Abstract

Objective

To assess legislation requiring drug companies to report gifts to providers, and to evaluate the information obtained.

Data Sources

Data included legislation in Vermont, Minnesota, Maine, Massachusetts, West Virginia, and the District of Columbia, and company disclosure data from Vermont.

Study Design

We evaluated the strengths and weaknesses of state legislation. We also analyzed 4 years of company disclosures from Vermont, assessing the value and distribution of industry–provider exchanges and identifying emerging trends in companies' practices.

Data Collection Methods

State legislation is publically available. We obtained Vermont's data through requests to the state's Attorney General's office.

Principal Findings

Of the state laws, only Vermont's yielded robust, publically available data. These data show gifting was dominated by a few major corporations, and <2 percent of Vermont's prescribers received 69 percent of gifts and payments. Companies were especially generous to specialists in psychiatry, endocrinology/diabetes/metabolism, internal medicine, and neurology. Companies increasingly used loopholes in the law to avoid public scrutiny.

Conclusions

Disclosure laws are an important first step in bringing greater transparency to physician–industry relationships. But flaws and weaknesses limit the states' ability to render physician–industry exchanges fully transparent. Future efforts should build on these lessons to render physician–industry relationships fully transparent.

Keywords: Drug industry, gifts, conflict of interest, disclosure, health care policy

Persuaded that gifts to physicians from drug companies may have adverse effects on patient care and health care costs, federal and state officials are seeking ways to promote greater transparency in physician–industry interactions. Six states now require drug companies to report gifts and payments to physicians, and many others are considering similar bills (National Conference of State Legislatures 2008). National legislation may also be forthcoming. In September 2007, U.S. Senators Charles Grassley and Herbert Kohl introduced “The Physician Payments Sunshine Act.” The proposed law would require drug and device manufacturers to report their gifts and payments to physicians to a national registry (S. 2029 2007; H.R. 5605 2008;).

The drive for greater transparency is apparent, but almost no research has examined companies' disclosures in the states with gift laws. A search of the literature yielded only one study: an analysis of 2 years of data from Minnesota and Vermont documenting that industry payments to physicians were substantial, often exceeding U.S.$100 (Ross et al. 2007). The impact of the six state initiatives remains largely unknown. What are the strengths and weaknesses of the information obtained by different states? What might the data reveal about physician–industry relationships, and what are the implications for providers, patients, and policy makers? How might these findings inform future legislation?

To answer these questions, we evaluated the pharmaceutical gift disclosure laws in Vermont, Minnesota, Massachusetts, Maine, West Virginia, Massachusetts, and the District of Columbia. We also conducted an in-depth analysis of one initiative, Vermont's, to explore what can be known, and what remains hidden, about drug companies' gifts to physicians. As we shall see, existing disclosure laws are an important first step in bringing greater transparency to physician–industry relationships. But flaws and weaknesses limit the states' ability to render physician–industry exchanges fully transparent. Given their limitations, stronger legislation mandating full disclosure is required.

STATE LEGISLATION

In 1993, Minnesota became the first state to mandate industry disclosure of payments related to medical conferences, honoraria, compensation connected to research, or any payment totaling U.S.$100 or more to physicians (Minnesota Payments Disclosure Law, 151.47(f) 1993). In 2001, Vermont required pharmaceutical companies to report “the value, nature, and purpose” of gifts to health care providers in excess of U.S.$25 (Pharmaceutical Manufacturer Payment Disclosure 2001). Maine and DC enacted legislation in 2003, followed by West Virginia in 2004 (District of Columbia Municipal Regulations 2003; Maine Department of Health and Human Services 2003; West Virginia Pharmacy Council 2004;). The Massachusetts law was enacted in 2008 (Pharmaceutical and Medical Device Manufacturer Conduct 2008).

The six state laws differ in several critical ways (Table 1). These variations affect the quality and transparency of data and, therefore, suggest the broad components of effective legislation. First, they provide varying degrees of public access to the data. In Vermont, companies' disclosures are publicly accessible in an electronic format, and the Vermont Attorney General's office posts annual reports on the aggregate data on its website. The Massachusetts law does not provide for annual reports by the state, but the Massachusetts Department of Public Health intends to post the data on its website. (Companies will begin reporting on July 1, 2010.) Minnesota's disclosures are only available in paper form at the State Board of Pharmacy, and the state provides no annual reports. The laws in DC, Maine, and West Virginia do not establish public access to the data. Companies began disclosing in Maine and DC on July 1, 2007, but no state reports have yet been issued. West Virginia's reporting began on March 1, 2008, and the state's Pharmaceutical Cost Management Council is currently preparing a summary report (Pharmaceutical Cost Management Council 2008).

Table 1.

Characteristics of State Gift Disclosure Laws

| Public Access to Raw Data | Annual Reports | Data Itemized, Includes Recipient Identity | Enforcement Provisions | Compliance | Exemptions | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vermont | Electronic | Yes | Yes | Strong | High | Gifts under U.S.$25, samples, clinical trial payments, education grants, rebates/discounts, “trade secrets” |

| Minnesota | Paper only | No | Yes | Weak | Low | Payments under U.S.$100, samples |

| Massachusetts | Electronic | None yet | Yes | Unclear | Unknown | Gifts under U.S.$50, clinical trial payments |

| DC | No | None yet | Yes | Weak | Unknown | Gifts under U.S.$25, clinical trial payments, education grants |

| Maine | No | None yet | Yes | Weak | Unknown | Gifts under U.S.$25, clinical trial payments, education grants |

| West Virginia | No | None yet | No | None | Unknown | Gifts under U.S.$100, clinical trial payments, education grants |

States also require different degrees of specificity in company disclosures. Minnesota, Massachusetts, and Vermont mandate that companies disclose each individual gift, specifying such details as recipient identity and type and value of payment. In West Virginia, companies are required only to report total expenditures, in dollar ranges, and the number, but not the names, of recipients in each range. Maine and DC require separate reporting of each payment, but, again, the data will not be a matter of public record.

Provisions for enforcement and compliance also vary considerably. In Vermont, companies failing to file disclosures face U.S.$10,000 fines and legal action by the state's Attorney General (Vermont's Office of the Attorney General 2007). Minnesota's law also establishes a U.S.$10,000 penalty per violation, but enforcement has reportedly been weak and compliance uneven; only 25 percent of companies filed disclosures consistently from 2002 to 2004 (Harris 2007; Ross et al. 2007;). Massachusetts' law sets a maximum fine of U.S.$5,000 per “knowing and willful” violation, but the law does not define these terms. Maine's and DC's laws set a maximum penalty of U.S.$1,000 plus attorney's fees for noncompliance. West Virginia's law contains no provisions for enforcement.

The laws also provide a variety of exemptions and exclusions. In all six states, payments under a specified dollar amount need not be reported, but the threshold varies—U.S.$25 in Vermont, DC, and Maine, U.S.$50 in Massachusetts, U.S.$100 in Minnesota and West Virginia. Minnesota does not require companies to report gifts of drug samples. Massachusetts excludes payments for clinical trial work. DC, Maine, and West Virginia exempt educational payments and clinical trial work. Vermont exempts samples, payments for work on clinical trials, grants for medical education, and rebates and discounts on bulk purchasing. Vermont's Access to Public Records Law also has a unique provision that shields industry “trade secrets” from public view. Trade secrets are broadly defined as

… including, but not limited to, any formulae, plan, pattern, process, tool, mechanism, compound, procedure, production data, or compilation of information which is not patented, which is known only to certain individuals within a commercial concern, and which gives its user or owner an opportunity to obtain business advantage over competitors who do not know it or use it.

This language gives companies wide latitude to designate any or all of their gifts to prescribers as “trade secret.” Companies must still report these payments, but the state cannot make them public.

VERMONT AS A WINDOW INTO THE POWER OF DISCLOSURE LEGISLATION

Given the limits of the legislation, what can be learned from companies' disclosures? Because Vermont offers the most robust, publicly available data for an in-depth analysis, with strong provisions for enforcement and compliance, we analyzed 4 years of data from this state. We explored the value and distribution of industry gifts and payments to health care providers. We also sought to identify emerging trends in companies' practices. The Vermont disclosures reveal previously unknown details about industry marketing expenditures, provide valuable insight into the impact of gift reporting laws on company behavior, and suggest principles for more effective future legislation.

Methods

Using Vermont's Access to Public Records Law, we filed requests with the Vermont Attorney General's office for companies' disclosures for July 1, 2002, through June 30, 2006. Within 4 weeks, we received Excel spreadsheets specifying the following variables for each non-trade-secret gift or payment: company name, recipient type (doctor, nurse, pharmacist, etc.), payment nature (cash, food, grant, etc.), payment purpose (speaker fees, detailing, education, etc.), and dollar value. After June 30, 2003, the data also included recipients' names, professional degrees, and other identifying information.

From the Vermont Attorney General's website, we obtained the state's annual reports, which provided the aggregate value of payments for each fiscal year, the number of companies filing disclosures, the names and average expenditures of the five top-spending companies, and the distribution of payments among provider types. The reports also identified the degrees and specialties of the top 100 recipients and the aggregate amounts they received. Summary tables listed all disclosing companies and ranked them in order of expenditures.

Vermont's trade-secret law prevented us from obtaining or analyzing disclosures designated as proprietary. However, the annual reports note the percentage of payments declared proprietary and the number of companies using the trade-secret provision. We were also able to identify which companies categorized some or all of their gifts as trade secret by comparing the list of companies in the annual reports with those that appeared in the non-trade-secret data we received: companies who declared all their gifts proprietary only appeared in the annual reports, whereas those who allowed at least some of their data to remain public also appeared in the data spreadsheets.

FINDINGS

Total Spending Trends

Total industry spending in Vermont increased 8 percent, from U.S.$2,085,929 in fiscal year 2003 (FY 03) to U.S.$2,247,769 in FY 06. However, average spending declined nearly 40 percent, from U.S.$45,850 per company in FY 03 to U.S.$27,750 in FY 06. The rise in total spending was due to growth in the number of companies making (and/or reporting) payments to Vermont's providers: in FY 06, 86 companies filed disclosures, compared with 41 companies in FY 03. Neither the raw data nor the state's annual reports shed light on why more companies filed reports or why average expenditures dropped. What is clear is that 4 years after the law's enactment, companies continued to spend considerable sums marketing to Vermont's providers.

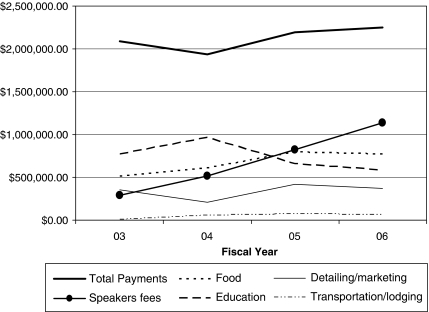

So too, Vermont's law has not reduced practices criticized by prominent medical leaders and organizations (Brennan et al. 2006; Association of American Medical Colleges 2008;). Speakers' fees quadrupled over 4 years, and gifts of food grew 51 percent (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Industry Payments to Vermont Physicians, Fiscal Year 2003–Fiscal Year 2006

Note. Payment types may be overlapping. Additional payment types (e.g., cash/check, donation/grant, consulting) appear in the data. This chart displays the five largest, by dollar value, appearing in all 4 years' reports. Sources: Vermont Attorney General's Office's Annual Reports.

Major Corporations Dominate

Vermont physicians received gifts and payments from a wide range of companies—including many small biotech firms and start-up companies marketing a single product. However, major corporations dominated. The top five spenders in Vermont varied yearly,1 but all ranked among the 50 largest pharmaceutical companies by global health care revenues and R&D expenditures (MedAdNews 2007).

Over a 4-year period, the top five increasingly outspent their peers, even as mean expenditures per company fell: in FY 03, the top five companies spent an average of U.S.$296,202, about 6.5 times the overall, per-company mean of U.S.$45,850. In FY 06, the top five spent, on average, 9.6 times more than the overall, per-company mean (U.S.$265,237 versus U.S.$27,750).

Payments to Top Recipients

Most company largesse went to a small proportion of providers. In FY 06, Vermont had 5,608 licensed professionals authorized to prescribe, dispense, or purchase pharmaceutical products, including physicians, nurses, pharmacists, physician assistants, veterinarians, hospitals, nursing homes, and health benefit plan administrators. Of these, the top 100 recipients (<2 percent) received U.S.$1,549,945.68, or 69 percent of the total. Even more striking is the proportion of gifts received by a small minority of physicians: 77 MDs and DOs (about 1 percent of prescribers, or 4 percent of physicians) received U.S.$1,346,557.60, nearly 60 percent of all reported gifts and payments (Table 2).

Table 2.

Top 100 Recipients by Specialty, FY 06

| No. in Top 100 | Value of Payments | % Overall Total | Average per Recipient | No. in VT | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physicians | 77 | U.S.$1,346,557.60 | 59.90 | U.S.$17,487.76 | 1,730 |

| Psychiatry | 11 | U.S.$502,612.02 | 22.36 | U.S.$45,692.00 | 201 |

| Endocrinology, diabetes, and metabolism | 5 | U.S.$168,648.91 | 7.50 | U.S.$33,729.78 | 12 |

| Internal medicine | 16 | U.S.$150,209.70 | 6.68 | U.S.$9,388.11 | 216 |

| Neurology | 5 | U.S.$115,230.40 | 5.13 | U.S.$23,046.08 | 14 |

| Family practice | 12 | U.S.$71,069.02 | 3.16 | U.S.$5,922.42 | 305 |

| Oncology | 3 | U.S.$59,144.02 | 2.63 | U.S.$19,714.67 | 43 |

| Clinical europhysiology | 1 | U.S.$26,493.45 | 1.18 | U.S.$26,493.45 | 5 |

| Osteopathy | 1 | U.S.$46,642.74 | 2.08 | U.S.$46,642.74 | 43 |

| Pediatrics | 4 | U.S.$42,655.32 | 1.90 | U.S.$10,663.83 | 159 |

| Nephrology | 1 | U.S.$25,294.74 | 1.13 | U.S.$25,294.74 | 10 |

| Dermatology | 2 | U.S.$23,399.00 | 1.04 | U.S.$11,699.50 | 24 |

| Gastroenterology | 1 | U.S.$17,398.98 | 0.77 | U.S.$17,398.98 | 24 |

| Cardiovascular disease | 2 | U.S.$10,974.68 | 0.49 | U.S.$5,487.34 | 48 |

| Hematology | 1 | U.S.$10,121.71 | 0.45 | U.S.$10,121.71 | 16 |

| Allergy and immunology | 1 | U.S.$7,983.40 | 0.36 | U.S.$7,983.40 | 8 |

| Geriatrics | 1 | U.S.$6,481.11 | 0.29 | U.S.$6,481.11 | 26 |

| OB/GYN | 1 | U.S.$6,365.64 | 0.28 | U.S.$6,365.64 | 72 |

| Ionizing radiation privileges | 9 | U.S.$55,832.76 | 2.48 | U.S.$6,203.64 | N/A |

| Other recipients | 23 | U.S.$203,388.26 | 9.05 | U.S.$57,491.31 | N/A |

| RN/APRN | 6 | U.S.$54,620.85 | 2.43 | U.S.$9,103.48 | N/A |

| Hospitals | 4 | U.S.$34,791.02 | 1.55 | U.S.$8,697.76 | N/A |

| Colleges/universities | 2 | U.S.$25,537.57 | 1.14 | U.S.$12,768.79 | N/A |

| PA | 3 | U.S.$12,226.59 | 0.54 | U.S.$4,075.53 | N/A |

| Pharmacist | 1 | U.S.$5,126.60 | 0.23 | U.S.$5,126.60 | N/A |

| Other* | 7 | U.S.$71,085.63 | 3.16 | U.S.$10,155.09 | N/A |

| Total | 100 | U.S.$1,549,945.86 | 68.95 | U.S.$15,032.82 | 5,608 |

Note. “Other” is unspecified in the Vermont Attorney General Report and may include physicians.

Sources: FY 06 Annual Report of the Vermont Attorney General and 2006 Vermont Department of Health Physician Survey Statistical Report.

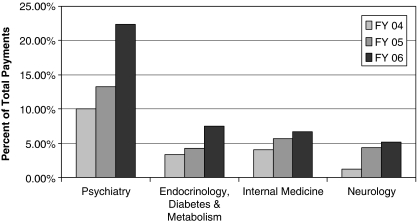

Companies were particularly generous to specialists in psychiatry; endocrinology, diabetes, and metabolism; internal medicine; and neurology (in that order). In FY 06, 11 psychiatrists—0.6 percent of all physicians in Vermont—received U.S.$502,612, more than 22 percent of all gifts. This intensive marketing to psychiatry is consistent with national sales data: in 2006, antipsychotics and antidepressants were two of the top four therapeutic classes, with U.S.$25 billion in sales (IMS Health 2008).

Five specialists in endocrinology, diabetes, and metabolism (about 0.3 percent of Vermont's physicians) received the second largest amount in FY 06—U.S.$168,649 or about 8 percent of the total payments. Sixteen internal medicine physicians (0.9 percent of Vermont's 1,730 MDs and DOs) received U.S.$150,210, approximately 7 percent of gifts. Five neurology (0.3 percent of Vermont's physicians) captured U.S.$115,230, about 5 percent of the total.

These specialties received a greater share of the total with each passing year. From FY 04 to FY 06,2 gifts to top recipients in psychiatry, endocrinology, diabetes and metabolism, and internal medicine approximately doubled. Top recipients in neurology received an almost fivefold increase (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Trends in Industry Payments to Top Specialties, Fiscal Year 2004–Fiscal Year 2006

Sources: Vermont Attorney General's Office's Annual Reports and Non-trade-Secret Data.

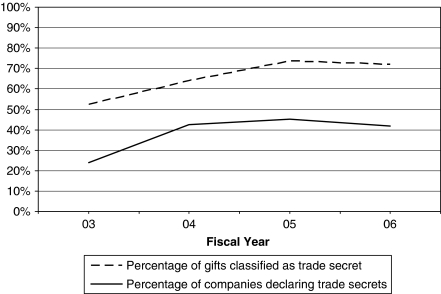

Prevalence of Trade Secrets

From FY 03 to FY 06, companies made increasing use of Vermont's trade-secret provision. The proportion of companies using this provision nearly doubled, from 24 percent in FY 03 to 42 percent in FY 06. So too, the percentage of payments (by dollar value) categorized as trade secret increased by one-third, from 54 percent in FY 03 to 72 percent in FY 06 (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Prevalence of Trade Secrets, Fiscal Year 2003–Fiscal Year 2006

Sources: Vermont Attorney General's Office's Annual Reports and Non-trade-Secret Data.

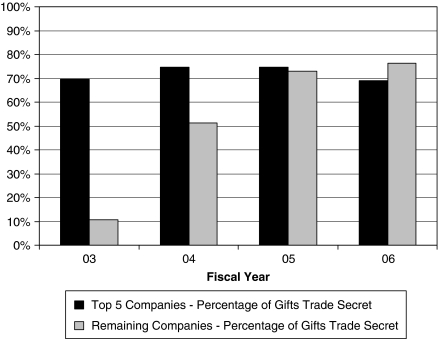

The prevalence of trade secrets varied between the largest spenders and the remaining companies. The top five spenders were consistently secretive: they declared about 70 percent of their payments trade secret each year. Over time, the remaining companies followed their lead, increasing their use of the provision sevenfold, from 11 percent in FY 03 to 76 percent in FY 06 (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Use of Trade Secrets Provision, by Company Rank, Fiscal Year 2003–Fiscal Year 2006

Sources: Vermont Attorney General's Office's Annual Reports and Non-trade-Secret Data.

The proportion of companies declaring 100 percent of their payments as trade secret also grew. This figure nearly doubled, from 17 percent in FY 03 to 32 percent in FY 06. The top 10 spenders led this trend, moving from 20 percent in FY 03 to 70 percent in FY 06.

LEARNING FROM VERMONT: TOWARDS A MODEL LAW

Vermont's law has exposed the dimensions of industry gifting, demonstrating the power of legislation to bring transparency to physician–industry exchanges. We now have an intriguing, if only partial, view of company payments to prescribers. As Vermont is a small, mostly rural state with a relatively small number of prescribers, its data may not be indicative of marketing strategies elsewhere in the United States. So too, our analysis relied on data from FY 03 to FY 06. In light of increased public attention to physician–industry relationships and declining company profits, it is possible that later data would reveal different trends in industry spending.

Our findings underscore the need, first, to create a national gift disclosure law. It would allow policy makers, researchers, journalists, and the public to learn the full extent and cost of company payments to health care providers. It would also reveal geographic and demographic differences. A national law, however, should not preempt state laws. It should set a floor, not a ceiling, for industry disclosure. States may require additional information about company marketing expenditures, and a national law should not interfere with their ability to gather and publicize such information.

Second, disclosure laws must make transparent the value of gifts and the identity of recipients. Only in this way is it possible to hold recipients accountable for their industry ties and to determine whether they should be allowed to serve on committees that oversee institutional purchasing or promulgate treatment guidelines. Full reporting by companies is all the more necessary because physicians' self-disclosure is unreliable (Harris 2008). Because no medical institution requires physicians to substantiate self-reports with tax returns, only strict, comprehensive disclosure laws will make physicians' industry ties transparent and verifiable. By the same token, disclosure laws must include provisions for auditing to ensure the accuracy of company reports.

Third, new initiatives must eliminate disclosure exemptions. Vermont's law allows many common industry payments to remain hidden by exempting samples, educational travel grants, clinical trial work, and, until July 1, 2009, gifts under U.S.$25. Samples constitute about half of the pharmaceutical industry's marketing budget, and so-called nominal gifts are very common. Given the absence of data on these widespread practices, our findings may significantly underestimate the value of industry payments to Vermont providers.

Fourth, a model law would make all commercial health care entities subject to the same disclosure requirements. Vermont's law, for example, does not require disclosures from device companies, biotech firms, and other health care industries that commonly gift prescribers and purchasers. These omissions should be corrected.

Fifth, trade-secret provisions should not be made part of disclosure laws. Companies have become increasingly adept at using this loophole in Vermont to broadly shield their marketing activities from public scrutiny. Recognizing this problem, Vermont legislators recently passed a bill to exempt marketing practices from trade-secret protection. The new restrictions took effect July 1, 2009 (Vermont's Office of the Attorney General 2009).

Sixth, states must have effective provisions that address a company's failure to file complete disclosures. Laws must specify penalties and remedies for deficiencies in reporting.

Finally, disclosure laws must empower those charged with data collection and analysis to refine disclosure requirements as needed. “You learn as you go,” notes Vermont's Former Assistant Attorney General Julie Brill. “After the first year of collecting data, we realized we needed more details about gifts” (personal communication). In Vermont, the Attorney General's office can request additional details about nonexempt gifts by issuing a guidance.3 This crucial flexibility in the law has allowed for development of a more robust dataset. For example, starting in FY 07, Vermont mandated companies to include the name of the product being detailed. This new requirement revealed that 20 drugs (about 7 percent of all products named in companies' disclosures) accounted for 62 percent of total gifts and payments in FY 07 (Sorrell 2008). Vermont's ability to refine its disclosure requirements is yielding an unprecedented level of detail about industry gifting practices.

We are well aware that even full transparency has its limits. Despite the “chilling effect” cited by opponents of disclosure laws (Johnson 2008), transparency alone may not curtail the prevalence or influence of physician–industry exchanges. Indeed, disclosure policies might even appear to condone the practice of gifting. Stricter regulations, including outright bans on gifts and tighter limits on other payments, are required. The industry's recently revised PhRMA Code, which took effect in January, 2009, is a half-step in the right direction: it prohibits gifting of noneducational items and restaurant meals (PhRMA 2008). However, food in physicians' offices and at conferences remains permissible, and the new Code sets no dollar limits on speaking and consulting arrangements, which are critical to companies' efforts to cultivate relationships with “opinion leaders” and other influential decision makers. More noteworthy, Vermont's law was recently amended to eliminate gifts as of July 1, 2009. Still, policy makers should consider that company's marketing budgets are fungible. Efforts to restrict marketing in one area may serve to increase industry activity in others.

Nor is it clear that transparency is immediately useful to consumers. Patients may not seek out their physicians' disclosures or make use of the information. Research has found wide variation in consumers' responses to disclosures in product advertising and in provider report cards. For some consumers, disclosures enhance trust, while others see them as discrediting (Earl and Pride 1984; Marshall et al. 2003;). Nonetheless, at the very least, transparency would empower patients, consumer groups, and other third parties to consider the implications of providers' industry ties.

These limitations not withstanding, many benefits would follow from full transparency. Health care organizations and professional medical associations could verify conflicts of interest so as to better determine membership on purchasing committees, advisory boards, and treatment guidelines committees. Institutional review boards and journal editors would be able to corroborate researchers' conflict of interest statements. Robust disclosure data would identify individuals and institutions with extensive industry ties, perhaps prompting them to reassess their practices and policies. Patients might learn to bring this knowledge into the examining room. So too, full transparency would advance public consideration of the appropriate limits of physician–industry ties.

Whatever the present limits, the movement for transparency is gaining momentum. We recognize that legislators have just begun their efforts to promote transparency. It is not surprising that the initial state laws have weaknesses. Policy makers are in a position to learn from the early efforts and make full disclosure the standard practice.

Acknowledgments

Joint Acknowledgment/Disclosure Statement: This research was made possible by a grant from the state Attorney General Consumer and Prescriber Education Grant Program, which is funded by the multistate settlement of consumer fraud claims regarding the marketing of the prescription drug Neurontin. The authors thank the Attorney General's office of the State of Vermont for providing the data for the study. The authors have no financial, personal, or other conflicts of interest to disclose.

Disclosures: None.

Disclaimers: None.

NOTES

Eli Lilly and Forest appeared in the top five all 4 years. GlaxoSmithKline and Sanofi Aventis were top spenders three times, Merck twice, and Astra Zeneca, Pfizer, Novartis, and Bristol-Myers Squibb once each.

This analysis does not include FY 03 data, as Vermont began requesting recipient identities in FY 04.

Obtaining disclosures on exempt gifts—samples or clinical trial payments, for example—requires legislative action to alter the statute's language on exemptions.

SUPPORTING INFORMATION

Additional supporting information may be found in the online version of this article:

Appendix SA1: Author Matrix.

Please note: Wiley-Blackwell is not responsible for the content or functionality of any supporting materials supplied by the authors. Any queries (other than missing material) should be directed to the corresponding author for the article.

REFERENCES

- Association of American Medical Colleges. “Industry Funding of Medical Education” [accessed on November 21, 2008]. Available at https://services.aamc.org/Publications/showfile.cfm?file=version114.pdf&prd_id=232.

- Brennan TA, Rothman DJ, Blank L, Blumenthal D, Chimonas SC, Cohen JJ, Goldman J, Kassirer JP, Kimball H, Naughton J, Smelser N. Health Industry Practices that Create Conflicts of Interest. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2006;295:429–33. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.4.429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- District of Columbia Municipal Regulations. “Prescription Drug Marketing Costs, Chapter 18, Title 22” [accessed on December 2, 2008]. Available at http://hrla.doh.dc.gov/hrla/lib/hrla/pharmacy_control/chapter.18.accessrx.pdf.

- Earl R, Pride W. Do Disclosure Attempts Influence Claim Believability and Perceived Advertiser Credibility? Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science. 1984;12(1–2):23–37. [Google Scholar]

- Harris G. “Psychiatrists Top List in Drug Maker Gifts.”The New York Times, 27 June.

- Harris G. “Popular Radio Host Has Drug Company Ties.”The New York Times, 22 November.

- H.R. 5605. “Physician Payments Sunshine Act of 2008” [accessed on November 21, 2008]. Available at http://www.govtrack.us/congress/billtext.xpd?bill=h110-5605.

- IMS Health. “2007 Top Therapeutic Classes by U.S. Sales” [accessed on December 2, 2008]. Available at http://www.imshealth.com/deployedfiles/imshealth/Global/Content/Document/Top-Line%20Industry%20Data/2006%20Top%2010%20Therapeutic%20Classes%20by%20US%20Sales.pdf.

- Johnson K. “PhRMA Statement on Massachusetts Legislation” [accessed on November 21, 2008]. Available at http://www.pharmalot.com/wp-content/uploads/2008/08/phrma-mass-statement.doc.

- Maine Department of Health and Human Services. “Reporting and Fee Requirements for Pharmaceutical Manufacturers and Labelers, Section 2: Reporting of Prescription Drug Marketing Costs, 10–144, Chapter 275” [accessed on December 2, 2008]. Available at http://maine.gov/sos/cec/rules/10/144/144c275-section-2.doc. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Marshall MN, Shekelle PG, Davies HTO, Smith PC. Public Reporting on Quality in the United States and the United Kingdom. Health Affairs. 2003;22(3):134–48. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.22.3.134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MedAdNews. Top 50 Pharmaceutical Companies Charts & Lists. MedAdNews, Vol. 13, no. 9.

- Minnesota Payments Disclosure Law, 151.47(f) “Wholesale Drug Distributor Licensing Requirements” [accessed on November 21, 2008]. Available at https://www.revisor.leg.state.mn.us/bin/getpub.php?pubtype=STAT_CHAP_SEC&year=2006§ion=151.47.

- National Conference of State Legislatures. “2008 Prescription Drug State Legislation” [accessed on November 21, 2008]. Available at http://www.ncsl.org/programs/health/drugbill08.htm.

- Pharmaceutical and Medical Device Manufacturer Conduct. “Chapter 111N of Massachusetts General Acts” [accessed on February 11, 2009]. Available at http://www.mass.gov/?pageID=eohhs2terminal&L=5&L0=Home&L1=Government&L2=Laws%2C+Regulations+and+Policies&L3=Department+of+Public+Health+Regulations+%26+Policies&L4=Proposed+Amendments+to+Regulations&sid=Eeohhs2&b=terminalcontent&f=dph_legal_pharmacy_medical_devices&csid=Eeohhs2.

- Pharmaceutical Cost Management Council. “Statement on PCMC's website” [accessed on December 2, 2008]. Available at http://www.pharmacycouncil.wv.gov/rule/Pages/default.aspx.

- Pharmaceutical Manufacturer Payment Disclosure. “33 V.S.A. § 2005(a)(1)” [accessed on December 2, 2008]. Available at http://www.atg.state.vt.us/upload/1226591720_2008_Pharmaceutical_Marketing_Disclosures_Report.pdf.

- PhRMA. “Code on Interactions with Healthcare Professionals” [accessed on December 1, 2008]. Available at http://www.phrma.org/files/PhRMA%20Marketing%20Code%202008.pdf.

- Ross J, Lackner JE, Lurie P, Gross CP, Wolfe S, Krumholz HM. Pharmaceutical Company Payments to Physicians. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2007;297:1216–23. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.11.1216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- S. 2029. “Physician Payments Sunshine Act of 2007” [accessed on May 12, 2009]. Available at http://www.govtrack.us/congress/billtext.xpd?bill=s110-2029.

- Sorrell W. “Pharmaceutical Marketing Disclosures for the Period July 1, 2006 to June 30, 2007” [accessed on December 2, 2008]. Available at http://www.atg.state.vt.us/upload/1226591720_2008_Pharmaceutical_Marketing_Disclosures_Report.pdf.

- Vermont's Office of the Attorney General. “Attorney General Requires Pharmaceutical Manufacturer To Comply With Marketing Disclosure Law” (press release) [accessed on November 21, 2008]. Available at http://www.atg.state.vt.us/display.php?pubsec=4&curdoc=1314.

- Vermont's Office of the Attorney General. “Disclosures of Marketing Expenditures for Prescription Drugs, Biological Products and Medical Devices” (press release) [accessed on June 3, 2009]. Available at http://www.atg.state.vt.us/display.php?smod=177.

- Vermont Statutes Title 1. “Access to Public Records, 1V.S.A. § 317(b)(9)” [accessed on December 2, 2008]. Available at http://www.leg.state.vt.us/statutes/fullsection.cfm?Title=01&Chapter=005&Section=00317.

- West Virginia Pharmacy Council. “Advertising Reporting Rule, CSR 206-1” [accessed on December 2, 2008]. Available at http://www.pharmacycouncil.wv.gov/rule/Documents/206CSR1.pdf.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.