Abstract

The Adolescent Transitions Program (ATP) is a family-focused multilevel prevention program designed for delivery within public middle schools to target parenting factors related to the development of behavior problems in early adolescence. The current study examines the effects of the ATP on the development of youth depressive symptoms across early adolescence in a sample of 106 high-risk youths. Youths were recruited in 6th grade, and selected as high risk based on teacher and parent reports of behavioral or emotional problems. Depression symptoms were based on youth and mother reports in 7th, 8th, and 9th grades. Receipt of the family-centered intervention inhibited growth in depressive symptoms in high-risk youths over the 3 yearly assessments compared with symptoms in high-risk youths in the control group. Results support the notion that parental engagement in a program designed to improve parent management practices and parent–adolescent relationships can result in collateral benefits to the youths' depressive symptoms at a critical transition period of social and emotional development.

Keywords: depression, family intervention, prevention, motivational interviewing, early adolescence

A substantial number of youths experience significant problems with depression and emotional distress. Indeed, by the age of 18, nearly one in five teens will have experienced a major depressive episode, with estimates as high as one in four found in the literature (Kessler, Avenevoli, & Merikangas, 2001). The transition into adolescence marks a time of heightened risk, particularly for girls, who are nearly twice as likely as boys to experience clinically significant depressive symptoms following the pubertal transition (e.g., Hankin et al., 1998). Further, adolescents who experience major depressive episodes have serious negative long-term consequences in a variety of domains of adult functioning (e.g., Fombonne, Wostear, Cooper, Harrington, & Rutter, 2001; Lewinsohn, Rohde, Seeley, Klein, & Gotlib, 2003). In light of the prevalence and serious adverse consequences of depression for current and future functioning, improved understanding of potential intervention strategies for depression in youths is critical.

In the recent years, there have been a number of studies on the effectiveness of psychosocial interventions for depressed children and adolescents, the vast majority of which focus on treating youths individually or in groups (see Kaslow, McClure, & Connell, 2002). Two such intervention approaches, cognitive–behavioral therapy (CBT) and interpersonal psychotherapy for adolescents (IPT–A; Mufson, Moreau, Weissman, & Klerman, 1993) have received empirical support and are associated with moderate-to-large treatment effects at posttreatment and over short-term follow-up periods (e.g., Lewinsohn & Clarke, 1999; Michael & Crowley, 2002; Reinecke, Ryan, & Dubois, 1998). However, about 40% of children and adolescents do not respond to these child-focused interventions, and a substantial number of treated youths experience relapse within 1 year of treatment (e.g., Birmaher et al., 2000). As most studies have not included long-term follow-up (for example, only one study to date has included follow-up beyond 2 years), the longer-term benefits of these interventions remain to be documented.

There are also few studies that report outcome data reflecting broader domains of children's functioning beyond depressive symptoms, most notably family functioning (see Hammen, Rudolph, Weisz, Rao, & Burge, 1999). The lack of attention to family functioning in studies of individual interventions for depressed youths is important because depression in youths may be more closely linked to the immediate family context than is depression in adults (for a review, see Stark, Swearer, Kurowski, Sommer, & Bowen, 1996). Indeed, Hammen and colleagues (1999) suggested that one of the central developmental features of depression in youths is that children's depressive symptoms are intimately embedded within the family context. This perspective is consistent with an interactional model of depression (see Joiner & Coyne, 1999), which suggests that depressive symptoms arise and are maintained, at least in part, by problematic relational processes within both family and peer systems. Indeed, there is a large literature relating aspects of family functioning to the development of depression in youths, including high levels of stress and conflict, low levels of warmth and support, family interaction patterns that reinforce depressive behavior, and parental psychopathology, among others (see Sheeber, Hops, & Davis, 2001).

There is evidence supporting the need to focus on the family environments when providing treatment for young adolescents as well. For instance, Brent and colleagues (1998) found that the efficacy of a child-focused CBT intervention was drastically reduced in the presence of significant maternal depressive symptoms relative to either a systemic behavior family therapy (SBFT) or a control condition. Further, parent–child conflict predicted lower recovery rates, more chronic depressive symptoms, and a greater likelihood of relapse over a 2-year follow-up period across the three treatment conditions (Birmaher et al., 2000). Similarly, Asarnow, Goldstein, Tompson, and Guthrie (1993) reported that high levels of parental criticism and emotional overinvolvement predicted persistent mood disorder in youths 1 year after hospitalization for depressive disorders. Lewinsohn and Clarke (1984) likewise reported that teen perceptions of low levels of family support predicted poorer treatment outcomes for depressed teens receiving CBT. Taken together, the limited body of available evidence suggests that problems in family functioning predict poor treatment response and greater likelihood of relapse for depressed children and adolescents in youth-focused treatments.

Despite a wealth of empirical research linking depression in youths to disturbances in a variety of aspects of family functioning, as well as evidence relating problematic family functioning to poorer treatment outcome from youth-focused interventions, family-focused intervention approaches have been decidedly underrepresented in the treatment literature. Only one study has examined the effectiveness of family therapy for depression in adolescents, comparing the effects of SBFT, CBT, and a nondirective supportive control condition (Brent et al., 1997). Although adolescents in the CBT showed the fastest symptom improvement and highest rates of remission at post-treatment, outcomes for CBT and SBFT did not differ by the end of a 2-year follow-up period. Of particular note, parents in the SBFT group reported significant decreases in perceptions of treatment credibility over the course of treatment, relative to parents in either of the other conditions, which the authors attributed to the possibility that parents found the focus on problematic family functioning in the SBFT condition to be aversive (Stein et al., 2001). This finding highlights the critical importance of motivating parents to engage and comply with family-based treatments.

Two studies have examined the added value of including a parallel parent-training component in addition to individual CBT for depressed adolescents. Lewinsohn and colleagues (Lewinsohn, Clarke, Hops, & Andrews, 1990; Clarke, Rohde, Lewinsohn, Hops, & Seeley, 1999) examined the incremental value of adding a parallel parent-training intervention in addition to the teen-focused coping with depression course. However, low rates of parent engagement and high rates of parental attrition were noted across parent sessions. Similarly, poor parent engagement was noted in a study of a universal school-based prevention program for adolescent depression. Schochet and colleagues (2001) offered a 3-session parent-training adjunct to an 11-session teen-focused prevention program. Only 10% of families took part in all 3 sessions. Perhaps not surprisingly, the addition of the poorly attended parent-training sessions in these studies did not lead to incremental improvements in treatment outcome over the child-focused treatment components alone.

Preliminary evidence from two small-scale investigations of family-oriented treatments for depressed youths has been described in the literature, with promising preliminary results (Asarnow, Scott, & Mintz, 2002; Diamond, Reis, Diamond, Siqueland, & Isaacs, 2002). However, in light of (a) the large body of evidence documenting the association between depressive symptoms in youths and aspects of family functioning, (b) research demonstrating that impaired family functioning is associated with poorer outcomes from individual psychotherapy with depressed youths, and (c) poor parental engagement with family-treatment components in past research, the field stands to benefit substantially from the development of alternative treatments that might be implemented in novel ways to promote increased parent and family engagement in treatment.

In the current article, we focus on depression outcomes from the ATP (see Dishion & Kavanagh, 2003), a contextually sensitive family-treatment model designed to promote heightened treatment engagement for family members. This intervention model was originally formulated to target family processes related to the risk for adolescent conduct problems and substance use development. A central component of the ATP is the family checkup (FCU; Dishion, Kavanagh, Schneiger, Nelson, & Kaufman, 2002; Dishion & Kavanagh, 2003), which is based on motivational interviewing techniques designed to enhance family engagement and trigger the behavior change process (Miller & Rollnick, 2002). In several studies with families of children entering adolescence, the ATP intervention approach has been found to increase parental engagement in treatment, to improve parenting skills, and ultimately to reduce conduct problems and substance use across adolescence (Connell, Dishion, Yasui, & Kavanagh, 2007; Dishion & Kavanagh, 2003; Dishion et al., 2002).

Although the ATP intervention was originally formulated to target adolescent problem behaviors by improving parenting practices, many family risk processes are common across depression and conduct problems across adolescence. In common with the families of depressed youths, families of youths with behavior problems in adolescence are marked by high levels of stress and conflict, low levels of parental warmth and support, and high levels of coercive and negative involvement with youths (for a review, see Dishion & Patterson, 2006). In light of the overlapping familial risk factors for adolescent depression and conduct problems, and the results of past studies in which the ATP has been found to improve parenting skills and parent–youth relationships, we hypothesized that receipt of the family-centered ATP intervention would result in reductions in depressed mood among adolescents. Similar results have recently been reported from two other prevention programs, in which family-focused preventive interventions originally designed to prevent conduct problems and substance use were found to have beneficial effects on youth depression (Mason et al., 2007; Trudeau, Spoth, Randall, & Azevedo, 2007). We expected that the motivational component may have particular benefits for the families of depressed adolescents, who have been shown to be difficult to engage in past treatment studies for depression. In the current study, we examine the effect of the ATP intervention on depressive symptoms in youths at high risk for emotional and behavior problems across 3 years.

Method

Participants

The current study uses a selected subsample of youths and families from a larger longitudinal prevention trial. The larger sample includes 998 adolescents and their families, recruited in sixth grade from three middle schools within an ethnically diverse metropolitan community in the Northwest region of the United States. All sixth-grade students were approached for participation, and 90% of these families consented to participate in the study. For details of the larger sample, see Dishion and Kavanagh (2003). Youths were randomly assigned in the sixth grade at the individual level to either control classrooms (498 youths) or intervention classrooms (500 youths) in the seventh grade. The control condition was “school as usual,” so that parents and youths assigned to control classrooms were not offered any of the intervention components of the ATP. Students and the families in the intervention condition were engaged in the family-centered intervention in the seventh and eighth grades. Students who left the targeted schools were offered services if they remained in the county. A multiple gating approach to risk assessment was used, with high-risk designations being based initially on teacher report, using a 16-item screening instrument (Dishion & Kavanagh, 2003). Problem behaviors included aggression, moodiness, oppositionality, peer relationship problems, and school problems. Youths with scores of 3 or higher or whom teachers suspected of substance use were designated high risk.

The subsample used in the current article consists of all youths who were designated as high risk. The major reason for this selection is that only youths deemed as high risk completed more comprehensive assessments, including the measurement of depression symptoms. Details regarding the allocation of participants in this study are shown in Figure 1. The high-risk subsample consisted of 106 youths and their families, including 46 male adolescents (43.4%) and 60 female adolescents (56.6%). By youth self-report, there were 34 European Americans (32.1%), 47 African Americans (44.3%), 8 Latinos (7.6%), and 17 (16.0%) youths of other ethnicities. There were 52 youths assigned to the control condition (49.1%) and 54 youths assigned to the intervention condition (50.9%). A variety of family living circumstances were represented in the high-risk sample, with 31.7% of youths residing with both biological parents, 27.7% in a single-mother-headed household, and 20.8% in a blended-family household. In line with the high-risk nature of these families, there were substantial missing depression data across the three yearly assessments, with 47.2% (n = 50) of youths missing at least one yearly report of depressive symptoms. There were no differences in demographic variables across the intervention and control groups, and there were no differences in the number of waves of missing depression data by participants related to any of the covariates used in the current analyses.

Figure 1.

Flow of participants through study. FCU = family checkup.

Assessment Procedures

Assessments were conducted each year, beginning in the spring of sixth grade. During the spring of sixth, seventh, and eighth grades, teachers completed a questionnaire assessing youth engagement in risky behavior for all youths in their classroom, and all youths in the full sample completed several questionnaires, including self-reported antisocial behavior. These assessments were conducted primarily in the schools. High-risk youths were selected on the basis of teacher reports on the risk inventory, and these high-risk youths and their families were contacted and asked to complete additional assessment measures, including the Child Depression Inventory (CDI), and the maternal Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL). The assessments of high-risk youths and their parents or legal guardians took place in the fall of seventh, eighth, and ninth grades. If students moved out of their original schools, we followed them to their new locations. Youths were paid $20 for completing each assessment. The FCU intervention and linked services were initiated following the Fall assessment in seventh grade, so the Spring sixth-grade and Fall seventh-grade assessments provided baseline data on child functioning, prior to the receipt of intervention. All study procedures, including assessment and intervention protocols, were approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Oregon, and parental consent and youth assent were collected prior to family participation in the study.

Measures

CDI

The CDI (Kovacs, 1992) is a widely used self-report measure of depressive symptoms in youths. The CDI includes 27 items, scored on a 3-point scale. In the current sample, good internal consistency was found (alpha reliability ranged from .80 to .87 across years). Possible scores range from 0 to 54 (seventh grade: M = 9.82, SD = 7.05; eighth grade: M = 12.01, SD = 5.99; ninth grade: M = 11.46, SD = 5.96). Scores over 12 reflect clinically significant symptoms of depression in high-risk samples (Kovacs, 1992). In seventh grade, 31.6% of the youths reported CDI scores in the clinical range, while 45.2% were in the clinical range in eighth grade, and 35.8% were in the clinical range in ninth grade.

Child-reported problem behavior

Youth reports of engagement in problem behavior were measured averaging across six items from the Fall assessment, using an instrument developed and reported by colleagues at the Oregon Research Institute (Metzler, Biglan, Rusby, & Sprague, 2001). Items assessed the number of times in the past month teens reported having engaged in the following behaviors: (a) lying to parents, (b) skipping school, (c) staying out all night without permission, (d) stealing, (e) panhandling, and (f) carrying a weapon. Responses were given on a 6-point scale, ranging from 1 (never) to 6 (more than 20 times). Scores on this measure have been found to predict the number of future arrests (Connell et al., 2007) and to relate to theoretically derived covariates (Connell & Frye, 2006; Gardner, Dishion, & Connell, 2008). Good internal reliability was found for this scale across assessments (alpha reliability ranged from .63 to .74 across years). Possible scores range from 1 to 6 (sixth grade: M = 1.46, SD = 0.60; seventh grade: M = 1.41, SD = 0.55; eighth grade: M = 1.40, SD = 0.52).

Maternal-reported internalizing and externalizing problems

Maternal reports of youth internalizing and externalizing symptoms were measured with the CBCL (Achenbach, 1991). The CBCL is a widely used measure with well-validated norms that contains 112 items, rated on the extent to which each item accurately describes the child's behavior in the past 6 months, including 0 (rarely/never), 1 (somewhat or sometimes true), and 2 (very or often true). The Internalizing scale reflects depressed, anxious, withdrawn, and somatic symptoms, while the Externalizing scale reflects aggressive, disruptive, or delinquent behaviors. Sample means for Internalizing T scores were as follows: seventh grade, M = 51.52, SD = 10.85; eighth grade, M = 51.78, SD = 10.82; ninth grade, M = 51.45, SD = 12.38. Sample means for Externalizing T scores were as follows: seventh grade, M = 57.00, SD = 10.43; eighth grade, M = 55.39, SD = 11.60; ninth grade, M = 52.85, SD = 10.80. In the current sample, high internal consistency was found (alpha reliability ranged from .89 to .92 for Internalizing scores and from .90 to .93 for Externalizing scores, across years).

Child gender

Child gender was coded 0 for male adolescents and 1 for female adolescents.

Child ethnicity

For ease of data analysis, child ethnicity was coded as a two-category variable (0 = Caucasian and 1 = ethnic minority).

Intervention status

Random assignment to the control condition was coded 0, and random assignment to the intervention condition was coded 1.

Teacher report of school risk behavior

Teacher reports of youth engagement in risk behaviors were collected in sixth and seventh grades with 16 items. Items reflected the frequency with which youths engaged in a variety of problem behaviors on a 5-point scale ranging from 1 (never/almost never) to 5 (always/almost always). Items included aggression, oppositionality, peer relationship problems, disliking school, and moodiness. The sample M = 1.85 (SD = 0.85). High internal consistency reliability was found for this scale (alpha reliability = .95). This variable was mean-centered for use in analyses.

Intervention Protocol

The ATP is an adaptive multilevel intervention for delivery in the public school environment (Dishion & Kavanagh, 2003). The core feature of an adaptive intervention framework is that specific intervention targets and dose are determined individually based on decision rules in order to adapt treatment to the needs of individual families (Collins, Murphy, & Bierman, 2004). The ATP model comprehensively links universal, selected, and indicated intervention services in a way that titrates the intervention intensity to the needs and motivation of the family, actively promoting self-selection into the most appropriate intervention services based on systematic assessments of parent and child functioning.

The first level of the program, a universal intervention, established a family resource center (FRC) in each of the three participating public middle schools. The parent-centered services of the FRC were available for the entire intervention group. These included brief consultations with parents, telephone consultations, feedback to parents on their child's behavior at school, and access to videotapes and books. In addition, the FRC interventionists conducted six in-class lessons referred to as the Success, Health, and Peace (SHAPe) Curriculum to students. The intervention was modeled after the Life Skills Training program described by Botvin (Botvin, Baker, Dusenbury, Tortu, & Botvin, 1990), but reduced in scope (6 in SHAPe vs. 16 in Life Skills Training). The focuses of the six sessions were the following: (a) school success, (b) health decisions, (c) building positive peer groups, (d) the cycle of respect, (e) coping with stress and anger, and (f) solving problems peacefully. Included in this intervention were brief parent–student activities designed to motivate family management. The universal intervention was designed to support positive parenting practices and to engage parents of high-risk youths for the selected intervention.

The selected intervention is the FCU, a brief, three-session intervention based on motivational interviewing and modeled after the drinker's checkup (Miller & Rollnick, 2002). While all families could receive the FCU, families of high-risk youths, determined by teacher ratings, were specifically offered the FCU in seventh and eighth grades. The three sessions consist of an initial interview, where the therapist explores parent concerns and stage of change and motivates involvement in a family assessment. The second session is primarily assessment, where the family engages in a variety of assessment tasks, including in-home videotaped assessment of a parent–child interaction. The third session involves a feedback session, where the therapist systematically summarizes the results of the assessment by using motivational interviewing strategies. An essential objective of the feedback session is to explore potential intervention services that support family management practices.

An outcome of the FCU is a collaborative decision between the parent and interventionist on the indicated services most appropriate for the family. As such, families completing the FCU were potentially offered the third level of the intervention (depending on the results of the assessment), involving intervention strategies adapted from a variety of empirically supported parenting interventions (e.g., Dishion & Andrews, 1995; Forgatch & DeGarmo, 1999; Henggeler, Schoenwald, Borduin, Rowland, & Cunningham, 1998; Patterson, Reid, Jones, & Conger, 1975). The core ATP parenting curriculum involved 12 sessions, focused on improving parental positive engagement with youths, consistent use of positive reinforcement, appropriate limit setting and discipline strategies, improved family communication and problem solving, and reduced family conflict. Additional details regarding intervention components are presented in Dishion and Kavanagh (2003).

All ATP services were delivered by interventionists, who were trained with a combination of strategies, including didactic instruction, role playing, and videotaped supervision throughout the 2 years of intervention activity. Interventionists followed a written manual and received videotaped supervision in training, which was a prepublication version of an intervention book by Dishion and Kavanagh (2003). Two of the three interventionists had bachelor of science degrees and the third had a master's degree in counseling. All were women and their ethnicities closely matched those of the participating families.

Analysis Plan

Separate analyses were examined for youth-reported symptoms on the CDI and mother reports of youth symptoms on the CBCL. Although internalizing symptoms are more inclusive than depressive symptoms, they served as a proxy for parent-reported depressive symptoms in the current analyses, in order to provide analyses parallel to those for youth-reported symptoms. The central hypotheses regarding intervention effects were tested with two latent growth models (LGMs) for each reporter and followed an intent-to-treat (ITT) framework. All analyses were conducted with Mplus 4.1 (Muthén & Muthén, 2006) and used full information maximum likelihood estimation (FIML), which provides a method for accommodating missing data by estimating each parameter with all available data for that parameter. We first examined whether results for intervention effects differed when only youths with complete data were included versus when employing FIML procedures to account for missing data. No differences in results were found, and so we report only results using FIML procedures.

Primary hypothesis tests used LGM analyses to examine the effect of treatment on the rate of change in depressive symptoms by using LGMs for youth and mother reports, with the linear slope for depressive symptoms regressed on a dummy variable reflecting random assignment to treatment as well as with both intercept and slope for depressive symptoms regressed on both ethnicity and gender. Because the intervention was designed to target the risk for conduct problems, rather than depression, we included youth-reported or mother-reported conduct problems at each assessment wave as time-varying covariates in the model (i.e., youth reports served as covariates in the youth-report model, and mother reports as covariates in the mother-report model). The goal of the inclusion of these time-varying covariates was to examine whether the intervention effect on depression was specific to depression or due to co-occurring problem behaviors which tend to co-occur with depression. The latter finding would indicate that the putative treatment effect on depression may be spurious. Monte Carlo power simulations indicated that the LGM analyses have 80% power to detect at least small-to-moderate effects (Cohen's d ≥ 0.41).

While the primary hypothesis tests were conducted with an ITT approach, follow-up analyses employed complier average causal effect analyses (CACE; Imbens & Rubin, 1997; Jo, 2002; Little & Yau, 1998) in order to examine the possibility that the intervention effect was largely driven by familial participation in the selected and indicated levels of intervention (that is, the receipt of the FCU and additional services, as needed). Complete statistical details regarding the logic of CACE modeling are presented elsewhere (e.g., Jo, 2002), as are more complete descriptions of the use of the CACE framework to examine the impact of adaptive prevention designs such as the ATP (Connell, Dishion, Yasui, & Kavanagh, 2007). Briefly, typical ITT analyses may underestimate the true effect of the active levels of intervention in the context of a multilevel prevention trial, because some individuals receive only the low-intensity universal prevention, while others select to receive the more intense FCU intervention and linked services. CACE analysis provides a robust means of focusing on treatment outcomes of those families who elected to receive the selected/indicated levels of the intervention, here defined as compliers. The goal of these CACE analyses is to employ a mixture modeling framework to identify the optimal comparison group from the control condition for observed intervention compliers in the intervention condition (in this case, defined as receiving the FCU and linked services as needed). This matching is accomplished by employing the Estimation Maximization algorithm, and treating compliance status in the sample as a missing variable, which is known in the intervention condition, and estimated in the control condition, on the basis of covariates (i.e., gender, ethnicity, and co-occurring behavior problems), and outcome trajectory (i.e., estimated baseline depressive symptoms), in the face of modeling restrictions described by Jo (2002), in order to yield unbiased CACE estimates. In this way, the application of CACE modeling provides the ability to examine whether compliance with the active levels of intervention drives intervention effects in the multilevel intervention framework, when the original study was not designed to tease apart effects of different intervention components (for a more complete description of the statistical methodology, Connell et al., 2007; Jo, 2002). These follow-up CACE analyses also controlled for time-varying externalizing problems. Monte Carlo power simulations indicated that the CACE analyses have 80% power to detect large effects (Cohen's d ≥ 0.85), which are in line with prior CACE analyses with this sample (Connell et al., 2007).

Results

Treatment Engagement

Within the intervention group, most parents (88.9%) of the high-risk youths received services from the family resource staff, including brief consultations, queries about student behavior, and accessing parenting resources/ information. Further, 60% of these families completed the FCU and linked intervention services through the family resource room. Contrary to expectations, few parents selected to receive the full 12-session curriculum, choosing instead periodic FCU meetings and brief consultations around specific parenting issues. Of all FCUs completed, 46% were completed following the seventh-grade family assessment, 53% were completed following the eighth-grade family assessment, and 1% was completed following the ninth-grade family assessment. High-risk families in the intervention condition received an average of 7.89 hr of services from family resource staff during these years, with a range of 0 to 45.8 hr.

Preliminary Analyses

Correlations among the study variables are presented in Table 1. Preliminary analyses examined differences in the mean levels of the CDI and maternal CBCL scores across treatment and control groups at each grade. For CDI scores, only the ninth-grade scores differed significantly across groups, F(1, 80) = 5.70, p < .05, with youths in the treatment group reporting significantly lower CDI scores (M = 9.90, SD = 6.35) than did youths in the control group (M = 12.98, SD = 6.35). Chi-square analyses examined differences in the percentage of youths in the clinical range on the CDI at each year. Significant differences in the number of youths in the clinical range across treatment (N = 10) and control groups (N = 19) were found only in ninth grade, χ2(1) = 4.65, p < .05 (odds ratio = 2.70). For maternal CBCL scores, seventh-grade scores differed across intervention and control groups, F(1, 72) = 4.41, p < .05, with mothers in the intervention group reporting higher levels of internalizing problems in youths (M = 53.98, SD = 10.21) than did mothers in the control group (M = 48.64, SD = 11.49). No other significant differences in the mean level of internalizing problems were found. No significant differences were found in the percent of youths in the clinical range on the Internalizing scale at any year.

Table 1.

Correlations

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Child Depression Inventory (Fall seventh grade) | — | |||||||||||||

| 2. Child Depression Inventory (Fall eighth grade) | .49* | — | ||||||||||||

| 3. Child Depression Inventory (Fall ninth grade) | .35* | .31* | — | |||||||||||

| 4. Treatment | −.03 | −.08 | −.26* | — | ||||||||||

| 5. Gender | .16 | .07 | .17 | .04 | — | |||||||||

| 6. Ethnicity | −.01 | −.04 | .08 | .02 | .15* | — | ||||||||

| 7. Antisocial (Spring sixth grade) | .16 | .23* | .06 | .05 | .01 | .07 | — | |||||||

| 8. Antisocial (Spring seventh grade) | .22* | .21* | .10 | .04 | .07 | .06 | .38* | — | ||||||

| 9. Antisocial (Spring eighth grade) | .14 | .16 | .03 | .16 | −.05 | −.04 | .32* | .44* | — | |||||

| 10. Internalizing (Fall seventh grade) | .34* | .18 | .17 | .21* | .10 | −.08 | .16 | .09 | .06 | — | ||||

| 11. Internalizing (Fall eighth grade) | .08 | −.01 | .01 | .12 | .15 | −.12 | .12 | −.12 | .08 | .47* | — | |||

| 12. Internalizing (Fall ninth grade) | .27 | .03 | .18 | −.07 | .23* | −.19 | .04 | −.20 | −.01 | .53* | .61* | — | ||

| 13. Externalizing (Fall seventh grade) | .30* | .20* | −.04 | .18* | .16 | −.10 | .15 | .18* | .09 | .72* | .40* | .28* | — | |

| 14. Externalizing (Fall eighth grade) | .04 | .02 | −.05 | .25* | .10 | −.23* | .14 | .07 | .26* | .37* | .67* | .33* | .56* | — |

| 15. Externalizing (Fall ninth grade) | .13 | −.08 | −.04 | .19 | .05 | −.13 | −.01 | −.15 | .18 | .46* | .45* | .59* | .54* | .63* |

p < .05.

Preliminary analyses also examined the patterns of co-occurring symptoms of depression and conduct problems in order to better describe the clinical presentations of participants. Self-reported conduct problems were coded as clinically significant if youths were 1 SD or more above the sample mean at a given assessment year. By youth report, 20% of youths in the clinical range on the CDI were also 1 SD or more above the mean for antisocial behavior in seventh grade, 15.8% in eighth grade, and 10.3% in ninth grade. For maternal reports, clinical cutoff scores on the Internalizing and Externalizing scales were used to examine patterns of co-occurrence. By mothers' reports, 76.2% of youths with clinically significant internalizing problems also showed clinically significant levels of externalizing problems in seventh grade, 86.7% also showed clinically significant externalizing problems in eighth grade, and 69.2% also showed clinical levels of externalizing problems in ninth grade.

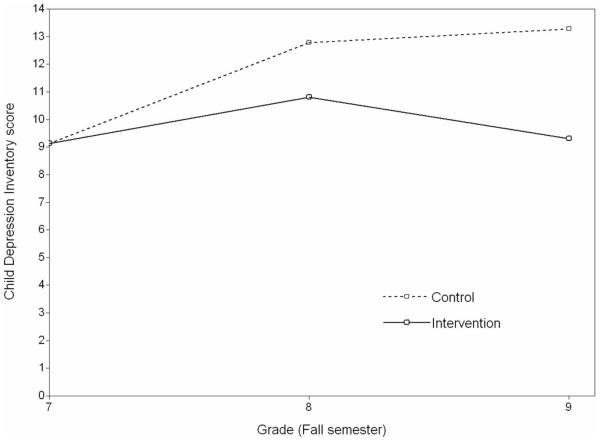

LGM for Youth-Reported Symptoms

In a preliminary analysis, the residual variance in the slope parameter was nonsignificantly negative, and so this parameter was fixed to zero in the final model. The final model including problem behavior as a time-varying covariate provided good fit to the data, χ2(11) = 13.58, p = .26 (comparative fit index [CFI] = .95, root-mean-square error of approximation [RMSEA] = .05). As shown in Table 2, intervention predicted decreased growth in depressive symptoms from seventh to ninth grade, controlling for co-occurring problem behaviors. The intervention produced a medium-sized difference in depression symptoms at ninth grade (Cohen's d = 0.56; Cohen, 1988). Problem behavior was significantly related to depressive symptoms at seventh grade (estimate = 2.24, SE = 0.92, p < .05) but not in eighth grade (estimate = 1.26, SE = 0.88) or ninth grade (estimate = 0.73, SE = 1.28). Additionally, female gender and Caucasian ethnicity predicted elevated symptoms in seventh grade. Results of this analysis are shown graphically in Figure 2.

Table 2.

Latent Growth Model Results for Youth-Reported and Mother-Reported Symptoms

| Variable | Intercept |

Slope |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate | SE | Estimate | SE | |

| Youth self-report model | ||||

| Intervention | Fixed at 0 | −1.99 | 0.61* | |

| Gender | 2.94 | 1.32* | −0.44 | 0.87 |

| Ethnicity | −2.87 | 1.38* | 1.60 | 0.89 |

| Parameter intercept | 5.90 | 1.90* | 1.59 | 1.36 |

| Parameter residual variation | 11.48 | 3.06* | Fixed at 0 | |

| Maternal report models | ||||

| Intervention | Fixed at 0 | −2.12 | 0.90* | |

| Gender | 0.44 | 1.67 | 2.48 | 1.05* |

| Ethnicity | −1.32 | 1.80 | −0.87 | 1.11 |

| Parameter intercept | 9.67 | 4.30* | 4.29 | 3.03 |

| Parameter residual variation | 31.98 | 7.23* | Fixed at 0 | |

p < .05.

Figure 2.

Latent growth model results for Child Depression Inventory.

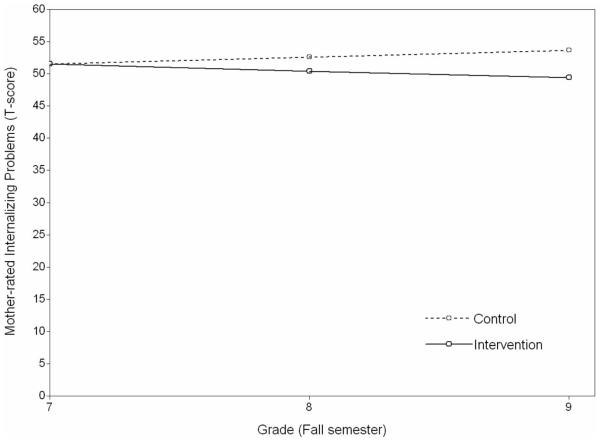

LGM for Maternal Reports of Youth Symptoms

In a preliminary analysis, the residual variance in the slope parameter was nonsignificantly negative, and so this parameter was fixed to zero in the final model. The final model including problem behavior as a time-varying covariate provided good fit to the data, χ2(11) = 13.58, p = .26 (CFI = .95, RMSEA = .05). As shown in the bottom of Table 2, the effect of the intervention on the rate of change in depressive symptoms was significant, controlling for co-occurring externalizing problems. The intervention produced a small-to-medium-sized difference in depression symptoms at ninth grade (Cohen's d = 0.42; Cohen, 1988). Externalizing problems were significantly related to internalizing symptoms at seventh grade (estimate = 0.75, SE = 0.06, p < .05), eighth grade (estimate = 0.69, SE = 0.05, p < .05), and ninth grade (estimate = 0.65, SE = 0.08, p < .05). Female gender predicted greater growth in internalizing symptoms.

CACE Model Results for Youth-Reported Symptoms

Because CACE analyses were examined as mixture models, traditional model fit indices are not available. One index of the quality of classification of the trajectory groups within the model is represented by entropy, a summary measure of the probability of membership in the most likely class for each individual. There are no specific guidelines for interpreting entropy, but possible values range from 0 to 1.0, and values closer to 1.0 represent better classification (Muthén & Muthén, 2006). In the current analyses, entropy was reasonable (entropy = .76). In line with the rate of observed compliance in the intervention group, 63.2% of the sample were classified as compliers. As shown in the top of Table 3 and in Figure 3, compliance was not related to gender or ethnicity. Of central concern, however, youths receiving intervention reported significantly less growth in self-reported depressive symptoms relative to youths in the control condition, a large treatment effect (Cohen's d = 1.35). Antisocial behavior was significantly related to depressive symptoms at eighth grade (estimate = 2.19, SE = 0.71, p < .05) but not in seventh grade (estimate = 1.26, SE = 0.95) or ninth grade (estimate = 1.07, SE = 0.96).

Table 3.

CACE Model Results For Youth-Reported and Maternal-Reported Symptoms

| Variable | Within-class variation in growth parameter |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Class membership (Complier vs. noncomplier) Logit (SE) |

Non-complier class |

Complier class |

|||

| Intercept Estimate (SE) |

Slope Estimate (SE) |

Intercept Estimate (SE) |

Slope Estimate (SE) |

||

| Youth-reported models | |||||

| Intervention status | Fixed at 0 | Fixed at 0 | Fixed at 0 | Fixed at 0 | −3.50 (0.75)* |

| Gender | 0.03 (0.59) | 0.11 (1.26) | −0.39 (0.82) | 4.52 (1.71)* | .52 (0.99) |

| Ethnicity | 0.43 (0.60) | −0.74 (1.55) | 0.10 (0.96) | −4.84 (1.90)* | 3.42 (0.99)* |

| Parameter intercept | −0.77 (0.58) | 5.03 (1.59)* | 1.05 (1.02) | 9.68 (2.54)* | 0.55 (1.52) |

| Parameter residual variance | 6.14 (3.14) | Fixed at 0 | 6.14 (3.14) | Fixed at 0 | |

| Mother-reported models | |||||

| Intervention status | Fixed at 0 | Fixed at 0 | Fixed at 0 | Fixed at 0 | −2.89 (1.08)* |

| Gender | 1.02 (0.59) | −2.90 (2.44) | 0.51 (2.44) | 1.51 (2.38) | 3.50 (1.12)* |

| Ethnicity | 0.05 (0.64) | −1.95 (3.12) | −0.42 (2.43) | −1.04 (1.22) | −1.05 (1.22) |

| Parameter intercept | −0.05 (0.57) | 9.30 (4.86)* | 5.07 (3.11) | 9.35 (4.56)* | 4.33 (3.07) |

| Parameter residual variance | 29.46 (7.78)* | Fixed at 0 | 29.46 (7.78)* | Fixed at 0 | |

p < .05.

Figure 3.

Latent growth model results for mother-rated Internalizing Problems.

CACE Model Results for Mother Reports of Youth Symptoms

In the CACE model results for maternal reports of youth internalizing symptoms, entropy was .65. In line with the rate of observed compliance, 65.3% of the sample were classified as compliers. As shown in Table 3, compliance was not related to gender or ethnicity. Of note, mothers of youths receiving intervention reported significantly less growth in youth internalizing symptoms than did the mothers of youths in the control group, a large treatment effect (Cohen's d = 1.07). Externalizing behavior was significantly related to internalizing symptoms at seventh grade (estimate = 0.75, SE = 0.07, p < .05), eighth grade (estimate = 0.69, SE = 0.06), and ninth grade (estimate = 0.64, SE = 0.09).

Discussion

The current analyses focus on changes in depressive symptoms in a cohort of high-risk youths recruited in a middle school setting and followed through early high school. Youths participated in a multilevel prevention program, with parent-focused interventions designed to motivate parents to improve parenting skills as the core intervention. In line with the high-risk nature of the sample, youths in the control group showed escalating depressive symptoms, by both youth and maternal report over the three yearly assessments. High-risk youths who received the multilevel intervention services of the ATP, however, reported no significant growth, indicating that the receipt of the intervention prevented escalations in symptoms that were shown by youths in the control group. Intervention effects on symptoms reported by youths and mothers were of similar magnitude.

The findings of reduced depressive symptoms are especially important in light of the sparse literature on family intervention effects on depression in adolescence. It is noteworthy that the current results are consistent with the sparse literature, including several other studies that have examined family-focused interventions for depression (e.g., Brent & colleagues, 1997; Diamond & colleagues, 2002), and with two recent reports of similar effects on depressive symptoms from family-focused prevention programs designed for substance use or conduct problems in teens (Mason et al., 2007; Trudeau et al., 2007). Taken together, the results of such studies support the notion that family intervention can lead to reductions in depressive symptoms in offspring. The current findings are particularly noteworthy because the active levels of treatment (the selected and indicated levels of intervention) were targeted exclusively at parents, with youths only taking part in the universal level of the ATP. Results of the CACE model analyses suggest that family engagement with these active levels of intervention drives the intervention effects, as the magnitude of the CACE estimate of the effects of intervention is substantially greater than that of the effects of the ITT analyses. As such, these results more clearly underscore that changes in the parenting system may lead to reductions in youth depression, independent of youth participation in treatment. Unlike past efforts at family interventions for depression, which encountered substantial difficulties with family engagement, the current intervention was explicitly grounded within a motivational interviewing framework and specifically attended to engaging parents with the intervention. In this high-risk sample, we found that the majority of families elected to receive the FCU assessment and additional intervention services as needed, which in turn led to improved depressive symptoms.

It is difficult to compare the success in engaging high-risk families with other intervention studies for several reasons. First, the process of engagement into the family-centered services occurred primarily in the public school system. School personnel were highly supportive of the family-centered services and therefore often assisted in the recruitment process. Second, we were able to engage families over an extended period of time, including seventh and eighth grade, and in some cases, over about 1.5 years. Most intervention studies attempting to recruit and engage families do so in a very narrow time window, whereas many high-risk families prefer and need to reach a point of motivation for engaging in intervention services. Finally, we engage families in very brief intervention services, in contrast to many studies that attempt to engage families into intervention programs, typically with a set number of sessions in manualized interventions. Of course, many families, following the FCU, do engage in additional intervention sessions, when the family assessment as well as their level of concern and motivation indicates it.

In addition to these three factors, we offer two other explanations for the high levels of engagement. We do believe it is important to match intervention and project staff with families with respect to ethnicity. It is very important, especially in a culturally diverse setting, to not have a service or program appear homogeneous for one cultural group. Note that we did not find any differences in engagement associated with ethnicity or minority group status. In fact, in two independent studies, one involving the FCU in early childhood and the second the current sample, we found that families most at risk on a variety of dimensions were the most likely to engage in the intervention services (Connell et al., 2007; Dishion, Shaw, Connell, Wilson, & Gardner, in press). Future research would benefit from better understanding the linkages between the kinds of services offered to caregivers and their willingness to participate.

Limitations

Although the results of the current study support the benefit of including family functioning as a target for interventions for depression in adolescence, several limitations are noteworthy. First, the youths in this intervention trial were likely to show signs of co-occurring problem affect and behavior, particularly by maternal report. Such symptom overlap is likely due to the method of selection. It is worth highlighting, however, that we found that the intervention effects on depression symptoms were significant when controlling for youths' co-occurring problem behavior in the current study. The fact that the intervention reduced escalations in depression suggests that the intervention model might be specifically enhanced to address both emotional and behavioral problems in early adolescence (Dishion & Stormshak, 2007).

Second, depression data were available only on the subset of high-risk youths in the current sample, which resulted in limited statistical power relative to the full sample of 999 youths. Concern is somewhat mitigated by the fact that these youths were selected because they were showing early signs of emotional and behavioral problems, and in prior work, we have shown that intervention effects are primarily driven by changes for these high-risk youths (see Connell, Dishion, & Deater-Deckard, 2006; Connell et al., 2007). Nevertheless, we recognize that a more powerful test of the effects of the ATP on depressive symptoms would have been possible if depression data had been collected on the full sample.

Third, depressive symptoms were assessed only during the course of the yearly assessments for high-risk youths. A more sensitive test of treatment effects would include pretest–posttest assessments timed around parent completion of FCU and linked services. It is possible that such a study design may lead to a larger intervention effect, as such effects may be largest immediately following intervention.

Fourth, the multilevel intervention framework provides some challenges for typical ITT analysis. ITT focuses on overall effect of the multilevel program on the development of depression symptoms. One challenge the current study was not designed to examine was whether the intervention effects are driven by the more intensive selected and indicated levels of the intervention, as we expect. Although we employed CACE analyses to examine the extent to which the receipt of the FCU and linked services lead to larger treatment effects, in a manner consistent with the notion that these levels were driving the intervention effects, CACE modeling is a statistically intensive enterprise and requires some inference to derive the compliance status of families in the control condition. Future studies of the ATP should be designed to permit more systematic examination of the effects of different intervention levels.

Future Directions

It is worth highlighting that the intervention approach used in this study was originally designed for families of youths with conduct problems or substance use. Although the intervention was not specifically designed to target the risk for depression, depression shares many risk factors with other problem behaviors that were targeted in the intervention, including improved family communication, family problem solving, and conflict reduction. We are currently testing a depression-focused adaptation of the ATP, to tailor the intervention more specifically to the needs of families with depressed adolescents. We hope to demonstrate even stronger intervention effects on depression in future research, including thorough examination of mediating pathways through which improved family functioning might lead to reductions in adolescent depression.

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by Grants DA07031 and DA13773 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse and Grant AA12702 at the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism to Thomas J. Dishion. Arin M. Connell was supported by a Klingenstein Third Generation Foundation Fellowship. We acknowledge the contribution of the Project Alliance staff, Portland Public Schools, and the participating youths and families.

Contributor Information

Arin M. Connell, Psychology Department, Case Western Reserve University

Thomas J. Dishion, Child and Family Center, University of Oregon.

References

- Achenbach TM. Manual for Child Behavior Checklist/4-18 and 1991 Profile. University of Vermont, Department of Psychiatry; Burlington, VT: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Asarnow J, Goldstein M, Tompson M, Guthrie D. One-year outcomes of depressive disorders in child psychiatric inpatients: Evaluation of the prognostic power of a brief measure of expressed emotion. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 1993;34:129–137. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1993.tb00975.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asarnow J, Scott C, Mintz J. A combined cognitive–behavioral family education intervention for depression in children: A treatment development study. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2002;26:221–229. [Google Scholar]

- Birmaher B, Brent D, Kolko D, Baugher M, Bridge J, Holder D, et al. Clinical outcome after short-term psychotherapy for adolescents with major depressive disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2000;57:29–36. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.57.1.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Botvin GJ, Baker E, Dusenbury L, Tortu S, Botvin EM. Preventing adolescent drug abuse through a multimodal cognitive–behavioral approach: Results of a three-year study. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1990;58:437–446. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.58.4.437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brent D, Holder D, Kolko D, Birmaher B, Baugher M, Roth C, et al. A clinical psychotherapy trial for adolescent depression comparing cognitive, family, and supportive therapy. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1997;54:877–885. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1997.01830210125017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brent D, Kolko D, Birmaher B, Baugher M, Bridge J, Roth C, Holder D. Predictors of treatment efficacy in a clinical trial of three psychosocial treatments for adolescent depression. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 1998;37:906–914. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199809000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke G, Rohde P, Lewinsohn P, Hops H, Seeley J. Cognitive–behavioral treatment of adolescent depression: Efficacy of acute group treatment and booster sessions. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 1999;38:272–279. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199903000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. Rev. ed. Academic Press; New York: 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Collins L, Murphy S, Bierman K. A conceptual framework for adaptive preventive interventions. Prevention Science. 2004;5:185–196. doi: 10.1023/b:prev.0000037641.26017.00. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connell A, Dishion T, Deater-Deckard K. Variable-and person-centered approaches to the analysis of early adolescent substance use: Linking peer, family, and intervention effects with developmental trajectories. Merrill–Palmer Quarterly. 2006;52:421–448. [Google Scholar]

- Connell A, Dishion T, Yasui M, Kavanagh K. An ecological approach to family intervention: Linking parent compliance with treatment to long-term prevention of adolescent problem behavior. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2007;75:568–579. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.75.4.568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connell A, Frye A. Growth mixture modeling in developmental psychology: Overview and demonstration of examining heterogeneity in developmental trajectories of antisocial behavior across adolescence. Infant & Child Development. 2006;15:609–621. [Google Scholar]

- Diamond G, Reis B, Diamond G, Siqueland L, Isaacs L. Attachment based family therapy for depressed adolescents: A treatment development study. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2002;41:1190–1196. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200210000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dishion T, Andrews D. Preventing escalation in problem behaviors with high-risk young adolescents: Immediate and 1-year outcomes. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1995;63:344–359. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.63.4.538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dishion T, Kavanagh K. Intervening in adolescent problem behavior: A family-centered approach. Guilford Press; New York: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Dishion T, Kavanagh K, Schneiger A, Nelson S, Kaufman N. Preventing early adolescent substance use: A family-centered strategy for the public middle school. Prevention Science. 2002;3:191–201. doi: 10.1023/a:1019994500301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, Patterson GR. The development and ecology of antisocial behavior in children and adolescents. In: Cicchetti D, Cohen DJ, editors. Developmental psychopathology: Vol. 3. Risk, disorder, and adaptation. Wiley; New York: 2006. pp. 503–541. [Google Scholar]

- Dishion T, Shaw D, Connell A, Wilson M, Gardner F. Early intervention effects on problem behavior development mediated through improved positive parenting. Child Development. in press. [Google Scholar]

- Dishion T, Stormshak E. Intervening in children's lives: An ecological family-centered approach to mental health care. APA; Washington, DC: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Fombonne E, Wostear G, Cooper V, Harrington R, Rutter M. The Maudsley long term follow-up of child and adolescent depression: I. Psychiatric outcomes in adulthood. British Journal of Psychiatry. 2001;179:210–217. doi: 10.1192/bjp.179.3.210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forgatch M, DeGarmo D. Parenting through change: An effective prevention program for single mothers. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1999;67:711–724. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.67.5.711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner T, Dishion T, Connell A. Adolescent self-regulation as resilience: Resistance to antisocial behavior within the deviant peer context. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2008;36:273–284. doi: 10.1007/s10802-007-9176-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammen C, Rudolph K, Weisz J, Rao U, Burge D. The context of depression in clinic-referred youth: Neglected areas in treatment. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 1999;38:64–71. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199901000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hankin B, Abramson L, Moffitt T, Silva P, McGee R, Angell K. Development of depression from preadolescence to young adulthood: Emerging gender differences in a 10-year longitudinal study. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1998;107:128–140. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.107.1.128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henggeler S, Schoenwald S, Borduin C, Rowland M, Cunningham P. Multisystemic treatment of antisocial behavior in children and adolescents. Guilford Press; New York: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Imbens G, Rubin D. Estimating outcome distributions for compliers in instrumental variables models. The Review of Economic Studies. 1997;64:555–574. [Google Scholar]

- Jo B. Statistical power in randomized intervention studies with noncompliance. Psychological Methods. 2002;7:178–193. doi: 10.1037/1082-989x.7.2.178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joiner T, Coyne J. The interactional nature of depression: Advances in interpersonal approaches. American Psychological Association; Washington, DC: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Kaslow N, McClure E, Connell A. Treatment of depression in children and adolescents. In: Gotlib I, Hammen C, editors. Handbook of depression and its treatment. Guilford Press; New York: 2002. pp. 441–464. [Google Scholar]

- Kessler R, Avenevoli S, Merikangas K. Mood disorders in children and adolescents: An epidemiologic perspective. Biological Psychiatry. 2001;49:1002–1014. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(01)01129-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovacs M. Children's Depression Inventory. Multi-Health Systems, Inc; North Tonawanda, NY: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Lewinsohn P, Clarke G. Group treatment of depressed individuals: The “coping with depression” course. Advances in Behaviour Research & Therapy. 1984;6:99–114. [Google Scholar]

- Lewinsohn P, Clarke G. Psychosocial treatments for adolescent depression. Clinical Psychology Review. 1999;19:329–342. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(98)00055-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewinsohn P, Clarke G, Hops H, Andrews J. Cognitive–behavioral treatment for depressed adolescents. Behavior Therapy. 1990;21:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- Lewinsohn P, Rohde P, Seeley J, Klein D, Gotlib I. Psychosocial functioning of young adults who have experienced and recovered from major depressive disorder during adolescence. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2003;112:353–363. doi: 10.1037/0021-843x.112.3.353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little R, Yau L. Statistical techniques for analyzing data from prevention trials: Treatment of no-shows using Rubin's causal model. Psychological Methods. 1998;3:147–159. [Google Scholar]

- Mason W, Kosterman R, Hawkins D, Haggerty K, Spoth R, Redmond C. Influence of a family-focused substance use preventive intervention on growth in adolescent depressive symptoms. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2007;17:541–564. [Google Scholar]

- Metzler CW, Biglan A, Rusby JC, Sprague JR. Evaluation of a comprehensive behavior management program to improve school-wide positive behavior support. Education & Treatment of Children. 2001;24:448–479. [Google Scholar]

- Michael K, Crowley S. How effective are treatments for child and adolescent depression? A meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review. 2002;22:247–269. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(01)00089-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller W, Rollnick S. Motivational interviewing: Preparing people for change. 2nd ed. Guilford Press; New York: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Mufson L, Moreau D, Weissman M, Klerman G. Interpersonal psychotherapy for depressed adolescents. Guilford Press; New York: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus user's guide. 4th ed. Muthén & Muthén; Los Angeles, CA: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Patterson G, Reid J, Jones R, Conger R. A social learning approach to family intervention: Families with aggressive children. Castalia Publishing Co; Eugene, OR: 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Reinecke M, Ryan N, Dubois D. Cognitive behavioral therapy of depression and depressive symptoms during adolescence: A review and meta-analysis. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 1998;37:26–34. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199801000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schochet I, Dadds M, Holland D, Whitefield K, Harnett P, Osgarby S. The efficacy of a universal school-based program to prevent adolescent depression. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 2001;30:303–315. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3003_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheeber L, Hops H, Davis B. Family processes in adolescent depression. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 2001;4:19–35. doi: 10.1023/a:1009524626436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stark K, Swearer S, Kurowski C, Sommer D, Bowen B. Targeting the child and the family: A holistic approach to treating child and adolescent depressive disorders. In: Hibbs E, Jensen P, editors. Psychosocial treatments for child and adolescent disorders: Empirically based strategies for clinical practice. American Psychological Association; Washington, DC: 1996. pp. 207–238. [Google Scholar]

- Stein D, Brent D, Bridge J, Kolko D, Birmaher B, Baugher M. Predictors of parent-rated credibility in a clinical psychotherapy trial for adolescent depression. Journal of Psychotherapy Practice Research. 2001;10:1–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trudeau L, Spoth R, Randall G, Azevedo K. Longitudinal effects of a universal family-focused intervention on growth patterns of adolescent internalizing symptoms and poly-substance use: Gender comparisons. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2007;36:725–740. [Google Scholar]