Abstract

Aim

We have previously shown that inhibition of angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) significantly reduced intestinal epithelial cell (EC) apoptosis and improved morphometric intestinal adaptation in a mouse model of massive small bowel resection (SBR). This study attempted to further examine the downstream signaling factors in this system by blocking the action of angiotensin II (ATII), hypothesizing that this would lead to similar improvement of intestinal adaptation after SBR.

Method

Two groups of mice (C57BL/6J) underwent either a 60 % mid-intestinal resection (SBR group) or a transaction/re-anastomosis (Sham group). Because real-time PCR studies showed that only ATII receptor type1a (ATII-1a) expression was significantly increased after SBR, compared to SHAM mice, we decided to use the specific ATII-1a receptor antagonist Losartan, to block this signaling pathway. An additional two groups of mice received daily i.p. injections of Losartan (SBR+Losartan and Sham+Losartan group). At 7 days the adaptive response was assessed in the remnant gut including: villus height, crypt depth, EC apoptosis (TUNEL staining) and proliferation (BrdU incorporation). The apoptotic and proliferation signaling pathways were addressed by analysis of EC mRNA expression.

Result

SBR (with and without Losartan) led to a significant increase in villus height and crypt depth. Losartan treatment did not significantly change EC proliferation, but did significantly reduce EC apoptosis rates as compared to the non-treated SBR group. Losartan treatment was associated with a significant reduction of the bax-to-bcl-2 ratio and TNF-α expression after SBR compared to non treated groups. Interestingly, Losartan treated groups showed a tremendous increase in proliferation signaling factors EGFR, KGFR and IL7R, which may indicate an expanded potential for further intestinal adaptation also beyond 7 days after SBR.

Conclusion

This study showed that the ATII-1a receptor may be of crucial importance for the modulation of intestinal EC apoptosis and proliferation, and for regulating the post-resectional EC adaptive response.

Keywords: Renin-angiotensin-system, angiotensin II receptor type1a (ATII-1a), small bowel resection

INTRODUCTION

Short bowel syndrome (SBS) is characterized as a state of maldigestion and malabsorption, and may occur with congenital anomalies or after massive small bowel resection (SBR). SBR leads to an adaptive response in residual intestine. Following SBR the residual intestine undergoes a series of adaptive processes in order to increase absorptive surface area and establish nutritional homeostasis. The exact mechanisms of post-resectional intestinal adaptation are incompletely understood, although a number of nutritive and nonnutritive factors have been identified as potential mediator of this compensatory intestinal response1–3. The adaptive processes which occur in the residual small intestine after SBR include marked changes in epithelial cell (EC) proliferation and enterocyte apoptosis rates4–9; which under normal physiologic circumstances are balanced, and shifts in favor of compensatory mucosal growth. Increases in EC proliferation may well occur via an up-regulation in a number of growth factors including epidermal growth factor (EGF) expression and EGF receptor (EGFR)10, 11; as well as a number of other growth factors including keratinocyte growth factor (KGF)12, IL-713, transforming growth factor alpha14, and glucagons like peptide 215.

An increase in the ratio between pro-apopotic and anti-apopotic factors has also been reported after massive SBR16. It is well documented that the bcl-2 family has an important role in the regulation of intestinal EC apoptosis via the intrinsic apoptotic pathway17–19. Two additional factors which mediate EC, tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) and Fas, have also been shown to be up-regulated after SBR in rodents4, 5, 20. These factors may therefore also be involved in the regulation of post-resectional EC apoptosis in the frame of the extrinsic apoptosis pathway.

The rennin-angiotensin-system (RAS) exerts multiple biological functions including cell growth, physiologic maintenance of blood pressure and perfusion, as well as mediation of inflammation contributing to the progression of tissue damage21, 22. Pharmacologic blockade of the actions of Angiotensin II (ATII) are known to have the beneficial effects of reduced inflammation in several organ systems (e.g., vasculature, kidney and liver) 21, 23, 24; however, the function of the RAS in the intestine is not well understood. Our laboratory has previously shown that ACE is expressed at particularly high levels in intestinal epithelium, and to be critically important in promoting the development of intestinal EC apoptosis20, 25, 26. The effect of ACE and ATII are mediated through a series of cell surface ATII receptors, and interestingly, these receptors are also found in the intestinal mucosa27. Our recent studies using pharmacologic ACE inhibitors (ACE-I) have shown that ACE-I significantly reduces EC apoptosis and moderates enhancement of intestinal adaptation (increased crypt depth and increased EC proliferation) after massive SBR20. Other investigators have reported that RAS mediation of apoptosis is via ATII signaling through its respective receptors in a number of organs and cells such as lung, prostate and endothelial cell28–30. Further, blockade of ATII by ACE-I or ATII receptor antagonists reduces injury effects and apoptosis, findings that were closely correlated to the reduction of TNF-α expression23, 24, 31, 32. Taken together, these findings suggested that ATII is a central mediator in the pathogenesis of intestinal adaption after massive SBR, and neutralization of ATII could be a beneficial therapeutic target through a reduction of this pro-apoptotic factor in the residual intestine.

In this study, we hypothesized that the ATII antagonist would influence post-resectional intestinal adaptation through changes in EC apoptosis and proliferation in an experimental model of SBS after massive SBR. Namely, antagonisms of ATII signaling would result in decreased EC apoptosis and increased intestinal adaptation after formation of SBS. To approach this question, we firstly investigated the expression of ATII receptor in intestine after massive SBR, and then examined the mechanisms in the process of enterocyte apoptosis and proliferation in this model.

MATERIAL and METHODS

Animal

Specific pathogen free, 8 week old male C57BL/6J mice (The Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME) were maintained in a 12-h night rhythm at 23°C and a relative humidity of 40–60%. A standard rodent chow (LabDiet® 5001Rodent Diet, PMI Nutrition International, LLC, Brentwood, MO) was switched to microstabilized rodent liquid diet (TestDiet, Richmond, IN) 2 days prior to surgery, and mice were maintained thereafter on liquid diet until harvest. All experiments reported here conformed to the guidelines for care and use of laboratory animals established by the University Committee on Use and Care of Animal at the University of Michigan, and protocols were approved by this Committee.

Experimental design

To investigate the post-resectional change in the role of the RAS, we firstly evaluated the expression of angiotensin II receptor on EC using real-time PCR in SBS and Sham model, and then examined potential mechanistic pathways. Four study groups were used: SBR, 60% mid-small bowel resection without Losartan treatment; SBR+ATII-1a, SBR mice given daily Losartan; Sham, transaction and reanastomosis without Losartan; and Sham+ATII-1a, Sham mice given daily Losartan.

Surgery

A 60% mid-small bowel resection was performed similar to that previously described20. Mice were anesthetized, a median laparotomy created, small bowel was either resected (SBR group) or small bowel transaction was performed (Sham-group). End-to-end anastomoses were performed with interrupted 8–0 monofilament sutures. The abdominal wall was closed in two layers. At the end of surgery mice were resuscitated with a 3 ml subcutaneous injection of warmed saline and allowed free access to water and liquid diet. Body weights were determined preoperatively and at harvest.

Treatment with AT II receptor antagonist

The ATII receptor type 1a (ATII-1a) antagonist Losartan, (10mg/kg/day i.p. Merck co, West point, PA) was given to a separate group of Sham and SBS mice starting one day prior to the surgery. In some experiments, mice were matched to a control group of non-operated mice; and were studied after a 7-day period.

Harvesting

Mice were euthanized 7-days after surgery using carbon dioxide asphyxiation. The small bowel (0.5cm) segments were preserved in 10% buffered formalin. Jejunal and ileal tissues were taken 3cm distal to ligament of Treitz and 3cm proximal to the ileocecal junction. Small bowel within 0.5 cm of the anastomotic sites was discarded. The remaining small bowel was immediately processed for mucosal cell isolation.

Histology

A 0.5-cm segment do mid-small bowl (at least 2 cm away from anastomosis) was fixed in 10% formaldehyde, and processed for hematoxylin and eosin staining. Villus height and crypt depth were measured using a calibrated micrometer. Each measurement consisted of a mean of measures derived from 16 different low power fields.

Epithelial cell proliferation

To examine the changes in intestinal crypt cell proliferation rate 5-bromo-2-deoxyuridine (BrdU) as an active cell division marker was used, as described previously20, 25. Mice were injected intraperitoneally with BrdU (50mg/kg, Roche Diagnostic, Indianapolis,IN) 1-hour before harvest. Paraffin-embedded section of 5 μm thickness were stained using BrdU In Situ Detection Kit II according to the manufacturer's guideline (BD PharMingen, San Jose,CA). An index of crypt cell proliferation rate was calculated using the ratio of the number of crypt cells incorporating BrdU to the total number of crypt cells. The total number of proliferating cells per crypt was defined as a mean ratio of proliferating cells in 16 well oriented crypts (counted at ×400 magnification).

Epithelial cell apoptosis assays

A terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase biotin-dUTP nick-end labeling(TUNEL) staining method was used for EC apoptosis assay, according to manufactures's instructions (ApopTag Plus Peroxidase In Situ Apoptosis Detection Kit, Chemicon International, Temecula, CA), with slight modification, as described previously20, 25. Assessment of apoptosis consisted of separate counting of all TUNEL positive EC in all well-oriented crypts and villi separately and dividing the total number of counted apoptotic cells per number of analyzed crypts and villi, respectively. Adding together of both crypt and villus apoptotic indices is expressed as the apoptotic index per crypt-villus complex (at 40× magnification).

Mucosal cell isolation and purification

Isolation of mucosal cells was performed using a previously described protocol33.

Real time polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR)

Real time PCR was performed from isolated RNA based on previous standard protocols using the ΔΔCt method20. All primers for selected gene sequences were designed using proprietary software (Lasergene, DNA star Inc, Madison, WI). Real-time PCR (RT-PCR) was performed using a Smart Cycler (Cepheid, Sunnyvale, CA) with intercalation of SYBR green I used to determine the amount of DNA using previously published techniques33. Expressions of result were normalized to β-actin expression.

Measurement of Mucosal and Mesenteric Blood Flow

To evaluate the effect of ATII-1a blockade on mesenteric blood flow, the laser Doppler perfusion imager (LDPI: Perimed Inc, North Royalton, OH) with computer software was used as previously described26. Briefly, in anesthetized mice (Naïve and Naïve+ATII-1a, n=5, in each group) a median laparotomy was performed and the mesentery exposed. A 670 nm helium-neon laser beam was placed 12-cm above the mesentery to sequentially scan the surface of mesentery and detect moving blood cells. Maximum, minimum, and mean percent perfusion was normalized to total pixel area. At the end of the measurement the mice were euthanized.

Statistical analysis

Data are reported as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Results were analyzed using t test for comparison of two means, and a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) for comparison of multiple groups. A post-hoc Bonferroni test was used to assess statistical difference between groups. The chi square test was used for categorical data (Prism software; GraphPad Software, Inc., San Diego, CA). A value of P<0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

RESULTS

Changes in AT II receptors expression after bowel resection

Increased ATII receptor type 1a (ATII-1a) after bowel resection

Real time-PCR showed a significantly increased expression of ATII-1a mRNA in the SBR group when compared to the Sham group (P <.05, N=6) (Table1). And there were no significant changes in the expression of other receptors.

Table 1.

mRNA expression of Angiotensin II (AT II) receptor in SBS

| ATII receptor, type1a | ATII receptor, type1b | ATII receptor, type2 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sham | 1.2±0.2 | 3.3±0.9 | 12.6±5.2 |

| SBR | 5.0±1.3* | 3.5±1.8 | 18.0±7.3 |

SBR, Short bowel Resection. ATII, Angiotensin II.

Expression of mRNA Angiotensin II (AT II) receptors on EC as detected by real time PCR. Result are expressed as 2−(−ΔΔCt) in relation to β-actin gene expression. AT II receptor type 1a mRNA expression was significantly increased in the SBR group compared to Sham group (P±.05). Data are expressed as mean ± SD.

Effect of ATII-1a blockade on small intestine epithelium

To understand the significance of increased altered ATII-1a expression on SBS adaptive changes, the ATII-1a antagonist, Losartan was given to a separate group of Sham and SBR mice. These mice were matched to an untreated (non-operated) group, and were studied after a 7-day period. All mice tolerated surgery well and showed no signs of intestinal obstruction at harvest.

Weight changes in the SBS model

Both Sham and SBR mice showed some degree of weight loss following surgery; however, the loss in each of these plateaued by the latter two days of the post-surgery period. The loss of weight in the SBR group was significantly greater than the Sham (percent change from weight at surgery: −18.5±2.2% versus −10.5±1.5%, respectively; P<.001). However, this loss was significantly attenuated in the SBR+ATII-1a group (−7.6±0.9%, P<.001). There was no significant difference in weight loss between the Sham+ATII-1a group versus the Sham group (−4.2±1.8%, P>.05).

ATII-1a blockade significantly altered mucosal morphometry

The adaptive responses after SBR are shown inTable 2. Both, villus height and crypt depth significantly increased after SBR as compared to Sham group. Losartan administration to SBS mice (SBS+ATII-1a) resulted in a significant increase in villus height, but failed to influence the increase in crypt depth beyond that seen in untreated SBS mice. Those mice undergoing a sham resection and treated with ATII-1a blockade (Sham+ATII-1a) showed no significant alteration in histological features in either crypt depth or villus height when compared with the Sham group.

Table 2.

Villus-crypt morphology and epithelial cell apoptosis and proliferation rates

| Villus height (μm) | Crypt depth (μm) | Apoptosis index | Proliferation rate | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sham | 202±19 | 100±5 | 0.05±0.02 | 20.2±3.2 |

| SBR | 312±9* | 150±9* | 0.11±0.03* | 35.2±2.1* |

| Sham+ATII-1a | 221±22 | 112±8 | 0.01±0.02 | 22.6±3.3 |

| SBR+ATII-1a | 332±19** | 148±7** | 0.03±0.03**# | 38.6±1.2** |

Abbreviations: SBR, Short bowel Resection; ATII, Angiotensin II; ATII-1a represents the groups treated with an ATII-1a antagonist (Losartan).

Data are expressed as the mean ± SD. Note significant difference in Villus height and crypt depth between Sham and SBR with/without ATII-1a treatment. Significant post-resectional increases in epithelial cell apoptosis and proliferation rate with/without the ATII-1a antagonist treatment. However, ATII-1a blockade significantly reduced the apoptosis index compared with SBR mice without blockade.

P<.05 Sham vs SBR

P<.05 Sham+ATII-1a vs SBR+ATII-1a

P<.05 SBR vs SBR+ATII-1a

Effect of AT II receptor type 1a antagonist on epithelial apoptosis

Enterocyte apoptosis rates were significantly higher in the SBS group compared to Sham group (Table 2), in agreement with previous studies4, 20, 34. Administration of an ATII -1a antagonist resulted in a significant decline in EC apoptosis rates in both the SBS and Sham groups. EC apoptosis decreased five-fold when compared with the untreated SBS group. These levels declined to those similar to that observed in the Sham group mice.

Mechanism of ATII receptor type 1a antagonist-mediated EC apoptosis

To investigate this mechanisms which led to the decline in EC apoptotic rates with Losartan, several factors in the both the intrinsic (bcl-2 family) and extrinsic (TNF-α and Fas) components of apoptotic signaling were investigated.

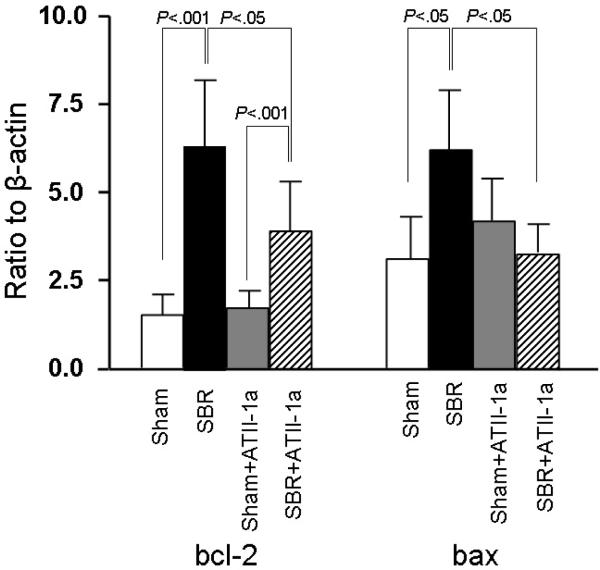

Intrinsic pathway

The mRNA expression of anti-apoptotic factor bcl-2, a member of the bcl-2 family, showed a significant increase in the SBR group compared to Sham group (P<.001) (Figure1). The expression of bcl-2 significantly decreased with Losartan treatment in SBR mice (P<.05). Interestingly, Losartan treatment did not significantly affect Sham control mice. The expression of the pro-apoptotic factor bax increased significantly after SBR group compared to Sham group (P<.05) (Figure1). ATII-1a blockade led to a significant decline in bax expression in SBR+ATII-1a group (P<.05).

Figure 1.

mRNA expression of bcl-2 and bax derived from epithelial cell samples in each group and measured by real time PCR. Result are expressed as 2 −(−ΔΔCt) in relation to β-actin expression. Expression of both bcl-2 and bax were significantly increased in the SBR group compared to the Sham group. Administration of Losartan (expressed in figure as ATII-1a) to SBR mice significantly reduced the expression of bcl-2 and bax; however, the reduction in bax fell to levels not significantly different than non-treated Sham mice. Results are shown as the mean±SD. Statistical comparisons are made using ANOVA with post hoc Bonferroni test.

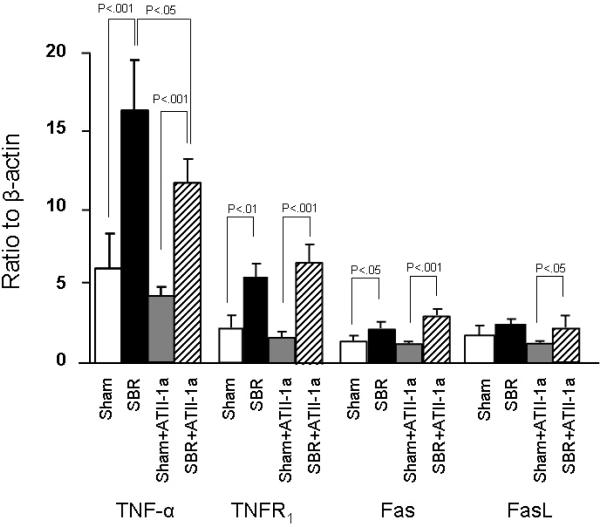

Extrinsic pathway

Gene expression of the investigated members of the extrinsic apoptotic pathways (TNF-α, TNF receptor 1 (TNFR1), Fas and FasL) was performed next. Interestingly, SBR led to an increased expression of TNF-α, TNFR1, Fas and although not significant, an increase in FasL. Mice treated with Losartan showed a similar increase compared to Sham mice in each of these factors (Figure 2). SBR mice treated with Losartan did show a significant decline in TNF-α compared to the untreated SBR group; however the level of TNF- α remained significantly higher than Sham+ATII-1a mice.

Figure 2.

mRNA expression of the extrinsic apoptotic pathways as detected by real time PCR. Result are expressed as 2 −(−ΔΔCt) in relation to β-actin expression. Note that gene expression of all tested factors were increased in SBR mice, regardless of whether mice received Losartan (expressed in figure as ATII-1a) or not. Results are expressed as mean ± SD. Statistical comparisons are made using ANOVA with post hoc Bonferroni test.

Effect of ATII receptor type 1a antagonism on epithelial cell proliferation

To better understand the implication of AT II-1a blockade on the SBR adaptation, EC proliferation was assessed with BrdU incorporation (Table 2). SBR led to a significantly increased level of proliferation compared to Sham mice. Losartan treatment, however, increased this level of proliferation, and levels of proliferation were actually higher (P<0.05) in Losartan treated mice compared with untreated SBR mice.

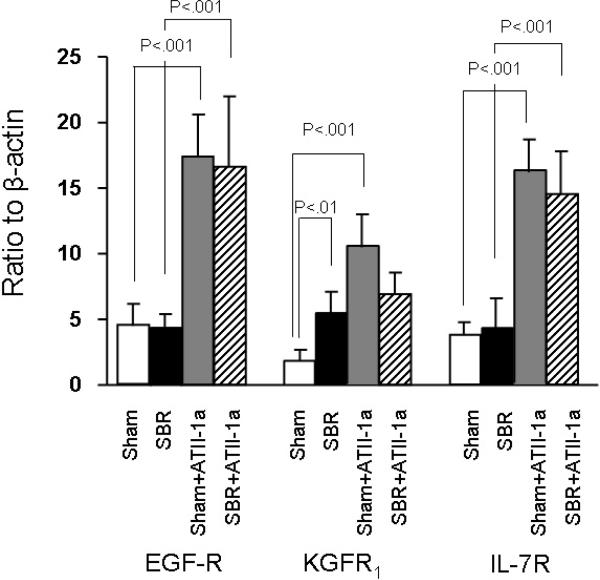

Mechanisms of ATII receptor type 1a antagonism-mediated epithelial cell proliferation

To investigate the mechanisms which resulted in the differences in EC apoptosis and proliferation rates, mRNA expressions of KGFR1, IL-7R and EGF-R were studied. We found that administration of ATII-1a blockade led to a markedly increased expression of each of these growth factor receptors. Further this increase was noted in both Sham and SBR mice. However, Losartan treatment was not significantly higher in the SBR mice compared to the Sham controls.

Effect of ATII receptor type 1a blockade on intestinal blood flow

Mesenteric blood flow measurements showed slightly lower levels in ATII-1a treated group compared to untreated group; however, the values were not significantly different between the two groups (2.7±0.3 versus 2.5±0.1, respectively; expressed in arbitrary units).

DISCUSSION

In this study, we demonstrated several finding. First, the increase in EC-derived ATII type 1a receptor expression after formation of SBS was confirmed with real-time PCR. We hypothesized that this increase in EC-derived ATII type 1a receptor may be associated with the intestinal EC adaptive process after SBR. To determine the functional role of angiotensin II signaling via the ATII type1a receptor in the intestinal mucosa, we used the ATII-1a specific antagonist, Losartan. Losartan treatment significantly decreased EC apoptosis and increased epithelial proliferation in the small intestine after SBR. This suggested a potential mechanism for SBR adaptation, and a mode of treatment which could be used to augment this adaptation. Additionally, our study showed that secondary formation of intestinal adaptation after massive SBR was associated with increased expression of TNF-α, bcl-2 and bax, and these factors may well play an important role in the development of adaptation4, 20, 25. Finally, treatment with Losartan led to a change in the expression of several pro-apoptotic signaling factors including a decline in TNF-α, Bax and Bcl-2; suggesting that inhibition of the TNF-α signaling pathway is a potential mechanism for the prevention of intestinal apoptosis.

ATII has been identified as the principal mediator of RAS function. ATII may mediate its action via at least two receptors ATII type 1 (a and b) and type 2 which are expressed by various cells, including immune mediating cells (e.g., T-cells and macrophages). Several investigators have shown that ATII is implicated as promoters of apoptosis in other organ systems28, 29, 35. ATII, produced by ACE, is necessary for the mediation of apoptosis in pulmonary and vascular smooth muscle cells21, 31. Although it has been demonstrated that RAS is highly expressed in small and large intestine of rodents and humans27, 36, and our previous studies have demonstrated that RAS has an important role in intestinal adaptation after SBR20, 25; however, it is not understood how ATII mediates this action these adaptive actions. Based on our finding of increased ATII-type1a receptor expression on intestinal mucosa after SBR, our laboratory investigated the role of ATII-1a in intestinal adaptation using a SBR model.

ATII-1a signaling is is known to clearly affect the blood flow and blood pressure. In order to rule out the possibility that major alternations in mesenteric blood flow could account for the observed changes in apoptosis and proliferation. Doppler blood flows were determined. We found no significant change in blood flow between ATII-1a treated and untreated mice, suggesting that alterations in blood flow had little to no effect on the ATII-1a associated adaptation.

After massive SBR intestinal adaptation is structurally characterized by an increase in EC proliferation and EC apoptosis rate. Although mechanisms leading to increased EC apoptosis after SBR are incompletely understood, the pro-apoptotic protein bax and other members of the intrinsic apoptotic pathway play a crucial role4–7, 9, 16, 37; as well, regulatory linkage between the intrinsic and extrinsic apoptotic pathway has also been speculated5. Our findings of in increase in several of these regulatory factors in the present study are consistent with previous reports4, 5, 9, 38, supporting both apoptotic pathways in the regulation of post-resectional EC apoptosis. In contrast, the administration of ATII-1a blockade (Losartan) showed a similar increase in expression of bcl-2 but an unchanged expression of bax after SBR. This led to significant reduction in the bax to bcl-2 ratio in Losartan treated mice; and this ratio of factors has been shown to be a valuable indicator for modulating the development of apoptosis4, 6, 16, 37. Recent studies have linked apoptosis mediated by the intrinsic pathway to the local RAS; and the mediation of apoptosis appears to be through the bcl-2 family, including a decrease in the bax to bcl-2 ratio39–41. Blockade of ATII signaling, via either an ACE-inhibitor or selective blockade of ATII receptors have been shown to effectively reduce apoptosis rates in various tissue20, 39, 40. Another potential mechanism of the increase in post-SBR EC apopotosis may be via TNF-α. In the present study intestinal mucosa expression of TNF-α was increased after SBR, and administration of Losartan significantly reduced this expression. This down-regulation of TNF-α, suggests that this may be a mechanism by which blockade of ATII-1a reduced apoptosis. Further, this finding is similar to the results of other investigators examining mediation of apoptosis in cardiac and pulmonary tissue42, 43.

Another signaling pathway for EC apoptosis is via Fas/Fas-ligand (FasL) signaling. In the present study we did detected an increase in either Fas or Fas-L mRNA expression after SBR; as well, this was not influenced by the administration of Losartan. This finding is distinct from other investigators who showed that activation of Fas stimulates alveolar EC to synthesize ATII de novo 44. These same investigators also showed that the autocrine synthesis of ATII was found to be required for the induction of apoptosis via Fas, and apoptosis could be abrogated by ACE-inhibitor or selective blockade of ATII receptors44. Our findings suggest, at least within the intestinal mucosa, that the Fas/Fas-L extrinsic pathway is not involved to RAS in SBR associated EC apoptosis.

SBR mice showed significantly higher EC proliferation rates compared with Sham mice. Additionally, there was a slight increase in EC proliferation and a marked decline in EC apoptosis in the Losartan treated groups. These two changes in the EC was associated with a markedly higher gene expression of the growth factor receptors KGFR1, EGF-R, IL-7R, compared with the untreated groups. It is possible that the up-regulation of these receptors may well explain the observed increase in EC proliferation33, 45–48; and signaling through several growth factors, including the 3 studied, may also lead to a down-regulation of apoptosis47, 49. These differences in EC apoptosis and proliferation rates were reflected in the intestinal morphology by means of greater crypt depth and villus height in the intestinal epithelium of Losartan treated mice compared to untreated mice. Therefore, we consider that signaling via the ATII receptor type1a is an important modulator of intestinal homeostasis during intestinal adaptation.

In conclusion, SBR was associated with a previously undescribed increase in the expression of ATII type1a receptor in the intestinal epithelium. Another novel finding was that administration of the ATII-1a antagonist Losartan reduced SBR-associated EC apoptosis rates and increased EC proliferation; suggesting that ATII-1a signaling may have a similar action on intestinal epithelial cells as has been previously seen in other organ systems. Possible anti-apoptotic mechanisms of Losartan in the intestinal tract may be through RAS by the reduction in the bax to bcl-2 ratio after SBR; and the proliferative effects may be via an increase in the expression of epithelial cell receptors for several growth factors. It is potentially possible that SBS patients mat benefit from used of an ATII-1a antagonist, facilitating the degree of adaptation. Future investigation will hopefully offer greater insight into the action of ATII on the gastrointestinal mucosa.

Figure 3.

mRNA expression of EGF-R, KGFR1, IL-7R. Note the significantly higher expression of these receptors in the Losartan (expressed in figure as ATII-1a) treated mice. Statistical comparisons are made using ANOVA with post hoc Bonferroni test.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH Grant 2R01-AI044076-10.

Reference

- 1.Ray EC, Avissar NE, Sax HC. Growth factor regulation of enterocyte nutrient transport during intestinal adaptation. Am J Surg. 2002;183(4):361–71. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(02)00805-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rubin DC, Levin MS. Intestinal adaptation: molecular analyses of a complex process. Gastroenterology. 1998;115(5):1291–4. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(98)70105-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tappenden KA. Mechanisms of enteral nutrient-enhanced intestinal adaptation. Gastroenterology. 2006;130(2 Suppl 1):S93–9. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.11.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Haxhija EQ, Yang H, Spencer AU, et al. Influence of the site of small bowel resection on intestinal epithelial cell apoptosis. Pediatr Surg Int. 2006;22(1):37–42. doi: 10.1007/s00383-005-1576-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tang Y, Swartz-Basile DA, Swietlicki EA, et al. Bax is required for resection-induced changes in apoptosis, proliferation, and members of the extrinsic cell death pathways. Gastroenterology. 2004;126(1):220–30. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2003.10.077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Korsmeyer SJ, Shutter JR, Veis DJ, et al. Bcl-2/Bax: a rheostat that regulates an anti-oxidant pathway and cell death. Semin Cancer Biol. 1993;4(6):327–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Potten CS, Booth C, Pritchard DM. The intestinal epithelial stem cell: the mucosal governor. Int J Exp Pathol. 1997;78(4):219–43. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2613.1997.280362.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Helmrath MA, Erwin CR, Shin CE, Warner BW. Enterocyte apoptosis is increased following small bowel resection. J Gastrointest Surg. 1998;2(1):44–9. doi: 10.1016/s1091-255x(98)80102-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stern LE, Huang F, Kemp CJ, et al. Bax is required for increased enterocyte apoptosis after massive small bowel resection. Surgery. 2000;128(2):165–70. doi: 10.1067/msy.2000.107370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Falcone RA, Jr., Shin CE, Erwin CR, Warner B. The adaptive intestinal response to massive enterectomy is preserved in c-SRC-deficient mice. Journal of Pediatric Surgery. 1999;34(5):800–4. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3468(99)90376-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Helmrath MA, Shin CE, Erwin CR, Warner BW. The EGF/EGF-receptor axis modulates enterocyte apoptosis during intestinal adaptation. J Surg Res. 1998;77(1):17–22. doi: 10.1006/jsre.1998.5362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yang H, Antony PA, Wildhaber BE, Teitelbaum DH. Intestinal intraepithelial lymphocyte gammadelta-T cell-derived keratinocyte growth factor modulates epithelial growth in the mouse. J Immunol. 2004;172(7):4151–8. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.7.4151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Haxhija EQ, Yang H, Spencer AU, et al. Intestinal epithelial cell proliferation is dependent on the site of massive small bowel resection. Pediatr Surg Int. 2007;23:379–390. doi: 10.1007/s00383-006-1855-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sukhotnik I, Yakirevich E, Coran AG, et al. Effect of transforming growth factor-alpha on intestinal adaptation in a rat model of short bowel syndrome. Journal of Surgical Research. 2002;108(2):235–42. doi: 10.1006/jsre.2002.6556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Koopmann M, Nelson D, Murali S, et al. Exogenous glucagon-like peptide-2 (GLP-2) augments GLP-2 receptor mRNA and maintains proglucagon mRNA levels in resected rats. JPEN. 2008;32(3):254–65. doi: 10.1177/0148607108316198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stern LE, Falcone RA, Jr., Huang F, et al. Epidermal growth factor alters the bax:bcl-w ratio following massive small bowel resection. J Surg Res. 2000;91(1):38–42. doi: 10.1006/jsre.2000.5897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Haxhija EQ, Yang H, Spencer AU, et al. Influence of the site of small bowel resection on intestinal epithelial cell apoptosis. Pediatr Surg Int. 2006;22(1):37–42. doi: 10.1007/s00383-005-1576-5. http://www.pubmedcentral.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=nihms&artid=1509096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jarboe MD, Juno RJ, Bernal NP, et al. Bax deficiency rescues resection-induced enterocyte apoptosis in mice with perturbed EGF receptor function. Surgery. 2004;136(2):121–6. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2004.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bernal NP, Stehr W, Coyle R, et al. Epidermal growth factor receptor signaling regulates Bax and Bcl-w expression and apoptotic responses during intestinal adaptation in mice. Gastroenterology. 2006;130(2):412–23. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wildhaber BE, Yang H, Haxhija EQ, et al. Intestinal intraepithelial lymphocyte derived angiotensin converting enzyme modulates epithelial cell apoptosis. Apoptosis. 2005;10(6):1305–15. doi: 10.1007/s10495-005-2138-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rodriguez-Vita J, Sanchez-Lopez E, Esteban V, et al. Angiotensin II activates the Smad pathway in vascular smooth muscle cells by a transforming growth factor-beta-independent mechanism. Circulation. 2005;111(19):2509–17. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000165133.84978.E2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Paul M, Mehr A, Kreutz R. Physiology of Local Renin-Angiotensin Systems. Physiol Rev. 2006;86:747–803. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00036.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Peters H, Border WA, Noble NA. Targeting TGF-beta overexpression in renal disease: maximizing the antifibrotic action of angiotensin II blockade. Kidney Int. 1998;54(5):1570–80. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.1998.00164.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xu W, Song S, Huang Y, Gong Z. Effects of perindopril and valsartan on expression of transforming growth factor-beta-Smads in experimental hepatic fibrosis in rats. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;21(8):1250–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2006.04331.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Haxhija EQ, Yang H, Spencer AU, et al. Modulation of mouse intestinal epithelial cell turnover in the absence of angiotensin converting enzyme. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2008;295(1):G88–G98. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00589.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Spencer AU, Yang H, Haxhija EQ, et al. Reduced severity of a mouse colitis model with angiotensin converting enzyme inhibition. Dig Dis Sci. 2007;52(4):1060–70. doi: 10.1007/s10620-006-9124-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hirasawa K, Sato Y, Hosoda Y, et al. Immunohistochemical localization of angiotensin II receptor and local renin-angiotensin system in human colonic mucosa. J Histochem Cytochem. 2002;50(2):275–82. doi: 10.1177/002215540205000215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang R, Ibarra-Sunga O, Verlinski L, et al. Abrogation of bleomycin-induced epithelial apoptosis and lung fibrosis by captopril or by a caspase inhibitor. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2000;279(1):L143–51. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.2000.279.1.L143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.de Resende MM, Greene AS. Effect of ANG II on endothelial cell apoptosis and survival and its impact on skeletal muscle angiogenesis after electrical stimulation. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2008;294(6):H2814–21. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00095.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yu W, Zhao YY, Zhang ZW, et al. Angiotension II receptor 1 blocker modifies the expression of apoptosis-related proteins and transforming growth factor-beta1 in prostate tissue of spontaneously hypertensive rats. BJU Int. 2007;100(5):1161–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2007.07150.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chen CM, Chou HC, Hsu HH, Wang LF. Transforming growth factor-beta1 upregulation is independent of angiotensin in paraquat-induced lung fibrosis. Toxicology. 2005;216(2–3):181–7. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2005.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rumble JR, Gilbert RE, Cox A, et al. Angiotensin converting enzyme inhibition reduces the expression of transforming growth factor-beta1 and type IV collagen in diabetic vasculopathy. J Hypertens. 1998;16(11):1603–9. doi: 10.1097/00004872-199816110-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yang H, Antony PA, Wildhaber BE, Teitelbaum DH. Intestinal intraepithelial lymphocyte gamma delta-T cell-derived keratinocyte growth factor modulates epithelial growth in the mouse. J Immunol. 2004;172(7):4151–8. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.7.4151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Haxhija EQ, Yang H, Spencer AU, et al. Intestinal epithelial cell proliferation is dependent on the site of massive small bowel resection. Pediatr Surg Int. 2007;23(5):379–90. doi: 10.1007/s00383-006-1855-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shan HY, Bai XJ, Chen XM. Apoptosis is involved in the senescence of endothelial cells induced by angiotensin II. Cell Biol Int. 2008;32(2):264–70. doi: 10.1016/j.cellbi.2007.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sechi LA, Valentin JP, Griffin CA, Schambelan M. Autoradiographic characterization of angiotensin II receptor subtypes in rat intestine. Am J Physiol. 1993;265(1 Pt 1):G21–7. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1993.265.1.G21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bernal NP, Stehr W, Profitt S, et al. Combined pharmacotherapy that increases proliferation and decreases apoptosis optimally enhances intestinal adaptation. J Pediatr Surg. 2006;41(4):719–24. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2005.12.016. discussion 719–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Berglund JJ, Riegler M, Zolotarevsky Y, et al. Regulation of human jejunal transmucosal resistance and MLC phosphorylation by Na(+)-glucose cotransport. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2001;281(6):G1487–93. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.2001.281.6.G1487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schiffrin EL. Vascular and cardiac benefits of angiotensin receptor blockers. Am J Med. 2002;113(5):409–18. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(02)01241-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Knott AW, O'Brien DP, Juno RJ, et al. Enterocyte apoptosis after enterectomy in mice is activated independent of the extrinsic death receptor pathway. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2003;285(2):G404–13. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00096.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Suzuki J, Iwai M, Nakagami H, et al. Role of angiotensin II-regulated apoptosis through distinct AT1 and AT2 receptors in neointimal formation. Circulation. 2002;106(7):847–53. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000024103.04821.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Flesch M, Hoper A, Dell'Italia L, et al. Activation and functional significance of the renin-angiotensin system in mice with cardiac restricted overexpression of tumor necrosis factor. Circulation. 2003;108(5):598–604. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000081768.13378.BF. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Li X, Zhang H, Soledad-Conrad V, et al. Bleomycin-induced apoptosis of alveolar epithelial cells requires angiotensin synthesis de novo. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2003;284(3):L501–7. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00273.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wang R, Zagariya A, Ang E, et al. Fas-induced apoptosis of alveolar epithelial cells requires ANG II generation and receptor interaction. Am J Physiol. 1999;277(6 Pt 1):L1245–50. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1999.277.6.L1245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Boismenu R, Havran WL. Modulation of epithelial cell growth by intraepithelial gamma delta T cells. Science. 1994;266(5188):1253–5. doi: 10.1126/science.7973709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Helmrath MA, Shin CE, Erwin CR, Warner BW. The EGF\EGF-receptor axis modulates enterocyte apoptosis during intestinal adaptation. J Surg Res. 1998;77(1):17–22. doi: 10.1006/jsre.1998.5362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Knott AW, Juno RJ, Jarboe MD, et al. EGF receptor signaling affects bcl-2 family gene expression and apoptosis after massive small bowel resection. J Pediatr Surg. 2003;38(6):875–80. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3468(03)00114-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Watanabe M, Ueno Y, Yajima T, et al. Interleukin 7 transgenic mice develop chronic colitis with decreased interleukin 7 protein accumulation in the colonic mucosa. J Exp Med. 1998;187(3):389–402. doi: 10.1084/jem.187.3.389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yang H, Wildhaber B, Tazuke Y, Teitelbaum DH. Keratinocyte growth factor stimulates the recovery of epithelial structure and function in a mouse model of total parenteral nutrition. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2002;26(6):333–40. doi: 10.1177/0148607102026006333. 2002 Harry M. Vars Research Award. discussion 340–1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]