Abstract

Prokaryotic toxin – antitoxin (TA) loci encode mRNA interferases that inhibit translation, either by cleaving mRNA codons at the ribosomal A site or by cleaving any RNA site-specifically. So far, seven mRNA interferases of Escherichia coli have been identified, four of which cleave mRNA by a translation-dependent mechanism. Here, we experimentally confirmed the presence of three novel TA loci in E. coli. We found that the yafNO, higBA (ygjNM) and ygiUT loci encode mRNA interferases related to RelE. YafO and HigB cleaved translated mRNA only, while YgiU cleaved RNA site-specifically at GC[A/U], independently of translation. Thus, YgiU is the first RelE-related mRNA interferase that cleaves mRNA independently of translation, in vivo. All three loci were induced by amino acid starvation, and inhibition of translation although to different degrees. Carbon starvation induced only two of the loci. The yafNO locus was induced by DNA damage, but the transcription originated from the dinB promoter. Thus, our results showed that the different TA loci responded differentially to environmental stresses. Induction of the three loci depended on Lon protease that may sense the environmental stresses and activate TA loci by cleavage of the antitoxins. Transcription of the three TA operons was autoregulated by the antitoxins.

Introduction

Prokaryotic toxin – antitoxin (TA) loci encode toxins whose ectopic production induces cell killing or inhibits cell growth and antitoxins that counteract the toxins (Gerdes et al., 2005). TA loci are present in almost all free-living prokaryotes, often in surprisingly high numbers (Pandey and Gerdes, 2005). For example, Mycobacterium tuberculosis has more than 60 TA loci while another pathogen, Photorhabdus luminisens has at least 59 and the obligate chemolithotroph Nitrosomonas europaea has at least 51 (Pandey and Gerdes, 2005; Jørgensen et al., 2009). By contrast, obligatory intracellular organisms have few or none. The model organism Escherichia coli also encodes a large number of TA loci that were divided into two types based on the molecular nature of the antitoxin (Hayes, 2003). Type I TA loci, such as hok/sok, ldr, symE and tisAB, encode antisense RNAs that inhibit translation of the toxin-encoding mRNAs (Gerdes and Wagner, 2007; Waters and Storz, 2009) while type II loci encode protein antitoxins that neutralize the toxins by direct protein–protein contact. So far, seven type II TA loci type have been identified in E. coli (relBE, dinJ yafQ, yefM yoeB, prlF yhaV, mazEF, chpSB and hicAB) (Masuda et al., 1993; Gotfredsen and Gerdes, 1998; Schmidt et al., 2007; Jørgensen et al., 2009; Prysak et al., 2009). Interestingly, all the type II loci of E. coli encode mRNA interferases whose ectopic overproduction inhibits translation by mRNA cleavage. Recently, a third type of TA loci was identified. In this case, the antitoxin is a small cis-encoded RNA that inhibits toxin activity by direct molecular interaction (Blower et al., 2009).

The biological function of mRNA interferase-encoding TA loci has been debated (recently reviewed in Magnuson, 2007; Hayes and Low, 2009; Van Melderen and Saavedra De Bast, 2009). Some scientists observed that mRNA interferases, such as MazF of E. coli, induced cell killing and therefore suggested that mRNA interferases function to mediate programmed cell death (Engelberg-Kulka et al., 2006). However, a more common view is that mRNA interferases function in growth rate control or persister cell formation (see the excellent recent review by Hayes and Low, 2009 for an in-depth discussion). These two models, which are not mutually exclusive, are consistent with observations made by many laboratories, namely that ectopic production of mRNA interferases is bacteriostatic rather than bacteriocidal (Pedersen et al., 2002; Christensen et al., 2003; Christensen-Dalsgaard and Gerdes, 2006; Budde et al., 2007; Schmidt et al., 2007; Fu et al., 2009; Jørgensen et al., 2009). Transcription of the relBE, mazEF and hicAB loci is strongly induced by conditions of amino acid (aa) starvation (Christensen et al., 2001; 2003; Jørgensen et al., 2009). It is well established that aa starvation does not induce cell death in E. coli standard strains (Cashel et al., 1996; Christensen et al., 2001; Traxler et al., 2008). In this connection we find it important to distinguish between E. coli and other organisms. This is because MazF of Myxococcus xanthus was produced during spore development and induced massive lysis of the cells that did not develop into spores (Nariya and Inouye, 2008). MazFMx homologue is not located adjacent to a mazE-like gene that encodes an antitoxin. Rather, MazFMx is regulated by a key developmental factor encoded elsewhere in the M. xanthus chromosome. Thus in this special case, a MazF homologue has been recruited to function in a developmental programme.

In case of relBE, the induction mechanism has been investigated in detail. The RelB antitoxin autoregulates transcription of the relBE operon and RelE acts as a corepressor such that transcription during steady state cell growth is highly repressed (Gotfredsen and Gerdes, 1998; Overgaard et al., 2009). Moreover, RelB is degraded by Lon (Christensen et al., 2001). Thus, when aa starvation ensues and the global translation rate is reduced by ≈10-fold, RelB is degraded and transcription of relBE increases dramatically (20–30-fold). This increase is due not only to degradation of RelB but also to the fact that RelE in excess of RelB disrupts the RelBE–operator complex and thereby stimulate transcription (Overgaard et al., 2008). Thus, nutritional deprivation and other stressful conditions result in activation of RelE and hence reduce the global rate of translation by mRNA cleavage (Christensen et al., 2001; Christensen and Gerdes, 2003). It should be emphasized that relBE reduced translation significantly during aa starvation but did not induce cell stasis, as is often surmised in the literature. Induction of relBE locus transcription in its native context reduces translation to a basal and balanced level that is reached rapidly after onset of starvation (10–15 min). During strong aa starvation (induced by serine hydroxamate, SHX) the global level of translation is c. 100% higher in a relBE deletion strain than in a wild-type strain (Christensen et al., 2001). However, some RelB variants that are metabolically destabilized due to single aa changes confer hyper-induction of RelE and a complete shut-down of translation during aa starvation (Christensen and Gerdes, 2004), consistent with the induction model described above. However, even in this case the effect of RelE activation is bacteriostatic, not bacteriocidal.

Based on their mechanism of action, the mRNA interferases of E. coli can be divided into two types, those that cleave mRNA at the ribosomal A site (RelE, YafQ and YoeB) and those that cleave mRNA independently of the ribosome (MazF, ChpBK, HicA) (Pedersen et al., 2003; Zhang et al., 2003; 2005a; Christensen-Dalsgaard and Gerdes, 2008; Jørgensen et al., 2009; Prysak et al., 2009; Zhang and Inouye, 2009). Of the ribosome-dependent mRNA interferases, RelE has been particularly well described. RelE associates with the ribosomes (Galvani et al., 2001) and cleaves mRNA positioned at the A site between the 2nd and 3rd nucleotides of the codon, both in vitro and in vivo (Christensen and Gerdes, 2003; Pedersen et al., 2003). RelE can cleave within all codons, including stop codons, but have sequence preferences. For example, codons with a G at the 3rd position are cleaved much more efficiently than codons with a G at the 2nd position. RelE exhibits an incomplete RNase Sa fold – that is, it lacks the catalytic aa triad present in homologous RNases (Li et al., 2009). This fact is consistent with the observation that RelE does not cleave naked RNA in vitro. YoeB of E. coli exhibits a similar fold, but contains the catalytic triad and consistently, YoeB cleaves naked RNA in vitro although with low efficiency (Kamada and Hanaoka, 2005). However, recent evidence suggests that YoeB, like RelE, cleaves mRNA by a ribosome-dependent mechanism in vivo (Christensen-Dalsgaard and Gerdes, 2008; Li et al., 2009; Zhang et al., 2009). YafQ, another RelE homologue of E. coli, has similarly been shown to cleave naked RNA in vitro whereas cleavage in vivo was dependent on translation of the target RNA (Prysak et al., 2009).

The first ribosome-independent mRNA interferase to be described was MazF of E. coli (Zhang et al., 2003). MazF cleaved translated and non-translated RNAs at ACA sites. Early investigations from our laboratory suggested that MazF activity depended on translation of the substrate RNA (Christensen and Gerdes, 2003) whereas other groups clearly did not observe such dependency (Zhang et al., 2005b). This puzzle was recently resolved by the observation that translation stimulates MazF cleavage seemingly by unfolding the secondary structure of the target RNA (Christensen-Dalsgaard and Gerdes, 2008).

One important objective in the TA field is to determine the biological function of TA loci. To firmly address this question it is crucial to know the exact number of redundant systems in the organisms of interest. To that end we wish to identify all TA loci present in the model organism E. coli. A recently developed Web-based algorithm, RASTA-Bacteria was previously used to suggest additional potential TA loci in E. coli (Sevin and Barloy-Hubler, 2007). Here we validate and characterize three of these new TA loci in E. coli, yafNO, ygjNM and ygiUT, and demonstrate that they all encode mRNA interferases that are induced by aa starvation and other stressful conditions. Two loci encode ribosome-dependent mRNA interferases while the third cleaves mRNA as an RNA restriction enzyme, independently of translation. Interestingly, the three TA loci responded differentially to various environmental stresses, indicating that TA loci may serve to restrict translation during different adverse growth conditions.

Secondary structure predictions according to PSIPRED (McGuffin et al., 2000) suggested that toxins HigB/YgjN, YgiU/MqsR and YafO all belong to the RelE super-family of RNases (Fig. S1). higBA loci encode RelE-homologous mRNA interferases (Pandey and Gerdes, 2005; Christensen-Dalsgaard and Gerdes, 2006). The sequence similarity with RelE is usually modest and we defined higBA loci as relBE loci with an inverted gene order – that is, the toxin is encoded by the first gene of the TA operon. According to the EcoCyc database (Keseler et al., 2009), the ygjNM genes have not been investigated before. Based on the experimental evidence presented here showing that YgjN is functionally related to RelE, the fact that the ygjNM locus has an ‘inverted’ gene order (Fig. 1), and the strong resemblance of the predicted secondary structures between RelE and YgjN, we suggest that ygjNM be renamed higBA. We also believe that the ygiUT (mqsR/ygiT) locus fits the criteria for being named a higBA locus. However, as its original name has been used several times in the literature we chose to keep the original nomenclature.

Fig. 1.

Three new toxin-antitoxin loci of E. coli. A. Chromosomal positions of the seven well-characterized toxin-antitoxin loci of E. coli K1: relBE, yefM yoeB, mazEF, prlF yhaV, chpSB and dinJ yafQ (black text) and the three new TA loci yafNO, higBA (ygjNM) and ygiUT (red text). All 10 loci encode mRNA interferases. B. Genetic overview of the three new TA loci, yafNO, higBA (ygjNM) and ygiUT and the flanking DNA regions. Toxin genes are coloured read, antitoxin genes are blue. The promoter regions of the TA operons are shown as a blow up below each gene pair. Transcriptional start sites were mapped (Fig. 5) and shown as broken arrows pointing rightward. The start sites of the first gene in the TA operons are also shown. Putative −10, −35 and Shine and Dalgarno (SD) sequences are indicated. Inverted repeats that are putative protein binding sites are shown as opposing arrows. The yafNO promoter has a putative LexA box. Bases that conform to the canonical LexA box are shown in bold.

Results

Three novel toxin-antitoxin gene pairs of E. coli

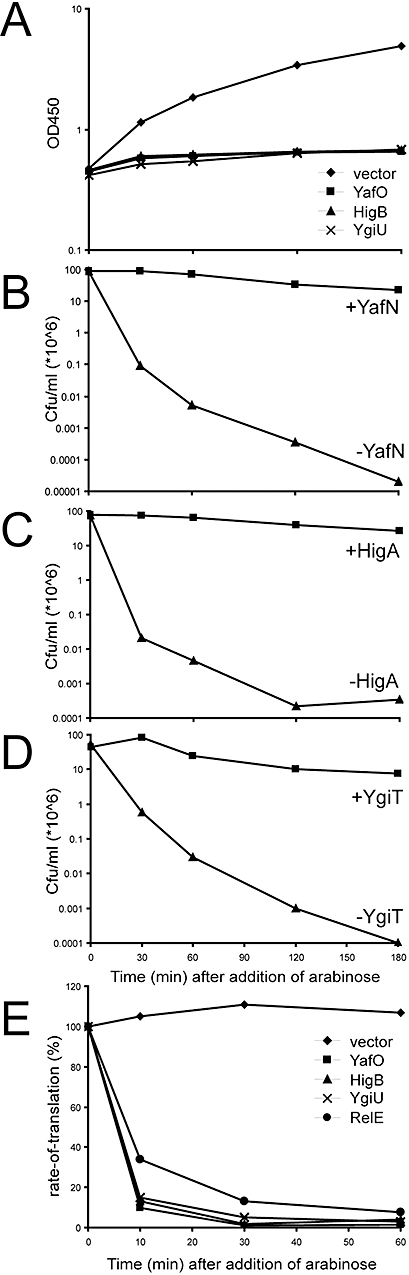

To investigate whether the loci yafNO, higBA (ygjNM) and ygiUT of E. coli K12 encode functional TA systems, the putative toxin genes (yafO, higB and ygiU) and antitoxin genes (yafN, higA and ygiU) were cloned on separate plasmids. The toxin genes were inserted downstream of the arabinose-inducible promoter of pBAD33 and the putative antitoxin genes were inserted into pNDM220, which contains a strong, synthetic LacI-regulated promoter (pA1/O3/O4). A series of growth experiments were carried out in strains carrying cognate plasmid pairs (Fig. 2A–D). To prevent activation of endogenous TA loci as observed previously (Garcia-Pino et al., 2008; Winther and Gerdes, 2009), all experiments were carried out in SC301467, a strain that lacks five TA loci (relBE, yefm yoeB, dinJ yafQ, mazEF and chpSB) (Christensen et al., 2004). As seen, transcriptional induction of the three putative toxin genes led to an almost immediate inhibition of cell growth in all three cases (Fig. 2A). Furthermore, a significant decrease in the number of colony-forming units was observed on plates without isopropyl β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) (Fig. 2B–D; −IPTG). However, cells of induced cultures could be almost completely resuscitated when plated on solid medium containing IPTG that induced the putative antitoxin genes (Fig. 2B–D; +IPTG).

Fig. 2.

yafNO, higBA and ygiUT are bona fide toxin-antitoxin loci. A. Growth of E. coli MG1655 (wt) carrying one of the plasmids, pBAD33 (vector), pMCD3306 (pBAD::SD::yafO), pBAD3310 (pBAD::SD::higB) or pMCD3312 (pBAD::SD::ygiU). Cells were grown exponentially in LB medium at 37°C. At time zero (OD450 ≈ 0.5), arabinose (0.2%) was added to induce transcription of the toxin genes. B–D. Cells of MG1655/pMCD3306 (pBAD::SD::yafO)/pMCD2202 (PA1/O3/O4::SD::yafN) (B), MG1655/pMCD3310 (pBAD::SD::higB)/pMCD2205 (PA1/O3/O4::SD::higA) (C) and MG1655/pMCD3312 (pBAD::SD::ygiU)/pMCD2207 (PA1/O3/O4::SD::ygiT) (D) were grown exponentially in LB medium at 37°C. Transcription of the toxin genes was induced by addition of arabinose (0.2%) at time zero and cells plated on LA plates with IPTG (2 mM) ( ) or without IPTG (

) or without IPTG ( ) to induce transcription of the antitoxin genes. The number of colony-forming units ml−1 was calculated for each of the indicated time points. E. Cells of E. coli MG1655 carrying pBAD33 (vector), pMG3323 (pBAD::relE), pMCD3306 (pBAD::SD::yafO), pBAD3310 (pBAD::SD::higB) or pMCD3312 (pBAD::SD::ygiU) were grown exponentially in M9 minimal medium and the transcription of the toxins induced at time zero with arabinose (0.2%). Samples were taken at the indicated time points, and protein synthesis was measured by pulse-labelling cells for 1 min with 35S-methionine and chased for 10 min with cold methionine. The pre-incubation rates were set to 100%.

) to induce transcription of the antitoxin genes. The number of colony-forming units ml−1 was calculated for each of the indicated time points. E. Cells of E. coli MG1655 carrying pBAD33 (vector), pMG3323 (pBAD::relE), pMCD3306 (pBAD::SD::yafO), pBAD3310 (pBAD::SD::higB) or pMCD3312 (pBAD::SD::ygiU) were grown exponentially in M9 minimal medium and the transcription of the toxins induced at time zero with arabinose (0.2%). Samples were taken at the indicated time points, and protein synthesis was measured by pulse-labelling cells for 1 min with 35S-methionine and chased for 10 min with cold methionine. The pre-incubation rates were set to 100%.

Including these new genes, E. coli K-12 has 10 TA loci all encoding mRNA interferases. The genomic locations of the 10 loci are shown in Fig. 1A. The yfeCD and ydaST loci were also predicted to be TA loci by the RASTA-Bacteria algorithm (Sevin and Barloy-Hubler, 2007), but we did not find evidence that these two loci encode functional toxins and antitoxins (data not shown).

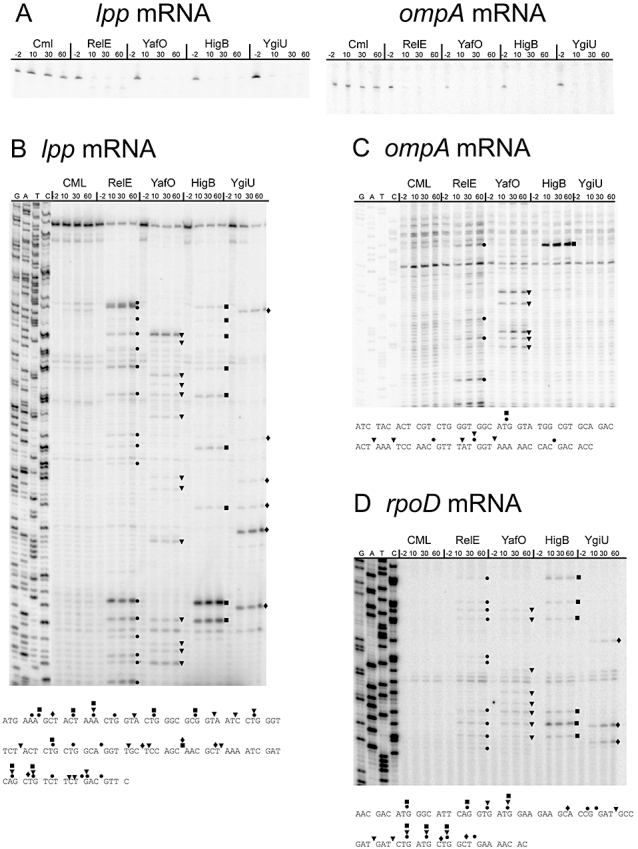

The toxins inhibit translation by targeting mRNA

We measured translation rates before and after induction of the toxin genes. Indeed, ectopic expression of the three toxins led to a rapid reduction of the global rates of translation in all three cases (Fig. 2E). To investigate if this inhibition of translation was caused by mRNA cleavage, model RNAs were monitored using Northern blot and Primer extension analyses. For comparison, RelE of E. coli was included in the analysis. Ectopic expression of any of the three toxins induced a rapid degradation of four different mRNAs, lpp, ompA, rpoD (Fig. 3) and dksA (Fig. 4). Induction of all three toxins resulted in unique and significant cleavage sites in the model mRNAs. YafO and HigB mediated cleavage patterns clearly resembling that of RelE. Thus, both mRNA interferases mediated cleavages that were confined to the coding regions of the RNAs. Moreover, the most abundant cleavage sites were located between the second and the third bases of the codons, rather than recognizing specific sequences in the RNAs.

Fig. 3.

Ectopic induction of yafO, higB and ygiU confers mRNA cleavage. A. Northern analysis of the lpp and ompA mRNAs using specific 32P-labelled ribonucleoacid probes. Primer extensions on lpp (B), ompA (C) and rpoD (D) mRNAs using the 32P-labelled primers lpp26, ompA-ctr-ccw and rpoD PE1 respectively. Total RNA was prepared from cells of MG1655Δ5 (lacks the toxin antitoxin systems relBE, yefM/yoeB, dinJ/yafQ, mazEF and chpSB) or MG1655Δ5 carrying on of the plasmids pMG3323 (pBAD::relE), pMCD3306 (pBAD::SD::yafO), pBAD3310 (pBAD::SD::higB) or pMCD3312 (pBAD::SD::ygiU) growing exponentially in LB medium at 37°C. At time zero, CML was added to MG1655Δ5 and transcription of the toxin genes from the remaining cells induced with arabinose (0.2%). Cleavage sites mediated by RelE (•), YafO ( ), HigB (

), HigB ( ) and YgiU (⋄) are marked on the gels and in the relevant RNA sequences below each gel. The numbers above lanes are the time points of cell sampling relative to toxin induction or addition of CML.

) and YgiU (⋄) are marked on the gels and in the relevant RNA sequences below each gel. The numbers above lanes are the time points of cell sampling relative to toxin induction or addition of CML.

Fig. 4.

Translation affects target mRNA cleavage differentially. A. Plasmid pMCD25420 produces wild type dksA mRNA whereas pMCD25421 produces a dksA mRNA with the ATG start codon changed to AAG (dksA′ mRNA). B–D. The strains MG1655Δ5ΔdksA/pMCD25420 or MG1655Δ5ΔdksA/pMCD25421 were cotransformed with the plasmids, pMCD3306, pMCD3310 and pMCD3312. Cells were grown exponentially in LB and induced with arabinose (0.2%) at time zero. Total RNA was purified and used for Northern blot analysis using an RNA probe complementary to the dksA mRNA (B) and primer extension analysis on dksA mRNA using the 32P-labelled primer pKW71D-3#PE (C and D), where (C) is a representation of the dksA 5′ end and panel D a representation of the RNA region close to the dksA stop codon. Numbers are time points of cell sampling relative to the addition of arabinose or CML. Significant cleavage sites are indicated with black symbols and important sites in the mRNAs are indicated with arrows to the right.

The YgiU/MqsR-mediated cleavage sites were scattered over the entire RNAs, although primarily found within coding regions. Cleavage site selection by YgiU/MqsR did not seem to be dependent on the codons but were in all cases observed after C in GC(A/U) sequences. Thus, YgiU/MqsR is most likely a sequence-specific ribonuclease.

YafO and HigB depend on translation whereas YgiU/MqsR does not

To more directly investigate the effect of translation of the model RNAs, we analysed the cleavage patterns of translated and non-translated versions of the dksA mRNA after toxin gene induction (the AUG start codon was changed to AAG). These RNAs have previously been used for this type of analysis (Christensen-Dalsgaard and Gerdes, 2008; Winther and Gerdes, 2009). A schematic of the two model mRNAs is presented in Fig. 4A. The level of the wild-type dksA mRNA decreased rapidly after toxin gene induction (Fig. 4B). By contrast, the level of the non-translated version of the dksA mRNA was not seriously affected by expression of any of the toxins (dksA′ in Fig. 4B).

Next, we investigated the cleavage patterns of the 5′ and 3′ ends of the two model mRNAs using primer extension analysis (Fig. 4C and D respectively). As seen, induction of yafO and higB mediated cleavages in the translated version of the dksA mRNA whereas no such cleavages were apparent in the non-translated RNA. By contrast, YgiU/MqsR cleaved both versions of the dksA mRNA, although the translated RNA appeared to be cleaved more efficiently. Most significantly, ygiU induction mediated cleavage in both mRNAs in a GCU sequence located downstream of the dksA stop codon, indicating that YgiU/MqsR cleavage occurred independently of translation in vivo. In summary, these analyses show that YafO and HigB/YgjN are mRNA interferases that depend on translation whereas YgiU/MqsR is a translation-independent mRNA interferase. Hence, YgiU/MqsR is the first known RelE-like mRNA interferase that cleaves mRNA independently of the ribosome, in vivo.

The three TA loci are transcribed from single promoters that are autoregulated by their cognate antitoxins

The promoters of the three TA loci were mapped using primer extension analysis. RNA was purified from cells exposed to chloramphenicol (CML) that induces strong transcription of previously characterized TA loci (Christensen et al., 2001; Hazan et al., 2004; Christensen-Dalsgaard and Gerdes, 2006). Specific bands consistent with transcriptional start sites were detected upstream of the first gene of all three TA loci (Fig. 5A–C, left). There were no such bands upstream of the second genes, indicating that all three TA loci were transcribed as operons (data not shown). In all three cases, inspection of the DNA sequences upstream of the +1 sites revealed the presence of putative −35 and −10 boxes, reinforcing that the observed bands represented the 5′ ends of the TA-encoding mRNAs (Fig. 1B). The amounts of the mRNA 5′ ends increased dramatically after the addition of CML in all three cases, indicating that the three promoters are regulated by mechanisms similar to that of previously characterized TA operons (see Discussion). To test the validity of the proposed promoters, we made operon fusions to lacZ. When the fusion plasmids were transformed into TB28ΔlacIZYA that encode the cognate antitoxins, transcription remained repressed (data not shown). However, when the fusion plasmids were transformed into strains lacking the cognate TA locus, the promoters were active (Fig. 5A–C, right), showing that all three promoters are negatively autoregulated by the TA operon product(s). As all three antitoxins have DNA binding motifs, we propose that the antitoxins inhibit transcription via binding to their cognate promoter regions. Indeed, ectopic expression of the antitoxins from high-copy plasmids could efficiently inhibit transcription from all three promoters (Fig. 5A–C, right). We conclude that all three TA loci analysed here contain an upstream promoter, which is negatively regulated by the antitoxin.

Fig. 5.

Mapping of the yafNO, higBA and ygiUT promoters. Left panels: Primer extension analysis on total RNA purified from cells of either wild-type MG1655 (wt) or ΔyafN, ΔhigB, ΔygiU, Δlon, Δclp or Δlon clp. Cells were grown exponentially in LB medium and at time zero protein synthesis was inhibited with chlorampenicol (50 μg ml−1). The 32P-labelled primers, yafN PE1, ygjN PE1 and ygiU PE1 were used to map the 5′ ends of yafNO (A), higBA (B) and ygiUT (C) mRNAs respectively. The putative transcriptional start sites are marked with arrows is the text panel next to each gel. Right panels: DNA fragments carrying the expected promoter sequences were inserted upstream of lacZ in transcriptional fusions. Cells of TB28ΔyafNO (A), TB28ΔhigBA (B) or TB28ΔygiUT (C) were transformed with empty pOU254 or derivatives containing promoter fusions to lacZ and empty pCA24N or derivatives carrying the relevant antitoxins under the control of the IPTG-inducible T5-lac promoter. Cells were plated on LA containing Amp (30 μg ml−1), Cml (50 μg ml−1), Xgal (40 μg ml−1) and IPTG (0.5 mM).

Lon protease is required for transcriptional activation of all three TA loci

As Lon has been reported to degrade antitoxins (Van Melderen et al., 1994; Christensen et al., 2001; 2004), we analysed the transcriptional patterns after addition of CML in lon, clp and lon clp strains (Fig. 5). As seen, transcriptional activation was highly reduced in the lon strain, whereas deletion of clp reduced transcription only slightly. Deletion of both lon and clp almost completely abolished transcriptional activation of the TA loci. These results show that the protease Lon, and to a lesser extent Clp, is essential for the activation of the three new TA loci.

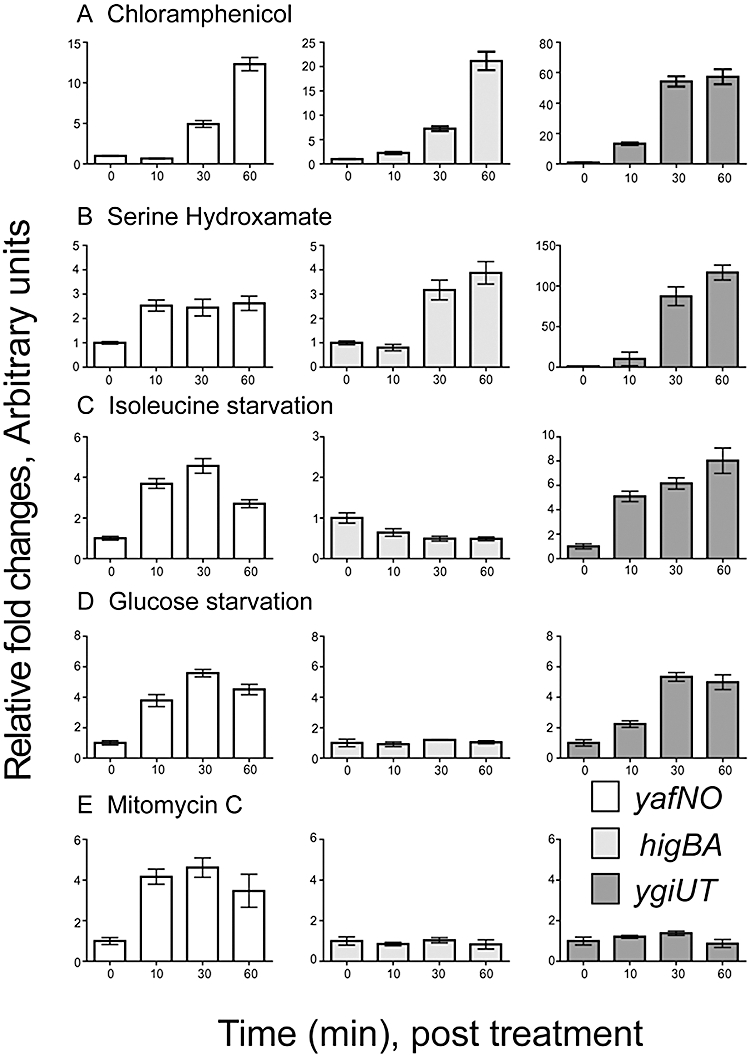

Differential induction of the three TA loci by environmental stress

The TA loci have been reported to be activated by several stressful conditions (Christensen et al., 2001; Jørgensen et al., 2009). Here, we used quantitative PCR (qPCR) to measure the relative changes of the levels of the yafNO, higBA and ygiUT mRNAs during conditions of environmental stresses (Fig. 6A–E). In accordance with Fig. 5, CML induced strong transcription of all three gene loci (Fig. 6A). Induction of aa starvation by SHX also induced strong transcription of all three loci (Fig. 6B). Interestingly, however, isoleucince starvation (induced by the addition of valine) induced the yafNO and ygiUT loci only, whereas the transcription rate of higBA actually decreased slightly (Fig. 6C). Glucose starvation activated transcription of yafNO and ygiUT, whereas higBA transcription was not affected in this case (Fig. 6D).

Fig. 6.

Nutritional stresses differentially induce TA loci transcription. Cells of MG1655 were grown exponentially in M9 minimal medium at 37°C. Samples were taken before and after induction of various stress conditions at the time points indicated. Transcriptional activation of yafNO, ygiUT and, higBA (ygjNM) were analysed by reverse transcription qPCR and represented by relative fold of changes. (A) 30 μg ml−1 CML; (B) 0.5 mg ml−1 valine addition; (C) 1% methyl-α- D-glycopyranoside; (D) 0.4 mg ml−1 serine hydroxamate; (E) 1 μg ml−1 mitomycin C. Note that the different panels have different scales on their Y-axes.

The yafNO locus belongs to the SOS regulon of E. coli

By inspection of the yafNO promoter sequence, we found that it contains a putative LexA binding site that overlaps with the transcriptional start site and the −10 box (Fig. 1). This is the usual location of functional LexA boxes. Furthermore, the yafNO locus has previously been reported to be part of the LexA-regulated dinB operon (McKenzie et al., 2003). LexA is responsible for the transcriptional repression of ≈40–60 genes in E. coli that are induced in response to DNA damage (the SOS response) (Fernandez De Henestrosa et al., 2000; Wade et al., 2005). We therefore investigated the transcriptional response of the three TA loci after addition of mitomycin C, an inducer of the SOS response. Strikingly, the yafNO mRNA level increased in response to mitomycin C, whereas the higBA and ygiUT mRNAs exhibited no such response (Fig. 6E). However, we speculated if the increased yafNO levels could originate from increased activity of the dinB promoter located upstream of yafNO rather than from the proximal yafNO promoter. To test this, we followed the yafNO mRNA levels after mitomycin C treatment in a strain in which the dinB promoter was deleted. The result clearly showed that the level of yafNO mRNA was completely unchanged after mitomycin treatment in the strain lacking the dinB promoter (Fig. S2). Thus, the yafNO locus is transcribed from two promoters: one SOS-regulated promoter upstream of dinB and one immediately upstream of yafN, which is autoregulated by the antitoxin YafN.

Discussion

Here, we characterized three new mRNA interferases of E. coli (Figs 2–4). Comparison of their secondary structures with those of other mRNA interferases of E. coli clearly indicates that all three mRNA interferases exhibit structural similarity with the RelE family of toxins (Fig. S1). The primary sequences of the RelE family of proteins are highly divergent (Gerdes, 2000; Pandey and Gerdes, 2005). For example, blast searches with E. coli RelE as a query does not identify YoeB as a RelE homologue, yet the 3D folds of the two proteins are very similar (Kamada and Hanaoka, 2005; Takagi et al., 2005; Francuski and Saenger, 2009; Li et al., 2009). Combined with the biological data presented here, this similarity strongly indicates that the three new mRNA interferases all belong to the RelE family of mRNA interferases (Fig. S1). During the final stage of this work, yafNO and ygiUT were confirmed to be TA loci (Yamaguchi et al., 2009; Zhang et al., 2009), thus confirming this conjecture.

In a genomic screen, the yafNO locus was previously identified as a putative TA locus, but the cellular target of YafO was not identified (Brown and Shaw, 2003). While this work was ongoing, YafO was described as a ribosome-dependent mRNA interferase (Zhang et al., 2009). This conclusion is in accordance with our observation that YafO activity depends on translation of the target mRNA (Fig. 4).

The ygiU/mqsR (motility quorum-sensing regulator) gene has been described as encoding a factor that positively regulates qseBC (Gonzalez Barrios et al., 2006), a two-component system that upregulates flagella and motility genes during quorum sensing (Sperandio et al., 2002). The ygiU/mqsR mutant strain had a Tn5 element inserted into the ygiU/mqsR gene, but it was not established at which level (transcriptional or post-transcriptional) the mutation affected qseBC regulation and the fact that YgiU/MqsR is an mRNA interferase thus raises the possibility that the effect was indirect (Gonzalez Barrios et al., 2006). Together with other known TA loci, ygiU/mqsR also has been found to be significantly upregulated in persister cells (Shah et al., 2006).

Messenger RNA cleavage by two of the toxins, YafO and HigB/YgjN depended on translation of the target RNAs (Fig. 3). Both toxins cleaved mRNA in a pattern similar to that of RelE (Fig. 4). By contrast, YgiU/MqsR cleaved target RNAs specifically at GC[A/U] sites, independently of translation (Figs 3 and 4), confirming recently published results by Inouye and coworkers (Yamaguchi et al., 2009). In both these properties, YgiU/MqsR resembled MazF and ChpB toxins (Zhang et al., 2003; 2005b).Thus, YgiU/MqsR is, to our knowledge, the first RelE-homologous mRNA interferase that can cleave target RNA independently of translation in vivo. However, it should be noted that translation of the target mRNA stimulated its cleavage by YgiU/MqsR, a property that has also be described in the case of MazF (Christensen-Dalsgaard and Gerdes, 2008) (Fig. 4).

All three new TA loci were transcribed from single promoters upstream of the first gene in the operon, all of which were autoregulated by the cognate antitoxins (Figs 1 and 6). Activation of the promoters in all cases depended on Lon protease and to a lesser extent Clp (Fig. 5). These observations are consistent with the finding that the antitoxins YafN, HigA and YgiT autoregulate transcription of their cognate TA loci (via binding to the promoter regions) and are degraded by Lon. Thus, transcriptional activation of the three operons by CML and SHX can be explained by drug-induced decay of the antitoxins followed by derepression of the TA promoters.

All three TA promoters were activated by nutritional stresses but, interestingly, they responded differently to different stresses (Fig. 6). All three loci were induced by ‘strong’ aa starvation (addition of SHX induces ‘strong’ aa starvation). The yafNO and ygiUT loci were also activated by mild aa starvation (induced by the addition of valine), and these two loci were also induced by glucose starvation. E. coli encodes at least 10 TA loci (Fig. 1A), all of which are induced by aa starvation (Christensen et al., 2001; 2003; Jørgensen et al., 2009; this work). One working hypothesis is that TA loci are stress response elements that are activated during unfavourable growth conditions to reduce translation and thereby somehow mitigate the detrimental effects conferred by the stress. It is also possible, and not mutually exclusive with the stress hypothesis, that mRNA interferases function to rapidly reprogram the ribosomes with newly synthesized mRNA after sudden changes in growth conditions – in other words, mRNA interferases may function ‘to wipe the board clean and start all over’. We are now testing these two hypotheses.

Interestingly, mitomycin C induced yafNO but not the two other TA loci (Fig. 6). The yafNO locus is located just downstream of dinB, another SOS-induced gene important for error-prone DNA repair by transletion synthesis of DNA (McKenzie et al., 2001) and is probably cotranscribed with dinB by an SOS-induced promoter (McKenzie et al., 2003). We identified a putative SOS box in the yafNO promoter (Fig. 1B), but our results clearly showed that the transcriptional induction of yafNO in response to mitomycin C originated from the upstream dinB promoter rather than the proximal yafNO promoter (Fig. S2). The observation that dinB-yafNO-dinP is induced by DNA damage raises the possibility that mRNA cleavage might be advantageous during conditions of DNA damage stress. This proposal is supported by the fact that E. coli contains at least two additional SOS-induced mRNA interferases, symE and dinJ yafQ (Kawano et al., 2007; Prysak et al., 2009). Interestingly, E. coli codes for additional TA-encoded toxins belonging to the SOS regulon, TisB and HokE (Fernandez De Henestrosa et al., 2000; Vogel et al., 2004). Expression of these latter two genes is regulated by small antisense RNAs. The yafNO locus is also autoregulated by the TA complex as CML and SHX induced strong transcription of the locus (Figs 5 and 6). Thus, the coupling to the SOS response adds to the complexity of the regulation of this TA operon.

Here we have identified three novel TA loci of E. coli K-12 and shown that they encode mRNA interferases related to RelE. The TA genes were all induced by strong aa starvation but responded differentially to other types of metabolic and environmental stress. Given these differences and similarities with the other mRNA interferase-encoding TA loci of E. coli, we believe that it will be essential to include these three new TA loci in a meaningful analysis of the physiological effects of TA loci.

Experimental procedures

Bacterial strains and plasmids

All bacterial strains and plasmids used in this work are listed in Table 1. Strains and plasmids that were constructed specifically for this work are described below. Oligonucleotides are listed in Table S1.

Table 1.

Strains and plasmids.

| Strains/plasmids | Genotype/plasmid properties | References |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| MG1655 | Wild-type E. coli K12 | |

| TB28 | MG1655ΔlacIZYA | Bernhardt and de Boer (2003) |

| BW25113 | lacIqrrnBT14 ΔlacZWJ16hsdR514 ΔaraBADAH33ΔrhaBADLD78 | Datsenko and Wanner (2000) |

| AG1 | endA1 recA1 gyrA96 thi-1 relA1 glnV44 hsdR17(rK- mK+) | Kitagawa et al. (2005) |

| MG1655ΔdksA::tet | MG1655ΔdksA::tet | Christensen-Dalsgaard and Gerdes (2008) |

| SC301467 | MG1655 ΔmazF ΔchpSB ΔrelBEΔ (dinJ-yafQ) Δ (yefM-yoeB) | Christensen et al. (2004) |

| JW0223 | BW25113ΔyafN::kan | Baba et al. (2006) |

| JW3054 | BW25113ΔygjN::kan | Baba et al. (2006) |

| JW2990 | BW25113ΔygiU::kan | Baba et al. (2006) |

| BW25113ΔPdinB::cat | BW25113ΔPdinB::cat | This work |

| SC301467ΔdksA::tet | SC301467ΔdksA::tet | This work |

| MG1655ΔygjN::kan | MG1655ΔygjN::kan | This work |

| MG1655ΔygiU::kan | MG1655ΔygiU::kan | This work |

| MCD2801 | TB28ΔyafNO::kan | This work |

| MCD2802 | TB28ΔygjNM::kan | This work |

| MCD2803 | TB28ΔygiUT::kan | This work |

| MCD03 | MG1655 ΔPdinB::cat | This work |

| Plasmids | ||

| pBAD33 | p15; cat araC pBAD | Guzman et al. (1995) |

| pMG3323 | pBAD33; pBAD::relE | Christensen and Gerdes (2003) |

| pMCD3306 | pBAD33; pBAD::SD::yafO | This work |

| pMCD3310 | pBAD33; pBAD::SD::higB (ygjN) | This work |

| pMCD3312 | pBAD33; pBAD::SD::ygiU | This work |

| pNDM220 | R1; bla lacIq pA1/O4/O3 | Gotfredsen and Gerdes (1998) |

| pMCD2202 | pNDM220; pA1/O4/O3::SD::yafN | This work |

| pMCD2205 | pNDM220; pA1/O4/O3::SD::ygjM | This work |

| pMCD2207 | pNDM220; pA1/O4/O3::SD::ygiT | This work |

| pKW254T | R1; terminator from pMG25 | Winther and Gerdes (2009) |

| pMCD25420 | R1; pKW254T dksA | Christensen-Dalsgaard and Gerdes (2008) |

| pMCD25421 | R1; pKW254T dksA′ | Christensen-Dalsgaard and Gerdes (2008) |

| pOU254 | R1; bla par mcs-lacZYA | R.B. Jensen, unpubl. data |

| pMCD25433 | R1; pOU254::PyafNO | This work |

| pMCD25434 | R1; pOU254::PhigBA | This work |

| pMCD25435 | R1; pOU254::PygiUT | This work |

| pCA24N | CmR; lacIq, pCA24N | Kitagawa et al. (2005) |

| pCA24N::yafN | pCA24N PT5-lac::yafN | Kitagawa et al. (2005) |

| pCA24N::ygjM | pCA24N PT5-lac::ygjM | Kitagawa et al. (2005) |

| pCA24N::ygiT | pCA24N PT5-lac::ygiT | Kitagawa et al. (2005) |

| pSC333 | pGEM3, bla, T7::lpp | Christensen and Gerdes (2003) |

Strains and plasmids constructed

MCD03

The strain (MG1655 ΔPdinB::cat) was constructed as described by Datsenko and Wanner (2000). A PCR product was made with pKD3 template and the following primers delta dinB-cw and delta dinB-ccw1. The PCR product was electroporated into BW25113/pKD46 and the cells were spread on LB plates containing 25 μg ml−1 of CM and incubated ON at 37°C. The deletion of dinB promoter was verified by PCR. A P1 lysate was made from BW25113 ΔPdinB::cat and the cat allele was transduced into MG1655.

MCD2801

A P1 lysate was made from MG1655ΔyafNO::kan (M.G. Jørgensen, unpublished) and the kan allele was transduced into TB28.

MCD2802

A P1 lysate was made from MG1655ΔhigBA::kan (M.G. Jørgensen, unpublished) and the kan allele was transduced into TB28.

MCD2803

A P1 lysate was made from MG1655ΔygiUT::kan (M.G. Jørgensen, unpublished) and the kan allele was transduced into TB28.

pMCD3306

The yafO gene was amplified from chromosomal DNA of MG1655 with primers yafO-XbaI-SD-up and yafO-HindII-down. The PCR product was digested with XbaI and HindIII and inserted into pBAD33. The resulting plasmid contains the yafO gene with an efficient SD sequence downstream of the PBAD promoter.

pMCD3310

The higB (ygjN) gene was amplified from chromosomal DNA of MG1655 with primers ygjN-XbaI-SD-cw and ygjN-HindII-ccw. The PCR product was digested with XbaI and HindIII and inserted into pBAD33. The resulting plasmid contains the higB (ygjN) gene with an efficient SD sequence downstream of the PBAD promoter.

pMCD3312

The ygiU gene was amplified from chromosomal DNA of MG1655 with primers msqR-cw and msqR-ccw. The PCR product was digested with XbaI and HindIII and inserted into pBAD33. The resulting plasmid contains the ygiU gene with an efficient SD sequence downstream of the PBAD promoter.

pMCD2202

The yafN gene was amplified from chromosomal DNA of MG1655 with primers yafN-KpnI-SD-up and yafN-SalI-down. The PCR product was digested with BamHI and XhoI and inserted into pNDM220. The resulting plasmid contains the yafN gene with an efficient SD sequence downstream of the pA1/O4/O3 promoter.

pMCD2205

The ygjM gene was amplified from chromosomal DNA of MG1655 with primers ygjM-KpnI-SD-cw and ygjM-XhoI-ccw. The PCR product was digested with KpnI and XhoI and inserted into pNDM220. The resulting plasmid contains the ygjM gene with an efficient SD sequence downstream of the pA1/O4/O3 promoter.

pMCD2207

The ygiT gene was amplified from chromosomal DNA of MG1655 with primers ygiT-cw and ygiT-ccw. The PCR product was digested with BamHI and XhoI and inserted into pNDM220. The resulting plasmid contains the ygiT gene with an efficient SD sequence downstream of the pA1/O4/O3 promoter.

pMCD25433

The region upstream of the yafNO locus was amplified with primers yafN-105-cw and yafN-ccw. The PCR product was digested with EcoRI and BamHI and inserted into pOU254. The resulting plasmid contains a transcriptional fusion of the yafNO promoter with lacZ.

pMCD25434

The region upstream of the higBA (ygjNM) locus was amplified with primers ygjN-124-cw and ygjN-ccw2. The PCR product was digested with EcoRI and BamHI and inserted into pOU254. The resulting plasmid contains a transcriptional fusion of the higBA promoter with lacZ.

pMCD25435

The region upstream of the ygiUT locus was amplified with primers mqsR-109-cw and mqsR-ccw2. The PCR product was digested with EcoRI and BamHI and inserted into pOU254. The resulting plasmid contains a transcriptional fusion of the ygiUT promoter with lacZ.

Growth conditions and media

Cells were grown in either Luria–Bertani broth or M9 minimal medium supplemented with aa in defined concentrations and 0.2% glucose or 0.5% glycerol at 37°C. When appropriate, the medium was supplemented with ampicillin (30 μg ml−1), CML (50 μg ml−1), kanamycin (25 μg ml−1) or tetracycline (10 μg ml−1). When aa starvation was induced in M9 minimal medium by the addition of 0.4 mg ml−1 SHX (Sigma-Aldrich), serine was excluded from the medium. Glucose starvation was induced in M9 minimal medium containing 0.05% glucose by the addition of 1% methyl-α-D-glucopyranoside (Sigma-Aldrich). Isoleucine starvation was induced in M9 minimal medium by addition of 0.5 mg ml−1 valine. The SOS response was induced in M9 minimal medium by addition of 1 μg ml−1 mitomycin C. Expression of the PA1/O4/O3 promoter was induced by the addition of 2 mM IPTG and expression of the PBAD promoter was induced by the addition of 0.2% arabinose.

Rates of protein synthesis

Cells were grown at 37°C in M9 minimal medium + 0.5% glycerol and amino acids in defined concentrations to an optical density (OD450) of 0.5. The cultures were diluted 10 times and arabinose was added at an OD of 0.3. Samples of 0.5 ml were added to 5 μCi of [35S]methionine and after 1 min of incorporation, samples were chased for 10 min with 0.5 mg of cold methionine. The samples were harvested and resuspended in 200 μl cold 20% trichloracetic acid and were centrifuged at 20 000 g for 30 min at 4°C. The samples were washed twice with 200 μl cold 96% ethanol. Precipitates were transferred to vials and the amount of incorporated radioactivity was counted in a liquid scintillation counter.

Northern blot and primer extension analysis

Cells were grown in Luria–Bertani medium at 37°C. At an OD450 of 0.5, the cultures were diluted 10 times and grown to an OD of 0.5 and transcription of the toxin genes was induced by the addition of 0.2% arabinose. To inhibit translation, CML (50 μg ml−1) was added. For Northern analysis, total RNA was fractionated by PAGE (6% low-bis acrylamide), blotted to a Zeta-probe nylon membrane and hybridized with a single-stranded 32P-labelled riboprobe complementary to the RNA of interest. For lpp mRNA hybridization, the radioactive probe was generated by T7 RNA polymerase using linearized plasmid DNA of pSC333 as the template. The ribopropes used to detect dksA and ompA mRNA were transcribed from a PCR fragments containing a complementary region of the dksA (constructed using the primers dksA probe-f and dksA T7 probe-r) and ompA (constructed using the primers T7/pmoA and pmoA-forw) genes. Primer extension analysis was used to map promoters and the cleavage patterns of the lpp, ompA, rpoD and dksA mRNAs, using 32P-labelled primers, following extension by reverse transcriptase. The primer (3 pmol) was labelled with 2 μl of [γ-32P]-ATP at a concentration of 6000 Ci mmol−1 by addition of 0.4 μl polynucleotide kinase (New England Biolabs) in polynucleotide kinase buffer and incubated for 1 h at 37°C. Labelled primer was hybridized to 10–20 μg total RNA and extended with reverse transcriptase (SuperScript II; Invitrogen). The labelled cDNA was fractionated by using a 6% polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, which was dried and placed on a PhosphorImager screen.

Reverse transcription qPCR

RNA was extracted from all cell samples using RNeasy mini-kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. cDNA synthesis was performed using a high-capacity cDNA reverse transcription kit (Applied Biosystems). qPCR reactions were run in triplicates simultaneously. Briefly, 10 ng cDNA was mixed with 0.3 μM primers and 10 μl of 2× PCR Master Mix for Sybr green kit from Eurogentec (Seraing, Belgium), and the qPCR was run on a LightCycler 480 real-time PCR system (Roche). Relative folds of expression were calculated using the qBase software using tatA and eutA as reference genes (Hellemans et al., 2007).

Acknowledgments

We thank Dagmar Iber, Kristoffer S. Winther and Martin Overgaard for stimulating discussions. This work was supported by The Danish National Research Foundation via the Centre for mRNP Biogenesis and Metabolism and the Wellcome Trust.

Supporting information

Additional supporting information may be found in the online version of this article.

Please note: Wiley-Blackwell are not responsible for the content or functionality of any supporting materials supplied by the authors. Any queries (other than missing material) should be directed to the corresponding author for the article.

References

- Baba T, Ara T, Hasegawa M, Takai Y, Okumura Y, Baba M, et al. Construction of Escherichia coli K-12 in-frame, single-gene knockout mutants: the Keio collection. Mol Syst Biol. 2006;2:2006.0008. doi: 10.1038/msb4100050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernhardt TG, de Boer PA. The Escherichia coli amidase AmiC is a periplasmic septal ring component exported via the twin-arginine transport pathway. Mol Microbiol. 2003;48:1171–1182. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03511.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blower TR, Fineran PC, Johnson MJ, Toth IK, Humphreys DP, Salmond GP. Mutagenesis and functional characterisation of the RNA and protein components of the toxIN abortive infection/toxin-antitoxin locus of Erwinia. J Bacteriol. 2009;191:6029–6039. doi: 10.1128/JB.00720-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown JM, Shaw KJ. A novel family of Escherichia coli toxin-antitoxin gene pairs. J Bacteriol. 2003;185:6600–6608. doi: 10.1128/JB.185.22.6600-6608.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budde PP, Davis BM, Yuan J, Waldor MK. Characterization of a higBA toxin-antitoxin locus in Vibrio cholerae. J Bacteriol. 2007;189:491–500. doi: 10.1128/JB.00909-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cashel M, Gentry D, Hernandez VJ, Vinella D. The stringent response. In: Neidthardt FC, editor. Escherichia coli and Salmonella. Washington, DC: American Society for Microbiology Press; 1996. pp. 1458–1496. [Google Scholar]

- Christensen SK, Gerdes K. RelE toxins from bacteria and Archaea cleave mRNAs on translating ribosomes, which are rescued by tmRNA. Mol Microbiol. 2003;48:1389–1400. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03512.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen SK, Gerdes K. Delayed-relaxed response explained by hyperactivation of RelE. Mol Microbiol. 2004;53:587–597. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04127.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen SK, Maenhaut-Michel G, Mine N, Gottesman S, Van Gerdes K, Mikkelsen M, et al. RelE, a global inhibitor of translation, is activated during nutritional stress. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:14328–14333. doi: 10.1073/pnas.251327898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen SK, Maenhaut-Michel G, Mine N, Gottesman S, Gerdes K, Van ML. Overproduction of the Lon protease triggers inhibition of translation in Escherichia coli: involvement of the yefM-yoeB toxin-antitoxin system. Mol Microbiol. 2004;51:1705–1717. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03941.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen SK, Pedersen K, Hansen FG, Gerdes K. Toxin-antitoxin loci as stress-response-elements: ChpAK/MazF and ChpBK cleave translated RNAs and are counteracted by tmRNA. J Mol Biol. 2003;332:809–819. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(03)00922-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen-Dalsgaard M, Gerdes K. Two higBA loci in the Vibrio cholerae superintegron encode mRNA cleaving enzymes and can stabilize plasmids. Mol Microbiol. 2006;62:397–411. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05385.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen-Dalsgaard M, Gerdes K. Translation affects YoeB and MazF messenger RNA interferase activities by different mechanisms. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:6472–6481. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Datsenko KA, Wanner BL. One-step inactivation of chromosomal genes in Escherichia coli K-12 using PCR products. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:6640–6645. doi: 10.1073/pnas.120163297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engelberg-Kulka H, Amitai S, Kolodkin-Gal I, Hazan R. Bacterial programmed cell death and multicellular behavior in bacteria. PLoS Genet. 2006;2:e135. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0020135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez De Henestrosa AR, Ogi T, Aoyagi S, Chafin D, Hayes JJ, Ohmori H, Woodgate R. Identification of additional genes belonging to the LexA regulon in Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol. 2000;35:1560–1572. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.01826.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francuski D, Saenger W. Crystal structure of the antitoxin-toxin protein complex relb-rele from methanococcus jannaschii. J Mol Biol. 2009;393:898–908. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2009.08.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu Z, Tamber S, Memmi G, Donegan NP, Cheung AL. Overexpression of MazFsa in Staphylococcus aureus induces bacteriostasis by selectively targeting mRNAs for cleavage. J Bacteriol. 2009;191:2051–2059. doi: 10.1128/JB.00907-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galvani C, Terry J, Ishiguro EE. Purification of the RelB and RelE proteins of Escherichia coli: RelE binds to RelB and to ribosomes. J Bacteriol. 2001;183:2700–2703. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.8.2700-2703.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Pino A, Christensen-Dalsgaard M, Wyns L, Yarmolinsky M, Magnuson RD, Gerdes K, Loris R. Doc of prophage P1 is inhibited by its antitoxin partner Phd through fold complementation. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:30821–30827. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M805654200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerdes K. Toxin-antitoxin modules may regulate synthesis of macromolecules during nutritional stress. J Bacteriol. 2000;182:561–572. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.3.561-572.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerdes K, Christensen SK, Lobner-Olesen A. Prokaryotic toxin-antitoxin stress response loci. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2005;3:371–382. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerdes K, Wagner EG. RNA antitoxins. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2007;10:117–124. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2007.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez Barrios AF, Zuo R, Hashimoto Y, Yang L, Bentley WE, Wood TK. Autoinducer 2 controls biofilm formation in Escherichia coli through a novel motility quorum-sensing regulator (MqsR, B3022) J Bacteriol. 2006;188:305–316. doi: 10.1128/JB.188.1.305-316.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gotfredsen M, Gerdes K. The Escherichia coli relBE genes belong to a new toxin-antitoxin gene family. Mol Microbiol. 1998;29:1065–1076. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00993.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guzman LM, Belin D, Carson MJ, Beckwith J. Tight regulation, modulation, and high-level expression by vectors containing the arabinose PBAD promoter. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:4121–4130. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.14.4121-4130.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes F. Toxins-antitoxins: plasmid maintenance, programmed cell death, and cell cycle arrest. Science. 2003;301:1496–1499. doi: 10.1126/science.1088157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes CS, Low DA. Signals of growth regulation in bacteria. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2009;12:667–673. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2009.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hazan R, Sat B, Engelberg-Kulka H. Escherichia coli mazEF-mediated cell death is triggered by various stressful conditions. J Bacteriol. 2004;186:3663–3669. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.11.3663-3669.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hellemans J, De Mortier GPA, Speleman F, Vandesompele J. qBase relative quantification framework and software for management and automated analysis of real-time quantitative PCR data. Genome Biol. 2007;8:R19. doi: 10.1186/gb-2007-8-2-r19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jørgensen MG, Pandey DP, Jaskolska M, Gerdes K. HicA of Escherichia coli defines a novel family of translation-independent mRNA interferases in bacteria and archaea. J Bacteriol. 2009;191:1191–1199. doi: 10.1128/JB.01013-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamada K, Hanaoka F. Conformational change in the catalytic site of the ribonuclease YoeB toxin by YefM antitoxin. Mol Cell. 2005;19:497–509. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawano M, Aravind L, Storz G. An antisense RNA controls synthesis of an SOS-induced toxin evolved from an antitoxin. Mol Microbiol. 2007;64:738–754. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2007.05688.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keseler IM, Bonavides-Martinez C, Collado-Vides J, Gama-Castro S, Gunsalus RP, Johnson DA, et al. EcoCyc: a comprehensive view of Escherichia coli biology. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:D464–D470. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitagawa M, Ara T, Arifuzzaman M, Ioka-Nakamichi T, Inamoto E, Toyonaga H, Mori H. Complete set of ORF clones of Escherichia coli ASKA library (a complete set of E. coli K-12 ORF archive): unique resources for biological research. DNA Res. 2005;12:291–299. doi: 10.1093/dnares/dsi012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li GY, Zhang Y, Inouye M, Ikura M. Inhibitory mechanism of Escherichia coli RelE-RelB toxin-antitoxin module involves a helix displacement near an mRNA interferase active site. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:14628–14636. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M809656200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGuffin LJ, Bryson K, Jones DT. The PSIPRED protein structure prediction server. Bioinformatics. 2000;16:404–405. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/16.4.404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKenzie GJ, Lee PL, Lombardo MJ, Hastings PJ, Rosenberg SM. SOS mutator DNA polymerase IV functions in adaptive mutation and not adaptive amplification. Mol Cell. 2001;7:571–579. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00204-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKenzie GJ, Magner DB, Lee PL, Rosenberg SM. The dinB operon and spontaneous mutation in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 2003;185:3972–3977. doi: 10.1128/JB.185.13.3972-3977.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magnuson RD. Hypothetical functions of toxin-antitoxin systems. J Bacteriol. 2007;189:6089–6092. doi: 10.1128/JB.00958-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masuda Y, Miyakawa K, Nishimura Y, Ohtsubo E. chpA and chpB, Escherichia coli chromosomal homologs of the pem locus responsible for stable maintenance of plasmid R100. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:6850–6856. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.21.6850-6856.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nariya H, Inouye M. MazF, an mRNA interferase, mediates programmed cell death during multicellular Myxococcus development. Cell. 2008;132:55–66. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.11.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Overgaard M, Borch J, Jorgensen MG, Gerdes K. Messenger RNA interferase RelE controls relBE transcription by conditional cooperativity. Mol Microbiol. 2008;69:841–857. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2008.06313.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Overgaard M, Borch J, Gerdes K. RelB and RelE of Escherichia coli form a tight complex that represses transcription via the ribbon-helix-helix motif in RelB. J Mol Biol. 2009;394:183–196. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2009.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pandey DP, Gerdes K. Toxin – antitoxin loci are highly abundant in free-living but lost from host-associated prokaryotes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:966–976. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen K, Christensen SK, Gerdes K. Rapid induction and reversal of a bacteriostatic condition by controlled expression of toxins and antitoxins. Mol Microbiol. 2002;45:501–510. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2002.03027.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen K, Zavialov AV, Pavlov MY, Elf J, Gerdes K, Ehrenberg M. The bacterial toxin RelE displays codon-specific cleavage of mRNAs in the ribosomal A site. Cell. 2003;112:131–140. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)01248-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prysak MH, Mozdzierz CJ, Cook AM, Zhu L, Zhang Y, Inouye M, Woychik NA. Bacterial toxin YafQ is an endoribonuclease that associates with the ribosome and blocks translation elongation through sequence-specific and frame-dependent mRNA cleavage. Mol Microbiol. 2009;71:1071–1087. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2008.06572.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt O, Schuenemann VJ, Hand NJ, Silhavy TJ, Martin J, Lupas AN, Djuranovic S. prlF and yhaV encode a new toxin-antitoxin system in Escherichia coli. J Mol Biol. 2007;372:894–905. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.07.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sevin EW, Barloy-Hubler F. RASTA-Bacteria: a web-based tool for identifying toxin-antitoxin loci in prokaryotes. Genome Biol. 2007;8:R155. doi: 10.1186/gb-2007-8-8-r155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah D, Zhang Z, Khodursky A, Kaldalu N, Kurg K, Lewis K. Persisters: a distinct physiological state of E. coli. BMC Microbiol. 2006;6:53. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-6-53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sperandio V, Torres AG, Kaper JB. Quorum sensing Escherichia coli regulators B and C (QseBC): a novel two-component regulatory system involved in the regulation of flagella and motility by quorum sensing in E. coli. Mol Microbiol. 2002;43:809–821. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2002.02803.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takagi H, Kakuta Y, Okada T, Yao M, Tanaka I, Kimura M. Crystal structure of archaeal toxin-antitoxin RelE-RelB complex with implications for toxin activity and antitoxin effects. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2005;12:327–331. doi: 10.1038/nsmb911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Traxler MF, Summers SM, Nguyen HT, Zacharia VM, Hightower GA, Smith JT, Conway T. The global, ppGpp-mediated stringent response to amino acid starvation in Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol. 2008;68:1128–1148. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2008.06229.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Melderen L, Saavedra De Bast M. Bacterial toxin-antitoxin systems: more than selfish entities? PLoS Genet. 2009;5:e1000437. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Melderen L, Bernard P, Couturier M. Lon-dependent proteolysis of CcdA is the key control for activation of CcdB in plasmid-free segregant bacteria. Mol Microbiol. 1994;11:1151–1157. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb00391.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogel J, Argaman L, Wagner EG, Altuvia S. The small RNA IstR inhibits synthesis of an SOS-induced toxic peptide. Curr Biol. 2004;14:2271–2276. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wade JT, Reppas NB, Church GM, Struhl K. Genomic analysis of LexA binding reveals the permissive nature of the Escherichia coli genome and identifies unconventional target sites. Genes Dev. 2005;19:2619–2630. doi: 10.1101/gad.1355605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waters LS, Storz G. Regulatory RNAs in bacteria. Cell. 2009;136:615–628. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.01.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winther KS, Gerdes K. Ectopic production of VapCs from Enterobacteria inhibits translation and trans-activates YoeB mRNA interferase. Mol Microbiol. 2009;72:918–930. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2009.06694.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi Y, Park JH, Inouye M. MqsR, a crucial regulator for quorum sensing and biofilm formation, is a GCU-specific mRNA interferase in Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:28746–28753. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.032904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Inouye M. The inhibitory mechanism of protein synthesis by YoeB, an Escherichia coli toxin. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:6627–6638. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M808779200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Zhang J, Hoeflich KP, Ikura M, Qing G, Inouye M. MazF cleaves cellular mRNAs specifically at ACA to block protein synthesis in Escherichia coli. Mol Cell. 2003;12:913–923. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00402-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Zhu L, Zhang J, Inouye M. Characterization of ChpBK, an mRNA interferase from Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 2005a;280:26080–26088. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M502050200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Zhang J, Hara H, Kato I, Inouye M. Insights into the mRNA cleavage mechanism by MazF, an mRNA interferase. J Biol Chem. 2005b;280:3143–3150. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M411811200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Yamaguchi Y, Inouye M. Characterization of YafO, an Escherichia coli toxin. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:25522–25531. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.036624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.