Abstract

Objectives

The objective of this study was to determine the relative contribution of modifiable risk factors (physical activity, smoking, and alcohol consumption) to inter-subject variation in erectile dysfunction (ED)

Methods

The Boston Area Community Health (BACH) Survey used a multistage stratified random sample to recruit 2,301 men age 30-79 years from the city of Boston between 2002 and 2005. ED was assessed using the 5-item International Index of Erectile Function (IIEF-5). Multiple linear regression models and R2 were used to determine the proportion of the variance explained by modifiabe risk factors.

Results

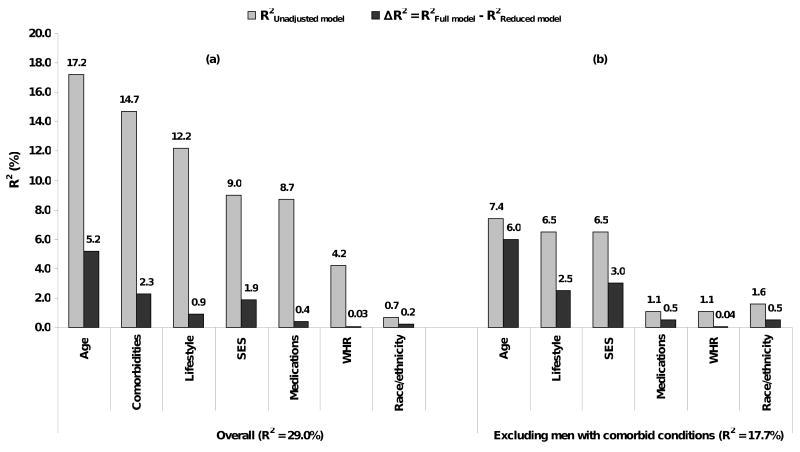

In unadjusted analyses, lifestyle factors accounted for 12.2% of the inter-subject variability in IIEF-5 scores, comparable to the proportion explained by comorbid conditions (14.7%) and socioeconomic status (9%). Lifestyle factors were also significantly associated with age, comorbid conditions and socioeconomic status (SES). A multivariate model including all covariates associated with ED explained 29% of the variance, with lifestyle factors accounting for 0.9% over and above all other covariates in the model. Analyses repeated in a subgroup of 1,215 men without comorbid conditions, show lifestyle factors accounting for 2.5% of the variance after accounting for all other variables in the model.

Conclusions

Results of the present study demonstrate the contribution of modifiable lifestyle factors to the prevalence of ED. These results suggest a role for behavior modification in the prevention of ED.

Keywords: erectile dysfunction, risk factors, prevention, epidemiology

Introduction

Erectile dysfunction (ED) is a common problem in aging men.(Chew, et al., 2008, Feldman, et al., 1994, Papaharitou, et al., 2006, Ponholzer, et al., 2005, Tan, et al., 2007) Prevalence rates increase steadily with age, with complete inability to achieve erection increasing from 5% to 15% between ages 40 to 70 years.(Feldman, et al., 1994) Data from the 2001-2002 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) show an overall prevalence rate of 18.4% in men age ≥20 years, suggesting that approximately 18 million men are affected in the U.S. (Saigal, et al., 2006, Selvin, et al., 2007) Epidemiologic and clinical studies have shown chronic illnesses and conditions such as heart disease, diabetes, hypertension, and obesity to be the primary risk factors for ED.(Barrett-Connor, 2004, Kaiser and Korenman, 1988, Romeo, et al., 2000) Additionally, a number of modifiable lifestyle factors, including physical activity, smoking, and alcohol consumption, have been associated with ED.(Feldman, et al., 2000, Gades, et al., 2005, Muller, et al., 1991, Wei, et al., 1994) Although the magnitude of the association of lifestyle factors on ED is modest relative to the effect of comorbid conditions such as heart disease or diabetes, these factors represent a pathway for intervention by behavior modification for prevention and improvement of ED. The potential in improvement in erectile function by lifestyle modification was illustrated by the beneficial effect of weight loss and physical activity on erectile function in obese men.(Esposito, et al., 2004)

Using data from the Boston Area Community Health (BACH) Survey, the objective of this study was to quantify the relative contributions of modifiable risk factors to inter-subject variations in ED.

Methods

Overall Design

The BACH survey is a population-based epidemiologic survey of a broad range of urologic symptoms and risk factors in a randomly selected sample. Detailed methods have been described elsewhere.(McKinlay and Link, 2007) In brief, BACH used a multi-stage stratified random sample to recruit approximately equal numbers of subjects according to age (30-39, 40-49, 50-59, 60-69, 70-79 years), gender, and race and ethnic group (Black, Hispanic, and White). The BACH sample was recruited from April 2002 through June 2005. Interviews were completed with 63.3% of eligible subjects, resulting in a total sample of 5503 adults (2301 men, 3202 women, 1767 Black, 1877 Hispanic, 1859 White respondents). All protocols and informed consent procedures were approved by the New England Research Institutes' Institutional Review Board. All subjects provided written informed consent.

Data collection

Data were obtained during a 2-hour in-person interview, conducted by a trained (bilingual) phlebotomist/interviewer, generally in the subject's home. Height, weight, hip and waist circumference were measured along with self-reported information on medical and reproductive history, major comorbidities, lifestyle and psychosocial factors, and symptoms of urologic conditions. Two blood pressure measurements were obtained 2 minutes apart and were averaged. Medication use in the past month was collected using a combination of drug inventory and self-report with a prompt by indication.

Erectile Dysfunction

Erectile Dysfunction (ED) was defined using the 5 item International Index of Erectile Function (IIEF-5), a self-administered and validated instrument.(Rosen, et al., 1999) The five items assess erection confidence, erection firmness, maintenance ability, maintenance frequency, and satisfaction. Each item is scored on a five-point ordinal scale where lower values represent poorer sexual function. The IIEF-5 score ranges between 5 and 25 with lower scores indicating increased severity of ED. Severity of ED is classified into five categories as severe (IIEF score 5-7), moderate (8-11), mild to moderate (12-16), mild (17-21), and no ED (22-25).

Covariates

Self-reported race/ethnicity was defined as Black, Hispanic and White according to the Office of Management and Budget classification.8 Socioeconomic status (SES) index was calculated using the method by Green,9 incorporating both education (number of years of school completed) and household income normalized to income in the Northeast United States (US Census 2000). SES was categorized as low (lower 25% of the distribution of the SES index), middle (middle 50% of the distribution), and high (upper 25% of the distribution). Body mass index (BMI) was categorized as <25.0, 25.0-29.9, and ≥30.0 kg/m2. Physical activity was measured using the Physical Activity Scale for the Elderly (PASE) and was categorized as low (<100), medium (100-250), and high (>250).(Washburn, et al., 1993) Alcohol consumption was defined as alcoholic drinks including beer, wine and hard liquor consumed per day: 0, <1, 1-2.9, ≥3 drinks per day. Pack-years of smoking were calculated by multiplying the number of packs (20 cigarettes in one pack) smoked per day by the number of years smoked. Comorbid conditions included in the analysis were heart disease, diabetes, hypertension, and depression. The presence of comorbidities was defined as a yes response to “Have you ever been told by a health care provider that you have or had….”? Heart disease was defined by self-report of myocardial infarction, angina, congestive heart failure, coronary artery bypass, or angioplasty stent. Participants reporting five or more depressive symptoms (out of 8) using the abbreviated Center for Epidemiological Studies – Depression (CES-D) scale were considered to have depressive symptoms.(Turvey, et al., 1999) Use of medications thought to exacerbate ED symptoms were included in the analysis: any use of beta blockers, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), tricyclic antidepressants, anti-psychotics, and diuretics.(Francis, et al., 2007, Ricci, et al., 2003, Rosen and Marin, 2003) A count variable (0, 1, 2+) was created to account for use of any of these medications.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics, proportions for categorical variables and mean and standard errors (SE) for continuous variables, were used to describe the analysis sample. Using the IIEF-5 score as a continuous variable, linear regression was used to assess the association between ED and risk factors included in the analysis. Multiple linear regression models were used to adjust for potential confounding effect of covariates. As lower IIEF-5 scores indicate worse erectile function, a negative coefficient is interpreted as indicative of worse ED. Covariates were first tested in age-adjusted linear regression models. Covariates meeting a minimal criterion for association with IIEF-5 score (overall F-test p<0.1 or trend test p<0.1) were included in a larger model (full model). We used the R2 to determine the proportion of the variance explained by each model. The proportion of variance explained by each group of variables (e.g. lifestyle factors) or individual variable (e.g. age) was assessed as the R2 from an unadjusted model including only that single group or individual variable. The contribution of each group over and above all other covariates in the full model was determined as the difference in R2 between the full model (R2Full Model) and a reduced model (R2Reduced Model) with the group or individual variable removed while controlling for all other covariates: ΔR2 = R2Full Model - R2Reduced Model. Analyses were repeated after excluding subjects with comorbid conditions (n=1215).

To account for the complex sampling design, analyses were conducted using SUDAAN 10.0. Multiple imputation was used to impute plausible values for missing data.(Schafer, 1997) Twenty-five multiple imputations were performed separately by gender and race/ethnicity using all relevant variables. To be representative of the city of Boston, observations were weighted inversely proportional to their probability of selection.(Cochran, 1977) Weights were post-stratified to the Boston population according to the 2000 census.

Results

Characteristics of the analysis sample are presented in Table 1. About 47% reported any symptom of ED (IIEF-5 ≤21), and about 21% reported mild/moderate to severe ED (IIEF-5<17). Almost one third of men were obese (BMI≥30 kg/m2), and 16.6% were smokers with 20 or more pack-years of smoking. Prevalence of major chronic illnesses ranged between 9.3% for diabetes to 26.2% for hypertension. Prevalence of use of medications that could potentially exacerbate ED symptoms was 25.2% with 7.6% reporting use of 2 or more of these medications.

Table 1.

Descriptive characteristics of analysis sample. Boston Area Community Health (BACH) Survey 2002-2005.

| n (weighted %) | ||

|---|---|---|

| IIEF-5 | None (22-25) | 989 (53.4) |

| Mild (17-21) | 698 (25.9) | |

| Mild/Moderate (12-16) | 356 (11.5) | |

| Moderate (8-11) | 162 (5.8) | |

| Severe (5-7) | 96 (3.4) | |

| Age | mean (SE) | 47.6 (0.45) |

| 30-39 | 615 (37.2) | |

| 40-49 | 659 (25.8) | |

| 50-59 | 510 (17.8) | |

| 60-79 | 517 (19.2) | |

| Race | White | 835 (36.2)* |

| Black | 700 (30.4)* | |

| Hispanic | 766 (33.3)* | |

| SES | Low | 970 (24.3) |

| Middle | 954 (29.1) | |

| High | 377 (26.6) | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | mean (SE) | 28.6 (0.25) |

| <25 | 596 (26.6) | |

| 25-29 | 905 (40.7) | |

| 30+ | 801 (32.7) | |

| WHR** | mean (SE) | 0.92 (0.003) |

| <0.95 | 1469 (66.9) | |

| 0.95-1.0 | 538 (21.5) | |

| >1.0 | 294 (11.6) | |

| Physical Activity (PASE) | Low | 694 (26.8) |

| Moderate | 1069 (47.4) | |

| High | 538 (25.8) | |

| Smoking | Never | 878 (38.9) |

| <10 pack-yrs | 711 (32.6) | |

| 10-19 pack-yrs | 261 (11.9) | |

| 20+ pack-yrs | 451 (16.6) | |

| Alcohol consumption (drinks/day) | never | 800 (27.5) |

| <1/day | 815 (38.9) | |

| 1-3/day | 434 (24.1) | |

| 3+/day | 252 (9.6) | |

| Heart | 248 (10.2) | |

| Hypertension | 735 (26.2) | |

| Diabetes | 298 (9.3) | |

| Depression | 391 (14.0) | |

| Medications use (count variable)*** | 0 | 1687 (74.8) |

| 1 | 399 (17.6) | |

| 2+ | 215 (7.6) |

Unweighted %

Waist to hip ratio (WHR)

Use of medications thought to exacerbate symptoms of ED: any use of beta blockers, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), tricyclic antidepressants, anti-psychotics, and diuretics.

The association of IIEF-5 score with covariates included in the analysis is presented in Table 2. Except for BMI, all covariates showed statistically significant associations with IIEF-5 scores after adjusting for age, and were included in the larger full model. The strongest associations observed in the full model were with age, comorbid conditions, and SES. Similar results were observed when analyses were repeated on a subsample of 1215 men without comorbid conditions.

Table 2.

Association of IIEF-5 scores and covariates included in the analysis. Linear regression coefficients (β) and 95% confidence intervals (95%CI). Boston Area Community Health (BACH) Survey 2002-2005.

| Overall (N=2301) | Overall (N=2301) | Excluding men with comorbid conditions (N=1215) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age-adjusted β (95% CI) | p-value | p-trend | Full model β (95% CI) | p-value | p-trend | Full model β (95% CI) | p-value | p-trend | ||

| Age | per 10 years | -1.68* (-1.92, -1.45) | <0.01 | -1.14 (-1.41, -0.87) | <0.01 | -1.00 (-1.34, -0.66) | <0.01 | |||

| Race | White | 0.00 | <0.01 | 0.00 | 0.09 | 0.00 | 0.07 | |||

| Black | -0.73 (-1.36, -0.10) | 0.08 (-0.59, 0.76) | 0.15 (-0.64, 0.93) | |||||||

| Hispanic | -1.90 (-2.51, -1.30) | -0.67 (-1.47, 0.12) | -0.82 (-1.71, 0.07) | |||||||

| SES | Low | -2.69 (-3.52, -1.86) | <0.01 | <0.01 | -1.91 (-2.82, -0.99) | <0.01 | <0.01 | -1.73 (-2.76, -0.70) | 0.01 | <0.01 |

| Middle | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | |||||||

| High | 0.63 (-0.04, 1.31) | 0.16 (-0.54, 0.86) | 0.83 (0.01, 1.66) | |||||||

| BMI (kg/m2) | <25 | 0.00 | 0.35 | 0.17 | ||||||

| 25-29 | -0.10 (-0.85, 0.65) | |||||||||

| 30+ | -0.52 (-1.30, 0.25) | |||||||||

| Waist-to-hip ratio (WHR) | <0.95 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.52 | 0.57 | 0.00 | 0.57 | 0.62 | ||

| 0.95-1.0 | -1.01 (-2.64, -0.26) | <0.01 | <0.01 | -0.40 (-1.08, 0.28) | -0.43 (-1.26, 0.39) | |||||

| >1.0 | -1.13 (-2.08, -0.06) | -0.12 (-1.15, 0.91) | 0.07 (-1.05, 1.19) | |||||||

| Physical Activity (PASE) | Low | 0.00 | <0.01 | <0.01 | 0.00 | 0.17 | 0.07 | 0.00 | 0.49 | 0.27 |

| Moderate | 1.48 (0.68, 2.29) | 0.62 (-0.15, 1.39) | 0.58 (-0.44, 1.61) | |||||||

| High | 1.92 (1.12, 2.72) | 0.75 (-0.05, 1.55) | 0.63 (-0.43, 1.68) | |||||||

| Smoking | Never | 0.00 | 0.01 | <0.01 | 0.00 | 0.27 | 0.22 | 0.00 | 0.32 | 0.76 |

| <10 pack-yrs | 0.10 (-0.56, 0.76) | 0.25 (-0.43, 0.92) | 0.44 (-0.31, 1.20) | |||||||

| 10-19 pack-yrs | -0.31 (-1.47, 0.84) | -0.19 (-1.26, 0.89) | -0.54 (-1.93, 0.85) | |||||||

| 20+ pack-yrs | -1.36 (-2.26, -0.45) | -0.63 (-1.59, 0.33) | 0.53 (-0.80, 1.87) | |||||||

| Alcohol Consumption (drinks/day) | never | 0.00 | <0.01 | <0.01 | 0.00 | 0.37 | 0.71 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.35 |

| <1/day | 1.46 (0.64, 2.28) | 0.68 (-0.10, 1.47) | 1.37 (0.54, 2.20) | |||||||

| 1-3/day | 1.67 (0.76, 2.57) | 0.40 (-0.48, 1.27) | 0.92 (0.13, 1.97) | |||||||

| 3+/day | 0.46 (0.53, 1.46) | 0.16 (-0.85, 1.16) | 0.74 (0.50, 1.97) | |||||||

| Heart disease | -2.95 (-4.22, -1.68) | <0.01 | -1.70 (-2.99, -0.40) | 0.01 | ||||||

| Hypertension | -0.98 (-1.84, -0.13) | 0.02 | 0.10 (-0.72, 0.91) | 0.82 | ||||||

| Diabetes | -2.60 (-3.91, -1.28) | <0.01 | -1.40 (-2.69, -0.11) | 0.03 | ||||||

| Depression | -2.52 (-3.52, -1.52) | <0.01 | -1.43 (-2.41, -0.44) | <0.01 | ||||||

| Medications use (count) | 0 | 0.00 | <0.01 | <0.01 | 0.00 | 0.16 | 0.08 | 0.00 | 0.92 | 0.70 |

| 1 | -1.22 (-2.26, -0.18) | -0.30 (-1.27, 0.66) | -0.19 (-1.42, 1.05) | |||||||

| 2+ | -3.32 (-4.67, -1.98) | -1.44 (-2.91, 0.03) | -0.86 (-6.40, 4.67) | |||||||

Unadjusted

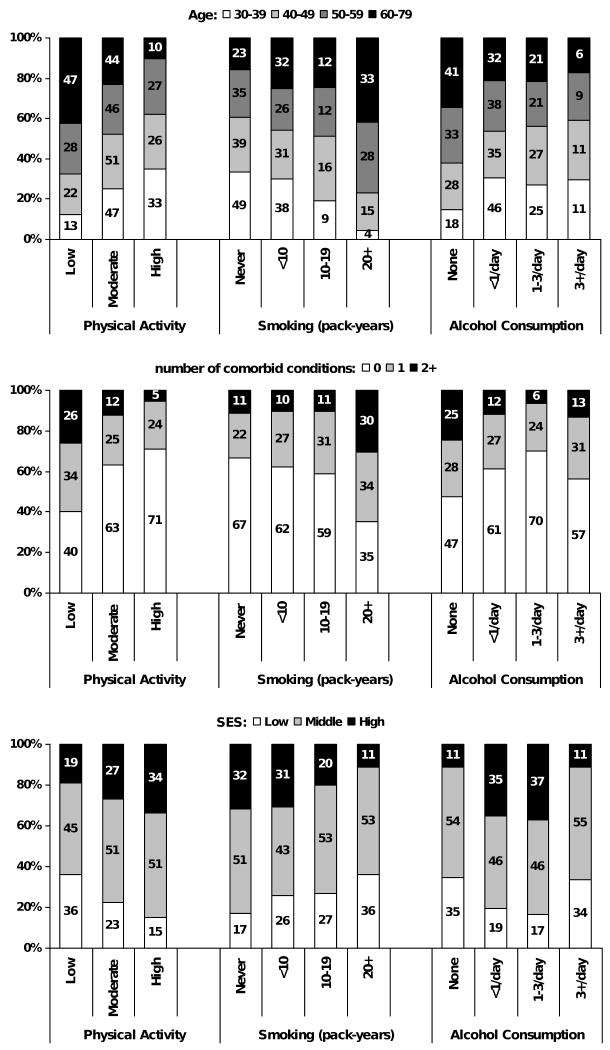

The proportion of explained variance for each factor is presented in Figure 1 (panel a), before and after adjusting for covariates included in the analysis. In unadjusted analyses, lifestyle factors accounted for 12.2% of the variance. The R2 statistic for the full model shows that this model accounted for 29% of inter-individual variation in IIEF-5 scores. As the covariates included in the full model are not independent of each other, the proportion of the variance explained by each variable or group of variables is reduced compared to unadjusted analyses. Statistically significant associations observed of lifestyle factors with age, comorbid conditions, and SES are shown in Figure 2 (χ2 p-value <0.001 for all associations). In adjusted analyses, age accounted for 5.2% of the variability over and above all the other covariates in the model while comorbid conditions accounted for 2.3% and SES accounted for 1.9%. Contribution of lifestyle factors was reduced to 0.9% with similar R2 (0.3%) for each individual variable. Similar results were observed in analyses repeated after excluding men who reported no partner availability (data not shown).

Figure 1.

IIEF-5 score explained variance. Explained variance from unadjusted models (R2Unadjusted model) including only individual variable (e.g. age) or groups of variables (e.g. lifestyle) of interest. Explained variance due to each group over and above all other covariates determined as the difference between the R2 from the full model including all covariates and a reduced model with the group or variable of interest removed: ΔR2 = R2Full model – R2Reduced model. Boston Area Community Health (BACH) Survey 2002-2005.

Figure 2.

Age, comorbidity, and socioeconomic status (SES) by lifestyle factors: physical activity, pack-years of smoking, alcohol consumption. Boston Area Community Health (BACH) Survey 2002-2005.

Analyses were repeated on a subset of men (n=1215) without comorbid conditions (heart disease, hypertension, diabetes, and depression). Results from the full model are presented in Figure 1 (panel b). This model accounted for 17.7% of the total variance. Age and SES were again important contributors accounting for 6% and 3% of the variability over and above all other variables in the model. The contribution of lifestyle factors was similar to SES, explaining 2.5% f the variability in IIEF-5 scores in adjusted analyses.

Discussion

Results from the BACH study demonstrate the contribution of modifiable lifestyle factors including physical activity, smoking, and alcohol consumption to the prevalence of ED in addition to well established risk factors for ED such as age and comorbid conditions. The correlation of these factors with both ED and associated chronic illnesses illustrates the opportunity of intervention through behavior modification such as increased physical activity and smoking cessation.

The impact of behavioral risk factors including smoking, physical activity, and alcohol consumption has been investigated previously. Data from cross-sectional studies have shown a dose-response association between increasing pack-years of smoking and ED.(Gades, et al., 2005, Kupelian, et al., 2007) Incidence of ED was as much as twice as high among smokers compared to non-smokers.(Bacon, et al., 2006, Feldman, et al., 2000) Furthermore, smoking has been associated with progression of ED.(Travison, et al., 2007) A beneficial effect of smoking cessation on erectile function has been reported,(Pourmand, et al., 2004) particularly among younger men.(Derby, et al., 2000, Guay, et al., 1998) The association of alcohol consumption and ED is more equivocal. Data from a large, cross-national study conducted in four countries has shown a lower prevalence of ED with moderate alcohol consumption compared to heavy drinking or no alcohol consumption.(Nicolosi, et al., 2003) Similar results were reported in a study of ED among diabetic men.(Malavige, et al., 2008) In cross-sectional data from the MMAS, excessive alcohol consumption (more than >600 ml/week) was associated with a moderate increase risk of ED.(Feldman, et al., 1994) However, this association was not replicated in longitudinal analyses of lifestyle change.(Derby, et al., 2000) No association between alcohol consumption and ED was reported by the Health Professionals Follow-up Study (HPFS) or the Krimpen Study.(Bacon, et al., 2003, Blanker, et al., 2001) A meta-analysis of cross-sectional studies showed an overall protective association of alcohol and ED.(Cheng, et al., 2007) A decrease in risk of ED has been consistently associated with increased levels of physical activity. An inverse association between physical activity levels and ED was observed in the HPFS, with the association more evident among older men (age >60). (Bacon, et al., 2003) Longitudinal data from MMAS show that change in physical activity affects risk of ED. Incidence of ED was highest among men who were sedentary at both baseline and follow-up, while the lowest incidence of ED was observed among men who were sedentary at baseline but became active during the course of the study.(Derby, et al., 2000) Physical activity is inversely associated with obesity, a known risk factor for ED. Results of a randomized trial on the effect of weight loss and exercise show significant improvement in erectile function in the intervention group compared to the control group.(Esposito, et al., 2004) Results of the present study are consistent with the overall trends reported in the literature. Increased risk of ED was observed with increased duration and intensity of smoking, while moderate levels of alcohol consumption and increased levels of physical activity were associated with a decreased risk of ED. While age and comorbid conditions were the most important contributing factors associated with ED, behavioral risk factors were important covariates explaining a larger proportion of the variance in IIEF-5 scores than measures of adiposity (BMI, waist-to-hip ratio), medications use, and race/ethnicity.

Study limitations and strengths

This study has many strengths, however there are some important limitations. The BACH survey is a community-based random sample across a broad age range (30-79) and includes large numbers of minority participants representative of both the Black and Hispanic populations. ED is assessed using the IIEF-5, a validated instrument for ED assessment widely used in both clinical and epidemiological studies. Additionally, the IIEF instrument has been validated among minority populations. In contrast, both NHANES and the MARSH study used a single, global self-assessment question to ascertain ED status. Although use of a single question to assess ED has been shown to be valid and reliable in White men,(O'Donnell, et al., 2005) this approach has not yet been validated among minority populations. A limitation of the use of the IIEF-5 instrument is recall bias among men who had not engaged in sexual activities in the four weeks preceding completion of the questionnaire, potentially resulting in greater misclassification in this group. Although history of chronic illnesses was assessed by self-report with the potential for reporting and/or recall bias, previous research has demonstrated the reliability and validity of self-report for heart disease, diabetes, and hypertension.(Bergmann, et al., 1998, Okura, et al., 2004, St Sauver, et al., 2005) The BACH study was limited geographically to the Boston area. However, comparison of sociodemographic and health-related variables from the BACH survey with other large regional (Boston Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS)) and national (NHANES, National Health Interview Survey (NHIS), national BRFSS) have shown that BACH estimates are comparable on health related variables.

Conclusions

Results of the present study demonstrate the contribution of modifiable lifestyle factors to the prevalence of ED. With the accumulating evidence linking ED and cardiovascular disease, implying a common vascular etiology, ED is increasingly viewed as a warning sign of impending cardiovascular events. The association of modifiable behavioral factors with ED, especially among men without comorbid conditions, underscores the importance of intervention studies targeting lifestyle changes, such as increased physical activity and smoking cessation, in the effort to prevent development of ED and subsequent cardiovascular disease.

Acknowledgments

Funding: The BACH survey is supported by DK 56842 from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; and an unrestricted educational grant to NERI from Bayer Healthcare. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases or the National Institutes of Health. The Corresponding Author retains the right to provide a copy of the final manuscript to the NIH upon acceptance for publication, for public archiving in PubMed Central as soon as possible but no later than 12 months after publication.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Bacon CG, Mittleman MA, Kawachi I, Giovannucci E, Glasser DB, Rimm EB. Sexual function in men older than 50 years of age: results from the health professionals follow-up study. Ann Intern Med. 2003;139:161–8. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-139-3-200308050-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bacon CG, Mittleman MA, Kawachi I, Giovannucci E, Glasser DB, Rimm EB. A prospective study of risk factors for erectile dysfunction. J Urol. 2006;176:217–21. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(06)00589-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett-Connor E. Cardiovascular risk stratification and cardiovascular risk factors associated with erectile dysfunction: assessing cardiovascular risk in men with erectile dysfunction. Clin Cardiol. 2004;27:I8–13. doi: 10.1002/clc.4960271304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergmann MM, Byers T, Freedman DS, Mokdad A. Validity of self-reported diagnoses leading to hospitalization: a comparison of self-reports with hospital records in a prospective study of American adults. Am J Epidemiol. 1998;147:969–77. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanker MH, Bohnen AM, Groeneveld FP, Bernsen RM, Prins A, Thomas S, Bosch JL. Correlates for erectile and ejaculatory dysfunction in older Dutch men: a community-based study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2001;49:436–42. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2001.49088.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng JY, Ng EM, Chen RY, Ko JS. Alcohol consumption and erectile dysfunction: meta-analysis of population-based studies. Int J Impot Res. 2007;19:343–52. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijir.3901556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chew KK, Stuckey B, Bremner A, Earle C, Jamrozik K. Male erectile dysfunction: its prevalence in Western australia and associated sociodemographic factors. J Sex Med. 2008;5:60–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2007.00548.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cochran W. Sampling Techniques. John Wiley and Sons; New York, NY: 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Derby CA, Mohr BA, Goldstein I, Feldman HA, Johannes CB, McKinlay JB. Modifiable risk factors and erectile dysfunction: can lifestyle changes modify risk? Urology. 2000;56:302–6. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(00)00614-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esposito K, Giugliano F, Di Palo C, Giugliano G, Marfella R, D'Andrea F, D'Armiento M, Giugliano D. Effect of lifestyle changes on erectile dysfunction in obese men: a randomized controlled trial. Jama. 2004;291:2978–84. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.24.2978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldman HA, Goldstein I, Hatzichristou DG, Krane RJ, McKinlay JB. Impotence and its medical and psychosocial correlates: results of the Massachusetts Male Aging Study. J Urol. 1994;151:54–61. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)34871-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldman HA, Johannes CB, Derby CA, Kleinman KP, Mohr BA, Araujo AB, McKinlay JB. Erectile dysfunction and coronary risk factors: prospective results from the Massachusetts male aging study. Prev Med. 2000;30:328–38. doi: 10.1006/pmed.2000.0643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francis ME, Kusek JW, Nyberg LM, Eggers PW. The contribution of common medical conditions and drug exposures to erectile dysfunction in adult males. J Urol. 2007;178:591–6. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2007.03.127. discussion 596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gades NM, Nehra A, Jacobson DJ, McGree ME, Girman CJ, Rhodes T, Roberts RO, Lieber MM, Jacobsen SJ. Association between smoking and erectile dysfunction: a population-based study. Am J Epidemiol. 2005;161:346–51. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwi052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guay AT, Perez JB, Heatley GJ. Cessation of smoking rapidly decreases erectile dysfunction. Endocr Pract. 1998;4:23–6. doi: 10.4158/EP.4.1.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser FE, Korenman SG. Impotence in diabetic men. Am J Med. 1988;85:147–52. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(88)90408-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kupelian V, Link CL, McKinlay JB. Association between smoking, passive smoking, and erectile dysfunction: results from the Boston Area Community Health (BACH) Survey Eur Urol. 2007;52:416–22. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2007.03.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malavige LS, Jayaratne SD, Kathriarachchi ST, Sivayogan S, Fernando DJ, Levy JC. Erectile dysfunction among men with diabetes is strongly associated with premature ejaculation and reduced libido. J Sex Med. 2008;5:2125–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2008.00907.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKinlay JB, Link CL. Measuring the urologic iceberg: design and implementation of the Boston Area Community Health (BACH) Survey Eur Urol. 2007;52:389–96. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2007.03.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller SC, el-Damanhoury H, Ruth J, Lue TF. Hypertension and impotence. Eur Urol. 1991;19:29–34. doi: 10.1159/000473574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicolosi A, Moreira ED, Jr, Shirai M, Bin Mohd Tambi MI, Glasser DB. Epidemiology of erectile dysfunction in four countries: cross-national study of the prevalence and correlates of erectile dysfunction. Urology. 2003;61:201–6. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(02)02102-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Donnell AB, Araujo AB, Goldstein I, McKinlay JB. The validity of a single-question self-report of erectile dysfunction. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20:515–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.0076.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okura Y, Urban LH, Mahoney DW, Jacobsen SJ, Rodeheffer RJ. Agreement between self-report questionnaires and medical record data was substantial for diabetes, hypertension, myocardial infarction and stroke but not for heart failure. J Clin Epidemiol. 2004;57:1096–103. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2004.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papaharitou S, Athanasiadis L, Nakopoulou E, Kirana P, Portseli A, Iraklidou M, Hatzimouratidis K, Hatzichristou D. Erectile dysfunction and premature ejaculation are the most frequently self-reported sexual concerns: profiles of 9,536 men calling a helpline. Eur Urol. 2006;49:557–63. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2005.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ponholzer A, Temml C, Mock K, Marszalek M, Obermayr R, Madersbacher S. Prevalence and risk factors for erectile dysfunction in 2869 men using a validated questionnaire. Eur Urol. 2005;47:80–5. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2004.08.017. discussion 85-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pourmand G, Alidaee MR, Rasuli S, Maleki A, Mehrsai A. Do cigarette smokers with erectile dysfunction benefit from stopping?: a prospective study. BJU Int. 2004;94:1310–3. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2004.05162.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ricci E, Parazzini F, Mirone V, Imbimbo C, Palmieri A, Bortolotti A, Di Cintio E, Landoni M, Lavezzari M. Current drug use as risk factor for erectile dysfunction: results from an Italian epidemiological study. Int J Impot Res. 2003;15:221–4. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijir.3901008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romeo JH, Seftel AD, Madhun ZT, Aron DC. Sexual function in men with diabetes type 2: association with glycemic control. J Urol. 2000;163:788–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosen RC, Cappelleri JC, Smith MD, Lipsky J, Pena BM. Development and evaluation of an abridged, 5-item version of the International Index of Erectile Function (IIEF-5) as a diagnostic tool for erectile dysfunction. Int J Impot Res. 1999;11:319–26. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijir.3900472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosen RC, Marin H. Prevalence of antidepressant-associated erectile dysfunction. J Clin Psychiatry. 2003;64 10:5–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saigal CS, Wessells H, Pace J, Schonlau M, Wilt TJ. Predictors and prevalence of erectile dysfunction in a racially diverse population. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:207–12. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.2.207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schafer J. Analysis of incomplete multivariate data. Chapman and Hall; London: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Selvin E, Burnett AL, Platz EA. Prevalence and risk factors for erectile dysfunction in the US. Am J Med. 2007;120:151–7. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2006.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- St Sauver JL, Hagen PT, Cha SS, Bagniewski SM, Mandrekar JN, Curoe AM, Rodeheffer RJ, Roger VL, Jacobsen SJ. Agreement between patient reports of cardiovascular disease and patient medical records. Mayo Clin Proc. 2005;80:203–10. doi: 10.4065/80.2.203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan HM, Low WY, Ng CJ, Chen KK, Sugita M, Ishii N, Marumo K, Lee SW, Fisher W, Sand M. Prevalence and correlates of erectile dysfunction (ED) and treatment seeking for ED in Asian Men: the Asian Men's Attitudes to Life Events and Sexuality (MALES) study. J Sex Med. 2007;4:1582–92. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2007.00602.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Travison TG, Shabsigh R, Araujo AB, Kupelian V, O'Donnell AB, McKinlay JB. The natural progression and remission of erectile dysfunction: results from the Massachusetts Male Aging Study. J Urol. 2007;177:241–6. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2006.08.108. discussion 246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turvey CL, Wallace RB, Herzog R. A revised CES-D measure of depressive symptoms and a DSM-based measure of major depressive episodes in the elderly. Int Psychogeriatr. 1999;11:139–48. doi: 10.1017/s1041610299005694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Washburn RA, Smith KW, Jette AM, Janney CA. The Physical Activity Scale for the Elderly (PASE): development and evaluation. J Clin Epidemiol. 1993;46:153–62. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(93)90053-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei M, Macera CA, Davis DR, Hornung CA, Nankin HR, Blair SN. Total cholesterol and high density lipoprotein cholesterol as important predictors of erectile dysfunction. Am J Epidemiol. 1994;140:930–7. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a117181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]