Abstract

Background: Identification of appropriate markers for predicting clinical benefit with erlotinib in non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) may be able to guide patient selection for treatment. This open-label, multicentre, phase II trial aimed to identify genes with potential use as biomarkers for clinical benefit from erlotinib therapy.

Methods: Adults with stage IIIb/IV NSCLC in whom one or more chemotherapy regimen had failed were treated with erlotinib (150 mg/day). Tumour biopsies were analysed using gene expression profiling with Affymetrix GeneChip® microarrays. Differentially expressed genes were verified using quantitative RT–PCR (qRT–PCR).

Results: A total of 264 patients were enrolled in the study. Gene expression profiles found no statistically significant differentially expressed genes between patients with and without clinical benefit. In an exploratory analysis in responding versus nonresponding patients, three genes on chromosome 7 were expressed at higher levels in the responding group [epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), phosphoserine phosphatase (PSPH) and Rap guanine nucleotide exchange factor 5 (RAPGEF5)]. Independent quantification using qRT–PCR validated the association between EGFR and PSPH overexpression, but not RAPGEF5 overexpression, and clinical outcome.

Conclusions: This study supports the use of erlotinib as an alternative to chemotherapy for patients with relapsed advanced NSCLC. Genetic amplification of the EGFR region of chromosome 7 may be associated with response to erlotinib therapy.

Keywords: biomarkers, epidermal growth factor receptor, erlotinib, gene expression, non-small-cell lung cancer, PCR

introduction

Erlotinib, an orally available epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) tyrosine-kinase inhibitor (TKI), significantly prolongs survival and produces significant symptom and quality-of-life benefits compared with best supportive care in unselected patients with relapsed non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) [1, 2]. In a large, phase III, placebo-controlled study (BR.21), erlotinib produced a survival benefit across all patient subgroups studied [1].

Considerable research has been undertaken to identify molecular markers that predict sensitivity to EGFR TKIs. The most extensively studied potential markers are EGFR protein expression level, EGFR gene copy number and EGFR gene mutations [3–7]. Post hoc molecular analyses of samples from the BR.21 study found increased EGFR gene copy number to be the only significant molecular predictor of a differential survival benefit from treatment with erlotinib [8]. Recently, a prospective biomarker analysis carried out for erlotinib as part of the phase III, randomised, placebo-controlled Sequential Tarceva in Unresectable NSCLC (SATURN) study showed that maintenance erlotinib produced a progression-free survival (PFS) benefit in all patients, irrespective of the status of candidate biomarkers investigated; however, those with EGFR mutations had a particularly notable extension of PFS [9].

Identification of molecular markers that predict sensitivity to erlotinib should facilitate the appropriate selection of NSCLC patients who are most likely to benefit from treatment. The primary objective of the phase II Marker Identification Trial (MERIT; BO18279) was to identify candidate genes differentially expressed between patients who did and did not obtain clinical benefit from erlotinib therapy.

methods

study design and patients

This was a nonrandomised, open-label, multicentre, phase II study. Patients aged ≥18 years with histologically or cytologically confirmed stage IIIb/IV NSCLC in whom one or more prior chemotherapy regimen had failed or who were unsuitable or unwilling to undergo such therapy were eligible for study inclusion. Patients were required to have tumour tissue accessible for tissue sampling by bronchoscopy; measurable disease according to RECIST [10]; Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status of zero to two; life expectancy of ≥12 weeks; adequate renal, hepatic and haematological function and an interval of ≥4 weeks since previous surgery or radiotherapy. Patients were excluded from the study if they had any condition likely to cause undue risk during erlotinib therapy or bronchoscopy; any previous malignancy in the past 5 years (other than successfully treated cervical or skin carcinoma); brain metastases or spinal cord compression that had not been successfully treated or previous treatment with an EGFR-targeted therapy.

Patients received oral erlotinib 150 mg once daily until disease progression, unacceptable toxicity or death.

The study was carried out according to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and was overseen by Independent Ethics Committees at the participating centres. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients.

study design

efficacy and safety evaluations.

Tumour size was measured by computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging at study entry, 6-week intervals until week 24, and every 12 weeks thereafter, with responses assessed using RECIST [10]. Complete responses (CRs) or partial responses (PRs) were confirmed by repeated assessments ≥4 weeks apart at any time during the treatment period. Disease control was defined as an objective response (CR/PR) or maintenance of stable disease (SD) for ≥6 weeks after study entry. Clinical benefit was defined as an objective response (CR/PR) or maintenance of SD for ≥12 weeks after study entry. PFS was defined as the time from study entry to the time of documented disease progression or death (patients still benefiting at the time of analysis were treated as censored observations). Adverse events were graded according to the National Cancer Institute—Common Toxicity Criteria, version 3.0.

biomarker analyses.

Patients underwent bronchoscopy within 2 weeks before the start of treatment to provide two tumour samples. If available, diagnostic tumour blocks were to be provided within 6 weeks of study entry.

gene expression profiling.

One tumour biopsy sample from each patient was snap frozen immediately in liquid nitrogen. At the reference laboratory, initial RNA quality was determined by extraction of total RNA from one unstained, unfixed tissue cryosection and analysed using the Agilent RNA 6000 Pico Chip (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA). If at least one residual ribosomal RNA peak was visible on the electropherogram (RNA quality criterion) and sufficient numbers of tumour cells were present in the selected sections (histopathological criterion), laser capture microdissection (LCM) of tumour cells was carried out. Tumour cells from the cryosections were captured using the PixCell II LCM instrument (Arcturus) on to CapSure Macro LCM Caps (Arcturus, MDS Analytical Technologies, Sunnyvale, CA) as described by the manufacturer. Immediately after LCM, RNA was extracted from the sample using the RNeasy Mini Kit (QIAGEN GmbH, Hilden, Germany). A two-cycle linear amplification protocol (Affymetrix UK Ltd, High Wycombe, UK) was used for target labelling because of the relatively low yields of RNA from LCM. The samples were then analysed using GeneChip® gene expression profiling technology with the human genome (HG) U133A chip according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Affymetrix), to assess the level of messenger RNA (mRNA) transcripts of the entire genome. The HG-U133A chip consists of 22 283 ‘probe sets’, covering ∼13 298 genes. Samples of adequate quality for statistical comparison were selected following quality control using Affymetrix software MAS 5.0.

quantitative RT–PCR analysis.

On the basis of an exploratory analysis of the Affymetrix gene expression profiling data, three genes, all located on chromosome 7, were identified for independent assessment of mRNA transcript levels using quantitative RT–PCR (qRT–PCR): EGFR, phosphoserine phosphatase (PSPH) and Rap guanine nucleotide exchange factor 5 (RAPGEF5).

RNA was extracted from fresh frozen tumour tissue and where available from formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tumour samples, as described above. Complementary DNA was synthesised using SuperScript™ III First-strand Synthesis SuperMix for qRT–PCR (Invitrogen GmbH, Karlsruhe, Germany), according to the manufacturer’s instructions, but without inclusion of an ribonuclease H digest. Quantitative PCR was carried out using TaqMan® Gene Expression Assays on an ABI PRISM® 7900HT Sequence Detection System (Applied Biosystems), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The gene expression assays used (Hs01076086_m1 [EGFR], Hs00190154_m1 [PSPH] and Hs00920287_m1 [RAPGEF5]) were chosen so that the primers and probes crossed exon boundaries or were within the Affymetrix GeneChip® probe sequence of interest. Two housekeeping genes were included as endogenous controls: β2-microglobulin (β2M) (Assay Hs9999907_m1) and hypoxanthine phosphoribosyltransferase 1 (Assay Hs9999909_m1). All runs included a calibrator sample and a standard curve, and all samples were measured in triplicate. Relative quantification was carried out using the ΔCt method using β2M as reference gene [11].

FISH analyses.

The second tumour biopsy sample obtained from each patient by bronchoscopy was fixed in formalin immediately after surgery and embedded in paraffin. EGFR gene copy number was assessed by FISH, as described by Schneider et al. [12]. Samples with high gene copy number (high polysomy/gene amplification) were classed as FISH positive [4]. FISH analyses were also carried out on diagnostic tumour blocks, if available.

EGFR and KRAS gene mutation analysis.

Please refer to supplemental section (available at Annals of Oncology online) for details of EGFR and KRAS mutation analyses.

statistical analysis of gene expression profiling data.

This study was powered to realistically identify ‘straightforward’ markers of clinical benefit with erlotinib. Similar differential expression levels were observed for genes proposed to be predictive of response to gefitinib [13].

The power calculation was conducted following a simulation scheme as described by Wang et al. [14], assuming (i) a set of five straightforward markers of clinical benefit were present (with an area under the curve of 90%) and (ii) that 25% of patients would derive clinical benefit from erlotinib. A false discovery rate (FDR) cut-off of 5% was used to account for multiple testing instead of a fixed P value cut-off. Our simulation-based estimation of the probability of detecting the set of all five markers with a sample size of 125 was very close to one (>95%). On the basis of an assumed 50% success rate in obtaining the required quality and quantity of RNA from tumour samples, target recruitment was set at 250 patients.

Gene expression data were normalised using the robust multi-array analysis algorithm library [15], with identification and removal of a batch effect [16]. The Affymetrix MAS5 algorithm was used to identify probe sets below the detection limit, and probe sets with ‘absent’ or ‘marginal’ status in all patients were removed from further analysis. Consensus clustering, using an unsupervised clustering algorithm [17], was applied to the gene expression dataset to identify patients with similar overall expression profiles. A linear model was fitted independently to each probe set, with normalised expression level as dependent variable. In the primary analysis model for clinical benefit versus no clinical benefit, covariates included clinical benefit category, histology, ethnicity, sex, RNA integrity number, smoking status and disease stage. The statistical test of differences in expression level was assessed using a FDR criterion to account for multiple statistical testing [18]. A FDR of <0.3 was set as the cut-off.

For qRT–PCR data, boxplot graphical displays were used for the analysis, with ΔCt distribution on the y-axis versus RECIST response category on the x-axis.

results

patients

A total of 264 patients from 26 centres in 12 countries were enrolled in the study over a 12-month period (Table 1). A total of 102 tumour samples (the ‘primary analysis set’) were suitable for gene expression profiling using Affymetrix GeneChip® microarrays. qRT–PCR results were obtained from 75 patients; among these, 66 also had an Affymetrix profile. The demographics and clinical characteristics of the patients with Affymetrix gene expression profiles and qRT–PCR results were generally similar to those of the entire study population (Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline patient and disease characteristics

| Characteristic | All patients | Primary analysis set (patients with Affymetrix gene expression analyses) | Patients with qRT–PCR analyses |

| n | 264 | 102 | 75 |

| Median age; years (range) | 61 (32–85) | 62 (39–85) | 62 (39–85) |

| Gender; n (%) | |||

| Male | 184 (70) | 77 (75) | 56 (75) |

| Female | 80 (30) | 25 (25) | 19 (25) |

| Histology; n (%) | |||

| Adenocarcinoma | 107 (41) | 35 (34) | 27 (37) |

| Squamous cell carcinoma | 101 (38) | 50 (49) | 34 (45) |

| Large cell carcinoma | 12 (5) | 2 (2) | 2 (3) |

| Other | 44 (17) | 15 (15) | 12 (16) |

| ECOG PS; n (%) | |||

| 0 | 33 (13) | 7 (7) | 7 (9) |

| 1 | 169 (64) | 69 (68) | 45 (60) |

| 2 | 62 (23) | 26 (25) | 23 (31) |

| Disease stage; n (%) | |||

| IIIb | 69 (26) | 27 (26) | 22 (29) |

| IV | 195 (74) | 75(74) | 53 (71) |

| Ethnicity; n (%) | |||

| Caucasian | 162 (61) | 65 (64) | 51 (68) |

| Asian | 101 (38) | 37 (36) | 24 (32) |

| Other | 1 (<1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Smoking history; n (%) | |||

| Never | 72 (27) | 20 (20) | 12 (16) |

| Current | 71 (27) | 33 (32) | 24 (32) |

| Former | 121 (46) | 49 (48) | 39 (52) |

| Prior chemotherapy regimens for advanced NSCLC; n (%) | |||

| 0 | 58 (22) | 26 (25) | 19 (25) |

| 1 | 134 (51) | 50 (49) | 36 (48) |

| ≥2 | 68 (26) | 25 (25) | 20 (27) |

| Unknown | 4 (2) | 1 (1) | 0 (0) |

qRT–PCR, quantitative RT–PCR; ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; PS, performance status; NSCLC, non-small-cell lung cancer.

clinical outcomes

Among 264 patients, the overall response rate (ORR) was 13.6% (36 PR and 0 CR). SD lasting ≥6 weeks was achieved in 80 patients (30.3%), to produce a disease control rate (DCR) of 43.9%. A total of 47 (17.8%) patients had SD lasting ≥12 weeks, producing a clinical benefit rate of 31.4%. Compared with the overall study population, a lower ORR and DCR were observed in the subset of patients with Affymetrix gene expression profiles (6% and 36%, respectively) and the subset of patients with qRT–PCR results (5% and 36%, respectively).

In the entire study population, median PFS was 11.3 weeks [95% confidence interval (CI) 8–12 weeks] and median overall survival was 7.6 months (95% CI 7–9 months). Median duration of response was 32.1 weeks (95% CI 30–42 weeks).

Erlotinib was generally well tolerated, with no unexpected safety signals reported.

gene expression profiling analyses

A cluster analysis of Affymetrix gene expression profiles identified three clusters, which discriminated between different tumour histology types (supplemental Figure 1, available at Annals of Oncology online) but not clinical benefit status (data not shown). Gene expression profiles from patients who obtained a clinical benefit with erlotinib (6 PR and 15 SD ≥12 weeks) were compared with those from patients who did not benefit [16 SD <12 weeks, 49 progressive disease (PD) and 16 not assessable]. Of the transcripts analysed, none yielded an FDR value <0.3 (supplemental Figure 2, available at Annals of Oncology online), indicating that no strong single predictor of clinical benefit existed. Furthermore, no strong markers of benefit from erlotinib therapy were found in additional exploratory analyses on the basis of different definitions of clinical benefit (including PR + SD versus PD, PFS ≤6 weeks versus PFS ≥24 weeks and PFS overall), response to previous treatment, analysis by gene sets or grouping by biological pathway or chromosomal location.

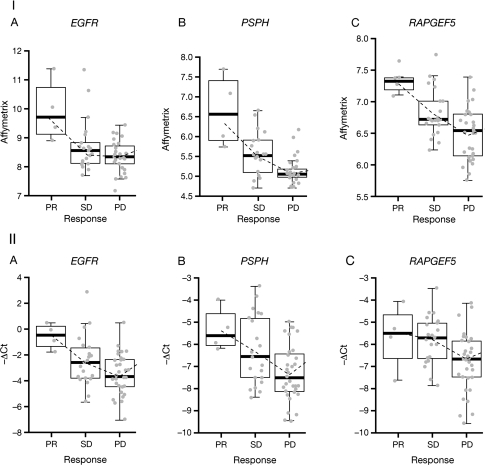

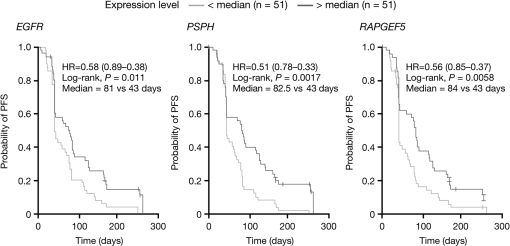

However, three genes were found to be expressed at different levels (FDR <0.3) when comparing the expression profiles of responding patients (six PR) with those of patients with early disease progression (n = 49) or who were not assessable (n = 16): EGFR (7p11.2; FDR = 0.12, P = 0.00002); PSPH (7p12; FDR = 0.07, P = 0.000006) and RAPGEF5 (7p15.3; FDR = 0.07, P = 0.000009) (supplemental Figure 3, available at Annals of Oncology online). Expression of these genes was 2.8-fold, 2.6-fold and 2.0-fold higher, respectively, in responding patients versus those with early disease progression or who were not assessable (Figure 1A–C). Although the control on the number of false positives is not rigorously guaranteed in such exploratory analyses, additional supportive evidence came from analyses showing that higher (greater than median) expression of EGFR, PSPH and RAPGEF5 was significantly associated with longer PFS on erlotinib therapy (P = 0.011, P = 0.0017 and P = 0.0058, respectively; Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Relationships between clinical outcomes and (I) Affymetrix GeneChip® gene expression data and (II) quantitative RT–PCR data with erlotinib therapy for the (A) EGFR gene; (B) PSPH gene and (C) RAPGEF5 gene.

Figure 2.

Kaplan–Meier analyses of progression-free survival (PFS) according to Affymetrix gene expression of EGFR, PSPH and RAPGEF5. Patients were grouped according to those with expression levels below the median and above the median.

qRT–PCR analysis

As observed with Affymetrix profiling, EGFR mRNA levels assessed using qRT–PCR appeared to correlate with response to erlotinib, with higher levels being observed in responders (four PR) compared with those with best response of SD (n = 23) or disease progression (n = 39) (Figure 1IIA). The association between PSPH mRNA levels and clinical outcome with erlotinib observed in the Affymetrix gene expression data was preserved in the qRT–PCR data (Figure 1IIB); however, the association between clinical outcome with erlotinib and RAPGEF5 mRNA levels assessed by qRT–PCR was somewhat poorer than that observed with Affymetrix profiling (Figure 1IIC). In addition, nine patients had mRNA extracted from matching FFPE tumour samples and analysed by qRT–PCR. A high correlation was observed between EGFR mRNA levels in fresh frozen and FFPE tissue (Spearman r = 0.89).

correlation between Affymetrix GeneChip® gene expression data and EGFR FISH status

In EGFR FISH analyses, 53% (21 of 40) of diagnostic samples and 61% (54 of 89) of bronchoscopy samples were FISH positive. There were no tumour responses among patients with EGFR FISH-negative tumours, although sustained disease control was observed in some patients in this group, with clinical benefit rates of 31.6% (six patients) on the basis of diagnostic samples and 28.6% (10 patients) on the basis of bronchoscopy samples. The response rate in the FISH-positive group was 9.5% (two patients) on the basis of diagnostic samples or 11.1% (six patients) on the basis of bronchoscopy samples; the corresponding clinical benefit rates were 28.6% (6 patients) and 31.5% (17 patients).

A significant relationship was observed between EGFR FISH status and both EGFR and PSPH mRNA levels assessed using Affymetrix profiling (P ≤ 0.01 and P < 0.05, respectively), with higher expression of these genes in EGFR FISH-positive tumours. A similar trend was noted when EGFR and PSPH mRNA were assessed using qRT–PCR. There was no significant correlation between EGFR FISH status and RAPGEF5 mRNA levels as assessed by either Affymetrix profiling or qRT–PCR.

EGFR and KRAS mutation analysis

All six patients with EGFR gene mutations obtained clinical benefit from erlotinib while 2 of 10 patients with KRAS gene mutations derived clinical benefit. Please refer to supplemental section (available at Annals of Oncology online) for details.

discussion

The clinical findings of the MERIT study are consistent with those observed in the phase III BR.21 study of erlotinib versus placebo in patients with previously treated advanced NSCLC [1] and confirm the safety and efficacy of erlotinib in this disease.

This study is one of the largest global, multicentre, gene-profiling studies to be conducted in NSCLC to date and shows the feasibility of carrying out prospective tissue-based analyses in this patient population. Nevertheless, the difficulties in obtaining adequate histologic tumour samples in patients with lung cancer highlight the importance of evaluating new techniques for tumour sampling, such as cytologic analysis.

The primary objective of the study was the identification of differentially expressed genes that are predictive for clinical benefit from erlotinib treatment. Clinical benefit was defined as objective tumour response or SD lasting ≥12 weeks, which was considered a relevant efficacy outcome in mainly pretreated patients with advanced NSCLC, given that SD is an important factor contributing to the overall survival benefit produced by erlotinib [1]. The quality of the gene expression profiling data obtained was confirmed by the discrimination of different tumour histologies in an unsupervised clustering analysis. The study was adequately powered to detect genes with a large difference in mean expression levels between patients with and without clinical benefit. The primary analysis did not identify any statistically significant differentially expressed genes, indicating that it is unlikely that there are any single genes in NSCLC tumour cells with a large difference in mean expression levels (at the mRNA level) between patients who derive clinical benefit from erlotinib therapy and those who do not.

An exploratory analysis revealed three genes (EGFR, PSPH and RAPGEF5) that were overexpressed in patients achieving tumour response (PR) with erlotinib therapy versus those with early disease progression or who were not assessable. The EGFR and PSPH genes are located very close to each other on chromosome 7 (positions 7p11.2 and 7p12, respectively). A recent molecular analysis has indicated that the EGFR region on chromosome 7 is frequently amplified in lung adenocarcinoma [19]. Furthermore, in this study, the levels of both EGFR and PSPH mRNA were significantly associated with high EGFR gene copy number (assessed using FISH). Taken together, these data may indicate that EGFR and PSPH could be co-amplified in a single genetic event focused on the 7p11−7p12 region of the chromosome and that this may play a role in determining sensitivity to erlotinib.

RAPGEF5 is also located on chromosome 7 but is more distant from EGFR, being at position 7p15.3. RAPGEF5 encodes a guanine nucleotide exchange factor involved in intracellular signalling [20, 21], which may provide a potential link between its up-regulation and increased sensitivity to erlotinib.

The results of this exploratory analysis were technically confirmed by assessing EGFR, PSPH and RAPGEF5 mRNA expression using an alternative technique (qRT–PCR) in a subset of the same patients. For EGFR, very similar results were obtained irrespective of the technique used to assess mRNA levels. This provides further evidence of a link between EGFR expression level and clinical outcome with erlotinib [22]. Up-regulation of PSPH as assessed by qRT–PCR was also observed in patients who responded to erlotinib compared with those who did not. No strong trend was observed for RAPGEF5 expression, however, using this technique. Disparities between Affymetrix and qRT–PCR results for RAPGEF5 may be due to its relatively low expression and the greater sensitivity of the qRT–PCR technique.

In summary, the results of the MERIT study support the use of erlotinib as an effective and well-tolerated alternative to chemotherapy for patients with relapsed advanced NSCLC. Successful completion of this study provides genome-wide expression data from >100 patients who were treated with erlotinib. The primary analysis identified no single genes whose baseline expression in tumour samples is highly predictive of clinical benefit from erlotinib therapy. However, an exploratory analysis identified three genes (EGFR, PSPH and RAPGEF5) whose expression was significantly associated with tumour response to erlotinib. Independent quantification of the mRNA of these genes validated the association between EGFR and PSPH overexpression and clinical outcome, although the correlation between RAPGEF5 levels and outcome is less clear. Further validation of these findings is required from independent studies.

funding

F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd.

disclosures

The authors BK, CH, LE, PD, MA and PM are the employees of Roche; MA holds stock in Roche and JB is the consultant and on the advisory board for Exelixis, Merck, Roche and Novartis.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Mark Smith of Gardiner-Caldwell Communications for editorial assistance.

References

- 1.Shepherd FA, Rodrigues Pereira J, et al. Erlotinib in previously treated non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:123–132. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa050753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bezjak A, Tu D, Seymour L, et al. Symptom improvement in lung cancer patients treated with erlotinib: quality of life analysis of the National Cancer Institute of Canada Clinical Trials Group Study BR.21. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:3831–3837. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.05.8073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tsao MS, Sakurada A, Cutz JC, et al. Erlotinib in lung cancer—molecular and clinical predictors of outcome. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:133–144. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa050736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cappuzzo F, Hirsch FR, Rossi E, et al. Epidermal growth factor receptor gene and protein and gefitinib sensitivity in non-small-cell lung cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005;97:643–655. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dji112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Eberhard DA, Johnson BE, Amler LC, et al. Mutations in the epidermal growth factor receptor and in KRAS are predictive and prognostic indicators in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer treated with chemotherapy alone and in combination with erlotinib. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:5900–5909. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.02.857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hirsch FR, Varella-Garcia M, Bunn PA, Jr, et al. Molecular predictors of outcome with gefitinib in a phase III placebo-controlled study in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:5034–5042. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.3958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marchetti A, Felicioni L, Buttitta F. Assessing EGFR mutations. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:526–528. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc052564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhu C-Q, da Cunha Santos G, Ding K, et al. Role of KRAS and EGFR as biomarkers of response to erlotinib in National Cancer Institute of Canada Clinical Trials Group Study BR.21. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:4268–4275. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.8924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brugger W, Triller N, Blasinska-Morawiec M, et al. Biomarker analyses from the phase III placebo-controlled SATURN study of maintenance erlotinib following first-line chemotherapy for advanced NSCLC. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27 411s ASCO Annual Meeting Proceedings (Abstr 8020) [Google Scholar]

- 10.Therasse P, Arbuck SG, Eisenhauer EA, et al. New guidelines to evaluate the response to treatment in solid tumors. European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer, National Cancer Institute of the United States, National Cancer Institute of Canada. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92:205–216. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.3.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schneider CP, Heigener D, Schott-von-Römer K, et al. Epidermal growth factor receptor-related tumor markers and clinical outcomes with erlotinib in non-small cell lung cancer: an analysis of patients from German centers in the TRUST study. J Thorac Oncol. 2008;3:1446–1453. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e31818ddcaa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kakiuchi S, Daigo Y, Ishikawa N, et al. Prediction of sensitivity of advanced non-small cell lung cancers to gefitinib (Iressa, ZD1839) Hum Mol Genet. 2004;13:3029–3043. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddh331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang SJ, Chen JJ. Sample size for identifying differentially expressed genes in microarray experiments. J Comput Biol. 2004;11:714–726. doi: 10.1089/cmb.2004.11.714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Irizarry RA, Bolstad BM, Collin F, et al. Summaries of Affymetrix GeneChip probe level data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:e15. doi: 10.1093/nar/gng015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Johnson WE, Li C, Rabinovic A. Adjusting batch effects in microarray expression data using empirical Bayes methods. Biostatistics. 2007;8:118–127. doi: 10.1093/biostatistics/kxj037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Monti S, Tamayo P, Mesirov J, et al. Consensus clustering: a resampling-based method for class discovery and visualization of gene expression microarray data. Mach Learn. 2003;52:91–118. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J R Stat Soc Series B Stat Methodol. 1995;57:289–300. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Weir BA, Woo MS, Getz G, et al. Characterizing the cancer genome in lung adenocarcinoma. Nature. 2007;450:893–898. doi: 10.1038/nature06358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.de Rooij J, Rehmann H, van Triest M, et al. Mechanism of regulation of the Epac family of cAMP-dependent RapGEFs. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:20829–20836. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M001113200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hong J, Doebele RC, Lingen MW, et al. Anthrax edema toxin inhibits endothelial cell chemotaxis via Epac and Rap1. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:19781–19787. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M700128200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dziadziuszko R, Hirsch FR. Advances in genomic and proteomic studies of non-small-cell lung cancer: clinical and translational research perspective. Clin Lung Cancer. 2008;9:78–84. doi: 10.3816/CLC.2008.n.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.