Abstract

Background:

A phase-III trial showed the non-inferiority of oral capecitabine plus oxaliplatin (XELOX) vs 5-fluorouracil/leucovorin plus oxaliplatin (FOLFOX-6) in terms of efficacy in first-line treatment of metastatic colorectal cancer. A secondary objective was to compare the quality of life (QoL) and health-care satisfaction of patients.

Methods:

Patients were randomised to receive XELOX (n=156) or FOLFOX-6 (n=150) for 6 months. Quality of life and satisfaction were assessed by the Quality of Life Questionnaire-C30 (QLQ-C30) and Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy Chemotherapy Convenience and Satisfaction Questionnaire (FACIT-CCSQ), respectively. Patients completed questionnaires at baseline, at Cycle3 (C3) and Cycle (C6) (XELOX) or at C4 and C8 visits (FOLFOX-6) and at their final visit.

Results:

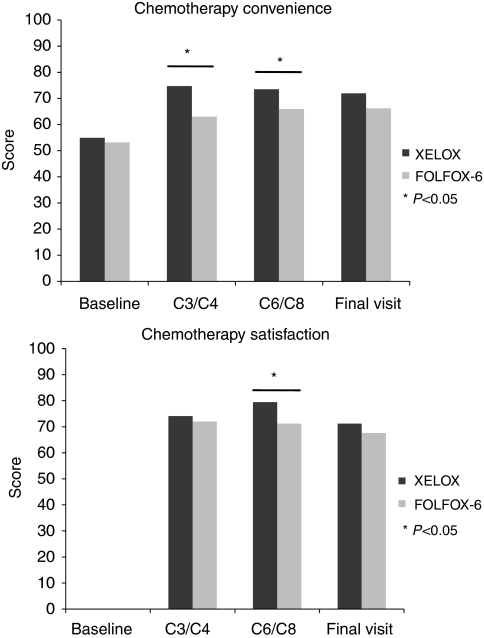

A total of 245 and 225 patients were assessed using QLQ-C30 and FACIT-CCSQ, respectively. The completion rates were >80%. Global QoL scores did not differ significantly between groups during the study. According to FACIT-CCSQ, XELOX seemed more convenient (C3/C4, P<0.001; C6/C8, P=0.009) and satisfactory to patients (C6/C8, P=0.003) than FOLFOX-6. At the final visit, XELOX patients spent fewer days on hospital visits (3.3 vs 5.3 days, P=0.045) and lost fewer hours of work/daily activities (10.2 vs 37.1 h lost, P=0.007).

Conclusion:

XELOX has a similar QoL profile, but seemed to be more convenient in terms of administration at certain time points and reduced time lost for work or other activities compared with FOLFOX-6.

Keywords: QoL, QLQ-C30, CCSQ-FACIT, colorectal cancer, capecitabine

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is one of the commonest cancers worldwide. It ranks third in terms of incidence (about 1 million new cases in 2002) after lung and breast cancer and fourth in terms of mortality (529 000 deaths in 2002) (Parkin et al, 2005). In Europe, CRC is the second most common cause of cancer-related death (203 700 deaths in 2004) after lung cancer (Boyle and Ferlay, 2005). Despite increased awareness about CRC and screening, about half of the patients still present with, or subsequently develop, metastatic disease.

Traditionally, 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) with or without leucovorin (LV) was the only drug used in the palliative treatment of patients with metastatic colorectal carcinoma (mCRC), but this treatment was reported to have a limited impact on survival. Recently, encouraging results have been obtained with capecitabine (Xeloda; F Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd, Basel, Switzerland), an oral fluoropyrimidine (Miwa et al, 1998; Schüller et al, 2000; Reigner et al, 2001). In the first-line treatment of mCRC, capecitabine as single-agent treatment was found to be at least equivalent to bolus 5-FU/LV in terms of time to disease progression and overall survival (OS), with higher response rates (Hoff et al, 2001; Van Cutsem et al, 2001; Cassidy et al, 2002). A series of phase-III studies were subsequently performed, which showed the non-inferiority of a combination of oxaliplatin with capecitabine compared with different 5-FU-based regimens plus oxaliplatin in patients with mCRC (Díaz-Rubio et al, 2007; Porschen et al, 2007; Cassidy et al, 2008; Rothenberg et al, 2008). On the basis of these results, capecitabine seemed to be an alternative to intravenous 5-FU.

In addition to efficacy data, patient quality of life (QoL), convenience and satisfaction are assuming increasing importance in the assessment of cancer therapies. Quality of life considerations are crucial to understanding the impact of cancer on the patient, especially when treatments are palliative rather than curative (Payne, 1992). On the basis of the American Society of Clinical Oncology, European Medicines Agency and Food and Drug Administration recommendations, health-related Quality-of-Life (HRQoL) questionnaires should be incorporated as secondary assessment criteria in controlled clinical trials conducted in patients with advanced cancers (ASCO, 1996; Beitz et al, 1996; EMEA, 2005). Among the available QoL questionnaires, the Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire-C30 (QLQ-C30) was developed and validated by the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer (Fayers and Bottomley, 2002). It has already been used in more than 3000 studies worldwide and is translated and validated in 81 languages (EORTC, 2008). Acceptability of QLQ-C30 is excellent in patients suffering from CRC (Conroy et al, 2002). The module ‘Chemotherapy Convenience and Satisfaction Questionnaire’ (CCSQ) of the Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy (FACIT) Measurement System, a collection of HRQoL questionnaires related to the management of chronic illnesses, measures the health-care satisfaction of patients (Webster et al, 2003; Yost et al, 2005a).

A randomised, open-label, multicentre, phase-III study was conducted to show the non-inferiority of oxaliplatin plus oral capecitabine (XELOX) vs FOLFOX-6 (oxaliplatin plus LV, then intravenous bolus 5-FU, followed by infusional 5-FU) in terms of efficacy in the first-line treatment of mCRC in France. In the per-protocol population, XELOX reached a similar overall response rate, the primary study end point, compared with FOLFOX-6. In both the per-protocol and intention-to-treat (ITT) populations, median progression-free survival (PFS) and median OS were also comparable, providing further support for the non-inferiority of XELOX vs FOLFOX-6. While considering safety, a similar proportion of patients discontinued chemotherapy because of adverse events in both treatment groups. This trial showed that XELOX and FOLFOX-6 were similar in terms of efficacy and safety (Ducreux et al, 2007). One of the secondary objectives of this phase-III study, which is the focus of this study, was to compare the QoL and health-care satisfaction of patients receiving either XELOX or FOLFOX-6 in the first-line treatment of mCRC, on the basis of the QLQ-C30 and FACIT-CCSQ.

Materials and methods

Study design

This was a phase-III prospective, randomised, multicentre, open-label trial. It was designed to show the non-inferiority of XELOX vs FOLFOX-6 in terms of efficacy in the first-line treatment of mCRC. Assessment of patients’ QoL and health-care satisfaction, as well as the health economic impact of both treatments, was the secondary objective. Eligible patients were assigned to a treatment group according to a centralised, balanced (1 : 1) and adaptive randomisation procedure. This procedure was based on a minimisation method with centre, Köhne predictive factors (Köhne et al, 2002) and previous chemotherapy as stratification factors.

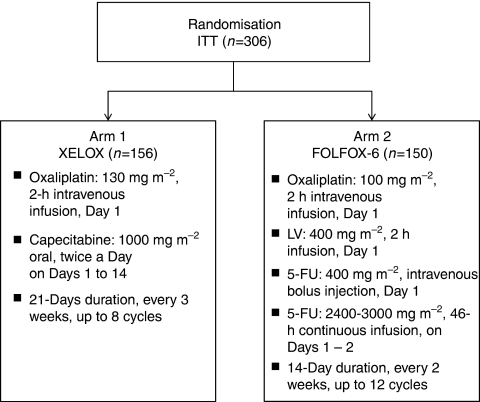

Two first-line chemotherapy regimens were tested: the XELOX regimen in arm 1 and the FOLFOX-6 regimen in arm 2 (Figure 1). The study comprised a screening visit (baseline) within 14 days before inclusion visit on Day 1 (just before Cycle 1), a treatment period and a follow-up period (including a study visit every 3 months) until the cutoff date, which was fixed at 18 months after the last patient's inclusion. Treatments were continued for 24 weeks (up to 8 cycles with XELOX or 12 cycles with FOLFOX-6) or until disease progression, whichever came first. Study treatment was discontinued in patients experiencing prolonged toxicity (>3 weeks). Dose modifications were made according to previous publications (Cassidy et al, 2004, 2006).

Figure 1.

Study treatment schema. 5-FU, 5-fluorouracil; LV, leucovorin.

Patients were randomised between May 2003 and August 2004 and followed up for 18 months until clinical cutoff in December 2006. The total study duration was 47 months. The study was conducted in France at 33 oncology centres and carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and Good Clinical Practice Guidelines. An Independent Ethics Committee approved the protocol. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients participating in the study.

Patient population

Adult patients (at least 18 years of age) with previously untreated, histologically proven mCRC (at least one measurable target lesion using Response Evaluation Criteria In Solid Tumors) (Therasse et al, 2000), an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status ⩽2 and a life expectancy of >3 months were eligible. Moreover, patients were required to have normal renal function and adequate haematological and hepatic function. Patients with rectal cancer and distant metastases, who had previously received preoperative irradiation on the primary tumour, were eligible if they had assessable non-irradiated metastases. Pregnant or breast-feeding women were excluded. Patients who had received neoadjuvant therapy within the last 6 months containing oxaliplatin, 5-FU or capecitabine, or patients with a history of neuropathy, or uncontrolled congestive heart failure, angina pectoris, hypertension or myocardial infarction within the last 12 months were excluded.

HRQoL measures

Assessment of HRQoL was based on QLQ-C30 (version 3) (EORTC, 2008) and the CCSQ module from the FACIT scale (Yost et al, 2005a). The QLQ-C30 has been previously shown to be a reliable and valid measure of the QoL of cancer patients in multicultural clinical research settings (Aaronson et al, 1993). The FACIT-CCSQ convenience items were worded to capture patients’ expectations of chemotherapy and took into account patients’ experience of chemotherapy, satisfaction items and patients’ use of health-care resources within the previous cycle. Both questionnaires were validated in the French language (Conroy et al, 2004; Rotonda et al 2008; www.facit.org).

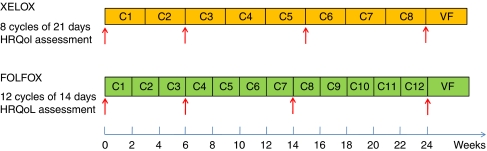

Both QLQ-C30 and FACIT-CCSQ were self-administered by patients enrolled into the study at baseline and at similar time points in both groups during the treatment period. Quality of life assessments were carried out at the same time as tumour imaging assessments and only during the treatment period, that is, at baseline, at Cycle 3 (C3) and Cycle 6 (C6) visits (XELOX) or Cycle 4 (C4) and Cycle 8 (C8) visits (FOLFOX-6) and final visit (Day 169). The timing schedule of QoL and satisfaction assessments is presented in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Questionnaires assessment schedule. Each red arrow corresponds to a questionnaire delivery. VF is final visit. The colour reproduction of the figure is available on the html full text version of the paper.

The QLQ-C30 used was a past week time-framed questionnaire, including 30 items and 15 independent subscores. At each QLQ-C30 assessment, five functional scales (physical, role, cognitive, emotional and social), a global QoL scale and nine symptom/item scales (fatigue, nausea and vomiting, pain, dyspnoea, sleep disturbance, appetite loss, constipation, diarrhoea and financial difficulties) were completed. Each was converted into a scale ranging from 0 to 100. For the QLQ-C30, higher scores represent a better health state for the five functional scales and for the global QoL scale, whereas lower scores represent a better health state for the symptom/item scores. The self-administered FACIT-CCSQ consists of 15 qualitative items relating to the patient's experience of chemotherapy and treatment without time limitations (except one past week time-framed item) and eight items (quantitative criteria) relating to the patient's use of health-care resources during the previous cycle. Most of the qualitative items were organised into three subscales related to chemotherapy convenience, concerns and satisfaction. Each scale and item was transformed into a scale ranging from 0 to 100. The FACIT-CCSQ was translated into the French language according to the FACIT procedure.

MID

The minimally important difference (MID) is defined as the smallest difference in score in the domain of interest that patients perceive as important, either beneficial or harmful, and that would lead the clinician to consider a change in the patient's management (Guyatt et al, 2002; Yost et al, 2005b). Considering the QLQ-C30, an MID of more than 10 points from baseline to a subsequent visit could be considered as being clinically significant (Osoba et al, 1998). Considering the FACIT-CCSQ, the MID was fixed at 6–9 points for convenience, 7–10 points for concerns and 5–9 points for satisfaction subscales (Yost et al, 2005a).

Statistical methods

The ITT population included all randomised patients meeting the inclusion criteria. Two HRQoL sets were considered:

QLQ-C30 set: defined as all ITT patients having an assessable QLQ-C30 (<50% of missing responses) at baseline,

FACIT-CCSQ set: defined as all ITT patients having an assessable FACIT-CCSQ (<50% of missing responses) at baseline.

The number of required patients in the study was based on the demonstration of non-inferiority in terms of efficacy between the XELOX and FOLFOX-6 arms. The total number of patients needed for randomisation in the per-protocol population was defined as 137 persons per group. When considering that 10% of patients could be excluded from the study, an ITT population of (137 × 2)/0.9=304 patients was required. The same number of patients was considered for the secondary objectives, including QoL and satisfaction assessments. Efficacy and safety assessments, as well as health economic results, are presented in detail in separate papers (Perrocheau et al, 2009; Ducreux et al, 2007).

At each assessment time, the 15 scales of the QLQ-C30 were computed and analysed in the QLQ-C30 set, whereas the items of the FACIT-CCSQ were analysed in the FACIT-CCSQ set. For both questionnaires, missing items were estimated according to their respective scoring manuals when feasible (Fayers et al, 2001; www.facit.org). For each item of both questionnaires, the baseline value and values at subsequent visits were provided for each study arm using descriptive statistics. The differences between arms were tested with an analysis of variance test.

Multivariate analyses of OS and PFS were performed using a Cox model with a non-inferiority margin for the hazard ratio fixed at 1.75 and a power of 90%. The analyses included several variables such as age, Köhne score, time interval between CRC diagnosis and metastatic disease, type of cancer, QoL and health-care satisfaction. Differences in QoL and morbidity were analysed using analysis of variance, accounting for differences in survival between groups. Mortality was compared using Kaplan–Meier curves and log–rank statistics. The primary analysis of QoL data was performed using a mixed-models analysis of variances for repeated measures.

The reliability of the multi-item scales of QLQ-C30 and FACIT-CCSQ was assessed using Cronbach α coefficient for internal consistency (Cronbach, 1951). A Cronbach α coefficient >0.5 was considered as acceptable reliability, whereas a Cronbach α coefficient >0.7 was considered as good reliability (Nunally and Berstein, 1994).

Results

Study population

A total of 306 patients were randomised: 245 patients (XELOX n=126, FOLFOX-6 n=119) answered the QLQ-C30 and 225 patients (XELOX n=111, FOLFOX-6 n=114) answered FACIT-CCSQ. The characteristics at baseline of these patients are presented in Table 1. No significant differences between XELOX and FOLFOX-6 groups regarding socio-demographic data, mCRC characteristics and other baseline characteristics were observed in the HRQoL sets.

Table 1. Baseline demographic characteristics of patients.

|

EORTC QLQ-C30

|

FACIT-CCSQ

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| XELOX group N=126 | FOLFOX-6 group N=119 | P-value | XELOX group N=111 | FOLFOX-6 group N=114 | P-value | ||

| Age (years) | n missing | 0 | 0 | 0.59 | 0 | 0 | 0.47 |

| Mean (s.d.) | 65.8 (10.0) | 65.6 (8.9) | 66.0 (9.8) | 65.4 (9.4) | |||

| Gender | n missing | 0 | 0 | 0.20 | 0 | 0 | 0.10 |

| Male | n (%) | 81 (64.3) | 67 (56.3) | 74 (66.7) | 64 (56.1) | ||

| Female | n (%) | 45 (35.7) | 52 (43.7) | 37 (33.3) | 50 (43.9) | ||

| BMI (kg m−2) | n missing | 3 | 4 | 0.27 | 2 | 4 | 0.57 |

| Mean (s.d.) | 24.6 (4.2) | 25.3 (4.9) | 24.5 (4.1) | 25.1 (5.0) | |||

| Localisation in Francea | n missing | 0 | 0 | 0.08 | 0 | 0 | 0.06 |

| Paris | n (%) | 9 (7.1) | 21 (17.6) | 9 (8.1) | 22 (19.3) | ||

| Northwest | n (%) | 48 (38.1) | 37 (31.1) | 34 (30.6) | 25 (21.9) | ||

| Northeast | n (%) | 33 (26.2) | 31 (26.1) | 31 (27.9) | 31 (27.2) | ||

| Southeast | n (%) | 25 (19.8) | 25 (21.0) | 23 (20.7) | 28 (24.6) | ||

| Southwest | n (%) | 11 (8.7) | 5 (4.2) | 14 (12.6) | 8 (7.0) | ||

| ECOG PS | n missing | 0 | 0 | 0.89 | 0 | 0 | 0.76 |

| 0–1 | n (%) | 116 (92.1) | 109 (91.6) | 101 (91.0) | 105 (92.1) | ||

| 2 | n (%) | 10 (7.9) | 10 (8.4) | 10 (9.0) | 9 (7.9) | ||

| Tumour primary site | n missing | 0 | 0 | 0.43 | 0 | 0 | 0.54 |

| Colon | n (%) | 76 (60.3) | 75 (63.0) | 66 (59.5) | 69 (60.5) | ||

| Colorectum | n (%) | 28 (22.2) | 30 (25.2) | 26 (23.4) | 31 (27.2) | ||

| Rectum | n (%) | 22 (17.5) | 14 (11.8) | 19 (17.1) | 14 (12.3) | ||

Abbreviations: BMI=body mass index; CCSQ=Chemotherapy Convenience and Satisfaction Questionnaire; ECOG PS=Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status; EORTC=European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer; FACIT=Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy; N=number of exposed patients; QLQ-C30=Quality of Life Questionnaire-C30.

These five French areas correspond to the areas defined by the five area codes (01, 02, 03, 04 and 05).

QoL results

Completion rate

The completion rate of QoL assessments referred to the number of patients participating at the related visit. Overall, completion rates were satisfactory at the different visits, and were >80% for both questionnaires and for treatment groups.

Missing item rate

The missing item rate referred to the number of missing items of data among received forms at the related visit. Overall, the missing item rates for both questionnaires were not significantly different between XELOX and FOLFOX-6 at baseline and at subsequent visits.

The European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer QLQ-C30 scores

No relevant differences were observed between the FOLFOX-6 and XELOX arms at baseline and at subsequent visits. Compared with the FOLFOX-6 group, patients had significantly less dyspnoea in the XELOX group (18.0 (13.9; 22.1)90% vs 25.4 (20.9; 29.8)90%; P=0.017), but significantly more sleep disturbances (38.4 (33.3; 43.5)90% vs 29.1 (24.4; 33.7)90%; P=0.036) at baseline. For all subsequent evaluations (C3/C4, C6/C8 and final visit), the QLQ-C30 functional and symptom scores were not significantly different between the XELOX and FOLFOX-6 arms. Results of the QLQ-C30 are summarised in Table 2. Moreover, when focusing on sleep disturbances and dyspnoea items, there were no clinically relevant changes between baseline and final visit for either group, as the changes in scores were <10.

Table 2. EORTC QLQ-C30 questionnaire assessment in the QLQ-C30 set (N=245).

|

XELOX group, n=126

|

FOLFOX-6 group, n=119

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EORTC QLQ-C30 | n | MV (%) | Mean (s.d.) | n | MV (%) | Mean (s.d.) | *P-value |

| Physical functioning (%) | |||||||

| Baseline | 126 | 0.0 | 80.7 (20.2) | 118 | 0.8 | 79.1 (21.9) | 0.952 |

| C3/C4 | 98 | 0.0 | 80.5 (22.0) | 96 | 1.0 | 78.9 (19.0) | 0.225 |

| C6/C8 | 78 | 0.0 | 80.0 (18.5) | 72 | 2.7 | 79.5 (18.6) | 0.645 |

| Final visit | 63 | 0.0 | 75.9 (22.0) | 65 | 0.0 | 74.9 (21.0) | 0.631 |

| Role functioning (%) | |||||||

| Baseline | 124 | 1.6 | 71.2 (31.8) | 116 | 2.5 | 68.2 (32.3) | 0.484 |

| C3/C4 | 98 | 0.0 | 73.8 (28.7) | 96 | 1.0 | 67.4 (30.6) | 0.121 |

| C6/C8 | 78 | 0.0 | 74.8 (28.9) | 73 | 1.4 | 70.5 (27.0) | 0.198 |

| Final visit | 62 | 1.6 | 69.9 (32.1) | 65 | 0.0 | 65.1 (29.4) | 0.206 |

| Cognitive functioning (%) | |||||||

| Baseline | 123 | 2.4 | 83.7 (20.5) | 118 | 0.8 | 83.2 (22.2) | 0.961 |

| C3/C4 | 98 | 0.0 | 85.0 (19.9) | 96 | 1.0 | 82.3 (20.5) | 0.247 |

| C6/C8 | 78 | 0.0 | 79.3 (23.1) | 74 | 0.0 | 82.0 (19.3) | 0.641 |

| Final visit | 63 | 0.0 | 78.6 (19.3) | 64 | 1.5 | 77.7 (19.5) | 0.631 |

| Emotional functioning (%) | |||||||

| Baseline | 124 | 1.6 | 68.8 (25.2) | 117 | 1.7 | 68.0 (24.5) | 0.715 |

| C3/C4 | 98 | 0.0 | 78.6 (20.2) | 96 | 1.0 | 75.2 (22.0) | 0.333 |

| C6/C8 | 78 | 0.0 | 79.2 (20.4) | 74 | 0.0 | 75.6 (21.9) | 0.285 |

| Final visit | 62 | 1.6 | 72.7 (23.8) | 64 | 1.5 | 69.7 (24.2) | 0.438 |

| Social functioning (%) | |||||||

| Baseline | 123 | 2.4 | 77.2 (30.1) | 116 | 2.5 | 76.1 (27.6) | 0.461 |

| C3/C4 | 98 | 0.0 | 79.3 (24.8) | 96 | 1.0 | 72.9 (26.2) | 0.058 |

| C6/C8 | 78 | 0.0 | 78.8 (25.4) | 74 | 0.0 | 78.2 (25.3) | 0.924 |

| Final visit | 63 | 0.0 | 73.5 (28.7) | 64 | 1.5 | 71.6 (27.0) | 0.539 |

| Global quality of life scale (%) | |||||||

| Baseline | 123 | 2.4 | 62.4 (22.8) | 116 | 2.5 | 59.8 (20.9) | 0.372 |

| C3/C4 | 98 | 0.0 | 66.5 (22.2) | 96 | 1.0 | 62.2 (18.0) | 0.050 |

| C6/C8 | 78 | 0.0 | 64.5 (21.7) | 73 | 1.4 | 62.7 (19.0) | 0.349 |

| Final visit | 63 | 0.0 | 58.1 (22.8) | 63 | 3.1 | 60.4 (19.1) | 0.449 |

| Fatigue (%) | |||||||

| Baseline | 125 | 0.8 | 40.3 (29.1) | 117 | 1.7 | 38.4 (27.6) | 0.626 |

| C3/C4 | 98 | 0.0 | 36.9 (24.9) | 97 | 0.0 | 40.3 (26.9) | 0.510 |

| C6/C8 | 78 | 0.0 | 38.1 (27.5) | 73 | 1.4 | 40.3 (26.9) | 0.536 |

| Final visit | 63 | 0.0 | 45.1 (27.2) | 65 | 0.0 | 41.5 (25.9) | 0.475 |

| Nausea and vomiting (%) | |||||||

| Baseline | 125 | 0.8 | 6.0 (14.9) | 118 | 0.8 | 8.2 (19.5) | 0.395 |

| C3/C4 | 98 | 0.0 | 11.9 (19.6) | 97 | 0.0 | 12.2 (22.2) | 0.738 |

| C6/C8 | 78 | 0.0 | 10.5 (17.8) | 73 | 1.4 | 13.0 (21.2) | 0.687 |

| Final visit | 63 | 0.0 | 10.3 (18.3) | 65 | 0.0 | 10.3 (17.6) | 0.991 |

| Pain (%) | |||||||

| Baseline | 126 | 0.0 | 23.3 (27.8) | 118 | 0.8 | 24.0 (27.6) | 0.707 |

| C3/C4 | 98 | 0.0 | 19.0 (24.5) | 97 | 0.0 | 18.7 (23.0) | 0.949 |

| C6/C8 | 78 | 0.0 | 20.9 (28.9) | 74 | 0.0 | 17.3 (20.0) | 0.908 |

| Final visit | 63 | 0.0 | 31.2 (33.5) | 65 | 0.0 | 25.4 (26.4) | 0.512 |

| Dyspnoea (%) | |||||||

| Baseline | 123 | 1.6 | 18.0 (27.3) | 117 | 1.7 | 25.4 (28.9) | 0.017 |

| C3/C4 | 97 | 1.0 | 18.6 (25.9) | 95 | 2.1 | 18.6 (24.7) | 0.890 |

| C6/C8 | 77 | 1.3 | 18.6 (25.6) | 73 | 1.4 | 19.2 (24.8) | 0.774 |

| Final visit | 62 | 1.6 | 21.0 (27.1) | 65 | 0.0 | 20.0 (24.9) | 0.974 |

| Insomnia (%) | |||||||

| Baseline | 125 | 0.8 | 38.4 (34.1) | 117 | 1.7 | 29.1 (30.2) | 0.036 |

| C3/C4 | 98 | 0.0 | 26.5 (31.4) | 97 | 0.0 | 25.4 (29.6) | 0.916 |

| C6/C8 | 78 | 0.0 | 25.6 (31.7) | 72 | 2.7 | 20.4 (26.6) | 0.391 |

| Final visit | 63 | 0.0 | 28.6 (33.3) | 65 | 0.0 | 24.6 (27.2) | 0.725 |

| Appetite loss (%) | |||||||

| Baseline | 125 | 0.8 | 24.3 (32.9) | 116 | 2.5 | 26.1 (33.4) | 0.550 |

| C3/C4 | 98 | 0.0 | 21.4 (29.2) | 97 | 0.0 | 24.4 (34.2) | 0.798 |

| C6/C8 | 78 | 0.0 | 23.5 (30.4) | 73 | 1.4 | 19.4 (28.4) | 0.424 |

| Final visit | 62 | 1.6 | 31.2 (36.1) | 63 | 3.1 | 20.6 (30.8) | 0.106 |

| Constipation (%) | |||||||

| Baseline | 124 | 1.6 | 17.2 (29.6) | 117 | 1.7 | 18.5 (26.8) | 0.312 |

| C3/C4 | 95 | 3.1 | 13.0 (21.4) | 95 | 2.1 | 21.1 (28.8) | 0.065 |

| C6/C8 | 77 | 1.3 | 19.0 (27.3) | 73 | 1.4 | 14.6 (24.8) | 0.286 |

| Final visit | 61 | 3.2 | 22.4 (31.5) | 64 | 1.6 | 21.4 (28.1) | 0.860 |

| Diarrhoea (%) | |||||||

| Baseline | 124 | 1.6 | 16.7 (26.0) | 116 | 2.5 | 15.8 (26.2) | 0.700 |

| C3/C4 | 98 | 0.0 | 21.1 (28.1) | 96 | 1.0 | 21.2 (30.3) | 0.800 |

| C6/C8 | 77 | 1.3 | 21.2 (31.5) | 74 | 0.0 | 16.2 (25.4) | 0.506 |

| Final visit | 63 | 0.0 | 15.9 (27.3) | 64 | 1.6 | 7.8 (18.5) | 0.072 |

| Financial difficulties (%) | |||||||

| Baseline | 123 | 2.4 | 8.9 (23.4) | 114 | 4.2 | 10.8 (24.5) | 0.515 |

| C3/C4 | 98 | 0.0 | 7.1 (19.3) | 95 | 2.1 | 9.1 (20.9) | 0.477 |

| C6/C8 | 78 | 0.0 | 8.5 (21.8) | 74 | 0.0 | 11.3 (24.2) | 0.289 |

| Final visit | 63 | 0.0 | 10.1 (22.1) | 64 | 1.6 | 12.0 (22.5) | 0.479 |

Abbreviations: C3, C4, C6, C8=Cycles 3, 4, 6 and 8; EORTC=European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer; %MV=percentage of missing values; QLQ-C30=Quality of Life Questionnaire-C30.

*P value: Student's t-test or Wilcoxon test for independent samples. Bold values indicate P<0.05.

FACIT-CCSQ scores

No relevant differences between groups were observed at baseline in the FACIT-CCSQ scales. Compared with the FOLFOX-6 group, patients in the XELOX group reported significantly better chemotherapy convenience at C3/C4 (74.7 (71.5; 77.9)90% vs 63.0 (59.2; 66.7)90%; P<0.001) and C6/C8 (73.5 (69.6; 77.3)90% vs 65.9 (62.3; 69.4)90%; P=0.009), as well as better chemotherapy satisfaction at C6/C8 (79.4 (75.3; 83.6)90% vs 71.2 (67.3; 75.1)90%; P=0.003) (Figure 3). At the final visit, XELOX patients spent fewer days on hospital visits (3.3 days (1.5; 5.1)90% vs 5.3 days (3.4; 7.1)90%; P=0.045) and saved more hours of work or usual daily activities (10.2 h lost (3.5; 16.9)90% in the XELOX group vs 37.1 h lost (17.4; 56.8)90% in the FOLFOX-6 group, P=0.007). No other significant differences between groups were shown for this questionnaire. Results of FACIT-CCSQ are summarised in Table 3.

Figure 3.

FACIT-CCSQ assessment of chemotherapy convenience and satisfaction in patients receiving either XELOX or FOLFOX-6. CCSQ, Chemotherapy Convenience and Satisfaction Questionnaire; FACIT, Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy.

Table 3. FACIT-CCSQ questionnaire assessment in the FACIT-CCSQ set (N=225).

|

XELOX group, n=111

|

FOLFOX-6 group, n=114

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FACIT-CCSQ | n | MV (%) | Mean (s.d.) | n | MV (%) | Mean (s.d.) | *P-value |

| Chemotherapy convenience | |||||||

| Baseline | 111 | 0.0 | 54.9 (23.3) | 112 | 1.8 | 53.2 (19.1) | 0.471 |

| C3/C4 | 93 | 0.0 | 74.7 (18.5) | 88 | 0.0 | 63.0 (21.0) | <0.001 |

| C6/C8 | 65 | 1.5 | 73.5 (18.6) | 72 | 0.0 | 65.9 (18.2) | 0.009 |

| Final visit | 61 | 0.0 | 71.9 (19.2) | 63 | 0.0 | 66.2 (18.0) | 0.081 |

| Chemotherapy concerns | |||||||

| Baseline | 111 | 0.0 | 61.4 (19.3) | 113 | 0.9 | 58.9 (19.8) | 0.492 |

| C3/C4 | 93 | 0.0 | 76.3 (19.6) | 88 | 0.0 | 72.7 (20.6) | 0.186 |

| C6/C8 | 66 | 0.0 | 75.3 (19.8) | 72 | 0.0 | 73.9 (17.7) | 0.454 |

| Final visit | 61 | 0.0 | 71.6 (19.7) | 62 | 1.6 | 67.6 (19.9) | 0.289 |

| Chemotherapy satisfaction | |||||||

| Baseline | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| C3/C4 | 84 | 10.7 | 74.1 (21.9) | 79 | 11.4 | 72.0 (20.0) | 0.311 |

| C6/C8 | 63 | 4.8 | 79.4 (19.7) | 66 | 9.1 | 71.2 (18.9) | 0.003 |

| Final visit | 52 | 17.3 | 71.2 (20.5) | 55 | 14.5 | 67.6 (20.2) | 0.296 |

| I worry that my chemotherapy will not be effective (%) | |||||||

| Baseline | 108 | 2.7 | 74.8 (29.3) | 110 | 3.6 | 77.3 (25.7) | 0.707 |

| Final visit | 60 | 1.6 | 73.8 (30.3) | 60 | 5.0 | 76.7 (26.4) | 0.751 |

| My chemotherapy schedule is stressful to my family (%) | |||||||

| Baseline | 110 | 0.9 | 54.5 (29.6) | 114 | 0.0 | 57.0 (28.3) | 0.571 |

| Final visit | 61 | 0.0 | 69.3 (30.1) | 61 | 3.3 | 69.3 (25.2) | 0.703 |

| Within past week | |||||||

| I am content with the quality of my life right now (%) | |||||||

| Baseline | 107 | 3.7 | 52.3 (28.0) | 109 | 4.6 | 50.7 (26.2) | 0.553 |

| Final visit | 58 | 5.2 | 46.1 (28.4) | 59 | 6.8 | 45.3 (23.0) | 0.711 |

| Within past cycle | |||||||

| Hospital visits | |||||||

| Final visit | 39 | 36.1 | 1.9 (4.5) | 40 | 36.5 | 2.1 (4.6) | 0.974 |

| Emergency room admissions | |||||||

| Final visit | 31 | 49.2 | 0.0 (0.0) | 33 | 47.6 | 0.0 (0.0) | 1.000 |

| Physician visits | |||||||

| Final visit | 38 | 60.4 | 0.6 (1.7) | 37 | 41.3 | 0.3 (1.0) | 0.295 |

| Number of days for a usual hospital visit | |||||||

| Final visit | 31 | 49.2 | 3.3 (5.9) | 27 | 57.1 | 5.3 (5.6) | 0.045 |

| Number of hours for a usual emergency room admission | |||||||

| Final visit | 22 | 63.9 | 0.2 (0.9) | 17 | 73.0 | 0.5 (1.5) | 0.426 |

| Number of hours for a usual physician visit within past cycle? | |||||||

| Final visit | 27 | 55.7 | 0.6 (1.0) | 26 | 58.7 | 1.4 (5.9) | 0.407 |

| How many hours have you lost for your work or usual daily activities? | |||||||

| Final visit | 33 | 45.9 | 10.2 (22.6) | 34 | 46.0 | 37.1 (67.9) | 0.007 |

| How many hours have your friends or your family lost for their work or usual daily activities? | |||||||

| Final visit | 36 | 41.0 | 3.1 (4.6) | 32 | 49.2 | 20.0 (53.0) | 0.059 |

Abbreviations: C3, C4, C6, C8=Cycles 3, 4, 6 and 8; CCSQ=Chemotherapy Convenience and Satisfaction Questionnaire; FACIT=Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy; %MV=percentage of missing values.

*P-value: Student's t-test or Wilcoxon test for independent samples. Bold values indicate P<0.05.

Moreover, as the MID reached more than 6 points for convenience and more than 5 points for the satisfaction subscales (Yost et al, 2005a), the differences observed between the XELOX and FOLFOX-6 groups could be considered as clinically relevant for satisfaction with XELOX at C6/C8, as well as for convenience with XELOX at C3/C4 and C6/C8 visits.

Multivariate analysis

The results of multivariate analyses showed that all items of the QLQ-C30 had a significant correlation with PFS (except for the cognitive scale, emotional scale and financial difficulties item) and OS (except for the financial difficulties item).

The FACIT-CCSQ items had no correlation with PFS. Only the global quality-of-life score of FACIT-CCSQ had a significant correlation with OS.

Reliability of scales

All QLQ-C30 multi-item scales, except for the cognitive functional scale at the final visit, showed at least acceptable reliability (data not shown). The Cronbach α coefficients for the multi-item scales of FACIT-CCSQ showed good reliability on an average and at least acceptable reliability (data not shown).

Discussion

This study was the first clinical trial to use both the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer QLQ-C30 and CCSQ module from FACIT to assess patient QoL and satisfaction with first-line treatment of mCRC. The objective of this study was to evaluate patients’ QoL and health-care satisfaction in the XELOX and FOLFOX-6 groups. Patients in the XELOX group reported significantly better convenience at C3/C4 and C6/C8 visits, as well as better satisfaction at C3/C4, than did patients in the FOLFOX-6 group according to FACIT-CCSQ. Moreover, XELOX patients spent fewer days on hospital visits and saved more hours of work or activity time at the final visit. No differences between groups were shown using QLQ-C30, but the FACIT-CCSQ highlighted that patients seemed more satisfied in the XELOX group than in the FOLFOX-6 group at certain time points. The assessment of internal reliability, based on Cronbach α coefficients, revealed a good level of construct validity of both questionnaires.

No clinically relevant differences in QoL between groups were shown using QLQ-C30. This result is not surprising, as XELOX and FOLFOX-6 have similar safety and efficacy profiles (Ducreux et al, 2007). Our study showed that the FACIT-CCSQ assessment showed a significant difference between the two treatment regimens in days for hospital visits and hours lost for work or other activities. However, no difference was found between the two regimens in any of the measures for ‘functioning’ in the QLQ-C30 assessment. This could be partly explained by the fact that patients answered the QLQ-C30 just before their hospital visit. Moreover, the assessment related to the previous week when the patient did not receive any chemotherapy. Multivariate analyses showed a significant correlation between most of the QLQ-C30 items and PFS, as well as OS. These results are consistent with those of other studies. Indeed, it has been shown that several QLQ-C30 scales have prognostic value for survival in mCRC (Efficace et al, 2006; Efficace et al, 2008).

The assessment of QoL and satisfaction of mCRC patients was a secondary objective of this clinical trial. In this context, these data have some limitations. The baseline QLQ-C30 profiles were similar in the XELOX and FOLFOX-6 arms, except for dyspnoea and sleep disturbances. Patients had significantly less dyspnoea and more sleep disturbances in the XELOX group than in the FOLFOX-6 group at baseline, although these differences were not clinically relevant as the differences in scores were less than the MID of 10 points. When considering the changes from baseline to final visit, these between-group differences were no longer evident. Finally, completion rates and item missing rates at different time points were not different between study arms, providing further support for the comparability of treatment groups. The decrease in the number of patients at subsequent visits was similar in both groups and could be partly explained by the patient's tumour status.

Despite these limitations, the results are consistent with other QoL and patient preference studies of oral fluoropyrimidines vs intravenous 5-FU/LV in CRC. First, a series of studies have shown the preference of patients for oral treatment (Borner et al, 2002; Kopec et al, 2007). For example, Kopec et al (2007) showed similar results in patients with stage II/III carcinoma of the colon who received oral uracil/ftorafur (UFT) plus LV or standard intravenous 5-FU/LV as adjuvant chemotherapy. Health-related Quality-of-Life was measured with the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Colorectal (FACT-C), the Short Form-36 Vitality Scale and a Quality of Life Rating Scale. Patients perceived adjuvant treatment with UFT/LV as being more convenient than standard IV treatment with 5-FU/LV. Both regimens were well tolerated and did not differ in their impact on HRQoL. Moreover, two recent studies underlined the preference of patients for capecitabine over 5-FU. Pelusi (2006) confirmed that the oral approach was preferred by patients because of its convenience (fewer medical office visits, no intravenous access required) and by clinicians because it eliminated the risk of complications, such as infection and clotting associated with venous access devices and infusion pumps. In another study conducted by Twelves et al (2006), 97 patients with previously untreated advanced or mCRC were randomised to receive capecitabine, followed by intravenous 5-FU/LV (Mayo Clinic, in-patient de Gramont or outpatient modified de Gramont regimens), or intravenous 5-FU/LV followed by capecitabine. Quality of life was assessed with the FACT-C questionnaire. The results confirmed that the majority of patients with mCRC preferred oral therapy.

Health economic results based on the current clinical trial further showed that XELOX significantly decreased the direct treatment costs of mCRC patients, as well as hospital resource consumption, in comparison with FOLFOX-6 (Perrocheau et al, 2009). Considering clinical and economic impacts, the XELOX regimen seems to be a relevant alternative to FOLFOX-6 in the first-line treatment of mCRC.

Conclusion

This study was the first clinical trial to evaluate QoL and health-care satisfaction in patients receiving XELOX in the first-line treatment of mCRC. XELOX has a similar QoL profile, but seems to be more convenient in terms of administration at certain time points and reduced time lost for work or other activities compared with FOLFOX-6. Therefore, capecitabine, used in the XELOX regimen, clearly represents an effective and well-tolerated oral alternative to intravenous 5-FU/LV.

Acknowledgments

Financial support for this research was provided by Roche. We thank st[è]ve consultants for writing the paper and for performing additional statistical analyses (test of internal validity of both questionnaires and completion rate/missing data analysis). In addition to the investigators in the author list, we acknowledge the following investigators who also participated in this trial: N-E Achour, Clinique Pasteur; J Alexandre, Hôpital Cochin, Paris; Y Bécouarn, Institut Bergonié, Bordeaux; A Bidault, Hôpital de Bicêtre, Le Kremlin-Bicêtre; C Boaziz, Clinique Claude Bernard, Ermont; L Cany, Clinique Francheville, Périgueux; I Cumin, Centre Hospitalier Bretagne Sud, Lorient; F Cvitkovic, Centre René Huguenin, Saint-Cloud; P Dalivoust, Clinique La Casamance, Aubagne; JP Delord, Centre Claudius Régaud, Toulouse; P De Guiral, Centre Hospitalier Général, Saint Nazaire; MP Galais, Centre François Baclesse and Centre Hospitalier Universitaire, Caen; F Guichard, Polyclinique Bordeaux Nord, Bordeaux; F Husseini, Hôpital Pasteur, Colmar; M Nadrigny, Laurent Clinique du Château, Garches; S Négrier, Centre Léon Bérard, Lyon; B Paillot, Hôpital Charles Nicolle, Rouen; P Piedbois, Hôpital Henri Mondor, Créteil; L Poincloux, Centre Hospitalier Universitaire Hôtel Dieu, Clermont Ferrand; JM Tigaud, Centre Hospitalier Intercommunal, Villeneuve-Saint-Georges; L Vayre, Centre Hospitalier, Brive; J Vignoud, Centre Libéral de Radiothérapie et d’Oncologie Médicale, Béziers; JP Wagner, Cabinet d’Oncologie Médicale, Strasbourg, France. We also acknowledge the major contribution made by Sandrine Kraemer to this trial.

References

- Aaronson NK, Ahmedzai S, Bergman B, Bullinger M, Cull A, Duez NJ, Filiberti A, Flechtner H, Fleishman SB, de Haes JC, Kaasa S, Klee M, Osoba D, Razavi D, Rofe PB, Schraub S, Sneeuw K, Sullivan M, Takeda F (1993) The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer QLQ-C30: a quality-of-life instrument for use in international clinical trials in oncology. J Natl Cancer Inst 85: 365–376 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Society of Clinical Oncology (1996) Outcomes of cancer treatment for technology assessment and cancer treatment guidelines. J Clin Oncol 14: 671–679 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beitz J, Gnecco C, Justice R (1996) Quality-of-life end points in cancer clinical trials: the US Food and Drug Administration perspective. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogra 20: 7–9 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borner MM, Schoffski P, de Wit R, Caponigro F, Comella G, Sulkes A, Greim G, Peters GJ, van der Born K, Wanders J, de Boer RF, Martin C, Fumoleau P (2002) Patient preference and pharmacokinetics of oral modulated UFT versus intravenous fluorouracil and leucovorin: a randomised crossover trial in advanced colorectal cancer. Eur J Cancer 38: 349–358 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyle P, Ferlay J (2005) Cancer incidence and mortality in Europe, 2004. Ann Oncol 16: 481–488 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cassidy J, Clarke S, Díaz-Rubio E, Scheithauer W, Figer A, Wong R, Koski S, Lichinitser M, Yang TS, Rivera F, Couture F, Sirzén F, Saltz L (2008) A randomized phase III study of capecitabine plus oxaliplatin (XELOX) versus fluorouracil/folinic acid plus oxaliplatin (FOLFOX-4) as first-line therapy for metastatic colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol 26: 2006–2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cassidy J, Douillard JY, Twelves C, McKendrick JJ, Scheithauer W, Bustová I, Johnston PG, Lesniewski-Kmak K, Jelic S, Fountzilas G, Coxon F, Díaz-Rubio E, Maughan TS, Malzyner A, Bertetto O, Beham A, Figer A, Dufour P, Patel KK, Cowell W, Garrison LP (2006) Pharmacoeconomic analysis of adjuvant oral capecitabine versus intravenous 5-FU/LV in Dukes’ C colon cancer: the X-ACT trial. Br J Cancer 94: 1122–1129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cassidy J, Twelves C, Van Cutsem E, Hoff P, Bajetta E, Boyer M, Bugat R, Burger U, Garin A, Graeven U, Mckendrick J, Maroun J, Marshall J, Osterwalder B, Perez-Manga G, Rosso R, Rougier P, Schilsky RL (2002) First-line oral capecitabine therapy in metastatic colorectal cancer: a favorable safety profile compared with intravenous 5-fluorouracil/leucovorin. Ann Oncol 13: 566–575 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cassidy J, Tabernero J, Twelves C, Brunet R, Butts C, Conroy T, Debraud F, Figer A, Grossmann J, Sawada N, Schöffski P, Sobrero A, Van Cutsem E, Díaz-Rubio E (2004) XELOX (capecitabine plus oxaliplatin): active first-line therapy for patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol 22: 2084–2091 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conroy T, Guillemin F, Kaminsky MC (2002) Measure of quality of life in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer: techniques and main results. Rev Med Interne 23: 703–716 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conroy T, Mercier M, Bonneterre J, Luporsi E, Lefebvre JL, Lapeyre M, Puyraveau M, Schraub S (2004) French version of FACT-G: validation and comparison with other cancer-specific instruments. Eur J Cancer 40: 2243–2252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cronbach LJ (1951) Coefficient alpha and internal structure of tests. Psychometrika 16: 297–334 [Google Scholar]

- Díaz-Rubio E, Tabernero J, Góómez-España A, Massutí B, Sastre J, Chaves M, Abad A, Carrato A, Queralt B, Reina JJ, Maurel J, González-Flores E, Aparicio J, Rivera F, Losa F, Aranda E (2007) Phase III study of capecitabine plus oxaliplatin versus continuous infusion fluorouracil plus oxaliplatin as first-line therapy in metastatic colorectal cancer: final report of the Spanish Cooperative Group for the Treatment of Digestive Tumors trial. J Clin Oncol 25: 4224–4230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ducreux M, Bennouna J, Hebbar M, Ychou M, Lledo G, Conroy T, Adenis A, Faroux R, Rebischung C, Douillard JY (2007). Efficacy and safety findings from a randomized phase III study of capecitabine (X) + oxiplatin (O) (XELOX) vs. infusional 5-FU/LV + O (FOLFOX-6) for metastatic colorectal cancer (MCRC). J Clin Oncol 25 (18S) (Suppl. Part I): 170s: abstract 4029 [Google Scholar]

- Efficace F, Bottomley A, Coens C, Van Steen K, Conroy T, Schöffski P, Schmoll H, Van Cutsem E, Köhne CH (2006) Does a patient's self-reported health-related quality of life predict survival beyond key biomedical data in advanced colorectal cancer? Eur J Cancer 42(1): 42–49. [published erratum appears in: Eur J Cancer 2007; 43: 633] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Efficace F, Innominato PF, Bjarnason G, Coens C, Humblet Y, Tumolo S, Genet D, Tampellini M, Bottomley A, Garufi C, Focan C, Giacchetti S, Lévi F (2008) Validation of patient's self-reported social functioning as an independent prognostic factor for survival in metastatic colorectal cancer patients: results of an international study by the Chronotherapy Group of the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer. J Clin Oncol 26: 2020–2026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- European Medicines Agency. Committee for medicinal products for human use (2005) Guideline on the evaluation of anticancer medicinal products in man. Available at: http://www.emea.europa.eu/pdfs/human/ewp/020595en.pdf

- European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (2008) EORTC QLQ-C3. Available at: http://groups.eortc.be/qol/questionnaires_qlqc30.htm

- Fayers P, Aaronson N, Bjordal K, Groenvold M, Curran D, Bottomley A on behalf of the EORTC Quality of Life Group (2001) EORTC QLQ-C30 Scoring Manual. (3rd edn). European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer: Brussels. http://groups.eortc.be/qol/documentation_manuals.htm [Google Scholar]

- Fayers P, Bottomley A (2002) Quality of life research within the EORTC – the EORTC QLQ-C30. Eur J Cancer 38: S125–S133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guyatt GH, Osoba D, Wu AW, Wyrwich KW, Norman GR (2002) Methods to explain the clinical significance of health status measures. Mayo Clin Proc 77: 371–383 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoff PM, Ansari R, Batist G, Cox J, Kocha W, Kuperminc M, Maroun J, Walde D, Weaver C, Harrison E, Burger HU, Osterwalder B, Wong AO, Wong R (2001) Comparison of oral capecitabine versus intravenous fluorouracil plus leucovorin as first-line treatment in 605 patients with metastatic colorectal cancer: results of a randomized phase III study. J Clin Oncol 19: 2282–2292 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Köhne CH, Cunningham D, Di Costanzo Glimelius B, Blijham G, Aranda E, Scheithauer W, Rougier P, Palmer M, Wils J, Baron B, Pignatti F, Schöffski P, Micheel S, Hecker H (2002) Clinical determinants of survival in patients with 5-fluorouracil-based treatment for metastatic colorectal cancer: results of a multivariate analysis of 3825 patients. Ann Oncol 13: 308–317 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kopec JA, Yothers G, Ganz PA, Land SR, Cecchini RS, Wieand HS, Lembersky BC, Wolmark N (2007) Quality of life in operable colon cancer patients receiving oral compared with intravenous chemotherapy: results from National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project Trial C-06. J Clin Oncol 25: 424–430, [published erratum appears in: J Clin Oncol 2007; 25: 5540–5541] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miwa M, Ura M, Nishida M, Sawada N, Ishikawa T, Mori K, Shimma N, Umeda I, Ishitsuka H (1998) Design of a novel oral fluoropyrimidine carbamate, capecitabine, which generates 5-fluorouracil selectively in tumors by enzymes concentrated in human liver and cancer tissue. Eur J Cancer 34: 1274–1281 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nunally JC, Berstein IH (1994) Psychometric Theory. 3rd edn. New York: McGrawHill [Google Scholar]

- Osoba D, Rodrigues G, Myles J, Zee B, Pater J (1998) Interpreting the significance of changes in health-related quality-of-life scores. J Clin Oncol 16: 139–144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parkin DM, Bray F, Ferlay J, Pisani P (2005) Global cancer statistics, 2002. CA Cancer J Clin 55: 74–108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Payne SA (1992) A study of quality of life in cancer patients receiving palliative chemotherapy. Soc Sci Med 35: 1505–1509 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelusi J (2006) Capecitabine versus 5-FU in metastatic colorectal cancer: considerations for treatment decision-making. Commun Oncol 3: 19–27 [Google Scholar]

- Perrocheau G, Bennouna J, Ducreux M, Hebbar M, Ychou M, Lledo G, Conroy T, Dominguez S, Florentin V, Douillard JY (2009) Cost-minimization analysis of XELOX versus FOLFOX-6 as first-line treatment of metastatic colorectal cancer in France. American Society of Clinical Oncology, Gastrointestinal cancers symposium: San Francisco Abstract, #10411, p 290 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Porschen R, Arkenau H-T, Kubicka S, Greil R, Seufferlein T, Freier W, Kretzschmar A, Graeven U, Grothey A, Hinke A, Schmiegel W, Schmoll H-J (2007) Capecitabine plus oxaliplatin compared with fluorouracil and leucovorin plus oxaliplatin: a randomized comparison in metastatic colorectal cancer – a final report of the AIO Colorectal Study Group. J Clin Oncol 25: 4217–4223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reigner B, Blesch K, Weidekamm E (2001) Clinical pharmacokinetics of capecitabine. Clin Pharmacokinet 40: 85–104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothenberg ML, Cox JV, Butts C, Navarro M, Bang YJ, Goel R, Gollins S, Siu LL, Laguerre S, Cunningham D (2008) Capecitabine plus oxaliplatin (XELOX) versus 5-fluorouracil/folinic acid plus oxaliplatin (FOLFOX-4) as second-line therapy in metastatic colorectal cancer: a randomized phase III noninferiority study. Ann Oncol 19: 1720–1726 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rotonda C, Conroy T, Mercier M, Bonnetain F, Uwer L, Miny J, Montcuquet P, Léonard I, Adenis A, Breysacher G, Guillemin F (2008) Validation of the French version of the colorectal-specific quality-of-life questionnaires EORTC QLQ-CR38 and FACT-C. Qual Life Res 17: 437–445 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schüller J, Cassidy J, Dumont E, Roos B, Durston S, Banken L, Utoh M, Mori K, Weidekamm E, Reigner B (2000) Preferential activation of capecitabine in tumor following oral administration to colorectal cancer patients. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 45: 291–297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Therasse P, Arbuck SG, Eisenhauer EA, Wanders J, Kaplan RS, Rubinstein L, Verweij J, Van Glabbeke M, van Oosterom AT, Christian MC, Gwyther SG (2000) New guidelines to evaluate the response to treatment in solid tumors. European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer, National Cancer Institute of the United States, National Cancer Institute of Canada. J Natl Cancer Inst. 92: 205–216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Twelves C, Gollins S, Grieve R, Samuel L (2006) A randomised cross-over trial comparing patient preference for oral capecitabine and 5-fluorouracil/leucovorin regimens in patients with advanced colorectal cancer. Ann Oncol 17: 239–245, Comment in: Ann Oncol 2006; 17: 185–187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Cutsem E, Twelves C, Cassidy J, Allman D, Bajetta E, Boyer M, Bugat R, Findlay M, Frings S, Jahn M, Mckendrick J, Osterwalder B, Perez-Manga G, Rosso R, Rougier P, Schmiegel WH, Seitz J-F, Thompson P, Vieitez JM, Harper P, Weitzel C (2001) Oral capecitabine compared with intravenous fluorouracil plus leucovorin in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer: results of a large phase III study. J Clin Oncol 19: 4097–4106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webster K, Cella D, Yost K (2003) The Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy (FACIT) measurement system: properties, applications, and interpretation. Health Qual Life Outcomes 1: 79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yost K, Hahn E, Cella D (2005a) A new measure of chemotherapy convenience and satisfaction. J Clinic Oncol 23: 538s [Google Scholar]

- Yost KJ, Cella D, Chawla A, Holmgren E, Eton DT, Ayanian JZ, West DW (2005b) Minimally important differences were estimated for the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Colorectal (FACT-C) instrument using a combination of distribution- and anchor-based approaches. J Clin Epidemiol 58: 1241–1251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]