Abstract

Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II (CaMKII) phosphorylates the β2a subunit of voltage-gated Ca2+ channels at Thr498 to facilitate cardiac L-type Ca2+ channels. CaMKII colocalizes with β2a in cardiomyocytes and also binds to a domain in β2a that contains Thr498 and exhibits amino acid sequence similarity to the CaMKII autoinhibitory domain and to a CaMKII binding domain in the NMDA receptor NR2B subunit (Grueter et al., 2006. Mol. Cell 23:641). Here we explore the selectivity of the actions of CaMKII among Ca2+ channel β subunit isoforms. CaMKII phosphorylates the β1b, β2a, β3 and β4 isoforms with similar initial rates and final stoichiometries of 6–12 mole phosphate per mole protein. However, activated/autophosphorylated CaMKII binds to β1b and β2a with similar apparent affinity, but does not bind to β3 or β4. Pre-phosphorylation of β1b and β2a by CaMKII substantially reduces the binding of autophosphorylated CaMKII. Residues surrounding Thr498 in β2a are highly conserved in β1b, but are different in β3 and β4. Site-directed mutagenesis of this domain in β2a showed that Thr498 phosphorylation promotes dissociation of CaMKII-β2a complexes in vitro and reduces interactions of CaMKII with β2a in cells. Mutagenesis of Leu493 to Ala substantially reduces CaMKII binding in vitro and in intact cells but does not interfere with β2a phosphorylation at Thr498. In combination, these data show that phosphorylation dynamically regulates the interactions of specific isoforms of the VGCC β subunits with CaMKII.

Voltage-gated Ca2+ channel (VGCC) ion selectivity and responsiveness to pharmacological antagonist ligands are defined by the identity of the pore forming α1 subunit. The biophysical properties are generally modified by differential association of auxiliary β, α2δ and γ subunits (1–3). Four genes encoding β isoforms have been identified (β1–4) each having multiple mRNA splice variants, which differentially modulate the properties and cell surface expression of VGCC complexes (4–6). In addition, VGCC complexes are further modulated by a variety of posttranslational modifications.

The regulatory properties of Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II (CaMKII) allow integration of signals conveyed by changes in the frequency, duration and amplitude of intracellular Ca2+ transients (7). This feature critically depends on Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent autophosphorylation of Thr286 in CaMKIIα (or Thr287 in other CaMKII isoforms) in the autoregulatory domain, which confers subsequent autonomous kinase activity (reviewed in (8, 9, 10 )). Thus, Ca2+ transients induce more prolonged kinase activation depending on specific parameters of Ca2+ signals in the local environment. Recent studies demonstrated that localization of CaMKII to specific subcellular microdomains confers distinct downstream phosphorylation events (11, 12). These studies are consistent with the emerging concept that direct interactions of signaling molecules ensures accurate and timely responses to cell stimulation (13, 14). Determining the mechanisms for CaMKII binding to target proteins, such as VGCCs, is thus an important goal for understanding the role of CaMKII in excitable cells.

CaMKII phosphorylates the α and/or β subunits of a variety of VGCCs to modulate Ca2+ entry. For example, CaMKII regulates T-type Ca2+ channels by binding to and phosphorylating the II-III intracellular loop in the CaV3.2 α subunit (15, 16). The EF hand motif in the C-terminal domain of the L-type Ca2+ channel (LTCC) CaV1.3 α subunit is also phosphorylated by CaMKII, causing a negative voltage shift in LTCC current activation (17). CaMKII also phosphorylates multiple sites in the LTCC CaV1.2 α1c subunit to promote both Ca2+- and voltage-dependent facilitation in heterologous cells (18–20). In addition to these roles in feedback regulation, CaMKII is involved in crosstalk between Ca2+ channels: for example, LTCC activation leads to depression of R-type Ca2+ channels in dendritic spines via a poorly defined CaMKII-dependent mechanism (21).

We recently showed that CaMKII-dependent facilitation of cardiac CaV1.2 LTCCs is mediated by phosphorylation of the β2a subunit at Thr498 in cardiomyocytes (22). Moreover, β2a acts as a CaMKII associated protein (CaMKAP) that directly interacts with CaMKII in vitro and in intact cells. Our findings showed that VGCC regulation may be strongly enhanced or modified by association of CaMKII with the β2a subunit. In the current study, we demonstrate that CaMKII phosphorylates all of the β subunit isoforms, but interacts with β subunits in an isoform specific manner; this CaMKII-β subunit interaction is negatively modulated by phosphorylation of the β subunit.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Generation of plasmid constructs

The open reading frames of the rat VGCC β1b, β2a, β3 and β4 subunits (Accession Numbers X61394, M80545, M88751 and L02315) (generous gifts from Dr. E. Perez-Reyes, University of Virginia), were amplified by PCR and ligated into pGEX-4T1 (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech). The β2a subunit was also subcloned into pFLAG-CMV-2 (Sigma-Aldrich), pIRES (Clontech), and pLenti (Invitrogen). Murine CaMKIIα and rat CaMKIIδ coding sequences were inserted into pcDNA3. The cDNAs encoding β2a were mutated essentially as described in the QuikChange kit (Stratagene). The pcDNA plasmid encoding a constitutively active T287D mutation of myc-CaMKIIδ 2 was a generous gift from Dr. E. Olson (UTSW, Dallas).

GST fusion protein expression and purification

GST fusion proteins were expressed and purified as described in (22). Protein concentrations were determined by Bradford assay (BioRad) using bovine serum albumin as standard and confirmed by resolving proteins on SDS-polyacrylamide gels followed by Coomassie-Blue staining.

CaMKII purification and autophosphorylation

Recombinant rat CaMKIIδ2 or mouse CaMKIIα purified from baculovirus-infected Sf9 insect cells were autophosphorylated at Thr287 or Thr286, respectively, using ATP or [γ-32P]ATP, essentially as described previously (23).

CaMKII plate binding assays

GST fusion proteins in 0.2 ml plate-binding buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 200 mM NaCl, 0.1 mM EDTA, 5 mM 2-mercaptoethanol, 0.1% (v/v) Tween-20, 5 mg/ml bovine serum albumin) were incubated for 18–24 hours at 4°C in glutathione-coated wells. After 3 washes with buffer, wells were incubated at 4°C with the indicated concentrations of 32P-labeled, Thr287 autophosphorylated CaMKIIδ (0.2 ml) for 2 hours then washed (8 times, 0.2 ml ice-cold buffer). The bound kinase was quantified using a scintillation counter.

In order to monitor dissociation of preformed CaMKII-β2a complexes, GST-β2a (WT or T498A: ≈5 pmol) was immobilized in glutathione-coated multi-well plates (Pierce, Rockford, IL) and then incubated for 2 hours at 4°C with [32P-T286]CaMKIIα (0.25 µM) in binding buffer. Wells were rinsed 8 times in binding buffer and immobilized complexes were then incubated with 50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 0.1 M NaCl, 0.25 mg/ml bovine serum albumin, 0.1% Triton X-100, 1 mM dithiothreitol, 10 mM magnesium acetate, with or without 0.5mM ATP. Soluble/dissociated CaMKII was removed from the wells at the indicated times and quantified by scintillation counting.

CaMKII gel overlays

GST fusion proteins (50 pmoles) were resolved by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and transferred to nitrocellulose. Approximately equal protein loading was confirmed by staining membranes using Ponceau S. Membranes were blocked and then incubated for 2 hours at 4°C with 32P-labeled, Thr287 autophosphorylated CaMKIIδ2 (100 nM), essentially as described (24). After washing, bound CaMKII was quantified using a phosphoimager.

CaMKII phosphorylation of GST-β subunits

Purified GST-β subunits (or GST alone as a blank) were incubated at either 30°C or 4°C in 50 mM HEPES, pH 7.5, 10 mM magnesium acetate, 1 mg/ml bovine serum albumin, 1 mM dithiothreitol, 0.4 mM [γ-32]ATP (≈ 500 cpm/pmol) or 0.4 mM ATP containing purified CaMKII. At the indicated times aliquots were spotted on P81 phosphocellulose papers, washed in water and counted in a scintillation counter to measure the stoichiometry of phosphorylation. Parallel aliquots were resolved by SDS-polyacrylamide gel analysis, and dried gels were analyzed by autoradiography and/or a phosphoimager followed by densitometry, as described (22).

Immunoblotting

Samples were resolved on Tris-Glycine SDS-polyacrylamide gels and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes using standard methods. Membranes were blocked in 5% (w/v) milk in TTBS (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5; 0.2 M NaCl, 0.1% (v/v) Tween-20), then incubated with primary antibodies overnight at 4°C. After washing six times for >5 minutes each, membranes were incubated for one hour at room temperature with horseradish peroxidase conjugated secondary antibody. The washed membranes were developed using enhanced chemiluminescence.

Co-immunoprecipitations from HEK293 cells

Experiments were performed as described in (22). Briefly, HEK293FT cells were transfected with FLAG-β2a (WT, T498A, T498E or L493A), myc-CaMKIIδ (T287D), and/or flag vector alone. Cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with FLAG-coated agarose beads (40 µl: Sigma) and then immunoblotted (see above).

Statistics

Data are expressed as mean±sem. Paired comparisons were performed using the Student’s t-test. Multiple group comparisons were performed using 1-way or 2-way ANOVA with Bonferoni post-hoc testing, unless otherwise noted. The null hypothesis was rejected if p<0.05.

RESULTS

CaMKII efficiently phosphorylates β1–4 subunits

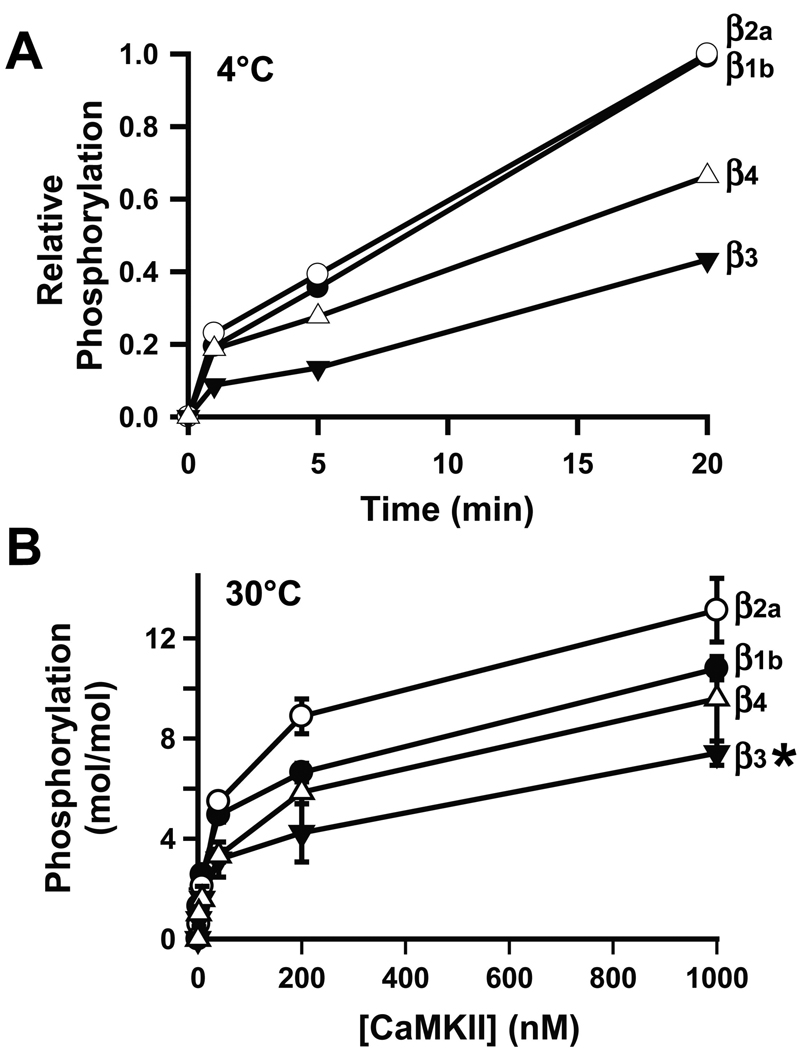

The highly efficient phosphorylation of the β2a subunit at Thr498 by CaMKII is critical for CaMKII effects on cardiac LTCCs (22). In order to begin to analyze potential effects of CaMKII on the other β isoforms, we assessed the phosphorylation of full-length β subunit isoforms that had been expressed in bacteria as GST fusion proteins. First, incubations were performed at 4°C in order to provide an indication of the initial rate of phosphorylation by 10 nM CaMKII (Fig. 1A). Under these conditions CaMKII preferentially phosphorylatesThr498 in GST-β2a (22). All four isoforms were phosphorylated, although β1b and β2a were phosphorylated at a relative rate ≈2.5 fold faster than for β3 or β4. We then assessed the extent of phosphorylation by various concentrations of CaMKII using a fixed concentration of the GST-β isoforms (1 µM). We previously identified 6 CaMKII phosphorylation sites in β2a that had been phosphorylated to a stoichiometry of ≈ 3 mol/mol (22). In the present studies, each isoform was phosphorylated with a similar CaMKII concentration-dependence (Fig. 1B), with the β2a, β1b, β3 and β4 variants attaining stoichiometries of 13.1±1.3, 10.8±0.4, 7.4±0.5 and 9.6±1.7 moles of phosphate/mole β, respectively. While ANOVA detected significant variability in the final phosphorylation stoichiometries (p=0.038), post-hoc testing revealed a single significant difference between β3 and β2a phosphorylation stoichiometries (p<0.05). In combination, these data show that these four β subunit isoforms are rapidly phosphorylated by CaMKII to a high stoichiometry in vitro with relatively modest differences in the phosphorylation parameters that were measured.

Figure 1. CaMKII efficiently phosphorylates all of the β subunit isoforms in vitro.

A. Initial rate of phosphorylation of GST-β isoforms by CaMKIIδ2 at 4°C. Data (mean of 2 experiments) are plotted relative to the phosphorylation of GST-β2a after 20 min. GST-β2a, ○. GST-β1b, ●. GST-β3, ▼. GST-β4, △. B. Stoichiometry of phosphorylation of GST-β isoforms by increasing concentrations of CaMKIIδ2 after 20 minutes incubation at 30°C (mean±sem of 3 experiments). Symbols as in panel A. *: phosphorylation of GST-β3 by 1000 nM CaMKII was significantly less than that of GST-β2a (p<0.05). Other differences were not statistically significant.

Selective interactions of CaMKII with VGCC β subunits in vitro

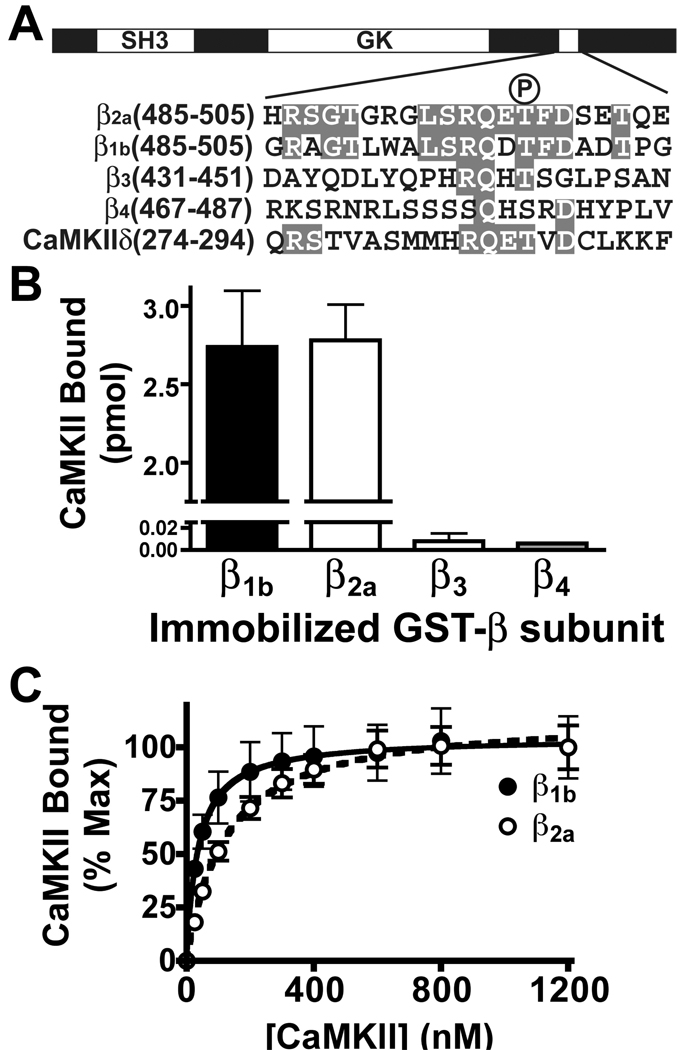

Thr498 of the β2a variant lies within a CaMKII-binding domain that is C-terminal to the SH3 and GK domains (Fig. 2A). Alignment of the amino acid sequence of the domain surrounding Thr498 in β2a with other β subunit isoforms revealed variable conservation. A CaMKII consensus phosphorylation motif LXRXXS/T (25) is present in both β2a and β1b and there is additional amino acid sequence similarity outside this motif, but key residues from this motif are missing in β3 and β4. Based on these alignments, we hypothesized that CaMKII would bind to β1b in a similar manner to its interaction with β2a, but not to β3 or β4. To test this hypothesis we immobilized GST-β fusion proteins in glutathione coated 96-well plates and then incubated them with various concentrations of purified [32P]-autophosphorylated CaMKII. In an initial experiment, the binding of CaMKII to GST-β1b was indistinguishable from the binding to GST-β2a, but binding to GST-β3 and GST-β4 was <1% of the binding to GST-β2a (Fig. 2B). Binding of Thr286-autophosphorylated CaMKII to both GST-β1b and GST-β2a was concentration dependent and saturable (Fig. 2C). GST-β1b exhibited a significantly higher apparent affinity for CaMKII than did GST-β2a (apparent Kd's 35±12 and 120±21 nM CaMKII subunit, respectively. n=4. p<0.01). GST-β3 and GST-β4 failed to bind significant amounts of the kinase even at a concentration of 1200 nM CaMKII subunit (data not shown). Autophosphorylated CaMKII also binds to GST-β1b and GST-β2a, but not to GST-β3 and GST-β4 in glutathione agarose cosedimentation assays, but there was no significant binding of nonphosphorylated CaMKII to any GST-β subunit isoforms (Supplementary Fig. 1). Thus, CaMKII does not appear to bind significantly to the β3 and β4 isoforms, but interacts with the β1b isoform with an ≈3-fold higher affinity than with β2a following activation by Thr286/7 autophosphorylation.

Figure 2. CaMKII association with VGCC β subunit isoforms.

A. Schematic domain structure of the β2a subunit showing SH3 and guanylate kinase-like (GK) domains, with the C-terminal CaMKII-binding domain containing the Thr498 phosphorylation site (indicated by the “P”). The amino acid sequence of the CaMKII binding domain in β2a is aligned with similar sequences from other β isoforms and the CaMKIIδautoregulatory domain (surrounding Thr287): identical residues are shown in gray boxes. B. GST-β subunit isoforms were immobilized in glutathione-coated multi-well plates (100 pmol/well) and incubated with 32P-labeled Thr287 autophosphorylated CaMKIIδ2 (50 nM subunit). C. Concentration dependent binding of Thr287 autophosphorylated CaMKIIδ2 to GST-β2a (○) and GST-β1b (●) in glutathione-coated multi-well plates. Both panels B and C plot binding as mean±sem from 4 observations (β2a and β1b) or the mean of 2 observations (β3 and β4).

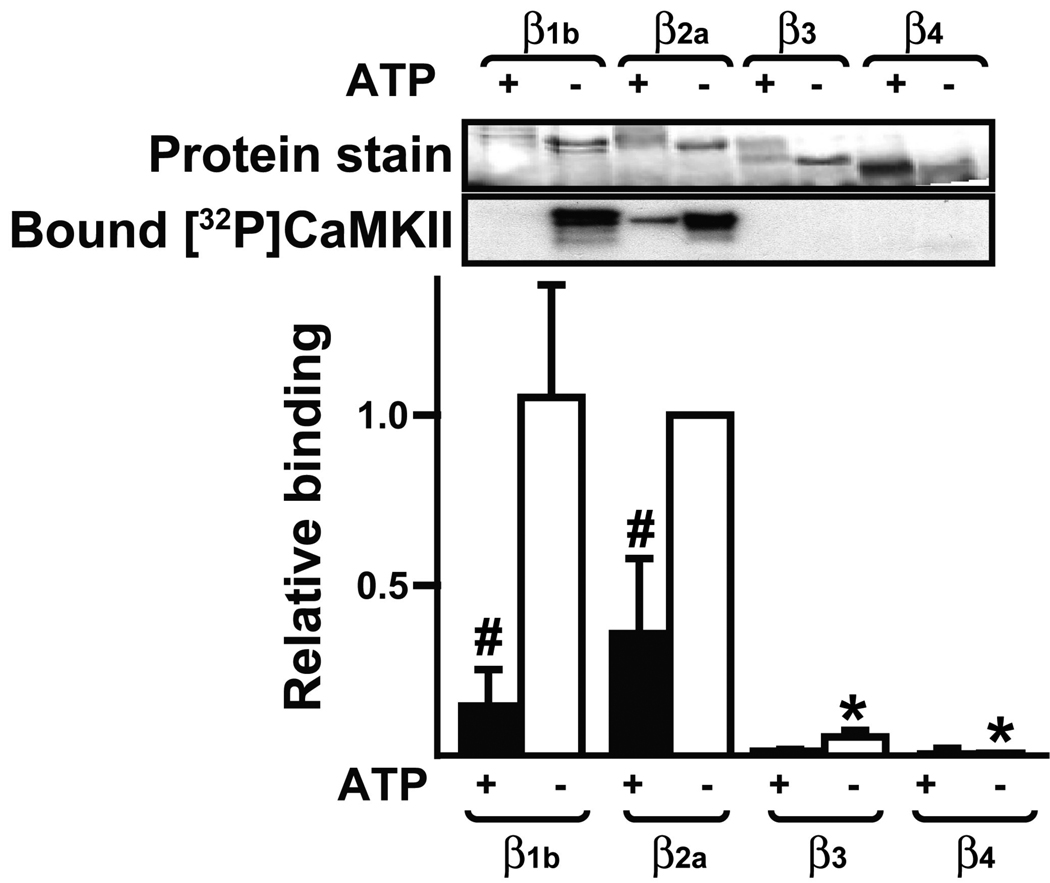

Interaction with CaMKII is modulated by phosphorylation in vitro

Thr498 and several additional serine and threonine residues lie within the CaMKII binding domain of β2a, suggesting that the interaction with CaMKII may be modulated by phosphorylation. Therefore, GST-β isoforms were preincubated with activated CaMKII in the presence or absence of ATP and then separated from reaction components by SDS-PAGE. The electrophoretic mobility of each GST-β isoform was reduced following preincubation with ATP and CaMKII (Fig. 3: protein stain), consistent with the relatively high phosphorylation stoichiometry under these conditions (c.f., Fig. 1B). An overlay assay was then used to assess the binding of 32P-autophosphorylated CaMKII. Non-phosphorylated GST-β1b and GST-β2a proteins bound substantial, but comparable, amounts of CaMKII (Fig. 3). Pre-phosphorylation significantly reduced CaMKII binding to both proteins by 70–80%. No significant interactions were seen between CaMKII and either GST-β3 or GST-β4, whether or not these protein were pre-phosphorylated. In combination, these data suggest that phosphorylation of the β subunit by CaMKII modulates the binding of CaMKII to the β1b and β2a isoforms.

Figure 3. Prephosphorylation of GST-β2a and GST-β1b inhibits CaMKII binding.

GST-β isoforms were preincubated with activated CaMKIIδ2 in the presence or absence of ATP, as indicated. Reactions were resolved by SDS-PAGE and transferred to nitrocellulose membrane for overlay with [32P]-labeled Thr287-autophosphorylated CaMKIIδ2. The top panel shows a protein stain of the membrane prior to overlay and a representative autoradiograph to detect bound CaMKII. Binding was quantified using a phosphoimager and normalized to the binding detected using non-phosphorylated GST-β2a: the mean±sem from 3 experiments is plotted. Data were analyzed by 2-way ANOVA: *: p<0.001 vs. binding to non-phosphorylated GST-β2a. #: p<0.05 vs. binding to the corresponding non-phosphorylated protein.

The mechanism of CaMKII binding to β2a

In order to dissect the mechanism for CaMKII binding we assessed the effect of mutating residues within the CaMKII binding domain of β2a on the interaction with CaMKII. Mutation of Thr498 to Ala or Glu prevented or mimicked phosphorylation at this site, respectively (see above). In addition, residues homologous to Leu493 at the p-5 position relative to Thr498 in β2a and β1b are conserved in other high affinity CaMKII phosphorylation sites that form stable complexes with the CaMKII catalytic domain prior to phosphorylation (e.g., Ser1303 in NR2B and Thr286/7 in CaMKIIα/δ). However, hydrophobic residues at the p-5 position are not conserved in β3 or β4, and are not generally considered to be part of the minimal consensus phosphorylation site (25). Therefore, we also mutated Leu493 to Ala. Binding of 32P-autophosphorylated CaMKII to GST-β2a in glutathione coated multi-well plates was unaffected by the T498A mutation, whereas the T498E and L493A mutations significantly reduced CaMKII binding by >90% (Table 1). These data demonstrate that the region surrounding Thr498 is critical for stable binding of Thr286-autophosphorylated CaMKII to the full-length β2a isoform.

Table 1. Disruption of CaMKII binding to GST-β2a by site-directed mutagenesis.

Purified GST-β2a proteins (wild type or with the indicated point mutations) or GST alone were immobilized in a glutathione-coated 96-well plate (100 pmol/well) and then incubated with 32P-labeled Thr287-autophosphorylated CaMKIIδ2 (100 nM subunit). After washing, bound CaMKII was quantified by scintillation counting. The data indicate the mean±sem (n = 3 experiments).

| GST-β2a Protein | CaMKII bound |

|---|---|

| (pmol subunit) | |

| Wild type | 7.9 ± 0.3 |

| T498A | 6.2 ± 0.8 |

| T498E | 0.51 ± 0.16 |

| L493A | 0.14 ± 0.03 |

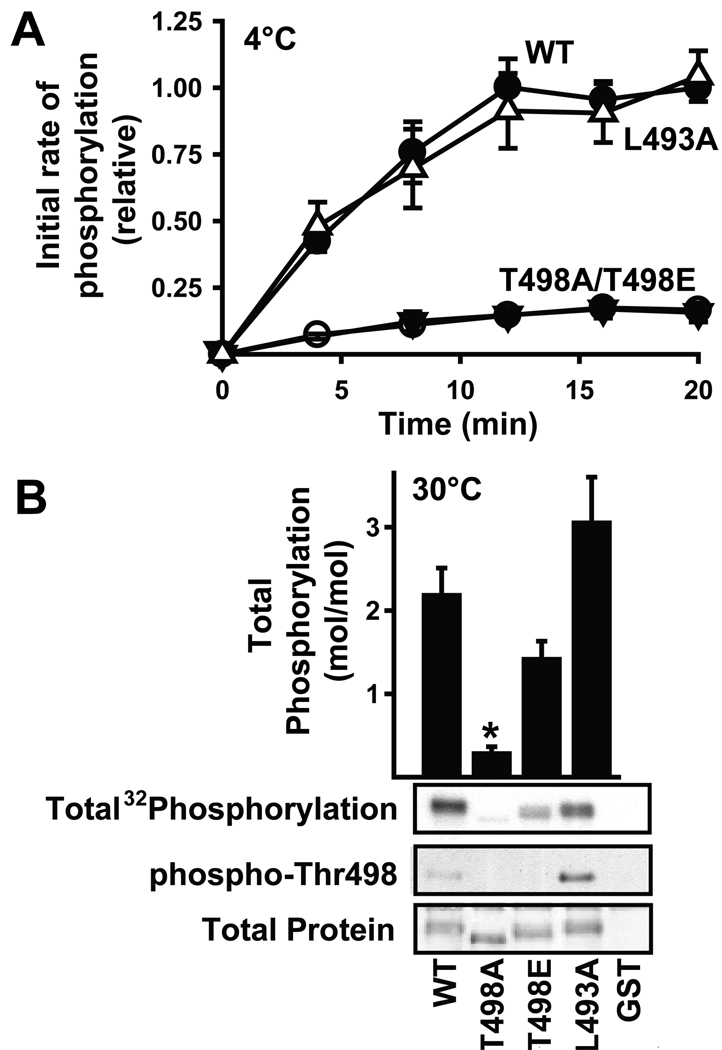

Disruption of CaMKII binding does not affect phosphorylation of β2a in vitro

We then explored the effects of the Thr498 and Leu493 mutations on CaMKII phosphorylation of the β2a subunit. The T498A mutation substantially reduced the rate of β2a phosphorylation at 4°C, as shown previously, and T498E mutation had a very similar effect. Interestingly, the rate of L493A-β2a phosphorylation by CaMKII was indistinguishable from the rate of phosphorylation of the wild type protein (Fig. 4A), even though the L493A mutation interfered with CaMKII binding. When incubations were conducted at 30°C, CaMKII (10 nM) phosphorylated wild type β2a to a stoichiometry of 2.2 mol/mol, consistent with stoichiometries reported in Fig. 1B using 10 nM CaMKII, but T498A mutation reduced phosphorylation to 0.3 mol/mol (Fig. 4B). In contrast, T498E and L493A mutations had no significant effect on the stoichiometry of CaMKII phosphorylation, although there was a trend for reduced phosphorylation of T498E-β2a. These data show that two mutations that severely compromise stable binding of activated CaMKII to β2a have no significant effect on the overall stoichiometry of CaMKII phosphorylation in vitro.

Figure 4. Phosphorylation of GST-β2a by CaMKII is independent of stable binding.

A. Initial rate for phosphorylation of GST-β2a (wild type, ●: T498A,▼: T498E,○: L493A, △ ) by CaMKII (10 nM) at 4°C. Data are the mean±sem of 3–4 observations normalized to the phosphorylation of the wild-type protein after 20 minutes. B. Wild type or mutated GST-β2a proteins or GST alone were incubated for 20 min at 30°C with activated CaMKII (10 nM) and [γ-32P]ATP. Aliquots of the reactions were resolved by SDS-PAGE and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. Membranes were stained for total protein (bottom), and then immunoblotted using a phospho-specific antibody that was raised to phospho-Thr286 in CaMKIIα, but also detects phospho-Thr498 in β2a (middle). Total phosphorylation of β2a was detected by autoradiography (top gel). The stoichiometry of total phosphorylation (bar graph) was estimated after spotting parallel aliquots on phosphocellulose papers (see Methods). Data are plotted as mean±sem (n=4 experiments). *: p<0.01 vs. WT.

As noted above, Leu493 is part of a conserved sequence surrounding high-affinity phosphorylation sites in multiple CaMKII-binding proteins. In order to determine whether L493A mutation altered the phosphorylation site specificity of CaMKII, we exploited similarities in protein sequences surrounding Thr498 in β2a and Thr287 in CaMKIIδ (Fig. 2A). Commercially available phospho-Thr287 antibodies detected the β2a subunit following CaMKII phosphorylation, but not nonphosphorylated β2a (Fig. 4B and data not shown). Phospho-Thr286/7 antibodies only weakly detected phosphorylated β1b and failed to detect β3 or β4 before or after CaMKII phosphorylation (data not shown). Analysis of mutated β2a proteins revealed that T498A-β2a and T498E-β2a could not be detected (Fig. 4B, middle blot), demonstrating that the antibody specifically recognized phospho-Thr498 in β2a, in addition to the Thr286/287 autophosphorylation site in CaMKII. The lack of antibody cross-reactivity with T498E-β2a is not surprising given differences in size and charge density between glutamate and phospho-threonine. Taken together, these findings validate the use of this antibody to report the phosphorylation status of Thr498 in the CaMKII binding domain of β2a. Notably, Thr498 was phosphorylated to a similar extent in L493A-β2a and wild type β2a (Fig. 4B, inset). Thus, L493A mutation does not appear to significantly alter the ability of CaMKII to phosphorylate Thr498 in vitro.

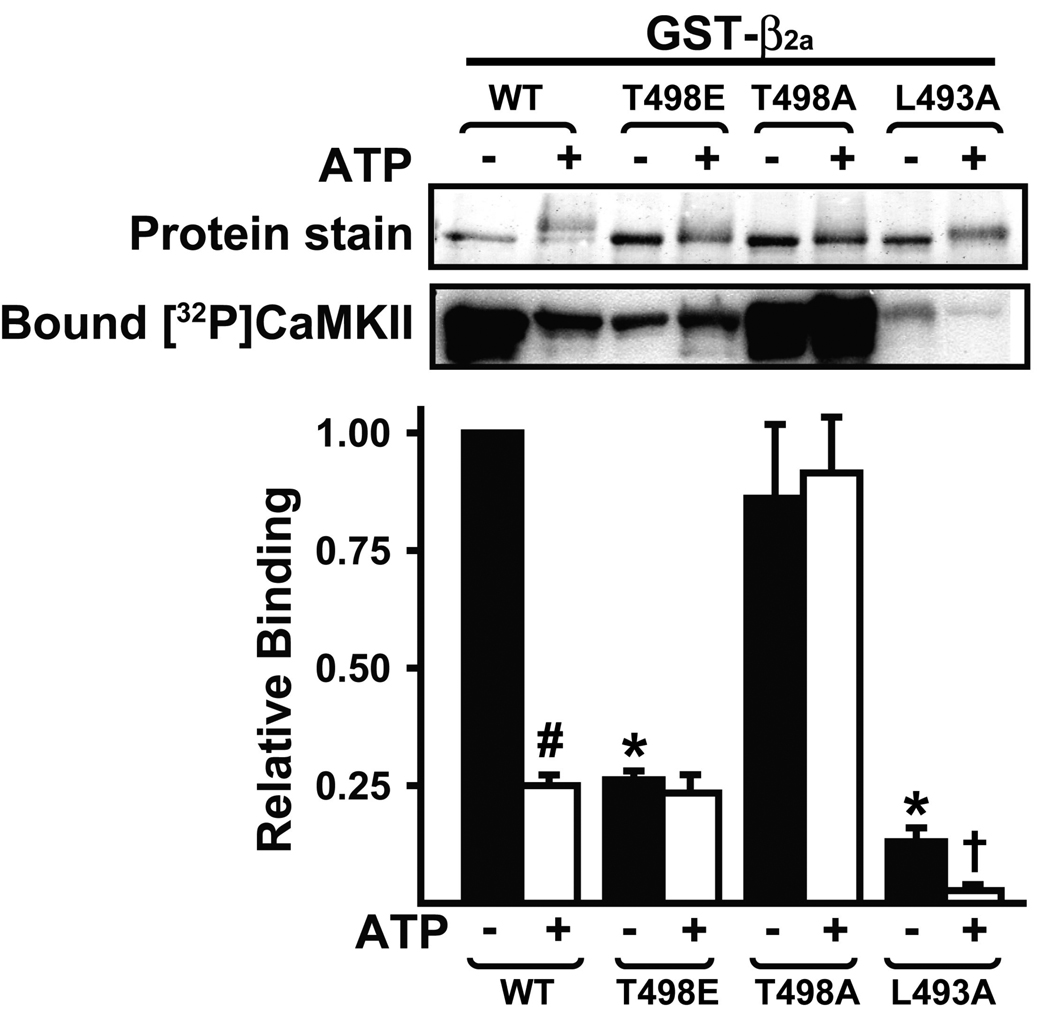

Phosphorylation at Thr498 disrupts CaMKII binding

In order to explore the mechanism by which phosphorylation of β2a by CaMKII interferes with subsequent binding of activated CaMKII, we pre-phosphorylated wild type and mutated β2a proteins and analyzed CaMKII binding using overlay assays. As seen using the glutathione plate-binding assay, T498A-β2a bound comparable amounts of activated CaMKII to wild type β2a. However, pre-phosphorylation of T498A-β2a had no significant effect on binding of activated CaMKII, whereas pre-phosphorylation of wild type β2a significantly reduced binding by ≈80% in these assays. The T498E mutation reduced CaMKII binding by ≈80% and CaMKII phosphorylation had no significant additional effect on binding to T498E-β2a. Interestingly, L493A mutation significantly reduced binding by ≈90% in these assays, and pre-phosphorylation by CaMKII resulted in an additional significant decrease in binding. Taken together, these data suggest that pre-phosphorylation of β2a at Thr498 substantially reduces the association of CaMKII.

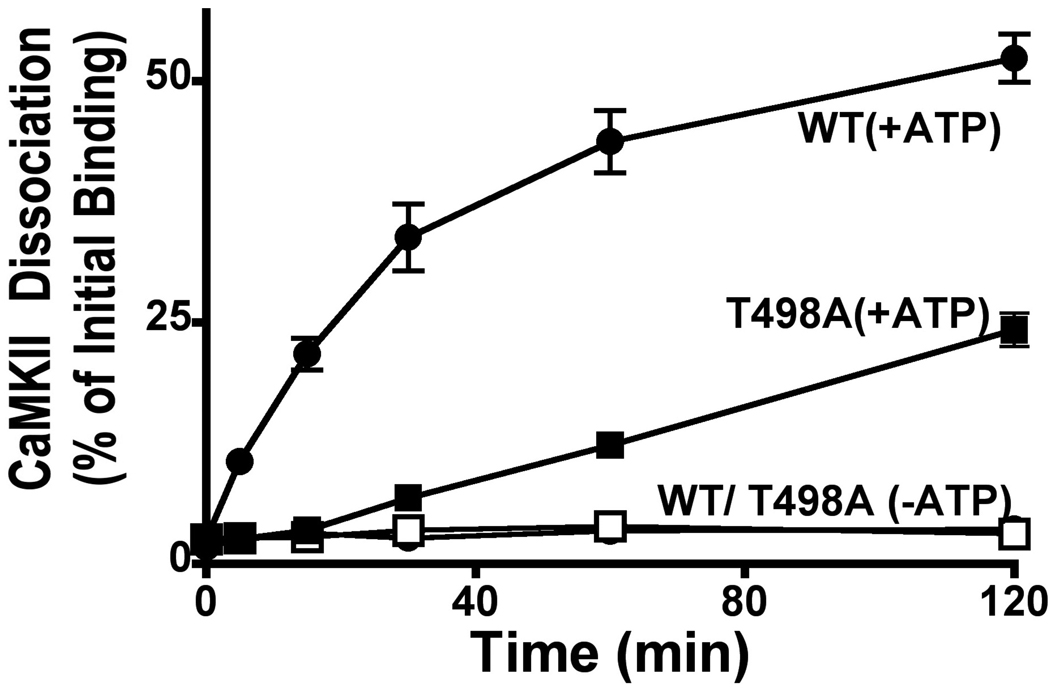

We also investigated the role of Thr498 phosphorylation in the context of preformed CaMKII-β2a complexes. Complexes of autonomously-active Thr286 autophosphorylated CaMKII bound to GST-β2a(WT) were isolated in glutathione-coated multi-well plates and then incubated with or without addition of ATP. Addition of ATP to these complexes induced phosphorylation at Thr498 and several other sites, as reflected by immunoblotting with phospho-Thr286 CaMKII antibodies and by a substantial reduction in the electrophoretic mobility of GST-β2a (data not shown). In the absence of ATP, CaMKII complexes with WT β2a were remarkably stable (<5% dissociation over a 2 hour incubation), but addition of ATP induced dissociation of ≈50% of bound CaMKII. T498A mutation of β2a had little effect on the stability of complexes with CaMKII in the absence of ATP, but substantially reduced the rate and extent of dissociation following addition of ATP as compared to WT β2a (Fig. 6). However, ATP still enhanced dissociation of CaMKII from preformed complexes with T498A-β2a (≈20% of in 2 hours), suggesting that phosphorylation at other residues in β2a and/or CaMKII may have a modest effect on the stability of these complexes, at least in vitro. In combination, these data suggest that phosphorylation of β2a at Thr498 enhances the dissociation of CaMKII from preformed complexes with β2a in vitro.

Figure 6. Phosphorylation of β2a at Thr498 enhances dissociation of the CaMKII-β2a complex.

Complexes of GST-β2a (WT or T498A) and [32P-T286]CaMKIIα in glutathione-coated multi-well plates were incubated with or without ATP in a dissociation buffer (see Methods). At the indicated times, dissociated [32P-T286]CaMKIIα was removed from wells and quantified by scintillation counting. Data points represent mean±sem (n=3) (n=2 for β2a T498A in absence of ATP): error bars lie within symbols of some data points.

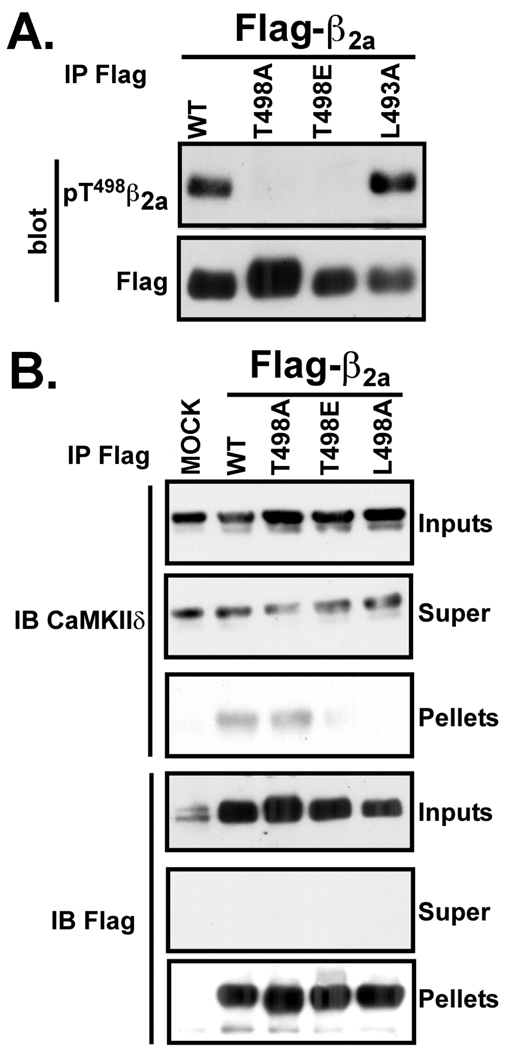

CaMKII interaction with β2a is regulated in cells

Initially, we explored whether Thr498 in β2a is phosphorylated in intact cells. Lysates of HEK293 cells expressing FLAG-β2a (wild type or mutated) with a constitutively active CaMKIIδ2 mutant were immunoprecipitated using FLAG antibodies. Blotting the immune complexes with FLAG antibodies revealed a relatively consistent expression and immunoprecipitation of the β2a proteins. The phospho-Thr286 CaMKIIα antibodies detected the β2a wild type and L493A mutant, but not T498A- or T498E-β2a proteins (Fig. 6A). These data show that Thr498 can be phosphorylated to a similar extent in WT β2a and L493A-β2a in intact cells.

In order to investigate the regulation of CaMKII interaction with β2a in intact cells by modification of Thr498 and the surrounding domain, lysates of HEK293 cells expressing constitutively active myc-tagged CaMKIIδ without or with FLAG-tagged β2a subunits (WT or mutated) were immunoprecipitated using FLAG antibodies. CaMKII was readily detected in immune complexes containing FLAG-tagged wild-type β2a or T498A-β2a, but could not be detected in immune complexes formed by T498E-β2a of L493A-β2a (Fig. 6B). These findings demonstrate that the domain surrounding Thr498 is critical for association of CaMKII with β2a in cells, and suggest that phosphorylation at Thr498 diminishes CaMKII binding to β2a in cells.

DISCUSSION

A diverse family of VGCCs regulates Ca2+ entry into excitable and non-excitable cells. The α1 subunits confer core biophysical and pharmacological behavior of each type of VGCC. However, a cytosolic loop between the first and second major transmembrane domains in the α subunit is generally thought to constitutively interact with a β subunit. Alternative splicing of mRNAs from four mammalian genes generates >20 distinct β subunit proteins that have divergent roles in modulating the trafficking and biophysical properties of VGCCs (6). The β subunits share highly conserved SH3 and GK domains that form a compact structure, with a hydrophobic groove in the GK domain that interacts with the α subunit (26). However, some β subunits lack substantial parts of the SH3 and GK domains, yet still modulate LTCCs (27). These observations support recent findings showing that additional SH3-GK independent modulatory interactions between the α and β subunits are important for regulating VGCC activity (28–31). The variable domains presumably account for the unique effects of β subunit variants on the properties of α subunits.

Most studies have focused on the roles of protein interactions and post-translational modifications of the α subunit in modulating VGCCs. However, the importance of β subunits in regulating VGCCs has received increasing attention. Initial studies suggested that PKA phosphorylation of the β2 subunit plays a role in facilitating LTCCs (32), although the importance of this modification in native cells has recently been questioned (33). In addition, β subunits have been shown to serve as scaffolding proteins that bind REM GTPases to inhibit VGCCs (34, 35), and AHNAKs to link VGCCs to the actin cytoskeleton (36). Our recent work showed that CaMKII binds β2a subunits and colocalizes with β2a in adult cardiomyocytes. Moreover, phosphorylation of β2a at Thr498 is required for Ca2+ and CaMKII-dependent facilitation of LTCCs in cardiomyocytes (22). While β subunit variants have unique direct effects on the biophysical properties and trafficking of LTCCs, the β isoform-selectivity of regulation by CaMKII and other modulators is poorly understood.

The β subunit variants tested here associate with multiple VGCC α subunits (reviewed in (2, 6)). Thus, our current results showing that activated/Thr286 autophosphorylated CaMKII forms stable complexes with β1b and β2a, but not with β3 or β4, lead us to hypothesize that association of CaMKII with VGCC complexes will depend on the identity of the associated β subunit. The β1b and β2a, subunits contain an LXRXXS/T motif similar to sequences surrounding phosphorylation sites in NR2B and the CaMKII autoinhibitory domain that also form stable complexes with the CaMKII catalytic domain. Mutation of Leu493 to Ala within this motif reduced CaMKII binding to β2a by >90%, but surprisingly had little effect on the initial rate of phosphorylation at Thr498, or on the overall phosphorylation stoichiometry at multiple sites. The lack of conservation of this motif accounts for the failure to detect binding to β3 or β4.

Despite the apparent binding selectivity, CaMKII phosphorylates all four β subunit variants tested here with comparable relative rates and overall extent. The high maximal phosphorylation stoichiometries suggest that CaMKII efficiently phosphorylates several sites in each β isoform in vitro. Indeed, we previously identified 6 CaMKII phosphorylation sites in β2a (22), and it will be important to identify phosphorylation sites in other β isoforms and determine their impact on the properties of VGCCs. Data presented here show that phosphorylation at Thr498 in β2a negatively regulates CaMKII binding both in vitro and in situ. Presumably the conserved LXRXXS/T motif in β1b is responsible for the regulated binding of CaMKII to this variant. Thus, interactions of CaMKII with β and/or β1 variants are regulated by phosphorylation, likely playing an important role in modulating CaMKII targeting to LTCCs and/or other VGCCs.

Interestingly, β subunits are not generally thought to be important in the regulation of T-type VGCCs. However, recent studies show that CaMKII directly interacts with and phosphorylates the II-III linker of the CaV3.2 α subunit, shifting the current-voltage activation curve (15, 16). In addition, recent data suggest that CaMKII may also interact with multiple cytoplasmic domains in CaV1.2 (19). Thus, association of CaMKII with VGCC α subunits may play additional important feature allowing localized Ca2+ concentrations to feedback and regulate Ca2+ influx.

Emerging data over the last couple of years suggest that mechanisms underlying CaMKII modulation of LTCCs are complex. Phosphorylation of multiple sites in the CaV1.2 α subunit by CaMKII appears to play distinct roles in voltage-and calcium-dependent modulation in heterologous cells (18, 20). In addition, interactions of CaMKII with multiple intracellular domains of the CaV1.2 α subunit have been implicated in LTCC facilitation (19). In contrast, phosphorylation at Thr498 in β2a is required for CaMKII to increase channel open probability at the single channel level and to facilitate whole cell Ca2+ currents in adult cardiomyocytes (22). The present observations that phosphorylation at Thr498 appears to be relatively independent of the stable binding of CaMKII to β2a (Fig. 4), and also inhibits CaMKII binding (Fig. 3, Fig. 5, Fig. 6), provides insights that may reconcile these seemingly disparate observations. Interestingly, phosphorylation of β2a in preformed complexes appears to promote dissociation of CaMKII (Fig. 6). CaMKII dissociation might be required to allow protein phosphatases to act on the phospho-Thr498 site to reset channels to their basal state. Presumably, such a mechanism would be most relevant if Thr498 phosphorylation directly modulates LTCC properties, as suggested by the importance of Thr498 in CaMKII-mediated increases in LTCC open probability and LTCC current facilitation in adult cardiomyocytes (22). Secondly, CaMKII may serve a structural role to dynamically assemble complexes containing additional, as yet unidentified, proteins associated with LTCCs. Thus, Thr498 phosphorylation in β2a may promote re-organization of these protein complexes to enable facilitation. Structural roles for CaMKII have been postulated in neuronal postsynaptic densities (23). Previous studies showed that disruption of the actin- or tubulin-based cytoskeleton essentially abrogated CaMKII-dependent facilitation of cardiac LTCCs without affecting PKA-dependent facilitation, suggesting an important role for higher orders of molecular organization close to LTCCs in mediating the effects of CaMKII (37). A final possibility is that dissociation from β2a induced by Thr498 phosphorylation is important in allowing activated CaMKII to phosphorylate nearby regulatory sites in the α1c or β subunits and/or other associated proteins. In other words, stable binding of activated CaMKII to β2a may limit access of phosphorylation sites in other proteins to the CaMKII active site. Consistent with this hypothesis, dissociation of CaMKII from β2a is substantially reduced by T498A mutation, perhaps explaining why CaMKII phosphorylates this mutant to a lower final stoichiometry than T498E-β2 and L493A-β2, which have much weaker interactions with CaMKII (Fig. 4B). Further studies will be needed to clarify the mechanism of CaMKII actions at VGCC complexes and, perhaps, to identify new CaMKII targets.

Figure 5. Pre-phosphorylation of β2a at Thr498 inhibits the association of CaMKII.

A. Wild type and mutated GST-β2a proteins were preincubated with activated CaMKIIδ2 in the presence or absence of ATP. Samples were resolved by SDS-PAGE and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes to detect total protein loaded (top) and to probe with [32P]CaMKIIδ2 by overlay assay and autoradiography (middle). Binding was quantified using a phosphoimager and normalized to binding to non-phosphorylated wild type protein: the mean±sem from 3 experiments is plotted. #: p<0.001 vs. corresponding non-phosphorylated protein. *: p<0.001 vs. non-phosphorylated GST-β2a wild type. Further post analyses using t tests showed that pre-phosphorylation significantly reduced CaMKII binding to the L493A mutant (†: p<0.05).

In summary, findings reported here and in other recent papers suggest that feedback regulation of Ca2+ influx via VGCCs is precisely controlled in specific subcellular microdomains by multiple mechanisms that allow CaMKII and other Ca2+-dependent signaling proteins to associate with channel subunits. The precise nature of the feedback regulation by CaMKII seems likely to depend on the identity of the β subunit associated with the complex. The regulated interaction of activated CaMKII with β1 and β2 variants seem likely to be important, although phosphorylation of β3 and β4 may also play a role in some cases. Our findings are in line with recent studies suggesting that subcellular targeting of CaMKII via its interactions with CaMKAPs modulates the specificity of its downstream actions (11, 12). These complex biochemical mechanisms for feedback regulation of Ca2+ influx via VGCCs presumably provide great flexibility for modulating a variety of downstream signaling events such as cardiac excitation-contraction and excitation-transcription coupling and neuronal synaptic plasticity. Moreover, alterations in the association of β subunits with VGCCs might disrupt feedback regulation and downstream signaling in heart failure and other diseases (38).

Supplementary Material

Figure 7. CaMKII interaction with β2a is regulated by Thr498 phosphorylation in situ.

Myc-tagged T287D-CaMKIIδ2 was co-expressed with or without FLAG-tagged wild type or mutated β2a proteins in HEK293 cells. Aliquots of the cell lysates (Inputs), FLAG immune supernatants (Super) and FLAG immune complexes (Pellets) were immunoblotted. A: Probing FLAG immune complexes using antibodies raised to phospho-Thr286 in CaMKIIα showed that WT and L493A β2a are partially phosphorylated at Thr498 in intact cells. B: Probing FLAG immune complexes using CaMKIIδ antibodies revealed that CaMKII was associated with WT and T498A β2a but could not be detected in the T498E and L493A β2a immune complexes. The data are representative of >4 experiments.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We appreciate outstanding technical assistance from Martha A. Bass.

ABBREVIATIONS

- CaMKII

calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II

- CaMKAP

CaMKII-associated protein

- GK

guanylate kinase-like

- GST

glutathione-S-transferase

- LTCC

L-type VGCC

- VGCC

voltage-gated calcium channel

Footnotes

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) research grants to R.J.C. (MH63232) and M.E.A. (HL062494, HL70250; HL46681). M.E.A. is an AHA Established Investigator. CEG was supported by an Institutional NIH training grant in cardiology (HL07411) and an AHA Fellowship. S.A.A. was partially supported by an AHA Fellowship.

SUPPORTING INFORMATION AVAILABLE

Supplementary data (Supplementary Figure 1) showing that CaMKII binding to GST-β1b and GST-β2a in a glutathione agarose co-sedimentation assay is dependent on prior autophosphorylation of CaMKII is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

REFERENCES

- 1.Arikkath J, Campbell KP. Auxiliary subunits: essential components of the voltage-gated calcium channel complex. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2003;13:298–307. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(03)00066-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Catterall WA. Structure and regulation of voltage-gated Ca2+ channels. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2000;16:521–555. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.16.1.521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hille B. Ion channels of excitable membranes. 3rd ed. Sunderland, Mass: Sinauer; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Perez-Reyes E, Castellano A, Kim HS, Bertrand P, Baggstrom E, Lacerda AE, Wei XY, Birnbaumer L. Cloning and expression of a cardiac/brain beta subunit of the L-type calcium channel. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1992;267:1792–1797. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bichet D, Cornet V, Geib S, Carlier E, Volsen S, Hoshi T, Mori Y, De Waard M. The I-II loop of the Ca2+ channel alpha1 subunit contains an endoplasmic reticulum retention signal antagonized by the beta subunit. Neuron. 2000;25:177–190. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80881-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dolphin AC. Beta subunits of voltage-gated calcium channels. J Bioenerg Biomembr. 2003;35:599–620. doi: 10.1023/b:jobb.0000008026.37790.5a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.De Koninck P, Schulman H. Sensitivity of CaM kinase II to the frequency of Ca2+ oscillations. Science. 1998;279:227–230. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5348.227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lisman J, Schulman H, Cline H. The molecular basis of CaMKII function in synaptic and behavioural memory. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2002;3:175–190. doi: 10.1038/nrn753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hudmon A, Schulman H. Structure-function of the multifunctional Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II. Biochem J. 2002;364:593–611. doi: 10.1042/BJ20020228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Colbran RJ. Targeting of calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II. Biochem J. 2004;378:1–16. doi: 10.1042/BJ20031547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tsui J, Inagaki M, Schulman H. Calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II (CaMKII) localization acts in concert with substrate targeting to create spatial restriction for phosphorylation. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2005;280:9210–9216. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M407653200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tsui J, Malenka RC. Substrate localization creates specificity in calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II signaling at synapses. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:13794–13804. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M600966200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Scott JD, Pawson T. Cell communication: the inside story. Scientific American. 2000;282:72–79. doi: 10.1038/scientificamerican0600-72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pawson T, Nash P. Assembly of cell regulatory systems through protein interaction domains. Science. 2003;300:445–452. doi: 10.1126/science.1083653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Welsby PJ, Wang H, Wolfe JT, Colbran RJ, Johnson ML, Barrett PQ. A mechanism for the direct regulation of T-type calcium channels by Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent kinase II. J Neurosci. 2003;23:10116–10121. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-31-10116.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yao J, Davies LA, Howard JD, Adney SK, Welsby PJ, Howell N, Carey RM, Colbran RJ, Barrett PQ. Molecular basis for the modulation of native T-type Ca channels in vivo by Ca /calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:2403–2412. doi: 10.1172/JCI27918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gao L, Blair LA, Salinas GD, Needleman LA, Marshall J. Insulin-like growth factor-1 modulation of CaV1.3 calcium channels depends on Ca2+ release from IP3-sensitive stores and calcium/calmodulin kinase II phosphorylation of the alpha1 subunit EF hand. J Neurosci. 2006;26:6259–6268. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0481-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Erxleben C, Liao Y, Gentile S, Chin D, Gomez-Alegria C, Mori Y, Birnbaumer L, Armstrong DL. Cyclosporin and Timothy syndrome increase mode 2 gating of CaV1.2 calcium channels through aberrant phosphorylation of S6 helices. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:3932–3937. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0511322103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hudmon A, Schulman H, Kim J, Maltez JM, Tsien RW, Pitt GS. CaMKII tethers to L-type Ca2+ channels, establishing a local and dedicated integrator of Ca2+ signals for facilitation. J Cell Biol. 2005;171:537–547. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200505155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee TS, Karl R, Moosmang S, Lenhardt P, Klugbauer N, Hofmann F, Kleppisch T, Welling A. Calmodulin Kinase II Is Involved in Voltage-dependent Facilitation of the L-type Cav1.2 Calcium Channel: IDENTIFICATION OF THE PHOSPHORYLATION SITES. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2006;281:25560–25567. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M508661200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yasuda R, Sabatini BL, Svoboda K. Plasticity of calcium channels in dendritic spines. Nat Neurosci. 2003;6:948–955. doi: 10.1038/nn1112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Grueter CE, Abiria SA, Dzhura I, Wu Y, Ham AJ, Mohler PJ, Anderson ME, Colbran RJ. L-Type Ca(2+) Channel Facilitation Mediated by Phosphorylation of the beta Subunit by CaMKII. Mol Cell. 2006;23:641–650. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Robison AJ, Bass MA, Jiao Y, MacMillan LB, Carmody LC, Bartlett RK, Colbran RJ. Multivalent interactions of calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II with the postsynaptic density proteins NR2B, densin-180, and alpha-actinin-2. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2005;280:35329–35336. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M502191200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McNeill RB, Colbran RJ. Interaction of autophosphorylated Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II with neuronal cytoskeletal proteins. Characterization of binding to a 190-kDa postsynaptic density protein. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1995;270:10043–10049. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.17.10043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.White RR, Kwon YG, Taing M, Lawrence DS, Edelman AM. Definition of optimal substrate recognition motifs of Ca2+-calmodulin-dependent protein kinases IV and II reveals shared and distinctive features. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1998;273:3166–3172. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.6.3166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Van Petegem F, Clark KA, Chatelain FC, Minor DL., Jr Structure of a complex between a voltage-gated calcium channel beta-subunit and an alpha-subunit domain. Nature. 2004;429:671–675. doi: 10.1038/nature02588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Harry JB, Kobrinsky E, Abernethy DR, Soldatov NM. New short splice variants of the human cardiac Cavbeta2 subunit: redefining the major functional motifs implemented in modulation of the Cav1.2 channel. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:46367–46372. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M409523200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Butcher AJ, Leroy J, Richards MW, Pratt WS, Dolphin AC. The importance of occupancy rather than affinity of CaV(beta) subunits for the calcium channel I-II linker in relation to calcium channel function. J Physiol. 2006;574:387–398. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.109744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Leroy J, Richards MW, Butcher AJ, Nieto-Rostro M, Pratt WS, Davies A, Dolphin AC. Interaction via a key tryptophan in the I-II linker of N-type calcium channels is required for beta1 but not for palmitoylated beta2, implicating an additional binding site in the regulation of channel voltage-dependent properties. J Neurosci. 2005;25:6984–6996. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1137-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang R, Dzhura I, Grueter CE, Thiel W, Colbran RJ, Anderson ME. A dynamic alpha-beta inter-subunit agonist signaling complex is a novel feedback mechanism for regulating L-type Ca2+ channel opening. Faseb J. 2005;19:1573–1575. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-3283fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Maltez JM, Nunziato DA, Kim J, Pitt GS. Essential Ca(V)beta modulatory properties are AID-independent. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2005;12:372–377. doi: 10.1038/nsmb909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bunemann M, Gerhardstein BL, Gao T, Hosey MM. Functional regulation of L-type calcium channels via protein kinase A-mediated phosphorylation of the beta(2) subunit. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1999;274:33851–33854. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.48.33851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ganesan AN, Maack C, Johns DC, Sidor A, O'Rourke B. {beta}-Adrenergic Stimulation of L-type Ca2+ Channels in Cardiac Myocytes Requires the Distal Carboxyl Terminus of {alpha}1C but Not Serine 1928. Circ Res. 2006 doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000202692.23001.e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Beguin P, Mahalakshmi RN, Nagashima K, Cher DH, Ikeda H, Yamada Y, Seino Y, Hunziker W. Nuclear sequestration of beta-subunits by Rad and Rem is controlled by 14-3-3 and calmodulin and reveals a novel mechanism for Ca2+ channel regulation. J Mol Biol. 2006;355:34–46. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Finlin BS, Correll RN, Pang C, Crump SM, Satin J, Andres DA. Analysis of the complex between Ca2+ channel beta-subunit and the Rem GTPase. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2006;281:23557–23566. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M604867200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hohaus A, Person V, Behlke J, Schaper J, Morano I, Haase H. The carboxyl-terminal region of ahnak provides a link between cardiac L-type Ca2+ channels and the actin-based cytoskeleton. Faseb J. 2002;16:1205–1216. doi: 10.1096/fj.01-0855com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dzhura I, Wu Y, Colbran RJ, Corbin JD, Balser JR, Anderson ME. Cytoskeletal disrupting agents prevent calmodulin kinase, IQ domain and voltage-dependent facilitation of L-type Ca2+ channels. J Physiol. 2002;545:399–406. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.021881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 38.Bodi I, Mikala G, Koch SE, Akhter SA, Schwartz A. The L-type calcium channel in the heart: the beat goes on. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:3306–3317. doi: 10.1172/JCI27167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.