Abstract

Twin and family studies reveal a significant genetic contribution to the risk of smoking initiation and progression (SI/P), nicotine dependence (ND), and smoking cessation (SC). Further, numerous genes have been implicated in these smoking-related behaviors, especially for ND. However, no study has presented a comprehensive and systematic view of the genetic factors associated with these important smoking-related phenotypes. By reviewing the literature on these behaviors, we identified 16, 99, and 75 genes that have been associated with SI/P, ND, and SC, respectively. We then determined whether these genes were enriched in pathways important in the neuronal and brain functions underlying addiction. We identified 9, 21, and 13 pathways enriched in the genes associated with SI/P, ND, and SC, respectively. Among these pathways, four were common to all of the three phenotypes, that is, calcium signaling, cAMP-mediated signaling, dopamine receptor signaling, and G-protein-coupled receptor signaling. Further, we found that serotonin receptor signaling and tryptophan metabolism pathways were shared by SI/P and ND, tight junction signaling pathway was shared by SI/P and SC, and gap junction, neurotrophin/TRK signaling, synaptic long-term potentiation, and tyrosine metabolism were shared between ND and SC. Together, these findings show significant genetic overlap among these three related phenotypes. Although identification of susceptibility genes for smoking-related behaviors is still in an early stage, the approach used in this study has the potential to overcome the hurdles caused by factors such as genetic heterogeneity and small sample size, and thus should yield greater insights into the genetic mechanisms underlying these complex phenotypes.

Keywords: pathway analysis, smoking initiation, nicotine dependence, smoking cessation

INTRODUCTION

Cigarette smoking is the most common form of tobacco use (Smith and Fiore, 1999), and is one of the most significant sources of morbidity and death worldwide (Murray, 2006). In the United States, more than 20% of adults are current smokers (CDC, 2007), and cigarette smoking is responsible for ∼438 000 premature deaths and an estimated economic cost of $167 billion annually (CDC, 2005b). In addition, about 20% of high school students (CDC, 2006) and 8% of middle school students (CDC, 2005a) in the United States smoke. Moreover, every day, about 4000 teenagers in the United States initiate cigarette smoking, and more than 1000 of them may become daily cigarette smokers (SAMHSA, 2006). Although a large fraction of smokers try to quit (CDC, 2007), available treatments are effective for only a fraction of them (Hughes et al, 2007; Lerman et al, 2007). Thus, developing therapeutic approaches that can help smokers achieve and sustain abstinence from smoking, as well as methods that can prevent people, especially youths, from starting to smoke, remain a huge challenge in public health.

Cigarette smoking is a complex behavior that includes a number of stages such as initiation, experimentation, regular use, dependence, cessation, and relapse (Ho and Tyndale, 2007; Malaiyandi et al, 2005; Mayhew et al, 2000). Although the initiation of tobacco use, the progression from initial use to smoking dependence, and the ability to quit smoking are undoubtedly affected by various environmental factors, twin, family, and adoption studies have provided strong evidence that genetics has a substantial role in the etiology of these phenotypes (Goode et al, 2003; Lerman and Berrettini, 2003; Lerman et al, 2007; Osler et al, 2001). Earlier studies revealed a considerable genetic contribution to the risk of smoking initiation (SI) (Hardie et al, 2006; Kendler et al, 1999; Li et al, 2003; Mayhew et al, 2000; Morley et al, 2007; Vink et al, 2004), nicotine dependence (ND) (Kendler et al, 1999; Lessov et al, 2004a; Maes et al, 2004; Malaiyandi et al, 2005; Sullivan and Kendler, 1999; True et al, 1999), as well as smoking cessation (SC) (Hamilton et al, 2006; Heath et al, 1999; Morley et al, 2007; Xian et al, 2003).

Nicotine is the main psychoactive ingredient in cigarettes and evokes its physiological effects by stimulating the mesolimbic brain reward system by binding with nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChRs). So far, the majority of candidate gene-based association studies have focused on those genes that may predispose to addictive behavior by virtue of their effects on key neurotransmitter pathways (for example, dopamine and serotonin) and genes that may affect response to nicotine (for example, nAChRs and nicotine metabolism) (Ho and Tyndale, 2007). However, genetic studies have indicated that, for complex behaviors such as cigarette smoking, the individual differences can be attributed to hundreds of genes and their variants. Genes involved in different biological functions may act in concert to account for the risk of vulnerability to smoking behavior, with each gene having a moderate effect (Hall et al, 2002; Lessov et al, 2004b; Tyndale, 2003). Polymorphisms in related genes may cooperate in an additive or synergistic manner and modify the risk of smoking rather than act as sole determinants. Consistent with this belief, more and more genes have been found to be associated with smoking behavior over past decades, especially during the past few years. Whereas some plausible candidate genes (for example, nAChRs and dopamine signaling) have been reported and the findings have been partially replicated, numerous genes involved in other biological processes and pathways also have been associated with different smoking behaviors. This is especially true as the genome-wide association (GWA) study is being commonly used in genetic studies of complex traits such as smoking, and the underlying genetic factors can now be investigated in a high throughput and more comprehensive approach. In this situation, a systematic approach that is able to reveal the biochemical processes underlying the genes associated with smoking behaviors will not only help us understand the relations of these genes but also provide further evidence of the validity of the individual gene-based association studies.

In this study, we searched the literature to identify genes purportedly associated with SI/progression (P), ND, and SC. We then examined whether these genes are enriched in biochemical pathways important in neuronal and brain function.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Identification of Smoking-Related Genes

Contemporary genetic association studies of smoking behaviors are focused primarily on SI, progression to smoking dependence, ND (assessed by various measures or scales such as DSM-IV, Fagerstrom Test for Nicotine Dependence, Fagerstrom Tolerance Questionnaire, and/or smoking quantity, etc.), or SC. Only limited studies have been conducted on SI and progression to ND, and considering the potential overlap of these two highly related behaviors, we combined them into the single category of SI/P.

The list of candidate genes for the three smoking-related phenotypes was created by searching all human genetics association studies deposited in PUBMED (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/). Similar to Sullivan et al (2004), we queried the item ‘(Smoking [MeSH] OR Tobacco Use Disorder [MeSH]) AND (Polymorphism [MeSH] OR Genotype [MeSH] OR Alleles [MeSH]) NOT (Neoplasms [MeSH])', and a total of 1790 hits was retrieved by September 2008. The abstracts of these articles were reviewed and the association studies of any of the three smoking-related behaviors were selected. From the selected publications, we narrowed our selection by focusing on those reporting a significant association of one or more genes with any of the three phenotypes. To reduce the number of false-positive findings, the studies reporting negative or insignificant associations were not included, although it is likely that some of the genes analyzed in these studies might be associated with the phenotypes that we were interested in. The full reports of the selected publications were reviewed to ensure that the conclusions were supported by the content. From these studies, genes reported to be associated with each phenotype were selected for the current study.

The results from several GWA studies were included. In the work of Bierut et al (2007), 35 of 31 960 SNPs were identified with p-values <0.0001, and several genes were suggested to be associated with ND, including neurexin 1 (NRXN1), vacuolar sorting protein (VPS13A), transient receptor potential channel (TRPC7), as well as a classic candidate gene related to smoking, neuronal nicotinic cholinergic receptor β3 (CHRNB3). All the genes nominated in this study were included in our list for ND. In another large-scale candidate gene-based association study, Saccone et al (2007) analyzed 3713 SNPs corresponding to more than 300 candidate genes. The top five SNPs with the smallest false discovery rate (FDR) values (ranging from 0.056 to 0.166) corresponded with neuronal nicotinic cholinergic receptor α3 (CHRNA3), α5 (CHRNA5), and CHRNB3. In the work of Uhl et al (2007), allele frequencies in nicotine-dependent and control individuals were compared for 520 000 SNPs, and 32 genes were suggested to be potentially associated with ND; all of them were included in the ND-related gene list. In a recent study on SC, Uhl et al (2008) performed GWA studies on three independent samples to identify genes facilitating SC success with bupropion hydrochloride vs nicotine replacement therapy. Various genes involved in cell adhesion, transcription regulation, transportation, and signaling transduction were suggested to be candidates contributing to successful SC. From this study, we included those genes that showed significant association with SC in all the three samples (eight genes) or in two samples with at least two nominally significant SNPs in each sample (55 genes).

Identification of Enriched Biochemical Pathways

By literature search, we collected a list of genes associated with each smoking-related phenotype. To get a better understanding of the underlying biological mechanisms, multiple bioinformatics tools were used to identify the significantly enriched pathways involved in the smoking phenotypes. The available pathway analysis tools can be classified into three categories (Tarca et al, 2009): (1) Over-representation analysis (ORA), which compares the genes of interest with genes in predefined pathways and identifies the pathways that include a statistically higher number of genes in the list of interest as overrepresented; (2) functional class scoring (FCS), which compares the genes in chosen pathways with the entire list of genes sorted by certain criteria and identifies the pathways showing statistically significant correlation with the phenotypes under study; and (3) impact analysis, which is similar to ORA, but also considers the connections of genes in the pathways. The FCS approach, for example, GSEA (Subramanian et al, 2005), is not feasible for the current analysis as it requires gene expression measurements. The following is a brief description of the four pathway analysis tools used in the current study.

Ingenuity pathway analysis

The core of Ingenuity pathway analysis (IPA) (http://www.ingenuity.com/) is the Ingenuity Pathways Knowledge Base (IPKB), a manually curated knowledge database consisting of function, interaction, and other information of genes/proteins. On the basis of such information, IPA is able to perform analysis on global canonical pathways, dynamically generated biological networks, and global functions from a list of genes. Currently, the IPKB includes 81 canonical metabolic pathways involved in various metabolism processes such as energy metabolism, metabolism of amino acids, and complex carbohydrates. It also includes 202 signaling pathways, such as those related to neurotransmitter signaling, intracellular and secondary signaling, and nuclear receptor signaling.

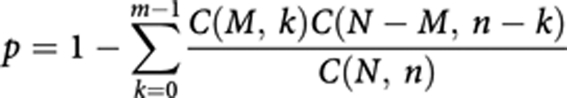

In our analysis, the gene symbol and the corresponding GenBank accession numbers of genes associated with each smoking phenotype were uploaded into the IPA and compared against the genes in each canonical pathway included in the IPKB. All the pathways with one or more genes overlapping the candidate genes were extracted. A significance value was assigned by the program to measure the chance that the genes of interest participate in a given extracted pathway. Briefly, the p-value for a given pathway was calculated by considering: (1) the number of input genes that could be mapped to this pathway in the IPKB, denoted by m; (2) the number of genes involved in this pathway, denoted by M; (3) the total number of input genes that could be mapped to the IPKB, denoted by n; and (4) the total number of known genes included in the IPKB, denoted by N. Then the p-value was calculated using the right-tailed Fisher's exact test (which is identical to the hypergeometric distribution in this case):

|

where C(M, k), C(N−M, n−k), and C(N, n) are binomial coefficients. In general, a p-value <0.05 indicates a statistically significant, non-random association.

As many pathways were examined, multiple comparison correction for the individually calculated p-values was necessary to permit reliable statistical inferences. The output p-values for the pathways associated with each smoking phenotype were analyzed separately using the MATLAB Bioinformatics Toolbox (The Mathworks, Natick, MA), which calculated the FDR by the method of Benjamini and Hochberg (1995).

The database for annotation, visualization, and integrated discovery

The database for annotation, visualization, and integrated discovery (DAVID) (http://david.abcc.ncifcrf.gov) (Hosack et al, 2003; Huang da et al, 2009) is a bioinformatics resource consisting of an integrated biological knowledge database and analytic tools aimed at extracting biological themes from gene/protein lists systematically. Compared with other tools, DAVID can provide an integrated and expanded back-end annotation database, multiple modular enrichment algorithms, and exploratory ability in an integrated data-mining environment. In our analysis, the input genes were analyzed using different text- and pathway-mining tools including gene functional classification, functional annotation chart or clustering, and functional annotation table. Pathway analysis was performed using its Functional Annotation Tool based on the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG; www.genome.jp/kegg) and Biocarta (www.biocarta.com) pathway databases. The enrichment of given pathways in the gene list was measured by EASE score, a modified Fisher exact test p-value. The program also performed p-value correction based on the method of Benjamini and Hochberg (1995).

GeneTrail

GeneTrail (Keller et al, 2008) (http://genetrail.bioinf.uni-sb.de) is web-based bioinformatics tool providing the statistical evaluation of gene/protein lists with respect to enrichment of functional categories. It can perform a wide variety of biological categories and pathway analysis based on multiple databases such as KEGG and Gene Ontology (GO; http://www.geneontology.org/). The GeneTrail analysis tool used in this work was the ‘Over-representation Analysis' module, which compared the gene list with a reference set of genes and identified the overrepresented pathways.

Onto Pathway-Express

Onto Pathway-Express (http://vortex.cs.wayne.edu/ontoexpress/) is a pathway analysis tool based on the KEGG pathway database. Different from other tools such as IPA and DAVID, this bioinformatics tool integrates the pathway topology and the position information of each gene in the pathway into its enrichment analysis. By implementing an impact factor analysis, Onto Pathway-Express incorporates both the probabilistic component and the gene interactions into pathway identification (Draghici et al, 2007). Briefly, on the basis of the input gene list, Onto Pathway-Express calculates a perturbation factor for each gene by taking into account its expression level and the perturbation of genes downstream from it in each selected pathway. The impact factor of the entire pathway includes a probabilistic term that takes into consideration the proportion of differentially regulated genes in the pathway and the perturbation factors of all genes in the pathway. The output pathways are assigned significance levels according to their impact factors, and the FDR values are computed by the method of Benjamini and Hochberg (1995).

Of the four tools, IPA, DAVID, and GeneTrail use the ORA approach. However, the pathway databases underlying these tools are different, for example, a proprietary database is included in IPA, whereas public databases are adopted by DAVID (KEGG and Biocarta) and GeneTrail (KEGG). Although Onto Pathway-Express performs its analysis on the basis of the KEGG database, the analysis algorithm is different from other methods. With these methods, we expect to obtain a relatively comprehensive evaluation of the pathways associated with the genes important to each smoking-related phenotype.

RESULTS

Identification of Genes Reported to be Associated with Each Smoking Behavior

By searching PUBMED, we extracted publications on the genetic association studies related to tobacco smoking. In the current work, we focused only on the studies related to one of the three phenotypes: SI/P, ND, and SC. For each phenotype, only the publications reporting a significant association of a gene(s) with this phenotype were collected; those by the original authors reporting a negative result or insignificant association were not included. A detailed list of all genes reported to be associated with each of the three phenotypes is provided in Table 1.

Table 1. Genes Associated with Smoking-Related Behaviors.

| Gene symbol | Gene name | Reference | Category |

|---|---|---|---|

| A2BP1 | Ataxin 2-binding protein 1 | Uhl et al (2008) | Cessation |

| AKAP13 | A kinase anchor protein 13 | Uhl et al (2008) | Cessation |

| ARRB2 | Arrestin, beta, 2 | Ray et al (2007a) | Cessation |

| ATP9A | Adenosine triphosphatase class II, type 9A | Uhl et al (2008) | Cessation |

| BNC2 | Basonuclin 2 | Uhl et al (2008) | Cessation |

| CACNA2D3 | Voltage-dependent calcium channel 32/3 subunit 3 | Uhl et al (2008) | Cessation |

| CACNB2 | Voltage-dependent calcium channel 32 | Uhl et al (2008) | Cessation |

| CCDC73 | Coiled-coil domain containing 73 | Uhl et al (2008) | Cessation |

| CDH13 | Cadherin 13 | Uhl et al (2008) | Cessation |

| CHN2 | Chimerin 2 | Uhl et al (2008) | Cessation |

| CHRNB2 | Cholinergic receptor, neuronal nicotinic, beta polypeptide 2 | Conti et al (2008) | Cessation |

| CLSTN2 | Calsyntenin 2 | Uhl et al (2008) | Cessation |

| COMT | Catechol-O-methyltransferase | Berrettini et al (2007); Colilla et al (2005); Han et al (2008); Johnstone et al (2007) | Cessation |

| CREB5 | cAMP responsive element-binding protein 5 | Uhl et al (2008) | Cessation |

| CSMD1 | Cub and Sushi multiple domains 1 | Uhl et al (2008) | Cessation |

| CTNNA2 | Catenin, alpha-2 | Uhl et al (2008) | Cessation |

| CYP2A6 | Cytochrome p450, subfamily IIA, polypeptide 6 | Kubota et al (2006); Ozaki et al (2006) | Cessation |

| CYP2B6 | Cytochrome p450, subfamily IIB, polypeptide 6 | David et al (2007a); Lee et al (2007) | Cessation |

| DAB1 | Disabled homolog 1 | Uhl et al (2008) | Cessation |

| DAPK1 | Death-associated protein kinase 1 | Uhl et al (2008) | Cessation |

| DBH | Dopamine beta hydroxylase | Johnstone et al (2004) | Cessation |

| DRD2 | Dopamine D2 receptor | David et al (2007a); Johnstone et al (2004); Lerman et al (2006); Morton et al (2006); Park et al (2005); Robinson et al (2007); Swan et al (2005); Yudkin et al (2004) | Cessation |

| DRD4 | Dopamine D4 receptor | David et al (2008b) | Cessation |

| DSCAM | Down syndrome cell adhesion molecule | Uhl et al (2008) | Cessation |

| DSCAML1 | Down syndrome cell adhesion molecule like 1 | Uhl et al (2008) | Cessation |

| ERC2 | ELKS/RAB6-interacting/CAST family member 2 | Uhl et al (2008) | Cessation |

| ERG | V-ets erythroblastosis virus E26 oncogene-like | Uhl et al (2008) | Cessation |

| FGF12 | Fibroblast growth factor 12 | Uhl et al (2008) | Cessation |

| FLJ42220 | FLJ42220 protein | Uhl et al (2008) | Cessation |

| FREQ | Frequenin, drosophila, homolog of | Dahl et al (2006) | Cessation |

| GALNT17 | Polypeptide N-acetylgalactosaminyltransferase 17 | Uhl et al (2008) | Cessation |

| GLIS3 | GLI-similar family zinc finger 3 | Uhl et al (2008) | Cessation |

| GRIK1 | Inotropic glutamate receptor kainate 1 | Uhl et al (2008) | Cessation |

| GRIK2 | Inotropic glutamate receptor kainate 2 | Uhl et al (2008) | Cessation |

| GRIN2A | Inotropic glutamate receptor N-methyl -aspartate 2A | Uhl et al (2008) | Cessation |

| HINT1 | Histidine triad nucleotide-binding protein 1 | Ray et al (2007a) | Cessation |

| ITPR2 | Inositol 1,4,5-triphosphate receptor 2 | Uhl et al (2008) | Cessation |

| KCNIP4 | Kv channel-interacting protein 4 | Uhl et al (2008) | Cessation |

| KCNK2 | K-type potassium channel 2 | Uhl et al (2008) | Cessation |

| KIAA1026 | Kazrin | Uhl et al (2008) | Cessation |

| LAMA1 | Laminin 31 | Uhl et al (2008) | Cessation |

| LARGE | Like-glycosyltransferase | Uhl et al (2008) | Cessation |

| LEPREL1 | Leprecan-like 1 | Uhl et al (2008) | Cessation |

| LYZL1 | Lysozyme-like 1 | Uhl et al (2008) | Cessation |

| MAGI1 | Membrane-associated guanylate kinase, WW and PDZ domain containing 1 | Uhl et al (2008) | Cessation |

| MTUS1 | Mitochondrial tumor suppressor 1 | Uhl et al (2008) | Cessation |

| MYO18B | Myosin XVIIIB | Uhl et al (2008) | Cessation |

| NEK11 | NIMA (never in mitosis gene a)-related kinase 11 | Uhl et al (2008) | Cessation |

| NELL1 | NEL-like 1 | Uhl et al (2008) | Cessation |

| NRXN3 | Neurexin 3 | Uhl et al (2008) | Cessation |

| OPRM1 | Opioid receptor, mu-1 | Lerman et al (2004); Munafo et al (2007); Ray et al (2007a) | Cessation |

| PARD3 | Partitioning defective 3 homolog | Uhl et al (2008) | Cessation |

| PARK2 | Parkin | Uhl et al (2008) | Cessation |

| PCDH15 | Protocadherin 15 | Uhl et al (2008) | Cessation |

| PEBP4 | Phosphatidylethanolamine-binding protein 4 | Uhl et al (2008) | Cessation |

| PPP2R2B | Protein phosphatase 2 regulatory subunit B, beta | Uhl et al (2008) | Cessation |

| PRKG1 | cGMP-dependent protein kinase I | Uhl et al (2008) | Cessation |

| PTPRD | Receptor protein tyrosine phosphatase D | Uhl et al (2008) | Cessation |

| PTPRN2 | Receptor protein tyrosine phosphatase N2 | Uhl et al (2008) | Cessation |

| PTPRT | Receptor protein tyrosine phosphatase T | Uhl et al (2008) | Cessation |

| RBM19 | RNA-binding motif protein 19 | Uhl et al (2008) | Cessation |

| SGCZ | Sarcoglycan zeta | Uhl et al (2008) | Cessation |

| SLC1A2 | Solute carrier family 1 high-affinity glutamate transporter 2 | Uhl et al (2008) | Cessation |

| SLC6A3 | Solute carrier family 6 (neurotransmitter transporter, dopamine), member 3 | Han et al (2008); O'Gara et al (2007); Stapleton et al (2007) | Cessation |

| SORCS1 | Sortilin-related VPS10 domain containing receptor 1 | Uhl et al (2008) | Cessation |

| SOX5 | SRY box 5 | Uhl et al (2008) | Cessation |

| ST6GALNAC3 | ST6 (3-N-acetyl-neuraminyl-2,3-3-galactosyl-1,3)- N-acetylgalactosaminide 3-2,6-sialyltransferase 3 | Uhl et al (2008) | Cessation |

| SUPT3H | Suppressor of Ty 3 homolog | Uhl et al (2008) | Cessation |

| TEK | TEK receptor tyrosine kinase | Uhl et al (2008) | Cessation |

| THSD4 | Thrombospondin type I domain containing 4 | Uhl et al (2008) | Cessation |

| TNIK | TRAF2 and NCK-interacting kinase | Uhl et al (2008) | Cessation |

| TRIO | Triple functional domain/PTPRF-interacting protein | Uhl et al (2008) | Cessation |

| UNC13C | Unc13 homolog C | Uhl et al (2008) | Cessation |

| USH2A | Usher syndrome 2A | Uhl et al (2008) | Cessation |

| ZNF423 | Zinc finger protein 423 | Uhl et al (2008) | Cessation |

| A2BP1 | Ataxin 2-binding protein 1 | Uhl et al (2007) | ND |

| ABCC4 | Atp-binding cassette, subfamily c, member 4 | Uhl et al (2007) | ND |

| ACTN2 | Actinin, alpha-2 | Uhl et al (2007) | ND |

| ADRA2A | Alpha-2a-adrenergic receptor | Prestes et al (2007) | ND |

| ANKK1 | Ankyrin repeat and kinase domain containing 1 | Gelernter et al (2006); Huang et al (2009); O'Gara et al (2008); Radwan et al (2007) | ND |

| ARRB1 | Arrestin, beta, 1 | Sun et al (2008) | ND |

| ARRB2 | Arrestin, beta, 2 | Sun et al (2008) | ND |

| BDNF | Brain-derived neurotrophic factor | Beuten et al (2005b); Lang et al (2007) | ND |

| CCK | Cholecystokinin | Comings et al (2001); Takimoto et al (2005) | ND |

| CD14 | Monocyte differentiation antigen CD14 | Hubacek et al (2002) | ND |

| CDH13 | Cadherin 13 | Uhl et al (2007) | ND |

| CHRM1 | Cholinergic receptor, muscarinic, 1 | Lou et al (2006) | ND |

| CHRM5 | Cholinergic receptor, muscarinic, 5 | Anney et al (2007) | ND |

| CHRNA3 | Cholinergic receptor, neuronal nicotinic, alpha polypeptide 3 | Berrettini et al (2008); Saccone et al (2007) | ND |

| CHRNA4 | Cholinergic receptor, neuronal nicotinic, alpha polypeptide 4 | Feng et al (2004); Li et al (2005) | ND |

| CHRNA5 | Cholinergic receptor, neuronal nicotinic, alpha polypeptide 5 | Berrettini et al (2008); Bierut et al (2007); Saccone et al (2007) | ND |

| CHRNA7 | Cholinergic receptor, neuronal nicotinic, alpha polypeptide 7 | De Luca et al (2004) | ND |

| CHRNB1 | Cholinergic receptor, neuronal nicotinic, beta polypeptide 1 | Lou et al (2006) | ND |

| CHRNB2 | Cholinergic receptor, neuronal nicotinic, beta polypeptide 2 | Ehringer et al (2007) | ND |

| CHRNB3 | Cholinergic receptor, neuronal nicotinic, beta polypeptide 3 | Bierut et al (2007); Saccone et al (2007) | ND |

| CLCA1 | Chloride channel, calcium-activated, 1 | Bierut et al (2007) | ND |

| CNR1 | Cannabinoid receptor 1 | Chen et al (2008) | ND |

| CNTN6 | Contactin 6 | Uhl et al (2007) | ND |

| COMT | Catechol-O-methyltransferase | Beuten et al (2006); Tochigi et al (2007) | ND |

| CREB1 | cAMP response element-binding protein 1 | Ray et al (2007b) | ND |

| CSMD1 | CUB and SUSHI multiple domains 1 | Uhl et al (2007) | ND |

| CTNNA3 | Catenin, alpha-3 | Bierut et al (2007) | ND |

| CYP17A1 | Cytochrome p450, family 17, subfamily a, polypeptide 1 | Liu et al (2005) | ND |

| CYP2A6 | Cytochrome p450, subfamily IIA, polypeptide 6 | Gambier et al (2005); Kubota et al (2006); Minematsu et al (2006); Tyndale et al (1999) | ND |

| CYP2B6 | Cytochrome p450, subfamily IIB, polypeptide 6 | Lee et al (2007) | ND |

| CYP2D6 | Cytochrome p450, subfamily IID, polypeptide 6 | Caporaso et al (2001) | ND |

| CYP2E1 | Cytochrome p450, subfamily Iie | Howard et al (2003); Tyndale (2003) | ND |

| DBH | Dopamine beta-hydroxylase, plasma | McKinney et al (2000) | ND |

| DDC | Dopa decarboxylase | Ma et al (2005); Yu et al (2006b); Zhang et al (2006a) | ND |

| DEFB1 | Defensin, beta, 1 | Uhl et al (2007) | ND |

| DLG4 | Discs large, Drosophila, homolog of, 4 | Lou et al (2007) | ND |

| DNM1 | Dynamin 1 | Xu et al (2009) | ND |

| DRD1 | Dopamine receptor D1 | Huang et al (2008a) | ND |

| DRD2 | Dopamine receptor D2 | Comings et al (1996); Costa-Mallen et al (2005); Noble et al (1994); Spitz et al (1998) | ND |

| DRD3 | Dopamine receptor D3 | Huang et al (2008b); Vandenbergh et al (2007) | ND |

| DRD4 | Dopamine receptor D4 | Lerman et al (1998); Shields et al (1998) | ND |

| ELMO1 | Engulfment and cell motility gene 1 | Uhl et al (2007) | ND |

| EPAC | Rap guanine nucleotide exchange factor 3 | Chen et al (2004) | ND |

| EPHX1 | Epoxide hydrolase 1, microsomal | Liu et al (2005) | ND |

| ESR1 | Estrogen receptor 1 | Liu et al (2005) | ND |

| FBXL17 | F-box and leucine-rich repeat protein 17 | Bierut et al (2007) | ND |

| FGF14 | Fibroblast growth factor 14 | Uhl et al (2007) | ND |

| FTO | Fat mass- and obesity-associated gene | Bierut et al (2007) | ND |

| GABRA2 | Gamma-aminobutyric acid A receptor 2 | Agrawal et al (2008) | ND |

| GABAB2 | Gamma-aminobutyric acid B receptor 2 | Beuten et al (2005a) | ND |

| GABARAP | GABA-a receptor-associated protein | Lou et al (2007) | ND |

| GABRA4 | Gamma-aminobutyric acid receptor, alpha-4 | Agrawal et al (2008); Bierut et al (2007) | ND |

| GCCR | Glucocorticoid receptor | Rogausch et al (2007) | ND |

| GIRK2 | Potassium channel, inwardly rectifying, subfamily j, member 6 | Bierut et al (2007) | ND |

| GPR154 | G-protein-coupled receptor 154 | Uhl et al (2007) | ND |

| GRM7 | Glutamate receptor, metabotropic, 7 | Uhl et al (2007) | ND |

| HHLA1 | Human endogenous retrovirus-h long terminal repeat-associating 1 | Uhl et al (2007) | ND |

| HRH4 | Histamine receptor h4 | Uhl et al (2007) | ND |

| HTR1F | Serotonin receptor 1F | Pomerleau et al (2007) | ND |

| HTR2A | 5-αhydroxytryptamine receptor 2a | do Prado-Lima et al (2004) | ND |

| KCNQ3 | Potassium channel, voltage-gated, kqt-like subfamily, member 3 | Uhl et al (2007) | ND |

| LRRN6C | Leucine-rich repeat protein, neuronal, 6c | Uhl et al (2007) | ND |

| LRRN1 | Leucine-rich repeat neuronal protein 1; lern1 | Uhl et al (2007) | ND |

| MAOA | Monoamine oxidase a | Lewis et al (2007); McKinney et al (2000); Tochigi et al (2007) | ND |

| MAOB | Monoamine oxidase b | Costa-Mallen et al (2005); Lewis et al (2007); Tochigi et al (2007) | ND |

| MICALCL | MICAL C-terminal like | Uhl et al (2007) | ND |

| MLH1 | MutL, E. coli, homolog of, 1 | Yu et al (2006a) | ND |

| NFIB | Nuclear factor i/b | Uhl et al (2007) | ND |

| NRXN1 | Neurexin 1 | Bierut et al (2007); Nussbaum et al (2008) | ND |

| NTRK2 | Neurotrophic tyrosine kinase receptor, type 2 | Beuten et al (2007b) | ND |

| OC90 | Otoconin 90 | Uhl et al (2007) | ND |

| OGG1 | 8-αOxoguanine DNA glycosylase | Liu et al (2005) | ND |

| OPRM1 | Opioid receptor, mu-1 | Ray et al (2006); Zhang et al (2006c) | ND |

| OSBPL1A | Oxysterol-binding protein-like protein 1a | Uhl et al (2007) | ND |

| PAM | Peptidylglycine alpha-amidating monooxygenase | Gelernter et al (2007) | ND |

| PDE4D | Phosphodiesterase 4d, cAMP-specific | Uhl et al (2007) | ND |

| PDE1C | Phosphodiesterase 1C, calmodulin-dependent, 70 kda | Uhl et al (2007) | ND |

| PPP1R1B | Phosphatase 1 regulatory subunit 1B | Beuten et al (2007a) | ND |

| PRKG1 | Protein kinase, cGMP-dependent, regulatory, type I | Uhl et al (2007) | ND |

| PTC | Phenylthiocarbamide gene | Cannon et al (2005) | ND |

| PTEN | Phosphatase and tensin homolog | Zhang et al (2006b) | ND |

| PTHB1 | Parathyroid hormone-responsive b1 gene | Uhl et al (2007) | ND |

| PTPRD | Protein-tyrosine phosphatase, receptor-type, delta | Uhl et al (2007) | ND |

| SEMA3C | Semaphorin 3c | Uhl et al (2007) | ND |

| SERT | Solute carrier family 6 (neurotransmitter transporter, serotonin), member 4; slc6a4 | Gerra et al (2005); Kremer et al (2005) | ND |

| SHC3 | SHC-transforming protein 3 | Li et al (2007) | ND |

| SIPA1L2 | Signal-induced proliferation-associated I like 2 | Uhl et al (2007) | ND |

| SLC18A2 | Solute carrier family 18 (vesicular monoamine), member 2 | Schwab et al (2005) | ND |

| SLC6A3 | Solute carrier family 6 (neurotransmitter transporter, dopamine), member 3 | Erblich et al (2005); Lerman et al (1999); Ling et al (2004); Timberlake et al (2006) | ND |

| SLC6A4 | Solute carrier family 6 (neurotransmitter transporter, serotonin), member 4 | Liu et al (2005); O'Gara et al (2008) | ND |

| SLC9A9 | Solute carrier family 9 (sodium/hydrogen exchanger), isoform a9 | Uhl et al (2007) | ND |

| TAS2R38 | Taste receptor, type 2, member 38 | Mangold et al (2008) | ND |

| TH | Tyrosine hydroxylase | Olsson et al (2004) | ND |

| TPH1 | Tryptophan hydroxylase 1 | Reuter and Hennig (2005); Reuter et al (2007) | ND |

| TPH2 | Tryptophan hydroxylase 2 | Reuter et al (2007) | ND |

| TRPC7 | Transient receptor potential cation channel, subfamily m, member 2 | Bierut et al (2007) | ND |

| TTC12 | Tetratricopeptide repeat domain 12 | Gelernter et al (2006) | ND |

| VPS13A | Vacuolar protein sorting 13, yeast, homolog of a | Bierut et al (2007) | ND |

| XKR5 | XK, Kell blood group complex subunit-related family, member 5 | Uhl et al (2007) | ND |

| CHRNA3 | Cholinergic receptor, neuronal nicotinic, alpha polypeptide 3 | Schlaepfer et al (2008) | SI/P |

| CHRNA5 | Cholinergic receptor, neuronal nicotinic, alpha polypeptide 5 | Schlaepfer et al (2008) | SI/P |

| CHRNA6 | Cholinergic receptor, neuronal nicotinic, alpha polypeptide 6 | Zeiger et al (2008) | SI/P |

| CHRNB3 | Cholinergic receptor, neuronal nicotinic, beta polypeptide 3 | Zeiger et al (2008) | SI/P |

| CHRNB4 | Cholinergic receptor, neuronal nicotinic, beta polypeptide 4 | Schlaepfer et al (2008) | SI/P |

| COMT | Catechol-O-methyltransferase | Guo et al (2007) | SI/P |

| CYP2A6 | Cytochrome p450, subfamily IIa, polypeptide 6 | Audrain-McGovern et al (2007) | SI/P |

| DRD2 | Dopamine D2 receptor | Audrain-McGovern et al (2004); Laucht et al (2008) | SI/P |

| DRD4 | Dopamine D4 receptor | Laucht et al (2008); Skowronek et al (2006) | SI/P |

| HTR6 | 5-αHydroxytryptamine receptor 6 | Lerer et al (2006) | SI/P |

| IL8 | Interleukin 8 | Ito et al (2005) | SI/P |

| PTEN | Phosphatase and tensin homolog | Zhang et al (2006b) | SI/P |

| RHOA | RAS homolog gene family, member A | Chen et al (2007) | SI/P |

| SLC6A3 | Solute carrier family 6 (neurotransmitter transporter, dopamine), member 3 | Ling et al (2004); Segman et al (2007) | SI/P |

| SLC6A4 | Solute carrier family 6 (neurotransmitter transporter, serotonin), member 4 | Skowronek et al (2006) | SI/P |

| TPH1 | Tryptophan hydroxylase 1 | Lerman et al (2001); Sullivan et al (2001) | SI/P |

Abbreviations: Cessation, smoking cessation; ND, nicotine dependence; SI/P, smoking initiation/progression.

For SI/P, 16 genes were identified in 15 studies, all of which were performed at individual gene level. Among them are five nAChR subunit genes, that is, CHRNA3, CHRNA5, CHRNA6, CHRNB3, and CHRNB4; dopamine receptor D2 (DRD2) and D4 (DRD4); and one serotonin receptor (HTR6). The genes encoding transporters of dopamine (DAT1 or SLC6A3) and serotonin (5-HTT or SLC6A4) were also included. The other genes were those involving the functions related to nicotine or neurotransmitter metabolism/synthesis such as COMT, CYP2A6, and TPH1; signal transduction (for example, PTEN and RHOA); or immune response (for example, IL8).

Regarding ND, there were 76 publications, including 73 studies focused on either single or a few genes. In these papers, 63 genes were reported to be significantly associated with ND by the original authors. The other three studies were either on a genome-wide scale (Bierut et al, 2007; Uhl et al, 2007) or on hundreds of candidate genes (Saccone et al, 2007), and they nominated a total of 41 genes. Collectively, 99 unique genes are included in the final list. The most prominent genes were those encoding acetylcholine receptors (CHRM1, CHRM5, CHRNA4, CHRNA5, and CHRNB2), dopamine receptors (DRD1, DRD2, DRD3, and DRD4), GABA receptors (GABRA2, GABRB2, GABARAP, and GABRA4), serotonin receptors (HTR1F and HTR2A), as well as proteins involved in nicotine or neurotransmitter metabolism/synthesis (for example, CYP2A6, DBH, MAOA, and TPH1).

For SC, 63 genes were nominated by a GWA study (Uhl et al, 2008) and 12 by 23 candidate gene-based association studies. These genes were involved in various biological functions, such as dopamine receptor signaling (DRD2, DRD4, and SLC6A3), glutamate receptor signaling (GRIK1, GRIK2, GRIN2A, and SLC1A2), and calcium signaling (for example, CACNA2D3, CACNB2, CDH13, and ITPR2).

Among the genes associated with the three smoking phenotypes, five were included in all the three lists, that is, COMT, CYP2A6, DRD2, DRD4, and SLC6A3. Another six genes, that is, CHRNA3, CHRNA5, CHRNB3, PTEN, SLC6A4, and TPH1, were associated with SI/P and ND. Ten genes, that is, A2BP1, ARRB2, CDH13, CHRNB2, CSMD1, CYP2B6, DBH, OPRM1, PRKG1, and PTPRD, were associated with ND and SC.

Enriched Biological Pathways Associated with Each Smoking-Related Phenotype

On the basis of the genes related to each smoking phenotype, enriched biochemical pathways were identified by IPA and other bioinformatics tools. For SI/P, the 16 genes (Table 1) were overrepresented in 9 pathways defined in the IPA database (p<0.05; Table 2). For five of these pathways (calcium signaling, dopamine receptor signaling, serotonin receptor signaling, cAMP-mediated signaling, and G-protein-coupled receptor signaling), the corresponding FDR values were <0.05. For the other pathways (tryptophan metabolism, tight junction signaling, IL-8 signaling, and integrin signaling), they had slightly higher FDR values (0.085–0.116).

Table 2. Pathways Overrepresented by Genes Associated with Smoking Initiation/Progressiona.

| Pathway | P-value | FDR | Genes included |

|---|---|---|---|

| Calcium signaling | 2.24 × 10−6 | 8.51 × 10−5 | CHRNA3, CHRNA5, CHRNA6, CHRNB3, CHRNB4 |

| Dopamine receptor signaling | 2.57 × 10−6 | 4.88 × 10−5 | COMT, DRD2, DRD4, SLC6A3 |

| Serotonin receptor signaling | 1.12 × 10−5 | 1.42 × 10−4 | HTR6, SLC6A4, TPH1 |

| cAMP-mediated signaling | 0.001 | 0.010 | DRD2, DRD4, HTR6 |

| G-protein-coupled receptor signaling | 0.002 | 0.015 | DRD2, DRD4, HTR6 |

| Tryptophan metabolism | 0.013 | 0.085 | CYP2A6, TPH1 |

| Tight junction signaling | 0.018 | 0.099 | PTEN, RHOA |

| IL-8 signaling | 0.021 | 0.102 | IL8, RHOA |

| Integrin signaling | 0.028 | 0.116 | PTEN, RHOA |

Pathways identified by IPA unless specified.

The IPA assigned 51 of the 99 genes associated with ND to 21 overrepresented pathways (p<0.05; Table 3). Fourteen of these pathways (for example, dopamine receptor signaling, cAMP-mediated signaling, G-protein-coupled receptor signaling, and serotonin receptor signaling) had an FDR<0.05, and the other pathways (for example, fatty acid metabolism and synaptic long-term potentiation (LTP)) had an FDR<0.14.

Table 3. Pathways Overrepresented by Genes Associated with Nicotine Dependencea.

| Pathway | P-value | FDR | Genes included |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dopamine receptor signaling | 1.58 × 10−13 | 1.03 × 10−11 | COMT, DDC, DRD1, DRD2, DRD3, DRD4, MAOA, MAOB, PPP1R1B, SLC18A2, SLC6A3, TH |

| cAMP-mediated signaling | 3.16 × 10−12 | 1.03 × 10−10 | ADRA2A, CHRM1, CHRM5, CREB1, DRD1, DRD2, DRD3, DRD4, GRM7, HTR1F, OPRM1, PDE1C, PDE4D, RAPGEF3 |

| G-protein-coupled receptor signaling | 5.01 × 10−12 | 1.03 × 10−10 | ADRA2A, CHRM1, CHRM5, CREB1, DRD1, DRD2, DRD3, DRD4, GRM7, HTR1F, HTR2A, OPRM1, PDE1C, PDE4D, RAPGEF3 |

| Serotonin receptor signaling | 6.31 × 10−11 | 1.03 × 10−9 | DDC, HTR2A, MAOA, MAOB, SLC18A2, SLC6A4, TPH1, TPH2 |

| Tryptophan metabolism | 3.80 × 10−7 | 4.94 × 10−6 | CYP2A6, CYP2B6, CYP2D6, CYP2E1, DDC, MAOA, MAOB, TPH1, TPH2 |

| Calcium signaling | 3.55 × 10−6 | 3.53 × 10−5 | CHRNA3, CHRNA4, CHRNA5, CHRNA7, CHRNB1, CHRNB2, CHRNB3, CREB1, TRPC7 |

| Tyrosine metabolism | 3.80 × 10−6 | 3.53 × 10−5 | COMT, DBH, DDC, MAOA, MAOB, TH |

| GABA receptor signaling | 2.04 × 10−5 | 1.66 × 10−4 | DNM1, GABARAP, GABBR2, GABRA2, GABRA4 |

| Linoleic acid metabolism | 4.37 × 10−4 | 3.16 × 10−3 | CYP2A6, CYP2B6, CYP2D6, CYP2E1, OC90 |

| Phenylalanine metabolism | 1.66 × 10−3 | 0.011 | DDC, MAOA, MAOB |

| Arachidonic acid metabolism | 2.09 × 10−3 | 0.012 | CYP2A6, CYP2B6, CYP2D6, CYP2E1, OC90 |

| Metabolism of xenobiotics by cytochrome P450 | 2.57 × 10−3 | 0.014 | CYP2A6, CYP2B6, CYP2D6, CYP2E1, EPHX1 |

| Histidine metabolism | 3.55 × 10−3 | 0.018 | DDC, MAOA, MAOB |

| Neurotrophin/TRK Signaling | 0.011 | 0.049 | BDNF, CREB1, NTRK2 |

| LPS/IL-1-mediated inhibition of RXR function | 0.012 | 0.051 | ABCC4, CD14, CYP2A6, MAOA, MAOB |

| Fatty acid metabolism | 0.013 | 0.051 | CYP2A6, CYP2B6, CYP2D6, CYP2E1 |

| PXR/RXR activation | 0.013 | 0.051 | CYP2A6, CYP2B6, NR3C1 |

| Synaptic long-term potentiation | 0.039 | 0.140 | CREB1, GRM7, RAPGEF3 |

| Gap junctionb | 0.005 | 0.078 | DRD1, DRD2, HTR2A, PRKG1 |

| MAPK signaling pathwayb | 0.006 | 0.078 | ARRB1, ARRB2, BDNF, CD14, FGF14, NTRK2 |

| Regulation of actin cytoskeletonb | 0.012 | 0.096 | ACTN2, CD14, CHRM1, CHRM5, FGF14 |

Pathways identified by IPA unless specified.

Pathway identified by Onto Pathway-Express.

For SC, 13 pathways were found to be enriched in 18 of the 75 genes associated with this phenotype (p<0.05; Table 4). Four of the pathways (dopamine receptor signaling, glutamate receptor signaling, cAMP-mediated signaling, and calcium signaling) had an FDR<0.05, and the remaining pathways (for example, synaptic LTP, G-protein-coupled receptor signaling, and synaptic long-term depression (LTD)) had an FDR ranging from 0.082 to 0.18.

Table 4. Pathways Overrepresented by Genes Associated with Smoking Cessationa.

| Pathway | P-value | FDR | Genes included |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dopamine receptor signaling | 2.29 × 10−6 | 1.03 × 10−4 | COMT, DRD2, DRD4, FREQ, PPP2R2B, SLC6A3 |

| Glutamate receptor signaling | 1.82 × 10−4 | 4.10 × 10−3 | GRIK1, GRIK2, GRIN2A, SLC1A2 |

| cAMP-mediated signaling | 1.15 × 10−3 | 0.017 | AKAP13, CREB5, DRD4, DRD2, OPRM1 |

| Calcium signaling | 1.91 × 10−3 | 0.022 | CHRNB2, CREB5, GRIK1, GRIN2A, ITPR2 |

| Circadian rhythm signaling | 9.12 × 10−3 | 0.082 | CREB5, GRIN2A |

| Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis signaling | 0.012 | 0.086 | GRIK2, GRIN2A, SLC1A2 |

| Synaptic long-term potentiation | 0.017 | 0.096 | CREB5, GRIN2A, ITPR2 |

| G-protein-coupled receptor signaling | 0.017 | 0.096 | CREB5, DRD2, DRD4, OPRM1 |

| Synaptic long-term depression | 0.034 | 0.170 | ITPR2, PPP2R2B, PRKG1 |

| Tyrosine metabolism | 0.037 | 0.170 | COMT, DBH |

| Neurotrophin/TRK signaling | 0.043 | 0.180 | CREB5, SORCS1 |

| Tight junctionb | 0.007 | 0.103 | CTNNA2, MAGI1, PARD3, PPP2R2B |

| Gap junctionb | 0.022 | 0.171 | DRD2, ITPR2, PRKG1 |

Pathways identified by IPA unless specified.

Pathway identified by Onto Pathway-Express.

Of the pathways enriched in the genes associated with each smoking phenotype, four, that is, calcium signaling, cAMP-mediated signaling, dopamine receptor signaling, and G-protein-coupled receptor signaling, were associated with all three smoking behaviors (Table 5). Two other enriched pathways (that is, serotonin receptor signaling and tryptophan metabolism) were shared by SI/P and ND, and three enriched pathways (neurotrophin/TRK signaling, synaptic LTP, and tyrosine metabolism) were shared by ND and SC.

Table 5. Identified Common and Specific Pathways for Each Smoking Behavior Category.

| Pathways | Smoking initiation and progression | Nicotine dependence | Smoking cessation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Calcium signaling | + | + | + |

| cAMP-mediated signaling | + | + | + |

| Dopamine receptor signaling | + | + | + |

| G-protein-coupled receptor signaling | + | + | + |

| Serotonin receptor signaling | + | + | − |

| Tryptophan metabolism | + | + | − |

| Gap junction | − | + | + |

| Neurotrophin/TRK signaling | − | + | + |

| Synaptic long-term potentiation | − | + | + |

| Tyrosine metabolism | − | + | + |

| Integrin signaling | + | − | − |

| Tight junction signaling | + | − | + |

| Arachidonic acid metabolism | − | + | − |

| Fatty acid metabolism | − | + | − |

| GABA receptor signaling | − | + | − |

| Histidine metabolism | − | + | − |

| Linoleic acid metabolism | − | + | − |

| LPS/IL-1-mediated inhibition of RXR function | − | + | − |

| MAPK signaling pathway | − | + | − |

| Metabolism of xenobiotics by cytochrome P450 | − | + | − |

| Phenylalanine metabolism | − | + | − |

| PXR/RXR activation | − | + | − |

| Regulation of actin cytoskeleton | − | + | − |

| Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis signaling | − | − | + |

| Circadian rhythm signaling | − | − | + |

| Glutamate receptor signaling | − | − | + |

| Synaptic long-term depression | − | − | + |

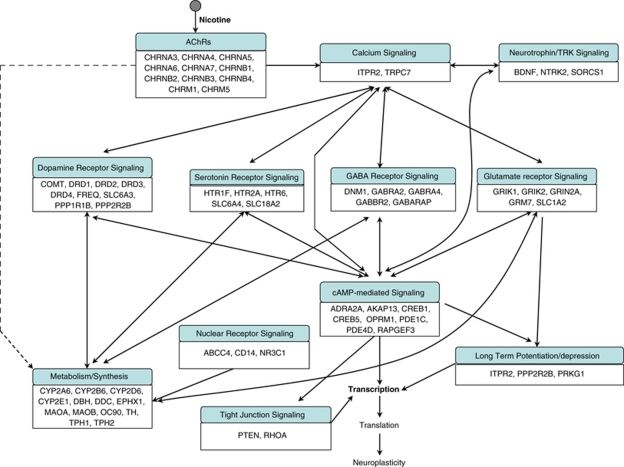

The enrichment of these pathways in multiple smoking phenotypes was consistent with the fact that synaptic transmission-related biological processes, such as nicotine-nAChR and dopamine signaling, were the key biochemical components underlying different smoking-related behaviors. This also implies that the genes involved in these three smoking phenotypes indeed overlap highly. On the basis of these biochemical relationships, we present in Figure 1 a schematic representation of the major pathways associated with the three phenotypes.

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of the genes and major pathways involved in smoking initiation/progression (SI/P), smoking dependence, or smoking cessation (SC). Genetic studies have indicated that tobacco smoking is a complex disorder. On the basis of the genes associated with SI/P, ND, and SC, we identified various enriched pathways corresponding to each phenotype of interest. These pathways were then connected on the basis of their biological relations. Owing to the overlap of many pathways among these three phenotypes, for the sake of simplicity, all identified pathways are shown together.

DISCUSSION

Over recent decades, much has been learnt from animal or cell models about the molecular mechanisms underlying nicotine treatment. Numerous genes and pathways have been found to have a role, either directly or indirectly, in these important smoking-related phenotypes. However, it is less clear whether the same sets of genes and pathways are involved in tobacco dependence of humans. Epidemiological studies have shown that genetic factors are responsible for a significant portion of the risk for SI, ND, and SC (Hamilton et al, 2006; Lerman and Berrettini, 2003; Li et al, 2003; Mayhew et al, 2000; Sullivan and Kendler, 1999). Moreover, significant genetic overlaps have been identified among these three phenotypes (Ho and Tyndale, 2007; Kendler et al, 1999; Maes et al, 2004). Identifying vulnerability genes for the three phenotypes, especially the biochemical pathways associated with them, will not only provide a systematic overview of the genetic factors underlying different smoking behaviors but is also helpful in guiding selection of potentially important genes for further analysis. With a thorough review of the genes contributing to the genetic risk of smoking behaviors, and a systematic search for gene networks using various pathway analysis tools, herein, we provide a comprehensive view of the biochemical pathways involved in the three major smoking phenotypes (see Figure 1 for details).

Although candidate gene-based association studies have provided much of our knowledge about factors contributing to smoking behaviors, a systematic approach, as reported in this study, has significant advantages. For complex disorders such as tobacco smoking, the presence of genetic heterogeneity and multiple interacting genes, each with a small to moderate effect, are considered to be the major hurdle in genetic association studies (Ho and Tyndale, 2007; Lessov-Schlaggar et al, 2008). Numerous genetic factors have been implicated, but in many cases, these findings cannot be replicated in independent studies. At the same time, because of resource limitations, a significant proportion of reported genetic studies might not have sufficient sample size or enough replication samples to reduce the rate of false-positive associations evoked by multiple testing. This is especially true for GWA studies, in which tens of thousands of SNPs can be analyzed simultaneously. A pathway approach, which takes account of the biochemical relevance of genes identified from association studies, not only can be more robust to potential false positives caused by factors such as low density of markers, small sample sizes, different ethnicities, and heterogeneity within and between samples but also may yield a more comprehensive view of the genetic mechanism underlying smoking behaviors. Moreover, although in candidate gene-based association studies, the selection of targets may be focused on some specific biological processes or pathways, the results from GWA studies seem to be more diverse. In such cases, pathway analysis becomes more necessary to detect the main biological themes from the genes involved in different functions. For example, in a recently reported GWA study, Vink et al (2009) identified 302 genes associated with SI and current smoking, but no gene involved in classic targets, such as dopamine receptor signaling or nAChRs, was detected. Instead, they identified genes related to glutamate receptor signaling, tyrosine kinase signaling, and cell-adhesion proteins. In our analysis based on genes other than those reported by Vink et al, glutamate receptor signaling was enriched among the genes associated with SC, and TRK signaling was enriched in both ND and SC (see Tables 3 and 4, and Figure 1). With the increased interest in conducting GWA studies for smoking behavior and other complex traits, a pathway approach will become more useful.

However, there are several limitations of this study. First, our pathway analysis results depend entirely on genes reported to be associated with each smoking phenotype of interest. Given that identification of susceptibility genes for each smoking phenotype is an ongoing process, the pathways identified in this report should be treated in the same way. Therefore, the pathways identified here are only some of the pathways that may be involved in the regulation of the three phenotypes. This is especially true for SI/P and SC, as significantly more genetic studies have been conducted on ND compared with the other smoking phenotypes. Second, we adopted the conclusions drawn by the original authors of each study in our pathway analysis. This means that some of our conclusions may be biased by some of those original reports because of their small sample size, the presence of heterogeneity, or absence of correction for multiple testing. Initially, we tried to apply a general standard to all those reported studies but had to give it up because different research groups conducted those studies over different time periods. It was challenging to redraw a conclusion from those studies reported by other researchers. However, we do not think this will affect our results greatly, as we have included as many reports as we could get from the literature. Third, for the sake of simplicity and increasing the number of genes included in each smoking phenotype, we classified more than 100 reports on smoking-related behaviors from different ethnic populations into three broad categories, that is, SI/P, ND, and SC. This is certain to bring a heterogeneity issue to the three phenotypes of interest, especially for SI/P and ND. Fourth, the direction of association is an important issue. For example, some variations may be associated with a protective effect against SI or ND, whereas others may increase the risk of such tendencies. Considering the fact that the direction of association depends on genetic variants under investigation for a given phenotype, we did not consider it in our current analyses. Because at this stage we are more interested in the genes and pathways potentially associated with smoking behaviors, focusing on the genes without considering the association directions will not create a serious problem. In addition, to simplify the analysis and reduce the number of false-positive genes, we did not include publications reporting negative or insignificant results. However, we realize that some genes from these studies may be among the factors associated with the smoking behaviors of interest. The fact that they were not found to be associated is likely attributable to other factors such as the small sample size or the presence of heterogeneity in their samples.

Although there are some limitations to this study, some interesting findings emerged, which probably never would have been identified in any single genetic study, including GWA, in one or a few samples. For example, we found that calcium signaling, dopamine receptor signaling, and cAMP-mediated signaling are the main pathways enriched in all three smoking phenotypes. The most prominent calcium signaling-related genes associated with each phenotype were nACh receptors. By mediating intracellular Ca2+ concentration, these ligand-gated cation channels have an important role in regulating various neuronal activities, including neurotransmitter release (Marshall et al, 1997; Wonnacott, 1997). Transcription factors, such as CREBs (cAMP responsive element-binding proteins), are crucial for conversion of events at cell membranes into alterations in gene expression. Regulation of the activity of CREB by drugs of abuse or stress has a profound effect on an animal's responsiveness to emotional stimuli (Carlezon et al, 2005; Conti and Blendy, 2004). The CREB function in the neurons is normally regulated by glutamatergic and dopaminergic inputs (Dudman et al, 2003).

The mesolimbic dopamine pathway is believed to be one of the central pathways underlying addiction to various drugs of abuse (Nestler, 2005). Genes included in this pathway are among the major targets of association study for ND. Although this pathway is enriched in all the three smoking-related phenotypes, the genes associated with each smoking phenotype are different. For SI/P, the genes reported in literature, such as COMT, DRD2, DRD4, and SLC6A3, were shared by ND and SC. For SC, two genes, FREQ and PPP2R2B, were uniquely detected. The FREQ protein (also known as neuronal calcium sensor 1, NCS1), a member of the neuronal calcium sensor family, has been implicated in the regulation of a wide range of neuronal functions such as membrane traffic, cell survival, ion channels, and receptor signaling (Burgoyne, 2007). In mammalian cells, FREQ may couple the dopamine and calcium signaling pathways by direct interaction with DRD2, implying an important role in the regulation of dopaminergic signaling in normal and diseased brain (Kabbani et al, 2002). The interaction between variants of DRD2 and FREQ significantly impacts the efficacy of nicotine replacement therapy (Dahl et al, 2006). PPP2R2B encodes a brain-specific regulatory subunit of protein phosphatase 2A (PP2A) and gives rise to multiple splice variants in neurons (Dagda et al, 2003; Schmidt et al, 2002). The product of this gene is suggested to be localized in the outer mitochondrial membrane and involved in neuronal survival regulation through the mitochondrial fission/fusion balance (Dagda et al, 2008). A CAG-repeat expansion in a non-coding region of this gene is responsible for the neurodegenerative disorder, spinocerebellar ataxia type 12 (SCA12) (Holmes et al, 1999). Although the dopamine receptor pathway has an important role in all three smoking phenotypes, it is possible that different parts of this pathway are involved in each smoking behavior, with SI/P and ND having greater similarity than SC. Given the importance of this pathway in the development of drug addiction, more genes need to be verified to obtain a more specific picture of its role underlying each phenotype.

Serotonin modulates dopamine release and has been implicated in nicotine reinforcement. Earlier study has shown that serotonin concentrations are increased by nicotine administration and decreased during withdrawal. Serotonin receptor signaling was enriched in the genes associated with SI/P and ND, but not in those associated with SC, in our analysis. In several recent studies designed to investigate the association between genes from the serotonin receptor signaling pathway and SC, no positive result was obtained (Brody et al, 2005; David et al, 2007b, 2008a; Munafo et al, 2006; O'Gara et al, 2008). Similar to the serotonin receptor signaling pathway, tryptophan metabolism, the pathway involved in the biological synthesis of serotonin, is enriched in the genes associated with SI/P, but not in those associated with SC. Consistent with this result, to date, the clinical effects of serotonergic-based drugs in SC are largely negative (Fletcher et al, 2008). Although more studies are needed, these results suggest that the genetic variants in serotonin receptor signaling and tryptophan metabolism pathways may be less important in SC.

Glutamate receptor signaling was found to be enriched in the genes associated with SC, but not in those associated with the other two phenotypes. In a recent GWA study (Vink et al, 2009), multiple genes from the glutamate receptor signaling pathway were suggested to be associated with SI and current smoking. Similarly, the glutamate receptor signaling-related genes associated with SC were also identified by a GWA study (Uhl et al, 2008). The genes in this pathway that are associated with SC include GRIK1, GRIK2, GRIN2A, and SLC1A2, whereas GRIN2A, GRIN2B, GRIK2, and GRM8 were associated with SI and current smoking (Vink et al, 2009). Another gene, GRM7, was suggested to be associated with ND in an earlier GWA study (Uhl et al, 2007). Taken together, these results suggest that glutamate receptor signaling is involved all three phenotypes of interest. In addition, till now, most of the genes from this pathway were identified by the GWA studies, showing the great potential of the GWA study in identifying genetic variants related to smoking behavior.

Our analysis indicates that the LTP pathway was enriched in genes associated with ND and SC, and the LTD pathway was enriched in genes associated with SC. Repeated exposure of neurons to nicotine eventually leads to the modulation of the functioning of the neural circuits in which the neurons operate. LTP and LTD are thought to be critical mechanisms that contribute to such modifications in neuronal plasticity (Kauer, 2004; Saal et al, 2003; Thomas and Malenka, 2003). In the development of ND, the LTP and LTD pathways may be essential for the neurons to form new synapses and eliminate some unnecessary ones to adapt to a new environment. In the process of SC, these pathways may be invoked to interrupt some neuron connections formed in the development of nicotine addiction in order to help the reward circuit return to normal. Until now, only a few genes related to LTP and LTD have been identified in the association studies. Considering the importance of these pathways in ND development and SC, other genes associated with these processes represent potential targets for future studies of these phenotypes.

In a recent study, five pathways were suggested to be associated with addiction to cocaine, alcohol, opioids, and nicotine in humans (Li et al, 2008). These pathways are gap junctions, GnRH signaling, LTP, MAPK signaling, and neuroactive ligand–receptor interaction. As shown in Table 5, three of the pathways (gap junction, LTP, and MAPK signaling) were enriched in genes associated with ND or SC. Although another pathway, neuroactive ligand-receptor interaction, was identified for all three smoking phenotypes by either Onto Pathway-Express or DAVID analysis in our work, it was not included in the current report because several more specific pathways, such as calcium signaling, dopamine receptor signaling, and serotonin receptor signaling, were also identified and reported herein. Our results provide further evidence that nicotine may share some biological mechanisms with other substances in addiction conditions. However, we also identified multiple specific pathways related to smoking behavior, suggesting that the mechanisms underlying nicotine addiction are complex and may be different in certain ways from those associated with addiction to other drugs.

The significantly overrepresented pathways suggest a view of neuronal responses in different conditions of nicotine–neuron interaction (Figure 1). On binding by nicotine, the nAChRs open and cause the influx of Ca2+ and Na+ into the presynaptic neuron, which evokes depolarization of the neuron, as well as activation of the Ca2+ signaling cascade. The Ca2+ signaling cascade is directly related to the presynaptic release of neurotransmitters, including dopamine, serotonin, GABA, and glutamate, in different neurons. The neurotransmitters interact with their specific receptors, provoking a series of signaling pathways, such as cAMP-mediated signaling and PKC signaling. With the regulation of these pathways, various physiological processes such as neuronal excitability and energy metabolism may be mediated. Variations in some of these genes may change the efficiency or function of the pathways and, eventually, the psychopathological phenotype. Although a significant number of genes associated with these pathways have been identified, our understanding of the genetic determinants of smoking is still in its early stages (Munafo and Johnstone, 2008). It can be expected that as more genetic factors are determined, more detailed pathways and more comprehensive understanding of the mechanisms of human smoking behavior will be obtained.

Acknowledgments

This project was funded by the National Institutes of Health grants DA-12844 and DA-13783. We thank Dr David L Bronson for his excellent editing of this manuscript and Dr Tianhua Niu for help on pathway analysis via DAVID, GeneTrail, and Onto Pathway-Express.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Agrawal A, Pergadia ML, Saccone SF, Hinrichs AL, Lessov-Schlaggar CN, Saccone NL, et al. Gamma-aminobutyric acid receptor genes and nicotine dependence: evidence for association from a case–control study. Addiction. 2008;103:1027–1038. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02236.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anney RJ, Lotfi-Miri M, Olsson CA, Reid SC, Hemphill SA, Patton GC. Variation in the gene coding for the M5 muscarinic receptor (CHRM5) influences cigarette dose but is not associated with dependence to drugs of addiction: evidence from a prospective population based cohort study of young adults. BMC Genet. 2007;8:46. doi: 10.1186/1471-2156-8-46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Audrain-McGovern J, Al Koudsi N, Rodriguez D, Wileyto EP, Shields PG, Tyndale RF. The role of CYP2A6 in the emergence of nicotine dependence in adolescents. Pediatrics. 2007;119:e264–e274. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-1583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Audrain-McGovern J, Lerman C, Wileyto EP, Rodriguez D, Shields PG. Interacting effects of genetic predisposition and depression on adolescent smoking progression. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161:1224–1230. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.7.1224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J R Stat Soc Series B. 1995;57:289–300. [Google Scholar]

- Berrettini W, Yuan X, Tozzi F, Song K, Francks C, Chilcoat H, et al. Alpha-5/alpha-3 nicotinic receptor subunit alleles increase risk for heavy smoking. Mol Psychiatry. 2008;13:368–373. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4002154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berrettini WH, Wileyto EP, Epstein L, Restine S, Hawk L, Shields P, et al. Catechol-O-methyltransferase (COMT) gene variants predict response to bupropion therapy for tobacco dependence. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;61:111–118. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.04.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beuten J, Ma JZ, Lou XY, Payne TJ, Li MD. Association analysis of the protein phosphatase 1 regulatory subunit 1B (PPP1R1B) gene with nicotine dependence in European- and African-American smokers. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2007a;144B:285–290. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.30399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beuten J, Ma JZ, Payne TJ, Dupont RT, Crews KM, Somes G, et al. Single- and multilocus allelic variants within the GABA(B) receptor subunit 2 (GABAB2) gene are significantly associated with nicotine dependence. Am J Hum Genet. 2005a;76:859–864. doi: 10.1086/429839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beuten J, Ma JZ, Payne TJ, Dupont RT, Lou XY, Crews KM, et al. Association of specific haplotypes of neurotrophic tyrosine kinase receptor 2 gene (NTRK2) with vulnerability to nicotine dependence in African-Americans and European-Americans. Biol Psychiatry. 2007b;61:48–55. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.02.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beuten J, Ma JZ, Payne TJ, Dupont RT, Quezada P, Huang W, et al. Significant association of BDNF haplotypes in European-American male smokers but not in European-American female or African-American smokers. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2005b;139B:73–80. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.30231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beuten J, Payne TJ, Ma JZ, Li MD. Significant association of catechol-O-methyltransferase (COMT) haplotypes with nicotine dependence in male and female smokers of two ethnic populations. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2006;31:675–684. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bierut LJ, Madden PA, Breslau N, Johnson EO, Hatsukami D, Pomerleau OF, et al. Novel genes identified in a high-density genome wide association study for nicotine dependence. Hum Mol Genet. 2007;16:24–35. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddl441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brody CL, Hamer DH, Haaga DA. Depression vulnerability, cigarette smoking, and the serotonin transporter gene. Addict Behav. 2005;30:557–566. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2004.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgoyne RD. Neuronal calcium sensor proteins: generating diversity in neuronal Ca2+ signalling. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2007;8:182–193. doi: 10.1038/nrn2093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cannon DS, Baker TB, Piper ME, Scholand MB, Lawrence DL, Drayna DT, et al. Associations between phenylthiocarbamide gene polymorphisms and cigarette smoking. Nicotine Tob Res. 2005;7:853–858. doi: 10.1080/14622200500330209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caporaso NE, Lerman C, Audrain J, Boyd NR, Main D, Issaq HJ, et al. Nicotine metabolism and CYP2D6 phenotype in smokers. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2001;10:261–263. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlezon WA, Jr, Duman RS, Nestler EJ. The many faces of CREB. Trends Neurosci. 2005;28:436–445. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2005.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CDC Tobacco use, access, and exposure to tobacco in media among middle and high school students—United States, 2004. Morbid Mortal Wkly Rep. 2005a;54:297–301. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CDC Annual smoking-attributable mortality, years of potential life lost, and economic costs—United States, 1997–2001. Morbid Mortal Wkly Rep. 2005b;54:625–628. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CDC Cigarette use among high school students—United States, 1991–2005. Morbid Mortal Wkly Rep. 2006;55:724–726. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CDC Cigarette smoking among adults—United States, 2006. Morbid Mortal Wkly Rep. 2007;56:1157–1161. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, Che Y, Zhang L, Putman AH, Damaj I, Martin BR, et al. RhoA, encoding a Rho GTPase, is associated with smoking initiation. Genes Brain Behav. 2007;6:689–697. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-183X.2006.00296.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, Williamson VS, An SS, Hettema JM, Aggen SH, Neale MC, et al. Cannabinoid receptor 1 gene association with nicotine dependence. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2008;65:816–824. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.65.7.816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, Wu B, Kendler KS. Association study of the Epac gene and tobacco smoking and nicotine dependence. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2004;129B:116–119. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.30040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colilla S, Lerman C, Shields PG, Jepson C, Rukstalis M, Berlin J, et al. Association of catechol-O-methyltransferase with smoking cessation in two independent studies of women. Pharmacogenet Genomics. 2005;15:393–398. doi: 10.1097/01213011-200506000-00004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comings DE, Ferry L, Bradshaw-Robinson S, Burchette R, Chiu C, Muhleman D. The dopamine D2 receptor (DRD2) gene: a genetic risk factor in smoking. Pharmacogenetics. 1996;6:73–79. doi: 10.1097/00008571-199602000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comings DE, Wu S, Gonzalez N, Iacono WG, McGue M, Peters WW, et al. Cholecystokinin (CCK) gene as a possible risk factor for smoking: a replication in two independent samples. Mol Genet Metab. 2001;73:349–353. doi: 10.1006/mgme.2001.3208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conti AC, Blendy JA. Regulation of antidepressant activity by cAMP response element binding proteins. Mol Neurobiol. 2004;30:143–155. doi: 10.1385/MN:30:2:143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conti DV, Lee W, Li D, Liu J, Van Den Berg D, Thomas PD, et al. Nicotinic acetylcholine receptor {beta}2 subunit gene implicated in a systems-based candidate gene study of smoking cessation. Hum Mol Genet. 2008;17:2834–2848. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddn181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa-Mallen P, Costa LG, Checkoway H. Genotype combinations for monoamine oxidase-B intron 13 polymorphism and dopamine D2 receptor TaqIB polymorphism are associated with ever-smoking status among men. Neurosci Lett. 2005;385:158–162. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2005.05.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dagda RK, Merrill RA, Cribbs JT, Chen Y, Hell JW, Usachev YM, et al. The spinocerebellar ataxia 12 gene product and protein phosphatase 2A regulatory subunit Bbeta2 antagonizes neuronal survival by promoting mitochondrial fission. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:36241–36248. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M800989200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dagda RK, Zaucha JA, Wadzinski BE, Strack S. A developmentally regulated, neuron-specific splice variant of the variable subunit Bbeta targets protein phosphatase 2A to mitochondria and modulates apoptosis. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:24976–24985. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M302832200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahl JP, Jepson C, Levenson R, Wileyto EP, Patterson F, Berrettini WH, et al. Interaction between variation in the D2 dopamine receptor (DRD2) and the neuronal calcium sensor-1 (FREQ) genes in predicting response to nicotine replacement therapy for tobacco dependence. Pharmacogenomics J. 2006;6:194–199. doi: 10.1038/sj.tpj.6500358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- David SP, Brown RA, Papandonatos GD, Kahler CW, Lloyd-Richardson EE, Munafo MR, et al. Pharmacogenetic clinical trial of sustained-release bupropion for smoking cessation. Nicotine Tob Res. 2007a;9:821–833. doi: 10.1080/14622200701382033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- David SP, Johnstone EC, Murphy MF, Aveyard P, Guo B, Lerman C, et al. Genetic variation in the serotonin pathway and smoking cessation with nicotine replacement therapy: new data from the Patch in Practice trial and pooled analyses. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2008a;98:77–85. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.04.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- David SP, Munafo MR, Murphy MF, Proctor M, Walton RT, Johnstone EC. Genetic variation in the dopamine D4 receptor (DRD4) gene and smoking cessation: follow-up of a randomised clinical trial of transdermal nicotine patch. Pharmacogenomics J. 2008b;8:122–128. doi: 10.1038/sj.tpj.6500447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- David SP, Munafo MR, Murphy MF, Walton RT, Johnstone EC. The serotonin transporter 5-HTTLPR polymorphism and treatment response to nicotine patch: follow-up of a randomized controlled trial. Nicotine Tob Res. 2007b;9:225–231. doi: 10.1080/14622200601078566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Luca V, Wong AH, Muller DJ, Wong GW, Tyndale RF, Kennedy JL. Evidence of association between smoking and alpha7 nicotinic receptor subunit gene in schizophrenia patients. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2004;29:1522–1526. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- do Prado-Lima PA, Chatkin JM, Taufer M, Oliveira G, Silveira E, Neto CA, et al. Polymorphism of 5HT2A serotonin receptor gene is implicated in smoking addiction. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2004;128B:90–93. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.30004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Draghici S, Khatri P, Tarca AL, Amin K, Done A, Voichita C, et al. A systems biology approach for pathway level analysis. Genome Res. 2007;17:1537–1545. doi: 10.1101/gr.6202607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dudman JT, Eaton ME, Rajadhyaksha A, Macias W, Taher M, Barczak A, et al. Dopamine D1 receptors mediate CREB phosphorylation via phosphorylation of the NMDA receptor at Ser897-NR1. J Neurochem. 2003;87:922–934. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2003.02067.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehringer MA, Clegg HV, Collins AC, Corley RP, Crowley T, Hewitt JK, et al. Association of the neuronal nicotinic receptor beta2 subunit gene (CHRNB2) with subjective responses to alcohol and nicotine. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2007;144B:596–604. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.30464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erblich J, Lerman C, Self DW, Diaz GA, Bovbjerg DH. Effects of dopamine D2 receptor (DRD2) and transporter (SLC6A3) polymorphisms on smoking cue-induced cigarette craving among African-American smokers. Mol Psychiatry. 2005;10:407–414. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng Y, Niu T, Xing H, Xu X, Chen C, Peng S, et al. A common haplotype of the nicotine acetylcholine receptor alpha 4 subunit gene is associated with vulnerability to nicotine addiction in men. Am J Hum Genet. 2004;75:112–121. doi: 10.1086/422194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher PJ, Le AD, Higgins GA. Serotonin receptors as potential targets for modulation of nicotine use and dependence. Prog Brain Res. 2008;172:361–383. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(08)00918-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gambier N, Batt AM, Marie B, Pfister M, Siest G, Visvikis-Siest S. Association of CYP2A6*1B genetic variant with the amount of smoking in French adults from the Stanislas cohort. Pharmacogenomics J. 2005;5:271–275. doi: 10.1038/sj.tpj.6500314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelernter J, Panhuysen C, Weiss R, Brady K, Poling J, Krauthammer M, et al. Genomewide linkage scan for nicotine dependence: identification of a chromosome 5 risk locus. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;61:119–126. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelernter J, Yu Y, Weiss R, Brady K, Panhuysen C, Yang BZ, et al. Haplotype spanning TTC12 and ANKK1, flanked by the DRD2 and NCAM1 loci, is strongly associated to nicotine dependence in two distinct American populations. Hum Mol Genet. 2006;15:3498–3507. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddl426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerra G, Garofano L, Zaimovic A, Moi G, Branchi B, Bussandri M, et al. Association of the serotonin transporter promoter polymorphism with smoking behavior among adolescents. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2005;135B:73–78. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.30173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goode EL, Badzioch MD, Kim H, Gagnon F, Rozek LS, Edwards KL, et al. Multiple genome-wide analyses of smoking behavior in the Framingham Heart Study. BMC Genet. 2003;4 (Suppl 1:S102. doi: 10.1186/1471-2156-4-S1-S102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo S, Chen da F, Zhou DF, Sun HQ, Wu GY, Haile CN, et al. Association of functional catechol-O-methyl transferase (COMT) Val108Met polymorphism with smoking severity and age of smoking initiation in Chinese male smokers. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2007;190:449–456. doi: 10.1007/s00213-006-0628-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall W, Madden P, Lynskey M. The genetics of tobacco use: methods, findings and policy implications. Tob Control. 2002;11:119–124. doi: 10.1136/tc.11.2.119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton AS, Lessov-Schlaggar CN, Cockburn MG, Unger JB, Cozen W, Mack TM. Gender differences in determinants of smoking initiation and persistence in California twins. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2006;15:1189–1197. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-05-0675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han DH, Joe KH, Na C, Lee YS. Effect of genetic polymorphisms on smoking cessation: a trial of bupropion in Korean male smokers. Psychiatr Genet. 2008;18:11–16. doi: 10.1097/YPG.0b013e3282df0939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardie TL, Moss HB, Lynch KG. Genetic correlations between smoking initiation and smoking behaviors in a twin sample. Addict Behav. 2006;31:2030–2037. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heath AC, Kirk KM, Meyer JM, Martin NG. Genetic and social determinants of initiation and age at onset of smoking in Australian twins. Behav Genet. 1999;29:395–407. doi: 10.1023/a:1021670703806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho MK, Tyndale RF. Overview of the pharmacogenomics of cigarette smoking. Pharmacogenomics J. 2007;7:81–98. doi: 10.1038/sj.tpj.6500436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes SE, O'Hearn EE, McInnis MG, Gorelick-Feldman DA, Kleiderlein JJ, Callahan C, et al. Expansion of a novel CAG trinucleotide repeat in the 5′ region of PPP2R2B is associated with SCA12. Nat Genet. 1999;23:391–392. doi: 10.1038/70493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosack DA, Dennis G, Jr, Sherman BT, Lane HC, Lempicki RA. Identifying biological themes within lists of genes with EASE. Genome Biol. 2003;4:R70. doi: 10.1186/gb-2003-4-10-r70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howard LA, Ahluwalia JS, Lin SK, Sellers EM, Tyndale RF. CYP2E1*1D regulatory polymorphism: association with alcohol and nicotine dependence. Pharmacogenetics. 2003;13:321–328. doi: 10.1097/01.fpc.0000054090.48725.a2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang da W, Sherman BT, Lempicki RA. Systematic and integrative analysis of large gene lists using DAVID bioinformatics resources. Nat Protoc. 2009;4:44–57. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]