Abstract

OBJECTIVE: To explore the influence of referral bias on complication rates after vaginal hysterectomy.

PATIENTS AND METHODS: Community-based (local) and referral patients had benign indications and underwent vaginal hysterectomy from January 1, 2004, through December 31, 2005. We retrospectively evaluated patient characteristics, surgical procedures, and complications that occurred within 9 weeks after the index surgery. Complications were defined as admission to the intensive care unit, reoperation, hospital readmission, or medical intervention.

RESULTS: Of 736 patients, 361 (49.0%) were referred from outside the immediate 7-county area. Compared with local patients, referral patients were older (mean age, 54.5 vs 49.3 years; P<.001) and had lower body mass index (mean, 27.6 vs 28.7 kg/m2; P=.02). More referral patients had cardiovascular disease (4.2% vs 0.5%; P=.001) and prior myocardial infarctions (1.9% vs 0%; P=.007). Referral patients also had higher American Society of Anesthesiologists scores (score of 3 or 4, 12.6% vs 7.0%; P=.01) and longer length of hospitalization (mean, 2.6 vs 2.2 days; P<.001), and more underwent pelvic reconstruction (52.1% vs 41.3%; P=.004). Fewer referral patients had private insurance (74.5% vs 89.6%; P<.001). Despite these differences, overall complication rates were similar for referral and local patients (33.4% vs 29.7%; P=.28).

CONCLUSION: Although referral patients had more comorbid conditions than local patients, the groups had similar complication rates after vaginal hysterectomy.

Compared with local patients, referral patients were older; had lower body mass index, higher American Society of Anesthesiologists scores, longer length of hospitalization, and higher rates of cardiovascular disease and prior myocardial infarctions; and underwent more pelvic reconstruction; however, overall complication rates were similar.

Accurate information about patient outcomes is critical for establishing standards of care. However, published data may reflect selection or referral bias; outcome reports generally are based on series of patients studied at academic medical centers, and when compared with local patients, patients referred to tertiary academic medical centers often are distinctly different with respect to comorbid conditions and disease status. Consequently, reported outcomes and recommendations may not be applicable to the clinical spectrum of patients seen in the community.2 For example, Malkasian and Annegers3 studied referral bias among women undergoing their first treatment for endometrial carcinoma; even after adjusting for age, disease stage, and grade of cancer, referral patients had a lower 5-year survival rate than local patients. Conversely, Warner et al4 showed that community residents undergoing surgery had more comorbid conditions, more emergent procedures, and an increased risk of morbidity and death during the first 48 postoperative hours than did referral patients. This is similar to the findings from Whisnant et al,5 who reported that 2-day survival of referral patients with subarachnoid hemorrhage was markedly better than that of local patients because the referral group did not include those who died quickly or those who were too unstable to be transferred.

Because of these diverse findings, the actual effect of selection bias on specific outcomes should be quantified. This quantification is critical as we begin the process of outcomes assessment, particularly because it may be naïve and dangerous to assume that the referral group is the higher-risk group or that local and referral patients have equal risk of a given outcome. A thorough analysis of specific patient groups and specific surgical procedures is an integral part of evaluating outcomes and making appropriate risk adjustments if differences between patient groups exist. The objective of this study was to explore the influence of referral bias on complication rates among women undergoing vaginal hysterectomy. We hypothesized that women referred for care would have worse postoperative status and a higher frequency of perioperative complications than local patients.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

As a health care delivery system, Mayo Clinic is unique in that it provides most of the surgical care to residents in the surrounding community and also serves as a major tertiary referral center. Although patients are referred from throughout the United States and the world, approximately 60% of patients reside within a 500-mile radius of the clinic.6 Mayo Clinic is located in Olmsted County, which has a relatively stable population of 100,000 (most residents are of northern European descent).2

The study was approved by the Mayo Clinic Institutional Review Board. We identified all women (≥18 years) who underwent a vaginal hysterectomy for a benign indication from January 1, 2004, through December 31, 2005. Patients were included regardless of concurrent salpingectomy, oophorectomy, pubovaginal sling, or reconstructive pelvic surgery. However, patients who underwent any additional nonvaginal surgery, including laparoscopy, were excluded.

Residency status was determined by home address zip code. Patients were stratified into 2 cohorts: those residing in Olmsted County or the surrounding 6 Minnesota counties (local patients) and those from outside this 7-county area (referral patients).

Mayo Clinic and its affiliated hospitals have an integrated electronic medical records linkage system, which includes all details of medical, surgical, radiologic, laboratory, and follow-up care. A complete (inpatient and outpatient) record review was performed for each patient. Patient characteristics were collected, including age, race, insurance status, and home address. The distance between the home address and Mayo Clinic also was calculated. Pertinent medical history and surgical history were abstracted from records of the initial consultation or a previous health maintenance examination. Operative notes, anesthesia records, and postoperative progress notes were used to collect perioperative data, including dismissal dates and diagnoses. All postoperative correspondence was evaluated through dictated telephone conversations, scanned records from other institutions, and postoperative examinations.

Main outcome measures were complications that occurred within 9 weeks after the index surgery. Complications were defined as any medical problem requiring intervention (eg, blood transfusion for postoperative anemia, antibiotics for urinary tract infection), unplanned admission to the intensive care unit, reoperation, or hospital readmission.

Statistical Analyses

Comparisons between local and referral patients were evaluated with the χ2 or Fisher exact test for nominal variables and the 2-sample t test or Wilcoxon rank sum test for continuous variables. Data were analyzed using the SAS software package (version 9.0; SAS Institute, Cary, NC). All calculated P values were 2-sided, and P<.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

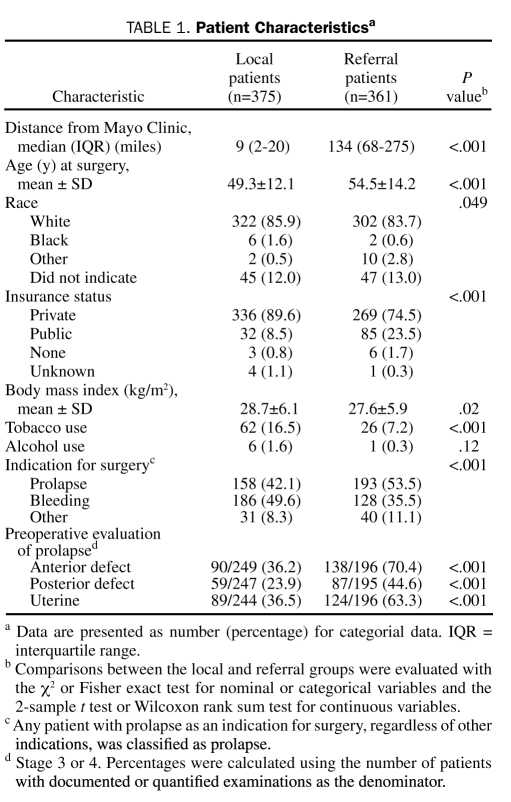

Local patients lived a median distance of 9 miles from Mayo Clinic (interquartile range, 2-20 miles), whereas referral patients resided a median of 134 miles away (interquartile range, 68-275 miles). Patient characteristics of the local and referral groups are summarized in Table 1. Referral patients were older and had a lower mean body mass index, and fewer had private insurance. Furthermore, referral patients reported less tobacco use than local patients. The indication for hysterectomy was uterine prolapse for most referral patients, whereas more local patients underwent hysterectomy for bleeding indications (eg, menorrhagia). Among the patients undergoing vaginal reconstructive surgery, more referral patients had a higher stage of prolapse (stage 3 or 4).

TABLE 1.

Patient Characteristicsa

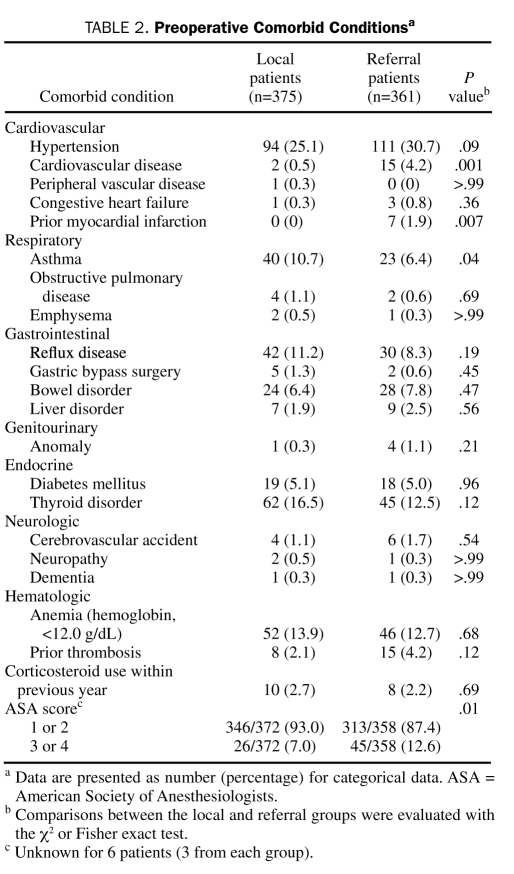

The comorbid medical conditions of local and referral patients are summarized in Table 2. Referral patients had more cardiovascular disease, including a greater number of myocardial infarctions, and less asthma than local patients. The American Society of Anesthesiologists score was also higher for referral patients than for local patients.

TABLE 2.

Preoperative Comorbid Conditionsa

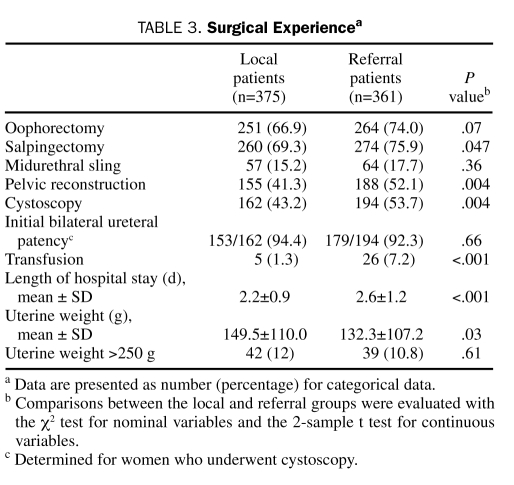

Surgical experiences for local and referral patients are summarized in Table 3. A greater proportion of referral patients underwent pelvic reconstructive surgery, which likely contributed to the longer duration of hospitalization. Additionally, more referral patients underwent intraoperative cystoscopy, but the groups showed no difference in initial bilateral ureteral patency. Although local patients had a higher mean uterine weight, no difference between groups was observed in the proportion of patients with uterine weight exceeding 250 g. The groups also had no differences in the frequency of concurrent oophorectomy or midurethral sling procedures; however, the frequency of concurrent salpingectomy was slightly higher for referral patients.

TABLE 3.

Surgical Experiencea

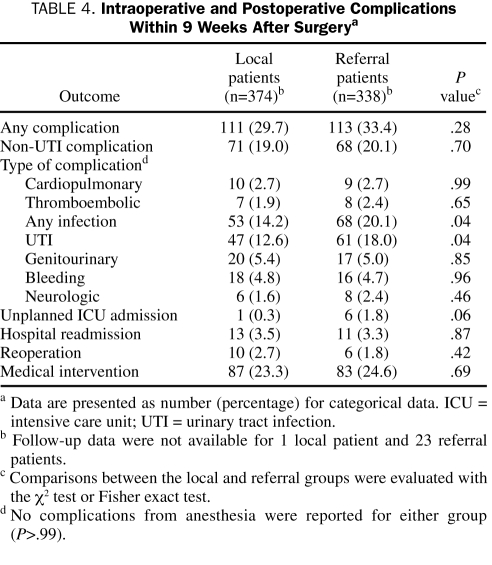

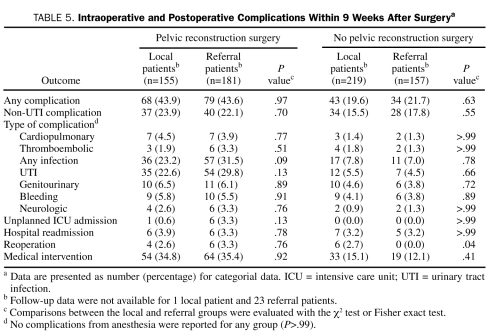

The postoperative complication rates for local and referral groups are summarized in Table 4. We had no follow-up information for 24 women; all but 1 of the patients lost to follow-up were in the referral group. Exclusion of those lost to follow-up from the analysis did not affect the results presented in Tables 1, 2 and 3 (data not shown). Overall, the frequency of any postoperative complication within 9 weeks after surgery did not differ between the groups. More referral patients had unplanned admissions to the intensive care unit, but the difference was not statistically significant (P=.06). However, local patients had a lower rate of any infections (14.2% vs 20.1%; P=.04) and urinary tract infections (12.6% vs 18.0%; P=.04). Postoperative complication rates for local and referral groups, stratified by type of surgery, are listed in Table 5. Overall, the complication rates tended to be lower among those who did not undergo pelvic reconstruction surgery. We observed no significant difference in the complication rates between the local and referral groups when patients were stratified by pelvic reconstruction surgery status. Nevertheless, within the group that did not undergo pelvic reconstruction surgery, more local patients than referral patients had a reoperation within 9 weeks after surgery.

TABLE 4.

Intraoperative and Postoperative Complications Within 9 Weeks After Surgerya

TABLE 5.

Intraoperative and Postoperative Complications Within 9 Weeks After Surgerya

DISCUSSION

Referral bias can complicate the generalization of findings from tertiary care centers because of inherent differences between referral and local patients. Patients referred to a tertiary care center commonly present with a greater number of clinically important comorbid conditions or worse disease processes than those in the local community. For example, Kennedy et al7 showed that patients referred to a tertiary care center for cataract surgery more often had ophthalmic disorders or surgical procedures before cataract extraction, had a higher frequency of combined surgical approaches, and were significantly younger than community-based patients. Similarly, patients referred for idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy had a worse prognosis compared with patients from the local community.8 However, Roger et al9 observed a lower 30-day mortality rate and better long-term survival of referral patients undergoing elective abdominal aortic aneurysm repair. As these studies illustrate, quantification of referral bias is imperative when postoperative complications and other outcomes are being addressed.

One of the main strengths of the current study is the ability to quantify referral bias as it applies to vaginal surgery. To our knowledge, this is the first article that describes the magnitude of referral bias within a group of women undergoing vaginal hysterectomy. Our study was a planned secondary analysis of an initial study that was sufficiently powered to detect small differences between groups (vaginal hysterectomy with and without additional reconstructive surgery). This is important for the identification of serious but infrequent complications. Moreover, the distribution of patients between referral and local groups was fairly similar (neither group was underrepresented). Two urogynecologists and 7 gynecologic oncologists performed the surgical procedures during the 2-year study period, which improves generalizability of the study findings.

Our study has several limitations. First, it was inherently limited by its retrospective nature. Not all potentially relevant variables could be assessed from the medical records, and some important measures may have been excluded. Second, all surgeons were fellowship trained and performed operations multiple times per week. Their skill level may not be representative of that of gynecologic surgeons at other institutions. Third, we examined follow-up data only through the first 9 postoperative weeks, and complications may have occurred after that period. However, complications due to surgery should diminish with time. Fourth, the complication rate could be underestimated if a referral patient's regular health care provider did not contact our institution about a specific complication. Nevertheless, we had 96% ascertainment for the study patients through 9 weeks and think that this concern is minimal.

Outcome-based quality improvement studies are becoming mainstream within surgical specialties since the advent of the National Surgical Quality Improvement Program. Outcome assessment allows a direct comparison of perioperative complications, although the residence status of patients receiving care at tertiary medical centers is rarely reported. In the current study, referral patients and local patients had differences in age, comorbid conditions, and American Society of Anesthesiologists score, but the overall rate of perioperative complications did not differ. The benefit of an academic center in treating higher-risk (referral) patients could have been underestimated without investigating the influence of selection bias. Of note, our referral patients had more medical comorbid conditions, longer hospitalizations, and lower rates of private health insurance. These differences have profound implications on reimbursements for referral centers.

Further studies are needed to examine the role of referral bias in medical and surgical intervention. Do academic medical centers or tertiary care centers treat different types of patients than do local community hospitals? If they do, how can comparisons of patient outcomes be accurate if inherent differences exist between local and referral patients? Characterization of these differences and risk-adjusted outcomes of various medical and surgical procedures are needed to provide meaningful assessment of outcome-based quality improvement initiatives.

CONCLUSION

Patients referred for vaginal hysterectomy were older and had more cormorbid conditions, longer hospitalizations, and lower rates of private health insurance than local patients. However, both groups had similar complication rates. Referral bias should be routinely assessed in any quality improvement program.

Footnotes

Portions of this manuscript have been published in abstract form.1

Supported in part by research grant AR30582 from the National Institutes of Health, US Public Health Service.

REFERENCES

- 1.Heisler CA, Melton LJ, Weaver AL, Gebhart JB. Selection (referral) bias in women undergoing vaginal hysterectomy: the Mayo Clinic experience [abstract 23]. J Pelvic Med Surg. 2008;14(2):97-98 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Melton LJ., III Selection bias in the referral of patients and the natural history of surgical conditions. Mayo Clin Proc. 1985;60(12):880-885 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Malkasian GD, Annegers JF. Endometrial carcinoma comparison of Olmsted County and Mayo Clinic referral patients. Mayo Clin Proc. 1980;55(10):614-618 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Warner MA, Hosking MP, Lobdell CM, Offord KP, Melton LJ., 3rd Effects of referral bias on surgical outcomes: a population-based study of surgical patients 90 years of age or older. Mayo Clin Proc. 1990;65(9):1185-1191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Whisnant JP, Sacco SE, O'Fallon WM, Fode NC, Sundt TM., Jr Referral bias in aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. J Neurosurg. 1993;78(5):726-732 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Steckelberg JM, Melton LJ, 3rd, Ilstrup DM, Rouse MS, Wilson WR. Influence of referral bias on the apparent clinical spectrum of infective endocarditis. Am J Med. 1990;88(6):582-588 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kennedy RH, Brubaker RF, O'Fallon WM, Melton LJ., 3rd Impact of referral bias on evaluation of cataract surgery. Am J Ophthalmol. 1985;99(2):149-153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Redfield MM, Gersh BJ, Bailey KR, Ballard DJ, Rodeheffer RJ. Natural history of idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy: effect of referral bias and secular trend. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1993;22(7):1921-1926 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Roger VL, Ballard DJ, Hallett JW, Jr, Osmundson PJ, Puetz PA, Gersh BJ. Influence of coronary artery disease on morbidity and mortality after abdominal aortic aneurysmectomy: a population-based study, 1971-1987. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1989;14(5):1245-1252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]