Abstract

Atherosclerosis is characterized by formation and development of the plaques in the inner layer of the vessel wall. To detect and characterize atherosclerotic plaques, we previously introduced the combined intravascular ultrasound (IVUS) and intravascular photoacoustic (IVPA) imaging capable of assessing plaque morphology and composition. The utility of IVUS∕IVPA imaging has been demonstrated by imaging tissue-mimicking phantoms and ex vivo arterial samples using laboratory prototype of the imaging system. However, the clinical realization of a IVUS∕IVPA imaging requires an integrated intravascular imaging catheter. In this paper, two designs of IVUS∕IVPA imaging catheters—side fire fiber-based and mirror-based catheters—are reported. A commercially available IVUS imaging catheter was utilized for both pulse-echo ultrasound imaging and detection of photoacoustic transients. Laser pulses were delivered by custom-designed fiber-based optical systems. The optical fiber and IVUS imaging catheter were combined into a single device. Both designs were tested and compared using point targets and tissue-mimicking phantoms. The results indicate applicability of the proposed catheters for clinical use.

INTRODUCTION

Cardiovascular disease represents a significant clinical problem—more than one million people die annually due to problems with arteries.1, 2, 3 The most common reason of the mortality is atherosclerosis characterized by formation and development of atherosclerotic plaques inside the arterial walls. The vulnerability of different types of the atherosclerotic plaques depends on their composition.4, 5, 6 Therefore, successful and even patient-tailored treatment of the disease can be achieved if the distribution and the vulnerability of the plaques are diagnosed reliably.

A number of imaging techniques can be applied for diagnosis of the atheroslcerosis.7 For example, the ultrasound-based technique—intravascular ultrasound (IVUS) imaging—can be used to image the atherosclerotic plaques in arteries.8, 9, 10 This minimally invasive catheter-based approach is suitable to detect unrecognized disease, lesions of uncertain severity (40%–75% stenosis), and risk of stratification of atherosclerotic lesions in interventional practice.10, 11, 12 The two clinically approved IVUS imaging systems are based on catheter with either mechanically scanned single-element transducer operating at up to 40 MHz or electronically scanned 64 element array transducer operating in the 20 MHz range.13, 14 However, because of low ultrasound imaging contrast between various types of plaques, the plaques cannot be characterized reliably based on information obtained from the IVUS images only. To further assess the vulnerability of the plaques, we previously introduced intravascular photoacoustic (IVPA) imaging.15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21

Photoacoustic imaging utilizes light absorption properties of tissues. After excitation of the tissues by short laser pulses, consequent acoustic transients generated as a result of thermal expansion are detected.22, 23, 24 A number of scientific groups successfully use the photoacoustic technique for vascular applications.25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30 Previously, we investigated the feasibility of IVPA imaging using commercially available IVUS imaging catheters.15 The excised tissue samples were imaged with the IVUS catheter located inside of a lumen, while the vessel was externally irradiated, and the capability of the combined IVUS∕IVPA imaging to detect and differentiate atherosclerotic plaques was demonstrated.17, 18 However, for clinical use, an artery with atherosclerotic plaques must be irradiated internally. Therefore, a specially designed integrated IVUS∕IVPA imaging catheter is needed. Optical fiber-based probes, potentially suitable for IVPA and IVUS imaging have already been reported.31, 32 However, a catheter for combined IVUS∕IVPA imaging27 has not been realized yet.

In the current paper, we report two designs of optical fiber-based catheters for combined IVUS∕IVPA imaging. Both prototypes are based on a single-element ultrasound transducer coupled with originally designed light delivery systems. One approach uses the side fire fiber, similar to probes utilized for biomedical optical spectroscopy.33 The second design of the catheter uses the micro-optics as often implemented in optical coherent tomography.34 Both designs were tested in phantom studies using point targets either alone or embedded into tissue-mimicking background. The performance of the IVUS∕IVPA imaging catheters was compared and discussed.

DESIGN OF IVUS∕IVPA CATHETERS

A commercially available IVUS imaging catheter (Atlantis™, SR plus, Boston Scientific, Inc.)13 based on a single-element ultrasound transducer operating at central frequency of 40 MHz with fractional bandwidth of about 40% was used. The IVUS imaging catheter was coupled with a custom-built light delivery system based on a single multimode optical fiber with the numerical aperture (NA) of 0.37 and refractive indices of 1.457 and 1.404 for core and cladding, respectively. The laser damage threshold of the silica core material is 1 GW∕cm2 for 5 ns pulses. The proximal end of the optical fiber, polished flat and perpendicular to the optical axis of the fiber, was coupled with a pulsed laser source. At the distal end of the fiber, the light delivery system was designed using either side fire fiber-based approach or approach based on micro-optics assembly mounted at the distal ends of the fibers. In both approaches, the transversal cross-section of the arterial wall was imaged.

Side fire fiber-based IVUS∕IVPA catheter

The operation of side fire fiber, shown schematically in Fig. 1a, is based on the total internal reflection (TIR) effect. The critical angle γ of TIR is defined as

| (1) |

where nmed and ncore are refractive indices of medium outside of a fiber and of a fiber core. If β is a polishing angle of fiber, then the TIR effect appears when

| (2) |

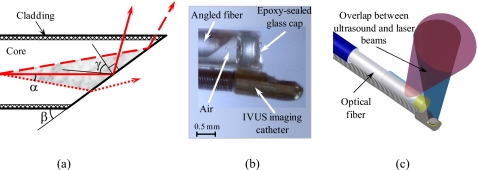

Figure 1.

(a) Schematic diagram of the light distribution near the distal end of the fiber. The light can propagate along the fiber’s axis within the cone (shown in gray). The light rays fully satisfying the TIR condition will be reflected from the polished surface (solid beam and dashed beam). However, under the same conditions, some light rays may not satisfy the TIR effect (dotted beam). See text for details. (b) A photograph of the distal end of the combined IVUS∕IVPA side fire fiber-based imaging catheter that utilizes the TIR effect, and (c) a diagram of the combined IVUS∕IVPA imaging catheter showing an alignment between ultrasound and light beams.

The light beam, schematically shown in Fig. 1a using a solid line, propagates along the fiber optical axis and satisfies condition 2. However, due to nonzero NA of the fiber, only a portion of the light could be redirected by the TIR effect. Light inside of the fiber can propagate within the certain cone [shown in gray between dashed and dotted lines in Fig. 1a] with a full cone angle 2α of fiber defined as

| (3) |

where ncl is a refractive index of fiber cladding. Obviously, if condition 2 is valid for the beam outlined by the solid line, it will also be valid for the beam shown in Fig. 1a by the dashed line because the beam approaches to the surface at an angle smaller than β. On the contrary, for the light beam shown in Fig. 1a by the dotted line, condition 2 is not valid—the angle between the beam and the surface is greater than β. Therefore, condition 2 should be rewritten to account for the NA of the fiber. Taking Eqs. 1, 2, 3 into account, the TIR effect appears when the polishing angle β1 is

| (4) |

The TIR effect increases for smaller angle and reaches 100% when polishing angle β2 is

| (5) |

For the fibers utilized in our experiment (FT600EMT, Thorlabs, Inc., 600 μm core diameter), angles β1 and β2 in water were 39.68° and 8.46°, respectively. If the polishing angle β is smaller than angle β2, then the TIR effect will redirect light completely at the maximum angle of 16.92°. In the case of β2<β<β1, the only limited fraction of the light decreased with angle β will be redirected by the TIR effect at the angle in the range of 16.92°–79.36°. The rest light will be normally refracted and not utilized for IVPA imaging. Further increase in angle β will only result in the refraction of light. Since the irradiation of an artery at a near 90° angle (i.e., orthogonal to the longitudinal axes of the imaging catheter, optical fiber, and artery) is required in IVPA imaging, the values of both angles β1 and β2 could be increased by replacing water by air—the value of last term in Eqs. 4, 5 becomes smaller. If the air is kept near the distal end of the fiber, the values of β1 and β2 angles will comprise 62.25° and 31.03°, respectively. Therefore, light will be completely redirected by the TIR effect in the range of 0°–62.06°. Further elevation of angle β will result in incomplete light redirection by the TIR effect in the range of 62.06°–124.5°.

The photograph and the diagram of a side fire fiber-based IVUS∕IVPA imaging catheter are shown in Figs. 1b, 1c, respectively. The distal end of the optical fiber was polished at the angle β of 33°, and a cap was used to keep air near the tip. The cap was made out of a quartz pipe with an inner diameter of 700 μm and an outer diameter of 1 mm. The air cap was sealed with an approximately 500-μm-thick layer of epoxy (Devcon, Inc.). The IVUS imaging transducer was fixed on the fiber such that ultrasound and light beams were aligned and overlapped. The light divergence after the catheter was measured to be 26°, while angle between the light and ultrasound beams was 24°.

Mirror-based IVUS∕IVPA catheter

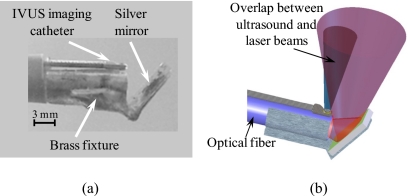

In the second design, the distal end of the optical fiber was polished flat and perpendicular to the optical axis of the fiber, and a mirror was used to redirect the light. The photograph and the diagram of mirror-based IVUS∕IVPA imaging catheter are shown in Figs. 2a, 2b, respectively. A mirror with a laser damage threshold of 170 mJ∕cm2 for 5 ns pulses was fabricated by thermal evaporation of silver powder (part #303372–10G, Sigma-Aldrich, Inc.) on 1-mm-thick glass. The mirror was attached to the fiber using a custom-made brass fixture. The angle between optical fiber’s axis and the mirror was chosen to be 52° for better overlap between light and ultrasound beams. The IVUS imaging transducer was fixed facing away from fiber in the position resulting in the maximum overlap of the ultrasound and light beams and also avoiding a direct interaction of light with the ultrasound transducer. Since reflection of the light from a mirror does not rely on indices of refractive of fiber’s core and the surrounding medium, there is no need to keep air near distal end of the light delivery system as in the first design. However, the light divergence of this imaging catheter depends on both the fiber’s NA and the relationship between refractive coefficients of fiber’s core and the medium. If an optical fiber is short, the light distribution after the fiber depends also on the laser-fiber coupling—in our experiments with 1500 μm core diameter fiber (FT1500EMT, Thorlabs, Inc.), the light divergence from the imaging catheter in water comprised 17°.

Figure 2.

(a) Photograph of distal end of the combined IVUS∕IVPA mirror-based imaging catheter, and (b) a diagram of the combined IVUS∕IVPA imaging catheter showing an alignment of the ultrasound and light beams.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Phantoms

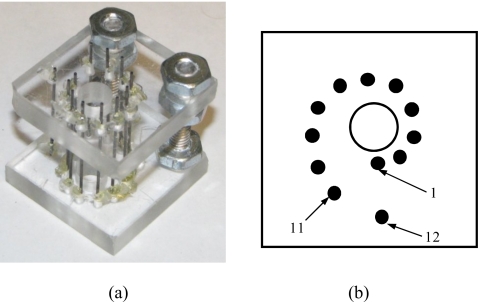

A photograph and a diagram of a point-target phantom are shown in Figs. 3a, 3b, respectively. Graphite rods with a 0.6 mm diameter, oriented perpendicularly to an imaging plane, were used as point sources of photoacoustic waves since graphite is a strong optical absorber. Eleven of the graphite rods were located 4–9 mm away from the center of the phantom with the 0.5 mm increment. In addition, a 12th rod was positioned 10 mm away from the center of the phantom and behind first rod.

Figure 3.

(a) Photograph and (b) a diagram of phantom with point targets used to evaluate the performance of IVUS∕IVPA imaging catheters.

To mimic tissue environment, the point-target phantom was submersed into 10% gelatin (Type A, Sigma-Aldrich, Inc.), while leaving the center portion of the phantom open to represent lumen. Silica particles (Sigma-Aldrich, Inc.) with 0.5% weight concentration and an average size of 40 μm were added to gelatin solution to act as ultrasound scatterers.35 Optical scattering was mimicked by adding 20% of low-fat milk (volume concentration).36 The overall size of the phantom’s body was measured to be 40×35×30 mm while the lumen diameter was equal to 6 mm.

IVUS∕IVPA imaging system

The imaging system consisted of a pulsed laser, an ultrasound pulser-receiver and a computer data acquisition system. An OPO laser (Vibrant II, Opotek, Inc.) with a pulse duration of 5 ns and a repetition rate of 10 Hz was operated at 730 nm. A lens with the diameter of 25 mm and focal distance of 100 mm was used to couple the OPO with combined IVUS∕IVPA imaging catheters. The proximal end of the optical fiber was located several millimeters after the focal zone of the lens so that the aperture of the fiber was completely filled with light. To image point targets alone or within the tissue-mimicking environment, the energy of the laser was adjusted so that the laser energies measured at the distal end of the fiber were 1.4 and 2.4 mJ, respectively.

The ultrasound transducer, used in both photoacoustic (receiver only) and ultrasound (transmitter and receiver) modes, was operated by the ultrasound pulser∕receiver (5073PR, Panametrics-NDT, Inc.). Each radiofrequency (rf) signal consisted of photoacoustic transient, followed by ultrasound pulse-echo signal delayed by 10 μs relative to photoacoustic signal. At each position, ten rf signals were captured using a data acquisition card (CompuScope 12200, GageScope, Inc.), and then averaged and further processed off-line.

During imaging experiments, the phantom was placed in a water tank attached to a rotation stage operated by a stepper motor (ACCU Coder, Encoder Products, Inc.). The combined IVUS∕IVPA imaging catheter was positioned within a phantom such that the IVUS imaging transducer was located approximately on the axis of rotation. One revolution (360° rotation) of the phantom included 251 steps. Therefore, each image consisted of 251 beams. For each beam, the averaged rf signal was demodulated, normalized for the laser energy and scan converted to cover the 11 mm radius field of view. No angle correction or compensation for laser fluence variations was applied.

RESULTS

Side fire fiber-based IVUS∕IVPA probe

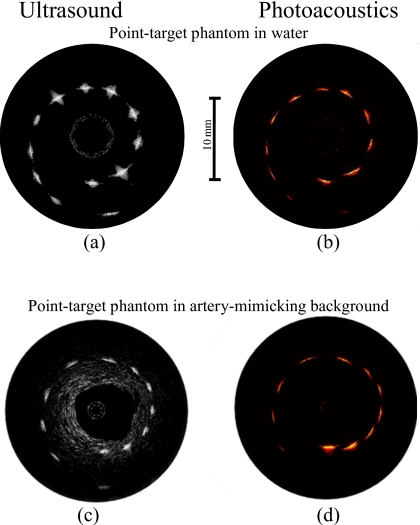

The ultrasound and photoacoustic images of the point-target phantom obtained by the side fire fiber-based catheter are displayed in Figs. 4a, 4b. All ultrasound and photoacoustic images are shown using the display dynamic range of 29 and 25 dB, respectively. The ultrasound B-scan in Fig. 4a shows the structure of the phantom where all 12 point targets are visible. The brightness of the targets slightly decreases with the depth due to attenuation of the high-frequency (40 MHz) ultrasound in water and a divergence of the ultrasound beam.

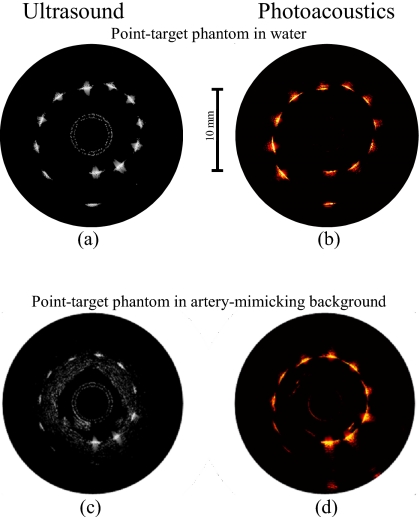

Figure 4.

[(a) and (c)] Ultrasound and [(b) and (d)] photoacoustic images of the phantom obtained using the side fire fiber-based combined IVUS∕IVPA imaging catheter.

The photoacoustic image in Fig. 4b demonstrates a decrease in the photoacoustic signal strength with the depth due to the light distribution in the phantom. Indeed, the light divergence increases the area of illumination with the distance from the catheter and, therefore, decreases the fraction of the light absorbed by the targets located further away from the catheter.

The ultrasound and photoacoustic B-scans of the point-target phantom within the tissue-mimicking environment are shown in Figs. 4c, 4d. The ultrasound image in Fig. 4c identifies the structure of the phantom. However, the decrease in the brightness of the targets with depth is greater than in Fig. 4a because ultrasound attenuation in tissue-mimicking environment is greater than that in water. This environment is not noticeable in the photoacoustic image in Fig. 4d due to modest light absorption in the gelatin and silica particles at 730 nm. However, the decrease in the photoacoustic transient magnitude from the targets in tissue-mimicking environment with depth is greater than in water [Fig. 4b] due to light scattering in the surrounding material. The light energy decays exponentially with distance, therefore causing the target that is further away from the catheter to become invisible due to limited light energy reaching the target. Also, the generated photoacoustic wave attenuates as it travels to the transducer.

Mirror-based IVUS∕IVPA probe

The ultrasound and photoacoustic B-scans of the point-target phantom obtained using the mirror-based catheter are shown in Figs. 5a, 5b. All 12 targets are clearly visible in Fig. 5a. Brightness of targets decreases slightly with depth.

Figure 5.

[(a) and (c)] Ultrasound and [(b) and (d)] photoacoustic images of the phantom obtained using the mirror-based combined IVUS∕IVPA imaging catheter.

The photoacoustic image in Fig. 5b indicates that the brightness of point targets increases slightly for first seven targets (see Fig. 3) because the closer absorbers are not illuminated well, while the 8th through 11th targets were irradiated almost uniformly. Finally, the brightness of the 12th target is modest because this target is located too far from the catheter where there is a limited overlap between ultrasound and light beams.

The ultrasound and photoacoustic images of the point targets in the tissue-mimicking environment are shown in Figs. 5c, 5d. Similar to Fig. 5a, all targets are detected in Fig. 5c and, as expected, the brightness of targets decreases with a distance from the transducer.

The photoacoustic image in Fig. 5d indicates that targets located closer to the catheter generate greater photoacoustic transients—this is due to strong light scattering in the background. Indeed, the directivity of the laser beam is affected by light scattering and the optical fluence and, therefore, the absorbed light energy rapidly decreases with depth.

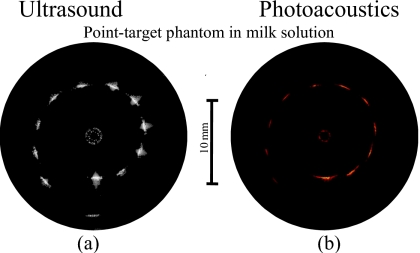

Under clinical condition, light scattering in blood adds to that in soft tissues in the near-infrared spectral region.37 To initiate a light scattering in a lumen, 20% solution of low-fat milk was used.38, 39 The ultrasound and photoacoustic images of the phantom obtained by side fire fiber-based imaging catheter are shown in Figs. 6a, 6b, respectively. As expected, the ultrasound image in Fig. 6a shows all 12 point targets. The brightness of the targets decreases with depth at almost the same rate as in the ultrasound image of the phantom in water [Fig. 4a]. However, the light scattering results in a significant exponential attenuation of light in the milk solution so that the brightness of point targets shown in photoacoustic image in Fig. 6b decreases rapidly with depth. Nevertheless, the photoacoustic transients generated by first six targets are clearly detectable. These targets are located 4–6.5 mm away from the imaging catheter suggesting that photoacoustic imaging of the artery’s walls in the presence of blood is possible. In addition, the brightness of the targets can be increased by increasing the light energy.

Figure 6.

(a) Ultrasound and (b) photoacoustic images of the phantom in scattering medium obtained using the side fire fiber-based combined IVUS∕IVPA catheter.

DISCUSSION

Comparison of the performance of two catheter designs

Both designs of catheters are appropriate for combined IVUS∕IVPA imaging. Using the IVUS∕IVPA imaging catheters, ultrasound images of the phantom with point targets within water [Figs. 4a, 5a] and artery-mimicking environments [Figs. 4c, 5c] clearly show the presence and location of the targets. The insignificant differences between the images are related to the variations in the imaged cross-sections and properties of the IVUS imaging catheters utilized in the experiments.

The comparison of the photoacoustic images of the phantom obtained using side fire fiber-based and mirror-based imaging catheters [Figs. 4b, 5b, respectively] indicates the importance of several factors. For best overlap between ultrasound and light beams, the distal end of light delivery system should be as close to the ultrasound transducer as possible. In addition, the angle between ultrasound and laser beams should be as small as possible. These factors are better realized in the side fire fiber-based catheter. Indeed, for the mirror-based imaging catheter, the brightness of the point targets in the photoacoustic image in Fig. 5b varies because the closer targets are not illuminated well due to a large offset between the mirror and the transducer and, therefore, reduced overlap of the laser beam and ultrasound beam. The smaller light divergence of the mirror-based light delivery system also affects the irradiation of the targets. The light divergences at the distal end of side fire fiber-based and of mirror-based imaging catheters are measured to be 26° and 17°, respectively. Therefore, the area of significant overlap between the ultrasound and laser beams is located further from the ultrasound transducer for the mirror-based imaging catheter.

Comparing with the ultrasound beam divergence, calculated to be approximately 5°, light divergence is significantly greater. In both designs of the imaging catheters, the divergence of light at the distal end of the catheter can be reduced using an air cap or a mirror with specially designed shape. However, as shown in Fig. 6b, the light scattering in both blood and arterial wall37 will result in effective light redistribution. Therefore, the resolution of the combined IVUS∕IVPA imaging catheter is defined primarily by the ultrasound transducer rather than by light delivery system.

The resolution of the photoacoustic images could be improved by advanced signal and image processing algorithms. All reported images were formed without any sophisticated reconstruction techniques. However, beam-forming procedures may be applied to improve the photoacoustic images—such approaches are often implemented to reconstruct images obtained using ultrasound array-based systems.40 Overall, the sophisticated image-formation algorithms could remove artifacts and improve contrast and spatial resolution. For example, lateral spread of point sources of photoacoustic images in Figs. 4b, 5b, 6b could be reduced.41

Maximum energy estimation

In the experiments, the laser pulses with the energy less than 2.5 mJ were reasonable for IVPA imaging of phantoms placed in water. In the near-infrared spectral region, the blood is characterized by an absorption coefficient from 1.5 to 6.5 cm−1 for oxygenated blood and from 12.9 to 1.1 cm−1 for deoxygenated blood.42 Therefore, the blood will attenuate the light, reduce the optical fluence, and decrease the strength of the photoacoustic signal from deeper regions. Consequently, to achieve reasonable image quality (i.e., signal-to-noise ratio), a higher energy of laser irradiation may be needed. In addition, the low light absorption of soft tissues37 and limited optical contrast between healthy tissues and plaques might further require an increased energy of laser pulses.

The laser damage threshold for most commonly used optical fibers is reported to be 1 GW∕cm2 for 5 ns pulses; thus the delivered light energy is limited by a size of the fiber. However, the fiber should be relatively thin and flexible to fit into lumen and to reach the desired location within the vessel. Since the diameter of an ultrasound transducer is about 500 μm, the 600 μm core diameter of the optical fiber, capable of delivering 14 mJ laser pulses, appears to be a reasonable choice for combined IVUS∕IVPA imaging catheters.

The side fire fiber-based catheter does not utilize any mirrors and its laser damage threshold is limited by the optical fiber itself because the laser damage threshold of quartz glass is over 30 GW∕cm2. For a given NA and refractive indices, the entire energy of laser pulses will be redirected by the angled tip if the angle of polishing β≤β2 and the light losses increase from 0% through 100% with the β if β2<β<β1 due to TIR conditions [Eqs. 4, 5].

After the redirection, light propagates through cladding, air gap and quartz pipe. Assuming the blood refractive index to be 1.33 and β≤β2, the energy of the laser pulse will be reduced by about 6.6%. Therefore, the maximum energy of laser pulses at the distal end can be about 13 mJ. This value, however, could increase slightly if an antireflecting coating on inner side of the cap and outer side of fiber’s cladding will be used.

In the mirror-based catheter, the upper limit of the laser pulse energy is determined by the laser damage threshold of the mirror. Specifically, the fiber with a diameter of 1500 μm was utilized in our experiments to decrease the laser fluence on our custom-made mirror—maximum of 3 mJ per pulse can be delivered using our custom-made mirror. The laser damage threshold of commercially available wideband mirrors is up to 1 J∕cm2 for 10 ns pulses. If coupled with such a mirror, a 600 μm fiber will support delivery of up to 2.8 mJ of light. Furthermore, special mirrors with laser damage threshold up to 27 J∕cm2 can be made. With such mirrors the imaging catheter will be capable of delivering 14 mJ laser pulses. However, less than 2% of the light energy will be lost in a cap or sheath covering the rotating components of the imaging catheter. Such protection is required for several reasons including the necessity of making the catheter tip round, shielding the mirror from blood, and insuring no mechanical damage of the vessel wall due to catheter rotation.

In vivo imaging

Due to the low repetition rate of the laser utilized in our ex vivo imaging experiments, the acquisition time of the combined IVUS∕IVPA image exceeded 25 s. For in vivo imaging, therefore, faster pulse repetition rate lasers maybe needed. Diode-pumped solid state (DPSS) lasers characterized by several tens of millijoule energy per pulse and capable of operating at several kilohertz pulse repetition rate can be used. Such DPSS lasers, combined with tunable dye lasers, are capable of generating light in near-infrared spectral range with average energy per pulse of several millijoules. Therefore, DPSS and other fast pulse repetition rate lasers will allow real time (i.e., 30 frames per second) photoacoustic imaging.

An ultrasound array-based IVUS imaging catheter can also be used instead of the single-element-based catheter. Such an array-based catheter coupled with an appropriate light delivery system will not require rotation and, generally, will be capable of photoacoustic imaging of the full arterial cross-section using a single laser pulse. In addition, the quality of photoacoustic images can be increased using sophisticated beamforming40 and image-formation techniques.41

The light delivery system can be based either on a single fiber or on an optical bundle. In a single-fiber approach, the fiber with direction laser beam has to be rotated, as it was done in our studies, or a stationary fiber with an axiconlike43, 44 distal tip can be used. Given the same pulse energy, the rotating fiber approach will limit the frame repetition rate of the IVPA imaging but the contrast and signal-to-noise ratio of IVPA images will be greater due to higher fluence of light. On the contrary, the axiconlike polished fiber will provide an even irradiation of the imaged cross-section of the artery thus making possible an increase in the frame repetition rate at the expense of a decrease in fluence. The optical fiber bundle-based light delivery system combines the advantages of rotating fiber and axiconlike polished fiber. Indeed, each fiber in the bundle can irradiate a limited part of the imaged cross-section with high fluence but all fibers in the bundle together can provide an even irradiation of the artery. However, the optical bundle is thicker than a single fiber and, therefore, the flexibility of such combined IVUS∕IVPA imaging catheter may be compromised. Overall, there are various tradeoffs between different designs of light delivery systems.

The presence of luminal blood will result in the generation of the strong photoacoustic signal registered in the IVPA images. However, IVUS images can identify the geometry of the lumen and, given the specific time-of-flight, the distinct photoacoustic signal from blood45 can be identified and filtered out. Therefore, it is anticipated that the presence of blood will only minimally disturb the IVPA images.

The maximum laser fluence is limited by laser safety standards for biological applications. Furthermore, thermal safety of IVPA imaging should be established. During ex vivo experiments, the temperature increase in arterial tissues directly irradiated by laser pulse with fluence of 60 mJ∕cm2 did not exceed 1.1 °C, and the analysis based on the Arrhenius thermal damage model suggested no thermal injury in the arterial tissue.16 In in vivo IVPA imaging using combined imaging catheter, blood will be the first tissue irradiated by laser pulse. Therefore, overall safety of the IVPA imaging needs to be further studied considering realistic in vivo environment.

CONCLUSIONS

Two designs of the IVUS∕IVPA imaging catheters for combined ultrasound and photoacoustic imaging have been introduced. Both designs were tested and compared using point-target phantom and tissue-mimicking phantom. A side fire fiber-based system is capable of delivering laser pulses with higher energy but limited by the laser damage threshold of the fiber. The laser energy in the mirror-based system is limited by the laser damage threshold of mirror. The laser energy losses are low for both types of integrated IVUS∕IVPA imaging catheters. Both designs may be utilized for combined IVUS∕IVPA imaging of vessel wall and atherosclerotic plaques.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Support in part by National Institutes of Health under Grant Nos. HL 096981 and HL 084076 is acknowledged. The authors want also to thank Michael R. Markham, Ph.D., School of Biological Sciences at University of Texas at Austin for providing quartz pipes used in the side fire fiber-based IVUS∕IVPA imaging catheter. Helpful discussions with Mr. Jimmy Su and Mr. Douglas Yeager of the University of Texas at Austin are also acknowledged.

References

- Falk E., Shah P. K., and Fuster V., Circulation 92, 657 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kronzon I. and Tunick P. A., Circulation 114, 63 (2006). 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.593418 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madjid M., Zarrabi A., Litovsky S., Willerson J. T., and Casscells W., Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 24, 1775 (2004). 10.1161/01.ATV.0000142373.72662.20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naghavi M., Libby P., Falk E., Casscells S. W., Litovsky S., Rumberger J., Badimon J. J., Stefanadis C., Moreno P., Pasterkamp G., Fayad Z., Stone P. H., Waxman S., Raggi P., Madjid M., Zarrabi A., Burke A., Yuan C., Fitzgerald P. J., Siscovick D. S., de Korte C. L., Aikawa M., Airaksinen K. E. J., Assmann G., Becker C. R., Chesebro J. H., Farb A., Galis Z. S., Jackson C., Jang I. -K., Koenig W., Lodder R. A., March K., Demirovic J., Navab M., Priori S. G., Rekhter M. D., Bahr R., Grundy S. M., Mehran R., Colombo A., Boerwinkle E., Ballantyne C., W.Insull, Jr., Schwartz R. S., Vogel R., Serruys P. W., Hansson G. K., Faxon D. P., Kaul S., Drexler H., Greenland P., Muller J. E., Virmani R., Ridker P. M., Zipes D. P., Shah P. K., and Willerson J. T., Circulation 108, 1664 (2003). 10.1161/01.CIR.0000087480.94275.97 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stary H. C., Chandler A. B., and Dinsmore R. E., Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 15, 1512 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Virmani R., Kolodgie F. D., Burke A. P., Farb A., and Schwartz S. M., Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 20, 1262 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fayad Z. A. and Fuster V., Circ. Res. 89, 305 (2001). 10.1161/hh1601.095596 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Korte C. L., Sierevogel M. J., Mastik F., Strijder C., Schaar J. A., Velema E., Pasterkamp G., Serruys P. W., and van der Steen A. F. W., Circulation 105, 1627 (2002). 10.1161/01.CIR.0000014988.66572.2E [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nissen S. E. and Yock P., Circulation 103, 604 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishioka T., Luo H., Eigler N. L., Tabak S. W., and Seigel R. J., in Intravascular Ultrasound Imaging in Coronary Artery Disease, Seigel R. J., Marcel Dekker, New York: (1998), pp. 75–95. [Google Scholar]

- Fitzgerald P. J. and Yock P. G., J. Clin. Ultrasound 21, 579 (1993). 10.1002/jcu.1870210905 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoenhagen P. and Nissen S. E., Heart 88, 91 (2002). 10.1136/heart.88.1.91 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boston Scientific Inc., Atlantis RS Pro imaging catheter. See http://www.bostonscientific.com.

- Volcano Corporation, Visions® PV8.2F imaging catheter. See http://www.volcanocorp.com.

- Sethuraman S., Aglyamov S. R., Amirian J. H., Smalling R., and Emelianov S. Y., IEEE Trans. Ultrason. Ferroelectr. Freq. Control 54, 978 (2007). 10.1109/TUFFC.2007.343 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sethuraman S., Aglyamov S. R., Smalling R., and Emelianov S. Y., Ultrasound Med. Biol. 34, 299 (2008). 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2007.07.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sethuraman S., Amirian J. H., Litovsky S. H., Smalling R., and Emelianov S. Y., Opt. Express 15, 16657 (2007). 10.1364/OE.15.016657 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sethuraman S., Amirian J. H., Litovsky S. H., Smalling R., and Emelianov S. Y., Opt. Express 16, 3362 (2008). 10.1364/OE.16.003362 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang B., Yantsen E., Larson T., Sethuraman S., Sokolov K., and Emelianov S. Y., Proc.-IEEE Ultrason. Symp. , 848 (2007). 10.1109/ULTSYM.2007.217 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang B., Yantsen E., Sokolov K., and Emelianov S. Y., Proceedings of the 2009 SPIE Photonics West Symposium: Photons Plus Ultrasound: Imaging and Sensing, 2009. (unpublished), Vol. 7177, pp. 1–6.

- Wang B., Yantsen E., Larson T., Karpiouk A. B., Sethuraman S., Su J. L., Sokolov K., and Emelianov S. Y., Nano Lett. 9, 2212 (2009). 10.1021/nl801852e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gusev V. E. and Karabutov A. A., Laser Optoacoustics (American Institute of Physics, New York, 1993). [Google Scholar]

- Patel C. K. N. and Tam A. C., Rev. Mod. Phys. 53, 517 (1981). 10.1103/RevModPhys.53.517 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tam A. C., Rev. Mod. Phys. 58, 381 (1986). 10.1103/RevModPhys.58.381 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Beard P. C. and Mills T. N., Phys. Med. Biol. 42, 177 (1997). 10.1088/0031-9155/42/1/012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berlis A., Lutsep H., Barnwell S., Norbash A., Wechsler L., Jungreis C. A., Woolfenden A., Redekop G., Hartmann M., and Schumacher M., Stroke 35, 1112 (2004). 10.1161/01.STR.0000124126.17508.d3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henrichs P. M., Meador J. W., Fuqua J. M., and Oraevsky A. A., Proc. SPIE 5697, 217 (2005). 10.1117/12.591593 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Petrov Y. Y., Petrova I. Y., Patrikeev I. A., Esenaliev R. O., and Prough D. S., Opt. Lett. 31, 1827 (2006). 10.1364/OL.31.001827 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pilatou M. C., Voogd N. J., de Mul F. F. M., Steenbergena W., and van Adrichem L. N. A., Rev. Sci. Instrum. 74, 4495 (2003). 10.1063/1.1605491 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H. F., Maslov K., Sivaramakrishnan M., Stoica G., and Wang L. V., Appl. Phys. Lett. 90, 053901 (2007). 10.1063/1.2435697 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Beard P. C., Perennes F., Draguioti E., and Mills T. N., Opt. Lett. 23, 1235 (1998). 10.1364/OL.23.001235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fomitchov P. A., Kromine A. K., and Krishnaswamy S., Appl. Opt. 41, 4451 (2002). 10.1364/AO.41.004451 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Utzinger U. and Richards-Kortum R., J. Biomed. Opt. 8, 121 (2003). 10.1117/1.1528207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujimoto J. G., Boppart S. A., Tearney G. J., Bouma B. E., Pitris C., and Brezinski M. E., Heart 82, 128 (1999). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madsen E. L., Zagrebski J. A., MacDonald M. C., and Frank G. R., Med. Phys. 18, 1171 (1991). 10.1118/1.596589 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Z. and Myllylli R., Meas. Sci. Technol. 12, 2172 (2001). 10.1088/0957-0233/12/12/319 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cheong W. -F., Prahl S. A., and Welch A. J., IEEE J. Quantum Electron. 26, 2166 (1990). 10.1109/3.64354 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mitic G., Kolzel J., Otto J., Plies E., Solkner G., and Zinth W., Appl. Opt. 33, 6699 (1994). 10.1364/AO.33.006699 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pogue B. W. and Patterson M. S., J. Biomed. Opt. 11, 041102 (2006). 10.1117/1.2335429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park S., Karpiouk A. B., Aglyamov S. R., and Emelianov S. Y., Opt. Lett. 33, 1291 (2008). 10.1364/OL.33.001291 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S., Aglyamov S. R., and Emelianov S. Y., Proceedings of the 31st Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society, 2009. (unpublished), pp. 475–478.

- Prahl S., “Tabulated molar extinction coefficient for hemoglobin in water,” Oregon Medical Laser Center, 1999. See http://omlc.ogi.edu/spectra/hemoglobin/summary.html.

- Eah S. -K. and Jhe W., Rev. Sci. Instrum. 74, 4969 (2003). 10.1063/1.1623002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer D. J., Harkrider C. J., and Moore D. T., Appl. Opt. 39, 2687 (2000). 10.1364/AO.39.002687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karpiouk A. B., Aglyamov S. R., Mallidi S., Shah J., Scott W. G., Rubin J., and Emelianov S. Y., J. Biomed. Opt. 13, 054061 (2008). 10.1117/1.2992175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]