Abstract

Previous research has suggested that bipolar disorder is characterized by a state-dependent decrease in the ability to recognize facial affect during mania. It remains unclear, though, whether people who are only vulnerable to the disorder show these changes in facial affect recognition. It is also unclear whether minor shifts in mood affect the recognition of facial emotion. Thus, this study examined the effects of positive mood induction on the facial affect recognition of undergraduates vulnerable to mania. Fifty-two undergraduates completed the Hypomanic Personality Scale, and also completed a measure of their ability to recognize affect in pictures of faces. After receiving false success feedback on another task to induce a positive mood, they completed the facial affect recognition measure again. Although we expected to find a relationship between higher Hypomanic Personality Scale (HPS) scores and an impaired ability to recognize negative facial affect after a positive mood induction, this was not found. Rather, there was a significant interaction between HPS scores and happiness level, such that individuals with higher scores on the HPS who also reported higher levels of happiness were particularly adept at identifying subtle facial expressions of happiness. This finding expands a growing literature linking manic tendencies to sensitivity to positive stimuli and demonstrates that this sensitivity may have bearing on interpersonal interactions.

Keywords: Mania, Hypomania, Facial affect recognition, Bipolar disorder, Hypomanic personality scale

Introduction

Bipolar disorder, defined on the basis of manic symptoms (American Psychiatric Association, 2000) is a grave psychiatric disorder. Patients who experience manic episodes are often beset with a wide range of functional impairments even after recovery, including deficits in executive functioning (Van Gorp, Altshuler, Theberge, Wilkins, & Dixon, 1998), poor psychosocial functioning (Goldberg, Harrow, & Grossman, 1995), low rates of employment (Dickerson et al., 2004), and substantially elevated suicide rates (Chen & Dilsaver, 1996). Moreover, although over 80% of people with bipolar disorder reach syndromal recovery after 1 year (Tohen et al., 2000), very few return to premorbid levels of functioning (Strakowski et al., 1998).

This disorder has many aspects. Of particular interest to us are aspects pertaining to emotion. Compared to healthy controls, persons with bipolar disorder show differential activation of brain regions that are involved in emotion perception and processing (Phillips, Drevets, Rauch, & Lane, 2003a). Indeed, several theories suggest that there are neural deficits in bipolar disorder in regions that are intricately involved with emotion processing (Phillips, Drevets, Rauch, & Lane, 2003b).

The role of emotional experience and emotional communication in bipolar disorder is complex. There is evidence that even during periods of remission, people with bipolar disorder have more intense emotions than others. For example, remitted bipolar disorder has been related to greater variability in daily affect (Lovejoy & Steuerwald, 1995), impaired performance on cognitive tasks after failure (Ruggero & Johnson, 2006), and elevated cortisol levels during a difficult math task (Goplerud & Depue, 1985). Findings of several studies also indicate that people with bipolar disorder have more intense emotional reactivity to positive than negative stimuli (Johnson, Gruber, & Eisner, 2007).

Although there has been interest in emotion perception among persons with bipolar disorder, studies to date have yielded conflicting results. Some researchers have found that people with this disorder perform more poorly and take longer on facial affect recognition tasks than healthy controls (Addington & Addington, 1998; Getz, 2005; Getz, Shear, & Strakowski, 2003). From these findings, it has been theorized that difficulties in interpersonal relationships among manic patients may stem partly from an inability to identify the emotions conveyed in facial expressions. Consequently, they approach in social situations when withdrawal would be more appropriate.

Conversely, in other research people with bipolar disorder had enhanced recognition of disgust expressions (Harmer, Grayson, & Goodwin, 2002), and children with bipolar disorder misidentified other children’s faces as angry when they were not (McClure, Pope, Hoberman, Pine, & Leibenluft, 2003). Hence, despite some evidence of a generalized deficit in facial affect recognition, people with bipolar disorder in remission also have displayed a supersensitivity to certain specific negative facial affective displays. One explanation for these findings is that the negative interpersonal experiences and low self-esteem that unfold as a consequence of the disorder may lead these people to become very sensitized to at least certain negative emotional expressions. Consistent with this idea, outside of bipolar disorder supersensitivity to negative facial expressions has been tied to experiences of abuse (Pollak & Sinha, 2002).

Hence, the evidence to date leaves many issues unclear. For example, it is unclear whether sensitivity to specific negative expressions emerges from negative social experiences that accompany the disorder or is a manifestation of the disorder that precedes the onset of episodes. Consequently, one goal of the study reported here was to examine how facial affect recognition varies by risk for the disorder, particularly among participants who had not experienced any episodes. This would allow us to identify differences that might reflect bipolar vulnerability rather than scars of the negative social experiences that occur during and after manic episodes.

A second goal was to examine state-dependent shifts in facial affect recognition. Generally, affect recognition deficits have been found to be correlated with elevations in symptoms (Addington & Addington, 1998). Acute manic symptoms appear to particularly impair the ability to recognize negative faces. For example, Lembke and Ketter (2002) found that bipolar patients in a manic state performed more poorly than euthymic bipolar patients on the recognition of negative emotions. The recognition of sad faces was poorest among the patients with the highest severity of mania. A question that remains is whether even smaller shifts in mood state, such as happy mood states, can induce shifts in the recognition of negative faces.

Finally, given previous evidence of increased sensitivity to cues of reward among people with bipolar disorder (Johnson et al. 2007), particularly after positive mood inductions (Johnson, Ruggero, & Carver, 2005), it is worth examining responses to happy facial expressions during positive mood states among people with bipolar disorder. Studies of mood-state effects on facial affect recognition have not found effects for happy faces (Lemkbe & Ketter, 2002). However, when happy expressions are at a full intensity, they are easily identified. Indeed, virtually no errors were found in recognizing happy facial expressions across groups in one study (Lembke & Ketter, 2002). Hence, to study sensitivity to happy facial expressions, it is important to examine reactions to faces with less intense expressions of happiness.

The present study was designed to determine whether deficits in the ability to identify facial emotion were related to risk for mania, and whether performance would shift with happiness. To examine the latter question, we conducted a mood induction using false success feedback. We hypothesized that risk for mania would relate to decreased accuracy in recognizing negative facial expressions after a positive mood induction, even after controlling for any differences in current symptom levels.

Methods

Participants

Participants were 52 undergraduates (35 females, mean age 18.39, 24 identified as members of minority ethnic groups) enrolled in an Introductory Psychology course at the University of Miami. Students complete research involvement as a requirement for the course. If they do not wish to participate in a research study, they may elect to do other psychology reading assignments as directed by their instructor.

The Hypomanic Personality Scale (HPS), a screening measure designed to assess risk for mania, as well as the Beck Depression Inventory—Short Form (BDI-SF) were administered in class sessions early in the semester to ~800 students. To ensure adequate numbers of participants at higher risk for mania, students who scored in the upper 10th percentile (≥30 on the HPS, z ≥ 0.40) were contacted by e-mail and invited to take part in the study. Every effort was made to schedule appointments at times that would work well for these potential participants. Other students, regardless of HPS scores, signed up without invitation and with no special criteria. In all cases, sign-up was via a departmental website.

Within this sample, seven people reported a lifetime history of depression, one person (who was excluded from the main analyses) reported a diagnosis of bipolar disorder, and one person was taking the antidepressant Effexor.

Measures

Hypomanic personality scale

The HPS (Eckblad & Chapman, 1986) is a self-report questionnaire designed to identify persons at risk for mania. The scale consists of 48 true/false items such as “I often feel excited and happy for no apparent reason,” and “My moods do not seem to fluctuate any more than most people’s do.” Previous findings indicate that 78% of high-scorers experience a hypomanic or manic episode (Eckblad & Chapman, 1986), and the scale has achieved strong validity in predicting diagnoses over a 13-year follow-up period (Kwapil et al., 2000). The validity of the scale in predicting onset of manic episodes has been replicated in other countries (Meyer, 2003). The scale has also been shown to correlate with a wide range of variables related to clinical diagnoses of bipolar disorder, such as affective lability (Hofmann & Meyer, 2006), psychophysiological sensitivity to positive stimuli (Sutton & Johnson, 2002), alcohol use (Krumm Marabet & Meyer, 2005), reward sensitivity (Meyer, Johnson, & Carver, 1999), creativity (Rawlings & Georgiou, 2004), and cognitive processes (Meyer & Krumm-Marabet, 2003; Thomas & Bentall, 2002). In validation studies, the HPS obtained a coefficient alpha reliability of 0.87 and a test-retest reliability of 0.81 after an interval of 15 weeks. In the present study the HPS obtained a reliability of α = 0.85. HPS score was not correlated with age (r = 0.13, p = 0.38) or sex (r = 0.13, p = 0.36). HPS scores did not differ by ethnicity, F (4, 46) = 1.78, p = 0.15.

Altman self-rating mania scale

Our goal was to test whether minor shifts in mood, smaller than symptomatic changes, would predict changes in affect recognition. To ensure that any effects found were not simply a function of current manic or depressive symptoms, two self-report measures were given. For mania, the Altman Self-Rating Mania Scale (ASRM; Altman, Hedeker, Peterson, & Davis, 1997) was used. The ASRM has shown adequate concurrent validity with the Young Mania Rating Scale (r = 0.72, p < 0.001). This instrument has also been shown to outperform other self-report measures in screening for manic symptoms (Altman, Hedeker, & Peterson, 2001).

Beck depression inventory: short form

For depression, the BDI-SF (Beck & Beck, 1972) was used. The BDI-SF has withstood numerous rounds of validation in measuring the extent of depressive symptoms (Foelker, Shewchuk, & Niederehe, 1987), and has demonstrated high concurrent validity with the long form of the BDI (r = 0.96) (Love, Grabsch, & Clarke, 2004). It also has an adequate relationship with the Asberg Depression Rating Scale (r = 0.76) (Luty & O’Gara, 2006).

Mood state questions

To assess level of happiness, the participants were asked to rate how happy they were, as well as how well they expected to do on the upcoming task, by responding using a one (e.g., “not happy at all”) to seven (“extremely happy”) scale. These questions were asked before the facial affect recognition task, as well as after the success feedback.

As a check to ensure that persons were alert, and not nervous or sad, they were also asked to report how alert, nervous, and sad they felt using parallel 1–7 response formats. Responses to these items verified that persons were generally alert without high levels of negative affect. For example, after feedback, the mean alert score was 5.34, the mean nervous score was 2.42, and the mean sad score was 1.59.1

Computerized facial affect recognition task

To assess the ability to identify facial emotion, we created a novel facial affect recognition task using pictures from the Facial Expressions of Emotion: Stimuli and Tests (FEEST; Young, Perret, Calder, Sprengelmeyer, & Ekman, 2002), a set of photographs developed by Ekman and Friesen (1976). We selected black and white photographs of eight people’s faces displaying no emotion and also each of the following emotions: anger, fear, sadness, happiness, disgust, and surprise. To control for the possible influences of hair color or style, each photograph is edited so that the person’s hair does not appear in the photograph. The task contains four people’s faces (one man and three women) expressing each of six emotions at three different intensities (25, 50, and 75%), plus a neutral face, for a total of 76 trials. For each picture presented, the task is to indicate what emotion it is portraying, from among the six emotion options.

The first part of the task contains four practice items. The practice items are identical in format to the actual trial items, although the person’s face used in the practice items (a man) does not appear in the actual trials.

After the practice block, the experimenter leaves the room and the participant begins the first block of the actual trial items. For each trial, a 12 × 15 cm2 photograph of a face is displayed, and the participants are instructed to select the emotion from a list of emotions (including neutral) that they think is being expressed in the picture. Each screen is displayed until the participant selects an answer, at which point the next trial begins. The photographs are presented in a random order and do not repeat. There are two blocks of trials—one before the mood induction and one after.

Procedure

Each participant was greeted individually at a scheduled appointment time. After the experimenter gave a brief summary of the study, written informed consent procedures were completed. Participants completed the ASRM and a brief questionnaire about their psychiatric history.

Next, participants completed the computerized facial affect recognition task. The experimenter began by telling participants that people who do well on these tasks are particularly socially adept; this was done to ensure that the participants were motivated to do their best. The participant then began the computer portion of the study, which was conducted on a Dell computer with a 31 × 24 cm2 Trinitron monitor. The facial affect task was created and presented to participants using the program Eprime, Version 1.1. The first several screens contained brief introductory remarks followed by a description of the facial affect recognition task. Participants were then asked to respond to the mood state questions to measure baseline happiness levels. The participants were also told that their accuracy and response times were being recorded, and that they should try to do their best.

After completing the first block of the facial affect recognition task, participants viewed several screens on the computer that contained instructions for the cognitive word task (Lawrence, Carver, & Scheier, 2002), which was designed to induce a positive mood through the use of false success feedback. Participants were told that they would be presented with words from obscure languages in their English phonetic translations and asked if they think the word means the same thing as another English word. In fact, the words they were shown were not from obscure languages but were nonsense words comprised of three to eight English letters.

To ensure that participants were sufficiently engaged in the task, they were told that people who can sense subtle verbal cues from other languages usually have many social advantages. They were then told that most students who complete this task score in the 60–65% range, and that a score of 70% is generally considered excellent. Furthermore, they were told that if they could reach an 85% success rate by the end of the task, they would receive triple experiment credit for their Introductory Psychology class, which would fulfill the requirement for the entire semester.

Words were presented one at a time, in blocks of 10. To induce a positive mood, after each block of ten items, the participants received the same standardized feedback regardless of their performance on the task. Indeed, after each block they were told that their score thus far was 60, 73, 77, 82, and 88%, respectively. After the last block, they were congratulated for reaching their goal and receiving triple experiment credit. They were then presented with the mood state questions for the second time to measure post-induction happiness levels.

The participants were then reminded of the instructions for the facial affect recognition task and completed the second block of trials, which contained different faces (one man and three women). These also appeared in a random order. The last screen instructed the participants to go outside the room and inform the experimenter that they had finished. The experimenter then asked several questions to gauge the effectiveness and credibility of the bonus credit experience, and then fully debriefed the participants. During the debriefing, they were told that the cognitive word task actually contained nonsense words, and that everyone received the triple credit regardless of their responses on the task.

Results

Descriptive statistics and preliminary analyses

Descriptive statistics for the sample can be found in Table 1. To determine whether the participants found the bonus credit experience to be believable, they were asked to rate the believability of the bonus credit experience on a zero (“least believable”) to ten (“most believable”) scale. The mean rating on this measure was 7.16 (SD = 2.20), and these ratings were not correlated with accuracy in facial affect recognition of happy or negative faces, either before or after the positive feedback. Moreover, HPS scores were uncorrelated with believability ratings, r (N = 51) = 0.05, p = 0.72.

Table 1.

Sample statistics for key variables (N = 51)

| Variable | Mean | SD |

|---|---|---|

| Before mood induction | ||

| Accuracy for negative emotions | 0.43 | 0.10 |

| Accuracy for positive emotions | 0.87 | 0.09 |

| Happiness ratinga | 4.67 | 1.14 |

| HPS | 25.90 | 10.37 |

| BDI-SF | 16.48 | 3.53 |

| ASRM | 11.60 | 4.67 |

| After mood induction | ||

| Accuracy for negative emotions | 0.57 | 0.09 |

| Accuracy for positive emotions | 0.72 | 0.12 |

| Happiness ratinga | 5.94 | 1.01 |

Note: For this and all subsequent tables, HPS Hypomanic Personality Scale, BDI-SF Beck Depression Inventory-Short Form, and ASRM Altman Self-Rating Mania Scale

Self-report

As a manipulation check, a repeated measures Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) was conducted to measure whether the success feedback increased happiness. As expected, happiness levels increased significantly after the feedback as compared to baseline levels, Wilk’s Lambda = 0.34, F (1, 50) = 98.27, p < 0.001. Nonetheless, there was a great deal of variability in happiness after the induction (see Table 1 for the means and SD). For this reason, analyses included level of happiness post-induction as a predictor. HPS scores were not related to happiness at baseline, r (N = 51) = 0.16, p = 0.26, nor to happiness after the induction controlling for baseline happiness levels, partial r (df = 48) = 0.12, p = 0.42.

Main analyses

This study had two goals: (1) to test whether the HPS was related to baseline accuracy in detecting positive and negative facial expressions, and (2) to test whether the HPS interacted with happiness to influence accuracy. The percent of trials in which a person was accurate was calculated for positive (happiness) and negative (fear, anger, disgust, and sadness) emotions. In these analyses, accuracy was calculated across intensity level of emotion. In all analyses, HPS scores were used as a continuous variable.

First, correlations were conducted to examine HPS scores as a predictor of accuracy in detecting faces before the mood induction. HPS scores were not related to baseline accuracy in recognizing happy faces, r (N = 51) = −0.12, p = 0.30, nor in recognizing negative faces, r (N = 51) = 0.22, p = 0.11.

Second, to determine if HPS scores interacted with happiness to predict accuracy in detecting positive and negative facial expressions, respectively, two parallel hierarchical multiple linear regression models were conducted. Analyses controlled for the main effects of HPS and happiness, as well as subsyndromal symptoms of mania (ASRM) and depression (BDI-SF). For each regression, baseline accuracy (before mood induction) was entered in block 1, HPS score was entered in block 2, and in block 3, three mood state variables were included: ratings of happiness after the induction, baseline score on the BDI-SF, and baseline score on the ASRM. In block 4, the interaction of HPS × Happiness was entered. All independent variables were z-transformed before model entry.

As shown in Table 2, accuracy in detecting negative facial expressions after the induction was significantly predicted by baseline ability to recognize negative facial emotions. Other variables were not significantly related to the ability to detect negative facial expressions. As shown in Table 3, accuracy in detecting happy facial expressions after the induction was significantly predicted by baseline ability to recognize happy facial expressions. Accuracy in detecting happy facial expressions after the induction was not significantly related to HPS scores or to the mood state variables. However, there was a significant interaction between HPS scores and happiness ratings (mood state).

Table 2.

Predictors of post-mood induction accuracy for negative faces (N = 51)

| Block | Variable entered | R2 | R2 Change | Final β |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Baseline Accuracy | 0.27 | 0.27*** | 0.50*** |

| 2 | HPS | 0.27 | 0.00 | −0.13 |

| 3 | BDI-SF | 0.33 | 0.06 | 0.01 |

| ASRM | 0.26 | |||

| Happiness | −0.13 | |||

| 4 | HPS × Happiness | 0.33 | 0.00 | 0.03 |

p < 0.001

Table 3.

Predictors of post-mood induction accuracy for happy faces (N = 51)

| Block | Variable entered | R2 | R2 change | Final β |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Baseline accuracy | 0.17 | 0.17** | 0.40** |

| 2 | HPS | 0.17 | 0.00 | −0.08 |

| 3 | BDI-SF | 0.26 | 0.09 | 0.22 |

| ASRM | 0.23 | |||

| Happiness | 0.00 | |||

| 4 | HPS × Happiness | 0.32 | 0.06* | 0.28* |

p ≤ 0.05;

p < 0.01

To assess whether these effects of HPS and mood state on accuracy in detecting happy facial expressions operated across various levels of facial affect intensity, we conducted three parallel hierarchical regression models to examine accuracy ratings on the trials of faces at 25% intensity, those at 50% intensity, and those at 75% intensity. For each intensity level, parallel analyses were conducted: the independent contributions of baseline accuracy, mood state, HPS, and HPS × Happiness were examined. For the regression models predicting 50 and 75% intensity, HPS and the interaction of HPS × Happiness were unrelated to accuracy ratings. Indeed, accuracy was so high that there was virtually no variability to predict. Accuracy in detecting happy faces at 25% intensity, however, was significantly predicted by baseline accuracy in detecting happy faces at 25% intensity, as well as the interaction of HPS × Happiness (see Table 4).

Table 4.

Predictors of post-mood induction accuracy for happy faces at 25% intensity (N = 51)

| Block | Variable entered | R2 | R2 change | Final β |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Baseline accuracy | 0.18 | 0.18** | 0.39** |

| 2 | HPS | 0.19 | 0.00 | −0.04 |

| 3 | BDI-SF | 0.25 | 0.06 | 0.11 |

| ASRM | 0.27 | |||

| Happiness | −0.05 | |||

| 4 | HPS × Happiness | 0.31 | 0.06* | 0.29* |

p < 0.05;

p < 0.01

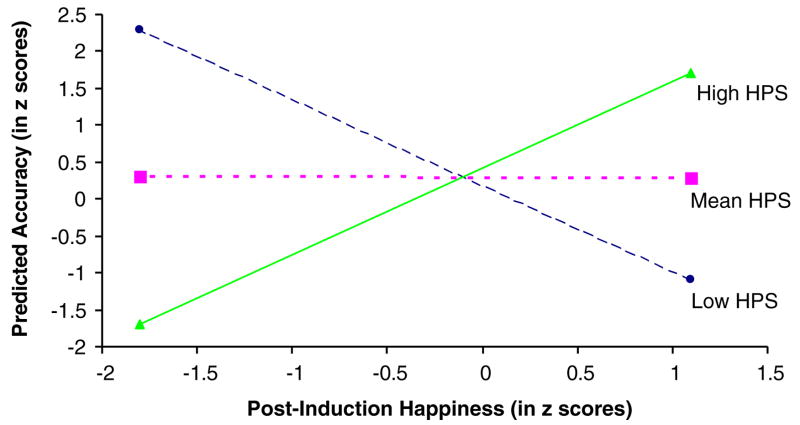

To partition the significant interaction term, we examined the effect of happiness on accuracy at 1 SD above the mean (represented in Fig. 1 as “High HPS”), at the mean (“Mean HPS”), and 1 SD below the mean (“Low HPS”) on the HPS. As shown in Fig. 1, for participants with high scores on the HPS, happiness was significantly and positively related to accuracy, β = 3.946, t = 2.201, p = 0.03, whereas for participants with low scores on the HPS, happiness was significantly and negatively related to accuracy, β = −4.11, t = −2.148, p = 0.037.

Fig. 1.

Predicted accuracy on 25% happy faces by happiness and HPS category

To ensure that the propensity to identify happy faces was not just a bias to label all faces as happy, trials in which participants made errors in labeling facial expressions were selected. The number of trials falsely labeled as happy per person was not correlated with HPS scores, r (N = 51) = 0.05, p = 0.73.

Discussion

The goal of this study was to examine the effect of positive mood shifts on the facial affect recognition skills of individuals vulnerable to mania. We hypothesized that, after a positive mood induction, vulnerability to mania would relate to an impaired ability to recognize negative facial expressions. No such impairment was apparent. Instead, we found that the individuals who exhibited a higher vulnerability to mania and who were happier post-induction showed an increased ability to detect subtle expressions of happiness. This effect emerged only when mood state was taken into account; there was no evidence of a greater sensitivity to happy faces when HPS scores were used without consideration of mood state. Furthermore, while persons at relatively higher risk for mania showed an enhanced ability to recognize happiness at 25%, this effect disappeared at the 50 and 75% intensity levels, which is notable because the 25% expression of happiness is subtle and difficult to detect. It was not the case that high HPS scorers incorrectly labeled faces as happy. Rather, persons at higher risk for mania were actually better at identifying subtle expressions of happiness when in a good mood.

Before considering the implications of this finding, it is important to note several limitations. While Ekman and Friesen’s (1976) pictures of facial emotion have withstood numerous rounds of validation, still photographs do not mirror a true interpersonal encounter. Thus, our study may have relatively low ecological validity. It will be important to determine whether supersensivity to positive facial expressions guides any differential interpersonal behavior in a naturalistic environment.

A second concern is our small sample size, which would certainly limit power to detect subtler effects, and would particularly limit the ability to examine interaction terms. This may explain our failure to replicate previous findings, such as increased recognition of negative facial expressions among persons at higher risk for mania.

A third concern about this study relates to the mood manipulation. One goal of our investigation was to examine the influence of minor mood shifts, and we conducted a mood manipulation to examine this issue. Although risk for mania was unrelated to the degree of mood shifts after the induction, a large number of people (regardless of HPS scores) responded only minimally to the mood manipulation. Indeed, the sensitivity to positive facial expressions emerged only among the participants who exhibited a higher risk for mania and who responded the most to the mood induction. Hence, replicating current findings with a more powerful mood induction would be helpful. More thorough assessment of symptom status would also be warranted.

It is also important to note that these findings were not parallel to those observed among people diagnosed with bipolar disorder. That is, previous researchers have found that clinically diagnosable bipolar disorder related to supersensitivity in identifying negative facial expressions (Harmer et al., 2002; McClure et al., 2003). The samples used in those studies differ from our study in several ways, though. They had more severe symptoms and were also more likely to have experienced stigma. It is unclear whether supersensitivity to negative facial expressions emerges with increased severity of disorder, or is learned through more severe interpersonal consequences. Overall, this area of investigation would benefit from studies that compared diagnosed bipolar patients with varying histories to persons vulnerable to hypomania to examine the extent to which facial affect sensitivity is related to the severity of disorder, mood state, and the nature of interpersonal consequences experienced secondary to symptoms.

Notwithstanding the limitations of the study, we found that persons who exhibited a higher risk for mania were adept at identifying subtly positive facial expressions when happy. This is consistent with a host of findings that bipolar disorder is related to enhanced processing of positive stimuli, on both cognitive measures (Johnson et al., 2000, 2005) and measures of psychophysiological response (Sutton & Johnson, 2002). This study extends previous findings on sensitivity to positive cues to the interpersonal domain.

While the ability to recognize subtle happiness in people’s faces could be advantageous in social situations (such as being more sensitive to approach cues given by a shy person), it may also be indicative of a problem in emotional responses to positive stimuli. For instance, findings suggest that mania-vulnerable people show grandiose expectations after success (Johnson et al., 2005; Meyer & Krumm-Merabet, 2003), believe they can predict the outcomes of chance events after success (Stern & Berrenberg, 1979), have a hyper-positive sense of self (Lam, Wright, & Sham, 2005), and set unrealistically high life goals (Johnson & Carver, 2006). Thus, a hyper-awareness of positive cues could produce adverse social consequences, such as overconfident approach behaviors toward persons who may not have invited such an advance. More research is needed to understand whether facial affect sensitivity plays a role in the social impairments within bipolar disorder.

The fact that this effect emerged only with very low intensity facial expressions may provide an additional angle of approach to this field. Given that most research in this area has used high-intensity expressions as stimuli, our study suggests that differences in facial affect recognition within this group may be subtle enough to mandate the use of multiple-intensity stimuli. This methodological need may be particularly important given that higher-intensity expressions of happiness appear to be almost universally recognizable.

In sum, these results suggest that people with a higher risk for mania show a unique adeptness in their ability to detect subtle expressions of happiness when they themselves are happy. Future research will be needed to better understand the role of mood state, clinical severity, and history of stigma as influences on affective sensitivity. It will also be important to examine whether the patterns observed here have implications for social functioning and goal pursuit. Such research may indicate a direction for new prevention approaches.

Acknowledgments

We thank Marcella Coutts for assistance in data collection, as well as Jutta Joormann and S. T. Calvin for suggestions during study development.

Footnotes

Preliminary analyses suggested that levels of alertness, nervousness, and sadness were unrelated to facial affect recognition accuracy, both across all participants and in interaction with the HPS

References

- Addington J, Addington D. Facial affect recognition and information processing in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Schizophrenia Research. 1998;32:171–181. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(98)00042-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altman EG, Hedeker D, Peterson JL. A comparative evaluation of three self-rating scales for acute mania. Biological Psychiatry. 2001;50:468–471. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(01)01065-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altman EG, Hedeker D, Peterson JL, Davis JM. The Altman Self-Rating Mania Scale. Biological Psychiatry. 1997;42:948–955. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3223(96)00548-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4. Washington, DC: Author; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Beck RW. Screening depressed patients in family practice: A rapid technique. Postgraduate Medicine. 1972;52:81–85. doi: 10.1080/00325481.1972.11713319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, Dilsaver SC. Lifetime rates of suicide attempts among subjects with bipolar and unipolar disorders relative to subjects with other axis I disorders. Biological Psychiatry. 1996;39:896–899. doi: 10.1016/0006-3223(95)00295-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickerson FB, Boronow JJ, Stallings CR, Origoni AE, Cole S, Yolken RH. Association between cognitive functioning and employment status of persons with bipolar disorder. Psychiatric Services. 2004;55:54–58. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.55.1.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eckblad M, Chapman LJ. Development and validation of a scale for hypomanic personality. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1986;95:214–222. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.95.3.214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekman P, Friesen W. Pictures of facial affect. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press; 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Foelker GA, Shewchuk RM, Nierderehe G. Confirmatory factor analysis of the short form Beck Depression Inventory in elderly community samples. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 1987;43:111–118. doi: 10.1002/1097-4679(198701)43:1<111::aid-jclp2270430118>3.0.co;2-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Getz GE. Social functioning and facial affect recognition deficits in mood disorders. Dissertation Abstracts International: Section B: The Sciences and Engineering. 2005;65:4284. [Google Scholar]

- Getz GE, Shear PK, Strakowski SM. Facial affect recognition deficits in bipolar disorder. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society. 2003;9:623–632. doi: 10.1017/S1355617703940021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg JF, Harrow M, Grossman LS. Recurrent affective syndromes in bipolar and unipolar mood disorders at follow-up. British Journal of Psychiatry. 1995;166:382–385. doi: 10.1192/bjp.166.3.382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goplerud E, Depue RA. Behavioral response to naturally occurring stress in cyclothymia and dysthymia. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1985;94:128–139. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.94.2.128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harmer CJ, Grayson L, Goodwin GM. Enhanced recognition of disgust in bipolar illness. Biological Psychiatry. 2002;51:298–304. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(01)01249-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann BU, Meyer TD. Mood fluctuations in people putatively at risk for bipolar disorder. British Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2006;45:105–110. doi: 10.1348/014466505X35317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson SL, Carver C. Extreme goal setting and vulnerability to mania among undiagnosed young adults. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2006;30:377–395. doi: 10.1007/s10608-006-9044-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson SL, Gruber JL, Eisner LR. Emotion and bipolar disorder. In: Rottenberg J, Johnson SL, editors. Emotion and psychopathology. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2007. pp. 123–150. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson SL, Ruggero C, Carver CS. Cognitive, behavioral, and affective responses to reward: Links with hypomanic symptoms. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology. 2005;24:894–906. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson SL, Sandrow D, Meyer B, Winters R, Miller I, Keitner G, et al. Increases in manic symptoms following life events involving goal attainment. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2000;109:721–727. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.109.4.721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krumm Merabet C, Meyer TD. Leisure activities, alcohol, and nicotine consumption in people with a hypomanic/hyperthymic temperament. Personality and Individual Differences. 2005;38:701–712. [Google Scholar]

- Kwapil TR, Miller MB, Zinser MC, Chapman LJ, Chapman J, Eckblad M. A longitudinal study of high scorers on the Hypomanic Personality Scale. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2000;109:222–226. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lam D, Wright K, Sham P. Sense of hyper-positive self and response to cognitive therapy in bipolar disorder. Psychological Medicine. 2005;35:69–77. doi: 10.1017/s0033291704002910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence JW, Carver CS, Sheier MF. Velocity toward goal attainment in immediate experience as a determinant of affect. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 2002;32:788–802. [Google Scholar]

- Lembke A, Ketter TA. Impaired recognition of facial emotion in mania. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2002;159:302–304. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.2.302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Love AW, Grabsch B, Clarke DM. Screening for depression in women with metastatic breast cancer: A comparison of the Beck Depression Inventory Short Form and the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 2004;38:526–531. doi: 10.1080/j.1440-1614.2004.01385.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovejoy MC, Steuerwald BL. Subsyndromal unipolar and bipolar disorders: Comparisons on positive and negative affect. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1995;104:381–384. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.104.2.381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luty J, O’Gara C. Validation of the 13-Item Beck Depression Inventory in alcohol-dependent people. International Journal of Psychiatry in Clinical Practice. 2006;10:45–51. doi: 10.1080/13651500500410117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClure EB, Pope K, Hoberman AJ, Pine DS, Leibenluft E. Facial expression recognition in adolescents with mood and anxiety disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2003;160:1172–1174. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.6.1172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer B, Johnson SL, Carver CS. Exploring Behavioral Activation and Inhibition sensitivities among college students at risk for mood disorders. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment. 1999;21:275–292. doi: 10.1023/A:1022119414440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer TD. Screening for bipolar disorders using the Hypomanic Personality Scale. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2003;75:149–154. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(02)00042-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer TD, Krumm-Merabet C. Academic performance and expectations for the future in relation to a vulnerability marker for bipolar disorders: The hypomanic temperament. Personality and Individual Differences. 2003;35:785–796. [Google Scholar]

- Phillips ML, Drevets WC, Rauch SL, Lane R. Neurobiology of emotion perception I: The neural basis of normal emotion perception. Biological Psychiatry. 2003a;54:504–514. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(03)00168-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips ML, Drevets WC, Rauch SL, Lane R. Neurobiology of emotion perception II: Implications for major psychiatric disorders. Biological Psychiatry. 2003b;54:515–528. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(03)00171-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollak SD, Sinha P. Effects of early experience on children’s recognition of facial displays of emotion. Developmental Psychology. 2002;38:784–791. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.38.5.784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rawlings D, Georgiou G. Relating the components of figure preference to the components of hypomania. Creativity Research Journal. 2004;16:49–57. [Google Scholar]

- Ruggero C, Johnson SL. Reactivity to a laboratory stressor among individuals with bipolar I disorder in full or partial remission. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2006;115:539–544. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.115.3.539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stern GS, Berrenberg JL. Skill-set, success outcome, and mania as determinants of the illusion of control. Journal of Research in Personality. 1979;13:206–220. [Google Scholar]

- Strakowski SM, Keck PE, Jr, McElroy SL, West SA, Sax KW, Hawkins JM, et al. Twelve-month outcomes after a first hospitalization for affective psychosis. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1998;55:49–55. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.55.1.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutton SK, Johnson SJ. Hypomanic tendencies predict lower startle magnitudes during pleasant pictures. Psychophysiology. 2002;39(suppl):S80. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas J, Bentall RP. Hypomanic traits and response styles to depression. British Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2002;41:309–313. doi: 10.1348/014466502760379154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tohen M, Hennen J, Zarate CM, Jr, Baldessarini RJ, Strakowski SM, Stoll AL, et al. Two-year syndromal and functional recovery in 219 cases of first-episode major affective disorder with psychotic features. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2000;157:220–228. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.2.220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Gorp W, Altshuler L, Theberge DC, Wilkins J, Dixon W. Cognitive impairment in euthymic bipolar patients with and without prior alcohol dependence. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1998;55:41–46. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.55.1.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young A, Perrett D, Calder A, Sprengelmeyer R, Ekman P. Facial Expressions of Emotion – Stimuli and Tests (FEEST) Bury St. Edmunds, UK: Thames Valley Test Company; 2002. [Google Scholar]