Abstract

Background

The pain and disability of hip and knee osteoarthritis can be improved by exercise, but the best method of encouraging this is not known.

Aim

To develop an evidence-based booklet for patients with hip or knee osteoarthritis, offering information and advice on maintaining activity.

Design of study

Systematic review of reviews and guidelines, then focus groups.

Setting

Four general practices in North East Wales.

Method

Evidence-based messages were developed from a systematic review, synthesised into patient-centred messages, and then incorporated into a narrative. A draft booklet was examined by three focus groups to improve the phrasing of its messages and discuss its usefulness. The final draft was examined in a fourth focus group.

Results

Six evidence-based guidelines and 54 systematic reviews were identified. The focus groups found the draft booklet to be informative and easy to read. They reported a lack of clarity about the cause of osteoarthritis and were surprised that the pain could improve. The value of exercise and weight loss beliefs was accepted and reinforced, but there was a perceived contradiction about heavy physical work being causative, while moderate exercise was beneficial. There was a fear of dependency on analgesia and misinterpretation of the message on hyaluranon injections. The information on joint replacement empowered patients to discuss referral with their GP. The text was revised to accommodate these issues.

Conclusion

The booklet was readable, credible, and useful to end-users. A randomised controlled trial is planned, to test whether the booklet influences beliefs about osteoarthritis and exercise.

Keywords: focus groups; osteoarthritis, hip; osteoarthritis, knee; patient education handout; primary health care; systematic review

INTRODUCTION

Systematic reviews have highlighted the effectiveness of exercise in reducing pain and disability in hip and knee osteoarthritis,1–3 and recent guidelines have emphasised the central role of exercise in the management of osteoarthritis.4,5 Both aerobic walking and muscle-strengthening exercise have been shown to be effective; however the optimal type, dose, and setting for such physical activity is uncertain.3,6 Despite these benefits, long-term adherence to exercise regimes is disappointing, and if exercise is not maintained its beneficial effects decline over time and finally disappear.7 The level of physical activity in older adults in the UK is low,8–11 and reduced further by pain-related fear of movement in those with osteoarthritis.12,13 Indeed, there is a culturally conditioned response to pain that encourages rest, which is inappropriate for most with this problem. How can patients with osteoarthritis be encouraged to increase their physical activity? In the similar field of low back pain, an evidence-based booklet has successfully changed patients' beliefs and behaviours. The effectiveness of The Back Book has been demonstrated in three randomised controlled trials (RCTs), one of which involved older people.14–17

The aim of this study was to develop an evidence-based booklet for patients with hip or knee osteoarthritis, encouraging physical activity and promoting autonomy. The theoretical framework underpinning this new booklet was Leventhal's theory of self-regulation, which states that our coping response to illness is governed by our beliefs about the nature of the illness: how well we understand the symptoms (its identity), its chronicity, its controllability, its cause, and the seriousness of its consequences.18 Educational interventions should emphasise that control is possible and within the individual's abilities. This model has been extended to include treatment beliefs, so that when considering an intervention, the perceived benefit in health gain is weighed up with the perceived cost in terms of pain, fear, and expectation of exacerbating the condition.19 In addition, social learning theory states that an individual's ability to perform an activity (self-efficacy) is crucial to behaviour change.20 Taking account of this theoretical framework, a series of evidence-based messages were written for the booklet using the method described next.

METHOD

Evidence-based narrative informed by a systematic review

A systematic review of reviews and evidence-based guidelines was performed to ensure that these messages were consistent with the evidence. The review was conducted in line with the guidelines reported by the Centre for Reviews and Dissemination (CRD).21 In order to inform the evidence review and to make it manageable, a preliminary list of statements was written. This list was based on background reading of the literature, input from clinical experts in the fields of rheumatology and orthopaedic surgery, and from previous experience of writing The Back Book.14 Systematic reviews and evidence-based guidelines that addressed these statements were identified. Any new message identified was incorporated into the reviewing process. The aim was to develop a final list of evidence-based messages, with each message underpinned by evidence identified by the review. The process of mapping reviews and guidelines to a preliminary list of statements allowed identification of any important messages that were not underpinned by published systematic reviews and guidelines. These evidence-based messages were then converted into patient-centred messages for inclusion in the final booklet narrative.

How this fits in

Hip and knee osteoarthritis are common causes of pain and disability, which can be improved by self-help approaches. However, regular exercise is uncommon in this group and the best method of encouraging increased activity is not known. An evidence-based booklet has been developed to encourage physical activity. The booklet was readable and found to be credible and useful to end-users.

Search strategy

The following databases were searched from inception to June 2007 using strategies designed for each database: MEDLINE, EMBASE, CINAHL, AMED, PsychINFO, SPORTdiscus, SIGLE, and the Cochrane library. The search strategy included a combination of the following text words and indexed terms: osteoarthritis, hip; osteoarthritis, knee; degenerative joint disease; epidemiology; diagnosis; patient education; exercise. Arthroplasty, total hip replacement, and total knee replacement were excluded (Appendix 1).

Inclusion criteria

The titles and abstracts were screened by two independent reviewers. Inclusion criteria were: systematic reviews and evidence-based guidelines of adults with osteoarthritis of the hip or knee. Studies of generalised osteoarthritis were allowed if they included the hip and knee. Exclusion criteria were: osteoarthritis in other sites, surgical interventions, childhood arthritis, rare or specific cases, animal studies, osteoarthritis prevention, methodological studies, physiology/biochemistry of normal cartilage, or commentary papers. Relevant studies were then categorised according to study type and the intervention or processes studied.

Quality assessment and data extraction

Full papers of systematic reviews and evidence-based guidelines were obtained and reassessed for relevance by two independent reviewers. Systematic reviews were included if they fulfilled the Database of Abstracts of Reviews (DARE) criteria.22 Evidence-based guidelines were included, but those not specific to osteoarthritis, narrative reviews, and quick guides for clinicians were excluded. Relevant studies were data extracted and quality assessed by one reviewer and checked by a second. The systematic review quality checklist was adapted from the DARE inclusion criteria,22 and the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) tool.23 The Appraisal of Guidelines for Research and Evaluation (AGREE) instrument was used as the checklist for guidelines.24

Matching the evidence to statements

Findings from the systematic reviews and guidelines were matched with the list of preliminary statements. The preliminary statements were modified, deleted, or added to accordingly, to form the final list of evidence-based messages (Table 1 and Appendix 2). The strength of the evidence for each statement was then rated with a star system, by two reviewers, and checked and amended by the other authors, based on the quantity, quality, and consistency of findings from multiple studies.25

Table 1.

Examples of evidence-based statements and patient-centred messages.

| Evidence-based statements | Grade | Patient-centred messages |

|---|---|---|

| Exercise | ||

| *** | We now know that inactivity and excessive rest is bad hip or knee joints with osteoarthritis. Research confirms that once you have osteoarthritis, regular moderate exercise does not make it worse — quite the reverse. Movement is good for you — and for your joints. Your whole body must keep active to stay healthy. Regular physical activity: strengthens and stretches muscles around your joints, keeps you supple by getting stiff joints moving and stopping them seizing up, makes your bones stronger, works your heart and lungs to make you fit, releases natural chemicals that reduce pain and make you feel good, and puts you in control. That is why exercise is one of the core treatments for osteoarthritis. It is a way to treat yourself. | |

|

** | |

| *** | ||

|

* | |

| * | ||

| Weight loss | ||

| *** | If you are overweight, losing weight is very beneficial for your joints. Most people will notice an improvement in joint pain and function after losing 5% of their body weight. | |

| Paracetamol | ||

| *** | There are many treatments that can help the pain. They may not remove the pain completely, but they can control it enough to let you get moving and active. Paracetamol is the simplest and safest painkiller. Take a regular dose rather than waiting for the pain to get too bad. | |

| Topical non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) | ||

| ** | Try massaging an anti-inflammatory gel directly over the painful joint — up to three times a day. It tends to be more effective for knee pain. | |

Key: evidence grade for the strength of scientific evidence:25 ***strong — generally consistent findings provided by systematic review(s) of multiple high-quality studies. **moderate — generally consistent findings provided by review(s) of fewer or lower-quality studies. *weak — limited evidence: provided by a single high-quality study; conflicting evidence: inconsistent findings provided by review(s) of multiple studies.

Patient-centred messages

The evidence-based messages were converted into patient-centred messages (Table 1 and Appendix 2), which were then incorporated into the narrative of a draft booklet. The booklet contained key messages about the nature of osteoarthritis and the beneficial effects of exercise. It adhered to guidelines for producing patient literature,26,27 similar to those used previously to develop effective patient educational material.14

Focus groups

The patient-centred messages contained in the narrative of the draft booklet were examined in four focus groups, after obtaining participants' informed written consent. Each focus group comprised patients with osteoarthritis of the hip or knee, recruited from a different general medical practice in Wrexham or Flintshire. Participants were identified by searching for osteoarthritis diagnostic Read codes on the practices' computerised patient record database (Appendix 3). Sampling was purposive and stratified according to age, affected joint site, and time since diagnosis (Appendix 4). The aim of these focus groups was not to change the underlying evidence-based messages, but to improve the phrasing of the patient-centred messages, and the emphasis of these messages within the booklet. The first focus group was conducted in the authors' department in Wrexham; the other three were conducted in the participants' surgery premises. All participants consented to take part and agreed that their comments be recorded, anonymised, and used for the purpose of the study. The groups were run by a moderator and co-moderator, using a topic guide (Appendix 5), and notes were taken of relevant points. The discussion was also recorded and the notes were checked against the recording for completeness. The notes were coded into themes, which were used to refine the messages in the booklet.

RESULTS

Overview of systematic reviews and guidelines

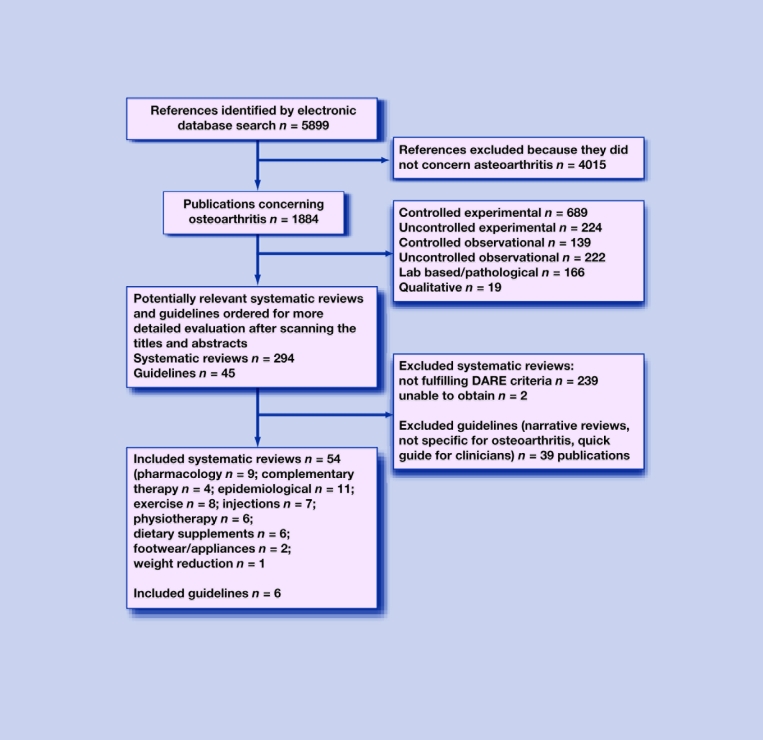

The search strategy identified 5899 references, of which 1884 concerned osteoarthritis of the hip or knee. There were 294 reviews, of which 54 met the DARE criteria for systematic reviews. These reviews concerned: pharmacological treatment (n = 9);28–36 risk factors and diagnosis (n = 11);37–47 exercise (n = 8);48–55 injections (n = 7);56–62 physiotherapy (n = 6);63–68 dietary supplements (n = 6);69–74 complementary therapies (n = 4);75–78 footwear and appliances (n = 2);79,80 and weight reduction (n = 1).81 In addition, 45 guidelines were identified including surgical and non-surgical treatment, of which six met the study inclusion criteria (Figure 1).4,5,82–85

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of included systematic reviews and guidelines.

Quality of identified systematic reviews and guidelines

All but one58 of the systematic reviews met more than half of the quality criteria in the checklist (Appendix 6). All but one85 of the guidelines were clear and well presented and described rigorous methods of development. The National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) guideline addressed all of the quality domains, apart from a statement of editorial independence (Appendix 7).

Evidence-based statements and patient-centred messages

The results of the review were developed into a list of evidence-based messages, which were then converted into patient-centred messages (Table 1 and Appendix 2) prior to incorporation into the booklet narrative.

Focus groups

The four focus groups consisted of 18 participants, lasted between 90 and 120 minutes, and were held between 20 October and 17 December 2008. There were eight men and 10 women, with a mean age of 67.5 years (Appendix 4). All of the participants found the booklet useful. It contained information about other options apart from surgery. One focus group stated that it confirmed what they already knew, but would be particularly helpful for those who are newly diagnosed. Several criticisms emerged from the first three focus groups, which guided further refinements in a final draft of the booklet.

Criticisms

The booklet was easy to read but repetitive, and the meaning of some terms was poorly understood. There was a lack of clarity about the cause of osteoarthritis. Many were surprised that the pain of osteoarthritis could improve in some people. The concept that joints have the potential for some repair was helpful but not clearly expressed. The message that heavy physical work increased the risk of osteoarthritis, but that physical activity was beneficial once it had developed, was contradictory. The hyaluranon injection message was misinterpreted as supporting its use.

Amendments

The booklet was shortened slightly and made less repetitive. The misunderstood terms were removed. The pathological description of osteoarthritis was clarified and illustrated with line drawings. The section on risk factors was clarified, the ageing process was acknowledged, and a statement was added that although various risk factors were known the cause of most osteoarthritis was not. Aggravating and relieving factors were made more explicit. The physical activity message was rephrased to state that intense physical demands helped to cause osteoarthritis, but that regular moderate exercise was beneficial, also that activity such as housework and gardening can be energetic but may not provide sufficient daily exercise. The section concerning hyaluranon was shortened and simplified, and the lack of evidence of long-term effectiveness was emphasised. One focus group thought that the booklet should include the contact details of support groups that patients with osteoarthritis can consult for help and advice. Selected (UK) sources were added. This final draft in the form of the publisher's proofs was given to the final focus group, which did not make any further suggestions to improve the text. Other emergent themes are described next.

‘Wear and tear’

Although most participants persisted in the belief that osteoarthritis was caused by ‘wear and tear’, they agreed that this term discouraged exercise. Doctors often used the term wear and tear, which affected patients' attitude towards exercise:

‘I think the idea of wear and tear is at the back of the mind and could discourage me from exercising or taking part in some sports such as badminton and some of these extreme sports in case it damages you more.’(patient 2)

One of the participants doubted the wear and tear theory and felt that inherited factors were more important.

Exercise beliefs reinforced

The booklet confirmed most participants' existing beliefs that exercise was important for health and that lack of mobility was detrimental. They reported that the message that moderate exercise was not harmful would encourage them to do more and to persevere. Even those with other limiting medical conditions were encouraged to do more. One participant agreed that exercise was good but was limited when the pain was too severe. There were some dissenting views; one argued that a new knee was treatment but that exercise was not, another that housework was sufficient and that the booklet emphasised more vigorous exercise, which would discourage some people.

‘I have already started walking and the booklet has confirmed that exercise won't cause me harm.’(patient 7)

Other themes

Other themes included the importance of weight loss, fear of dependency on pain killers, and feeling empowered to discuss referral for joint replacement surgery.

Reading age of the final booklet

The final booklet had means of 2.2 sentences per paragraph and 13.0 words per sentence, and had only 4% passive sentences.86 The scores for the Flesch Reading Ease test87 (71.3) and the Flesch–Kincaid Grade Level88 (6.5) indicated that the booklet should be easily understandable to a 12–13 year old.

DISCUSSION

Summary of main findings

The review identified 54 systematic reviews and six sets of management guidelines that were relevant to developing the new booklet. The evidence-based statements were converted into patient-centred messages and incorporated into a narrative for the draft booklet. A number of small changes were made to the narrative following three focus groups: repetition was reduced; the causes of osteoarthritis and contradictory messages about physical activity causing and being beneficial for osteoarthritis were clarified; and a misinterpreted message about hyaluranon injections was rewritten. A final draft of the booklet was found to be acceptable to the fourth and final focus group. All of the focus groups found the booklet was acceptable, relevant, and interesting. They were surprised that symptoms/function in osteoarthritis could improve and that joints had the potential for some repair. Exercise beliefs were reinforced by the booklet, and patients were empowered by the message about joint replacement.

Strengths and limitations of the study

The content of the booklet did not just rely on expert opinion, but on a literature review and focus groups. The review method was designed to obtain sufficient evidence for the booklet, and could have included a search of primary observational and experimental studies if there were gaps in the secondary evidence base. However, it was decided that sufficient evidence was available from systematic reviews and management guidelines for the purpose of writing an evidence-based booklet. Focus groups allowed clarification of a number of statements that were unclear to participants. The focus groups were all enthusiastic about the booklet and thought it would be particularly helpful for newly diagnosed patients. However, two of the focus groups had fewer than five participants, and patients with osteoarthritis of the hip were under-represented. The focus group sample was not stratified according to educational attainment, as it was not possible to obtain this information from the practices' computerised record databases. Osteoarthritis patients were not used to help write the initial patient-centred messages, which was a weakness in the method, but the lead author has personal experience of osteoarthritis of the hip.

Comparison with existing literature

The method used to develop the narrative of this booklet was similar to that used for The Back Book,14 and The Whiplash Book.89 However, it was decided to construct a list of preliminary statements to act as a framework for the review, and also to extract data from systematic reviews and guidelines because of the large body of research available in this field. The evidence-based statements are broadly similar to the recommendations of the NICE osteoarthritis guidelines,5 although some recommendations regarding glucosamine and acupuncture differed somewhat.

Implications for future research and clinical practice

Alongside exercise and weight loss, the provision of information and advice is one of the core interventions for osteoarthritis in the NICE management guidelines.5 The focus groups found this booklet to be a useful source of advice, particularly for those who are newly diagnosed. Further work could also test the acceptability of the booklet in a geographically wider population in the UK and in other countries. The next step is to test whether this booklet can change illness and treatment beliefs in patients with osteoarthritis, and whether it influences exercise behaviour and health status. A pragmatic randomised controlled trial is planned, comparing the new booklet with another commonly used booklet that has less emphasis on physical activity and exercise.45

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all of the patients who participated in the focus groups, and colleagues from the Department of Primary Care and Public Health, Cardiff University for their comments and suggestions.

Appendix 1. MEDLINE search strategy (adapted for other databases).

osteoarthritis, hip/

osteoarthritis, knee/

((hip or knee) adj3 (arthritis or osteoarthtitis or arthrosis or degenerative joint disease)).ti,ab

OR/1–3

(etiology or aetiology or caus$).ti,ab

epidemiology/

epidemiologic studies/

epidemiologic factors/

epidemiolog$.ti,ab

morbidity/

incidence/

prevalence/

risk factors/

(morbidity or incidence or prevalence or risk or progres$ or prognosis).ti,ab

OR/6–14

diagnosis/

(diagnos$ or symptom$ or sign$ or test$ or investigat$).ti,ab

16 or17

self efficacy/

self care/

(belief$ or fear avoidance or self efficacy or self management or self regulation or stage$ of change or catastrophis$ or catastrophiz$).ti,ab

OR/19–21

patient education/

(education or instruction or advi$ or guidance or recommend$).ti,ab

23 or 24

Exercise/

Walking/

(exercise$ or activ$ or swim$ or cycl$ or walk$).ti,ab

26 or 27

5 or 15 or 18 or 22 or 25 or 29

4 and 30

Appendix 2. Evidence-based statements and patient-centred messages.

| Evidence-based statements | Grade | Patient-centred messages |

|---|---|---|

| Diagnosis | ||

| Radiographic changes are only weakly associated with pain and disability in osteoarthritis of the knee. The results of knee x-rays should not be used in isolation when assessing patients with knee pain.47 | ** | A diagnosis of osteoarthritis can be made without x-rays, and is based on patients' symptoms and examination findings. |

| Epidemiology – risk factors | ||

| There is moderate evidence of a greater incidence of osteoarthritis of the hip and knee in women. There is moderate evidence of a greater prevalence of osteoarthritis of the knee in women but not for osteoarthritis of the hip. In terms of osteoarthritis severity, there is moderate evidence that women had more severe knee osteoarthritis especially in the older than 55 years age group.5,43 | ** | We don't really know what causes the condition, and we don't know how to prevent it. There is no single cause, but various things are thought to be involved: Genetic factors are important — it seems some people are just more prone than others: osteoarthritis can run in families, and some types are more common in certain ethnic groups. |

| There is moderate evidence for a positive influence of obesity on the development of osteoarthritis of the hip.5,39 | ** | |

| There is a moderate association between age and the prevalence of osteoarthritis, but osteoarthritis is not an inevitable consequence of ageing.5,40 | ** | People who are very overweight are at greater risk, and it is a little more common in women. |

| There is strong evidence of a positive relationship between work-related bending and knee osteoarthritis.37 | *** | Various physical factors may play a part, but they do not have a consistent effect: previous damage to the joint surface, some physically intense occupations and sports, reduced muscle strength, abnormal joint shape or alignment. and the occurrence of osteoarthritis of the hip in men.5,38,46 |

| There is a positive association between heavy physical workload in occupations such as farming or lifting weights heavier than 25 kg for more than 10 years38 | ** | |

| There is moderate evidence of a positive relationship between recreational and physical sporting activities and the occurrence of hip and knee pain, and the risk increases with the intensity and duration of exposure.5,41 | ** | Age is obviously the main factor — painful osteoarthritis is uncommon in younger people. But that does not mean things inevitably get worse. Nor does it meant that all your joints will be affected. |

| The evidence that hip dysplasia influences the occurrence of hip osteoarthritis in older adults is limited.42 | * | |

| Heritability is estimated to account for 40–60% for hip and knee osteoarthritis, although the responsible genes are unknown.5 | * | |

| There is a moderate association between hyaluronic acid serum levels and generalised osteoarthritis and radiological progression of knee osteoarthritis.46 | ** | |

| Epidemiology – prognostic factors | ||

| There is limited evidence that increased laxity, proprioceptive inaccuracy, older age, body mass index, and increased knee pain intensity are associated with deterioration of functional status in knee OA during the first three years of follow-up.44 | * | The pain you feel won't necessarily get worse – in about one-third of people with osteoarthritis of the hip or knee it actually improves. Of course, some things can make your pain worse, such as being overweight and letting your muscles get weak. Importantly though, there are also things that can help, such as regular exercise, keeping the muscles around the joint strong, keeping a positive attitude, believing that you are in control and can help yourself, and getting the support of friends and family. |

| There is limited evidence that greater muscle strength, better mental health, better self-efficacy, social support, and more aerobic exercise decrease the likelihood of functional deterioration in knee osteoarthritis.44 | * | |

| There is limited evidence for a lack of association between functional status in the first three years of follow-up and joint alignment, sex, physical activity, role functioning, comorbidity, marital status, severity of osteoarthritis and bilateral disease in osteoarthritis of the knee.44 | * | |

| There is conflicting evidence for an association between radiological change and functional status in the first three years of follow-up of knee osteoarthritis.44 | * | |

| There is strong evidence that knee injury and regular sporting activities are not associated with radiological progression of knee osteoarthritis.45 | *** | |

| There is moderate evidence of a positive relationship between atrophic bone response and faster progression of hip osteoarthritis.40 | ** | |

| There is limited evidence for a more rapid progression of hip osteoarthritis when there is a superolateral progression of the femoral head compared with medial migration.40 | * | |

| There is limited evidence for an absence of a relation between hip dysplasia and progression of hip osteoarthritis.40 | * | |

| There is conflicting evidence for an association between female sex and progression of hip osteoarthritis.40 | * | |

| Exercise | ||

| There is strong evidence that both strengthening and cardiovascular exercise are effective for reducing pain and improving function in the short-term in knee osteoarthritis.4,5,48–50,52,53,82,84,85 | *** | We now know that inactivity and excessive rest is bad for hip or knee joints with osteoarthritis. Research confirms that once you have osteoarthritis regular moderate exercise does not make it worse — quite the reverse. Movement is good for you — and for your joints. |

| There is moderate evidence that no difference in effectiveness was found between different intensities of exercise for knee osteoarthritis.51 | ** | Your whole body must keep active to stay healthy. Regular physical activity: strengthens and stretches muscles around your joints, keeps you supple by getting stiff joints moving and stopping them seizing up, makes your bones stronger, works your heart and lungs to make you fit, releases natural chemicals that reduce pain and make you feel good, and puts you in control. That is why exercise is one of the core treatments for osteoarthritis. It is a way to treat yourself. |

| There is strong evidence that integrating self-management strategies with exercise is effective for reducing pain and improving function in knee osteoarthritis.54,55 | *** | |

| There is limited evidence that integrating self-management strategies with exercise is effective for reducing pain and improving function in hip osteoarthritis.54 | * | |

| There is limited evidence that both strengthening and cardiovascular exercise are effective for reducing pain and improving function in the short term in hip osteoarthritis.4,5,48,50,52 | * | |

| Weight loss | ||

| There is strong evidence that a 5% weight reduction will result in moderate improvement in disability in overweight patients with knee osteoarthritis.5,81 | *** | If you are overweight, losing weight is very beneficial for your joints. Most people will notice an improvement in joint pain and function after losing 5% of their body weight. |

| Paracetamol | ||

| There is strong evidence that paracetamol has a small effect on pain and has few adverse reactions in osteoarthritis of the hip or knee compared with placebo, in the short term.5,33 | *** | There are many treatments that can help the pain. They may not remove the pain completely, but they can control it enough to let you get moving and active. Paracetamol is the simplest and safest painkiller. Take a regular dose rather than waiting for the pain to get too bad. |

| Topical non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) | ||

| There is moderate evidence that topical NSAIDs have a small effect on pain in knee osteoarthritis compared with placebo, and few adverse effects in the short term.5,32,34,83,85 | ** | Try massaging an anti-inflammatory gel directly over the painful joint – up to three time a day. It tends to be more effective for knee pain. |

| Prescribed medication — oral NSAIDs | ||

| There is strong evidence that oral NSAIDs have a small to moderate effect on pain in osteoarthritis of the hip and knee compared with placebo, in the short term.5,28–30,35,83,85 | *** | Anti-inflammatory tablets can be useful when paracetamol or the gels don't work. Ibuprofen is often prescribed but you can buy it over the counter: it works well. If it does not, it might be worth trying stronger anti-inflammatories such as diclofenac or naproxen, which have to be prescribed by your doctor. All drugs can have side-effects. Anti-inflammatory drugs can cause stomach ulcers. |

| There is moderate evidence that oral NSAIDs have a small additional benefit in terms of improving stiffness, physical function, and global assessment in knee and hip osteoarthritis compared with paracetamol.5,29,30,83 | ** | |

| There is strong evidence that patients preferred NSAIDs compared with paracetamol.30 | ||

| Prescribed medication — opioids | ||

| There is moderate evidence that tramadol has a small to moderate effect in terms of pain and function in both short-and long-term treatment in hip and knee osteoarthritis compared with placebo.5,36,83,85 | ** | Stronger painkillers like codeine or tramadol can also be prescribed by your doctor. They are the same class of drug as morphine, but milder. They are often combined with paracetamol in the same tablet (e.g. co-codamol). |

| Thermotherapy | ||

| There is limited evidence for the benefit of local heat or cold for knee osteoarthritis in terms of pain and function.5,67,82 | * | Heat or cold can be used for short-term relief of pain, particularly for flare ups. |

| There is limited evidence that ice massage can be used to improve range of movement and that cold packs can be used to decrease swelling.67 | * | |

| Glucosamine | ||

| There is limited evidence that glucosamine may be effective and safe for improving pain and function in knee osteoarthritis and in delaying its progression.69–72 | * | The food supplement glucosamine sulphate taken in a single dose of 1.5 g may be helpful in improving pain and function.It is safe and worth trying. |

| Acupuncture | ||

| There is moderate evidence that acupuncture is safe and effective compared with placebo in terms of pain and function in patients with knee osteoarthritis, in the short-term.5,78,85 | ** | Acupuncture is safe and can reduce pain and improve function. Not everyone benefits, but it is worth trying a short course. |

| Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) | ||

| There is moderate evidence that TENS has a moderate effect on reducing pain and stiffness in knee osteoarthritis.64,82,85 | ** | TENS can be useful for reducing pain and stiffness in osteoarthritis and help you get moving and active. |

| Herbal remedies | ||

| There is moderate evidence that avocado-soybean unsaponifiables (ASU) may be effective for long-term symptomatic treatment of hip osteoarthritis and may help to reduce the consumption of NSAIDs.76 | ** | Most of the many claims for herbal remedies are not backed up by scientific evidence. |

| There is limited evidence for other herbal medicines in terms of pain and function in knee and hip osteoarthritis.75–77 | * | |

| Electrotherapy | ||

| There is no evidence that therapies such as laser, pulse electromagnetic therapy, ultrasound are more effective for osteoarthritis of the hip or knee in terms of pain and function, compared with placebo.5,63,65,68,82,83 | * | Laser, pulse electromagnetic therapy, ultrasound are not effective. |

| Manual therapy | ||

| There is strong evidence for the benefit of manual therapy alone for hip OA in terms of pain and function compared with exercise.5,84 | *** | Manual therapy for OA hip includes stretching of shortened muscles around the hip joint and manual traction. Mobilising stiff joints and stretching shortened muscles, particularly around the hip joint by physiotherapists, osteopaths or chiropractors can be helpful. |

| There is moderate evidence that manual therapy combined with exercise is effective in terms of pain and function.84 | ** | |

| Aids and devices | ||

| There is limited evidence for bracing, joint supports or insoles in patients with biomechanical joint pain or instability.5,79,80,83,85 | * | Sometimes the leg is not aligned properly, which will put extra strain on the joints — insoles can help. An unstable knee joint can be helped by a brace to support the joint. |

| Intra-articular steroid injections | ||

| There is strong evidence that intra-articular steroid injections were safe and provided short-term relief of pain in knee osteoarthritis up to 4 weeks post-injection.5,57,58,62,85 | *** | Steroid injections into joints can provide short-term pain relief and can be useful for settling flare ups. |

| There is limited evidence for the efficacy of intra-articular steroid injections for hip osteoarthritis.5 | * | |

| Viscosupplementation | ||

| Viscosuplementation appears to be safe and has a small effect on osteoarthritis of the knee in terms of pain, function, and patients'global assessment. However, it is unlikely to be cost-effective.56,59–61 | * | Hyaluranon injections can improve lubrication inside the affected joint. But the small benefit only lasts up to three months. |

| Arthroscopic lavage and debridement | ||

| There is a lack of evidence for the effectiveness of arthroscopic lavage and debridement compared with tidal irrigation or placebo in terms of pain and function in knee osteoarthritis.5 | * | Arthroscopy involves inserting a fibre-optic tube into the knee joint, washing out the joint, and sometimes trimming damaged cartilage. It does not give a lasting benefit in most cases of osteoarthritis. |

| Arthroplasty | ||

| There is strong evidence that restriction of referral for arthroplasty of osteoarthritis patients should not be based on body mass index, age or comorbidities.5 | *** | Joint replacement surgery is used when osteoarthritis is having a large effect on quality of life, and non-surgical treatments have failed to improve pain and function. It is best to have this surgery before there is long-term loss of function and severe pain. Old age, smoking, obesity, and other illnesses should not be barriers to referral for this operation |

Key: evidence grade for the strength of scientific evidence:25 ***strong — generally consistent findings provided by systematic review(s) of multiple high-quality studies. **moderate — generally consistent findings provided by review(s) of fewer or lower-quality studies. *weak — limited evidence: provided by a single high-quality study; conflicting evidence: inconsistent findings provided by review(s) of multiple studies.

Appendix 3. Read codes for eligible patients (>50 years old).

| Included Read codes | |

| N05 (and below) | osteoarthritis |

| 14G2 | H/O osteoarthritis |

| N06z5 | hip arthritis |

| N06z6 | knee arthritis |

| N094K | arthralgia of hip |

| N094M | arthralgia of hip |

| 1M10 | knee pain |

| Excluded Read codes | |

| M160 | psoriatic arthropathy |

| N04 (and below) | inflammatory polyarthropathy |

| 7K2 (and below) | hip joint operations |

| 7K3 (and below) | knee joint operations |

Appendix 4. Composition of the focus groups.

| Focus group | Patient number | Practice location | Sex | Age (years) | Hip or knee | Duration of symptoms |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | City centre Wrexham | Male | 77 | Both | 16 years |

| 2 | Female | 73 | Hip | 5 years | ||

| 3 | Female | 68 | Knee | 16 years | ||

| 4 | Female | 64 | Knee | 1 month | ||

| 5 | Male | 70 | Knee | 7 years | ||

| 6 | Male | 70 | Hip | 5 years | ||

| 2 | 7 | Semi-rural village in Flintshire | Female | 55 | Knee | 4 months |

| 8 | Male | 75 | Knee | 16 years | ||

| 9 | Male | 52 | Hip | 5 years | ||

| 10 | Female | 64 | Knee | 2 years | ||

| 11 | Female | 66 | Knee | 5 years | ||

| 3 | 12 | Industrial town in Flintshire | Male | 61 | Knee | 3 months |

| 13 | Female | 71 | Both | 3 months | ||

| 14 | Male | 64 | Both | 6 months | ||

| 15 | Female | 65 | Knee | 10 months | ||

| 4 | 16 | Ex-mining village in Wrexham | Female | 88 | Knee | 12 months |

| 17 | Male | 59 | Knee | 4 years | ||

| 18 | Female | 73 | Knee | 4 years | ||

Appendix 5. Topic guide for focus group.

-

Is the booklet written in a clear and simple language?

Is it clearly laid out?

Is it easy to follow?

Are there any unfamiliar words?

-

Do you really understand the content of the booklet?

What do you think about the message that exercise and physical activity is good for osteoarthritis? Is it clear? Do you believe it? Would the booklet change how or what you think about exercise? Would it change how much exercise you do?

In the booklet we have criticised the idea of ‘wear and tear’ causing osteoarthritis? Do you believe that this is right? Is this criticism helpful or unhelpful to you?

Do you think the ‘wear and tear’ idea discourages people from exercise?

What do you think about the message that the joint has some ability to repair itself? Is this an important message? Is it expressed clearly?

Do you feel that the cause of osteoarthritis is adequately explained? Do you believe it?

What do you think about how osteoarthritis is diagnosed?

-

What do you think about the other messages?

weight loss

safe pain relief with regular paracetamol

topical anti-inflammatory rubs

physiotherapy

were the exercises easy to follow?

hot + cold

prescribed medication

joint injections

arthroscopy

joint replacement

Explore NSAIDs reaction in more detail

-

Do you find the messages interesting?

How interesting did you find the booklet to read?

Were any parts not interesting? (which?)

Do you think the booklet could be made more interesting? (how?)

-

Is there anything new to you?

Moderator to summarise the main points of the booklet, then ask:

How much of this information is new to you?

Which points were new?

Is there any information in the booklet that surprised you? (what? in what way?)

Did you have any questions in your mind about hip or knee pain that our booklet didn't answer?

-

Do you believe in the facts presented?

Thinking especially about any points that were new to you or that you found surprising, was there anything you disagree with?

Will reading the booklet change the way you think about osteoarthritis? (in what way?)

Will reading the booklet change the way you behave? (in what way?)

Would you recommend the booklet to a friend? (why/why not?)

The layout of this hip and knee book will be similar to The Back Book. What do you think?

Are there any points that are MISSING? Example, how did receiving a diagnosis of osteoarthritis change how you thought about yourself, how active you should be, and how much you should exercise?

Appendix 6. Quality assessment of systematic reviews.

| Checklist adapted from DARE criteria22 and CASP tool23 | Aggarwal 200456 | Arrich 200560 | Arroll 200457 | Bedson 200847 | Bellamy 200661 | Bellamy 200662 | Belo 200746 | Biswal 200632 | Bjordal 200428 | Bjordal 200735 | Brosseau 200063 | Brosseau 200266 | Brosseau 200351 | Brosseau 200367 | Brouwer 200579 | Cepada 200736 | Christensen 200781 | Devos-Comby200655 | Ernst 200376 | Fransen 200250 | Godwin 200458 | Lee 200029 | Lievense 200138 | Lievense 200239 | Lievense 200240 | Lievense 200441 | Lievense 200442 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Well-defined review question | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1. Were inclusion/exclusion reported criteria separately to review questions? | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| 2. Did inclusion/exclusion criteria relate to study design of interest? | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| 3. Did inclusion/exclusion criteria relate to participants of interest? | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| 4. Did inclusion/exclusion criteria relate to intervention of interest? | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | – | + | + | + | + | + | N/A | – | + | + | + |

| 5. Did inclusion/exclusion criteria relate to outcomes of interest? | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | – | + | – | – | + | + | + | + | + |

| 6. Were inclusion/exclusion criteria valid? | + | + | + | – | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Comprehensive literature search | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 7. Was there evidence of a comprehensive search of the literature? | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| 8. Did search include attempt to identify unpublished studies? | – | – | – | – | + | + | – | + | – | – | – | – | – | + | – | + | – | – | + | – | – | + | – | – | – | – | – |

| 9. Was grey literature searched? | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | + | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | + | – |

| 10. Were non-English language studies considered? | – | – | – | – | + | + | + | – | + | + | + | + | + | – | + | + | + | – | + | – | + | + | + | + | + | – | + |

| Systematic process for decision on retrieval and relevance | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 11. Did more than one reviewer assess references for relevancy? | ? | ? | – | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | + | + | + | + | + | ? | ? | ? | – | – | + | + | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? |

| 12. If no did more than one reviewer assess a sample of the references? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | N/A | NA | N/A | N/A | N/A | ? | ? | ? | – | – | N/A | N/A | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? |

| 13. Did more than one reviewer assess retrieved studies for inclusion? | ? | ? | – | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | + | + | + | + | + | ? | ? | ? | – | + | + | + | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? |

| 14. If no, did more than one independent reviewer assess a sample? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | N/A | NA | N/A | N/A | N/A | ? | ? | ? | – | N/A | N/A | N/A | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? |

| Quality assessment | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 15. Was validity systematically assessed using a checklist? | + | + | + | – | + | + | + | – | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | – | + | + | – | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| 16. Were validity criteria applied by more than one reviewer? | ? | + | + | – | – | + | + | ? | ? | ? | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | – | – | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| 17. Was validity taken into account in synthesis? | – | + | + | – | + | – | + | – | + | – | – | – | + | + | – | – | + | – | – | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Systematic data extraction | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 18. Were data extracted using standardised format? | ? | + | – | – | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | ? | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | ? | + | + |

| 19. Was data extraction performed by more than one reviewer? | ? | + | + | – | – | – | ? | ? | ? | ? | + | + | + | + | + | + | ? | ? | – | + | ? | + | + | + | ? | + | + |

| 20. If no, was data extraction checked by second independent reviewer? | ? | N/A | N/A | – | + | + | ? | ? | ? | ? | N/A | NA | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | ? | ? | – | N/A | ? | N/A | N/A | N/A | ? | N/A | N/A |

| Appropriate synthesis | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 21. Are primary studies presented in sufficient detail? | – | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | – | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| 22. Have the primary studies been synthesised appropriately? | – | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | ? | + | + | + | + | – | + | – | + | – | + | + | + | + |

| 23. Has meta-analysis been performed? | – | + | + | – | + | + | – | + | + | + | – | – | + | + | – | + | – | + | – | + | + | + | – | – | – | – | – |

| 24. If yes, has heterogeneity been formally assessed? | N/A | + | + | – | + | – | N/A | + | + | + | N/A | NA | – | – | N/A | + | N/A | + | N/A | + | + | + | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | – |

Key: + item properly addressed; — item not properly addressed; ? insufficient information; N/A not applicable.

Appendix 6. Quality assessment of systematic reviews

| Checklist adapted from DARE criteria22 and CASP tool23 | Little 200077 | Long 200175 | Maetzel 199737 | McAlindon 200069 | McCarthy 200668 | Osiri 200064 | Patrella 200049 | Pelland 200452 | Poolsup 200571 | Reichebach 200773 | Reilly 200580 | Richy 200370 | Rintelen 200674 | Robinson 200165 | Roddy 200553 | Srikanth 200543 | Towheed 200572 | Towheed 200634 | Towheed 200633 | Van Baar48 | Van Dijk 200644 | Vignon 200645 | Walsh 200654 | Wang 200459 | Wegman 200430 | White 200778 | Zhang 200431 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Well-defined review question | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1. Were inclusion/exclusion criteria reported separately to review questions? | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | – | + | + | + | + | + |

| 2. Did inclusion/exclusion criteria relate to study design of interest? | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | – | + | + | + | + | + |

| 3. Did inclusion/exclusion criteria relate to participants of interest? | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| 4. Did inclusion/exclusion criteria relate to intervention of interest? | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | N/A | + | + | + | + | – | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| 5. Did inclusion/exclusion criteria relate to outcomes of interest? | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | – | + | – | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | – | + | + | + | + | + |

| 6. Were inclusion/exclusion criteria valid? | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | – | + | + | + | + | + |

| Comprehensive literature search | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 7. Was there evidence of a comprehensive search of the literature? | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | – | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| 8. Did search include attempt to identify unpublished studies? | + | + | – | + | + | + | – | – | – | + | + | + | + | – | – | + | – | + | – | – | – | + | – | – | – | + | + |

| 9. Was grey literature searched? | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| 10. Were non-English language studies considered? | + | + | + | + | – | – | + | + | – | + | + | + | + | + | – | – | + | + | – | + | + | + | – | – | + | + | – |

| Systematic process for decision on retrieval and relevance | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 11. Did more than one reviewer assess references for relevancy? | – | – | + | ? | ? | + | ? | + | ? | + | ? | – | + | + | ? | – | + | – | + | + | + | – | + | + | ? | + | – |

| 12. If no did more than one reviewer assess a sample of the references? | – | ? | N/A | ? | ? | N/A | ? | N/A | ? | N/A | ? | ? | N/A | N/A | ? | – | N/A | – | N/A | N/A | N/A | – | N/A | N/A | ? | N/A | – |

| 13. Did more than one reviewer assess retrieved studies for inclusion? | + | + | + | ? | ? | + | ? | + | ? | + | ? | + | + | + | ? | – | + | – | + | + | + | – | + | + | ? | + | – |

| 14. If no, did more than one independent reviewer assess a sample? | N/A | N/A | N/A | ? | ? | N/A | ? | N/A | ? | N/A | ? | N/A | N/A | N/A | ? | – | N/A | – | N/A | N/A | N/A | – | N/A | N/A | ? | N/A | – |

| Quality assessment | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 15. Was validity systematically assessed using a checklist ? | + | + | + | + | + | + | ? | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| 16. Were validity criteria applied by more than one reviewer? | + | ? | + | + | + | + | ? | + | ? | + | + | + | + | + | + | – | + | – | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| 17. Was validity taken into account in synthesis? | – | – | – | + | – | + | ? | – | – | + | – | – | + | – | + | – | – | – | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Systematic data extraction | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 18. Were data extracted using standardised format? | + | + | + | + | ? | + | ? | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| 19. Was data extraction performed by more than one reviewer? | + | – | + | + | ? | + | ? | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | – | + | + | + | + | + | + | ? | + | + |

| 20. If no, was data extraction checked by second independent reviewer? | N/A | + | N/A | N/A | ? | N/A | ? | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | – | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | ? | N/A | N/A |

| Appropriate synthesis | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 21. Are primary studies presented in sufficient detail? | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | – | + | + | + | + | – | – | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| 22. Have the primary studies been synthesised appropriately? | + | – | – | + | + | + | + | – | + | + | – | + | + | – | + | + | – | + | + | ? | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| 23. Has meta-analysis been performed? | + | – | – | + | + | + | – | – | + | + | – | + | + | – | + | + | – | + | + | + | – | – | – | + | + | + | + |

| 24. If yes, has heterogeneity been formally assessed? | + | N/A | N/A | + | + | + | N/A | N/A | + | + | – | + | – | N/A | + | + | N/A | + | + | + | N/A | N/A | N/A | + | + | + | + |

Key: + item properly addressed; — item not properly addressed; ? insufficient information; N/A not applicable.

Appendix 7. Quality assessment of management guidelines.

| Appraisal of Guideline using the AGREE instrument24 | NICE (5) | EULAR (83) | Ottawa (84) | Philadelphia (82) | MOVE (4) | Singapore(85) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scope/purpose | ||||||

| 1. Overall objective described | 4 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| 2. Clinical question described | 4 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 4 | 1 |

| 3. Target patient population | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| Domain score (%) | 100 | 100 | 89 | 78 | 100 | 67 |

| Stakeholder involvement | ||||||

| 4. Development group representatives | 4 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 |

| 5. Patients'views and preferences | 4 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 6. Target users clearly defined | 4 | 1 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 3 |

| 7. Guideline piloted with users | 2 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 1 |

| Domain score (%) | 83 | 17 | 50 | 75 | 42 | 33 |

| Rigour of development | ||||||

| 8. Systematic search methods | 4 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 2 |

| 9. Criteria to select evidence | 3 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 1 |

| 10. Clear methods to formulate recommendations | 4 | 4 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 1 |

| 11. Health benefits, side-effects, and risk considered | 4 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 12. Explicit link between recommendation and evidence | 3 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| 13. External review by experts | 4 | 1 | 4 | 3 | 1 | 1 |

| 14. Procedure for updating | 4 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 4 |

| Domain score (%) | 90 | 81 | 62 | 62 | 62 | 43 |

| Clarity/presentation | ||||||

| 15. Specific and unambiguous recommendation | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 4 |

| 16. Different options clearly presented | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 3 |

| 17. Key recommendations | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 4 |

| 18. Supported with tools | 4 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Domain score (%) | 100 | 75 | 100 | 50 | 50 | 67 |

| Applicability | ||||||

| 19. Organisational barriers discussed | 2 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 20. Cost implications considered | 4 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 21. Monitoring and audit criteria | 4 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Domain score (%) | 78 | 22 | 22 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Editorial independence | ||||||

| 22. Editorial independence | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 |

| 23. Conflicts of interest recorded | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 1 |

| Domain score (%) | 33 | 33 | 33 | 33 | 83 | 17 |

| Overall assessment | strongly recommend | recommend | recommend | recommend | recommend | do not recommend |

Funding body

This work was supported by a project grant from the Wales Office of Research and Development for Health and Social Care (Ref 06/2/234).

Ethical approval

Ethical approval was obtained from the North Wales East Research Ethics Committee (REC reference 09/WNo03/5).

Competing interests

Cardiff University and Kim Burton will receive royalties from sale of the booklet. The other authors have stated that there are none.

Discuss this article

Contribute and read comments about this article on the Discussion Forum: http://www.rcgp.org.uk/bjgp-discuss

REFERENCES

- 1.Van Baar ME, Assendelft WJ, Dekker J, et al. Effectiveness of exercise therapy in patients with osteoarthritis of the hip or knee: a systematic review of randomized clinical trials. Arthritis Rheum. 1999;42(7):1361–1369. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(199907)42:7<1361::AID-ANR9>3.0.CO;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McCarthy CJ, Oldham JA. The effectiveness of exercise in the treatment of osteoarthritic knees: a critical review. Phys Ther. 1999;4:241–250. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brosseau L, MacLeay L, Robinson VA, Tugwell P, Wells G. Intensity of exercise for the treatment of osteoarthritis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003;(2) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004259. CD004259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Roddy E, Zhang W, Doherty M, et al. Evidence based recommendations for the role of exercise in the management of osteoarthritis of the hip or knee — the MOVE consensus. Rheumatology. 2005;44(1):67–73. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keh399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.National Collaboration Centre for Chronic Conditions. National clinical guideline for the care and management of osteoarthritis in adults. London: Royal College of Physicians; 2008. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ashworth NL, Chad KE, Harrison EL, et al. Home versus center based physical activity programs in older adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;(1) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004017.pub2. CD004017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Van Baar ME, Dekker J, Oostendorp RA, et al. Effectiveness of exercise in patients with osteoarthritis of hip or knee: nine months follow up. Ann Rheum Dis. 2001;60(12):1123–1130. doi: 10.1136/ard.60.12.1123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.The Information Centre. Health Survey for England 2006 latest trends. http://www.ic.nhs.uk/webfiles/publications/HSE06/Health%20Survey%20for%20England%202006%20Latest%20Trends.pdf (accessed 23 Nov 2009)

- 9.Welsh Assembly Government. Welsh Health Survey 2004/05. http://new.wales.gov.uk/topics/statistics/publications/publication-archive/health-survey2004–05/?lang=en (accessed 23 Nov 2009)

- 10.The Scottish Executive. The Scottish Health Survey 2003. Volume 2 Adults. http://www.scotland.gov.uk/Resource/Doc/76169/0019729.pdf (accessed 23 Nov 2009)

- 11.Central Survey Unit. Northern Ireland Health and Social Wellbeing Survey 2005/2006. http://www.csu.nisra.gov.uk/HWB%200506%20topline%20bulletin.pdf (accessed 23 Nov 2009)

- 12.Heuts PHTG, Vlaeyen JWS, Roelofs J, et al. Pain-related fear and daily functioning in patients with osteoarthritis. Pain. 2004;110(1–2):228–235. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2004.03.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hendry MA, Williams NH, Wilkinson C, et al. Motivation to exercise in arthritis of the knee: a qualitative study in primary care patients. Fam Pract. 2006;23(5):558–567. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cml022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Roland M, Waddell G, Klaber-Moffett J, et al. The back book. London: The Stationery Office; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Burton AK, Waddell G, Tillotson KM, Summerton N. Information and advice to patients with back pain can have a positive effect: a randomised controlled trial of a novel educational booklet. Spine. 1991;24(23):2484–2891. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199912010-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Coudeyre E, Tubach F, Rannou F, et al. Effect of a simple information booklet on pain persistence after an acute episode of low back paa non-randomized trial in a primary care setting. PloS ONE. 2007;2(1):e706. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kovacs FM, Abraira V, Santos S, et al. Spanish Back Pain Research Network. A comparison of two short education programs for improving low back pain related disability in the elderly: a cluster randomised controlled clinical trial. Spine. 2007;32:1053–1059. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000261556.84266.0f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Horne R. Patients' beliefs about treatment: the hidden determinant of treatment outcome? J Psychosom Res. 1999;47(6):491–495. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(99)00058-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cameron LD, Leventhal H. The self-regulation of health and illness behaviour. New York, NY: Routledge; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bandura A. Social cognitive theory: an agentic perspective. Annu Rev Psychol. 2001;52:1–26. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.NHS Centre for Reviews and Dissemination. Undertaking systematic reviews of research on effectiveness: CRD's guidance for those carrying out or commissioning reviews. 2nd edn. York: NHS CRD, University of York; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 22.NHS Centre for Reviews and Dissemination. Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effectiveness (DARE) York: NHS CRD, University of York; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Oxman AD, Cook DJ, Guyatt GH. Users' guides to the medical literature. VI. How to use an overview. JAMA. 1994;272(17):1367–1371. doi: 10.1001/jama.272.17.1367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.AGREE Collaboration. Appraisal of Guidelines for Research and Evaluation (AGREE) Instrument, 2001. http://fhswedge.csu.mcmaster.ca/pebc/agreetrust/docs/AGREE_Instrument_English.pdf (accessed 23 Nov 2009)

- 25.Waddell G, Burton AK. Is work good for your health and well-being? London: The Stationery Office; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Department of Health. Toolkit for producing patient information. London: Department of Health; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Raynor DK, Blenkinsopp DK, Knapp P, et al. A systematic review of quantitative and qualitative research on the role and effectiveness of written information available to patients about individual medicines. Health Technol Assess. 2007;11(5):1–160. doi: 10.3310/hta11050. iii. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bjordal JM, Ljunggren AE, Klovning A, Slordal L. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, including cyclo-oxygenase-2 inhibitors, in osteoarthritic knee pameta-analysis of randomised placebo controlled trials. BMJ. 2004;329(7478):1317. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38273.626655.63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lee C, Straus WL, Balshaw R, et al. A comparison of the efficacy and safety of nonsteroidal antiinflammatory agents versus acetaminophen in the treatment of osteoarthritis: a meta-analysis. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;51(5):746–754. doi: 10.1002/art.20698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wegman A, van der Windt D, van Tulder M, et al. Nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs or acetaminophen for osteoarthritis of the hip or knee? A systematic review of evidence and guidelines. J Rheumatol. 2004;31(2):344–354. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhang W, Jones A, Doherty M. Does paracetamol (acetaminophen) reduce the pain of osteoarthritis? A meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Ann Rheum Dis. 2004;63(8):901–907. doi: 10.1136/ard.2003.018531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Biswal S, Medhi B, Pandhi P. Long-term efficacy of topical non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in knee osteoarthritis: meta-analysis of randomized placebo controlled clinical trials. J Rheumatol. 2006;33(9):1841–1844. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Towheed TE, Maxwell L, Judd MG, et al. Acetaminophen for osteoarthritis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;(1) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004257.pub2. CD004257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Towheed TE. Pennsaid therapy for osteoarthritis of the knee: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Rheumatol. 2006;33(3):567–573. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bjordal JM, Klovning A, Ljunggren AE, Slordal L. Short-term efficacy of pharmacotherapeutic interventions in osteoarthritic knee paa meta-analysis of randomised placebo-controlled trials. Eur J Pain 2007. 11(2):125–138. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpain.2006.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cepeda MS, Camargo F, Zea C, Valencia L. Tramadol for osteoarthritis: a systematic review and metaanalysis. J Rheumatol. 2007;34(3):543–555. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Maetzel A, Makela M, Hawker G, Bombardier C. Osteoarthritis of the hip and knee and mechanical occupational exposure — a systematic overview of the evidence. J Rheumatol. 1997;24(8):1599–1607. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lievense A, Bierma-Zeinstra S, Verhagen A, et al. Influence of work on the development of osteoarthritis of the hip: a systematic review. J Rheumatol. 2001;28(11):2520–2528. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lievense AM, Bierma-Zeinstra SMA, Verhagen AP, et al. Influence of obesity on the development of osteoarthritis of the hip: a systematic review. Rheumatology. 2002;41(10):1155–1162. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/41.10.1155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lievense AM, Bierma-Zeinstra SMA, Verhagen AP, et al. Prognostic factors of progress of hip osteoarthritis: a systematic review. Arthritis Rheum. 2002;47(5):556–562. doi: 10.1002/art.10660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lievense AM, Bierma-Zeinstra SMA, Verhagen AP, et al. Influence of sporting activities on the development of osteoarthritis of the hip: a systematic review. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;49(2):228–236. doi: 10.1002/art.11012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lievense AM, Bierma-Zeinstra SMA, Verhagen AP, et al. Influence of hip dysplasia on the development of osteoarthritis of the hip. Ann Rheum Dis. 2004;63(6):621–626. doi: 10.1136/ard.2003.009860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Srikanth VK, Fryer JL, Zhai G, et al. A meta-analysis of sex differences prevalence, incidence and severity of osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2005;13(9):769–781. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2005.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Van Dijk GM, Dekker J, Veenhof C, van den Ende CHM. Carpa Study Group. Course of functional status and pain in osteoarthritis of the hip or knee: a systematic review of the literature. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;55(5):779–785. doi: 10.1002/art.22244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Vignon E, Valat J-P, Rossignol M, et al. Osteoarthritis of the knee and hip and activity: a systematic international review and synthesis (OASIS) Joint Bone Spine. 2006;73(4):442–455. doi: 10.1016/j.jbspin.2006.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Belo JN, Berger MY, Reijman M, et al. Prognostic factors of progression of osteoarthritis of the knee: a systematic review of observational studies. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;57(1):13–26. doi: 10.1002/art.22475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bedson J, Croft PR. The discordance between clinical and radiographic knee osteoarthritis: A systematic search and summary of the literature. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2008;9:116. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-9-116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Van Baar M. Effectiveness of exercise therapy in osteoarthritis of hip or knee. [Dutch] Geneeskd Sport. 1999;32:27–30. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Petrella RJ. Is exercise effective treatment for osteoarthritis of the knee? Br J Sports Med. 2000;34(5):326–431. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.34.5.326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fransen M, McConnell S, Bell M. Therapeutic exercise for people with osteoarthritis of the hip or knee. A systematic review. J Rheumatol. 2002;29(8):1737–1745. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Brosseau L, MacLeay L, Robinson V, et al. Intensity of exercise for the treatment of osteoarthritis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003;(2) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004259. CD004259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pelland L, Brosseau L, Wells G, et al. Efficacy of strengthening exercises for osteoarthritis (part I): a meta analysis. Phys Ther Rev. 2004;9:77–108. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Roddy E, Zhang W, Doherty M. Aerobic walking or strengthening exercise for osteoarthritis of the knee? A systematic review. Ann Rheum Dis. 2005;64(4):544–548. doi: 10.1136/ard.2004.028746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Walsh NE, Mitchell HL, Reeves BC, Hurley MV. Integrated exercise and self-management programmes in osteoarthritis of the hip and knee: a systematic review of effectiveness. Phys Ther Rev. 2006;11:289–297. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Devos-Comby L, Cronan T, Roesch SC. Do exercise and self- management intervention benefit patients with osteoarthritis of the knee. A meta-analytic review. J Rheumatol. 2006;33(4):744–756. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Aggarwal A, Sempowski IP. Hyaluronic acid injections for knee osteoarthritis. Systematic review of the literature. Can Fam Physician. 2004;50:249–256. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Arroll B, Goodyear-Smith F. Corticosteroid injections for osteoarthritis of the knee: meta-analysis. BMJ. 2004;328(7444):869. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38039.573970.7C. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Godwin M, Dawes M. Intra-articular steroid injections for painful knees. Systematic review with meta-analysis. Can Fam Physician. 2004;50:241–248. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wang C-T, Lin J, Chang C-J, et al. Therapeutic effects of hyaluronic acid on osteoarthritis of the knee. A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2004;86–A(3):538–545. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200403000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Arrich J, Piribauer F, Mad P, et al. Intra-articular hyaluronic acid for the treatment of osteoarthritis of the knee: systematic review and meta-analysis. Can Med Assoc J. 2005;172:1039–1043. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.1041203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bellamy N, Campbell J, Robinson V, et al. Viscosupplementation for the treatment of osteoarthritis of the knee. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;(2) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005321.pub2. CD005321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bellamy N, Campbell J, Robinson V, et al. Intra-articular corticosteroid for treatment of osteoarthritis of the knee. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;(2) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005321.pub2. CD005328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Brosseau L, Welch V, Wells G, et al. Low level laser therapy for osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis: a meta-analysis. J Rheumatol. 2000;27(8):1961–1969. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Osiri M, Welch V, Brosseau L, et al. Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation for knee osteoarthritis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2000;(4) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002823. CD002823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Robinson VA, Brosseau L, Peterson J, et al. Therapeutic ultrasound for osteoarthritis of the knee. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2001;(3) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003132. CD003132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Brosseau L, Macleay L, Robinson V, et al. Efficacy of balneotherapy for osteoarthritis of the knee: a systematic review. Phys Ther Rev. 2002;7:209–222. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Brosseau L, Yonge KA, Robinson V, et al. Thermotherapy for treatment of osteoarthritis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003;(4) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004522. CD004522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.McCarthy CJ, Callaghan MJ, Oldham JA. Pulsed electromagnetic energy treatment offers no clinical benefit in reducing the pain of knee osteoarthritis: a systematic review. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2006;7:51. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-7-51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.McAlindon TE, LaValley MP, Gulin JP, Felson DT. Glucosamine and chondroitin for treatment of osteoarthritis: A systematic quality assessment and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2000;283(11):1469–1475. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.11.1469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Richy F, Bruyere O, Ethgen O, et al. Structural and symptomatic efficacy of glucosamine and chondroitin in knee osteoarthritis: a comprehensive meta-analysis. Arch Int Med. 2003;163(13):1514–1522. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.13.1514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Poolsup N, Suthisisang C, Channark P, Kittikulsuth W. Glucosamine long-term treatment and the progression of knee osteoarthritis: systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Annals Pharmacother. 2005;39(6):1080–1087. doi: 10.1345/aph.1E576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Towheed TE, Maxwell L, Anastassiades TP, et al. Glucosamine therapy for treating osteoarthritis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;(2) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002946.pub2. CD002946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Reichenbach S, Sterchi R, Scherer M, et al. Meta-analysis: chondroitin for osteoarthritis of the knee or hip. Ann Intern Med. 2007;146(8):580–590. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-146-8-200704170-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Rintelen B, Neumann K, Leeb BF. A meta-analysis of controlled clinical studies with diacerein in the treatment of osteoarthritis. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(17):1899–1906. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.17.1899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Long L, Soeken K, Ernst E. Herbal medicines for the treatment of osteoarthritis: a systematic review. Rheumatology. 2001;40(7):779–793. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/40.7.779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Ernst E. Avocado-soybean unsaponifiables (ASU) for osteoarthritis — a systematic review. Clin Rheumatol. 2003;22(4–5):285–288. doi: 10.1007/s10067-003-0731-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Little CV, Parsons T, Logan S. Herbal therapy for treating osteoarthritis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2000;(4) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002947. CD002947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.White A, Foster NE, Cummings M, Barlas P. Acupuncture treatment for chronic knee paa systematic review. Rheumatology. 2007;46(3):384–390. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kel413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Brouwer RW, Jakma TSC, Verhagen AP, et al. Braces and orthoses for treating osteoarthritis of the knee. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;(1) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004020.pub2. CD004020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Reilly KA, Barker KL, Shamley D. A systematic review of lateral wedge orthotics — how useful are they in the management of medial compartment osteoarthritis? Knee. 2006;13(3):177–183. doi: 10.1016/j.knee.2006.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Christensen R, Bartels EM, Astrup A, Bliddal H. Effect of weight reduction in obese patients diagnosed with knee osteoarthritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2007;66(4):433–439. doi: 10.1136/ard.2006.065904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Philadelphia Panel. Philadelphia Panel evidence-based clinical practice guidelines on selected rehabilitation interventions for knee pain. Phys Ther. 2001;81(10):1675–1700. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Jordan KM, Arden NK, Doherty M, et al. EULAR recommendations 2003: an evidence based approach to the management of knee osteoarthritis: report of a Task Force of the Standing Committee for International Clinical Studies Including Therapeutic Trials (ESCISIT) Ann Rheum Dis. 2003;62(12):1145–1155. doi: 10.1136/ard.2003.011742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Ottawa P. Ottawa panel evidence-based clinical practice guidelines for therapeutic exercises and manual therapy in the management of osteoarthritis. Phys Ther. 2005;85(9):907–971. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Ministry of Health. Osteoarthritis of the knee. Clinical practice guideline 4/2007. Singapore: Ministry of Health; [Google Scholar]

- 86.Williams NH, Amoakwa EN, Burton K, et al. The hip and knee book: helping you cope with osteoarthritis. London: The Stationery Office; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 87.Flesch R. A new readability yardstick. J Appl Psychol. 1948;32(3):221–233. doi: 10.1037/h0057532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Kincaid JP, Fishburne RP Jr, Rogers RL, Chissom BS. Derivation of new readability formulas for Navy enlisted personnel. Research Branch Report 8–75. Millington, TN: Naval Technical Training, US Naval Air Station, Memphis TN; 1975. [Google Scholar]

- 89.McClune T, Burton AK, Waddell G. Whiplash associated disorders: a review of the literature to guide patient information and advice. Emerg Med. 2002;19:499–506. doi: 10.1136/emj.19.6.499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Williams NH, Amoakura EN, Burton K, et al. Activity Increase Despite Arthritis (AIDA): design of a phase II randomised controlled trial evaluating an active management booklet for hip and knee osteoarthritis [ISRCTN24554946] BMC Fam Pract. 2009;10:62. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-10-62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]