Abstract

Alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma is an aggressive skeletal muscle cancer of childhood. Our initial studies of rhabdomyosarcoma gene expression for patients enrolled in a national clinical trial suggested that Platelet-derived Growth Factor Receptor A (PDGFR-A) may be a mediator of disease progression and metastasis. Using our conditional mouse tumor models that authentically recapitulate the primary mutations and metastatic progression of alveolar rhabdomyosarcomas in humans, we found by immunoblotting and immunokinase assays that PDGFR-A and its downstream effectors, MAPK and Akt, were highly activated in both primary and metastatic tumors. Inhibition of PDGFR-A by RNA interference, small molecule inhibitor or neutralizing antibody had a dramatic effect on tumor cell growth both in vitro and in vivo, although resistance evolved in one-third of tumors. These results establish proof-of-principal for PDGFR-A as a therapeutic target in alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma.

Introduction

Rhabdomyosarcomas are the most common soft tissue sarcoma of childhood(Arndt and Crist, 1999). The alveolar subtype of rhabdomyosarcoma is a paradigm for refractory and incurable solid tumors because more than half of children at diagnosis have either regional lymph node or distant metastases. Little is known about the mechanism of progression in this disease, and the outcome for metastatic alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma has been dismal for the past two decades despite improvements in surgical technique, radiation delivery, and chemotherapy intensification(Arndt and Crist, 1999). Understanding the mechanisms of progression and metastasis are paramount to designing better therapies.

We have succeeded in generating conditional mouse models of alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma by re-creating the mutations that are hallmarks of this sarcoma(Keller et al., 2004a; Keller et al., 2004b; Keller et al., 2001). In humans, alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma are nearly always associated with a chromosome rearrangement (translocation) fusing a Pax gene (either Pax3 or Pax7) to the Fkhr gene, thereby forming a chimeric transcription factor that acts as an oncogene(Arndt and Crist, 1999). In addition, Cdkn2a or p53 tumor suppressor mutations accompany Pax3:Fkhr mutation in more than half of cases(Takahashi et al., 2004). Our conditional knockout mouse models recapitulate these changes by simultaneously activating Pax3:Fkhr and inactivating either Cdkn2a or p53. These mice develop tumors that are as aggressive as advanced stage human alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma(Keller et al., 2004b).

To explore the factors responsible for disease progression, we previously performed gene expression analysis for human rhabdomyosarcoma biopsies at diagnosis from children enrolled in a clinical trial (Blandford et al., 2006). From our study group of uniformly-treated IRS-IV Study patients (Heldin and Westermark, 1999), we confirmed that the known downstream targets of Pax:Fkhr were in fact enriched in Pax:Fkhr positive alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma relative to their expression in non-alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma. Specifically, we found that mRNA levels of Platelet-derived Growth Factor Receptor A (PDGFR-A for the human gene and Pdgfr-a for the mouse gene) predicted decreased long term disease-free survival when adjusted for known clinical covariates.

PDGFR-A is a receptor tyrosine kinase similar to but not identical in function to the other PDGF receptor, PDGFR-B. PDGF signaling is mediated by a complex combination of homo- and hetero-dimeric receptors and ligands (Devare et al., 1983). Activation of PDGFR-A homodimers by ligands PDGF-AA or PDGF-CC is known to be required for formation of smooth muscle cells and other cell types (MacDonald et al., 2001). Furthermore, PDGFR-A is believed to mediate multiple cellular behaviors such as migration, proliferation and cell survival via activation of several downstream pathways including MAPK (Erk1/Erk2), PI3K/Akt and PLCγ/PKC (Choudhury et al., 2000; Jonkers and Berns, 2002; Mehrotra et al., 2004).

Two malignancies of children, medulloblastoma and hypereosinophilic syndrome (HES) are already known to have aberrant PDGFR-A signaling that responds to PDGFR-A inhibition in vitro and/or clinically (Stover et al., 2006; Stover et al., 2005). In these malignancies and others, the emergence of receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors that are partially or highly selective for PDGFR-A allows one to evaluate both the preclinical and clinical relevance of PDGFR-A signaling in a broad range of malignancies (Stover et al., 2006). In this report, we investigate whether PDGFR-A is an important determinant of disease progression in alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma.

Results

PDGFR-A mRNA is over-expressed in human and mouse alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma

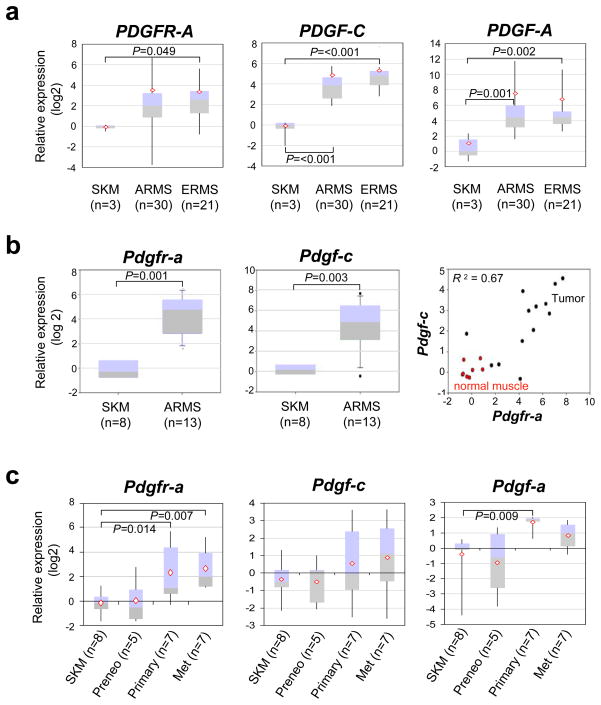

To determine the frequency of over-expression for PDGFR-A and its ligands in childhood muscle cancers, we compared expression by RT-PCR amongst normal human muscle, alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma and embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma (Supplementary Table 1). Both alveolar and embryonal rhabdomyosarcomas expressed the PDGFR-A receptor and its ligands PDGF-C and PDGF-A at one to two orders of magnitude greater than normal skeletal muscle (Figure 1a). In mice, quantitative RT-PCR revealed a strong correlative relationship between Pdgfr-a and Pdgf-c expression (Figure 1b), suggesting a possible autocrine loop.

Figure 1.

Quantitative RT-PCR showing over-expression of PDGFR-A and its ligands in human and mouse alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma

(a) PDGFR-A (left) and its ligands PDGF-C (center) and PDGF-A (right) are over-expressed relative to skeletal muscle in both human alveolar (ARMS) and embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma (ERMS). This data was partially reported previously (Blandford et al., 2006). (b) Pdgfr-a (left) and Pdgf-c (center) expression in mouse Pax3:Fkhr, p53 tumors versus normal skeletal muscle. (right) In tumors, Pdgfr-a and Pdgf-c expression have a correlation coefficient of 0.67. (c) Independent samples demonstrate stepwise trend increases in Pdgfr-a, Pdgf-c and Pdgf-a expression for the transition from normal skeletal muscle (12 week old), to preneoplastic (Pax3:Fkhr expressing) skeletal muscle (9 week old – 18 week old), to large primary tumors then to metastatic tumors (primary and metastatic tumors were from the same animals).

Using paired mouse preneoplastic tissues and tumor samples, we sought to determine the phase of tumor development when Pdgfr-a is upregulated. At the preneoplastic phase in Pax3:Fkhr expressing skeletal muscle, expression of Pdgfr-a and its ligands Pdgf-a and Pdgf-c are low; however, expression of all three is high for advanced primary tumors and metastatic tumors, which both express Pax3:Fkhr and lack p53 (Figure 1c). This result led us to speculate that PDGFR-A expression was related to disease progression and/or that p53 loss of function was required for PDGFR-A transcriptional activation.

PDGFR-A protein is over-expressed in human and mouse alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma

In order to confirm that PDGFR-A mRNA expression was also reflected at the protein level, and that expression of PDGFR-A was from the tumor cells and not the surrounding stroma or vessels, we performed immunohistochemistry on 73 human alveolar and embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma specimens (n=34 embryonal and n=39 alveolar, respectively) as well as 20 mouse alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma (n=12 Pax3:Fkhr, p53 tumors and n=8 Pax3:Fkhr, Cdkn2a tumors). As a positive control for over-expression we used ovarian carcinoma for which PDGFR-A has shown to be involved in an autocrine loop linked to metastatic progression (Matei et al., 2006) (Figure 2a). Ovarian carcinoma demonstrated diffuse moderate staining, equal to or less than all (100%) of human embryonal and alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma tumors tested (Figure 2a). Mouse alveolar rhabdomyosarcomas also demonstrated Pdgfr-a expression at a level above or exceeding ovarian carcinoma (Figure 2a). Thus, PDGFR-A expression at the protein level was validated for both alveolar and embryonal human rhabdomyosarcomas, and the mouse model was confirmed to reflect this characteristic of human tumors. In young mouse skeletal muscle (postnatal days 12 and 30), satellite cells also showed intense staining (Figure 2a), which has not been previously reported.

Figure 2.

High level of protein expression of PDGFR-A in human and mouse alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma

(a) PDGFR-A is over-expressed to remarkably high level in human alveolar (bottom row, left) and embryonal (center row, right) rhabdomyosarcoma relative to young mouse skeletal muscle (top row, right, postnatal days 12 and 30) and human ovarian cancer (center row, left). The mouse model of alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma also strongly over-expressed Pdgfr-a (bottom row, right). Unstained blue cells are entrapped myofibers. In young muscle, possible satellite cells are shown with white arrows in the insets. (b) Immunoblotting (IB) for Pdgfr-a isolated from primary mouse tumors and metastases. Pdgfr-a has high direct tyrosine kinase activity as well as PI3 kinase activity in these samples.

To demonstrate that PDGFR-A protein was not only present but also activated, we examined Pdgfr-a tyrosine kinase activity and PI3 kinase activity by Pdgfr-a immunoprecipitation assay on paired mouse skeletal muscle and tumor samples. Both Pdgfr-a and PI3 kinase were highly activated in primary tumors and paired metastatic tumors relative to normal skeletal muscle (Figure 2b). Thus, Pdgfr-a is not only uniformly expressed in rhabdomyosarcoma, but this receptor tyrosine kinase is also activated.

PDGFR-A is a Transcriptional Target of Pax3:Fkhr

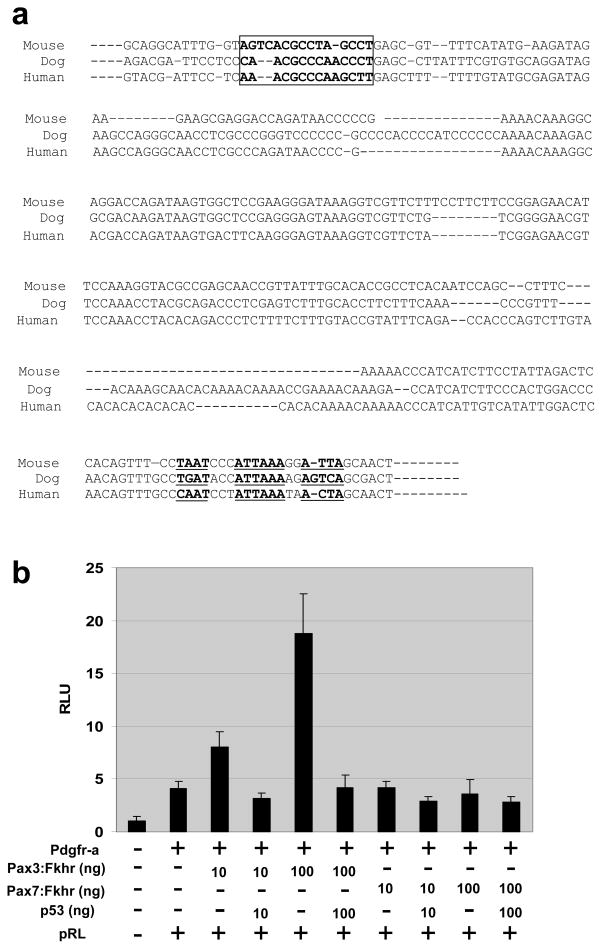

Epstein et al previously reported that Pdgfr-a is a direct transcriptional target of Pax3:Fkhr in vitro via a response element upstream of the mouse Pdgfr-a transcriptional initiation site(Epstein et al., 1998). This region has 87.4% identity between mouse and human, including conservation of sequence and spacing for a Pax3 paired domain DNA binding site (AGTCACGCCTAGCCT) (Figure 3a, boxed) and a Pax3 homeodomain DNA binding site (core ATTA consensus sites) (Figure 3a, underlined) located in a region 657 base pairs (bp) upstream of the Pdgfr-a start site. Earlier in our study, we found no elevation of Pdgfr-a expression in vivo for Pax3:Fkhr expressing, p53 wild type preneoplastic skeletal muscle (Figure 1c). To test whether p53 loss of function was required for Pax3:Fkhr activation of Pdgfr-a, we performed transfection reporter assays in p53 deficient mouse embryonic fibroblasts. We found that activity from the 657 bp promoter increased in a dose dependent manner (up to 18 fold) with increasing concentrations of transfected Pax3:Fkhr (but not Pax7:Fkhr), and that transfection of wild type p53 abrogated the effects of Pax3:Fkhr (Figure 3b). To understand why Pdgfr-a expression would require the absence of p53, we examined the 657 bp promoter region for a canonical p53 binding consensus site (RRRCWWGYYY) but found none. However, an indirect Pax3:Fkhr – p53 interaction is feasible given reports of Pax3 – p53 genetic interactions in embryonic development(Pani et al., 2002) and given reports of promoter competition in vitro(Underwood et al., 2007). Taken altogether, these data suggested an explanation of Pdgfr-a transcriptional activation in alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma.

Figure 3.

Pdgfr-a luciferase reporter assay in p53(−/−) mouse embryonic fibroblasts

(a) A response element upstream of Pdgfr-a transcriptional initiation site is 87.4% conserved between human, mouse and dog. The Pax3 paired-domain DNA binding site (AGTCACGCCTAGCCT) and Pax3 homeodomain DNA binding site (ATTAA) are boxed and underlined, respectively. (b) Pdgfr-a is induced when Pax3:Fkhr is present and p53 is absent. This effect is dose-responsive for Pax3:Fkhr. However, Pax7:Fkhr did not induce Pdgfr-a. Luciferase activity was normalized using Renilla (pRL) luciferase.

Mouse rhabdomyosarcoma cell lines reflect Pdgfr-a activation in mouse primary tumors

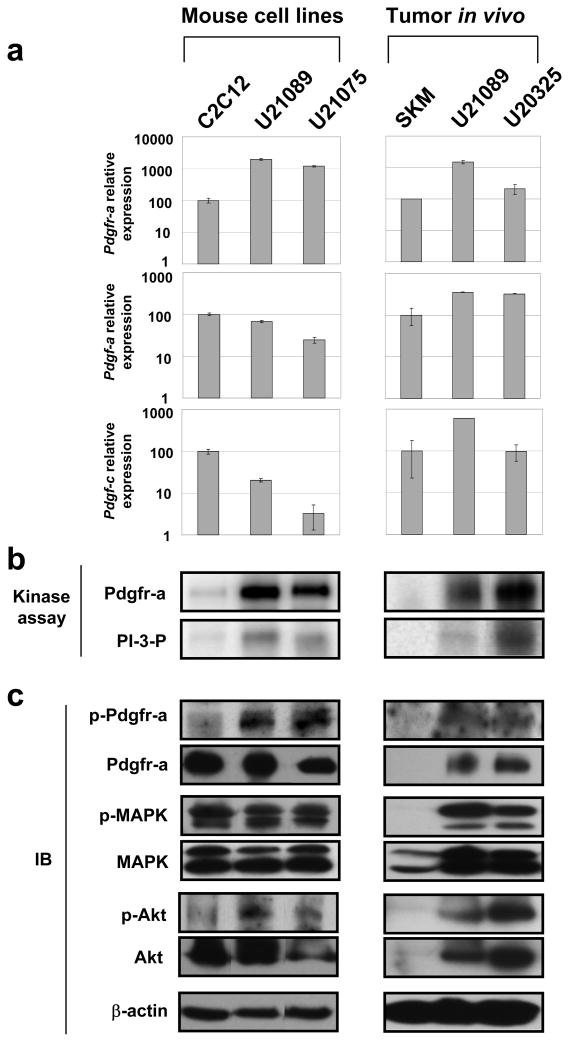

To dissect Pdgfr-a signaling pathway in alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma in vitro, we had established alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma primary tumor cell cultures (U21075 and U21089) from biopsies taken at necropsy for mice with advanced primary tumors. To characterize the steady state for mouse rhabdomyosarcoma cell lines for our studies, we examined expression of Pdgfr-a, its ligands Pdgf-a and Pdgf-c, and activation status of Pdgfr-a as well as potential downstream molecules MAPK and Akt. The murine tumor cell lines expressed high level of Pdgfr-a protein relative to normal myoblast cell lines (C2C12) (Figure 4a). At the enzyme level, the tumor cell lines showed higher kinase activity of both Pdgfr-a and PI3K, as well as high level of phospho-Pdgfr-a, phospho-MAPK and phospho-Akt (the later two of which could be the direct or indirect result of Pdgfr-a activation) (Figure 4b and c). Thus, the primary tumor cell cultures were representative of the primary tumors from which the cell lines were derived (Figure 4a, b and c) and could be used in subsequent studies for investigating Pdgfr-a signaling in alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma. Of the human cell lines we tested (Rh5, Rh18, Rh30 and RMS783; data not shown), only Rh5 was representative of human rhabdomyosarcomas, despite our results from tumor microarrays which show that primary tumors uniformly overexpress PDGFR-A (Supplementary Figure 2a b and c). This asynchrony between cell line characteristics and primary tumor characteristics underlines the need for new rhabdomyosarcoma cell lines and/or physiologically-relevant mouse models such as the ones that we have developed.

Figure 4.

Confirmation of Pdgfr-a expression and activation in mouse rhabdomyosarcoma cell lines

(a) Quantitative RT-PCR for Pdgfr-a, Pdgf-a and Pdgf-c. (b) High levels of Pdgfr-a activation of demonstrated by Pdgfr-a direct tyrosine kinase assay and PI3 kinase assay for both cell lines and the primary tumors from which they were derived. (c) Western blotting verifies expression of Pdgfr-a as well as expression and phosphorylation for downstream mediators, MAPK and Akt with non-phospho- and phospho antibodies. U21089 and U21075 cell lines are derived from metastatic chest and limb of mouse ARMS, respectively. C2C12 is a mouse normal myoblast cell line. SKM; normal skeletal muscle.

Down-regulation of Pdgfr-a inhibits mouse tumor cell growth in vitro

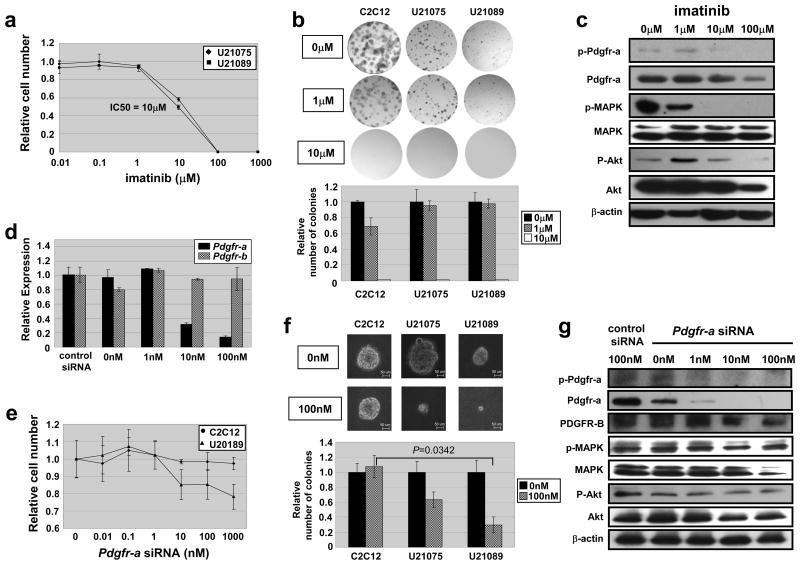

To investigate whether imatinib mesylate, a partially selective PDGFR antagonist, inhibits growth of alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma, we treated mouse rhabdomyosarcoma primary cell cultures (U21075 and U21089) with imatinib (0.1– 1000 μM). The growth of cell lines was inhibited by 40% at drug concentrations of 10μM for 72 hours {Figure 5a, p=0.02 (U21075) and p=0.01 (U21089)}. We also performed anchorage dependent colony formation assays to determine the effect on early tumor cell growth, and 10μM of imatinib completely inhibited cell growth in all tested cell lines including a mouse myoblast control cell line, C2C12 (Figure 5b). We further confirmed that phosphorylation of Pdgfr-a, MAPK and Akt was inhibited in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 5c), and that 10μM imatinib effectively inhibited the phosphorylation of Pdgfr-a, MAPK and Akt.

Figure 5.

Growth inhibition of Pdgfr-a by imatinib and siRNA in vitro

(a) In vitro cell growth assay of mouse ARMS cell lines (U21075 and U21089) treated with varied doses of imatinib. (b) Anchorage-dependent colony formation is inhibited for mouse ARMS cell lines (U21075 and U21089) and normal skeletal muscle cell (C2C12) treated with increasing doses of imatinib. (c) Imatinib reduces phosphorylation of Pdgfr-a and downstream mediators, MAPK and Akt, in mouse ARMS cell line (U21089) in a dose dependent manner. (d) Knockdown efficiency by RT-PCR in U21089. Note that Pdgfr-b levels are not affected by Pdgfr-a siRNA. (e) In vitro cell growth assay of mouse ARMS cell lines (U21089) treated with varied doses of Pdgfr-a siRNA. (f) Anchorage-dependent colony formation is inhibited to a greater extent for mouse ARMS cell lines (U21075 and U21089) than for normal skeletal muscle cell (C2C12) treated with Pdgfr-a siRNA. (g) Pdgfr-a siRNA reduces Pdgfr-a, MAPK and Akt phosphorylation in mouse ARMS cell line (U21089) in a dose-dependent manner.

Although these data were consistent with imatinib inhibiting the growth of alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma cell lines by Pdgfr-a inhibition, imatinib is not specific for PDGFR-A because it also inhibits other receptor tyrosine kinases, e.g. PDGFR-B, c-Abl and c-Kit(Capdeville et al., 2002; Cools et al., 2003). Therefore, to better test whether Pdgfr-a is an important effector of tumor growth, a mouse rhabdomyosarcoma cell line (U21089) was transfected with Pdgfr-a siRNA. We confirmed that the level of Pdgfr-a mRNA but not Pdgfr-b was decreased by ≥ 90% at 100 nM of Pdgfr-a siRNA in both C2C12 and U21089 (Figure 5d). Growth of U21089 showed 15–22% decrease in growth when treated with 100–1000nM of Pdgfr-a siRNA for 72 hours, while growth of C2C12 was not inhibited (Figure 5e). Anchorage-independent colony formation was even more markedly inhibited at 100nM of Pdgfr-a siRNA in both U21075 cells (40% inhibition) and U21089 cells (70% inhibition), while C2C12 was not inhibited (Figure 5f). A similar was seen for anchorage-dependent colony formation assay (data not shown). We found that endogeneous levels of Pdgfr-a, MAPK and Akt and their phophorylated versions were decreased in a dose dependent manner of Pdgfr-a siRNA, while endogeneous levels of Pdgfr-b were relatively unchanged (Figure 5g). These results suggest that specific inhibition of Pdgfr-a efficiently suppresses mouse alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma cell growth in vitro. Consistent with these results from mouse tumor cell cultures, PDGFR-A siRNA in a human alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma cell line (Rh5) efficiently knocked down PDGFR-A and resulted in a 30–40% decrease in growth of tumor cells but not a control skeletal muscle cell line (SkMC) (Supplementary Figure 2d and e). Altogether, these data indicate that tumor cell growth is imatinib-inhibitable, and that PDGFR-A is an important target of imatinib for this disease.

To further delineate the mechanism by which Pdgfr-a inhibition leads to decreased rhabdomyosarcoma growth, we performed cell cycle analysis and programmed cell death analysis by FACS in cells with Pdgfr-a knock down. Treatment of rhabdomyosarcoma cells with 10 nM Pdgfr-a siRNA for 48 h induced a significant increase in annexin-V positive/propidium iodide (PI) positive cells from 8.3 to 21.6 %, consistent with induction of late apoptotic/necrotic cell death (P=0.0037). Increase of the cleaved form of caspase-3 at 10nM Pdgfr-a siRNA suggests that cell death caused by Pdgfr-a siRNA involves classical caspase-dependent apoptosis (Supplementary Figure 3a, b and c). To a lesser extent, elevated percentages of annexin-V-positive/PI-negative cells were also observed, reflecting early apoptotic cells. Cell cycle distribution was not changed by treatment with Pdgfr-a siRNA (Supplementary Figure 3d). These results suggest that Pdgfr-a signals to maintain cell survival rather than to induce cell cycle progression in rhabdomyosarcoma cells.

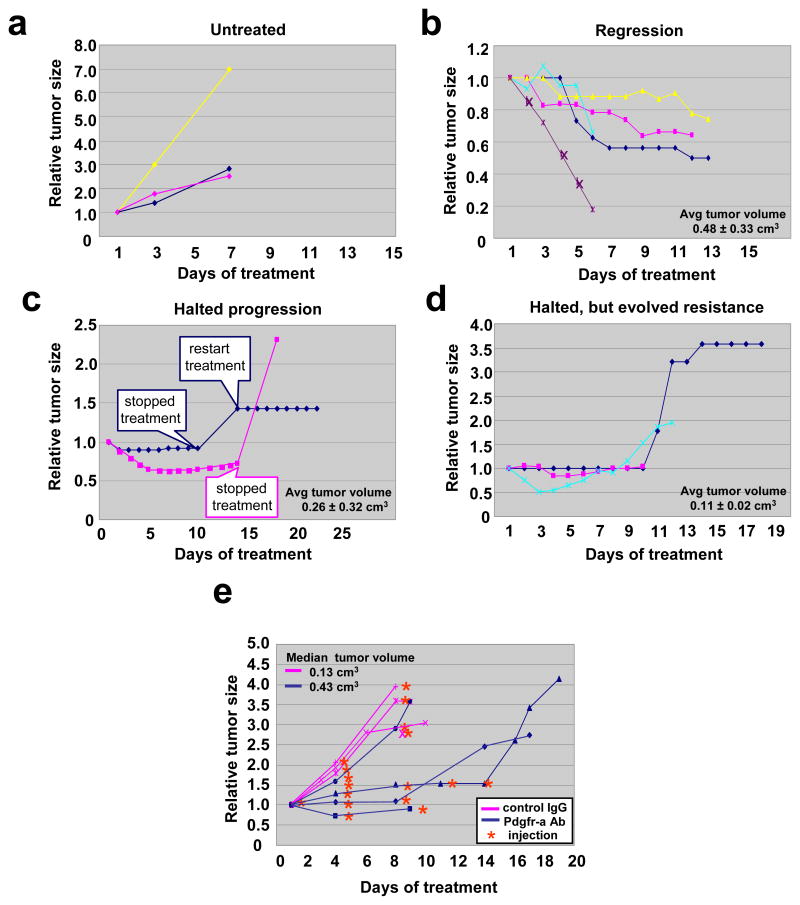

Imatinib has significant therapeutic effects in the alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma mouse model

To examine the potential therapeutic effect of Pdgfr-a inhibition in rhabdomyosarcoma progression in vivo, we treated ten tumor-bearing Pax3;Fkhr, p53 mutant mice with imatinib at a dose of 50 mg/kg/daily by oral gavage (Figure 6a–e). Untreated tumors became three to seven times their original size in 6 days (Figure 6b, untreated). In contrast, five out of ten mice treated with imatinib had partial responses or stabilization of disease, i.e. no progression for 1–2 weeks (Figure 6a and c). Two mice had only sustained stabilization of disease (Figure 6d). Although animals became more ambulatory on treatment, serious side effects of imatinib were seen, e.g. animals often lost greater than 15–20% bodyweight (data not shown). For that reason, we attempted to lengthen the interval between doses. We found that short-term discontinuation of imatinib led to rapid tumor progression. Re-treatment resulted in an ability to stabilize disease, but did not cause regression. In another three out of ten mice, initial stabilization of disease was followed by the gradual evolution of resistance (Figure 6e). The larger tumors (average initial tumor volume = 0.48 ± 0.33 cm3) were most responsive, suggesting an important role of Pdgfr-a signaling late in disease. Ironically, we found most smaller tumors were more likely to evolve resistance (Figure 6e). We also observed asynchronous response of primary tumors but resistance of metastases in the same animals (Supplementary Figure 1). These data implied that PDGFR-A is a potential therapeutic target in advanced alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma, but that preventing or addressing resistance will be essential.

Figure 6.

Dramatic effect of imatinib and Pdgfr-a neutralizing antibody on rhabdomyosarcoma in vivo

(a) Tumor-bearing mice were treated with imatinib at a dose of 50mg/kg/daily by oral gavage. Response of primary chest tumor before and after treatment of imatinib. Untreated tumors became 3–7 times their original size in 6 days (b). In contrast, imatinib lead to tumor regression in 5 of 10 cases (c) or halted tumor progression in 2 of 10 cases (d). Halted progression followed by evolution of resistance was observed in 3 of 10 cases (e). Note that tumors that tended to regress were in fact larger on average than tumors that only halted growth when treated with imatinib. (f) Tumor-bearing mice were treated with Pdgfr-a neutralizing antibody at a dose of 1.25mg/kg twice a week by intraperitoneal injection. Tumor-bearing control animals were treated with normal goat IgG antibody at the same dose. Example showing that the Pdgfr-a neutralizing antibody halted tumor growth for the period of injection, while tumors get 2.5–4 times larger after discontinuance of injection. (g) Quantitative growth inhibition in 3 out of 4 mice with spontaneously-arising tumors that were treated with Pdgfr-a neutralizing antibody, but no effect of a dose-matched control IgG antibody in three different tumor-bearing mice. The effect of tumor inhibition diminishes after 8–14 days, coinciding with the anticipated development of immune-mediated neutralization of the foreign Pdgfr-a neutralizing antibody. We speculate that if it were financially feasible to increase the dose of the neutralizing antibody, a more dramatic effect on tumor size might be achieved.

Pdgfr-a neutralizing antibody recapitulates imatinib responses in vivo

The development of neutralizing antibody technology has allowed for the production of very specific target-directed immunotherapies. To test the effect of specific inhibition of Pdgfr-a in alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma mouse models, we treated tumor-bearing mice with a Pdgfr-a neutralizing antibody at a dose of 1.25mg/kg twice a week by intraperitoneal injection (Figure 6f). For the control cohort of tumor-bearing mice, we injected normal goat IgG antibody. The tumors treated with normal goat IgG antibody became more than 3 times larger in 9 days and required early euthanasia. Mice treated with Pdgfr-a neutralizing antibody experienced stabilization of disease during the period before an allo-reaction could develop against the neutralizing antibody (Figure 6g and Supplementary Figure 4a). Using quantum dot (Qdot) nanocrystal conjugated-Pdgfr-a neutralizing antibody, we confirmed that the neutralizing antibody could be targeted to tumor while it also accumulated in lung, lymph node and bladder (Supplementary Figure 4b). These profound effects halting tumor progression further support an important role for PDGFR-A in tumor growth.

Discussion

In this report we evaluated PDGFR-A as a potential therapeutic target in pediatric alveolar rhabdomyosarcomas based on our previous finding that PDGFR-A expression was associated with decreased survival in this cancer (Blandford et al., 2006). Pdgfr-a has been previously reported and now confirmed by the present study to be a target of the translocation-mediated chimeric transcription factor Pax3:Fkhr, which is found in the majority of alveolar rhabdomyosarcomas (Arndt and Crist, 1999). We have shown that PDGFR-A overexpression as a protein parallels its mRNA expression and that PDGFR-A has high direct kinase activity. Imatinib, which inhibits Pdgfr-a, has a significant effect on arresting or reversing growth of primary tumors in vivo using our conditional mouse model of alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma. We also evaluated the phosphorylation and activation status of reported downstream intermediates of Pdgfr-a signaling, MAPK and Akt, both in vivo and in vitro in the presence and absence of imatinib as well as Pdgfr-a RNA interference. Phosphorylation of MAPK and Akt intermediates were indeed linked to Pdgfr-a activation, as confirmed by a dose-responsive effect of Pdgfr-a specific siRNA. At the cellular level, Pdgfr-a knockdown was associated with decreased cell survival (increased apoptosis). The implication of Pdgfr-a as an important effector of disease progression was further strengthened by data showing that a Pdgfr-a neutralizing antibody had a similar therapeutic effect to imatinib in vivo.

PDGF signaling is mediated by a complex combination of homo- and hetero-dimeric receptors and ligands(Devare et al., 1983). We found that mRNA for PDGFR-A and its ligands PDGF-A and PDGF-C were highly over-expressed in human and mouse primary tumors compared to normal skeletal muscle. This result suggested a ligand-dependent autocrine or paracrine loop causing PDGFR-A activation in alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma. The use of shRNA reagents targeting PDGF-A and/or PDGF-C would provide a direct test of an autocrine or paracrine role for these growth factors in the PDGFR-A signaling activation of alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma, and will be the subject of future studies.

The distinction between PDGFR-A and PDGFR-B signaling is increasing with the discovery that PDGFR-A, not PDGFR-B, is localized to and activated in a specialized structure on the cell membrane, the primary cilium, where PDGFR-A can activate MAPK and Akt signaling(Schneider et al., 2005). We had examined the expression of Pdgfr-b and did not see strong associations with Pdgfr-a expression as one might expect if heterodimeric receptor complexes were predominant (data not shown). Recently, PDGFR-A has been shown to correlate with decreased survival irrespective of PDGFR-B expression(Armistead et al., 2007). However, imatinib has a broad range of specificity for other receptor tyrosine kinases such as cAbl, c-kit, and others, and we do not exclude the possibility that cell growth inhibition by imatinib in vitro may be partially due to the inhibition of these other receptors. However, cell growth inhibition using Pdgfr-a siRNA suggests that Pdgfr-a is at least a major factor in tumor progression of alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma. Importantly, treatment with a Pdgfr-a neutralizing antibody halted tumor progression of alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma in vivo. In these mouse studies, we injected Pdgfr-a neutralizing antibody at a dose of 1.25mg/kg twice a week. We speculate that a higher dose of the neutralizing antibody might have induced regression of the tumor to the same extent as treatment of imatinib. However, even if PDGFR-A inhibition did not account for the full effect of imatinib, PDGFR-A blockade should be considered as an important component of a multi-target/combination therapy approach to treating alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma. Given that the cure rate for metastatic alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma has been unchanged for 3 decades, it is likely that no single molecularly targeted therapy will be sufficient for long term clinical success.

Recent interesting reports suggest that imatinib anti-tumor activity may be mediated enhanced dendritic cell/natural killer cell host immune response. Similarly, an antibody-mediated therapeutic effect might be mediated by a direct cytotoxic immune response. However, at least in this model, immunohistochemistry of untreated non-necrotic (viable) tumor revealed only scattered CD163+ histiocytes, no lymphocytes and no CD56+ natural killer cells. The frequency of histiocytes did not change with imatinib or PDGFR-A antibody treatment (data not shown). Therefore, immune modulation does not appear to have played a significant role in the anti-tumor effect for this set of studies.

In our studies, one-third of mice showed resistance to imatinib. We also observed that imatinib sometimes could not sustain inhibition of metastatic tumor growth, even when the primary tumor continuously responded (Supplementary Figure 1). This paradigm is not unfamiliar in sarcomas: gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GIST) provide a foundation for understanding imatinib resistance. In GIST, resistance is often mediated by point mutation in PDGFR-A(Heinrich et al., 2003). We speculate that in rhabdomyosarcoma, PDGFR-A resistance may be mediated by self-activating mutations. Alternatively, resistance may be mediated by activation of parallel signaling pathways as seen in other cancers (Engelman et al., 2007). These mechanisms are the subject of ongoing studies. In either of these cases, it will be critical to better understand how drug resistance emerges before moving anti-PDGFR-A therapy to clinical trials.

Materials and Methods

Human samples

Human muscle and frozen tumor samples were provided by the Cooperative Human Tissue Network (CHTN, Columbus, OH) which is funded by the National Cancer Institute. The tissue samples obtained under an institutional review board-approved protocol have been previously described {i.e. Cohort #2, (Blandford et al., 2006)}. Other investigators may have received specimens from the same subjects.

Gene expression analysis

Total RNA was isolated from tumors using Trizol (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) according to manufacturer’s specifications. The RNA was then purified using manufacturer’s instructions for the Qiagen RNeasy miniprep cleanup kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA), with the included optional step of DNase I treatment. Single-stranded cDNA was generated from total RNA using a cDNA synthesis kit (Fermentas, Hanover, MD) according to manufacture’s instruction. For human samples, TaqMan probes were used for RT-PCR as previously described (Blandford et al., 2006). For mouse gene expression studies, real-time PCR was performed using SYBR® Green PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) on an ABI Prism 7500HT sequence detection system following manufacturer’s instructions. Primers used were as follows: Pdgfr-a (5′-CCATGCAGTTGCCTTACGAC – 3′ and 5′ - AGAGCCTGCTTT TCACTAGACC – 3′), Pdgf-c (5′ – GACTGTGCCAGGAAAGCAG – 3′ and 5′ –GATCTGGCTCTAGGTACCGA – 3′) and Pdgf-a (5′ – GAGATACCCCGGGAGTTGAT – 3′ and 5′ – TCTTGCAAACTGCAGGAATG – 3′). Level of mRNA expression for each gene of interest was normalized to Phosphoglycerate kinase (PGK) mRNA expression using the comparative cycle time method(Meijerink et al., 2001). PGK primers were 5′ – GAGCCCATAGCTCCATGGT – 3′ and 5′ - CAGTAGCTTGGCCAGTCTTG – 3′).

Immunohistochemistry

Human tissue microarrays were obtained from the CHTN. Mouse samples were fixed in 10 % buffered formalin and embedded in paraffin. Immunohistochemistry was performed according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) using a prediluted rabbit polyclonal PDGFR-A antibody (ab15501, Abcam, Cambridge, MA).

Immunoblotting

For immunoblotting, tumor tissues were lysed in RIPA buffer containing a phosphatase inhibitor and a protease inhibitor (Sigma, St Louins, MI). The lysates were homogenized and centrifuged at 8,000g for 20 minutes. The resulting supernatants were used for immunoblot analysis. Rabbit anti-PDGFR-A antibody (#3164, Cell Signaling Technology, Beverly, MA), rabbit anti-phospho PDGFR-A (pTyr742) antibody (P8246, Sigma), rabbit anti-p44/42 MAPK antibody (#9102, Cell Signaling Technology), rabbit anti-phospho p44/42 MAPK (pThr202/pTyr204) antibody (#9101, Cell Signaling Technology), mouse anti-PKBα/Akt antibody (#610860, BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA), rabbit anti-phospho Akt (pSer473) antibody (#4060, Cell Signaling Technology), rabbit anti-PDGFR-B antibody (#3162, Cell Signaling Technology) and rabbit anti-Caspase-3 antibody (#9662, Cell Signaling Technology) were used at 1:1000. Appropriate horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies (Vectorlabs) were used at 1:5000 and chemiluminescence was detected using Western Pico substrate (Pierce Biotechnology, Rockford, IL).

Transcriptional reporter assay

Cross-species Pdgfr-a promoter sequence analysis and reporter assays were performed as detailed in Supplementary Materials and Methods.

Immunoprecipitation and immune complex tyrosine kinase assay

Control myoblast and alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma cells were lysed in RIPA buffer [20 mmol/L Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 150 mmol/L NaCl, 5 mmol/L ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA), 1 mmol/L Na3VO4, 1% NP-40, 1 mmol/L PMSF, and 0.1% aprotinin] at 4°C for 30 minutes. The lysed monolayer was scraped from plates and centrifuged at 10,000 g for 30 minutes at 4°C. The cleared supernatant was used to estimate protein content using the Bio-Rad reagent. An equal amount (100 to 500 μg) of protein from each sample was incubated with PDGFR-A antibody (#3164, Cell Signaling Technology) for 30 minutes on ice. Protein A sepharose beads were added, and the mixture was rotated at 4°C for three hours. The beads were washed three times with RIPA buffer in 2mM EDTA, twice with 50 mmol/L Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 0.5 mmol/L Na3VO4. The immunoprecipitates were then resuspended in 50 mM HEPES, pH 7.4 and 10 mM MnCl2, 20 μCi of [γ-32P]ATP and incubated at 30°C for 15 min. For PI3 kinase assay, the immunoprecipitates are resuspended in PI-3-kinase assay buffer [20 mM Tris · HCl, pH 7.5, 0.1 M NaCl, and 0.5 mM ethylene glycol-bis(β-aminoethyl ether)-N, N, N′, N′-tetraacetic acid] and 0.5 μl of phosphatidylinositol was added and incubated at 25°C for 10 min. One microliter of 1 M MgCl2 and 10 μCi of [γ-32P] ATP are added simultaneously to the reaction mixture and incubated at 25°C for another 10 min. At the end of the reaction, 5× sample buffer was added, and the labeled proteins were separated on an SDS gel.

Cell lines and primary tumor cell cultures

Mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) deficient of p53, originally generated by Dr. D.J. Kwiatkowski at Harvard Medical School, were graciously provided by Dr. Samy L. Habib. For establishment of the mouse rhabdomyosarcoma cell lines, tumor samples were minced into small fragments followed by collagenase treatment (0.5%) overnight at 4°C. The dissociated cells were incubated in DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and penicillin (100 U/ml)/streptomycin (100μg/ml) (Invitrogen) in 5% CO2 in air at 37°C. Human alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma cell lines (Rh5 and Rh30) were generously provided by the Houghton laboratory at St Jude’s Cancer Research Hospital. Human skeletal muscle cell line (SkMC) was obtained from Lonza (Basel, Switzerland).

In vitro growth inhibition assays

Mouse and human rhabdomyosarcoma cell lines were plated at 5 × 103 cells per well in 96 well plates. After 24 hours, imatinib was added to the wells. Serial dilutions were made to span the range from ineffective concentrations to maximally effective concentrations. Small interfering RNA (siRNA) against mouse Pdgfr-a was purchased from Dharmacon Research (# LQ-048730-00) (Lafayette, CO). Small interfering RNA (siRNA) against human PDGFR-A was purchased from Qiagen (# SI02659699). Transient transfection of siRNA was carried out by using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). Non-targeting siRNA (# D-001810-01, Dharmacon Research, Lafayette, CO) was used as a control. After cells were incubated with imatinib or siRNA for 72 hours, cytotoxic effects were assessed using CellTiter-Glo Luminescent Cell Viability Assay system (Promega, Madison, WI) and SpectraMax M5 luminometer (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA).

Anchorage-dependent colony formation assay

C2C12 and mouse rhabdomyosarcoma cell lines were plated at 5 × 102 cells per well in 6 well plates. After 24 hours, the indicated concentrations of imatinib or Pdgfr-a siRNA were directly added to the medium or transfected by using Lipofectamine 2000, respectively. After cells were incubated with imatinib or siRNA for 8 days, colonies were fixed with methanol, treated with Giemsa stain, and counted.

Mice

All experiments with animals were in accordance with institutional IACUC-approved protocols. Generation of the conditional knockout mouse model for alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma was previously described(Keller et al., 2004a). The mouse models show 100% penetrance of tumor development (average disease-free survival is 4.5 months in mice with p53 mutation, 4–7 months in mice with Cdkn2a mutation, unpublished data). The length, width and depth of palpable tumors were measured with Vernier calipers. Tumor volumes (cm3) were calculated from the formula (π/6) × length × width × height, assuming tumors to be spheroid. Imatinib (Novartis, Basel, Switzerland) was administrated to tumor-bearing animals at a dose of 50 mg/kg/daily by oral gavage. Goat anti-Pdgfr-a neutralizing antibody (AF1062, R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) or its matching control, normal goat IgG antibody (AB-108-C, R&D Systems), were treated at a dose of 1.25mg/kg twice a week by intraperitoneal injection.

Statistical analysis

We used dunnett adjusted t-tests for statistical significance of both expression analysis and in vitro assay. P < 0.05 is considered statistically significant. Unless otherwise specified, all data are presented as mean ± s.d..

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Frederic G. Barr (The University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine) for providing Pax3:Fkhr cDNA and Pax7:Fkhr cDNA, and Dr. Guillermina Lozano (University of Texas M. D. Anderson Cancer Center) for providing p53 cDNA. This work was funded in part by grants from NIH RO1CA 133229, the University Research Council (UTHSCSA), the Sarcoma Foundation of America, and the Amschwand Sarcoma Cancer Foundation. Animal care costs for this study were in part defrayed by a National Cancer Institute Center grant to the San Antonio Cancer Center (grant number P30 CA54174), of which C.K. is a member. We thank Dr. Sharon B. Murphy for critical reading of this manuscript, and Gary Chisholm for statistical support.

Footnotes

Supplementary Information accompanies the paper on the Oncogene website

References

- Armistead PM, Salganick J, Roh JS, Steinert DM, Patel S, Munsell M, et al. Expression of receptor tyrosine kinases and apoptotic molecules in rhabdomyosarcoma: correlation with overall survival in 105 patients. Cancer. 2007;110:2293–303. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arndt CA, Crist WM. Common musculoskeletal tumors of childhood and adolescence. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:342–52. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199907293410507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blandford MC, Barr FG, Lynch JC, Randall RL, Qualman SJ, Keller C. Rhabdomyosarcomas utilize developmental, myogenic growth factors for disease advantage: a report from the Children’s Oncology Group. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2006;46:329–38. doi: 10.1002/pbc.20466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capdeville R, Buchdunger E, Zimmermann J, Matter A. Glivec (STI571, imatinib), a rationally developed, targeted anticancer drug. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2002;1:493–502. doi: 10.1038/nrd839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choudhury GG, Grandaliano G, Jin DC, Katz MS, Abboud HE. Activation of PLC and PI 3 kinase by PDGF receptor alpha is not sufficient for mitogenesis and migration in mesangial cells. Kidney Int. 2000;57:908–17. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2000.00907.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cools J, DeAngelo DJ, Gotlib J, Stover EH, Legare RD, Cortes J, et al. A tyrosine kinase created by fusion of the PDGFRA and FIP1L1 genes as a therapeutic target of imatinib in idiopathic hypereosinophilic syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:1201–14. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa025217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devare SG, Reddy EP, Law JD, Robbins KC, Aaronson SA. Nucleotide sequence of the simian sarcoma virus genome: demonstration that its acquired cellular sequences encode the transforming gene product p28sis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1983;80:731–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.80.3.731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engelman JA, Zejnullahu K, Mitsudomi T, Song Y, Hyland C, Park JO, et al. MET amplification leads to gefitinib resistance in lung cancer by activating ERBB3 signaling. Science. 2007;316:1039–43. doi: 10.1126/science.1141478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein JA, Song B, Lakkis M, Wang C. Tumor-specific PAX3-FKHR transcription factor, but not PAX3, activates the platelet-derived growth factor alpha receptor. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:4118–30. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.7.4118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinrich MC, Corless CL, Demetri GD, Blanke CD, von Mehren M, Joensuu H, et al. Kinase mutations and imatinib response in patients with metastatic gastrointestinal stromal tumor. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:4342–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.04.190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heldin CH, Westermark B. Mechanism of action and in vivo role of platelet-derived growth factor. Physiol Rev. 1999;79:1283–316. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1999.79.4.1283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jonkers J, Berns A. Conditional mouse models of sporadic cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2002;2:251–65. doi: 10.1038/nrc777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller C, Arenkiel BR, Coffin CM, El-Bardeesy N, DePinho RA, Capecchi MR. Alveolar rhabdomyosarcomas in conditional Pax3:Fkhr mice: cooperativity of Ink4a/ARF and Trp53 loss of function. Genes Dev. 2004a;18:2614–26. doi: 10.1101/gad.1244004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller C, Hansen MS, Coffin CM, Capecchi MR. Pax3:Fkhr interferes with embryonic Pax3 and Pax7 function: implications for alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma cell of origin. Genes Dev. 2004b;18:2608–13. doi: 10.1101/gad.1243904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller P, Payne JL, Tremml G, Greer PA, Gaboli M, Pandolfi PP, et al. FES-Cre targets phosphatidylinositol glycan class A (PIGA) inactivation to hematopoietic stem cells in the bone marrow. J Exp Med. 2001;194:581–9. doi: 10.1084/jem.194.5.581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacDonald TJ, Brown KM, LaFleur B, Peterson K, Lawlor C, Chen Y, et al. Expression profiling of medulloblastoma: PDGFRA and the RAS/MAPK pathway as therapeutic targets for metastatic disease. Nat Genet. 2001;29:143–52. doi: 10.1038/ng731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matei D, Emerson RE, Lai YC, Baldridge LA, Rao J, Yiannoutsos C, et al. Autocrine activation of PDGFRalpha promotes the progression of ovarian cancer. Oncogene. 2006;25:2060–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehrotra M, Krane SM, Walters K, Pilbeam C. Differential regulation of platelet-derived growth factor stimulated migration and proliferation in osteoblastic cells. J Cell Biochem. 2004;93:741–52. doi: 10.1002/jcb.20138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meijerink J, Mandigers C, van de Locht L, Tonnissen E, Goodsaid F, Raemaekers J. A novel method to compensate for different amplification efficiencies between patient DNA samples in quantitative real-time PCR. J Mol Diagn. 2001;3:55–61. doi: 10.1016/S1525-1578(10)60652-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pani L, Horal M, Loeken MR. Rescue of neural tube defects in Pax-3-deficient embryos by p53 loss of function: implications for Pax-3- dependent development and tumorigenesis. Genes Dev. 2002;16:676–80. doi: 10.1101/gad.969302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider L, Clement CA, Teilmann SC, Pazour GJ, Hoffmann EK, Satir P, et al. PDGFRalphaalpha signaling is regulated through the primary cilium in fibroblasts. Curr Biol. 2005;15:1861–6. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stover EH, Chen J, Folens C, Lee BH, Mentens N, Marynen P, et al. Activation of FIP1L1-PDGFRalpha requires disruption of the juxtamembrane domain of PDGFRalpha and is FIP1L1-independent. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:8078–83. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0601192103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stover EH, Chen J, Lee BH, Cools J, McDowell E, Adelsperger J, et al. The small molecule tyrosine kinase inhibitor AMN107 inhibits TEL-PDGFRbeta and FIP1L1-PDGFRalpha in vitro and in vivo. Blood. 2005;106:3206–13. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-05-1932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi Y, Oda Y, Kawaguchi K, Tamiya S, Yamamoto H, Suita S, et al. Altered expression and molecular abnormalities of cell-cycle-regulatory proteins in rhabdomyosarcoma. Mod Pathol. 2004;17:660–9. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3800101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Underwood TJ, Amin J, Lillycrop KA, Blaydes JP. Dissection of the functional interaction between p53 and the embryonic proto-oncoprotein PAX3. FEBS Lett. 2007;581:5831–5. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2007.11.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.