Abstract

Membrane-bound and membrane-associated proteins are difficult to analyze by mass spectrometry, since the association with lipids impedes the isolation and solubilization of the proteins in buffers suitable for mass spectrometry and the efficient generation of positively charged peptide ions by electrospray ionization. Current methods mostly utilize detergents for the isolation of proteins from membranes. In this study, we present an improved detergent-free method for the isolation and mass spectrometric identification of membrane-bound and membrane-associated proteins. We delipidate proteins from the membrane bilayer by chloroform extraction to overcome dissolution and ionization problems during analysis. Comparison of our results to results obtained by direct tryptic digestion of insoluble membrane pellets identifies an increased number of membrane proteins, and a higher quality of the resulting mass spectral data.

Keywords: membrane proteomics, chloroform extraction, liquid chromatography/tandem mass spectrometry

Membrane proteins play a vital role in numerous cellular functions. The integral membrane proteins act as receptors, channels, and are involved in cell adhesion and signaling, whereas peripheral membrane proteins are primarily involved in cell signaling. About 30% of the mammalian genome encodes integral membrane proteins (14). However, the comprehensive proteomic analysis of these proteins by mass spectrometry is difficult due to their amphipathic nature (11). Membrane proteins are composed of both hydrophilic and hydrophobic regions, and they behave more like lipids than proteins due to their association with lipid bilayer in the membrane. Hence extraction, solubilization, and characterization by mass spectral analysis have been a major challenge (11).

Numerous studies have attempted to improve the efficiency of membrane proteomics (2, 3, 6, 8, 10, 16, 18, 19). Traditionally, gel-based methods have been used for analysis of complex protein samples (10, 11). Unfortunately, most of the membrane proteins are not solubilized in nondetergent isoelectric focusing sample buffers, and those solubilized tend to precipitate at their isoelectric point (11, 18). The problem of insolubility remains the same in methods using liquid chromatography coupled to mass spectrometry. Several approaches have attempted to overcome this problem by using either strong organic acid-cyanogen bromide (16), detergents (8), acid labile surfactants (19), organic solvents (2, 3, 6), salts, or high pH conditions (17) to solubilize membrane proteins. Though these methods proved to be efficient, they have other disadvantages. The presence of detergents affects the performance of chromatographic separation and also leads to mass spectral signal suppression. Most common proteases like trypsin cannot be used for digestion of proteins when organic acids are used due to low pH conditions, or the enzyme activity is reduced in presence of high percentage of organic solvents. High pH-based methods use proteinase K, which cleaves proteins nonspecifically at random amino acid sequences. In addition, all methods described above require extensive sample handling to make the sample compatible for mass spectral analysis. No optimal approach has been developed, and there remains a need for simpler and more efficient methods of extraction of membrane proteins. The major obstacle is the lipid bilayer in which proteins are embedded, and in most of the studies reported, lipids are also extracted in the membrane protein fraction. As a consequence of these difficulties, proteomic analyses of membrane protein fractions have relied on gel-based methods. These efforts have demonstrated that delipidation of membrane proteins by organic solvents improves the performance of two-dimensional electrophoresis (2 DE) of the proteins(12, 13, 20).

In this study, we developed a novel approach to delipidate membrane proteins by a simple and efficient chloroform extraction. The proteins devoid of lipids are efficiently solubilized in urea-ammonium bicarbonate buffer suitable for subsequent tryptic digestion and mass spectral analysis. We report in this study that, following our method of extraction, there is a significant improvement in the number of membrane proteins identified, and the proteins are identified with high accuracy and confidence. Based on these results, the new method, for the first time, provides the necessary experimental tools for a comprehensive mass spectrometric analysis of membrane-bound and membrane-associated proteins in cells and tissues.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

All chemicals were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO) unless specified. EDTA (0.5 M) was from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA). Dithiothreitol (DTT) and micro-BCA assay kits were from Pierce (Rockford, IL). Trypsin used was mass spectrometry-grade Trypsin Gold from Promega (Madison, WI). Protease inhibitor cocktail tablets were procured from Roche Diagnostics (Mannheim, Germany). Methanol, acetonitrile, and water were HPLC-grade solvents from Burdick & Jackson (Muskegon, MI).

Instrumentation

Nano-HPLC-mass spectrometry experiments were performed on an LTQ mass spectrometer (Thermo Electron) coupled with a Surveyor HPLC system (Thermo Electron) equipped with an autosampler. The instruments were interfaced with a capillary column (100 × 0.1 mm), in-house packed with 5 μm of C18 RP particles (Luna C18, Phenomenex). The fused silica capillaries (Polymicro Technologies) for the columns were pulled by a micropipette puller P-2000 (Sutter Instrument) and were then packed with C18 resin using a bomb-loader. The vortex mixer was purchased from VWR International (West Chester, PA). The FS30 bath sonicator was purchased from Fischer Scientific (Pittsburgh, PA).

Enrichment of membrane-associated proteins from endothelial cell lysate

Vascular endothelial cells from rats were cultured, and the cellular proteome was subfractionated into soluble and insoluble fractions. Briefly, the endothelial cell pellet obtained from 2 × 107 cells was suspended in 0.5 ml of isolation buffer (mixture of 200 mM mannitol, 70 mM sucrose, 10 mM HEPES, and 1 mM EDTA of pH 7.4 supplemented with protease inhibitor cocktail) and homogenized with a 23-G needle fixed to a 1-ml syringe. The cell lysate obtained was made up to 15 ml in a centrifuge tube with isolation buffer. First, soluble proteins were separated out into the supernatant by centrifuging at 7,000 g for 10 min. The remaining cell pellet was resuspended in 15 ml of isolation buffer containing 0.1% bovine serum albumin and spun at low speed (800 g) for 10 min. The resulting pellet contained the insoluble protein fraction, leaving smaller cellular organelles in the supernatant.

Delipidation of membrane proteins and sample preparation for mass spectrometry

The insoluble protein fraction (~100 μg, as measured by micro-BCA assay) was incubated in 1 ml of chloroform on a shaker at room temperature for 1 h. To this, 1 ml of methanol-water (1:1 vol/vol) was added, and the mixture was vortexed vigorously for 30 min. The mixture was spun at 2,000 g for 1 min, and the chloroform layer was discarded. Another 1 ml of chloroform was added to further extract lipids. The mixture was sonicated in a bath sonicator for 30 min without heating. Ice-cold water was added at regular intervals to prevent heating due to continuous sonication. The mixture was then spun at 10,000 g for 5 min. The chloroform layer was discarded since direct mass spectral analysis of proteins extracted in this layer is poor due to enrichment of lipids (1). Hence, we have not attempted to identify proteins that remain in the chloroform phase. However, previous studies have shown that only very few proteins are extracted into the organic phase during the delipidation of membrane proteins (12, 13).

To the aqueous layer and the insoluble interface, four times the volume of acetone was added and incubated at 4°C for 1 h. The protein was collected by pelleting at 10,000 g for 5 min. The protein pellet was washed twice with acetone, dried on ice, and dissolved in 2 M urea and 250 mM ammonium bicarbonate to complete dissolution. Protein denaturation and reduction were carried out by adding DTT to 10 mM and incubated for 30 min at 50°C, and alkylation was carried out by the addition of iodoacetamide at 30 mM final concentration and incubated at 37°C for 1 h in the dark. Protein was then trypsin digested in 30% methanol at 20:1 (wt/wt) protein to protease ratio and incubated overnight at 37°C (9). The protein digestion was stopped by the addition of 1% formic acid. The sample was dried under vacuum in a speed vac concentrator and resuspended in 0.1% formic acid for desalting using C18 Zip-tips. The desalted peptide sample was further analyzed by nano-HPLC mass spectrometry. To compare the results, an equal aliquot of the sample was prepared the same way but without the initial chloroform extraction.

Nano-liquid chromatography-electrospray ionization mass spectrometry

The membrane protein digest was analyzed using an ion trap LTQ mass spectrometer interfaced with a nano-liquid chromatography (LC) system. This sample was loaded through an autosampler onto a C18 capillary column. The solvents A and B used for chromatographic separation of peptides were 5% acetonitrile in 0.1% formic acid and 95% acetonitrile in 0.1% formic acid, respectively. The peptides injected onto the microcapillary column were resolved at the rate of 200 nl/min, by the following gradient conditions: 0–30 min 0–5% B, 30–180 min 5–35% B, 180–240 min 35–65% B, 240–250 min 65–100% B; 100% B was held for 10 min, then switched to 100% A and held for another 40 min.

The ions eluted from the column were electrosprayed at a voltage of 1.8 kV. The capillary voltage was 45 V, and the temperature was kept at 200°C. No auxillary or sheath gas was used. Helium was used in the trap, which was also used as a collision gas for fragmentation of ions. The target value for the ion trap was 3 × 104 ions in full scan mode and 1 × 104 in mass spectrometry/mass spectrometry (MS/MS) mode. A full scan mass spectrum (400 –2,000 m/z) was followed by fragmentation of the six most abundant peaks from the full scan mass spectrum, using 35% of the normalized collision energy for obtaining MS/MS spectra. Dynamic exclusion was enabled for 30 sec. The chromatographic and mass spectral functions were controlled by the Xcalibur data system (ThermoFinnigan, Palo Alto, CA).

The mass spectrometry data obtained were searched using the SEQUEST algorithm against Uniprot Rodent database v49.1. The search was limited to only tryptic peptides, and identifications were filtered from the search results using the Epitomize program (7). Epitomize reads all the SEQUEST. out files in a directory, filters the files based on user-defined levels of Xcorr, and outputs the proteins identified. The Xcorr vs. charge state filter used was set to Xcorr values of 1.8, 2.3, and 3.0 for charge states +1, +2, and +3, respectively. These filter values are similar to others previously reported for SEQUEST analyses (15). Protein hits that passed the filter were annotated using the generic GO slim. The dynamic visualization of the protein hits was carried out using Treemap (University of Maryland) to determine the cellular localization of the proteins identified. All proteins were identified by two or more peptides, and those identified with single peptide were included in the analysis if identified in two or more scans. Finally, the peptides listed were manually verified for correct identification by comparing the experimental spectra with the theoretical b and y ion spectra.

To estimate the false discovery rate (FDR) for protein identification, we applied the method outlined by Elias et al. (5). The analysis utilized a customized version of the rodent subset of the UniProt 49.1 protein sequence database containing both randomized and unrandomized versions of each sequence using the decoy.pl script made available by Matrix Science. Data from a representative LC-MS/MS run were searched against this database using SEQUEST, and the search results were filtered and scored using the Epitomize program. Protein hits were ranked by score and the cumulative frequency of hits to randomized sequences was determined for each score value. Since it is expected that the frequency of false hits to randomized sequences will be equal to the frequency of false hits to unrandomized sequences, we calculated the FDR as twice the frequency of false hits to randomized sequences. The same approach was applied to all other samples since the other LC-MS/MS runs were very similar and searched against the same parent database.

RESULTS

Protein identification

Membrane proteins are extremely difficult to analyze by mass spectrometry due to their hydrophobic nature. The major challenge is their low solubility in aqueous media that are typically used for tryptic digestion before mass spectral analysis. Hence we developed a method of lipid extraction to improve solubilization and tryptic digestion of membrane proteins compatible with mass spectral analysis. In this study, we carried out experiments using the insoluble protein fraction obtained by differential centrifugation from rat vascular endothelial cell lysate separating the soluble proteins and smaller organelles. The insoluble protein pellet contains most of the cell membrane, the nucleus, and larger organelles. In our approach, the protein pellet was chloroform extracted for delipidation of proteins before tryptic digestion. The tryptic peptides were analyzed by nano-LC-tandem mass spectrometry.

Our method of analysis unambiguously identified 936 proteins when searched against the Uniprot Rodent database v49.1 using the SEQUEST algorithm. Of these, 401 (43%) proteins were found to be membrane-associated (integral to membrane and membrane) as annotated by the generic GO slim. The list of membrane-associated proteins identified by our analysis is provided in the supplementary material (Supplementary Table S1; the online version of this article contains supplementary material).

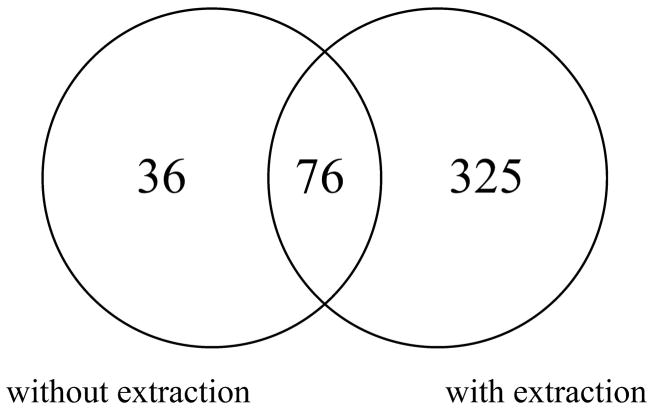

When an equal aliquot of the insoluble protein fraction was analyzed under similar experimental conditions but without chloroform extraction, only 745 proteins were identified, of which only 112 (15%) were found to be membrane associated. Of the 112 proteins identified without delipidation, 76 were also identified by our new method (Fig. 1). However, an additional 325 membrane-associated proteins were identified by performing our method of delipidation by chloroform extraction, thereby increasing the fraction of membrane-associated proteins from 15% to 43% of the total proteins identified. Also, the total proteins identified was improved by 26% (745 to 936 proteins) upon chloroform extraction of protein before tryptic digestion and mass spectral analysis, and 432 (58%) proteins overlap between the two experiments.

Fig. 1.

Comparison of membrane proteins identified by nano-liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry/mass spectrometry experiments with and without chloroform extraction of insoluble protein fraction of vascular endothelial cells.

Cytoskeletal proteins were not included in the membrane-associated proteins listed, as most of them are easily identified even without any special treatments. Cytoskeletal proteins like actins or tropomyosin are commonly identified in every sub-cellular fraction analyzed by mass spectrometry, as observed in our experiments. A total of 63 cytoskeletal proteins were identified in our membrane protein fraction extracted with chloroform before trypsin digestion and mass spectral analysis that were also identified in the soluble protein fraction (data not shown). In total, 510 proteins were uniquely identified only in the insoluble fraction of the cell lysate and were not identified by the mass spectral analysis of the soluble proteome.

Data accuracy

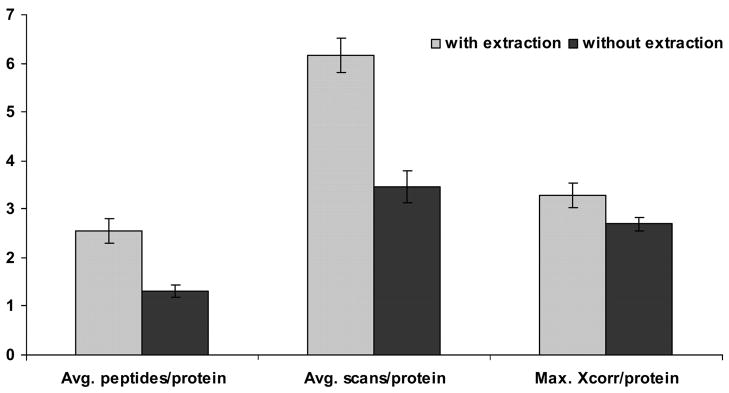

All proteins listed were identified by multiple peptides or multiple scans as discussed in the experimental section. After chloroform extraction, proteins were identified with higher confidence compared with those without extraction. This is illustrated by the Xcorr value obtained, and the number of scans and peptides identified per protein (Fig. 2). Table 1 lists membrane-associated proteins that were identified in both the experiments with and without chloroform extraction. The table illustrates that the number of scans and peptides from which each protein is identified is higher in the experiment that followed our method of extraction. An average of six scans and three peptides were identified per protein after extraction, compared with three scans and one peptide identified without extraction (Fig. 2). Furthermore, the Xcorr values obtained in the experiment with chloroform extraction were significantly higher than those without extraction. The average of maximum Xcorr values obtained is 3.29 and 2.69, respectively for proteins identified with and without extraction of proteins for delipidation (Fig. 2). For better evaluation of the results obtained, a paired t-test was performed to verify the statistical significance of the difference in the number of scans, peptides identified and Xcorr values obtained per protein in experiments with and without chloroform extraction. The P values for the two-tailed distribution were calculated and found to be highly significant at P < 10−6 for all three parameters (Table 1).

Fig. 2.

Plot representing the average number of peptides, scans, and Xcorr values obtained per protein identification from experiments carried out with and without chloroform extraction of proteins from insoluble protein fraction of rat vascular endothelial cells.

Table 1.

Proteins obtained from experiments with and without extraction from the insoluble protein fraction of rat vascular endothelial cells

| Peptides |

Scans |

Max. Xcorr |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Protein Name | WE | WOE | WE | WOE | WE | WOE |

| ADAM 9 precursor | 2 | 1 | 4 | 2 | 3.8318 | 2.2403 |

| ADP/ATP translocase 1 | 4 | 2 | 15 | 5 | 3.6204 | 2.6370 |

| Annexin A2 | 9 | 1 | 26 | 3 | 5.2252 | 2.4288 |

| AP-2 complex subunit beta-1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 2.3246 | 2.2968 |

| Plasma membrane calcium-transporting ATPase 4 | 2 | 1 | 4 | 3 | 2.8878 | 2.7181 |

| ATP synthase alpha chain, mitochondrial precursor | 5 | 3 | 14 | 8 | 4.5604 | 3.5620 |

| ATP synthase beta chain, mitochondrial precursor | 11 | 4 | 31 | 30 | 5.5300 | 4.8709 |

| Voltage-dependent L-type calcium channel alpha-1F subunit | 1 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 2.8769 | 2.6353 |

| Calnexin precursor | 3 | 1 | 9 | 6 | 4.6579 | 4.5308 |

| Cadherin EGF LAG seven-pass G-type receptor 1 precursor | 2 | 1 | 4 | 2 | 2.3972 | 2.0403 |

| Filamin-C | 3 | 1 | 5 | 2 | 2.5230 | 2.2974 |

| Extracellular matrix protein FRASI precursor | 1 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 2.5211 | 2.2562 |

| Interferon-induced guanylate-binding protein 2 | 3 | 1 | 5 | 2 | 2.2896 | 2.2404 |

| Interferon-inducible protein | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 5.6206 | 5.3261 |

| Integrin beta-1 precursor | 3 | 1 | 6 | 3 | 4.3674 | 2.2856 |

| Protein KIAA0152 precursor | 2 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 4.1188 | 2.3626 |

| Lamina-associated polypeptide 2 isoform beta | 1 | 1 | 4 | 2 | 3.3331 | 2.2512 |

| Lamina-associated polypeptide 2 isoforms alpha/zeta | 2 | 1 | 10 | 2 | 4.0607 | 2.2471 |

| Alpha-mannosidase II | 4 | 1 | 6 | 3 | 2.2522 | 2.3168 |

| Macoilin (Transmembrane protein 57) | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2.5098 | 2.4038 |

| Ubiquitin ligase protein MIBI | 1 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 2.3710 | 2.2760 |

| Protein disulfide-isomerase precursor | 13 | 2 | 36 | 4 | 5.2465 | 4.2730 |

| Membrane associated progesterone receptor component 1 | 2 | 1 | 9 | 7 | 3.7158 | 3.6931 |

| Membrane associated progesterone receptor component 2 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 3.6945 | 3.7157 |

| Prohibitin-2 | 4 | 4 | 13 | 11 | 2.8761 | 2.8919 |

| Procollagen-lysine,2-oxoglutarate 5-dioxygenase 1 precursor | 2 | 1 | 5 | 2 | 4.6284 | 3.2978 |

| Procollagen-lysine,2-oxoglutarate 5-dioxygenase 2 precursor | 5 | 2 | 10 | 3 | 4.0967 | 3.3485 |

| Prominin-1 precursor | 1 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 2.5112 | 2.2519 |

| PX domain-containing protein kinase-like protein | 3 | 1 | 6 | 2 | 2.5235 | 2.2813 |

| Dolichyl-diphosphooligosaccharide-protein glycosyltrans 1 | 2 | 2 | 12 | 9 | 3.2368 | 2.8323 |

| Dolichyl-diphosphooligosaccharide-protein glycosyltrans 2 | 2 | 2 | 6 | 4 | 3.5918 | 2.8166 |

| Ribosome-binding protein 1 | 3 | 1 | 8 | 5 | 3.7166 | 2.3917 |

| Reticulon-4 | 1 | 1 | 5 | 2 | 3.3335 | 3.2499 |

| SAM domain and HD domain-containing protein 1 | 2 | 1 | 4 | 3 | 2.6270 | 2.3851 |

| Sciellin | 3 | 1 | 4 | 2 | 2.5140 | 2.4244 |

| SH2 domain protein 1B | 1 | 1 | 5 | 3 | 2.4266 | 2.3176 |

| Solute carrier organic anion transporter family member | 2 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 2.8095 | 2.5624 |

| SPARC precursor | 4 | 4 | 12 | 10 | 5.4934 | 5.2205 |

| Spectrin alpha chain, brain | 7 | 2 | 7 | 2 | 3.5846 | 3.2807 |

| Spectrin beta chain, erythrocyte | 1 | 1 | 4 | 2 | 2.3841 | 2.2452 |

| Translocon-associated protein delta subunit precursor | 2 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 3.6205 | 3.3212 |

| Thrombospondin-1 precursor | 4 | 2 | 7 | 5 | 3.4755 | 3.3465 |

| Ubiquinol-cytochrome c reductase iron-sulfur subunit | 2 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 2.5723 | 2.5139 |

| Vesicle-associated membrane protein-associated protein A | 4 | 1 | 9 | 3 | 4.3002 | 2.4936 |

| Voltage-dependent anion-selective channel protein 1 | 3 | 2 | 15 | 9 | 3.2074 | 2.8631 |

| Tight junction protein ZO-1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2.3271 | 2.2736 |

| Calpactin 1 light chain | 2 | 1 | 10 | 4 | 6.3909 | 2.2381 |

| Adenylate cyclase type VIII | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2.8650 | 2.2361 |

| Tyrosine-protein kinase JAKI | 2 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 2.3067 | 2.2794 |

| Cytochrome P450 11B1, mitochondrial precursor | 3 | 1 | 5 | 3 | 2.4020 | 2.3217 |

| Calmodulin (CaM) | 2 | 1 | 4 | 3 | 4.3858 | 3.7629 |

| Coatomer subunit beta | 2 | 1 | 5 | 2 | 2.3388 | 2.3104 |

| Dystrophin | 3 | 1 | 4 | 2 | 2.5167 | 2.2374 |

| Retrovirus-related Env polyprotein from Fv-4 locus | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2.3174 | 2.2289 |

| Hermansky-Pudlak syndrome 4 protein homolog | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2.3484 | 2.2318 |

| Protein KIAA0323 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2.3207 | 2.2319 |

| Basement membrane-specific heparan sulfate proteoglycan | 3 | 1 | 7 | 4 | 4.8670 | 2.2467 |

| Metalloproteinase inhibitor 1 precursor | 1 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 2.6102 | 2.6454 |

| Thioredoxin domain-containing protein 4 precursor | 3 | 1 | 4 | 2 | 3.9759 | 3.0143 |

| Huntingtin | 1 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 2.9997 | 2.2342 |

| Calreticulin precursor | 4 | 1 | 7 | 2 | 3.5318 | 2.7784 |

| Clathrin light chain B | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 3.4612 | 2.4258 |

| Guanine nucleotide-binding protein G(i), alpha-2 subunit | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2.4811 | 2.3745 |

| Ras-related protein Rab-1B | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2.7378 | 2.3631 |

| Calpactin 1 light chain (S100 calcium-binding protein) | 2 | 1 | 10 | 4 | 6.3909 | 2.2381 |

| Laminin alpha-5 chain precursor | 1 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 2.3111 | 2.4067 |

| ERGIC-53 protein precursor | 2 | 1 | 5 | 2 | 3.2224 | 2.2034 |

| Glypican-1 precursor | 1 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 2.7332 | 2.4261 |

| Solute carrier family 12 member 1 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 2.2549 | 2.2577 |

| Solute carrier organic anion transporter family member | 1 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 2.9167 | 2.1779 |

| Transient receptor potential cation channel subfamily | 2 | 1 | 4 | 4 | 2.5963 | 2.4881 |

| NAD-dependent deacetylase sirtuin-7 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 2.2907 | 2.1129 |

| Sad1/unc-84 protein-like 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 2.7009 | 2.4179 |

| Toll-like receptor 13 precursor | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 2.6326 | 2.5744 |

| Interleukin-11 receptor alpha-1 chain precursor | 2 | 1 | 4 | 2 | 2.4513 | 2.2420 |

| Acyl-CoA dehydrogenase | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2.5472 | 2.6906 |

| *P-value | 1.38E-07 | 3.43E-06 | 4.85E-08 | |||

This list of proteins shows peptides, scans, and Xcorr values obtained for each protein identified. WE, with extraction; WOE, without extraction.

The FDR was calculated by searching the data against a custom decoy database (5). Here, 738 out of 936 proteins identified after delipidation have an FDR of 0.5 or less. Proteins that have FDR >0.5 were manually verified for correct identification by comparing experimental spectra with the theoretical b and y ion spectra.

DISCUSSION

Most of the methods for sample preparation of membrane proteins that have been developed over the past several years are not compatible with mass spectral analysis. This is due to the use of high concentrations of organic acids (16), detergents (8), which affect the enzymatic digestion or chromatographic processes, or the use of high amounts of salts causing ion suppression effects in mass spectral analysis (18).

In the method using high concentrations of organic acids, membrane proteins are solubilized in 90% formic acid and cleaved in presence of cyanogens bromide (16). The larger fragments are further digested using endoproteinase LysC and trypsin, followed by mass spectral analysis. In this method, cyanogen bromide is used for the initial cleavage of proteins as trypsin cannot be used under highly acidic conditions. Also, care is required to handle cyanogen bromide, which is highly toxic. In another study, the membrane-enriched microsomal fraction was solubilized by boiling in 0.5% SDS (8). The sample then needed to be diluted further to reduce the SDS concentration to make it compatible to tryptic digestion, and additional chromatographic steps were required for sample clean up before mass spectral analysis. Blonder et al. (2) reported a detergent- and cyanogen bromide-free method for integral membrane proteomics, using 60% methanol to solubilize the protein before tryptic digestion. Although the method is efficient in solubilizing the protein, trypsin activity is reduced under these conditions. Alternatively, Wu et al. (17) developed a method for comprehensive proteomic analysis of membrane proteins using high pH conditions to produce membrane sheets and proteinase K, resulting in sequence-independent cleavage of proteins. In another study, acid labile surfactants were added to improve the solubility of membrane proteins (19). Though trypsin activity is not altered in presence of these surfactants, chromatographic performance is affected. Hence, the sample needs to be acid hydrolyzed to remove these surfactants before mass spectral analysis. Recently, Cao et al. (4) published a two-phase partition method for the analysis of membrane proteins. The method utilizes sucrose density centrifugation in conjunction with an aqueous two-phase partition method for plasma membrane isolation. The enriched plasma membrane proteins are then separated by SDS-PAGE followed by mass spectral analysis. They achieved an identification of 204 (48%) membrane-associated proteins (including cytoskeletal proteins) of the 428 proteins identified, but the method involves various enrichment and extraction steps before mass spectral analysis making it very tedious and time consuming.

To overcome the complexity of these methods, we developed an efficient and facile method for membrane proteomics, where we separated the proteins from lipid layers to improve the efficiency of enzymatic digestion. We developed a simplified solvent extraction method to separate proteins from the lipid bilayer in the membrane where the lipids are extracted into chloroform due to their high affinity to nonpolar solvents. By performing only a few simple extraction steps, we achieved an improved identification of 401 membrane-associated proteins out of 936 total proteins identified. Of the 401 membrane-associated proteins identified, 204 (51%) are found to be integral membrane proteins. This signifies that our method of extraction efficiently delipidates proteins, since we identified a large number of integral membrane proteins that are otherwise trapped inside the lipid layer and therefore difficult to analyze. Besides enhancing the membrane protein identification, our method of extraction also identifies proteins with higher accuracy. This is illustrated by the higher number of scans and peptides identified per protein. The Xcorr values generated by SEQUEST reflect the confidence in protein identification. The greater the Xcorr value, higher is the confidence with which the peptide is identified. Our data shows that the Xcorr values of peptides identified are significantly higher in experiments with chloroform extraction (Table 1).

Despite the sonication and vortexing during delipidation, we do not observe an increased fragmentation of proteins. We do not find an increased number of nontryptic peptides identified by mass spectrometry in the chloroform extracted sample.

An added advantage of our method is its applicability to quantitative studies. Of the literature methods mentioned above, detergent- and organic solvent-based methods are compatible with quantitative analysis. However, the use of high concentrations of organic acid or high pH-based methods prohibits quantitative studies, especially those involving enzyme-mediated labeling quantification techniques. Our method of extraction is highly compatible with such quantification techniques as the protein is enriched and extracted followed by trypsin digestion and tandem mass spectrometry, enabling comparison of proteins from different samples using methods such as trypsin-mediated incorporation of 18O (7).

Recently, Bernd Schröder and Andrej Hasilik (12) reported a similar method of extraction of membrane proteins using chloroform-methanol-trifluoroacetic acid-water. They attained clear and sharp bands of proteins by 2 DE. Though the gel-based methods have shown increased applicability of delipidated proteins in 2 DE, the study did not aim to identify the separated proteins and classify them into membrane-bound or membrane-associated proteins by mass spectrometry. Our manuscript, for the first time, provides a detailed protocol for the preparation of membrane-bound proteins for mass spectrometric analysis. The data presented here clearly illustrate the improved identification of membrane proteins, and the increased confidence in the mass spectrometric data compared with standard mass spectrometric techniques commonly used.

As our method involves use of only a few solvent extraction steps, there is no need to perform any additional sample cleaning steps prior to mass spectral analysis. As a result, there is minimal sample loss during the sample preparation. In addition to being a simple, fast, and inexpensive method of extraction, the approach improves the protein identification with higher confidence in the characterization of proteins identified.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Molly Pellitteri-Hahn, Regina Cole, Maria Warren, Erika Keyes, and Dr. Bassam Wakim for technical assistance. We also thank Jeff Eckert for helpful advice during the preparation of this manuscript.

GRANTS

This work was funded by National Institutes of Health Grant N01-HV-28182.

Footnotes

A complete list of all the membrane-associated proteins identified from the delipidated insoluble protein fraction of vascular endothelial cells of rat is provided in Supplementary Table S1.

References

- 1.Bligh EG, Dyer WJ. A rapid method of total lipid extraction and purification. Can J Biochem Physiol. 1959;37:911–917. doi: 10.1139/o59-099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blonder J, Conrads TP, Yu LR, Terunuma A, Janini GM, Isaaq HW, Vogel JC, Veenstra TD. A detergent-and cyanogen bromide-free method for integral membrane proteomics: application to Halobacterium purple membranes and the human epidermal membrane proteome. Proteomics. 2004;4:31–45. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200300543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blonder J, Goshe MB, Moore RJ, Pasa-Tolic L, Masselon CD, Lipton MS, Smith RD. Enrichment of integral membrane proteins for proteomic analysis using liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. J Prot Res. 2002;1:351–360. doi: 10.1021/pr0255248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cao R, Li X, Liu Z, Peng X, Hu W, Wang X, Chen P, Xie J, Liang S. Integration a two-phase partition method into proteomics research on rat liver plasma membrane proteins. J Prot Res. 2006;5:634–642. doi: 10.1021/pr050387a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Elias JE, Haas W, Faherty BK, Gygi SP. Comparative evaluation of mass spectrometry platforms used in large-scale proteomics investigations. Nat Methods. 2005;2:667–675. doi: 10.1038/nmeth785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goshe MB, Blonder J, Smith RD. Affinity labeling of highly hydrophobic integral membrane proteins for proteome-wide analysis. J Prot Res. 2003;2:153–161. doi: 10.1021/pr0255607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Halligan BD, Slyper RY, Twigger SN, Hicks W, Olivier M, Greene AS. ZoomQuant: an application for the quantification of stable isotope labeled peptides. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 2005;16:302–306. doi: 10.1016/j.jasms.2004.11.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Han DK, Eng J, Zhou H, Aebersold R. Quantitative profiling of differentiation-induced microsomal proteins using isotope-coded affinity tags and mass spectrometry. Nat Biotechnol. 2001;19:946–951. doi: 10.1038/nbt1001-946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Russell WK, Park ZY, Russell DH. Proteolysis in mixed organic-aqueous solvent systems: Applications for peptide mass mapping using mass spectrometry. Anal Chem. 2001;73:2682–2685. doi: 10.1021/ac001332p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Santoni V, Kieffer S, Desclaux D, Masson F, Rabilloud T. Membrane proteomics: use of additive main effects with multiplicative interaction model to classify plasma membrane proteins according to their solubility and electrophoretic properties. Electrophoresis. 2000;21:3329–3344. doi: 10.1002/1522-2683(20001001)21:16<3329::AID-ELPS3329>3.0.CO;2-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Santoni V, Malloy M, Rabilloud T. Membrane proteins and proteomics: un amour impossible? Electrophoresis. 2000;21:1054–1070. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1522-2683(20000401)21:6<1054::AID-ELPS1054>3.0.CO;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schröder B, Hasilik A. A protocol for combined delipidation and fractionation of membrane proteins using organic solvents. Anal Biochem. 2006;357:144–146. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2006.05.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Simoes-Barbosa A, Santana JM, Teizeira ARL. Solubilization of delipidated macrophage membrane proteins for analysis by two-dimensional electrophoresis. Electrophoresis. 2000;21:641–644. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1522-2683(20000201)21:3<641::AID-ELPS641>3.0.CO;2-H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stevens TJ, Arkin IT. Do more complex organisms have a greater proportion of membrane proteins in their genomes? Proteins. 2000;39:417–420. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0134(20000601)39:4<417::aid-prot140>3.0.co;2-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tabb DL, McDonald WH, Yates JR., 3rd DTA select and contrast: tools for assembling and comparing protein identifications from shotgun proteomics. J Prot Res. 2002;1:21–26. doi: 10.1021/pr015504q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Washburn MP, Wolters D, Yates JR., 3rd Large-scale analysis of the yeast proteome by multidimensional protein identification technology. Nat Biotechnol. 2001;19:242–247. doi: 10.1038/85686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wu CC, MacCoss MJ, Howell KE, Yates JR., 3rd A method for the comprehensive proteomic analysis of membrane proteins. Nat Biotechnol. 2003;21:532–538. doi: 10.1038/nbt819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wu CC, Yates JR. The application of mass spectrometry to membrane proteomics. Nat Biotechnol. 2003;21:262–267. doi: 10.1038/nbt0303-262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yu YQ, Gilar M, Gebler JC. A complete peptide mapping of membrane proteins: a novel surfactant aiding the enzymatic digestion of bacteriorhodopsin. Rapid Commun Mass Spectrom. 2004;18:711–715. doi: 10.1002/rcm.1374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zuobi-Hasona K, Crowley PJ, Hasona A, Bleiweis AS, Brady JL. Solubilization of cellular membrane proteins from Streptococcus mutans for two-dimensional gel electrophoresis. Electrophoresis. 2005;26:1200–1205. doi: 10.1002/elps.200410349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.