Abstract

The present study examined the prevalence of individual nicotine dependence symptoms among recent onset smokers across the continuum of nondaily and daily cigarette smoking behavior in a nationally representative sample of recent onset smokers from the National Surveys on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH). Rates of endorsement for 17 symptoms drawn primarily from the Nicotine Dependence Symptom Scale (Shiffman, Waters, & Hickcox, 2004) were calculated for four levels of nondaily (smoked 1-3, 4-10, 11-20, or 21-29 days in the past 30 days) and daily (smoked 1, 2-5, 6-15, or >15 cigarettes per day in the past 30 days) smoking. Logistic and linear regression analyses with polynomial contrasts controlling for age, gender, length of exposure, and smoking quantity tested trends in symptom endorsement across levels of smoking. Significant linear and quadratic trends indicated that increasing rates of endorsement differed most between the lowest levels of nondaily and daily smoking. Results suggest that, for some, infrequent smoking may not represent benign experimentation. Recognizing early symptoms of nicotine dependence may assist in early identification and intervention of those at risk for heavier smoking in the future. Adolescents can be taught to recognize the early symptoms of nicotine dependence to increase awareness of the rapidity at which these symptoms may appear.

Keywords: tobacco, smoking, adolescents, dependence, initiation

1. Introduction

The most important factor currently believed to contribute to smoking persistence and failed cessation efforts is the level of experienced dependence symptoms. Most commonly, nicotine dependence is characterized by physiological adaptations (i.e., tolerance, withdrawal), and other accommodating behaviors (i.e., time spent in activities necessary to obtain/use nicotine and recover from its effects and the forfeiting or reduction of important social, occupational, or recreational activities) resulting from chronic smoking. In fact, nicotine dependence and associated withdrawal have been consistently implicated in the maintenance of smoking behavior. For example, recent cross-sectional and longitudinal research has suggested that nicotine dependence significantly predicts smoking quantity and frequency (O'Loughlin, et al., 2003; Shiffman & Sayette, 2005), failed quit attempts (DiFranza, Savageau, Rigotti, et al., 2002; Haddock, Lando, Klesges, Talcott, & Renaud, 1999), and biochemical markers of nicotine exposure (Chen & Kandel, 2002; Etter, Vu Duc, & Perneger, 1999; Prokhorov, De Moor, Suchanek Hudmon, Koehly, & Hu, 2000).

Ongoing longitudinal studies of adolescent smoking that have examined the development of nicotine dependence symptoms suggest that there are different developmental trajectories for nicotine dependence (Hu, Muthen, Schaffran, Griesler, & Kandel, 2008), and that, for some adolescents, nicotine dependence symptoms emerge very soon after onset of smoking and at low levels of nicotine exposure (DiFranza, Savageau, Rigotti, et al., 2002). In fact, nicotine exposure is a markedly imperfect index for determining an individual's probability of developing nicotine dependence. Based on reports from the Development and Assessment of Nicotine Dependence in Youth (DANDY) study, for example, symptoms of nicotine dependence were found to emerge for some adolescents during relatively early smoking experiences and well before the establishment of daily smoking patterns (DiFranza, et al., 2000; DiFranza, Savageau, Rigotti, et al., 2002). Reports from the McGill Study on the Natural History of Nicotine Dependence in Teens (NDIT) have confirmed individual differences in the emergence of dependence, and have identified adolescents who meet criteria for ICD-10 nicotine dependence even among sporadic and monthly smokers (O'Loughlin, et al., 2003).

In an effort to better understand the development of nicotine dependence, recent empirical work has begun to investigate specific symptoms that may emerge early and at relatively low levels of smoking exposure. This work has shown that perceived “mental” addiction, craving, and loss of control may emerge within a month of beginning smoking (DiFranza, et al., 2000; DiFranza, Savageau, Fletcher, et al., 2002; Gervais, O'Loughlin, Meshefedjian, Bancej, & Tremblay, 2006), and at less than daily levels of use (O'Loughlin, et al., 2003). Based on relatively small and geographically restricted samples, these studies of recent onset smokers have most often examined the emergence of nicotine dependence symptoms based on length of exposure to cigarettes (DiFranza, Savageau, Rigotti, et al., 2002; Gervais, et al., 2006) and have not yet considered prevalence of symptoms across diverse levels of both daily and nondaily smoking. One study that did examine rate of exposure (O'Loughlin, et al., 2003) was limited to a small number of infrequent smoking categories. In addition, research in this area has generally examined a limited number of nicotine dependence symptoms, despite recent evidence that core diagnostic symptoms, such as tolerance and withdrawal, are often among the last symptoms to emerge (Gervais, et al., 2006).

The present study extends previous research on the experience of nicotine dependence symptoms among recent onset smokers by examining a nationally representative sample of 8,081 adolescents and young adults reporting smoking initiation within the past two years. Data were drawn from five annual National Surveys on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH), one of the largest, nationally representative, epidemiologic studies available to date that includes substantial heterogeneity in adolescent nicotine exposure, as well as assessment of nicotine dependence symptoms among infrequent smokers and among adolescents as young as age 12. The aim of the study was to evaluate the prevalence of individual nicotine dependence symptoms among recent onset smokers across the continuum of nondaily and daily smoking behavior.

2.0 Methods

2.1 Participants

The sample, drawn from data combining five annual NSDUH surveys (2002-2006), consisted of N=8,081 individuals age 12 to 21 who reported 1) smoking at least once in the past month and 2) their first exposure to smoking within the past two years . The NSDUH utilizes multistage area probability sampling methods to select a representative sample of the noninstitutionalized U.S. civilian population aged 12 or older. Persons living in households, military personnel living off base, and residents of noninstitutional group quarters including college dormitories, group homes, civilians dwelling on military installations, as well as persons with no permanent residence are included. The NSDUH oversamples adolescents ages 12 to 17 to improve precision of substance use estimates.

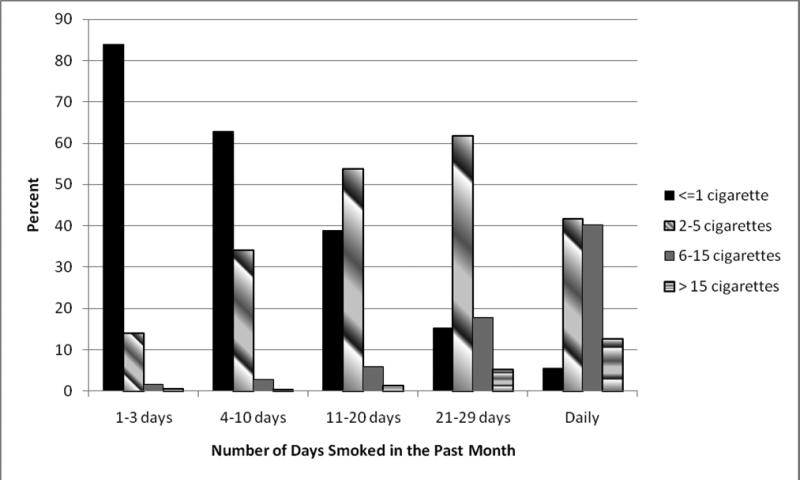

Sample characteristics, adjusted for the complex survey design, are presented in Table 1. The majority (81%) were nondaily smokers. Most nondaily smokers (63.6%) reported smoking no more than 1 cigarette on the days they did smoke and 95% reported smoking 5 or fewer cigarettes on the days they smoked. However, smoking quantity on days smoked increased as frequency of nondaily smoking increased (see Figure 1). Participants smoked an average 12.2 of the past 30 days (SE=0.16, range 1-30). Half (51%) had been smoking for more than one, but no more than two, years and the rest began smoking in the past year.

Table 1.

Sample Characteristics (N=8081)

| Variable | N (design adjusted %) |

|---|---|

| Female | 4083 (48.3) |

| Age | |

| 12-17 years | 5041 (55.0) |

| 18-21 years | 3040 (45.0) |

| Ethnicity | |

| Non Hispanic White | 5395 (66.6) |

| Non Hispanic Black | 887 (12.0) |

| Hispanic | 1183 (15.8) |

| Other Ethnicity | 616 (5.5) |

| Cigarette Smoking | |

| Non-daily | 6552 (81.1) |

| Smoked 1-3 days in past 30 days | 3110 (47.0) |

| Smoked 4-10 days in past 30 days | 1713 (26.1) |

| Smoked 11-20 days in past 30 days | 1063 (16.6) |

| Smoked 21-29 days in past 30 days | 666 (10.3) |

| Daily | 1529 (18.9) |

| Smoke 1 cigarette per day | 86 (5.5) |

| Smoke 2-5 cigarettes per day | 637 (41.6) |

| Smoke 6-15 cigarettes per day | 608 (40.2) |

| Smoke >15 cigarettes per day | 195 (12.7) |

| Length of Exposure (maximum 2 yrs) | |

| Began smoking within the past year | 4201 (50.9) |

| Began smoking more than 1 year ago | 3880 (49.1) |

Figure 1.

Number of cigarettes smoked on smoking days for each level of nondaily smoking and for daily smoking.

2.2 Measures

2.2.1 Smoking variables

Cigarette exposure was assessed with three items. Smoking frequency was assessed by asking participants how many days they smoked cigarettes in the past 30 days. Smoking quantity was assessed by asking participants to report the average number of cigarettes they smoked on the days that they smoked cigarettes in the past 30 days. Length of exposure was assessed by subtracting the age at which participants first reported smoking a cigarette from their current age, and dichotomizing into one year or less vs. between one and two years.

Nicotine Dependence

In the NSDUH, nicotine dependence was assessed using 19 items drawn primarily from the Nicotine Dependence Scale (NDSS; Shiffman, et al., 2004). Participants were asked to rate how true each of the symptoms was of their smoking during the past 30 days. Items were rated using the following response options: 1) not at all true, 2) sometimes true, 3) moderately true, 4) very true, 5) extremely true. Four items (“You feel a sense of control over your smoking – that is you can “take it or leave it” at any time”; “It's normal for you to smoke several cigarettes in an hour, then not have another one until hours later”; “It's hard to say how many cigarettes you smoke per day because the number often changes”; and “The number cigarettes you smoke per day is often influenced by other things – how you're doing, what you're feeling, for example”) were reverse coded such that higher scores indicated that the item was not true of the participants’ smoking. The NDSS provides a single summary score for overall nicotine dependence that includes items measuring drive (i.e. craving and withdrawal symptoms), tolerance (i.e. reduced sensitivity to tobacco products), priority (i.e. preference for smoking over other reinforcers), continuity (i.e. regularity of smoking), and stereotypy (i.e. the “sameness” of smoking contexts). The NDSS has been shown to have good psychometric properties in both adolescent (Clark, et al., 2005; Sterling, et al., 2009) and adult (Shiffman & Sayette, 2005; Shiffman, et al., 2004 ) populations, and has been found to predict future smoking (Sledjeski, et al., 2007). Due to considerable missing data from an option allowing participants to skip two of the items measuring stereotypy and priority regarding nonsmoking friends (“Do you have any friends who do not smoke cigarettes?” and “There are times when you choose not to be around your friends who don't smoke, because they won't like it if you smoke”, respectively), these items were excluded from the analysis.

In their study of adolescents, Strong et al. (2009) found that the distribution of most NDSS symptom responses were skewed such that the majority of participants endorsed the “not at all true” option and that dichotomizing the NDSS responses increased model stability without a loss of information or reliability. We found responses to be similarly distributed in the current sample and thus chose to collapse the four response options categories of “sometimes true” to extremely true” into a single category to generate a dichotomous variable for symptom endorsement (No – not at all true vs. Yes – any of the four positive responses).

2.3 Analysis

In the first step of the analysis, we examined endorsement rates of each symptom across four levels of nondaily smoking (smoked 1-3, 4-10, 11-20, or 21-29 days in the past 30 days) and daily smoking (smoked 1, 2-5, 6-15, or >15 cigarettes per day in the past 30 days). We then used logistic regression with polynomial contrasts to test linear, quadratic, and cubic trends in the probability of symptom endorsement as a function of increasing smoking exposure separately for nondaily and daily smoking. We tested these trends in order to determine whether the slope of the relation between frequency of smoking and likelihood of symptom endorsement leveled off or declined at a higher frequency of smoking (quadratic trend) or whether it leveled off at moderate frequency levels, but then increased significantly at the highest frequency levels (cubic trend). The midpoint of each category was used to calculate the polynomial contrast coefficients, with the exception of the >15 cigarettes per day category for daily smokers where the contrast coefficient was specified for 20.5 cigarettes per day because the majority of adolescents in the >15 group smoked no more than 25 cigarettes per day. We used the Benjamini-Hochberg procedure to adjust the significance level for multiple significance tests (Benjamini & Hochberg, 1995; Thissen, Steinberg, & Kuang, 2002). This procedure takes into account the number of significance tests and has been shown to be more powerful than the Bonferroni correction (Benjamini & Hochberg, 1995). Finally, linear regression was used to test linear, quadratic, and cubic trends in the mean number of endorsed symptoms at increasing levels of smoking exposure. In each model, we controlled for age, gender and length of time since smoking initiation (0 to 1 vs. >1 to 2 years). In models based on nondaily smokers, smoking quantity on days smoked was also included as a covariate, given that it tended to increase as smoking frequency increased. All analyses used appropriate sample weights to correct for differences in the probability of selection, and adjusted for survey design effects to obtain accurate standard errors.

3. Results

3.1 Symptom Endorsement among Nondaily Smokers

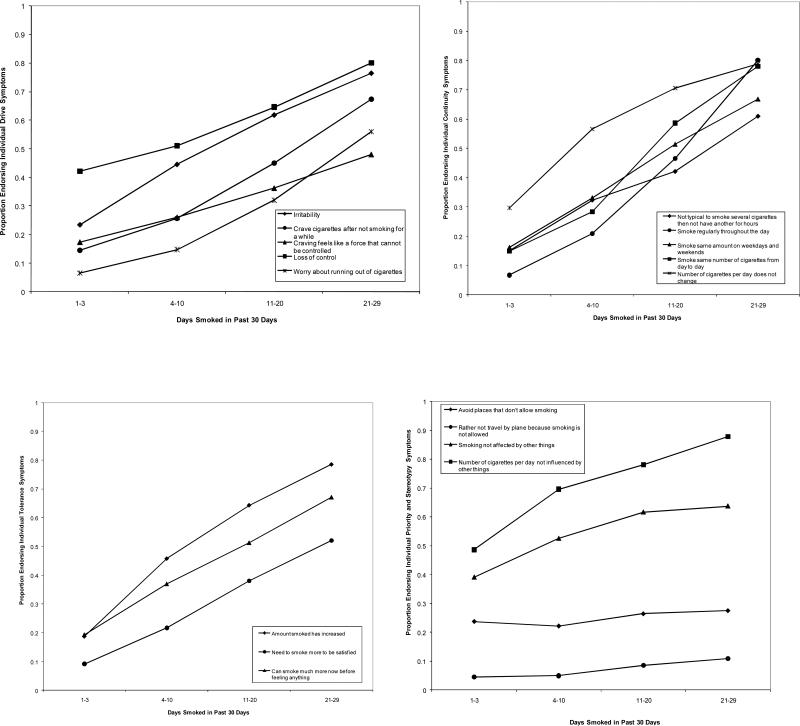

Figure 2 shows the proportion of nondaily smokers endorsing each nicotine dependence symptom based on smoking frequency in the past month. Symptoms that were experienced most frequently at the lowest levels of use (i.e. smoking on only 1 to 3 days) included loss of control over smoking (42%), two symptoms indicating that smoking and number of cigarettes per day is unaffected by other things (48% and 39%), number of cigarettes smoked per day does not change (30%), avoiding places that don't allow smoking (24%), and feeling irritable after not smoking for awhile (23%). Results of the logistic regression models with polynomial contrasts indicated a significant linear increase in the probability of symptom endorsement associated with an increasing number of days smoked in the past month for all symptoms except avoiding places that don't allow smoking after controlling for age, gender, length of time since smoking initiation, and smoking quantity (Table 2). Overall, the rate of symptom endorsement increased dramatically with more frequent nondaily smoking, with several symptoms being endorsed by more than 70% of those reporting smoking nearly every day (i.e., between 21 to 29 days in the past month). These symptoms included irritability (76%), loss of control (80%), amount smoked has increased (79%), three symptoms tapping continuity of smoking (smoking regularly throughout the day (80%), smoke the same number of cigarettes from day to day (78%), and number of cigarettes smoked per day does not change (79%)), and number of cigarettes smoked per day not influenced by other things (88%).

Figure 2.

Proportion endorsing nicotine dependence symptoms at each level of nondaily smoking.

Table 2.

Logistic Regression Polynomial Contrasts

| Symptom | Linear Trend | Quadratic Trend | Cubic Trend | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B (Nondaily) |

B (Daily) |

B (Nondaily) |

B (Daily) |

B (Nondaily) |

B (Daily) |

|

| Drive | ||||||

| 1. After not smoking for a while, you need to smoke to feel less restless and irritable | 1.44* | 1.02* | −0.32* | −0.37 | 0.18 | 0.06 |

| 2. When you don't smoke for a few hours, you start to crave cigarettes | 1.51* | 1.48* | −0.09 | −0.70* | 0.04 | −0.03 |

| 3. You sometimes have strong cravings for a cigarette where it feels like you are in the grip of a force that you can't control | 0.89* | 0.70* | −0.12 | −0.32 | 0.06 | −0.23 |

| 4. You feel a sense of control over your smoking – that is you can “take it or leave it” at any time (reverse coded) | 1.07* | 0.64* | 0.08 | −0.93* | 0.02 | 0.16 |

| 5. You sometimes worry that you will run out of cigarettes | 1.83* | 0.85* | −0.17 | −0.72* | 0.06 | 0.42 |

| Priority | ||||||

| 1. You tend to avoid places that don't allow smoking, even if you would otherwise enjoy them | 0.24 | 0.48 | 0.01 | 0.10 | −0.11 | 0.02 |

| 2. Even if you're travelling a long distance, you'd rather not to travel by plane because you wouldn't be allowed to smoke | 0.47* | 1.16* | −0.02 | −0.24 | −0.17 | −0.05 |

| Continuity | ||||||

| 1. It's normal for you to smoke several cigarettes in an hour, then not have another one until hours later (reverse coded) | 1.04* | 0.70* | −0.20 | −0.37 | 0.30* | 0.11 |

| 2. You smoke cigarettes fairly regularly throughout the day | 2.45* | 1.34* | −0.14 | −1.27* | 0.21 | 0.35 |

| 3. You smoke about the same amount on weekends as on weekdays | 1.43* | 0.58* | −0.32* | −0.36 | 0.14 | 0.13 |

| 4. You smoke just about the same number of cigarettes from day to day | 1.98* | 0.77 | −0.24* | 0.24 | −0.07 | 0.02 |

| 5. It's hard to say how many cigarettes you smoke per day because the number often changes (reverse coded) | 1.22* | 0.06 | −0.49* | −0.85* | 0.23* | 0.01 |

| Tolerance | ||||||

| 1. Since you started smoking, the amount you smoke has increased | 1.69* | 0.76* | −0.49* | −0.67* | 0.29* | 0.37 |

| 2. Compared to when you first started smoking, you need to smoke a lot more now in order to be satisfied | 1.37* | 1.04* | −0.39* | −0.42 | 0.13 | 0.06 |

| 3. Compared to when you first started smoking, you can smoke much, much more now before you start to feel anything | 1.22* | 0.52 | −0.26* | −0.30 | 0.19 | 0.24 |

| Stereotypy | ||||||

| 1. Your smoking is not affected much by other things. For example, you smoke the same amount whether you're relaxing or working, happy or sad, alone or with others. | 0.63* | −0.12 | −0.31* | 0.29 | 0.07 | −0.20 |

| 2. The number cigarettes you smoke per day is often influenced by other things – how you're doing, what you're feeling, for example (reverse coded) | 1.10* | 0.46 | −0.21 | −0.38 | 0.25* | 0.12 |

Note: B= unstandardized regression coefficient.

significant using the Benjamini-Hochberg procedure for Type I error rate adjustment for multiple tests (Benjamini & Hochberg, 1995)

Significant negative quadratic trends primarily for symptoms measuring continuity and tolerance suggested that greater differences in rates of endorsement of these symptoms were seen between the lower levels of smoking frequency and that these rates differed less among smokers reporting more frequent, but still nondaily use. A significant positive cubic trend was found only for smoking not influenced by other things, amount smoked has increased and two symptoms measuring continuity of smoking (number of cigarettes smoked per day does not change, and not typical to smoke several cigarettes then not have another cigarette until hours later). The significant positive cubic trend for these four symptoms indicated that, after controlling for age, gender, length of time since smoking initiation, and smoking quantity, the difference in the rate of symptom endorsement was largest between the lowest levels of smoking frequency, was smaller between more moderate levels of smoking frequency, but grew larger again between the highest levels smoking frequency.

Finally, there were significant linear (unstandardized parameter estimate (B) = 5.38, p<0.0001) and quadratic trends (B = -0.67, p<0.0001) in the mean number of symptoms endorsed at each nondaily smoking level. The mean number of symptoms endorsed for adolescents smoking 1-3 days a month was 3.48 (standard error=0.08), which increased to 10.78 (standard error=0.18) for adolescents smoking 21-29 days in the past month.

3.2 Symptom Endorsement among Daily Smokers

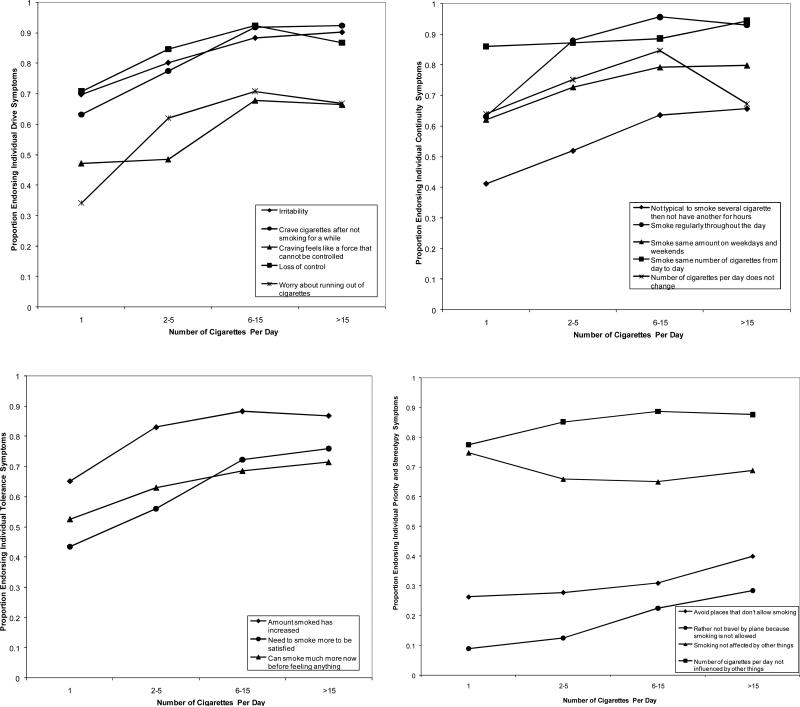

Figure 3 shows the proportion of daily smokers endorsing each symptom based on number of cigarettes smoked per day. Rates of symptom endorsement were high for adolescents who smoked only one cigarette per day, such that the rate of endorsement was greater than 50% for the majority of symptoms. The most frequently endorsed symptoms at this level were irritability (70%), loss of control (71%), smoke the same number of cigarettes from day to day (86%), number of cigarettes smoked per day not influenced by other things (78%), and smoking not affected by other things (75%). Like nondaily smokers, significant linear trends indicated that the rate of symptom endorsement was greater with an increasing number of cigarettes smoked per day for most symptoms (Table 2). This increasing trend appeared to level off or decline after 6-15 cigarettes per day for several symptoms, as evidenced by significant negative quadratic trends for craving, loss of control, worrying about running out of cigarettes, smoking regularly throughout the day, and amount smoked has increased. In addition, the symptom of “number of cigarettes smoked per day does not change”, which did not show a significant linear trend, had a significant quadratic trend, showing predominant curvilinearity as evidenced by a marked decline in endorsement for those smoking greater than 15 cigarettes per day. The rate of endorsement exceeded 65% for all symptoms among those with the highest level of daily smoking (>15 cigarettes per day), with the exception of preferring not to travel by plane because smoking is not allowed (28%) and avoiding places that don't allow smoking (40%).

Figure 3.

Proportion endorsing nicotine dependence symptoms at each level of daily smoking.

Finally, there were significant linear (unstandardized parameter estimate (B) = 2.03, p<0.0001) and quadratic trends (B = -1.33, p<0.0001) in the mean number of symptoms endorsed at each daily smoking level. The mean number of symptoms endorsed for adolescents smoking one cigarette per day was 9.54 (standard error=0.25), which increased to 12.55 (standard error=0.19) for those smoking more than 15 cigarettes per day.

4. Discussion

The present study examined endorsement of a comprehensive set of nicotine dependence symptoms among recent onset adolescent smokers reporting both nondaily and daily smoking behavior. Three major findings emerged. First, several symptoms were experienced by a substantial proportion of the population at extremely low levels of smoking exposure. Second, quadratic trends indicated that differences in rates of symptom endorsement were significantly greater between lower levels of smoking exposure for both nondaily and daily smokers. Third, symptom endorsement was similar for daily smokers who smoked more than 15 cigarettes per day compared to those smoking 6 to 15 cigarettes per day.

Among those smoking at the lightest levels (i.e., 1 to 3 days per month and typically only one cigarette per day), a number of symptoms were endorsed by 25% or more of the population. Confirming previous research, irritability after not smoking for a while, which may be considered a withdrawal symptom, and loss of control were found to be among the most prevalent symptoms. These symptoms have been found in other studies to be among the earliest symptoms to emerge after smoking initiation (DiFranza, et al., 2000; DiFranza, Savageau, Fletcher, et al., 2002; Gervais, et al., 2006). Our findings also showed that stereotypy, where smoking behavior becomes unaffected by other things going on in the adolescent's life, priority (avoiding places where smoking in not allowed) and continuity (number of cigarettes smoked per day does not change) are fairly prevalent at this infrequent level of smoking, confirming that when smoking does occur, it is a priority and a consistent behavior for many infrequent smokers.

Rates of symptom endorsement were significantly greater among those reporting more frequent nondaily smoking, particularly between the lower levels of nondaily smoking exposure. Among adolescents smoking 21-29 days per month, nearly all symptoms were endorsed by the majority of participants. In addition, the number of endorsed symptoms differed considerably from a mean of 3.48 endorsed symptoms for those smoking 1-3 days per month to a mean of 10.78 endorsed symptoms for those smoking nearly every day (i.e., 21-29 days per month). The most commonly endorsed symptoms were those measuring drive to smoke, tolerance, continuity of smoking, and stereotypy. This suggests that as smokers move toward daily levels of use by smoking between 21-29 days per month, over 70% may exhibit signs of withdrawal, tolerance, and regularity of smoking. In addition, for most symptoms, the differences in the rate of endorsement was greatest at lower levels of nondaily use, eventually leveling off as the number of days smoked per month increased beyond 20, even after controlling for smoking quantity. Taken together, the findings add to the accumulating evidence that some adolescents may experience symptoms even if they smoke only once in awhile. Given that most smoking interventions target the prevention of the first smoking experiences (Lantz, et al., 2000) or the treatment of heavily dependent, chronic smokers (e.g., Fiore, 2000), the present findings suggest needed attention to smokers past the earliest exposures, but before daily smoking patterns are formed. Currently, the malleability of smoking behavior during this uptake process is unknown, but may represent appropriate timing for indicated intervention programming (Fiore, 2000; Okuyemi, et al., 2002).

Among daily smokers, the vast majority of symptoms were endorsed by over 50% of adolescents who reported smoking one cigarette per day and the average number of symptoms endorsed was 9.54. Thus, by the time some adolescents are smoking daily, they are exhibiting a large number of nicotine dependence symptoms, even though they are smoking only one cigarette per day. It is interesting to note that, while the rate of symptom endorsement was significantly greater at higher levels of daily smoking for most symptoms, this difference in rates leveled off considerably at heaviest levels of daily smoking, such that the rate of endorsement was not significantly greater for those smoking more than 15 cigarette per day compared to those smoking less than 15 cigarettes. In addition, the average number of endorsed symptoms differed by only 3 symptoms from smoking 1 cigarette per day to smoking more than 15 cigarettes per day. Thus, at least for the symptoms examined in this study, frequency of smoking may be a more salient indicator than quantity of smoking. That is, once adolescents have reached the point of smoking daily, most are likely to experience a substantial number of nicotine dependence symptoms regardless of the amount they smoke each day.

The rates of endorsement for the symptom of preferring not to travel by plane because smoking is not allowed was low at any level of nondaily or daily smoking. It is likely that this symptom is less applicable in an adolescent sample because individuals in this young age group are not likely to find themselves in this kind of situation often. In addition, for daily smokers, there was little difference in the rate of endorsement across levels for symptoms measuring stereotypy (smoking not affected by other things and number of cigarettes per day not influenced by other things). This may reflect a ceiling effect due to fact that the rate of endorsement for both symptoms was already very high (over 75%) at the lowest level of daily smoking (only one cigarette per day).

A major strength of this study is that it involved a large, nationally representative data set, which allowed us to examine nicotine dependence symptoms over a more diverse range of smoking levels than past research and to generalize more confidently to a broader population of recent onset adolescent smokers. The sample size also allowed us to focus exclusively on smokers who had begun smoking over the past two years, which reduced the potential confounding effect of past smoking behavior or dependence on symptom endorsement. Although it is still possible that symptom endorsement might have been related to heavier smoking within the past two years, participants were specifically asked to rate their experience of symptoms based on their smoking within the past 30 days. We were also able to evaluate a wide range of nicotine dependence symptoms that measured a number of aspects of dependence beyond more frequently evaluated symptoms of dependence such as tolerance and withdrawal. Finally, our study examined endorsement of nicotine dependence symptoms controlling for important covariates such as gender, age, length of exposure, and smoking quantity among nondaily smokers. The observed increase in number of cigarettes smoked on smoking days for increasing frequency of nondaily smoking indicated that it was particularly important to control for smoking quantity in nondaily smokers in order to disentangle the relation between smoking frequency and symptom endorsement from the influence of smoking quantity. Whereas past research has focused on the emergence of nicotine dependence symptoms over time, we examined symptom prevalence as a function of smoking exposure. As our research shows, there is considerable heterogeneity in smoking frequency and quantity among individuals who have been smoking for a similar amount of time.

Another way to possibly categorize nondaily smokers in terms of smoking exposure would be to create a global quantity by frequency score and either create groups from this variable or analyze it as a continuous exposure variable. This approach, however, would not allow an examination of smoking frequency independent of quantity, as we were able to do in this study by categorizing by frequency and controlling for quantity. In addition, the quantity distribution would be heavily skewed toward lighter smoking (i.e., l cigarette per day or less), which would have made it difficult to maintain adequate sample sizes across the full frequency/quantity continuum of nondaily smoking.

Despite the numerous strengths of this study, there are some weaknesses that should be noted. First, although the NDSS assesses a large and comprehensive number of symptoms that tap several aspects of nicotine dependence, it is only one of several existing measures of nicotine dependence symptoms. It is possible that the prevalence rates for symptom endorsement would be different across the continuum of nondaily and daily smoking had we used measures other than the NDSS. Second, the data are cross-sectional, which prevents us from fully investigating the temporal ordering of the emergence of these symptoms. Furthermore, these data cannot distinguish between several possible mechanisms that might underlie the endorsement of symptoms. Although symptom endorsement could reflect the neurobiological consequences of nicotine use, other factors may also influence symptom reporting. For example, expectations about smoking may influence the extent to which adolescents endorse symptoms as they begin to identify themselves as smokers, although new research has not found evidence to support this hypothesis (Ursprung, DiFranza, Costa, & DiFranza, 2009). Likewise, an adolescent particularly low in response inhibition or with high negative affect may be more likely to report a loss of control over smoking. Indeed, recent studies have demonstrated that individual differences in nicotine dependence are related to a history of major depression (Dierker & Donny, 2008) and the rate in which monetary rewards are discounted over time (Sweitzer, Donny, Dierker, Flory, & Manuck, 2008). Thus, the pathways from early nicotine use to the manifestation of symptoms of nicotine dependence are quite complex. Future research is required to explore other factors that relate to symptom expression and may signal sensitivity for nicotine dependence at relatively low levels of use soon after the onset of smoking. Finally, although some research suggests that the experience of NDSS nicotine dependence symptoms is related to future smoking behavior in young adults (Sledjeski, et al., 2007) and to both future smoking and cessation behavior in adolescents (Sterling, et al., 2009), these symptoms are not likely to be equally salient features of nicotine dependence, nor are they equally predictive of future smoking behavior. Additional research investigating the NDSS at the symptom level is necessary to understand which symptoms best represent latent nicotine dependence in recent onset smokers and the extent to which these early symptoms of nicotine dependence predict future smoking behavior.

One of the challenges faced by those on the forefront of adolescent smoking prevention (e.g., parents, teachers, physicians) is combating the widely held belief that only heavy daily smokers become dependent on nicotine. Compounding this challenge is the widespread sense of invulnerability among adolescents. As a result, many adolescents do not fully understand the extent to which simple experimentation or infrequent smoking may increase their risk of becoming regular, heavy smokers in the future, nor do they understand how difficult it may be to quit (Ursprung, et al., 2009). We found important differences in rates of endorsement of nicotine dependence symptoms across the continuum of smoking exposure, particularly among nondaily smokers. These differences provide additional evidence that, for some individuals, even very infrequent smoking may not represent benign experimentation. Recognizing early symptoms of nicotine dependence (e.g., feeling irritable, feeling some loss of control over smoking, and finding that smoking is a priority unaffected by other things) may assist in early identification and intervention of those at risk for heavier smoking in the future. Adolescents can also be taught to recognize the early symptoms of nicotine dependence in order to increase their awareness of the rapidity at which these symptoms may appear.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: A practical and powerful approach to multiple significance testing. (Series B).Journal of the Royal Statistical Society. 1995;57:289–300. [Google Scholar]

- Chen K, Kandel D. Relationship between extent of cocaine use and dependence among adolescents and adults in the United States. Drug & Alcohol Dependence. 2002;68(1):65–85. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(02)00086-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark DB, Wood DS, Martin CS, Cornelius JR, Lynch KG, Shiffman S. Multidimensional assessment of nicotine dependence in adolescents. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2005;77(3):235–242. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dierker L, Donny E. The role of psychiatric disorders in the relationship between cigarette smoking and DSM-IV nicotine dependence among young adults. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2008;10:439–446. doi: 10.1080/14622200801901898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiFranza JR, Rigotti NA, McNeill AD, Ockene JK, Savageau JA, St Cyr D, Coleman M. Initial symptoms of nicotine dependence in adolescents. Tobacco Control. 2000;9:313–319. doi: 10.1136/tc.9.3.313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiFranza JR, Savageau JA, Rigotti NA, Fletcher K, Ockene JK, McNeill AD, Coleman M, Wood C. Measuring the loss of autonomy over nicotine use in adolescents: The DANDY (Development and Assessment of Nicotine Dependence in Youths) study. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine. 2002;156:397–403. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.156.4.397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiFranza JR, Savageau JA, Rigotti NA, Fletcher K, Ockene JK, McNeill AD, Coleman M, Wood C. Development of symptoms of tobacco dependence in youths: 30 month follow up data from the DANDY study. Tobacco Control. 2002;11:228–235. doi: 10.1136/tc.11.3.228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Etter JF, Vu Duc T, Perneger TV. Validity of the Fagerstrom test for nicotine dependence and of the heaviness of smoking index among relatively light smokers. Addiction. 1999;94:269–281. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1999.94226910.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiore MC. A clinical practice guideline for treating tobacco use and dependence: A US Public Health Service Report. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2000;283:3244–3254. [Google Scholar]

- Gervais A, O'Loughlin J, Meshefedjian G, Bancej C, Tremblay M. Milestones in the natural course of onset of cigarette use among adolescents. CMAJ. 2006;175:255–261. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.051235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haddock C, Lando H, Klesges RC, Talcott G, Renaud EA. A study of the psychometric and predictive properties of the Fagerstrom test for nicotine dependence in a population of young smokers. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 1999;1:59–66. doi: 10.1080/14622299050011161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu M-C, Muthen BO, Schaffran C, Griesler P, Kandel D. Developmental trajectories of criteria of nicotine dependence in adolescence. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2008;98:94–104. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.04.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lantz PM, Jacobson PD, Warner KE, Wasserman J, Pollack HA, Berson J, Ahistrom A. Investing in youth tobacco control: A review of smoking prevention and control strategies. Tobacco Control. 2000;9:47–63. doi: 10.1136/tc.9.1.47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Loughlin J, DiFranza J, Tyndale RF, Meshefedjian G, McMillan-Davey E, Clarke PBS, Hanley J, Paradis G. Nicotine-dependence symptoms are associated with smoking frequency in adolescents. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2003;25(3):219–225. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(03)00198-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okuyemi KS, Harris KJ, Scheibmeir M, Choi WS, Powell J, Ahluwalia JS. Light smokers: Issues and recommendations. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2002:S103–S112. doi: 10.1080/1462220021000032726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prokhorov AV, De Moor CP, U.E., Suchanek Hudmon K, Koehly L, Hu S. Validation of the modified fagerstrom tolerance questionnaire with salivary cotinine among adolescents. Addictive Behaviors. 2000;25:429–433. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(98)00132-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiffman S, Sayette MA. Validation of the nicotine dependence syndrome scale (NDSS): A criterion-group design contrasting chippers and regular smokers. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2005;79:45–52. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiffman S, Waters AJ, Hickcox M. The Nicotine Dependence Syndrome Scale: A multidimensional measure of nicotine dependence. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2004;6:327–348. doi: 10.1080/1462220042000202481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sledjeski EM, Dierker LC, Costello D, Shiffman S, Donny E, Flay BR. Predictive validity of four nicotine dependence measures in a college sample. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2007;87(1):10–19. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sterling K, Mermelstein R, Turner L, Diviak K, Flay BR, Shiffman S. Examining psychometric properties and predictive validity of a youth-specific version of the Nicotine Dependence Syndrome Scale (NDSS) among teens with varying levels of smoking. Addictive Behaviors. 2009;34:616–619. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2009.03.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strong DR, Kahler CW, Colby SM, Griesler PC, Kandel D. Linking measures of adolescent nicotine dependence to a common latent continuum. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2009;99:296–308. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sweitzer MM, Donny EC, Dierker LC, Flory JD, Manuck SB. Delay discounting and smoking: Association with the Fagerstrom Test for Nicotine Dependence but not cigarettes smoked per day. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2008;10:1571–1575. doi: 10.1080/14622200802323274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thissen D, Steinberg L, Kuang D. Quick and Easy Implementation of the Benjamini-Hochberg Procedure for Controlling the False Positive Rate in Multiple Comparisons. Journal of Educational and Behavioral Statistics. 2002;27(1):77–83. [Google Scholar]

- Ursprung WWSA, DiFranza SM, Costa AD, DiFranza JR. Might expectations explain early self-reported symptoms of nicotine dependence? Addictive Behaviors. 2009;34(2):227–231. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2008.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]