Abstract

This case report presents data regarding endogenous opioid analgesia in a healthy female subject prior to developing chronic pain, and again 4 and 13 months following onset of chronic daily back pain. At each assessment period, the subject underwent identical protocols involving two sessions one week apart with randomized double-blind crossover administration of saline placebo and naloxone, an opioid antagonist. Each session included a 5-minute anger recall interview, followed by finger pressure and ischemic acute pain tasks. Increases in acute pain ratings induced by opioid blockade were interpreted as reflecting endogenous opioid analgesia. When the subject was healthy and pain-free, naloxone produced a mean overall 16% decrease in pain ratings relative to placebo. However, 4 months after onset of chronic pain, a mean naloxone-induced increase of 22% in pain ratings over placebo was observed, consistent with presence of endogenous opioid analgesia. The mean magnitude of this opioid blockade effect for the finger pressure task exceeded the 99% confidence interval for the healthy control population based on a previous study using a similar opioid blockade protocol (Bruehl et al., 2008). At 13-month follow-up, naloxone produced a mean 45% decrease in acute pain ratings compared to placebo, arguing against presence of endogenous opioid analgesia. Although results must be interpreted cautiously, findings are consistent with the hypothesis that chronic pain may initially be associated with upregulation of endogenous opioid analgesic systems which then may become dysfunctional over time.

Keywords: chronic pain, acute pain, endogenous opioids, opioid blockade, prospective, blood pressure

Introduction

Activity within the endogenous antinociceptive system is believed to be dependent on duration of pain stimuli [18]. It has been proposed that if pain persists beyond the initial healing period following injury, descending inhibitory pathways display progressively increased activity to facilitate resumption of normal activities required for survival [18]. It has further been suggested that long-term chronic pain may develop when persistent demands to modulate ongoing nociceptive activity result in failure of descending pain inhibitory mechanisms [6,15,18]. An association between long-term chronic pain and endogenous opioid antinociceptive dysfunction is supported by cross-sectional studies indicating lower endogenous opioid levels and diminished endogenous opioid analgesic activity in chronic pain patients compared to healthy individuals [e.g., 1,5,11,12,19,24].

The idea that persistent pain is associated initially with upregulation of antinociceptive systems followed by progressive exhaustion of these systems is consistent with known mechanisms. Yet, beyond the cross-sectional data in long-term chronic pain noted above, there is little human research that has specifically examined this issue. Two cross-sectional studies suggest that endogenous opioid levels in cerebrospinal fluid are inversely correlated with constancy and duration of chronic pain, both of which would support progressive opioid system dysfunction [1,12]. To our knowledge, however, no studies have quantitatively evaluated within-subject changes in endogenous opioid analgesic system function from the pain-free state through the development of relatively long duration chronic pain.

Data being collected as part of a larger study focused on anger regulation and endogenous opioids presented an opportunity to conduct controlled evaluation of endogenous opioid analgesic function, as reflected in responses to opioid blockade, in an individual when in a healthy pain-free state, and then again 4 months and 13 months after onset of chronic daily low back pain. We hypothesized that in accord with suggestions by Millan [18], endogenous opioid analgesic activity would be greater after relatively brief chronic pain than when in the pain-free state due to pain-related upregulation of these systems, with a subsequent decrease in opioid analgesic activity after more prolonged chronic pain.

Method

Subject

The subject was a 54 year old white non-Hispanic female. She initially participated in the study described below as a healthy pain-free control. Six months after initial study participation, the subject responded to an e-mail advertisement seeking individuals with chronic low back pain (e.g., daily low back pain of at least 3 months duration), stating that approximately 2 months after her initial participation, she developed persistent daily low back pain (following an exercise-related injury) which had become increasingly severe in intensity over several months. This provided a unique opportunity to examine chronic pain-related changes in endogenous opioid analgesic system function over time within an individual.

The subject was asked to participate again in laboratory sessions to evaluate her endogenous opioid analgesic function after experiencing daily low back pain for 4.2 months (to examine initial chronic pain-related changes) and again at 12.8 months post-onset (to examine longer-term effects). Electronic pain diary ratings obtained during the week between her two sessions at each follow-up period after chronic pain onset indicated a mean weekly chronic pain intensity of 29/100 (range = 2 – 73) at 4.2 months, and 28/100 (range = 10-51) at 12.8 months. Comparable pain diary ratings obtained when the subject participated as a healthy control indicated a mean weekly pain intensity of 4/100 (range = 0 – 32), with only four diary assessment periods showing non-zero values due to presence of mild-moderate headache. During brief medical evaluation, the subject described stiffness and pain (“burning,” “aching”) localized in the right lower back (sacroiliac area) extending down the right posterior thigh to the knee. Diagnostic studies were not available. A detailed neurological examination was not conducted. The subject was post-menopausal, and not using oral contraceptives or hormone replacement therapy. She was not taking antidepressant medications, neuroleptics, or opioid analgesics at any time before or after onset of her back pain. After developing chronic pain, she stated that she often used acetaminophen (1000mg) at night for pain control, but refrained from this medication for 3 days prior to each laboratory session. Her responses on the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI; [2]) indicated she was in the non-depressed range during all three study periods (total BDI scores of 7, 8, and 5, respectively).

Procedure

All procedures were performed at the Vanderbilt University General Clinical Research Center and were approved by the university Institutional Review Board (IRB). The subject provided informed consent prior to all three laboratory studies (once as healthy control, twice as a chronic pain subject). During each of these assessment periods (hereafter referred to as No LBP, Early LBP, and Late LBP), the subject participated in two laboratory sessions one week apart (identical procedures except for different study drug), with all sessions beginning at 1:00 pm to control for circadian rhythms. The subject was seated upright in a comfortable chair throughout all laboratory procedures, which were identical to those for all other subjects in the larger study (data as yet unpublished).

During each laboratory session, the subject initially completed a 10-minute seated rest period, followed by a series of five pre-drug resting blood pressure (BP) determinations using an oscillometric blood pressure cuff (Vital-Guard 450C, Ivy Biomedical Systems). Mean resting BP over the course of the study was: No LBP = 109.5/55.5, Early LBP = 113.6/63.4, and Late LBP = 121.0/65.9. Over the nearly 13 month study period, resting systolic and diastolic BP increased 10.5% and 18.7%, respectively.

Upon termination of BP assessment in the Early and Late LBP conditions, the subject also provided 100mm visual analog scale (VAS) ratings of her current chronic back pain intensity and unpleasantness at that moment (as a baseline). An indwelling venous cannula was then placed in the subject's nondominant arm, followed by a 30-minute resting adaptation period. Next, a 20ml dose of normal saline (placebo) or an 8mg dose of the opioid receptor antagonist naloxone hydrochloride (in 20ml saline vehicle) was infused over a 10-minute period using an automated infusion pump. Drug administration was double-blinded, with drug order randomized and counterbalanced.

After a 10-minute rest following drug infusion to allow peak opioid blockade activity to be achieved, the subject participated in a five-minute anger recall interview during which a recent anger provoking memory was discussed with a trained interviewer (as in [7]). Identical interview procedures (with different but comparable angry memories) were conducted at each laboratory session. A 60-second finger pressure pain task (FP) was then conducted using a Forgione-Barber finger pressure pain stimulator that applied 2000 grams of pressure to the dorsal surface of the second phalanx of the index finger of the dominant hand [10]. At 15-second intervals during this task, the subject was asked to provide verbal numeric pain intensity ratings (NRS) on a 0 – 100 scale (anchored with “no pain” and “worst possible pain”). Immediately upon cessation of this task, acute pain ratings were also obtained including a 100mm visual analog pain intensity scale (VAS Intensity; anchored with “No Pain” and “Worst Possible Pain”) and a 100mm VAS Unpleasantness scale (anchored with “Not Unpleasant at All” and “The Most Unpleasant Possible”).

The subject then participated in a forearm ischemic pain task (ISC; [16]) using procedures detailed in our prior work [4]. As for the FP task, intra-task verbal NRS pain intensity ratings and post-task VAS intensity and VAS Unpleasantness scales were completed to describe the ischemic task pain. Immediately after completing these acute pain ratings, the subject was again asked to provide VAS ratings of her back pain intensity and unpleasantness at that moment.

Data Reduction

Opioid blockade effects were derived for all acute pain measures, reflecting naloxone condition pain ratings minus placebo condition values. Positive blockade effects indicated that naloxone produced increased acute pain ratings. In studies with larger samples, positive blockade effects are interpreted as suggesting presence of endogenous opioid analgesia in the placebo condition. However, interpretation of blockade effects in a single subject case study such as this may be ambiguous due to the possibility of random fluctuations. With this caveat noted, blockade effect data from the three assessment periods in this case study were cautiously interpreted as a possible index of changes in endogenous opioid function over time.

Results

Effects of Opioid Blockade on Acute Pain Responses

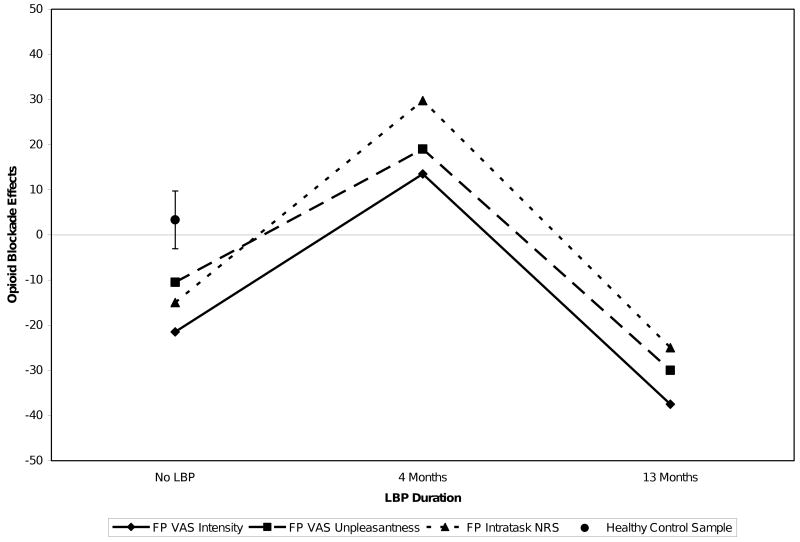

Table 1 summarizes the subject's raw placebo and naloxone condition pain ratings for the two acute pain tasks in the No LBP, Early LBP, and Late LBP assessment periods. To facilitate interpretation of changes in opioid blockade responses over time, Figure 1 presents opioid blockade effects for the FP task as a function of presence and duration of chronic pain. Table 1 and Figure 1 indicate that for the FP task, opioid blockade did not increase pain ratings in the No LBP phase or in the Late LBP phase, but did produce substantial increases in pain ratings (positive blockade effects) on all three measures in the Early LBP phase. Increased pain ratings with opioid blockade may indicate endogenous opioid analgesia. For comparison, Figure 1 also presents the 95% confidence intervals for mean naloxone blockade effects on the same FP task pain rating measures obtained in 52 healthy normal controls in a prior study [4]. These data permit comparison of the case study subject's blockade effect values to the best estimate of the true population mean for blockade effects in healthy pain-free individuals on this task. Values exceeding the 95% confidence interval can be viewed as being significantly different from the population mean at the p<.05 significance level [23]. Values for all three FP blockade effect measures for the study subject exceed the 95% confidence interval for the healthy normal population in the Early LBP phase, but not the No LBP or Late LBP phases. In fact, the mean FP opioid blockade effect in the Early LBP phase of the current study was 20.75, which exceeds the 99% confidence interval for the healthy control population. These findings may indicate that the study subject's degree of opioid analgesia in the Early LBP phase, but not in the No LBP or Late LBP phases, significantly exceeded the values expected based on random variations in the healthy control population.

Table 1.

Placebo and naloxone condition acute pain ratings as a function of presence and duration of chronic low back pain (LBP).

| Placebo Condition | Naloxone Condition | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acute Pain Measure (0-100) | No LBP | Early LBP | Late LBP | No LBP | Early LBP | Late LBP |

| FP VAS Intensity | 79.0 | 81.5 | 82.5 | 57.5 | 95.0 | 45.0 |

| FP VAS Unpleasantness | 58.0 | 67.0 | 61.0 | 47.5 | 86.0 | 31.0 |

| FP Intra-Task NRS | 72.5 | 51.3 | 80.0 | 57.5 | 81.0 | 55.0 |

| ISC VAS Intensity | 78.0 | 90.5 | 91.5 | 71.0 | 88.0 | 40.5 |

| ISC VAS Unpleasantness | 61.0 | 81.0 | 83.5 | 56.0 | 87.0 | 28.0 |

| ISC Intra-Task NRS | 60.7 | 63.8 | 59.4 | 53.0 | 80.9 | 46.5 |

Note: Post-LBP testing was performed 4.2 months (Early) and 12.8 months (Late) following pain onset. FP = Finger Pressure Task, ISC = Ischemic Pain Task, VAS = Visual Analog Scale, NRS = Verbal Numeric Pain Intensity Rating Scale.

Figure 1.

Opioid blockade effects on finger pressure (FP) task pain ratings as a function of presence and duration of LBP. Error bars for healthy normal FP blockade effect data reflect the 95% confidence interval.

For the ISC task, a similar pattern was observed for both the intra-task NRS and VAS Unpleasantness ratings (Table 1). That is, increased pain ratings under opioid blockade relative to placebo were observed only in the Early LBP period. Comparison of the study subject's ISC blockade effects to the best estimate of the population mean for these measures in healthy controls indicates that the intra-task NRS ratings exceeded the 95% confidence interval for healthy controls in the Early LBP phase, but not the No LBP and Late LBP phases. Values at all three phases for the remaining two ISC blockade effect measures were all within the 95% confidence intervals for healthy controls.

To provide an alternative index of effect size, percentage change in pain resulting from opioid blockade [(Naloxone Pain − Placebo Pain / Placebo Pain) × 100] was calculated and averaged across all pain measures and both pain tasks. Results indicated that at the No LBP and Late LBP assessment periods, opioid blockade produced mean decreases in pain ratings of 16.0% and 45.0%, consistent with absence of endogenous opioid analgesia. In contrast, during the Early LBP period, opioid blockade produced a mean increase in pain ratings of 22.4%, consistent with endogenous opioid analgesia.

Chronic Pain Opioid Blockade Effects

Within-session changes in intensity and unpleasantness of the subject's chronic back pain from baseline to post-pain induction were examined by drug condition. It was hypothesized that the acute pain tasks would elicit endogenous opioid analgesia to the extent that these systems were functional, and that the degree of reduction in chronic pain following acute pain stimulation (if it were influenced by endogenous opioids) might provide a secondary index of how opioid analgesic function changed over the course of chronic pain. It was assumed that greater acute pain-induced reductions in chronic pain under placebo compared to naloxone would be consistent with presence of greater opioid analgesia at a given assessment period.

The most notable opioid-related effects were observed on ratings of chronic back pain unpleasantness. In the Early LBP assessment period, ratings of back pain unpleasantness following the pain tasks were reduced by 75.0% from baseline in the placebo condition, whereas these ratings were only reduced 21.2% under opioid blockade. This pattern would be consistent with the pain tasks triggering opioid analgesia that reduced the intensity of the subject's low back pain under placebo, with opioid blockade reducing the magnitude of this analgesia by 71.7% (i.e., from a 75% to a 21.2% analgesic effect). Similar data obtained at the Late LBP assessment period (nearly 13 months after back pain onset) also suggested opioid-mediated reductions in back pain unpleasantness, but somewhat smaller in magnitude than at the Early LBP period. Ratings of back pain unpleasantness following the pain tasks were reduced by 97.9% from baseline in the placebo condition, whereas these ratings were reduced 55.3% under opioid blockade. Thus, opioid blockade reduced the magnitude of pain task-induced analgesia on chronic pain unpleasantness by 43.5% at the Late LBP assessment period, compared to nearly 72% at the Early LBP period. The pattern of findings above would be at least partially consistent with the pattern of blockade effects observed on acute pain measures, suggesting that endogenous opioid analgesia was more prominent in the Early LBP phase.

Comparable data for the back pain intensity measure at each assessment period revealed smaller effects of opioid blockade, and a pattern inconsistent with the hypotheses above. Opioid blockade in the Early LBP period had no effect on acute pain-induced changes in chronic pain intensity (58.5% reduction in LBP intensity under placebo compared to 60.9% reduction under opioid blockade). However, results during the Late LBP assessment period indicated a 78.1% reduction in LBP intensity under placebo compared to a 49.0% reduction under opioid blockade. This 37.2% reduction in acute pain-induced analgesia in the Late LBP period suggests that some degree of pain-induced opioid analgesia on chronic pain intensity was present only during the Late LBP period, in contrast to expectations based on the pattern of acute pain blockade effects.

Discussion

This case study reflected a serendipitous opportunity to examine how chronic low back pain affects functioning in endogenous opioid analgesic systems within an individual. Acute pain opioid blockade effects revealed no endogenous opioid analgesia prior to back pain onset. However, as might be expected given the homeostatic functions of the opioid system [9,22], chronic pain of four month's duration appeared to be associated with significant endogenous opioid analgesia. At this Early LBP phase, all three acute FP pain measures and ISC intra-task pain intensity ratings exceeded the 95% confidence intervals for the healthy control population [4]. These findings suggest the subject's endogenous opioid analgesic systems may have upregulated to modulate ongoing nociceptive input in the context of relatively short-term chronic pain.

In contrast to the findings above, results 13 months following onset of back pain indicated an absence of opioid analgesia to acute pain. This would be consistent with results from previous cross-sectional studies in patients with chronic pain of extended duration that suggested levels of endogenous opioids are reduced relative to pain-free individuals [e.g., 1,5,11,12,19,24; see 6 for a review]. Consistent with these findings, previous work examining opioid blockade effects on acute pain responses in patients with long-duration chronic back pain also suggest impaired endogenous opioid analgesic function [5]. Overall, the current results are consistent with proposals that persistent clinical pain initially results in upregulation of endogenous opioid analgesic function as a homeostatic response to facilitate adaptation to pain [18]. If nociceptive input continues unabated for sufficient time, endogenous opioid systems may become overtaxed, through exceeding biosynthetic capacity, upregulation of enzymes, or downregulation of opioid receptors in response to persistently elevated endogenous opioid levels, eventually producing the opioid dysfunction often reported in cross-sectional studies. This progressive dysfunction hypothesis remains to be proven in larger scale prospective studies, although is consistent with findings that endogenous opioid levels are inversely correlated with constancy and duration of chronic pain [1,12].

Prior work suggest that chronic pain may have a relatively larger affective component compared to acute pain [17,21]. Reductions in chronic pain following acute pain stimulation in this study suggested a pattern similar to the acute pain blockade effects but only for the affective component of pain. That is, in the Early LBP phase but not the Late LBP phase, reductions in chronic pain unpleasantness (affective component) following acute pain stimulation were substantially larger when opioid systems were intact than when opioid systems were pharmacologically blocked. This pattern is consistent with results for the acute pain blockade effects, suggesting the greatest opioid analgesia occurred in the Early LBP phase. In contrast, findings for chronic pain intensity suggested that opioid analgesia did not impact on chronic pain intensity in the Early LBP phase, but did exert some influence in the Late LBP phase. Reasons for this discrepancy between sensory and affective blockade effect findings are unknown, although past work indicates these two components of pain are separable and regulated by different brain pathways [13,20]. Given the ubiquity of opioids in both of these separable pathways [3], it is not inconceivable that opioid activity might be altered by presence of chronic pain differentially across these pathways. Although findings for opioid analgesia on acute pain responsiveness and chronic pain unpleasantness are consistent in suggesting greater opioid analgesia in the Early LBP phase, inconsistent findings for chronic pain intensity highlight the possibility that these effects could be due to random variations. Additional work is required to replicate these findings.

Some comment regarding the potential role of placebo analgesia in the present findings should be made. Prior work indicates that placebo analgesia to acute pain stimuli can be mediated by endogenous opioids [14]. In the current case study, the subject displayed apparent opioid analgesia only in the Early LBP period, which could indicate that an opioid-mediated placebo response occurred selectively at this assessment period. Given the double-blind, placebo-controlled crossover nature of the study design at all three assessment periods, and that statements to the subject about naloxone's pain-related effects were consistent throughout all study sessions (i.e., naloxone might increase, decrease, or not alter pain responses), degree of opioid-mediated placebo response to drug administration might have been expected to be consistent across assessment periods. Although it cannot be conclusively proven that the apparent opioid analgesia observed in the Early LBP period was due to recent onset of clinical pain per se, the subject did not take opioid analgesics at any point during the study and no other factors are known which might have exaggerated an opioid-mediated placebo response selectively at this one time point.

It is important to note that results from a single case, even using careful experimental controls, cannot address all threats to internal validity such as history effects [8] and cannot be generalized to the chronic pain population as a whole. Findings of this study are best considered as a tool for hypothesis generation, and replication in larger controlled studies is required. To our knowledge, this is the first quantitative within-subject evaluation of changes in endogenous opioid function related to chronic pain of any duration. While the current findings are consistent with theoretical predictions [39], the possibility must be considered that a pattern reflecting initial opioid upregulation followed by progressive opioid dysfunction may only occur in a subset of patients (as suggested by [5]). This possibility must be evaluated in future studies, with results potentially having implications both for treatment selection and for understanding processes contributing to chronic pain-related dysfunction.

In summary, results of this case study suggested that chronic pain of relatively brief duration may be associated with upregulation of endogenous opioid analgesia, presumably to facilitate adaptation to ongoing nociceptive input. Findings further suggest that after longer duration low back pain, the initial upregulation in endogenous opioid analgesia disappeared, possibly reflecting development of opioid dysfunction as a result of excessive demands on the opioid system. Replication of these findings in larger prospective studies would be valuable.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by NIH Grants NS050578 and NS046694, and Vanderbilt CTSA grant 1 UL1 RR024975 from the National Center for Research Resources, NIH. The authors have no conflicts of interest. The authors gratefully acknowledge the assistance of Dr. Robert Jamison, Brian Schuth, Dr. Lisa Marceau and New England Research Institute in developing the electronic pain diary software, as well as the assistance of the research nurses of the Vanderbilt General Clinical Research Center.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Almay B, Johansson F, Von Knorring L, Terenius L, Wahlstrom A. Endorphins in chronic pain I: Differences in CSF endorphin levels between organic and psychogenic pain syndromes. Pain. 1978;5:153–162. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(78)90037-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beck AT, Ward CH, Mendelson M, Mock JE, Erbough JK. An inventory for measuring depression. Arch Gen Psychiat. 1961;4:561–571. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1961.01710120031004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bruehl S, Burns JW, Chung OY, Chont M. Pain-related effects of trait anger expression: Neural substrates and the role of endogenous opioid mechanisms. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2009;33:475–491. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2008.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bruehl S, Burns JW, Chung OY, Quartana P. Anger management style and emotional reactivity to noxious stimuli among chronic pain patients and healthy controls: the role of endogenous opioids. Health Psychol. 2008;27:204–214. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.27.2.204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bruehl S, Chung OY. Parental history of chronic pain may be associated with impairments in endogenous opioid analgesic systems. Pain. 2006;124:287–294. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2006.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bruehl S, McCubbin JA, Harden RN. Theoretical review: Altered pain regulatory systems in chronic pain. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 1999;23:877–890. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(99)00039-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Burns JW, Kubilus A, Bruehl S. Emotion-induction moderates effects of anger management style on acute pain sensitivity. Pain. 2003;106:109–118. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(03)00298-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Campbell DT, Stanley JC. Experimental and quasi-experimental designs for research. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin Company; 1963. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Drolet G, Dumont EC, Gosselin I, Kinkead R, Laforest S, Trotter JF. Role of endogenous opioid system in the regulation of the stress response. Prog Neuro-pyschopharmacol Biol Psychiat. 2001;25:729–741. doi: 10.1016/s0278-5846(01)00161-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Forgione AG, Barber TX. A strain gauge pain stimulator. Psychophys. 1971;8:102–106. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.1971.tb00441.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fukui T, Hameroff SR, Gandolfi AJ. Alpha-1-acid glycoprotein and beta-endorphin alterations in chronic pain patients. Anesthes. 1984;60:494–496. doi: 10.1097/00000542-198405000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Genazzani AR, Nappi G, Facchinetti F, Micieli G, Petraglia F, Bono G, Monittola C, Savoldi F. Progressive impairment of CSF B-EP levels in migraine sufferers. Pain. 1984;18:127–133. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(84)90880-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hofbauer RK, Rainville P, Duncan GH, Bushnell MC. Cortical representation of the sensory dimension of pain. J Neurophysiol. 2001;86:402–411. doi: 10.1152/jn.2001.86.1.402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Levine JD, Gordon NC, Fields HL. The mechanism of placebo analgesia. Lancet. 1978;2(8091):654–657. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(78)92762-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Maixner W, Sigurdsson A, Fillingim RB, Lundeen T, Booker DK. Regulation of acute and chronic orofacial pain. In: Fricton JR, Dubner R, editors. Orofacial Pain and Temporomandibular Disorders. New York: Raven Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Maurset A, Skoglung LA, Hustveit O, Klepstad P, Oye I. A new version of the ischemic tourniquet pain test. Meth Find Exp Clin Pharmacol. 1992;13:643–647. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Melzack RM, Wall PD, Ty TC. Acute pain in an emergency clinic: latency of onset and description patterns related to different injuries. Pain. 1982;14:33–43. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(82)90078-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Millan MJ. Descending control of pain. Prog Neurobiol. 2002;66:355–474. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(02)00009-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Puig MM, Laorden ML, Miralles FS, Olaso MJ. Endorphin levels in cerebrospinal fluid of patients with postoperative and chronic pain. J Anesthes. 1982;57:1–4. doi: 10.1097/00000542-198207000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rainville P, Carrier B, Hofbauer RK, Bushnell MC, Duncan GH. Dissociation of sensory and affective dimensions of pain using hypnotic modulation. Pain. 1999;82:159–171. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(99)00048-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Reading AE. An analysis of the language of pain in chronic and acute patient groups. Pain. 1982;13:185–192. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(82)90028-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ribeiro SC, Kennedy SC, Smith YR, Stohler CS, Zubieta JK. Interface of physical and emotional stress regulation through the endogenous opioid system and mu-opioid receptors. Prog Neuro-Psychopharm Bio Psychiatr. 2005;29:1264–1280. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2005.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sim J, Reid N. Statistical inference by confidence intervals: issues of interpretation and utilization. Phys Ther. 1999;79:186–195. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Simonnet G, Taquet H, Floras P, Caille JM, Legrand JC, Vincent JD. Simultaneous determination of radio-immunoassayable methionine-enkephalin and radioreceptor-active opiate peptides in CSF of chronic pain suffering and non-suffering patients. Neuropeptides. 1986;7:229–240. doi: 10.1016/0143-4179(86)90016-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]