5/1.6 |

| (NS 8 Left) | 1.29 | 2.2/2.7 | 4.5/2.1 | 7.8/4.5 |

| mean | 1.18 | 2.1/1.4 | 2.5/1.9 | 8.4/8.9 |

| std dev | 0.14 | 0.7/0.6 | 2.2/1.4 | 4.2/4.8 |

TABLE II.

ABI, Mean ARFI-Induced Displacement, B-Mode, and ARFI Imaging Contrast from Patients.

| Subject | ABI | ARFI Mean Disp (µm) Proximal/Distal |

B-mode Contrast (dB) Proximal/Distal |

ARFI Contrast (dB) Proximal/Distal |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Figure 6* | 0.48 | 2.2/2.3 | 2.9/0.8 | 9.3/2.4 |

| Figure 7 | 1.04 | 3.1/2.5 | 1.1/3.2 | 6.9/7.3 |

| Figure 8** | 0.78 | 1.1/NA | 6.0/NA | 9.2/NA |

| (NS 1 Left) | 1.04 | 2.2/1.4 | 0.1/2.6 | 3.9/1.7 |

| (NS 1 Right) | 1.16 | 1.5/1.4 | 2.2/0.7 | 14.4/12.1 |

| (NS 2 Left) | 1.15 | 1.6/1.3 | 1.6/4.5 | 1.9/2.8 |

| (NS 2 Right) | 0.88 | 2.1/0.5 | 2.6/3.8 | 9.9/0.5 |

| (NS 3 Left) | 1.03 | 1.9/1.8 | 1.9/0.5 | 5.7/2.3 |

| (NS 3 Right) | 1.02 | 1.7/1.8 | 1.8/1.9 | 6.6/3.2 |

| (NS 4 Left) | 0.74 | 2.1/2.3 | 0.5/2.4 | 8.9/2.5 |

| (NS 4 Right) | 0.71 | 2.2/1.0 | 2.8/0.6 | 15.1/2.6 |

| (NS 5 Left) | 0.72 | 1.6/1.1 | 0.2/0.4 | 5.6/1.1 |

| (NS 5 Right) | 0.84 | 3.3/1.6 | 0.8/0.9 | 8.8/1.7 |

| (NS 6 Left) | 0.97 | 2.5/1.4 | 3.0/1.4 | 12.1/3.8 |

| (NS 6 Right) | 1.05 | 2.3/1.0 | 2.2/2.4 | 4.5/1.0 |

| (NS 7 Right) | 0.54 | 2.1/1.7 | 1.6/0.6 | 4.5/4.1 |

| (NS 8 Right) | 1.08 | 1.8/1.6 | 1.8/1.2 | 3.5/2.8 |

| mean | 0.90 | 2.0/1.5 | 2.0/1.8 | 7.7/3.2 |

| std dev | 0.21 | 0.5/0.5 | 1.4/1.3 | 3.7/2.8 |

NS = not shown; NA = Not available.

Wall contrast and mean displacement calculated from wall only, not within occlusion.

Extensive acoustic shadowing prevented visualization of the distal wall.

No statistical difference was found between the normal and patient group for mean proximal and distal ARFI imaging displacement. Both proximal wall and distal wall ARFI imaging contrast were found to be significantly higher than the contrast calculated from log-compressed B-mode. Mean ARFI imaging proximal contrast from the study was found to be 7.9 dB (range 2.2–15.1 dB) a significant improvement (p < 0.01) over the mean contrast calculated from log-compressed B-mode (mean 2.2 dB, range 0.1–8.3 dB). Mean ARFI distal wall contrast was found to be slightly lower (mean 5.7 dB, range 0.5–14.8 dB) than the mean ARFI proximal wall contrast, but significantly higher (P < 0.05) than the corresponding B-mode contrast (mean 1.8 dB, range 0.4–4.5 dB).

Fig. 5–Fig. 9 show matched B-mode and ARFI images of healthy and diseased popliteal arteries. The B-mode image shows the same field-of-view as the ARFI image. When appropriate, regions of disease have been annotated to aid visualization.

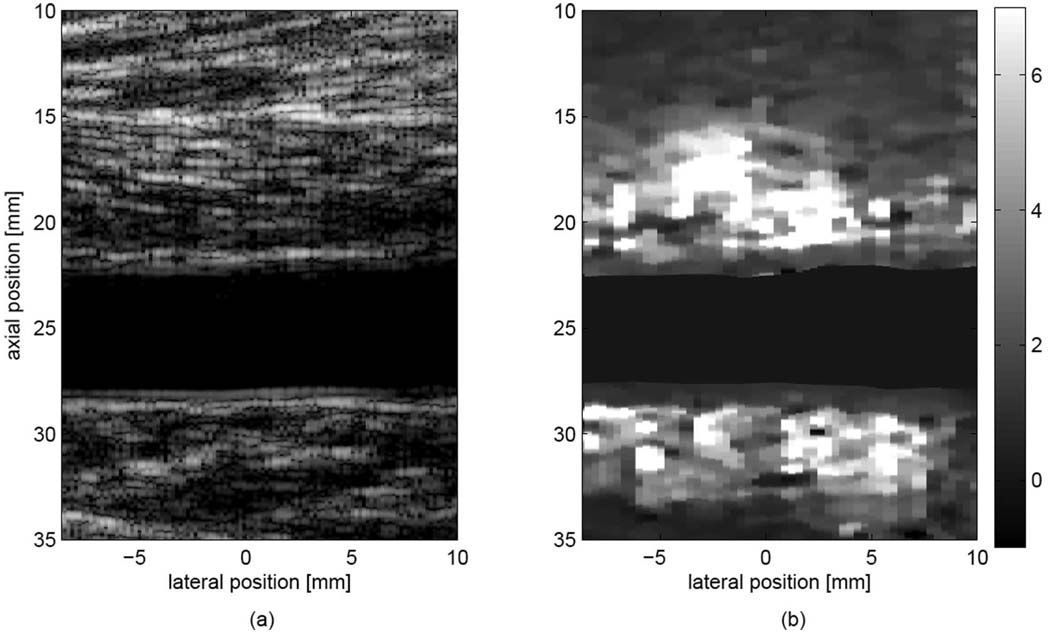

Fig. 5.

Matched (a) B-mode image and (b) ARFI image (0.7 ms following force cessation), showing the popliteal artery of a healthy subject. The ARFI image shows that both vascular walls displace significantly less than nonvascular tissue. Displacements within the lumen have been masked. Displacements are shown in microns.

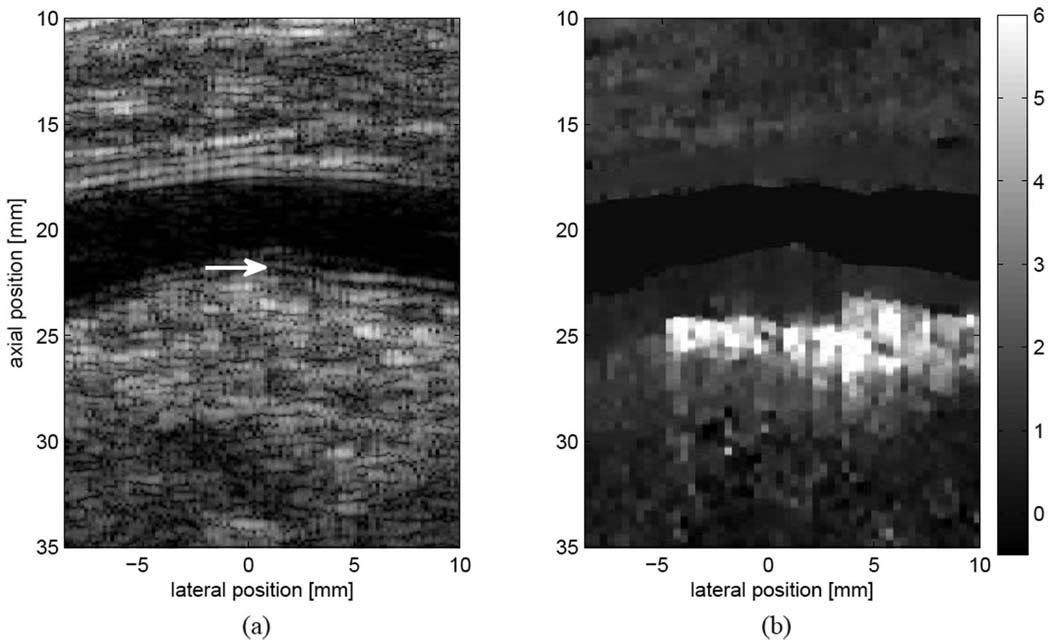

Fig. 9.

Matched (a) B-mode and (b) ARFI images from a subject with normal ABI measurements. Plaque and wall thickening are observed on the distal wall of the popliteal artery (a, marked by a white arrow). The diseased wall is observed to displace less than the surrounding tissue, with a distinct border not suggested by conventional ultrasound. Displacements are shown in microns.

Fig. 5 illustrates a typical result from a normal subject. Matched B-mode (a) and ARFI displacement (b) images are shown from the left popliteal artery of a 40-year-old nonsmoking male. The subject’s ABI values were found to be normal (1.16 for the right leg and 1.20 for the left leg). In the ARFI image, vascular walls are observed to have a relatively homogeneous response, with lower displacement (2 µm) than the surrounding tissue (6–8 µm), suggesting that vascular tissue is stiffer than the surrounding muscle and fascia. Excellent contrast is observed between the vascular walls and the surrounding tissue when compared with the B-mode image, and the adventitia-tissue border is well visualized for both proximal and distal walls.

Plaque was observed in 16 arteries in the study, with 12 focal plaques found on the distal wall, and 4 found on the proximal wall. Two plaques were classified as heterogeneous by ARFI imaging, having a range of displacements varying from 2 µm to 15 µm. The remaining 14 were found to have a spatially uniform response, with displacements generally ranging from 1 µm to 4 µm.

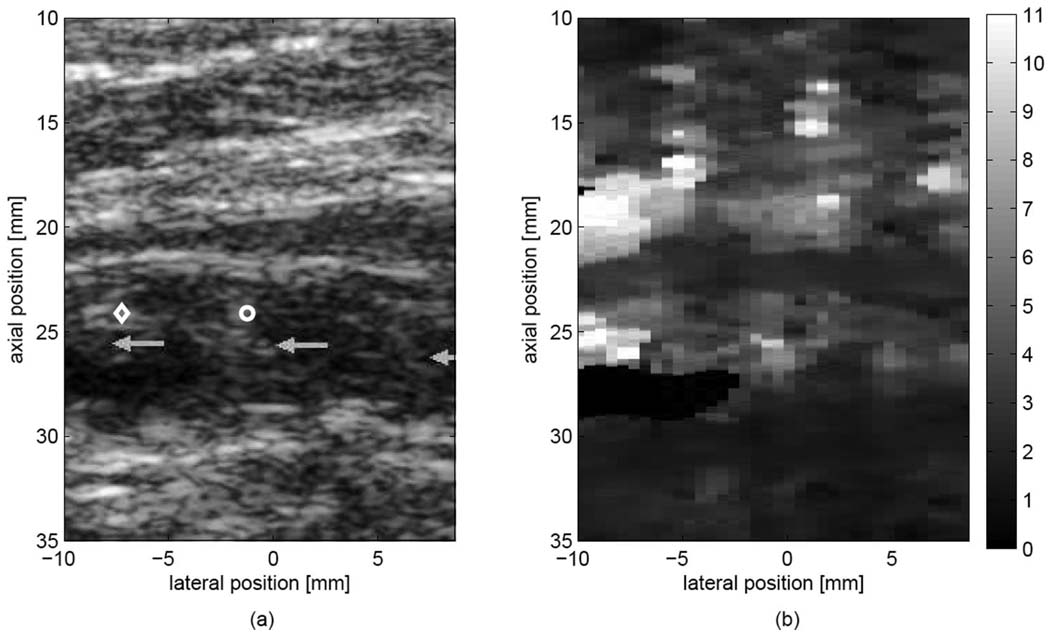

Fig. 6 shows matched B-mode (a) and ARFI displacement (b) images of a plaque classified as heterogeneous by ARFI imaging. The image is from the left popliteal artery of a 70-year-old male smoker with diagnosed peripheral arterial disease. The ABI for the left leg was measured to be 0.48, indicative of moderate-severe obstruction and ischemia. The patient had previously been treated with femoral-popliteal bypass surgery. The B-mode (a) image suggests a nearly completely occluded artery, composed of regions exhibiting mixed echogenicity and echolucency. The corresponding ARFI displacement image (b) reveals a very heterogeneous mixture of displacements within the occlusion (2–12 µm), while the proximal and distal walls exhibit displacements that are both homogeneous and smaller (2–3 µm) than the displacements observed within the occlusion. Note in particular the area marked by a diamond on the B-mode image (a), in which a corresponding region of high displacement (8–12 µm) is observed in the ARFI image (b), suggesting a relatively compliant section within the plaque.

Fig. 6.

Matched (a) B-mode image and (b) ARFI image (0.7 ms following force cessation) from the left popliteal artery of a subject with diagnosed PAD. Displacements within the lumen have been masked. Light gray arrows in (a) mark a heterogeneous echogenic plaque with near-complete occlusion of the popliteal artery. The region marked with a diamond displaces much farther than both the wall and the occlusion, possibly indicating a soft region of the plaque. The region marked with a circle displaces less than the region marked with a diamond, even though both areas are of similar B-mode brightness. Displacements are shown in microns.

Fig. 7 shows B-mode (a) and ARFI displacement (b) images from the right popliteal artery of the same subject as in Fig. 6. The ABI was measured to be 1.04, nonindicative of disease. Plaque is observed on the distal wall, while wall thickening is observed on the proximal wall. The corresponding ARFI image (b) reveals a section of low displacement within the distal wall plaque (4–5 µm), a small band containing slightly higher displacements (6 µm) immediately below, and finally a region of relatively high displacements below both the band and the plaque. The proximal wall is observed to have largely uniform displacements, with high contrast observed between the thickened wall, and relatively more compliant tissue observed above the wall. Comparison of the ARFI displacement image (b) to the matched B-mode image (a) suggests that the narrow displacement band observed distally correlates spatially to the narrow line of slightly hyperechoic tissue marked by the white arrow in the B-mode image, possibly representing a more compliant media-adventitia layer below a stiffer, homogeneous plaque.

Fig. 7.

Matched (a) B-mode and (b) ARFI images from the right popliteal artery of the same subject shown in Fig. 6. Acoustic shadowing from the distal-wall plaque has been marked by white arrows. A region of relatively homogeneous displacements is observed in the plaque, with a narrow band of slightly higher displacements immediately below, followed by relatively high displacements observed in the surrounding tissue. The band spatially registers with the band of slightly higher echogenic tissue (marked by the black arrow) in the matched (a) B-mode image. The image suggests a solid, homogeneous plaque with a slightly more compliant media-adventitia layer immediately below. Displacements are shown in microns.

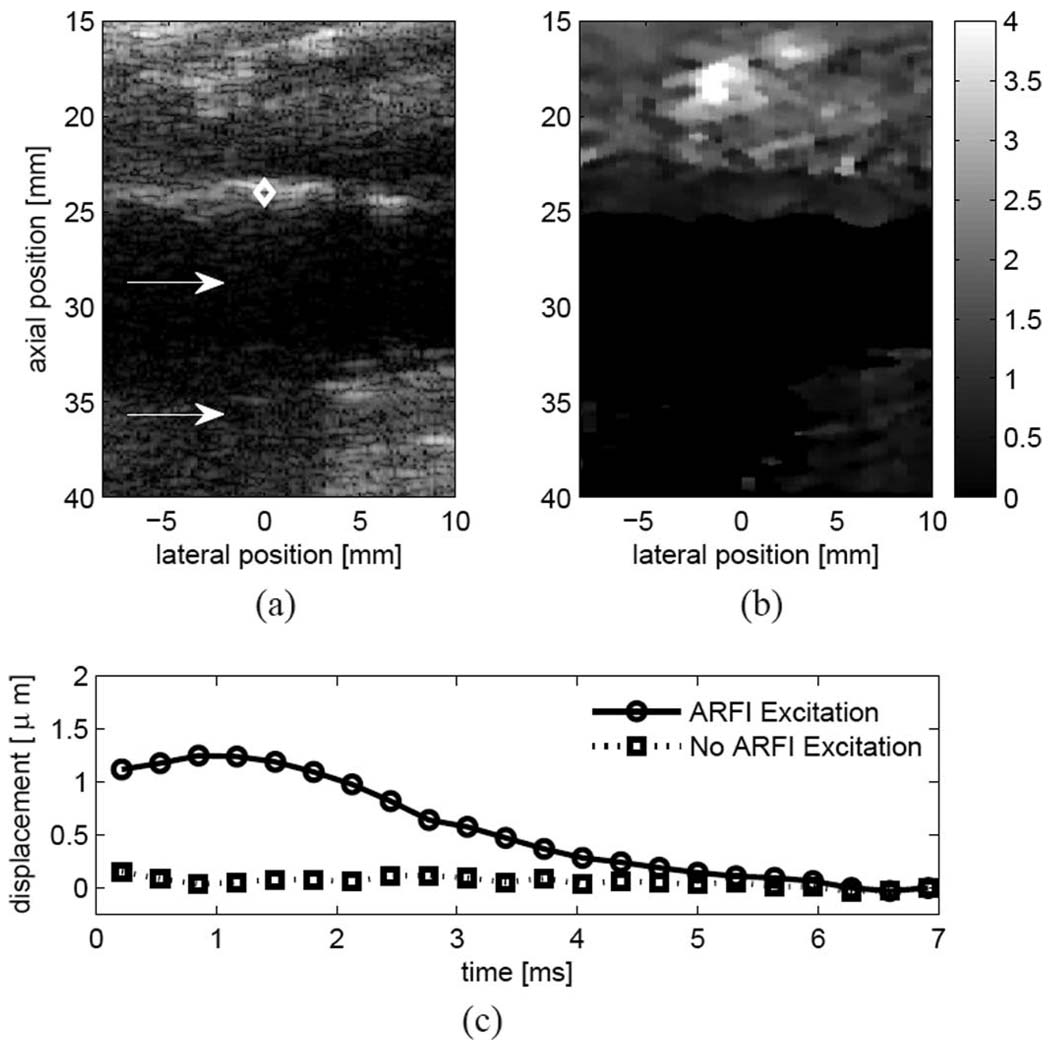

Fig. 8 shows B-mode (a) and ARFI displacement (b) images from the right popliteal artery of a 78-year-old male with diagnosed peripheral arterial disease. The ABI was measured to be 0.78, indicative of mild obstruction. The B-mode (a) image reveals plaque on the proximal wall of the artery, with hyperechoic shadowing observed in the left half of the image (marked by the white arrow), suggesting calcification. In the ARFI image (b), the plaque appears to displace uniformly, exhibiting lower displacement than the underlying tissue, suggesting a largely homogeneous plaque. Note the well-defined tissue-arterial border and that the ARFI image (b) suggests a deeper section of diseased tissue than is visualized within the B-mode image (a). In both images, the distal wall is poorly visualized due to acoustical shadowing from the proximal wall.

Fig. 8.

Matched (a) B-mode and (b) ARFI images from a subject with diagnosed PAD. A hyperechoic plaque is observed on the proximal wall of the popliteal artery with a region of extensive acoustic shadowing immediately below (a, white arrows). The ARFI image shows very low displacements within the plaque suggesting a much stiffer structure. Note that the proximal boundary of the plaque is well resolved in the (b) ARFI image. The (c) plot shows the response in the region marked by the diamond with the amplitude of the ARFI radiation force pulse set to zero (dotted line) and nonzero (solid line). The lack of significant tissue response in the absence of an ARFI excitation pulse suggests that ARFI-induced displacements observed in vascular tissue are due primarily to radiation force, rather than physiological motion. The ratio of displacements suggest a crude signal-to-noise ratio for ARFI images. Displacements are shown in microns.

Fig. 8(c) compares the ARFI-induced response in the wall, marked by a diamond in Fig. 8(a), from a conventional ARFI imaging pulse sequence (solid line), and one in which only tracking pulses are used (dotted line). Because vascular motion can be significant during vessel systole, one potential concern was that even with diastolic ECG gating, observed displacements would be heavily influenced by underlying vascular motion. The lack of a tissue response for the tracking-only sequence (dotted line) after motion filtering lends confidence that measured displacements following an excitation pulse are due primarily to the applied radiation force, rather than physiological motion from vessel pulsation.

Fig. 9 shows B-mode (a) and ARFI displacement (b) images from the left popliteal artery of a 49-year-old male smoker. The ABI was found to be normal for both legs (1.0 for the right leg and 1.30 for the left leg). However, vascular wall thickening and a small occlusion were observed in the distal wall of the popliteal artery and marked by the sonographer in the annotated image (a). The corresponding ARFI image reveals relatively uniform displacements within both the diseased distal wall and the proximal wall, with slightly higher displacements observed in the proximal wall. Both walls exhibit low displacement when compared with the region of high displacement observed immediately below the plaque. The small, uniform displacement observed in the ARFI-induced response suggests that the plaque is stiff and homogeneous. Note that the ARFI image (b) suggests a deeper boundary for the distal plaque that is not well visualized in the B-mode image (a).

IV. Discussion and Conclusion

The ARFI images presented in this paper demonstrate the modality’s potential for clinical imaging of peripheral arteries, specifically for providing mechanical information not directly observed by conventional ultrasound (US). The plaque and bi-layer phantom models illustrate that, for isoechogenic structures, ARFI imaging can reveal underlying mechanical differences in stiffness not readily apparent in matched B-mode images. Results from the bilayer phantom show good agreement between the layer thickness resolved by ARFI imaging and the actual layer thickness specified in the phantom. ARFI images show a significant increase in layer and plaque contrast when compared with the matching B-mode images.

Comparison of ARFI-induced displacements to measured cryogel moduli shows that ARFI imaging tends to underpredict the exact ratio of mechanical stiffness. For example, the expected modulus ratio between the 2 layers in the bilayer phantom is 121.8 kPa: 36.8 kPa, or 3:1. The measured displacement ratio was found to be 1.4:1 for both the proximal and distal walls. For the compliant plaque phantoms, the expected modulus ratio is 121.8 kPa: 19.7 kPa, or 6:1. The measured displacement ratio was found to be approximately 3:1. This is not an unexpected finding, given that previous reports have found that lateral and elevation shearing underneath the tracking beam point spread function leads to underestimation of the induced displacement and that this underestimation is more severe in more compliant materials [52]. However, precise quantitative displacement estimates are likely not necessary for clinical applications, in which relative discrimination between a very compliant tissue (lipid plaque) and a very stiff tissue (arterial wall) may be sufficient to guide disease management. Improvements in tracking beamforming and transducer design may help increase the accuracy of measuring ARFI-induced displacements and thus improve contrast between regions of varying stiffness.

ARFI imaging results from the plaque phantoms indicate that contrast appears to be maintained with increasing plaque load, with well-defined boundaries observed between plaque and wall for all 3 occlusion sizes. Some variability is observed in displacement within the plaque phantoms, particularly for the larger occlusion phantoms where the standard deviation of displacement ranges from 2 to 3 µm. Likely, the cryogel used during construction is not perfectly homogeneous with respect to material stiffness. Accurate depiction of material property over varying plaque load is important because both plaque size and type may be useful in planning clinical intervention. For example, a small, potentially rupture-prone, lipid-pool plaque may require earlier intervention than a larger, mostly fibrotic plaque.

Table I and Table II show ABI measurements for both normal and patient groups. ABIs lower than 0.90 have been shown to be a useful screening tool for lower-limb PAD, showing 95% sensitivity and 98% specificity for detecting angiogram-positive PAD [15]. However, ABI does not indicate plaque vulnerability, nor does it necessarily indicate location of disease within the lower-limb vasculature. For example, in this study, plaque was observed in 4 arteries with normal ABI values.

The in vivo results demonstrate that high-quality, high-contrast ARFI images can be generated in vivo at both the proximal and distal walls of the popliteal artery. ARFI imaging contrast was found to be significantly higher in both walls for both groups than log-compressed B-mode. In general, vascular tissue was found to displace approximately 1 to 3 µm, significantly less than the 4 to 12 µm observed in surrounding tissue. Little difference was observed in the study between the mean ARFI-induced displacement of the normal group and the mean ARFI-induced displacement of the patient group. It is currently unknown what the significance of this observation is given that subject-to-subject variations in tissue attenuation and artery depth make direct comparison of arterial wall displacement difficult at best.

In general, it is observed that tissue-vascular boundaries appear to be well resolved, both for the healthy vascular wall (Fig. 5), and the diseased wall (Fig. 6–Fig. 9) In particular, ARFI displacement images suggest deeper sections of diseased tissue that are not readily visible in the B-mode image (Fig. 8 and Fig. 9). Vascular delineation is especially important for proximal wall imaging, where acoustical clutter can limit the visibility of the proximal intima-media. In fact, clutter can be observed at the proximal wall in most of the clinical images described this study. Although it is unknown to what degree clutter affects the accuracy of tracking proximal wall displacements for ARFI imaging, the well-defined proximal border observed in the corresponding displacement images is encouraging for clinical imaging of the proximal wall and segmentation of vascular boundaries.

Fig. 6 demonstrates the ambiguity that can be encountered with conventional US imaging of atherosclerotic plaque. The matched B-mode image shows an isoechoic plaque with smaller regions of reduced echogenicity. Comparison with the ARFI displacement image reveals that regions of similar echogenicity observed with conventional US can exhibit differential response to the applied radiation force. For example, compare the large displacements, indicative of soft tissue, observed in the upper left section of the occlusion (marked by a diamond in the B-mode image), to the smaller displacements observed in a region of similar echogenicity (marked by a circle). ARFI imaging results are consistent with a heterogeneous plaque that is more compliant than the vascular walls, with an extremely compliant region in the upper left corner of the occlusion that could possibly indicate lipid pooling. Although histological confirmation of plaque morphology is unavailable, the results in this example and the other heterogeneous plaque found in the study were consistent with our previous experiences in excised vessels, in which regions associated with high-relative displacement contained lipid-core plaque [35].

Previously, it was reported in excised vessels that vascular tissue adjacent to a raised focal plaque displaced significantly more in response to ARFI excitation than tissue contained within the raised focal plaque [36]. In this study, we were unable to differentiate presumably stiff, homogeneous plaque from vascular tissue in vivo. Both tissues appear to be stiff in the ARFI image, and both displace very little, approximately 1 to 4 µm. In Fig. 8, for example, no differentiation is seen between plaque containing apparent calcification and adjacent diseased tissue, even though calcified lesions have been shown in the literature to be significantly stiffer than healthy, vascular tissue. Because histology was unavailable for the study, it is difficult to conclude if the lack of differentiation indicates that ARFI imaging is incapable of resolving a highly stiff, calcified section of plaque in vivo, or if the adjacent diseased tissue in the shown example is as stiff as the calcification due to stiffening from atherosclerosis. Regardless, accurate classification of hard, calcified plaque is not as critical for the assessment of lower-limb plaque vulnerability, in which identification of a soft, thin-cap, lipid lesion may be more clinically relevant for thrombus prevention in acute lower-limb ischemia.

Results using tracking-only sequencing suggest that displacements observed within vascular tissue are due primarily to the applied radiation force, rather than vascular physiological motion. The lack of observed displacement following application of a motion filter demonstrates that currently employed linear motion filters described previously are adequate for diastolic vascular imaging [32], [53]. More aggressive motion filtering may be required to study the response during vessel systole in which significant vascular motion is encountered.

The current study has several limitations, some of which may affect the findings. The most significant is the lack of confirmation of observed in vivo findings with histology, because none of the subjects was scheduled for surgical intervention. Imaging patients scheduled for endarterectomy would allow for direct comparison between in vivo ARFI imaging results and actual plaque composition. A second limitation is the PVA-C material used to simulate the wall is both linear and isotropic, and it has a modulus that is lower than the range of static circumferential moduli (120–2000 kPa) reported for arteries [54]. Additionally, lipid-filled regions typically have 1/100 the modulus of vascular tissue, and so a material with a modulus lower than 20 kPa would be a more appropriate choice for a lipid-plaque model [55]. However, considering the high contrast observed between the 20 kPa plaque section and the 121 kPa wall section within the phantom, we believe that ARFI imaging is fully capable of resolving a 1 to 20 kPa lipid core from a 120 to 2000 kPa wall.

Several technical challenges remain before ARFI imaging is realized as a clinical modality for vascular applications. For example, in our experience, popliteal arteries with distal walls superficial to 35 mm are well visualized in the ARFI image, while degradation is observed in both ARFI and B-mode image quality of deeper arteries. Increasing the pulse duration and lowering the frequency of the excitation-pulse may be used to increase the applied radiation force at depth, improving ARFI imaging contrast and SNR. However, this comes at the expense of potentially increasing tissue heating and decreasing spatial resolution, a difficult proposition for imaging millimeter-order structures. Improvements in transducer design and instrumentation may help overcome this problem.

The results presented in this paper are based on the assumption that tissue attenuation within a given ROI is spatially invariant. Considering that the applied radiation force is dependent on the local tissue absorption coefficient and the in situ intensity, a spatially variant absorption coefficient can reduce the uniformity of the insonified field, affecting the measured displacement. Aside from the acoustic shadowing present in Fig. 8, large variations in echogenicity are not observed laterally in tissue below the popliteal artery, a result consistent with a spatially invariant attenuation assumption. Using lower frequency excitation pulses can further decrease the impact of attenuation. Increasing the F-number of the aperture can also increase the spatial uniformity of the insonified field, at the expense of lowering acoustic intensity.

Another challenge for ARFI vascular imaging is that current displacement images reflect qualitative rather than quantitative differences in vascular stiffness. Patient-to-patient variations of tissue attenuation and artery depth impede the utility of direct comparison of vascular displacements. More quantitative descriptions of vascular stiffness could be attained by examining the vascular response through the cardiac cycle, an approach that has shown success for imaging cardiac tissue [56]. However, further investigation into the trade-off between acoustic exposure and increased displacement information as a function of cardiac cycle would be needed. Additionally, measured shear wave velocities induced by ARFI could provide a more quantitative description of vascular stiffness, an approach that has shown promise for hepatic imaging [57].

In summary, we have presented clinical and phantom results from our current investigation, demonstrating the use of ARFI imaging for the assessment of lower-limb vascular disease. To our knowledge, this study represents the first in vivo presentation of lower-limb disease imaged with ARFI techniques. High-resolution, high-contrast ARFI images were observed both in phantoms and in vivo in the popliteal artery. Based on the results so far, we believe that ARFI imaging has the potential to become a valuable tool for lower-limb arterial workup.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Siemens Medical Solutions USA, Inc. for its hardware and system support. We would also like to thank Mike Matthis, Joshua Baker-LePain, and Kathryn Nightingale for their insight.

This research was funded by NIH Grants 1R01HL075485 and 5T32EB001040.

Biographies

Douglas M. Dumont was born in Florence, SC, in 1979. He received his B.S.E. degree from Duke University, Durham, NC, in 2002. He served in the Americorps as a Vista volunteer in 2003. He is currently pursuing his Ph.D. degree in biomedical engineering from Duke University.

His research interests include acoustic radiation-force, based imaging and vascular imaging.

Jeremy J. Dahl was born in Ontonagon, Michigan, in 1976. He received the B.S. degree in electrical engineering from the University of Cincinnati, Cincinnati, OH, in 1999. He received the Ph.D. degree in biomedical engineering from Duke University in 2004. He is currently an Assistant Research Professor with the Department of Biomedical Engineering at Duke University. He is currently researching adaptive ultrasonic imaging systems and radiation force imaging methods.

Elizabeth Miller received her B.S. degree in exercise science from Georgia Southern University, Statesboro, GA, in 1999, and her M.S. degree in exercise physiology from James Madison University, Harrisonburg, VA, in 2001. She came to Duke University Medical Center, Durham, NC, in January 2002 as a clinical exercise physiologist. In September 2003, she became a research coordinator for Frederick Cobb, M.D., and Jason Allen, Ph.D. She has since become a registered clinical exercise physiologist with the American College of Sports Medicine and is a registered vascular specialist with Cardiovascular Credentialing International.

Jason D. Allen received his B.A. (Hons) degree from the Carnegie College, Leeds, England, in 1992 and his M.Ed. degree from Western Carolina University, Cullowhee, NC., in 1996. He completed his Ph.D. degree in vascular and exercise physiology from Louisiana State University, Baton Rouge, LA, in 2001. He went to Duke University Medical Center, Durham, NC, at the end of 2001 as a postdoctoral student and became an assistant professor in August 2004. Dr. Allen now directs the Frederick R. Cobb Non-Invasive Vascular Research Laboratory (http://NIVRL.medicine.duke.edu) and conducts research into vascular and biochemical function/changes with atherogenesis.

Brian J. Fahey was born in Lowell, MA, in 1980. He received the B.S. degree in biomedical engineering from Trinity College in Hartford, CT, in 2002. He received the Ph.D. degree in biomedical engineering from Duke University in Durham, NC, in 2007. Following graduate school, Brian was a fellow in the Biodesign Innovation program at Stanford University in Stanford, CA, where he focused upon the development of novel medical technologies. His research interests include elasticity imaging, finite element method modeling, rapid concept development, and medical device innovation.

Gregg E. Trahey received the B.G.S. and M.S. degrees from the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI, in 1975 and 1979, respectively. He received the Ph.D. degree in biomedical engineering in 1985 from Duke University. He served in the Peace Corps from 1975 to 1978 and was a project engineer at the Emergency Care Research Institute in Plymouth Meeting, PA, from 1980 to 1982. He currently is a Professor with the Department of Biomedical Engineering at Duke University and holds a secondary appointment with the Department of Radiology at the Duke University Medical Center. He is conducting research in adaptive phase correction, radiation force imaging methods, and 2-D flow imaging in medical ultrasound.

Contributor Information

Douglas Dumont, Duke University, Biomedical Engineering, Durham, NC..

Jeremy Dahl, Duke University, Biomedical Engineering, Durham, NC..

Elizabeth Miller, Duke University, Medicine, Division of Cardiology, Durham, NC..

Jason Allen, Duke University, Medicine, Division of Cardiology, Durham, NC..

Brian Fahey, Duke University, Biomedical Engineering, Durham, NC..

Gregg Trahey, Duke University, Biomedical Engineering, Durham, NC..

References

- 1.Rosamond W, Flegal K, Friday G, Furie K, Go A, Greenlund K, Haase N, Ho M, Howard V, Kissela B, Kittner S, Lloyd-Jones D, McDermott M, Meigs J, Moy C, Nichol G, O’Donnell CJ, Roger V, Rumsfeld J, Sorlie P, Steinberger J, Thom T, Wasserthiel-Smoller S, Hong Y American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2007 update: A report from the American Heart Association statistics committee and stroke statistics subcommittee. Circulation. 2007 Feb;vol. 115(no 5):69–171. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.179918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chambless LE, Heiss G, Folsom AR, Rosamond W, Szklo M, Sharrett AR, Clegg LX. Association of coronary heart disease incidence with carotid arterial wall thickness and major risk factors: The atherosclerosis risk in communities (aric) study, 1987–1993. Am. J. Epidemiol. 1997;vol. 146(no 6):483–494. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gnasso A, Irace C, Mattioli PL, Pujia A. Carotid intima-media thickness and coronary heart disease risk factors. Atherosclerosis. 1996 Jan.vol. 119(no 1):7–15. doi: 10.1016/0021-9150(95)05625-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Leskinen Y, Salenius JP, Lehtimäki T, Huhtala H, Saha H. The prevalence of peripheral arterial disease and medial arterial calcification in patients with chronic renal failure: Requirements for diagnostics. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2002 Sep.vol. 40(no 3):472–479. doi: 10.1053/ajkd.2002.34885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Leskinen Y, Lehtimäki T, Loimaala A, Lautamatti V, Kallio T, Huhtala H, Salenius JP, Saha H. Carotid atherosclerosis in chronic renal failure—The central role of increased plaque burden. Atherosclerosis. 2003 Dec.vol. 171(no 2):295–302. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2003.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rosvall M, Janzon L, Berglund G, Egström G, Hedblad B. Incidence of stroke is related to carotid IMT even in the absence of plaque. Atherosclerosis. 2005 Apr.vol. 179(no 2):325–331. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2004.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dieter RS, Chu WW, Pacanowski JP, McBride PE, Jr, Tanke TE. The significance of lower extremity peripheral arterial disease. Clin. Cardiol. 2002 Jan.vol. 25:3–10. doi: 10.1002/clc.4950250103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Crique MH, Langer RD, Fronek A, Feigelson HS, Klauber MR, McCann TJ, Browner D. Mortality over a period of 10 years in patients with peripheral arterial disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 1992 Feb.vol. 326:381–386. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199202063260605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cheng KS, Tiwari A, Baker CR, Morris R, Hamilton G, Seifalian AM. Impaired carotid and femoral viscoelastic properties and elevated intima-media thickness in peripherial vascular disease. Atherosclerosis. 2002 Sep.vol. 164(no 1):113–120. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9150(02)00042-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.American Cancer Society. Cancer facts and figures. Atlanta, GA: American Cancer Society; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thrombolysis in the management of lower limb peripheral arterial occlusion–A consensus document. Working party on thrombolysis in the management of limb ischemia. Am. J. Cardiol. 1998 Jan.vol. 81(no 2):207–218. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Malan E, Tattoni G. Physio- and anatomo-pathology of acute ischemia of the extremities. J. Cardiovasc. Surg. (Torino) 1963 Jun.vol. 4:212–225. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Falk E. Why do plaques rupture? Circulation. 1992 Dec.vol. 86(no 6) suppl:30–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schroeder AP, Falk E. Pathophysiology and inflammatory aspects of plaque rupture. Cardiol. Clin. 1996 May;vol. 14(no 2):211–220. doi: 10.1016/s0733-8651(05)70274-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Belch JJ, Topol EJ, Agnelli G, Bertrand M, Califf RM, Clement DL, Creager MA, Easton JD, Gavin JR, Greenland P, Hankey G, Hanrath P, Hirsch AT, Meyer J, Smith SC, Sullivan F, Weber MA. Critical issues in peripheral arterial disease detection and management: A call to action. Arch. Intern. Med. 2003 Apr.vol. 163(no 8):884–892. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.8.884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Huegli RW, Aschwanden M, Bongartz G, Jaeger K, Heidecker HG, Thalhammer C, Schulte AC, Hashagen C, Jacob AL, Bilecen D. Intraarterial MR angiography and DSA in patients with peripheral arterial occlusive disease: Prospective comparison. Radiology. 2006 Jun.vol. 239(no 3):901–908. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2393041574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kallakuri S, Ascher E, Hingorani A, Markevich N, Schutzer R, Hou A, Nahata S, Jacob T, Yorkovich W. Impact of duplex arteriography in the evaluation of acute lower limb ischemia from thrombosed popliteal aneurysms. Vasc. Endovascular Surg. 2006 Jan.–Feb.vol. 40(no 1):23–25. doi: 10.1177/153857440604000103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.de Korte CL, van der Steen AF. Intravascular ultrasound elastography: An overview. Ultrasonics. 2002 May;vol. 40(no 1–8):859–865. doi: 10.1016/s0041-624x(02)00227-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.de Korte CL, Pasterkamp G, van der Steen AF, Woutman HA, Bom N. Characterization of plaque components with intravascular ultrasound elastography in human femoral and coronary arteries in vitro. Circulation. 2000 Aug.vol. 102(no 6):617–623. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.102.6.617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.de Korte CL, Schaar JA, Mastik F, Serruys PW, van der Steen AF. Intravascular elastography: From bench to bedside. J. Interv. Cardiol. 2003 Jun.vol. 16(no 3):253–259. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0854.2003.8049.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schaar JA, De Korte CL, Mastik F, Strijder C, Pasterkamp G, Boersma E, Serruys PW, van der Steen AF. Characterizing vulnerable plaque features with intravascular elastography. Circulation. 2003 Nov.vol. 108(no 21):2636–2641. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000097067.96619.1F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Maurice RL, Ohayon J, Frétigny Y, Bertrand M, Soulez G, Cloutier G. Noninvasive vascular elastography: Theoretical framework. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging. 2004 Feb.vol. 23(no 2):164–180. doi: 10.1109/TMI.2003.823066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Maurice RL, Daronat M, Ohayon J, Stoyanova E, Foster FS, Cloutier G. Non-invasive high-frequency vascular ultrasound elastography. Phys. Med. Biol. 2005 Apr.vol. 50(no 7):1611–1628. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/50/7/020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schmitt C, Soulez G, Maurice RL, Giroux MF, Cloutier G. Noninvasive vascular elastography: Toward a complementary characterization tool of atherosclerosis in carotid arteries. Ultrasound Med. Biol. 2007;vol. 33(no 12):1841–1858. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2007.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ribbers H, Lopata RG, Holewijn S, Pasterkamp G, Blankensteijn JD, de Korte CL. Noninvasive two-dimensional strain imaging of arteries: Validation in phantoms and preliminary experience in carotid arteries in vivo. Ultrasound Med. Biol. 2007 Apr.vol. 33(no 4):530–540. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2006.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Baldewsing RA, de Korte CL, Schaar JA, Mastik F, van der Steen AF. A finite element model for performing intravascular ultrasound elastography of human atherosclerotic coronary arteries. Ultrasound Med. Biol. 2004 Jun.vol. 30(no 6):803–813. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2004.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Baldewsing RA, Mastik F, Schaar JA, Serruys PW, van der Steen AF. Young’s modulus reconstruction of vulnerable atherosclerotic plaque components using deformable curves. Ultrasound Med. Biol. 2006 Feb.vol. 32(no 2):201–210. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2005.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nyborg W. Acoustic streaming. In: Mason W, editor. Physical Acoustics. ch 11. vol. IIB. New York: Academic Press Inc; 1965. pp. 265–331. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang X, Kinnick RR, Fatemi M, Greenleaf JF. Noninvasive method for estimation of complex elastic modulus of arterial vessels. IEEE Trans. Ultrason. Ferroelectr. Freq. Control. 2005 Apr.vol. 52(no 4):642–652. doi: 10.1109/tuffc.2005.1428047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang X, Greenleaf JF. Noninvasive generation and measurement of propagating waves in arterial walls. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2006 Feb.vol. 119(no 2):1238–1243. doi: 10.1121/1.2159294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nightingale KR, Palmeri ML, Nightingale RW, Trahey GE. On the feasibility of remote palpation using acoustic radiation force. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2001 Jul.vol. 110(no 1):625–634. doi: 10.1121/1.1378344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nightingale K, Soo M, Nightingale R, Trahey G. Acoustic radiation force impulse imaging: In vivo demonstration of clinical feasibility. Ultrasound Med. Biol. 2002 Feb.vol. 28(no 2):227–235. doi: 10.1016/s0301-5629(01)00499-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Palmeri ML, Sharma AC, Bouchard RR, Nightingale RW, Nightingale KR. A finite-element method model of soft tissue response to impulsive acoustic radiation force. IEEE Trans. Ultrason. Ferroelectr. Freq. Control. 2005 Oct.vol. 52(no 10):1699–1712. doi: 10.1109/tuffc.2005.1561624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nightingale K, Palmeri M, Trahey G. Analysis of contrast in images generated with transient acoustic radiation force. Ultrasound Med. Biol. 2006 Jan.vol. 32(no 1):61–72. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2005.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Trahey GE, Palmeri ML, Bentley RC, Nightingale KR. Acoustic radiation force impulse imaging of the mechanical properties of arteries: In vivo and ex vivo results. Ultrasound Med. Biol. 2004 Sep.vol. 30(no 9):1163–1171. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2004.07.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dumont D, Behler RH, Nichols TC, Merricks EP, Gallippi CM. ARFI imaging for noninvasive material characterization of atherosclerosis. Ultrasound Med. Biol. 2006 Nov.vol. 32(no 11):1703–1711. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2006.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dahl J, Pinton G, Palmeri M, Agrawal V, Nightingale K, Trahey G. A parallel tracking method for acoustic radiation force impulse imaging. IEEE Trans. Ultrason. Ferroelectr. Freq. Control. 2007 Feb.vol. 54(no 2):301–312. doi: 10.1109/tuffc.2007.244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kasai C, Namekawa K. Real-time two-dimensional blood flow imaging using an autocorrelation technique. IEEE Trans. Ultrason. Ferroelectr. Freq. Control. 1985 May;vol. 32:458–463. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pinton GF, Dahl JJ, Trahey GE. Rapid tracking of small displacments with ultrasound. IEEE Trans. Ultrason. Ferroelectr. Freq. Control. 2006 Jun.vol. 53(no 6):1103–1117. doi: 10.1109/tuffc.2006.1642509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Palmeri M, Frinkley K, Nightingale K. Experimental studies of the thermal effects associated with radiation force imaging of soft tissue. Ultrason. Imaging. 2004;vol. 26(no 2):100–114. doi: 10.1177/016173460402600203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chu KC, Rutt BK. Polyvinyl alcohol cryogel: An ideal phantom material for MR studies of arterial flow and elasticity. Magn. Reson. Med. 1997 Feb.vol. 37(no 2):314–319. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910370230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nadkarni SK, Austin H, Mills G, Boughner D, Fenster A. A pulsating coronary vessel phantom for two- and three-dimensional intravascular ultrasound studies. Ultrasound Med. Biol. 2003 Apr.vol. 29(no 4):621–628. doi: 10.1016/s0301-5629(02)00730-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fromageau J, Brusseau E, Vray D, Gimenez G, Delachartre P. Characterization of PVA cryogel for intravascular ultrasound elasticity imaging. IEEE Trans. Ultrason. Ferroelectr. Freq. Control. 2003 Oct.vol. 50(no 10):1318–1324. doi: 10.1109/tuffc.2003.1244748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fromageau J, Gennisson JL, Schmitt C, Maurice RL, Mongrain R, Cloutier G. Estimation of polyvinyl alcohol cryogel mechanical properties with four ultrasound elastography methods and comparison with gold standard testings. IEEE Trans. Ultrason. Ferroelectr. Freq. Control. 2007 Mar.vol. 54(no 3):498–509. doi: 10.1109/tuffc.2007.273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Timoshenko SP, Goodier JN. Theory of Elasticity. 3rd ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1969. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Palmeri ML, Nightingale KR. On the thermal effects associated with radiation force imaging of soft tissue. IEEE Trans. Ultrason. Ferroelectr. Freq. Control. 2004 May;vol. 51(no 5):551–565. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Palmeri ML, Frinkley KD, Nightingale KR. Experimental studies of the thermal effects associated with radiation force imaging of soft tissue. Ultrason. Imaging. 2004 Apr.vol. 26(no 2):100–114. doi: 10.1177/016173460402600203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.National Council on Radiation Protection and Measurements. Tech. Rep. Vol. 140. Bethesda, MD: 2002. Exposure criteria for medical diagnostic ultrasound, II: Criteria based on all known mechanisms. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Macovksi A. Medical Imaging Systems. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice-Hall; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Evans DH, McDicken WN, Skidmore R, Woodcock JP. Doppler Ultrasound Physics, Instrumentation, and Clinical Applications. New York: John Wiley and Sons; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Angelsen B. Ultrasonic Imaging—Waves, Signals, and Signal Processing. Trondheim, Norway: Emantec AS; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Palmeri ML, McAleavey SA, Trahey GE, Nightingale KR. Ultrasonic tracking of acoustic radiation force-induced displacements in homogeneous media. IEEE Trans. Ultrason. Ferroelectr. Freq. Control. 2006 Jul.vol. 53(no 7):1300–1313. doi: 10.1109/tuffc.2006.1665078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Fahey BJ, Hsu SJ, Wolf PD, Nelson RC, Trahey GE. Liver ablation guidance with acoustic radiation force impulse imaging: Challenges and opportunities. Phys. Med. Biol. 2006 Aug.vol. 51(no 15):3785–3808. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/51/15/013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bergel DH. The static elastic properties of the arterial wall. J. Physiol. 1961 May;vol. 156:445–457. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1961.sp006686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Keeny S, Richardson PD. Stress analysis of atherosclerotic arteries. Proc. IEEE Ninth Ann. Conf. Engineering in Medicine and Biology Soc.; 1987. pp. 1484–1485. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hsu SJ, Bouchard RR, Dumont DM, Wolf PD, Trahey GE. In vivo assessment of myocardial stiffness with acoustic radiation force impulse imaging. Ultrasound Med. Biol. 2007;vol. 33(no 11):1706–1719. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2007.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Palmeri ML, Wang MH, Dahl JJ, Frinkley KD, Nightingale KR. Quantifying hepatic shear modulus in vivo using acoustic radiation force. Ultrasound Med. Biol. 2008 Apr.vol. 34(no 4):546–558. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2007.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]