Abstract

A growing literature on adolescent drug treatment interventions demonstrates the efficacy of “research therapies,” but few rigorous studies examine the effectiveness of community-based treatments that are more commonly available to and utilized by youths and their families, the criminal justice system and other referring agencies. Even less is known about the long term effects of these community based treatments. This study evaluates the effects 72 to 102 months after intake to a widely disseminated community based treatment model, residential therapeutic community treatment, using data from RAND's Adolescent Outcomes Project. Weighting is used to control for pre-existing differences between adolescent probationers disposed to Phoenix Academy and those assigned to one of six alternative group homes serving as the comparison conditions. Although Phoenix Academy therapeutic community treatment had positive effects on substance use and psychological functioning during the first 12 months following intake, we find no evidence of positive long term effects on 16 outcomes measuring substance use and problems, criminal activity, institutionalization, psychological functioning and general functioning; but there is a significant negative effect for property crimes. We discuss the implications of these findings and the failure to maintain the effects observed in during the first year follow-up.

Keywords: Substance abuse treatment, adolescents, long-term outcomes, adjudicated youth

1. Introduction

A growing literature on adolescent drug treatment interventions demonstrates the efficacy of what Weisz et al. (1992) refer to as “research therapies.” (e.g., family therapy, cognitive therapy, behavior therapy and other specialized interventions; Liddle et al., 2008; Liddle et al., 2009; Waldron and Kaminer, 2004; Waldron and Turner, 2008; Williams et al. 2000; Winters, 1999). In contrast, few rigorous studies examine the effectiveness of community-based treatments that are more commonly available to and utilized by youths and their families, the criminal justice system and other referring agencies (Morral et al., 2004). In 2006, over 135,000 youth aged 12–17 were admitted to publicly-funded substance abuse treatment programs, and over half of them were referred by the criminal justice system (SAMSHA, 2008). Given the large number of referrals to community-based treatments, it is important to gain a better understanding of their effectiveness.

Many of the available studies of community-based treatment programs derive from large observational studies in which drug use and other problem behaviors in the period immediately preceding treatment entry are compared with those behaviors some time after treatment (e.g., Breda and Heflinger, 2007; Ciesla et al., 2008; Hall et al., 2008; Hser et al., 2001; Kim and Jackson, 2009; Rivaux et al., 2006; Shane et al., 2006; Subramaniam et al., 2007). In these studies, however, the observed improvement cannot persuasively be attributed to treatment effects, since there is no adequate control group for comparison.

Few studies of adolescent treatment in the community have used evaluation designs sufficiently rigorous to control for pretreatment differences in risk factors observed in treated and comparison youths (Catalano et al., 1991; Williams et al., 2000). Exceptions include the work of Winters, Latimer, and colleagues and our own Adolescent Outcomes Project, which is the data source for the analyses reported in this article. In both cases, quasi-experimental designs using carefully matched comparison conditions demonstrated that the observed adolescent treatment services improved later drug use and other outcomes relative to comparison conditions. Winters et al. (2000) reported superior drug use outcomes 12-months after youths received “Minnesota model” inpatient or outpatient care in comparison to matched youths in a waiting list condition. Similarly, we found that youths admitted from juvenile hall to a residential therapeutic community treatment had superior drug use and psychological functioning outcomes 12-months later in comparison to a matched group of youths who were referred to non-specialized residential group homes (Morral et al., 2004).

These more rigorous examinations of treatment effects are encouraging. However, it is important to know whether treatment effects last beyond one year post referral. In theory, an intervention that successfully reduces drug use and psychological distress up to 12 months after program admission could set youths on a life course that progressively diverges from their earlier trajectories for many years beyond the point at which many are leaving probation supervision. If so, this could greatly increase the cost-benefits of substance abuse treatment for adolescent probationers.

Although several studies have described the long-term course of post-treatment functioning for adolescents receiving substance abuse treatment (e.g., Brown, et al., 2001; Doyle et al., 1994; Kelly, et al., 2008; Larm et al., 2008; Richardson, 1996; SAMHSA, 1998; Sells and Simpson, 1979; Winters et al., 2007), there are only a few studies reporting evaluation of remaining treatment effects long after adolescents entered programs (e.g., 5–8 years post admission; Dishion et al., 1999, 2002; Hennggeler et al., 2002; Vaglum and Fossheim, 1980; Winters et al., 2007). This small body of literature provides at best limited support for the long term sustainability of adolescent substance abuse treatment. For example, modest treatment effects were reported by Vaglum and Fossheim (1980), but several aspects of this study (e.g., the era, the intensive type of treatment delivered, and the nature of the treated population) limit its relevance. Of the more recent studies, one (Dishion et al., 1999, 2002) found lasting negative three year effects for youths randomly assigned to a 12-week parent/peer intervention relative to those in a control condition, leading the authors to discuss the possible iatrogenic effects of adolescent interventions that are delivered in aggregate settings. The other recent studies provide more promising results, but are still limited; Hennggeler et al. (2002) found that juvenile offenders randomly assigned to evidence-based Multisystemic Therapy had significantly lower rates of aggressive criminal behavior four years later relative to those assigned to community-based substance abuse treatment, but effects for drug use were mixed. Finally, Winters et al. (2007) report promising treatment effects among non-adjudicated youth for a 12-step based drug treatment program at 1, 4, and 5.5 years after treatment entry, with those in the treatment condition showing lower drug involvement relative to a waiting list group. However, aspects of this study design (e.g., the small sample size and nonrandom assignment to the waitlist) make it somewhat inconclusive.

Clearly there is a need for more information about the sustainability of substance abuse treatment effects among adolescents over the long term; to date there is no such evidence for juvenile offenders receiving community-based treatment – a subpopulation that currently represents the majority of adolescent treatment admissions. The adolescent outcomes project (AOP) is a longitudinal study of 449 youths recruited from a juvenile hall setting and referred either to Phoenix Academy, a therapeutic community treatment program, or another group home setting. As stated earlier, analyses of 12-month follow-up data revealed that adolescents who entered Phoenix Academy had significantly better substance use and psychological functioning outcomes relative to youths who were assigned to other probation dispositions (Morral et al., 2004). The cohort has been reassessed at 6, 7.25 and 8.5 years post-baseline providing a unique opportunity to examine the long-term effects of treatment during the transition from adolescence to young adulthood.

In this article, we examine whether the treatment effects (Phoenix Academy vs. other group home) on substance use and psychological outcomes are maintained into early adulthood, and whether other outcomes such as employment, criminal activity, and institutionalization differ according to treatment condition.

2. Methods

2.1 Participants

The study sample consists of adolescent offenders from the Los Angeles County juvenile probation system who were originally sent to Phoenix Academy (PA) or one of six other large group homes from February 1999 to January 2000. In order to increase the PA sample size, recruitment of juveniles assigned to PA was extended for four additional months until May 2000. All recruitment and study procedures were approved by the juvenile court, the probation department, and RAND's Institutional Review Board. All participants were legal wards of the Los Angeles Superior Courts, which provided consent to interview youths in its care who met the study eligibility requirements and offered their own voluntary informed assent. Parents of youth were notified that their child volunteered to participate in the study, and were given a phone number to call if they wished to remove their child from the study.

The six comparison group homes were chosen on the basis of interviews with probation officers in charge of making referrals to community placements. The officers identified seven candidate group homes and six of these programs agreed to participate. These programs proved to be comparable to PA on a range of factors including size, planned duration, staffing, and probation referral patterns. Although all programs offered some type of substance abuse treatment services, only PA specialized in such services, offering a therapeutic community intervention tailored for adolescents. In contrast, the other group homes offered less intensive services, such as drug education classes and the availability of drug and alcohol self-help groups. A more detailed discussion of program characteristics is available (Morral et al., 2003).

The study attempted to recruit all eligible youth referred by probation to any of these seven group homes (PA, plus the six other identified by the probation officers) during the study recruitment period. Youths eligible for the study were required to: 1) be between 13- and 17-years old at study entry, 2) provide a written informed assent to participate in the research, and 3) provide permission to notify a parent or legal guardian of study participation. The study excluded youths if: 1) their facility with English was too weak to participate in the English language interviews, 2) they were admitted to a residential program before they could be interviewed by RAND field staff, or 3) a parent requested their child be excluded.

Of the 449 youths successfully recruited (78% of those possibly eligible to participate), 175 were admitted to PA as their first post-detention placement (PA condition) and the remaining 274 received some other disposition (COMP condition). Some (n=59) cases in the comparison group were originally referred to PA but never admitted there. More generally, about 60% of the COMP condition cases were admitted to one of the six comparison group homes with the remainder entering other residential group homes (n=78), a probation camp (n=8), or had other dispositions, including home on probation, jail hospitalization, and absconded before placement (n=17). Thus, the COMP condition is representative of the universe of probation dispositions experienced by youths meeting the eligibility requirements who do not enter the PA.

2.2 Attrition

This study uses data from the baseline, 3, 6, 12, 72, 87 and 102-months follow-ups and includes 412 (92%) participants who completed any of the long-term follow-up interviews at 72, 87 or 102 month; a very high proportion of these 412 cases completed each wave of data collection (91%, 92%, 93%, 84%, 88%, and 87%, respectively for the 3, 6, 12, 72, 87, and 102 month interview). Of the 37 cases from the original sample not included in this study, 11 were dead, 25 refused to participate and/or were not located over the three waves, and one was too ill at all three waves. The 37 cases lost to long term follow-up generally had fewer problems at baseline than the cases in the study sample (e.g., differences were observed for several drug use variables, criminal activity, health problems, and institutionalization).

2.3 Procedures

During the recruitment period, study interviewers reviewed Juvenile Hall detention logs daily to identify eligible candidates whom they recruited for the study. Upon receiving informed assent from the youths, the first face-to-face interviews occurred immediately in an attorney interview room within the detention facility, prior to any placement in a group home or other facility. Participants were promised confidentiality and remunerated with a gift worth $15. Follow-up interviews occurred in locations convenient for the participant that afforded auditory privacy and safety for the interviewer. However, if respondents were residing outside the Los Angeles County area, a slightly reduced length version of the interview was conducted by telephone. At each wave between 26% and 35% of completed interviews were done by phone. Respondents were compensated up to $75 for their time.

2.4 Measures

2.4.1 Instrument

The principal data collection instrument at each of the assessments was a version of the Global Appraisal of Individual Needs adapted for local implementation (GAIN; Dennis, 1998). The GAIN is a structured clinical interview collecting information on eight main topic domains (background, substance use, physical health, risk behaviors, mental. health, and environment, legal, and vocational factors). Staff trained and certified in GAIN administration conducted the interviews. The first interview used the baseline version of the GAIN and required, on average, 91 minutes to complete (SD=22). The remaining interviews used modified versions of the GAIN which include a subset of the baseline GAIN items and selected additional items (e.g., detailed victimization information, perceived support while incarcerated).

2.4.2 Outcome measures

We evaluated a total of 16 outcomes related to substance use, criminal activity, psychological functioning, institutionalization, recovery, and general functioning. Because the majority of these measures are highly skewed in this population with many study participants reporting values of zero at each wave, we modeled dichotomous indicators for presence versus absence of each of these outcomes.

Substance use outcomes included absence of substance problems, past month abstinence and tobacco use. The Substance Problem Index is a 16-item symptom count of substance abuse and dependence symptoms listed in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual, Fourth Edition (American Psychiatric Association, 1994). In the study sample, this scale has a high internal reliability (α=0.92), and in a test-retest study spanning 90 days, reliability of adolescent reports on this scale was found to be good (r=.73; Dennis et al., 2000). Respondents indicating no problems on this index during the past month were assigned a value of 1 on this outcome variable; those endorsing any problems in the past month were assigned a 0. A dichotomous indicator of past month abstinence was derived based on responses to recency of use of alcohol and 12 classes of drugs (e.g., marijuana, hashish; crack or freebase cocaine; pain killers, analgesics; heroin), as well as an item assessing recency of `being drunk or high for most of the day'. Respondents were assigned a value of 0 (not abstinent) on this indicator if they indicated use of any of these substances within the past 30 days. Recent tobacco use was measured with a single item asking the number of cigarettes smoked or times using smokeless tobacco products in the past 90 days. Respondents indicating any smoking or use of tobacco products were assigned a 1 for this dichotomous indicator, all others were assigned a 0. We also measure whether or not a participant is living drug free in the community with an indicator of recovery that equals one if the participant 1) is not in detention at the time of the interview; 2) has not been institutionalized in any other controlled environment for more than 15 of the last 90 days; and 3) reports no substance use or symptoms of substance abuse or dependence in the past month.

Crime outcomes included indicators for whether or not the participant reported property, violent or drug crimes, or crimes of any kind in the past 90 days. Each measure sums across multiple specific crimes the number of acts committed, and the outcome equals one if the sum is greater than zero and zero otherwise. For example, property crime frequency during the past 90 days is the sum of self reported acts of vandalism, forgery, petty theft, grand larceny, and breaking and entering crimes. A respondent would get a score of one on this outcome by reporting that one or more of these types of acts were committed in the past 90 days. The outcome indicator for any crime takes the value of 1 if any of the property, drug, or violent crime indicators is 1 and 0 otherwise.

Psychological functioning outcomes were assessed with three scales based on the Hopkins Symptom Checklist (Derogatis et al., 1974). The Somatic Symptoms Index (α=0.68), a 4-item symptom count assessing somatic symptoms commonly associated with psychological distress (e.g., headaches, dizziness); the Depressive Symptoms Index (α=0.74), which counts the presence of 6 symptoms associated with depression (e.g., feeling sad or depressed, loss of energy, irritability); and the Anxiety Symptoms Index (α=0.79), which counts the presence of 10 anxiety- related symptoms (e.g., feeling anxious, restlessness, phobias, etc.). For each of these scales we coded a dichotomous indicator that equals one for one or more symptoms and zero otherwise.

Institutionalization in a controlled environment was measured in two ways. First, we used a dichotomous indicator for whether or not the participant was institutionalized in any controlled environment for more that two weeks in the past 90 days. Second we measured long term incarceration with a dichotomous measure of whether or not the participant was incarcerated in jail, prison, or other detention center for 30 or more days in the past 90 days.

General functioning was measured with three indicator variables. The first was a measure of general health status equal to one if respondents reported very good or excellent health on an item rating their health in general from excellent to poor. The others were indicators of whether or not the participant reported 1) graduating from high school or obtaining a GED, and 2) being employed in the past 90 days.

Pretreatment characteristics

Group differences between PA and COMP condition youths were assessed on 88 pre-treatment variables that measure the constructs identified by American Society for Addiction Medicine for guiding treatment placement and as important correlates of treatment outcomes (Mee-Lee et al., 2001) including measures assessing aspects of substance use, mental health and physical health treatment histories and need; schooling, employment, criminal justice history; psychological measures; measures of problem behaviors; measures of support and stress; age, race, and gender1.

2.5 Statistical approach

2.5.1 Missing data

The intake items used to adjust for pre-existing differences between group were subject to low rates of missing data, 1.1% on average (SD=1.4%), within completed surveys. A regression model hot-deck imputation procedure was used to impute the small numbers of missing items, so that scale scores could be based on all scale items (Morral et al., 2004). Data was not imputed for whole surveys that were missed or for the outcome variables.

2.5.2 Case-mix adjustment

The PA and COMP condition groups were similar on many pre-existing characteristics. However, some observed pretreatment differences did exist which could bias results. Continuing with the approach used to examine the first year follow-up outcomes (Morral et al., 2004), we addressed the issue of potential confounding by pretreatment differences by weighting the COMP condition cases so that the weighted distributions of 88 pre-treatment characteristics for this group matched those of the PA condition. For each COMP condition case the weight equals pi/(1−pi), where pi describes the probability that case i belongs to the PA condition given the value of the 88 pre-treatment variables.

The propensity scores were computed using Generalized Boosted Models (GBM) which is a flexible, non-parametric estimation technique that can account for a large number of variables in the propensity score model (McCaffrey et al., 2004). The weight estimation was implemented using the “twang” package in the R statistical computing environment which tuned the adaptive GBM model to yield good balance between the groups as assessed by several different criteria that it reports (Ridgeway et al., 2006).

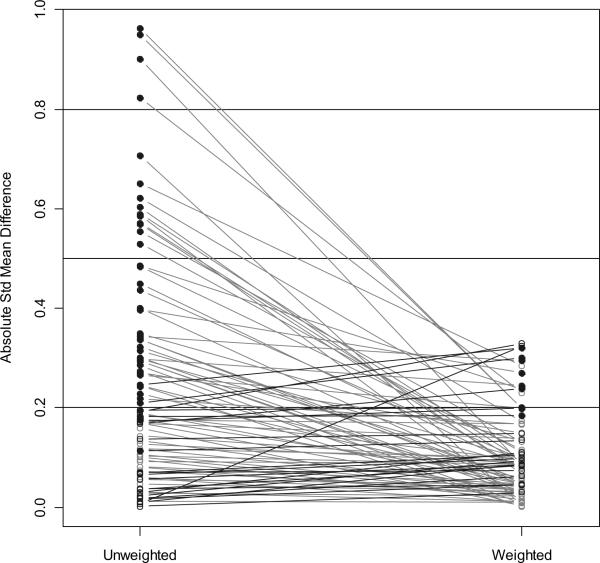

One measure used in assessing the balance is the standardized mean of the weighted group means. For a given variable, the standardized mean difference (SMD) equals the absolute value of the difference between the means of the PA condition and the (weighted) mean of the COMP condition divided by the standard deviation of the PA condition. These values are similar to effect sizes (Cohen, 1962) and an SMD > 0.25 is considered to be problematic (Ho et al., 2007). We also compared the weighted distributions of the pretreatment variables for the two conditions using the Kolmogrov-Smirnov (KS) statistic, which measures the discrepancies between distributions from two groups. Overall these differences were very small: the maximum KS statistic was 0.15 and smaller than we would expect from almost 95% of the samples we might have obtained from randomization.

Figure 1demonstrates the balance between variable distributions for the PA and COMP conditions in terms of the absolute value of SMD for the 88 pre-treatment variables before and after weighting. As shown in Figure 1, the groups differed substantially on many variables before weighting with the absolute SMD being greater than 0.25 for 37% of variables, with the largest differences existing for treatment motivation, use of marijuana in the past year, and substance use problems. After weighting, the groups are much more similar. All of the very large differences have been removed; the largest absolute SMD is just under .33 and just nine variables have SMDs that exceed 0.25 in absolute value2.

Figure 1.

Comparison of Phoenix Academy and Comparison Condition Cases on Pre-Treatment Covariates Measured at Intake Before and After Weighting. Dots represent the absolute standardized mean difference (SMD) for each of the 88 pre-treatment variables. For each variable, lines connect dots for the same variable with and without weighting. Solid dots denote statistically significant differences (p < 0.05). Dark gray lines indicate variables for which the absolute SMD increased with weighting; light gray lines indicate variables for which the absolute SMD decreased with weighting.

2.5.3 Outcome Models

We estimated the effect of PA on the trajectory over the post intake period of each of the outcomes described above. Building on the model for the first year follow-ups developed by Morral et al. (2004), in which the trajectories for the two conditions have a common intercept and then are modeled separately by condition as a piecewise linear function with one linear trend from baseline to three months and a second contiguous linear trend from 3 to 12 months, the models in these analyses also include a separate linear trend (mean and slope) for each group for the log odds of outcomes at the 72, 87, and 102 month follow-ups. For incarceration and institutionalization we fit a model with separate indicators for waves 3, 6, and 12 to address lack-of-fit from the piecewise linear model used to represent the first year after intake. The models also include a small number of pre-treatment variables on which the two groups differed after weighting.

We used generalized estimating equations (GEE) implemented in the Stata xtreg procedure (Statacorp, 2007) to estimate the model parameters and test for condition effects. We tested for long-term PA effects by testing the null hypothesis of no differences between groups in the log-odds of outcomes across the three long-term follow-up interviews. We report the p-values for testing each outcome separately and report significance using the step-down method to control for familywise error rates (Benjamini and Hochberg, 1995) within groups of outcomes (substance use, crime, institutionalization, psychological functioning, and general functioning). We also tested for PA and COMP differences in the change in the mean outcome from 12 months to 72 months.

To summarize our model results we report model estimated marginal means for youth likely to be disposed to PA. Using our outcome model, we estimated the expected value for the outcome for each participant at each wave of data collection using his or her observed values on the pretreatment variable included in the model and assuming he or she was disposed to PA, regardless of the actual disposition. We then estimated the weighted average of the expected outcomes to obtain the expected outcome following treatment for youth likely to be disposed to PA. We repeated the process treating each participant as being assigned to the COMP condition. Differences in the values provide estimates of the treatment effect at each follow-up time point.

3. Results

3.1 Participants

Participants were an average age of 15.50 years old at the baseline survey. The majority were male (86%) and of Hispanic/Latino ethnicity (54%), with 17% White, 15% African American, and 14% mixed or other ethnicity. With respect to alcohol and drug use history, 89% of the sample reported using drugs or alcohol for the first time before age 15, 40% reported prior attendance at AA, CA, NA or some other self-help group, 78% met criteria for abuse, and 55% met criteria for dependence. The preferred substance was marijuana (52%), but some respondents reported alcohol (11%), amphetamines (7%), or crack/cocaine (6%) as their preferred drug of choice. Despite the extensive history of use, 59% of the respondents reported that they did not need treatment for any substance. With the exception of gender (PA condition had significantly fewer males than COMP, 80% vs. 93%, p<.01) weighted comparisons between PA and COMP revealed no differences in these baseline characteristics.

Treatment exposure varied among participants, but there were no systematic differences between PA and COMP youths. Self-reports of the number of days spent in residential treatment centers at baseline, and Months 3, 6, and 12 were 5.7, 55.0, 49.9, and 35.5 respectively for PA, and 7.5, 47.1, 42.9, and 31.2 for COMP, t(411)=−.86, t(372)=.24, t(382)=.27, t(378)=.44. In addition, the average length of stay in the index placement did not differ significantly between the two groups (PA=156.61, COMP=160.65, t(412)=−.22).

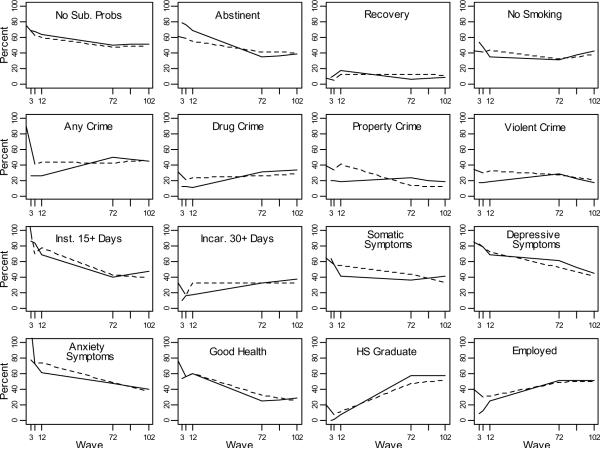

3.2 Phoenix Academy Effects

Figure 2 summarizes the marginal means from 3 months to 102 months post treatment for PA and COMP conditions for all 16 outcomes. Table 1 presents estimated PA effects on long-term outcomes and tests of these effects. As shown in the figure and table, there is no evidence of treatment effects by the end of the observation period on any outcome except property crimes. The differences in the rates of outcomes are generally small. For property crimes, about 60 percent of cases assigned to PA report committing a property crime in the past 90 days, 7 percentage points higher than COMP. However, this effect is not significant after we account for testing for effects on multiple outcomes. Also, there were baseline differences in the groups on property crimes that contribute to the differences at follow-up and add to the likelihood the results are spurious.

Figure 2.

Outcomes Post Intake for Phoenix Academy (solid line) and Comparison (dashed line) Conditions.

Table 1.

Tests of Treatment Effects on Long-Term Outcomes and the Course of Post-Intake Outcomes

| Mean at Long Term Follow-up | Change from 12 month to Long Term Follow-up | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phoenix | Phoenix | |||||

| Outcome | Comparison | Academy | Difference | Comparison | Academy | Difference |

| No Substance Abuse | ||||||

| Problemsb | 48.3 | 50.7 | 2.4 | −12.0 | −12.5 | −0.5 |

| Abstinentb | 41.0 | 36.8 | −4.3 | −13.6 | −31.5 | −17.9* |

| In recovery | 12.4 | 8.0 | −4.4 | 0.2 | −9.1 | −9.3 |

| No Smokinga | 35.7 | 37.3 | 1.6 | −8.2 | 2.7 | 10.9 |

| Any criminal activitya | 44.4 | 47.3 | 2.9 | 0.3 | 21.2 | 20.9* |

| Any drug crimesa | 27.4 | 32.5 | 5.1 | 3.8 | 21.1 | 17.3* |

| Any property crimesa | 13.3 | 20.8 | 7.6* | −27.6 | 2.1 | 29.7*** |

| Any violent crimesa | 24.1 | 23.1 | −1.0 | −9.0 | 4.0 | 12.9* |

| Institutionalized 15+ daysa | 40.8 | 43.5 | 2.7 | −36.6 | −25.0 | 11.6 |

| Incarcerated 30+ daysa | 32.5 | 34.5 | 2.0 | −0.1 | 17.0 | 17.1 |

| Any somatric symptomsa | 38.2 | 38.7 | 0.4 | −16.4 | −2.3 | 14.1 |

| Any depressive symptomsa | 47.1 | 52.8 | 5.7 | −24.7 | −16.1 | 8.7 |

| Any anxiety symptomsa | 42.6 | 44.0 | 1.4 | −31.4 | −17.0 | 14.4* |

| Good or excellent health | 29.1 | 27.0 | −2.1 | −31.3 | −33.0 | −1.7 |

| HS Graduate | 49.5 | 57.3 | 7.7 | 37.5 | 49.1 | 11.6 |

| Employeda | 49.6 | 51.3 | 1.7 | 18.8 | 26.1 | 7.3 |

Past 90 days;

Past 30 days;

significant at p<0.05,

p<.01,

p<0.001

Unlike at the long-term follow-up, there were large differences between the groups at the 12 month follow-up for several outcomes and there were significant differences in the evolution of outcomes from 12 months to long-term follow-up. The most notable changes were for criminal outcomes. Rates of crime were suppressed during the first year following disposition to the PA relative to COMP but between the 12 and 72 month follow-up youth assigned to PA increased their criminal activity to COMP condition levels (drug and violent crimes), or maintained their level while the COMP condition level declined from the high rates of adolescence (property crimes).

Changes between the groups were also notable for psychological functioning. For both somatic and anxiety symptoms, PA yielded early declines in the proportion of youths reporting one or more symptoms relative to the COMP condition, but declines did not continue or slowed in the interval from 12 to 72 months whereas they increased for the COMP condition so that by the long-term follow-up the groups were again functioning at similar rates. Similar results hold for the past month abstinence: early gains following disposition to PA eroded relative to the COMP condition as youth become less likely to be abstinent following either disposition but the change was faster for the PA condition. Recovery shows a similar pattern because lack of abstinence keeps people from meeting the recovery criteria. For smoking the early increases following PA eroded as youths increased their smoking between 12 and 72 months following the COMP dispositions but not following PA. Few differences of note exist in the remaining outcomes.

4. Discussion

This paper offers the first assessment of the long term effects associated with admission into a community-based adolescent treatment program previously shown to have significantly improved 12-month treatment outcomes in comparison to rehabilitation programs of similar size and structure, but which did not offer specialty substance abuse treatment interventions. Few studies have examined whether early positive substance abuse treatment effects carry forward to produce lasting benefits for clients who receive such care, especially for adolescent substance abusing clients. Conceivably, the improvements associated with treatment will persist, or even trigger a series of positive events that might otherwise have been impossible, leading to snowballing improvements (e.g,. less drug use leads to better educational outcomes, which lead to better vocational outcomes, which reinforce continued abstinence from drugs, etc.). Less optimistically, positive effects may be short lived, either because the intervention produces only temporary changes, as is found for weight changes induced by many diets, or, as Shrout and Bolger (2002) suggest, the detectable positive effects of treatment dissipate over time simply because distal effects are more likely to be “(a) transmitted through additional links in a causal chain, (b) affected by competing causes, and (c) affected by random factors” (p. 429).

Our findings show no evidence of persistent effects of treatment, much less evidence of snowballing benefits. Although there was some overall improvement in outcomes from baseline to the long term follow-up, and this study reproduces our original finding of significantly better outcomes for the PA group 12 months after treatment assignment (Morral et al., 2004), we find little evidence that outcome differences persist 9 years after entering Phoenix Academy versus one of the Comparison group homes. Instead, long term follow-up outcomes for the two groups were largely similar, with the exception of property crime, which favored the COMP condition. In general, the 12-month improvements observed for PA were offset in the subsequent follow-up period in one of two ways. For some outcomes, 12-month PA improvements were matched with equally sharp deteriorations in outcomes after 12-months. For other outcomes, the COMP group showed greater improvements after 12-months than PA, erasing PA's initial relative benefits. In exploratory analyses not reported here, we also found that 12 month status on many variables did not predict later outcomes for either group. This is again consistent with the Shrout and Bolger (2002) conjecture that there may be a multitude of factors influencing the evolution of adolescents' outcomes, effectively drowning distal factors and effects in a sea of competing influences.

The degradation of treatment effects over time for high risk youths should not be taken as evidence that treatment is ultimately no better than no treatment. Even if the effects are truly only short-lived and youths would eventually reach the slightly better levels of functioning through natural maturation, treatment may be cost-effective, or even life-saving if it reduces drug use at a time when adolescents may be at highest risk of harming themselves and others by, for instance, driving under the influence. Moreover, every crime not committed by accelerated reductions in crime has cost savings in terms of loss to the victims, police investigations and so forth. Accelerated improvement in mental health status potentially can reduce costs required for additional treatment. It is good news that some outcomes improved on average for both conditions. It is disappointing that the early effects of treatment did not carry forward to equally strong relative improvements in functioning in early adulthood, but the temporal reductions in costs from even the short term treatment effects could be of value to our society.

What can we do to prevent short term treatment effects from eroding? A recent study demonstrates that continuing care – even at a minimal level – can have a significant impact on subsequent outcomes (Garner et al, 2007). Winters et al (2007) also report that treatment effects were stronger for individuals who were involved in aftercare. Unfortunately, there was not sufficient data available in this study to formally examine the role of aftercare as a possible mediator of outcomes. However, considering the deterioration of strong short-term treatment effects observed in this study, it may be beneficial and cost-effective to provide structured follow-up care for youths completing community-based treatment programs like Phoenix Academy so that the pressure of intervening factors such as negative peer and neighborhood influences can be minimized and gains can be sustained for longer periods.

Without any formal follow-up support in place, it may be unrealistic to expect that one dose of treatment will have long term effects, especially on high-risk adolescents such as those followed in this study who have to confront multiple risk factors upon release from residential treatment, including family, peers, and neighborhood, as they are returned to the environmental context they originated from. Indeed, McLellan et al. (2005) argue that drug dependence may best be conceptualized as a chronic condition like diabetes or asthma that needs to be managed over the lifetime. From this perspective, treatment effects are largely concurrent with treatment, and not expected to be sustainable without some level of ongoing care such as Alcoholics Anonymous or other self-help programs. Even in this case, relapses are more the rule than the exception; many individuals suffering from drug dependence will require multiple doses of intensive treatment to manage their condition and maintain a reasonable level of functioning.

These results should be considered in light of several study limitations. First, the outcomes are based on participant self-report and may not accurately reflect actual functioning. However, the bias of self-report would be applicable to both conditions in the long term, so is not likely to have impacted inferences about long term treatment effects. A second limitation is the large gap in time during which there is no information about the study participants (between the 12 and 72 month interviews). This lack of information makes it difficult to come to any clear conclusions about the likely mechanisms explaining the erosion of the PA 12-month treatment effect relative to COMP. We also relied on weights to match the two conditions, and although we were able to achieve a well matched comparison group on nearly all of more than 80 pretreatment characteristics, it could be that groups differed on some important but unmeasured pretreatment characteristics that are risk factors for differential outcomes, and so would undermine our matching strategy. Finally, these results are based on a sample of adjudicated youths, and do not necessarily generalize to youth referred to substance abuse treatment from other sources. This study also has a number of strengths including the outstanding follow-up rates of this high-risk youth sample, the rigorous analytic methods that allow for an evaluation of treatment effects in an observational study, and the extensive follow-up period evaluated – a feature which is rare in outcomes studies currently available in the literature.

There have been very few studies evaluating long-term substance abuse treatment outcomes for high-risk adolescents, and available evidence is limited and inconclusive. In this paper, we evaluated the sustainability of observed 12-month treatment effects of a community-based residential substance abuse treatment program over a long-term follow-up period. Relative to Comparison cases who were referred from juvenile hall to group home settings, adolescents referred to Phoenix Academy, a residential therapeutic community treatment program, did not show any superior outcomes when evaluated 72, 87, and 102 months after treatment referral. Although the erosion of observed 12-month treatment gains is disappointing, the savings in societal costs associated with the temporary decrease in adolescent crime and substance use may still represent an overall benefit to society. The results also lend support to the idea that structured aftercare and multiple treatment „doses” may be necessary to achieve sustainable long-term outcomes.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Role of funding source: This work was supported by Grant R01DA016722 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse. NIDA had no further role in study design; collection, analysis and interpretation of the data; the writing of this report; or in the decision to submit this paper for publication.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: All authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

A supplementary data table is available with the online version of this article at doi:xxx/j.drugalcdep.xxx . . .

Appendix Table A.1 [give web location] gives a complete list of variables and their mean values for each condition available with the online version of this paper at doi:xxx/j.drugalcdep.xxx . . .

Balance measures for all variables before and after weighting are available in appendix Table A.1 [give reference] is available with the online version of this paper at doi:xxx/j.drugalcdep.xxx . . . .

References

- American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV) American Psychiatric Press, Inc.; Washington, DC: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J R Stat Soc Ser B. 1995;57:289–300. [Google Scholar]

- Breda CS, Heflinger CA. The impact of motivation to change on substance use among adolescents in treatment. J Child Adolesc Subst Abuse. 2007;16:109–124. [Google Scholar]

- Brown SA, D'Amico EJ, McCarthy DM, Tapert SF. Four-year outcomes from adolescent alcohol and drug treatment. J Stud Alcohol. 2001;62:381–388. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2001.62.381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catalano RF, Hawkins JD, Wells EA, Miller J. Evaluation of the effectiveness of adolescent drug abuse treatment, assessing the risk for relapse, and promising approaches for relapse prevention. Int J Addict. 1991;25:1085–1140. doi: 10.3109/10826089109081039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciesla JR, Valle MS, Sherilynn F. Measuring relapse after adolescent substance abuse treatment: A proportional hazard approach. Addictive Disorders and Their Treatment. 2008;7:87–97. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. The statistical power of abnormal-social psychological research: A review. J Abnorm Soc Psychol. 1962;65:145–153. doi: 10.1037/h0045186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennis ML. Global Appraisal of Individual Needs (GAIN) Manual: Administration, Scoring and Interpretation. Lighthouse Publications; Bloomington, IL: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Dennis ML, Babor TF, Diamond G, Donaldson J, Godley SH, Titus JC, Webb C, Herrell J. The cannabis youth treatment (CYT) experiment: Preliminary findings. Center for Substance Abuse Treatment, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Department of Health and Human Services; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Dennis ML, Titus JC, Funk RR, McDermeit M. Global Appraisal of Individual Needs (GAIN): Selected methodological findings. Presented at the PETSA Cross Site Meeting; Bethesda, MD. 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Derogatis LR, Lipman RS, Rickels K, Uhlenhuth EH, Covi L. The Hopkins symptom checklist (HSCL): a self-report inventory. Behavioural Science. 1974;19:1–15. doi: 10.1002/bs.3830190102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, McCord J, Poulin F. When interventions harm. Peer groups and problem behavior. Am Psychol. 1999;54:755–764. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.54.9.755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, Poulin F, Burraston B. Peer group dynamics associated with iatrogenic effect in group interventions with high-risk young adolescents. New Dir Child Adolesc Dev. 2001;91:79–92. doi: 10.1002/cd.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doyle H, Delaney W, Tobin J. Follow-up study of young attenders at an alcohol unit. Addiction. 1994;89:183–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1994.tb00877.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godley MD, Godley SH, Dennis ML, Funk RR, Passetti LL. The effect of assertive continuing care on continuing care linkage, adherence and abstinence following residential treatment for adolescents with substance use disorders. Addiction. 2007;102:81–93. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01648.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall JA, Smith DC, Easton SD, An H, Williams JK, Godley SH, Jang M. Substance abuse treatment with rural adolescents: Issues and outcomes. J Psychoactive Drugs. 2008;40:109–120. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2008.10399766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henggeler SW, Borduin CM, Melton GB, Mann BJ, Smith LA, Hall JA. Effects of multisystemic therapy on drug use and abuse in serious juvenile offenders: A progress report from two outcome studies. Fam Dynamics Addict Q. 1991;1:40–51. [Google Scholar]

- Henggeler SW, Clingempeel WG, Brondino MJ, Pickrel SG. Four-year follow-up of multisystemic therapy with substance-abusing and substance-dependent juvenile offenders. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2002;41:868–874. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200207000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho D, Imai K, King G, Stuart EA. Matching as nonparametric preprocessing for reducing model dependence in parametric causal inference. Political Analysis. 2007;15:199–236. [Google Scholar]

- Hser YI, Grella CE, Hubbard RL, Hseih SC, Fletcher BW, Brown BS, Anglin MD. An evaluation of drug treatments for adolescents in 4 US cities. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2001;58:689–695. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.58.7.689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly JF, Brown SA, Abrantes A, Kahler CW, Myers M. Social recovery model: an 8-year investigation of adolescent 12-step group involvement following inpatient treatment. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2008;32:8, 1468–78. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2008.00712.x. Epub 2008 Jun 28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim RL, Jackson DS. Outcome evaluation findings of a Hawaiian culture-based adolescent substance abuse treatment program. Psychol Serv. 2009;6:43–55. [Google Scholar]

- Larm P, Hodgins S, Larsson A, Samuelson YM, Tengström A. Long-term outcomes of adolescents treated for substance misuse. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2008;96:79–89. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.01.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liddle HA, Dakof GA, Turner RM, Henderson CE, Greenbaum PE. Treating adolescent drug abuse: A randomized trial comparing multidimensional family therapy and cognitive behavior therapy. Addiction. 2008;103:1660–1670. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02274.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liddle HA, Rowe CL, Dakof GA, Henderson CE, Greenbaum PE. Multidimensional family therapy for young adolescent substance abuse: Twelve-month outcomes of a randomized controlled trial. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2009;77:12–25. doi: 10.1037/a0014160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCaffrey DF, Ridgeway G, Morral A. Propensity Score Estimation with Boosted Regression for Evaluating Causal Effects in Observational Studies. Psychol Methods. 2004;9:403–425. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.9.4.403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLellan AT, McKay JR, Forman R, Cacciola J, Kemp J. Reconsidering the evaluation of addiction treatment: from retrospective follow-up to concurrent recovery monitoring. Addiction. 2005;100:447–458. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2005.01012.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mee-Lee D, Shulman GD, Fishman M, Gastfriend DR, Griffith JH, editors. ASAM Patient Placement Criteria for the Treatment of Substance-Related Disorders, Second Edition-Revised (ASAM PPC-2R) American Society of Addiction Medicine, Inc.; Chevy Chase, MD: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Morral AR, Jaycox LH, Smith W, Becker K, Ebener P. An evaluation of substance abuse treatment services for juvenile probationers at Phoenix Academy of Lake View Terrace. In: Stevens S, Morral AR, editors. Adolescent Substance Abuse Treatment in the United States: Exemplary Models from a National Evaluation Study. Haworth Press; New York: 2003. pp. 213–234. [Google Scholar]

- Morral AR, McCaffrey DF, Ridgeway G. Effectiveness of community based treatment for substance abusing adolescents: 12-month outcomes from a case-control evaluation of a Phoenix Academy. Psychol Addict Behav. 2004;18:257–268. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.18.3.257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson DW. Drug rehabilitation in a treatment farm setting: The Nitawgi Farm experience, 1978–1990. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 1996;17:258–261. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ridgeway G, McCaffrey DF, Morral AR. Toolkit for the Weighted Analysis of Nonequivalent Groups: A Tutorial for the twang Package. 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Rivaux SL, Springer DW, Bohman T, Wagner EF, Gil AG. Differences among substance abusing latino, anglo, and african-american juvenile offenders in predictors of recidivism and treatment outcome. J Soc Work Pract Addict. 2006;6:5–29. [Google Scholar]

- SAMHSA (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration) Services Research Outcomes Study. Department of Health and Human Services; Rockville, MD: 1998. (DHHS Pub No. (SMA) 98–3177). [Google Scholar]

- SAMHSA (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration), Office of Applied Studies . National Admissions to Substance Abuse Treatment Services, DASIS Series: S-43. Department of Health and Human Services; Rockville, MD: 2008. Treatment Episode Data Set (TEDS): 1996–2006. (DHHS Publication No. (SMA) 08–4347). [Google Scholar]

- Sells SB, Simpson DD. Evaluation of treatment outcome for youths in the Drug Abuse Reporting Program (DARP): a follow-up study. In: Beschner GM, Friedman AS, editors. Youth Drug Abuse. Lexington Books; Lexington, MA: 1979. pp. 571–628. [Google Scholar]

- Shane P, Diamond GS, Mensinger JL, Shera D, Wintersteen MB. Impact of victimization on substance abuse treatment outcomes for adolescents in outpatient and residential substance abuse treatment. Am J Addict. 2006;15:34–42. doi: 10.1080/10550490601003714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shrout PE, Bolger N. Mediation in experimental and nonexperimental studies: new procedures and recommendations. Psychol Methods. 2002;7:422–445. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- StataCorp . Stata Statistical Software: Release 10. StataCorp LP; College Station, TX: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Subramaniam GA, Stitzer MA, Clemmey P, Kolodner K, Fishman MJ. Baseline depressive symptoms predict poor substance use outcome following adolescent residential treatment. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2007;46:1062–1069. doi: 10.1097/chi.0b013e31806c7ad0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaglum P, Fossheim I. Differential treatment of young abusers: a quasi-experimental study of a “therapeutic community” in a psychiatric hospital. J Drug Issues. 1980;10:505–515. [Google Scholar]

- Waldron HB, Kaminer Y. On the learning curve: the emerging evidence supporting cognitive-behavioral therapies for adolescent substance abuse. Addiction. 2004;99:93–105. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00857.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waldron HB, Turner CW. Evidence-based psychosocial treatments for adolescent substance abuse. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2008;37:238–61. doi: 10.1080/15374410701820133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weisz JR, Weiss B, Donenberg GR. The lab versus the clinic: effects of child and adolescent psychotherapy. Am Psychol. 1992;47:1578–1585. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.47.12.1578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams RJ, Chang SY, Addiction Centre Research Group A comprehensive and comparative review of adolescent substance abuse treatment outcome. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2000;7:138–166. [Google Scholar]

- Winters KC. Treating adolescents with substance use disorders: An overview of practice issues and treatment outcome. Subst Abus. 1999;20:203–225. doi: 10.1080/08897079909511407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winters KC, Stinchfield RD, Opland E, Weller C, Latimer WW. The effectiveness of the Minnesota Model approach in the treatment of adolescent drug abusers. Addiction. 2000;95:601–612. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2000.95460111.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winters KC, Stinchfield RD, Latimer WW, Lee S. Long-term outcome of substance-dependent youth following 12-step treatment. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2007;33:61–69. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2006.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.