Abstract

Extranodal NK/T cell lymphoma nasal type is an EBV driven non-Hodgkin lymphoma, rare in the United States, with no known satisfactory treatment. Two patients with this entity refractory to CHOP chemotherapy responded to single agent pegaspargase (pegylated L-asparaginase). A 64-year-old Caucasian woman presented with extranodal NK/T lymphoma nasal type on her left buttocks. After initial treatment with loco-regional irradiation and CHOP, she developed extensive lower extremity lesions, and subsequent paranasal sinus involvement. With pegaspargase, she had a dramatic improvement of her skin lesions and proceeded to autologous stem cell transplant. A 48 year old Asian man presented with nasal cavity extranodal NK/T lymphoma which resolved with radiation therapy. Multiple liver lesions which developed while receiving CHOP completely resolved on pegaspargase. L- Asparaginase and its pegylated form have activity in this disease and further exploration alone or in combination is warranted.

Keywords: L-Asparaginase, aspargase, NK/T-Cell Lymphoma, natural killer lymphoma

INTRODUCTION

Extranodal natural killer/T-cell lymphoma, nasal type, or nasal NK/T-cell lymphoma is an extranodal lymphoma usually with an immature natural killer (NK)-cell phenotype and Epstein-Barr virus positivity. It commonly presents in the midfacial region, but can occur in other extranodal sites [1]. There is a broad morphologic spectrum, frequently characterized by necrosis and angioinvasion. The immunophenotype of this lymphoma is either NK or NK/T cell type. Most cases, especially in Asia, are EBV positive. Extranodal NK/T-cell lymphoma is a rare disorder in the United States and Europe, comprising <1% of all lymphomas. There is a geographic predominance in Asia, where it comprises 3–8% of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (NHL), and in Central and South America [2]. More common in males, it may affect children or adults, with median age of diagnosis the fifth decade [3]. There are two clinical entities, nasal and extranasal NK/T cell lymphoma, which diverge in clinical presentation, treatment, and prognosis [4]. They are classified in the same WHO category, however, because they share the same histology and immunophenotype. Treatment generally involves CHOP chemotherapy and involved-field radiotherapy, but relapses are common and there is no standard approach to relapsed disease. We report 2 cases of relapsed/refractory NK/T lymphoma with response to pegaspargase and review the literature on activity of L-asparaginase in this disease.

CASE PRESENTATIONS

Patient 1

A 61 year old white woman with a history of type 2 diabetes, hypertension, Hashimoto’s associated hypothyroidism and diverticulosis presented with a right buttock mass. Excisional biopsy showed extranodal NK/T-cell lymphoma (CD56+, negative for CD3, CD4, CD5, CD8, CD30, ALK-1, CD34, CD117, myeloperoxidase and TdT). EBV latent membrane protein (LMP) immunostain was negative. This was consistent with extranodal NK/T cell lymphoma, nasal type. Staging with CT and PET scans and bone marrow biopsy revealed only the left gluteal mass, consistent with stage IAE extranasal NK/T cell lymphoma. She was asymptomatic, specifically with no complaints referable to nasal passages or aerodigestive tract. Physical exam was remarkable only for well healed left buttock biopsy site. The patient received 3 cycles of CHOP followed by radiation to the left buttock. However, a week after completion of radiation, nodular lesions arose on the buttocks and lower left extremity, and right buttock, all outside the original radiation field. Biopsy of the leg showed recurrent NK/T lymphoma in the dermis and subcutis. During local radiation to the right buttock she developed sinus congestion. CT scan of the maxillofacial region showed soft tissue thickening of the nasal fossa. Biopsy of the nasal mass revealed diffuse, predominantly small cell NK/T-cell lymphoma, CD3+, CD56+ and CD5−. Flow cytometry showed cytoplasmic CD3 dim, CD56 dim, CD25+, and CD16+. EBV early RNA (EBER) was positive by in situ hybridization (ISH). Radiation to the right nasal fossa was initiated, along with prednisone. Treatment with denileukin diftitox was discontinued secondary to capillary leak syndrome with pulmonary edema, with no response. She then developed multiple progressive ulcerated, raised erythematous circumferential lesions on both lower extremities from below the knee to the ankle. CT staging did not show any other disease. Pegaspargase, a pegylated form of L asparaginase, 2500mg/m2 IV every 2 weeks led to a complete response (CR) after 4 doses. Treatment was discontinued after an anaphylactic reaction during the fifth dose. The response lasted 6 months from the end of therapy, at which time cutaneous, but not nasal, relapse occurred. After local radiation, she then proceeded to autologous stem cell transplant with a cyclophosphamide/TBI preparative regimen, but presented 7 months later with leucopenia. Bone marrow biopsy for the first time showed involvement by NK/T lymphoma. She died of progressive disease.

Patient 2

A 47 year old Chinese man noted fullness in the left nasal cavity and difficulty breathing on that side. CT scan revealed a soft tissue opacity filling the left maxillary frontal and ethmoid sinuses. MRI was confirmatory, with no intracranial disease. Biopsy revealed a diffuse lymphohistiocytic infiltrate with large areas of necrosis. Immunophenotyping revealed CD56+, CD3+, CD2+, CD8+, TIA-1+, granzyme+, EBER (by ISH) +, CD30+ (focal), consistent with extranodal NK/T cell lymphoma, nasal type. He denied fevers, chills or night sweats, but had 7–8 pound weight loss over 2 months. His physical exam was remarkable only for erythema and swelling in the inferior turbinate. Bone marrow biopsy and CT scan showed no other evidence of lymphoma. He was diagnosed with Stage IE extranodal NK/T lymphoma, nasal type. He received involved field radiation to 5040 cGy, followed by CHOP for 4 cycles. Two months later, CT scan revealed 4 liver lesions, the largest 2.5 × 2.5 cm. Liver biopsy confirmed NK/T cell lymphoma nasal type, CD56 positive, CD3+, TIA-1+. Pegaspargase was initiated at 2500 units/m2 IV every 21 days, and then reduced to 2000units/m2 secondary to elevated transaminases. CT scan after 7 doses of pegaspargase showed complete resolution of liver lesions. Treatment was stopped after 11 total doses. He is currently being observed in ongoing complete remission assessed by CT scan.

DISCUSSION

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS

Extranodal NK/T cell lymphoma, nasal type occurs in the nose and paranasal area, which includes the upper aerodigestive tract. Location is primarily midline, including nasal cavity, nasopharynx, paranasal sinuses, tonsils, hypopharynx, and larynx. Most patients have localized disease with nasal obstruction and a destructive mass involving the nose, sinuses, and palate. Initial complaints include nasal obstruction, discharge, purulent rhinorrhea, and bleeding. As the disease progresses, necrosis, swelling, bony destruction with erythema, swelling of the face, proptosis, and impairment of extraocular movement may ensue. Midline perforations may occur [5, 6]. Extranasal NK/T cell lymphoma sites include lung, gastrointestinal tract, kidney, pancreas, testis, skin and brain, usually presenting as advanced disease. Extranasal NK/T cell lymphoma staging requires exclusion of nasal involvement. These are more likely to have a higher International Prognostic Index and lactate dehydrogenase levels with lower hemoglobin [7, 8]. Fever, hemophagocytosis and DIC are common with rapid clinical deterioration [2, 3].

DIAGNOSIS

Natural killer (NK) cells are non-T, non-B lymphocytes that mediate major histocompatability complex nonrestricted cytotoxicity against tumor and infected cells [9]. NK cells develop in the bone marrow from hematopoietic stem cells through intermediate developmental stages of lymphoid stem cells, bipotential NK/T progenitors, and committed NK progenitors [10]. NK derived lymphomas are rare. A histopathologic diagnosis of extranodal NK-cell lymphoma, nasal type can be difficult because of extensive necrosis and variable morphology. The diagnosis is based clinicopathologically, integrating clinical presentation, morphology, immunophenotype and genotype. The morphology is typically characterized by a polymorphous angiocentric lymphoid infiltrate invading the vascular walls, producing extensive fibrinoid necrosis. Clinical suspicion should be high in cases of aggressive extranodal lymphoma associated with vascular invasion and necrosis. Expression of at least 1 NK cell marker (CD56, CD16, or CD57) coupled with lack of expression of other lineage markers, i.e. surface CD3, B cell antigens (CD19, CD20), MPO, and germline configuration of TCR and Ig genes are characteristic. Typically, CD2, CD3 (cytoplasmic), CD7, and CD56 are expressed. Cytotoxic granule proteins TIA-1, granzyme B, and perforin are also positive [11]. There are no significant differences in immunophenotypic or genotypic profiles between nasal and extranasal cases [7].

Epstein Barr virus is almost always detectable by in situ hybridization [10, 12, 13]. EBV plays an important role in extranasal NK/T-cell lymphoma and quantitation of circulating plasma EBV DNA levels is prognostically important. In 23 patients with various NK-cell lymphomas, multivariate analysis showed plasma EBV DNA levels was a significant factor impacting on disease free survival. Plasma EBV DNA levels can also be used for disease monitoring. Achievement of CR after treatment correlated with an undetectable plasma EBV DNA levels. Failure to achieve undetectable plasma EBV DNA levels after therapy confers an inferior prognosis. Patients with high plasma EBV DNA levels after therapy are at risk for relapse [4, 14–19].

TREATMENT & PROGNOSIS

While localized disease may remain in remission following radiotherapy with or without chemotherapy, the overall 5 year survival rate, using an anthracycline based regimen (i.e. CHOP) with radiation, is less than 50% [20–22, 23, 24]. For advanced stage disease, chemotherapy is the mainstay of treatment; however, median survival is only 6– 12 months [5, 25]. The median overall survival was inferior for patients with extranasal compared with nasal disease (0.36 years vs. 1.6 years, p<.001), even when comparing only limited stage I/II extranasal vs. nasal disease (.036 vs. 2.96 years, p<.001) [7]. Normal or abnormal NK cells express high levels of MDR1 [26]. In a study of 30 NK/T lymphoma patients treated with CHOP-like chemotherapy, CR rate in MDR1+ patients was lower than those with MDR1 negative lymphoma (20% vs. 60% p=.045), and MDR1+ also predicted lower response rates and worse survival [27]. There is no consensus on the optimal therapeutic regimen in the salvage setting. Etoposide, ifosfamide, and methotrexate based regimens exhibited a CR rate of ~40% with a median disease free survival of 12 months in one study [28], and a 44% response rate in 32 patients with median overall survival of 8.2 months and time to treatment failure of 3.7 months in another [29].

L-asparaginase, an enzyme that hydrolyzes serum L-asparagine, induces asparagine starvation of tumors with low expression of asparagine synthetase. This results in rapid inhibition of protein synthesis and delayed inhibition of DNA and RNA synthesis in lymphocytes [19]. Recent reports suggest efficacy of L-asparaginase in NK/T lymphoma (Table 1). A retrospective study of 45 patients with refractory and relapsed extranodal NK T cell lymphoma, nasal type in China included 41 patients refractory to CHOP based chemotherapy, while 4 others were refractory to CHOP and radiation. Patients were treated with an L-asparaginase based salvage regimen (L-asparaginase 6,000IU/m2 IV days 1–7, vincristine IV 1.4 mg/m2 day 1, and dexamethasone 10 mg IV days 1–7 repeated every 28 days) followed by radiation, if radiation was not received previously. The CR rate was 56%, and overall response rate was 82%. The 3 and 5 year overall survival rate were both 67% [18]. In a retrospective French report of 15 patients (13 relapsed/refractory, 2 front-line), 13 patients with extranodal NK/T-cell lymphoma, nasal type and two patients with aggressive NK-cell leukemia were treated with L-asparaginase +/− dexamethasone, vinblastine and methotrexate. Responses occurred in 13 of the 15 patients [15]. A follow-up prospective study of 18 patients with relapsed NK/T lymphoma using L-asparaginase 6000U/m2 per day days 2, 4, 6 and 8 plus high dose methotrexate day 1 and dexamethasone 40 mg days 1–4 demonstrated 10 CR and 5 PR in 18 patients after 3 cycles [30]. A series of 6 patients treated with L-asparaginase + dexamethasone, methotrexate, ifosfamide and etoposide had significant toxicity, but 3 attained CR and 1 PR [31]. Additional case reports (Table) document response to L-asparaginase alone [16, 17] or in combination regimens [32]. In addition, there is in vitro support for induction of apoptosis in NK cell lines by L-asparaginase [33]. Based on these reports, we treated our patients with relapsed NK/T lymphoma with pegaspargase, selecting the pegylated form to achieve more prolonged continuous asparagine depletion as well as for ease of administration as it requires only a single treatment every 2–3 weeks. While neither of our patients progressed on pegaspargase treatment, the question of resistance to this agent is clearly of interest. Some patients who develop antibodies to one form of asparaginase can be successfully treated with a different form of the enzyme.

Table 1.

Summary of L-asparaginase Treated NK/T cell lymphoma

| Author | N | Stage | Prior Treatment | L-Asparaginase Dose | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reyes V et al. | 2 | 1. Stage IAE (extranasal) 2. Stage I (nasal type) |

1. CHOP, XRT, Ontak 2. CHOP, XRT |

1. Pegaspargase 2500U/m2 q14 days × 4 2. Pegaspargase 2000U/m2 q21days × 11 |

2/2 CR |

| Jaccard et al. [15] | 15 | I–IV | CHOP, RT, DHAP, Decadron, IFN, Thalidomide, ESHAP | 6,000U/m2 IV d1-5 q28 days +/− dexamethasone, methotrexate, vinblastine | 46% CR |

| Yong W et al. [14, 18, 19] | 45 | I–IVB (nasal type) | CHOP or CHOP like regimen | 6,000U/m2 IV D1-7, vincristine 1.4mg/m2 IV d1, dexamethasone 10mg IV d1-7 q28 days +/− radiation | 56% CR |

| Jaccard et al.[30] | 18 | IV (nasal type) | None | 6,000U/m2 IM days 2,4,6,8 + methotrexate 3 gm/m2 d1 + dexamethasone 40 mg days 1–4 +/− radiation | 10 CR + 5 PR |

| Yamaguchi M et al [31] | 6 | IV, New or Relapsed or refractory | None (3) CHOP-like (2); DeVIC +RT (1) |

6,000U/m2 IV d 8, 10, 12, 14, 16, 18, 20 + methotrexate 2 gm/m2 IV d1; and on d 2–4 ifosfamide 1.5 gm/m2, etoposide 100 gm/m2 IV, dexamethasone 40 mg | 3CR + 1PR |

| Nagafuji K et al. [16] | 1 | IVB (nasal type) | CHOP, High dose MTX, Auto transplant |

6,000U/m2 IV × 7 days | CR |

| Matsumoto Y et al. [17] | 1 | IVB (extranasal) | CHOP, Auto- transplant, CHOP, XRT, DeVIC, Amputation | 6,000U/m2 days 1–7, switched to Erwinia L-asparaginase 6,000U/m2 IM 3x/wk × 7 | CR |

| Obama et al [32] | 1 | IV Extranasal | None (followed by CHOP × 6) | 4000U d 1–7 + vincristine 1 mg IV d 1 + prednisolone 100 mg d 1–5 | CR |

Reyes et al NK/T Lymphoma

Our cases and review of the literature show that L-asparaginase is a viable treatment alternative in relapsed NK/T- extranodal lymphoma. Whether the pegylated form is of particular benefit will require further study. It is worth considering development of combination regimens and possibly front-line regimens containing L-asparaginase as potential avenues to optimize use of this agent in this uncommon, but difficult to treat, subtype of lymphoma.

Figure 1.

Extranasal extranodal NK/T Lymphoma. Case #1 pre (left) and post (right) pegaspargase

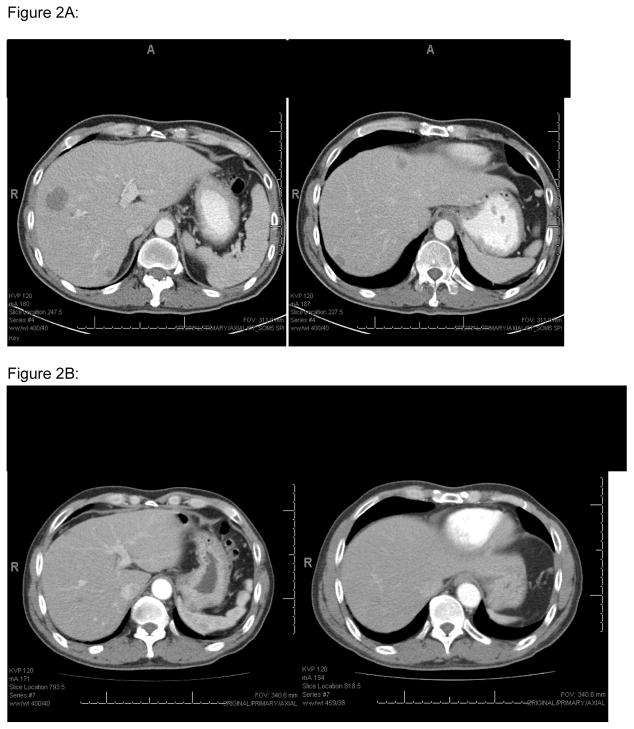

Figure 2.

A (top): Case #2 Liver involvement pre aspargase treatment

B (bottom): Liver involvement post aspargase treatment

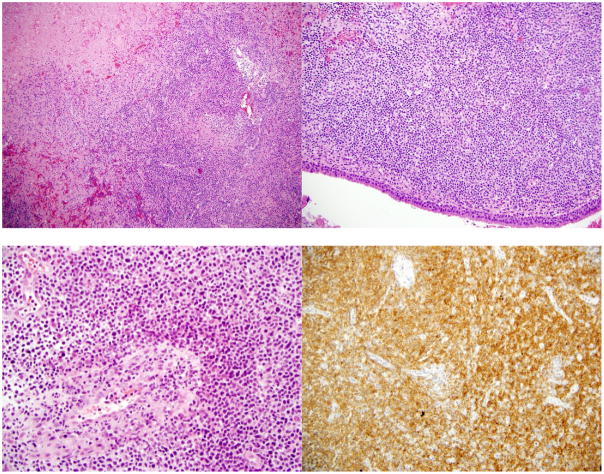

Figure 3.

A (top left): Lymphomatous infiltrate showing infiltration and destruction of a vessel.

B (top right): Nasal septum necrosis and lymphomatous involvement

C (bottom left): Lymphomatous infiltrate of medium sized cells with angiocentric and angiodestructive growth pattern.

D (bottom right): Positive CD56 stain

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by NCI Cancer Center Core Grant CA06927.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Devita V, Rosenberg S, Hellman S. Cancer: Principles & Practice of Oncology. 7. New York: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2004. p. 2295. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Liang R, Todd D, Chan TK, et al. Treatment Outcome and Prognostic Factors for Primary Nasal Lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 1995;13:666–670. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1995.13.3.666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chim CS, Ma SY, Au WY, et al. Primary nasal natural killer cell lymphoma: long-term treatment outcome and relationship with the International Prognostic Index. Blood. 2004;103:216–221. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-05-1401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kwong YL. Natural killer-cell malignancies: diagnosis and treatment. Leukemia. 2005;19:2186–2194. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2403955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cheung MM, Chan JK, Lau WH, et al. Primary Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma of the Nose and Nasopharynx : Clinical Features, Tumor Immunophenotype, and Treatment Outcome in 113 Patients. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16:70–77. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1998.16.1.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Proulx GM, Caudra-Garcia I, Ferry J, et al. Lymphoma of the Nasal Cavity and Paranasal Sinuses Treatment and Outcome of Early Stage Disease. Am J Clin Oncol. 2003;26:6–11. doi: 10.1097/00000421-200302000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Au WY, Weisenburger DD, Intragumtornchai T, et al. Clinical differences between nasal and extranasal natural killer/T-cell lymphoma: a study of 136 cases from the International Peripheral T-Cell Lymphoma Project. Blood. 2009;113:3931–3937. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-10-185256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Suzuki R, Takeuchi K, Oshima K, Nakamura S. Extranodal NK/T-cell lymphoma: diagnosis and treatment cues. Hematol Oncol. 2008;26:66–72. doi: 10.1002/hon.847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Spits H, Lanier LL, Phillips JH. Development of human T and natural killer cells. Blood. 1995;85:2654–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liang X, Graham DK. Natural Killer Cell Neoplasms. Cancer. 2008;112:1425–1436. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ferry JA, Sklar J, Zukerberg LR, et al. Nasal Lymphoma: A Clinicopathologic Study with Immunophenotypic and Genotypic Analysis. Amer J Surg Pathol. 1991;15:268–279. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.International T Cell Lymphoma Project. International Peripheral T-Cell and Natural Killer/T-Cell Lymphoma Study : Pathology Findings and Clinical Outcomes. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:1–10. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.16.4558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jaffe ES. Classification of natural killer (NK) cell and NK-like T-cell malignancies. Blood. 1996;87:1207–1210. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yong W, Zheng W, Zhu J, et al. Midline NK/T-cell lymphoma nasal-type: treatment outcome, effect of L-asparaginase based regimen, and prognostic factors. Hematol Oncol. 2006;24:28–32. doi: 10.1002/hon.765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jaccard A, Petit B, Girault S, et al. L-Asparaginase-based treatment of 15 western patients with extranodal NK/T-cell lymphoma and leukemia and a review of the literature. Ann Oncol Epub. 2008;20:110–116. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdn542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nagafuji K, Fujisaki T, Arima F, Ohshima K. L-Asparaginase Induced Durable Remission of Relapsed Nasal NK/T-Cell Lymphoma After Autologous Peripheral Blood Stem Cell Transplantation. Int J Hematol. 2001;74:447–450. doi: 10.1007/BF02982090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Matsumoto Y, Nomura K, Kanda-Akano, et al. Successful Treatment with Erwinia L-Asparaginase for Recurrent Natural Killer/T Cell Lymphoma. Leuk Lymph. 2003;44:879–882. doi: 10.1080/1042819031000067873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yong W, Zheng W, Zhu J, et al. L-Asparaginase in the treatment of refractory and relapsed extranodal NK/T-cell lymphoma, nasal type. Ann Hematol Epub. 2008;88:647–652. doi: 10.1007/s00277-008-0669-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yong W, Zheng W, Zhang Y, et al. L-Asparaginase-Based Regimen in the Treatment of Refractory Midline Nasal/Nasal-Type T/NK-Cell Lymphoma. Int J Hematol. 2003;78:163–167. doi: 10.1007/BF02983387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim WS, Song SY, Ahn YC, et al. CHOP followed by involved field radiation: Is it optimal for localized nasal natural killer T-cell lymphoma? Ann Oncol. 2001;12:349–352. doi: 10.1023/a:1011144911781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li YX, Yao B, Jin J, et al. Radiotherapy as Primary Treatment for Stage IE and IIE Nasal Natural Killer/T-Cell Lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:181–189. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.2573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kim TM, Lee SY, Jeon YK, et al. Clinical heterogeneity of extranodal NK/T-cell lymphoma, nasal type: a national survey of the Korean Cancer Study Group. Ann Oncol Epub. 2008;19:1477–1484. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdn147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ribrag V, Hajj ME, Janot F, et al. Early locoregional high-dose radiotherapy is associated with long-term disease control in localized primary angiocentric lymphoma of the nose and nasopharynx. Leukemia. 2001;14:1123–1126. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2402148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.You JY, Chi KH, Yang MH, et al. Radiation therapy versus chemotherapy as initial treatment for localized nasal natural killer (NK)/T-cell lymphoma: a single institute survey in Taiwan. Ann Oncol. 2004;115:618–625. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdh143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cheung MM, Chan JK, Wong KF. Natural Killer Cell Neoplasms: A Distinctive Group of Highly Aggressive Lymphomas/Leukemias. Sem Hematol. 2003;40:221–232. doi: 10.1016/s0037-1963(03)00136-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yamaguchi M, Kita K, Miwa H, et al. Frequent Expression of P-Glycoprotein/MDR1 by Nasal T-Cell Lymphoma Cells. Cancer. 1995;76:2351–2356. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19951201)76:11<2351::aid-cncr2820761125>3.0.co;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang B, Li XQ, Ma X, et al. Immunohistochemical expression and clinical significance of P-glycoprotein in previously untreated extranodal NK/T-Cell lymphoma, nasal type. Amer J Hematol. 2008;83:795–799. doi: 10.1002/ajh.21256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cabanillas F, Hagemeister FB, Bodey GP, Freireich EJ. IMVP-16: An Effective Regimen for Patients with Lymphoma Who Have Relapsed After Initial Combination Chemotherapy. Blood. 1982;60:693–697. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kim BS, Kim DW, Im SA, et al. Effective second-line chemotherapy for extranodal NK/T-cell lymphoma consisting of etoposide, ifosfamide, methotrexate, and prednisolone. Ann Oncol Epub. 2008;20:121–128. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdn551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jaccard A, Gachard N, Coppo P, Morschhauser F, Galicier L, Ysebart L, Lenain P, Corront B, Suarez F, Feuillard J, Gaulard P, Bordessoule D, Hermine O. A prospective phase II trial of an L-asparaginase containing regimen in patients with refractory or relapsing extra nodal NK/T-cell lymphoma. Blood. 2008;112:A579. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yamaguchi M, Suzuki R, Kwong YL, Kim WS, Hasegawa Y, Izutsu K, Suzumiya J, Okamura T, Nakamura S, Kawa K, Oshimi K. Phase I study of dexamethasone, methotrexate, ifosfamide, L-asparaginase and etoposide (SMILE) chemotherapy for advanced stage, relapsed or refractory extranodal natural killer (NK)/T cell lymphoma and leukemia. Cancer Science. 2008;99:1016–1020. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2008.00768.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Obama K, Tara M, Niina K. L-asparaginase therapy for advanced extranodal NK/T-cell lymphoma. Int J Hematol. 2003;78:248–250. doi: 10.1007/BF02983802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ando M, Sugimoto K, Kitoh T, Sasaki M, Mukai K, Ando J, Egashira M, Schuster SM, Oshimi K. Selective apoptosis of natural kiler tumours by l-asparaginase. Br J Haematol. 2005;130:860–868. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2005.05694.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]