Abstract

In astrocytes, the Ca2+-dependent protein phosphatase calcineurin (CN) strongly regulates neuro-immune/inflammatory cascades through activation of the transcription factor, nuclear factor of activated T cells (NFAT). While primary cell cultures provide a useful model system for investigating astrocytic CN/NFAT signaling, variable results may arise both within and across labs because of differences in culture conditions. Here, we determined the extent to which serum and cell confluency affect basal and evoked astrocytic NFAT activity in primary cortical astrocyte cultures. Cells were grown to either ~50% or >90% confluency, pre-loaded with an NFAT-luciferase reporter construct, and maintained for 16 h in medium with or without 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS). NFAT-dependent luciferase expression was then measured 5 h after treatment with vehicle alone to assess basal NFAT activity, or with Ca2+ mobilizers and IL-1β to assess evoked activity. The results revealed significantly higher levels of basal NFAT activity in FBS-containing medium, regardless of cell confluency. Conversely, evoked NFAT activation was significantly lower in serum-containing medium, with an even greater inhibition observed in confluent cultures. Application of 10% FBS to serum-free astrocyte cultures quickly evoked a roughly seven-fold increase in NFAT activity that was significantly reduced by co-delivery of neutralizing agents for IL-1β, TNFα, and/or IFNγ, suggesting that serum occludes evoked NFAT activation through a cytokine-based mechanism. Together, the results demonstrate that the presence of serum and cell confluency have a major impact on CN/NFAT signaling in primary astrocyte cultures and therefore must be taken into consideration when using this model system.

Keywords: calcineurin, NFAT, astrocyte, serum, confluency, primary culture

Introduction

The protein phosphatase calcineurin (CN) and the transcription factor NFAT are well-known to extensively and efficiently regulate immune/inflammatory responses in peripheral cell types, such as T and B lymphocytes [13]. More recent work has shown that the CN/NFAT pathway also plays a critical role in neuroinflammatory signaling through its actions in astrocytes [5, 8, 23, 28]. Work by our group and others reveals substantial CN and NFAT expression in “activated” astrocytes during injury, aging, and/or amyloid pathology [1, 12, 22, 23]. Relative to “resting” astrocytes, activated astrocytes undergo morphological changes and release a vast array of cytokines and inflammatory mediators implicated in neuronal dysfunction and neurodegenerative diseases [7, 21, 26]. In addition to promoting neuroinflammation, activated astrocytes also appear to lose their capacity to buffer extracellular glutamate, which may increase neuronal vulnerability to excitotoxicity [1, 28]. Many of these changes are recapitulated when an activated form of CN is overexpressed in astrocytes [22], suggesting a critical role for CN/NFAT in both the activated astrocyte phenotype and neuroinflammation.

In recent years, primary astrocyte cultures have provided an excellent model system for studying the association between astrocytic CN/NFAT signaling and neuroinflammation. Similar to in vivo observations, a number of inflammatory mediators (e.g. IL-1β, TNFα, amyloid beta, glutamate, thrombin) activate astrocytes in culture, increase CN/NFAT activity [1, 5, 8, 23, 28], and/or cause further release of inflammatory mediators to stimulate a positive feedback cycle [28]. Although primary astrocyte cultures are commonly used and widely accepted, they are also highly vulnerable to a number of variables that could dramatically change the results and/or interpretations of any given study [2, 17]. For example, serum concentration in culture media has been shown to affect the abundance and activation of MAPK, PKC, and CDKs, among others, in a variety of cell lines, ultimately leading to differential gene expression and/or changes in cell health [10, 11, 20, 27].

The aim of our study was to determine how different cell culture conditions affect cell properties specifically associated with the astrocytic CN/NFAT signaling cascade. The results showed that 10% fetal bovine serum stimulates basal NFAT activity, but suppresses evoked activity. Moreover, serum effects depended on the confluency of cells, and were likely mediated by cytokine receptor activation. These observations demonstrate that careful attention must be given to the cell culture environment when investigating CN/NFAT signaling in primary astrocytes.

Materials and Methods

Primary cell culture

Primary astrocyte cultures were prepared from E18 Sprague Dawley rat pups similar to that described previously [28]. Animals were treated in accordance with the National Institute of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. In brief, tissue was harvested and washed in Hanks Balanced Salt Solution before trypsinization and mechanical dissociation by trituration. Cells were plated in culture flasks in Minimal Essential Medium (MEM), buffered by NaHCO3, and supplemented with L-glutamine, 1% antibiotics/antimitotics, and 10% fetal bovine serum. Astrocyte cultures were grown to 80–90% confluency (typically 10–12 days), and microglia were removed by vigorously shaking the flasks at room temperature for 30 min on an orbital shaker [14]. Cells were trypsinized and replated with fresh medium in 35-mm culture dishes and grown to either ~50% or > 90% confluency. Previous immunocytochemical analyses of our cultures have indicated that fewer than 5% of plated cells label positively for the microglial marker Iba-1 (data not shown). For serum-free studies, regular medium was replaced with serum-free medium (MEM, N2, and gentamicin) immediately prior to the start of experiments.

Replication-deficient Adenovirus

Adenovirus encoding an NFAT-dependent luciferase reporter construct (Ad-NFAT-Luc), was kindly provided by Dr. Jeff Molkentin (University of Cincinnati) and has been described elsewhere [30]. Virus was added to cultures at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 50. At this titre, we have estimated that most (~90%) astrocytes per dish/well are infected (as demonstrated by GFP expression or β-galactosidase staining), regardless of the presence of serum, cell confluency, age-in-vitro, or presence/absence of microglia (unpublished observations).

Drug Delivery

Phorbol ester and ionomycin (Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) were added simultaneously to cultures at final concentrations of 1 μM each. IL-1β (Pierce Biotechnologies, Rockford, IL) was delivered at a final concentration of 10 ng/mL. Astrocytes were treated with Ca2+ mobilizers and/or IL-1β for ~5 h before harvest. For serum-shock experiments, the IL-1β receptor antagonist (IL-RA), anti-IFNγ (both from R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN), and etanercept (gift from Dr. David Szymkowski, Xencor, Inc.) were delivered two hours prior to the addition of serum at final concentrations of 40 nM, 2 μM, and 250 μM, respectively. All concentrations were consistent with those used in similar studies or those recommended by manufacturers.

NFAT-luciferase Reporter Assays

NFAT-luciferase reporter assays were performed as described previously [28]. At approximately 16 h before treatment with inflammatory mediators, astrocyte cultures were infected with Ad-NFAT-Luc at 50 MOI in either serum-containing or serum-free media. After 5 h treatment with NFAT activators and/or antagonists, cultures were washed in PBS, scraped free, and pelleted at 13000 rpm. Pellets were resuspended in CAT buffer (250 mM Tris pH 8.0, 1mM EDTA) and stored at −20° C until use. As a control for between-group variability, all sample volumes were normalized to the same protein concentration using the Lowry method. Luciferase expression was quantified using a Tropix luciferase detection kit (Applied Biosystems, Bedford, MA) and plate reader. For each experiment, 6–8 dishes were analyzed per treatment condition.

Statistics

In each experiment, luciferase values were averaged across treatment conditions and compared with either repeated measures or factorial analysis of variance (ANOVA). Where necessary, Scheffe’s F-test was used for post hoc comparisons. Significance was set at p < 0.05. All experiments were repeated at least once in an independent set of astrocyte cultures with highly similar outcomes. Figures illustrate representative experiments.

Results

Effects of serum and cell confluency on basal and evoked NFAT activation in primary astrocytes

Cell culture conditions can have a profound impact on intracellular signaling cascades and may be a fundamental source of variability leading to conflicting results in the literature. Recently, several studies have used primary astrocytes to investigate CN/NFAT signaling [5, 8, 23, 28], yet little is known about the sensitivity of this pathway to specific factors of the cell culture environment. Here, we determined the extent to which serum and cell confluency modulate basal and evoked NFAT activity in primary astrocyte cultures. Primary cortical astrocyte cultures were prepared from embryonic (E18) rat pups and grown to approximately 50% confluency (sub-confluent) or greater than 90% confluency (confluent), then loaded with an NFAT-luciferase reporter construct using adenovirus, as described previously [28]. Cultures were maintained for 16 h in serum-free medium or medium containing 10% FBS. To evoke NFAT activity, cells were treated with the Ca2+ mobilizing agents, ionomycin and phorbol ester (1 μM each), or with the endogenous inflammatory mediator, IL-1β (10 ng/mL) and harvested 5 h later for measurement of luciferase expression. Vehicle-treated cultures were used to assess basal NFAT activity and also served as controls for evoked activity.

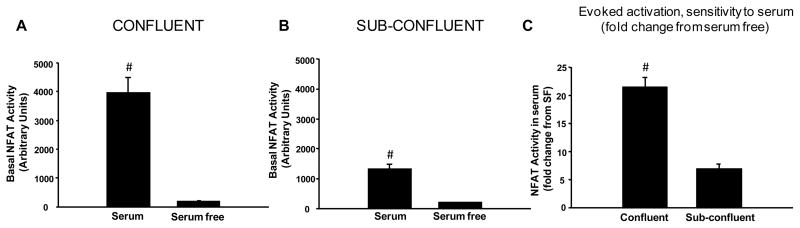

As shown in Figure 1, serum and cell confluency had interdependent effects on basal NFAT activity in primary astrocytes. Basal activity (Figure 1A, 1B) was potentiated in serum-containing medium (p < 0.001 for both confluent and sub-confluent cultures). Although both stages of confluency allowed for significantly higher basal levels of NFAT activity, it is clear that confluent cultures showed greater sensitivity to serum (Figure 1C, p < 0.001 confluent v. sub-confluent).

Figure 1. Effects of serum and confluency on basal NFAT activity in primary astrocytes.

Mean ± SEM basal NFAT-luc activity (arbitrary units) shown as a function of serum content in confluent (A) and sub-confluent (B) astrocyte cultures. Panel C shows the fold change increase in NFAT-luc activity in serum-containing relative to serum-free cultures (mean ± SEM). While confluent and sub-confluent cultures each exhibited elevated basal NFAT activity in the presence of serum, confluent cells were clearly more responsive (C). #p < 0.001

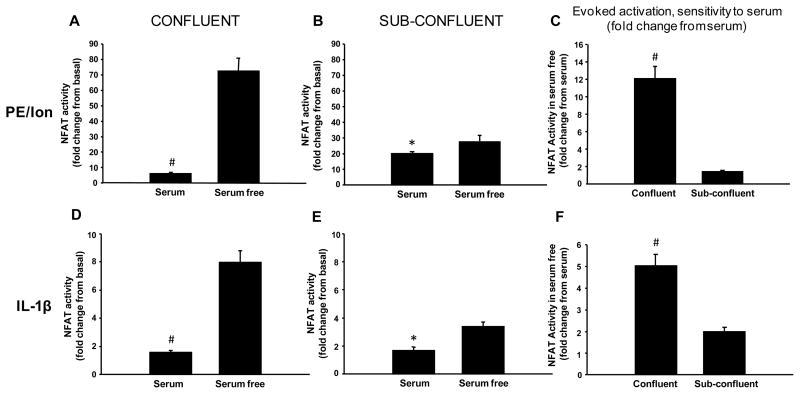

In contrast to basal activity, NFAT activity evoked by either PE/Ion or IL-1β (shown as fold change from basal activity) was significantly reduced (p < 0.05) in the presence of serum (Figure 2A, 2B, 2D, 2E). Despite these differences, evoked activity, like basal activity, showed far greater sensitivity to serum when cells were confluent (Figure 2C, 2F, p < 0.001). The results demonstrate that serum has disparate effects on basal and evoked NFAT activity that become more conspicuous when confluent cultures are used.

Figure 2. Effects of serum and cell confluency on evoked NFAT activity in primary astrocytes.

Mean ± SEM evoked NFAT-luc activity (fold change from basal levels) in confluent (A,D) and sub-confluent (B,E) cultures treated for ~5 h with either PE/Ion (A,B) or IL-1β (D,E) in the presence or absence of serum. Panels C and F show the fold change increase in NFAT-luc activity following treatment with PE/Ion (C) or IL-1β (F) in serum-free cultures relative to serum-containing cultures (mean ± SEM). Effects of PE/Ion and IL-1β were inhibited in the presence of serum, regardless of cell confluency. However, serum-mediated inhibition of evoked NFAT activity was far greater in confluent cells (C and F). *p < 0.05, #p < 0.001

Serum cytokines are responsible, in part, for astrocytic NFAT activation

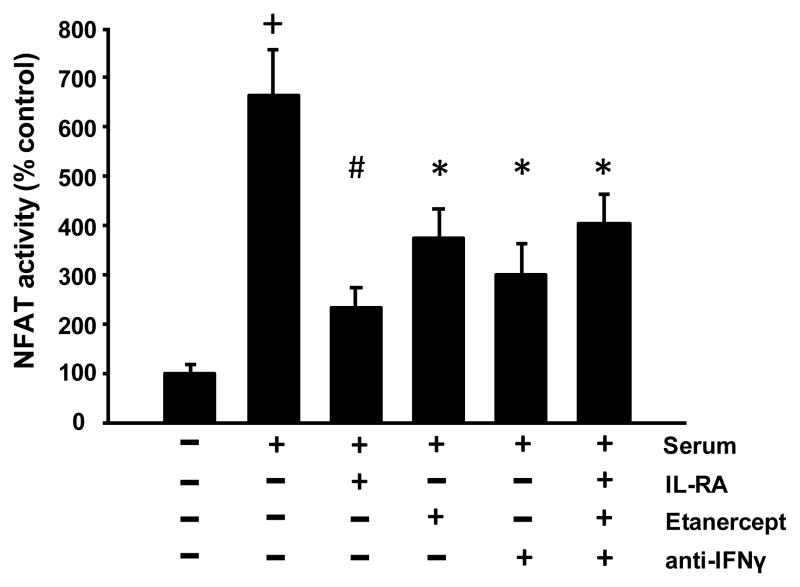

FBS contains numerous factors that may interact with astrocytic CN/NFAT signaling, including a variety of cytokines. To test whether cytokines contribute to serum-mediated NFAT activation, we conducted a “serum shock” experiment in which primary astrocytes were grown to >90% confluency, pre-loaded with an NFAT-luciferase reporter construct, and maintained in serum-free medium. After 16 h, serum-free medium was replaced with serum-containing media (i.e. 10% FBS) in the presence or absence of antagonists to IL-1β (IL-RA, 40 nM), TNFα (Etanercept, 2 μM), and/or IFNγ (anti-IFNγ antibody, 250 μM). Control cultures received a media exchange without the addition of serum. Resultant luciferase levels were measured approximately 5 h later and are illustrated in Figure 3 as the percent increase in luciferase expression relative to control.

Figure 3. Serum effects on astrocytic NFAT activity are reduced by cytokine inhibitors.

Astrocytes cultured under serum-free conditions were exposed to serum-containing media for 5 h in the presence or absence of antagonists to IL-1β (IL-RA), TNFα (Etanercept), IFNγ (anti-IFNγ), or a combination of all three. Astrocytic NFAT activity (mean ± SEM, percent of control) was significantly increased following serum shock, but was significantly alleviated when co-cultured with cytokine antagonists. +p < 0.001 relative to control, *p < 0.05 and #p < 0.001 relative to serum

Consistent with data shown in Figure 1, serum-shock induced a significant increase in NFAT activation (Figure 3, p < 0.001). Moreover, these effects were significantly attenuated by co-application of cytokine inhibitors, regardless of whether these reagents were delivered separately or in combination (p < 0.05 for all antagonists). These results demonstrate that serum stimulates NFAT activity through a cytokine-based mechanism. It should be noted, however, that none of the inhibitors (alone or together) fully suppressed the effects of serum-shock, suggesting that there are additional serum factors interacting with NFATs.

Discussion

CN is increasingly believed to play a critical role in neurodegenerative conditions, such as Alzheimer’s disease (AD) [1, 18, 22, 29]. One of the hallmarks of AD is increased neuroinflammation, as indicated by activated glia and elevated cytokine levels [4, 21, 31]. In recent years, our group and others have used primary cell cultures to show that astrocytic CN/NFAT activity helps coordinate immune/inflammatory signaling in astrocytes [1, 5, 8, 22, 23, 28]. The major advantage of cell culture models is the relative ease of investigating molecular interactions in a well-controlled environment. Nonetheless, cell culture models have obvious limitations and are highly sensitive to environmental conditions that can vary from lab-to-lab. Indeed, even small adjustments in temperature, pH, confluency, age, and/or media composition can have a profound impact on the biological outcome being studied [2, 17]. Here, we sought to determine how NFAT activity in primary astrocytes is affected by changes in culture conditions, specifically serum content and cell confluence.

Previous work found that increasing serum levels potentiated the downregulation of CN protein expression in primary astrocytes exposed to ammonia [3]. The present study shows that astrocytic NFAT activity is also affected by serum, though serum effects shown here depended on the type of NFAT activity measured (i.e. basal or evoked) and also on the confluency of the cells. Our results found that basal NFAT activity is potentiated, while evoked activity is inhibited in cells maintained in serum. For evoked activity, serum-mediated inhibition was observed following application of both an artificial (PE/Ion) and an endogenous stimulus (IL-1β). And while stimulatory and inhibitory effects of serum were observed in both confluent and sub-confluent cells, these effects were clearly much greater under confluent conditions. The increased sensitivity of NFAT in confluent cultures is not presently clear. However, in sub-confluent smooth muscle cell cultures, the nuclear translocation of NFAT2 proteins is also apparently impaired [15]. This finding suggests that cell proliferation processes may exert inhibitory control over NFAT activation. Future research will be necessary to test this possibility and to determine the extent to which other critical variables influence the CN/NFAT pathway in primary astrocytes.

In the present study, NFAT activity was assessed using an NFAT-luciferase reporter construct, delivered to astrocytes via replication-deficient adenovirus. Whether using transfection or viral infection techniques, the efficiency of transgene delivery can be highly vulnerable to a variety of cell culture conditions. This issue could present a major confound in our study if viral infection is facilitated by serum and/or inhibited in confluent cultures. While adenovirus uptake was not specifically measured here, we typically see very high infection efficiency in primary astrocytes (~90% cells infected as indicated by GFP expression or β-galactosidase staining) regardless of serum conditions or confluency (unpublished observations), especially when virus is delivered at a high MOI (between 50 and 100). These observations are consistent with the fact that adenovirus shows excellent tropism to dividing as well as non-dividing cells [6]. Moreover, FBS was previously found to inhibit, rather than facilitate adenovirus infection [9], suggesting that, if anything, we underestimated the potency of serum in regulating endogenous NFAT activity.

Stimulatory and inhibitory effects of serum on basal and evoked NFAT activity may be attributable to a common underlying mechanism, such as cytokine signaling. In multiple cell lines and primary cultures, CN activity is robustly recruited by several cytokine factors and endogenous inflammatory mediators [8, 16, 28, 32, 33]. Additionally, serum, like cytokines, triggers the upregulation of well-characterized inflammatory biomarkers including COX-2 and prostaglandins [24]. Serum was also recently shown to stimulate CN/NFAT signaling in cardiomyocyte cultures [19], again suggesting the involvement of cytokines. In the present study, serum-shock triggered an increase in astrocytic NFAT activity that was similar in extent to the increase associated with IL-1β [28] (and see Figure 2D, 2E). Moreover, serum-shock effects were severely attenuated in cultures co-treated with an IL-1β antagonist. In fact, blockade of other critical cytokines, including TNFα and INFγ also blunted the serum-mediated increase in NFAT activation, demonstrating that multiple cytokine factors in serum promote NFAT activity. Given the relative effectiveness of each cytokine inhibitor, it was somewhat surprising that serum-mediated NFAT activity was not suppressed to a greater extent by the combined delivery of all three inhibitors. Cytokine signaling cascades are notorious for their intricacy and may vary substantially in their functions based on the target tissue investigated, the number/type of cytokine receptors expressed, and the presence of other cytokines and chemokines, among other factors [31]. The lack of an additive effect shown here may therefore allude to a complex interaction amongst IL-1β, TNFα, INFγ and NFATs. Clearly, future research will be needed to fully understand the distinct and interdependent actions of these cytokines on NFAT signaling during neuroinflammation and neurodegenerative disease.

The failure of PE/Ion and IL-1β to induce robust NFAT activation in serum-containing media (Figure 2) was most likely due to a ceiling effect: i.e. NFAT activation was already near maximal levels due to the stimulatory effects of serum. Any experiments performed in serum-containing medium may therefore underestimate the degree to which CN/NFAT signaling is evoked by exogenously applied stimuli and factors. The stimulatory effects of serum on NFATs may also have critical implications for the phenotypic state of primary astrocyte cultures. Our previous work demonstrates that astrocytes transition to an activated state when CN expression/activity levels are aberrantly high [22], whereas resting astrocytes observed in healthy nervous tissue express little, if any, CN [12, 22, 25]. Canellada et al. speculated that the presence of CN signaling components in primary astrocytes indicates that these cells are locked in a chronically activated (yet undifferentiated) state [5]. The present findings support this idea and further suggest that serum, through its stimulatory actions on CN, is what maintains the activated phenotype.

In summary, our results reveal that NFAT activation in primary astrocytes is strongly influenced by specific culture conditions. Serum, in particular, potently increases basal NFAT activity yet interferes with evoked activity, especially when cells are confluent. These effects could lead to variable or difficult-to-interpret results, as well as an undesirable cellular phenotype. Important consideration must therefore be given to the cell culture environment of primary astrocytes when studying CN/NFAT signaling.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health Grants AG027297 and AG024190, and a gift from the Kleberg Foundation.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Abdul HM, Sama MA, Furman JL, Mathis DM, Beckett TL, Weidner AM, Patel ES, Baig I, Murphy MP, LeVine H, 3rd, Kraner SD, Norris CM. Cognitive decline in Alzheimer’s disease is associated with selective changes in calcineurin/NFAT signaling. J Neurosci. 2009;29:12957–12969. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1064-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Banker G, Goslin K. Primary Dissociated Cell Cultures of Neural Tissue. In: Banker G, Goslin K, editors. Culturing Nerve Cells. MIT Press; Cambridge, MA: 1991. pp. 41–74. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bodega G, Suarez I, Paniagua C, Vacas E, Fernandez B. Effect of ammonia, glutamine, and serum on calcineurin, p38MAPK-diP, GADD153/CHOP10, and CNTF in primary rat astrocyte cultures. Brain Res. 2007;1175:126–133. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2007.07.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cameron B, Landreth GE. Inflammation, microglia, and alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Dis. 2009 doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2009.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Canellada A, Ramirez BG, Minami T, Redondo JM, Cano E. Calcium/calcineurin signaling in primary cortical astrocyte cultures: Rcan1–4 and cyclooxygenase-2 as NFAT target genes. Glia. 2008;56:709–722. doi: 10.1002/glia.20647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chengalvala MV, Lubeck MD, Selling BJ, Natuk RJ, Hsu KH, Mason BB, Chanda PK, Bhat RA, Bhat BM, Mizutani S, et al. Adenovirus vectors for gene expression. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 1991;2:718–722. doi: 10.1016/0958-1669(91)90041-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eddleston M, Mucke L. Molecular profile of reactive astrocytes--implications for their role in neurologic disease. Neuroscience. 1993;54:15–36. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(93)90380-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fernandez AM, Fernandez S, Carrero P, Garcia-Garcia M, Torres-Aleman I. Calcineurin in reactive astrocytes plays a key role in the interplay between proinflammatory and anti-inflammatory signals. J Neurosci. 2007;27:8745–8756. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1002-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ferreira TB, Alves PM, Goncalves D, Carrondo MJT. Effect of MOI and medium composition on adenovirus infection kinetics. In: Gòdia F, Fussenegger M, editors. Animal Cell Technology Meets Genomics; Proceedings of the 18th ESACT Meeting Granada; Spain. May 11–14, 2003; Netherlands, Dordrecht: Springer; 2005. pp. 329–332. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gonzalez FA, Seth A, Raden DL, Bowman DS, Fay FS, Davis RJ. Serum-induced translocation of mitogen-activated protein kinase to the cell surface ruffling membrane and the nucleus. J Cell Biol. 1993;122:1089–1101. doi: 10.1083/jcb.122.5.1089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hasan NM, Adams GE, Joiner MC. Effect of serum starvation on expression and phosphorylation of PKC-alpha and p53 in V79 cells: implications for cell death. Int J Cancer. 1999;80:400–405. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19990129)80:3<400::aid-ijc11>3.0.co;2-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hashimoto T, Kawamata T, Saito N, Sasaki M, Nakai M, Niu S, Taniguchi T, Terashima A, Yasuda M, Maeda K, Tanaka C. Isoform-specific redistribution of calcineurin A alpha and A beta in the hippocampal CA1 region of gerbils after transient ischemia. J Neurochem. 1998;70:1289–1298. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1998.70031289.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Im SH, Rao A. Activation and deactivation of gene expression by Ca2+/calcineurin-NFAT-mediated signaling. Mol Cells. 2004;18:1–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Keller JN, Steiner MR, Mattson MP, Steiner SM. Lysophosphatidic acid decreases glutamate and glucose uptake by astrocytes. J Neurochem. 1996;67:2300–2305. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1996.67062300.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Larrieu D, Thiebaud P, Duplaa C, Sibon I, Theze N, Lamaziere JM. Activation of the Ca(2+)/calcineurin/NFAT2 pathway controls smooth muscle cell differentiation. Exp Cell Res. 2005;310:166–175. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2005.07.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Leal RB, Frizzo JK, Tramontina F, Fieuw-Makaroff S, Bobrovskaya L, Dunkley PR, Goncalves CA. S100B protein stimulates calcineurin activity. Neuroreport. 2004;15:317–320. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200402090-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Levison S, McCarthy K. Astroglia in Culture. In: Banker G, Goslin K, editors. Culturing Nerve Cells. MIT Press; Cambridge, MA: 1991. pp. 309–336. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu F, Grundke-Iqbal I, Iqbal K, Oda Y, Tomizawa K, Gong CX. Truncation and activation of calcineurin A by calpain I in Alzheimer disease brain. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:37755–37762. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M507475200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu Q, Busby JC, Molkentin JD. Interaction between TAK1-TAB1-TAB2 and RCAN1-calcineurin defines a signalling nodal control point. Nat Cell Biol. 2009;11:154–161. doi: 10.1038/ncb1823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Messina S, Molinaro G, Bruno V, Battaglia G, Spinsanti P, Di Pardo A, Nicoletti F, Frati L, Porcellini A. Enhanced expression of Harvey ras induced by serum deprivation in cultured astrocytes. J Neurochem. 2008;106:551–559. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2008.05420.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mrak RE, Griffinbc WS. The role of activated astrocytes and of the neurotrophic cytokine S100B in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2001;22:915–922. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(01)00293-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Norris CM, Kadish I, Blalock EM, Chen KC, Thibault V, Porter NM, Landfield PW, Kraner SD. Calcineurin triggers reactive/inflammatory processes in astrocytes and is upregulated in aging and Alzheimer’s models. J Neurosci. 2005;25:4649–4658. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0365-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Perez-Ortiz JM, Serrano-Perez MC, Pastor MD, Martin ED, Calvo S, Rincon M, Tranque P. Mechanical lesion activates newly identified NFATc1 in primary astrocytes: implication of ATP and purinergic receptors. Eur J Neurosci. 2008;27:2453–2465. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2008.06197.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Polansky JR, Kurtz RM, Alvarado JA, Weinreb RN, Mitchell MD. Eicosanoid production and glucocorticoid regulatory mechanisms in cultured human trabecular meshwork cells. Prog Clin Biol Res. 1989;312:113–138. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Polli JW, Billingsley ML, Kincaid RL. Expression of the calmodulin-dependent protein phosphatase, calcineurin, in rat brain: developmental patterns and the role of nigrostriatal innervation. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 1991;63:105–119. doi: 10.1016/0165-3806(91)90071-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ridet JL, Malhotra SK, Privat A, Gage FH. Reactive astrocytes: cellular and molecular cues to biological function. Trends Neurosci. 1997;20:570–577. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(97)01139-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sadoshima J, Aoki H, Izumo S. Angiotensin II and serum differentially regulate expression of cyclins, activity of cyclin-dependent kinases, and phosphorylation of retinoblastoma gene product in neonatal cardiac myocytes. Circ Res. 1997;80:228–241. doi: 10.1161/01.res.80.2.228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sama MA, Mathis DM, Furman JL, Abdul HM, Artiushin IA, Kraner SD, Norris CM. Interleukin-1beta-dependent signaling between astrocytes and neurons depends critically on astrocytic calcineurin/NFAT activity. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:21953–21964. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M800148200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Taglialatela G, Hogan D, Zhang WR, Dineley KT. Intermediate- and long-term recognition memory deficits in Tg2576 mice are reversed with acute calcineurin inhibition. Behav Brain Res. 2009;200:95–99. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2008.12.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wilkins BJ, Dai YS, Bueno OF, Parsons SA, Xu J, Plank DM, Jones F, Kimball TR, Molkentin JD. Calcineurin/NFAT coupling participates in pathological, but not physiological, cardiac hypertrophy. Circ Res. 2004;94:110–118. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000109415.17511.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wyss-Coray T. Inflammation in Alzheimer disease: driving force, bystander or beneficial response? Nat Med. 2006;12:1005–1015. doi: 10.1038/nm1484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yan Y, Li J, Ouyang W, Ma Q, Hu Y, Zhang D, Ding J, Qu Q, Subbaramaiah K, Huang C. NFAT3 is specifically required for TNF-alpha-induced cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) expression and transformation of Cl41 cells. J Cell Sci. 2006;119:2985–2994. doi: 10.1242/jcs.03014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yang Y, Ochando J, Yopp A, Bromberg JS, Ding Y. IL-6 plays a unique role in initiating c-Maf expression during early stage of CD4 T cell activation. J Immunol. 2005;174:2720–2729. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.5.2720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]