Abstract

Replacement of the ancillary ligand in titanocene dichloride by amino acids provides titanocene species with high water solubility. As part of our research efforts in the area of titanium-based antitumor agents, we have investigated the cytotoxic activity of Cp2TiCl2 and three water soluble titanocene-amino acid complexes—[Cp2Ti(aa)2]Cl2 (aa = L-cysteine, L-methionine, and D-penicillamine) and one water soluble coordination compound, [Ti4(maltolato)8(μ-O)4] on the human colon adenocarcinoma cell line, Caco-2. At pH of 7.4 all titanocene species decompose extensively while [Ti4(maltolato)8(μ-O)4] is stable for over seven days. In terms of cytotoxicity, the [Cp2Ti(aa)2]Cl2 and [Ti4(maltolato)8(μ-O)4] complexes exhibited slightly higher toxicity than titanocene dichloride at 24 hours, but at 72 hours titanocene dichloride and [Ti4(maltolato)8(μ-O)4] have higher cytotoxic activity. Cellular Titanium uptake was quantified at various time intervals to investigate the possible relationship between Ti uptake and cellular toxicity. Results indicated that there was not a clear relationship between Ti uptake and cytotoxicity. A structure-activity relationship is discussed.

Keywords: Caco-2 cell, colon cancer, titanocene dichloride, maltol

1. Introduction

The first non-platinum complex tested in clinical trials as antitumor agent was cis-[(CH3CH2O)2(bzac)2Ti(IV)], Scheme I. This complex is active against a wide variety of ascites and solid tumors [1-3]. Other cis-[X2(bzac)2Ti(IV)] complexes have been investigated exhibiting similar biological activity as the ethoxide complex. However, the interest for non-platinum complex was at a slow pace due to the remarkable and well-reputed antitumor properties of cis-platin. The discovery of metallocene-based organometallic anticancer agent, Cp2TiCl2, in 1979 by Köpf and Köpf-Maier [4] stimulated much interest to investigate other non-platinum complexes with different mechanism of cancinostatic activity.

Scheme I.

Structure of cis-[(CH3CH2O)2(bzac)2Ti(IV)].

Immediately, in the following years, other metallocenes with the general formula Cp2MX2, (Scheme II), (M = Ti, V, Nb, Mo; X = halides and pseudo-halides), CpFe+X−, main group (C5R5)2M (M = Sn, Ge; R = H, CH3) and ionic [Cp2TiL2]2+[Y]2 (L = anionic ligand, amino acid) have been synthesized and investigated for antitumor activity [5-10]. In general, these complexes demonstrated to be efficient antineoplastic agents with less toxic effect than the well-reputed cis-platin [5-10]. Among all the metallocenes tested, Cp2TiCl2 was the most active reaching phase I and II clinical trials [11-15]. However, titanocene dichloride is unstable at physiological pH due to extensive hydrolysis [16]. To circumvent this, Cp2TiCl2 is dissolved in Me2SO/H2O (saline) mixture for in vivo experiments [5-10]. Nevertheless, many mechanistic details are unknown, which hinders its use as a chemotherapeutic agent.

Scheme II.

Structure of metallocenes dihalide.

Modification of ligands in titanocene dichloride is an active area of research since, among the metallocenes, titanocene dichloride is the most effective species [17-40]. The modification on the Cp rings and ancillary ligands are aimed to improve antitumor activity and water solubility. On way to improve titanocene water solubility is to replace the chloride group for hydrophilic ligands such as amino acids [5-10, 31]. Another approach is to synthesize robust, water stable Ti(IV) species coordinated by oxygen containing ligands. In this regard, we have synthesize [Ti4(maltolato)8(μ-O)4] (maltolato = 3-hydroxy-2-methyl-4-pyronato) complex which is stable at and above physiological pH [41]. As part of our research efforts, we have studied the cytotoxic activity and cellular uptake of two types of titanocene derivatives and the [Ti4(maltolato)8(μ-O)4] compound on the colon cancer cell line, Caco-2.

Caco-2 cells are human colon carcinoma cells that are able to express differentiation features of mature intestinal cells [42]. It is an excellent model to study intestinal drug absorption and metabolism since Caco-2 cells express most drug transporters of the intestine [42]. Currently, this cell line is being used in many pharmaceutical companies as an initial screening test. Therefore, we have examined the cytotoxic activities and titanium uptake of the subject complexes in Caco-2 cells line. To our knowledge, this is the first report on cytotoxic properties and cellular uptake of Ti(IV) complexes on colon cancer cells.

2. Experimental

2.1 Methods and Materials

Titanocene dichloride salts were handled under dried nitrogen in Schlenk anaerobic lines. Cp2TiCl2 was obtained from Aldrich and used without further purification. [Cp2Ti(L-cysteine)2]Cl2, [Cp2Ti(D-penicillamine)2]Cl2, [Cp2Ti(L-methionine)2]Cl2 and [Ti4(maltolato)8(μ-O)4] were prepared by published procedures [31,41]. The purity of titanium complexes was checked by IR and/or by 1H NMR spectroscopy.

2.2 Physical Measurements

FTIR spectra were recorded on a Bruker Vector-22 spectrophotometer with the samples as compressed KBr pellets. 1H spectra were recorded on a 300 MHz Varian Gemini and 500 MHz Avance Bruker spectrometers under controlled temperature. TPPS was inserted in a sealed capillary tube inside the NMR tube and used as an internal reference.

2.3 Cell Culture

Caco-2 cells were purchased from the American Tissue Culture Collection (Rockville, MD). The cells were cultivated on 75 cm2 flasks (Beckman Diagnostics, Franklin Lakes, NJ) using Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium (DMEM) (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (Life Technologies, Gaithersburg, MD), 1% nonessential amino acids (Life Technologies, Gaithersburg, MD), 100 units/mL of penicillin, and 100 μ/mL streptomycin (Sigma, St. Louis, MO). Cells were maintained on a controlled atmosphere at 37°C, 95% relative humidity, and 5% CO2. Culture medium was changed every other day for approximately 5-6 days until cells reached approximately 80-90% confluency.

2.3.1 Cytotoxicity studies

The biological activity was determined using the CellTiter-Blue™ assay. Cells with a concentration of 10,000 cells/cm2 were seeded in 96 well assay plates with an area of 0.71 cm2/well (3603, Costar, Corning, NY)). They were cultivated at 37° C and 5% of CO2 in Dulbecco's Modified Eagle's Medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). Prior to the doubling time, cells were washed twice with Hank's Balanced Salts (HBSS) (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) to remove the phenol red containing culture media and samples were placed. DMEM was used as a negative control and 1.5% hypochlorite solution was used as a positive control. Samples were prepared to contain the desired concentration of [Ti4(maltolato)8(μ-O)4], titanocene-D-penicillamine, titanocene-L-methonine, and titanocene-L-cysteine using a concentration range between 312.5 μM to 2500 μM. Titanocene dichloride, was used as a comparison known drug model and was tested in the concentration range between 19.53 μM to 2500 μM. Cells were incubated for 2, 24 and 72 hours with the drugs. After the end of the contact period, solutions were removed. The cells were allowed to recuperate until a total of one week of cultivation was achieved. At this point, cells were washed and incubated at 37° C with CellTiter-Blue (Promega, Madison, WI) for the appropriate time. Cell viability was analyzed with a spectrofluorometer (SpectraMax Gemini EM, Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA) by measuring the fluorescence emitted with an excitation of 560 nm and an emission of 590 nm. Wells with a high concentration of viable cells possessed the highest fluorescence. Cytotoxicity results (obtained from sixteen independent measurements) were presented by normalizing all the relative fluorescent unit values with the relative fluorescent unit value of the negative control (cells with DMEM). Concentrations of compounds required to inhibit cell proliferation by 50% (IC50) were calculated by fitting data to a four-parameter logistic plot by means of the SigmaPlot software from SPSS.

2.4 Quantitative Study of Titanium Cellular Uptake by Inductive Coupled Plasma Atomic Emission Spectroscopy

Cells at a concentration of 50,000 cells/cm2 were seeded in sterile 6 well plate (3502, Falcon, Corning, NY) and cultivated for one week in supplemented DMEM with phenol red at 37° C and 5% of CO2. After one week of cultivation, the cells were placed in contact with drug solutions with a concentration of 312.5?μM. This concentration was found to be non toxic for aforementioned cells for all the compounds. Solutions were prepared in DMEM for and placed in contact with the cells for 5, 24, 48, 72hr. The compound's solution was then removed and the cells were rinsed with ice-cold BRS to removed excess drug. The cell monolayer was trypsinized for 20 minutes in the incubator at 37° C. Detached cells were counted and then centrifuged. The resulting pellet was solubilized with 0.5% Triton-X 100 (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) in BRS for 30 minutes at 37 °C. Finally, BRS was added to a final volume of 1 mL. The samples were analyzed using Inductive Couple Plasma Mass Spectrometer (7500, Agilent, CA).

2.5 Ethidium bromide displacement assay by Fluorescence spectroscopy

A 6.6 × 10−6 M lyophilized Calf thymus DNA (Sigma) solution was freshly prepared in RNase- and DNase-free water. Prior to the interactions, the titanium-maltolato complex's fluorescence was verified to be non-existent in aqueous solution. Ethidium bromide was added to a final concentration of 6.31 × 10−7 M. The titanium-maltolato complex was added to a 1:1 ratio with EtBr and spectra were recorded every ten minutes for one hour. The experiment was performed with the complex to EtBr ratio at 2:1 and 45:1 and all measurements were recorded at 28°C. No changes in the fluorescence were observed at all ratios studied.

2.6 Titanium-maltolato complex interaction with DNA monitored by 1 H-NMR spectroscopy

The titanium-maltolato complex was dissolved in 25 mM Tris-d11 / 10 mM NaCl (D2O) buffer at pH 7.4 to a concentration of 1.05×10−4 M for each (monomer and tetramer). The resulting solution had a tetramer:monomer 1:1 ratio and the pH was 7.4 which was not adjusted. To the titanium-maltolato solution was added aliquots of 50 μL of DNA, 3.1 × 10−5 M (in mM Tris-d11 / 10 mM NaCl (D2O) buffer at pH 7.4) at room temperature and the spectra recorded after each aliquot.

3. Results and Discussion

The syntheses of these three new water soluble titanocene-amino acid complexes ([Cp2TiL2]Cl2, L = L-cysteine, D-penicillamine and L-methionine) and [Ti4(maltolato)8(μ-O)4] have been previously reported [31,41], but this is the first report on the cytotoxic properties and titanium cellular uptake of these species in the colon cancer Caco-2 cell line. The titanocene-amino acid complexes have been previously characterized by 1H and IR spectroscopy and the amino acids are engaged in Ti-O(carboxylate) coordination, according to the structure presented in Figure 1. [Ti4(maltolato)8(μ-O)4] has been characterized crytallographically [41]. It is a tetranuclear species containing bridging oxygens forming a Ti4O4 cyclic unit, see Supplementary Material.

Figure 1.

Proposed structure for titanocene-aminoacid complexes.

Previous kinetic studies in water, at pH = 3, showed that [Cp2TiL2]Cl2, L = L-cysteine and L-methionine) complexes are less stable than titanocene dichloride while [Cp2Ti(D-penicillamine)2]Cl2 has similar stability to Cp2TiCl2 [31]. However, increasing the pH to 7.4 leads to the formation of a yellow solution, which eventually vanishes. Further decomposition was observed as evidenced by the formation of cloudiness. Similar results were reported by Marks and co-workers where they proposed the formation of a series of titanium species such as Ti(Cp)0.31O0.30(OH) [16]. Further decomposition of this species into TiO2, at high pH, has been proposed [16].

The scenario is different for [Ti4(maltolato)8(μ-O)4]. This species is very stable at pH of 7.4 and above, under buffer conditions, without any detectable decomposition [41]. The Ti-O octahedral coordination sphere and the bulkiness of the maltol ligands could be responsible for its stability. Therefore, formation of TiO2 can be ruled out.

The in vitro cytotoxicity of the titanocene-aminoacids, titanocene dichloride and [Ti4(maltolato)8(μ-O)4] in Caco-2 cell line was determined using the commercially available cell viability assay (Cell Titer-Blue from Promega) at 24 and 72 hours drug exposure period. Titanium complexes were tested in concentrations that ranged from 313-2500 μ . Initial cytotoxic studies at 2 hours drug exposure were performed in concentrations between 0.01-10 mM to find the IC50 range. Since titanocene dichloride has a longer intracellular activation period, it is usually tested at a time interval of 72 hours, as was done in our study. Table I summarizes the IC50 data for the titanocene complexes.

Table I.

IC50 values for the complexes studied in the Caco-2 cell line, determined using the available cell viability assay Cell Titer-Blue. IC values are the average of sixteen independent measurements.

| Complex | IC50 (mM) | |

|---|---|---|

| 24h | 72h | |

| Cp2TiCl2 | 6.9(6) | 0.109(8) |

| [Cp2Ti(L-cysteine)2]Cl2 | 2.9(6) | 1.7(3) |

| [Cp2Ti(L-methionine)2]Cl2 | 3.16(1) | 1.2(8) |

| [Cp2Ti(D-penicillamine)2]Cl2 | 3.29(0) | 1.193(1) |

| [Ti4(maltolato)8(μ-O4)] | 2.50(5) | 0.214(5) |

Upon examination of Table I it is evident that all the titanocene-amino acid and [Ti4(maltolato)8(μ-O)4] complexes demonstrated slightly higher cytotoxic activity than titanocene dichloride (Cp2TiCl2) at 24 hours drug exposure. However, the apparent (albeit slight) enhancement in cytotoxicity by replacing the chlorides by sulfur-containing amino acids or by [Ti4(maltolato)8(μ-O)4] is not significant since all the IC50 values have the same order of magnitude.

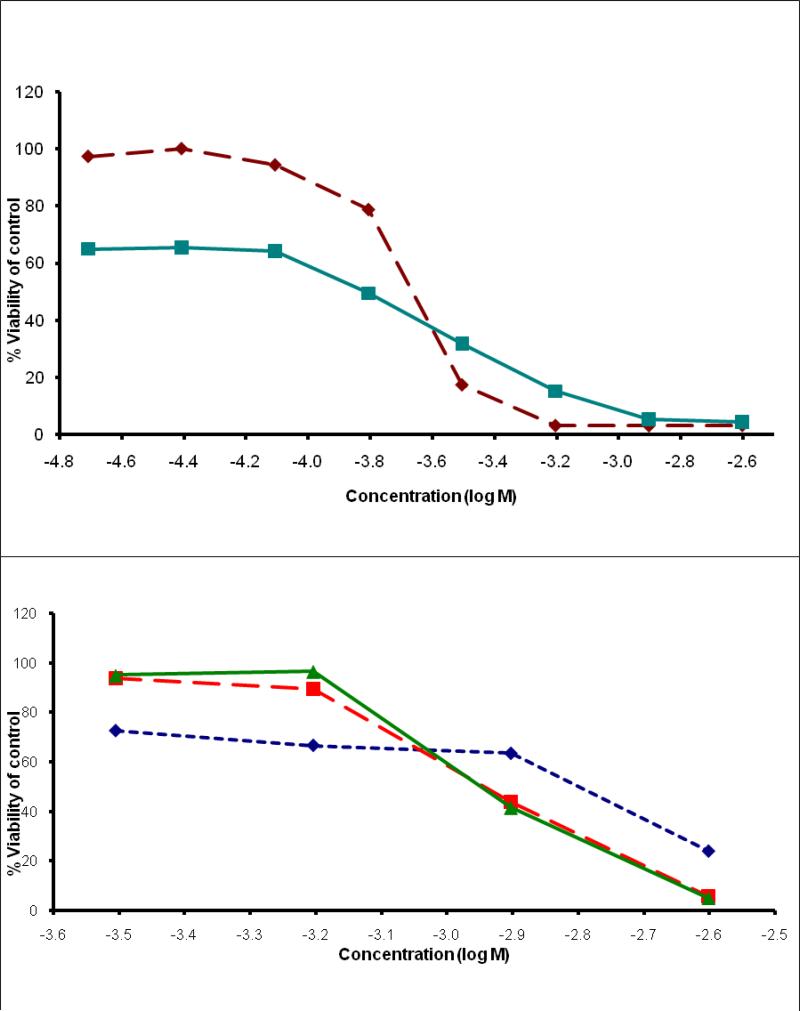

The cytotoxicity studies were performed at longer drug exposure period of 72 hours. Figure 2 presents the IC50 curves for the complexes at 72 hours of drug exposure. This time period is sufficient to allow titanocene dichloride to express its biological activity. In general, it is clear that all the titanocene complexes as well as [Ti4(maltolato)8(μ-O)4] showed somehow enhanced cytotoxic activity at 72 hrs as compared to 24 hrs. Furthermore, titanocene dichloride and [Ti4(maltolato)8(μ-O)4] showed to be one order of magnitude more cytotoxic than titanocene-aminoacid complexes. The cytotoxicities of titanocene dichloride and [Ti4(maltolato)8(μ-O)4] at 72 hours are also one order of magnitude higher than their cytotoxicities at 24 hours.

Figure 2.

Dose response curves of top: [Cp2Ti(L-cysteine)2]Cl2 (diamonds), [Cp2Ti(L-methionine)2]Cl2 (triangles) and [Cp2Ti(D-penicillamine)2]Cl2 (squares); bottom: Cp2TiCl2 (squares) and [Ti4(maltolato)8(μ-O4)] (diamonds) against Caco-2 cell line at 72 hours drug exposure, determined using cell viability assay Cell Titer-Blue.

In order to correlate and understand the cytotoxic responses of these titanium complexes as function of structure, we monitored the titanium uptake process on Caco-2 cell line at different drug exposure times using Inductive Coupled Plasma-Atomic Emission Spectroscopy (ICP-AES). Three representative complexes were studied: Cp2TiCl2, [Cp2Ti(D-cysteine)2]Cl2 and [Ti4(maltolato)8(μ-O4)]. The Ti uptake by Caco-2 cell line was measured at 5, 24, 48 and 72 hours (drug exposure), see Table II and Figure 3. Upon examination of Table II, it can be observed that [Ti4(maltolato)8(μ-O4)] has the higher Ti uptake by Caco-2 cells at 5 and 24 hours but it decreases at longer times. On the other hand, [Cp2Ti(D-cysteine)2]Cl2 and Cp2TiCl2 showed a constant increase in Ti uptake as time evolved. [Cp2Ti(D-cysteine)2]Cl2 showed higher cellular uptake by Caco-2 cells when compared to titanocene dichloride. Interestingly, the Ti uptake quantified for the three titanium complexes demonstrated no correlation to their cytotoxic activities. For instance at 72 hours of drug exposure, [Cp2Ti(D-cysteine)2]Cl2 has the highest IC50 value (lower cytotoxic activity) than Cp2TiCl2 and [Ti4(maltolato)8(μ-O4)] but its Ti concentration on Caco-2 cells is higher.

Table II.

Titanium uptake by Caco-2 colon cancer cells. Concentration values are average of three independent experiments, expressed as pg Ti/cell. Std in parenthesis.

| Exposure time | 5 hrs | 24 hrs | 48 hrs | 72 hrs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compound | [pgTi/cell] | [pgTi/cell] | [pgTi/cell] | [pgTi/cell] |

| Cp2TiCl2 | 0.016(2) | 0.032(5) | 0.049(2) | 0.066(7) |

| [Cp2Ti(cysteine)2]Cl2 | 0.116(2) | 0.203(2) | 0.27(2) | 0.31(2) |

| [Ti4(maltolato)8(μ-O4)] | 0.144(2) | 0.3(1) | 0.11(1) | 0.17(1) |

Figure 3.

Comparison of intracellular titanium uptake by Caco-2 cells. Cp2TiCl2 (triangles), [Cp2Ti(cysteine)2]Cl2 (squares) and [Ti4(maltolato)8(μ-O4)] (diamonds).

The Ti uptake on Caco-2 cell by [Ti4(maltolato)8(μ-O4)] deserves especial attention. At shorter period of drug exposure it has the higher Ti uptake but as we increase the drug exposure time the amount of Ti uptaken by Caco-2 cells decreases. This suggests that [Ti4(maltolato)8(μ-O4)] interaction inside the cell is weak and must likely reversible and as a result the cell metabolize and remove titanium from the cell. This result is in agreement with the structural features of [Ti4(maltolato)8(μ-O4)], as described below.

[Ti4(maltolato)8(μ-O4)] is a tetranuclear species, inert, water stable and it is not uptaken by transferrin as do the titanocene complexes [31]. This implies that [Ti4(maltolato)8(μ-O4)] enters into the cell as a tetranuclear species and since its coordination sphere is saturated, it can partially intercalate between DNA bases rather than undergoing DNA (phosphate and nitrogen) coordination. In fact, the distance between the adjacent maltol rings is 3.6 Å which can be envisioned to intercalate within the DNA bases but its interaction is weak. To explore this possibility, we performed [Ti4(maltolato)8(μ-O4)]-DNA interaction studies using 1H NMR spectroscopy.

At physiological pH, [Ti4(maltolato)8(μ-O4)] is the predominant species, but since Ti(maltolato)2(OH)2 may exist as a minor product, the 1H NMR spectroscopic DNA binding interaction studies were performed in a sample that contained both the monomeric and tetrameric species at pH of 7.4 in Tris-d11 buffer, using calf-thymus DNA as a model. Upon addition of calf-thymus DNA into the Ti-maltol solution, (Figure 4), we observed that the maltol signals H-5 and H-6 of the tetrameric species broadened and move upfield and then collapsed into the baseline, while the monomeric species remained intact. This strongly suggests that [Ti4(maltolato)8(μ-O4)] is intercalating between the DNA bases. However, the intercalation is weak since in fluorescence spectroscopy experiments [Ti4(maltolato)8(μ-O4)] was not able to replace ethidium bromide from calf-thymus DNA.

Figure 4.

1H NMR binding studies of [Ti4(maltolato)8(μ-O4)] and its monomeric species with calf-thymus DNA in 25 mM Tris-d11 / 10 mM NaCl (D2O) buffer at pH 7.4 and room temperature. A) mixture of 1:1 monomer:tetramer, b) after addition of 50 μL of DNA c) after addition of 100 μL of DNA.

Thus, this data could explain why [Ti4(maltolato)8(μ-O4)] is removed from the cell at long drug exposures (48 and 72 hours). Finally, the monomeric species does not show any interaction with calf-thymus DNA since it is coordinatively saturated and does not contain parallel rings separated by 3.6 Å.

4. Concluding remarks

In this study, we have presented the cytotoxicity and Ti uptake on the Caco-2 cell line of a selected group of titanocene complexes (three highly water soluble titanocene-aminoacid complexes and slightly soluble titanocene dichloride) and a robust coordination compound [Ti4(maltolato)8(μ-O4)]. Titanocene-aminoacid species as well as titanocene dichloride are considerably stable in water as long as the pH is kept below 3. Thus, even though the aminoacid ligand imparts water solubility to their complexes, it does not necessarily impart more long term hydrolytic stability at low pH. At physiological pH all complexes degrade substantially. What possible effects will induce the presence of an aminoacid as ancillary ligand and their outcome in terms of cytotoxicity? We can infer that the increased solubility of [Cp2Ti(aa)2]Cl2 species make them slightly more accessible to the cells and slightly more cytotoxic. Apparently, this scenario applies at least at 24 hours of drug exposure. At 72 hours of drug exposure, Cp2TiCl2 is more cytotoxic than [Cp2Ti(aa)2]Cl2 species and slightly more cytotoxic than [Ti4(maltolato)8(μ-O4)]. On the other hand, [Ti4(maltolato)8(μ-O4)], a highly soluble and robust species at physiological conditions demonstrated to be more active at shorter drug exposure period but less active than titanocene dichloride at 72 hours. The initial response on [Ti4(maltolato)8(μ-O4)] at 24 hours could be explained as a result of higher content of Ti/cell but in marked contrast, its IC50 value continues to decrease (improving its cytotoxicity) at 72 hours even though the concentration of Ti/cell decreases. Thus there is no simple correlation between cytotoxic activity and Ti uptake by Caco-2 cells. On the other hand, titanocene dichloride showed less concentration of Ti/cell than [Cp2Ti(D-cysteine)2]Cl2 at all time intervals (5, 24, 48, 72 hrs) but at 72 hours exhibited higher cytotoxic activity. Second, in contrast to [Ti4(maltolato)8(μ-O)4], both titanocene dichloride and [Cp2Ti(D-cysteine)2]Cl2 continue to increase the Ti uptake/cell as time evolves and their cytotoxic activities improve along.

Comparing titanocene dichloride versus [Cp2Ti(D-cysteine)2]Cl2, the fact that the Caco-2 cell line is known to express cation membrane transporters (also express most drug transporters of the intestine) [42,43] could explain these differences, because even though both, Cp2TiCl2 and [Cp2Ti(aa)2]Cl2, complexes are expected to form cationic species, their stabilities in water are different. We may invoke the formation of [Cp2Ti(aa)2]2+ versus [Cp2Ti(OH)Cl]+ or [Cp2Ti(H2O)(OH)]+, keeping in mind that these species predominate at low pH. The difference in Ti uptake may rely in the amon oacid ligands. They are weakly coordinated to Ti(IV) and as a result, the titanocene-amino acid complex is more unstable, and it becomes coordinatively unsaturated easily, forming rapidly [Cp2Ti(aa)2]2+. Although at physiological pH species like Ti(Cp)0.31O0.30(OH) will predominate [16], the small amount of [Cp2Ti(aa)2]2+ that remain in solution will be more effectively transported inside the cells than the remaining amount of [Cp2Ti(OH)Cl]+ or [Cp2Ti(H2O)(OH)]+, as a result of its di-cationic nature. In any event, with this experimentation we cannot elucidate the mechanistic details of their cytotoxicity. But what our experimental results showed is that there is no correlation between Ti uptake on Caco-2 cell line and the cytotoxicity of the titanium complexes. Also, the water solubility as a vital property for these complexes to improve the antiproliferative activity remains questionable.

To our knowledge, there are no previous studies on Ti uptake by cancer cells using titanocenes. There is one report on molybdenocenes where Mo uptake by cancer cells is monitored by atomic absorption [44]. Harding and co-workers found that there is no correlation between the amount of molybdenum uptaken by the cancer cells and cytotoxicity. Also, there is no correlation between the molybdenocene hydrophobic character and cytotoxic activity. We have found similar results with Ti(IV) complexes.

Supplementary Material

Ackowledgement

E.M. acknowledges the NIH-MBRS SCORE Programs at the University of Puerto Rico Mayagüez for financial support and NSF-MRI for providing funds for the purchase of the 500 MHz NMR.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Keppler BK, Friesen C, Moritz HG, Vongerichten H, Vogel E. Tumor-InhibitingBis(b-Diketonato)Metal Complexes. Butotitane, cis-Diethoxybis(1-phenylbutane-1,3-dionato) titanium(IV). Struct. Bonding. 1991;78:97–127. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Clarke MJ, Zhu F, Frasca DR. Non-Platinum Chemotherapeutic Metallopharmaceuticals. Chem. Rev. 1999;99:2511–2553. doi: 10.1021/cr9804238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schilling T, Keppler BK, Heim ME, Niebch G, Dietzfelbinger H, Rastetter J, Hanauske AR. Clinical phase I and pharmacokinetic trial of the new titanium complex budotitane. Invest. New Drugs. 1996;13:327–322. doi: 10.1007/BF00873139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Köpf H, Köpf-Maier P. Titanocene Dichloride-The First Metallocene with Cancerostatic Activity. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 1979;18:477–478. doi: 10.1002/anie.197904771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Köpf-Maier P. Complexes of metals other than platinum as antitumor agents. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 1994;47:1–16. doi: 10.1007/BF00193472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Köpf-Maier P, Köpf H. Transition and Main Group Metal Cyclopentadienyl Complexes: Preclinical Studies on a Series of Antitumor Agents of Different Structural Type. Structure and Bonding. 1988;70:103–185. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Köpf-Maier P, Köpf H. Non-Platinum-Group Metal Antitumor Agents. Chem. Rev. 1987;87:1137–1152. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Köpf-Maier P, Köpf H. In: Metal Compounds in Cancer Therapy, Organometallic Titanium, Vanadium, Niobium, Molybdenum and Rhenium Complexes - Early Transition Metal Antitumor Drugs. Fricker SP, editor. Chapman and Hall; London: 1994. pp. 109–146. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Harding MM, Mokdsi G. Antitumour Metallocenes: Structure-Activity Studies and Interactions with Biomolecules. Current Medicinal Chemistry. 2000;7:1289–1303. doi: 10.2174/0929867003374066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Meléndez E. Titanium Complexes in Cancer Therapy. Critical Review in Oncology/Hematology. 2002;47:309–315. doi: 10.1016/s1040-8428(01)00224-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Berdel WE, Schmoll H-J, Scheulen ME, Korfel A, Knoche MF, Harstrick A, Bach F, Baumgart J, Sab G. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 1994;120(Supp):R172. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Korfel A, Scheulen ME, Schmoll H-J, Gründel O, Harstrick A, Knoche M, Fels LM, Skorzec M, Bach F, Baumgart J, Saß G, Seeber S, Thiel E, Berdel W. Phase I clinical and pharmacokinetic study of titanocene dichloride in adults with advanced solid tumors. Clin. Cancer Res. 1998;4:2701–2708. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Luemmen G, Sperling H, Luboldt H, Otto T, Ruebben H. Phase II trial of titanocene dichloride in advanced renal-cell carcinoma. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 1998;42:415–417. doi: 10.1007/s002800050838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Christodoulou CV, Ferry DR, Fyfe DW, Young A, Doran J, Sheehan TMT, Eliopoulos A, Hale K, Baumgart J, Sass G, Kerr DJ. Phase I trial of weekly scheduling and pharmacokinetics of titanocene dichloride in patients with advaced cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 1998;16:2761–2766. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1998.16.8.2761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.a Kröger N, Kleeberg UR, Mross K, Sass G, Hossfeld DK. Phase II clinical trial of titanocene dichloride in patients with metastatic breast cancer. Onkol. 2000;23:60–62. [Google Scholar]; b Baumgart J, Berdel WE, Fiebig H, Unger C. Phase I clinical trial of a day-1-3-5- every 3 weeks schedule with titanocene dichloride (MKT 5) in patients with advanced cancer – A study of the phase I study group of the Associantion of Medical Oncology (AIO) of the German Cancer Society. Onkol. 2000;23:576–579. doi: 10.1159/000055009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Toney JH, Marks TJ. Hydrolysis Chemistry of the Metallocene Dichlorides, M(Cp2)Cl2, M = Ti, V, Zr: Aqueous Kinetics, Equilibria and Mechanistic Implications for a New Class of Antitumor Agents. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1985;107:947–953. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Boyles JR, Baird MC, Campling BG, Jain N. Enhanced anti-cancer activities of some derivatives of titanocene dichloride. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2001;84:159–162. doi: 10.1016/s0162-0134(00)00203-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Valadares M,C, Klein SL, Guaraldo AMA, Queiroz MLS. Enhancement of natural killer cell function by titanocenes in mice bearing Ehrlich ascites tumour. Eur. J. Pharmac. 2003;473:191–196. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(03)01967-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Connor KO, Gill C, Tacke M, Rehmann F-JK, Strohfeldt K, Sweeney N, Fitzpatrick JM, Watson RWG. Novel titanocene anti-cancer drugs and their effect on apoptosis and the apoptotic pathway in prostate cancer cells. Apoptosis. 2006;11:1205–1214. doi: 10.1007/s10495-006-6796-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Allen OR, Croll L, Gott G, Knox RJ, McGowan PC. Functionalized Cyclopentadienyl Titanium Organometallic Compounds as New Antitumor Drugs. Organometallics. 2004;23:288–292. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Valadares MC, Ramos AL, Rehmann F-JK, Sweeney NJ, Strohfeldt K, Tacke M, Queiroz ML. Antitumor activity of [1,2-di-(cyclopentadienyl)1,2-di(p-N,N-dimethylaminophenyl)-ethanediyl] titanium dichloride in xenografted Ehrlich's ascites tumour. Eur. J. Pharm. 2006;534:264–270. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2006.01.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Potter GD, Baird M, Cole SP. A new series of titanocene dichloride derivatives bearing cyclic alkylammonium groups: Assessment of their cytotoxic properties. J. Organometal. Chem. 2007;692:3508–3518. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pampillón C, Sweeney NJ, Strohfeldt K, Tacke M. Synthesis and cytotoxic studies of new dimethylamino-functionalised and heteroaryl-substituted titanocene anti-cancer drugs. J. Organometal. Chem. 2007;692:2153–2159. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sweeney N, Gallagher WM, Müller-Bunz H, Pampillón C, Strohfeldt K, Tacke M. Heteroaryl substituted titanocenes as potential anti-cancer drugs. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2006;100:1479–1486. doi: 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2006.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sweeney NJ, Mendoza O, Müller-Bunz H, Pampillón C, Rehmann F-JK, Strohfeldt K, Tacke M. Novel benzyl substituted titanocene anti-cancer drugs. J. Organometal. Chem. 2005;690:4537–4544. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rehmann F-JK, Cuffe LP, Mendoza O, Rai DK, Sweeney N, Strohfeldt K, Gallagher WM, Tacke M. Heteroaryl substituted ansa-titanocene anti-cancer drugs derived from fulvenes and titanium dichloride. App. Organometal. Chem. 2005;19:293–300. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Boyles JR, Baird MC, Campling BG, Jain N. Enhanced anti-cancer activities of some derivatives of titanocene dichloride. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2001;84:159–162. doi: 10.1016/s0162-0134(00)00203-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gómez-Ruiz S, Kaluderovic GN, Polo-Cerón D, Prashar S, Fajardo M, Žižak Z, Juranić ZD, Sabo T. Study of the cytotoxic activity of alkenyl-substituted ansa-titanocene complexes. Inorg. Chem. Comm. 2007;10:748–752. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Top S, Kaloun EB, Vessières A, Laïos I, Leclercq G, Jaouen G. The first titanocenyl dichloride moiety vectorised by a selective estrogen receptor modulator (SERM). Synthesis and preliminary biochemical behaviour. J. Organometal. Chem. 643. 2002;644:350–356. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Meléndez E, Marrero M, Rivera C, Hernández E, Segal A. Spectroscopic Characterization of Titanocene Complexes with Thionucleobase. Inorg. Chim. Acta. 2000;298:176–186. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pérez Y, López V, Rivera-Rivera L, Cardona A, Meléndez E. Water soluble titanocene complexes with sulfur-containing aminoacids: synthesis, spectroscopic, electrochemical and Ti(IV)-transferrin interaction studies. J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 2005;10:94–104. doi: 10.1007/s00775-004-0614-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gao LM, Hernández R, Matta J, Meléndez E. Synthesis, Ti(IV) intake by apotransferrin and cytotoxic properties of functionalized titanocene dichlorides. J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 2007;12:959–967. doi: 10.1007/s00775-007-0268-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hernández R, Lamboy J, Gao LM, Matta J, Román FR, Meléndez E. Structure-Activity Studies of Ti(IV) Complexes: Aqueous Stability and Cytotoxic properties in colon cancer HT-29 cells. J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 2008;13:685–692. doi: 10.1007/s00775-008-0353-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gansäuer A, Franke D, Lauterbach T, Nieger M. A Modular and Efficient Synthesis of Functional Titanocenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:11622–16623. doi: 10.1021/ja054185r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gansäuer A, Winkler I, Worgull D, Franke D, Lauterbach T, Okkel A, Nieger M. A Modular Synthesis of Functional Titanocenes. Organometallics. 2008;27:5699–5707. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gansäuer A, Winkler I, Worgull D, Lauterbach T, FraWagner L, Prokop A. Carbonyl-Substituted Titanocenes: A Novel Class of Cytotoxic Compounds with High Antitumor and Antileukemic Activity. Chem. Eur. J. 2008;14:4160–4163. doi: 10.1002/chem.200800407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Weber H, Claffey J, Hogan M, Pampillón C, Tacke M. Analyses of Titanocenes in the spheroid-based cellular angiogenesis assay. Toxicology in Vitro. 2008;22:531–534. doi: 10.1016/j.tiv.2007.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Oberschmidt O, Hanauske AR, Pampillón C, Sweeney NJ, Strohfeldt K, Tacke M. Antiprolieferative activity of Titanocene Y against tumor colony-forming units. Anti-Cancer Drugs. 2007;18:317–321. doi: 10.1097/CAD.0b013e3280115f86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pampillón C, Sweeney NJ, Strohfeldt K, Tacke M. Synthesis and cytotoxic studies of new dimethylamino-functionalised and heteroaryl-substituted titanocene anti-cancer drugs. J. Organometal. Chem. 2007;692:2153–2159. [Google Scholar]

- 40.O'Connor, Gill C, Tacke M, Rehmann FJK, Strohfeldt K, Sweeney NJ, Fitzpartrick JM, Watson RWG. Novel titanocene anti-cancer drugs and their effect on apoptosis and the apoptotic pathway in prostate cancer cells. Apoptosis. 2006;11:1205–1214. doi: 10.1007/s10495-006-6796-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lamboy J, Pasquale A, Rheingold AL, Meléndez E. Synthesis, Solution and Solid State Structure of Titanium-Maltol Complex. Inorg. Chim. Acta. 2007;360:215–2120. doi: 10.1016/j.ica.2006.10.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Arturson P, Borchardt RT. Intestinal Drug Absorption and Metabolism in Cell Cultures: Caco-2 and beyond. Pharm. Res. 1997;14:1655–1658. doi: 10.1023/a:1012155124489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yeung CK, Glahn PR, Miller DD. Inhibition of Iron Uptake from Iron Salts and Chelates by Divalent Metal Cations in Intestinal Epithelial Cells. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2005;53:132–136. doi: 10.1021/jf049255c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Waern JB, Dillon CT, Harding MM. Organometallic Anticancer Agents: Cellular Uptake and Cytotoxicity Studies on Thiol Derivatives of the Antitumor Agent Molybdocene Dichloride. J. Med. Chem. 2005;48:2093–2099. doi: 10.1021/jm049585o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.