Abstract

Mature T helper type 1 (Th1) and Th2 cells antagonize the development of the opposing subset to sustain lineage-specific responses. However, the recent identification of a third distinct subset of helper T cells – the Th17 lineage – collapses the established Th1/Th2 dichotomy and raises intriguing questions about T-cell fate. In this review, we discuss the Th17 subset in the context of the effector and regulatory T-cell lineages. Initial studies suggested reciprocal developmental pathways between Th17/Th1 subsets and between Th17/regulatory T-cell subsets, and identified multiple mechanisms by which Th1 and Th2 cells antagonize the generation of Th17 cells. However, recent observations reveal the susceptibility of differentiated Th17 cells to Th1 polarization and the enhancement of Th17 memory cells by the Th1 factors interferon-γ and T-bet. In addition, new data indicate late-stage plasticity of a subpopulation of regulatory T cells, which can be selectively induced to adopt a Th17 phenotype. Elucidating the mechanisms that undermine cross-lineage suppression and facilitate these phenotype shifts will not only clarify the flexibility of T-cell differentiation, but may also shed insight into the pathogenesis of autoimmunity and cancer. Furthermore, understanding these phenomena will be critical for the design of immunotherapy that seeks to disrupt lineage-specific T-cell responses and may suggest ways to manipulate the balance between pathogenic and regulatory lymphocytes for the restoration of homeostasis.

Keywords: autoimmunity, inflammation, regulatory T cells, T cells

Introduction

Helper (CD4+) T cells have traditionally been classified into one of two subsets based upon their cytokine profiles and transcriptional regulators. T helper type 1 (Th1) cells, considered mediators of cellular immunity, are characterized by the transcriptional factor T-bet and expression of interferon-γ (IFN-γ) and interleukin-2 (IL-2). By contrast, mediators of humoral immunity, Th2 cells are distinguished by the transcription factor GATA-3 and a unique set of cytokines, including IL-4, IL-5 and IL-13. A third lineage of CD4+ T cells complements the Th1/Th2 paradigm and develops along an induction pattern distinct from those required to elicit Th1 or Th2 responses. These T regulatory cells (Tregs) are identified according to their high expression of CD25 and low surface level of CD127 in addition to transcriptional factor forkhead box P3 (Foxp3). Suppressors of activated T-cell expansion, Tregs are considered key regulators of adaptive immunity that mediate self-tolerance. Recently another subset of helper T cells has been identified, and these Th17 cells collapse the long-accepted Th1/Th2/Treg paradigm. Although some evidence suggests that it may account for just a fraction of the pro-inflammatory cytokine IL-17 in vivo, the Th17 lineage has gained wide acceptance as a distinct subset of CD4+ T cells associated with retinoic acid receptor-related orphan receptor (ROR) and signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3) transcriptional factors in addition to an extensive network of pro-inflammatory cytokines, including IL-17, IL-6, IL-1 and IL-23. Inter-lineage antagonism mediated by terminally differentiated CD4+ T cells on naive precursors is thought to sustain lineage-specific responses observed during host defence to different classes of infection. However, recent studies contextualizing Th17 cells in the T-cell repertoire highlight a surprising degree of developmental convergence and late-stage plasticity with particular relevance for autoimmune and cancer therapies.

Th17 and Th1 lineages

First considered developmentally related and later mutually antagonistic, the relationship between Th1 and Th17 cells remains incompletely elucidated. Initially it was proposed that IL-17 production characterized an inflammatory subset of the Th1 lineage.1 Although subsequent studies put forth the idea that IL-17+ T cells and Th1 cells represent distinct populations with discrete phenotypes,2 the notion of their developmental relatedness persisted.3–5 In particular, the identification of a common subunit between IL-12 and IL-23, cytokines associated with the development of Th1 and Th17 cells, respectively, in addition to a constitutively expressed subunit shared between their receptors raises the possibility of common Th1/Th17 precursors. However, as transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) was increasingly attributed an essential role in Th17 induction, the emerging model posited developmental relatedness between Th17 cells and Tregs rather than Th1 cells.6,7 Subsequent studies have supported a paradigm in which the Th1 and Th17 lineages are not only distinct but also mutually antagonistic. Expression of the Th1 master regulator T-bet is implicated in ablation of the Th17 response and its absence inhibits Th1 polarization of CD4+ T cells.8,9 Furthermore, activation of STAT1 by IFN-γ can suppress Th17 development by antagonizing STAT3, a positive regulator of Th17 cells.10–12 The loss of this suppression during T-bet or IFN-γ deficiency is thought to be responsible for the more severe aetiology experienced by mice with experimental forms of autoimmunity. A recent study suggests that this lineage antagonism is bilateral. In the presence of antigen-presenting cells (APC) and ovalbumin peptides, IL-12 enhances Th1 polarization markedly more in T cells derived from IL-17−/− mice than in their wild-type counterparts, suggesting that IL-17 impedes Th1 development during T-cell priming.2

However, the identification of T cells that are double positive for IFN-γ and IL-17 complicates this relationship. When CD4+ T cells are stimulated under Th17 polarizing conditions, IFN-γ+ IL-17+ T cells can account for a significant fraction of all IL-17+ T cells generated.13,14 Whether these double-positive cells represent a subset of cells in a transient stage of Th1 development or a more permanent subpopulation derived from a distinct but unknown differentiation programme remains unclear, but recent data suggest that the former accounts at least in part for the IFN-γ+ IL-17+ subpopulation. However, in contrast to earlier suppositions of a common intermediate between naive T cells and fully differentiated Th1 or Th17 cells, these studies indicate that the lineages are connected after preliminary Th17 differentiation. Interleukin-17-producing T cells that are either expanded or generated in vitro are susceptible to Th1 (but not Th2) polarization, a phenotype shift facilitated by the low but constitutive expression of IL-12 receptor β2 by Th17 cells.15,16 Stimulation by IL-12 rapidly down-regulates IL-17 production and induces expression of IFN-γ, a process that is diminished but not halted by the addition of exogenous TGF-β.16,17 Strikingly, Lee et al.16 suggest that barring the synergy between exogenous TGF-β and IL-23, this phenotype shift from Th17 to Th1 is inevitable and occurs not only in the presence of IL-12, but also during stimulation by antigen or IL-23 alone. The extent to which the unstable cytokine memory of Th17 cells is an artefact of in vitro culturing is controversial,16 but this apparent plasticity of the Th17 lineage may account for the existence of IFN-γ+ IL-17+ T cells in human tissue.15 Indeed, some cells with a Th17 signature may be in an intermediate state of an unconventional route of Th1 development.

Furthermore, mutual antagonism between the Th1 and Th17 lineages seems inconsistent with the co-localization of inflammatory Th17 and Th1 cells in autoimmune settings.18–21 A recent study by Kryczek et al.22 may offer a partial solution to this apparent paradox: IFN-γ conditioning enhances the capacity of APC to drive the expansion of memory Th17 cells but not the commitment of naive CD4+ T cells to the Th17 lineage. The same study demonstrates that IFN-γ diminishes Th1 polarization by up-regulating co-stimulatory molecule B7-H1 (PD-L1) on APC. Hence, modification of APC expression may be a mechanism by which IFN-γ creates a local environment conducive to the Th17 lineage, and in particular, to Th17 memory cells. Recent studies support this idea. Incubation with IFN-γ significantly induces expression of IL-23, IL-1 and CCL20 in myeloid APC from both healthy individuals and patients with psoriasis, driving differentiated T cells to up-regulate IL-17 and providing a mechanism for their trafficking into inflamed tissues.19 Analysis of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE) induction complicates the Th1–Th17 relationship; myelin-specific T cells induce EAE when stimulated by Th17-stabilizing (IL-1β and IL-23) but not Th17-differentiating (IL-6, TGF-β) conditions. Although these autoreactive T cells are composed of Th1, Th17 and IFN-γ+ IL-17+ T cells at the time of adoptive transfer, the encephalitogenicity of all subpopulations appears to hinge on the expression of T-bet.13 In support of this claim, silencing of T-bet limits the differentiation of both autoreactive Th1 cells and pathogenic Th17 cells by direct inhibition of IL-23 receptor.23 Although a more broadly regulatory role is supported for IFN-γ and T-bet,18,24,25 these studies elucidate novel mechanisms by which inflammatory Th17 cells may circumvent Th1 regulation and synergize with local Th1 cells in autoimmune settings.

Synergy between these lineages may also support host defence (see review ref. 26), and some evidence suggests that the early Th17 response can facilitate the recruitment of Th1 cells to sites of infection and promote the development of Th1 memory.27 However, other studies suggest that the Th17 response may be redundant or even subvert Th1 immunity, particularly during infection by certain intracellular bacteria and fungal pathogens.28,29 The relationship between these subsets during protective immunity remains controversial, and even for similar pathogens, defining the trends that govern their interplay is crippled by the variation in inoculation routes, infection dosages and sites of infection. As a result, the view that the Th1 and Th17 lineages are discrete and mutually antagonistic is complicated by the susceptibility of differentiated Th17 cells to Th1 polarization, the enhancement of Th17 memory cells by the Th1 factors IFN-γ and T-bet, and the synergy between these lineages during infection.

Th17 and Treg lineages

Initial studies highlighting the importance of TGF-β in the induction of the Th17 lineage indicated that these cells might be developmentally related to Tregs. According to one model, the combination of TGF-β and IL-6 causes uncommitted progenitors to adopt a Th17 signature, while TGF-β alone skews precursors towards the Treg lineage.7 The TGF-β signalling causes these common precursors to pass through an intermediate stage characterized by the co-expression of Foxp3 and ROR-γt.30 One physiological mechanism that yields the unique combination of IL-6 and TGF-β is the activation of dendritic cells through phagocytosis of infected, apoptotic leucocytes.31 Although alternative Th17 differentiation pathways do not hinge on the presence of TGF-β and IL-6, other molecules that reciprocally regulate these lineages have been identified. The diverging effects of IL-1β and IL-2 reinforce this notion of reciprocity. Interleukin-2 inhibits the development of Th17 cells32,33 (but not other helper subsets34), whereas it is implicated in the survival of mature Tregs in the periphery.32,35,36 Interleukin-1β kinetically subverts the IL-2-driven inhibition.32 At high concentrations, the vitamin A metabolite retinoic acid impedes Th17 differentiation while facilitating the expansion of the Treg lineage,37–40 a phenomenon with physiological relevance for intestinal lamina propria and the gut-associated lymphoid tissues.41,42 The aryl hydrocarbon receptor (Ahr) has also been implicated in the regulation of reciprocal Treg and Th17 populations, but its influence is complicated by the differential effects of distinct Ahr ligands.43 Reciprocal regulation is driven not only by exogenous and cytoplasmic effectors but exists at the transcriptional level as well: Foxp3 protein physically interferes with the association between ROR-γt and the IL-17 promoter.30,44,45 Identification of other factors that reciprocally regulate these lineages may shed light on the mechanisms by which the Treg–Th17 balance is deleteriously skewed towards the former in cancerous lesions and the latter in autoimmune tissues.

However, recent reports of late-stage Treg plasticity complicate the established belief in their mutually antagonistic and reciprocal nature. In addition to supporting Th17 differentiation from effector T cells through the provision of TGF-β, a phenomenon markedly enhanced in the presence of IL-6,46 both murine and human Tregs have been shown to adopt a Th17-like phenotype upon activation in an inflammatory cytokine milieu.47,48 In the presence of IL-6, mitogenic activation induces a fraction of murine CD25+ Foxp3+ Tregs to express IL-17.46,47,49 Among APC, dendritic cells have been identified for their capacity to facilitate this conversion following stimulation by antigen or blockade of tryptophan depletion, a mechanism of immunosuppression particularly prominent in tumour pathology.46,49–51 Depending on the mode of stimulation, this induction can be accompanied by loss of Foxp3 expression and suppressive capacity along with enhanced proliferation.47,50 However, inducible Tregs generated from murine naive T cells resist this phenotype shift, while pretreatment with exogenous IL-2 and TGF-β renders otherwise susceptible natural Tregs resistant.50

A similar phenomenon has been documented in human studies, which have focused less on mechanisms of induction and more on characterizing the Treg subsets capable of undergoing this phenotype shift. In particular, memory Tregs (CD4+ Foxp3+ CD25high CD27+ CD45RA−) characterized by the expression of the Th17-associated chemokine receptor CCR6 have been implicated,48,52 although whether CCR6 expression stringently defines the subset of convertible Tregs remains unclear.53 In contrast to the susceptibility of murine thymic Tregs to Th17-conversion, human Tregs extracted from the thymus cannot be induced to secrete IL-17, suggesting that the ability to produce IL-17 is acquired in the periphery.52 Although the extent to which IL-17 production triggers the concomitant loss of Foxp3 expression and suppressive capacity remains unclear,52,53 a nuance detected by Beriou et al.54 may resolve this dilemma: loss of Treg characteristics occurs once IL-17 is not just expressed intracellularly but actively secreted as well, a decision determined by the strength of the activation stimulus. Both mitogenic activation via phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate/ionomycin and stimulation by APC (CD14+ monocytes in particular) have been demonstrated as suitable stimuli, and addition of exogenous IL-1β, IL-6, IL-23 and IL-21 enhances the epigenetic modification that gives rise to this phenotype shift.52,53

As Treg therapy is increasingly hailed as a potential treatment for autoimmune conditions in which the Treg population is diminished or defective, further elucidation of this Treg-to-Th17 phenotype shift will be essential. Indeed, adoptive transfer of natural Tregs pretreated with IL-6 does not confer protection on mice with a chronic lupus-like syndrome50 and administration of Tregs stimulated by pre-activated dendritic cells induces pathology in a murine model of diabetes.47 On the other hand, this phenotype shift may lend itself to the development of a substitute therapy for Treg depletion in the context of tumour immunology. Forced conversion of mature Tregs to a Th17-like phenotype in the tumour-draining lymph nodes of mice with B16-ovalbumin tumours attenuates pathology.51 Therefore, defining the subset of Tregs resistant to Th17 conversion and the mechanisms that induce this subset to produce IL-17 may emerge as crucial considerations in the context of Treg therapy.

Th17 and Th2 lineages

In contrast to the aforementioned cases, there is no evidence for late-stage conversion or developmental relatedness between the Th2 and Th17 lineages. On the other hand, several mechanisms by which the Th2 lineage antagonizes the Th17 axis have been identified. Forced expression of GATA-3, the principal Th2 transcription factor, inhibits IL-17 production during early differentiation through mechanisms that are partially dependent on IL-4. These include the down-regulation of Th17-promoting transcription factors, including STAT3, STAT4 and RORγt.55 Interleukin-4 blockade in combination with anti-IFN-γ enhances Th17 differentiation, whereas addition of exogenous IL-4 inhibits IL-23-induced IL-17 production from memory T cells, although mitogen-induced IL-17 production is not inhibited.56 A member of the IL-17 family, IL-25, drives the Th2 response and suppresses the Th17 lineage through the induction of Th2-associated IL-13.57 This IL-13 in turn can suppress dendritic cell expression of IL-23, IL-1 and IL-6 and exert direct suppressive effects on Th17 cells, which, unlike other helper T cells, express IL-13 receptor.57,58 However, compared with the Th1 cytokines, the Th2 response antagonizes the Th17 lineage less potently. For example, exogenous IL-2 suppresses Th17 differentiation more effectively than IL-4.55 Furthermore, GATA-3 has been ascribed some Th17-stimulatory potential: it reduces the expression of IL-2, STAT1 and suppressor of cytokine signalling 3, thereby countering the suppressive effects of the Th1 lineage on Th17 cells.55 No lineage-specific mechanisms by which Th17 cells suppress Th2 development have been elucidated; therefore antagonism between these lineages may be predominantly unidirectional rather than mutual.

Such antagonism appears particularly relevant in the context of Th17-mediated autoimmunity. Parasitic helminths, which imprint a predominantly Th2 signature on the T-cell repertoire, down-regulate the Th17 axis and reduce inflammatory pathology when infection is coupled with autoimmunity. Changes in the Th2 and Th17 responses occur concurrently with suppression of the Th1 lineage and expansion of the alternatively activated macrophage and Treg populations, making it hard to assess the relative contribution of each phenotypic change to reduced disease severity.59–62 However, some evidence suggests that IL-4-driven and IL-10-driven inhibition of the Th17 response is particularly crucial for attenuating autoimmune pathology.63 This may partially account for the inverse correlation between incidences of parasitic infection and autoimmunity, and may also suggest novel therapeutic approaches.64 Indeed, forced expression of GATA-3 and administration of exogenous IL-25 separately reduce disease severity in EAE by constraining Th17 pathology.55,57 Similarly, GATA-3 transgenic mice exhibit reduced joint destruction in a model of experimental arthritis in which dramatically increased Th2 cytokine expression accompanies reduced systemic and synovial IL-17+ and IL-17+ IFN-γ+ T cells (with little impact on traditional Th1 cells or Tregs65).

Although skewing the T-cell response towards the Th2 lineage may be a candidate for autoimmune therapy, a more complex lineage relationship emerges in the context of asthma. The Th17 response has recently been implicated in the neutrophil influx associated with acute airway hypersensitivity,66,67 a domain classically associated with the Th2 response.68 Reports diverge on whether IL-17 and IL-23 support or attenuate Th2-mediated eosinophil recruitment, suggesting a potentially biphasic role for these cytokines during different disease states.66,69,70 Clarifying mechanisms by which concurrent Th2 and Th17 activation circumvents lineage antagonism to mediate pathology may have implications for immunotherapy targeting both chronic airway inflammation and Th17-mediated autoimmune diseases.

Conclusion

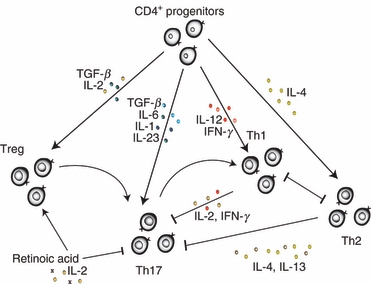

Although the discovery of the Th17 axis collapsed the long-held Th1/Th2 dichotomy, recent findings caution against remoulding the T effector paradigm to encompass three rigid pillars of helper T-cell fate (Fig. 1). The Th17 subset has gained wide acceptance as a distinct class of lymphocytes, but the heterogeneity and plasticity of this subset demand nuanced characterizations of their relationship with other T-cell populations. Antagonistic mechanisms have been identified that sustain lineage-specific responses at the transcriptional and protein levels, allowing mature effector T cells to preclude the concurrent development of other T-cell lineages. However, recent studies demonstrate considerable flexibility in T-cell fate. Whether late-stage plasticity is a natural phenomenon during homeostasis or whether defective lineage antagonism accounts for autoimmune and cancer pathology remains unclear. Thus, unravelling the complex relationships among the T effector and Treg lineages may provide critical insight into the disruption of homeostasis and may suggest novel therapeutic targets for cancer and autoimmune diseases.

Figure 1.

Schematic of T-cell lineage development from CD4+ progenitors. The composition of the local cytokine milieu biases naive CD4+ progenitors towards distinct lineages of T-cell fate. Differentiated T cells antagonize the development of other lineages from uncommitted progenitors to maintain lineage-specific responses. However, evidence indicates that late-stage plasticity enables mature regulatory T cells (Tregs) and T helper type 1 7 (Th17) cells to adopt a Th17 and Th1 profile, respectively. IFN-γ, inteferon-γ; IL-2 interleukin; TGF-β, transforming growth factor-β.

Glossary

Abbreviations:

- APC

antigen-presenting cells

- EAE

experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis

- Foxp3

forkhead box p3

- IFN-γ

interferon-γ

- IL

interleukin

- ROR

retinoic-acid related orphan receptor

- STAT

signal transducer and activator of transcription

- TGF-β

transforming growth factor-β

- Th

T helper

- Treg

regulatory T cell

References

- 1.Aarvak T, Chabaud M, Miossec P, Natvig JB. IL-17 is produced by some proinflammatory Th1/Th0 cells but not by Th2 cells. J Immunol. 1999;162:1246–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nakae S, Iwakura Y, Suto H, Galli SJ. Phenotypic differences between Th1 and Th17 cells and negative regulation of Th1 cell differentiation by IL-17. J Leukoc Biol. 2007;81:1258–68. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1006610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bettelli E, Kuchroo VK. IL-12- and IL-23-induced T helper cell subsets: birds of the same feather flock together. J Exp Med. 2005;201:169–71. doi: 10.1084/jem.20042279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Oppmann B, Lesley R, Blom B, et al. Novel p19 protein engages IL-12p40 to form a cytokine, IL-23, with biological activities similar as well as distinct from IL-12. Immunity. 2000;13:715–25. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)00070-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Parham C, Chirica M, Timans J, et al. A receptor for the heterodimeric cytokine IL-23 is composed of IL-12Rbeta1 and a novel cytokine receptor subunit, IL-23R. J Immunol. 2002;168:5699–708. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.11.5699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Veldhoen M, Hocking RJ, Atkins CJ, Locksley RM, Stockinger B. TGFbeta in the context of an inflammatory cytokine milieu supports de novo differentiation of IL-17-producing T cells. Immunity. 2006;24:179–89. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bettelli E, Carrier Y, Gao W, Korn T, Strom TB, Oukka M, Weiner HL, Kuchroo VK. Reciprocal developmental pathways for the generation of pathogenic effector TH17 and regulatory T cells. Nature. 2006;441:235–8. doi: 10.1038/nature04753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yang Y, Xu J, Niu Y, Bromberg JS, Ding Y. T-bet and eomesodermin play critical roles in directing T cell differentiation to Th1 versus Th17. J Immunol. 2008;181:8700–10. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.12.8700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Guo S, Cobb D, Smeltz RB. T-bet inhibits the in vivo differentiation of parasite-specific CD4+ Th17 cells in a T cell-intrinsic manner. J Immunol. 2009;182:6179–86. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0803821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nishihara M, Ogura H, Ueda N, et al. IL-6-gp130-STAT3 in T cells directs the development of IL-17+ Th with a minimum effect on that of Treg in the steady state. Int Immunol. 2007;19:695–702. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxm045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yang XO, Panopoulos AD, Nurieva R, Chang SH, Wang D, Watowich SS, Dong C. STAT3 regulates cytokine-mediated generation of inflammatory helper T cells. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:9358–63. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C600321200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tanaka K, Ichiyama K, Hashimoto M, et al. Loss of suppressor of cytokine signaling 1 in helper T cells leads to defective Th17 differentiation by enhancing antagonistic effects of IFN-gamma on STAT3 and Smads. J Immunol. 2008;180:3746–56. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.6.3746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yang Y, Weiner J, Liu Y, et al. T-bet is essential for encephalitogenicity of both Th1 and Th17 cells. J Exp Med. 2009;206:1549–64. doi: 10.1084/jem.20082584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Evans HG, Suddason T, Jackson I, Taams LS, Lord GM. Optimal induction of T helper 17 cells in humans requires T cell receptor ligation in the context of Toll-like receptor-activated monocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:17034–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0708426104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Annunziato F, Cosmi L, Santarlasci V, et al. Phenotypic and functional features of human Th17 cells. J Exp Med. 2007;204:1849–61. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee YK, Turner H, Maynard CL, Oliver JR, Chen D, Elson CO, Weaver CT. Late developmental plasticity in the T helper 17 lineage. Immunity. 2009;30:92–107. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lexberg MH, Taubner A, Forster A, Albrecht I, Richter A, Kamradt T, Radbruch A, Chang HD. Th memory for interleukin-17 expression is stable in vivo. Eur J Immunol. 2008;38:2654–64. doi: 10.1002/eji.200838541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nakagome K, Okunishi K, Imamura M, et al. IFN-γ attenuates antigen-induced overall immune response in the airway as a Th1-type immune regulatory cytokine. J Immunol. 2009;183:209–20. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0802712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kryczek I, Bruce AT, Gudjonsson JE, et al. Induction of IL-17+ T cell trafficking and development by IFN-γ: mechanism and pathological relevance in psoriasis. J Immunol. 2008;181:4733–41. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.7.4733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pene J, Chevalier S, Preisser L, et al. Chronically inflamed human tissues are infiltrated by highly differentiated Th17 lymphocytes. J Immunol. 2008;180:7423–30. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.11.7423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cox CA, Shi G, Yin H, Vistica BP, Wawrousek EF, Chan CC, Gery I. Both Th1 and Th17 are immunopathogenic but differ in other key biological activities. J Immunol. 2008;180:7414–22. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.11.7414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kryczek I, Wei S, Gong W, et al. Cutting edge: IFN-gamma enables APC to promote memory Th17 and abate Th1 cell development. J Immunol. 2008;181:5842–6. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.9.5842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gocke AR, Cravens PD, Ben LH, Hussain RZ, Northrop SC, Racke MK, Lovett-Racke AE. T-bet regulates the fate of Th1 and Th17 lymphocytes in autoimmunity. J Immunol. 2007;178:1341–8. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.3.1341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lohr J, Knoechel B, Wang JJ, Villarino AV, Abbas AK. Role of IL-17 and regulatory T lymphocytes in a systemic autoimmune disease. J Exp Med. 2006;203:2785–91. doi: 10.1084/jem.20061341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rangachari M, Mauermann N, Marty RR, Dirnhofer S, Kurrer MO, Komnenovic V, Penninger JM, Eriksson U. T-bet negatively regulates autoimmune myocarditis by suppressing local production of interleukin 17. J Exp Med. 2006;203:2009–19. doi: 10.1084/jem.20052222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Meredith MC, Sing Sing W. Interleukin-17 in host defence against bacterial, mycobacterial and fungal pathogens. Immunology. 2009;126:177–85. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2008.03017.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Khader SA, Bell GK, Pearl JE, et al. IL-23 and IL-17 in the establishment of protective pulmonary CD4+ T cell responses after vaccination and during Mycobacterium tuberculosis challenge. Nat Immunol. 2007;8:369–77. doi: 10.1038/ni1449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Orgun NN, Mathis MA, Wilson CB, Way SS. Deviation from a strong Th1-dominated to a modest Th17-dominated CD4 T cell response in the absence of IL-12p40 and type I IFNs sustains protective CD8 T cells. J Immunol. 2008;180:4109–15. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.6.4109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bozza S, Clavaud C, Giovannini G, et al. Immune sensing of Aspergillus fumigatus proteins, glycolipids, and polysaccharides and the impact on Th immunity and vaccination. J Immunol. 2009;183:2407–14. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0900961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhou L, Lopes JE, Chong MM, et al. TGF-beta-induced Foxp3 inhibits T(H)17 cell differentiation by antagonizing RORγt function. Nature. 2008;453:236–40. doi: 10.1038/nature06878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Torchinsky MB, Garaude J, Martin AP, Blander JM. Innate immune recognition of infected apoptotic cells directs T(H)17 cell differentiation. Nature. 2009;458:78–82. doi: 10.1038/nature07781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kryczek I, Wei S, Vatan L, Escara-Wilke J, Szeliga W, Keller ET, Zou W. Cutting edge: opposite effects of IL-1 and IL-2 on the regulation of IL-17+ T cell pool IL-1 subverts IL-2-mediated suppression. J Immunol. 2007;179:1423–6. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.3.1423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kryczek I, Wei S, Zou L, Altuwaijri S, Szeliga W, Kolls J, Chang A, Zou W. Cutting edge: Th17 and regulatory T cell dynamics and the regulation by IL-2 in the tumor microenvironment. J Immunol. 2007;178:6730–3. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.11.6730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cote-Sierra J, Foucras G, Guo L, Chiodetti L, Young HA, Hu-Li J, Zhu J, Paul WE. Interleukin 2 plays a central role in Th2 differentiation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:3880–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400339101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.D’Cruz LM, Klein L. Development and function of agonist-induced CD25+Foxp3+ regulatory T cells in the absence of interleukin 2 signaling. Nat Immunol. 2005;6:1152–9. doi: 10.1038/ni1264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fontenot JD, Rasmussen JP, Gavin MA, Rudensky AY. A function for interleukin 2 in Foxp3-expressing regulatory T cells. Nat Immunol. 2005;6:1142–51. doi: 10.1038/ni1263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Xiao S, Jin H, Korn T, Liu SM, Oukka M, Lim B, Kuchroo VK. Retinoic acid increases Foxp3+ regulatory T cells and inhibits development of Th17 cells by enhancing TGF-beta-driven Smad3 signaling and inhibiting IL-6 and IL-23 receptor expression. J Immunol. 2008;181:2277–84. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.4.2277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Elias KM, Laurence A, Davidson TS, Stephens G, Kanno Y, Shevach EM, O’Shea JJ. Retinoic acid inhibits Th17 polarization and enhances FoxP3 expression through a Stat-3/Stat-5 independent signaling pathway. Blood. 2008;111:1013–20. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-06-096438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schambach F, Schupp M, Lazar MA, Reiner SL. Activation of retinoic acid receptor-alpha favours regulatory T cell induction at the expense of IL-17-secreting T helper cell differentiation. Eur J Immunol. 2007;37:2396–9. doi: 10.1002/eji.200737621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Uematsu S, Fujimoto K, Jang MH, et al. Regulation of humoral and cellular gut immunity by lamina propria dendritic cells expressing Toll-like receptor 5. Nat Immunol. 2008;9:769–76. doi: 10.1038/ni.1622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kang SG, Lim HW, Andrisani OM, Broxmeyer HE, Kim CH. Vitamin A metabolites induce gut-homing FoxP3+ regulatory T cells. J Immunol. 2007;179:3724–33. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.6.3724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Benson MJ, Pino-Lagos K, Rosemblatt M, Noelle RJ. All-trans retinoic acid mediates enhanced T reg cell growth, differentiation, and gut homing in the face of high levels of co-stimulation. J Exp Med. 2007;204:1765–74. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Quintana FJ, Basso AS, Iglesias AH, et al. Control of T(reg) and T(H)17 cell differentiation by the aryl hydrocarbon receptor. Nature. 2008;453:65–71. doi: 10.1038/nature06880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ichiyama K, Yoshida H, Wakabayashi Y, et al. Foxp3 inhibits RORγt-mediated IL-17A mRNA transcription through direct interaction with RORγt. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:17003–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M801286200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhang F, Meng G, Strober W. Interactions among the transcription factors Runx1, RORγt and Foxp3 regulate the differentiation of interleukin 17-producing T cells. Nat Immunol. 2008;9:1297–306. doi: 10.1038/ni.1663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Xu L, Kitani A, Fuss I, Strober W. Cutting edge: regulatory T cells induce CD4+CD25–Foxp3– T cells or are self-induced to become Th17 cells in the absence of exogenous TGF-beta. J Immunol. 2007;178:6725–9. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.11.6725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Radhakrishnan S, Cabrera R, Schenk EL, et al. Reprogrammed FoxP3+ T regulatory cells become IL-17+ antigen-specific autoimmune effectors in vitro and in vivo. J Immunol. 2008;181:3137–47. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.5.3137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 48.Ayyoub M, Deknuydt F, Raimbaud I, Dousset C, Leveque L, Bioley G, Valmori D. Human memory FOXP3+ Tregs secrete IL-17 ex vivo and constitutively express the T(H)17 lineage-specific transcription factor RORγt. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:8635–40. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0900621106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Osorio F, LeibundGut-Landmann S, Lochner M, Lahl K, Sparwasser T, Eberl G, Reis e Sousa C. DC activated via dectin-1 convert Treg into IL-17 producers. Eur J Immunol. 2008;38:3274–81. doi: 10.1002/eji.200838950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zheng SG, Wang J, Horwitz DA. Cutting edge: Foxp3+CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells induced by IL-2 and TGF-beta are resistant to Th17 conversion by IL-6. J Immunol. 2008;180:7112–6. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.11.7112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sharma MD, Hou DY, Liu Y, et al. Indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase controls conversion of Foxp3+ Tregs to TH17-like cells in tumor-draining lymph nodes. Blood. 2009;113:6102–11. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-12-195354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Voo KS, Wang YH, Santori FR, et al. Identification of IL-17-producing FOXP3+ regulatory T cells in humans. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:4793–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0900408106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Koenen HJ, Smeets RL, Vink PM, Van Rijssen E, Boots AM, Joosten I. Human CD25highFoxp3pos regulatory T cells differentiate into IL-17-producing cells. Blood. 2008;112:2340–52. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-01-133967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Beriou G, Costantino CM, Ashley CW, Yang L, Kuchroo VK, Baecher-Allan C, Hafler DA. IL-17-producing human peripheral regulatory T cells retain suppressive function. Blood. 2009;113:4240–9. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-10-183251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Van Hamburg JP, De Bruijn MJ, Ribeiro de Almeida C, et al. Enforced expression of GATA3 allows differentiation of IL-17-producing cells, but constrains Th17-mediated pathology. Eur J Immunol. 2008;38:2573–86. doi: 10.1002/eji.200737840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Park H, Li Z, Yang XO, et al. A distinct lineage of CD4 T cells regulates tissue inflammation by producing interleukin 17. Nat Immunol. 2005;6:1133–41. doi: 10.1038/ni1261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kleinschek MA, Owyang AM, Joyce-Shaikh B, et al. IL-25 regulates Th17 function in autoimmune inflammation. J Exp Med. 2007;204:161–70. doi: 10.1084/jem.20061738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Newcomb DC, Zhou W, Moore ML, Goleniewska K, Hershey GK, Kolls JK, Peebles RS., Jr A functional IL-13 receptor is expressed on polarized murine CD4+ Th17 cells and IL-13 signaling attenuates Th17 cytokine production. J Immunol. 2009;182:5317–21. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0803868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bazzone LE, Smith PM, Rutitzky LI, et al. Coinfection with the intestinal nematode Heligmosomoides polygyrus markedly reduces hepatic egg-induced immunopathology and proinflammatory cytokines in mouse models of severe schistosomiasis. Infect Immun. 2008;76:5164–72. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00673-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Reece JJ, Siracusa MC, Southard TL, Brayton CF, Urban JF, Jr, Scott AL. Hookworm-induced persistent changes to the immunological environment of the lung. Infect Immun. 2008;76:3511–24. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00192-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Nathalie ER, Benedicte YDW, Joris GDM, et al. Therapeutic potential of helminth soluble proteins in TNBS-induced colitis in mice. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2009;15:491–500. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Walsh KP, Brady MT, Finlay CM, Boon L, Mills KHG. Infection with a helminth parasite attenuates autoimmunity through TGF-β-mediated suppression of Th17 and Th1 responses. J Immunol. 2009;183:1577–86. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0803803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Elliott DE, Metwali A, Leung J, et al. Colonization with Heligmosomoides polygyrus suppresses mucosal IL-17 production. J Immunol. 2008;181:2414–9. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.4.2414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zaccone P, Fehervari Z, Phillips JM, Dunne DW, Cooke A. Parasitic worms and inflammatory diseases. Parasite Immunol. 2006;28:515–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3024.2006.00879.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Van Hamburg JP, Mus AM, De Bruijn MJ, et al. GATA-3 protects against severe joint inflammation and bone erosion and reduces differentiation of Th17 cells during experimental arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;60:750–9. doi: 10.1002/art.24329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wakashin H, Hirose K, Iwamoto I, Nakajima H. Role of IL-23–Th17 cell axis in allergic airway inflammation. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2009;149(Suppl. 1):108–12. doi: 10.1159/000211382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Chakir J, Shannon J, Molet S, Fukakusa M, Elias J, Laviolette M, Boulet LP, Hamid Q. Airway remodeling-associated mediators in moderate to severe asthma: effect of steroids on TGF-beta, IL-11, IL-17, and type I and type III collagen expression. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2003;111:1293–8. doi: 10.1067/mai.2003.1557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Semitekolou M, Alissafi T, Aggelakopoulou M, et al. Activin-A induces regulatory T cells that suppress T helper cell immune responses and protect from allergic airway disease. J Exp Med. 2009;206:1769–85. doi: 10.1084/jem.20082603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wakashin H, Hirose K, Maezawa Y, et al. IL-23 and Th17 cells enhance Th2-cell-mediated eosinophilic airway inflammation in mice. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;178:1023–32. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200801-086OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Hellings PW, Kasran A, Liu Z, Vandekerckhove P, Wuyts A, Overbergh L, Mathieu C, Ceuppens JL. Interleukin-17 orchestrates the granulocyte influx into airways after allergen inhalation in a mouse model of allergic asthma. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2003;28:42–50. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.4832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]