Abstract

Platelet aggregates are present in parenchymal vessels as early as 10 minutes after experimental subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH). Structural injury to parenchymal vessel walls and depletion of collagen-IV (the major protein of basal lamina) occur in a similar time frame. Since platelets upon activation release enzymes which can digest collagen-IV, we investigated the topographical relationship between platelet aggregates, endothelium, and basal lamina after SAH produced by endovascular perforation, using triple immunofluorescence and confocal microscopy with deconvolution. The location of platelet aggregates in relation to zymography-detected active collagenase was also examined. As reported previously, most cerebral vessels profiles contained platelets aggregates at 10 minutes after SAH. High-resolution three-dimensional image analysis placed many platelets at the ab-luminal (basal) side of endothelium at 10 minutes, and others either within the vascular basal lamina or in nearby parenchyma. By 24 hours post-hemorrhage, large numbers of platelets had entered the brain parenchyma. The vascular sites of platelet movement were devoid of endothelium and collagen IV. Collagenase activity colocalized with vascular platelet aggregates. Our data demonstrate that parenchymal entry of platelets into brain parenchyma begins within minutes after hemorrhage. Three-dimensional analysis suggests that platelet aggregates initiate or stimulate local disruption of endothelium and destruction of adjacent basal lamina after SAH.

Keywords: vascular injury, basal lamina, endothelium, collagenase, in situ Zymography, stroke

Aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) accounts for 5% of strokes and kills many within the first 48 hours by mechanisms that remain poorly understood (Broderick et al., 1994, Schievink et al., 1995). There is overall agreement that early treatment of subarachnoid hemorrhage is critical for potential reduction of the mortality rate (McKhann and Le Roux, 1998, Lawrence et al., 2001, Bederson et al., 2009, Diringer, 2009); however, mechanisms of brain injury during this early period remain poorly understood, and few treatment options currently exist.

Intracranial pressure (ICP) rises and cerebral blood flow (CBF) falls after SAH (Kamiya et al., 1983, Travis and Hall, 1987, Rasmussen et al., 1992, Bederson et al., 1995, Bederson et al., 1998). In animals, cerebral ischemia after SAH is accompanied by constriction of cerebral blood vessels 300-500 μm in diameter. In contrast, although acute cerebral ischemia occurs in humans (Staub et al., 2000, Hutchinson et al., 2002, Sarrafzadeh et al., 2003), cerebral angiography shows little evidence of acute arterial spasm (Weir et al., 1978, Grosset et al., 1993).

Using a rat model of SAH we previously identified function-altering structural changes in parenchymal microvessels (<100 μm) that could explain cerebral ischemia in human in the absence of angiographic evidence of vasoconstriction (Sehba and Bederson, 2006). We have demonstrated microvascular constriction, the presence of intraluminal platelet aggregates, loss of endothelial cell antigens, activated vascular matrix metalloproteinase-9 (MMP-9, which can degrade collagen IV), and degradation of collagen IV (the major vascular basal lamina protein), within minutes after SAH (Sehba et al., 2004, Sehba et al., 2005, Sehba et al., 2007b).

Platelets have a prominent role in both vascular obstruction and immune responses. Platelet granules contain many inflammatory and adhesion molecules which are either released or expressed upon activation (Weyrich et al., 2009). Hence, we hypothesize that platelet aggregates lodged within microvessels could initiate all of the above-mentioned vascular events, leading to structural injury in parenchymal vessels after SAH. If our hypothesis is correct then platelet aggregates should concentrate at regions of structural injury and collagenase activity. Therefore, the present study examined the topographical relationship between intraluminal platelets, endothelium and basal lamina, and collagenase activity over the first 24 hours after SAH.

Materials and Methods

All experimental procedures and protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Mount Sinai Medical Center.

Induction and characterization of subarachnoid hemorrhage

Male Sprague-Dawley rats (325-350g) underwent experimental SAH using the endovascular suture model developed in this laboratory (Bederson et al., 1995, Schwartz et al., 2000). Briefly, rats were anesthetized with ketamine-xylazine (80mg/Kg+10mg/Kg; IP), transorally intubated, ventilated, and maintained on inspired isoflurane (1% to 2% in oxygen-supplemented room air). Rats were placed on a homeothermic blanket (Harvard Apparatus, MA, USA) attached to a rectal temperature probe set to maintain body temperature at 37°C and positioned in a stereotaxic frame. The femoral artery was exposed and cannulated for blood gas and blood pressure monitoring (ABL5, Radiometer America Inc. Ohio, USA). For measurement of intracranial pressure (ICP), the atlanto-occipital membrane was exposed and cannulated, and the cannula was affixed with methylmethacrylate cement to a stainless steel screw implanted in the occipital bone. Cerebral blood flow (CBF) was measured by laser-Doppler flowmetry, using a 0.8 mm diameter needle probe (Vasamedics, Inc., St. Paul, MN, USA) placed directly over the skull away from large pial vessels in the distribution of the middle cerebral artery.

SAH was induced by advancing a suture retrogradely through the ligated right external carotid artery (ECA), and distally through the internal carotid artery (ICA) until the suture perforated the intracranial bifurcation of the ICA. This event was detected by a rapid rise in ICP and bilateral decrease in CBF. ICP, CBF, and blood pressure (BP) were monitored from 20 minutes prior to induction of hemorrhage to 10 minutes or 3 hours after hemorrhage. As animals regained consciousness and were able to breathe spontaneously they were returned to their cages. Animals were sacrificed at 10 minutes, 3 hours, or 24 hours after SAH, or 10 min after sham surgery (n=5 per time interval).

Inclusion criteria

Animals were assigned randomly to survival interval and treatment groups. ICP, CBF and BP were recorded and analyzed to ensure that all groups had comparable SAH severity, leading to exclusion of 26% of the animals. Physiological parameters of animals included in the study were ICP: baseline: 5.9±0.7 mm Hg; at SAH, 58.6±5.7 mm Hg; at 10minutes, 21±3 mm Hg; and at 60 minutes, 14.1±3.5 mm Hg. CBF fell at SAH to 11±3% of baseline, and recovered to 27±6% at 10 minutes, and to 40±11% at 60 minutes after SAH. BP was unchanged after SAH. Baseline CPP was 87±2 mm Hg, falling to 41±6 mm Hg (47% fall) at SAH and recovering to 74±6 mm Hg (85%) at 10 minutes; it stayed near this value at 60 minutes. The ICP and CBF values indicated that rats experienced moderately severe SAH (Bederson et al., 1998).

Immunostaining

Brain preparation

Animals were anesthetized and perfused with normal saline, brains were dissected and frozen in OCT. Coronal brain sections 8 or 20 um thick were cut on a cryostat and thaw-mounted onto gelatin-coated slides. Sections located at bregma –8.0, +0.2 and +1.2 (Paxinos and Watson, 1986) were used for immunofluorescence.

Reagents

Primary and secondary antibodies were as listed in Tables below.

Primary Antibodies:

| Antigen | Description | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Collagen IV | Goat polyclonal | Southern Biotechnology Associates Inc. (1340-01) |

| Rat Endothelial Cell Antigen (RECA-1) | Mouse monoclonal | Serotec (MCA970R) |

| Endothelial Barrier Antigen (EBA) | Mouse monoclonal | Sternberger (SMI-71) |

| Rat platelets | Rabbit polyclonal | Inter-Cell Technologies (ADG51440) |

Secondary Antibodies

| Antibody-label | Source | Specificity |

|---|---|---|

| donkey anti-mouse-Alexa 488 | Invitrogen (A-21202) | Minimum cross reactivity against rabbit and goat |

| donkey anti-goat Alexa 647 | Invitrogen (A-21447) | Cross adsorbed against rabbit and mouse |

| donkey anti-rabbit Rhodamine Red X | Jackson Immuno. (711-295-152) | Cross adsorbed against mouse and goat |

| donkey anti-mouse Cy5 | Jackson Immuno. (715-175-151) | Cross adsorbed against rabbit and goat |

Triple staining

Frozen cryostat brain sections were thawed, fixed with 4% freshly prepared formaldehyde, and incubated overnight at 4°C with primary antibodies directed towards collagen IV, RECA-1, and platelets. In addition some sections were stained with antibodies directed towards collagen IV, EBA, and platelets. Sections were washed and then incubated overnight at 4°C with species-specific secondary antibodies. Finally, sections were washed with PBS and coverslipped with Vectashield mounting medium (Vector labs, Burlingame, CA, USA), with or without DAPI.

Immunofluorescence and Zymography

Frozen cryostat sections of unfixed brains were thawed and coated with a thin layer of FITC-labeled DQ-gelatin solution (EnzCheck collagenase kit, Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR, USA) (Sehba et al., 2004) containing rabbit anti-platelets alone or with goat anti-collagen IV antibody. The coated sections were incubated overnight at 37°C in a humid chamber, and then incubated overnight at 4°C with species-specific secondary antibodies. Finally, sections were fixed with chilled 4% formaldehyde prepared freshly from paraformaldehyde and coverslipped.

Data Acquisition

ICP, CBF, and BP data were continuously recorded starting 20 minutes before SAH and ending 10 minutes or 3 hours after SAH (PolyView software; Grass Instruments; MS, USA). CBF data were normalized to the baseline value averaged over 20 minutes prior to SAH, and subsequent values expressed as a percentage of baseline.

Histology

Morphometry

Specimens were evaluated by an observer blinded to their identity.

Topography

High-resolution multichannel three-dimensional (z-stack) image sets were obtained by confocal microscopy (Leica SP5 DM; Leica Microsystems Inc., Germany). In some cases, the 3D images sets were processed by blind deconvolution using AutoQuant X (vr. 2.1.3; Media Cybernetics Inc. MD, USA). 3D image stacks were examined using Volocity (v. 4.2, Improvision, USA) to produce single scanned (XY) images, computed single section in XZ, YZ, at intermediate orientations, maximum intensity projections (MIPs) in the three cardinal planes, and 3D rendered images. The data were analyzed for the topographical distribution of platelets in relation to staining for collagen-IV (basal lamina) and RECA-1 (endothelium), and for the configuration of RECA-1 staining within vessels. We also prepared volumetric animations of 24 hr specimens stained for collagen IV, EBA and platelets for better visualization of the arrangement of the three antigens with respect to each other.

Zymography and immunostaining combination

Four brain regions (basal and frontal cerebral cortex, striatum, and hippocampus) separated into right and left hemispheres were analyzed by fluorescence microscopy (Axiophot; Carl Zeiss, USA). Quantitative analysis was performed on immunostained zymographs using IPLab software (Scanalytic Inc, vr 3.63; USA). Fluorescence images (2-3 fields per region and hemisphere) were recorded under constant illumination and exposure settings using a 20x objective (field area= 8 ×104 μm2) and studied for the number of vascular profiles positive for 1. collagen IV only, 2. collagen IV and collagenase without platelets, and 3. collagen IV and collagenase with platelets.

Results

To characterize brain microvessels, we immunostained 8 or 20 μm thick cryostat sections with combinations of antibodies against collagen IV, a major constituent of brain vascular basal lamina; RECA-1, a marker of endothelial cells; and whole platelets. The primary antibodies were detected with species-specific, non-cross reactive secondary antibodies. High-resolution three dimensional image sets were collected by confocal microscopy followed in some cases by deconvolution for enhanced visualization.

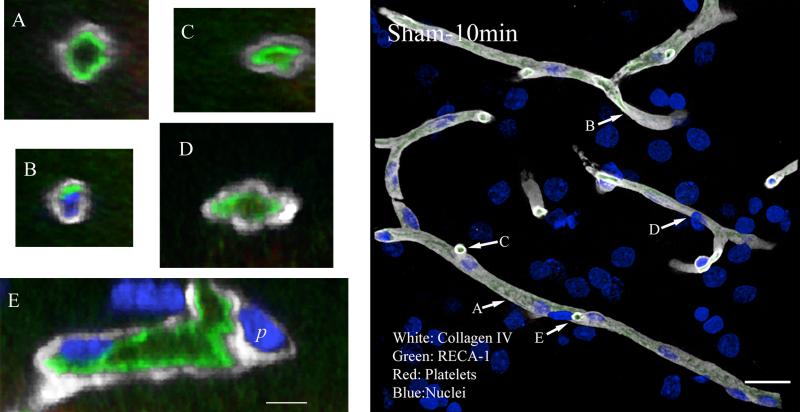

In sham operated animals, the microvasculature was clearly delineated by collagen IV and by RECA-1 immunostaining. At low magnification and in high-magnification projected images, vessels appeared as bands which branched and anastomosed in patterns consistent with section thickness. Close examination showed that immunofluorescence for each of those two antigens was rarely interrupted along the length of profiles (Figure-1 composite). We examined vessels in cross-section using images constructed from the 3D image sets. Most such sections showed, as expected, the vascular lumen surrounded by a ring of endothelium (RECA-1 immunofluorescence) and, outside of that, the basal lamina (Figures 1A). Rarely, small aggregates of platelets were visible within the lumen (Figure 1D) of sham specimens. In addition, nuclei of both endothelial cells and pericytes could be identified when specimens were counterstained for DNA (DAPI; Figure 1 B and E).

Figure 1. Collagen IV, RECA-1 and platelet immunostaining of parenchyma vasculature.

Representative image from a sham animal sacrificed 10 minutes after the surgery. Vessels appear as smooth continuous tubes. Collagen IV and RECA-1 immunostaining are continuous along the length and circumference of the vessels. In cross section, most vessel lumena appear open (A, C, D and E), but some are compressed or entirely obscure (B). This apparent collapse of the vessel is likely a postmortem artifact. Scale in composite image is 20 μm; in magnified images, 5 μm.

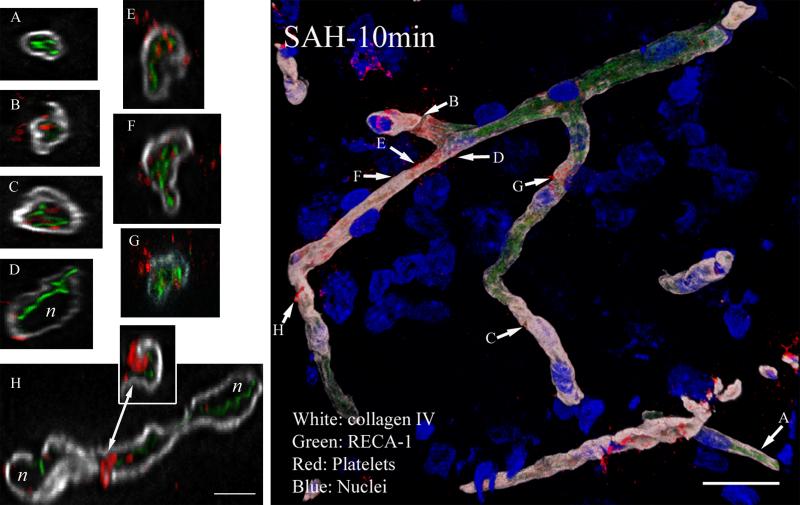

Ten minutes after SAH, partial destruction of basal lamina, substantial fragmentation of RECA-1 staining, local collapse of vascular lumens, and escape of platelets into the brain parenchyma was evident (Figure 2 composite). The number of collagen IV profiles positive for platelets was compared with time-matched sham cohorts. Approximately 42% of the collagen IV positive profiles contained luminal platelets aggregates after SAH, as compared to 1% in time-matched shams (data not shown). Low magnification and projected views of collagen IV staining showed prominent gaps in vessels, suggesting extensive compromise of the basal lamina, and high resolution images showed regions apparently completely devoid of collagen IV immunofluorescence (Figures 2 B, F and H). Platelet aggregates were often visible in these collagen IV-depleted segments (Figure 2 F and H). In other regions, vessels were surrounded by continuous rings of collagen IV, as in control specimens (Figures-2 A and D); however, in many of these cases RECA-1 staining was fragmented, often displaced into the lumen of the vessel, and sometimes intermingled with platelet aggregates (figure 2 F-G). In many profiles aggregates were interposed between endothelium (RECA-1) and basal lamina (Figure-2 C). Where endothelial structure is disrupted, some aggregates appeared in direct contact with the basal lamina (Figure 2 B and E). Some sections showed platelet aggregates entirely outside the vessels, within the parenchyma (Figure 2B, D, E-G).

Figure 2. Collagen IV, endothelium and platelet aggregate immunostaining 10 minutes after SAH.

Representative image from an animal sacrificed 10 min after SAH is shown. High magnification analysis of selected vascular segments revealed fragmented RECA-1 immunostaining and collapsed vessel lumen (A, B, E, F and H). Collagen IV staining is irregular and missing along a vessel (F, H). In many vessels, platelet aggregates have passed endothelium and lie next to the collagen layer (A and C), and in some cases lie outside basal lamina. (D) Many vessels show gaps in collagen IV staining, from which platelets are entering the brain parenchyma (A, E, F, G and H). These vessels appear to have lost their integrity and shape. The letter represents nuclei not shown for clarity. Scale: composite image, 20 μm; magnified images, 5 μm.

Platelet aggregates in direct contact with basal lamina were often intermingled with RECA-1 fragments within the vessel, or were within parenchyma adjacent to gaps in the basal lamina (Figure-2 F-H). Even in sections where basal lamina appears intact, platelets could be seen integrated within, or lying across the thickness of the basal lamina (Figure2; D, E and H). The collapsed/interrupted endothelium with intra- and extra-luminal platelet aggregates might explain why at 10 minutes after SAH, CPP had recovered to 85% of the baseline while CBF recovery was only 27%.

The destruction of structure of parenchymal vessels had progressed by 3 hours after SAH. The number of collagen IV-stained vessel profiles was substantially reduced, as reported previously. Endothelial RECA-1 staining was increasingly discontinuous and fragmented. Platelet aggregates were still present in vessels. Approximately 37 % of the collagen IV-positive vessel profiles contained luminal platelets aggregates after SAH as compared to 3% in time-matched controls. Some vessel segments were devoid of both collagen IV and RECA-1 staining, so the vessel continuation could only be identified by extension of platelet staining connecting the two vascular profiles appeared at this time (shown in Movie-2 for 24 hours after SAH; see below).

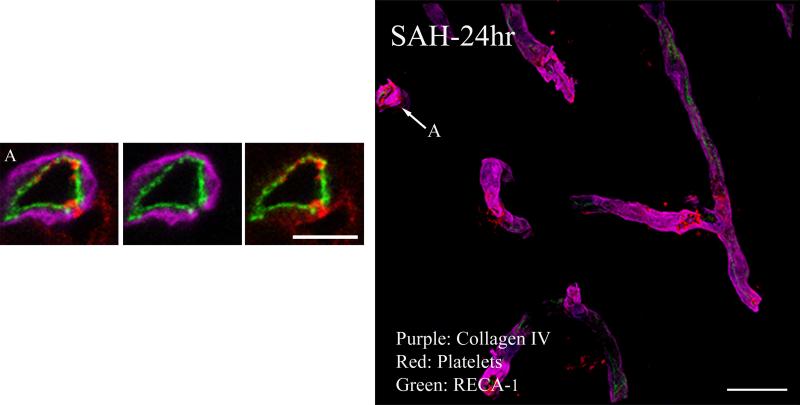

At 24 hours after SAH, vessel structure was improved. RECA-1 and collagen IV immunofluorescence appeared largely continuous along vessels, suggesting that both endothelium and basal lamina were being restored (Figure-3 composite). These images verify the continuity of endothelium and basal lamina, but reveal frequent small holes that contain platelet aggregates (Figure-3 arrows). In addition, frequent extra-vascular platelet was seen next to the holes, indicating escape into brain parenchyma (Figure-3A). Platelet-filled holes can be clearly identified in 3D movies of cerebral vessels at 24 hours after SAH (Movie-1; available on web only). In addition, some vascular areas were negative for collagen IV and platelets but positive for endothelial markers; and others, lacking both collagen IV and RECA-1 staining, could only be identified by extension of platelet staining connecting the two vascular profiles (Movie-2; available on web only).

Figure 3. Collagen IV, endothelium and platelet aggregate immunostaining 24 hours after SAH.

Representative image from an animal sacrificed at 24 hours after SAH is shown. Clear holes on the vessel wall cutting though the collagen and endothelium lining and exposing the luminal platelet aggregates can be seen (arrows). High magnification analysis of a selected vascular segment shows relatively continuous endothelium and collagen IV lining (compared to 10 min SAH animals), but note gap where platelets are entering the brain parenchyma (A). Scale: composite image, 20 μm; magnified images, 5 μm

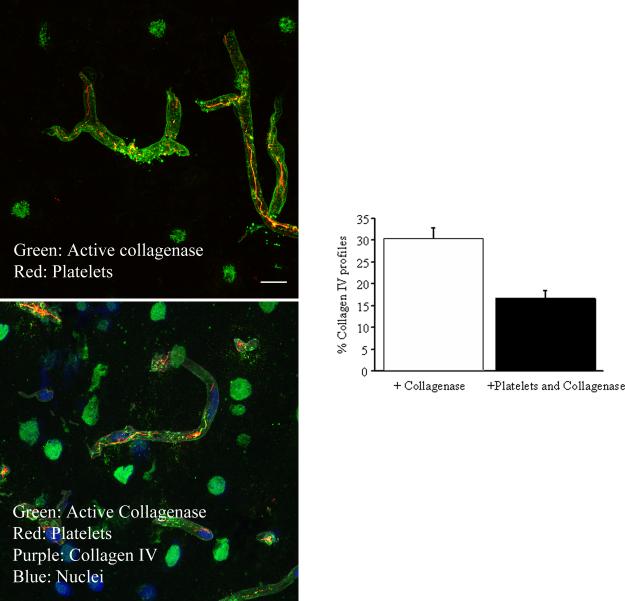

Platelet aggregates and vascular collagenase activity

These experiments, performed at 3 hours post-hemorrhage, examined if vascular collagenase activity colocalizes with intraluminal platelet aggregates, making their extra-vascular escape possible. Collagenase activity was detected by treating sections with DQ (which yields a fluorescent product when degraded by active collagenase), and collagen IV and platelets were visualized by immunofluorescence (Figure 4A). Previously, we found peak vascular collagenase activity at 3h after SAH. In the present study, many collagen IV immunostained profiles were positive for collagenase activity, indicating ongoing breakdown of vascular basal lamina at this time. Almost half of those collagenase-positive profiles contained platelet aggregates as well (Figure 4B). These data support collagenase activity as a mechanism underlying the escape of vascular platelets into the brain parenchyma via collagen-depleted sites.

Figure 4. Collagenase activity colocalizes with vascular platelet aggregates after SAH.

A. Representative zymographs from animals sacrificed 3 hours after SAH, immunostained for collagen IV and platelet aggregates. Note the presence of platelet aggregates in vessels positive for collagenase activity. B. Histogram shows the percentage of collagen IV-immunostained parenchymal vessels positive for collagenase activity and platelets + collagenase activity at 3 hours after SAH. n=3-4

Discussion

We previously showed that platelet aggregates are present in the lumen of parenchymal microvessels as early as 10 minutes after SAH (Sehba et al., 2005) and that they continue to be present in the recovering brain for at least 24 hours ((Sehba et al., 2005); see also (Ishikawa et al., 2009). The present study investigated the distribution and fate of intra- and extra-luminal platelet aggregates at high resolution during the first 24 hours after SAH. Remarkably, we found structural compromise of microvessels and platelet escape into parenchyma as early as 10 minutes after SAH. The data suggest that platelets escape individually, apparently by passing across or around endothelium and through platelet-sized holes in basal lamina. In addition, platelets (and surely other blood elements not visualized here) can escape through larger interruptions in endothelium and basal lamina which give rise to microhemorrhages and may represent an early stage of hemorrhagic transformation. These findings supporting a novel mechanism of early brain injury after SAH open a new venue for research and for therapeutic intervention.

The escape of platelets and development of microhemorrhages occur in the context of other changes evident early after SAH, including interruption of endothelial lining (Sehba et al., 2007a, Sehba et al., 2007b), and basal lamina (Sehba and Bederson, 2006, Scholler et al., 2007, Ishikawa et al., 2009), increased matrix metalloproteinase-9levels (Sehba et al., 2004), and induction of collagenase activity (Sehba et al., 2004, Sehba et al., 2007a). The interruption in endothelial lining inferred in this study from fragmented RECA-1 staining (Figure 2) echoes similar interrupted immunostaining, reported earlier, of two other endothelial cell antigens after SAH: endothelial barrier antigen (EBA) and endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) (Sehba et al., 2007a, Sehba et al., 2007b). EBA is present in endothelium of blood vessels in the rat CNS, where the blood-brain barrier is present (Sternberger and Sternberger, 1987), and in contexts other than SAH, EBA is a marker of rat blood-brain barrier integrity. Thus we interpret the fragmentation of endothelium as revealed by antibodies to these three antigens not as antigen redistribution, but instead a physical rearrangement of endothelial cells, which may underlie compromised endothelium function after SAH (Nakagomi et al., 1987, Hongo et al., 1988, Hatake et al., 1992, Park et al., 2001, Pennings et al., 2004).

The disruption and fragmentation of the microvessel endothelial lining visible 10 minutes after hemorrhage likely leads to increased flow resistance and could contribute to the early reduction of CBF, which persists as the “no-reflow” phenomenon (Ames et al., 1968) even after recovery of CPP. In addition, this fragmentation may promote the aggregation of platelets and their adhesion to vessel walls (Said et al., 1993, Rosenblum, 1997). Interestingly, an analogous penetration of platelets into the endothelial wall of parenchymal vessels has been reported in another cortical SAH model (Doczi et al., 1986).

The disappearance of microvascular collagen IV immunoreactivity after SAH was observed previously (Sehba et al., 2005, Scholler et al., 2007). The underlying mechanism involves vascular collagenases activated early after SAH (Sehba et al., 2005, Yan et al., 2008). Two major collagenases (metalloproteinases-2 and 9) involved in digestion of vascular collagen are present in platelets and are released by platelets upon activation (Sawicki et al., 1997); the presence of platelets in majority of the holes in the collagen IV layer suggests local degradation by collagenases released by those platelets.

On a larger scale, we have found that almost half of the microvascular segments with increased collagenase activity contain intraluminal platelet aggregates at the time of sacrifice. Since some aggregates very likely are moved by perfusion along vessels, those regions of collagenase activity lacking platelet aggregates at 10 minutes may have contained aggregates earlier. We suggest that activated platelets and platelet aggregates are a major source of collagenase, through direct release and/or by inducing the release of activated collagenase by other cellular elements such as neutrophils or endothelial cells.

After SAH, we suggest, activated degranulating platelets in parenchymal vessels produce disruption and denudation of activated endothelial cells, making these sites attractive to passing emboli and thereby promoting further aggregation (Said et al., 1993, Rosenblum, 1997). Indeed, we and others have found a progressive increase in the number of vascular platelet aggregates during the first few hours after SAH (Sehba et al., 2005, Ishikawa et al., 2009). If collagenase release is prerequisite for parenchymal entry of platelets, then most escaped platelets will be degranulated, at least at the earliest times after SAH. Indeed, degranulated platelets are observed by electron microscopy in brain parenchyma 3 hours after SAH (Doczi et al., 1986). It might be expected that where disruption of the endothelium and basal lamina is established, granulated platelets also will spill into the brain parenchyma. Other components of blood and plasma proteins may follow platelets to the brain parenchyma via the holes in the collagen lining, creating minute hemorrhages. The presence of platelets in the brain parenchyma could promote inflammation and neurotoxicity. Indeed, exposure of organotypic spinal cord cultures to activated platelets or platelet secretions resulted in a 60% reduction of acetylcholinesterase-positive neurons (Joseph et al., 1992). Our results indicate that similar neurotoxic effects may occur in SAH.

Our findings that the collagen lining of parenchymal vessel is destroyed and platelets enter the brain parenchyma may indicate hemorrhagic transformation of brain after SAH. Hemorrhagic transformation, a major drawback of thrombolysis-induced recanalization in ischemic stroke, can lead to clinically silent hemorrhagic infarction or to disastrous parenchymal hemorrhage (Molina, 2006). Mechanisms responsible for hemorrhagic transformation include plasmin-generated laminin degradation, activation of matrix metalloproteinases, and transmigration of leukocytes through vessel walls (Hamann et al., 1996). If platelet entry in the brain parenchyma after SAH reflects hemorrhagic transformation of the brain, the mechanism involved appears to differ from the conventional over-generation of plasmin upon thrombolytic treatment. Our results suggest a possible mechanism underlying the hemorrhagic transformation of parenchymal vessels in humans after SAH.

In summary, we have found that intraluminal platelet aggregates are present at 10 minutes after SAH and are associated with vessel wall injury, including damage to endothelium and the microvascular basal lamina. Even at 10 minutes, platelets are present in the parenchyma, having escaped from microvessels through minute holes in basal lamina and through larger breaches of vessel walls. Escaped platelets may activate additional inflammatory mechanisms and may represent an early initiator or aggravator of cerebral injury after SAH

Supplementary Material

Movies: Changes in parenchymal vasculature 24 hours after SAH. Each movie shows a single parenchymal vessel immunostained for EBA (blue; endothelium barrier antigen; a rat BBB integrity marker), collagen IV (purple) and platelets (green).

Movie-1: Note platelet aggregates in the vessel seen through the holes on the vessel wall created by the loss of collagen and endothelium. Also, note areas on vascular segments where EBA is restored but collagen is not.

Movie-2: Note the vascular areas devoid of both collagen IV and EBA staining; the vessel continuation could only be identified by extension of platelet staining connecting the two vascular profiles.

A comprehensive list of abbreviations

- SAH

subarachnoid hemorrhage

- ICP

intracranial pressure

- CBF

cerebral blood flow

- BP

blood pressure

- CPP

cerebral perfusion pressure

- ICA

internal carotid artery

- MMP-9

matrix metalloproteinase-9

- RECA-1

rat endothelial cell antigen-1

- EBA

endothelial barrier antigen

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Victor Friedrich, Department of Neuroscience Mount Sinai School of Medicine, New York, NY 1 Gustave L. Levy Place New York, NY 10029 212 241 4004 Victor.Friedrich@mssm.edu.

Rowena Flores, Department of Neurosurgery Mount Sinai School of Medicine, New York, NY 1 Gustave L. Levy Place New York, NY 10029 212 241 5605 Rowena.flores@mssm.edu.

Artur Muller, Department of Neurosurgery Mount Sinai School of Medicine, New York, NY 1 Gustave L. Levy Place New York, NY 10029 212 241 5605 Artur.Muller@mssm.edu.

Fatima A. Sehba, Departments of Neurosurgery and Neurosciences Mount Sinai School of Medicine, New York, NY 1 Gustave L. Levy Place New York, NY 10029 Phone: 212 241 6504 Fax: 212 241 0697 fatima.sehba@mssm.edu

References

- Ames Ad, Wright RL, Kowada M, Thurston JM, Majno G. Cerebral ischemia. II. The no-reflow phenomenon. Am J Pathol. 1968;52:437–453. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bederson JB, Connolly ES, Jr., Batjer HH, Dacey RG, Dion JE, Diringer MN, Duldner JE, Jr., Harbaugh RE, Patel AB, Rosenwasser RH. Guidelines for the management of aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage: a statement for healthcare professionals from a special writing group of the Stroke Council, American Heart Association. Stroke. 2009;40:994–1025. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.191395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bederson JB, Germano IM, Guarino L. Cortical blood flow and cerebral perfusion pressure in a new noncraniotomy model of subarachnoid hemorrhage in the rat. Stroke. 1995;26:1086–1091. doi: 10.1161/01.str.26.6.1086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bederson JB, Levy AL, Ding WH, Kahn R, DiPerna CA, Jenkins ALr, Vallabhajosyula P. Acute vasoconstriction after subarachnoid hemorrhage. Neurosurgery. 1998;42:352–360. doi: 10.1097/00006123-199802000-00091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broderick JP, Brott TG, Duldner JE, Tomsick T, Leach A. Initial and recurrent bleeding are the major causes of death following subarachnoid hemorrhage. Stroke. 1994;25:1342–1347. doi: 10.1161/01.str.25.7.1342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diringer MN. Management of aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. Crit Care Med. 2009;37:432–440. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e318195865a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doczi T, Joo F, Adam G, Bozoky B, Szerdahelyi P. Blood-brain barrier damage during the acute stage of subarachnoid hemorrhage, as exemplified by a new animal model. Neurosurgery. 1986;18:733–739. doi: 10.1227/00006123-198606000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grosset DG, Straiton J, McDonald I, Bullock R. Angiographic and Doppler diagnosis of cerebral artery vasospasm following subarachnoid haemorrhage. Br J Neurosurg. 1993;7:291–298. doi: 10.3109/02688699309023812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamann GF, Okada Y, del Zoppo GJ. Hemorrhagic transformation and microvascular integrity during focal cerebral ischemia/reperfusion. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1996;16:1373–1378. doi: 10.1097/00004647-199611000-00036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatake K, Wakabayashi I, Kakishita E, Hishida S. Impairment of endothelium-dependent relaxation in human basilar artery after subarachnoid hemorrhage. Stroke. 1992;23:1111–1116. doi: 10.1161/01.str.23.8.1111. discussion 1116-1117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hongo K, Kassell NF, Nakagomi T, Sasaki T, Tsukahara T, Ogawa H, Vollmer DG, Lehman RM. Subarachnoid hemorrhage inhibition of endothelium-derived relaxing factor in rabbit basilar artery. J Neurosurg. 1988;69:247–253. doi: 10.3171/jns.1988.69.2.0247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutchinson PJ, O'Connell MT, Al-Rawi PG, Kett-White CR, Gupta AK, Maskell LB, Pickard JD, Kirkpatrick PJ. Increases in GABA concentrations during cerebral ischaemia: a microdialysis study of extracellular amino acids. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2002;72:99–105. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.72.1.99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishikawa M, Kusaka G, Yamaguchi N, Sekizuka E, Nakadate H, Minamitani H, Shinoda S, Watanabe E. Platelet and leukocyte adhesion in the microvasculature at the cerebral surface immediately after subarachnoid hemorrhage. Neurosurgery. 2009;64:546–553. doi: 10.1227/01.NEU.0000337579.05110.F4. discussion 553-544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joseph R, Tsering C, Grunfeld S, Welch KM. Further studies on platelet-mediated neurotoxicity. Brain Res. 1992;577:268–275. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(92)90283-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamiya K, Kuyama H, Symon L. An experimental study of the acute stage of subarachnoid hemorrhage. J Neurosurg. 1983;59:917–924. doi: 10.3171/jns.1983.59.6.0917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence ES, Coshall C, Dundas R, Stewart J, Rudd AG, Howard R, Wolfe CD. Estimates of the prevalence of acute stroke impairments and disability in a multiethnic population. Stroke. 2001;32:1279–1284. doi: 10.1161/01.str.32.6.1279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKhann GM, 2nd, Le Roux PD. Perioperative and intensive care unit care of patients with aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. Neurosurg Clin N Am. 1998;9:595–613. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molina CA. Hemorrhagic transformation: a foe that could be a friend? Int J Stroke. 2006;1:226–227. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-4949.2006.00063.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakagomi T, Kassell NF, Sasaki T, Fujiwara S, Lehman RM, Johshita H, Nazar GB, Torner JC. Effect of subarachnoid hemorrhage on endothelium-dependent vasodilation. J Neurosurg. 1987;66:915–923. doi: 10.3171/jns.1987.66.6.0915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park KW, Metais C, Dai HB, Comunale ME, Sellke FW. Microvascular endothelial dysfunction and its mechanism in a rat model of subarachnoid hemorrhage. Anesth Analg. 2001;92:990–996. doi: 10.1097/00000539-200104000-00035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paxinos G, Watson C. The Rat Brain in Stereotaxic Coordinates. Academic Press Inc.; San Diego, California: 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Pennings FA, Bouma GJ, Ince C. Direct observation of the human cerebral microcirculation during aneurysm surgery reveals increased arteriolar contractility. Stroke. 2004;35:1284–1288. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000126039.91400.cb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasmussen G, Hauerberg J, Waldemar G, Gjerris F, Juhler M. Cerebral blood flow autoregulation in experimental subarachnoid haemorrhage in rat. Acta Neurochir. 1992;119:128–133. doi: 10.1007/BF01541796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenblum WI. Platelet adhesion and aggregation without endothelial denudation or exposure of basal lamina and/or collagen. J Vasc Res. 1997;34:409–417. doi: 10.1159/000159251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Said S, Rosenblum WI, Povlishock JT, Nelson GH. Correlations between morphological changes in platelet aggregates and underlying endothelial damage in cerebral microcirculation of mice. Stroke. 1993;24:1968–1976. doi: 10.1161/01.str.24.12.1968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarrafzadeh A, Haux D, Sakowitz O, Benndorf G, Herzog H, Kuechler I, Unterberg A. Acute focal neurological deficits in aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage: relation of clinical course, CT findings, and metabolite abnormalities monitored with bedside microdialysis. Stroke. 2003;34:1382–1388. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000074036.97859.02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawicki G, Salas E, Murat J, Miszta-Lane H, Radomski MW. Release of gelatinase A during platelet activation mediates aggregation. Nature. 1997;386:616–619. doi: 10.1038/386616a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schievink WI, Wijdicks EF, Parisi JE, Piepgras DG, Whisnant JP. Sudden death from aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. Neurology. 1995;45:871–874. doi: 10.1212/wnl.45.5.871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scholler K, Trinkl A, Klopotowski M, Thal SC, Plesnila N, Trabold R, Hamann GF, Schmid-Elsaesser R, Zausinger S. Characterization of microvascular basal lamina damage and blood-brain barrier dysfunction following subarachnoid hemorrhage in rats. Brain Res. 2007;1142:237–246. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2007.01.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz AY, Masago A, Sehba FA, Bederson JB. Experimental models of subarachnoid hemorrhage in the rat: A refinement of the endovascular filament model. J Neurosci Methods. 2000;96:161–167. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0270(00)00156-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sehba FA, Bederson JB. Mechanisms of Acute Brain injury after Subarachnoid Hemorrhage. Neurol Res. 2006;28:381–398. doi: 10.1179/016164106X114991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sehba FA, Flores R, Muller A, Friedrich V, Bederson JB. Early decrease in cerebral endothelial nitric oxide synthase occurs after Subarachnoid Hemorrhage. Annual Stroke conference. 2007a:527. [Google Scholar]

- Sehba FA, Makonnen G, Friedrich V, Bederson JB. Acute cerebral vascular injury occurs after subarachnoid hemorrhage and can be prevented by administration of a Nitric Oxide donor. J Neurosurg. 2007b;106:321–329. doi: 10.3171/jns.2007.106.2.321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sehba FA, Mostafa G, Knopman J, Friedrich V, Jr., Bederson JB. Acute alterations in Microvascular basal lamina after Subarachnoid Hemorrhage. J Neurosurg. 2004;101:633–640. doi: 10.3171/jns.2004.101.4.0633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sehba FA, Mustafa G, Friedrich V, Bederson JB. Acute microvascular platelet aggregation after Subarachnoid hemorrhage. J Neurosurg. 2005;102:1094–1100. doi: 10.3171/jns.2005.102.6.1094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staub F, Graf R, Gabel P, Kochling M, Klug N, Heiss WD. Multiple interstitial substances measured by microdialysis in patients with subarachnoid hemorrhage. Neurosurgery. 2000;47:1106–1115. doi: 10.1097/00006123-200011000-00016. discussion 1115-1106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sternberger NH, Sternberger LA. Blood-brain barrier protein recognized by monoclonal antibody. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1987;84:8169–8173. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.22.8169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Travis MA, Hall ED. The effects of chronic two-fold dietary vitamin E supplementation on subarachnoid hemorrhage-induced brain hypoperfusion. Brain Res. 1987;418:366–370. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(87)90105-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weir B, Grace M, Hansen J, Rothberg C. Time course of vasospasm in man. J Neurosurg. 1978;48:173–178. doi: 10.3171/jns.1978.48.2.0173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weyrich AS, Schwertz H, Kraiss LW, Zimmerman GA. Protein synthesis by platelets: historical and new perspectives. J Thromb Haemost. 2009;7:241–246. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2008.03211.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan J, Chen C, Hu Q, Yang X, Lei J, Yang L, Wang K, Qin L, Huang H, Zhou C. The role of p53 in brain edema after 24 h of experimental subarachnoid hemorrhage in a rat model. Exp Neurol. 2008;214:37–46. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2008.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Movies: Changes in parenchymal vasculature 24 hours after SAH. Each movie shows a single parenchymal vessel immunostained for EBA (blue; endothelium barrier antigen; a rat BBB integrity marker), collagen IV (purple) and platelets (green).

Movie-1: Note platelet aggregates in the vessel seen through the holes on the vessel wall created by the loss of collagen and endothelium. Also, note areas on vascular segments where EBA is restored but collagen is not.

Movie-2: Note the vascular areas devoid of both collagen IV and EBA staining; the vessel continuation could only be identified by extension of platelet staining connecting the two vascular profiles.