Abstract

A multisystem approach was used to assess the efficiency of several methods for inactivation of Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus (VEEV) vaccine candidates. A combination of diverse assays (plaque, in vitro cytopathology and mouse neurovirulence) was used to verify virus inactivation, along with the use of a specific ELISA to measure retention of VEEV envelope glycoprotein epitopes in the development of several inactivated VEEV candidate vaccines derived from an attenuated strain of VEEV (V3526). Incubation of V3526 aliquots at temperatures in excess of 64°C for periods >30 minutes inactivated the virus, but substantially reduced VEEV specific monoclonal antibody binding of the inactivated material. In contrast, V3526 treated either with formalin at concentrations of 0.1% or 0.5% v/v for 4 or 24 hours, or irradiated with 50 kilogray gamma radiation rendered the virus non-infectious while retaining significant levels of monoclonal antibody binding. Loss of infectivity of both the formalin inactivated (fV3526) and gamma irradiated (gV3526) preparations was confirmed via five successive blind passages on BHK-21 cells. Similarly, loss of neurovirulence for fV3526 and gV3526 was demonstrated via intracerebral inoculation of suckling BALB/c mice. Excellent protection against subcutaneous challenge with VEEV IA/B Trinidad donkey strain was demonstrated using a two dose immunization regimen with either fV3526 or gV3526. The combination of in vitro and in vivo assays provides a practical approach to optimize manufacturing process parameters for development of other inactivated viral vaccines.

Keywords: Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus (VEEV), Formalin inactivated vaccines, Gamma irradiated vaccines, Neurovirulence, Alphavirus

1.0 Introduction

Over the past eighty years Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus (VEEV), an alphavirus (family Togaviridae) transmitted by mosquitoes, has caused periodic outbreaks of febrile and neurological disease in equine and human populations in Central and South America, as well as North America (Mexico and Texas) [Weaver et al., 2004]. Due to its highly infectious nature by aerosol [de Mucha-Macias and Sanchez-Spindola, 1965; Dietz et al., 1979], VEEV is also considered a potential biological weapon amenable to use in warfare and terrorism (Smith et al., 1997; Weaver et al., 2004). To address the above health concerns, two vaccines were developed by the U.S. government during the 1960s and 1970s: TC-83 (McKinney et al., 1963), a cell-culture attenuated vaccine developed from the Trinidad donkey (TrD) strain of subtype IA/B VEEV and a formalin inactivated vaccine derived from TC-83, designated C-84 (Cole, 1974). For several decades TC-83 and C-84 vaccines have been administered by the U.S. Army Special Immunizations Program for laboratory workers and animal health field workers at risk for contracting VEEV. While TC-83 induces long-lasting immunity against closely related VEEV subtypes (Burke et al., 1977), major limitations of the vaccine exist including: an approximate 80% protection rate and 25% incidence of adverse reactions (McKinney, 1972), reversion to virulence after mouse brain passages and the ability to kill mice after intracerebral (IC) inoculation (McKinney et al., 1963). In addition to these limitations, TC-83 cannot be used as a booster for subjects with waning antibody titers (Edelman et al., 1979) which led to the development of the C-84 vaccine for boosting antibody titers or immunization of TC-83 non-responders. C-84 also has limitations in that protection was short lived thus requiring multiple boosters, and there was a lack of mucosal protection at high dosages of aerosol challenge in hamsters (Jarling and Stephenson, 1984). An additional 24% of the non-responders to the TC-83 vaccine did not produce a neutralizing antibody response when vaccinated with C-84 (Edelman et al., 1979). These shortcomings, including the fact that C-84 was derived from TC-83 using 1960’s manufacturing technologies led the U.S. government to pursue the development of an infectious clone VEEV vaccine using recombinant DNA technology. In response to that mandate, V3526, a well-characterized live attenuated vaccine candidate was developed by site directed mutagenesis (Davis et al., 1995). Nonclinical studies with V3526 in mice (Hart et al., 2000; Hart et al., 2001), nonhuman primates (NHP) (Pratt et al., 2003) and horses (Fine et al., 2007) demonstrated efficacy after a single dose in protecting the immunized host against virulent challenge with subtype IA/B VEEV as well as other closely related VEEV subtypes (Hart et al., 2001). However, evaluation of the V3526 vaccine in Phase 1 clinical studies (Holley et al., 2008) resulted in adverse events in a number of vaccine recipients that stopped further development of the vaccine as a live attenuated vaccine product. Because live attenuated vaccines for VEEV have shown high frequency of adverse reactions (Kinney 1972; Edelman et al., 1979; Martin et al., 2009), DVC sought to produce a non-infectious V3526 vaccine, the intent of which was to significantly reduce the adverse reaction profile of V3526, while retaining its potential as a protective immunogen against subtype I VEEV. Of particular interest was to proceed with the development of an inactivated V3526 that ultimately could be used as a primary vaccine to protect personnel at risk to accidental or intentional VEEV exposure.

Physical, chemical and radiation methods have been used to inactivate infectious agents (Murdin et al., 1996; Jordan et al., 1955). In particular, gamma radiation has been advocated as a means of obtaining a sterile, biologically active biotechnology products and the use of ionizing radiation has been explored in the production of noninfective antigens for vaccines (Eisenberg and Osterman, 1979; Datta et al., 2006 ). Several vaccines prepared against encephalitis viruses have employed either formalin (Maire et al., 1970; Bartelloni et al., 1971; Cole et al., 1974) or gamma irradiation (Reitman et al., 1970; Gruber, 1971).

As an approach to developing one or more inactivated VEEV vaccines, a multisystem approach was used that allowed rapid screening of inactivated V3526 formulations for residual infectivity, neurovirulence and retention of virus envelope epitope binding. As a result, several safe and immunogenic vaccine formulations were developed for follow-on nonclinical studies.

2.0 Experimental/Materials and Methods

2.1 Manufacture of V3526

Process development for the small and large scale manufacture of V3526 was conducted at SAFC Pharma, Carlsbad, CA.

2.1.1 Production of V3526 Bulk Drug Substance Equivalent (BDSE) and Process Control Material (PCM)

BDS was produced by infecting multiple semi-confluent monolayers of human MRC-5 cells (multiplicity of infection (MOI) = 0.005/cell) grown in 10-layer Nunc Cell Factories (NCF) (Nunc, Inc.) with aliquots of a V3526 working virus bank. Prior to infection V3526 was diluted in phenol red- free Dulbecco’s Minimal Essential Medium (DMEM) containing 0.5% human serum albumin (HSA) (Grifols), 4 mM L- glutamate and 1 X non-essential amino acids (NEAA). The diluted virus inoculum was then added to each NCF and the cultures were incubated at 37°C for approximately 60 hr. At harvest, supernatant fluids from all NCF were pooled prior to clarification over a 0.8 µm filter, followed by concentration through a hollow fiber tangential flow filter (TFF) (GE Healthcare) with a 500 kDa molecular weight cutoff membrane. The concentrated bulk was diafiltered with 16 volumes of diafiltration buffer, consisting of phenol red-free DMEM supplemented with 0.5% v/v HSA. The diafiltered material was then filtered over a 0.2 µm membrane and stored at −80°C. Infectivity titer of the BDSE was determined by plaque assay on Vero cell monolayers. The final concentration of the material was approximately 23-fold. PCM was produced by essentially the same procedure described above with the exception that MRC-5 cells were mock-infected with phosphate buffered saline (PBS).

2.2 Preparation and Passage History and of TrD Challenge Virus

Working virus seed (WVS)(Lot # L019-06-005 6/8/06) of VEEV IA/B TrD strain was produced and qualified at Commonwealth Biotechnologies Incorporated, Richmond, VA for use in nonclinical challenges studies and as the challenge agent in potency testing for V3526.

Lineage of the TrD WVS from TrD historical stock was as follows. The TrD historical stock (Lot #GP1/E14) was produced in guinea pig brains in 1971 by the Salk Institute Government Services Division, Swiftwater, PA. To provide a virus stock not containing extraneous materials, both a new pre-master (Lot #GP1/E14, Vero Cells p130) and master virus seed (Lot # L019-06-0004) were produced in Vero cells at Southern Research Institute-Frederick in 2002. The master seed was subsequently used to produce the WVS at Commonwealth Biotechnologies Incorporated.

2.3 V3526 Inactivation

V3526 inactivation studies using heat or formalin were conducted at SAFC Pharma. V3526 inactivation using gamma irradiation was carried out at Sterigenics, Corona, CA. All inactivation studies used material from V3526 BDSE lots manufactured at SAFC’s Carlsbad Process Development Lab. For each inactivation study, a portion of BDSE was thawed and using DMEM containing 0.5% v/v HSA as diluent, three V3526 concentrations (3 × 107 pfu/mL, 3×106 pfu/mL and 3×105 pfu/mL) were formulated. For some studies only the highest concentration (3 × 107 pfu/mL) was tested.

2.3.1 Heat Inactivation

Aliquots of V3526 concentrations were placed into calibrated water baths. At defined intervals, samples from each concentration were removed and aliquoted into polypropylene tubes at 0.5 mL/tube and immediately frozen. The resulting samples were thawed and tested for residual infectivity by virus plaque assay.

2.3.2 Formalin Treatment

V3526 suspensions were treated with varied formalin (USP grade, EMD Chemicals) concentrations then placed into a calibrated shaking water bath set at 37°C. Samples were removed at defined time intervals and aliquoted into polypropylene tubes at 0.5 mL/tube and immediately frozen. Samples were thawed and tested for residual infectivity by virus plaque assay.

2.3.2.1 Residual Formalin Removal

In that residual formalin in a treated sample might interfere with virus plaque assay, an initial study was conducted to examine the feasibility of using dialysis cassettes following virus inactivation to reduce the levels of formalin prior to testing. V3526 samples at 2.9 × 107 pfu/mL were prepared. One sample was formulated to 0.05% v/v formalin and dialyzed immediately; a second sample was also formulated to 0.05% formalin, but was incubated for 15 min at 37°C in a calibrated water bath prior to dialysis. A third sample contained no formalin but was dialyzed following the same procedure as the other two samples. Samples tested by plaque assay showed no significant differences in plaque numbers between the positive control and samples tested with formalin, providing assurance that the dialysis procedure successfully reduced the levels of formalin below the level which would have interfered with the assay.

2.3.2.2 Small Scale Dialysis

At small scale dialysis, cassettes (Slide-A-Lyzer, 10kDa molecular weight cutoff [MWCO], Thermo Scientific) were used to reduce the levels of formalin in the treated virus preparations prior to infectivity testing. The dialysis procedure consisted of loading 3 mL of each sample into the cassettes then placing the cassettes in beakers containing approximately 1 L of diafiltration buffer, DMEM with 0.5% v/v HSA. The beakers were placed on stir plates set at low agitation. After one hour, the diafiltration buffer was discarded and fresh buffer added. Buffer exchange was repeated twice more, after an additional hr and after an overnight period. All diafiltration steps were done at ambient temperature. Samples were then tested by plaque assay. Dialysis volumes were chosen specifically for each starting formalin concentration in order to theoretically bring the final formalin concentration following dialysis to less than 1 × 10−8 %.

2.3.2.3 Large Scale Dialysis

Residual formalin was removed from larger volumes of treated V3526 using a TFF Cartridge (GE Healthcare). Volumes of 300 mL-500 mL of previously produced BDSE were formulated to a final formalin concentration of 0.1% and incubated at 37°C for 24 hr. The inactivated virus material was then transferred to a TFF system (GE Healthcare) with a 500 kDa MWCO membrane. During diafiltration the system volume is maintained with diafiltration buffer (0.5% v/v HSA in DMEM) in the TFF reservoir. The diafiltered material was collected and frozen at −80°C.

2.3.3 Gamma Irradiation

All gamma irradiation exposures were carried out at Sterigenics, Corona, CA. Samples to be irradiated were prepared at SAFC Pharma and shipped frozen following standard procedures for shipping of infectious materials. As a preliminary test, a dry-ice sublimation study was conducted to determine the quantity and configuration of packaging that would provide sufficient refrigeration of the infectious material when shipped to the irradiation site and back.

2.3.3.1 Dose Mapping

Prior to irradiation of V3526 BDSE, a dose mapping study was conducted to determine the actual dosing levels that the product would receive in the standard shipping configuration. At SAFC Pharma conical tubes (50 mL) were each filled with 15 mL of 0.5% v/v HSA, and placed into the standard material shipper. The package was sent to Sterigenics where dosimeters were placed throughout the packaging and dry ice proxy material added. The package was then placed into the irradiation chamber for a set exposure period. Following irradiation, the dosimeters were tested to determine the amounts of radiation seen throughout the packaging during the exposure period. Dose mapping studies were conducted for gamma irradiation exposures both on and off carrier. “Off carrier” refers to irradiation runs conducted with the container in a static position as compared to “on carrier” irradiation runs in which the container was placed on a moving track and transported through the irradiation chamber. Exposure times for subsequent runs were calculated from these data.

2.3.3.2 Gamma Irradiation of V3526

For each of the irradiation experiments 50 mL conical tubes containing 15 mL of three V3526 concentrations were used (one tube per concentration), along with two tubes of 0.5% v/v HAS supplemented with DMEM containing no virus. Irradiation runs were performed at theoretical dosages ranging from 410 Gray (Gy) to 50 kilo Gray (kGy). Initially, irradiation runs were conducted in a static position off-carrier and with a radiation shield in place. Subsequently, irradiation runs were conducted on-carrier. For all runs, dosimeters were in place to ensure that the calculated dosage was achieved.

2.4 Assays

2.4.1 Infectivity Assay

Samples were tested and quantitated for infectivity by a standard plaque assay previously described (Fine et al., 2007). Vero cells were initially selected for VEEV quantitation since plaque morphology tends to be more uniform and easier to enumerate. Infectivity titers (i.e. pfu/mL) were equivalent when assays are conducted on Vero versus BHK-21 cells. In brief, Vero cells are seeded in 6 well tissue culture plates and expanded to confluence. Cells are infected with serial dilutions of test samples as well as positive and negative controls, and then overlaid with agarose to prevent virus migration. Approximately 44±6 hrs later, a second overlay was applied that contained Neutral Red and the following day plaque counts were performed. Limit of detection in the Vero cell plaque assay is 3 pfu/mL.

2.4.2 Determination of Residual In Vitro Infectivity

Blind passage on Vero Cells – determination of residual infectivity of heat, formalin and gamma inactivated V3526 preparation was initially confirmed at SAFC via inoculation of 0.5 mL fluid onto 6-well plates of Vero cells. Plates were incubated for one hour at 37°C with occasional rocking. Following this incubation, 2.5 mL complete media (DMEM plus 10% v/v HSA) was added and cells were incubated at 37°C for 14 days. Following this incubation, cells were examined for cytopathic effect (CPE) and an aliquot (0.5 mL) of the supernatant was used to inoculate a fresh 6-well plate of Vero cells and incubated at 37°C for an additional 14 days and examined for CPE.

Blind passage on BHK-21 Cells - at the United States Army Medical Research Institute of Infectious Disease (USAMRIID), inactivated virus preparations were tested for residual infectivity on BHK-21 cells, a more sensitive cell line routinely used for detecting infectious alphaviruses (Beaty et al., 1989). Aliquots of each test sample (50 µL) plus 50 µL DMEM were used to inoculate a 6-well plate of BHK-21 cells for 1 hour at 37°C with occasional plate rocking. Following this incubation, 2.5 mL complete media (DMEM plus 10% v/v HSA) was added and cells were incubated at 37°C for 3–4 days. Following this incubation, cells were examined for CPE and an aliquot (50 µL) of the supernatant was used to inoculate a fresh 6-well monolayer of BHK-21 cells as described above. This process was repeated a total of 5 times. After each passage aliquots of the supernatant fluids were collected and frozen at −70°C for virus titration by plaque assay.

2.4.3 Testing for Residual Virulence

Although in vitro assessment of virus inactivation on BHK cell monolayers is a sensitive test, intracerebral (IC) inoculation of newborn mice was shown to have a greater degree of sensitivity for detection of latent neurotropic viruses (Heydrick et al., 1966). This procedure is routinely used for adventitious agent testing of biologic products and has been considered the “gold standard” for assessing inactivation/attenuation of VEEV (Sharma et al., 2007). Groups of suckling mice were inoculated IC with 10 µL of test virus. Other groups were IC inoculated with live V3526 and PCM that represent positive and negative controls, respectively for the assay. Brains of mice surviving 14 days post-inoculation were removed upon euthanasia, homogenized and frozen. A second set of suckling mice were inoculated IC with the brain homogenate from the corresponding group and observed for an additional 14 days. Nonclinical studies were conducted at USAMRIID and were in compliance with the Animal Welfare Act and other federal statutes and regulations relating to animals and experiments involving animals. USAMRIID is fully accredited by the Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care International.

2.4.4 Epitope Binding

A VEEV specific ELISA was used to measure V3526 envelope epitope determinants in the inactivated virus preparations. The assay was based on a standard sandwich ELISA method utilizing monoclonal antibodies (Mab 13D4, Mab 1A4A-1, or Mab 1A3A) for the capture of antigen and detection of antigen by horse anti-V3526 polyclonal serum. Mab 13D4 recognizes an E3 epitope of the PE2 protein of V3526 (Buckley and Hart, 1997), in comparison Mab 1A4A-1 and Mab 1A3A that recognize the E2c and E2g epitopes, respectively, on the VEEV IA/B E2 glycoprotein (Roehrig and Matthews, 1985). Consequently the use of Mab 1A4A-1or Mab 1A3A allows for detection of V3526, wild type virus (e.g., TrD), VEEV subtypes IC and ID, as well as C-84. Colorimetric determination of binding was facilitated through a peroxidase-labeled goat anti-horse antibody followed by the addition of ABTS substrate (KPL, Inc). Live V3526 served as the control antigen in the assay. The specificity of the assay was evaluated using Eastern equine encephalitis virus and Western equine encephalitis virus. Neither virus was detectable, confirming the specificity of the assay for strains of VEEV.

2.4.5 Quantitation of Inactivated V3526 Protein

The ELISA described above provided a basis for determining/confirming the amount of viral protein in a given preparation of inactivated V3526. Using a standard curve and linear regression analysis, calculations were performed to determine the amount of viral protein in V3526 BDS. Values were derived from standard curves using gradient purified V3526 with a known concentration of 869 µg/mL. The assay was performed using either of two monoclonal antibodies, Mab 1A4A and Mab 13D4. The calculated concentrations of V3526 control using Mab 1A4A or Mab 13D4 in the ELISA were 786.1 µg/mL and 842.9 µg/mL, respectively, both values close to the expected value of 869 µg/mL. The calculated concentrations of V3526 BDSE protein were 0.303 µg/mL and 0.309 µg/mL, respectively for Mab 1A4A and Mab 13D4 and the calculated concentrations of gV3526 were 0.261 µg/mL and 0.693 µg/mL, respectively for Mab 1A4A and Mab 13D4. Determination of V3526 protein for immunogenicity and protection studies was determined using Mab 1A4A in the quantitative ELISA.

2.5 Mouse Immunogenicity and Protection Testing

BALB/c mice, 8–10 weeks old, (National Cancer Institute, Frederick, MD.), were vaccinated via the subcutaneous (SC) route with formalin inactivated V3526 (fV3526), gamma irradiated V3526 (gV3526), or PCM on Days 0 and 28. C-84 (lot #7-run 1) was used as a comparator inactivated VEEV vaccine and was administered via the SC route at 4µg on Days 0, 7 and 28 consistent with route, dose and schedule used historically (Hart et al., 2002). For SC vaccination, 0.5 mL of inoculum was administered to the interscapular area. On Days 21 and 49 post-primary vaccination, blood was collected from all mice for immunological analysis. Mice were challenged on Day 56 with 1×104 pfu TrD by the SC route. Mice were monitored for 28 days post-challenge at which time surviving mice were euthanized.

Virus-neutralizing antibody (plaque reduction neutralization) in the immunized and control mice was determined as previously described (Fine et al., 2007) using TrD virus as target antigen. Sera were serially diluted two-fold with virus and incubated overnight at 4°C. The serum-virus mixtures were added to Vero cell monolayers for 1 hour, after which the plate wells were overlaid with 0.6% Eagle’s basal medium with Earle’s salts supplemented with 10% FBS, 200 U/mL penicillin, 200 µg/mL streptomycin, 100 mM L-glutamate and 100 µM NEAA. Plaques were developed with Neutral Red stain one day later. The endpoint titer was determined to be the highest dilution with an 80% or greater reduction of the number of plaques observed in control wells. Limit of quantitation for the PRN assay was at the initial 1:10 serum dilution (the most concentrated dilution tested) i.e., 1:20 dilution serum/virus mix. Plaque reduction neutralization titers were tested for statistical significance using analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Tukey’s post-hoc test.

3.0 Results

3.1 Heat Inactivation of V3526

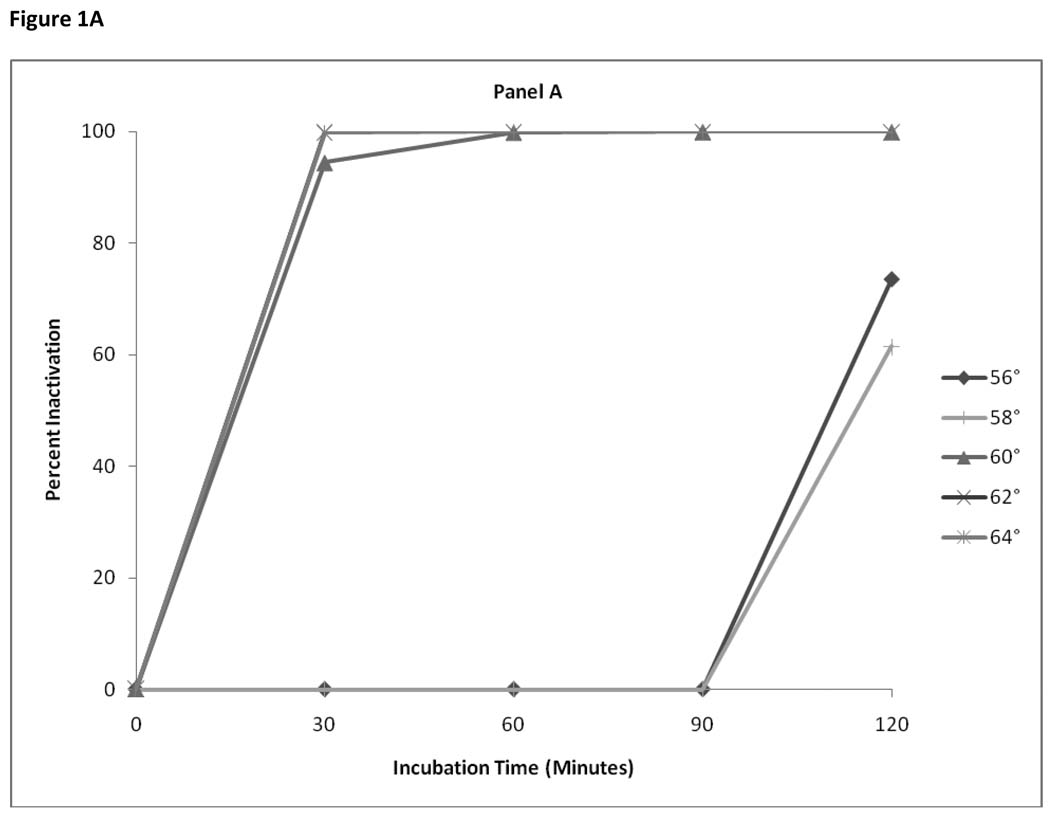

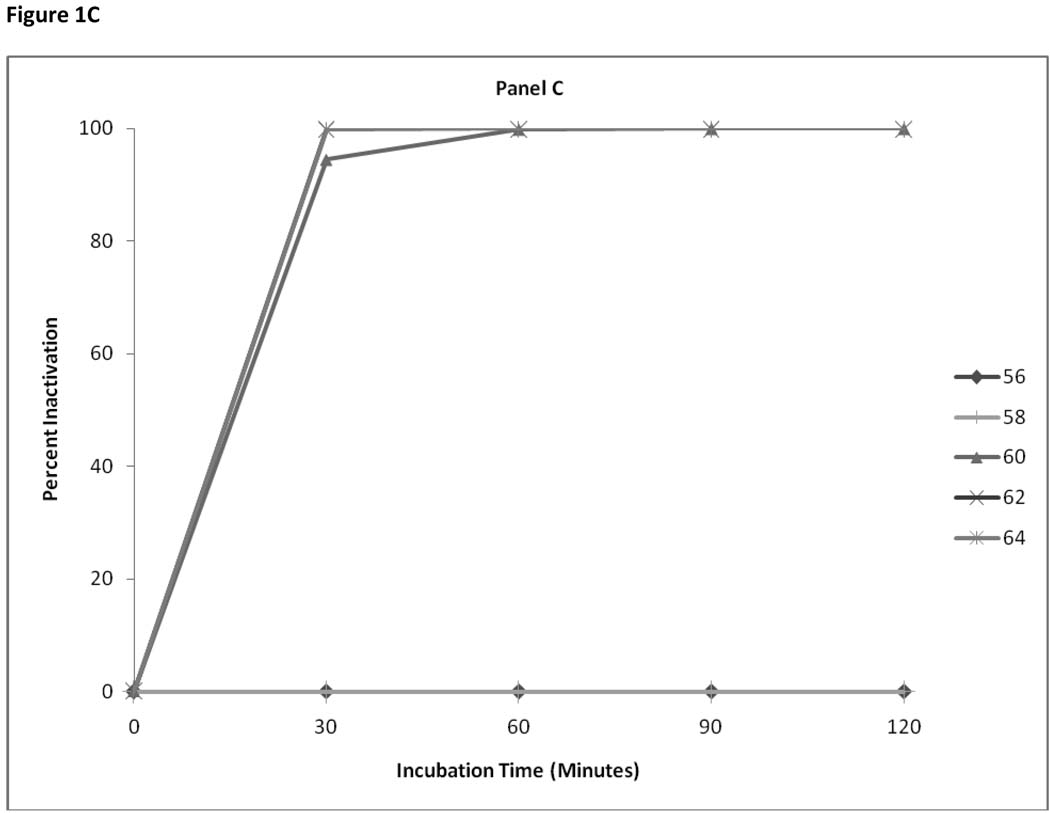

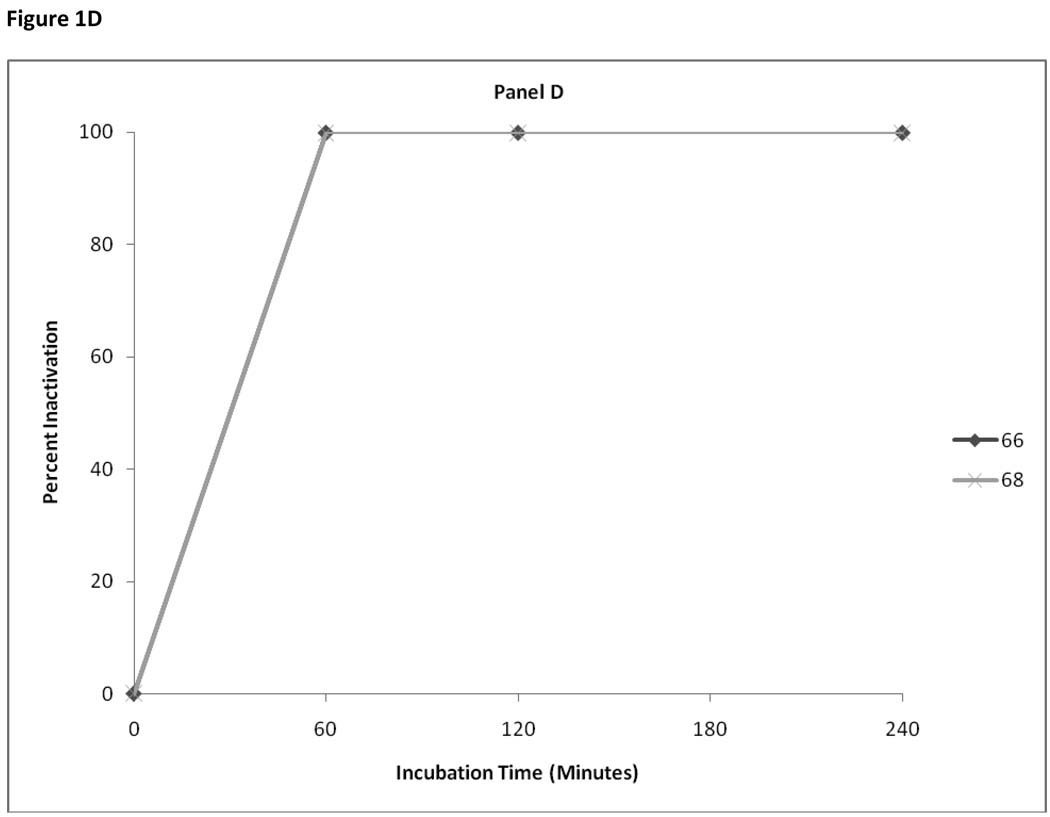

Three starting concentrations of V3526 (3 × 105, 3 × 106 and 3 × 107 pfu/mL) were incubated for intervals of 15 to 120 minutes at a range of temperatures from 56°C to 64°C. For the 3 × 105 pfu/mL starting concentrations complete virus inactivation was seen after 30 min at 64°C. Samples heated at 60°C and 62°C required a minimum of 60 minutes incubation for complete inactivation. Infectious virus was still detectable in samples heated at lower temperatures; 60°C, 62°C even after 120 minutes (Figure 1 – panel a). For starting concentrations of 3 ×106 pfu/ml, a minimum of 60 minutes of heating at temperatures of 60°C – 64°C was required for inactivation (Figure 1- panel b). For a starting concentration of 3 × 107 pfu/mL, minimum incubation time of 30 minutes at 64°C or 60 minutes at 60°C and 62°C was required for complete activation. At the higher concentration (3×107 pfu/ml) infectious virus was still detectable after 120 minutes at both 56°C and 58°C (Figure 1- panel c). To confirm the inactivation of higher concentrations of V3526 a subsequent experiment was performed in which 3 × 107 pfu/ml were heated at 66°C and 68°C for periods from 60 to 240 minutes. Figure 1- panel d confirms complete inactivation within 60 minutes at the higher temperatures. Loss of infectivity was documented by absence of viral CPE upon blind passage of the 66°C heated samples on Vero cell monolayers.

Figure 1. Panels A–D.

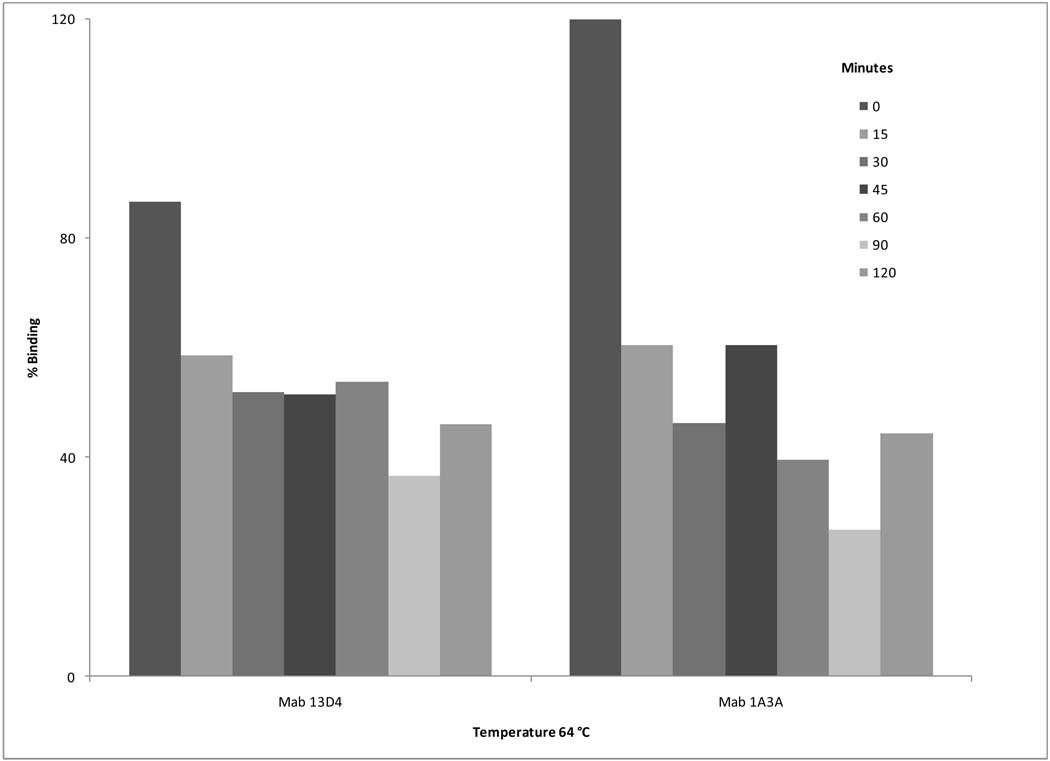

Aliquots of the 3 × 107 pfu/ml starting concentration that were heated at temperatures ranging from 58°C to 68°C were tested for residual binding in the ELISA (Figure 2) using MAb 1A4A. A high degree of binding (80% – 120%) was seen for samples heated as long as 90 min at 62°C and for samples heated up to 15 min at 64°C. (Levels of binding >100% of control may be attributed to the fact that sucrose purified V3526 served as control in the assay). However, a reduced level of binding activity occurred when V3526 was heated ≥ 30 min at 64°C. Continued heating at 64°C resulted in additional decrease in antibody binding. The 64°C heated V3526 samples were also testing for binding activity using Mab 13D4 and 1A3A. Prolonged heating at 64°C resulted in reduced levels of binding activity with these two monoclonal antibodies (Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Figure 3.

3.1.1 Evaluation of Formalin Doses at Small Scale

V3526 (3 × 107 pfu/ml) was incubated at concentrations of formalin ranging from 0.05% to 1.0% v/v for 1 hr at 37°C, followed by diafiltration, then tested for residual infectivity by plaque assay. The lowest formalin concentration (0.05%) resulted in a titer just above the detection limit of 3 pfu/mL, while all other formalin concentrations brought the infectivity titer below the limit of detection (Table 1). Samples treated with 0.1% were subsequently blind passaged on Vero cells for two 14 day cycles. No CPE was observed at either the end of either of the two successive fourteen-day blind passages.

Table 1.

Formalin Inactivation of V3526 at Small Scale

| Formalin % | pfu/ml |

|---|---|

| 0 | >2 × 104 |

| 0.05 | 3.3 × 100 |

| 0.10 | BLDa |

| 0.20 | BLD |

| 0.50 | BLD |

| 1.00 | BLD |

BLD – below limit of detection of the Vero cell assay (<3 pfu/mL)

3.1.2 Large Scale Formalin Inactivation

Using the chemical inactivation parameters described above that proved effective at small scale, a larger volume inactivation study was performed. Approximately 0.5 L of BDSE was formulated to a final formalin concentration of 0.1% and incubated at 37°C for 1 hr. The material was then dialyzed to reduce the formalin level. Unlike the material described in small scale inactivation, the volume of the BDSE material to be inactivated required the use of TFF rather than dialysis cassettes. Following diafiltration, the materials were tested by plaque assay and found to still contain active virus (data not shown). Two possibilities were theorized to explain this finding; that the 0.1% formalin concentration with 1 hr of incubation was the least rigorous condition that showed complete inactivation at the small scale and may need to be modified for large-scale inactivation or that the dialysis procedure used for small volumes provided a slow reduction of the formalin concentration over a period of more than 16 hr. In contrast, the dialysis provided by the TFF system generally takes no longer than 2 hr. As such, the use of dialysis cassettes might in effect create a longer incubation period in formalin than when using the TFF system, leading to higher levels of virus inactivation.

To more closely mimic the dialysis conditions that would be used for a large volume inactivation, that would be required for large scale manufacture of a formalin inactivated vaccine, four 15 mL aliquots of BDSE material were formulated with formalin; two aliquots to 0.1% formalin and two aliquots to 0.5% formalin. All four aliquots were placed in a shaking water bath at 37°C. After 4 hr of incubation, one of the 0.1% and one of the 0.5% formalin aliquots were removed and frozen. The two remaining aliquots were removed and frozen after 24 hr in the water bath. One mL aliquots of untreated BDS were also incubated for 4 and 24 hr and served as positive controls. The formalin treated aliquots were later thawed and each diafiltered over a 500K MWCO TFF cartridge, using similar parameters as would be used for a large volume process. As shown in Table 2, V3526 treated with 0.1% formalin for 4 hr was sufficient to provide full inactivation at the larger scale using a TFF dialysis system.

Table 2.

Formalin Inactivation of V3526

| Sample Designation |

Formalin Concentration |

Hours at 37°C |

Vero cell pfu/mL |

BHK-21 Cell Passagea |

Binding (% of Control) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Starting material (untreated) |

0.0% | 0 | 2.6 × 107 | ND | 100 |

| Temperature control 4hr |

0.0% | 4 | 2.2 × 107 | 3.1 × 108 | 121 |

| Temperature control 24hr |

0.0% | 24 | 1.7 × 106 | 4.8 × 108 | 95 |

| Formalin inactivated |

0.1% | 4 | BLDb | BLD | 139 |

| Formalin inactivated |

0.1% | 24 | BLD | BLD | 117 |

| Formalin inactivated |

0.5% | 4 | BLD | BLD | 19 |

| Formalin inactivated |

0.5% | 24 | BLD | BLD | 17 |

Titer after 5 passages of supernatant fluid from BHK-21 cell monolayers

BLD – below limit of detection of the Vero cell assay (<3 pfu/mL)

3.1.3 Correlation of Formalin Inactivation with Binding Activity

Aliquots from each of the inactivation conditions were tested for residual binding in the VEEV specific ELISA. Data presented in Table 2 demonstrate retention of binding of the 1A4A-1 monoclonal antibody for all four conditions, with the samples treated with 0.1% formalin for either 4 hr or 24 hr showing higher binding activity than corresponding samples treated with 0.5% formalin for either 4 hr or 24 hr.

3.2 Gamma Inactivation of V3526

3.2.1 Evaluation of Gamma Radiation Dosages for V3526 Inactivation

A series of experiments were conducted in which aliquots of V3526 at 3 × 105, 3 ×106 and 3 × 107 pfu/mL were subjected to varying dosages of gamma radiation. Samples were tested for residual infectivity by plaque assay. A summary of results (Table 3) indicate that doses of gamma irradiation in excess of 50 kGy were required to abolish infectivity, even at the lowest V3526 concentration (3 × 105 pfu/mL) tested.

Table 3.

Evaluation of Gamma Radiation Dosages for V3526 Inactivation

| Targeted Irradiation Dosage (kGy) | Starting Virus Concentration (pfu/mL) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 2.9 × 105 | 2.9 × 106 | 2.9 × 107 | |

| 0.4 | > 2 × 104 | > 2 × 104 | > 2 × 104 |

| 3 | > 2 × 104 | > 3.4 × 105 | > 2 × 107 |

| 6 | > 2 × 103 | > 2 × 103 | 3.8 × 106 |

| 13.5 | 1.5 × 102 | 6.0 × 103 | 1.5 × 105 |

| 50 | BLDa | BLD | BLD |

BLD - below limit of detection (<3 plaque forming units (pfu)/mL)

3.2.2 Gamma Irradiation Reduces Residual Binding

Repeat experiments were performed in which aliquots of V3526 at 3 × 107 pfu/mL were irradiated at dosages ranging from 13.5 kGy to 50 kGY. Additional V3526 BDSE was concentrated approximately 10 fold to a titer of 3 × 108 pfu/mL by TFF and irradiated at 50kGy. Irradiated materials were thawed and tested for residual infectivity and for binding in the VEE specific ELISA. As indicated in Table 4, a dose of 50 kGy was required to inactivate V3526 at either 3 × 107 or 3 × 108 pfu/mL. In addition to assaying these materials for infectivity on Vero cells, V3526 inactivation was confirmed by five successive blind passages of supernatants on BHK cell monolayers. ELISA testing of irradiated V3526 aliquots showed a reduction in epitope binding activity (32–50%) that corresponded with loss of virus infectivity (virus inactivation).

Table 4.

Gamma Irradiation of V3526 – Loss of Infectivity and Residual Binding

| Gamma Irradiation (Targeted Dosage) |

Infectivitya of Starting Concentration (pfu/mL) |

Infectivitya Post Irradiation (pfu/mL) |

Epitope Binding (% of Controlb) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Untreated | 3 × 107 | 3 × 107 | 100 |

| 13.5 kGy | 3 × 107 | 1.5 × 105 | 105 |

| 30 kGy | 3 × 107 | 2.3 × 102 | 80 |

| 40 kGy | 3 × 107 | 3.3 × 100 | 58 |

| 50 kGy | 3 × 107 | BLD c | 32 |

| 50 kGy | 3 × 108 | BLD | 50 |

Plaque assay on Vero cell monolayers

Sucrose purified V3526 served as control for the ELISA

BLD = below limit of detection (< 3 pfu/mL)

3.3 Testing of Formalin and Gamma Irradiated Vaccine Candidates for Residual Infectious Virus

To confirm inactivation of both formalin inactivated V3526 (fV3526) and gamma irradiated V3526 (gV3526), 10 µL samples of test material were inoculated IC into 1–3 day old suckling mice. The mice were observed daily for signs of sickness and death. Any animals showing signs of stunted growth, encephalitis and tremors were euthanized and their brains collected by aspiration. The collected aspirate was then inoculated into a second litter of mice to document the presence of infectious virus. PCM and live V3526 served as negative and positive controls (respectively) in the assay. Results of two studies (Table 5) demonstrate that suckling mice inoculated with either fV3526 or gV3526 failed to exhibit any signs of disease and continued to thrive during the observation period. In both studies, 100% of the mice inoculated with live V3526 died within 96 hours after inoculation consistent with findings reported previously (Wang et al., 2007). Like fV3526- and gV3526- inoculated mice, sham inoculated mice that received PCM showed no signs of disease. Similarly, when homogenates of brains from gV3526, fV3526 or PCM-inoculated mice were subsequently inoculated into a second group of suckling mice, no signs of illness were detected. However, all mice inoculated with brain homogenate from mice inoculated with V3526 died within 96 hr post inoculation. These results confirmed that the two methods of inactivation (formalin treatment and gamma irradiation) were effective in abolishing infectivity of V3526.

Table 5.

Neurovirulence Testing of fV3526 and gV3526 Vaccines in Newborn Mice

| Test Article a,b | Study 1 (Survivors/Total) |

Passageb of Study 1 Brain Homogenates (Survivors/Total) |

Study 2 (Survivors/Total) |

Passageb of Study 2 Brain Homogenates (Survivors/Total) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| fV3526 | 10/10 | 13/13 | ND | ND |

| gV3526 | ND | ND | 13/13 | 10/10 |

| Process Control Material | 8/8 | 10/10 | 12/12 | 8/8 |

| Untreated V3526 | 0/14 | 0/8 | 0/13 | 0/14 |

Newborn mice (less than 72 hours post birth) were each inoculated IC with 10µL of test material.

Test animals were observed daily for 14 days post inoculation for cannibalization, death and clinical signs including anorexia, dehydration and inactivity.

Homogenates of brains prepared from fV3526, gV3526 or PCM were inoculated into a second group of suckling mice.

3.4 Immune Responses to fV3526 and gV3526

Preparations of the inactivated V3526 were tested for immunogenicity and vaccine efficacy against challenge with virulent VEE TrD. Ten to twelve week old BALB/c mice were inoculated SC with either fV3526 or gV3526 vaccine. All mice received a second inoculation at Day 28. Control mice received PCM by the same route, volumes and schedule. C-84 vaccine served as a comparator vaccine for the experiment. In contrast to the fV3526, gV3526 and PCM groups, the C-84 group mice received three inoculations of 0.5 mL SC, consistent with use of C-84 in previous studies (Hart et al., 2001). At Day 56, all mice were challenged by SC inoculation with 1 × 104 pfu/mL of TrD. Serum samples were collected one week prior to the Day 28 immunization and the Day 56 challenge for measurement of antibody responses. Mice immunized SC with fV3526 had PRN responses on Day 21 post-vaccination as indicated by seroconversion of all animals in group 1. By Day 49 post-vaccination, animals in groups 1 exhibited a geometric mean titer (GMT) of 1576 (Table 6). In contrast, only 3 of 10 mice inoculated with gV3526 (group 2) seroconverted by Day 21 after the initial inoculation. By Day 49 10 of 10 mice in this group seroconverted and had a GMT of 160. Nevertheless, all mice inoculated SC with either fV3526 or gV3526 (groups 1, 2) survived challenge with TrD. All mice immunized with C-84 seroconverted by Day 21 (after receiving 2 of 3 inoculations) and at Day 49, one week prior to challenge, this group demonstrated the highest GMT (3377), however, only a moderate level of protection (70%) after challenge. There was no detectable PRN antibody response in any of the PCM inoculated mice, and all mice in this group succumbed after challenge with TrD. Statistical analysis of the PRN data showed the PCM GMT was significantly different from fV3526, gV3526 and C-84 p= 0.002. fV3526 was significantly different from gV3526 p= 0.001 and gV3526 was significantly different from C-84 p= 0.001. The PRN GMT for fV3526 was not significantly different from C-84.

Table 6.

Immunogenicity and Efficacy of fV3526 and gV3526

| Group | Vaccinea | Dose (µg Viral Protein) |

Seroconversion at Day 21b |

Seroconversion at Day 49b |

GMT c Day 49 d |

Survivors/Challenged e |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | fV3526 | 0.2 | 10/10 | 10/10 | 1576 | 10/10 |

| 2 | gV3526 | 0.2 | 2/10 | 10/10 | 160 | 9/9 |

| 3 | C84 | 4 | 10/10 | 10/10 | 3377 | 7/10 |

| 4 | PCM | 0 | 0/5 | 0/5 | 10 | 0/5 |

SC – subcutaneous 0.5 mL

Number mice positive (PRN titer >20) /total

GMT – geometric mean titer

Sera with titers < 20 (limit of detection in the PRN assay) were assigned a value of 10 in order to calculate GMT for the group

Survival 28 days after challenge

4.0 Discussion

In developing inactivated viral vaccines from whole infectious virus, particularly for human use, the complete inactivation of residual infectivity is required (Murdin et al., 1996). Studies described here used three different approaches to render V3526 non-infectious; heat, chemical treatment with formalin and exposure to gamma radiation. Thermal inactivation of virus infectivity occurs as a result of denaturation of external virus protein coat which is required for virus attachment, as well as inactivation of viral nucleic acid that is required for virus infectivity (Ginosa, W. 1968). Virus inactivation via formalin treatment occurs by irreversibly cross-linking primary amino groups in proteins with other nearby nitrogen atoms in protein or nucleic acid through a -CH2- linkage. In contrast, gamma radiation reduces virus infectivity as a result of modifications (e.g. covalent bond disruption) primarily to the virus nucleic acid, which in a molecular sense is the single largest target of the virus, and to a lesser degree to protein groups which in the aggregate are smaller, albeit repeating, molecular targets (Ginosa, W. 1968).

As described, we were unsuccessful in establishing a set of conditions in which V3526 could be completely inactivated by heat without significant alteration of antibody binding activity. Confirmation of loss of binding activity in the heated samples was verified using two distinct monoclonal antibodies to the E2 protein and one monoclonal to the E3 protein of VEEV. In that we were interested in developing a robust process for preparation of inactivated V3526 that would be amenable to large scale GMP manufacture. In considering the difficulties of developing process control parameters for consistent manufacture of a killed albeit immunogenic product, further development of heat inactivation was discontinued.

In contrast, we were successful in the inactivation of V3526 with both formalin and gamma irradiation. Our findings are consistent with previously published studies (Reitman et al., 1970; Bartelloni et al., 1971; Gruber J., 1971); Cole et al., 1974) in which either formalin or gamma irradiation was used for the preparation of inactivated alphavirus vaccines. In each of those studies, virus inactivation was confirmed by absence of plaque formation on mouse L-cell fibroblasts and/or absence of infectivity via IC inoculation of suckling mice. Potency (i.e., immunogenicity) of the inactivated vaccine was determined via development of serum neutralizing or hemagglutinin inhibiting antibodies in inoculated hamsters (Reitman and Tribble, 1967), guinea pigs (Maire et al., 1970) or via TrD challenge of vaccinated CD-1 mice (Cole et al., 1974). In meeting the expected regulatory requirements for documentation supporting the safety of new vaccines (FDA Guidance for Industry), we developed and implemented a multisystem approach to confirming the inactivation of vaccines derived from infectious viruses. Those assays included absence of plaque formation on Vero cells, absence of cytopathology following five sequential blind passages on BHK-21 cells, and lack of infectivity in IC inoculated suckling mice. In addition, our approach to screening inactivated vaccine candidates included the use of a VEEV specific ELISA, as a measure of retention of specific antigenic determinants in the inactivated vaccine preparations, specifically those localized on the VEEV E2 envelope protein. Previous studies (Roehrig and Matthews, 1985) identified critical virus neutralization sites within the E2 envelope protein, including the E2c epitope.

While both formalin treatment and gamma irradiation completely inactivated V3526, substantially higher levels of ELISA antibody binding were observed for the fV3526 as compared to gV3526. These findings suggest that gamma irradiation altered the antibody binding epitopes of the E2 protein to a greater degree than did the formalin treatment. An alternate possibility is that the E3 or PE2 protein may have been altered such that the E2c epitope was sterically blocked. In vivo assessment of immunogenicity of the two inactivated vaccines showed that mice inoculated with fV3526 had a more robust serum neutralizing antibody response to VEEV, than did gV3526 vaccine immunized mice. However, high levels of protection to challenge were observed in mice immunized with either fV3526 or gV3526. As such, while the specificity of the ELISA for the E2c epitope may serve as a assay for predicting immunogenicity of inactivated vaccine candidates, it is not necessarily a predictor of efficacy of the vaccine. This would make sense if protection against VEEV challenge is dependent not only on induction of neutralizing antibodies, but also non-neutralizing antibodies (Hart et al., 2001) or other immune mechanisms that are induced by intact, albeit inactivated vaccines (Geeraedts et al., 2008; Bender et al., 2009). Nevertheless, the ELISA provides a useful assay for down-selection of inactivated vaccine formulations in advance of more time consuming and expensive nonclinical testing and use of experimental animals.

Regarding formalin inactivation it is interesting to note that higher binding activity was found in samples treated with 0.1% v/v formalin than in the control untreated V3526. This same observation was made when corresponding samples of the formalin inactivated V3526 were tested in the ELISA using Mab 13D4 which recognizes the VEEV E3 protein. This would suggest that 0.1% formalin treatment may result in slight conformational changes to the V3526 envelope proteins making those determinants more available for antibody binding. Conversely, increasing the concentration of formalin to 0.5% v/v appeared to significantly reduce the binding activity of the treated virus. As such, subsequent V3526 BDSE lots were inactivated with formalin 0.1% v/v for 24 hr duration.

fV3526 (like live-attenuated V3526) would appear to be superior to the predecessor formalin inactivated C-84 in that mice immunized with fV3526 were protected against SC challenge with TrD. In the experiments described here, fV3526 administered in a two dose regimen at 0.2 µg/dose protected 100% of the mice as compared to a three dose regimen with C-84 (at 4 µg/dose) that had a 70% survival to challenge despite a robust PRN immune response. This observation was substantiated in subsequent studies in which C-84 immunized mice also were found to have reduced resistance to aerosol challenge with VEEV (Martin et al., 2009) possibly attributed to loss of potency resulting from prolonged storage of the C-84 vaccine since its manufacture in 1981.

In terms of protective efficacy both fV3526 and gV3526 may represent candidates for a next generation inactivated VEEV vaccine. However, several factors are to be considered regarding future manufacture of either vaccine candidate in concert with the rigor of current Good Manufacturing Practices. In comparing the two methods for virus inactivation, gamma radiation is a more straight forward process in that BDSE does not have to be thawed prior to inactivation, thus reducing the possibility of product contamination during manufacturing. Formalin-inactivation requires the additional down-stream steps of formalin addition, incubation, followed by removal of residual formalin by diafiltration. These additional steps in the preparation of a formalin-inactivated vaccine would require additional in process testing as well as final product release testing. However, the manufacturing cost of a gamma irradiated vaccine would be expected to be higher as a result of requiring multiple facilities to prepare final drug product (i.e. GMP compliant vaccine manufacturer for preparing BDSE, a licensed radiation source for inactivation of the product and perhaps a third facility for formulation and fill). Additional cost and time would be also envisioned for manufacture of a gamma irradiated vaccine as having to move the product intermediates from site to site.

The inherent sensitivities of the BHK-21 cytopathology assay and IC suckling mouse neurovirulence assay that were used in developing both fV3526 and gV3526 vaccines provided both verification that the final vaccine preparations were free of residual infectious virus, thus providing a measure of relative safety for the inactivated V3526 preparations as compared to the parent live-attenuated V3526. This is particularly important in the development of vaccines using neurotropic viruses, as evidenced by recent clinical studies where healthy volunteers vaccinated with a single dose (25 pfu/mL or 125 pfu/mL) of live-attenuated V3526, experienced moderate to severe adverse events consistent with a “viral like syndrome” (Holley et al., 2008).

While the results presented here were confined to development of inactivated VEEV vaccines, the practicality of using multiple assays for assessment of infectivity, neurovirulence and epitope binding can be easily applied in the development of inactivated vaccines for other alphaviruses or vaccines for protection against other infectious viruses.

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, (1UC1AI062538-01) and the Joint Science and Technology Office- Chemical, Biological Defense (Plan1.1C0041_09_RD_B).

The views, opinions and/or findings contained herein are those of the authors and should not be construed as an official Department of the Army position, policy or decision unless so designated by other documentation.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Bartelloni PJ, McKinney RW, Calia FM, Ramsburg HH, Cole FE., Jr Inactivated Western equine encephalomyelitis vaccine propogated in chick-embryo cell culture. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 1971;20(1):146–149. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1971.20.146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beaty BJ, Calisher CH, Shope RE. Arboviruses. In: Schmidt NJ, Emmons RW, editors. Diagnostic procedures for viral, rickettsial and chlamydial infections. 6th ed. Washington. D.C: Am. Pub. Hlth. Assoc.; 1989. pp. 797–855. [Google Scholar]

- Bender A, Bui LK, Feldman MA, Larsson M, Bhardwaj N. Inactivated influenza virus, when presented on dendritic cells, elicits human CD8+ cytolytic T cell responses. J. Exp. Med. 2009;182(6):1663–1671. doi: 10.1084/jem.182.6.1663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckley M, Hart MK. Characterization of VEE virus E2-specific monoclonal antibodies [dissertation] Frederick, MD: Hood College; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Burke DS, Ramsburg HH, Edelman R. Persistence in humans of antibody to subtypes of Venezuelan equine encephalomyelitis (VEE) virus after immunization with attenuated (TC-83) VEE virus vaccine. J. Infect. Dis. 1977;136:354–359. doi: 10.1093/infdis/136.3.354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole FE, Jr, May WW, Eddy GA. Inactivated Venezuelan equine encephalomyelitis vaccine prepared from attenuated (TC-83 strain) virus. Appl. Microbiol. 1974;27:150–153. doi: 10.1128/am.27.1.150-153.1974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Datta SK, Okamoto S, Hayashi T, Shin SS, Mihajlov I, Fermin A, Guiney DG, Fierer J, Razl E. Vaccination with irradiated Listeria induced protective T cell immunity. Immunity. 2006;25:143–152. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Mucha-Macias J, Sanchez-Spindola I. Two human cases of laboratory infections with Mucambo virus. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 1965;14:475–478. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis N, Brown K, Greenwald G, Zajac A, Zacny V, Smith J, et al. Attenuated mutants of Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus containing lethal mutations in the PE2 cleavage signal combined with a second-site suppressor mutation in E1. Virology. 1995;183:102–110. doi: 10.1006/viro.1995.1458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dietz WJ, Peralta PH, Johnson K. Ten clinical cases of human infection with Venezuelan equine encephalomyelitis virus, subtype 1-D. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 1979;28:329–334. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1979.28.329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edelman R, Ascher MS, Oster CN, Ramsurg HH, Cole FE, Eddy GA. Evaluation in humans of a new, inactivated vaccine for Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus (C84) J. Infect. Dis. 1979;140:708–715. doi: 10.1093/infdis/140.5.708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg GH, Jr, Osterman JV. Gamma –irradiated scrub typhus immunogens: broad spectrum immunity with combinations of rickettsial strains. Infect. Immun. 1979;26:131–136. doi: 10.1128/iai.26.1.131-136.1979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FDA Guidance. Content and Format of Chemistry, Manufacturing and Controls Information and Establishment Description Information for a Vaccine or Related Product. U.S. Dept. Health and Human Services, Food and Drug Administration, Center for Biological Evaluation and Research; 1999. Jan, [Google Scholar]

- Fine DL, Roberts MA, Teehee ML, Terpening SJ, Kelly CLH, Raetz JJ, et al. Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus vaccine candidate (V3526) safety, immunogenicity and efficacy in horses. Vaccine. 2007;25:1868–1876. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2006.10.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fine DL, Roberts BA, Terpening SJ, Mott J, Vasconcelos D, House RV. Neurovirulence evaluation of Venezuelan equine encephalitis (VEE) vaccine candidate V3526 in nonhuman primates. Vaccine. 2008;26:3497–3508. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2008.04.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geeraedts F, Goutagny N, Hornung V, Severa M, de Hann A, Pool J, Wilschut J, Fitzgerald KA, Huckriede A. Superior immunogenicity of inactivated whole virus H5N1 influenza vaccine is primarily controlled by toll-like receptor signaling. Plos. Pathog. 2008;4(8):138–148. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Genoza W. Inactivation of viruses by ionizing radiation and by heat. In: Maramorosch K, Koprowski H, editors. Methods in Virology. vol. 4. New York: Academic Press Inc.; 1968. pp. 139–209. [Google Scholar]

- Gruber J. Immunogenicity of purified Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus inactivated by ionizing radiation. Infect. and Immun. 1971;3(4):574–579. doi: 10.1128/iai.3.4.574-579.1971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hart MK, Caswell-Stephan K, Baaken R, Tammariello R, Pratt W, Davis N, Johnston RE, Smith J, Steele K. Improved mucosal protection against Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus is induced by the molecularly defined, live-attenuated V3526 vaccine candidate. Vaccine. 2000;18:3067–3075. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(00)00042-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hart MK, Lind C, Bakken R, Robertson M, Tammariello R, Ludwig GM. Onset and duration of protective immunity to IA.B and IE strains of Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus in vaccinated mice. Vaccine. 2001;20(3):616–622. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(01)00337-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heydrick FP, Wachter RF, Hearn HJ., Jr Host influence on the characteristics of Venezuelan equine encephalomyelitis virus. J. Bacteriol. 1966;91:2343–2348. doi: 10.1128/jb.91.6.2343-2348.1966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holley HP, Fine DL, Terpening SJ, Mallory RM, Main CA, Snow DM, Helber S. Safety of an Attenuated Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus (VEEV) vaccine in humans. Presented at the 48th Annual ICAAC/IDSA 46th Annual Meeting; 2008 Oct 25; Washington, DC. 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Jahrling P, Stephensen EH. Protective efficacies of live attenuated and formaldehydeinactivated Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus vaccines against aerosol challenge in hamsters. J. Clin. Micro. 1984;19:429–431. doi: 10.1128/jcm.19.3.429-431.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jordan RT, Kempe LL. Inactivation of some animal viruses with gamma radiation from Cobalt 60. Proc. Soc. Exp. Biol. Med. 1955;91:212–215. doi: 10.3181/00379727-91-22215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maire LF, McKinney RW, Cole FE., Jr An inactivated eastern equine encephalomyelitis vaccine propogated in chick-embryo cell culture. I. Production and Testing. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 1970;19:119–122. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1970.19.119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin S, Bakken RR, Lind CM, Reed DS, Price JL, Koeller CA, Parker MD, Hart MK, Fine DL. Telemetric analysis to detect febrile responses in mice following vaccination with a liveattenuated virus vaccine. Vaccine. 2009;27:6814–6823. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2009.09.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin S, Parker M, Glass P, Bakken R, Lind C, Garcia P, Jenkins E, Hart MK, Fine D. Aerobiology in BioDefense III. Cumberland, MD: 2009. Jul 13–16, Evaluation of the Immunogenicity and Efficacy of Inactivated Venezuelan Equine Encephalitis Virus (VEEV) Vaccine Candidates in BALB/c Mice. [Google Scholar]

- McKinney RW, Berge TO, Sawyer WD, Tigertt WD, Crozier D. Use of an attenuated strain of Venezuelan equine encephalomyelitis virus for immunization in man. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 1963;12:597–603. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1963.12.597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKinney RW. Inactivated and live VEE vaccines – a review; Proceedings of the workshop symposium on Venezuelan Equine Encephalitis; Pan American Health Organization Scientific Publication; 1972. pp. 369–389. no. 243. [Google Scholar]

- Murdin A, Barreto L, Plotkin S. Inactivated poliovirus vaccine: past and present experience. Vaccine. 1996;14(8):735–746. doi: 10.1016/0264-410x(95)00211-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pratt W, Davis N, Johnston R, Smith J. Genetically engineered, live attenuated vaccines for Venezuelan equine encephalitis: testing in animal models. Vaccine. 2003;21:3584–3562. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(03)00328-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reitman M, Tribble HR, Jr, Green L. Gamma-irradiated Venezuelan equine encephalitis vaccines. Appl. Microbiol. 1970;19(5):763–767. doi: 10.1128/am.19.5.763-767.1970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roehrig JT, Matthews JH. The neutralization site on the E2 glycoprotein of Venezuelan equine encephalomyelitis (TC-83) virus is composed of multiple conformationally stable epitopes. Virology. 1985;142:347–356. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(85)90343-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma AY, Raviv A, Puri M, Viard R, Blumenthal R, Maheshwari RK. Complete inactivation of Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus by iodonaphthylazide. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Comm. 2007;358:392–398. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.04.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith JF, Davis K, Hart MK, Ludwig GM, McClain DJ, Parker MD, et al. Chapter 28. In: Sidwell RV, Takafuji ET, Franz DR, editors. Medical aspects of chemical and biological warfare. 1997. pp. 561–589. [Google Scholar]

- Wang E, Petrakova O, Paige Adams A, Aquilar PV, Kang W, Paessler S, Volk SM, Frolov I, Weaver SC. Chimeric sindbis/eastern equine encephalitis vaccine candidates are highly attenuated and immunogenic in mice. Vaccine. 2007;25(43):7573–7581. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2007.07.061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weaver SC, Ferro C, Barriera R, Boshell J, Navarro J. Venezuelan equine enchephalitis. Ann. Rev. Entomol. 2004;49:141–174. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ento.49.061802.123422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]