Abstract

JOHNSON, Z.V., A.A. REVIS, M.A. BURDICK, AND J.S. RHODES. A similar pattern of neuronal Fos activation in 10 brain regions following exposure to reward- or aversion-associated contextual cues in mice. PHYSIOL BEHAV 00(0) 000–000, 2009 — Relapse triggered by drug-paired cues is a major obstacle for successful treatment of drug abuse. Patterns of brain activation induced by drug-paired cues have been identified in human and animal models, but lack of specificity poses a serious problem for craving or relapse interpretations. The goal of this study was to compare brain responses to contextual cues paired with a rewarding versus an aversive stimulus in a mouse model to test the hypothesis that different patterns of brain activation can be detected. Mice were trained to associate a common environmental context with an intraperitoneal injection of saline, lithium choride or cocaine. After measuring each animal for conditioned place preference or aversion, mice were re-exposed to the context (CS+ or CS−) in absence of the reinforcer to analyze patterns of Fos expression in 10 brain regions chosen from previous literature. Levels of Fos in the cingulate cortex, paraventricular thalamic nucleus, paraventricular hypothalamic nucleus, and dentate gyrus differed in CS+ versus CS− groups, but the direction of the differences were the same for both lithium chloride (LiCl) and cocaine reinforcers. In the cingulate cortex, Fos was positively correlated with degree of place preference for cocaine or aversion to LiCl whereas in the periaqueductal gray the relationship was positive for LiCl and negative for cocaine. Results confirm Fos responses to reward- or aversion-paired cues are similar but specificity is detectable. Future studies are needed to comprehensively establish neuroanatomical specificity in conditioned responses to drugs as compared to other reinforcers.

Keywords: cocaine, lithium chloride, conditioned place preference, Fos, reward, aversion, natural reward circuit, craving, relapse, CPP, CPA

1. Introduction

One of the greatest obstacles for treatment of drug abuse is relapse. Even after long periods of abstinence, a small priming dose of the drug, stressful life events or exposure to environmental cues that were previously paired with drug use can trigger relapse [1]. Drug-paired cues are particularly problematic because they are ubiquitous and difficult to avoid. Finding a treatment that can diminish relapse-provoking responses to drug-paired cues is critical for interrupting the devastating cycle of abuse, withdrawal, abstinence and relapse.

A large literature has examined brain responses to drug-paired cues. Regions of the brain (e.g., nucleus accumbens, cingulate cortex) have been identified that become “activated” (as measured by fMRI or PET) when human subjects with a prior history of drug abuse are shown images of drug paraphernalia or people taking drugs [2–6]. The usual interpretation is that the brain activation patterns reflect an emotional state of craving but a fundamental problem with this interpretation is the lack of specificity in the findings. For example, similar brain regions become activated when subjects are shown sexually explicit videos [7] or photographs of loved ones that have passed away [8]. Increased attention or arousal is a major confounding variable in many of these studies. As long as the stimulus is salient, regardless of whether it is aversive, rewarding, sad, or sexually arousing, a robust pattern of brain activation is elicited by the arousal alone, and that pattern is common across many stimuli.

Laboratory rodent models have the same problems with specificity. We and others have found that brain regions responsive to cues paired with methamphetamine and cocaine are similar to those involved in motivation for wheel running behavior and reinforcement for food [9–11]. The favored interpretation is that a final common pathway in the natural reward circuit has been recruited in each case, but another interpretation is that these overlapping patterns merely reflect heightened attention or arousal due to the salience of the experience. The observation that brain responses to contextual cues paired with aversive stimuli display remarkable similarity to reward supports the latter hypothesis [12,13].

It has been elegantly demonstrated in rats using voltammetry and other electrophysiological techniques that chemical signaling in the nucleus accumbens differs when rats are given quinine (bitter) versus sucrose (sweet) solutions to taste in their mouths [14]. Moreover, different populations of cells in the nucleus accumbens are recruited during operant responding for sucrose versus cocaine [15]. On the other hand, similar populations of cells are responsive to cues paired with sucrose versus quinine in a strictly Pavlovian experiment where exposure to conditioned cues is not contingent on any behavioral response and occurs in absence of the reinforcer [16]. Moreover, a recent study showed that single neurons in the orbitofrontal cortex of monkeys responded similarly to visual cues predicting an aversive stimulus (a puff of air) or a rewarding stimulus (liquid reward) [17]. Hence, it is not clear how the micro-circuit differences in dopamine release and cell firing populations in the nucleus accumbens translate into learning about the appetitive value of the stimuli. In fact, whether learning about rewarding versus aversive stimuli can be biologically distinguished is still a matter of debate [18,19]. This is a very important issue because if the neurological features critical for conditioned behavioral responses to drugs are not different than for natural rewards or aversive stimuli, then it is not clear how to establish a research program without results generalizing to all forms of motivation or emotional reactions.

One method widely used in laboratory rodent models to identify brain regions or circuits involved in learned behaviors is immunohistochemical detection of Fos [20–23]. Fos is the protein product of the immediate early gene c-fos. Presence of high levels of Fos in a neuron indicate a high level of transcriptional regulation [24]. Because Fos signaling has a discrete time course with peak levels of protein occurring approximately 90 minutes after a stimulus, it can be used to identify cells that are undergoing genomic changes in response to a specific stimulus (e.g., exposure to an environmental context associated with the subjective effects of a drug) [9,11,25]. Fos contributes to the initiation and coordination of molecular cascades and cellular events required for neuroplasticity, and through this mechanism it has an established role in learning and memory [23,24,26].

Most previous studies in rodents that examined conditioned Fos responses to contextual cues focused on a single type of unconditioned stimulus (e.g., cocaine, food, or foot shock) as compared to a neutral stimulus (e.g., saline injection, water, or no shock) [9,11,13,27–35]. Substantial overlap in the circuits has been identified mostly by review and comparison among these individual studies [9,12]. Surprisingly few studies have been conducted where the goal is to compare patterns of Fos activation in response to cues paired with stimuli of opposing appetitive value. Therefore, the goal of this project was to carry out such a study using mice as a model organism. We predicted that we would find different patterns of neuronal Fos activation in animals exposed to a common environment, depending on whether the environment was previously associated with an aversive or rewarding subjective experience. Our prediction was based on the hypothesis that cue-induced patterns of Fos activation would reflect differential learning about the appetitive value of the stimuli.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Subjects and husbandry

A total of 40 genetically variable, male, hsd:ICR mice (Harlan Sprague Dawley, Indianapolis, IN) were used in this study. Subjects arrived at the Beckman Institute Animal Facility at 5 weeks of age and were acclimated for 2 weeks prior to testing. The first week, mice were housed in groups of 4 but then were transferred to individual cages for the rest of the study. Animals were housed in standard polycarbonate shoebox cages with Bed-o-Cob™ bedding. Rooms were controlled for temperature (21±1 °C) and light cycle (12:12 L:D). A reverse light/dark cycle was used, with lights on at 2200 h and lights off at 1000 h Central Standard Time. Red incandescent lamps were left on continuously so that investigators could handle mice during dark phases. Animals had continuous access to food (Harlan Teklad 7012) and water ad libitum except when in the conditioning boxes. The Beckman Animal Facility is AAALAC approved. All procedures were approved by the University of Illinois Animal Care and Use Committee and adhered to NIH guidelines.

2.2. Drugs

Cocaine hydrochloride (Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) was dissolved in 0.9% saline and was administered via intraperitoneal (i.p.) injections at a dose of 20 mg/kg. It was prepared according to the salt, not the base form, and was administered in a volume of 10 ml/kg. Lithium chloride (Acros Organics, Morris Plains, NJ) was administered in the same fashion at a dose of 130 mg/kg. Doses were chosen from the literature [9,36].

2.3. Video Tracking

Distance traveled in the apparatus and the location of the mouse within the place conditioning chambers were measured by TopScan (Clever Sys Inc, Vienna, VA) video tracking software.

2.4. Place Conditioning Chambers

Twenty place conditioning chambers were constructed following the design of Cunningham et al. [37] with some modification to allow video tracking from above [9]. Each chamber consisted of a textured floor base, surrounded by a black acrylic box (30 cm × 15 cm × 15 cm) with a removable, clear plastic top. The floor bases were interchangeable and included three types: hole, grid, and hole/grid. The hole floor texture consisted of perforated 15-gauge stainless steel with 6.4 mm round holes on 9.5 mm staggered centers. The grid floor consisted of 2.3 mm stainless steel rods mounted 6.4 mm apart. The hole/grid floor consisted of a half grid and half hole textures which together had the same dimensions as the single textured floors. All three floor types were mounted on a black acrylic frame (33 cm × 18 cm × 5 cm) with 4 holes (1 cm diameter) drilled in the sides for ventilation.

The combination of floor types (hole/grid) was chosen because it is “unbiased” for DBA/2J mice in Cunningham et al. [37]. However, in previous studies using our modified version with hsd:ICR mice, we have found a slight preference for the grid versus the hole [9]. Note that this does not impact the statistical analysis to detect conditioned place preference or aversion [see section 2.9, also refer to 37].

2.5. Conditioned place preference or aversion

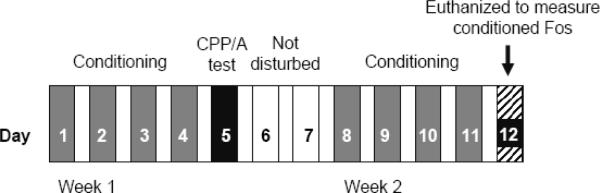

Mice were divided equally into two groups (n=20 each). The only difference between the two groups was whether animals received daily i.p. injections of lithium chloride (LiCl) (130 mg/kg) or cocaine (20 mg/kg) during the conditioning phases of the experiment (Figure 1). The experiment was conducted in two batches and each batch included half cocaine and half LiCl cohorts. Animals that received LiCl never received cocaine and vice versa.

Figure 1.

Experimental design. The experiment proceeded in 2 weeks. During the first week, mice received 4 conditioning trials with cocaine (20 mg/kg) or LiCl (130 mg/kg). This was implemented by giving mice 2 injections per day separated by 4 hours (either saline or the unconditioned stimulus) for 4 days. Each trial lasted 30 min. On day 5, mice were tested for conditioned place preference or aversion. The conditioning procedure was repeated the following week. On the final day, all mice received a saline injection and were placed onto a texture paired with cocaine, LiCl or saline for 90 min. Mice were then immediately perfused transcardially with 4% paraformaldehyde for immunohistochemical detection of Fos.

On the first day of conditioning, at 1100 hrs, 1 hr after lights shut off, animals were given an i.p. injection of either saline, LiCl (130 mg/kg) or cocaine (20 mg/kg), and then placed into a conditioning chamber with either a grid or a hole floor texture for 30 min. The procedure was repeated at 1500 h except animals received the alternate injection and were placed on the alternate floor texture. For example, if an animal received cocaine on grid at 1100 hrs, then it received saline on hole at 1500 hrs on that day. The entire procedure was repeated for 4 consecutive days. The order of whether an animal received the unconditioned stimulus (cocaine or LiCl) at 1100 or 1500 was alternated each day. Equal numbers of animals were conditioned to the hole (CS+ hole group) or the grid texture (CS+ grid group), and the treatments were assigned in a completely counterbalanced fashion. At 1100 hrs on day 5, all animals received a saline injection and were placed in chambers with half hole and half grid textured floors for 30 minutes to determine their preference or aversion to either floor texture.

2.6. Conditioned Neuronal Activation

Following two days when animals remained undisturbed, the procedure described above (section 2.5) was repeated in the same mice, except on the test day the animals were placed into the apparatus containing a floor with entirely grid or hole textures (see Figure 1). Half the animals were placed onto the texture where they had previously experienced the unconditioned stimulus (cocaine or LiCl injection), and the other half where they had experienced only the saline injection. Note that animals were NOT given a choice of floor-types during this test to control duration of exposure on the reward-paired context following Zombeck et al. [9]. This test lasted 90 min, instead of 30 min, after which animals were euthanized and processed for immunohistochemical detection of Fos (see below).

2.7. Immunohistochemistry

Following Zombeck et al. [9], mice were decapitated and their brains were immediately placed into 5% acrolein in phosphate buffered saline (PBS) and left overnight. Brains were then transferred to 30% sucrose in PBS for at least two days and sectioned (40 μm thick) with a cryostat. Brain sections were stored in tissue cryoprotectant (PBS containing 30% sucrose w/v, 30% ethylene glycol v/v, and 10% polyvinylpryrrolidine w/v) at −20°C in a 24 well plate. Free-floating sections were pretreated with sodium borohydride (100 mg per 20 ml PBS) for 30 minutes at room temperature, washed in PBS containing 0.2% v/v Triton X-100 (PBS-X) and blocked with 6% v/v Normal Goat Serum (NGS) for 1 hour at room temperature. Sections were then incubated in monoclonal primary antibody against mouse Fos made in rabbit (Calbiochem, San Diego, CA) at a dilution of 1:20,000 in PBS-X containing 2% NGS for 48 h at 5°C. Sections were subsequently washed in PBS-X and incubated in secondary biotinylated antibody against rabbit immunoglobulin made in goat (Vector Labs, Burlingame, CA) at a dilution of 1:500 in PBS-X with 2% NGS for 90 minutes at room temperature. The antibody complex was visualized using the peroxidase method (ABC system, Vector Labs, Burlingame, CA; 37 μl A, 37 μl B in 15 ml PBS-X) with diaminobenzidine (DAB) as chromogen, enhanced with 0.008% w/v nickel chloride (Sigma, St. Louis, MO). Sections were mounted onto subbed slides (pretreated with 1% w/v pig skin gelatin and 0.05% w/v chromium potassium sulfate) and allowed to dry. After drying, sections were dehydrated in the following sequence: 70% ethanol for 5 min, 95% ethanol for 5 min, fresh 100% ethanol for 10 min, xylenes for 15 min, and finally fresh xylenes for 15 min. Slides were coverslipped with Permount (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) while still partially wet with xylenes.

2.8. Image Analysis

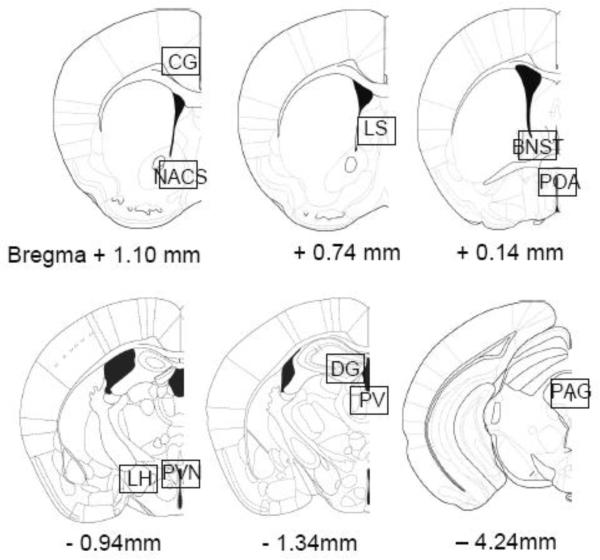

Microscopic images (100× total magnification) of brain sections were taken using a Zeiss Axiocam video camera mounted on a Zeiss bright field light microscope interfaced to a personal computer. Three photographs from three alternate sections (separated by 40 micron intervals) were taken for each brain region. Fos-positive nuclei were automatically counted within a frame (1 × 0.63 mm) placed at the approximate locations shown in Figure 2 following Paxinos and Franklin [38]. This was implemented using ImageJ software. A threshold was applied to remove the background, and the remaining particles were automatically counted if they fell within a specified size range. If brain regions were smaller than this frame, as was the case for the dentate gyrus and the paraventricular hypothalamic nucleus, they were outlined by hand and only Fos positive nuclei within the boundaries were counted. Counting was done unilaterally for each brain region. An average count across all three sections for each brain region was used for analysis. Given that the only difference between treatment groups was whether they were placed on a grid or hole texture, we assumed differences between groups could not result from shrinkage of tissue, or different size of nuclei. Therefore, stereological corrections were not used.

Figure 2.

Locations where Fos positive cells were counted. The boxes were 1 × 0.63 mm and are shown roughly to scale. The figures were reprinted from Paxinos and Franklin, The Mouse Brain in Stereotaxic Coordinates (second edition), Figures 22, 25, 30, 39, 42, and 66, Copyright 2001, with permission from Elsevier. As noted, for the paraventricular hypothalamic nucleus and the dentate gyrus, the nucleus was outlined by hand and particles were counted only within the outlined structures. Legend: CG=cingulate cortex, NACS=nucleus accumbens shell, LS=lateral septum, BNST=bed nucleus of the stria terminalis, POA=preoptic area, LH=lateral hypothalamus, PVN=paraventricular hypothalamic nucleus, PV=paraventricular thalamic nucleus, DG=dentate gyrus, PAG=periaqueductal gray.

2.9. Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using SAS (version 9.1) or R (version 2.7.2). Locomotor activity during the conditioning trials was analyzed by 2-way repeated measures ANOVA with treatment (3 levels, saline, 20 mg/kg cocaine, or 130 mg/kg LiCl) and day (8 levels) entered as the two factors, and animal entered as a random effect. The trials at 1100 hrs and 1500 hrs were not significantly different from each other and therefore were combined for each day. The saline groups within the cocaine and LiCl cohorts were also not different from each other and so were combined. Locomotor activity during the CPP/A test was analyzed using an unpaired t-test where the two groups were the animals previously treated with LiCl versus cocaine. Locomotor activity over 90 minutes during the final test was analyzed using a two way ANOVA with treatment history (cocaine or LiCl) and conditioned stimulus (CS+ or CS−) entered as the two factors.

Conditioned place preference or aversion was analyzed two ways. First, the cocaine and LiCl cohorts were analyzed separately using standard methods described by Cunningham et al. [37]. Within each cohort, the duration spent on the hole texture was compared between the CS+ hole and CS+ grid groups [37]. Second, both cohorts were combined and analyzed by a 2-way ANOVA. Duration spent on the hole texture was analyzed as a function of treatment history (cocaine or LiCl) and conditioned stimulus (CS+ hole versus CS+ grid). However, the CS+ hole and CS+ grid groups were switched for LiCl so that the magnitude of preference could be compared to the magnitude of aversion on the same scale.

Numbers of Fos positive cells in the different brain regions were analyzed using a linear model that included batch (see section 2.5, the experiment was conducted in two separate batches), treatment group (LiCl or cocaine), conditioned stimulus (CS+ or CS−), and the interaction between treatment group and conditioned stimulus as factors. In addition, the correlation between the strength of CPP/A during the first week and the number of Fos positive cells measured in the second week was analyzed for animals exposed to the CS+ texture on the final test. In this analysis, the strength of CPP/A was measured as the time spent on the CS+ or CS− texture for cocaine or LiCl treated animals, respectively. The correlation was extracted from a linear model that included batch and treatment group (LiCl vs. cocaine) as factors, in addition to the strength of CPP/A, entered as a continuous predictor, and the interaction between the strength of CPP/A and treatment group. Because multiple tests were conducted analyzing numbers of Fos positive cells in 10 different regions using two separate analyses, we estimated the global experiment-wise false discovery rate using Qvalue software and adjusted the cut off p-value so that the false discovery rate was controlled at 5% [39].

3. Results

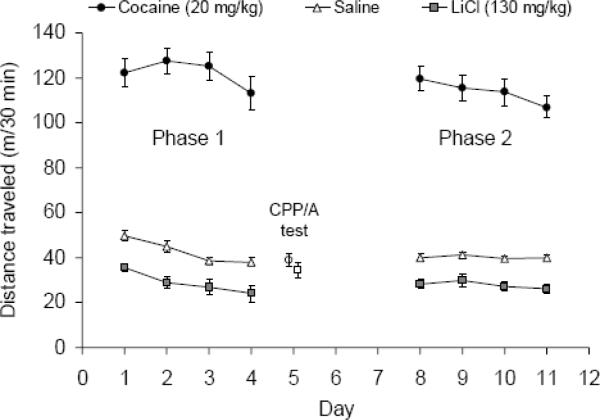

3.1. Locomotor activity

Cocaine significantly increased locomotor activity, whereas LiCl decreased activity relative to the saline groups (see Figure 3; p<0.0001). The level of locomotor activity decreased slightly as the days progressed in all the groups (p<0.0001; the interaction between day and group was not significant). No significant differences in locomotor activity were observed between the groups on the conditioned place preference test or during the final test when animals were placed into the CS+ or CS− texture for 90 minutes (the final test consisted of batch 1 only because the locomotor activity data on the final day in batch 2 was lost due to computer malfunction).

Figure 3.

Locomotor activity during conditioning and CPP/A testing. Mean distance (m) ± SE traveled over the 30 minute trials plotted separately for animals that received saline, cocaine (20 mg/kg) or LiCl (130 mg/kg). During the CPP/A test, all mice received saline, and the cocaine versus LiCl groups are shown separately as an open circle, or open square, respectively. The sample sizes were n=20/group except for saline during the conditioning days when n=40 because the saline treated animals from both the cocaine and LiCl groups were combined.

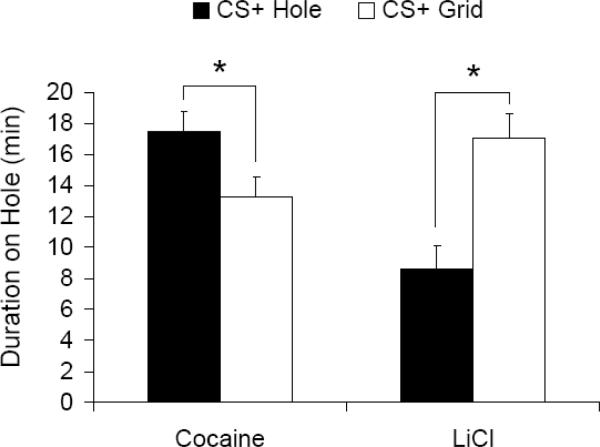

3.2. CPP

Animals showed significant conditioned place preference for cocaine (t18=2.4, p=0.03) and significant aversion to LiCl (t18=3.9, p=0.001) (see Figure 4). The magnitude of preference for cocaine as measured by the absolute value of the difference between CS+ hole versus CS+ grid groups (see Figure 4) was slightly weaker than aversion to LiCl, but this difference was not statistically significant.

Figure 4.

Conditioned place preference for cocaine and aversion to LiCl. Mean duration (min) ± SE spent on the hole texture plotted separately for groups receiving the unconditioned stimulus (i.e., cocaine or LiCl) on the hole (CS+ Hole) or grid (CS+ Grid) textures. The stars indicates that the CS+ Hole versus CS+ Grid groups were statistically different from each other at p<0.05 for both cocaine and LiCl.

3.3. Conditioned neuronal activation

The global false discovery rate for the Fos analyses was estimated to be 5.3%, and the cut off p-value to control the false discovery rate at 5% was estimated to be p less than or equal to 0.03. Therefore, in the following analyses, we considered a p-value less than or equal to 0.03 as statistically significant.

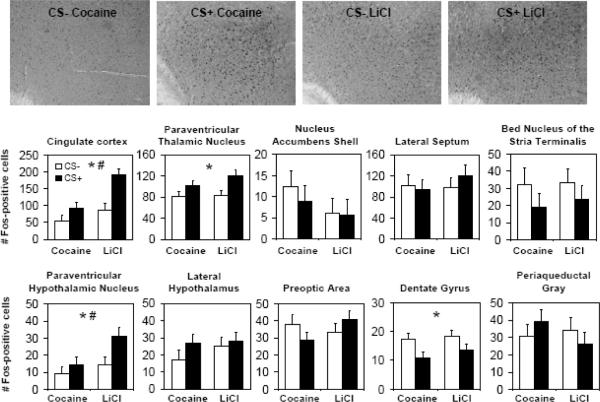

Exposure to the conditioned stimulus significantly altered Fos expression, but the changes were similar whether the conditioned stimulus was paired with cocaine or LiCl (see Figure 5). In the cingulate cortex (CG) and paraventricular hypothalamic nucleus (PVN), levels of Fos expression were higher, overall, in animals previously treated with LiCl as compared to cocaine (for CG, F1,31=11.8, p=0.002; for PVN, F1,29=5.6, p=0.03), and higher in the CS+ cohorts as compared to CS− (for CG, F1,31=14.0, p=0.0007; for PVN, F1,29=5.7, p=0.02). The effect of the conditioned stimulus was slightly greater in the LiCl group than cocaine but this difference was not statistically significant (for CG, F1,31=3.1, p=0.09; for PVN, F1,29=1.5, p=0.23). In the paraventricular thalamic nucleus, the CS+ groups showed significantly elevated Fos as compared to CS− (F1,32=10.4, p=0.003), but no main effect of treatment (cocaine vs. LiCl) or interaction between treatment and exposure to the conditioned stimulus was detected. In the dentate gyrus, the CS+ groups showed significantly reduced Fos as compared to CS− (F1,30=7.2, p=0.01), but no main effect of treatment (cocaine vs. LiCl) or interaction between treatment and exposure to the conditioned stimulus was detected.

Figure 5.

Neuronal activation following exposure to cocaine or LiCl-associated contextual cues. Top, representative sections of the cingulate cortex stained for Fos in each of the 4 groups (CS− cocaine, CS+ cocaine, CS− LiCl, CS+ LiCl). Bottom, bar graphs showing mean number of Fos positive cells ± SE per group for each brain region. The stars indicate significant main effect of the conditioned stimulus (CS− versus CS+), and the number sign indicates significant main effect of prior treatment with the unconditioned stimulus (LiCl versus cocaine) in the 2-way ANOVA. The interaction was not significant for any brain region.

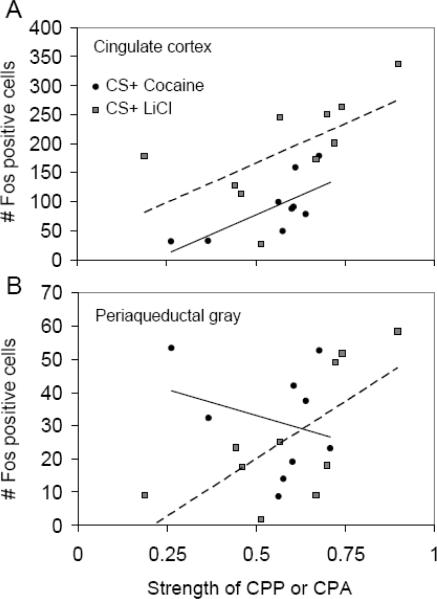

Another interesting result was observed for the cingulate cortex and periaqueductal gray (Fig. 6). In the cingulate cortex, a significant positive correlation was observed between the strength of conditioned place preference or aversion during the first week, and the number of Fos positive cells in animals exposed to the CS+ in the second week (F1,14=11.4, p=0.005). Within the cocaine-treated animals, the correlation was r = 0.72 (F1,7=7.7, p=0.03) and within LiCl mice it was 0.62 (F1,8=4.9 p=0.06). However, for a given level of preference/aversion, the CS+ LiCl mice showed greater Fos than CS+ cocaine (F1,14=11.8, p=0.004). The interaction was not significant (i.e., the slopes of the regression lines were similar, F1,14=0.13, p=0.73; see Figure 6A).

Figure 6.

Correlation between the strength of conditioned place preference or aversion and the number of Fos positive cells. Panel A shows the data for the cingulate cortex and B for the periaqueductal gray. Both graphs share the same x-axis. For CS+ cocaine animals, the strength of preference on the x-axis represents the proportion time spent on the CS+ side during the CPP/A test. For CS+ LiCl animals, the strength of aversion represents the proportion time spent on the CS− side during the CPP/A test. Only animals exposed to the conditioned stimulus (CS+) on the final day are shown (i.e., animals exposed to CS− are not included in this analysis). The simple linear regression lines are drawn separately for cocaine and LiCl groups.

In the periaqueductal gray, a positive correlation (r=0.70; F1,8=7.5 p=0.03) was detected between the strength of aversion to LiCl and the number of Fos cells, whereas a weak negative correlation (r=−0.28; F1,7=0.6 p=0.46) was observed between the strength of preference for cocaine and the number of Fos cells. In the overall analysis, the interaction between the continuous place preference/aversion measure and the unconditioned stimulus (LiCl vs. cocaine) was significant (F1,14=5.7, p=0.03), but the main effects were not (CPP/A measure, F1,14=1.0, p=0.33, unconditioned stimulus, F1,14=1.6, p=0.22) (see Figure 6B). No other brain regions sampled besides the cingulate cortex and periaqueductal gray showed significant correlations between Fos and strength of conditioned place preference or aversion.

4. Discussion

It is still a matter of debate as to whether learning about rewarding versus aversive stimuli can be biologically distinguished at the level of brain physiology [18,19]. In the current study, the behavioral data show that the animals learned a different appetitive value associated with the context depending on whether it was paired with LiCl or cocaine (Fig. 4) [40], but this was not clearly reflected in the brain activation patterns (Fig. 5). Overall, Figure 5 shows a remarkable similarity in the changes in Fos between CS+ versus CS− for the lithium choride and the cocaine groups. In all cases where CS+ and CS− were significantly different (cingulate cortex, paraventricular thalamic nucleus, paraventricular hypothalamic nucleus, and dentate gyrus), the direction of the difference for both LiCl and cocaine was the same. One interpretation of these results is that the similar Fos responses between cocaine and LiCl conditions reflects a large overlap in the brain circuits involved in attention, arousal, or learning common to both conditions. An alternative interpretation is that even though the total numbers of Fos-positive cells within brain regions were similar, Fos may have occurred in different cell populations (e.g., glutamate cells versus GABA) between each condition. This is an important alternative that should be tested in future studies. Different subpopulations of neurons within the regions could be distinguished based on anatomy of the cells, double labeling with cell-type specific markers, or by sampling more specific locations in the brain. In addition, it is possible that other protein markers, such as Arc, or zif268 could result in different patterns and distinctions between the conditions for LiCl versus cocaine. These will be the topic of future investigations.

The one exception to the overall common pattern of Fos response between the cocaine and LiCl groups was in the periaqueductal gray where the relationship between the number of Fos positive cells and the magnitude of place preference or aversion was significantly different depending on whether LiCl or cocaine was used as the reinforcer (Fig. 6B). This result for the periaqueductal gray is consistent with the literature [41,42] and is promising because it suggests that analyzing global patterns of Fos (without distinguishing cell populations) can detect differences in learning about aversive versus rewarding experiences.

The behavioral results shown in Figure 4 demonstrate that the animals learned the intended subjective direction of the association [40]. Mice significantly avoided the textures when they were paired with LiCl and preferred the textures when they were associated with cocaine. The magnitude of the avoidance behavior was not significantly different than the magnitude of preference suggesting that the salience of the unconditioned stimuli were similar and that the animals learned Pavlovian associations to both stimuli with similar strength. Although not significant, the trend was slightly stronger aversion to a texture when it was paired with LiCl than preference for that texture when it was paired with cocaine (Fig. 4). This is important for interpreting the Fos results shown in Figure 5. Slightly (but not significantly) greater increases in Fos were observed in CS+ versus CS− groups in the cingulate cortex, paraventricular thalamic nucleus and paraventricular hypothalamic nucleus in the LiCl group as compared to cocaine (Fig. 5). This is consistent with the idea that brain activation patterns in these regions reflected the strength of the association rather than the appetitive value attributed to the context.

The results of the correlation analysis provided further evidence that Fos responses in the cingulate cortex is related to the strength of preference or aversion, but does not distinguish appetitive value (Fig. 6A). In the cingulate cortex, numbers of Fos positive cells were positively correlated with the strength of place preference for cocaine or place aversion to LiCl, and the slopes of the relationship were approximately the same (i.e., the regression lines were parallel in Fig. 6A). One possible explanation is that Fos activation in this region merely reflects level of attention or arousal in response to the stimulus [11]. Alternatively, as described above, it is possible that different cell types (e.g., glutamate vs. GABA) in the cingulate cortex display Fos in LiCl vs. cocaine conditions. Under this interpretation, functionally meaningful differences could underlie similar Fos responses.

It is important to note that in the correlation analysis (Fig 6A), although Fos levels in the cingulate cortex were higher overall in the group exposed to LiCl-paired cues as compared to cocaine-paired cues (i.e., the regression line for LiCl was above the line for cocaine in Figure 6A), that difference is unlikely an effect of the conditioned stimulus because Fos levels were also higher in LiCl- versus cocaine-treated animals exposed to the saline-paired cues (Fig. 5, cingulate cortex). Hence, the additional Fos in this region appears to be the result of the chronic treatment with LiCl rather than an effect of the contextual cues.

A previous study used a design similar to ours to identify patterns of Fos activation induced by contextual cues paired with yohimbine, which was considered an aversive, anxiety provoking drug [12]. In that study, levels of Fos in the cingulate cortex were not significantly greater in rats exposed to the yohimbine-paired versus saline-paired cues, although the trend was in that direction. The authors concluded that the cingulate cortex and other regions in the frontal cortex might be preferentially activated by drug-paired cues as compared to aversion-paired cues. However, the results from this and other studies examining Fos responses to aversive stimuli do not support this general conclusion [13,43]. The strength of aversive conditioning with yohimbine was not measured using a behavioral assay in the study, and so it is possible that yohimbine was simply a weaker unconditioned stimulus as compared to the drugs to which it was being compared [12].

The Fos results shown in Figure 5 are generally consistent with the literature. Increased Fos in CS+ versus CS− in the cingulate cortex, paraventricular thalamic nucleus and paraventricular hypothalamic nucleus was observed in previous studies where cocaine, methamphetamine, nicotine, food or a foot shock was used as the unconditioned stimulus [9,13,29,34]. The only other brain area that showed a significant difference between CS+ and CS− was the dentate gyrus. Reduced Fos in the dentate gyrus in response to CS+ was not observed in our previous study using a nearly identical design for cocaine [9]. Hence, the explanation for this difference is not clear.

Results for the nucleus accumbens showing similar levels of Fos in CS+ and CS− is consistent with some studies where cocaine was used as the reinforcer [9,29] but not others [11,28,30]. One important variable is the comparison (CS−) group used in the experimental design. In this study and Zombeck et al. [9] the CS+ and CS− contexts were very similar. The only difference was the texture of the floor (hole or grid). In Rhodes et al. [11] and Franklin and Druhan [28], CS+ and CS− environments were the home cage versus the test chamber, hence there were many cues to distinguish the two contexts.

The correlation between the strength of conditioned place aversion to lithium choride and numbers of Fos positive cells in the periaqueductal gray (dashed line in Fig. 6B) is consistent with the literature [41,42,44,45]. In combination with studies that have identified microcircuit differences in chemical and electrical signaling in the nucleus accumbens in response to aversive versus rewarding stimuli [14,16], the Fos studies demonstrate that macrocircuit differences in patterns of brain activation can also be detected.

In this model, even though we administered cocaine repeatedly to animals over days and measured their locomotor activity, we observed no evidence for locomotor sensitization (Fig. 3) or conditioned changes in locomotor activity on the final test. This replicates a previously published result using a similar procedure from our lab [9]. Sensitization and conditioned locomotor responses in mice are typically induced using lower doses (e.g., 10 mg/kg) and with an intermittent schedule of administration (e.g., every other day, or several day incubation periods) as opposed to daily administration [46,47].

In summary, results confirm that exposing mice to contextual cues paired with a rewarding or an aversive experience induces similar patterns of Fos activation in 10 brain regions chosen from the literature. Future double labeling experiments are needed to determine the extent to which different types of cells are recruited in the overall similar Fos responses. On the other hand, the Fos analysis was sensitive enough to detect subtle differences in key brain areas such as the periaqueductal gray where Fos levels were differentially correlated with the strength of aversion to LiCl versus preference for cocaine. More studies are needed to comprehensively characterize specificity in the neural physiology underlying differential learning about rewards versus aversive experiences. This requires additional experiments using different types of aversive and rewarding stimuli, a larger sample of brain regions, and other immediate early gene (IEG) protein markers such as ARC, zif268 in addition to co-labeling studies to identify phenotypes (e.g., GABA, glutamate) of the IEG-positive cells.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dack Shearer, Reid McClure, Donnell Parker, Holly Fairfield, Eric Bialeschki, and Sheri Weidenburner for animal care. This work was supported by grants from National Institutes of Health, MH083807 and DA027487.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- [1].Self DW. Neural substrates of drug craving and relapse in drug addiction. Ann Med. 1998;30:379–89. doi: 10.3109/07853899809029938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Childress AR, Mozley PD, McElgin W, Fitzgerald J, Reivich M, O'Brien CP. Limbic activation during cue-induced cocaine craving. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156:11–8. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.1.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Kilts CD, Gross RE, Ely TD, Drexler KP. The neural correlates of cue-induced craving in cocaine-dependent women. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161:233–41. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.2.233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Tapert SF, Cheung EH, Brown GG, Frank LR, Paulus MP, Schweinsburg AD, Meloy MJ, Brown SA. Neural response to alcohol stimuli in adolescents with alcohol use disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60:727–35. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.7.727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Kosten TR, Scanley BE, Tucker KA, Oliveto A, Prince C, Sinha R, Potenza MN, Skudlarski P, Wexler BE. Cue-induced brain activity changes and relapse in cocaine-dependent patients. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2006;31:644–50. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Brody AL, Mandelkern MA, London ED, Childress AR, Lee GS, Bota RG, Ho ML, Saxena S, Baxter LR, Jr., Madsen D, Jarvik ME. Brain metabolic changes during cigarette craving. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2002;59:1162–72. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.12.1162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Garavan H, Pankiewicz J, Bloom A, Cho JK, Sperry L, Ross TJ, Salmeron BJ, Risinger R, Kelley D, Stein EA. Cue-induced cocaine craving: neuroanatomical specificity for drug users and drug stimuli. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157:1789–98. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.11.1789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Freed PJ, Yanagihara TK, Hirsch J, Mann JJ. Neural mechanisms of grief regulation. Biol Psychiatry. 2009;66:33–40. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.01.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Zombeck JA, Chen GT, Johnson ZV, Rosenberg DM, Craig AB, Rhodes JS. Neuroanatomical specificity of conditioned responses to cocaine versus food in mice. Physiol Behav. 2008;93:637–50. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2007.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Rhodes JS, Garland T, Jr., Gammie SC. Patterns of brain activity associated with variation in voluntary wheel-running behavior. Behav Neurosci. 2003;117:1243–56. doi: 10.1037/0735-7044.117.6.1243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Rhodes JS, Ryabinin AE, Crabbe JC. Patterns of brain activation associated with contextual conditioning to methamphetamine in mice. Behav Neurosci. 2005;119:759–71. doi: 10.1037/0735-7044.119.3.759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Schroeder BE, Schiltz CA, Kelley AE. Neural activation profile elicited by cues associated with the anxiogenic drug yohimbine differs from that observed for reward-paired cues. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2003;28:14–21. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Beck CH, Fibiger HC. Conditioned fear-induced changes in behavior and in the expression of the immediate early gene c-fos: with and without diazepam pretreatment. J Neurosci. 1995;15:709–20. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-01-00709.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Roitman MF, Wheeler RA, Wightman RM, Carelli RM. Real-time chemical responses in the nucleus accumbens differentiate rewarding and aversive stimuli. Nat Neurosci. 2008;11:1376–7. doi: 10.1038/nn.2219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Carelli RM, Ijames SG, Crumling AJ. Evidence that separate neural circuits in the nucleus accumbens encode cocaine versus “natural” (water and food) reward. J Neurosci. 2000;20:4255–66. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-11-04255.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Roitman MF, Wheeler RA, Carelli RM. Nucleus accumbens neurons are innately tuned for rewarding and aversive taste stimuli, encode their predictors, and are linked to motor output. Neuron. 2005;45:587–97. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.12.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Morrison SE, Salzman CD. The convergence of information about rewarding and aversive stimuli in single neurons. J Neurosci. 2009;29:11471–11483. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1815-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Salamone JD. The involvement of nucleus accumbens dopamine in appetitive and aversive motivation. Behav Brain Res. 1994;61:117–33. doi: 10.1016/0166-4328(94)90153-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Ungless MA. Dopamine: the salient issue. Trends Neurosci. 2004;27:702–6. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2004.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Tronson NC, Schrick C, Guzman YF, Huh KH, Srivastava DP, Penzes P, Guedea AL, Gao C, Radulovic J. Segregated populations of hippocampal principal CA1 neurons mediating conditioning and extinction of contextual fear. J Neurosci. 2009;29:3387–94. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5619-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Swank MW, Bernstein IL. c-Fos induction in response to a conditioned stimulus after single trial taste aversion learning. Brain Res. 1994;636:202–8. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(94)91018-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Kaczmarek L. Molecular biology of vertebrate learning: is c-fos a new beginning? J Neurosci Res. 1993;34:377–81. doi: 10.1002/jnr.490340402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Anokhin KV, Rose SP. Learning-induced Increase of Immediate Early Gene Messenger RNA in the Chick Forebrain. Eur J Neurosci. 1991;3:162–167. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1991.tb00076.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Clayton DF. The genomic action potential. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2000;74:185–216. doi: 10.1006/nlme.2000.3967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Nestler EJ, Barrot M, Self DW. DeltaFosB: a sustained molecular switch for addiction. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:11042–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.191352698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Kleim JA, Lussnig E, Schwarz ER, Comery TA, Greenough WT. Synaptogenesis and Fos expression in the motor cortex of the adult rat after motor skill learning. J Neurosci. 1996;16:4529–35. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-14-04529.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Park TH, Carr KD. Neuroanatomical patterns of fos-like immunoreactivity induced by a palatable meal and meal-paired environment in saline- and naltrexone-treated rats. Brain Res. 1998;805:169–80. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(98)00719-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Franklin TR, Druhan JP. Expression of Fos-related antigens in the nucleus accumbens and associated regions following exposure to a cocaine-paired environment. Eur J Neurosci. 2000;12:2097–106. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2000.00071.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Brown EE, Robertson GS, Fibiger HC. Evidence for conditional neuronal activation following exposure to a cocaine-paired environment: role of forebrain limbic structures. J Neurosci. 1992;12:4112–21. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.12-10-04112.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Neisewander JL, Baker DA, Fuchs RA, Tran-Nguyen LT, Palmer A, Marshall JF. Fos protein expression and cocaine-seeking behavior in rats after exposure to a cocaine self-administration environment. J Neurosci. 2000;20:798–805. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-02-00798.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Topple AN, Hunt GE, McGregor IS. Possible neural substrates of beer-craving in rats. Neurosci Lett. 1998;252:99–102. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(98)00574-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Schroeder BE, Holahan MR, Landry CF, Kelley AE. Morphine-associated environmental cues elicit conditioned gene expression. Synapse. 2000;37:146–58. doi: 10.1002/1098-2396(200008)37:2<146::AID-SYN8>3.0.CO;2-#. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Schroeder BE, Kelley AE. Conditioned Fos expression following morphine-paired contextual cue exposure is environment specific. Behav Neurosci. 2002;116:727–32. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.116.4.727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Schroeder BE, Binzak JM, Kelley AE. A common profile of prefrontal cortical activation following exposure to nicotine- or chocolate-associated contextual cues. Neuroscience. 2001;105:535–45. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(01)00221-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Ciccocioppo R, Sanna PP, Weiss F. Cocaine-predictive stimulus induces drug-seeking behavior and neural activation in limbic brain regions after multiple months of abstinence: reversal by D(1) antagonists. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:1976–81. doi: 10.1073/pnas.98.4.1976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Risinger FO, Cunningham CL. DBA/2J mice develop stronger lithium chloride-induced conditioned taste and place aversions than C57BL/6J mice. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2000;67:17–24. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(00)00310-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Cunningham CL, Ferree NK, Howard MA. Apparatus bias and place conditioning with ethanol in mice. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2003;170:409–22. doi: 10.1007/s00213-003-1559-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Paxinos G, Franklin K. The Mouse Brain Atlas in Sterotaxic Coordinates. second edition Academic Press; San Diego: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- [39].Storey J. A direct approach to false discovery rates. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society. 2002;64:479–498. [Google Scholar]

- [40].Cunningham CL, Gremel CM, Groblewski PA. Drug-induced conditioned place preference and aversion in mice. Nat Protoc. 2006;1:1662–70. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Carrive P, Leung P, Harris J, Paxinos G. Conditioned fear to context is associated with increased Fos expression in the caudal ventrolateral region of the midbrain periaqueductal gray. Neuroscience. 1997;78:165–77. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(97)83047-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Zanoveli JM, Ferreira-Netto C, Brandao ML. Conditioned place aversion organized in the dorsal periaqueductal gray recruits the laterodorsal nucleus of the thalamus and the basolateral amygdala. Exp Neurol. 2007;208:127–36. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2007.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Duncan GE, Knapp DJ, Breese GR. Neuroanatomical characterization of Fos induction in rat behavioral models of anxiety. Brain Res. 1996;713:79–91. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(95)01486-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Staples LG, Hunt GE, Cornish JL, McGregor IS. Neural activation during cat odor-induced conditioned fear and `trial 2' fear in rats. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2005;29:1265–77. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2005.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Tracey I, Ploghaus A, Gati JS, Clare S, Smith S, Menon RS, Matthews PM. Imaging attentional modulation of pain in the periaqueductal gray in humans. J Neurosci. 2002;22:2748–52. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-07-02748.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Michel A, Tambour S, Tirelli E. The magnitude and the extinction duration of the cocaine-induced conditioned locomotion-activated response are related to the number of cocaine injections paired with the testing context in C57BL/6J mice. Behav Brain Res. 2003;145:113–23. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(03)00106-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Phillips TJ, Huson MG, McKinnon CS. Localization of genes mediating acute and sensitized locomotor responses to cocaine in BXD/Ty recombinant inbred mice. J Neurosci. 1998;18:3023–34. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-08-03023.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]