Abstract

Primary fractions from the extract of a tropical red alga mixed with filamentous cyanobacteria, collected from Papua New Guinea, were active in a neurotoxicity assay. Bioassay guided isolation led to two natural products (1, 2) with relatively potent calcium ion influx properties. The more prevalent of the neurotoxic compounds (1) was characterized by extensive NMR, mass spectrometry, and X-ray crystallography, and shown to be identical to a polybrominated diphenyl ether metabolite present in the literature, but reported with different NMR properties. To clarify this anomalous result, we synthesized a candidate isomeric polybrominated diphenyl ether (3), but this clearly had different NMR shifts than the reported compound. We conclude that the original isolate of 3,4,5-tribromo-2-(2,4-dibromophenoxy)phenol was contaminated with a minor compound, giving rise to the observed anomalous NMR shifts. The second and less abundant natural product (2) isolated in this study was a more highly brominated species. All three compounds showed a low micromolar ability to increase intracellular calcium ion concentrations in mouse neocortical neurons as well as toxicity to zebrafish. Because polybrominated diphenyl ethers have both natural as well as anthropomorphic origins, and accumulate in marine organisms at higher trophic level (mammals, fish, birds), these neurotoxic properties are of environmental significance and concern.

Keywords: Hydroxylated polybrominated diphenyl ether, red alga, cyanobacteria, environmental neurotoxin, ichthyotoxin, Ca2+ modulation

Introduction

Polybrominated diphenyl ethers (PBDEs) have recently attracted considerable attention due to an increasing awareness that these compounds accumulate in higher trophic level animals, including sperm whales (Marsh et al., 2005; Vos et al., 2003), sea gulls (Verreault et al., 2007), seals (Vos et al., 2003), polar bears (Kelly et al., 2008), as well as in humans (Betts et al., 2002; Athanasiadou et al., 2008). Some PBDEs are industrially produced in large quantities for use as flame retardants, and therefore their presence in animals has generally been assumed to be of anthropogenic origin (Hale et al., 2003). Hydroxylated congeners of PBDEs (OH-PBDEs) have also been found in many of these same higher animals (Verreault et al., 2007; Kelly et al., 2008; McKinney et al., 2006a), and recent studies have shown that the OH-PBDEs found in large marine-associated animals may be of mixed origins with some deriving from natural sources and the others being derivatives of anthropogenic PBDEs (McKinney et al., 2006b; Kelly et al., 2008). Moreover, a variety of anthropogenic PBDEs have been shown to undergo hydroxylation in rats via oxidative metabolism, thereby producing OH-PBDE congeners (Malmberg et al., 2005; Marsh et al., 2006). Nevertheless, a number of OH-PBDEs are known to be natural products of various marine organisms, such as sponges, tunicates, and cyanobacteria (Carte and Faulkner, 1981; Carte et al., 1986; Unson et al., 1994). Environmental concerns have been raised over the occurrence of PBDEs in higher animals because PBDEs have been linked to endocrine disruption (Vos et al., 2003; Mariussen and Fonnum, 2006). Activities similar to those of chlorinated aromatic compounds have been observed with PBDEs, such as aryl hydrocarbon-receptor agonist and antagonist activities, thyroid toxicity, and effects on the immune system (Hwang et al., 2008). Neonatal exposure to PBDEs has been shown to cause neurotoxicity in adult animals (Mariussen and Fonnum, 2006). OH-PBDEs have also been shown to disrupt thyroid hormone homeostasis presumably due to their structural similarity to the thyroxin-type endogenous thyroid hormones (Kelly et al., 2008). Recently, BDE-47 and 6-OH-BDE-47 have been shown to trigger an increase in cytosolic Ca2+ concentration as well as exocytosis of catecholamines in neuronal cells within a few minutes (Dingemans et al., 2008 and 2007). These findings indicate that PBDEs and OH-PBDEs have the potential to acutely disrupt normal neuronal communication in animals.

Our program has been systematically screening marine algae and cyanobacteria for secondary metabolites with neuropharmacological properties, partially because of the environmental impacts these substances may impose, and partially to detect agents with potentially useful biomedical properties (Berman and Murray, 2000; Li et al., 2001; Rogers et al., 2002; Dravid and Murray, 2003). Because a variety of cellular events can trigger an increase in cytosolic Ca2+ levels in neuronal cells, we have employed a FLIPR-based fluorescence assay which detects cytoplasmic Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]i) in mouse neocortical neurons. Herein, we describe the assay-guided isolation, structural determination and neurotoxicological evaluation of two OH-PBDE congeners (1 and 2, Figure 1) from a mixed assemblage of marine cyanobacteria and a red alga. In the course of this work, we have also corrected the assignment of a 13C NMR signal for 1 in the literature which could be a source of confusion in future efforts with OH-PBDE congeners.

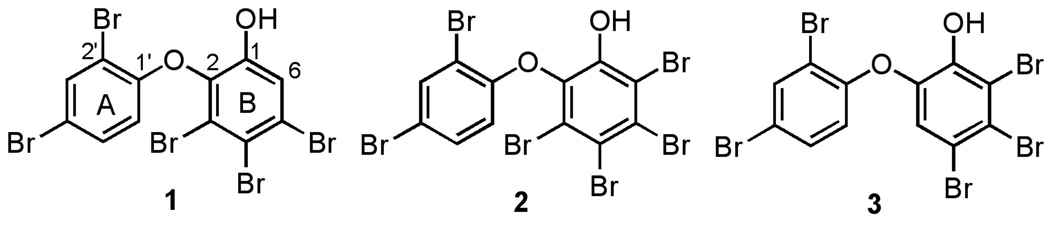

Figure 1.

OH-PBDE congeners isolated from the red alga/cyanobacteria assembly (1 and 2) and an alternative regioisomer of 1 (3).

Materials and Methods

2.1 Reagents and algal material

All solvents used were of HPLC grade from EMD and were used without purification. TLC grade silica gel from Sigma-Aldrich was used for vacuum liquid chromatography (VLC). Flash chromatography was performed using EMD silica gel (230–400 mesh). Trypsin, penicillin, streptomycin, heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum, horse serum and soybean trypsin inhibitor were obtained from Atlanta Biologicals. Minimum essential medium, deoxyribonuclease (DNase), poly-L-lysine, cytosine arabinoside, veratridine, aconitine, and deltamethrin were from Sigma-Aldrich. The fluorescent dye Fluo-3, and pluronic acid F-127 were obtained from Invitrogen Corporation.

Algal material was collected at Grabo Reef in Papua New Guinea (5° 28.664 S by 150° 12.524 E) at 12–18 m depth by SCUBA on August 24, 2000 (voucher specimen available as PNG-GR 8/24/00-3). The algae was identified in the field as Vidalia sp., but subsequent microscopic examination of the voucher sample identified it to likely be Leptofaucia sp. Additionally, a small abundance of cyanobacterial filaments similar to Oscillatoria were observed in the sample by light microscopy.

2.2 Bioassay-guided isolation of OH-PBDEs

A total of 2 L of the red algal and cyanobacterial assemblage (dry weight 128 g) was extracted with CH2Cl2 / MeOH (2:1). Upon removal of the solvents in vacuo, a portion (4.0 g) of the crude extract (4.6 g) was fractionated into nine fractions using silica gel vacuum liquid chromatography (hexanes to EtOAc to MeOH), one of which (308 mg, eluted with 2:3 EtOAc/hexanes) possessed Ca2+ modulating activity in mouse neocortical neurons. A portion (306 mg) of the active fraction was further fractionated by flash column chromatography (Still et al, 1978) on silica gel (hexanes/Et2O 1:9 to 1:8) to obtain seven sub-fractions, of which two (2 mg and 77 mg) were associated with Ca2+ modulation activity. The larger sub-fraction was further purified by HPLC using a Jupiter 10µ C18 300A column (250 × 10 mm) with a gradient solvent system (2.5 mL/min, 3:2 MeCN/H2O to 4:1 over 30 min, then to MeCN over 10 min) to obtain 15 mg (0.38% of extract) of compound 1 (Rt = 52 min) and ~0.5 mg (0.01% of extract) of compound 2 (Rt = 55 min), both of which were confirmed to elevate neuronal [Ca2+]i.

2.3 Neocortical neuron cultures

Primary cultures of neocortical neurons were obtained from embryonic day 16 Swiss-Webster mice. Briefly, pregnant mice were euthanized by CO2 asphyxiation and their neocortices were collected. Isolated neocortices were then removed of their meninges, minced by trituration using a Pasteur pipette, and treated with trypsin for 25 minutes at 37°C. The cells were then dissociated by two successive trituration and sedimentation steps in soybean trypsin inhibitor and DNase containing isolation buffer, centrifuged and resuspended in Eagle’s minimal essential medium (MEM) supplemented with 2 mM L-glutamine, 10% fetal bovine serum, 10% horse serum, 100 IU/mL penicillin and 0.10 mg/mL streptomycin, pH 7.4. Cells were plated onto poly-L-lysine-coated 96-well clear-bottomed black-well plate at a density of 1.5 × 105 cells/well. Plates were incubated at 37°C with 5% CO2 and 95% humidity. To prevent proliferation of nonneuronal cells, cytosine arabinoside (10 µM) was added to the culture medium on day 2 after plating. The culture media was changed both on days 5, 8 and 11 using a serum-free growth medium containing Neurobasal Medium supplemented with B-27, 100 I.U./mL penicillin, 0.10 mg/mL streptomycin, and 0.2 mM L-glutamine. Neocortical neurons were used between 11–13 days in vitro (DIV) for Ca2+ influx assay. All animal use protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC).

2.4 Neuronal [Ca2+]i assay

Neocortical neurons were cultured in 96-well plates, and subsequently, the medium was removed and replaced with dye loading buffer (100 µL/well) containing 4 µM Fluo-3 and 0.04% Pluronic F-127 in Lock’s buffer (in mM: 8.6 Hepes, 5.6 KCl, 154 NaCl, 5.6 Glucose, 1.0 MgCl2, 2.3 CaCl2, 0.0001 glycine, pH 7.4). After 1 h incubation in dye loading buffer, cells were washed five times with Locke’s buffer using automated cell washer (Bioteck instrument Inc., VT, USA) leaving a final volume of 150 µL in each well. The plate was then transferred to Fluorescence Laser Plate Reader (FLIPR) (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA, USA) chamber. Cells were excited by the 488-nm line of argon laser and Ca2+ bound fluo-3 emission in the 500–600 nm range was recorded with the charge coupled device (CCD) camera. Fluorescence readings were taken once every 9 s for 3 min to establish the baseline and then 50 µL of test compound containing solution (4x) was added to each well from the compound plate, yielding a final volume of 200 µL/well. The cells were exposed to test compounds for another 42 min.

2.5 Assay data analysis

Concentration-response relationships were generated by non-linear regression analysis using GraphPad software (Version 4.0; San Diego, CA).

2.6 Structure elucidation

All NMR data were collected in CDCl3 using Varian Inova 300 MHz and 500 MHz instruments. 1H and 13C NMR signals were referenced to the residual solvent peaks at 7.26 ppm and 77.0 ppm, respectively. High resolution mass spectra were recorded on a Thermo-Finnigan MAT900XL spectrometer. A crystal was grown from a CH2Cl2 solution of 1 by diffusional exchange with hexanes for X-ray crystallographic analysis on a Bruker APEX CCD detector.

2.7 Ichthyotoxicity assay

Various quantities of the natural product 1 in 174 µL of EtOH was added to 50 mL Erlenmeyer flasks containing 40 mL of aquarium water. For controls, 174 µL of EtOH was added to the water. Both treatments and controls were run in duplicate. Adult male zebra fish of approximately 4 cm length were randomly selected from aquaria and individually placed in the Erlenmeyer flasks. Time of death was determined by observing a lack of gill movement and no visible responses to swirling of the flask for one full minute.

Results and Discussion

Fractions from the crude lipid extract of a Papua New Guinea mixed collection of a red marine alga, tentatively identified as Leptofauchea sp. and a marine cyanobacterium Oscillatoria sp., showed an ability to increase [Ca2+]i in mouse neocortical neurons. Bioassay guided isolation of the active compounds sequentially used flash column chromatography and HPLC, and yielded one more prevalent (1) and one minor compound (3).

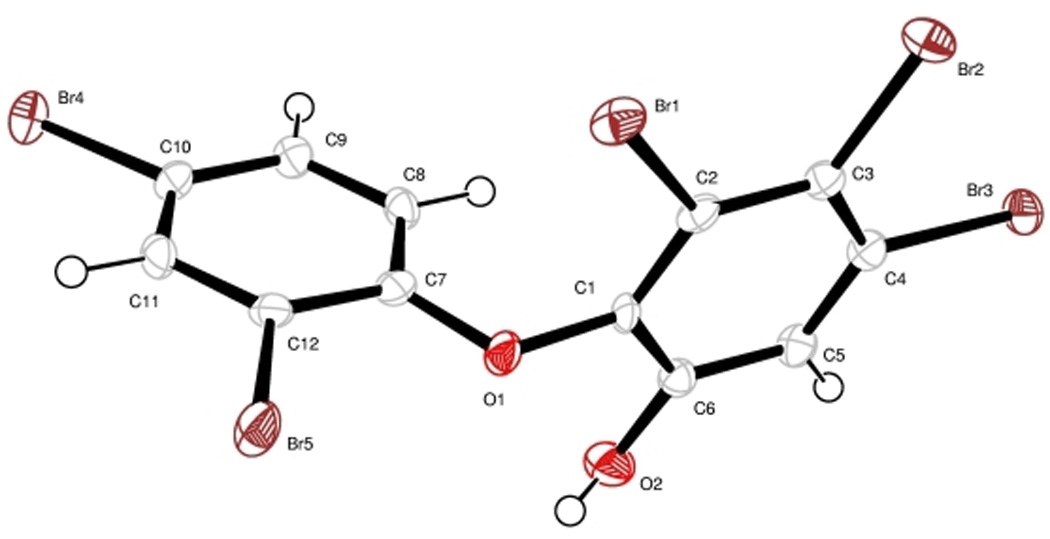

Analysis by ESI-LCMS (negative mode) revealed the polybrominated nature of compound 1 and indicated a molecular weight of 1160 (obs. [M−] m/z 1159). Subsequent analysis by 13C NMR showed 4 protonated and 8 quarternary 13C signals, indicating that the compound was either a symmetric dimer having a molecular weight of 1160 or that it was a monomer with a molecular weight of 580 that easily dimerizes in the mass spectrometer. High resolution EIMS clarified that it was a monomer with an exact mass of m/z 575.6211, yielding a molecular formula of C12H5O2Br5 (calc. 575.6201). 1H and 13C NMR, COSY, HSQC, and HMBC data readily identified two benzenoid rings connected to one another by an ether linkage. By 13C NMR chemical shifts and consideration of the molecular formula, one of the rings possessed 2 bromines while the other had 3 bromines and a hydroxyl group. Further analysis of the HMBC spectrum revealed the A ring to be a 2,4-dibromo-phenoxyl group. The regiochemical assignment of the B ring, however, could not be made confidently based on NMR data alone. Further, the 13C NMR data for 1 did not match that reported for any known OH-PBDE. Because 1 deposited well-formed crystals from CH2Cl2/hexanes, an X-ray crystallographic analysis was conducted to give an excellent quality crystal structure (Figure 2). Comparison of this structure with the literature for naturally occurring OH-PBDEs showed it to be identical to one previously reported from Dysidea herbacea (Bowden et al, 2000; Agrawal and Bowden, 2005).

Figure 2.

X-ray crystal structure of 1.

In comparing our 13C NMR data to those reported in the literature for compound 1, a significant discrepancy was noted in the chemical shift for C-3 (Table 1). Only the Bowden data are included in this table because the only other 13C NMR data available were recorded in DMSO and not in CDCl3 (Fu and Schmitz, 1996), but they were similar to our data. One interpretation for this anomalous NMR data was that the previous workers had mis-assigned structure 1 to their material, and that it was in fact the data for another structure. Of the 59 possible regioisomers of 1, 50 could be eliminated based on the fact that the A ring of Bowden’s isolation of 1 clearly had three protons and the HMBC and COSY correlations were sufficient to confidently assign this sub-structure (e.g. ring A). Of the remaining 9 structural possibilities, two could be disregarded based on HMBC correlations observed by Bowden. Specifically, the lone proton on the B ring showed HMBC correlations to 4 carbons (Bowden et al., 2000), and thus, the only carbon for which there was not an HMBC correlation should be para to the carbon bearing this proton. Based on the predicted chemical shifts of the oxygen bearing carbons, six other isomers could be disregarded (see Supporting Information), leaving only a single regioisomer that required further consideration (3). Regioisomer 3 is also a known naturally occurring compound having also been isolated from the marine sponge Dysidea herbacea (Carte and Faulkner, 1981).

Table 1.

Comparison of NMR data for two isolates of 1 and 3 (CDCl3)

| 1a | 1b | 3 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Position | 13C | 1H | 13C | 1H | 13C | 1H |

| 1 | 148.9 | 148.9 | 144.5 | |||

| 2 | 139.9 | 139.5 | 143.1 | |||

| 3 | 113.6 | 121.1 | 120.7 | 7.00 | ||

| 4 | 119.3 | 119.2 | 114.9 | |||

| 5 | 122.9 | 122.9 | 122.4 | |||

| 6 | 120.8 | 7.42 | 120.7 | 7.44 | 121.5 | |

| 1' | 151.8 | 151.7 | 151.3 | |||

| 2' | 112.8 | 112.7 | 115.6 | |||

| 3' | 136.4 | 7.79 | 136.3 | 7.79 | 136.5 | 7.81 |

| 4' | 116.3 | 116.2 | 118.4 | |||

| 5' | 131.6 | 7.29 | 131.6 | 7.29 | 132.1 | 7.45 |

| 6' | 115.8 | 6.41 | 115.7 | 6.41 | 121.5 | 6.89 |

This study.

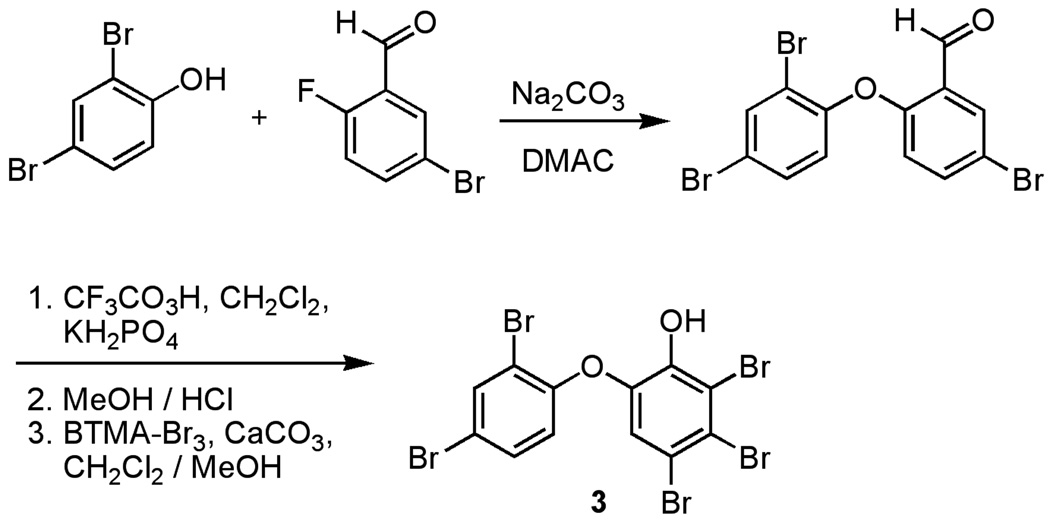

Unfortunately, because the 13C NMR data for 3 in CDCl3 had not been published (Carte and Faulkner, 1981), this compound was newly synthesized by Marsh's route (Figure 3; Marsh et al., 2003). Comparison of the 13C NMR shifts of synthetic 3 with those reported by Bowden revealed that they were considerably different (Table 1). Subsequently, a close inspection of the 13C NMR spectrum from the Bowden material revealed a small peak at 121.1 ppm (B. F. Bowden, personal communication), which corresponds well with our data for C-3 in compound 1. Because C-3 is para to the only protonated carbon in ring B, this 13C atom is predicted to relax slowly such that its detection may require longer delay times (Crews et al., 1998). Moreover, during our purification of 1–3, we found that it was difficult to remove minor contaminants that had similar NMR signatures to these OH-PBDEs. In this regard, it is possible that the 113.6 ppm signal reported for C-3 by Bowden et al. was actually the quickly relaxing (e.g. protonated) resonance of a minor contaminant in the sample. Additionally, during the preparation of this manuscript, a new isolation of compound 1 was reported and the discrepancy in the 13C NMR chemical shift of C-3 was also briefly noted (Calcul et al, 2009).

Figure 3.

Synthesis of 3 by Marsh’s route.

Having unequivocally established the structure of 1, a minor compound was also characterized that eluted very closely to 1 by RP-HPLC and showed Ca2+ modulating activity. A molecular formula of C12H4O2Br6 was determined for compound 2 based on low resolution negative ion ESI-LCMS (obs. [M-H]− m/z 658.74). The isotopic pattern observed for the molecular ion was consistent with the presence of 6 bromine atoms. Although NMR characterization of this compound was challenging due to the small quantity isolated (~0.5 mg) and the presence of chromatographically similar impurities, 1H NMR and 1H-1H COSY analysis revealed a three proton spin system consisting of a vicinally coupled pair (7.29 ppm and 6.39 ppm) and a third (7.79 ppm) which was meta coupled to δ 7.29. These shifts and coupling pattern matched those reported for synthetic 2 and thus, this material was identified as 3,4,5,6-tetrabromo-2-(2',4'-dibromo-phenoxy)-phenol (2).

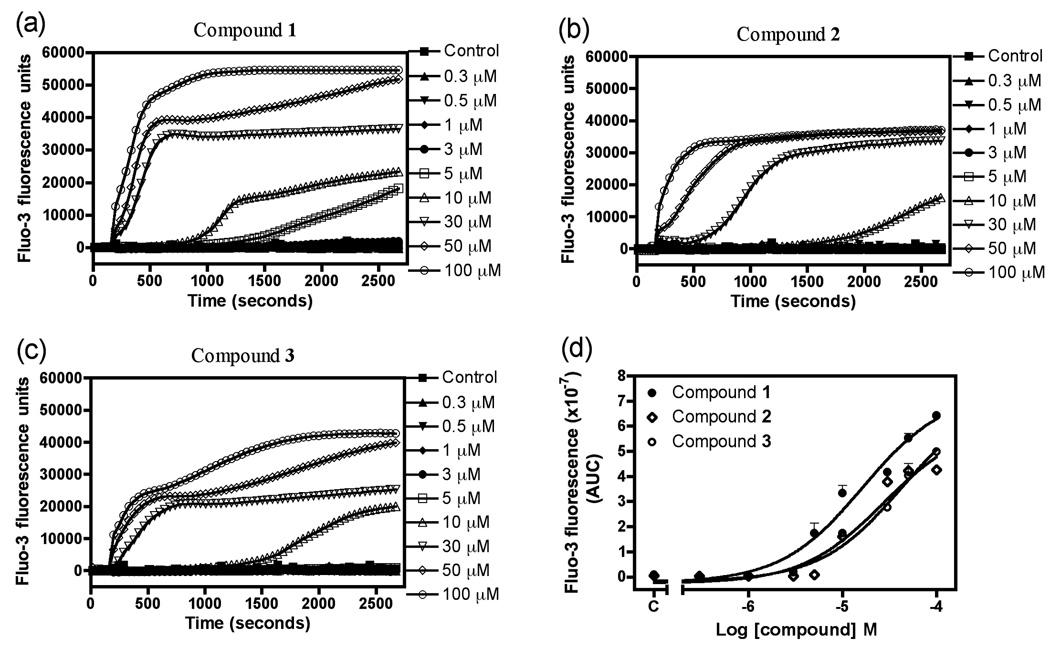

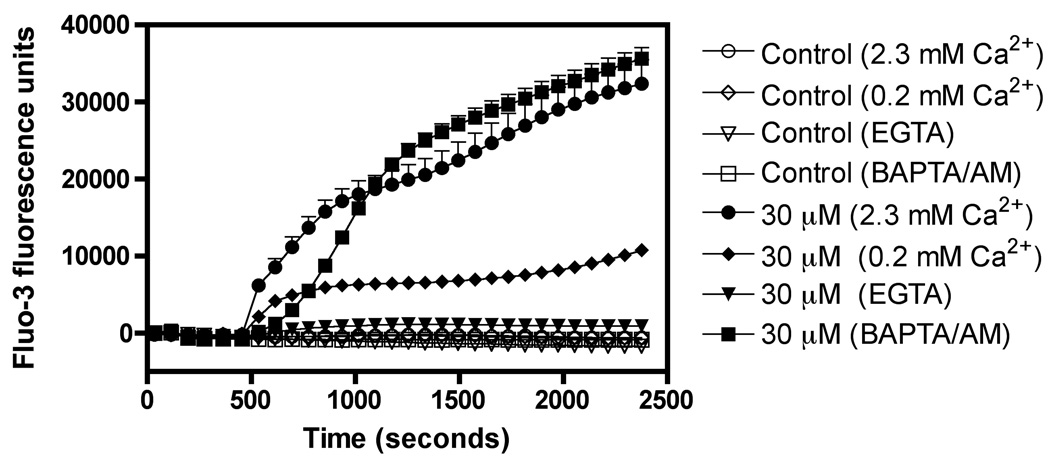

Compounds 1–3 were tested in the cytoplasmic [Ca2+]i assay in mouse neocortical neurons at various concentrations. Exposure to compounds 1–3 evoked a rapid, robust and concentration-dependent elevation of neuronal [Ca2+]i , and their corresponding EC50 values were 16.4 µM (9.8 – 27.2, 95% confidence intervals), 27.2 µM (12.3 – 59.8, 95% confidence intervals) and 42.4 µM (23.2 – 77.5, 95% confidence intervals), respectively (Figure 4). The robust nature of the increment in Fluo-3 fluorescence is of similar magnitude to that previously reported for brevetoxin, and represents peak [Ca2+]i values in the micromolar range (Berman and Murray, 2000). We have previously shown that marine natural products such as brevetoxin and antillatoxin produce Ca2+ entry in neurons from the extracellular compartment through three routes: the NMDA receptor ion channel, the L-type voltage-sensitive Ca2+ channel, and the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger (Berman and Murray, 2000; Li et al., 2001). It was therefore of interest to establish the source of the elevation in cytoplasmic Ca2+ produced by 1. To define the roles of extra- and intra-celluar Ca2+ pools, we exposed neocortical neurons to 30 µM 1 in the presence of both Ca2+ free and low Ca2+ extracellular media. The Ca2+ response to 1 was abrogated in the presence of Ca2+ free buffer containing 200 µM EGTA , and was significantly diminished in the low Ca2+ (0.2 mM) buffer (Figure 5). To confirm the importance of extracellular Ca2+ as the source of elevated [Ca2+]i in response to 1, we loaded the neocortical neurons with 50 µM BAPTA-AM, the acetoxymethylester of the calcium chelator BAPTA. Depletion of intracellular Ca2+ with BAPTA-AM did not alter the maximum Ca2+ response produced by 30 µM 1. These data therefore indicate that 1 produces an influx of Ca2+ from the extracellular compartment. Another polybrominated diphenyl ether and its hydroxylated analog have recently been shown to elevate cytoplasmic [Ca2+]i in PC12 cells (Dingemans et al, 2008). In PC12 cells the hydroxylated compound 6-OH-BDE-47 produced an initial increase in [Ca2+]i produced by Ca2+ influx and a delayed response derived from intracellular stores, primarily mitochondria. These results therefore differ from those reported herein for compound 1 in neocortical neurons where the source for elevated [Ca2+]i was exclusively extracellular. Either the use of PC12 versus neocortical neurons, or distinct actions of individual hydroxylated polybrominated diphenyl ethers, may be responsible for the differing results.

Figure 4.

Assay of changes in cytoplasmic Ca2+ concentration in mouse neocortical neurons for compounds 1–3. Time-response relationships for compound 1 (a), compound 2 (b) and compound 3 (c). The concentration-response relationships for compounds 1–3 are depicted in panel (d).

Figure 5.

Assay of changes in cytoplasmic Ca2+ concentration in mouse neocortical neurons for compounds 1 in control, low and calcium-free media.

In light of the finding that 1 may act as an environmental neurotoxin (Dingemans et al.,2008), its toxicity to zebrafish was also evaluated. At 5 µg/mL (8.6 µM) media concentration, the fish immediately attempted to escape out of the container and their apparent rate of respiration visibly increased; such behaviors were not observed for the control group. Within 5 minutes, the treated fish appeared to have difficulty maintaining their proper orientation, and within 20 minutes, both died. Similar effects were seen at 1 µg/mL (1.7 µM), but it took 50 min for the fish to expire. At 0.5 µg/mL (0.86 µM), the fish appeared to be unaffected for the duration of the 3 hour assay. Regioisomer 3 had the same effect but was less potent (8.6 µM, death at 25 min; no effect at 1.7 µM), suggesting that many congeners of OH-PBDEs may display ichthyotoxicity.

Both the long term and the short term neurotoxic effects of polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) have been studied extensively. Notably, PCBs disrupt the intracellular Ca2+ homeostasis, which is critical for a variety of cell functions, including release of neurotransmitters (Mariussen and Fonnum, 2006). As for the longer term effects, PCBs can modulate muscarinic and nicotinic receptors and also disrupt neurological development (Mariussen and Fonnum, 2006). Similarly, PBDEs have been shown to have detrimental effects to learning and memory functions in mice. These behavioral effects are likely related to the observation that PBDEs reduced the densities of nicotinic receptors in the hippocampus of mice (Viberg et al., 2003). Given the ability of 1, 2, and 3 to alter cytoplasmic concentrations of Ca+2 ions, the observed ichthyotoxicity of 1 and 2 may involve calcium ion induced neurotoxicity.

These findings are significant in light of recent reports that OH-PBDEs have wide-spread occurrence in the marine environment (Verreault et al., 2007; Kelly et al., 2008; McKinney et al., 2006a). In Disdea herbacea, at least 1~6% of the dry weight of the organism is composed of OH-PBDEs and visible crystals of these compounds have been observed in the sponge tissue (Unson et al., 1994). In addition to sponges, tunicates, and blue-green algae, we report here that a red alga and/or cyanobacterium living in association with the red alga as a source of OH-PBDEs (Malmvärn et al., 2005). Since most of the world's seaweeds are red algae (Garrison, 2005) and many invertebrates feed on these algae, the presence of OH-PBDEs in marine invertebrates may actually reflect the natural occurrence and bioaccumulation of these compounds into higher trophic levels. Among PBDEs, pentabrominated congeners are known to be environmentally more mobile due to their greater water solubility, volatility, Kow (octanol/water partition coefficient), and lipophilicity (Hale et al., 2003). OH-PBDEs are expected to be reasonably lipophilic and yet more water soluble than PBDEs. Therefore, they may be even more prone to bioaccumulation due to their increased mobility in the environment.

The possibility raised by these findings is that many OH-PBDEs are of natural occurrence and may possess neurotoxic properties of environmental significance. In this regard, it is possible that human populations have been exposed to these materials through seafood consumption for a lengthy period and that this exposure may have had historical as well as current health implications. PCBs and brominated flame retardants other than PBDEs are suspected to be responsible for abnormal behavior phenomena such as the ‘beaching of cetaceans’ (Symons et al., 2003; Law et al, 2006). Because of their structurally related nature, it is possible that OH-PBDEs of natural or anthropogenic origins may contribute to such events. Thus, it is important to both characterize the origin and occurrence of OH-PBDEs as well as details of their molecular neurotoxicology.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

X-ray crystallographic analysis by A. Rhinegold and A. DiPasquale at UCSD is acknowledged. We thank L. Tan and D. Sherman for help with collection of the algal material, B. F. Bowden for providing copies of their 13C NMR spectra of 1, and L. Gerwick for providing zebrafish. We further thank the government of Papua New Guinea for scientific collection permits and funding from NIH Grant NS 053398 is acknowledged.

Appendix

Selected microscopic photos of the voucher sample of the algae, 1H and 13C NMR, COSY, HSQC, and HMBC spectra of 1 and 3, 1H NMR and COSY spectra of 2, and X-ray crystallographic analysis data on 1. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://www.sciencedirect.com/.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

References

- Agrawal MS, Bowden BF. Marine sponge Dysidea herbacea revisited: another brominated diphenyl ether. Mar. Drugs. 2005;3:9–14. [Google Scholar]

- Athanasiadou M, Cuadra SN, Marsh G, Bergman Å, Jakobsson K. Polybrominated diphenyl ethers (PBDEs) and hydroxylated PBDE metabolites in young humans from Managua, Nicaragua. Environ. Health Perspect. 2008;116:400–408. doi: 10.1289/ehp.10713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berman FW, Murray TF. Brevetoxin-induced autocrine excitotoxicity is associated with manifold routes of Ca2+ influx. J. Neurochem. 2000;74:1443–1451. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2000.0741443.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betts KS. Science news: rapidly rising PBDE levels in North America. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2002;36:50A–52A. doi: 10.1021/es022197w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowden BF, Towerzey L, Junk PC. A new brominated diphenyl ether from the marine sponge. Dysidea herbacea. Aust. J. Chem. 2000;53:299–301. [Google Scholar]

- Calcul L, Chow R, Oliver AG, Tenney K, White KN, Wood AW, Fiorilla C, Crews P. NMR Strategy for unraveling structures of bioactive sponge-derived oxy-polyhalogenated diphenyl ethers. J. Nat. Prod. 2009;72:443–449. doi: 10.1021/np800737z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carte B, Faulkner DJ. Polybrominated diphenyl ethers from Dysidea herbacea, Dysidea chlorea and Phyllospongia foliascens. Tetrahedron. 1981;37:2335–2339. [Google Scholar]

- Carte B, Kernan MR, Barrabee EB, Faulkner DJ, Matsumoto GK, Clardy J. Metabolites of the nudibranch Chromodoris funerea and the singlet oxygen oxidation products of furodysin and furodysinin. J. Org. Chem. 1986;51:3528–3532. [Google Scholar]

- Crews P, Rodríguez J, Jaspars M. Organic Structure Analysis. Oxford: 1998. pp. 169–181. [Google Scholar]

- Dingemans MML, de Groot A, van Kleef RGDM, Bergman A, van den Berg M, Vijverberg HPM, Westerink RHS. Hydroxylation increases the neurotoxic potential of BDE-47 to affect exocytosis and calcium homeostasis in PC12 cells. Environ. Health Perspect. 2008;116:637–643. doi: 10.1289/ehp.11059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dingemans MML, Ramakers GMJ, Gardoni F, van Kleef RGDM, Bergman Å, Di Luca M, van den Berg M, Westerink RHS, Vijverberg HPM. Neonatal exposure to brominated flame retardant BDE-47 reduces long-term potentiation and postsynaptic protein levels in mouse hippocampus. Environ. Health Perspect. 2007;115:865–870. doi: 10.1289/ehp.9860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dravid SM, Murray TF. Fluorescent detection of Ca2+-permeable AMPA/kainate receptor activation in murine neocortical neurons. Neurosci. Lett. 2003;351:145–148. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2003.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu X, Schmitz FJ. New brominated diphenyl ether from an unindentified species of Dysidea sponge. 13C NMR data for some brominated diphenyl ethers. J. Nat. Prod. 1996;59:1102–1103. doi: 10.1021/np960542n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garrison T. Oceanography. 5th Ed. Brooks/Cole publisher; 2005. pp. 349–350. [Google Scholar]

- Hale RC, Alaee M, Manchester-Neesvig JB, Stapleton HM, Ikonomou MG. Polybrominated diphenyl ether flame retardants in the North American environment. Environ. Int. 2003;29:771–779. doi: 10.1016/S0160-4120(03)00113-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang H, Park E, Young TM, Hammock BD. Occurrence of endocrine-disrupting chemicals in indoor dust. Sci. Total Environ. 2008;404:26–35. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2008.05.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly BC, Ikonomou MG, Blair JD, Gobas FAPC. Hydroxylated and methoxylated polybrominated diphenyl ethers in a Canadian arctic marine food web. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2008;42:7069–7077. doi: 10.1021/es801275d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Law RJ, Allchin CR, deBoer J, Covaci A, Herzke D, Lepom P, Morris S, Tronczynski J, de Wit CA. Levels and trends of brominated flame retardants in the European environment. Chemosphere. 2006;64:187–208. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2005.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li WI, Berman FW, Okino T, Yokokawa F, Shioiri T, Gerwick WH, Murray TF. Antillatoxin is a novel marine cyanobacterial toxin that potently activates voltage-gated sodium channels. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2001;98:7599–7604. doi: 10.1073/pnas.121085898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malmberg T, Athanasiadou M, Marsh G, Brandt I, Bergman Å. Identification of hydroxylated polybrominated diphenyl ether metabolites in blood plasma from polybrominated diphenyl ether exposed rats. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2005;39:5342–5348. doi: 10.1021/es050574+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malmvärn A, Marsh G, Kautsky L, Athanasiadou M, Bergman Å, Asplund L. Hydroxylated and methoxylated brominated diphenyl ethers in the red algae Ceramium tenuicorne and blue mussels from the Baltic Sea. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2005;39:2990–2997. doi: 10.1021/es0482886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mariussen E, Fonnum F. Neurochemical targets and behavioral effects of organohalogen compounds: an update. Crit. Rev. Toxicol. 2006;36:253–289. doi: 10.1080/10408440500534164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsh G, Athanasiadou M, Athanassiadis I, Bergman Å, Endo T, Haraguchi K. Identification, quantification, and synthesis of a novel dimethoxylated polybrominated biphenyl in marine mammals caught off the coast of Japan. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2005;39:8684–8690. doi: 10.1021/es051153v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsh G, Athanasiadou M, Athanassiadis I, Sandholm S. Identification of hydroxylated metabolites in 2,2',4,4'-tetrabromodiphenyl ether exposed rats. Chemosphere. 2006;63:690–697. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2005.07.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsh G, Stenutz R, Bergman Å. Synthesis of hydroxylated and methoxylated polybrominated diphenyl ethers – natural products and potential polybrominated diphenyl ether metabolites. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2003:2566–2576. [Google Scholar]

- McKinney MA, Cesh LS, Elliott JE, Williams TD, Garcelon DK, Letcher RJ. Brominated flame retardants and halogenated phenolic compounds in North American West Coast bald eaglet (Haliaeetus leucocephalus) plasma. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2006a;40:6275–6281. doi: 10.1021/es061061l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKinney MA, De Guise S, Martineau D, Beland P, Lebeuf M, Letcher RJ. Organohalogen contaminants and metabolites in beluga whale (Delphinapterus leucas) liver from two canadian populations. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2006b;25:1246–1257. doi: 10.1897/05-284r.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers KL, Fong WF, Redburn J, Griffiths LR. Fluorescence detection of plant extracts that affect neuronal voltage-gated Ca2+ channels. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2002;15:321–330. doi: 10.1016/s0928-0987(02)00012-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Still WC, Khan M, Mitra A. Rapid chromatographic technique for preparative separations with moderate resolution. J. Org. Chem. 1978;43:2923–2925. [Google Scholar]

- Symons RK, Burniston D, Jaber R, Piro N, Trout M, Yates A, Gales R, Terauds A, Pemberton D, Robertson D. Southern hemisphere cetaceans. A study of the POPs PCDDs/PCDFs and dioxin-like PCBs in stranded animals from the Tasmanian coast. Organohalogen Compounds. 2003;62:257–260. [Google Scholar]

- Unson MD, Holland ND, Faulkner DJ. A brominated secondary metabolite synthesized by the cyanobacterial symbiont of a marine sponge and accumulation of the crystalline metabolite in the sponge tissue. Mar. Biol. 1994;119:1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Verreault J, Gebbink WA, Gauthier LT, Gabrielsen GW, Letcher RJ. Brominated flame retardants in glaucous gulls from the Norwegian Arctic: more than just an issue of polybrominated diphenyl ethers. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2007;41:4925–4931. doi: 10.1021/es070522f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viberg H, Fredriksson A, Eriksson P. Neonatal exposure to polybrominated diphenyl ether (PBDE 153) disrupts spontaneous behaviour, impairs learning and memory, and decreases hippocampal cholinergic receptors in adult mice. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2003;192:95–106. doi: 10.1016/s0041-008x(03)00217-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vos JG, Becher G, van den Berg M, de Boer J, Leonards PEG. Brominated flame retardants and endocrine disruption. Pure Appl. Chem. 2003;75:2039–2046. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.