Abstract

Purpose:

The effect of vitreopapillary adhesion (VPA) in macular diseases is not understood. Spectral-domain optical coherence tomography/scanning laser ophthalmoscopy (SD-OCT/SLO) was used to identify VPA in macular holes, lamellar holes, macular pucker, and dry age-related macular degeneration (AMD).

Methods:

Ultrasonography and SD-OCT/SLO were performed in 99 subjects: 17 with macular holes, 11 with lamellar holes, 28 with macular pucker, 15 with dry AMD, and 28 age-matched controls. Outcome measures were the presence of total posterior vitreous detachment (PVD) by ultrasound and the presence or absence of VPA and intraretinal cystoid spaces by SD-OCT/SLO.

Results:

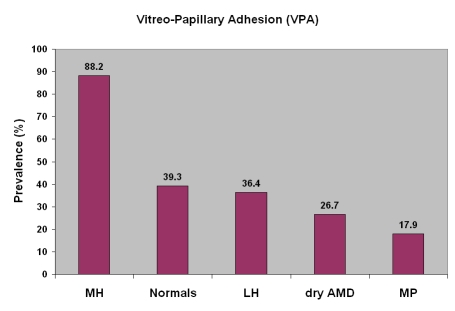

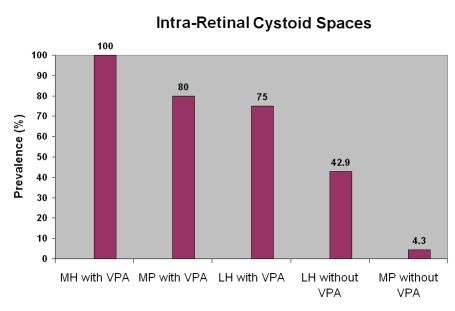

PVD was detected by ultrasound in 26 (92.9%) of 28 eyes with macular pucker, 6 (54.5%) of 11 eyes with lamellar holes (P = .01), and 4 (23.5%) of 17 eyes with macular holes (P = .000003). SD-OCT/SLO detected VPA in 15 (88.2%) of 17 eyes with macular holes, 11 (39.3%) of 28 age-matched controls (P = .002), 4 (36.4%) of 11 eyes with lamellar holes (P = .01), 4 (26.7%) of 15 eyes with dry AMD (P = .0008), and 5 (17.9%) of 28 eyes with macular pucker (P = .000005). Intraretinal cystoid spaces were present in 15 (100%) of 15 eyes with macular holes with VPA. In eyes with macular pucker, 4 (80%) of 5 with VPA had intraretinal cystoid spaces, but only 1 (4.3%) of 23 without VPA had intraretinal cystoid spaces (P = .001).

Conclusions:

VPA was significantly more common in eyes with macular holes than in controls or eyes with dry AMD, lamellar holes, or macular pucker. Intraretinal cystoid spaces were found in all eyes with macular holes with VPA. When present in macular pucker, VPA was frequently associated with intraretinal cystoid spaces. Although these investigations do not study causation directly, VPA may have an important influence on the vectors of force at the vitreoretinal interface inducing cystoid spaces and holes.

INTRODUCTION

Posterior vitreous detachment (PVD) usually results in innocuous separation of vitreous from retina. Anomalous PVD is the consequence of gel liquefaction without sufficient dehiscence at the vitreoretinal interface, causing a variety of untoward sequelae.1 When anomalous PVD involves persistent adherence at the optic disc, vitreopapillary adhesion (VPA) can cause optic nerve dysfunction.2–5 What is not known is whether VPA plays a role in macular diseases such as macular holes, macular pucker, and age-related macular degeneration (AMD). Furthermore, it is not known whether the presence or absence of VPA is associated with certain macular pathologies, such as intraretinal cystoid spaces. Indeed, while intraretinal cystoid spaces are known to occur in various maculopathies6–13 and while localized perifoveal vitreous detachment may cause anterior traction, resulting in foveal cysts without macular hole formation or capillary leakage,14 an association between VPA and cystoid spaces in these diseases has not yet been investigated.

It is plausible that persistent vitreous attachment to the optic disc can influence the vectors of force exerted by vitreous on the macula and might therefore play a role in macular diseases, especially macular holes. This study was therefore designed to test the hypothesis that VPA is more commonly found in full-thickness macular holes than in lamellar holes, macular pucker, dry AMD, and age-matched controls. It was also hypothesized that when present in macular holes and macular pucker, VPA would be more commonly associated with intraretinal cystoid spaces.

METHODS AND MATERIALS

The Institutional Review Board of St Joseph Hospital, Orange, California, approved the study, and informed consent was given by all participants. There were 99 subjects: 17 with macular holes, 11 with lamellar holes, 28 with macular pucker, 15 with dry AMD, and 28 normal controls. Controls were age-matched to eliminate any influence of aging. The mean ages in each group are listed in Table 1 along with statistical analyses demonstrating that there were no significant differences between the groups. There were also no statistically significant differences in the gender distributions between the various groups in this study.

TABLE 1.

MEAN AGE OF EACH PARTICIPANT GROUP

| MH | CONTROL | LH | DRY AMD | MP | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean Age | 65.9±6.1 | 65.5±8.4 | 67±9.5 | 70.3±6.4 | 69.8±9.2 |

| Control | LH | dry AMD | MP | ||

| Age ComparisonPvalue | MH | 0.9 | 0.7 | 0.05 | 0.1 |

| Control | 0.6 | 0.06 | 0.07 | ||

| LH | 0.3 | 0.4 | |||

| Dry AMD | 0.8 | ||||

| Gender ComparisonPvalue | MH | 0.54 | 0.25 | 0.28 | 0.12 |

| Control | 0.48 | 0.52 | 0.28 | ||

| LH | 1 | 1 | |||

| Dry AMD | 1 | ||||

AMD, age-related macular degeneration; LH, lamellar hole; MH, macular hole; MP, macular pucker.

All subjects were evaluated at the VMR Institute in Huntington Beach, California, between February 2007 and December 2008. Exclusion criteria were the presence of diabetic retinopathy, retinal detachment, intraocular inflammation, ocular trauma, and a history of vitreoretinal surgery. Ultrasonography and spectral-domain optical coherence tomography/scanning laser ophthalmoscopy (SD-OCT/SLO) were performed in all subjects.

ULTRASONOGRAPHY

The presence of a PVD was determined by high-gain, real-time ultrasonography (10-MHz probe; Quantel Medical Inc, Bozeman, Montana). A through-the-lid contact technique with both horizontal and vertical views was used, and the mobility of the posterior vitreous was examined during saccadic eye movements.

SD-OCT/SLO IMAGING

Fundus imaging was performed using the SD-OCT/SLO instrument (OPKO/Ophthalmic Technologies Inc, Toronto, Ontario). Longitudinal imaging was used to determine the presence of intraretinal cystoid spaces. Staging of macular holes and macular puckers was performed according to the Gass classifications.15,16 Using the calibrated digital calipers of the SD-OCT/SLO software, macular hole diameters were measured (Figure 1) at four axes (45°, 90°, 135°, and 180°), and an average of the four measurements was computed for each eye and used for macular hole staging. Lamellar holes were diagnosed according to the criteria proposed by Haouchine and associates17 and Witkin and associates.18

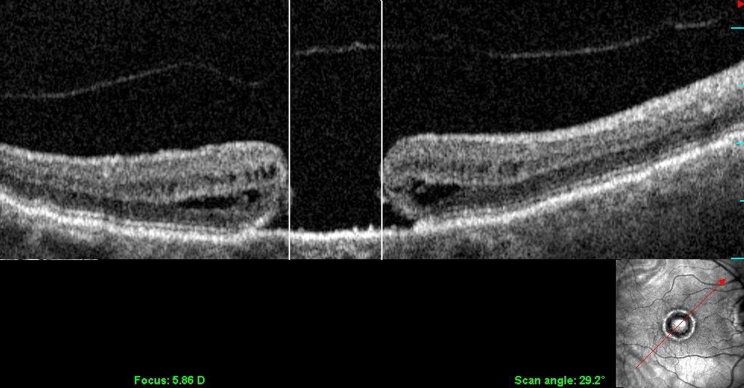

FIGURE 1.

Longitudinal OCT/SLO scan (SLO image in lower righthand corner) illustrating the measurement of a stage 4 macular hole, determined by the distance between the vertical lines.

SD-OCT/SLO was used to evaluate the optic nerve head for VPA by obtaining images that centered the optic disc in the scanned field. The presence of VPA was established when a prominent vitreous membrane was found to be attached to the borders of the optic disc.

STATISTICAL ANALYSES

Two-sample t test assuming equal variance and Fisher exact test were used for the analyses. P values of .05 or less were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

MACULAR HOLE

The clinical characteristics of this group are shown in Table 2. There were 17 eyes with full-thickness macular hole (5 men [29.4%], 12 women [70.6%]; average age, 65.9 ± 6.1 years). The diameter of the macular holes ranged from 205 to 1240 μm with a mean size of 485 μm. Based on the measurements of macular hole diameter and the presence or absence of vitreous attachment to the edge of the macular holes, 8 of 17 eyes (47.1 %) had stage 2 macular holes, 7 of 17 (41.2%) had stage 3 macular holes, and 2 of 17 (11.8%) had stage 4 macular holes. The macular hole stage was positively correlated with the macular hole diameter (P < .001).

TABLE 2.

CLINICAL CHARACTERISTICS OF 17 EYES WITH MACULAR HOLE

| AGE (yr) | SEX | BCVA | EYE | VPA |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 50 | F | 20/60-2 | OD | Y |

| 62 | F | 20/50+3 | OD | Y |

| 69 | M | 20/100-1 | OD | Y |

| 67 | M | 20/20-2 | OS | Y |

| 58 | F | 20/64-1 | OD | Y |

| 70 | M | 20/140-1 | OS | Y |

| 67 | F | 20/50-2 | OS | Y |

| 70 | F | 20/80+1 | OS | Y |

| 67 | F | 20/400 | OS | Y |

| 67 | F | CF'8 | OD | Y |

| 64 | F | 20/100 | OD | Y |

| 60 | M | 20/400 | OS | Y |

| 76 | F | 20/140 | OD | Y |

| 65 | F | 20/100+2 | OS | Y |

| 67 | F | 20/400 | OS | Y |

| 75 | M | 20/140 | OS | N |

| 66 | F | 20/CF 4 feet | OD | N |

BCVA, best-corrected visual acuity; CF, counting fingers; VPA, vitreopapillary adhesion; N, no; Y, yes.

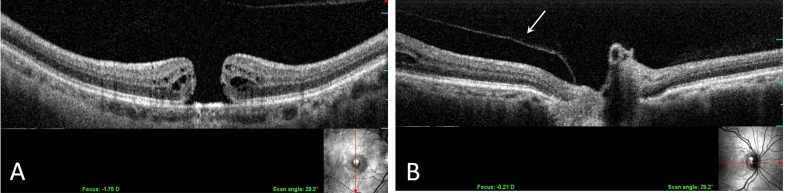

PVD was detected by ultrasonography in 4 of 17 eyes (23.5%). VPA (Figure 2) was detected by SD-OCT/SLO in 15 of 17 eyes (88.2%). Intraretinal cystoid spaces surrounding the macular holes were found in 15 (100%) of 15 eyes with macular holes with VPA.

FIGURE 2.

Longitudinal OCT/SLO image demonstrating a macular hole with the detachment of posterior vitreous cortex (A). The posterior vitreous cortex is attached to the optic disc (B).

LAMELLAR HOLES

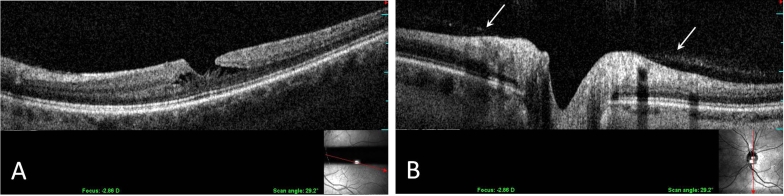

There were 11 eyes with lamellar holes (6 men [54.5%], 5 women [45.5%]; average age, 67 ± 9.5 years). The clinical characteristics of this group are shown in Table 3. PVD was detected by ultrasonography in 6 of 11 eyes (54.5%). SD-OCT/SLO imaging detected VPA (Figure 3) in 4 of 11 eyes (36.4%). No patients had both a PVD and VPA. Intraretinal cystoid spaces were detected in 3 of 4 eyes with VPA (75%). Of the 7 eyes without VPA, 3 of 7 (42.9%) had intraretinal cystoid spaces.

TABLE 3.

CLINICAL CHARACTERISTICS OF 11 EYES WITH LAMELLAR HOLE

| AGE (yr) | SEX | BCVA | EYE | VPA |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 43 | F | 20/20 | OS | Y |

| 71 | F | 20/30 | OD | Y |

| 68 | F | 20/80 | OD | Y |

| 78 | M | 20/100 | OS | Y |

| 70 | M | 20/30-2 | OD | N |

| 72 | M | 20/50-2 | OD | N |

| 71 | F | 20/30 | OD | N |

| 60 | F | 20/25-3 | OD | N |

| 60 | M | 20/20-1 | OD | N |

| 72 | M | 20/60-2 | OD | N |

| 72 | M | 20/30-1 | OD | N |

BCVA, best-corrected visual acuity; VPA, vitreopapillary adhesion; F, female; M, male; N, no; Y, yes.

FIGURE 3.

Longitudinal OCT-SLO imaging demonstrates a lamellar hole with intraretinal cysts (A). Vitreous adhesion is evident at the margins of the optic disc (B).

MACULAR PUCKER

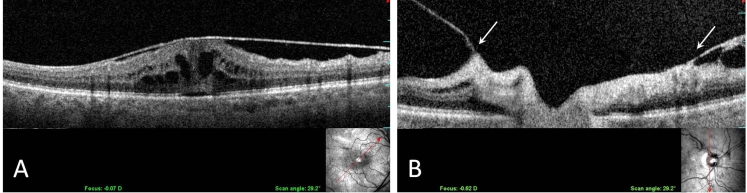

There were 28 eyes (16 men [57.1%], 12 women [42.9%]; average age, 69.8 ± 9.2 years) with grade 2 macular pucker, which appeared as wrinkling of the macula with linear striae. The clinical characteristics of this group are shown in Table 4. Ultrasonography detected the presence of PVD in 26 of 28 eyes (92.9%). SD-OCT/SLO imaging identified VPA in 5 of 28 eyes (17.9%). Of the 5 eyes with macular pucker and VPA, intraretinal cysts (Figure 4) were present in 4 eyes (80%), as compared to only 1 (4.3%) of the 23 eyes with macular pucker but no VPA (P = .001).

TABLE 4.

CLINICAL CHARACTERISTICS OF 28 EYES WITH MACULAR PUCKER

| AGE (yr) | SEX | BCVA | EYE | VPA |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 89 | M | 20/26-3 | OD | Y |

| 61 | F | 20/50 | OD | Y |

| 64 | F | 20/140+1 | OD | Y |

| 84 | M | 20/140 | OD | Y |

| 67 | M | 20/30-1 | OD | Y |

| 70 | M | 20/50-2 | OD | N |

| 57 | M | 20/30+2 | OD | N |

| 71 | M | 20/25-1 | OS | N |

| 85 | M | 20/100-2 | OS | N |

| 82 | M | 20/100 | OD | N |

| 56 | F | 20/40 | OS | N |

| 73 | M | 20/32-2 | OS | N |

| 52 | F | 20/80 | OD | N |

| 77 | F | 20/60-1 | OS | N |

| 59 | F | 20/20-1 | OS | N |

| 67 | M | 20/80-1 | OS | N |

| 71 | M | 20/26+3 | OD | N |

| 67 | M | 20/40-1 | OD | N |

| 65 | F | 20/40-3 | OD | N |

| 79 | M | 20/60-2 | OD | N |

| 74 | F | 20/30 | OS | N |

| 75 | M | 20/30+1 | OD | N |

| 72 | F | 20/40-2 | OS | N |

| 59 | M | 20/40 | OD | N |

| 75 | F | 20/80 | OD | N |

| 69 | M | 20/60 | OS | N |

| 65 | F | 20/20 | OS | N |

| 69 | F | 20/50-1 | OD | N |

BCVA, best-corrected visual acuity; VPA, vitreopapillary adhesion; F, female; M, male; No, no; Y, yes.

FIGURE 4.

Longitudinal OCT-SLO imaging demonstrates a macular pucker with intraretinal cystoid spaces (A) and vitreopapillary adhesion to both sides of the optic disc (B).

DRY AMD

There were 15 eyes (8 men [53.3%], 7 women [46.7%]; average age, 70.3 ± 6.4 years) with dry AMD. The clinical characteristics of this group are shown in Table 5. SD-OCT/SLO imaging detected VPA in 4 of 15 eyes (26.7%).

TABLE 5.

CLINICAL CHARACTERISTICS OF 15 EYES WITH DRY AMD

| AGE (yr) | SEX | BCVA | EYE | VPA |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 65 | M | 20/30+3 | OS | Y |

| 68 | F | 20/25+2 | OD | Y |

| 71 | F | 20/50 | OS | Y |

| 76 | F | NA | OD | Y |

| 52 | M | 20/20-2 | OD | N |

| 67 | M | 20/25+2 | OD | N |

| 68 | F | 20/40 | OS | N |

| 70 | M | 20/30+2 | OS | N |

| 70 | F | 20/80-2 | OD | N |

| 72 | F | 20/40-1 | OD | N |

| 72 | M | 20/25-2 | OS | N |

| 72 | F | 20/40-2 | OD | N |

| 77 | M | 20/30-2 | OD | N |

| 77 | M | 20/25 | OD | N |

| 78 | M | 20/40 | OD | N |

AMD, age-related macular degeneration; BCVA, best-corrected visual acuity; VPA, vitreopapillary adhesion; F, female; M, male; OD, right eye; OS, left eye; N, no; Y, yes.

AGE-MATCHED CONTROLS

There were 28 age-matched eyes (11 men [39.3%], 17 women [60.7%]; average age, 65.5 ± 8.4 years). The clinical characteristics of this group are shown in Table 6. SD-OCT/SLO imaging detected VPA in 11 of 28 eyes (39.3%).

TABLE 6.

CLINICAL CHARACTERISTICS OF 28 AGE-MATCHED CONTROL EYES

| AGE (yr) | SEX | EYE | VPA |

|---|---|---|---|

| 54 | F | OD | Y |

| 56 | M | OD | Y |

| 56 | M | OD | Y |

| 59 | F | OD | Y |

| 61 | M | OD | Y |

| 63 | F | OD | Y |

| 65 | M | OD | Y |

| 70 | F | OD | Y |

| 70 | F | OD | Y |

| 79 | F | OD | Y |

| 53 | F | OD | Y |

| 58 | F | OD | N |

| 59 | F | OD | N |

| 60 | F | OD | N |

| 61 | F | OD | N |

| 62 | M | OD | N |

| 63 | M | OD | N |

| 64 | F | OD | N |

| 64 | F | OS | N |

| 65 | M | OD | N |

| 65 | F | OD | N |

| 68 | M | OD | N |

| 69 | M | OD | N |

| 71 | F | OD | N |

| 72 | F | OD | N |

| 78 | F | OD | N |

| 83 | M | OD | N |

| 86 | M | OD | N |

VPA, vitreopapillary adhesion; M, male; F, female; OD, right eye; OS, left eye; N, no; Y, yes.

DISCUSSION

This study found that vitreopapillary adhesion (VPA) is far more prevalent in full-thickness macular holes (88.2%) than age-matched controls (39.3%; P = .002), lamellar holes (36.4%, P = .01), dry AMD (26.7%, P = .0008), and macular pucker (17.9%, P = .000005) (Figure 5). Thus, while VPA is important in some optic neuropathies,2–5 as well as in various ischemic retinopathies, such as proliferative diabetic vitreoretinopathy,19 the results of this study suggest that VPA is also important in macular holes. These observations with SD-OCT/SLO imaging confirm the ultrasonography findings of Van Newkirk and colleagues,20 who detected vitreous attachment to the peripapillary retina in 65 of 65 patients (100%) with stage 3 macular holes and pseudo-opercula. Thus, VPA may be causally associated with macular holes.

FIGURE 5.

Vitreopapillary adhesion (VPA) was found most prevalent in macular hole (MH) (88.2%) compared to age-matched controls (39.3%; P = .002), lamellar hole (LH) (36.4%, P = .01), dry age-related macular degeneration (AMD) (26.7%, P = .0008), and macular pucker (MP) (17.9%, P = .000005), suggesting that VPA may be causally associated with MH..

The possible pathogenic mechanism by which VPA contributes to macular hole formation could involve anomalous PVD and vitreoschisis,21 which has been implicated in the pathophysiology of both macular hole and macular pucker.22,23 Following anomalous PVD with vitreoschisis, the outer layer of the split posterior vitreous cortex remains attached to the macula. Inward (centripetal) tangential traction by the outer layer of the split posterior vitreous cortex likely throws the underlying retina into folds, resulting in macular pucker. If, however, vitreous is still attached to the optic disc, the vectors of force would be different, resulting in outward (centrifugal) tangential traction that induces central retinal dehiscence and a macular hole. Indeed, papillofoveal traction has previously been implicated in the pathogenesis of macular holes.24 Hence, while anomalous PVD may be the initial event, the presence or absence of VPA may influence the subsequent course and vectors of traction, especially in the presence of a perifoveal vitreous detachment.25

The results of this study suggest that in the absence of VPA, a macular pucker is more likely to be present, since VPA was detected in only 17.9% of macular pucker cases. In the presence of VPA, a macular hole is more likely to develop, since VPA was detected in 88.2% of macular hole cases (P = .000005), while lamellar hole possibly represents an intermediate stage in these events. In fact, previous studies6 have suggested that lamellar holes represent an “abortive” process of macular hole formation and that foveal pseudocysts with partial PVD become lamellar holes if the base is preserved and full-thickness macular holes if the outer retinal layer is disrupted.8 It is plausible that the vectors of force that result from VPA also contribute to the perifoveal vitreous detachment that Johnson and associates25 have proposed as the primary pathogenic event in macular hole formation. What’s more, intraretinal cystoid spaces may also be caused by VPA, since cysts were found more frequently in macular pucker with VPA (4 of 5, 80%) than macular pucker without VPA (1 of 23, 4.3%; P < .001). Figure 6 demonstrates that this is also the case in macular holes and lamellar holes, where VPA is highly associated with intraretinal cystoid spaces, whereas eyes without VPA have a low prevalence of cystoid spaces.

FIGURE 6.

Intraretinal cystoid spaces are more prevalent in eyes with vitreopapillary adhesion (VPA). In macular holes (MH) with VPA, 100% of eyes had cysts. In macular pucker (MP) with VPA, 80% of eyes had intraretinal cystoid spaces. Lamellar holes (LH) with VPA had cysts in 75% of eyes, whereas cysts were present in only 42.9% of LH without VPA. MP without VPA had cysts in only 1 of 23 eyes (4.3%).

The findings in dry AMD are of interest insofar as recent studies26–29 have shown that vitreomacular adhesion is a risk factor for choroidal neovascularization and exudative AMD. The absence of VPA in the overwhelming majority (73.3%) of eyes with dry AMD in the study reported herein corroborates these previous reports that found the presence of a total PVD was highly associated with the dry form of AMD. Thus, PVD without VPA was the most common finding in this present group of subjects. Future studies should explore the relationship between VPA and exudative AMD by establishing whether certain subtypes of wet AMD are more commonly associated with VPA.

In conclusion, the present findings support the hypothesis that VPA is significantly more common in full-thickness macular holes than in controls, dry AMD, lamellar holes, and macular pucker. When present in macular holes and macular pucker, VPA is very highly associated with intraretinal cystoid spaces. VPA is also far more common in macular pucker and macular holes with cysts, as compared to lamellar holes and macular pucker without cysts. Thus, while VPA is known to play a role in certain papillopathies2–5 and in diabetic vitreoretinopathy,3,19 the present study suggests that VPA is also important in certain vitreomaculopathies.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Funding/Support: This work was supported by the VMR Institute in Huntington Beach, California, and a Research to Prevent Blindness Medical Student Fellowship (M.Y.W.)

Financial Disclosures: None.

Author Contributions: Design of the study (J.S.); Conduct of the study (J.S., M.W., D.N.); Management, analysis, and interpretation of data (J.S., M.W., D.N., A.A.S.); Preparation, review, and approval of the manuscript (J.S., A.A.S.).

Conformity With Author Information: This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of St Joseph Hospital, Orange, California, and informed consent was given by all participants.

Portions of this study were originally published in Wang MY, Nguyen D, Hindoyan N, Sadun AA, Sebag J: Vitreo-papillary adhesion in macular hole and macular pucker. Retina 29:644-50, 2009

Other Acknowledgments: Laurie LaBrie of the University of Southern California assisted with the statistical analyses in this study. The authors thank Dr Rosen and Dr Garcia of the New York Eye and Ear Infirmary for their contributions to our research.

REFERENCES

- 1.Sebag J. Anomalous posterior vitreous detachment: a unifying concept in vitreo-retinal disease. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2004;242:690–698. doi: 10.1007/s00417-004-0980-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Foos RY, Roth AM. Surface structure of the optic nerve head. 2. Vitreopapillary attachments and posterior vitreous detachment. Am J Ophthalmol. 1973;76:622. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(73)90560-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kroll P, Wiegand W, Schmidt J. Vitreopapillary traction in proliferative diabetic vitreoretinopathy. Br J Ophthalmol. 1999;83:261–264. doi: 10.1136/bjo.83.3.261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sebag J. Vitreopapillary traction as a cause of elevated optic nerve head. Am J Ophthalmol. 1999;128:261–262. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Katz B, Hoyt WF. Gaze-evoked amaurosis from vitreopapillary traction. Am J Ophthalmol. 2005;139:631–637. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2004.10.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gaudric A, Haouchine B, Massin P, et al. Macular hole formation: new data provided by optical coherence tomography. Arch Ophthalmol. 1999;117:744–751. doi: 10.1001/archopht.117.6.744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Takahashi H, Kishi S. Tomographic features of a lamellar macular hole formation and a lamellar hole that progressed to a full-thickness macular hole. Am J Ophthalmol. 2000;130:677–679. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(00)00626-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Haouchine B, Massin P, Gaudric A. Foveal pseudocyst as the first step in macular hole formation: a prospective study by optical coherence tomography. Ophthalmology. 2001;108:15–22. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(00)00519-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jaffe GJ, Caprioli J. Optical coherence tomography to detect and manage retinal disease and glaucoma. Am J Ophthalmol. 2004;137:156–169. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(03)00792-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kishi S, Kamei Y, Shimizu K. Tractional elevation of Henle’s fiber layer in idiopathic macular holes. Am J Ophthalmol. 1995;120:486–496. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)72663-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Reese AB, Jones IS, Cooper WC. Macular changes secondary to vitreous traction. Am J Ophthalmol. 1967;64:544–549. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(67)90557-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McDonnell PJ, Fine SL, Hillis AI. Clinical features of idiopathic macular cysts and holes. Am J Ophthalmol. 1982;93:777–786. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(82)90474-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Morgan CM, Schatz H. Involutional macular thinning: a pre-macular hole condition. Ophthalmology. 1986;93:153–161. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(86)33767-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Johnson MW. Tractional cystoid macular edema: a subtle variant of the vitreomacular traction syndrome. Am J Ophthalmol. 2005;140:184–192. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2005.01.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gass JDM. Stereoscopic Atlas of Macular Diseases: Diagnosis and Treatment. Vol. 2. St Louis: Mosby; 1997. pp. 938–940. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gass JD. Reappraisal of biomicroscopic classification of stages of development of a macular hole. Am J Ophthalmol. 1995;119:752–759. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)72781-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Haouchine B, Massin P, Tadayoni R, Erginay A, Gaudric A. Diagnosis of macular pseudoholes and lamellar macular holes by optical coherence tomography. Am J Ophthalmol. 2004;138:732–739. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2004.06.088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Witkin AJ, Ko TH, Fujimoto JG, et al. Redefining lamellar holes and the vitreomacular interface: an ultrahigh-resolution optical coherence tomography study. Ophthalmology. 2006;113:388–397. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2005.10.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kroll P, Rodrigues EB, Hoerle S. Pathogenesis and classification of proliferative diabetic vitreoretinopathy. Ophthalmologica. 2007;221:78–94. doi: 10.1159/000098253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Van Newkirk MR, Johnson MW, Hughes JR, Meyer KA, Byrne SF. B-scan ultrasonographic findings in the stages of idiopathic macular hole. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 2000;98:163–169. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sebag J. Vitreoschisis. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2008;246:329–332. doi: 10.1007/s00417-007-0743-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sebag J, Gupta P, Rosen R, Garcia P, Sadun AA. Macular holes and macular pucker: the role of vitreoschisis as imaged by optical coherence tomography/scanning laser ophthalmoscopy. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 2007;105:121–131. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tanner V, Chauhan DS, Jackson TL, Williamson TH. Optical coherence tomography of the vitreoretinal interface in macular hole formation. Br J Ophthalmol. 2001;85:1092–1097. doi: 10.1136/bjo.85.9.1092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chuan DS, Antcliff RJ, Rai PA, Williamson TH, Marshall J. Papillofoveal traction in macular hole formation: the role of optical coherence tomography. Arch Ophthalmol. 2000;118:32–38. doi: 10.1001/archopht.118.1.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Johnson MW, Van Newkirk MR, Meyer KA. Perifoveal vitreous detachment is the primary pathogenic event in idiopathic macular hole formation. Arch Ophthalmol. 2001;119:215–222. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Krebs I, Brannath W, Glittenberg K, Zeiler F, Sebag J, Binder S. Posterior vitreo-macular adhesion: a potential risk factor for exudative age-related macular degeneration. Am J Ophthalmol. 2007;144:741–746. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2007.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schulze S, Hoerle S, Mennel S, Kroll P. Vitreomacular traction and exudative age-related macular degeneration. Acta Ophthalmol. 2008;86:470–481. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-3768.2008.01210.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee SJ, Lee CS, Koh HJ. Posterior vitreomacular adhesion and risk of exudative age-related macular degeneration: paired eye study. Am J Ophthalmol. 2009;147:621–626. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2008.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Robison CD, Krebs I, Binder S, et al. Vitreomacular adhesion in active and end-stage age-related macular degeneration. Am J Ophthalmol. 2009;148:79–82. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2009.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]