Abstract

Transdominant inhibition of integrins or integrin-integrin crosstalk is an important regulator of integrin ligand binding and subsequent signaling events that control a variety of cell functions in many tissues. Here we discuss examples of integrin crosstalk and detail our current understanding of the molecular mechanisms that are involved in this receptor phenomenon. The cytoskeleton associated protein talin is a key regulator of integrin crosstalk. We describe how the interaction of talin and the cytoplasmic tail of β integrin is controlled and how competitive inhibitors of this binding play a role in integrin crosstalk. We conclude with a discussion of how integrin crosstalk impacts the interpretation of integrin inhibitor and knockdown studies in both the laboratory and clinical setting.

Keywords: Matrix adhesion, receptors, cytoskeleton, signaling, adaptor proteins, phosphorylation

1. Introduction

The term integrin refers to a member of a family of matrix and cell-cell adhesion receptor proteins that exists at the cell surface as a dimer composed of an α and β subunit. In mammals, 18 α and 8 β subunits have been identified[1, 2]. The various combinations of αs and βs exhibit ligand specificity and interact with various matrix molecules including fibronectin, collagens, laminins, proteoglycans as well as intercellular adhesion molecules[2, 3]. In addition to their role in adhesion, integrins are critical regulators of complex cellular processes such as adhesion, migration and proliferation. Receptor clustering occurs as a consequence of integrin ligand binding and this, in turn, results in recruitment of cytoskeletal and signaling adaptor proteins to integrin cytoplasmic tails[1, 4].

Integrin subunits were initially identified and characterized by the use of antibodies generated against cell surface proteins. Moreover, some of the integrin antibodies that have been prepared over the years have been very useful in dissecting integrin functions since they have the ability to impede cell adhesion to ligands or other cells. Therein lies a conundrum. Most cells are now known to express more than one integrin heterodimer, some of which share ligands[2]. Why does inhibition of one integrin subunit or heterodimer in many instances also perturb ligand binding of a second and distinct integrin? An accepted explanation for this phenomenon is a process involving transdominant inhibition of integrin function, the topic of this review[5].

Transdominant inhibition of integrin function, or for convenience we will use the designation integrin crosstalk, is a mechanism in which one integrin regulates the activation state of a different integrin in the same cell. It is believed to play a central role in regulating integrin ligand binding in a number of in vivo situations[5, 6]. In addition, the ability of integrin subunit-specific antibody antagonists to inhibit multiple integrins likely is both a bonus and potential detriment in their use in the treatment of a variety of diseases. Several mechanisms have been reported to mediate integrin crosstalk, with the cytoskeleton associated protein talin featuring prominently as a key regulator in most. Such mechanisms generally involve the regulation of the binding of intracellular proteins to integrin cytoplasmic tails and/or differential phosphorylation of residues within the integrin tail. In this review, we will not consider integrin crosstalk with growth factor receptors or other non-integrin adhesion receptors. We focus on integrin-integrin crosstalk and discuss a limited number of examples of tissue/cell systems in which crosstalk has been reported. We will detail what we know of the mechanism(s) underlying crosstalk and review the physiological and medical significance of the phenomenon. To begin, we will first briefly discuss integrin activation since the ability to regulate such activation is the molecular basis of crosstalk.

2. Integrin Activation

Integrins exist in an unfolded, active and folded, inactive conformation[3, 7-9]. In the inactive state integrins do not bind ligand and fail to signal[3, 7]. Integrins can be activated “outside-in”, following interaction with extracellular matrix ligands, or by “inside-out” signaling in which intracellular proteins bind to and induce separation of the cytoplasmic tails of integrins[1, 7, 9-13]. Activation of integrins in which the cytoplasmic tails become straightened increases ligand affinity and induces the formation of a signaling complex in the cytoplasm[3, 7, 9, 11].

3. Examples of Integrin Crosstalk

3.1 Integrin Crosstalk in the Immune System

In the immune system, ligand binding of αIIβ3 integrin in platelets inhibits α2β1 integrin mediated adhesion to collagen[14]. Failure of such crosstalk may be the cause of the genetic disorder, Glanzmann's thrombastenia, a disease characterized by defective platelet aggregation and severe bleeding[14, 15]. In patients afflicted with the disease, serine residue 752 in the cytoplasmic domain of the β3 integrin subunit is mutated to proline[16]. This mutation prevents activation of platelet αIIβ3 integrin by inside-out signaling, resulting in a reduction in platelet binding to plasma proteins and, consequently, impedes platelet aggregation[15]. In addition, the same mutation inhibits the ability of αIIβ3 integrin to prevent ligand binding of α2β1 integrin and, thus, promotes platelet adherence to vessel walls[14].

Integrin crosstalk also plays a role in the regulation of lymphocyte extravasation from the circulation into sites of inflammation during an immune response[17]. In human lymphocytes, αLβ2 (LFA-1) integrin binding to ICAM-1 decreases adhesion of α4β1 integrin to VCAM-1 and fibronectin, facilitating detachment of α4β1 integrin from the apical surface of endothelial cells[17]. Moreover, decreased α4β1 integrin activity leads to an enhancement of α5β1 integrin mediated migration on fibronectin, a process that promotes transmigration through an endothelium[17].

3.2 Integrin Crosstalk in Angiogenesis

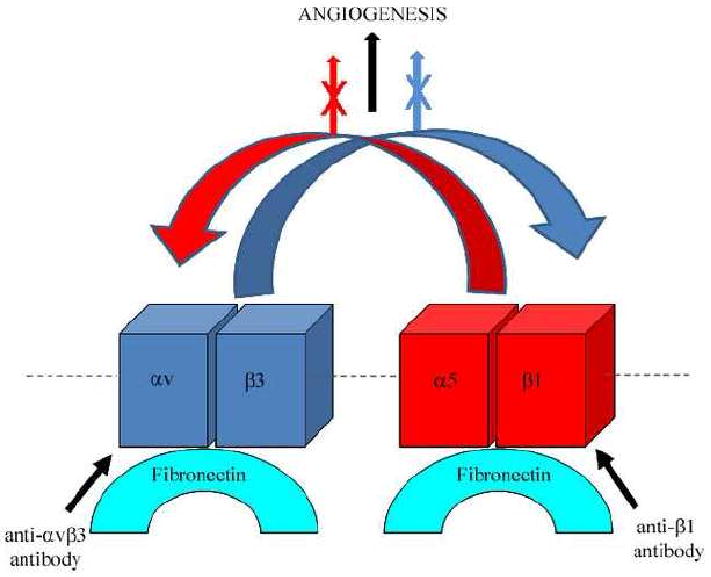

In an adult, angiogenesis is the formation of new blood vessels from a pre-existing vasculature[18]. It contributes to tissue remodeling and wound healing. Pathological angiogenesis occurs in, but is not limited to, psoriasis and age-related macula degeneration. In the latter, aberrant blood vessel formation results in tissue damage and tissue failure. Pathological angiogenesis also plays a role in cancer where it is required for the development of tumors larger than a few millimeters in size[19]. With regard to integrins, αvβ3 and α5β1 integrin are now recognized as key players in angiogenesis[20-25]. Not only do the levels of αvβ3 and α5β1 integrin protein increase in angiogenic endothelial cells, but also inhibiting αvβ3 or α5β1 integrin function individually with antibodies or small compounds results in perturbation of angiogenesis[24, 25](Fig. 1). These results at first glance are somewhat unexpected. One might imagine that inhibition of αvβ3 integrin function would have little effect on angiogenesis since α5β1 integrin should compensate and vice versa, particularly since these two integrin share a common matrix ligand (fibronectin). It was even more of a surprise that loss of αvβ3 integrin expression in the mouse did not affect pathological angiogenesis[26], despite the anti-angiogenic ability of small molecule αvβ3 integrin inhibitors and antibody antagonists [26]. Moreover, it is intriguing to note that in vivo, if expression of αvβ3 integrin is lost, the activity of β1 subunit-containing integrins appears enhanced, so much so, that pathological angiogenesis is promoted[26]. Rather, it is now clear that there is a complex crosstalk between β1 and β3 subunit containing integrins during angiogenesis and in various in vitro and in vivo models. Numerous examples are detailed in the literature. For example, in our own studies, we have demonstrated that in vitro in endothelial cells crosstalk between β1 and β3 is bidirectional such that when αvβ3 integrin is blocked using antibodies there is a concomitant inhibition in ligand binding of α3β1 and α6β1 integrin[27]. In the same cells, a combination of antibodies that functionally inhibit α3 and α6 integrin block ligand binding of αvβ3 integrin[27]. Studies by Ly and colleagues reveal that expression of α5β1 integrin in CHO cells inhibits αvβ3 mediated adhesion and migration on fibrinogen[28]. Both adhesion and migration require a high affinity state of αvβ3 integrin for ligand. In the absence of α5β1 integrin, αvβ3 integrin is present in a high affinity state in CHO cells. However, expression of α5β1 integrin in CHO cells inhibits αvβ3 mediated cell adhesion and migration[28]. A constitutively active β3 integrin which is believed to switch β3 integrin to a high affinity state is resistant to the inhibitory effect of α5β1 integrin[28]. Some other examples of the crosstalk between integrins involved in angiogenesis are described below where we discuss molecular mechanisms that regulate this phenomenon.

Fig. 1.

This diagram represents a simple scheme of transdominant inhibition of integrins expressed by endothelial cells. In the example shown α5β1 and αvβ3 integrin both bind to fibronectin ligand and, upon ligand activation, they support signaling processes leading to angiogenesis (black arrow). However, upon antibody inhibition of β1 integrin, not only is α5β1integrin-ligand interaction perturbed but also αvβ3 integrin binding to ligand is impeded (red curved arrow), resulting in a block in angiogenesis (X through red arrow). Likewise, upon antibody inhibition of αvβ3 integrin, both αvβ3 and α5β1 integrin-ligand binding (curved blue arrow) are perturbed as is angiogenesis (X through blue arrow).

3.3 Integrin Crosstalk in Keratinocytes

Integrin crosstalk is also observed, at least in vitro, during the adhesion and the migration of skin cells (keratinocytes). Keratinocytes express multiple integrins, two of which, α6β4 and α3β1 integrin, bind laminin-332 in the extracellular matrix[29, 30]. When keratinocytes are plated in vitro onto laminin-332 they initially bind via α3β1 integrin, as demonstrated by antibody blocking studies[30]. However, very rapidly after plating, α6β4 integrin displaces α3β1 integrin from their common matrix ligand and, at least in some instances, induces stable adhesion to substrate[30]. This displacement can be inhibited by antibodies that block the function of α6β4 integrin (Fig. 2). Moreover, there is evidence that α6β4 integrin can inhibit haptotactic migration driven by α3β1 integrin, resulting in stable adhesion[31]. This has led to the proposal that α6β4 integrin negatively regulates activation of α3β1 integrin. However, during wound healing in vivo, the functions and interactions of α6β4 and α3β1 integrin may be even more complex since data also exist indicating that α6β4 integrin supports signaling pathways that drive migration, while α3β1 integrin has recently reported to inhibit motility of keratinocytes[32].

Fig. 2.

Human keratinocytes (SCC12 cells) were plated onto the laminin-332-rich matrix of rat bladder 804G cells in the absence (A-C, G-I) or presence of GoH3, a function-inhibiting α6 integrin antibody (D-F, J-L). At 2 hours after plating, cells were prepared for double label immunofluorescence using a combination of antibodies against either β4 integrin and laminin-332 or α3β1 integrin and laminin-332 as indicated. Cells were viewed by confocal microscopy with the focal plane being as close as possible to the cell-substratum interface. Overlays of the sets of images are shown in C, F, I, and L. Note that the laminin-332 antibodies in B, E, H, and K generate a “Swiss cheese-like” pattern on the surface to which the SCC12 cells adhere. The β4 integrin subunit in the cell in A shows colocalization with the laminin-332 in the matrix immediately underlying it (B). Colocalized antigens appear yellow in C. In the presence of GoH3 antibodies, the β4 integrin no longer clusters in the cell in D over the laminin-332 matrix (H). Arrow in G-I indicates a cell region where α3β1 integrin is clustered at the cell periphery, but is not organized into a Swiss cheese-like pattern. In J, in the presence of GoH3, clusters of α3β1 indicated by the arrow are found codistributed with the Swiss cheese organization of laminin-332 in the matrix (K). The colocalized antigens appear yellow in L. The arrowhead in J indicates α3β1 integrin found at the cell periphery in a cell region, sitting on an area of substrate deficient in laminin-332. Bar, 10mm.

4. Mechanisms of Integrin Crosstalk

To date, mechanisms that regulate integrin crosstalk generally involve the integrin β integrin cytoplasmic tail. With the exception of β4 integrin, the cytoplasmic domains of β integrins are short, composed of approximately 50 amino acids[33]. This tail acts as a docking site for over 40 proteins with the regulation of such interactions being key to integrin function and crosstalk[11, 13, 33]. The features of the β3 integrin tail serve as a model for other integrins, except the β4 integrin subunit. There are three domains that provide the major binding sites for cytoskeleton and signaling proteins: the membrane proximal NPxY motif containing regulatory tyrosine residues, a membrane distal NxxY motif and an intervening sequence bearing serine and threonine residues. We will next discuss how the regulation of protein binding to and the differential phosphorylation of the β integrin tail both likely play roles via which integrin crosstalk is mediated.

4.1. Talin

Talin is a large intracellular molecule of over 200kD, shown to induce the activation of integrins by increasing the affinity of an integrin for its ligand[12, 34-37]. The amino-terminal FERM domain of talin interacts with integrins[12, 36-38]. It is divided into three subdomains, termed F1, F2, and F3. The latter subdomain contains a phosphotyrosine binding (PTB)-like domain fold that exhibits high affinity binding for β integrin tails and is sufficient to activate the β3 integrin[12, 36-38]. It is believed that the F3 domain of talin initially engages the membrane distal region of the β integrin tail[10, 37]. Integrin activation is triggered by the interaction of the PTB-like domain of talin with the membrane proximal helix-forming domain of the β3 integrin tail[12, 36, 37, 39]. There are some differences in the sequences required for talin activation of β integrin tails. For example, talin mediated activation of β1 integrin requires the N-terminal and F1 domains as well as F3[36].

As mentioned previously, talin is a central molecular switch that regulates integrin crosstalk[11, 12, 39-41]. Indeed, Calderwood and colleagues have demonstrated that cells that over-express β integrin cytoplasmic tails defective in talin binding are unable to mediate crosstalk[41]. Moreover, integrin crosstalk can be reversed by over-expressing integrin binding and activating fragments of talin, while expression of a non-integrin binding protein that can sequester talin, such as PIPK1γ90, inhibits integrin activation[41].

Certain proteins that compete with talin for β integrin tail binding regulate integrin activation and therefore likely play an important role in the way talin mediates integrin crosstalk[11, 33, 42, 43]. For example, DOK, a downstream of kinase signaling proteins, is a PTB containing protein that binds to the membrane distal region of the β integrin tail[37, 44]. Since DOK fails to bind to the membrane proximal region of the β integrin tail, it cannot activate an integrin but can inhibit activation by competing for integrin binding with talin. Other PTB containing proteins, including Shc and NUMB, likely function in the same way by regulating talin-integrin interaction[33]. There is also evidence that talin-integrin interaction is inhibited when 14-3-3 proteins bind to phosphorylated serine/threonine residues in β integrin tails[33, 45]. Such is the case when T-cells are activated and threonine residue 758 in the β2 integrin tail is phosphorylated[45]. Another protein that may play an important role in regulating talin-integrin interaction and, hence, integrin activation is filamin, an actin cross linker[42]. Filamin binds to unphosphorylated serine/threonine residues within β7 integrin and prevents binding of talin[42].

The precise roles of PTB containing proteins such as DOK, filamin and 14-3-3 proteins in regulating talin-mediated integrin crosstalk should be an interesting avenue of future study. However, it is also clear that a variety of signaling enzymes modulate the binding of both talin and talin competitors to integrins via their ability to directly or indirectly phosphorylate key residues in the cytoplasmic tails of β integrins. We will discuss these next.

4.2. Protein Kinase A

There are several reports that demonstrate integrin ligand binding or clustering of β1 integrin with anti-β1 integrin antibodies leads to the activation of the cAMP dependent protein kinase A (PKA), a serine/threonine kinase which, in turn, mediates integrin crosstalk[46-48]. For example, Varner and colleagues have presented evidence that addition of α5β1 integrin function-blocking antibodies inhibits αvβ3-mediated cell migration and angiogenesis in vivo in a PKA-dependent fashion[47].

PKA has also been demonstrated to play a role as a mediator of integrin crosstalk and a negative regulator of αvβ3 integrin function in endothelial cells subject to shear stress[48]. Orr and colleagues have established that activation of α2β1 integrin by shear stress inhibits the activation state of both αvβ3 integrin and α5β1 integrin in endothelial cells plated on collagen[48]. Blocking PKA with a pharmacologic inhibitor restores ligand affinity of αvβ3 integrin but not α5β1 integrin. In contrast, in endothelial cells plated onto fibronectin or fibrinogen, flow activates α5β1 and αvβ3 integrin, eliciting activation of protein kinase C (PKC) which suppresses α2β1 integrin function[48]. These same workers also have presented evidence that talin is central to the integrin crosstalk they detail since its overexpression overrides integrin inhibition in endothelial cells subject to shear, regardless of substrate.

We recently demonstrated that in endothelial cells, β1 integrin function blocking antibodies inhibit αvβ3 integrin mediated adhesion via a pathway that involves PKA and inhibition of serine/threonine phosphatase I (PP1) via the inhibitor-1 pathway[46]. Inhibition of PP1 activity correlates with an increase in serine phosphorylation of the β3 integrin cytoplasmic tail[46]. Moreover, mutating serine 752 of β3 integrin to aspartic acid, a phosphomimetic, inhibits the ability of αvβ3 integrin to mediate adhesion in CHO cells[46]. Based on these studies, we have hypothesized that β1 integrin clustering results in activation of PKA which phosphorylates inhibitor-1, an endogenous inhibitor of serine/threonine phosphatase 1 inhibiting its activity. PP1 activity is required to maintain β3 integrin in an unphosphorylated state. Since overexpressing an activating form of talin surprisingly fails to overcome the inhibition on αvβ3 mediated cell adhesion by β1 integrin function blocking antibodies, it is unlikely that PKA is acting on talin directly[46]. Instead, we have speculated that PKA may regulate talin-integrin interaction indirectly by altering the ability of talin to associate with β3 integrin. We base this speculation on the literature and the numerous studies, some of which have been discussed above, that demonstrate that phosphorylation state of integrins can regulate the association of many intracellular proteins that alter the activation state of the integrin by modulating talin binding[33, 45].

4.3. Calcium/calmodulin dependent kinase II

Our own data indicate that β1 clustering or inhibition triggers signaling that inhibits ligand binding of αvβ3 integrin[46]. However, the reverse is also the case. For example, more than ten years ago, it was demonstrated that in leukocytes, ligation of α5β1 integrin enhances calcium/calmodulin dependent kinase II (CaMKII) which is required for α5β1 mediated phagocytosis and migration[49]. In contrast, ligation of αvβ3 integrin inhibits the ability of α5β1 integrin to support phagocytosis and migration in the same cell[49]. Moreover, the ability of αvβ3 integrin to modulate the activities of α5β1 integrin involves serine residue 752 in the β3 integrin tail. Mutating this residue to alanine has no effect on αvβ3 integrin ligand binding but affects the ability of αvβ3 to inhibit α5β1 integrin functions[49].

How does CaMKII regulate α5β1 integrin function in the above crosstalk scenario? Bouvard and colleagues have reported that in CHO cells activation of CaMKII or blocking calcineurin, a calcium calmodulin dependent protein phosphatase inhibits α5β1 interaction with its ligand fibronectin[50]. This same group identified integrin-cytoplasmic-domain-associated protein 1 (ICAP-1α) as the target for CaMKII activity and a regulator of α5β1 integrin affinity for ligand[51]. ICAP-1α has been shown to interact with the cytoplasmic tail of β1A integrin and binding is dependent on the NPxY integrin motif[51]. ICAP-1α contains several putative phosphorylation sites for PKC, PKA, PKG and CaMKII. Mutating threonine 38 residue to alanine generates an ICAPα protein that cannot be phosphorylated by CaMKII but can rescue CHO cell adhesion to fibronectin[51]. In contrast, mutating threonine 38 to aspartic acid, a phosphomimetic, results in a strong defect in cell spreading that cannot be overcome by inhibiting CaMKII activity. In other words, the balance of serine/threonine kinase activity and serine/threonine phosphatase activity regulates the activation state of α5β1 integrin by a process that does not involve phosphorylation of the integrin cytoplasmic tail but, instead, acts by altering the ability of the adaptor protein, ICAPα to associate with the β1 integrin cytoplasmic tail and compete with talin for binding[52, 53]. Indeed, ICAPα is a good example of an adaptor protein involved in integrin crosstalk. Its binding to integrin is regulated by serine/threonine kinases and serine/threonine phosphatases and it inhibits integrin function by negatively regulating the ability of talin to bind to β integrin tails[52].

5. Summary, Future Directions and Implication of Crosstalk for Integrin-based Treatment of Human Disease

As we have discussed, integrin-integrin crosstalk is a complex process involving cytoskeleton and signaling adaptor proteins. Clearly, talin is a key regulator of such crosstalk although we are only just beginning to understand how it modulates integrin affinity and how talin binding to integrin cytoplasmic tails is controlled. A number of competitors of talin-integrin binding have been identified but the number of these will surely grow. The role of phosphorylation of various residues in the β integrin tail is also key to the regulation of binding of both talin and its competitors and more study in this area is necessary. In addition, there is some evidence in the literature that integrin crosstalk may be at the level of regulation of the stability of integrin subunit mRNA[54]. Specifically, in one model system, it has been demonstrated that β1 integrin protein expression can down regulate αvβ3 integrin expression by decreasing the stability of the mRNA encoding the β3 integrin subunit[54].

Although crosstalk between the integrins expressed in skin cells has been proposed, the β4 subunit is very different from other β integrin subunits and lacks talin binding motifs. In other words, β4 integrin cannot sequester talin from α3β1 integrin in order to inhibit the ligand binding of the latter. How precisely α6β4 integrin crosstalks to α3β1 integrin is another potential area of research for the future.

At the cell biological level, integrin crosstalk complicates analyses where an antibody integrin or inhibitor is used. The same is true in instances where integrin subunit expression is manipulated. Any resulting phenotype might result not only from the inhibition or loss of the targeted integrin but may also result from effects on the ligand binding or signaling of the integrins with which it functional interacts via crosstalk.

A number of integrin antibody and small molecule inhibitors have been or are in the process of undergoing clinical evaluation for the treatment of human disease, including age related macula degeneration and certain cancers such as glioblastoma[55, 56]. Some of these inhibitors are designed to target β1 subunit-containing integrins while some others target αvβ3 integrin[55, 57]. These inhibitors work as a consequence of integrin crosstalk since, as we have already detailed, inhibition of β1 integrin perturbs the function of αvβ3 integrin and vice versa. However, there may be downsides to this phenomenon. An antibody inhibitor of α4 integrin has been used to treat Crohn's disease where it inhibits migration of leukocytes into the gut and reduces inflammation[31]. The same integrin inhibitor has been evaluated for the treatment of patients with multiple sclerosis. However, adverse effects of such treatment have been reported, possibly due to the effects of the inhibitor on the activity of integrins with which α4β1 integrin cross talks. Thus, understanding the molecular mechanisms that are involved in regulating the activation state of distinct integrins in a particular tissue may provide additional targets for the development of new therapeutic agents with greater specificity.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the NIH for grant support (HL067016, AR054184 to J.C.R.J. and KO1 CA106386 to A.M.G.).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Hynes RO. Cell. 2002;110:673–687. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00971-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Humphries JD, Byron A, Humphries MJ. J Cell Sci. 2006;119:3901–3903. doi: 10.1242/jcs.03098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arnaout MA, Goodman SL, Xiong JP. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2002;14:641–651. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(02)00371-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Geiger B, Bershadsky A, Pankov R, Yamad KM. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2001;2:793–805. doi: 10.1038/35099066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Diaz-Gonzalez F, Forsyth J, Steiner B, Ginsberg MH. Mol Biol Cell. 1996;7:1939–1951. doi: 10.1091/mbc.7.12.1939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Porter JC, Hogg N. Trends Cell Biol. 1998;8:390–396. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(98)01344-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Takagi J, Petre BM, Walz T, Springer TA. Cell. 2002;110:599–611. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00935-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hynes RO. Nat Med. 2002;8:918–921. doi: 10.1038/nm0902-918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liddington RC, Ginsberg MH. J Cell Biol. 2002;158:833–839. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200206011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Campbell ID, Ginsberg MH. Trends Biochem Sci. 2004;29:429–435. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2004.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Calderwood DA. J Cell Sci. 2004;117:657–666. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Critchley DR. Annu Rev Biophys. 2009;38:235–254. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.050708.133744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu S, Calderwood DA, Ginsberg MH. J Cell Sci. 2000;113:3563–3571. doi: 10.1242/jcs.113.20.3563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Riederer MA, Ginsberg MH, Steiner B. Thromb Haemost. 2002;88(5):858–864. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen YP, Djaffar I, Pidard D, Steiner B, Cieutat AM, Caen JP, Rosa JP. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1992;89:10169–10173. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.21.10169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen Y, O'Toole TE, Ylanne J, Rosa JP, Ginsberg MH. Blood. 1994;84:1857–1865. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Porter JC, Hogg N. J Cell Biol. 1997;138:1437–1447. doi: 10.1083/jcb.138.6.1437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Silva R, Amico GD, Hodivala-Dike K, Reynolds LE. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2008;28:1703–1713. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.108.172015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Folkman J. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1990;82(1):4–6. doi: 10.1093/jnci/82.1.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hodivala-Dike K. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2008;20:514–519. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2008.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tanjore H, Zeisberg EM, Gerami-Naini B, Kalluri R. Develop Dynamics. 2008;237:75–82. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.21385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Carlson TR, Hu H, Braren R, Kim YH, Wang RA. Development. 2008;135:2193–2202. doi: 10.1242/dev.016378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brooks PC, Clark RAF, Cheresh DA. Science. 1994;264:569–571. doi: 10.1126/science.7512751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brooks PC, Montgomery AMP, Rosenfeld M, Reisfeld RA, Hu T, Klier G, Cheresh DA. Cell. 1994;79:1157–1164. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90007-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Eliceiri BP, Cheresh DA. J Clin Invest. 1999;103(9):1227–1230. doi: 10.1172/JCI6869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Reynolds LE, Wyder L, Lively JC, Taverna D, Robinson SD, Huang X, Sheppard D, Hynes RO, Hodivala-Dilke KM. Nat Med. 2002;8:27–34. doi: 10.1038/nm0102-27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gonzalez AM, Gonzales M, Herron SG, Nagavarapu U, Hopkinson SB, Tsuruta D, J JCR. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2002;99:16075–16080. doi: 10.1073/pnas.252649399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ly DP, Zazzali KM, Corbett SA. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:21878–21885. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M212538200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hintermann E, Bilban M, Sharabi A, Quaranta V. J Cell Biol. 2001;153:465–478. doi: 10.1083/jcb.153.3.465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Goldfinger LE, Hopkinson SB, deHart GW, Collawn S, Couchman JR, Jones JCR. J Cell Sci. 1999;112:2615–2629. doi: 10.1242/jcs.112.16.2615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.MacDonald JK, McDonald JW. Chochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;24:CD006097. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006097.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Margadant C, Raymond K, Kreft M, Sachs N, Janssen H, Sonnenberg A. J Cell Sci. 2009;2009:278–288. doi: 10.1242/jcs.029108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Legate KR, Fassler R. J Cell Sci. 2009;122:187–198. doi: 10.1242/jcs.041624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tadokoro S, Shattil SJ, Eto K, Tai V, Liddington RC, de Pereda JM, Ginsberg MH, Calderwood DA. Science. 2003;302:103–106. doi: 10.1126/science.1086652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kim M, Carman CV, Springer TA. Science. 2003;301:1720–1725. doi: 10.1126/science.1084174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bouaouina M, Lad Y, Calderwood DA. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:6118–6125. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M709527200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wegener KL, Partridge AW, Han J, Pickford AR, Liddington RC. Cell. 2007;128:171–182. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.10.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Calderwood DA, Zent R, Grant R, Rees JG, Hynes RO, Ginsberg MH. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:28071–28074. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.40.28071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Calderwood DA, Fujioka Y, de Pereda JM, Garcia-Alvarez B, Nakamoto T, Margolis B, McGlade CJ, Liddington RC, Ginsberg MH. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2003;100:2272–2277. doi: 10.1073/pnas.262791999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Calderwood DA, Ginsberg MH. Nature Cell Biology. 2003;5(8):694–697. doi: 10.1038/ncb0803-694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Calderwood DA, Tai V, Di Paolo G, De Camilli P, Ginsberg MH. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:28889–28895. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M402161200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kiema T, Lad Y, Jiang P, Oxley CL, Baldassarre M, Wegener KL, Campbell ID, Ylanne J, Calderwood DA. Mol Cell. 2006;21:337–347. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fagerholm SC, Hilden TJ, Nurmi SM, Gahmberg CG. J Cell Biol. 2005;171:705–715. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200504016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Oxley CL, Anthis NJ, Lowe ED, Vakonakis I, Campbell ID, Wegener KL. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:5420–5426. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M709435200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Takala H, Nurminen E, Nurmi SM, Aatonen M, Strandin T, Takatalo M, Liema T, Gahmberg CG, Ylanne J, Fagerholm SC. Blood. 2008;112:1853–1862. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-12-127795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gonzalez AM, Claiborne J, Jones JCR. J Biol Chem. 2008;283(14):31849–31858. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M801345200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kim S, Harris M, Varner JA. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:33920–33928. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M003668200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Orr WA, Ginsberg MH, Shattil SJ, Deckmyn H, Schwartz MA. Mol Biol Cell. 2006;17:4686–4697. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E06-04-0289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Blystone SD, Slater SE, Williams MP, Crow MT, Brown EJ. J Cell Biol. 1999;145:889–897. doi: 10.1083/jcb.145.4.889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bouvard D, Molla A, Block M. J Cell Sci. 1998;111:657–665. doi: 10.1242/jcs.111.5.657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bouvard D, Block MR. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1998;252:46–50. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1998.9592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bouvard D, Vignoud L, Dupe-Manet S, Abed N, Fournier H, Vincent-Monegat C, Retta SF, Fassler R, Block MR. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:6567–6574. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M211258200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Millon-Fremillon A, Bouvard D, Grichine A, Manet-Dupe S, Block MR, Albiges-Rizo C. J Cell Biol. 2008;180:427–441. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200707142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Retta SF, Cassara G, D'Amato M, Alessandro R, Pellegrino M, Degani S, De Leo G, Silengo L, Tarone G. Mol Biol Cell. 2001;12:3126–3138. doi: 10.1091/mbc.12.10.3126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Stupp R. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:1637–1638. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.09.8376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Weis SM, Stupack DG, Cheresh DA. Cancer Cell. 2009;15:359–361. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ramakrishnan V, Bhaskar V, Law DA, Wong MH, DuBridge RB, Breinberg D, O'Hara C, Powers DB, Liu G, Grove J, Hevezi P, Cass KM, Watson S, Evangelista F, Powers RA, Finck B, Wills M, Caras I, Fang Y, McDonald D, Johnson D, Murray R, Jeffry U. J Exp Ther Oncol. 2006;5:273–286. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]