Abstract

Objective

To generate evidence on the effectiveness of household-wide treatment for preventing the transmission of pediculosis capitis (head lice) in resource-poor communities.

Methods

We studied 132 children without head lice who lived in a slum in north-eastern Brazil. We randomized the households of the study participants into an intervention and a control group and prospectively calculated the incidence of infestation with head lice among the children in each group. In the intervention group, all of the children’s family members who lived in the household were treated with ivermectin; in the control group, no family member was treated. We used the χ² test with continuity correction or Fisher’s exact test to compare proportions. We performed survival analysis using Kaplan–Meier estimates with log rank testing and the Mann–Whitney U test to analyse the length of lice-free periods among sentinel children, and we used Cox regression to analyse survival data on a multivariate level. We also carried out a subgroup analysis based on gender.

Findings

Children in the intervention group remained free from infestation with head lice significantly longer than children in the control group. The median infestation-free period in the intervention group was 24 days (interquartile range, IQR: 11–45), as compared to 14 days (IQR: 11–25) in the control group (P = 0.01). Household-wide treatment with ivermectin proved significantly more effective among boys than among girls (P = 0.005). After treatment with ivermectin, the estimated number of annual episodes of head lice infestation was reduced from 19 to 14 in girls and from 15 to 5 in boys. Female sex and extreme poverty were independent risk factors associated with a shortened disease-free period.

Conclusion

In an impoverished community, girls and the poorest of the poor are the population groups that are most vulnerable for head lice infestation. To decrease the number of head lice episodes per unit of time, control measures should include the treatment of all household contacts. Mass treatment with ivermectin may reduce the incidence of head lice infestation and associated morbidity in resource-poor communities.

Résumé

Objectif

Prouver l’efficacité du traitement de l’ensemble des membres des foyers pour prévenir la transmission des poux de tête (pediculosis capitis) dans les communautés pauvres.

Méthodes

Nous avons étudié 132 enfants dépourvus de poux et vivant dans un bidonville du Nord-est du Brésil. Nous avons réparti aléatoirement les foyers des participants à l’étude entre un groupe d’intervention et un groupe témoin et nous avons calculé de manière prospective l’incidence de l’infestation par des poux de tête chez les enfants de chacun des groupes. Dans le groupe d’intervention, tous les membres de la famille des enfants vivant dans le foyer ont été traités par l’ivermectine ; dans le groupe témoin, aucun des autres membres de la famille n’a été traité. Nous avons utilisé le test du χ² avec correction de continuité ou le test de Fischer exact pour comparer les proportions d’enfants infestés. Nous avons utilisé des estimations de Kaplan-Meier avec un test de rang logarithmique pour réaliser une analyse de survie, le test de Mann-Whitney pour étudier la durée des périodes exemptes de poux chez les enfants sentinelles et la régression de Cox pour effectuer une analyse multivariée des données de survie. Nous avons également procédé à une analyse en sous-groupes en fonction du sexe.

Résultats

Les enfants appartenant au groupe d’intervention sont restés exempts de poux de tête significativement plus longtemps que les enfants du groupe témoin. La durée médiane sans infestation dans le groupe d’intervention était de 24 jours (intervalle interquartile, IIQ : 11-45), contre 14 jours (IIQ = 11-25) dans le groupe témoin (p = 0,01). Le traitement par l’ivermectine de l’ensemble des membres des foyers s’est révélé significativement plus efficace chez les garçons que chez les filles (p = 0,005). Après un traitement par l’ivermectine, le nombre annuel estimé d’épisodes d’infestation par des poux de tête avait diminué pour passer de 19 à 14 chez les filles et de 15 à 5 chez les garçons. Le sexe féminin et l’extrême pauvreté étaient des facteurs de risque indépendants associés à la brièveté des périodes sans infestation.

Conclusion

Dans une communauté pauvre, les filles et les plus pauvres parmi les pauvres sont les groupes de population les plus vulnérables à l’infestation par des poux de tête. Pour réduire le nombre d’épisodes d’infestation par des poux de tête par unité de temps, les mesures de lutte contre ces parasites doivent inclure le traitement de tous les contacts domestiques. Un traitement de masse par l’ivermectine peut faire diminuer l’incidence de cette infestation et la morbidité associée dans les communautés pauvres.

Resumen

Objetivo

Demostrar la eficacia del tratamiento de todos los miembros del domicilio para prevenir la transmisión de la pediculosis capitis en comunidades pobres.

Métodos

Estudiamos 132 niños sin pediculosis capitis que vivían en barrios de chabolas en el nordeste del Brasil. Aleatoriamente, asignamos los domicilios de los participantes en el estudio a un grupo de intervención o a un grupo de control y calculamos prospectivamente la incidencia de pediculosis capitis en los niños de uno y otro grupo. En el grupo de intervención se trataron con ivermectina todos los miembros de la familia que vivían en el mismo hogar que el niño; en el grupo de control no se trató ningún miembro de la familia. Para comparar las proporciones utilizamos la prueba de la χ² con corrección de continuidad o la prueba exacta de Fisher. Se utilizaron las estimaciones de Kaplan–Meier con prueba de rango logarítmico para analizar la supervivencia; la U de Mann–Whitney para analizar la duración de los periodos libres de pediculosis entre los niños centinela, y la regresión de Cox para efectuar un análisis multivariado de los datos sobre la supervivencia. Asimismo, realizamos un análisis de subgrupos en función del sexo.

Resultados

Los niños del grupo de intervención se mantuvieron sin pediculosis capitis durante más tiempo que los del grupo de control. La duración mediana del periodo libre de infestación fue de 24 días (intervalo intercuartílico, IIC: 11–45) en el grupo de intervención, y 14 días (IIC: 11–25) en el grupo de control (P = 0,01). El tratamiento de todos los miembros del domicilio con ivermectina fue significativamente más eficaz en los niños que en las niñas (P = 0,005). Después del tratamiento con ivermectina, el número estimado de episodios anuales de pediculosis capitis se redujo de 19 a 14 en las niñas, y de 15 a 5 en los niños. El sexo femenino y la pobreza extrema fueron factores de riesgo independientes asociados a un acortamiento del periodo libre de infestación.

Conclusión

En una comunidad pobre, las niñas y los más pobres son los grupos de población más vulnerables a la infestación por piojos. Para reducir el número de episodios de pediculosis capitis por unidad de tiempo, las medidas de control deben incluir el tratamiento de todos los contactos domésticos. El tratamiento masivo con ivermectina puede reducir la incidencia de la infestación por piojos de la cabeza y de la morbilidad asociada en comunidades con escasos recursos.

ملخص

الغرض

إظهار البينّات على فعالية المعالجة المنزلية الواسعة النطاق في توقي انتقال العدوى بقمل الرأس في المجتمعات الفقيرة الموارد.

الطريقة

درس الباحثون 132 طفلاً غير مصابين بقمل الرأس كانوا يعيشون في أحد الأحياء الفقيرة في شمال شرق البرازيل. واختار الباحثون بطريقة عشوائية المشاركين في الدراسة المنزلية والذين سيتلقون التدخل كما اختاروا مجموعة الشواهد، وقاموا بحساب معدل وقوع العدوى بقمل الرأس بين الأطفال في كل مجموعة. وفي المجموعة التي تلقت التدخل، جرى معالجة جميع أطفال الأسرة الذين يعيشون في المنزل بالإيفرمكتين؛ بينما لم يعالج أي فرد من أفراد الأسرة في مجموعة الشواهد. واستخدم الباحثون اختبار خي المربع (χ²) مع تصحيح الاستمرارية أو اختبار فيشر الدقيق (Fisher’s exact test) لمقارنة النسب بين المجموعتين. وأجرى الباحثون تحليلاً للبقاء باستخدام تقديرات كابلان-ميير (Kaplan–Meier) مع إجراء اختبار مرتبة اللوغاريتم واختبار مان-ويتني (Mann–Whitney U test) لتحليل طول فترات الخلو من الإصابة بالقمل بين الأطفال الخافرين، وأجرى الباحثون تحوف كوكس (Cox regression) لتحليل بيانات البقاء على مستوى متعدد المتغيرات. كما أجرى الباحثون تحليلاً للفئات الفرعية مستنداً إلى الجنس.

الموجودات

بقى الأطفال في المجموعة التي تلقت التدخل خالين من الإصابة بقمل الرأس لفترة أطول وعلى نحو يعتد به إحصائياً مقارنة بالأطفال في مجموعة الشواهد. وكان الوسيط الإحصائي لفترات الخلو من الإصابة بقمل الرأس في المجموعة التي تلقت التدخل هو 24 يوماً (والمدى بين الشريحتين الربعيتين interquartile: 11-45 يوماً)، مقارنة بـ 14 يوماً (والمدى بين الشريحتين الربعيتين: 11-25 يوماً) في مجموعة الشواهد (قوة الاحتمال P= 0.01). وأثبت العلاج المنزلي الواسع النطاق بالإيفرمكتين أنه أكثر فعالية وعلى نحو يعتد به إحصائياً بين الأولاد مقارنة بالبنات (قوة الاحتمال P= 0.005)، فبعد المعالجة بالإيفرمكتين، انخفض العدد التقديري للنوبات السنوية للإصابة بقمل الرأس من 19 إلى 14 بين البنات، ومن 15 إلى 5 بين الأولاد. كانت الإناث والفقر المدقع هما عاملا الخطر المستقلان المرتبطان بقصر فترات الخلو من الإصابة.

الاستنتاج

في المجتمعات الفقيرة، كانت البنات والفئات الأشد فقراً هي المجموعات السكانية الأشد تعرضاً للإصابة بقمل الرأس. ولخفض عدد نوبات الإصابة بقمل الرأس لكل وحدة زمنية، ينبغي أن تتضمن إجراءات المكافحة معالجة جميع المخالطين في المنزل. ويمكن أن تؤدي المعالجة الجماعية بالإيفرمكتين إلى خفض معدلات وقوع الإصابة بقمل الرأس والمراضة المرتبطة بها في المجتمعات الفقيرة الموارد.

Introduction

Pediculosis capitis (head lice infestation) is probably the most common parasitic condition among children worldwide. It is particularly common in resource-poor communities in the developing world, where it affects individuals of all age groups, and prevalence in the general population can be as high as 40%.1 Children aged < 12 years show the highest prevalence and bear the highest burden of disease.2–4

Despite the public health relevance of the condition, strategies to effectively control it are not evidence-based, and recurrent head lice infestations are a common problem.5,6 This is of particular concern in resource-poor communities, where this parasitic skin disease prevails and is associated with considerable morbidity.1,4,7

We assessed household-wide treatment with ivermectin as a means of controlling the transmission of head lice in a resource-poor setting based on the premise that in such settings, as opposed to more affluent ones,6,8 within-household transmission of head lice plays a crucial role in transmission dynamics. The lessons learned on head lice transmission and the usefulness of this approach for the control of this parasitic skin infestation are presented in this paper.

Methods

Study area and participants

The study was conducted during February and March 2007 in a typical favela (slum) in Fortaleza, the capital of Ceará state in north-eastern Brazil. Of the favela’s population, 60% has a monthly family income of less than two minimum wages (1 minimum wage = 200 United States dollars, US$). The unemployment rate is high, violence and drug abuse are common and adult illiteracy is about 30%.4 Health care is provided by the national primary health care system (Programa de Saúde da Família) through a primary health-care centre in the area.

Children and teenagers from 5 to 15 years of age who were free from head lice were eligible for the study. All children were participants of a clinical trial comparing two head lice treatments that had taken place immediately before this field study was initiated.9 For the clinical trial, children with head lice living in an urban slum were recruited and sent to a holiday resort where the trial took place. While still in the holiday resort but immediately before this study, children received oral ivermectin to assure that they were free of head lice by the time the field study started. In addition, baseline head lice status was assessed by vigorous wet combing, the most sensitive method for detecting head lice.10 Children were not admitted into the field study if they were (i) unwilling to participate in the trial, (ii) presumed absent from the study area for more than a week, or (iii) found to have active head lice infestation during the baseline wet combing. Patients and their parents or legal guardians gave informed written consent. In total, 132 children free from head lice (sentinel children) from 78 families were included. All participants were recruited in a single day.

Study design

We randomized the households of participating children into two groups. In the intervention group, we gave all household members 200 μg/kg of ivermectin orally. Ten days later, the same dose was given to all household members except for the sentinel children who were free of head lice. Household members of the control group remained untreated. One day after the household-wide treatment with ivermectin, sentinel children returned home from the holiday resort. They were subsequently examined for the presence of head lice by wet combing every 3 to 4 days during a period of 60 days.

Using structured questionnaires, we collected socioeconomic information on participating households. Because most people living in slums are not regularly employed and have no steady income, to measure poverty we used an index that was independent of household income but that assessed the physical characteristics of the dwelling and household consumption. To do so, housing quality (i.e. improvised dwelling, dwelling constructed of wood or adobe) was rated on a scale of 1 to 3. For electricity, access to piped water and connection to public sewage disposal, a rating of 0 was given for each if present and of 1 if not present. We summed up the ratings to obtain an overall value for each family. We stratified families into four categories, with the poorest families belonging to the highest category. To rate the degree of crowding we counted the number of people per household and divided it by the number of rooms per house.

Randomization

We randomized households using a permuted block design (block size six, allocation ratio 1:1) and a computer-generated list of random numbers.

Blinding

The study was observer-blinded. For household-wide treatment, all households allocated to the intervention group were visited by two investigators not involved in the follow-up visits (GF and FAO). The follow-up visits were performed by a different pair of investigators (DP and AK), who were blinded as to the group status of the households.

Objectives

We hypothesized that head-lice-free children belonging to families that had been treated with ivermectin would remain free of head lice infestation longer than children from households where treatment had not been administered. The trial was designed to assess the effect of household-wide treatment for head lice on transmission dynamics and its usefulness for disease control in a hyperendemic area, as well as to detect factors associated with rapid infestation.

Outcomes

The primary endpoint was the infestation-free period, defined as the number of days between the baseline examination and the first follow-up examination that was positive for head lice. A positive head lice examination was defined as one in which at least one viable head louse or nymph was detected by diagnostic wet combing – the most sensitive method for diagnosing head lice infestation.11,12 We performed additional analyses on individual characteristics (sex, length and type of hair) and household characteristics (poverty level, crowding) to look for their potential association with the length of the infestation-free period.

Sample size

Since the sentinel children were those who had participated in a therapeutic trial in January 2007, our sample size depended on the number of participants who completed that trial. However, we estimated that if only 5% of the children in the control group and 15% of those in the intervention group remained free of head lice during the observation period, we would need approximately 40 participants per group to detect a significant difference between both groups (power: 0.8; significance level: P < 0.05). The actual number of participants in the control and intervention group was 68 and 64, respectively.

Statistical analysis

For the statistical analysis we used Epi Info, version 6.04d (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, GA, United States of America) and SPSS statistical software, version 11.0.4 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). To compare proportions we used the χ² test with continuity correction or the Fisher exact test when appropriate. We used Kaplan–Meier estimates with log rank testing and the Mann–Whitney U test for survival analysis of head-lice-free periods among sentinel children. We employed a Cox regression model to analyse survival data on a multivariate level. As head lice infestation is much more frequent in girls than in boys,2,3,13,14 we also carried out a subgroup analysis for gender.

We estimated the incidence of head lice infestation by logarithmic extrapolation of the Kaplan–Meier curve. To measure the daily number of episodes of head lice infestation, we used the attack rate, defined as follows:

| number of new head lice infestations ÷ (total person − days of observation) |

The resulting rate was multiplied by 365 to estimate the number of head lice episodes per child per year.

Ethical aspects

The study was conducted in accordance with the revised declaration of Helsinki (2000). Both the participants and their respective legal guardians gave written informed consent. At the end of the study all participants (including all household members) were offered treatment with ivermectin to eliminate head lice infestation and reduce intestinal helminths.

The study protocol was approved by the Ethical Review Board of the Federal University of Ceará (Fortaleza, CE, Brazil). The trial was registered under number ISRCTN 42288908.

Results

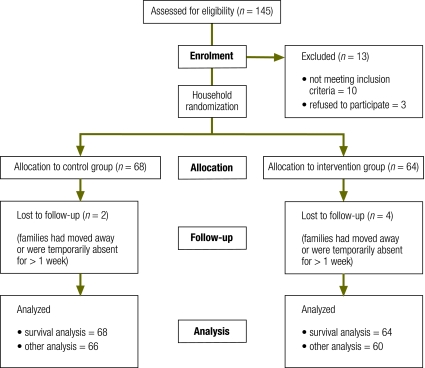

We assessed 145 children for eligibility; 10 children did not meet the inclusion criteria because they had active head lice infestation or intended to move out of the study area during the follow-up period. Three children refused to participate. The resulting 132 participants enrolled into the trial belonged to 78 households (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Flow of participants through stages of a randomized controlled trial of ivermectin treatment for head lice, Fortaleza, CE, Brazil, 2007

Randomization of the households resulted in two groups that were similar in size and in demographic and socioeconomic characteristics (Table 1). In 67% of the cases, two or more sentinel children belonged to the same family. The flow of participants through the trial was similar at all stages; two and four participants were lost during follow-up in the control and intervention groups, respectively (Fig. 1).

Table 1. Demographic and socioeconomic characteristics of the study population and infestation status after 60 days of follow-up, Fortaleza, CE, Brazil, 2007.

| Characteristic | Intervention group | Control group | P-valuea |

|---|---|---|---|

| No. of households/no. of sentinel children | 38/64 | 40/68 | 0.66 |

| Median no. of individuals per household (range) | 6 (3–10) | 5 (2–11) | 0.27 |

| No. of females (%) | 49 (77) | 47 (69) | 0.33 |

| No. of males (%) | 15 (23) | 21 (31) | |

| Median monthly household income in R$b (range) | 350 (60–800) | 350 (60–945) | 0.32 |

| No. of households with ≥ 2 sentinel children (%) | 13 (34) | 19 (46) | 0.2 |

| Mean age in years (SD) | 9.6 (2.5) | 9.5 (2.6) | 0.77 |

| No. free of head lice after 60 days (%) | 10 (16) | 3 (4) | 0.03 |

| No. lost to follow-up (%) | 4 (6) | 2 (3) | 0.44 |

R$, Brazilian real; SD, standard deviation. a Intervention group versus control group. In the intervention group, all family members of sentinel children who lived in the same household as the children were treated with ivermectin; in the control group, no family member was treated. b 1 R$ ≈ 0.50 US$.

The primary analysis by Kaplan–Meier estimates and Cox-regression was based on intention-to-treat. It involved all participants who were randomly assigned. For all other analyses the six participants who had moved out of the study area were treated as lost during follow-up; thus, 126 participants remained for inclusion in the analyses.

Adverse events

No adverse events were reported.

Impact

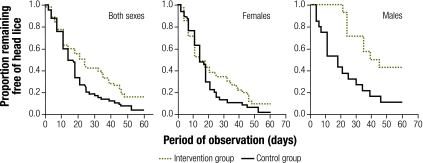

Sentinel children living in families whose members had received ivermectin remained free of head lice significantly longer than children in the control group. The median length of the infestation-free period was 24 days (interquartile range, IQR: 11–45) in the intervention group and 14 days (IQR: 11–25) in the control group (P = 0.01; Fig. 2). At the end point, 10 (16%) sentinel children in the intervention group and 3 (4%) in the control group remained uninfested (P = 0.03).

Fig. 2.

Kaplan–Meier estimates of length of infestation-free periods in randomized controlled trial of ivermectin treatment for head lice, Fortaleza, CE, Brazil, 2007a,b

a Intervention versus control group.

b Females and males combined and stratified by gender.

According to the extrapolation of the gender–stratified Kaplan–Meier curve, all girls would have become infested by day 73 and all boys by day 85. This was equivalent to 19 head lice infestation episodes per year in girls and 15 in boys. In the intervention group, the number of annual episodes was reduced to 14 for girls and 5 for boys.

Boys remained uninfested for a longer period of time than girls, irrespective of household allocation. The median infestation-free periods were 25 days (IQR: 11–46) for boys and 14 days (IQR: 7–27) for girls (P = 0.007; Fig. 2). Among girls, the median infestation-free period was 14 days in both the intervention group (IQR: 7–38 days) and the control group (IQR: 11–21 days; P = 0.18). In boys, the infestation-free period was significantly longer: 39 days (IQR: 24–47 days) in the intervention group and 18 days (IQR: 7–34 days) in the control group (P = 0.005 Fig. 2).

The Cox regression yielded female sex and extreme poverty as the most important independent risk factors for rapid infestation (Table 2). As indicated by a hazard ratio of 1.41, an increase of one score in the poverty index was accompanied by a 41% increase in the risk of head lice infestation. Crowding per se did not contribute to increased transmission of head lice (Table 2). Length and type of hair, as well as age, showed no association with the length of the infestation-free period (all P > 0.10).

Table 2. Factors associated with the length of the infestation-free period in randomized controlled trial of ivermectin treatment for head lice, Fortaleza, CE, Brazil, 2007.

| Factor | Hazard ratioa | 95% CI | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Groupb | 1.47 | 1.01–2.17 | 0.048 |

| Sexc | 1.95 | 1.21–3.11 | 0.005 |

| Poverty index | 1.41d | 1.03–1.93 | 0.031 |

| Crowding | 1.06d | 0.90–1.24 | 0.477 |

| No. of sentinel children per household | 1.11d | 0.90–1.37 | 0.311 |

CI, confidence interval. a Result of Cox regression. b Control group versus intervention group. In the intervention group, all family members of sentinel children who lived in the same household as the children were treated with ivermectin; in the control group, no family member was treated. c Females versus males. d The hazard ratio indicates the effect of a whole unit increase in the unit of measurement.

Discussion

Finding effective ways to reduce head lice transmission is crucial for the control of head lice infestation in impoverished communities. The results of this trial suggest that household-wide treatment with ivermectin is effective in delaying the infestation of household members who are free of head lice. Therefore, treatment for head lice should be administered to the entire household rather than to a single patient.

When considering household-wide treatment, gender-related differences have to be taken into account. Across countries and cultures, girls are more susceptible to head lice infestation,2,3,13,14 primarily due to gender-related differences in social behaviour.8 In this study girls benefited less than boys from household-wide treatment. This highlights the importance of community transmission and of gender-related differences in head lice transmission. Although we cannot know for certain whether the sentinel children became infested within the community or in the household, the fact that household-wide treatment had a lesser effect on the infestation-free period in girls suggests that community transmission is particularly important among females. Boys, on the other hand, became infested in the household once the protective effect of ivermectin treatment had disappeared and in parallel with an increase in the number of infested household members. Nevertheless, household-wide treatment benefited both boys and girls by reducing the number of yearly episodes of head lice infestation.

In addition to female gender, poverty appears to play an important role in head lice transmission. In fact, in children from extremely poor households, the risk of early re-infestation with head lice was twice as high as in other children. This confirms the results of previous studies to the effect that the poorer the household, the greater the odds of frequent head lice infestation among household members, and that the poorest of the poor are the most vulnerable population group.3,15,16 Therefore, a targeted intervention focusing on extremely poor households or impoverished communities is recommended.

Interventions for the control of head lice infestation could be based on ivermectin treatment. Ivermectin is effective against various parasitic skin diseases, including scabies and hookworm-related cutaneous larva migrans.17 Its effectiveness against head lice has been documented repeatedly.17,18 Mass treatment with ivermectin in resource-poor communities has already been shown to significantly reduce the prevalence of intestinal helminths and of cutaneous infestation19 For soil-transmitted helminths, repeated ivermectin mass treatments have been shown to reduce transmission as well.20 With this study we have demonstrated that an intervention consisting of household-wide treatment with ivermectin effectively reduces within-household transmission of head lice. These findings suggest that mass treatment with ivermectin not only reduces the prevalence of head lice infestation in treated individuals, but also benefits untreated members of the community by reducing transmission.

Transmission could be further reduced by repeated mass administration of ivermectin. Repeated mass treatments can potentially halt the transmission of onchocerciasis,21 and the same may be true for head lice transmission. In this study, a one-time, household-wide administration of ivermectin considerably reduced the estimated annual number of head lice episodes in children. Repeated administration could reduce the number of head lice episodes even further, to the extent that children could eventually be rid of head lice, at least for prolonged periods during the year. This would in turn reduce morbidity associated with head lice infestation. In Brazil mass treatments with ivermectin could be implemented through the Brazilian Unified Health System (Sistema Único de Saúde) with its network of primary health care centres.

The study design used has two major drawbacks. The sample size was limited to the number of children who had participated in the previous randomized clinical trial – i.e. children with an active head lice infestation. Although the households included are felt to represent the social and economic diversity within a shanty town, they were not randomly selected. The incidence of head lice infestation is therefore likely to be overestimated, as our sample included mainly children at high risk of acquiring head lice. One cannot conclude that the difference in the outcome measure between the intervention and control group would be identical in a future study based on randomly-selected households.

In this study, 67% of sentinel children lived in a family with other sentinel children. Even though this was considered in the multivariate analysis, potential bias cannot be ruled out. A split-within-household randomization strategy, whereby two participants in the same household are randomly split into the intervention and the control group, can improve the sensitivity of the study design.22 Obviously, this approach is not feasible for interventions that must be performed at the household level. Studies with only one sentinel child per household should be conducted to further investigate the effect of household-wide treatment on the transmission of head lice. ■

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Antonia Valéria Assunção Santos, Marilene da Silva Paulo and Maria de Fátima Cavalcante for their skillful guidance, and Michi Feldmeier for his secretarial assistance. J. Heukelbach is a research fellow from the Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq/Brazil). The data are part of DP’s doctoral thesis.

Footnotes

Funding: The study was partially supported by Komitee Ärzte für die Dritte Welt, Frankfurt, Germany.

Competing interests: None declared.

References

- 1.Heukelbach J, Wilcke T, Winter B, Feldmeier H. Epidemiology and morbidity of scabies and pediculosis capitis in resource-poor communities in Brazil. Br J Dermatol. 2005;153:150–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2005.06591.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abdel-Hafez K, Abdel-Aty MA, Hofny ER. Prevalence of skin diseases in rural areas of Assiut Governorate, Upper Egypt. Int J Dermatol. 2003;42:887–92. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-4362.2003.01936.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Amr ZS, Nusier MN. Pediculosis capitis in northern Jordan. Int J Dermatol. 2000;39:919–21. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-4362.2000.00088.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Heukelbach J, van Haeff E, Rump B, Wilcke T, Moura RC, Feldmeier H. Parasitic skin diseases: health care-seeking in a slum in north-east Brazil. Trop Med Int Health. 2003;8:368–73. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3156.2003.01038.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wegner Z, Racewicz M, Stanczak J. Occurrence of pediculosis capitis in a population of children from Gdansk, Sopot, Gdynia and the vicinities. Appl Parasitol. 1994;35:219–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Burgess IF, Lee PN, Matlock G. Randomised, controlled, assessor blind trial comparing 4% dimeticone lotion with 0.5% malathion liquid for head louse infestation. PLoS One. 2007;2:e1127. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Feldmeier H, Singh Chhatwal G, Guerra H. Pyoderma, group A streptococci and parasitic skin diseases – a dangerous relationship. Trop Med Int Health. 2005;10:713–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2005.01457.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Downs AM, Stafford KA, Stewart GH, Coles GC. Factors that may be influencing the prevalence of head lice in British school children. Pediatr Dermatol. 2000;17:72–4. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1470.2000.00011-3.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Heukelbach J, Pilger D, Oliveira FA, Khakban A, Ariza L, Feldmeier H. A highly efficacious pediculicide based on dimeticone: randomized observer blinded comparative trial. BMC Infect Dis. 2008;8:115. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-8-115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.De Maeseneer J, Blokland I, Willems S, Vander Stichele R, Meersschaut F. Wet combing versus traditional scalp inspection to detect head lice in schoolchildren: observational study. BMJ. 2000;321:1187–8. doi: 10.1136/bmj.321.7270.1187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Burgess IF. Human lice and their control. Annu Rev Entomol. 2004;49:457–81. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ento.49.061802.123253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pilger D, Khakban A, Heukelbach J, Feldmeier H. Self-diagnosis of active head lice infestation by individuals from an impoverished community: high sensitivity and specificity. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo. 2008;50:121–2. doi: 10.1590/s0036-46652008000200011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Buczek A, Markowska-Gosik D, Widomska D, Kawa IM. Pediculosis capitis among schoolchildren in urban and rural areas of eastern Poland. Eur J Epidemiol. 2003;19:491–5. doi: 10.1023/B:EJEP.0000027347.76908.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Catalá S, Junco L, Vaporaky R. Pediculus capitis infestation according to sex and social factors in Argentina. Rev Saude Publica. 2005;39:438–43. doi: 10.1590/S0034-89102005000300015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Abdel-Hafez K, Abdel-Aty MA, Hofny ER. Prevalence of skin diseases in rural areas of Assiut Governorate, Upper Egypt. Int J Dermatol. 2003;42:887–92. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-4362.2003.01936.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Catalá S, Junco L, Vaporaky R. Pediculus capitis infestation according to sex and social factors in Argentina. Rev Saude Publica. 2005;39:438–43. doi: 10.1590/S0034-89102005000300015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dourmishev AL, Dourmishev LA, Schwartz RA. Ivermectin: pharmacology and application in dermatology. Int J Dermatol. 2005;44:981–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2004.02253.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Glaziou P, Nyguyen LN, Moulia-Pelat JP, Cartel JL, Martin PM. Efficacy of ivermectin for the treatment of head lice (Pediculosis capitis). Trop Med Parasitol. 1994;45:253–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Heukelbach J, Winter B, Wilcke T, Muehlen M, Albrecht S, de Oliveira FA, et al. Selective mass treatment with ivermectin to control intestinal helminthiases and parasitic skin diseases in a severely affected population. Bull World Health Organ. 2004;82:563–71. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moncayo AL, Vaca M, Amorim L, Rodriguez A, Erazo S, Oviedo G, et al. Impact of long-term treatment with ivermectin on the prevalence and intensity of soil-transmitted helminth infections. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2008;2:e293. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Winnen M, Plaisier AP, Alley ES, Nagelkerke NJ, van Oortmarssen G, Boatin BA, et al. Can ivermectin mass treatments eliminate onchocerciasis in Africa? Bull World Health Organ. 2002;80:384–91. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chen C, Gould AL, Tipping RW, Guzzo C, Furtek C. Effect of within-household reinfestation on design sensitivity. J Biopharm Stat. 2003;13:327–36. doi: 10.1081/BIP-120019368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]