Abstract

This single-subject case study was conducted as a part of a randomized trial investigating the efficacy of mechanical diagnosis and therapy (MDT) and spinal thrust manipulation (STM) in patients who meet a clinical prediction rule (CPR) for spinal manipulation. Following initial examination, a patient who met the CPR was treated initially with STM and then eventually with MDT. The Oswestry Disability Questionnaire (ODI), Fear-Avoidance Beliefs Questionnaire, and the Numerical Pain Rating Scale (NPRS) were administered at the initial examination and at a two-week follow-up. Data were analyzed based on changes in the pain rating scale, ODI, and straight leg raise scores from initial examination to discharge. In accordance with a study protocol in which the patient was part of, this patient was changed from STM to MDT after the second physical therapy visit due to failure of overall improvement. The patient received MDT during the third session and continued with this approach until discharge. This patient responded favorably to MDT presenting with a 20° improvement in SLR on the left and 10° on the right, 6 points lower on the NPRS, and a 4% decrease on the OSW after a total of 6 visits.

KEYWORDS: Clinical Prediction Rule, Low Back Pain, McKenzie, Spinal Manipulation

Low back pain (LBP) is cited as the second most common ailment for which treatment is sought by individuals1. Physical therapy interventions for LBP may include passive and active programs including spinal manipulation2,3 and exercises based on a determined direction of preference. Spinal manipulative therapy may include thrust and non-thrust treatments. Exercise based on direction of preference is a hallmark of the mechanical diagnosis and therapy (MDT) approach and is defined as the movement that decreases, centralizes, or abolishes the patient's symptoms4–10. Both spinal thrust manipulation (STM)2,3 and the MDT approach4–9 have been identified as efficacious treatment methods for patients with low back pain.

Preliminary efficacy exists for both MDT and STM during treatment of LBP1–3,11,12. Further evidence supports the use of classifying patients based on clinical prediction rules (CPRs) through the clustering of signs and symptoms11,12,14,15. Childs et al12 investigated the CPR of Flynn et al11 and found it discriminative in identifying patients with acute low back pain who can benefit from early use of STM. In the validation study of Childs and colleagues12, the comparative group received exercises that differed from the concepts and prescriptive elements germane to the MDT approach. To date, there is no published research that compares the relative effectiveness of STM to MDT in patients who meet Flynn et al's CPR11.

Schenk et al9 has provided the most parallel research on this topic in a study comparing MDT to spinal mobilization in patients classified as having a lumbar posterior disc derangement. MDT was determined to be more beneficial as measured by the Numerical Pain Rating Score (NPRS) and Oswestry Disability Index scores (OSW)9 as compared to a group that received manual physical therapy. This case study describes the intervention on a patient who was a consented subject in a randomized controlled trial comparing MDT vs. SMT in subjects who met four out of five criteria on the CPR for spinal manipulation.

Patient Characteristics

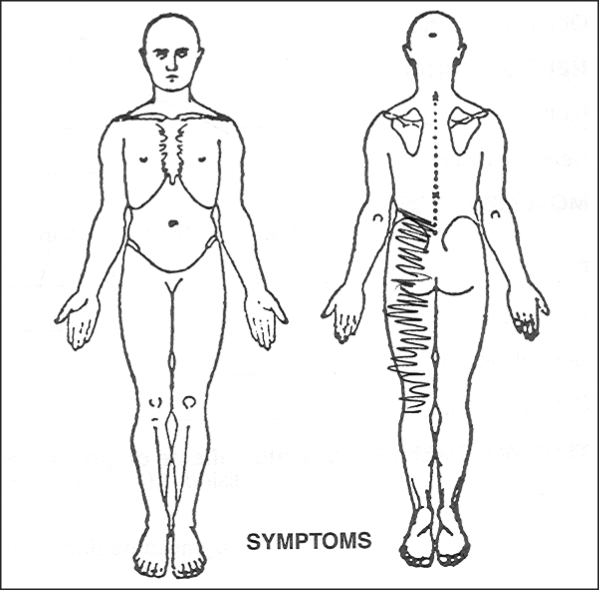

The patient, a 49-year-old female with a chief complaint of asymmetrical left low back and left posterior thigh pain, was recruited from a physical therapy outpatient clinic of the Catholic Health System in western New York State. Informed consent was obtained from her prior to treatment. The location of the patient's symptoms is depicted in the self-administered pain drawing (Figure 1). The mechanism of injury was a fall from a bike, which occurred four days prior to the initial physical therapy examination. The patient's entry criteria at initial examination included the following: 1) no pain below the knee, 2) symptom duration of four days, greater than 35° of hip internal rotation, and lumbar hypomobility as assessed using spinal spring tests. The patient's Fear-Avoidance Beliefs Questionnaire work (FABQw) subscale score was 31, which exceeded the score of 19 identified in the CPR. The randomized trial included patients who met 4 of 5 of the CPR criteria. This patient met 4 out of the 5 criteria (Table 1), which has been found to predict a positive response from STM11; therefore, she was enrolled in a randomized clinical trial sponsored by the authorship team.

FIGURE 1.

Pain drawing at initial examination.

TABLE 1.

Study classification criteria outlined in this study.

| Criterion | Flynn et al's CPR |

|---|---|

| Duration of symptoms | < 16 days |

| Extent of distal symptoms | No symptoms distal to knee |

| Hip IR ROM | ≥ 1 hip w/ > 35° IR |

| PIVM testing | ≥ 1 hypomobile segment in L-spine |

| FABQ work subscale score | < 19 points |

Note: The criteria for thrust manipulation are described above according to Flynn et al's CPR11.

IR = internal rotation, ROM = range of motion, PIVM = passive intervertebral motion, FABQ = fear avoidance belief questionnaire.

Examination

After obtaining informed consent, the patient underwent a physical therapy examination. Functional questionnaires including the OSW, FABQw, and NPRS were administered followed by a subjective interview and an objective physical exam. Jensen et al16 suggested that 10-and 21-point scales provide sufficient levels of discrimination, in general, for chronic pain patients to describe pain intensity. The physical examination process incorporated assessment of posture and structural alignment, spinal active range of motion, myotomal tests, lumbar repeated movements, reflex assessment, straight leg raise measures, palpation, and spring testing.

Upon initial evaluation, the patient's baseline OSW was 30%. Fritz and Irrgang17 found the minimum clinically important difference, defined as the amount of change that best distinguishes between patients who have improved and those remaining stable, was approximately 6 points for the modified OSW. The patient had no significant past medical history. The postural exam revealed a decreased lumbar lordosis. Spinal flexion active range of motion was found to be within normal limits and was measured with a single inclinometer. Rondinelli et al18 found the median range of error was 8.5° using the single inclinometer. Repeated flexion in standing and in supine caused the patient's symptoms to worsen in the left posterior thigh, while repeated lumbar extension in standing for 10 repetitions resulted in movement of the symptoms from the posterior thigh to the left low back indicating a centralization of symptoms.

Repeated extension in lying led to a further centralization of symptoms to the lumbar spine following 20 repetitions. Centralization was defined as the movement of symptoms from a more distal location to a more central location5,6,10. Straight leg raises measured 0°-70° on the left and 0°-80° on the right. Palpation revealed tenderness in the lumbar paravertebrals bilaterally.

Clinical Impression

The patient's physical therapy diagnosis was low back pain with hypomobility, and the MDT classification was posterior asymmetrical derangement based on the symptom location and response to repeated movement testing10. The MDT derangement classifications and more recent derangement terminology are found in Table 2.

TABLE 2.

MDT derangement classifications.

| Derangement | Posterior/Anterior | Deformity | Response to Repeated End-Range Spinal Movement | More Recent Terminology |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Posterior | None | Worse with flexion/better with extension | Central Symmetrical |

| 2 | Posterior | Acute lumbar kyphosis | Worse with flexion/better with prone progression | Central Symmetrical |

| 3 | Posterolateral | None | Worse with flexion/better with extension or extension with hips of set | Unilateral Asymmetrical Symptoms to Knee |

| 4 | Far lateral | Lateral shift | Worse with flexion/better with side-gliding | Unilateral Asymmetrical Symptoms to Knee |

| 5 | Posterolateral | None | Worse with flexion/extension or extension with hips of set | Unilateral Asymmetrical to Below Knee |

| 6 | Far lateral | Lateral shift | Worse with flexion/better with side-gliding | Unilateral Asymmetrical to Below Knee |

| 7 | Anterior | Accentuated lumbar lordosis | Worse with extension/better with flexion | Unilateral Asymmetrical Symptoms to Knee |

Intervention

To simulate the prescription associated with the randomized controlled trial, the patient was assigned to receive spine manipulation first. Treatment sessions 1 and 2 consisted of the lumbopelvic thrust technique11 administered to the left (symptomatic) side. Because no audible or palpable cavitation was heard, the treating physical therapist administered the lumbopelvic STM to the right side in accordance with the original CPR design. In addition to STM, the patient received instruction on the hand-heel rock range of motion exercise for 30 repetitions and 20 repetitions for sessions 1 and 2, respectively, again in accordance with the original CPR design. The hand-heel rock involved movement into flexion and then extension from the quadruped position. These exercises were performed both in the clinic and at home.

After two treatments of STM on the patient's left side, no change in NPRS was found. As dictated in the procedures of the parent RCT, if the patient failed to improve with the randomly assigned treatment, the intervention would be changed to the alternative treatment, which in this case, was MDT. The NPRS was used for deciding to switch this subject into the other treatment group. Clinically, the decision to change groups based on symptom response and location of symptoms was supported by Werneke et al19, who found a pain diagram could be used to categorize symptoms as low back, buttock/thigh, or distal to the knee based on the distal-most extent of symptoms.

The patient began MDT treatment at a rating of 6 out of 10 in the left posterior thigh on the NPRS. A review of the patient's physical therapy documentation showed that the patient had reported that symptoms were less severe but noted “increased stiffness” in the lumbar region after each session with STM.

The patient received MDT during the third session. According to the direction of preference determined at the initial evaluation, the movements that resulted in centralization were repeated in standing and repeated extension in lying (EIL) for 2 sets of 10 repetitions each. Extension in standing led to centralization of symptoms from the left posterior thigh to the left lumbar region while extension in lying centralized symptoms to the lumbar area. On the return to PT for the 4th visit, the patient described symptoms in the left lumbar area, which were rated as a 4/10. MDT was continued in the fourth session and consisted of repeated extension in lying (EIL) for 3 sets of 10 repetitions with belt overpressure. Symptoms were abolished after the performance of repeated movements. Upon return for visits 5 and 6, the patient described central lumbar symptoms rated as a 3/10, and 2/10, respectively. The patient performed repeated extension in standing and repeated extension in lying for 3 sets of 10 repetitions each without overpressure. Repeated extension in standing led to a decrease in central pain and repeated EIL abolished symptoms at each visit. As a home exercise program, the patient performed 10 repetitions of extension in standing or repeated extension in lying motions on an hourly basis from session 3 until discharge.

In addition to physical therapy administered in the clinic, the patient was also asked to complete a daily log of adherence to the home exercises. Intervention included 6 treatments within a 3-week period. According to the study protocol, at the conclusion of the 2nd visit, the patient was reassessed using the NPRS. Following discharge from the study, the patient was re-evaluated using the NPRS and OSW. The patient intervention and symptom response are represented in Table 3.

TABLE 3.

Patient's symptoms/outcomes with thrust manipulation and MDT.

| Visit/Intervention | NPRS/Symptom Location Pre-Treatment | Treatment | NPRS/Symptom Location Post-Treatment | OSW |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1/initial examination/STM | 6/10 lumbar and left posterior thigh | Lumbopelvic thrust Hand-heel rock × 30 | Unchanged | 30% (pre-treatment) |

| 2/STM | 6/10 lumbar and left posterior thigh | Lumbopelvic thrust Hand-heel rock × 20 |

Unchanged | |

| 3/STM | 6/10 left lumbar and left posterior thigh | EIS 10×2 EIL 10×2 |

Centralized to left lumbar Centralized to lumbar |

|

| 4/MDT | 4/10 left lumbar | EIL with belt overpressure 10×3 | Symptoms abolished | |

| 5/MDT | 3/10 central lumbar | EIS 10×6 | Decreased and abolished | |

| 6/MDT | 2/10 central lumbar | EIS 10×6 | Decreased and abolished | |

| Discharge status | 0/10 | 26% |

STM = spinal thrust manipulation, EIL = extension in lying, EIS = extension in standing, MDT = mechanical diagnosis and therapy.

Outcomes

The OSW scores indicated a 4% difference from the 30% baseline level with the score decreasing to 26%. The NPRS decreased from 6 to 0 when comparing pre- to post-test scores. Bilateral straight leg raises improved as the left straight leg raise increased 20° and the right straight leg raise measure increased by 10°.

Discussion

This study analyzed the outcomes of a patient treated initially with STM and later with MDT. The safety and efficacy of both methods of treatment for low back pain have been established1,4–9,13,20. The patient report of increased stiffness combined with no change in the NPRS led the treating physical therapist to switch the patient to the MDT intervention. The patient's baseline NPRS score was above the average of female participants in a study by George et al21, who found that higher NPRS scores were predictive of less positive outcomes in people treated for acute low back pain.

The subject met all five of the CPR criteria, with the exception of the FABQw. Flynn et al11 made two points that supported including this patient in the present investigation. According to Flynn and colleagues11, the presence of four of the five variables in the prediction rule increases the likelihood of success from 45% to 95%. In addition, the authors mentioned that the best univariate predictor of success with manipulation was the duration of the current symptoms; the more acute symptoms, as found in this patient, were more likely to respond favorably to manipulation. This factor made this patient a subject of interest as to whether MDT might be effective in patients who meet the CPR for thrust manipulation.

The FABQw has been found to have good predictive validity in a person's ability to return to work22,23. The patient scored a 31 on the Fear-Avoidance Beliefs Questionnaire work subscale, although she continued working. Fritz and George 23 found that cut-off scores up to 34 on the Fear-Avoidance Beliefs Questionnaire are relatively sensitive and specific for predicting a decrease in disability and a decreased likelihood of prolonged work restrictions when provided with appropriate care. Despite reporting reduced pain after using exercises based on direction of preference, the patient reported a decrease in disability of only 4 points on the ODI. The subject initially received STM and the ODI was not tabulated after this intervention.

This finding is in contrast to other studies that have found a more dramatic change in function following STM11 and/or centralization of symptoms with an MDT approach5,6,8. This finding suggests that pain scores and disability scores may be less related when patients have high initial FABQw findings or that disability is a concept that is less responsive to change. The lack of clinically important change in the ODI and the high initial FABQw in a patient who continued to work are points of interest that require further investigation.

Many patients with acute low back pain in the United States either seek chiropractic treatment24 or are medically managed through analgesics prescribed by their primary care physicians, both of which involve a passive approach to care. Additionally, a recent CPR investigation by Hallegraeff et al25 found no additional benefit of four manipulations over two for those who met two of the five criteria from the Flynn et al11 CPR. The patient in this study presented with a posterior asymmetrical derangement based on responses to repeated movement testing. Her movements allowed the therapist to ascertain a directional preference, which suggests that an active approach would have been beneficial for this individual. Matching exercise along with the direction of preference assists in pain reduction and recovery of function4 and allows for self-management of the patient's condition. Although mixed results exist regarding active management based on disease chronicity, an active self-management has been advocated as a useful approach for low back pain10,26,27.

Conclusions

Understanding the appropriate approach to treatment by classification and sub-grouping of patients according to factors, for example, criteria based on a CPR or a direction of preference based on patient response, may lead to improved efficiency in the treatment of low back pain. MDT may foster a patient's independence and lessen dependence on the physical therapist because the patient may learn exercises, movements, and postures to effectively manage present and future episodes of low back pain15. Future research should focus on aspects concerning the abilities of patients to self-manage low back pain symptoms after intervention with a physical therapist to determine if fostering patient independence through exercise can reduce recidivism. Although a CPR has been established in previous studies to identify patients who would benefit from STM as a treatment for acute low back pain10,13,28, further research is required to determine if classification of patients according to examination and CPR criteria produces favorable outcomes relative to MDT.

REFERENCES

- 1.Miller E, Schenk R, Karnes J, Rousselle J. A comparison of the McKenzie approach to a specific spine stabilization program for chronic low back pain. J Man Manip Ther. 2005;13:103–112. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kohlbeck FJ, Haldeman S, Hurwitz EL, Da-genais S. Supplemental care with medication-assisted manipulation versus spinal manipulation therapy alone for patients with chronic low back pain. J Manipulative Physiology Ther. 2005;28:245–252. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2005.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lisa AJ, Holmes EJ, Ammendolia C. High-velocity low-amplitude spinal manipulation for symptomatic lumbar disc disease: A systematic review of literature. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2005;28:429–442. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2005.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Long A, Donelson R, Fung T. Does it matter which exercise? A randomized control trial of exercise for low back pain. Spine. 2004;29:2593–2602. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000146464.23007.2a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Werneke M, Hart DL. Centralization: Association between repeated end-range pain response and behavioral signs in patients with acute non-specific low back pain. J Rehabil Med. 2005;37:286–290. doi: 10.1080/16501970510032901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Werneke M, Hart DL. Centralization phenomenon as a prognostic factor for chronic low back pain and disability. Spine. 2001;26:758–765. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200104010-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Werneke M, Hart DL. Discriminant validity and relative precision for classifying patients with nonspecific neck and back pain by anatomic pain patterns. Spine. 2003;28:161–166. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200301150-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Donelson R, Aprill C, Medcalf R, Grant W. A prospective study of centralization of lumbar and referred pain: A predictor of symptomatic discs and annular competence. Spine. 1997;22:1115–1122. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199705150-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schenk RJ, Jozefczyk C, Kopf A. A randomized controlled trial comparing interventions in patients with lumbar posterior derangement. J Man Manip Ther. 2003;11:95–102. [Google Scholar]

- 10.McKenzie RA. The Lumbar Spine: Mechanical Diagnosis and Therapy. New Zealand: Spinal Publications: Waikanae; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Flynn T, Fritz J, Whitman J, et al. A clinical prediction rule for classifying patients with low back pain who demonstrate short-term improvement with spinal manipulation. Spine. 2002;27:2835–2843. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200212150-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Childs J, Fritz J, Flynn T, et al. A clinical prediction rule to identify patients with low back pain most likely to benefit from spinal manipulation: A validation study. Ann Internal Med. 2004;141:920–928. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-141-12-200412210-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Delitto A, Erhard RE, Bowling RW. A treatment-based classification approach to low back syndrome: Identifying and staging patients for conservative treatment. Phys Ther. 1995;75:470–485. doi: 10.1093/ptj/75.6.470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wilson L, Hall H, McIntosh G, Melles T. Intertester reliability of a low back pain classification system. Spine. 1999;24:248–254. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199902010-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Harris GR, Susman JL. Managing musculoskeletal complaints with rehabilitation therapy: Summary of the Philadelphia panel evidence-based clinical practice guidelines on musculoskeletal rehabilitation interventions. J Fam Pract. 2002;51:1042–1046. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jensen MP, Turner JA, Romano JM. What is the maximum number of levels needed in pain intensity measurement? Pain. 1994;58:387–392. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(94)90133-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fritz JM, Irrgang JJ. A comparison of a modified Oswestry Disability Questionnaire and the Quebec Back Pain Disability Scale. Phys Ther. 2001;81:776–778. doi: 10.1093/ptj/81.2.776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rondinelli R, Murphy J, Esler A, Marciano T, Cholmakjian C. Estimation of normal lumbar flexion with surface inclinometry: A comparison of three methods. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 1992;71:219–224. doi: 10.1097/00002060-199208000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Werneke M, Hart DL, Cook D. A descriptive study of the centralization phenomenon: A prospective analysis. Spine. 1999;24:676–683. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199904010-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Avery S, O'Driscoll ML. Randomized controlled trials on the efficacy of spinal manipulation therapy in the treatment of low back pain. Phys Ther Rev. 2004;9:146–152. [Google Scholar]

- 21.George SZ, Fritz JM, Childs JD, Brennan GP. Sex differences in predictors of outcome in selected physical therapy interventions for acute low back pain. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2006;36:354–336. doi: 10.2519/jospt.2006.2270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fritz JM, George SZ, Delitto A. The role of fear-avoidance beliefs in acute low back pain: Relationships with current and future disability and work status. Pain. 2001;94:7–15. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(01)00333-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fritz JM, George SZ. Identifying psychosocial variables in patients with acute work-related low back pain: The importance of fear-avoidance beliefs. Phys Ther. 2002;82:973–983. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shekelle PG, Adams AH, Chassin MR, Hurwitz EL, Brook RH. Spinal manipulation for low back pain. Ann Intern Med. 1992;117:590–598. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-117-7-590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hallegraeff H, de Greef M, Winters J, Lucas C. Manipulative therapy and clinical prediction criteria in treatment of acute nonspecific low back pain. Percep Motor Skills. 2009;108:196–208. doi: 10.2466/PMS.108.1.196-208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hough E, Stephenson R, Swift L. A comparison of manual therapy and active rehabilitation in the treatment of non specific low back pain with particular reference to a patient's Linton and Hallden psychological screening score: A pilot study. BMC Musculoskeletal Disord. 2007;8:106. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-8-106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Karjalainen K, Malmivaara A, Mutanen P, Roine R, Hurri H, Pohjolainen T. Mini-intervention for subacute low back pain: Two-year follow-up and modifiers of effectiveness. Spine. 2004;29:1069–1076. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200405150-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cleland JA, Fritz JM, Whitman JM, Childs JD, Palmer JA. The use of a lumbar spine manipulation technique by physical therapists in patients who satisfy a clinical prediction rule: A case series. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2006;36:209–214. doi: 10.2519/jospt.2006.36.4.209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]