Abstract

Introduction

Urocortin 1 (Ucn 1) is an endogenous peptide related to the corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF). Ucn 1 is mainly expressed in the perioculomotor area (pIII), and its involvement in alcohol self-administration is well confirmed in mice. In other species, the relationship between the perioculomotor Ucn 1-containing population of neurons (pIIIu) and alcohol consumption needs further investigation. The pIII also has a significant subpopulation of dopaminergic neurons. Because of dopamine’s (DA) role in addiction, it is important to evaluate whether this subpopulation of neurons contributes to addiction-related phenotypes. Furthermore, the effects of gender on the relationship between Ucn 1 and tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) in pIII and alcohol preference in rats have not been previously assessed.

Methods

To address these issues, we compared 2 Sardinian alcohol-preferring sublines of rats, a population maintained at the Scripps Research Institute (Scr:sP) and a population maintained at University of Camerino—Marchigian Sardinian preferring rats (msP), to corresponding non-selectively bred Wistar rats of both sexes. Ucn 1- and TH-positive cells were detected on coronal midbrain sections from 6- to 8-week-old alcohol-naïve animals using brightfield and fluorescent immunohistochemistry. Ucn 1- and TH-positive cells in pIII were counted in the perioculomotor area, averaged across 2 to 3 sets, and binned into 3 bregma levels.

Results

Results demonstrated increased average counts of Ucn 1-positive cells in the middle bregma level in preferring male rats compared to Wistar controls and no difference in TH-positive cell counts in pIII. In addition, fluorescent double labeling revealed no colocalization of Ucn 1-positive and TH-positive neurons. Ucn 1 but not TH distribution was influenced by gender with female animals expressing more Ucn 1-positive cells than male animals in the peak bregma level.

Conclusions

These findings extend previous reports of increased Ucn 1-positive cell distribution in preferring lines of animals. They indicate that Ucn1 contributes to increased alcohol consumption across different species and that this contribution could be gender specific. The results also suggest that Ucn1 regulates positive reinforcing rather than aversive properties of alcohol and that these effects could be mediated by CRF2 receptors, independent of direct actions of DA.

Keywords: Urocortin 1, Tyrosine Hydroxylase, Alcohol Preference, Corticotropin-Releasing Factor, Edinger-Westphal, Alcoholism, Sardinian Preferring Rats

THE CORTICOTROPIN-RELEASING FACTOR (CRF) peptide system has been long proposed to be involved in drug addiction and alcoholism (Dave and Eskay, 1986; Hawley et al., 1994; Inder et al., 1995; Koob, 1999; Rivier et al., 1984; Wand and Dobs, 1991; Wilkins and Gorelick, 1986). In mammals this system is composed of 4 endogenous ligands, namely, CRF, Urocortin (Ucn)1, Ucn 2, and Ucn 3 (Bale and Vale, 2004). These 4 ligands act on CRF1 receptors, CRF2 receptors, and/or the CRF-binding protein with different affinities (Bale and Vale, 2004). Discovered first of the 4 ligands, CRF has attracted the most attention in the addiction field. However, evidence is accumulating that Ucn 1 also may be important for addiction-related behaviors, specifically, for alcohol self-administration (Ryabinin and Weitemier, 2006).

In the brain, Ucn 1 is primarily synthesized in the pericolumotor Ucn-containing population of neurons (pIIIu) and, to a lesser extent, in the lateral superior olive (May et al., 2008; Vaughan et al., 1995). The pIIIu was originally thought to be the Edinger-Westphal nucleus, a brain region primarily involved in ocular functions (Bittencourt et al., 1999; Kozicz et al., 1998; Vaughan et al., 1995). Later, it was realized that this brain region has been misidentified in rodents and humans, and it was subsequently renamed: at first, as the non-preganglionic Edinger-Westphal nucleus (Ryabinin et al., 2005; Weitemier and Ryabinin, 2005), and subsequently, as the pIIIu (May et al., 2008). The pIIIu exerts its actions via projections to the lateral septum, dorsal raphe, spinal cord, and other brain regions (Bachtell et al., 2003; Bittencourt et al., 1999; Weitemier et al., 2005).

Substantial evidence implicating Ucn 1 in alcohol self-administration has been obtained in mouse experimental models. First, various alcohol drinking paradigms in mice have demonstrated preferential induction of Fos immunoreactivity in pIIIu (Bachtell et al., 1999; Ryabinin et al., 2001, 2003; Sharpe et al., 2005). Second, higher levels of Ucn 1 immunoreactivity in pIIIu have been found in ethanol-naïve, C57BL/6J mice, an inbred strain with spontaneously high alcohol preference, than in alcohol-avoiding DBA/2J mice, which show low ethanol preference (Bachtell et al., 2002b; Weitemier et al., 2005). In addition, differences in Ucn1 immunoreactivity were observed between several mouse lines selectively-bred for differences in alcohol intake, ethanol-induced place preference, ethanol-induced hypothermia, ethanol-induced loss of righting reflex or ethanol withdrawal-induced convulsions (Bachtell et al., 2002b, 2003; Kiianmaa et al., 2003; Ryabinin and Tsivkovskaia, 2004; Turek et al., 2008). Third, electrolytic lesions of pIII blocked alcohol preference in C57BL/6J mice (Bachtell et al., 2004). Fourth, injections of picomolar doses of Ucn 1, but not CRF, into the mouse lateral septum selectively attenuated alcohol self-administration (Ryabinin et al., 2008).

Evidence implicating Ucn 1 in alcohol self-administration in other species also exists, but is less substantial and some-what conflicting. Operant alcohol self-administration in alcohol-preferring AA rats (Weitemier et al., 2001) and beer drinking in Sprague–Dawley rats (Topple et al., 1998) each selectively induced c-Fos immunoreactivity in pIIIu. Additionally, higher levels of Ucn 1 immunoreactivity in pIIIu have been observed in the HAD1 and HARF alcohol-preferring rats (each selectively bred for high alcohol intake), compared to their respective alcohol-avoiding LAD1 and LARF lines (selectively bred for low alcohol intake) (Turek et al., 2005). In contrast, high alcohol-preferring inbred P rats have shown lower Ucn 1 immunoreactivity in pIIIu than low alcohol-preferring inbred NP rats, and high alcohol preferring HAD2 and AA lines have not shown significant differences in Ucn 1 immunoreactivity from low alcohol-preferring LAD2 and ANA lines (Turek et al., 2005). Still, further meta-analysis has indicated that the number of Ucn 1-immunoreactive fibers in the lateral septum, a target of pIIIu neurons (Bittencourt et al., 1999; Weitemier et al., 2005), is significantly higher in the 5 lines of alcohol-preferring rats relative to their corresponding alcohol-avoiding lines (Turek et al., 2005). Thus, while overall the majority of the data in rats support previous data in mice, the relationship between Ucn 1 expression and alcohol preference in genetically-selected rats would benefit from further investigation.

Some of the inconsistencies in the reported results might stem from limitations in the design of previous studies. Of importance, previous studies on Ucn 1 expression were only done bi-directionally, comparing alcohol-preferring versus avoiding rodent lines, which could complicate interpretation of the resulting data. Comparison of alcohol-preferring rats versus outbred rats unselected for alcohol preference could be more informative for confirming involvement of Ucn 1 in alcohol “preference.” Additionally, previous studies in selectively bred rats did not analyze females. It was shown previously that Ucn 1 gene expression can be regulated by estrogen (Derks et al., 2007; Haeger et al., 2006), and therefore Ucn 1’s contribution to alcohol intake might be affected by sex. Previous work showed that the pIII area also has a significant subpopulation of dopaminergic neurons (Bachtell et al., 2002a; Gaszner and Kozicz, 2003). Midbrain dopamine (DA) systems are known to contribute to mechanisms of addiction (Kiianmaa et al., 2003; Nestler et al., 1993; Wise, 1998), and previous research suggested differential dopaminergic innervation in structures related to reward behaviors in rats selectively bred for alcohol preference (Casu et al., 2002a). Thus, this study tested the hypothesis that selective breeding for alcohol preference also affected this subpopulation of dopaminergic neurons in pIII. Tyrosine hydroxylase (TH), the rate-limiting enzyme in the biosynthesis of monoamines, is a precursor of both noradrenaline and dopamine, and was used as a marker of noradrenergic and dopaminergic activity (Casu et al., 2002a).

To address the above issues, we used 2 sublines derived from the Sardinian preferring (sP) rats, with their respective nonselectively-bred Wistar pairs in our analyses. The sP rat lines represent unique animal models for human alcohol consumption. The breeding program of sP rats started in 1981 at the University of Cagliari, Italy, with a heterogeneous population of outbred Wistar rats. After 40 generations of mating the sP rats displayed average daily alcohol consumption ranging 6 to 7 g/kg and met the majority of several fundamental requirements for a successful animal model of alcoholism (Colombo et al., 2006).

Starting from the 13th generation of sP rats, a subset of these animals were used for separate selective breeding for alcohol preference at the University of Camerino, Italy. After 20 further generations of selective breeding, this subline was re-named the Marchigian Sardinian preferring rats (msP). Similar to sP rats, msP rats display innate preference for alcohol characterized by: binge-like drinking behavior, consumption of pharmacologically significant daily doses of 7 to 8 g/kg of EtOH (Ciccocioppo et al., 2006), low aversion to alcohol (Ciccocioppo et al., 1999; Polidori et al., 1998), and spontaneous drinking of large amounts of alcohol from the very first homecage presentation (Ciccocioppo et al., 2006).

At the 32nd generation of breeding of sP rats, a subset of sP rats were provided by Dr. G.L. Gessa to The Scripps Research Institute and maintained there without further selective breeding. These rats have been designated as Scr:sP. The Scr:sP rats continue to show alcohol preference (consuming voluntarily about 5 to 6 g/kg of EtOH daily) and display high levels of anxiety-like behavior (Sabino et al., 2006, 2007).

A genetic divergence has emerged between the msP and Scr:sP substrains including specific single nucleotide polymorphisms in the CRF1 gene present in msP but not Scr:sP or corresponding Wistar control lines (Hansson et al., 2006). Therefore, while behavioral profiles of both msP and Scr:sP rats are similar in mimicking several aspects of the human alcoholic population, the underlying genes involved in regulation of alcohol intake partly differ between the 2 sublines, resulting in 2 rat models of alcoholism complementary to each other.

Using these 2 selectively bred preferring rat lines (Scr:sP and msP) versus nonselectively bred Wistar rats, we tested the hypothesis that pIII is involved in the predisposition to high alcohol consumption in rats. To test this hypothesis, we analyzed Ucn 1 and TH immunoreactivity in pIII of male and female alcohol-preferring animals (Scr:sP and msP rats) compared to control Wistar rats.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

The National Institute of Health Guidelines for the Care and Use of Animals were followed throughout all animal procedures. Ethanol-naïve Scr:sP rats (22 to 24 generations of intra-line breeding at the Committee on the Neurobiology of Addictive Disorders of The Scripps Research Institute after 32nd generation of sP selection, n = 11 to 12 per sex) and corresponding control Wistar rats (designated here as Wistar [scr], n = 10 to 12 per sex) were bred at the Scripps Research Institute (La Jolla, CA). Ethanol-naïve msP rats (58 generations of selection, n = 8 per sex) and corresponding control Wistar rats [designated here as Wistar [m], n = 8 per sex] were bred at the University of Camerino (Camerino, Italy). Rats were group-housed and kept on an alcohol-free ad-lib diet until 6 to 8 weeks of age at which point they were anesthetized and perfused with saline followed by 2% paraformaldehyde in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.4). The brains were isolated and postfixed in 2% paraformaldehyde/PBS overnight. After, the brains were transferred to 20% sucrose in PBS and shipped to the Oregon Health & Science University. Upon arrival, brains were transferred to 30% sucrose/PBS containing 0.1% sodium azide and stored at 4 °C.

Brightfield Immunohistochemistry

Forty-micron thick sections were collected on a CM1850 cryostat (Leica Microsystems, Inc., Deerfield, IL). Every 4th section was processed for standard diaminobenzidine (DAB)-based brightfield immunohistochemistry in 3 (for Ucn 1) or 2 (for TH) sets. To avoid effects of variability of DAB staining intensity, each set contained equal number of sections from all animals used in the study. Immunohistochemical analysis for Ucn 1 and TH was performed on sections from approximate bregma levels of −4.61 to −7.00 mm (pIIIu) according to the atlas of Paxinos and Watson (1998).

Ucn 1 immunohistochemistry was performed according to previous protocols (Bachtell et al., 2002b). Endogenous peroxidase activity was quenched by 0.3% peroxide in PBS. Blocking was performed with 2% bovine serum albumin (BSA) + 7.5% 10,000 U/ml heparin in PBS and 0.3% Triton-X 100 (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO). The polyclonal rabbit anti-Ucn 1 antibody (Sigma-Aldrich) was used at a 1:5,000 dilution in 0.1% BSA, 0.3% Triton-X 100 in PBS. Omission of primary antibody and incubation with excess of Ucn 1 peptide (but not Ucn 2, Ucn 3 or CRF peptide) for control purposes resulted in lack of positive staining. Additionally, Ucn 1 staining under similar conditions was lacking in Ucn 1 knockout mice but not their wild type littermates (Ryabinin, unpublished results). A biotinylated anti-rabbit secondary antibody (diluted 1:200 in PBS/Triton) was used to amplify the primary antibody (Vector, Burlingame, CA). Detection of the immunological reaction was made using a Vectastain ABC kit (Vector) and enzymatic development with the Metal Enhanced DAB kit (Thermo Scientific, Pierce, Rockford, IL).

Tyrosine hydroxylase immunohistochemistry was performed by first quenching endogenous peroxidase activity by 0.3% peroxide in PBS. Blocking was accomplished with 4.5% goat serum (Vector) in PBS and 0.3% Triton-X 100 (Sigma-Aldrich). Slices were subsequently incubated overnight in a 1:10,000 dilution of a polyclonal rabbit anti-TH antibody (Chemicon Inc., Millipore, Temecula, CA). Omission of primary antibody for control purposes resulted in lack of positive staining. Biotinylated anti-rabbit (raised in goat) secondary antibody (Vector) (diluted 1:200 in PBS/Triton) was used to detect the TH antibody signal. The immunoreaction was revealed using the Vectastain ABC kit (Vector), and the immunostaining reaction was developed using the metal-enhanced DAB kit (Thermo Scientific).

After each immunohistochemistry protocol, the slices were mounted on gelatinized slides, dehydrated, and coverslipped with Cytoseal 60 mounting medium (Richard-Allan Scientific, Kalamazoo, MI).

Fluorescent Immunohistochemistry

The simultaneous presence of both Ucn 1 and TH was revealed through the following procedure. Slices were blocked with 2% BSA, 7.5% 10,000 U/ml heparin, and 0.3% Triton-X 100 in PBS for 30 minutes. The Ucn 1 antibody was incubated overnight at a 1:5,000 dilution in 0.1% BSA and 0.3% Triton-X 100 in PBS. This was followed by a 2-hour incubation with 0.5% AlexaFluor 488 anti-rabbit (raised in chicken) (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), 0.1% BSA, 0.3% Triton-X 100 in PBS. After thorough washes with PBS, slices were blocked a second time in 4.5% goat serum, 0.1% BSA, and 0.3% Triton-X 100 in PBS for 2 hours. Slices were then incubated with the TH antibody at a 1:10,000 dilution overnight. The TH antibody was visualized with a 2-hour incubation with 0.5% AlexaFluor 555 anti-rabbit (raised in goat) (Invitrogen) in PBS with 0.1% BSA and 0.3% Triton-X 100. Slices were washed with PBS, mounted on gelatinized slides, coverslipped with VectaShield mounting medium for fluorescence with DAPI (Vector), and sealed with clear nail polish.

Quantitative Analysis

Ucn 1-positive and TH-positive cells were counted manually using a Leica DM4000 microscope (Bartels & Stout Inc., Bellevue, WA) at 40× objective magnification by an individual blinded to the identity of the animals. The number of Ucn 1- and TH-positive cells was assessed in 3 (anterior, middle, and posterior) sections of pIII (approximate bregma positions: −4.61 to −5.40 mm, −5.41 to −6.20 mm, −6.21 to −7.00 mm), according to the rat brain atlas (Paxinos and Watson, 1998). Counts obtained with 2 to 3 sections in each bregma position were averaged to produce a single data point per animal for use in statistical analyses. Images were acquired with a Q-Imaging MicroPublisher 3.3 RTV (Surrey, BC, Canada) and processed using Q-Capture and ImageJ Software. Only the number of positive cell bodies, but not the number of Ucn 1-positive fibers, was evaluated in this study because pilot experiments indicated low levels of signal in Ucn 1-positive fibers that would be too difficult to differentiate from background. Variable intensity of Ucn1-positive fiber staining in the lateral septum between rat lines from different laboratories has been observed previously (Turek et al., 2005). It is not clear whether this technical difficulty reflects differences in perfusion and storage of the brains between laboratories or differences in presence of the peptide in these fibers in rats from different animal colonies.

Statistical Analyses

StatView software (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) was used for all statistical analyses. The average number of immunoreactive cells in a given bregma level (anterior, middle, posterior) was used as a single data point in a mixed-design repeated measures ANOVA with alcohol preference (preferring vs. Wistar), subline (scr vs. m), and sex (male vs. female) as between-subjects factors. Bregma level (anterior, middle, posterior) was entered as a within-subject factor. The ANOVA was followed by post-hoc analysis using Fischer PLSD when appropriate. The significance level was maintained at p < 0.05. Data are presented in figures as means and standard errors of the mean (SEM).

RESULTS

Distribution of Ucn 1-Positive Cells in pIIIu Area

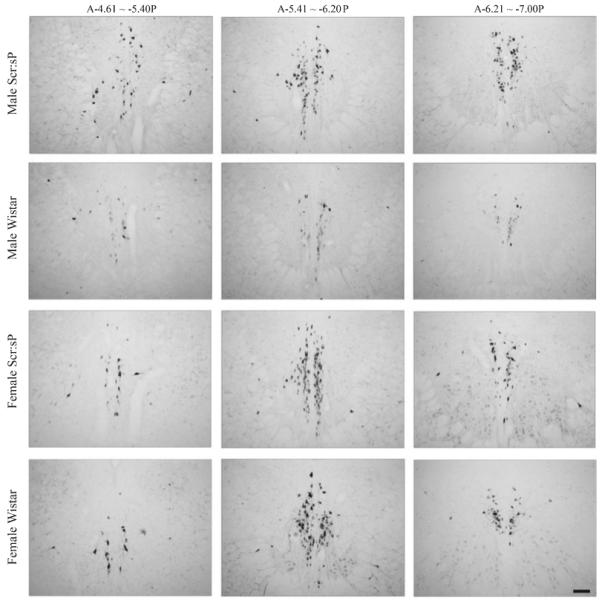

Overall mixed design ANOVA performed on counts of Ucn 1-positive cells results revealed significant main effects of alcohol preference (F1,68 = 9.64, p < 0.003) and bregma level (F2,136 = 391.79, p < 0.0001), as well as significant bregma level by sex (F2,136 = 6.02, p = 0.003), and bregma level by preference (F2,136 = 7.22, p = 0.001) interactions. No significant main effects of subline (i.e., Scripps vs. Marchigian) and no significant interaction of preference by subline were found. Therefore, the data from animals from different sublines were combined for further analyses evaluating effects of sex and preference at each bregma level on the distribution of Ucn 1-positive cells. Representative images for animals of both sexes and preferences at each bregma level are shown in Fig. 1. As evidenced from the images, the patterns of distribution of Ucn 1-positive cells across bregma levels between different groups of animals were similar. Further analyses identified a significant effect of preference (F1,72 = 16.39, p = 0.0001) and a significant preference by sex interaction (F1,72 = 4.50, p = 0.037) only in the middle bregma level (A-5.41 to −6.20P). No significant main effects or interactions were found in the more anterior A-4.61 to −5.40P bregma level. In the more posterior A-6.21 to −7.00P bregma level no significant interactions were detected, and the main effect of preference failed to reach conventional significance level (F1,72 = 3.80, p = 0.056). Please refer to Table 1 for average cell counts for each sex, preference, and subline presented by bregma level.

Fig. 1.

Example of differences in Ucn 1 immunoreactivity in coronal sections of 3 bregma levels of pIII between animals of different lines and gender. Note increased Ucn 1-positive cell counts in the middle bregma level and significant differences in Ucn 1 immunoreactivity between alcohol preferring and Wistar male rats. Scale bar = 100 μm.

Table 1.

Mean (±SEM) Ucn 1-Positive Cell Counts in pIIIu Area for Animals of Different Sexes, Preferences, and Lines

| Average cell counts |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bregma level |

|||||

| Sex | Strain | n | A-4.61 to −5.40P | A-5.41 to −6.20P | A-6.21 to −7.00P |

| Male | Scr::sP | 11 | 26.96 (5.21) | 82.24 (3.94)* | 23.26 (2.80) |

| Male | Wistar (Scr) | 12 | 24.98 (4.55) | 64.60 (4.34) | 17.84 (2.71) |

| Male | msP | 8 | 23.91 (4.98) | 79.18 (5.87)* | 30.51 (5.70) |

| Male | Wistar (m) | 8 | 28.40 (9.75) | 54.49 (2.96) | 18.77 (3.60) |

| Female | Scr:sP | 10 | 23.99 (3.50) | 82.94 (3.54) | 21.38 (2.77) |

| Female | Wistar (Scr) | 11 | 26.68 (4.30) | 84.81 (4.74)** | 18.51 (2.54) |

| Female | msP | 8 | 18.91 (4.29) | 83.87 (4.25) | 16.69 (2.80) |

| Female | Wistar (m) | 8 | 20.53 (2.29) | 66.02 (6.02) | 18.30 (3.82) |

Cells were counted at 40× magnification by a single researcher blinded to the groups of animals. Significantly greater cell counts were observed in the male preferring msP & sP:scr rats compared to male Wistars across middle bregma levels in post-hoc analyses (F1,35 = 21.079, p < 0.0001). There was a significant overall effect of gender in cell counts for the middle bregma, p = 0.0006. Post-hoc analysis:

significantly different from corresponding male Wistars (p < 0.01)

significantly different from male Wistar (Scr) (p < 0.001).

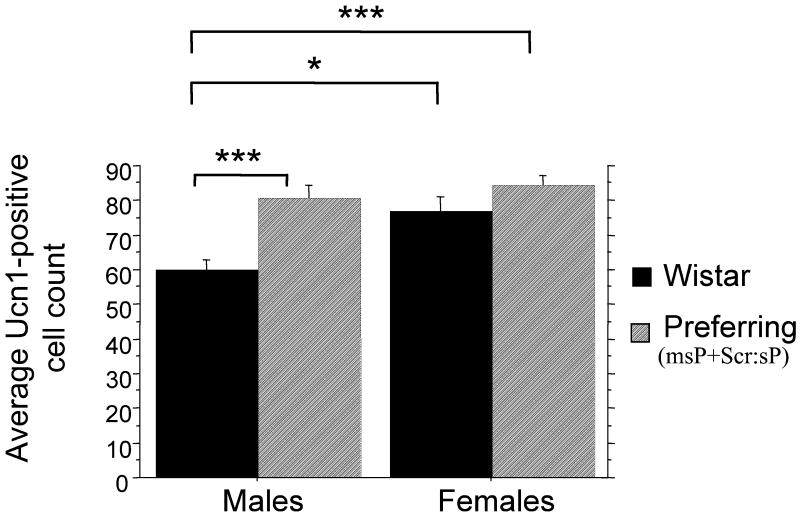

The post-hoc analyses were conducted for the middle bregma level revealing significant difference in Ucn 1-positive cell counts between preferring rats (both Scr:sP and msP sublines combined) and Wistar rats, p < 0.0001. As evidenced from Fig. 2, alcohol-preferring males had significantly higher average counts of Ucn 1-positive cells in the middle bregma level compared to Wistar animals. Further post-hoc analysis revealed significant differences between msP and corresponding Wistar (m) controls (p < 0.01) and Scr:sP versus corresponding Wistar (Scr) controls (p < 0.01) at this bregma level. Similar to male animals, alcohol-preferring females had greater number of Ucn 1-positive cells in the middle bregma level than Wistar females on average; however, the difference in females was not statistically significant, p = 0.177. Interestingly, in the middle (peak) bregma level, female animals on average had significantly higher Ucn 1-positive cell counts than their male peers, p = 0.0006, with the most prominent differences occurring between Wistar females and Wistar males. However, further post-hoc analyses revealed this gender difference was only significant in Wistar (Scr) rats (p < 0.0001) and not in Wistar (m) rats.

Fig. 2.

Average number of Ucn 1-positive cells in the middle bregma level (A-5.41 to −6.20P) of pIII for alcohol preferring (Scr:sP and msP combined) and Wistar rats of both genders. *p < 0.001, ***p < 0.0001.

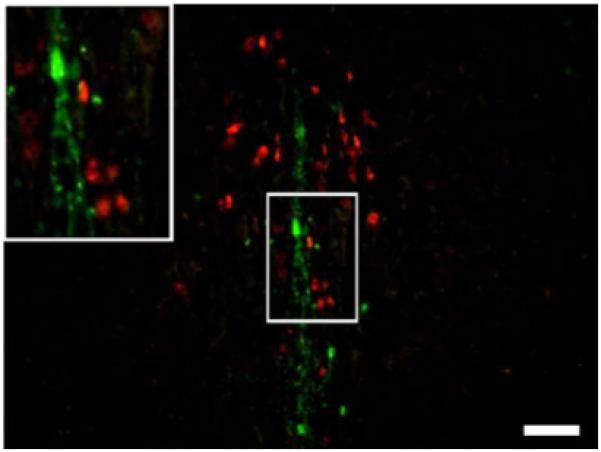

No Colocalization of Ucn 1 and TH Immunoreactivities in pIIIu Area

To investigate whether TH-positive neurons in pIII constitute a subpopulation of Ucn 1-positive neurons or form an independent group of neurons, we performed a double-labeled immunofluorescence immunohistochemical analysis. This analysis did not show any coexistence of Ucn 1 and TH immunoreactivities. Selected examples from Wistar animals are presented in Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

Example of fluorescent immunohistochemistry for Ucn 1 (red) and tyrosine hydroxylase (green) in pIII using coronal slices from a Wistar rat. Note complete lack of Ucn 1 and TH colocalization. Scale bar = 100 μm.

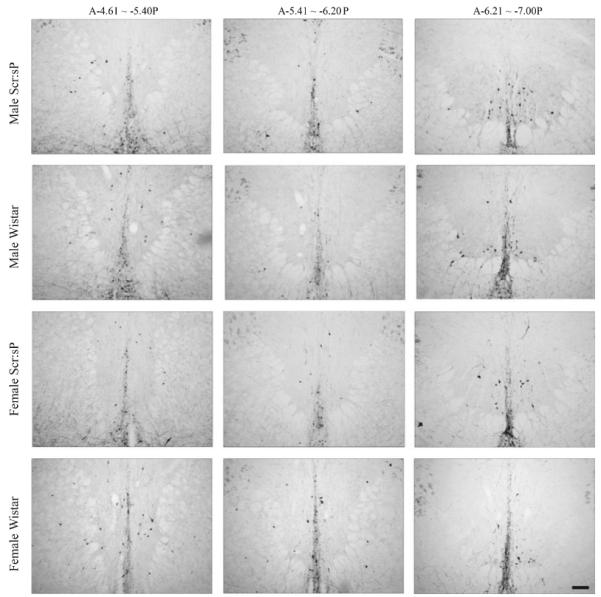

Distribution of TH-Positive Cells in pIIIu Area

The mixed design ANOVA described for Ucn 1 analysis was repeated for TH immunohistochemistry, and the overall ANOVA revealed a significant alcohol preference by subline interaction (F1,66 = 4.35, p = 0.041). However, post-hoc analyses between preferring and control animals [Scr:sP vs. Wistar (s) and msP vs. Wistar (m)] showed no significant pairwise differences in average counts of TH-positive cells.

Further, there was a significant interaction of bregma levels with preference and sex (F2,132 = 6.20, p = 0.003). However, after performing post-hoc analysis of sex by preference effects at each bregma levels, no pairwise differences remained significant. Please refer to Table 2 for the information about the means and SEMs for cell counts for animals of different sex and preference within each bregma level. In conclusion, distribution of TH-positive cells in pIII appeared to be less affected by selection for alcohol preference than the distribution of Ucn 1-positive cells. Representative images from slices with TH staining are displayed in Fig. 4.

Table 2.

Mean (±SEM) TH-Positive Cell Counts in pIIIu Area for Animals of Different Sexes, Preferences, and Lines

| Average cell counts |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bregma level |

|||||

| Sex | Strain | n | A-4.61 to −5.40P | A-5.41 to −6.20P | A-6.21 to −7.00P |

| Male | Scr:sP | 11 | 7.05 (0.84) | 9.47 (0.91) | 11.80 (0.94) |

| Male | Wistar (Scr) | 12 | 6.83 (0.50) | 11.27 (0.70) | 11.51 (2.78) |

| Male | msP | 8 | 6.12 (0.72) | 9.10 (0.71) | 17.41 (2.73) |

| Male | Wistar (m) | 8 | 5.44 (1.49) | 8.73 (1.16) | 9.09 (1.49) |

| Female | Scr:sP | 10 | 7.32 (0.95) | 8.95 (0.48) | 9.95 (0.99) |

| Female | Wistar (Scr) | 11 | 7.91 (0.67) | 9.18 (1.03) | 12.92 (1.59) |

| Female | msP | 8 | 6.26 (0.44) | 8.48 (1.18) | 11.12 (1.52) |

| Female | Wistar (m) | 8 | 5.56 (0.85) | 7.21 (1.17) | 13.35 (1.00) |

Cells were counted at 40× magnification by a single researcher blinded to the groups of animals. No significant differences were found in post-hoc analyses.

Fig. 4.

Example of tyrosine hydroxylase immunoreactivity in coronal sections of 3 bregma levels of pIII between animals of different sublines and gender. Scale bar = 100 μm. No pairwise differences between rat sublines and genders were observed.

DISCUSSION

In the current series of experiments, we evaluated Ucn 1 and TH distributions in pIII of ethanol-naïve Scr:sP and msP alcohol-preferring rats compared to those of Wistar rats of both genders. The most notable finding was that alcohol-preferring male rats of both sublines showed greater average counts of Ucn 1-positive cells than their Wistar counterparts in pIII at the peak (middle) bregma level, where Ucn 1 expression is greatest. Thus, our results showed that rats from Scr:sP and msP preferring lines contained significantly greater levels of Ucn 1-positive cells than nonselectively bred Wistar rats, adding to the evidence from mouse studies that level of Ucn 1 immunoreactivity positively associates with alcohol preference (Bachtell et al., 2002b, 2003; Ryabinin et al., 2002). In rats, the study by Turek and colleagues (2005) evaluating 5 pairs of lines selectively bred for differences in alcohol preference found significantly greater Ucn 1 immunoreactivity in the pIIIu area of preferring lines of HARF/LARF, and HAD2/LAD2 rats while observing no significant differences in HAD1/LAD1 and AA/ANA lines and finding an opposite relationship between alcohol preference and Ucn 1 levels in iP/iNP lines. Our findings of increased Ucn 1 immunoreactivity in Scr:sP and msP preferring lines compared to Wistar controls further supports the hypothesis that Ucn 1 regulates alcohol-related behaviors.

The average counts of Ucn 1-positive cells in alcohol-preferring animals obtained by our study were comparable to those reported previously by Turek and colleagues (2005) for HAD1 and HAD2 preferring lines while differing from counts in AA, iP, and HARF lines. As previously noted by Turek and colleagues (2005), differences in breeding, selection processes, and housing conditions result in animals from different preferring lines displaying unique genotypes and behavioral profiles. Considering these factors, evidence for increased Ucn 1 expression in additional alcohol-preferring lines, as shown here, leaves fewer doubts about the role of Ucn 1 in alcohol-related behaviors in rats. However, it is important to remember that comparative studies of genetic differences rely solely on correlational approaches. Previous studies on genetic differences in the Ucn 1 system in mice were substantiated by functional studies using lesion approaches. Confirming the genetic studies, lesions of the pIIIu area blocked alcohol preference and substantially and selectively reduced alcohol intake in mice (Bachtell et al., 2004; Weitemier and Ryabinin, 2005). Future studies in rats would benefit from approaches that test causal relationships between Ucn 1-positive neurons and alcohol intake.

In contrast to an earlier study comparing selectively bred alcohol-preferring rats to their respective alcohol-avoiding pairs (Turek et al., 2005), this study used nonselectively bred Wistar rats as control groups for both alcohol-preferring strains. The Wistar rats provided a more conservative comparison group for the 2 alcohol-preferring lines allowing conclusions to be drawn about the relationship between Ucn 1 levels and alcohol preference. Thus, finding increased Ucn 1-positive cells in preferring rats suggests that this phenotype is associated with selective breeding for increased alcohol preference and consumption, and not with selective breeding for alcohol aversion. Based on this finding, we speculate that Ucn1 may be involved in regulating positive reinforcing effects of alcohol.

Ucn1 is different from other peptides of the CRF system in that it binds with high affinity to both CRF1 and CRF2 receptors—in contrast with CRF, which primarily binds CRF1 receptors, and Ucn2 and Ucn 3, which primarily bind CRF2 receptors (Bale and Vale, 2004). Interestingly, a genetic variation in the promoter of Crhr1 gene (encoding the CRF1 receptor) has been described in msP rats (Hansson et al., 2006). Specifically, direct sequencing identified 2 single nucleotide polymorphisms in the Crhr1that segregate between msP and Wistar lines (positions −1836 and −2096 vs. first start codon), The 2 polymorphic markers are in allelic identity: G-G is the wild type allele, identical to the published Rattus Norvegicus reference sequence (Ensemble database no. ENSRNOG00000004900). All 20 Wistars sequenced were homozygous for this allele. A-A is a previously unrecognized variant allele encountered only in msP rats. Consistent with a functional significance of this allele, in situ hybridization and receptor biding assays identified higher levels of expression of CRF1 receptor in multiple brain regions of alcohol-naïve msP. CRF1 receptor antagonists potently reduced alcohol drinking and stress-induced reinstatement of ethanol self-administration (Hansson et al., 2006). In contrast, each of 20 Scr:sP rats sequenced for the Crhr1 polymorphism exhibited a wild-type allele, which may correspond to the inability of CRF1 antagonist treatment to reduce their basal drinking levels (Sabino et al., 2006). Because only msP, but not Scr:sP, rats exhibit this functional polymorphism in the Crhr1 gene, and because the Ucn1 peptide is present at higher levels in both msP and Scr:sP versus Wistar rats, it seems likely that Ucn1 contributes to regulation of alcohol drinking via CRF2 and not via CRF1 receptors. Consistent with this hypothesis, several targets of pIIIu area neurons, including the lateral septum and dorsal raphe are enriched by CRF2 receptors. Therefore, the CRF2 receptor should be further explored as a potential target to regulate alcohol drinking.

Furthermore, while significant gender differences in alcohol consumption were described in human alcoholism (Becker and Grilo, 2006; Furtado et al., 2006; Mann et al., 2005; Walitzer and Dearing, 2006; Walter et al., 2005; Wiren et al., 2006; Zywiak et al., 2006), here we for the first time examined alcohol-related gender differences in the Ucn 1 system in rats. Previous studies in mice have not detected any effects of sex on Ucn 1 immunoreactivity in pIIIu area (Bachtell et al., 2003). However, studies by Haeger and colleagues (2006) suggested that activation of the α- and β-estrogen receptors might differentially affect Ucn 1 expression. In agreement with this possibility, Derks and colleagues (2007) found a high density of ER-β-immunopositive neurons in pIII. Additionally, levels of Ucn 1 immunoreactivity in pIII change across pregnancy in rats (Fatima et al., 2007). Such findings are in agreement with the postulation that Ucn 1 levels could be modulated by sex hormones. While previous studies have not reported significant differences in Ucn 1 levels between male and female animals this might be due to lack of systematic analysis across different phases of estrous cycle (Derks et al., 2007), which can obscure differences between male and female animals. The significant gender differences of Ucn 1 expression in pIIIu at peak bregma levels raise the hypothesis that differential Ucn 1 expression may contribute to an influence of gender on alcohol-related behaviors in rats. Future studies on animals of both genders are warranted.

Another goal for this study was to further investigate potential differences in the DA neurons in pIII between alcohol preferring and Wistar rats. There is substantial evidence for the involvement of midbrain-originating DA pathways in mediating drug-seeking behaviors (Kiianmaa et al., 2003; Koob and Le Moal, 2008). Earlier studies conducted in our lab indicated existence of TH-positive cells within the mouse pIII and possible regulation of c-Fos response in pIII by DA (Bachtell et al., 2002a). These TH-positive cells appeared to be an extension of the rostral linear nucleus, a subregion of the highly dopaminergic ventral tegmental area. A study by Gaszner and Kozicz (2003) confirmed that these TH neurons in pIII are dopaminergic. Here, we show that the TH-positive neurons of pIII constitute a subpopulation of cells that do not colocalize with Ucn 1 neurons of pIII. This finding agrees with a recent study showing that only Ucn1-positive, but not TH-positive neurons, show a c-Fos response to ethanol (Spangler et al., 2009). As c-Fos is a marker for postsynaptic activation, it seemed likely that these dopaminergic neurons could modulate the activity of pIIIu. Therefore, this study for the first time examined whether selective breeding in alcohol preference resulted in a change of not only Ucn1 containing, but also dopaminergic cells of pIII. We observed no significant pairwise differences in the number of TH-positive cells in pIII between derivative alcohol-preferring lines and their corresponding Wistar controls. These findings suggest that differences in alcohol drinking between alcohol-preferring rat lines are more associated with differences in Ucn1 neurons, than with differences in dopaminergic cells of pIII. However, the results of our study need to be taken with consideration that the lack of differences in immunohistochemical signals for enzymes involved in neurotransmitter synthesis does not mean that neurons containing these neurotransmitters are not involved in relevant behaviors. For example, Casu and colleagues (2002a,b) found a selective reduction in the TH-positive fiber density in prefrontal cortex and shell of nucleus accumbens of preferring sP animals compared to nonpreferring sNP animals. Therefore, we cannot exclude that TH-positive neurons of pIII may be involved in modulating alcohol preference. Interestingly, tracing studies indicate that the shell of nucleus accumbens in rats is heavily innervated by the TH neurons of the rostral linear nucleus, including neurons in the vicinity of pIII (Del-Fava et al., 2007; Hasue and Shammah-Lagnado, 2002). Additionally, selective 6-hydroxy-DA lesions of these DA neurons in the rostral linear nucleus and periaqueductal gray abolished the development of conditioned place preference to heroin (Flores et al., 2006). More research is needed to understand the contribution of specific subpopulations of pIII neurons to alcoholism-related phenotypes and drug addiction.

In conclusion, this study provided further support for the role of Ucn 1 in the predisposition to high alcohol consumption by showing increased average counts of Ucn 1-immunopositive cells in pIIIu area in alcohol preferring rat lines in comparison with nonselectively bred Wistar controls. Our results suggest that Ucn 1 may contribute to positive reinforcing effects of alcohol, perhaps via CRF2 receptors. We also demonstrated higher levels of in Ucn 1 immunoreactivity in female versus male rats. Our findings indicate a need for further investigations evaluating the Ucn 1 system and its contribution to the regulation of alcohol intake in both male and female animals.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Dawn Cote, BS, and Simranjit Kaur, PhD, for valuable technical assistance. This research was supported by NIAAA 013738 and 016647 grants awarded to AR, NIAAAA P60 AA006420 component awarded to EZ, and 5 T32 DA007262-17 NIDA training grant awarded to IF.

REFERENCES

- Bachtell RK, Tsivkovskaia NO, Ryabinin AE. Alcohol-induced c-Fos expression in the Edinger-Westphal nucleus: pharmacological and signal transduction mechanisms. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2002a;302:516–524. doi: 10.1124/jpet.102.036046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bachtell RK, Tsivkovskaia NO, Ryabinin AE. Strain differences in urocortin expression in the Edinger-Westphal nucleus and its relation to alcohol-induced hypothermia. Neuroscience. 2002b;113:421–434. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(02)00174-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bachtell RK, Wang YM, Freeman P, Risinger FO, Ryabinin AE. Alcohol drinking produces brain region-selective changes in expression of inducible transcription factors. Brain Res. 1999;847:157–165. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(99)02019-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bachtell RK, Weitemier AZ, Galvan-Rosas A, Tsivkovskaia NO, Risinger FO, Phillips TJ, Grahame NJ, Ryabinin AE. The Edinger-Westphal-lateral septum urocortin pathway and its relationship to alcohol consumption. J Neurosci. 2003;23:2477–2487. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-06-02477.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bachtell RK, Weitemier AZ, Ryabinin AE. Lesions of the Edinger-Westphal nucleus in C57BL/6J mice disrupt ethanol-induced hypothermia and ethanol consumption. Eur J Neurosci. 2004;20:1613–1623. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2004.03594.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bale TL, Vale WW. CRF and CRF receptors: role in stress responsivity and other behaviors. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2004;44:525–557. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.44.101802.121410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker DF, Grilo CM. Prediction of drug and alcohol abuse in hospitalized adolescents: comparisons by gender and substance type. Behav Res Ther. 2006;44:1431–1440. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2005.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bittencourt JC, Vaughan J, Arias C, Rissman RA, Vale WW, Sawchenko PE. Urocortin expression in rat brain: evidence against a pervasive relationship of urocortin-containing projections with targets bearing type 2 CRF receptors. J Comp Neurol. 1999;415:285–312. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casu MA, Colombo G, Gessa GL, Pani L. Reduced TH-immunoreactive fibers in the limbic system of Sardinian alcohol-preferring rats. Brain Res. 2002a;924:242–251. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(01)03296-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casu MA, Dinucci D, Colombo G, Gessa GL, Pani L. Reduced DAT- and DBH-immunostaining in the limbic system of Sardinian alcohol-preferring rats. Brain Res. 2002b;948:192–202. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(02)03220-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciccocioppo R, Angeletti S, Chhada M, Perfumi M, Froldi R, Massi M. Conditioned taste aversion induced by ethanol in alcohol-preferring rats: influence of the method of ethanol administration. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1999;64:563–566. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(99)00104-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciccocioppo R, Economidou D, Cippitelli A, Cucculelli M, Ubaldi M, Soverchia L, Lourdusamy A, Massi M. Genetically selected Marchigian Sardinian alcohol-preferring (msP) rats: an animal model to study the neurobiology of alcoholism. Addict Biol. 2006;11:339–355. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-1600.2006.00032.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colombo G, Lobina C, Carai MA, Gessa GL. Phenotypic characterization of genetically selected Sardinian alcohol-preferring (sP) and -non-preferring (sNP) rats. Addict Biol. 2006;11:324–338. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-1600.2006.00031.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dave JR, Eskay RL. Demonstration of corticotropin-releasing factor binding sites on human and rat erythrocyte membranes and their modulation by chronic ethanol treatment in rats. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1986;136:137–144. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(86)90887-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Del-Fava F, Hasue RH, Ferreira JG, Shammah-Lagnado SJ. Efferent connections of the rostral linear nucleus of the ventral tegmental area in the rat. Neuroscience. 2007;145:1059–1076. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.12.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derks NM, Roubos EW, Kozicz T. Presence of estrogen receptor beta in urocortin 1-neurons in the mouse non-preganglionic Edinger-Westphal nucleus. Gen Comp Endocrinol. 2007;153:228–234. doi: 10.1016/j.ygcen.2007.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fatima A, Haroon MF, Wolf G, Engelmann M, Spina MG. Reduced urocortin 1 immunoreactivity in the non-preganglionic Edinger-Westphal nucleus during late pregnancy in rats. Regul Pept. 2007;143:34–38. doi: 10.1016/j.regpep.2007.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flores JA, Galan-Rodriguez B, Ramiro-Fuentes S, Fernandez-Espejo E. Role for dopamine neurons of the rostral linear nucleus and periaqueductal gray in the rewarding and sensitizing properties of heroin. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2006;31:1475–1488. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furtado EF, Laucht M, Schmidt MH. Gender-related pathways for behavior problems in the offspring of alcoholic fathers. Braz J Med Biol Res. 2006;39:659–669. doi: 10.1590/s0100-879x2006000500013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaszner B, Kozicz T. Interaction between catecholaminergic terminals and urocortinergic neurons in the Edinger-Westphal nucleus in the rat. Brain Res. 2003;989:117–121. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(03)03367-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haeger P, Andres ME, Forray MI, Daza C, Araneda S, Gysling K. Estrogen receptors alpha and beta differentially regulate the transcriptional activity of the Urocortin gene. J Neurosci. 2006;26:4908–4916. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0476-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansson AC, Cippitelli A, Sommer WH, Fedeli A, Bjork K, Soverchia L, Terasmaa A, Massi M, Heilig M, Ciccocioppo R. Variation at the rat Crhr1 locus and sensitivity to relapse into alcohol seeking induced by environmental stress. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:15236–15241. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0604419103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasue RH, Shammah-Lagnado SJ. Origin of the dopaminergic innervation of the central extended amygdala and accumbens shell: a combined retrograde tracing and immunohistochemical study in the rat. J Comp Neurol. 2002;454:15–33. doi: 10.1002/cne.10420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawley RJ, Nemeroff CB, Bissette G, Guidotti A, Rawlings R, Linnoila M. Neurochemical correlates of sympathetic activation during severe alcohol withdrawal. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1994;18:1312–1316. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1994.tb01429.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inder WJ, Joyce PR, Ellis MJ, Evans MJ, Livesey JH, Donald RA. The effects of alcoholism on the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis: interaction with endogenous opioid peptides. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 1995;43:283–290. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.1995.tb02033.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiianmaa K, Hyytia P, Samson HH, Engel JA, Svensson L, Soderpalm B, Larsson A, Colombo G, Vacca G, Finn DA, Bachtell RK, Ryabinin AE. New neuronal networks involved in ethanol reinforcement. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2003;27:209–219. doi: 10.1097/01.ALC.0000051020.55829.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koob GF. Stress, corticotropin-releasing factor, and drug addiction. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1999;897:27–45. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1999.tb07876.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koob GF, Le Moal M. Review. Neurobiological mechanisms for opponent motivational processes in addiction. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2008;363:3113–3123. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2008.0094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozicz T, Yanaihara H, Arimura A. Distribution of urocortin-like immunoreactivity in the central nervous system of the rat. J Comp Neurol. 1998;391:1–10. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9861(19980202)391:1<1::aid-cne1>3.0.co;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mann K, Ackermann K, Croissant B, Mundle G, Nakovics H, Diehl A. Neuroimaging of gender differences in alcohol dependence: are women more vulnerable? Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2005;29:896–901. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000164376.69978.6b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- May PJ, Reiner AJ, Ryabinin AE. Comparison of the distributions of urocortin-containing and cholinergic neurons in the perioculomotor midbrain of the cat and macaque. J Comp Neurol. 2008;507:1300–1316. doi: 10.1002/cne.21514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nestler EJ, Hope BT, Widnell KL. Drug addiction: a model for the molecular basis of neural plasticity. Neuron. 1993;11:995–1006. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(93)90213-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paxinos G, Watson C. The Rat Brain in Stereotaxic Coordinates. Academic Press; New York: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Polidori C, Recchi S, Venturi F, Ciccocioppo R, Massi M. Application of taste reactivity to study the mechanism of alcohol intake inhibition by the tachykinin aminosenktide. Peptides. 1998;19:1557–1564. doi: 10.1016/s0196-9781(98)00112-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivier C, Bruhn T, Vale W. Effect of ethanol on the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis in the rat: role of corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF) J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1984;229:127–131. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryabinin AE, Bachtell RK, Freeman P, Risinger FO. ITF expression in mouse brain during acquisition of alcohol self-administration. Brain Res. 2001;890:192–195. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(00)03251-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryabinin AE, Bachtell RK, Heinrichs SC, Lee S, Rivier C, Olive MF, Mehmert KK, Camarini R, Kim JA, Koenig HN, Nannini MA, Hodge CW, Roberts AJ, Koob GF. The corticotropin-releasing factor/urocortin system and alcohol. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2002;26:714–722. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryabinin AE, Galvan-Rosas A, Bachtell RK, Risinger FO. High alcohol/sucrose consumption during dark circadian phase in C57BL/6J mice: involvement of hippocampus, lateral septum and urocortin-positive cells of the Edinger-Westphal nucleus. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2003;165:296–305. doi: 10.1007/s00213-002-1284-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryabinin AE, Tsivkovskaia NO. Expression of neuropeptide urocortin I in alcohol withdrawal seizure-prone and withdrawal seizure-resistant mice. Suppl Abstr Annu RSA Meet, Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2004;28:492. [Google Scholar]

- Ryabinin AE, Tsivkovskaia NO, Ryabinin SA. Urocortin 1-containing neurons in the human Edinger-Westphal nucleus. Neuroscience. 2005;134:1317–1323. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.05.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryabinin AE, Weitemier AZ. The urocortin 1 neurocircuit: ethanol-sensitivity and potential involvement in alcohol consumption. Brain Res Rev. 2006;52:368–380. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2006.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryabinin AE, Yoneyama N, Tanchuck MA, Mark GP, Finn DA. Urocortin 1 microinjection into the mouse lateral septum regulates the acquisition and expression of alcohol consumption. Neuroscience. 2008;151:780–790. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2007.11.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabino V, Cottone P, Koob GF, Steardo L, Lee MJ, Rice KC, Zorrilla EP. Dissociation between opioid and CRF1 antagonist sensitive drinking in Sardinian alcohol-preferring rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2006;189:175–186. doi: 10.1007/s00213-006-0546-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabino V, Cottone P, Steardo L, Schmidhammer H, Zorrilla EP. 14-Methoxymetopon, a highly potent mu opioid agonist, biphasically affects ethanol intake in Sardinian alcohol-preferring rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2007;192:537–546. doi: 10.1007/s00213-007-0746-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharpe AL, Tsivkovskaia NO, Ryabinin AE. Ataxia and c-Fos expression in mice drinking ethanol in a limited access session. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2005;29:1419–1426. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000174746.64499.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spangler E, Cote DM, Anacker AM, Mark GP, Ryabinin AE. Differential sensitivity of the perioculomotor urocortin-containing neurons to ethanol, psychostimulants and stress in mice and rats. Neuroscience. 2009;160:115–125. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2009.02.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Topple AN, Hunt GE, Mcgregor IS. Possible neural substrates of beer-craving in rats. Neurosci Lett. 1998;252:99–102. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(98)00574-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turek VF, Bennett B, Ryabinin AE. Differences in the urocortin 1 system between long-sleep and short-sleep mice. Genes Brain Behav. 2008;7:113–119. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-183X.2007.00336.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turek VF, Tsivkovskaia NO, Hyytia P, Harding S, Le AD, Ryabinin AE. Urocortin 1 expression in five pairs of rat lines selectively bred for differences in alcohol drinking. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2005;181:511–517. doi: 10.1007/s00213-005-0011-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaughan J, Donaldson C, Bittencourt J, Perrin MH, Lewis K, Sutton S, Chan R, Turnbull AV, Lovejoy D, Rivier C, Et AL. Urocortin, a mammalian neuropeptide related to fish urotensin I and to corticotropin-releasing factor. Nature. 1995;378:287–292. doi: 10.1038/378287a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walitzer KS, Dearing RL. Gender differences in alcohol and substance use relapse. Clin Psychol Rev. 2006;26:128–148. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2005.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walter H, Dvorak A, Gutierrez K, Zitterl W, Lesch OM. Gender differences: does alcohol affect females more than males? Neuropsychopharmacol Hung. 2005;7:78–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wand GS, Dobs AS. Alterations in the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis in actively drinking alcoholics. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1991;72:1290–1295. doi: 10.1210/jcem-72-6-1290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weitemier AZ, Ryabinin AE. Brain region-specific regulation of urocortin 1 innervation and corticotropin-releasing factor receptor type 2 binding by ethanol exposure. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2005;29:1610–1620. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000179363.44542.05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weitemier AZ, Tsivkovskaia NO, Ryabinin AE. Urocortin 1 distribution in mouse brain is strain-dependent. Neuroscience. 2005;132:729–740. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2004.12.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weitemier AZ, Woerner A, Backstrom P, Hyytia P, Ryabinin AE. Expression of c-Fos in Alko alcohol rats responding for ethanol in an operant paradigm. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2001;25:704–710. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkins JN, Gorelick DA. Clinical neuroendocrinology and neuropharmacology of alcohol withdrawal. Recent Dev Alcohol. 1986;4:241–263. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4899-1695-2_11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiren KM, Hashimoto JG, Alele PE, Devaud LL, Price KL, Middaugh LD, Grant KA, Finn DA. Impact of sex: determination of alcohol neuroadaptation and reinforcement. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2006;30:233–242. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2006.00032.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wise RA. Drug-activation of brain reward pathways. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1998;51:13–22. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(98)00063-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zywiak WH, Stout RL, Trefry WB, Glasser I, Connors GJ, Maisto SA, Westerberg VS. Alcohol relapse repetition, gender, and predictive validity. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2006;30:349–353. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2006.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]