Abstract

Activation of the complement system by injury increases inflammation by producing complement fragments C5a and C3a which are able to recruit and activate immune cells. Complement activation may contribute to pain after inflammation and injury. In the present study, we examined whether C5a and C3a elicit nociception when injected into mouse hind paws in vivo, and whether C5a and C3a activate and/or sensitize mechanosensitive nociceptors when applied on peripheral terminals in vitro. We also examined the dorsal root ganglia (DRG) for C5a receptor (C5aR) mRNA and effects of C5a and C3a on intracellular Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]i) using Ca2+ imaging. Heat hyperalgesia was elicited by intraplantar injection of C5a, and mechanical hyperalgesia by C5a and C3a. After exposure to either C5a or C3a, C-nociceptors were sensitized to heat as evidenced by an increased proportion of heat responsive fibers, lowered response threshold to heat and increased action potentials during and after heat stimulation. A-nociceptors were activated by complement. However, no change was observed in mechanical responses of A- and C- nociceptors after C5a and C3a application. The presence of C5aR mRNA was detected in DRG. C5a and C3a application elevated [Ca2+]i and facilitated capsaicin-induced [Ca2+]i responses in DRG neurons. The results suggest a potential role for complement fragments C5a and C3a in nociception by activating and sensitizing cutaneous nociceptors.

Keywords: injury, nociception, hyperalgesia, nociceptor, sensitization, inflammation

INTRODUCTION

The complement system is a group of more than 30 proteins, some of which can be serially activated and participate in a cascade that produces inflammation and participates in host defense. The complement system is activated in various injury states, e.g. rheumatoid arthritis [30], multiple sclerosis [10], sepsis [42] and tissue injury by surgical trauma [11,16,18].

Activation of the complement system enhances inflammation by producing split products such as complement fragments C5a and C3a that are potent proinflammatory peptides and act through G-protein coupled receptors (C5aR and C3aR, respectively) to exert their biological effects. C5a and C3a are able to enhance inflammation by recruiting and activating immune cells leading to the release of various algogenic mediators [12,13,43]. C5a and C3a may contribute to pain in pathologic states. For example, C5a receptor blockade decreased pain behaviors in inflammatory, neuropathic and postoperative pain models [5,14,39] indicating a pronociceptive role of C5a. However, there is little information on the effects of C5a and C3a on nociceptors. In the present study, we tested whether the complement fragments C5a and C3a elicit pain when injected into the hind paw in vivo, and whether C5a and C3a activate and/or sensitize primary afferent nociceptors when applied on the peripheral terminals in vitro. We also examined the dorsal root ganglia (DRG) for C5aR mRNA using real time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and effects of C5a and C3a on intracellular Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]i) using Ca2+ imaging.

MATERIALS and METHODS

1. Animals

Male C57BL/6J mice (20–30 grams and 6–12 weeks of age, Jackson Labs) that were housed in groups of four to five, with food and water available ad libitum under a 12-h light/dark cycle, were used in this study. Experimental protocols were approved by The Animal Care and Use Committee at The University of Iowa and the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee, VAPAHCS.

2. Drug preparation

Recombinant mouse C5a and human C3a were purchased from R&D Systems Inc. (Minneapolis, MN) and Calbiochem-Novabiochem International Inc. (San Diego, CA), respectively. All drugs were dissolved in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) with 0.1% bovine serum albumin, and the PBS-vehicle was prepared in the same manner without adding the complement.

3. Behavioral studies

Mice were acclimated to testing cages containing either a stainless steel mesh (for spontaneous pain behaviors and mechanical withdrawal responses) or a heat tempered glass floor (for heat withdrawal latency) for 2 hours per day at least 5 days before testing. To minimize the number of animals required, both the left and right hindpaws were utilized. First the left paw was utilized, then the right hind paw was also used at least 7 days after injection into left hind paw. In preliminary experiments, any drug-induced pain behaviors in the left hind paw had resolved within 2 days. The person performing the behavioral data was blinded to drug and dose.

Drug administration

Drug injections for mechanical or heat tests were performed under light isoflurane anesthesia using 4% (1 min) for induction and 1.5% (1 min) for maintenance during injection. C5a, C3a or PBS-vehicle solution was injected into plantar surface of the hind paw subcutaneously using an insulin syringe and a 31-gauge needle in a total volume of 10 μl. For spontaneous pain behaviors, injections were performed using gentle restraint without anesthesia. The needle tip was inserted between the digits and directed proximally, where drug (or vehicle) was injected into the middle of the tori of the paw. To minimize mechanical trauma, the needle tip did not invade the area that we applied mechanical or heat stimuli.

Spontaneous pain behaviors

Immediately after injection of C5a 100 ng, C3a 100 ng or PBS-vehicle, mice were returned to the mesh floor and both hind paws were observed for 30 minutes. Time spent licking, biting and shaking the hindpaws was recorded. The time spent licking, biting and shaking the contralateral (uninjected) hindpaw was subtracted from the injected hind paw and this difference was used as the index of spontaneous nociception.

Heat withdrawal latency

The heat stimulus was a light from a 100-W projector lamp, with an aperture diameter of 6 mm, applied from underneath the glass floor onto the middle of the tori of the injected paw. Before data collection, the intensity of the stimulus was adjusted so that mice withdrew after approximately 19–21 sec. The latency in seconds to evoke withdrawal was determined with a cutoff value of 25 sec. Three trials at least 5 min apart were used to obtain the average paw withdrawal latency. The baseline values were obtained immediately before drug injection. After injection of C5a (10, 100 or 500 ng), C3a 100 ng or PBS-vehicle, mice were returned onto the glass floor and withdrawal latencies to heat were assessed 30, 60, 120, 180 min and 1 day after injection.

Mechanical withdrawal responses

Von Frey filaments were applied to the middle of tori of the paw from least to greatest forces (0.6-, 1.4-, 3.3-, 5.7- and 13.1-mN). Each filament was applied five times at each time point, with 10 sec between applications. Data were expressed as the percent of paw withdrawal for each filament. The baseline values were obtained immediately before drug injection by applying calibrated von Frey filaments. After injection of C5a (10, 100 or 500 ng), C3a 100 ng or PBS-vehicle, mice were returned onto the mesh floor and responses to von Frey filaments were assessed 30, 60, 120, 180 min and 1 day after injection.

4. Electrophysiological studies

In Vitro single fiber recordings

Mice were killed using CO2 inhalation, and after the hair on the leg was clipped, the hairy skin of the hind paw innervated by saphenous nerve was dissected. Attached connective tissue, muscle or tendon was removed. To ensure a sufficient length of axons for recording, the nerve was dissected up to the lumbar plexus.

The organ bath consists of two chambers separated by an acrylic-based wall. The larger chamber is the perfusion chamber which is continuously superfused with a modified Krebs–Hensleit solution (in mM: 110.9 NaCl, 4.8 KCl, 2.5 CaCl2, 1.2 MgSO4, 1.2 KH2So4, 24.4 NaHCO3, and 20 glucose), which was saturated with a mixture of 95% O2 and 5% CO2. The temperature of the bath solution was maintained at 31 ± 1°C. After dissection, the preparation was placed with the epidermal side down. The nerves attached to the skin were drawn through one small hole to the second chamber, which was filled with paraffin oil. The nerve was placed on a fixed mirror, the sheath was removed and nerve filaments repeatedly teased to allow single fiber recordings to be made using platinum electrodes, one for recording and the other for reference. The reference electrode was grounded to the perfusion chamber. Single nociceptive afferent fibers were recorded extracellularly with a differential amplifier (DAM50, Harvard Apparatus, Holliston, MA). Neural activity was amplified and filtered using standard techniques. Amplified signals were led to an oscilloscope and an audio monitor and then into PC computer via a data acquisition system (spike2/CED1401 program). Action potentials collected on a computer were analyzed off-line with a template matching function of spike 2 software.

The conduction velocity of the axon was determined by monopolar electrical stimulation through an epoxy-coated electrode with an uninsulated tip. The supramaximal square wave pulses (0.2–2 ms duration; 0.5 Hz) were delivered at the mechanosensitive site of a receptive field. The distance between receptive field and the recording electrode (conduction distance) was divided by the latency of the action potential. The single fibers were classified as being either A- or C-fibers if their conduction velocity was between 1.2 and 8.0 m/s or slower than 1.2 m/s, respectively. The fast conducting, rapidly adapting fibers were not examined. The search strategy was mechanical stimulation by a fire-polished glass rod. Thus, all fibers were either A- or C-mechanonociceptors.

Complement application

Spontaneous activity

The mechanosensitive receptive field of each fiber was isolated with a hollow metal cylinder. Silicone grease was added to prevent leakage from the bath into the receptive field. After a 2 min baseline recording, the Krebs solution inside the ring was replaced with C5a (100, 500 or 1000 ng/ml), C3a 1000 ng/ml or PBS-vehicle in a 100 μl volume and fiber activity was recorded for 2 min. The fiber was considered activated by the drug if activity of at least 0.1 impulse/s was elicited if background activity was absent during baseline recording, or if ongoing activity was present an increase of at least 2 standard deviations greater than the ongoing background activity.

Heat stimulation

After spontaneous activity was assessed, a standard feedback-controlled, heat ramp was delivered once by a customized heat stimulator (Bioengineering, University of Iowa, Iowa City, IA). The drug solution inside the ring was removed and a thermocouple was gently placed to measure the subcutaneous temperature. A radiant lamp was placed in the translucent area underneath the organ bath and the light beam was focused onto the epidermal side of the skin. After 10 sec baseline recording, a computer-controlled standard heat ramp was delivered starting from 32°C to 45°C over 15 sec. The peak temperature, 45°C, was used to avoid potential tissue damage of higher temperatures. We determined that the temperature of the epidermal side was about 1 degree centigrade higher than the subdermal side. Fibers having a receptive field in a previously heat-stimulated area were avoided for subsequent recordings. Each fiber was tested with heat only once because we noted that repeated heating sensitized the fiber responses. Action potentials were counted during the heat stimulus and for 5 sec after the peak temperature when the temperature remained elevated to 41°C. Action potentials between 20 sec and 60 sec after the onset of the heat were also counted for ‘after heat’ analysis that reflect after discharges following the stimulus. The temperature that elicited the first action potential during heat stimulation was considered as threshold if background activity was absent. If background activity was present, threshold was determined by the temperature during heating that increased background activity at least two standard deviations greater than the baseline (10 sec, 1 sec bin). Background activity was subtracted from total action potential numbers during recording period, assuming background activity was sustained during heat response recording.

C5a, C3a and PBS-vehicle were tested on 55 C-fibers and 38 A-fibers to determine the percentage of heat responsive fibers and to quantitate the heat response. An additional 55 C-fibers and 9 A-fibers were included for quantification of heat responses.

Mechanical stimulation

To avoid repeated application of drug for both heat and mechanical stimuli, mechanical responses were tested in separate experiments from heat. Servo-controlled mechanical stimulation (Series 300B dual mode servo system, Aurora Scientific, Canada) was used to measure mechanosensitivity. The most sensitive spot of the receptive field of each fiber was isolated with a metal cylinder as described above. A flat and cylindrical metal probe (tip size 0.7 mm) attached to the tip of stimulator arm was placed onto the receptive field so that no force was generated. After a 2 min baseline recording, a computer-controlled ascending series of square force stimuli (5-, 10-, 20-, 40-, 80- and 120-mN; 2 sec duration; 60 sec intervals) was applied to the receptive field. Then, the Krebs solution inside the ring was replaced with C5a 1000 ng/ml, C3a 1000 ng/ml or PBS-vehicle solution with 100 μl volume without any movement of mechanical probe or ring. After 2 min of drug application, the same series of mechanical stimuli was applied to the receptive field. The mechanical force that elicited the first action potential during mechanical stimulation was considered as threshold if background activity was absent. If background activity was present, threshold was determined by the force that increased background activity at least two standard deviations greater than the average background for baseline recording. Background activity was subtracted from the total number of action potentials during mechanical stimulation, assuming background activity was sustained during the recording period.

5. Analysis of C5aR mRNA

Six to 8 lumbar ganglia (L3–L6) from 3 mice were used to make 3 preparations for C5aR mRNA. Briefly, mice used in these experiments were first asphyxiated using CO2 and perfused by intracardiac injection of 10 ml of 0.9% NaCl. This was followed by perfusion with 20 ml of 0.1 M PBS. The dorsal root ganglia (DRGs) were then dissected under low power magnification from the L3 through L5 nerve roots. Dissected tissue was snap frozen in liquid nitrogen and kept at −80°C until use. Before RNA purification, the samples were first homogenized using an ultrasound device, then centrifuged for 10 min at 12,000 times gravity at 4°C. The supernatants were processed using the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) according to manufacturer’s instructions. The purity and concentration of the purified RNA was determined spectrophotometrically. Subsequently, cDNA was synthesized from this total RNA using random hexamer priming and a First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA ) [28].

For PCR analysis, reactions were conducted in a volume of 4 μl using the Sybr Green I master kit (PE applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). Briefly, 2 μl of a mixture of 2x sybr green and C5aR primers (forward: gtcctgttcacgaccgtttt, reverse: acggtcggcactaatggtag) was loaded with 2 μl diluted cDNA template in each well. 8 μl mineral oil was loaded in each well to prevent loss of solution. PCR parameters were 95°C, 5min then [95°C, 30s→ 60°C, 30s→ 72°C, 60s] for 40 cycles. Agarose electrophoresis (2%) gels were used to separate reaction products, and ethidium bromide was used to visualize bands. 18s RNA was used as an internal control. The 18s primers were purchased from Ambion (Austin, TX).

6. Measurements of [Ca2+]i in cultured DRG neurons

Cell culture

DRG neurons were obtained from adult (6–16 week old) C57BL/6 (Taconic, Germantown, NY) mice. The animals were killed under isoflurane (20% in glycerol) anesthesia. DRG neurons were dissected, collected into ice cold PBS (1.54 mM KH2PO4, 155.17 mM NaCl, 2.71 mM Na2HPO4, pH 7.2) and incubated at 37 °C for 20 min in collagenase A (2 mg/ml, Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN) diluted with medium without serum (DMEM, 20 mM HEPES, 0.5 U/ml penicillin, 0.5 μg/ml streptomycin). Cells were washed in medium without serum and centrifuged at 750 rpm for 3 min in a Hermle Z300 centrifuge with rotor 220.72 V04. Cells were digested using Pronase E (1 mg/ml, Serva Electrophoresis GmbH, Heidelberg, Germany) for 10 min at 37 °C. After washing and centrifugation, cells were mechanically dissociated using flame-polished Pasteur pipettes of decreasing diameters and plated on poly-L-ornithine (0.2 mg/ml in 150 mM boric buffer) and laminin (0.5 mg/ml in PBS, Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN) coated glass coverslips. Cells were grown in DMEM supplemented with 5% heat-inactivated horse serum, 5% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum, 50 ng/ml NGF, 6 μg/ml insulin, 0.5 U/ml penicillin and 0.5 μg/ml streptomycin (pH 7.4) and maintained at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2. Experiments were carried out 16–24 hrs after plating.

[Ca2+]i measurements

The standard extracellular recording HEPES-buffered Hank’s salt solution (HH buffer) contained 140 mM NaCl, 5 mM KCl, 1.3 mM CaCl2, 0.4 mM MgSO4, 0.5 mM MgCl2, 0.4 mM KH2PO4, 0.6 mM NaHPO4, 3 mM NaHCO3, 10 mM glucose, 10 mM HEPES, pH 7.35 with NaOH (310 mOsm/kg with sucrose). DRG neurons were incubated for 25 min in HH buffer containing 2 μM of the AM form of Fura-2 at room temperature (22 °C). Cells were placed in a flow-through chamber mounted on the stage of an inverted IX-71 microscope (Olympus, Japan) and washed for 10 min prior to the experiment. Fluorescence was alternately excited at 340 (12 nm bandpass) and 380 (12 nm bandpass) using the Polychrome IV monochromator (TILL Photonics, Germany) via a 20x (NA=0.75, Olympus, Japan). Emitted fluorescence was collected at 510 (80) nm using an IMAGO CCD camera (TILL Photonics, Germany). Pairs of 340/380 nm images were sampled every 2 sec. The fluorescence ratio (R=F340/F380) was converted to [Ca2+]i according to the formula: [Ca2+]i = Kd β (R−Rmin)/(Rmax−R) [15]. The dissociation constants (Kd) used for Fura-2 was 225 nM (Molecular Probes Handbook). Rmin, Rmax and β were determined by applying 10 μM ionomycin in Ca2+-free buffer (1 mM EGTA) and HH buffer (1.3 mM Ca2+). Calibration constants were: Rmin=0.21, Rmax=3.45 and β=6.97. Fluorescence was corrected for background, as determined in an area that did not contain a cell. Data were processed using TILLvisION 4.0.1.2 (TILL Photonics, Germany) and GraphPad PRISM 5.0 (GraphPad, La Jolla, CA).

The effects of C5a and C3a on transient receptor potential channel vanilloid subtype 1 (TRPV1) were examined using two applications of the TRPV1 agonist capsaicin (50 nM, 10 sec, 5 min between the applications). Cells were used for further analysis only if during capsaicin stimulation they showed a [Ca2+]i elevation that was at least 100% higher than the basal [Ca2+]i in response to either first or second capsaicin application. For each analyzed cell, the response ratio was calculated as A2/A1, where A1 and A2 are the amplitudes of [Ca2+]i changes induces by the first and second capsaicin application, respectively [35].

7. Statistical tests

Parametric and non-parametric analyses were used based on the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test for normal distribution (SigmaStat software. Jandel Corporation, San Rafael, CA). Spontaneous pain behaviors were analyzed using one-way ANOVA. For heat behavioral data, the differences between groups were evaluated using two-way repeated measures ANOVA. Between group differences were subsequently analyzed by one-way ANOVA followed by post-hoc Holm-Sidak test or unpaired t-test to compare each time point vs PBS-vehicle. Within group analyses evaluated differences between pre-drug values versus time after injection by one-way ANOVA for repeated measures followed by Holm-Sidak test. For mechanical behavioral data, the differences between groups were evaluated using of Friedman ANOVA. Between group differences were subsequently analyzed by Kruskall-Wallis ANOVA (more than 2 groups) followed by post-hoc Dunn’s test or Mann-Whitney rank sum test (2 groups) to compare drug at each time point vs PBS-vehicle. Within group analyses evaluated differences between pre-drug values versus time after injection by Friedman repeated measures ANOVA followed by Dunn’s test. All behavioral data are presented as means ± SEM.

For electrophysiological data, Fisher’s exact test was used to compare the percentage of heat responsive fibers between groups. Heat response threshold, total action potentials during heat stimulation and total action potentials after heat stimulation was analyzed using Kruskall-Wallis ANOVA and post hoc Dunn’s test or Mann-Whitney rank sum test. Analysis of the mechanical stimulus–response relationship before and after drug was performed using two-way repeated measures ANOVA. Electrophysiological data for heat and mechanical data are presented as median value and means ± SEM, respectively.

For calcium imaging data, the effects of C5a and C3a on TRPV1-mediated responses were analyzed using one-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni’s post hoc test. Data are presented as means ± SEM. A P-value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Behavior

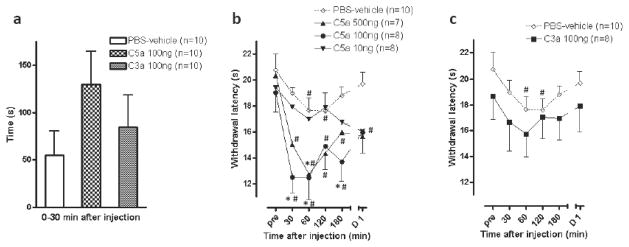

There was very little spontaneous pain behavior produced by PBS-vehicle, C5a or C3a (Fig. 1a). The greatest apparent effect was after injection of 100 ng of C5a, which produced 129.4 ± 35.2 sec of pain related behaviors. However, this was not statistically different from PBS-vehicle (55.1 ± 25.5 sec).

Fig 1.

Effects of C5a and C3a on spontaneous pain behaviors and withdrawal responses to heat stimuli. (a) Spontaneous pain behaviors after injection of C5a 100 ng, C3a 100 ng or PBS-vehicle. (b, c) Withdrawal latencies to heat after injection of C5a (10, 100 or 500 ng), C3a 100 ng or PBS-vehicle. PBS-vehicle data in (b) is also shown in (c). pre is time before injection; D1 is 1 day after injection. *P<0.05 vs PBS-vehicle, #P<0.05 vs pre. Data are presented as mean ± SEM.

Injection of PBS-vehicle produced a small decrease in the heat response latency in mice; this was significant only at 60 and 120 min after injection (P<0.05 vs pre) (Fig. 1b). The 500 ng dose of C5a decreased heat response latency at 60 min after injection compared to PBS-vehicle, whereas the 100 ng dose decreased the latency from 30 to 60 min after injection (P<0.05 vs PBS-vehicle). When C3a was administered at a dose of 100 ng, it did not significantly change the heat withdrawal latency when compared to PBS-vehicle treated mice (Fig. 1c).

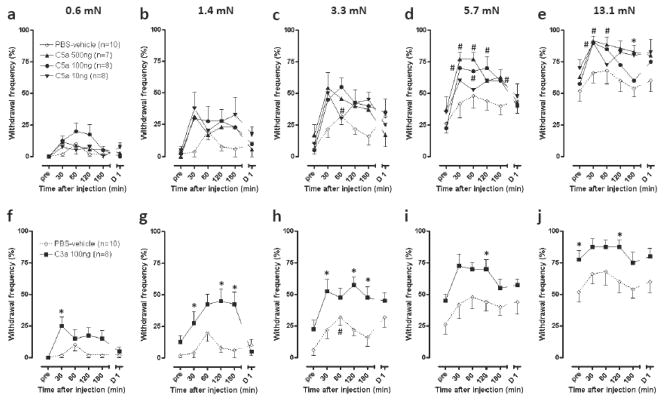

There was little effect of PBS-vehicle on the mechanical responses versus pre injection (Fig. 2). However, all doses of complement tended to increase the withdrawal frequency to a variety of bending forces. The effect of C5a was significant at the strongest filaments, 5.7- and 13.1-mN, and evident at early time points (30 and 60 min) after injection (P<0.05 vs pre). The effect of C5a showed little dose dependence across the range of doses tested. C3a 100 ng significantly increased mechanical responses to all tested filaments compared to PBS-vehicle (P<0.05 vs PBS-vehicle).

Fig 2.

Effects of C5a and C3a on withdrawal frequency to mechanical stimuli. (a–j) Withdrawal frequencies to incremental mechanical stimuli after injection of C5a (10, 100 or 500 ng, a–e), C3a 100 ng (f–j) or PBS-vehicle. PBS-vehicle data in (a–e) are also shown in (f–j). pre is time before injection; D1 is 1 day after injection. *P<0.05 vs PBS-vehicle, #P<0.05 vs pre. Data are presented as mean ± SEM.

A- and C-fiber recording

Spontaneous activity

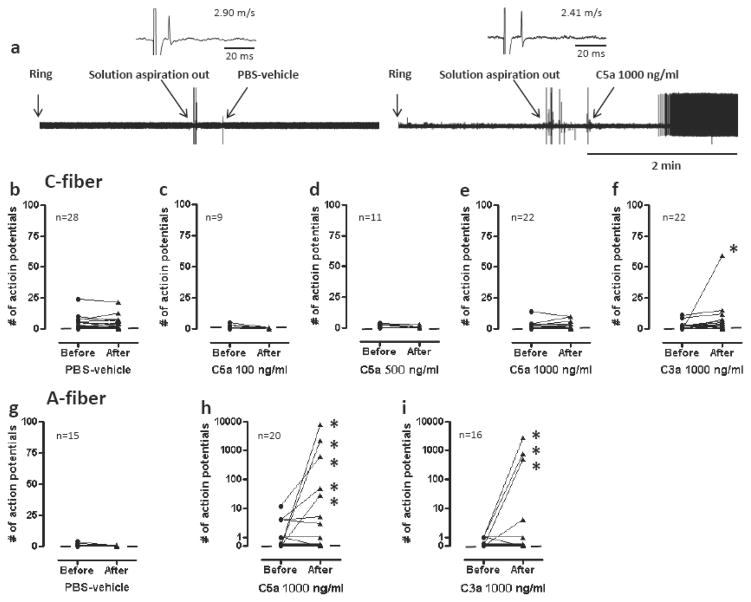

Neither PBS-vehicle nor C5a increased the spontaneous activity of C-fibers. The activity of only one C-fiber was increased by C3a (Fig. 3). Altogether, 5 of 20 A-mechanonociceptors exhibited increased activity after application of C5a and 3 of 16 to C3a. In some cases, this activity was markedly increased to as high as 60 imp/sec during the 2 min recording period.

Fig 3.

Effects of C5a and C3a on spontaneous activity of mechanonociceptors. (a) Example recordings of A-fibers before and after application of PBS-vehicle or C5a 1000 ng/ml. Ring is time of application of cylinder on the receptive field. Artifacts are produced during replacement of solutions as marked. (b–i) Spontaneous activities of C-fibers (b–f) or A-fibers (g–i) before and after exposure to C5a (100, 500 or 1000 ng/ml), C3a 1000 ng/ml or PBS-vehicle. Each line on the graphs represents a single unit. Asterisks indicate activation of nociceptors by drug application. Small horizontal lines in each graph indicate median values.

Heat stimulation

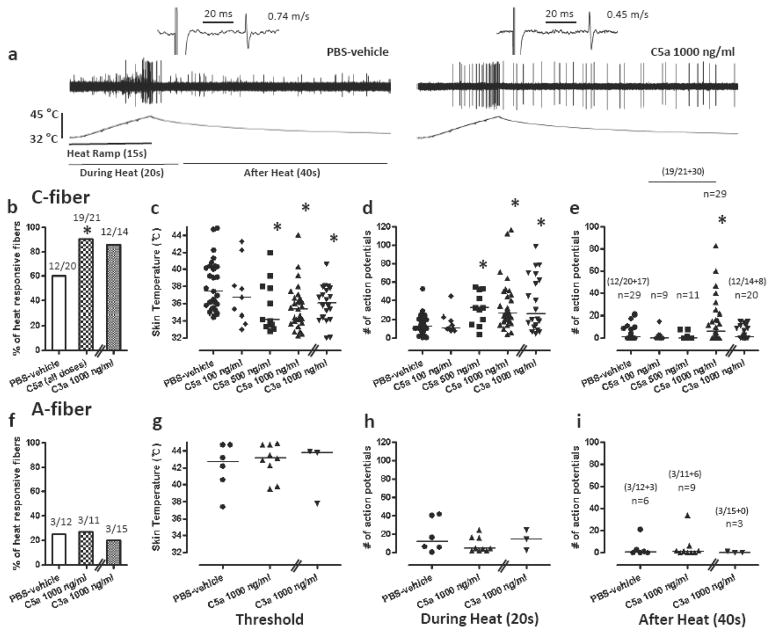

For heat, C5a increased the proportion of heat responsive C-fibers (19/21, 90.4%; P<0.05 vs PBS-vehicle) compared to PBS-vehicle (12/20, 60.0%) (Fig. 4). C5a (500 ng and 1000 ng/ml) decreased the heat threshold and increased the total number of action potentials during and after heating. A single concentration of C3a 1000 ng/ml produced a similar greater proportion of C-fibers responding to heat (12/14, 85.7%), but this was not different than PBS-vehicle. C3a also decreased heat thresholds and increased the total number of action potentials during heating. Neither C5a or C3a affected the proportion of heat responsive A-fibers or the heat threshold of those that responded to heat.

Fig 4.

Effects of C5a and C3a on heat responses of mechanonociceptors. (a) Example recordings of C-fibers after application of PBS-vehicle or C5a 1000 ng/ml. (b, f) Proportion of C-fibers (e) and A-fibers (f) responsive to heat after application of C5a (all doses: 100, 500 and 1000 ng/ml), C3a 1000 ng/ml or PBS-vehicle. (c–e, g–i) Heat responses of C-fibers (c–e) or A-fibers (g–i) after exposure to C5a (100, 500 or 1000 ng/ml), C3a 1000 ng/ml or PBS-vehicle. Heat thresholds (c, g) and total action potentials for 20 sec during heat application (d, h) and 40 sec after heat application (e, i). Each symbol represents a single unit. *P<0.05 vs PBS-vehicle. Data are presented as median values.

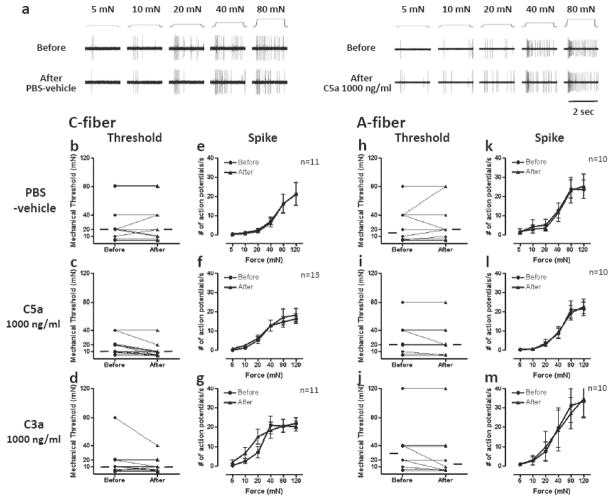

Mechanical stimulation

C-fiber responses to mechanical stimuli were not sensitized by PBS-vehicle, C5a or C3a (Fig. 5). Likewise, PBS-vehicle, C5a and C3a did not enhance mechanical responsiveness of A-fiber mechanonociceptors. Neither the threshold nor the stimulus response relationship was enhanced in our analyses.

Fig 5.

Effects of C5a and C3a on mechanical responses of mechanonociceptors. (a) Example recordings of C-fibers before and after application of PBS-vehicle or C5a 1000 ng/ml. (b–d, h–j) Mechanical thresholds of C-fibers (b–d) or A-fibers (h–j) before and after exposure to C5a 1000 ng/ml, C3a 1000 ng/ml or PBS-vehicle. Each line represents a single unit. The horizontal lines in each graph indicate median values. (e–g, k–m) Mechanical stimulus response function of C-fibers (e–g) and A-fibers (k–m) before and after exposure to C5a 1000 ng/ml, C3a 1000 ng/ml or PBS-vehicle. Data are presented as means ± SEM.

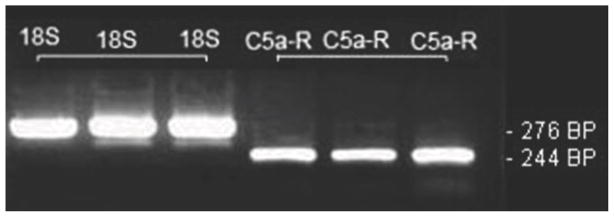

Identification of C5aR mRNA

Because our results most strongly support a role for C5a in sensitizing nociceptive afferent neurons, we undertook studies to examine C5aR expression in DRG neurons. RT-PCR studies (Fig. 6) demonstrates the presence of C5aR mRNA in DRG homogenates.

Fig 6.

Identification of C5aR mRNA in DRG neurons. Example bands from 3 separate DRG preparations containing 6 to 8 lumbar ganglia (L3–L6) in which either 18S RNA or C5aR mRNA specific bands were amplified. The expected PCR product sizes are provided.

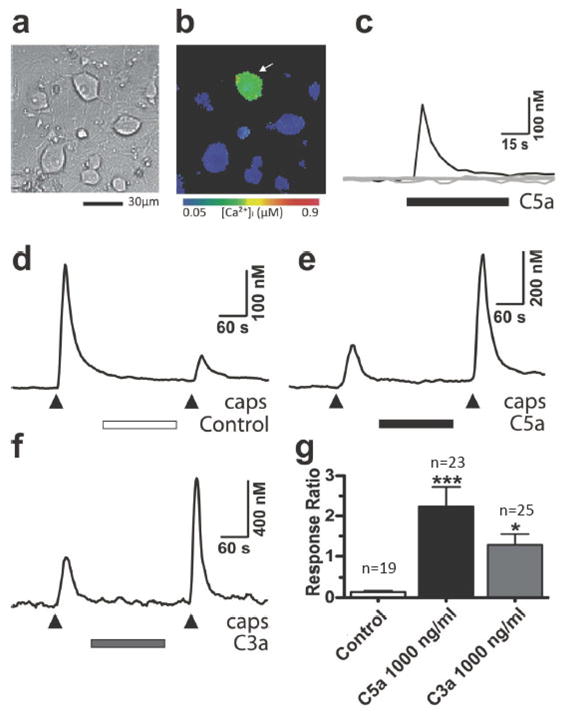

Facilitation of capsaicin-induced responses by C5a and C3a

The described heat sensitization of C-fibers induced by C5a and C3a (Fig. 4) suggests that the function of TRPV1 can be facilitated by the complement fragments. Therefore, we examined the effects of C5a and C3a on TRPV1-mediated responses in cultured DRG neurons using [Ca2+]i imaging as previously described [35]. Application of C5a (1000 ng/ml) or C3a (1000 ng/ml) evoked transient [Ca2+]i elevations in 6.3% (n=227) and 5.8% (n=193) of DRG neurons, respectively (Fig. 7a–c). This observation is consistent with the ability of C5a and C3a to induce spontaneous activity in some primary afferent fibers (Fig. 3). TRPV1-mediated responses were elicited by two consecutive capsaicin applications (50 nM, 10 s). Under the control conditions (no additional treatment), the amplitude of the second [Ca2+]i response was markedly smaller than that of the first one, likely as a result of Ca2+/calcineurin-dependent desensitization of TRPV1 [2,23], yielding the response ratio of 0.14 ± 0.03 (n=19; Fig. 7d). Treatments with either C5a or C3a between the capsaicin applications strongly potentiated the second capsaicin-induced [Ca2+]i response (Fig. 7e,f). The response ratios for C5a and C3a applications were 2.23 ± 0.49 (n=23) and 1.29 ± 0.27 (n=25), respectively. The facilitatory effects of both complement fragments were statistically significant (Fig. 7g).

Fig 7.

Effects of C5a and C3a on [Ca2+]i in cultured DRG neurons. (a) Appearance of adult mouse DRG neurons in culture. (b) [Ca2+]i distribution in DRG neurons at the peak of C5a (1000 ng/ml)-induced response. [Ca2+]i is presented using a color-coded scale. Note, that [Ca2+]i elevation is restricted to neurons only (identified by round cell bodies). (c) Time course of C5a-induced [Ca2+]i changes in the same cells that are shown in (b). Black trace indicates the responding neuron (arrow) and gray traces indicate other non-responding neurons in the field. (d–f) Examples of [Ca2+]i responses induced by two capsaicin applications (50 nM, 10 s, 5 min apart). DRG neurons were left untreated between the applications (control; d) or were treated with 1000 ng/ml of either C5a (e) or C3a (f). (g) Plot summarizes the effects of C5a and C3a on TRPV1-mediated responses. The response ratio (A2/A1) was obtained for each cell by dividing the amplitude of the second capsaicin-induced [Ca2+]i response (A2) by that of the first one (A1). *P<0.05 and ***P<0.001 vs control. Data are presented as means ± SEM.

DISCUSSION

Evidence has shown that complement system is involved in various painful conditions [5,14,39]. In this study we enhanced the existing level of understanding using behavioral studies, primary afferent electrophysiology recordings and Ca2+ imaging in cultured DRG. Our behavioral results support the conclusion that C5a is nociceptive and causes mice to develop increased heat and mechanical responsiveness. The C3a fragment demonstrated similar robust effects on mechanical responses but not on heat responses when injected at similar doses. Using the in vitro skin-nerve preparation, we were able to demonstrate that C5a and C3a cause A- but not C-nociceptor activation. In contrast, both C5a and C3a sensitized C-nociceptors but not A-nociceptors to heat. Neither complement fragment had a direct effect on mechanical responses. In cultured DRG neurons, both C5a and C3a sensitize responses to capsaicin.

Behavioral responses

In the present study, spontaneous pain behaviors tended to be greater in animals that received C5a or C3a injections, but these differences were not significant. Spontaneous pain caused by C5a and C3a was not prominent in previous human studies; only 0 of 17 and 1 of 9 healthy subjects noted pain sensation after intradermal injection of C5a and C3a (0.4 – 600 ng), respectively [45,46]. In our studies, heat hyperalgesia was observed after injection of C5a, which was induced within 30 min and remained for over 2 h after injection. The extent of the increased heat response was comparable to that elicited by injection of some other inflammatory mediators like bradykinin, nerve growth factor and prostaglandin E2 [4,32]. Injection of C3a, which is known to be less potent than C5a in chemotactic activity, was not effective in eliciting heat hyperalgesia; however, only a single though comparatively high dose was tested in this study. Mechanical hyperalgesia following local injection of C5a observed in the present study is in accordance with previous studies by others [26,39]. We also observed similar mechanical hyperalgesia after injection of C3a. Our observation, however, that injection of C5a 10 ng does not increase mechanical response is in disagreement with one previous study, in which a lower dose, 0.4 ng, decreased paw withdrawal threshold significantly [26]. This discrepancy might be due to species differences, vehicle or type of mechanical stimulus used. Also, in the present study, the testing site was not invaded by the needle used for drug injection to minimize mechanical trauma, and the experimenter was blinded to drug and dose.

Nociceptor activation and sensitization

In the present study, spontaneous activity was significantly increased in 25% and 18% of A-nociceptors by application of C5a and C3a, respectively. Similar excitation of A-nociceptors has been observed after application of inflammatory mediators such as bradykinin, which excited 28% of Aδ-fibers in rat skin-nerve preparation [24]. Although the discharge rate was high in some cases [24], the complement-induced activation rate was typically greater than bradykinin-induced activity. In contrast to A-nociceptors, C-nociceptors were not excited by C5a and only one C-nociceptor was excited by C3a application in the doses and times tested in the present study. The mechanism for activation of A-fibers by C5a and C3a are not known. Others have suggested excitation of nociceptors occurs by lowering the threshold temperature below bath or skin temperature [34,37]. However, activation of A-fibers does not appear to be related to heat responsiveness because they had high threshold to heat even after application of C5a or C3a.

The sensitization of primary afferent C-nociceptors to heat was prominent after exposure to C5a and C3a, as evidenced by lowered response threshold to heat and increased action potentials during and after heat stimulation. No such changes, however, were detected in A-nociceptors after exposure to C5a and C3a. The increased proportion of heat responsive C-nociceptors was also observed following C5a application. It can not be determined if heat insensitive fibers acquired sensitivity to heat, or fibers that had high thresholds above 45°C became detectable within our testing range by a decrease in threshold.

TRPV1 sensitization might be a possible mechanism for C-nociceptor sensitization to heat by C5a and C3a, as TRPV1 is predominantly expressed in C-nociceptors and is required for the generation of heat hyperalgesia [20]. We also could observe that C5a and C3a facilitate capsaicin-induced [Ca2+]i responses suggesting that TRPV1 is modulated by complement fragments (Fig. 7). C5a-induced sensitization of C-nociceptors to heat is similar to that induced by other inflammatory mediators. For example, single fiber recordings in a skin-nerve preparation showed that bradykinin decreases the threshold and increases the maximal discharge frequency to heat [22], and changes some heat unresponsive C-fibers to heat responsive [29]. Bradykinin changes properties of TRPV1 so that it can be activated by lower temperature [4,37]. Other substances including prostaglandin E2 and chemokines cause TRPV1 to be sensitized [19,31]. The C5a-induced C-nociceptor sensitization to heat may account for heat hyperalgesia induced by C5a injection. However, the involvement of other heat sensors except for TRPV1 also should be considered for nociceptor sensitization to heat, because some previous studies have suggested that TRPV1 is contained in a minority of cutaneous nociceptors [3] and mechanically sensitive cutaneous C-fibers lack TRPV1 staining [25]. In this case, TRPV1 may contribute to heat hyperalgesia by C5a and C3a through mechanically insensitive fibers. C3a did not produce significant heat hyperalgesia in behavioral test but did produce heat sensitization of C-nociceptors. This may be due to insufficient dose of C3a or lower potency relative to C5a.

In contrast to heat sensitization, no changes in A- and C-nociceptors were observed in response to mechanical stimuli after exposure to C5a and C3a. Relatively little evidence is available on mechanical sensitization of nociceptors in painful conditions including inflammation. In fact, previous studies have failed to detect mechanical sensitization by inflammatory mediators in vitro, with the exception of some reports [21]. However, in the present study, it should be noted that the lack of nociceptor sensitization to mechanical stimuli was observed 2 min after application of C5a or C3a, whereas mechanical hyperalgesia was measured after 30 min drug application. It is thus can not be excluded that longer exposure to C5a or C3a increase nociceptor sensitivity to mechanical stimuli. Alternatively, high frequency A-delta fiber activation by C5a or C3a could contribute to mechanical hyperalgesia by activating central neurons transmitting mechanical responses. Otherwise, other components, e.g. blood immune cells which can be recruited by complement fragments in vivo, could play an important role for C5a- and C3a-induced mechanical hyperalgesia. In support, C5a-induced mechanical hyperalgesia was dependent on the presence of polymorphonuclear leukocytes [26], which may not be present in the in vitro preparation.

Direct vs indirect effects

The presence of receptors for C5a and C3a has been detected in the central nervous system [7,8,33,40], and activation of these receptors in some central neurons results in increased [Ca2+]i and inward membrane currents [8,33]. Likewise, in the present study, we could observe the presence of C5aR mRNA and elevated [Ca2+]i responses by C5a and C3a in DRG neurons, supporting the possibility that activation or sensitization by C5a and C3a is produced by direct binding to their receptors on the peripheral terminal of nociceptors. Although the complement-induced [Ca2+]i elevations were detected only in DRG neurons, we cannot completely rule out a potential involvement of microglia that signaled indirectly to the neurons without a rise in [Ca2+]i.

On the other hand, it is also possible that other inflammatory mediators induced by C5a and C3a treatments are involved in nociceptive behavior and nociceptor sensitization. Peripherally injected C5a and C3a may stimulate resident inflammatory cells, e.g. mast cells in the skin [17], and are also able to act as powerful chemoattractant to direct immune cells, e.g. neutrophils to the site of inflammation [12]. Activation of these immune cells results in release of a range of algogenic substances including histamine, tumor necrosis factor α, interleukins and others [12,31], that elicit heat and mechanical hyperalgesia when injected into hind paw [1,6,9,27,36,41,44]. It is thus conceivable that various inflammatory mediators are, at least in part, responsible for nociceptive behaviors elicited by intraplantar injection of C5a and C3a. Indeed, intradermal injection of C5a and C3a is characterized by dose dependent inflammatory reactions such as cutaneous wheel and flare in humans [38,45,46]. The involvement of inflammatory mediators can not be excluded also in the in vitro skin-nerve preparation. Although the blood supply which is the source of various inflammatory mediators is absent in the in vitro preparation, some resident mast cells and macrophages in the skin could contribute to the inflammatory responses and subsequent nociceptor sensitization to heat and excitation by C5a and C3a.

In summary, our results suggest that C5a and to a lesser extent C3a support nociception by directly and/or indirectly sensitizing or activating A- and C-nociceptors in the skin of normal mice. Key questions which remain unanswered are whether the sensitivity to complement is altered in perturbed tissue such as tissue surrounding incisions, and, if present, what the mechanism of the indirect sensitizing effects is. Finally, human trials may be considered in order to determine whether C5aR antagonists could be used to reduce pain in humans.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Department of Anesthesia at the University of Iowa and by National Institutes of Health (NIH), Bethesda, Maryland grant GM079126 to D.J.C and T.J.B. Y.M.U. was supported by the NIH Grant NS054614. There are no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Binshtok AM, Wang H, Zimmermann K, Amaya F, Vardeh D, Shi L, Brenner GJ, Ji RR, Bean BP, Woolf CJ, Samad TA. Nociceptors are interleukin-1beta sensors. J Neurosci. 2008;28(52):14062–73. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3795-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cholewinski A, Burgess GM, Bevan S. The Role of Calcium in Capsaicin-Induced Desensitization in Rat Cultured Dorsal Root Ganglion Neurons. Neuroscience. 1993;55(4):1015–23. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(93)90315-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Christianson JA, McIlwrath SL, Koerber HR, Davis BM. Transient receptor potential vanilloid 1-immunopositive neurons in the mouse are more prevalent within colon afferents compared to skin and muscle afferents. Neuroscience. 2006;140(1):247–57. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chuang HH, Prescott ED, Kong H, Shields S, Jordt SE, Basbaum AI, Chao MV, Julius D. Bradykinin and nerve growth factor release the capsaicin receptor from PtdIns(4,5)P2-mediated inhibition. Nature. 2001;411(6840):957–62. doi: 10.1038/35082088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Clark JD, Qiao Y, Li X, Shi X, Angst MS, Yeomans DC. Blockade of the complement C5a receptor reduces incisional allodynia, edema, and cytokine expression. Anesthesiology. 2006;104(6):1274–82. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200606000-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cunha FQ, Poole S, Lorenzetti BB, Ferreira SH. The pivotal role of tumour necrosis factor alpha in the development of inflammatory hyperalgesia. Br J Pharmacol. 1992;107(3):660–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1992.tb14503.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Davoust N, Jones J, Stahel PF, Ames RS, Barnum SR. Receptor for the C3a anaphylatoxin is expressed by neurons and glial cells. Glia. 1999;26(3):201–11. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-1136(199905)26:3<201::aid-glia2>3.0.co;2-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Farkas I, Varju P, Szabo E, Hrabovszky E, Okada N, Okada H, Liposits Z. Estrogen enhances expression of the complement C5a receptor and the C5a-agonist evoked calcium influx in hormone secreting neurons of the hypothalamus. Neurochem Int. 2008;52(4–5):846–56. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2007.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ferreira SH, Lorenzetti BB, Bristow AF, Poole S. Interleukin-1 beta as a potent hyperalgesic agent antagonized by a tripeptide analogue. Nature. 1988;334(6184):698–700. doi: 10.1038/334698a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ffrench-Constant C. Pathogenesis of multiple sclerosis. Lancet. 1994;343(8892):271–5. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(94)91118-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fosse E, Mollnes TE, Ingvaldsen B. Complement activation during major operations with or without cardiopulmonary bypass. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1987;93(6):860–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Frank MM, Fries LF. The role of complement in inflammation and phagocytosis. Immunol Today. 1991;12(9):322–6. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(91)90009-I. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gerard C, Gerard NP. C5A anaphylatoxin and its seven transmembrane-segment receptor. Annu Rev Immunol. 1994;12:775–808. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.12.040194.004015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Griffin RS, Costigan M, Brenner GJ, Ma CH, Scholz J, Moss A, Allchorne AJ, Stahl GL, Woolf CJ. Complement induction in spinal cord microglia results in anaphylatoxin C5a-mediated pain hypersensitivity. J Neurosci. 2007;27(32):8699–708. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2018-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Grynkiewicz G, Poenie M, Tsien RY. A new generation of Ca2+ indicators with greatly improved fluorescence properties. J Biol Chem. 1985;260(6):3440–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hahn-Pedersen J, Sorensen H, Kehlet H. Complement activation during surgical procedures. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1978;146(1):66–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hartmann K, Henz BM, Kruger-Krasagakes S, Kohl J, Burger R, Guhl S, Haase I, Lippert U, Zuberbier T. C3a and C5a stimulate chemotaxis of human mast cells. Blood. 1997;89(8):2863–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Heideman M. Complement activation in vitro induced by endotoxin and injured tissue. J Surg Res. 1979;26(6):670–3. doi: 10.1016/0022-4804(79)90063-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Huang J, Zhang X, McNaughton PA. Inflammatory pain: the cellular basis of heat hyperalgesia. Curr Neuropharmacol. 2006;4(3):197–206. doi: 10.2174/157015906778019554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Julius D, Basbaum AI. Molecular mechanisms of nociception. Nature. 2001;413(6852):203–10. doi: 10.1038/35093019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Koda H, Mizumura K. Sensitization to mechanical stimulation by inflammatory mediators and by mild burn in canine visceral nociceptors in vitro. J Neurophysiol. 2002;87(4):2043–51. doi: 10.1152/jn.00593.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Koltzenburg M, Kress M, Reeh PW. The nociceptor sensitization by bradykinin does not depend on sympathetic neurons. Neuroscience. 1992;46(2):465–73. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(92)90066-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Koplas PA, Rosenberg RL, Oxford GS. The role of calcium in the desensitization of capsaicin responses in rat dorsal root ganglion neurons. J Neurosci. 1997;17(10):3525–37. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-10-03525.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lang E, Novak A, Reeh PW, Handwerker HO. Chemosensitivity of fine afferents from rat skin in vitro. J Neurophysiol. 1990;63(4):887–901. doi: 10.1152/jn.1990.63.4.887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lawson JJ, McIlwrath SL, Woodbury CJ, Davis BM, Koerber HR. TRPV1 unlike TRPV2 is restricted to a subset of mechanically insensitive cutaneous nociceptors responding to heat. J Pain. 2008;9(4):298–308. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2007.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Levine JD, Gooding J, Donatoni P, Borden L, Goetzl EJ. The role of the polymorphonuclear leukocyte in hyperalgesia. J Neurosci. 1985;5(11):3025–9. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.05-11-03025.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lewin GR, Ritter AM, Mendell LM. Nerve growth factor-induced hyperalgesia in the neonatal and adult rat. J Neurosci. 1993;13(5):2136–48. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.13-05-02136.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liang D, Li X, Lighthall G, Clark JD. Heme oxygenase type 2 modulates behavioral and molecular changes during chronic exposure to morphine. Neuroscience. 2003;121(4):999–1005. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(03)00483-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liang YF, Haake B, Reeh PW. Sustained sensitization and recruitment of rat cutaneous nociceptors by bradykinin and a novel theory of its excitatory action. J Physiol. 2001;532(Pt 1):229–39. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.0229g.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Linton SM, Morgan BP. Complement activation and inhibition in experimental models of arthritis. Mol Immunol. 1999;36(13–14):905–14. doi: 10.1016/s0161-5890(99)00113-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Marchand F, Perretti M, McMahon SB. Role of the immune system in chronic pain. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2005;6(7):521–32. doi: 10.1038/nrn1700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Moriyama T, Higashi T, Togashi K, Iida T, Segi E, Sugimoto Y, Tominaga T, Narumiya S, Tominaga M. Sensitization of TRPV1 by EP1 and IP reveals peripheral nociceptive mechanism of prostaglandins. Mol Pain. 2005;1:3. doi: 10.1186/1744-8069-1-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.O’Barr SA, Caguioa J, Gruol D, Perkins G, Ember JA, Hugli T, Cooper NR. Neuronal expression of a functional receptor for the C5a complement activation fragment. J Immunol. 2001;166(6):4154–62. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.6.4154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Reeh PW, Petho G. Nociceptor excitation by thermal sensitization--a hypothesis. Prog Brain Res. 2000;129:39–50. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(00)29004-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schnizler K, Shutov LP, Van Kanegan MJ, Merrill MA, Nichols B, McKnight GS, Strack S, Hell JW, Usachev YM. Protein kinase A anchoring via AKAP150 is essential for TRPV1 modulation by forskolin and prostaglandin E2 in mouse sensory neurons. J Neurosci. 2008;28(19):4904–17. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0233-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schuligoi R, Donnerer J, Amann R. Bradykinin-induced sensitization of afferent neurons in the rat paw. Neuroscience. 1994;59(1):211–5. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(94)90111-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sugiura T, Tominaga M, Katsuya H, Mizumura K. Bradykinin lowers the threshold temperature for heat activation of vanilloid receptor 1. J Neurophysiol. 2002;88(1):544–8. doi: 10.1152/jn.2002.88.1.544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Swerlick RA, Yancey KB, Lawley TJ. Inflammatory properties of human C5a and C5a des Arg/in mast cell-depleted human skin. J Invest Dermatol. 1989;93(3):417–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ting E, Guerrero AT, Cunha TM, Verri WA, Jr, Taylor SM, Woodruff TM, Cunha FQ, Ferreira SH. Role of complement C5a in mechanical inflammatory hypernociception: potential use of C5a receptor antagonists to control inflammatory pain. Br J Pharmacol. 2008;153(5):1043–53. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0707640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Van Beek J, Bernaudin M, Petit E, Gasque P, Nouvelot A, MacKenzie ET, Fontaine M. Expression of receptors for complement anaphylatoxins C3a and C5a following permanent focal cerebral ischemia in the mouse. Exp Neurol. 2000;161(1):373–82. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1999.7273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wacnik PW, Eikmeier LJ, Simone DA, Wilcox GL, Beitz AJ. Nociceptive characteristics of tumor necrosis factor-alpha in naive and tumor-bearing mice. Neuroscience. 2005;132(2):479–91. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2004.12.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ward PA. The dark side of C5a in sepsis. Nat Rev Immunol. 2004;4(2):133–42. doi: 10.1038/nri1269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wetsel RA. Structure, function and cellular expression of complement anaphylatoxin receptors. Curr Opin Immunol. 1995;7(1):48–53. doi: 10.1016/0952-7915(95)80028-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Woolf CJ, Allchorne A, Safieh-Garabedian B, Poole S. Cytokines, nerve growth factor and inflammatory hyperalgesia: the contribution of tumour necrosis factor alpha. Br J Pharmacol. 1997;121(3):417–24. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0701148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wuepper KD, Bokisch VA, Muller-Eberhard HJ, Stoughton RB. Cutaneous responses to human C 3 anaphylatoxin in man. Clin Exp Immunol. 1972;11(1):13–20. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yancey KB, Hammer CH, Harvath L, Renfer L, Frank MM, Lawley TJ. Studies of human C5a as a mediator of inflammation in normal human skin. J Clin Invest. 1985;75(2):486–95. doi: 10.1172/JCI111724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]