Abstract

Activation of the prophenoloxidase (proPO) system and synthesis of antimicrobial peptides (including lysozyme) are two key defense mechanisms in arthropods. Activation of proPO involves a cascade of serine proteinases that eventually converts proPO to active phenoloxidase (PO). However, a trade-off between lysozyme/antibacterial activity and PO activity has been observed in some insects, and a mosquito lysozyme can inhibit melanization. It is not clear whether lysozyme can inhibit PO activity and/or proPO activation. In this study, we used in vitro assays to investigate the role of lysozyme in proPO activation in the tobacco hornworm Manduca sexta. We showed that lysozymes from M. sexta, human milk and hen egg white did not inhibit PO activity in the pre-activated naïve plasma of M. sexta larvae, but significantly inhibited proPO activation in the naïve plasma. Western blot analysis showed that direct incubation of M. sexta lysozyme with the naïve plasma prevented conversion of proPO to PO, but stimulated degradation of precursor proteins for serine proteinase homolog-2 (SPH2) and proPO-activating proteinase-1 (PAP1), two key components required for proPO activation. Far-western blot analysis showed that M. sexta lysozyme and proPO interacted with each other. Altogether, our results suggest that lysozymes may inhibit the proPO activation system by preventing conversion of proPO to PO via direct protein interaction with proPO.

Keywords: Lysozyme, prophenoloxidase, phenoloxidase, serine proteinase homolog, prophenoloxidase-activating proteinase, melanization, serine proteinases, Manduca sexta

1. Introduction

In invertebrates, the innate immune system is crucial for combating microbial infection since they lack an adaptive immune system [1–6]. Invertebrate innate immune system is composed of both cellular and humoral immune responses. Blood cells (hemocytes)-mediated immune responses such as phagocytosis, nodule formation and melanotic encapsulation are major cellular responses, whereas synthesis of antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) and activation of the prophenoloxidase system are important components of humoral responses [1–3, 6–12]. Phenoloxidase (PO) is a key enzyme in the melanization response, which is effective against pathogens, particularly parasites and parasitoid eggs [1, 3, 13, 14,]. PO is activated from its pro-enzyme (zymogen), prophenoloxidase (proPO), and the activation process involves a cascade of serine proteinases with similarities to the mammalian complement cascade [7, 10]. ProPO is cleaved by proPO-activating proteinases (PAPs) that are also present as pro-enzymes in hemolymph [15–20].

ProPO activation can be triggered by microbial cell wall components such as β-1, 3-glucans, lipopolysaccharide (LPS), and peptidoglycan [18, 20–24]. These microbial components can also activate expression of AMPs (including lysozyme) [5, 6]. For example, peptidoglycan can activate the expression of AMPs and the proPO cascade in Drosophila [20, 25–28]. Although melanization response can kill pathogens, systematic melanization is harmful to the host [29, 30]. Therefore, proPO activation must be tightly regulated. The proPO activation and melanization processes can be positively and negatively regulated and modulated by serpins (serine proteinase inhibitors) [31–34], serine proteinase homologs (SPHs) [35–38], PO inhibitors [39], melanization inhibitor [40], C-type lectins [21, 22], and some other proteins [41, 42].

Lysozyme (EC 3.2.1.17) is a lytic enzyme (muramidase) that plays an important role in the immune system of both vertebrates and invertebrates [43, 44]. It can catalyze hydrolysis of a beta-1, 4 glycosidic bond between N-acetylmuramic acid and N-acetyl-D-glucosamine (GlcNAc) in peptidoglycan of bacterial cell wall, and kill microbial cells via both lytic and nonlytic mechanisms [45–47]. In insects, lysozyme plays a role in activation of both the Toll pathway and the proPO system by cleavage of lysine-type peptidoglycan from Gram-positive bacteria for clustering of peptidoglycan-recognition protein (PGRP)-SA [27]. However, a trade-off between lysozyme/antibacterial activity and PO activity has been observed in some insect species [48–50]. Also, a lysozyme from the mosquito Anopheles gambiae is identified around the non-melanized Sephadex CM beads injected into the susceptible mosquitoes, and knock-down of the lysozyme expression by RNA interference (RNAi) results in a significant increase in melanization of the injected beads [51]. Thus, it is not clear what role lysozyme may play in the proPO activation cascade.

In the tobacco hornworm Manduca sexta, proPO activation can be triggered by microbial components leading to activation of three PAPs (PAP-1, -2, and -3) that can convert proPO to active PO. However, proPO activation also requires the presence of essential co-factors, serine proteinase homologs (SPHs) [36, 52]. In order to investigate the role of lysozyme in the proPO activation cascade, we used in vitro assays with naïve plasma samples from M. sexta larvae in this study. We showed that lysozymes from M. sexta, human milk and hen egg white did not inhibit PO activity in the pre-activated naïve plasma of M. sexta larvae, but significantly inhibited proPO activation in the naïve plasma. We also showed that direct incubation of M. sexta lysozyme with the naïve plasma inhibited conversion of proPO to active PO, but stimulated degradation of precursor proteins for SPH2 and PAP1. Far-western blot analysis showed that M. sexta lysozyme and proPO interacted with each other. Altogether, our results suggest that lysozymes may inhibit the proPO activation system by preventing conversion of proPO to PO via direct protein interaction with proPO.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Insects and collection of hemolymph

M. sexta eggs were kindly provided by Dr. Michael Kanost, Department of Biochemistry at Kansas State University. Larvae were reared on an artificial diet at 25°C [53]. The fifth instar larvae were used for the experiments.

Hemolymph from individual naïve larvae was collected separately into microtubes on ice, and hemocytes were removed by centrifugation at 3,300 g for 5 min at 4°C. Individual cell-free plasma samples were then stored at −80°C for proPO activation assay.

2.2. In vitro prophenoloxidase activation assays

Naïve plasma samples were first screened for proPO activation assay as described previously [41]. Plasma samples, which have low or no PO activity when incubated alone but high PO activity after incubation with Micrococcus luteus, were selected for proPO activation assays.

M. sexta lysozyme was purified from LPS-induced hemolymph by a combination of several chromatography columns as described previously [41]. The mass of M. sexta lysozyme was determined by MALDI-TOF at the Biological Mass Spectrometry and Proteomics Facility, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Human milk and hen egg white lysozymes were purchased from Sigma. Individual naïve plasma samples #15, #31 and #38 were used for the following proPO activation assays.

For PO activity assay, proPO in the naïve plasma sample #15 (2µL each) was pre-activated with laminarin (a beta-1, 3-glucan) (0.4 µg each) in a total of 10µL Tris-Ca2+ buffer (100mM Tris-HCl, 100mM NaCl, 1 mM CaCl2, pH 7.5) in wells of a 96-well microtiter plate at room temperature, then BSA, M. sexta, human milk or hen egg white lysozyme (each protein at 0.5 µg) was added and the mixture was incubated for 30 min at room temperature. For proPO activation assays, naïve plasma sample #38 (2µL each) was directly incubated with buffer, BSA, M. sexta, human milk or hen egg white lysozyme (each protein at 0.5 µg) in 10µL Tris-Ca2+ buffer in wells of a 96-well microtiter plate for 50 min at room temperature. Individual naïve plasma sample #31 (2µL each) was also directly incubated with buffer, BSA, M. sexta lysozyme, M. sexta cationic protein CP8 [41], M. sexta lysozyme/CP8, or M. sexta lysozyme/BSA (each protein at 0.5 µg) in 10μL Tris-Ca2+ buffer in wells of a 96-well microtiter plate for 25 min at room temperature. For lysozyme dose-dependent assay, individual naïve plasma sample #38 (2µL each) was directly incubated with BSA, M. sexta, human milk or hen egg white lysozyme (each protein at 0.1 or 0.5 µg) in 10µL Tris-Ca2+ buffer in wells of a 96-well microtiter plate for 60 min at room temperature. Finally, L-dopamine substrate solution (2mM in 50 mM phosphate buffer, pH 6.5) was added (200 µL per well), and absorbance at 470nm was monitored immediately with time in a microtiter plate reader (PowerWave XS, Bio-Tek Instrument, Inc.). One unit of PO activity is defined as an increase of absorbance (ΔA470) by 0.001 per min. Data from four replicas of each sample were analyzed. These experiments were repeated three times and similar results were obtained.

2.3. Cleavage of proPO and precursor proteins of SPHs and PAP1 in naïve plasma in the presence of exogenous lysozyme

Naïve plasma sample #38 (20µL) was directly incubated with BSA or M. sexta lysozyme (each protein at 5 µg) in a total of 100µL Tris-Ca2+ buffer in a microtube for 50 min at room temperature, then equal volume of 2×SDS loading buffer was added to each tube. The mixture was heated to 95°C for 5min and aliquots (10 µL, an equivalent of 1µL original plasma) were analyzed by 6%, 10%, 12% or 15% SDS-PAGE. Proteins in the gel were stained with Coomassie Brilliant Blue or transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. M. sexta lysozyme, SPHs, proPO/PO and PAP1 were identified by immunoblotting using rabbit polyclonal antibody to each protein. Naïve plasma samples #31, #32 and #38, two bacteria-induced plasma samples (1 µL each) and purified M. sexta lysozyme (0.2 and 0.4 µg) were also analyzed by 15% SDS-PAGE, and lysozyme was identified by immunoblotting with rabbit polyclonal antibody to M. sexta lysozyme.

2.4. Interaction of M. sexta lysozyme with prophenoloxidase

Far-western blot was performed according to the method of Einarson and Orlinick [54]. Purified M. sexta lysozyme (0.3 µg), M. sexta proPO (0.3 µg) and M. sexta hemolin (0.2 µg) were separated in 12% SDS-PAGE and proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. One set of membranes was used for direct immunoblotting using rabbit polyclonal antibody to M. sexta proPO, lysozyme, or hemolin as described below, and the other set of membranes was used for far-western blot analysis. For far-western blot, the membranes were washed in Tris-buffered saline (TBS) (50 mM Tris-HCl, 100 mM NaCl, pH7.5) containing 0.05% Tween-20 (TBS-T) for 1 h with a buffer change every 20 min to remove SDS, blocked with 5% dry skim milk in TBS-T for 1h, and then probed with purified M. sexta proPO (0.4µg/mL), M. sexta lysozyme (0.8µg/mL) or hemolin (0.4 µg/mL) in TBS-T containing 0.1% BSA, pH9.0, overnight at 4°C with a gentle rocking. The membranes were then washed with TBS-T 3 times, each for 5 min, and then rabbit polyclonal antibody to M. sexta proPO, lysozyme or hemolin was used as the primary antibody to detect protein interactions using the procedures the same as described for direct immunoblotting (see below).

2.5. Lysozyme activity assay

M. sexta or human milk lysozyme (0.5µg) was pre-incubated with M. sexta proPO, recombinant immulectin-3 (IML-3) [55] or CP36 [56] (control), or ovalbumin (each protein at 0, 0.5, or 2.5µg) in 10µL of 0.1M potassium phosphate buffer, pH6.4 in wells of a 96-well plate for 30min at room temperature. Then M. luteus suspension (500µg/mL, 190µL per well) was added and the plate was incubated at room temperature for another 30 min. Finally, absorbance at 595nm was monitored with time in a microtiter plate reader (PowerWave XS, Bio-Tek Instrument, Inc.). One unit of enzyme activity is defined as a decrease of absorbance (ΔA595) by 0.001 per min. Data from 3 replicas of each sample were analyzed. These experiments were repeated 3 times and similar results were obtained.

2.6. Immunoblotting analysis

Plasma samples or purified proteins were analyzed by SDS-PAGE by the method of Laemmli [57], and the proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. The membranes were blocked with 5% dry skim milk in TBS-T and incubated with the primary rabbit polyclonal antibody (1:2000) specific to each protein. Antibody binding was visualized by a color reaction catalyzed by alkaline phosphatase conjugated to goat anti-rabbit IgG (1:3000) (Bio-Rad). Rabbit polyclonal antibodies to M. sexta proPO, M. sexta lysozyme and hemolin were kindly provided by Dr. Michael Kanost, Kansas State University, and rabbit antibody to M. sexta PAP1 and purified proPO samples were from Dr. Haobo Jiang, Oklahoma State University. Antibody to human lysozyme was purchased from Nordic Immunology (Netherland).

2.7. Data analysis

One representative set of data was used to make figures using the GraphPad Prism software, and the significance of difference was determined by an unpaired t-test using the GraphPad InStat software (GraphPad, San Diego, CA).

3. Results

3.1. Purification and identification of M. sexta Lysozyme

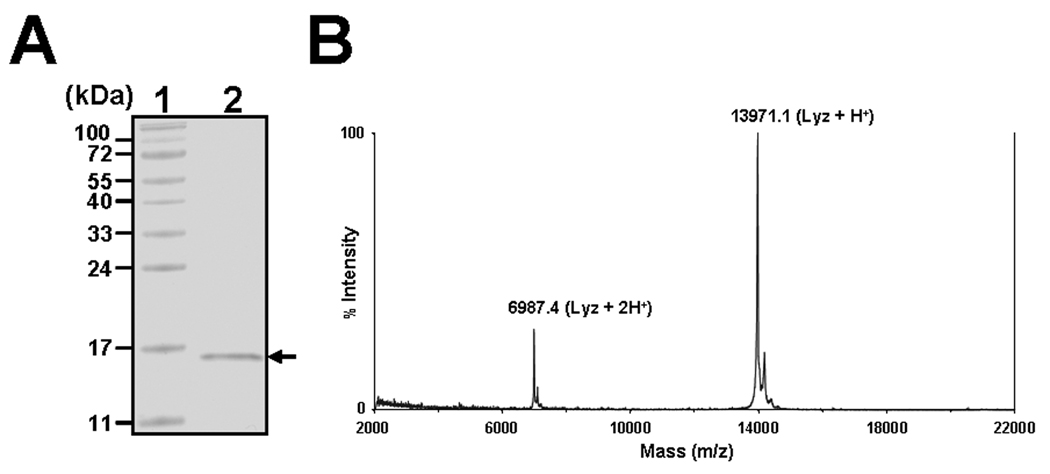

When we were purifying proteins from the hemolymph of M. sexta larvae that can interact with a C-type immulectin-3 (IML-3) [55], two proteins were purified from LPS-induced hemolymph: a 10-kDa small cationic protein CP8 [41] and a 14-kDa protein (Fig. 1A). The amino-terminal sequence of this purified 14-kDa protein was determined (KHFSRCELVHELRRQ), which perfectly matches the deduced amino acid sequence of M. sexta lysozyme (accession number: S70589). The 14-kDa protein was purified to homogeneity as it appeared as a single protein band in SDS-PAGE (Fig. 1A, lane 2). The mass of the 14-kDa protein was also determined by MALDI-TOF (Fig. 1B), and a single major peak of 13970.1 Da was observed, which matches the monoisotopic mass of 13974.7 Da for mature M. sexta lysozyme calculated from the deduced amino acid sequence. The purified 14-kDa protein was also recognized by antibody specific to M. sexta lysozyme (see Fig. 4B below). All these results indicate that the purified 14-kDa protein is M. sexta lysozyme, and it is purified to homogeneity.

Fig. 1. Purification and identification of M. sexta lysozyme.

M. sexta lysozyme was purified from the hemolymph of 5th instar larvae by several steps of chromatography as described previously [41]. The purified lysozyme (lane 2, 0.5 µg) was analyzed by SDS-PAGE and the gel was stained with Coomassie Brilliant Blue (A). Lane 1 is the protein markers, and the arrow indicates lysozyme. The mass of purified M. sexta lysozyme was also determined by mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF) (B).

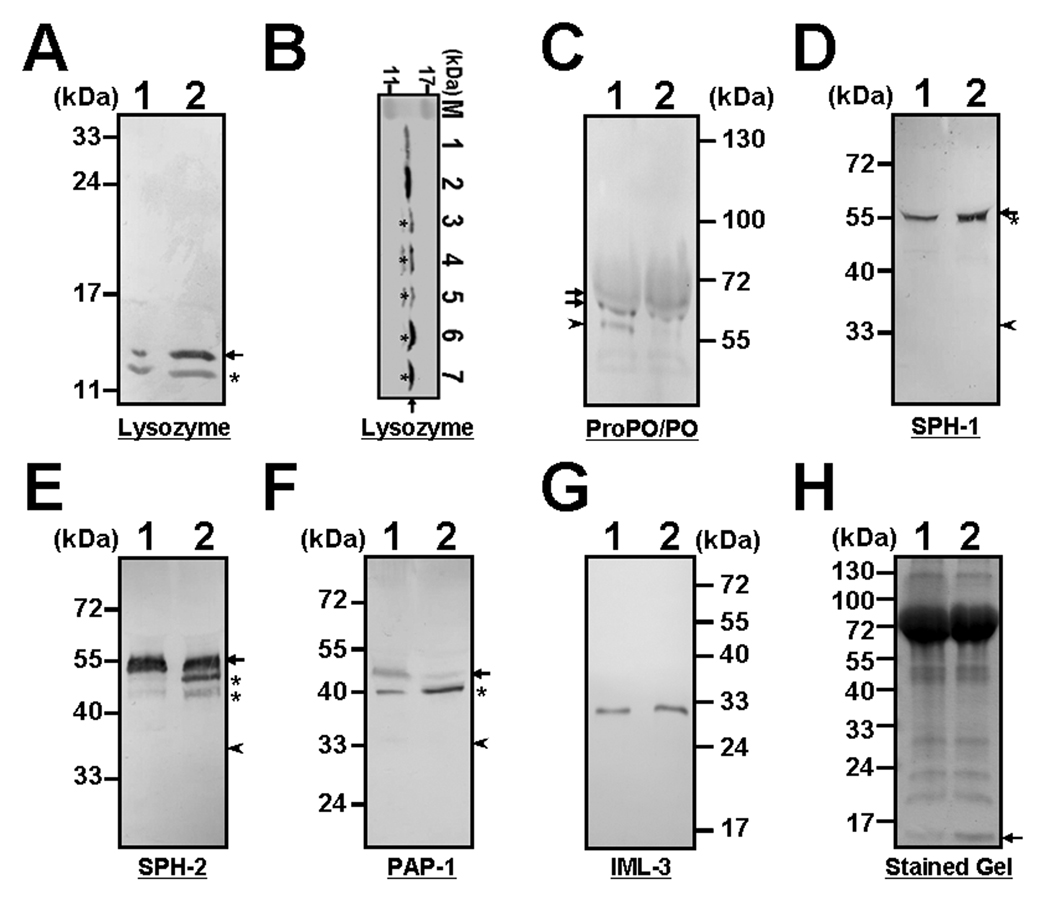

Fig. 4. M. sexta lysozyme prevents conversion of proPO to PO but stimulates degradation of precursor proteins for SPH-2 and PAP-1.

Individual naïve plasma (#38) was directly incubated with BSA or M. sexta lysozyme (20µL plasma with 5 µg protein in a total of 100µL with Tris-Ca2+ buffer) in a microtube for 50 min at room temperature, and then equal volume of 2×SDS loading buffer was added. The mixture was heated to 95°C for 5min and aliquots (10 µL, an equivalent of 1 µL original plasma) were analyzed by SDS-PAGE (15% PAGE in A and B, 6% in C, 12% in D–G, and 10% in H). Proteins were stained with Coomassie blue (H) or transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. M. sexta lysozyme, SPHs, proPO/PO, PAP1 and IML-3 were identified by immunoblotting using rabbit polyclonal antibody to each protein (A, C–G). Naïve plasma samples of #31, #32 and #38 from individual larvae (lanes 3–5, 1 µL each), bacteria-induced plasma samples (pooled samples, each from at least four larvae) (lanes 6 and 7, 1 µL each) and purified M. sexta lysozyme (lanes 1 and 2, 0.2 and 0.4 µg, respectively) were also analyzed by 15% SDS-PAGE, and M. sexta lysozyme was identified by immunoblotting (B). A, C–H: lane 1, naïve plasma with BSA; lane 2, naïve plasma with exogenous M. sexta lysozyme. Arrows indicate M. sexta lysozyme (A, B and H) or precursor proteins (proPO, proSPHs, and proPAP1) (C–F), arrowheads indicate the positions of active proteins (PO, SPHs, and PAP1) (C–F), and asterisks indicate degraded products of each protein (see text for detail).

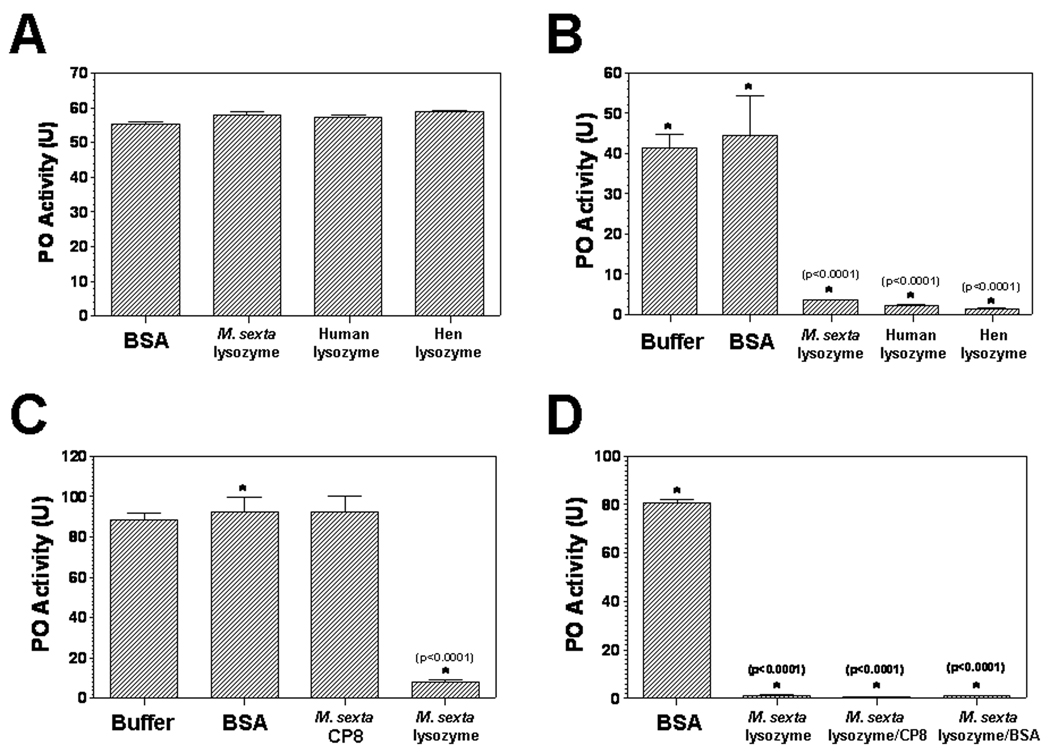

3.2. Lysozymes do not inhibit PO activity but inhibit proPO activation

It has been reported that a mosquito lysozyme deposited on the Sephadex beads prevents the beads from melanization [51], and there is a trade-off between lysozyme (or antibacterial) activity and PO activity [49, 50]. Thus, lysozymes may inhibit PO activity, proPO activation or conversion of proPO to PO. To test these possibilities, in vitro proPO activation assays were performed with M. sexta naïve plasma samples (Fig. 2 and Fig. 3). ProPO in the naïve plasma of M. sexta larvae can be easily activated by microbial components such as peptidoglycan and laminarin (a beta-1, 3-glucan), but it can also be activated without activators when incubated at room temperature for a period of time. Thus, we used laminarin pre-activated naïve plasma to test the effect of lysozymes on PO activity, and used direct incubation of lysozymes with naïve plasma to test the role of lysozymes in proPO activation. When M. sexta proPO in the naïve plasma sample (#15) was pre-activated with laminarin, similarly high PO activity was detected in all four groups of the naïve plasma samples containing BSA and three lysozymes from M. sexta, human milk and hen egg white (55.1, 57.9, 57.1 and 58.7 units, respectively) (Fig. 2A), suggesting that lysozymes do not inhibit PO activity. When naïve plasma sample (#38) was directly incubated with buffer, BSA or lysozymes, very low PO activity was observed in the naïve plasma samples containing the three lysozymes (3.6, 2.3 and 1.5 units, respectively), however, significantly higher PO activity was detected in the naïve plasma samples containing buffer and BSA (41.5 and 44.5 units, respectively) (Fig. 2B). Similarly, when naïve plasma sample (#31) was used for the proPO activation assay, low PO activity was observed in the naïve plasma samples containing M. sexta lysozyme, M. sexta lysozyme/CP8 and M. sexta lysozyme/BSA mixtures (0.6–7.9 units), while significantly higher PO activity was detected in the naïve plasma samples with buffer, BSA and CP8 (80.8–92.4 units) (Fig. 2C and 2D). M. sexta CP8 is a small cationic protein that can stimulate proPO activation in the plasma at the initial stage but does not increase PO activity after proPO is already activated [41]. Together, these results indicate that lysozymes do not inhibit PO activity but inhibit proPO activation.

Fig. 2. Lysozymes do not inhibit PO activity in the pre-activated naïve plasma but inhibit proPO activation in the naïve plasma.

(A): Aliquots (2µL each) of individual naïve plasma (#15) were pre-activated with laminarin (0.4 µg each) in 10µL Tris-Ca2+ buffer (100mM Tris-HCl, 100mM NaCl, 1 mM CaCl2, pH 7.5) in wells of a 96-well microtiter plate at room temperature, and then incubated with BSA, M. sexta, human milk or hen egg white lysozyme (each protein at 0.5 µg) for 30 min. (B): Aliquots (2µL each) of individual naïve plasma (#38) were directly incubated with buffer, BSA, M. sexta, human milk or hen egg white lysozyme (each protein at 0.5 µg) in 10µL Tris-Ca2+ buffer for 50 min at room temperature. (C) and (D): Aliquots (2µL each) of individual naïve plasma (#31) were directly incubated with buffer, BSA, M. sexta lysozyme, M. sexta cationic protein CP8 [41], M. sexta lysozyme/CP8, or M. sexta lysozyme/BSA mixture (each protein at 0.5 µg) in 10µL Tris-Ca2+ buffer for 25 min at room temperature. Finally, L-dopamine substrate solution (2mM in 50 mM phosphate buffer, pH 6.5, 200 µL per well) was added, and absorbance at 470nm was monitored immediately with time in a microtiter plate reader. Data from four replicas of each sample were analyzed, and the significance of difference was determined by an unpaired t-test using the GraphPad InStat software.

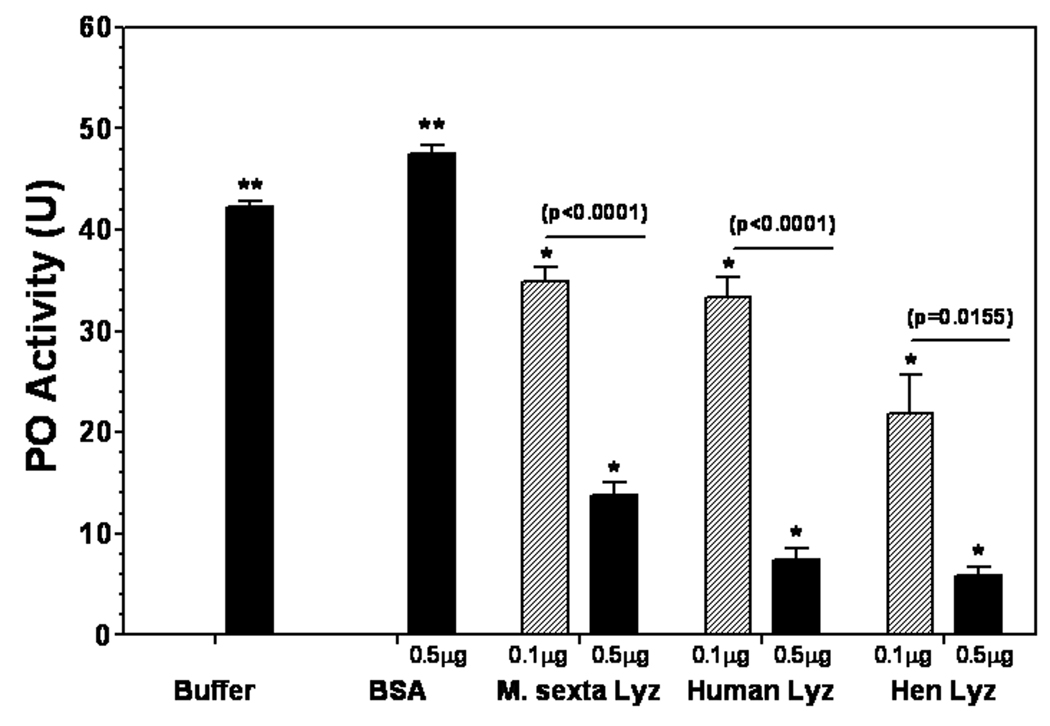

Fig. 3. Lysozymes inhibit proPO activation in a dose-dependent manner.

Aliquots (2µL each) of individual naïve plasma (#38) were directly incubated with buffer, BSA, M. sexta, human milk or hen egg white lysozyme (each protein at 0.1 or 0.5 µg) in 10µL Tris-Ca2+ buffer in wells of a 96-well microtiter plate for 60 min at room temperature. Then, L-dopamine substrate solution was added, and absorbance at 470nm was monitored immediately with time in a microtiter plate reader. Data from four replicas of each sample were analyzed, and the significance of difference was determined by an unpaired t-test using the GraphPad InStat software.

To further confirm that lysozymes can inhibit proPO activation, a dose-dependent assay was performed (Fig. 3). High PO activity was observed in the naïve plasma samples (#38) that were directly incubated with buffer and BSA (0.5 µg) (42.3 and 47.5 units, respectively), but significantly lower PO activity was observed in the naïve plasma samples with 0.5 µg lysozymes (13.8, 7.5 and 5.8 units, respectively) than with 0.1 µg lysozymes (35, 33.3 and 21.9 units, respectively) (Fig. 3) (incubation time was 10 min longer in Fig. 3 than in Fig. 2B). PO activity in all the naïve plasma samples containing lysozymes (regardless of 0.1 or 0.5 µg) was significantly (p<0.05) lower than that of the naïve plasma sample with buffer or BSA.

3.3. M. sexta lysozyme inhibits proPO activation by preventing conversion of proPO to PO

The proPO activation system is a complex process involving a cascade of serine proteinases [7, 10]. Conversion of proPO to PO is accomplished by proPO-activating proteinases (PAPs), and also requires serine proteinase homologs (SPHs) as essential co-factors to help PAPs properly cleave proPO to active PO [15–17, 36]. However, both PAPs and SPHs exist as pro-proteins in hemolymph and they also require proteolytic cleavage for activation. To test whether M. sexta lysozyme inhibits proPO activation by inhibiting activation of PAPs and/or SPHs, or by preventing conversion of proPO to PO, naïve plasma sample was directly incubated with M. sexta lysozyme or BSA, and aliquots of the plasma samples were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting (Fig. 4). A much stronger signal for M. sexta lysozyme was detected in the naïve plasma sample containing exogenous M. sexta lysozyme (Fig. 4A, lane 2) than in the control naïve plasma containing BSA (Fig. 4A, lane 1), indicating the presence of exogenous M. sexta lysozyme. A smaller protein at ~12-kDa (Fig. 4A, asterisks) was also recognized by rabbit polyclonal antibody to M. sexta lysozyme, and this protein is present in both the naïve (Fig. 4B, lanes 3–5, asterisks) and immune-challenged (Fig. 4B, lanes 6 and 7, asterisks) plasma samples but not in the purified M. sexta lysozyme (Fig. 4B, lanes 1 and 2), suggesting that it may be a cleavage product of M. sexta lysozyme. We also showed that the concentration of M. sexta lysozyme in the naïve plasma samples (Fig. 4B, lanes 3–5) was much less than in the immune-challenged plasma samples (Fig. 4B, lanes 6 and 7), and M. sexta lysozyme concentrations in the naïve plasma samples (Fig. 4B, lanes 3–5, 1µl each) used for the above proPO activation assays (Fig. 2 and Fig. 3) were less than 0.2 µg/µl (compared to 0.2µg purified M. sexta lysozyme in lane 1, Fig. 4B). We then perform immunoblotting for proPO/PO using the same naïve plasma with 6% SDS-PAGE and longer separation time. The results showed that both proPOs (proPO1 and proPO2) and PO were detected in the control naïve plasma sample containing BSA (Fig. 4C, lane 1), however, only proPOs, but almost no PO, were detected in the naïve plasma sample containing exogenous M. sexta lysozyme (Fig. 4C, lane 2) (arrows indicate M. sexta proPO1 and proPO2, arrowhead indicates PO). The proPOs and PO bands appeared smaller on the membrane than their actually sizes due to compression by the storage proteins in the naïve plasma (see Fig. 4H). Immunoblotting results for SPHs and PAP1 showed that addition of exogenous M. sexta lysozyme did not stimulate activation of SPH2 and PAP1 (Fig. 4E and F, arrowheads), but stimulated degradation of proSPH2 and proPAP1, as much stronger signals for cleavage products of proSPH2 and proPAP1 were detected in the naïve plasma sample containing M. sexta lysozyme than in the control naïve plasma with BSA (Fig. 4E and F, asterisks). Addition of M. sexta lysozyme also stimulated degradation of proSPH1, but to a less extent (Fig. 4D, asterisk). However, direct incubation of M. sexta lysozyme with naïve plasma did not cause degradation of plasma proteins such as IML-3 (Fig. 4G) and immulectin-2 (IML-2) (data not shown), and major plasma proteins (Fig. 4H). A stronger band smaller than 17kDa at the bottom of the stained gel (Fig. 4H, arrow) was observed in the plasma sample containing additional M. sexta lysozyme and this protein could be lysozyme as proven by western blot analysis (Fig. 4A). We did not detect serine proteinase activity in the purified M. sexta lysozyme (1 µg) with different synthetic peptide substrates (data not shown), suggesting that the purified M. sexta lysozyme was not contaminated with proteinases. These results suggest that M. sexta lysozyme may inhibit proPO activation by preventing conversion of proPO to PO.

3.4. M. sexta lysozyme interacts with proPO

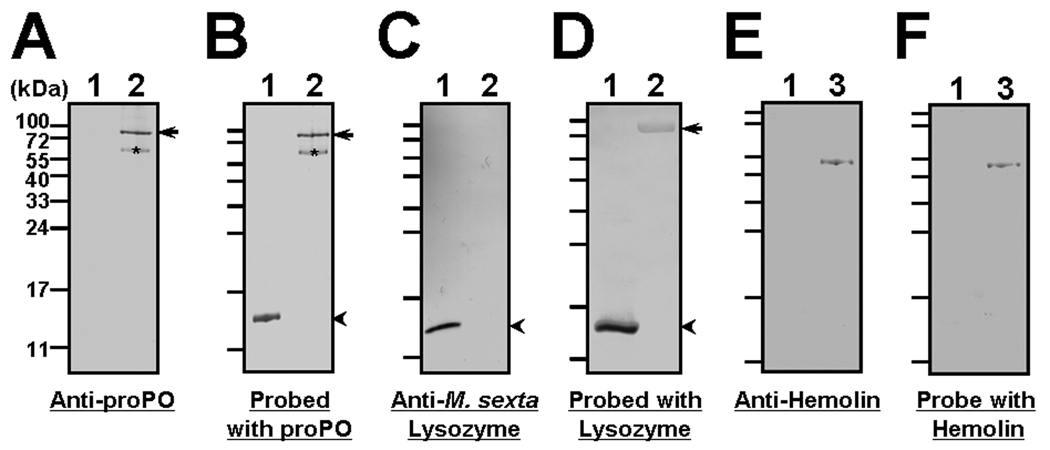

M. sexta lysozyme inhibited conversion of proPO to PO (Fig. 4C), suggesting that it may directly interact with proPO to prevent cleavage of proPO to active PO. To test direct interaction between M. sexta lysozyme and proPO, far-western blots were performed (Fig. 5). Direct immunoblotting results showed that antibody to M. sexta proPO recognized only purified M. sexta proPO but not M. sexta lysozyme (Fig. 5A, arrow), antibody to M. sexta lysozyme recognized only lysozyme but not the purified proPO (Fig. 5C, arrowhead), and antibody to M. sexta hemolin, a major inducible protein in M. sexta larvae that contains four immunoglobulin domains [58], recognized only hemolin but not lysozyme (Fig. 5E). In M. sexta hemolymph, both proPO1 and proPO2 are present (see Fig. 4C), but only one proPO band was detected in the purified proPO sample (Fig. 5A). This may be because the purified proPO sample predominantly contained one proPO isoform. It is also possible that two proPO isoforms could not be well separated in 12% SDS-PAGE. A weak signal at ~65 kDa in the purified proPO sample was also recognized by proPO antibody (Fig. 5A, asterisk), and this protein may be a cleavage product of proPO. However, when the membrane was probed with purified M. sexta proPO (Fig. 5B) or M. sexta lysozyme (Fig. 5D) first, then antibody to proPO also recognized M. sexta lysozyme (Fig. 5B, lane 1), and antibody to lysozyme recognized proPO (Fig. 5D, lane 2). When the membrane was probed with a control protein, M. sexta hemolin, antibody to hemolin did not recognize lysozyme (Fig. 5F, lane 1). These results suggest that the interaction between M. sexta lysozyme and proPO is specific.

Fig. 5. M. sexta lysozyme interacts with prophenoloxidase (proPO).

Interaction of M. sexta lysozyme with proPO was determined by far-western blot analysis. Purified M. sexta lysozyme (lane 1, 0.3 µg), proPO (lane 2, 0.3 µg) and hemolin (lane 3, 0.2 µg) were separated in 12% SDS-PAGE and proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. One set of the membranes was used for direct immunoblotting using rabbit polyclonal antibody to M. sexta proPO (A), lysozyme (C), or hemolin (E), and the other set of the membranes was used for far-western blot analysis. These membranes were washed in TBS-T buffer (TBS buffer containing 0.05% Tween-20) several times to remove SDS, blocked with 5% dry skim milk, and then incubated with purified M. sexta proPO (0.4µg/mL) (B), M. sexta lysozyme (0.8µg/mL) (D), or hemolin (0.4µg/mL ) (F). The membranes were then washed with TBS-T, and detected with rabbit antibody to M. sexta proPO (B), M. sexta lysozyme (D), or hemolin (F) the same as for direct immunoblotting in (A), (C) and (E). Arrows indicate the position of proPO, while arrowheads indicate the position of M. sexta lysozyme.

3.5. Protein interactions affect the lytic activity of lysozymes

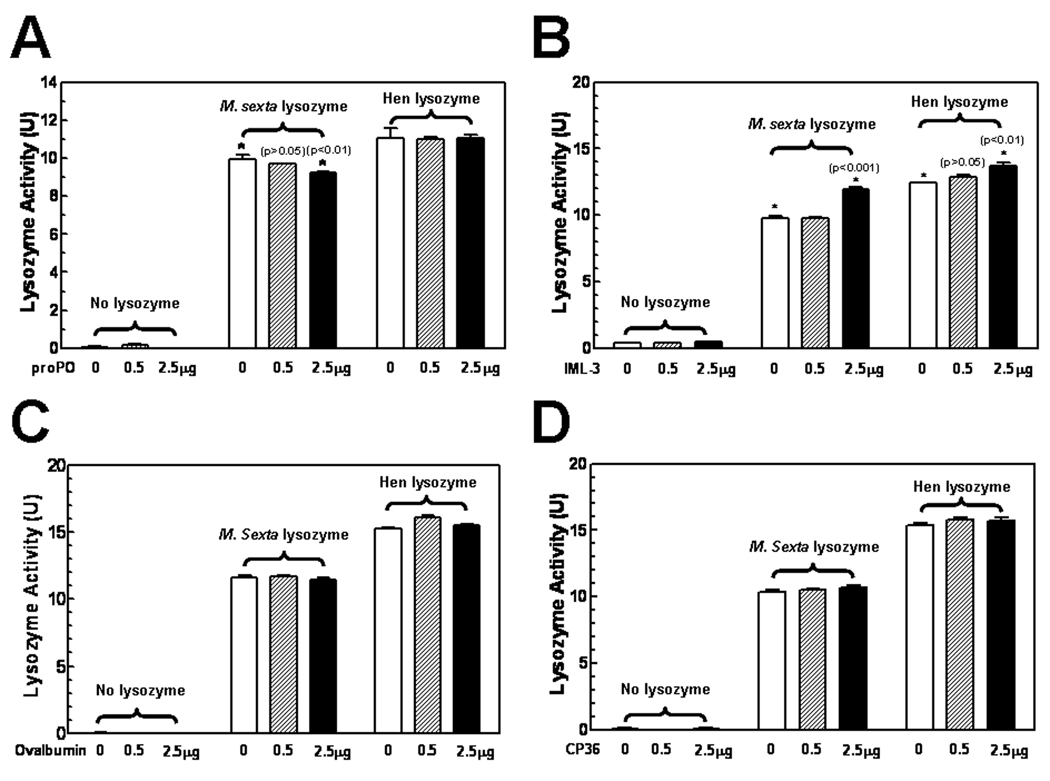

The above results showed that interaction between M. sexta lysozyme and proPO has an effect on proPO activation. To test whether protein interaction also has an effect on the activity of lysozymes, a lysozyme lytic activity assay was performed (Fig. 6). Interaction of high concentration of purified M. sexta proPO (2.5µg) with M. sexta lysozyme significantly (p<0.01) inhibited the lytic activity of M. sexta lysozyme, but the same amount of proPO (2.5µg) did not affect the lytic activity of hen egg white lysozyme (Fig. 6A). On the contrary, interaction of recombinant IML-3, a C-type lectin from M. sexta that can bind bacterial cells [55], with lysozymes significantly (p<0.01) increased the lytic activity of both M. sexta and hen egg white lysozymes (Fig. 6B). However, interaction of ovalbumin and recombinant CP36 [56] (two control proteins) with lysozymes did not have an effect on the lytic activity of M. sexta or hen egg white lysozyme (Fig. 6C and D). These results suggest that protein interaction can modulate the lytic activity of lysozymes.

Fig. 6. Protein interaction affects the lytic activity of lysozymes.

M. sexta or human milk lysozyme (0.5 µg) was pre-incubated with M. sexta proPO, recombinant IML-3 [55] or CP36 [56], or ovalbumin (0, 0.5, or 2.5µg) in 10 µL of 0.1M potassium phosphate buffer, pH6.4 in wells of a 96-well plate for 30min at room temperature. Then M. luteus suspension (500µg/mL, 190µL per well) was added and the plate was incubated at room temperature for another 30 min. Finally, absorbance at 595nm was monitored with time in a microtiter plate reader. Data from 3 replicas of each sample were analyzed, and the significance of difference was determined by an unpaired t-test using the GraphPad InStat software.

4. Discussion

Invertebrates mainly rely on innate immunity to fight against pathogens, and melanization response and induced expression of antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) are two important defense mechanisms [3, 6–8, 10–12]. Melanization response is particularly effective against large pathogens such as parasitoid eggs and parasites, whereas AMPs are effectively against microbial pathogens. Melanization requires activation of proPO to PO, and expression of AMPs is regulated by signal transduction pathways such as the Toll and immune deficiency (IMD) pathways in Drosophila [6, 7, 10–12, 59]. However, there is a trade-off between lysozyme/antibacterial activity and PO activity in hemolymph of some insect species [48–50], and a lysozyme from A. gambiae can inhibit melanization of Sephadex beads injected into mosquitoes [51]. Thus, it is not clear about the role of lysozymes in the proPO activation cascade.

In this study, we applied in intro assays to study the role of lysozymes in proPO activation in a lepidopteran, M. sexta. Our results elucidate the mechanisms of lysozymes in inhibition of proPO activation and melanization. We showed that M. sexta, human milk and hen egg white lysozymes did not inhibit PO activity (Fig. 2A), but significantly inhibited proPO activation (Fig. 2B–C and Fig. 3). M. sexta lysozyme inhibited proPO activation by preventing conversion of proPO to active PO (Fig. 4C) via direct protein interaction with proPO (Fig. 5). M. sexta lysozyme may also inhibit proPO activation by stimulating degradation of precursor proteins for SPH2 and PAP1 (Fig. 4E and F), two essential components required for proPO activation [15, 36]. Addition of exogenous protein (BSA or purified M. sexta lysozyme) to the plasma sample did not significantly affect the total protein concentration of the plasma, since the amount of protein added was 0.25 µg (to 1 µL plasma) and the total protein concentration of the plasma was ~37 µg/µL. Compared to the control protein BSA, addition of the purified M. sexta lysozyme to the plasma sample inhibited conversion of proPO to PO (Fig. 4C), stimulated degradation of SPH2 and PAP1 (Fig. 4E–F), but did not cause degradation of IML-3 (Fig. 4G) and IML-2 (data not shown), and other major plasma proteins (Fig. 4H). Thus, M. sexta lysozyme may also inhibit proPO activation and melanization by enhancing degradation of some selective plasma proteins that are involved in proPO activation. It is not clear how arthropods trade antibacterial activity with PO activity, as AMPs and PO activity are active against different pathogens. In A. gambiae and D. melanogaster, melanization response is not essential for defense against bacteria [60, 61], since hemocyte-mediated immune responses are central to the host defense against bacteria [62]. Thus, it is possible that arthropods can select effective immune mechanisms against a variety of pathogens depending upon the properties of pathogens.

Pathogens can stimulate both proPO activation and expression of AMPs. The proPO activation system involves a cascade of serine proteinases, and activation of proteinases is a rapid process. Lysozyme inhibited proPO activation mainly through direct protein interaction with proPO to prevent its cleavage (Fig. 4C), and after proPO is already converted to active PO, lysozymes did not have an effect on PO activity (Fig. 2A). However, it must be noticed that proPO is more easily activated in the immune-challenged plasma than in the naïve plasma, although the concentrations of AMPs, including lysozyme, are higher in the immune-challenged plasma. This is probably because activation of serine proteinases in the proPO activation cascade is a rapid process, while protein interaction between lysozyme and proPO is a relatively slow process compared to enzymatic activation. Thus, inhibition of proPO activation and melanization by lysozyme may require locally elevated concentrations of both proPO and lysozyme. It would be interested to know how lysozyme inhibits proPO activation and melanization in vivo against pathogens.

Lysozymes can interact with different proteins, including a C-type lectin (immulectin-3, IML-3) [41] and proPO (Fig. 5). Such protein interactions may also have an effect on the lytic activity of lysozymes. We showed that interaction of proPO with M. sexta lysozyme inhibited the lytic activity of lysozyme, and interaction of IML-3, which is a C-type lectin that can bind bacteria [55], with lysozymes significantly increased the lytic activity of both M. sexta and human milk lysozymes (Fig. 6). Lysozyme has a two-domain modular structure [63–65]. The carboxyl-terminal domain is usually responsible for the attachment to the bacterial surface, while the amino-terminal domain contains the lytic activity. Thus, interaction of IML-3 with lysozyme may occur at the carboxyl-terminal domain to enhance attachment of lysozyme to bacterial surface, so that the lytic activity is increased. Interaction of proPO with lysozyme may occur at the amino-terminal domain resulting in inhibition of the lytic activity. Future work is to investigate which domain(s) of lysozyme is involved in protein interactions and how protein interactions modulate the lytic activity of lysozymes and/or prevent cleavage of proPO.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant GM066356.

The abbreviations used are

- AMP

antimicrobial peptide

- CP8

M. sexta cationic protein (8 kDa)

- CP36

M. sexta cuticle protein (36 kDa)

- IML-3

immulectin-3

- LPS

lipopolysaccharide

- PAGE

polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis

- PAP

prophenoloxidase-activating proteinase

- PO

phenoloxidase

- proPO

prophenoloxidase

- SDS

sodium dodecyl sulfate

- SPH

serine proteinase homolog

- TBS

Tris-buffered saline

- TBS-T

TBS containing 0.05% Tween-20

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Gillespie JP, Kanost MR, Trenczek T. Biological mediators of insect immunity. Annu Rev Entomol. 1997;42:611–643. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ento.42.1.611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yu XQ, Zhu YF, Ma C, Fabrick JA, Kanost MR. Pattern recognition proteins in Manduca sexta plasma. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 2002;32:1287–1293. doi: 10.1016/s0965-1748(02)00091-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kanost MR, Jiang H, Yu XQ. Innate immune responses of a lepidopteran insect, Manduca sexta. Immunol Rev. 2004;198:97–105. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2004.0121.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Michel K, Kafatos FC. Mosquito immunity against Plasmodium. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 2005;35:677–689. doi: 10.1016/j.ibmb.2005.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ferrandon D, Imler JL, Hetru C, Hoffmann JA. The Drosophila systemic immune response: sensing and signalling during bacterial and fungal infections. Nat Rev Immunol. 2007;7:862–874. doi: 10.1038/nri2194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lemaitre B, Hoffmann J. The host defense of Drosophila melanogaster. Annu Rev Immunol. 2007;25:697–743. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.25.022106.141615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ashida M, Brey P. Recent advances in research on the insect prophenoloxidase cascade. In: Brey PT, Hultmark D, editors. Molecular Mechanisms of Immune Responses in Insects. London: Chapman & Hall; 1998. pp. 135–172. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hancock RE, Scott MG. The role of antimicrobial peptides in animal defenses. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:8856–8861. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.16.8856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lavine MD, Strand MR. Insect hemocytes and their role in immunity. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 2002;32:1295–1309. doi: 10.1016/s0965-1748(02)00092-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cerenius L, Soderhall K. The prophenoloxidase-activating system in invertebrates. Immunol Rev. 2004;198:116–126. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2004.00116.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Imler JL, Bulet P. Antimicrobial peptides in Drosophila: structures, activities and gene regulation. Chem Immunol Allergy. 2005;86:1–21. doi: 10.1159/000086648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Williams MJ. Drosophila hemopoiesis and cellular immunity. J Immunol. 2007;178:4711–4716. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.8.4711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tang H, Kambris Z, Lemaitre B, Hashimoto C. Two proteases defining a melanization cascade in the immune system of Drosophila. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:28097–28104. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M601642200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Barillas-Mury C. CLIP proteases and Plasmodium melanization in Anopheles gambiae. Trends Parasitol. 2007;23:297–299. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2007.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jiang H, Wang Y, Kanost MR. Pro-phenol oxidase activating proteinase from an insect, Manduca sexta: a bacteria-inducible protein similar to Drosophila easter. Proc Natl Aad Sci USA. 1998;95:12220–12225. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.21.12220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jiang H, Wang Y, Yu XQ, Kanost MR. Prophenoloxidase-activating proteinase-2 from hemolymph of Manduca sexta. A bacteria-inducible serine proteinase containing two clip domains. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:3552–3561. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M205743200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jiang H, Wang Y, Yu XQ, Zhu Y, Kanost M. Prophenoloxidase-activating proteinase-3 (PAP-3) from Manduca sexta hemolymph: a clip-domain serine proteinase regulated by serpin-1J and serine proteinase homologs. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 2003;33:1049–1060. doi: 10.1016/s0965-1748(03)00123-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang Y, Jiang H. Interaction of beta-1,3-glucan with its recognition protein activates hemolymph proteinase 14, an initiation enzyme of the prophenoloxidase activation system in Manduca sexta. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:9271–9278. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M513797200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gorman MJ, Wang Y, Jiang H, Kanost MR. Manduca sexta hemolymph proteinase 21 activates prophenoloxidase-activating proteinase 3 in an insect innate immune response proteinase cascade. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:11742–11749. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M611243200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kan H, Kim CH, Kwon HM, Park JW, Roh KB, Lee H, Park BJ, Zhang R, Zhang J, Soderhall K, Ha NC, Lee BL. Molecular control of phenoloxidase-induced melanin synthesis in an insect. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:25316–25323. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M804364200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yu XQ, Gan H, Kanost MR. Immulectin, an inducible C-type lectin from an insect, Manduca sexta, stimulates activation of plasma prophenol oxidase. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 1999;29:585–597. doi: 10.1016/s0965-1748(99)00036-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yu XQ, Kanost MR. Immulectin-2, a lipopolysaccharide-specific lectin from an insect, Manduca sexta, is induced in response to gram-negative bacteria. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:37373–37381. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M003021200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ma C, Kanost MR. A beta1,3-glucan recognition protein from an insect, Manduca sexta, agglutinates microorganisms and activates the phenoloxidase cascade. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:7505–7514. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.11.7505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Park JW, Je BR, Piao S, Inamura S, Fujimoto Y, Fukase K, Kusumoto S, Soderhall K, Ha NC, Lee BL. A synthetic peptidoglycan fragment as a competitive inhibitor of the melanization cascade. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:7747–7755. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M510058200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Takehana A, Katsuyama T, Yano T, Oshima Y, Takada H, Aigaki T, Kurata S. Overexpression of a pattern-recognition receptor, peptidoglycan-recognition protein-LE, activates imd/relish-mediated antibacterial defense and the prophenoloxidase cascade in Drosophila larvae. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:13705–13710. doi: 10.1073/pnas.212301199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Takehana A, Yano T, Mita S, Kotani A, Oshima Y, Kurata S. Peptidoglycan recognition protein (PGRP)-LE and PGRP-LC act synergistically in Drosophila immunity. EMBO J. 2004;23:4690–4700. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Park JW, Kim CH, Kim JH, Je BR, Roh KB, Kim SJ, Lee HH, Ryu JH, Lim JH, Oh BH, Lee WJ, Ha NC, Lee BL. Clustering of peptidoglycan recognition protein-SA is required for sensing lysine-type peptidoglycan in insects. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:6602–6607. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0610924104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schmidt RL, Trejo TR, Plummer TB, Platt JL, Tang AH. Infection-induced proteolysis of PGRP-LC controls the IMD activation and melanization cascades in Drosophila. FASEB J. 2008;22:918–929. doi: 10.1096/fj.06-7907com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.De Gregorio E, Han SJ, Lee WJ, Baek MJ, Osaki T, Kawabata S, Lee BL, Iwanaga S, Lemaitre B, Brey PT. An immune-responsive Serpin regulates the melanization cascade in Drosophila. Dev Cell. 2002;3:581–592. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(02)00267-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ligoxygakis P, Pelte N, Ji C, Leclerc V, Duvic B, Belvin M, Jiang H, Hoffmann JA, Reichhart JM. A serpin mutant links Toll activation to melanization in the host defence of Drosophila. EMBO J. 2002;21:6330–6337. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhu Y, Wang Y, Gorman MJ, Jiang H, Kanost MR. Manduca sexta serpin-3 regulates prophenoloxidase activation in response to infection by inhibiting prophenoloxidase-activating proteinases. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:46556–46564. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M309682200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tong Y, Kanost MR. Manduca sexta serpin-4 and serpin-5 inhibit the prophenol oxidase activation pathway: cDNA cloning, protein expression, and characterization. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:14923–14931. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M500531200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tong Y, Jiang H, Kanost MR. Identification of plasma proteases inhibited by Manduca sexta serpin-4 and serpin-5 and their association with components of the prophenol oxidase activation pathway. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:14932–14942. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M500532200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zou Z, Jiang H. Manduca sexta serpin-6 regulates immune serine proteinases PAP-3 and HP8. cDNA cloning, protein expression, inhibition kinetics, and function elucidation. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:14341–14348. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M500570200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Asgari S, Zhang G, Zareie R, Schmidt O. A serine proteinase homolog venom protein from an endoparasitoid wasp inhibits melanization of the host hemolymph. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 2003;33:1017–1024. doi: 10.1016/s0965-1748(03)00116-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yu XQ, Jiang H, Wang Y, Kanost MR. Nonproteolytic serine proteinase homologs are involved in prophenoloxidase activation in the tobacco hornworm, Manduca sexta. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 2003;33:197–208. doi: 10.1016/s0965-1748(02)00191-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhang G, Lu ZQ, Jiang H, Asgari S. Negative regulation of prophenoloxidase (proPO) activation by a clip-domain serine proteinase homolog (SPH) from endoparasitoid venom. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 2004;34:477–483. doi: 10.1016/j.ibmb.2004.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Volz J, Muller HM, Zdanowicz A, Kafatos FC, Osta MA. A genetic module regulates the melanization response of Anopheles to Plasmodium. Cell Microbiol. 2006;8:1392–1405. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2006.00718.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lu Z, Jiang H. Regulation of phenoloxidase activity by high- and low-molecular-weight inhibitors from the larval hemolymph of Manduca sexta. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 2007;37:478–485. doi: 10.1016/j.ibmb.2007.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Soderhall I, Wu C, Novotny M, Lee BL, Soderhall K. A novel protein acts as a negative regulator of prophenoloxidase activation and melanization in the freshwater crayfish Pacifastacus leniusculus. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:6301–6310. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M806764200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ling E, Rao XJ, Ao JQ, Yu XQ. Purification and characterization of a small cationic protein from the tobacco hornworm Manduca sexta. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 2009;39:263–271. doi: 10.1016/j.ibmb.2008.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Beck MH, Strand MR. A novel polydnavirus protein inhibits the insect prophenoloxidase activation pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:19267–19272. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0708056104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hultmark D. Insect lysozymes. EXS. 1996;75:87–102. doi: 10.1007/978-3-0348-9225-4_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dziarski R, Gupta D. Peptidoglycan recognition in innate immunity. J Endotoxin Res. 2005;11:304–310. doi: 10.1179/096805105X67256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Masschalck B, Deckers D, Michiels CW. Lytic and nonlytic mechanism of inactivation of gram-positive bacteria by lysozyme under atmospheric and high hydrostatic pressure. J Food Prot. 2002;65:1916–1923. doi: 10.4315/0362-028x-65.12.1916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Masschalck B, Michiels CW. Antimicrobial properties of lysozyme in relation to foodborne vegetative bacteria. Crit Rev Microbiol. 2003;29:191–214. doi: 10.1080/713610448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nash JA, Ballard TN, Weaver TE, Akinbi HT. The peptidoglycan-degrading property of lysozyme is not required for bactericidal activity in vivo. J Immunol. 2006;177:519–526. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.1.519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Freitak D, Wheat CW, Heckel DG, Vogel H. Immune system responses and fitness costs associated with consumption of bacteria in larvae of Trichoplusia ni. BMC Biol. 2007;5:56. doi: 10.1186/1741-7007-5-56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Povey S, Cotter SC, Simpson SJ, Lee KP, Wilson K. Can the protein costs of bacterial resistance be offset by altered feeding behaviour? J Anim Ecol. 2009;78:437–446. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2656.2008.01499.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cotter SC, Myatt JP, Benskin CM, Wilson K. Selection for cuticular melanism reveals immune function and life-history trade-offs in Spodoptera littoralis. J Evol Biol. 2008;21:1744–1754. doi: 10.1111/j.1420-9101.2008.01587.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Li B, Paskewitz SM. A role for lysozyme in melanization of Sephadex beads in Anopheles gambiae. J Insect Physiol. 2006;52:936–942. doi: 10.1016/j.jinsphys.2006.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gupta S, Wang Y, Jiang H. Manduca sexta prophenoloxidase (proPO) activation requires proPO-activating proteinase (PAP) and serine proteinase homologs (SPHs) simultaneously. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 2005;35:241–248. doi: 10.1016/j.ibmb.2004.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Dunn PE, Drake D. Fate of bacteria injected into naive and immunized larvae of the tobacco hornworm, Manduca sexta. J Invertebr Pathol. 1983;41:77–85. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Einarson MB, Orlinick JR. Identification of protein-protein interactions with glutathione-S-transferase fusion proteins. In: Golemis E, editor. Protein-Protein Interaction: A Molecular Cloning Manual. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 2002. pp. 37–58. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yu XQ, Tracy ME, Ling E, Scholz FR, Trenczek T. A novel C-type immulectin-3 from Manduca sexta is translocated from hemolymph into the cytoplasm of hemocytes. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 2005;35:285–295. doi: 10.1016/j.ibmb.2005.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Suderman RJ, Andersen SO, Hopkins TL, Kanost MR, Kramer KJ. Characterization and cDNA cloning of three major proteins from pharate pupal cuticle of Manduca sexta. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 2003;33:331–343. doi: 10.1016/s0965-1748(02)00247-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Laemmli UK. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yu XQ, Kanost MR. Developmental expression of Manduca sexta hemolin. Arch Insect Biochem Physiol. 1999;42:198–212. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1520-6327(199911)42:3<198::AID-ARCH4>3.0.CO;2-G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Williams MJ. Regulation of antibacterial and antifungal innate immunity in fruitflies and humans. Adv Immunol. 2001;79:225–259. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2776(01)79005-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Leclerc V, Pelte N, El Chamy L, Martinelli C, Ligoxygakis P, Hoffmann JA, Reichhart JM. Prophenoloxidase activation is not required for survival to microbial infections in Drosophila. EMBO Rep. 2006;7:231–235. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Schnitger AK, Kafatos FC, Osta MA. The melanization reaction is not required for survival of Anopheles gambiae mosquitoes after bacterial infections. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:21884–21888. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M701635200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Matova N, Anderson KV. Rel/NF-kappaB double mutants reveal that cellular immunity is central to Drosophila host defense. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:16424–16429. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0605721103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lescar J, Souchon H, Alzari PM. Crystal structures of pheasant and guinea fowl egg-white lysozymes. Protein Sci. 1994;3:788–798. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560030508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lopez R, Garcia E. Recent trends on the molecular biology of pneumococcal capsules, lytic enzymes, and bacteriophage. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2004;28:553–580. doi: 10.1016/j.femsre.2004.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Niyonsaba F, Ogawa H. Protective roles of the skin against infection: implication of naturally occurring human antimicrobial agents beta-defensins, cathelicidin LL-37 and lysozyme. J Dermatol Sci. 2005;40:157–168. doi: 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2005.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]