Abstract

The lipid A and core regions of the lipopolysaccharide in Rhizobium leguminosarum, a nitrogen-fixing plant endosymbiont, are strikingly different from those of Escherichia coli. In R. leguminosarum lipopolysaccharide, the inner core is modified with three galacturonic acid (GalA) moieties, two on the distal 3-deoxy-D-manno-octulosonic acid (Kdo) unit and one on the mannose residue. Here we describe the expression cloning of three novel GalA transferases from a 22-kb R. leguminosarum genomic DNA insert-containing cosmid (pSGAT). Two of these enzymes modify the substrate, Kdo2-[4′-32P]lipid IVA and its 1-dephosphorylated derivative on the distal Kdo residue, as indicated by mild acid hydrolysis. The third enzyme modifies the mannose unit of the substrate mannosyl-Kdo2-1-dephospho-[4′-32P]lipid IVA. Sequencing of a 7-kb subclone derived from pSGAT revealed three putative membrane-bound glycosyltransferases, now designated RgtA, RgtB, and RgtC. Transfer by tri-parental mating of these genes into Sinorhizobium meliloti 1021, a strain that lacks these particular GalA residues, results in the heterologous expression of the GalA transferase activities seen in membranes of cells expressing pSGAT. Reconstitution experiments with the individual genes demonstrated that the activity of RgtA precedes and is necessary for the subsequent activity of RgtB, which is followed by the activity of RgtC. Electrospray ionization-tandem mass spectrometry and gas-liquid chromatography of the product generated in vitro by RgtA confirmed the presence of a GalA moiety. No in vitro activity was detected when RgtA was expressed in Escherichia coli unless Rhizobiaceae membranes were also included.

Lipopolysaccharide (LPS),3 recently reclassified as a saccharolipid glycan (1), is a major component of the outer membranes of Gram-negative bacteria. The structure of LPS can be divided into three domains as follows: 1) the lipid A moiety, which functions as the hydrophobic anchor; 2) the nonrepeating core oligosaccharide; and 3) the distal O-antigen polymer (2-6). LPS acts as a barrier to antibiotics and helps bacteria resist complement-mediated lysis (7, 8). Lipid A and two 3-deoxy-D-manno-octulosonic acid (Kdo) residues usually represent the minimal LPS substructure required for bacterial viability. The O-antigen and a portion of the core are not required for growth. However, all three domains are vital for the successful infection of both plants and animals (3, 5).

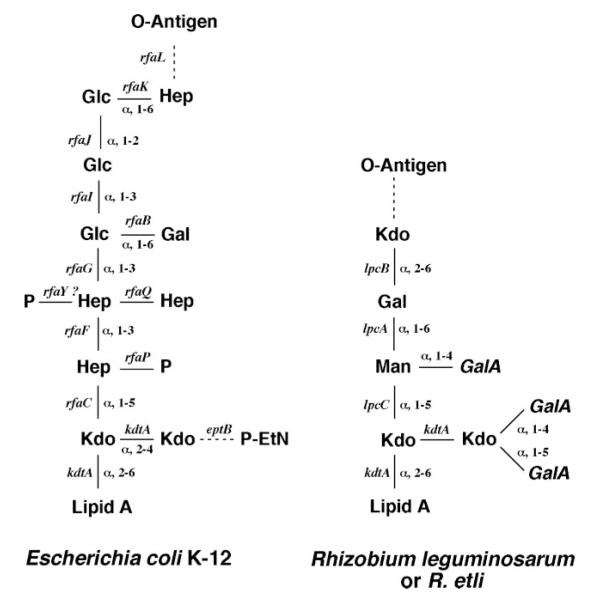

The LPS of the nitrogen-fixing plant endosymbiont, Rhizobium leguminosarum, is different from that of enteric bacteria, such as Escherichia coli. Prominent alterations in the lipid A moiety include the lack of phosphate groups, the oxidation of the proximal glucosamine-sugar to an aminogluconate residue, and a secondary acylation with an unusual 28-carbon fatty acyl chain (9-13). At the level of the inner core, R. leguminosarum lacks the L-glycero-D-manno-heptose found in E. coli and Salmonella, but instead, it contains the structurally related mannose residue (Fig. 1) (14-16). Another difference is the presence of several galacturonic acid (GalA) moieties in R. leguminosarum (Fig. 1). Two GalA residues are attached to the distal Kdo, and a third residue is linked to the core mannose (17), whereas the lipid A 4′-phosphate moiety is replaced with a fourth GalA residue (9, 11, 12, 14, 18).

FIGURE 1. Partial structures of the R. leguminosarum and E. coli core oligosaccharides.

The two Kdo residues closest to lipid A and the α-(1–5) linkage of the heptose or mannose attached to the inner Kdo are conserved. Dashed lines represent partial substituents. The genes encoding the enzymes responsible for generating the relevant linkages are indicated. The galacturonic acid residues in R. leguminosarum are shown in italics. The abbreviations used are as follows: Glc, D-glucose; Gal, D-galactose; Hep; L-glycero-D-manno-heptose; GlcNAc, N-acetyl-D-glucosamine; Man, mannose.

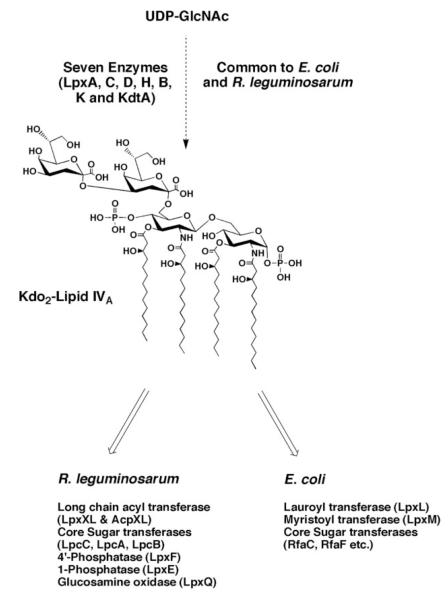

Despite differences in LPS structure, E. coli and R. leguminosarum share the first seven enzymes that synthesize the key conserved intermediate, Kdo2-lipid IVA (Fig. 2) (3). Additional modifying enzymes in R. leguminosarum are responsible for the subsequent divergence in Kdo2-lipid IVA processing. Using enzymatic and expression cloning methods, we have previously characterized a 1-phosphatase, a 4′-phosphatase, a long chain acyl transferase, several sugar nucleotide-dependent core glycosyltransferases, and a glucosamine oxidase (13, 15, 16, 19-22).

FIGURE 2. Structure of the conserved intermediate Kdo2-lipid IVA and its enzymatic processing in extracts of R. leguminosarum versus E. coli.

The seven enzymes leading to the intermediate Kdo2-lipid IVA are conserved in E. coli and R. leguminosarum. Key enzymes that have been identified to date as being required for the subsequent processing of Kdo2-lipid IVA are indicated.

The significance of the GalA residues present in the R. leguminosarum LPS core is unclear. In E. coli LPS, the negatively charged phosphate groups play an important role in maintaining the barrier function of the outer membrane by binding to divalent cations, thereby cross-linking adjacent LPS molecules (6, 8). In R. leguminosarum, the GalA residues appear to function as phosphate surrogates and may enhance Ca2+-mediated binding to root cells. GalA units are also found in the core oligosaccharide of Rhizobium etli, Klebsiella pneumoniae, and Plesiomonas shigelloides O54, as well as in the lipid A of Aquifex pyrophilus and Mesorhizobium huakuii (9, 23-27). Because many of these bacteria are environmental isolates, the substitution of phosphate with GalA is speculated to give these organisms an ecological advantage in habitats low in phosphate (8, 24). Recent studies with K. pneumoniae mutants suggest that the GalA units are indeed required for maintenance of outer membrane stability (24, 28).

GalA is also a major component of plant cell wall pectic polysaccharides (29, 30). Pectins are the first plant entity encountered by plant pathogens and symbionts, and changes in pectin metabolism have been implicated in triggering plant defense responses (30). Plant pathogen defense pathways show some similarities to the innate immune systems of mammals and Drosophila (31-33). The presence of GalA units on the LPS of plant endosymbionts like R. leguminosarum might protect them from the immune response of their host. The identification of the genes encoding the GalA transferases should enable the re-engineering of LPS structures in Gram-negative bacteria and provide insights into the functions of GalA substitutions.

We now report the expression cloning of the genes encoding the three GalA transferases that modify the LPS inner core in R. leguminosarum. By assaying lysates of individual clones of an R. leguminosarum 3841 cosmid-based genomic DNA library (34) harbored in Sinorhizobium meliloti 1021, we identified a single clone capable of directing the overexpression of these enzymes. The enzymes are membrane-bound and are detected with the LPS precursor substrates, Kdo2-[4′-32P]lipid IVA, Kdo2-1-dephospho-[4′-32P]lipid IVA, and/or mannosyl-Kdo2-1-dephospho-[4′-32P]lipid IVA. Sequencing of a 7-kb DNA insert, derived from the positive clone, led to the identification of three candidate structural genes, designated rgtA, rgtB, and rgtC (for Rhizobium galacturonic acid transferase). The Rgt proteins identified exhibit distant similarity to the E. coli lipid A 4-amino-4-deoxy-L-arabinosetransferase, ArnT (35, 36), both in primary sequence and predicted membrane topography. Mass spectrometry of the product generated by RgtA in vitro was used to confirm the attachment of a GalA unit to the outer Kdo residue of Kdo2-1-dephospho-lipid IVA.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Chemicals and Materials

[γ-32P]ATP was obtained from PerkinElmer Life Sciences. Silica Gel 60 (0.25 mm) TLC plates were from Merck. Chloroform, ammonium acetate, and sodium acetate were from EM Science. Triton X-100, Nonidet P-40, and the BCA protein determination kit were purchased from Pierce. Yeast extract and tryptone were from Difco. All other chemicals were reagent grade and were obtained from either Sigma or Mallinckrodt.

Bacterial Strains and Growth Conditions

All bacterial strains used in this study are described in Table 1. All Rhizobium and Sinorhizobium strains were grown at 30 °C in TY medium (5 g/liter tryptone, 3 g/liter yeast extract, and 10 mM CaCl2), supplemented with the antibiotics nalidixic acid (Nal, 20 μg/ml) and streptomycin (Str, 200 μg/ml). The clones and subclones in S. meliloti 1021 were also grown with tetracycline (Tet, 12.5 μg/ml).

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain/plasmid | Genotype or description | Source or Ref. |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| R. leguminosarum 3841 | Wild type strain 300 biovar viciae Smr | 66 |

| S. meliloti 1021 | SU47 Smr | S. Long |

| E. coli | ||

| HB101 |

hsdS20 supE44 ara14 galK2 lacY1 proA2 rpsL20 (Smr) xyl-5 recA1 endA1 gyrA96 thi-1 hsdR17 supE44 relA1 |

Invitrogen |

| XL1-Blue | lac [F’ proAB lacIqZΔM15 Tn10 (Tetr) | Stratagene |

| XLI-Blue MRF’ Kan | Δ(mcrA)183Δ(mcrCB-hsdSMR-mrr)173 endA1 supE44 thi-1 recA1 gyrA96 relA1 lac [F’ proABlacIqZΔM15 Tn5 (Kanr)] |

Stratagene |

| MT616 | pRK2013 Camr. Kan::Tn9 containing strain for tri-parental mating | 67 |

| NovaBlue (DE3) | E. coli host strain used for expression | Novagen |

| Plasmids | ||

| pLAFR-1 | Broad host range P-group cloning vector, mobilizable RK2 cosmid, Tetr | 68 |

| pRK404a | Shuttle vector, Tetr | 69 |

| pET-23a | E. coli expression vector, T7lac promoter, Ampr | Novagen |

| pSGAT | pLAFR-1 derivative carrying a 22-kb fragment of R. leguminosarum 3841 genomic DNA, which includes rgtA and rgtB |

This work |

| pMKGE | pRK404a derivative carrying a 7-kb EcoRI fragment from pSGAT, which includes rgtA and rgtB | This work |

| pRgtA | pET-23a derivative harboring rgtA behind the T7lac promoter | This work |

| pRK-RgtA | rgtA in pRK404a | This work |

| pRK-RgtB | rgtB in pRK404a | This work |

| pRK-RgtC | rgtC in pRK404a | This work |

E. coli NovaBlue (DE3) strains (Novagen), harboring either the empty vector control (pET23a) or the hybrid plasmid (pRgtA), were grown from a single colony in 200 ml of LB broth (10 g/liter tryptone, 5 g/liter yeast extract, and 10 g/liter NaCl), supplemented with ampicillin (100 μg/ml), at 37 °C until the A600 reached ~0.6. The culture was split into two equal portions, one of which was induced with 1 mM isopropyl 1-thio-β-D-galactopyranoside. Both cultures were further incubated with shaking at 225 rpm for an additional 4 h at 25 °C.

Molecular Biology Protocols

Plasmid and cosmid DNA was isolated using the Qiagen spin column prep kit. DNA fragments were recovered from agarose gels using the QIAquick gel extraction kit. Genomic DNA was isolated using the protocol for bacterial cultures in the Easy-DNA™ kit (Invitrogen). Pfu DNA polymerase (Stratagene), T4 DNA ligase (Invitrogen), restriction endonucleases (New England Biolabs), and shrimp alkaline phosphatase (U. S. Biochemical Corp.) were used according to the manufacturers’ instructions. The Duke University DNA Analysis Facility sequenced double-stranded DNA with an ABI Prism 377 instrument. All primers were obtained from MWG Biotec. Chemically competent cells for transformation were purchased from Invitrogen (E. coli HB101) or Stratagene (E. coli XL1Blue and XL1Blue-MRF’ Kan). Plasmids or cosmids were introduced into S. meliloti 1021 by tri-parental mating, as outlined below. E. coli strain 803 or HB101 served as plasmid or cosmid donors, respectively, and E. coli MT616 (Table 1) provided the transfer function.

Preparation of Cell-free Extracts and Membranes

Mid-logarithmic phase cells were harvested by centrifugation at 4,000 × g for 20 min at 4 °C. The cell pellets were resuspended in prechilled 50 mM HEPES, pH 7.5, to give a final protein concentration of 5–10 mg/ml. To make crude cell extracts, the cells were broken by two passages through a French pressure cell at 10,000 p.s.i. Cellular debris was removed by centrifugation at 7,000 × g for 20 min at 4 °C. Membranes were prepared from the supernatant by ultracentrifugation at 100,000 × g for 60 min at 4 °C, and the resulting high speed supernatant (cytosol) was stored at -80 °C. The membrane pellet was resuspended in 50 mM HEPES, pH 7.5, and subjected to another ultracentrifugation step. The final membrane pellet was resuspended in 50 mM HEPES, pH 7.5, to give a final protein concentration of ~5–10 mg/ml and stored in aliquots at -80 °C. The BCA assay (37) was used to determine protein concentration.

Preparation of Radiolabeled Substrates

Kdo2-[4′-32P]lipid IVA was generated from [γ-32P]ATP and the tetra-acyl disaccharide 1-phosphate acceptor, using membranes of cells that overexpress E. coli 4′-kinase (LpxK) (38), and purified E. coli Kdo-transferase (KdtA) following the published protocol (39).

Kdo2-1-dephospho-[4′-32P]lipid IVA was generated in the same reaction mixture in an additional step. The supplementary components added were 50 mM MES, pH 6.5, 0.1% Triton X-100, and 0.4 mg/ml Triton X-100-solubilized pLpxE/NovaBlue (DE3) membranes (22) in a total volume of 30 μl, making the final reaction volume 130 μl. The reaction was allowed to proceed at 30 °C for 20 min. This was followed by two subsequent additions of 0.4 mg/ml solubilized pLpxE/NovaBlue (DE3) membranes with 20-min incubations at 30 °C.

Mannosyl-Kdo2-1-dephospho-[4′-32P]lipid IVA was also generated from Kdo2-[4′-32P]lipid IVA in the same reaction mixture. However, the mannosylation step preceded the dephosphorylation step. The supplementary components added for mannosylation were 50 mM HEPES, pH 7.5, 0.1% Triton X-100, 1 mM GDP-mannose, and 0.3–0.5 mg/ml pIJ1848/S. meliloti 1021 membranes (15, 40) in a total volume of 20 μl, making the final reaction volume 120 μl. The reaction was allowed to proceed at 30 °C for 30 min. This was followed by the addition of another 0.3–0.5 mg/ml membranes with 30 min of incubation at 30 °C. Dephosphorylation was carried out subsequently by adding 50 mM MES, pH 6.5, 0.1% Triton X-100, and 0.4 mg/ml solubilized pLpxE/NovaBlue (DE3) membranes (22) in a total volume of 30 μl, making the final reaction volume 150 μl. The reaction was allowed to proceed at 30 °C for 20 min. This was followed by two subsequent additions of 0.4 mg/ml solubilized pLpxE/NovaBlue (DE3) membranes with 20-min incubations at 30 °C. All radiolabeled substrates were purified by preparative TLC, resuspended in 25 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.8, containing 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM EGTA, and 0.1% Triton X-100, and stored at -20 °C (39).

Unlabeled (carrier) Kdo2-1-dephospho-lipid IVA was prepared from unlabeled 100 μM Kdo2-lipid IVA under the conditions described above. Unlabeled Kdo2-lipid IVA was obtained by following published procedures (41).

Galacturonic Acid Transferase Assay

Standard assay conditions for the GalA transferase activity are as follows. The reaction mixture (10–20 μl) contained 50 mM MES, pH 6.5, 0.05% Nonidet P-40, 2 mM MgCl2, and 2.5 μM Kdo2-[4′-32P]lipid IVA or Kdo2-1-dephospho-[4′-32P]lipid IVA (50,000 cpm/nmol). Washed membranes were used as the enzyme source. Assay mixtures were incubated at 30 °C for varying times, and reactions were terminated by spotting 4-μl portions onto Silica Gel 60 TLC plates that were developed in the solvent system chloroform, pyridine, 88% formic acid, water (30:70:16:10, v/v). After drying and overnight exposure of the plate to a PhosphorImager screen, product formation was detected and quantified with PhosphorImager (Storm 840, Amersham Biosciences), equipped with ImageQuant software.

Tri-parental Mating for Transfer of Cosmids or Plasmids

S. meliloti 1021 (recipient strain) was grown on TY agar with Nal and Str selection for 24–36 h at 30 °C. The E. coli strain 803, harboring the cosmid library, or the E. coli strain HB101, harboring the plasmid subclones, was grown on LB agar containing Tet for 12 h. E. coli MT616 (helper strain) was grown on LB agar with chloramphenicol (30 μg/ml) for 12 h. The bacteria were scraped off their respective plates and resuspended in TY medium (0.5 ml per plate) with no antibiotics. S. meliloti 1021, the E. coli strain plasmid or cosmid donor, and E. coli MT606 were mixed in the ratio 3:1:1 (v/v). A portion of the mixture (0.5 ml) was then placed at the center of a TY agar plate with no antibiotic selection. Mating was allowed to occur by leaving the plate upside down for 36–48 h at 30 °C. The bacteria were scraped off and resuspended in TY medium (0.5 ml), containing no antibiotics. A small volume of this mixture (50–100 μl) was then streaked out on a TY agar plate, supplemented with Nal, Str, and Tet. The remaining cells were stored at -80 °C as a glycerol stock (20% glycerol). The plates were incubated at 30 °C for 72 h to obtain individual colonies.

Screening of a R. leguminosarum 3841 Genomic Library for GalA Transferase Activities

The cosmid (pLAFR-1) library of R. leguminosarum 3841 genomic DNA (~20–25-kb inserts) harbored in E. coli 803 was provided by Dr. J. Downie of the John Innes Institute (Norwich, UK). Because R. leguminosarum promoters are not well recognized by E. coli RNA polymerase, colony lysates of the E. coli host could not be assayed directly. Accordingly, the entire library was transformed by tri-parental mating into S. meliloti 1021 (13). The E. coli strain 803 served as the cosmid donor, whereas E. coli MT616, the helper, provided transfer functions (Table 1).

To facilitate examination of a large number of library members, the clones were analyzed in pools. The glycerol stock of the mating mixture was thawed and appropriately diluted to obtain 50–100 colonies per TY agar plate, supplemented with Nal, Str, and Tet. The plates were incubated for 72 h at 30 °C to obtain single colonies. Individual colonies were inoculated into separate wells of a 96-well microtiter plate containing 150 μl of TY medium supplemented with Nal, Str, and Tet. Each microtiter plate was incubated at 30 °C with constant shaking for 40 h. To ensure consistency, growth was monitored until the A600 was greater than 0.5. Next, 50 μl from each well was transferred to another microtiter plate, adjusted to 20% glycerol, and stored as a stock at -80 °C. The remaining 100 μl of cells was harvested by centrifugation at 3,660 × g for 20 min at 4 °C. The supernatant was decanted, and the cell pellets were resuspended in 50 μl of 50 mM HEPES, pH 7.5. The pellets were lysed with lysozyme (1 mg/ml) and EDTA (10 mM) for 60 min at 4 °C. Portions of the lysates (5 μl from each well) from four microtiter plates were combined to give 96 pools of four lysates in a fresh microtiter plate (20 μl per well final volume).

The pooled lysates were assayed for their ability to modify Kdo2-[4′-32P]lipid IVA as follows. A 96-well microtiter plate was prepared in which each well contained 2 μl of 250 mM MES buffer, pH 6.5, 0.25% Nonidet P-40, 10 mM MgCl2, 1.0 μM Kdo2-[4′-32P]lipid IVA (50,000 cpm/nmol). Finally, 8 μl of pooled cell lysate was added to give a final volume of 10 μl. These plates were incubated at 30 °C for 2 h, and a portion of each reaction mixture (5 μl) was spotted onto a TLC plate. A negative control reaction with only S. meliloti crude extract was also spotted on each plate. After drying the spots with a stream of cool air for 20 min, the plates were developed and analyzed as described above.

Subcloning of the 22-kb Insert in pSGAT

The cosmid pSGAT and the shuttle vector (pRK404a), used for subcloning, were subjected to restriction digestion with either EcoRI or HindIII at 37 °C for 1 h. The digested vector (pRK404a) was dephosphorylated by shrimp alkaline phosphatase treatment (1 h, 37 °C), followed by heat inactivation of the enzyme (65 °C, 20 min). EcoRI and HindIII digestion of S. meliloti 1021/pSGAT resulted in the release of several fragments, including the 21-kb linearized cosmid vector (pLAFR-1). The fragment sizes from the EcoRI digestion were 7, 3.3, and 2.5-kb, whereas those from the HindIII digestion were 10, 4, and 3 kb. One EcoRI fragment (7-kb) and one HindIII fragment (4-kb) were selected for subcloning. The fragments were isolated, purified, and ligated into pRK404a (1:3, vector/insert) in a final volume of 20 μl (16 °C, overnight). A portion of the ligation mixture (10 μl) was used to transform a 50–100-μl aliquot of E. coli HB101 competent cells (Invitrogen). Plasmid-containing cells were selected by growth at 37 °C on LB agar plates supplemented with Tet. Resistant colonies were screened for the desired inserts by restriction digestion. Subclones were designated pMKGE or pMKGH (containing the 7-kb EcoRI insert or the 4-kb HindIII insert, respectively).

Each plasmid was transferred from HB101 into S. meliloti 1021 by tri-parental mating and selected on TY agar plates containing Nal, Str, and Tet. Lysates from these strains were screened for GalA transferase activity.

The DNA insert from pMKGE was purified, partially sequenced, and aligned with the R. leguminosarum 3841 genome. The complete sequence was evaluated with the ORF finder program of NCBI (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov) (42) for coding sequences.

Mild Acid Hydrolysis of the Reaction Product

Two 40-μl reaction mixtures were prepared containing 50 mM HEPES, pH 7.5, 0.05% Nonidet P-40, 2 mM MgCl2, and Kdo2-[4′-32P]lipid IVA (50,000 cpm/nmol). Reaction I contained no protein and reaction II contained 0.25 mg/ml membrane protein from S. meliloti 1021/pMKGE. The reactions were incubated at 30 °C for 80 min to ensure almost complete conversion of substrate to product. For mild acid hydrolysis, 10 μl of each reaction mixture was mixed with 4 μl of 10% SDS and 26 μl of 50 mM sodium acetate, pH 4.5, and incubated in a boiling water bath. At various time points, 4-μl samples were withdrawn and spotted onto a TLC plate, developed, and quantified as described (40, 43).

Subcloning of RgtA, RgtB, and RgtC

PCR-amplified DNA fragments containing the R. leguminosarum rgtA, rgtB, and rgtC genes were cloned into the pET23a (Novagen) vector behind the T7 promoter (supplemental Fig. 1). The forward primers for each gene (RgtAFor, RgtBFor, and RgtCFor) (Table 2) were synthesized with a clamp region, an NdeI restriction site (in boldface), and a match of the coding strand starting at the translation initiation site. The reverse primers (RgtARev, RgtBRev, and RgtARev) (Table 2) were designed with a clamp region, an EcoRI restriction site (in boldface), and a match to the anti-coding strand that included the stop codon (italicized). The PCR consisted of 200 ng of plasmid DNA template (pSGAT), 200 ng of each primer, 10 μM dNTPs, 1× Sigma PCR buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.3, 50 mM KCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 0.001% gelatin), and 1 unit of Pfu DNA polymerase in a total reaction volume of 50 μl. The reaction was subjected to a hot start (94 °C, 5 min) followed by 25 cycles of denaturation (94 °C, 1 min), annealing (55 °C, 1 min), and extension (72 °C, 2 min). After the 25th cycle, a 10-min extension time was used. The gel-purified (1% agarose) PCR product was digested with NdeI and EcoRI and ligated into a NdeI/EcoRI-digested, shrimp alkaline phosphatase-treated pET23a vector. The resulting pRgtA, pRgtB, and pRgtC constructs were transformed into XL1Blue competent cells (Stratagene). The inserts were confirmed by DNA sequencing. The plasmids were then transformed into the E. coli expression strain NovaBlue (DE3).

TABLE 2.

Primers used in this study

| Primer name | Sequencea | Restriction site |

|---|---|---|

| RgtAFor | ATATAGTACACATATGCTGGAGCGCGCGACGA | NdeI |

| RgtBFor | TATGCTAGCCATATGACCGAGAGCAACCGT | NdeI |

| RgtCFor | TGGAGATCGCATATGTTGGAGCGGATTACC | NdeI |

| RgtARev | TCGGTCATCGAATTCCTATCTGGTCTCCGG | EcoRI |

| RgtBRev | TGATTGCGCGAATTCTCAGCCAGGCTGATT | EcoRI |

| RgtCRev | TAAAAATACGAATCCTCAGGGCGCCAGGCAGGTG | EcoRI |

| RgtA-RKFor | CGCGCGGATCCAGGAGGAATTTAAAATGCTGGAGCGCGCGACGAGGACGATTAA | BamHI |

| RgtB-RKFor | CGCGCGGATCCAGGAGGAATTTAAAATGACCGAGAGCAACCGTCGCGACAT | BamHI |

| RgtC-RKFor | GCGCGCAAGCTTAGGAGGAATTTAAAATGTTGGAGCGGATTACCAGAAGC | HindIII |

Restriction sites introduced in primers are indicated in boldface, and the termination sites introduced are indicated in italics.

For transfer into S. meliloti, the genes were subcloned into the shuttle vector pRK404a (supplemental Fig. 1). First, the genes were PCR-amplified from their respective pET constructs using new forward primers but the same reverse primers. The newly designed forward primers (RgtA-RKFor, RgtB-RKFor, and RgtC-RKFor; Table 2) had a clamp region, an appropriate restriction site (BamHI for RgtA and RgtB and HindIII for RgtC) (in boldface), and a match of the coding strand upstream of the ribosome-binding site. Amplification was carried out as before. The PCR product was gel-purified, digested (BamHI or HindIII and EcoRI), and ligated into a double-digested, shrimp alkaline phosphatase-treated pRK404a. The resulting pRK-RgtA, pRK-RgtB, and pRK-RgtC plasmids were transformed into HB101 competent cells. The inserts were confirmed by DNA sequencing. The plasmids were transferred into S. meliloti 1021 by tri-parental mating.

In Vitro Product Preparation and Purification

Product I’ was prepared from 0.3 mg of Kdo2-[1-dephospho]lipid IVA and purified by DEAE-cellulose column chromatography. A 7-ml GalA transferase reaction mixture, containing 25 μM Kdo2-[1-dephospho]lipid IVA, 0.5 mg/ml S. meliloti 1021/pMKGE membranes, 50 mM MES, pH 6.5, 0.1% Triton X-100, and 2 mM MgCl2, was incubated on a rotary shaker at 30 °C for 2 h. Subsequently, another 0.5 mg/ml membrane and 0.1% Triton X-100 was added, and the mixture was allowed to incubate for another 2 h at 30 °C. The mixture was converted to a two-phase acidic Bligh-Dyer system (44) by the addition of 8.9 ml of chloroform, 8.9 ml of methanol, 0.8 ml of 1 M HCl, and 0.2 ml H2O. The lower phase was recovered, and the upper phase was washed once with 8.9 ml of fresh lower phase from a two-phase acidic Bligh-Dyer mixture. The lipids in the pooled lower phases were neutralized with 2–3 drops of pyridine and dried under a stream of nitrogen. The dried lipids were redissolved in 5 ml of the solvent system chloroform, methanol, water (2:3:1, v/v) and loaded onto a pre-equilibrated 0.5-ml DEAE-cellulose column in the acetate form. After application of the sample, the column was washed with 5 column volumes of chloroform, methanol, water (2:3:1, v/v). The product was then eluted with 5 column volumes of the same solvent system but with the aqueous portion consisting of 60, 120, 240 or 480 mM ammonium acetate, in ascending order. Each elution step was collected as one fraction of 2.5 ml. The fractions were then converted to a two-phase acidic Bligh-Dyer mixture by addition of appropriate amounts of chloroform, water, and 1 M HCl. The lower phases from each fraction were recovered, and the upper phases were washed once with fresh lower phase. The pooled lower phases from each fraction were neutralized with pyridine, dried under a stream of nitrogen, and stored at -20 °C.

ESI/MS Analysis of the Product Generated in Vitro

All mass spectra were acquired on a QSTAR XL quadrupole time-of-flight tandem mass spectrometer (ABI/MDS-Sciex, Toronto, Canada), equipped with an electrospray ionization source. Spectra were acquired in the negative ion mode and typically were the accumulation of 60 scans from 200 to 2000 atomic mass units. For MS analysis, the DEAE-cellulose-purified products were dissolved in 200 μl of chloroform/methanol (4:1, v/v). Typically, 20 μl of this solution was diluted into 200 μl of chloroform/methanol (1:1, v/v) and infused into the ion source at 5–10 μl/min. The negative ion ESI/MS was carried out at -4200 V. In the MS/MS mode, collision-induced dissociation tandem mass spectra were obtained using a collision energy of -80 V (laboratory frame of energy). Nitrogen was used as the collision gas. Data acquisition and analysis were performed using Analyst QS software.

GC/MS Analysis of the Product Generated in Vitro

The DEAE-cellulose purified products were hydrolyzed in acidic methanol, N-acetylated, and converted to trimethylsilyl esters following a published procedure (12). Standards of Kdo, GalA, and GlcA were purchased from Sigma and prepared for GC/MS under identical conditions.

GC/MS was performed using a Finnigan Trace MS, coupled with a Trace GC 2000 gas chromatograph. The column used was a 30-m RTX-5MS (0.25 mm internal diameter; 0.25 mm phase thickness) from Restek (Bellefonte, PA). Helium was used as the carrier gas with a constant flow rate of 1 ml/min. The gas chromatography program started with the column oven temperature being held at 100 °C for 3 min, followed by an increase to 325 °C at a rate of 20 °C/min. The column was then held at 325 °C for 3 min. The injector was operated in the split mode (1:20 split), and the temperature of the injection port was kept at 200 °C. The instrument was operated in the electron ionization mode with the electron energy set at 70 eV.

RESULTS

Screening of a R. leguminosarum Genomic DNA Library for Clones Overexpressing Kdo2-Lipid IVA Modifying Activities

An expression cloning strategy was used to screen for putative GalA transferases (13). A cosmid library of R. leguminosarum 3841 genomic DNA (~20–25-kb inserts) in pLAFR-1, harbored in E. coli 803, was transferred into S. meliloti 1021 by tri-parental mating. A single clone (S. meliloti 1021/pSGAT) that overexpressed at least two putative GalA transferase activities was identified from a pool of four extracts out of ~1000 pools screened (not shown). Assays indicated that S. meliloti 1021/pSGAT directed the conversion of Kdo2-[4′-32P]lipid IVA to two more slowly migrating species (i.e. relatively more hydrophilic) when analyzed by TLC. The shift in Rf values between substrate and products was larger than observed with the R. leguminosarum mannosyl- and galactosyl-transferases (15), suggestive of a more hydrophilic modification, such as a GalA residue.

Subcellular Localization and Substrate Preference of the Putative GalA Transferase Activities

Restriction fragments of the 22-kb R. leguminosarum 3841 genomic DNA insert in pSGAT were subcloned into the shuttle vector pRK404a, and the constructs were transferred by tri-parental mating from an E. coli host (HB101) into S. meliloti 1021. Unlike R. leguminosarum, S. meliloti lacks inner core LPS GalA modifications. Crude extracts of S. meliloti 1021 harboring pMKGE, a plasmid containing an ~7-kb EcoRI DNA fragment (supplemental Fig. 1), were able to reproduce the activities identified in the original screen with pSGAT (Fig. 3). The two metabolites formed were designated products I and II.

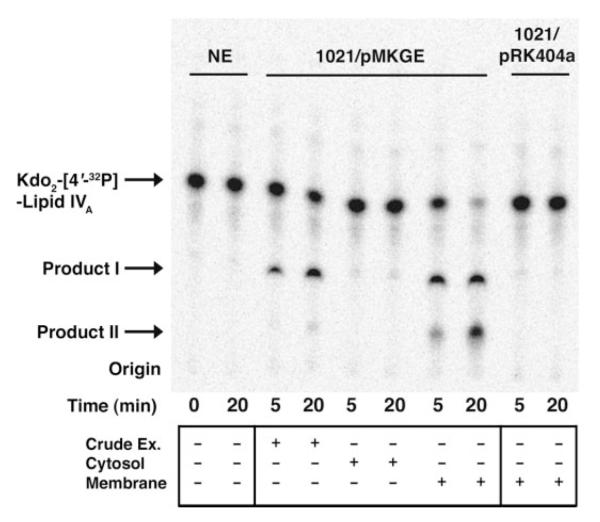

FIGURE 3. Two hydrophilic products generated from Kdo2-lipid IVA by membranes of S. meliloti harboring pMKGE.

Crude extracts of S. meliloti 1021/pMKGE were centrifuged at 100,000 × g to yield cytosolic and membrane fractions. The indicated fractions were then assayed at 0.25 mg/ml protein with 2.5 μM Kdo2-[4′-32P]lipid IVA as the acceptor under standard assay conditions. Membranes from S. meliloti cells harboring the vector pRK404a were used as the control. NE, no enzyme.

To determine the subcellular localization of these activities, the crude extract was separated into cytosol and membranes by ultracentrifugation. The activity localized to the membrane fraction (Fig. 3). There was no dependence of activity on the addition of cytosolic components (data not shown), in contrast to the behavior of the R. leguminosarum core glycosyltransferases LpcA, LpcB, and LpcC, which are membrane-bound enzymes requiring cytosolic sugar nucleotide donors (15).

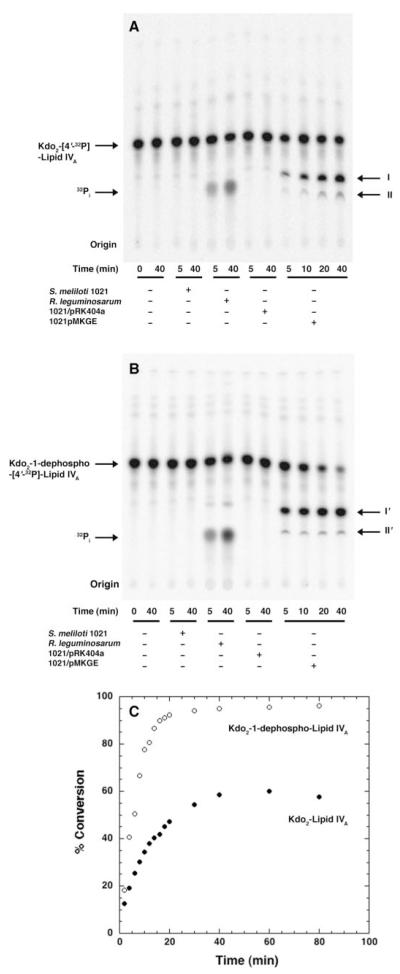

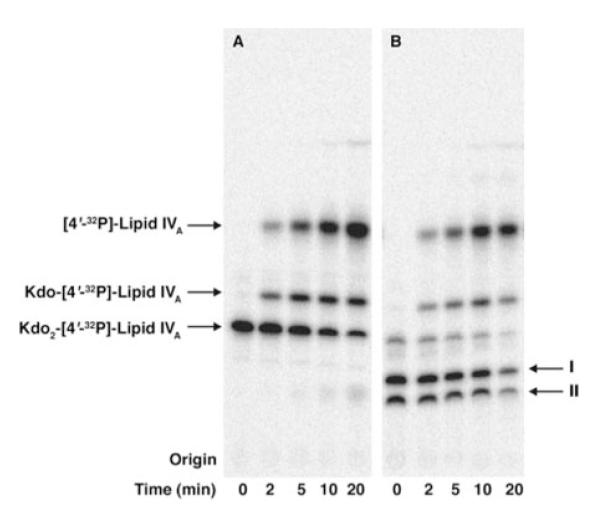

There was considerable overexpression of the putative GalA transferase activities in membranes of S. meliloti cells harboring pMKGE compared with membranes of R. leguminosarum 3841 (Fig. 4, panel A). Although the activities were time-dependent and linear for the first 10 min when assayed with Kdo2-[4′-32P]lipid IVA, they saturated at 60% conversion (Fig. 4, panel C). Because R. leguminosarum LPS is dephosphorylated, the membranes were also assayed with Kdo2-1-dephospho-[4′-32P]lipid IVA (Fig. 4, panel B). The two metabolites formed with each of the substrates, Kdo2-[4′-32P]lipid IVA and Kdo2-1-dephospho-[4′-32P]lipid IVA, were designated products I and II or products I’ and II’, respectively (Fig. 4). Whereas formation of products I, II, I’, and II’ by membranes of S. meliloti 1021/pMKGE was linear for the first 10 min under optimized conditions, Kdo2-1-dephospho-[4′-32P]lipid IVA was preferred (Fig. 4, panel C). Washed membranes of S. meliloti 1021/pMKGE exhibited an almost 75-fold higher specific activity with Kdo2-1-dephospho-[4′-32P]lipid IVA compared with wild type R. leguminosarum 3841 membranes (Table 3).

FIGURE 4. Modification of Kdo2-lipid IVA or Kdo2-1-dephospho-lipid IVA by membranes of S. meliloti harboring pMKGE.

The putative GalA transferase activities present in membranes of S. meliloti 1021/pMKGE were compared with wild type R. leguminosarum 3841, S. meliloti 1021, or S. meliloti 1021 harboring the vector pRK404a. Membranes were assayed at 0.25 mg/ml with 2.5 μM Kdo2-[4′-32P]lipid IVA (panel A) or Kdo2-1-dephospho-[4′-32P]lipid IVA (panel B). Their products were designated I, II, or I’,II’, respectively. The time course with Kdo2-[4′-32P]lipid IVA (closed circles) versus the 1-dephosphorylated analogue (open circles) is shown in panel C. The percent conversion refers to the sum of both products.

TABLE 3. RgtA-specific activity in membranes of various strains and constructs.

The specific activity of product I’ formation was measured using washed membranes at 0.25 mg/ml with 2.5 μM Kdo2-1-dephospho-[4′-32P]lipid IVA (3000–6000 cpm/nmol). Product formation after 10 min was used to calculate specific activities. Exogenous donor substrate was not included. Therefore, these specific activities are relevant only to the above assay conditions.

| Strain | Specific activity |

|---|---|

| nmol product/10 min/mg | |

| R. leguminosarum 3841 | 0.096 |

| S. meliloti 1021 | NDa |

| S. meliloti 1021/pRK404a | ND |

| S. meliloti 1021/pMKGE | 7.219 |

ND indicates no detectable GalA transferase activity is present in membranes.

Addition of Putative GalA Units to the Outer Kdo of the Acceptor Substrate

Products I and II were subjected to hydrolysis under mild acid conditions (12.5 mM sodium acetate, pH 4.5, and 1% SDS at 100 °C). This procedure selectively cleaves the glycosidic linkages of Kdo. Progress of cleavage was monitored by TLC analysis over 20 min. As shown in Fig. 5, both the unmodified (panel A) and modified (panel B) Kdo2-[4′-32P]lipid IVA yielded Kdo-[4′-32P]lipid IVA and [4′-32P]lipid IVA as the predominant hydrolysis products. No modified Kdo-[4′-32P]lipid IVA or [4′-32P]lipid IVA derivatives were observed. This finding demonstrates that the hydrophilic adducts in products I and II are linked mainly to the outer Kdo residue. Taken together with the published structure of the R. leguminosarum LPS core (Fig. 1) (11, 14), which contains two GalA residues on the outer Kdo, our analysis suggests that S. meliloti 1021/pMKGE expresses the corresponding GalA transferases.

FIGURE 5. Time course of mild acid hydrolysis of Kdo2-[4′-32P]lipid IVA versus products I and II.

Panel A, the Kdo2-[4′-32P]lipid IVA control. Panel B, products I and II. The hydrolysis was carried out at 100 °C in 12.5 mM sodium acetate buffer, pH 4.5, in the presence of SDS (40). The two Kdo glycosidic linkages are similarly susceptible to cleavage under these conditions, allowing discrimination between modification of the outer versus the inner Kdo residues or lipid A.

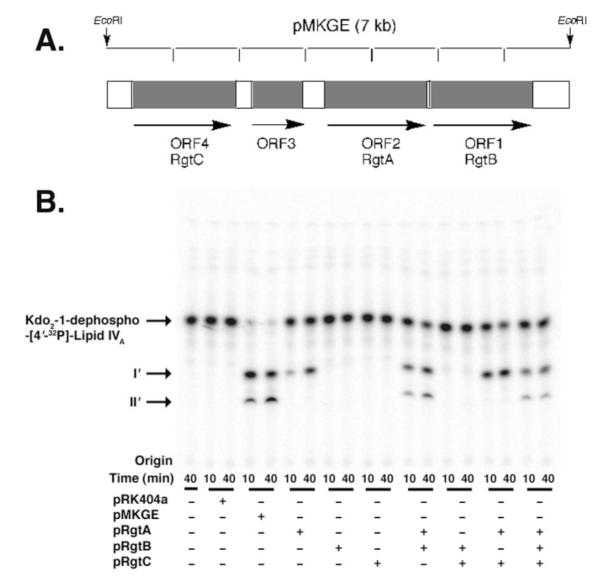

Identification of the Candidate GalA Transferases RgtA, RgtB, and RgtC

Sequence analysis of the DNA insert in pMKGE, using the programs DNA Strider and ORF Finder, revealed the presence of four putative ORFs (Fig. 6, panel A). The ORFs were analyzed for homology to proteins of known function using the COGNITOR program (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov) (45, 46). The results of this analysis are shown in Table 4. The predicted proteins encoded by orf1, orf2, and orf4 of pMKGE, which show distant homology to the ArnT protein in COG1807, are of particular interest. In E. coli and S. typhimurium, this glycosyltransferase is involved in modifying lipid A with a 4-amino-4-deoxy-L-arabinose (L-Ara4N) residue, using undecaprenyl phosphate-L-Ara4N as the donor substrate (35, 36).

FIGURE 6. Functions of enzymes encoded by genes in the rgt region of the R. leguminosarum chromosome.

Panel A, the 7-kb DNA insert in pMKGE was sequenced and analyzed using the NCBI ORF finder program (42). The sequence shows four putative open reading frames that are transcribed in the indicated directions. The possible functions of the ORFs were evaluated using COGNITOR (46) and PSI-BLAST (64). The results are summarized in Table 3. Panel B, reactions were performed with Kdo2-1-dephospho-[4′-32P]lipid IVA as substrate. Washed membranes of S. meliloti 1021 cells harboring the indicated plasmids were added at 0.25 mg/ml. The mixtures were incubated at 30 °C for the indicated times, and 4-μl portions were spotted onto a silica TLC plate to stop the reactions. The membranes of the constructs were assayed individually or in different combinations to determine the order of RgtA and RgtB function.

TABLE 4. Predicted functions of proteins encoded by genes on the 7-kb EcoRI fragment of pMKGE.

Putative functions of the ORFs were identified using the PSI-BLAST algorithm and the predicted protein sequence of each R. leguminosarum gene as query. The sequence was matched against the nonredundant data base of all bacterial proteins, but the E values listed were for homology to proteins with known biochemistry (36). RgA, RgtB, and RgtC were similar to proteins in COG1807 (4-amino-4-deoxy-l-arabinose transferase, ArnT, and related glycosyltransferases of the PMT family) (36) but only showed limited homology to the E. coli ArnT protein upon three iterations of PSI BLAST comparison. Homology is given as the number of identities (%)/number of positives (%)/number of residues in the related segment (including gaps), when compared with the E. coli proteins. Orf3 shows homology to COG0463 (putative glycosyltransferases, WcaA, and related glycosyltransferases involved in cell wall biogenesis) and showed homology to the E. coli PmrF(ArnC) (60).

| Predicted R. leguminosarum protein (amino acids) |

GenBank™ accession no. | COG | Related E. coli K-12 protein: no. identities/no. positives/no. residues (gaps) |

E value (no. PSI BLAST iterations) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Orf1/RgtB (494) | DQ298017 | 1807 | ArnT, 47(12%)/102(27%)/377(28) | 6 × 10-34(3) |

| Orf2/RgtA (499) | DQ298016 | 1807 | ArnT, 49(13%)/105(28%)/370(26) | 1 × 10-41(3) |

| Orf3 (294) | 0463 | PmrF, 96(32%)/145(49%)/293(20) | 2 × 10-29(1) | |

| Orf4/RgtC (497) | DQ298018 | 1807 | ArnT, 47(12%)/108(28%)/373(31) | 2 × 10-39(3) |

Orf1, Orf2, and Orf4 are each predicted to be ~500 amino acid residues long (Table 4), with 8–10 membrane-spanning regions. Their predicted topology bears similarity to E. coli ArnT (534 amino acids and 12 transmembrane regions). We propose that Orf2, Orf1, and Orf4 be renamed RgtA, RgtB, and RgtC (Rhizobium galA transferase), respectively, based on this homology and their likely function as the structural genes for the R. leguminosarum LPS core GalA transferases (see below).

Heterologous Expression and Characterization of Enzyme Activities

The genes rgtA, rgtB, and rgtC were cloned into the expression vector pET23a (supplemental Fig. 1) and expressed in E. coli NovaBlue (DE3). Membranes of NovaBlue (DE3) expressing pRgtA, pRgtB, or pRgtC were unable to generate products I, II, I’, or II’ (data not shown). Based on the similarity of the Rgt proteins to ArnT, which uses a lipid-linked sugar donor, we postulated that a lipid-linked GalA donor might also be required for the Rgt enzymes. Because E. coli lacks LPS GalA modifications (6), we surmised that the lack of heterologous Rgt activity in NovaBlue (DE3) might reflect the absence of the appropriate GalA donor. However, S. meliloti is phylogenetically closer to R. leguminosarum and contains GalA units in its exopolysaccharide and capsular polysaccharide (47). We therefore hypothesized that S. meliloti might synthesize a similar lipid-linked GalA donor.

The rgt genes were cloned into the shuttle vector pRK404a to generate pRK-RgtA, pRK-RgtB, and pRK-RgtC and then transferred into S. meliloti 1021. Assays of these constructs revealed that only membranes of S. meliloti 1021/pRK-RgtA were able to shift Kdo2-1-dephospho-[4′-32P]lipid IVA to product I’ (Fig. 6, panel B). Further addition of S. meliloti 1021/pRK-RgtA membranes and/or longer incubation periods did not yield product II’, indicating that RgtA is monofunctional. The membranes of S. meliloti 1021 cells expressing the individual Rgt proteins were then assayed in different combinations to determine the preferred order of action of the Rgt proteins. Only pRK-RgtA and pRK-RgtB membranes together reconstituted the two outer Kdo modifying activities seen in the original clone pMKGE (Fig. 6, panel B). Because pRK-RgtB membranes alone exhibited no activity with Kdo2-1-dephospho-[4′-32P]lipid IVA, but did show activity in the presence of pRK-RgtA membranes, the product of RgtA appears to be the preferred substrate for RgtB, indicating that the formation of product II’ is dependent upon the prior formation of product I’.

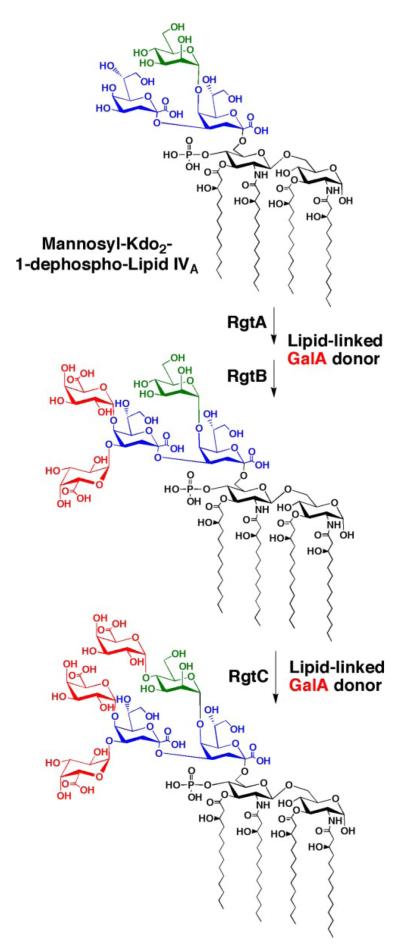

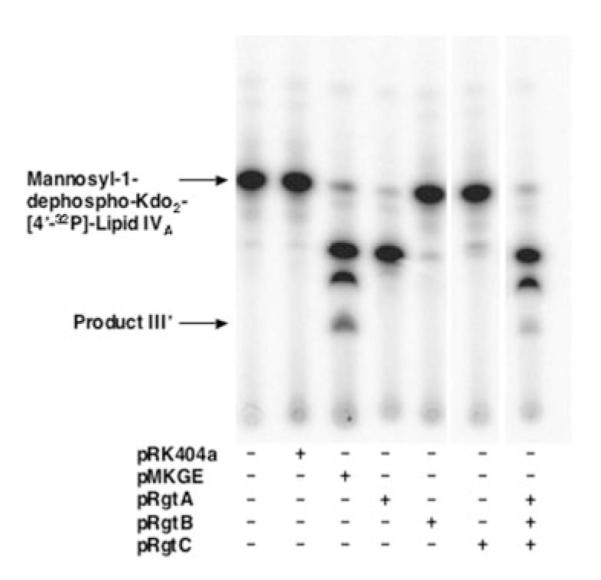

RgtC was then proposed to function as the GalA transferase for the core mannose unit. New assays were performed with mannosyl-Kdo2-1-dephospho-[4′-32P]lipid IVA and membranes of pMKGE expressed in S. meliloti 1021. A third hydrophilic compound (product III’) was obtained at longer incubation times (Fig. 7). The three activities could also be reconstituted by combining membranes from cells expressing RgtA, RgtB, and RgtC (Fig. 7). Because RgtC has no detectable activity with mannosyl-Kdo2-1-dephospho-[4′-32P]lipid IVA by itself, we suggest that RgtC activity is dependent upon the prior activities of RgtA and RgtB (Fig. 12).

FIGURE 7. A third GalA transferase activity catalyzed by RgtC.

S. meliloti 1021/pMKGE membranes were assayed with mannosyl-Kdo2-1-dephospho-[4′-32P]lipid IVA under standard assay conditions without carrier substrate at 0.25 mg/ml membrane protein. With this substrate, a third product is observed at later times, designated product III’. The three products can also be generated by the sequential action of RgtA, RgtB, and RgtC expressed individually in S. meliloti 1021, as shown in the far right lane.

FIGURE 12. Order of possible enzymatic reactions for the attachment of GalA moieties to the R. leguminosarum LPS core.

The enzymes responsible for the 1-dephosphorylation of lipid A and for the incorporation of the mannose have been reported elsewhere (15, 22). RgtA and RgtB are proposed to add the two GalA units to the outer Kdo. The locations and stereochemistry of the attachment sites as α-(1–4) and α-(1–5) are proposed based on the structures of the related oligosaccharides isolated from cells (17, 65). Our data do not establish which linkage is formed first by RgtA and whether or not the same linkages are generated in our in vitro system as occur in vivo (17). Larger quantities of each product will have to be synthesized to resolve these structural ambiguities. RgtC presumably attaches a third GalA moiety to the core mannose unit in α-(1–4) linkage (17, 65), given the substrate requirement for detecting RgtC activity as shown here.

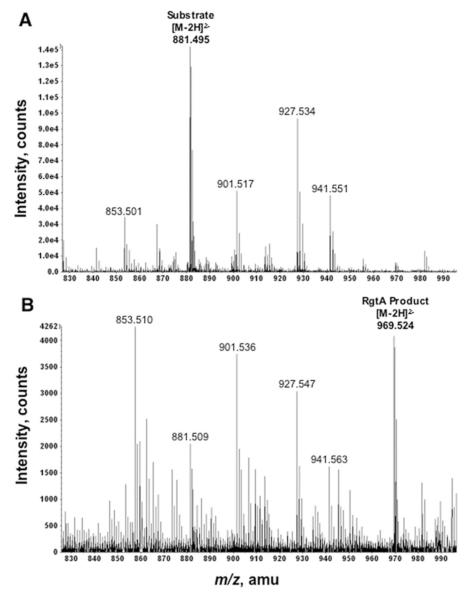

In Vitro Synthesis and Mass Spectrometry of Product I’

To verify the presence of GalA, product I’ was prepared from unlabeled Kdo2-1-dephospho-lipid IVA using membranes of S. meliloti 1021/pMKGE (see “Experimental Procedures”). The reaction was optimized to favor incorporation of only one GalA unit. The substrate and product were then purified from the reaction mixture by DEAE-cellulose column chromatography. The substrate eluted with 120–240 mM ammonium acetate as the aqueous component. The product eluted at higher salt concentrations (240–480 mM). The expected molecular formulae, exact masses, and m/z values for the doubly charged ions derived from substrate or product I’ are shown in Table 5. Negative ion ESI/MS analysis confirmed the presence of the expected [M — 2H]2- substrate peak at m/z 881.495 (theoretical m/z 881.495) in the 240 mM fraction and of the product I’ peak at m/z 969.524 (theoretical m/z 969.511) in the 480 mM fraction (Fig. 8, panels A and B, respectively), consistent with the presence of one hexuronic acid (HexA) moiety in product I’.

TABLE 5. Summary of ESI/MS data of Kdo2-1-dephospho-lipid IVA versus product I’.

Product I’ is proposed to contain 1 GalA unit attached to the outer Kdo residue.

| Kdo2-1-dephospho-lipid IVA | Product I’ | |

|---|---|---|

| Molecular formula | C84H153N2O34P | C90H161N2O40P |

| Expected exact mass | 1765.004 | 1941.036 |

| Predicted m/z [M — 2H]2- | 881.495 | 969.511 |

| Observed m/z [M — 2H]2- | 881.495 | 969.524 |

FIGURE 8. Negative ion ESI/MS of Kdo2-1-dephospho-lipid IVA and product I’.

Product I’ was synthesized in vitro from Kdo2-1-dephospho-lipid IVA (see “Experimental Procedures”), and both the remaining substrate and product I’ were purified by DEAE-cellulose chromatography. The spectra in the m/z range 830–990 atomic mass units (amu) of the 240 mM fraction (panel A) and the 480 mM fraction (panel B) are shown. Both substrate (panel A) and product I’ (panel B) yield mainly [M — 2H]2- ions with the expected masses and isotope distributions for Kdo2-1-dephospho-lipid IVA or GalA-Kdo2-1-dephospho-lipid IVA, respectively. Additional details are listed in Table 5. Unassigned peaks are because of lipid impurities carried over from the membranes that were used as the enzyme source.

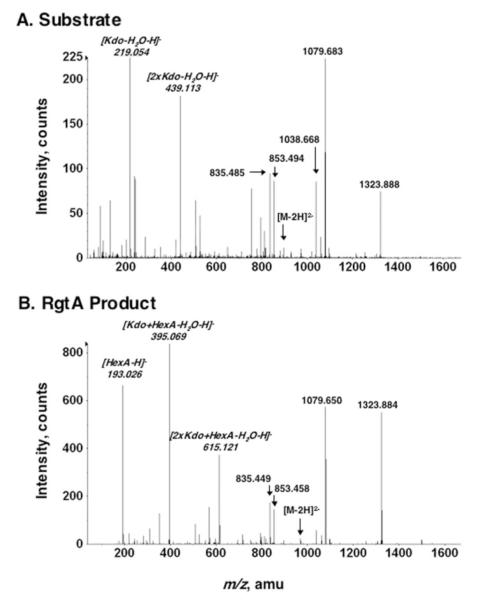

The identity of the key peaks was verified by collision-induced dissociation tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS) (Fig. 9). Among the fragments derived from both m/z 881.5 and 969.5 are ions corresponding to 1-dephospholipid IVA (m/z 1323.84) and its 3- and 3′-O-deacylated versions (m/z 1079.6 and 853.5). MS/MS of the peak at m/z 969.5 exhibited a distinct prominent peak at m/z 193.026, consistent with a single HexA unit, not present in the MS/MS of the substrate ion at m/z 881.5 (Fig. 9, panel B versus A). Furthermore, those peaks corresponding to one (219.054) or two (439.113) Kdo residues in the MS/MS of the substrate are replaced with fragments indicative of a HexA unit linked to one (395.069) or two Kdo residues (615.121) in product I’ (Fig. 9, panel A versus B). Similar results were obtained for product I’ prepared with membranes of S. meliloti 1021/pRK-RgtA (not shown). The MS/MS data therefore corroborate the mild acid hydrolysis experiment (Fig. 5) and confirm the attachment of a HexA unit to the outer Kdo moiety of product I’.

FIGURE 9. MS/MS analysis of Kdo2-1-dephospho-lipid IVA and product I’.

Panel A, MS/MS of the [M — 2H]2- substrate ion at m/z 881.5 (see Fig. 8A). Panel B, MS/MS of the [M — 2H]2- product I’ ion at m/z 969.5 (see Fig. 8B). Key peaks unique to the substrate and product are italicized. The mass shifts of the Kdo-containing ions are consistent with the addition of 1 HexA unit to the outer Kdo residue. amu, atomic mass units.

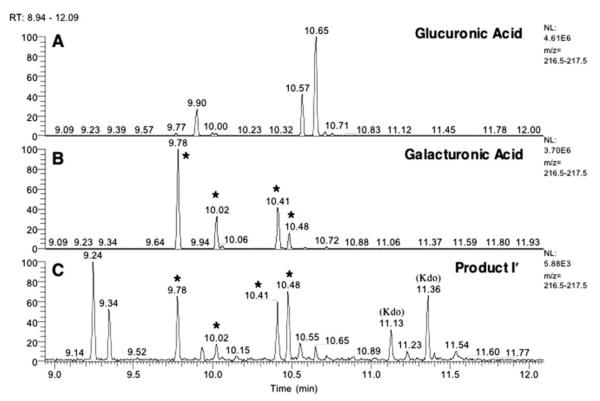

The identity of the HexA moiety in product I’ was determined by GC/MS analysis. Assignments were based upon comparison of retention times and electron impact ionization mass spectra with those of standards (GlcA, GalA, GlcN, Kdo, Glc, and Gal). The main peaks observed with the substrate corresponded to volatile derivatives of the Kdo and myristate residues (data not shown). The selective ion chromatogram of m/z 217 (a fragment observed in electron impact mass spectra of sialylated hexoses), derived from product I’, showed the presence of peaks that matched the retention times of the GalA standard (Fig. 10, asterisks), in addition to the peaks derived from the Kdo and myristate units.

FIGURE 10. Identification of GalA in product I’ by GC/MS analysis.

Trimethylsilyl ester derivatives of methyl glycosides, obtained by methanolic HCl hydrolysis of DEAE-cellulose-purified fractions (from Fig. 8), were separated by gas-liquid chromatography. Peaks were identified by the comparison of their retention times with those of standards prepared in parallel (see asterisks). The profile (selective ion monitoring at m/z 217) for product I’ is compared with that of the GalA and GlcA standards.

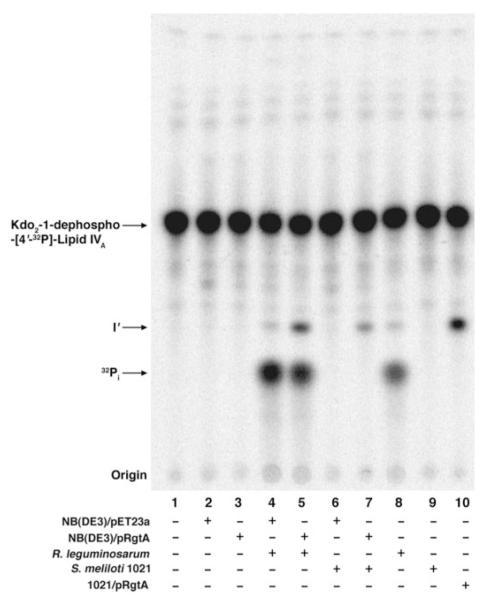

Activity of pRgtA in E. coli NovaBlue (DE3) Requires a Rhizobiaceae Membrane Component

To verify that the lack of GalA transferase activity in membranes of E. coli NovaBlue (DE3)/pRgtA was not because of the failure of heterologous protein expression, we added membranes of S. meliloti 1021 or R. leguminosarum 3841 to the assay system. The addition of S. meliloti or R. leguminosarum membranes to E. coli NovaBlue (DE3)/pRgtA membranes greatly stimulated product I’ formation (Fig. 11). This synergistic effect is especially striking in the case of S. meliloti membranes (Fig. 11, lanes 3, 6, and 7). These results support the idea that RgtA, in analogy to E. coli ArnT, utilizes a lipid-linked sugar as its donor substrate (35). The proposed lipid-linked GalA donor would only be present in the membranes of the appropriate Rhizobiaceae. This hypothesis was confirmed in the accompanying article (70) with lipids purified from S. meliloti 1021 or R. leguminosarum 3841.

FIGURE 11. A Rhizobiaceae membrane component is required for RgtA activity in E. coli.

Membranes of the indicated constructs in E. coli NovaBlue (DE3) were assayed at 0.25 mg/ml. Additional membranes from S. meliloti 1021 or R. leguminosarum 3841 were added at 0.25 mg/ml, as indicated. Product I’ formation upon reconstitution was also compared with the control membranes of S. meliloti 1021/pRgtA.

DISCUSSION

Bacterial surface polysaccharides play important roles in the establishment of symbiotic or infectious interactions of Gram-negative bacteria with their hosts. Consequently, polysaccharide-deficient bacteria often show reduced infectivity (48-50). GalA is commonly found as part of the exopolysaccharide and capsular polysaccharide of symbiotic Gram-negative bacteria (51, 52). GalA is also a component of the lipid A and LPS core regions of many organisms. For instance, R. leguminosarum replaces the lipid A 4′-phosphate with a GalA residue and modifies its LPS inner core with three GalA moieties (Fig. 1). Mesorhizobium huakuii, another nitrogen-fixing plant endosymbiont, replaces its lipid A1-phosphate group with a GalA residue, whereas A. pyrophilus, a hyperthermophile, replaces both the lipid A1 and 4′-phosphates with GalA (11, 17, 25-27, 53). The functions of the GalA units present in the LPS of these bacteria are unknown.

By combining an expression cloning strategy with bioinformatic analyses, we have now identified a single fragment of R. leguminosarum 3841 genomic DNA that directs the expression of three GalA transferases. Two of these membrane-bound enzymes add two GalA moieties to the outer Kdo residue of the acceptor, Kdo2-[4′-32P]lipid IVA (Fig. 3), as determined by mild acid hydrolysis (Fig. 5). Unlike the membrane-bound R. leguminosarum core glycosyltransferases LpcA, LpcB, and LpcC, which require a cytosolic sugar nucleotide donor (15), the proposed GalA transferases require only membrane components (Fig. 3). This rules out the possibility of a sugar nucleotide as the direct GalA donor, which is corroborated by the observation that the activity is not enhanced by addition of exogenous UDP-GalA (data not shown).

Sequence analysis of our 7-kb fragment predicts four ORFs, three of which are distantly related to COG 1807 (orf1, orf2, and orf4) (Fig. 6). The best characterized member of this family is the ArnT protein (35, 36), an enzyme that transfers l-Ara4N to lipid A in polymyxin-resistant strains of E. coli and S. typhimurium. E. coli ArnT is 550 amino acids long and is predicted to have 12 membrane-spanning regions. The identified ORFs, renamed RgtA, RgtB, and RgtC, are 499, 494, and 497 amino acids long, respectively (Table 4). Their hydropathy profiles resemble that of ArnT, with 8–10 predicted membrane-spanning segments in the N-terminal portion of each protein, where the most homology resides. The N terminus of E. coli ArnT also has numerous homologues in other bacterial and eukaryotic systems, including the protein mannosyltransferases of yeast and animal cells (36, 54, 55), which utilize dolichol phosphate-mannose as their sugar donor. The N-terminal portion of these distantly related proteins may contain the region for binding of their polyisoprenyl phosphate-sugar substrates, leaving the less conserved C-terminal region to play a more specific role in acceptor substrate recognition (35, 36). Based on this analysis, we hypothesized that the three related ORFs encoded by the 7-kb fragment of pMKGE might be GalA transferases that utilize a polyisoprenyl phosphate-GalA substrate. This view was also in accord with a single report by Russomando and Dankert (56) of a lipid-linked GalA derivative, generated from UDP-[14C]glucuronic acid by membranes of R. leguminosarum biovar trifolii. However, the complete covalent structure and biological function of this material were not determined.

RgtA, RgtB, and RgtC were cloned into the shuttle vector pRK404a and transferred into S. meliloti 1021. Only RgtA and RgtB directed the overexpression of the two Kdo2-1-dephospho-[4′-32P]lipid IVA modifying activities seen in the original clone. RgtA precedes and is a prerequisite for the subsequent activity of RgtB (Fig. 6). Because the GalA modifications of the outer Kdo can be ascribed to RgtA and RgtB, RgtC was proposed to function as the GalA transferase for the core mannose unit. Assays with mannosyl-Kdo2-1-dephospho-[4′-32P]lipid IVA indeed verified the formation of a third hydrophilic compound that was RgtC-dependent (Fig. 7). We have also established a preferred order of action of the Rgt proteins (see Figs. 6, 7, and 12).

The lack of RgtA activity upon expression in E. coli, in contrast to the presence of activity upon expression in S. meliloti 1021, suggests a Rhizobiaceae-specific, membrane-bound co-substrate (Fig. 8). We have isolated and characterized the structure of this material as a dodecaprenyl (C60) phosphate-linked GalA, as described in the accompanying article (70).

Orf3 (Fig. 6) is predicted to be a member of COG 0463, the representative members of which include bacterial glycosyltransferases involved in cell wall biogenesis. Of particular interest is the homology of Orf3 to the E. coli and S. typhimurium PmrF (ArnC) proteins. This gene product was first identified as part of the PmrA-PmrB regulated operon in S. typhimurium that is required for the maintenance of resistance to polymyxin and the addition of L-Ara4N to lipid A (57). Based on its homology to yeast dolichyl-phosphate mannose synthase, E. coli PmrF was postulated to be involved in the synthesis of the lipid-linked L-Ara4N donor (58). In fact, PmrF (ArnC) catalyzes the selective transfer of L-Ara-formyl-4N from UDP-N-formyl-4-amino-4-deoxy-L-arabinose to undecaprenyl phosphate, generating a lipid precursor that is immediately deformylated by ArnD (59, 60). The final lipid donor, undecaprenyl phosphate-α-L-Ara4N, isolated in milligram quantities from the lipid fraction of polymyxin-resistant mutants, is well characterized (35). It is the donor substrate for ArnT (35, 36). If RgtA, RgtB, and RgtC do in fact use a polyisoprene phosphate-GalA substrate, then Orf3 might function to generate this material from UDP-GalA (or a closely related sugar nucleotide) and the R. leguminosarum equivalent of undecaprenyl-phosphate (70).

The kinetic preference for the 1-dephosphorylated substrate (Fig. 4) suggests that the 1-phosphatase, LpxE, might function before RgtA, RgtB, and RgtC. It has been demonstrated that LpxE is an inner membrane enzyme, which is dependent upon the inner membrane LPS flip-pase, MsbA, for its activity (61, 62). Thus, the RgtA, RgtB, and RgtC active sites also likely face the periplasm, consistent with a lipid-linked GalA donor substrate.

A tBLASTn analysis (63) of the R. leguminosarum 3841 genome using RgtA as the probe reveals the presence of a fourth related protein at a distant chromosomal site. We suggest that this might be the lipid A 4′-GalA transferase, tentatively designated RgtD. We suggest that RgtD uses the same lipid-linked GalA donor as RgtA, RgtB, and RgtC on the outer surface of the inner membrane. Further characterization of these GalA transferases and the construction of selective knock-out mutants should provide a clearer picture of the biological relevance of GalA modifications in R. leguminosarum LPS.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The mass spectrometry facility in the Department of Biochemistry, Duke University Medical Center, was supported by the LIPID MAPS Large Scale Collaborative Grant GM-069338 from the National Institutes of Health. We thank Dr. J. A. Downie (John Innes Institute, Norwich, UK) and Dr. P. Poole (University of Reading) for providing the R. leguminosarum 3841 genomic DNA cosmid library. We also thank Dr. D. Borthakur (University of Hawaii) for the pRK404a plasmid shuttle vector. We thank Dr. C. M. Reynolds, Dr. M. B. Hinckley, and Dr. D. A. Six for their help with the preparation of this manuscript.

Footnotes

This work was supported in part by National Institutes of Health Grant R37-GM-51796 (to C. R. H. R.). The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Fig. 1.

- LPS

- lipopolysaccharide

- ESI

- electrospray ionization

- GalA

- galacturonic acid

- GC/MS

- gas-liquid chromatography mass spectrometry

- HexA

- hexuronic acid

- Kdo

- 3-deoxy-D-manno-octulosonic acid

- MS

- mass spectrometry

- MS/MS

- tandem mass spectrometry

- MES

- 4-morpholineethane sulfonic acid

- ORF

- open reading frame

- Str

- streptomycin

- Nal

- nalidixic acid

- Tet

- tetracycline

- L-Ara4N

- 4-amino-4-deoxy-L-arabinose

REFERENCES

- 1.Fahy E, Subramaniam S, Brown HA, Glass CK, Merrill AH, Jr., Murphy RC, Raetz CRH, Russell DW, Seyama Y, Shaw W, Shimizu T, Spener F, van Meer G, VanNieuwenhze MS, White SH, Witztum JL, Dennis EA. J. Lipid Res. 2005;46:839–862. doi: 10.1194/jlr.E400004-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Raetz CRH. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 1990;59:129–170. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.59.070190.001021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Raetz CRH. In: Escherichia coli and Salmonella: Cellular and Molecular Biology. 2nd Neidhardt FC, editor. American Society for Microbiology; Washington, DC: 1996. pp. 498–503. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reeves PR, Hobbs M, Valvano MA, Skurnik M, Whitfield C, Coplin D, Kido N, Klena J, Maskell D, Raetz CRH, Rick PD. Trends Microbiol. 1996;4:495–503. doi: 10.1016/s0966-842x(97)82912-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brade H, Opal SM, Vogel SN, Morrison DC. Endotoxin in Health and Disease. Marcel Dekker, Inc.; New York: 1999. p. 950. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Raetz CRH, Whitfield C. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2002;71:635–700. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.71.110601.135414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Roantree RJ. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 1967;21:443–466. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.21.100167.002303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nikaido H. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2003;67:593–656. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.67.4.593-656.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bhat UR, Forsberg LS, Carlson RW. J. Biol. Chem. 1994;269:14402–14410. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brozek KA, Kadrmas JL, Raetz CRH. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:32112–32118. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Forsberg LS, Carlson RW. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:2747–2757. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.5.2747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Que NL, Lin S, Cotter RJ, Raetz CRH. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:28006–28016. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M004008200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Basu SS, Karbarz MJ, Raetz CRH. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:28959–28971. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M204525200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Carlson RW, Reuhs B, Chen TB, Bhat UR, Noel KD. J. Biol. Chem. 1995;270:11783–11788. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.20.11783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kadrmas JL, Allaway D, Studholme RE, Sullivan JT, Ronson CW, Poole PS, Raetz CRH. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:26432–26440. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.41.26432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kadrmas JL, Brozek KA, Raetz CRH. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:32119–32125. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bhat UR, Krishnaiah BS, Carlson RW. Carbohydr. Res. 1991;220:219–227. doi: 10.1016/0008-6215(91)80020-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Que NLS, Ribeiro AA, Raetz CRH. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:28017–28027. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M004009200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Basu SS, White KA, Que NL, Raetz CRH. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:11150–11158. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.16.11150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Basu SS, York JD, Raetz CRH. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:11139–11149. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.16.11139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Que-Gewirth NLS, Lin S, Cotter RJ, Raetz CRH. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:12109–12119. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M300378200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Karbarz MJ, Kalb SR, Cotter RJ, Raetz CRH. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:39269–39279. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M305830200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Niedziela T, Lukasiewicz J, Jachymek W, Dzieciatkowska M, Lugowski C, Kenne L. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:11653–11663. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111885200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Frirdich E, Bouwman C, Vinogradov E, Whitfield C. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:27604–27612. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M504987200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Plötz BM, Lindner B, Stetter KO, Holst O. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:11222–11228. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.15.11222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Choma A, Sowinski P. Eur. J. Biochem. 2004;271:1310–1322. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.2004.04038.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Carlson RW, Forsberg LS, Price NP, Bhat UR, Kelly TM, Raetz CRH. Prog. Clin. Biol. Res. 1995;392:25–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Regue M, Hita B, Pique N, Izquierdo L, Merino S, Fresno S, Benedi VJ, Tomas JM. Infect. Immun. 2004;72:54–61. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.1.54-61.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ridley BL, O’Neill MA, Mohnen D. Phytochemistry. 2001;57:929–967. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9422(01)00113-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mohnen D, Hahn MG. Semin. Cell Biol. 1993;4:93–102. doi: 10.1006/scel.1993.1012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Aderem A, Ulevitch RJ. Nature. 2000;406:782–787. doi: 10.1038/35021228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cohn J, Sessa G, Martin GB. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 2001;13:55–62. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(00)00182-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nurnberger T, Scheel D. Trends Plant Sci. 2001;6:372–379. doi: 10.1016/s1360-1385(01)02019-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ronson CW, Astwood PM, Downie JA. J. Bacteriol. 1984;160:903–909. doi: 10.1128/jb.160.3.903-909.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Trent MS, Ribeiro AA, Doerrler WT, Lin S, Cotter RJ, Raetz CRH. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:43132–43144. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M106962200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Trent MS, Ribeiro AA, Lin S, Cotter RJ, Raetz CRH. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:43122–43131. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M106961200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Smith PK, Krohn RI, Hermanson GT, Mallia AK, Gartner FH, Provenzano MD, Fujimoto EK, Goeke NM, Olson BJ, Klenk DC. Anal. Biochem. 1985;150:76–85. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(85)90442-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Garrett TA, Kadrmas JL, Raetz CRH. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:21855–21864. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.35.21855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Reynolds CM, Kalb SR, Cotter RJ, Raetz CRH. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:21202–21211. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M500964200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kanipes MI, Ribeiro AA, Lin S, Cotter RJ, Raetz CRH. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:16356–16364. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M301255200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Brozek KA, Hosaka K, Robertson AD, Raetz CRH. J. Biol. Chem. 1989;264:6956–6966. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wheeler DL, Church DM, Federhen S, Lash AE, Madden TL, Pontius JU, Schuler GD, Schriml LM, Sequeira E, Tatusova TA, Wagner L. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:28–33. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kadrmas JL, Raetz CRH. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:2799–2807. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.5.2799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bligh EG, Dyer WJ. Can. J. Biochem. Physiol. 1959;37:911–917. doi: 10.1139/o59-099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tatusov RL, Natale DA, Garkavtsev IV, Tatusova TA, Shankavaram UT, Rao BS, Kiryutin B, Galperin MY, Fedorova ND, Koonin EV. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29:22–28. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.1.22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tatusov RL, Galperin MY, Natale DA, Koonin EV. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:33–36. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.1.33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Keating DH, Willits MG, Long SR. J. Bacteriol. 2002;184:6681–6689. doi: 10.1128/JB.184.23.6681-6689.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Niehaus K, Becker A. Subcell. Biochem. 1998;29:73–116. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4899-1707-2_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Campbell GR, Reuhs BL, Walker GC. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. u. S. A. 2002;99:3938–3943. doi: 10.1073/pnas.062425699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Laus MC, Logman TJ, Van Brussel AA, Carlson RW, Azadi P, Gao MY, Kijne JW. J. Bacteriol. 2004;186:6617–6625. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.19.6617-6625.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Djordjevic SP, Chen H, Batley M, Redmond JW, Rolfe BG. J. Bacteriol. 1987;169:53–60. doi: 10.1128/jb.169.1.53-60.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fraysse N, Couderc F, Poinsot V. Eur. J. Biochem. 2003;270:1365–1380. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1033.2003.03492.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Severn WB, Kelly RF, Richards JC, Whitfield C. J. Bacteriol. 1996;178:1731–1741. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.6.1731-1741.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Orlean P, Albright C, Robbins PW. J. Biol. Chem. 1988;263:17499–17507. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Imbach T, Schenk B, Schollen E, Burda P, Stutz A, Grunewald S, Bailie NM, King MD, Jaeken J, Matthijs G, Berger EG, Aebi M, Hennet T. J. Clin. Investig. 2000;105:233–239. doi: 10.1172/JCI8691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Russomando G, Dankert MA. An. Assoe. Qufm. Argent. 1992;80:175–186. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gunn JS, Lim KB, Krueger J, Kim K, Guo L, Hackett M, Miller SI. Mol. Microbiol. 1998;27:1171–1182. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00757.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zhou Z, Lin S, Cotter RJ, Raetz CRH. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:18503–18514. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.26.18503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Breazeale SD, Ribeiro AA, Raetz CRH. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;279:24731–24739. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M304043200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Breazeale SD, Ribeiro AA, McClerren AL, Raetz CRH. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:14154–14167. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M414265200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Tran AX, Karbarz MJ, Wang X, Raetz CRH, McGrath SC, Cotter RJ, Trent MS. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:55780–55791. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M406480200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wang X, Karbarz MJ, McGrath SC, Cotter RJ, Raetz CRH. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:49470–49478. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M409078200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Altschul SF, Gish W, Miller W, Myers EW, Lipman DJ. J. Mol. Biol. 1990;215:403–410. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Altschul SF, Madden TL, Schaffer AA, Zhang J, Zhang Z, Miller W, Lipman DJ. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:3389–3402. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Carlson RW, Bhat UR, Reuhs B. In: Plant Biotechnology and Development. Gresshoff PM, editor. CRC Press; Boca Raton, FL: 1992. pp. 33–44. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Johnston AW, Beringer JE. J. Gen. Microbiol. 1975;87:343–350. doi: 10.1099/00221287-87-2-343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Finan TM, Kunkel B, De Vos GF, Signer ER. J. Bacteriol. 1986;167:66–72. doi: 10.1128/jb.167.1.66-72.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Friedman AM, Long SR, Brown SE, Buikema WJ, Ausubel FM. Gene (Amst.) 1982;18:289–296. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(82)90167-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ditta G, Stanfield S, Corbin D, Helinski DR. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. u. S. A. 1980;77:7347–7351. doi: 10.1073/pnas.77.12.7347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kanjilal-Kolar S, Raetz CRH. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:12879–12887. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M513865200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.