Abstract

We used exploratory factor analysis within the confirmatory analysis framework, and data provided by family members and friends of 205 decedents in Missoula, Montana, to construct a model of latent variable domains underlying the Quality of Dying and Death (QODD) questionnaire. We then used data from 182 surrogate respondents, representing Seattle decedents, to verify the latent variable structure. Results from the two samples suggested that survivors’ retrospective ratings of 13 specific aspects of decedents’ end-of-life experience served as indicators of four correlated, but distinct, latent variable domains: symptom control, preparation, connectedness, and transcendence. A model testing a unidimensional domain structure exhibited unsatisfactory fit to the data, implying that a single global quality measure of dying and death may provide insufficient evidence for guiding clinical practice, evaluating interventions to improve quality of care, or assessing the status or trajectory of individual patients. In anticipation of possible future research tying the quality of dying and death to theoretical constructs, we linked the inferred domains to concepts from Identity Theory and Existential Psychology. We conclude that research based on the current version of the QODD questionnaire might benefit from use of composite measures representing the four identified domains, but that future expansion and modification of the QODD are in order.

Keywords: Quality of life, quality of death, quality of dying, good death, bad death, end of life, palliative care, confirmatory factor analysis, latent variable domains

Introduction

Although people assign high priority to freedom from pain during the end-of-life period (1,2), there is general agreement that the quality of dying and death is defined by more than control of physical distress and that interventions designed to improve the circumstances of the dying must attend to multiple dimensions of experience. Researchers have proposed a number of schemas in their efforts to define and operationalize these dimensions (3-22). Some have been based on qualitative research (4-7, 9-11, 13-16, 18); some have focused on development of survey instruments (3, 4, 11-14, 22); and some have been quantitative studies that tested pre-existing hypotheses (10, 12, 13) or involved exploratory identification of domain structures (17, 22).

However, two recent state-of-the-science articles on end-of-life research noted the absence of theoretical foundation in the literature (23,24). The authors concluded that the incorporation of theory into conceptual designs, with subsequent testing of theory-based hypotheses, is essential to advancement of the field and to a better understanding of the end-of-life experience. Several potentially useful theoretical traditions exist for considering and evaluating the dying-and-death experience - among them, Symbolic Interactionism (including its theoretical expression in Identity Theory) (25-35) and Existential Psychology (36).

A few writers on end-of-life issues have noted the relevance of Symbolic Interactionism and the concept of a socially-constructed “dying role” (20,37-39). Translated into the language of Identity Theory, the “dying person” identity exists as one of an individual’s multiple identities. Over the course of the end-of-life period the salience of this identity increases, requiring abandonment or dramatic alteration of other identities as failing physical or mental function renders them progressively more difficult to maintain. Such changes require continual reintegration of the self-concept (21). Identity Theorists have suggested that although the self-concept is particularly vulnerable during role transitions (28), individuals also exert considerable personal agency, protecting established self-views from change (29). Existential Psychology similarly describes themes related to identity, emphasizing the need to view oneself as autonomous and responsible, to deepen connections with others who share important parts of one’s worldview, to experience growth and self-actualization, and - importantly - to establish a sense of transcendent identity (i.e., an understanding that one’s life has meaning that will continue after death). A recent article on “moment of death” dramas bridges these two traditions, noting the need for theories of identity to take into account the dying person’s posthumous social presence in the lives of those left behind, and the impact of this dynamic on role performances near the end of life (40).

These traditions suggest approaches to conceptualizing the “good death” and may assist in interpreting patterns arising in empirical data. It is within this context that we examine the domain structure underlying the Quality of Dying and Death (QODD) questionnaire. Previous analysis of a 31-item version of the QODD, administered to surviving family and friends of decedents from Missoula, Montana, provided initial validation of the instrument (41). The validation exercise focused on establishing (a) that the component items had acceptable measurement properties, and (b) that a scale comprising the 31 items had good internal consistency and appropriate construct validity. This suggested the possibility of a single composite QODD measure, computed as an average of the 31 items. The authors deferred consideration of a multi-domain structure until additional data could be collected.

Our recent work has focused on identifying and verifying a domain (or factor) structure underlying the QODD. As part of this effort, we identified a reduced set of 17 items that represented high or moderately high priorities for many terminally ill persons and their intimate associates (2). In the current article we report results of the following additional analyses: examination of whether the 31 QODD items represent a unidimensional construct; test of a six-domain structure initially hypothesized by the instrument’s authors; and identification and verification of an alternative domain structure, drawing from the reduced pool of 17 end-of-life priorities. We then investigate the correlation of the identified domains with global ratings of quality of life and quality of death and interpret the structure in light of theoretical concepts.

Methods

Study Samples

Data for the study came from interviews with intimate associates of three samples of decedents: (a) 205 who died in Missoula, Montana, between January 1996 and December 1997 (the “Missoula sample”); (b) 74 Seattle-area hospice patients who died between December 1998 and March 2003, and who participated before their deaths in a study of quality of dying in hospice (the “hospice sample”); and (c) 108 Seattle-area patients who died between September 2004 and August 2007, and who participated before their deaths in a clinical trial of complementary and alternative medical techniques (the “clinical trial sample”). Almost all respondents were family members or close friends of the decedents; a few (9%) in the clinical trial sample were healthcare professionals involved in the care of socially isolated patients. Detailed descriptions of the samples have appeared elsewhere (41-43). All participants signed informed consent, and review boards of the sponsoring organizations approved all study protocols.

For our analyses the Missoula sample served as the primary group for testing hypotheses regarding domain structures and identifying an alternative structure with better fit. Because neither the hospice sample nor the clinical trial sample was large enough to serve independently as a confirmation sample, we combined them into a single “Seattle sample” to confirm the revised model.

Measures

The indicators for domains underlying the dying-and-death experience came from a QODD interview, in which respondents evaluated the quality of 31 characteristics of decedents’ end-of-life experience. For each of the 31 characteristics, they provided details about the characteristic (e.g., whether or how frequently an event occurred) and then evaluated what had occurred, using a scale ranging from 0 (“terrible experience”) to 10 (“almost perfect experience”). These 0-to-10 ratings were the raw data for our analyses. We based our tests of two hypotheses (the single-factor and six-factor structure) on the original 31-item version of the QODD (Table 1) (44). However, in an earlier article (2) we identified 17 characteristics that many people rate as high or moderately high end-of-life priorities, and we based development of an alternative model of QODD domain structure on these 17 items (Table 2).

Table 1. Six Hypothesized Domains of the Quality of Dying and Death.

| Symptoms and Personal Control |

| Pain under controla |

| Control over what was going ona |

| Ability to feed him/herselfa |

| Control of bladder and bowelsa |

| Breathing comforta |

| Sufficient energya |

| Preparation for Death |

| At peace with dyinga |

| Unafraid of dyinga |

| Untroubled about strain on loved onesa |

| Healthcare costs coveredb |

| Spiritual advisor visitsb |

| Spiritual ceremony before deathb |

| Funeral arrangements in orderc |

| Goodbyes saidb |

| Attendance at important eventsb |

| Bad feelings cleared upb |

| Moment of Death |

| Place of death |

| Having others present at time of death |

| State of consciousness in moment before death |

| Family |

| Time with spouse/partnera |

| Time with childrena |

| Time with other family/friendsa |

| Time alonea |

| Time with petsa |

| Treatment Preferences |

| End-of-life care discussions with doctorc |

| Means to hasten death, if neededb |

| Use or avoidance of life supportb |

| Whole Person Concerns |

| Ability to laugh and smilea |

| Physical expressions of affectionb |

| Meaning and purpose in lifeb |

| Maintained dignity and self-respecta |

The reference period for this item was “during the last 7 days of life” (or, if the patient could not communicate during the last 7 days, the “last month of life”). The filter question asked how often the event occurred during the reference period.

The reference period for this item was the same as “a” (above), but the filter question asked whether the event occurred at all during the reference period.

The reference period was “by the time of death.” The filter question asked whether the event had occurred at any time before death.

Table 2. High- and Medium-Priority End-of-Life Characteristics.

| High Priority | Time with family and friendsa,b |

| Pain under controla | |

| Breathing comforta | |

| Maintained dignity and self-respecta | |

| At peace with dyinga | |

| Physical expressions of affectionc | |

| Untroubled about strain on loved onesa | |

| Use or avoidance of life supportc | |

| Medium Priority | Goodbyes saidc |

| Control of bladder and bowelsa | |

| Unafraid of dyinga | |

| Ability to laugh and smilea | |

| Healthcare costs coveredc | |

| Control over what was going ona | |

| Means to hasten death, if neededc | |

| Spiritual advisor visitsc | |

| Funeral arrangements in orderd |

The reference period for this item was “during the last 7 days of life” (or, if the patient could not communicate during the last 7 days, the “last month of life”). The filter question asked how often the event occurred during the reference period.

Time with family and friends was a composite measure, computed as the minimum rating for three items: time with spouse/partner, time with children, time with other family and friends.

The reference period for this item was the same as “a” (above), but the filter question asked whether the event occurred at all during the reference period.

The reference period was “by the time of death.” The filter question asked whether the event had occurred at any time before death.

Respondents also provided two global ratings, using the same 11-point rating scale: the overall quality of the final period of life (one week for decedents who could communicate during the final week; one month for other decedents), and the quality of the moment of death. We used these ratings to examine correlations between the quality of specific end-of-life domains and the overall quality of the dying and death experience.

Because all ratings showed significant departure from the normal distribution, based on Kolmogorov-Smirnov and Shapiro-Wilk tests, we modeled these outcomes as ordered categorical variables. All variables with significant skew were skewed in the negative direction (i.e., responses tending positive). In view of the direction of skew and software limitations restricting to 10 the number of categories allowed for ordinal outcomes, we recoded values of 0 to 1, thus converting all outcomes to a 1-10 scale.

The three datasets had several additional variables in common, which we used in descriptive summaries and to test for between-sample differences. These included gender, age, racial/ethnic minority status, and education levels of decedents and respondents, length of association between decedents and respondents, decedents’ life-limiting diagnosis and place of death, communication status of decedents during the last week of life, time between death and respondents’ interviews, and whether the decedent was enrolled in a hospice program.

Analysis Methods

We performed confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) on data from the Missoula sample to test two hypothesized latent-variable measurement models: (a) a model in which all QODD indicators were outcomes of a single underlying factor (41), and (b) the six-factor conceptual model hypothesized by the QODD developers (11). Two of the original 31 ratings involved large amounts of missing data: attendance at important events and clearing up bad feelings with others (ratings impossible when no important events had occurred or when no relationships needed resolution). By eliminating these two items from the indicator pool, and basing the two hypothesis tests on 29 items, we attained 22% or higher coverage on all indicator pairs in the covariance matrix (mean coverage = 0.776).

After completing the two CFA-based hypothesis tests, we used exploratory factor analysis within the confirmatory factor analysis framework (E/CFA) (45) to develop an alternative measurement model from the reduced pool of 17 high- and medium-priority items. Our goal was to develop a model that included all eight of the items constituting the high-priority group, and as many of the nine items constituting the medium-priority group as possible, while maintaining good fit. We used Lagrange multipliers (LMs) to guide splitting/combining domains and moving indicators from one domain to another, while requiring that the resulting domains retain conceptual integrity. Where LMs showed evidence of correlated residuals, we pulled indicator sets out of the originally posited domains into separate domains. Where there was evidence that an indicator loaded strongly on a different but equally plausible factor, we shifted the indicator to the new factor - sometimes requiring the collapse of two related domains into a single factor. Where LMs suggested strong cross-loading of an indicator on multiple domains, we removed the indicator from the model entirely. After finding a model with adequate fit to the Missoula sample, we used the merged Seattle samples to verify the result. Finally, we computed correlations between latent variables in the confirmed model and respondents’ overall ratings of the quality of life and quality of death.

We used Mplus software (46) for all CFA and E/CFA models and based parameter estimates and significance tests on a weighted least squares mean- and variance-adjusted (WLSMV) estimator for ordered categorical outcomes. The analyses used full-information missing data processing (each respondent appearing in all covariances for which there were data on the variable pair). We evaluated the fit of each model against the following criteria: probability associated with the χ2 test for departure from fit >0.05; Bentler’s Comparative Fit Index (CFI) ≥0.96; Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI) ≥0.95; Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) ≤0.05 (47).

Results

Sample Characteristics

Table 3 summarizes the sample characteristics. Just over half of all decedents and almost three-fourths of the respondents were female. Almost all represented the racial-ethnic majority group. Decedents ranged from 19 to 102 years at death, and respondents from 17 to 90 years at the time of interview. Length of association between respondents and decedents ranged from less than one year to over 81 years. More than half of decedents and respondents had some college education. Slightly more than half of the decedents were cancer patients; over half had received hospice care during the last year of life; and they had died in a variety of settings, including private homes, nursing homes, hospitals, and inpatient hospice centers. Elapsed time between death and the respondent’s interview ranged from eight days to 2.8 years. Among respondents who provided single-item ratings of both the overall quality of the end-of-life period and the quality of the moment of death, ratings were significantly higher for the moment of death than for the end-of-life period as a whole (median values of 9 and 5, respectively; P<0.001).

Table 3. Sample Characteristics.

| Missoula | Hospice | Clinical Trial | Total | Pa | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample Size | 205 | 74 | 108 | 387 | |

| % Female | |||||

| Decedent | 50.2 | 56.8 | 61.1 | 54.5 | 0.082 |

| Survivor | 74.1 | 67.6 | 72.2 | 72.4 | 0.427 |

| % Racial/Ethnic Minority | |||||

| Decedentb | 4.4 | 4.1 | 8.3 | 5.4 | 0.376 |

| Survivorb | 2.9 | 5.4 | 6.5 | 4.4 | 0.213 |

| Median Age | |||||

| Decedent (at death) | 79.7 | 74.4 | 75.3 | 77.6 | 0.004 |

| Survivor (at interview) c | 56.0 | 55.7 | 52.8 | 55.1 | 0.371 |

| Median Education Categoryd | |||||

| Decedent | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 0.000 |

| Survivor | 3 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 0.019 |

| Primary Diagnosis | 0.000 | ||||

| % Cancer | 32.2 | 75.7 | 71.3 | 51.4 | |

| % Cardiovascular Disease | 26.8 | 5.4 | 13.9 | 19.1 | |

| % Pulmonary Disease (Non-Cancer) | 9.3 | 5.4 | 5.6 | 7.5 | |

| % Neurologic Disease | 13.2 | 4.1 | 5.6 | 9.3 | |

| % Other Condition | 18.5 | 9.5 | 3.7 | 12.7 | |

| % Who Could Communicate in Final Week | 80.0 | 71.6 | 76.9 | 77.5 | 0.225 |

| % Who Received Hospice Care | 23.9 | 100.0 | 90.7 | 57.1 | 0.000 |

| Place of Death | 0.000 | ||||

| % Private Home | 25.4 | 58.1 | 47.2 | 37.7 | |

| % Hospital | 33.2 | 5.4 | 12.0 | 22.0 | |

| % Inpatient Hospice | 8.8 | 21.6 | 16.7 | 13.4 | |

| % Nursing Facility | 31.2 | 14.9 | 24.1 | 26.1 | |

| % Other Location | 1.5 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.8 | |

| Median Years Survivor Knew Patiente | 48.0 | 45.5 | 40.7 | 46.0 | 0.003 |

| Elapsed Days from Death to Survivor Interview | 734.0 | 81.5 | 99.5 | 335.0 | 0.000 |

| Overall Quality of End-of-Life Periodf | 4 | 6 | 5 | 5 | 0.000 |

| Quality of Moment of Deathg | 9 | 10 | 9 | 9 | 0.002 |

Differences between the Missoula sample and the combined Seattle samples were based on Fisher’s Exact Test for dichotomous outcomes (gender, racial/ethnic minority status, receipt of hospice care), Pearson’s Chi-square tests for other non-ordinal outcomes (diagnosis, place of death), and Mann-Whitney Z-approximations for ordinal outcomes (age, education, length of association between decedent and survivor, time from death to interview).

Race-ethnicity for the Missoula sample was based on 204 cases.

Only 107 of the clinical trial survivors reported age.

Education codes: 1=less than high school diploma/GED; 2=high school diploma/GED; 3=some college; 4=4-year college degree or more. Education levels were reported for only 198 of the Missoula decedents.

Length of association was reported by only 184 of the Missoula survivors and 107 of the clinical trial survivors.

Ratings could range from 0 (terrible experience) to 10 (almost perfect experience). Valid responses were provided by 204 Missoula respondents, 70 hospice respondents, and 107 clinical trial respondents.

Ratings could range from 0 (terrible experience) to 10 (almost perfect experience). Valid responses were provided by 182 Missoula respondents, 63 hospice respondents, and 100 clinical trial respondents.

AU: PLS INDICATE WHAT BOLDED NUMBERS REPRESENT

Several characteristics significantly distinguished the Missoula sample from the combined Seattle samples: greater elapsed time between patient death and surrogate interview, older decedents, lengthier associations between respondents and decedents, more non-cancer diagnoses, less use of hospice care, more deaths occurring in hospital, lower education levels for both decedents and respondents, and lower ratings on the single-item measures of quality of life and quality of death. A total of 87 patients (22.4%) could not communicate during the final week of life; for these patients, the frame of reference for questions regarding the final end-of-life period was the last month of life; for all others, the frame of reference was the last week of life.

Test for Unidimensionality of the QODD

After eliminating the two ratings with low coverage, we tested a 29-indicator single-factor model for the quality of dying and death. This model exhibited significant departure from fit when applied to the Missoula data (χ2 = 366.172, df = 77, P = 0.000; CFI = 0.776; TLI = 0.846; RMSEA = 0.135).

Test of Six-Domain Conceptual Model Hypothesized by QODD Developers

We then tested the fit of the six-domain conceptual model hypothesized by the QODD developers (Table 1), using the same 29 indicators as were used for the single-factor model. This model fit the data slightly better than the single-factor model, but still showed significant departure from fit (χ2 = 274.296, df = 79, P = 0.000; CFI = 0.848; TLI = 0.898; RMSEA = 0.110).

Identification and Verification of an Alternative Measurement Model

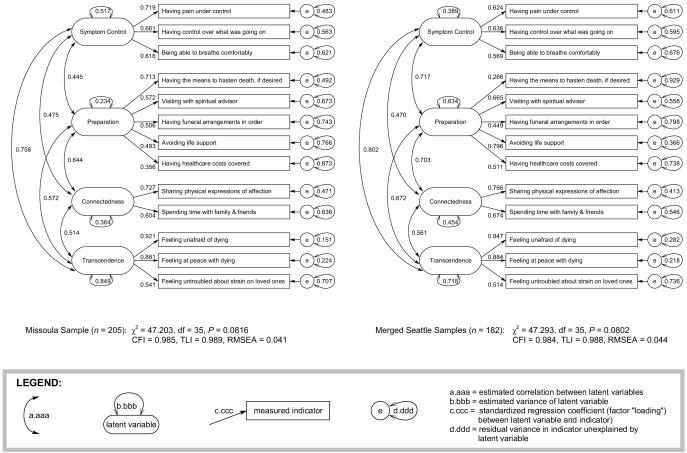

Using a reduced pool of 17 indicators, we used E/CFA methods to derive a 13-indicator, 4-factor model with better fit to the Missoula data (Figure 1; χ2 = 47.203, df = 35, P = 0.082; CFI = 0.985; TLI = 0.989; RMSEA = 0.041). We confirmed the model by applying it to data from the combined Seattle samples (χ2 = 47.293, df = 35, P = 0.080; CFI = 0.984; TLI = 0.988; RMSEA = 0.044). The final model excluded four items from the 17-indicator pool: maintaining dignity and self-respect (a high priority item), saying goodbyes, having control of bladder and bowels, being able to laugh and smile (all medium priority items). Three indicators measured the Symptom Control domain: pain under control, control over what was going on, and breathing comfort. Five measured Preparation: means to hasten death if desired, spiritual advisor visits, funeral arrangements, use/avoidance of life support, and healthcare cost coverage. Two indicators measured Connectedness: physical expressions of affection and time with family and friends. Three indicators measured Transcendence: unafraid of and at peace with dying, and being untroubled about strain on loved ones.

Figure 1. Confirmatory Factor Analysis, Domains Underlying the Quality of Dying and Death.

We tested another model that produced greater departure from fit than the four-domain model, but had a conceptual advantage. It added a single-indicator domain evaluating “maintenance of dignity and self-respect,” an item identified as a high priority for the end-of-life period (2). This indicator was significantly correlated with each of the other four domains and produced significant departure from fit when included as an indicator in the four-domain model, largely as a result of cross-loading on the four latent variables. When this indicator was modeled as a separate (fifth) domain, there was marginal fit to the Missoula sample (χ2 = 56.254, df = 39, P = 0.036; CFI = 0.981, TLI = 0.985, RMSEA = 0.046), with only the χ2 test of fit falling outside the acceptable range. However, there was greater departure from fit in the Seattle sample (χ2 = 63.026, df = 38, P = 0.007; CFI = 0.970, TLI = 0.978, RMSEA = 0.060), with both the χ2 test and the RMSEA falling outside the acceptable range.

Finally, we tested the associations of the four latent variables with the two single-item ratings of the overall quality of the end-of-life period and the quality of the moment of death (Table 4). All correlations were positive and statistically significant.

Table 4. Correlations Between QODD Domains and Single-Item Quality Ratings.

| Overall Quality of Final Week (Month) of Life |

Quality of Moment of Death |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Missoula | Seattle | Missoula | Seattle | |||||

| Corr. | P | Corr. | P | Corr. | P | Corr. | P | |

| Symptom Control | 0.508 | 0.000 | 0.626 | 0.000 | 0.493 | 0.000 | 0.383 | 0.000 |

| Preparation | 0.331 | 0.000 | 0.323 | 0.000 | 0.511 | 0.000 | 0.495 | 0.000 |

| Connectedness | 0.391 | 0.000 | 0.286 | 0.001 | 0.309 | 0.001 | 0.287 | 0.000 |

| Transcendence | 0.424 | 0.000 | 0.475 | 0.000 | 0.599 | 0.000 | 0.494 | 0.000 |

| Overall QOL | --- | --- | --- | --- | 0.424 | 0.000 | 0.452 | 0.000 |

Discussion

Two recent state-of-the-science articles on quality measurement in end-of-life research have noted a regrettable absence of theoretical foundation and testable hypotheses in empirical studies (23,24). Although some studies aimed at evaluating aspects of the end-of-life period (including those underlying development of the QODD) have begun with conceptual frameworks specific to the end-of-life experience and have used grounded theory methodology to identify concerns relevant to dying and death, most have not appealed to more general pre-existing theoretical traditions. In the current article, we began by drawing attention to two theoretical perspectives that may assist in interpreting domains underlying ratings of the quality of dying and death. Expressed in different vocabularies, Identity Theory and Existential Psychology converge in their emphasis on identity issues, the importance of reflection and the construction of meaning, the role others play in assigning meanings, changes that occur in the relative importance of specific aspects of the self-concept over time, and the effects of personal agency versus outside influence on identity formation and integration.

Although our data did not allow testing hypotheses based on these general theoretical traditions, we did test two more limited hypotheses generated during development and initial evaluation of the QODD: (a) that a single latent variable underlies the QODD indicators (41) or, alternatively, (b) that the QODD represents six underlying latent variables (11). Based on data from our samples, it is unlikely that either of these hypotheses is an adequate description of domains underlying evaluations of the dying experience. We achieved significantly better fit with a structure comprising four domains: Symptom Control, Preparation, Connectedness, and Transcendence. These domains show both similarities to, and differences from, taxonomies others have postulated or empirically discovered in studies based on responses of patients and families. The measurement model omits one item previously identified as a high priority for the end-of-life period: the maintenance of dignity and self-respect (2). However, this omission is in part a result of strong cross-loadings of dignity on multiple domains - a pattern congruent with work by other researchers, who have noted the variations in meaning different individuals assign to “dignity” and its consequent association with several domains of end-of-life experience (16,48).

Many writers have noted the impact of symptoms on the overall quality of life at the end of life (3,5,7-9,14,18,20,49), and several taxonomies include a dimension similar to our Symptom Control domain (3-5,7-10,13-16,18). Unlike most of these, our Symptom Control domain includes the dying person’s control of what was going on around him or her. The QODD developers (11), as well as others (7), included control as an important aspect of symptom management, underscoring dying persons’ need for self-efficacy and autonomy. Our analysis supports this view, suggesting patients’ active participation in attempts to manage symptoms, and adding a psychosocial element to even this medical domain. The Symptom Control domain was strongly correlated with Transcendence and overall quality of life in both samples, and with Preparation in the Seattle sample (Table 4 and Figure 1). Symptoms create barriers to experiencing positive aspects of dying (8,20,39,49,50), and outcomes experienced in other domains may influence patients’ perceptions of symptom distress (3,21,49). Of the four latent variables in our model, Symptom Control had the strongest correlation with the global quality-of-life rating.

Dying patients, as well as their family, friends, and care professionals, have identified preparatory tasks as an important dimension in the quality of dying and death (9,19,20,22,51,52). Several writers (5,6,9,49,53) have noted dying persons’ reports of addressing practical matters as a way of removing burden (financial obligation, funeral planning, decision-making about treatments) from family members. These observations suggest a link between our Preparation domain and Identity Theorists’ notion of personal agency and its role in protecting valued identities (29). Others have reported associations of preparation activities with the exercise of free will and establishment of control over external forces - activities Existential Psychologists link to well-being (6). The exclusion of three items (feeling at peace, unafraid, and unworried about strain on loved ones), which the QODD developers expected to fall in the preparation domain, suggests that practical and spiritual aspects of preparation may represent separate dimensions. The Preparation domain showed strong correlation in both samples with Connectedness and Transcendence, supporting findings that advance planning may assist terminally ill persons in strengthening relationships to others and that “having everything in place” may allow being at peace and accepting death (6).

Other researchers have identified domains similar to our Connectedness domain, emphasizing the importance of ties to family and friends for communication and support (3-8,10,13,14,16,18,22). Several writers have noted the increasing isolation of dying persons over the course of terminal illness (37,38,51) and have documented the positive value of deepening (or establishing) ties to a supportive inner circle that provides opportunities for self-verification based on what one is, rather than on what one can do (5,20,54,55). This domain supports Identity Theory’s emphasis on individuals’ continued attempts to verify important role-identities and retain them in an integrated self-concept, as well as Existential Psychology’s emphasis on individuals’ need to establish and maintain deep connections to others. In addition to its association with Preparedness and Symptom Control, Connectedness showed a strong correlation with Transcendence, mirroring others’ findings that affirmative end-of-life connections with loved ones create the sense in dying persons that they are leaving a positive legacy, that their lives have intrinsic value, and that they do not constitute burdens to family and friends (13,20,49).

Finally, the Transcendence domain is particularly germane to the evaluation of the dying- and-death experience, setting quality ratings for this life stage apart from those for other periods of life (3,8,56). Several researchers have identified domains that include themes related to existential well-being, finding meaning and value in life, spiritual readiness for death, and being unafraid and at peace (3,4,6-9,13,14,22). A strength of the QODD is its use of generalized versions of “being at peace” and “being unafraid.” Steinhauser et al. (57) found that “being at peace” carried different meanings, depending upon respondents’ spiritual orientation (peace with others, peace with God, peace with self), but that all meanings included notions of transcendence. Asking in general about “being at peace with dying” allowed incorporation of social, spiritual, and emotional peacefulness. Similarly, Charmaz (37) noted differences in the meaning of “fear” for dying persons (fear of the process of dying, fear of what happens after death, fear of ceasing to “be”). By using the generalized “unafraid of dying,” the QODD covers a variety of potential sources of fear. The third item in the Transcendence domain reflected absence of worry about strain on loved ones. This item corresponds to fear of being a burden, which other researchers have placed in domains related to connectedness (14) or preparation (13). However, several writers have also noted its relationship to feelings of purpose and transcendence. In particular, this item captures the tendency for some dying persons to translate diminished self-worth into feelings of burdensomeness, and for others to accept dependence as a way of giving their loved ones a sense of purpose and meaning (5,21,49,54,58). The notion of individuals’ need to establish transcendent identity is a hallmark of the Existential Psychology tradition. Transcendence was strongly correlated with the quality of the moment of death in both samples.

Our study makes several contributions to the literature on the quality of end-of-life experience. First, our analysis involves the QODD instrument, which has among its strengths an attention to respondents’ value systems - a characteristic several writers have emphasized as important in assessments of quality of dying and death (7,8,20,38,54). A number of instruments designed to measure the quality of the end-of-life experience base their assessments on the occurrence of events, at least some of which are simply assumed to affect quality of life in a positive (or negative) direction (13,22). By contrast, the QODD makes no assumptions about whether an event of interest has positive, neutral, or negative value for the respondent. Rather, respondents use a bad-to-good scale to evaluate what actually occurred - thus granting weight to their own value systems. For example, if there were no visits with a spiritual advisor, the respondent might evaluate the non-occurrence anywhere from “the worst possible experience” to “a perfect experience,” depending upon whether such visits were desired and/or important.

Second, our study tests and rejects two hypothesized measurement models underlying the QODD and then specifies and validates an alternative model with better fit to empirical data. Researchers have noted the importance of identifying domains relative to the end-of-life experience and developing instruments capable of assessing domain-specific outcomes (3,14). Individual end-of-life needs differ, and quality measures must be sensitive to these differences. Our finding of a set of four distinct quality domains at the end of life suggests that outcomes are not homogeneous in quality and that a single measure of overall quality may provide insufficient evidence for guiding clinical practice, evaluating interventions to improve quality of care, or assessing the status or trajectory of individual patients - all stated goals for measuring end-of-life outcomes (59).

Third, our study employs an analysis method that allows testing the fit of hypothesized measurement models, provides modification tools, and facilitates the confirmation of improved models. In their recommendations for advancing the science of measurement at the end of life, Tilden and colleagues (59) cite the importance of testing conceptual models with sophisticated statistical techniques that facilitate the understanding of relationships among key variables in end-of-life care. Although a number of researchers have proposed end-of-life domains based on qualitative research and conceptual understandings, fewer have carried out quantitative research designed to test the hypothesized models. Our CFA test of the QODD developers’ qualitatively-developed conceptual domains suggests the need for moving beyond conceptual dimensions to domains validated by empirical research. Among researchers who have reported empirical tests to develop or validate domains, most have restricted their analyses to exploratory factor or principal components analysis (EFA or PCA). Our use of the E/CFA technique, after failing to confirm the QODD conceptual models, allowed identification of areas of misfit and, ultimately, a more parsimonious latent variable model than would have been possible with EFA or PCA.

Our study has several important limitations. First, the QODD relies on proxy respondents and their retrospective evaluations. Although retrospective assessment offers several advantages, among them a more precise mapping of outcomes to a known end-of-life period and a reduction in burden (or missing data) through avoiding data collection during the last phases of illness, it also introduces concerns about reliability and validity related to inaccurate recall, reinterpretation in the light of new information, and the effects of bereavement (23,60-62). Bereavement can have variable and unpredictable effects on questionnaire responses, sometimes more accurately reflecting the emotional state of the respondent than the experience of the decedent, and may change over the course of the bereavement period (60). Reinterpretation may be particularly influential for caregivers who are active participants in the patient’s end-of-life period, especially those who are present at the moment of death (40).

Second, researchers have noted that preferences related to death and dying are individualized and that the best tools for assessing the quality of dying and death would include methods for weighting the importance of various aspects of the experience. Our QODD instrument did not include a weighting mechanism. To compensate in part for this limitation, we selected for our reduced pool of indicators 17 items that previous research (2) had identified as priorities. However, priorities may change over the course of terminal illness, and we cannot be certain that these 17 items retained precedence for our samples as death became imminent.

Third, in our final measurement model, only the Preparation domain included more than three indicators. Models that include “poorly defined” factors, including those with only two or three indicators, may produce problems in generalizability (45). Future enhancements to the QODD will benefit from additional indicators for these domains. Research will also be necessary to determine whether, and how, the item measuring dignity and self-respect fits into dying-and-death quality evaluations.

Fourth, the Missoula and Seattle samples produced some notable differences in the size of parameter estimates, at the level of both factor loadings and correlations. These differences were magnified in unstandardized estimates (data not shown), and we lacked parallel data from the three samples that would have permitted a thorough investigation of possible contributors. However, they suggest that the “meaning” of the latent variables may be somewhat different in the two locations.

Finally, we based our analyses on data from relatively small samples, drawn from two communities in northwestern United States that may not be representative of deaths in other geographic areas. In particular, our samples showed idiosyncrasies with regard to race-ethnicity, place of death, and level of education. Decedents in both Missoula and Seattle underrepresented racial-ethnic minorities (63), and Seattle decedents overrepresented home deaths (63) and higher education levels (64). In addition, although the participation rates for these studies were comparable to other studies of terminal or severely ill patients and their families, they nonetheless introduce the possibility of a non-responder bias that we cannot assess.

Conclusions and Next Steps

Retrospective reports from caregivers will remain an important tool for assessing the quality of dying and of end-of-life care. Until we reach some consensus on measuring the social, spiritual, and preparatory dimensions of the end-of-life experience, there is danger that end-of-life care will remain narrowly focused on symptoms (65). Our analysis suggests that neither a single QODD scale score nor six subscale scores representing hypothesized conceptual domains represent optimal methods for using QODD data. The fact that our four-factor measurement model provided acceptable fit to two samples that were significantly different on a number of characteristics suggests some promise of generalizability. However, we have identified weaknesses in the QODD that must be addressed. We believe that important next steps will include the use of additional focus groups and in-depth interviews to inform QODD revisions, followed by administration of a revised QODD to a more comprehensive sample and further investigation of measurement and structural models. Accomplishment of these tasks will allow better understanding of domains important to improvements in clinical practice and assessment of individuals’ dying-and-death experiences. Until that work is completed, we would recommend using an interim 17-item version of the QODD that includes items respondents have reported to be end-of-life priorities (see Appendix) and to focus attention on four latent variables, based on 13 of these indicators, to measure variability in outcomes over important domains of experience.

Acknowledgments

The following organizations provided financial support for the studies included in this article:1) The Robert Wood Johnson Foundation - Missoula study; 2) Agency for Healthcare Quality and Research grant #R03 HS09540 - hospice study; 3) National Cancer Institute grant #5 R01 CA106204 - clinical trial; 4) Lotte & John Hecht Memorial Foundation - clinical trial.

Appendix

Quality of Dying and Death - 17-Item Version

Each item includes a filter question reporting what actually occurred during the final period of the decedent’s life, followed by a rating of what occurred. The first 10 filter questions ask the frequency of occurrence and use the following response options:

| 0 none of the time |

1 a little bit of the time |

2 some of the time |

3 a good bit of the time |

4 most of the time |

5 all of the time |

1a. How often did X appear to have her/his pain under control?

2a. How often did X appear to have control over what was going on around her/him?

3a. How often did X have control of her/his bladder or bowels?

4a. How often did X breathe comfortably?

5a. How often did X appear to feel at peace with dying?

6a. How often did X appear to be unafraid of dying?

7a. How often did X laugh and smile?

8a. How often did X appear to be worried about strain on her/his loved ones?

9a. How often did X appear to keep her/his dignity and self-respect?

10a. How often did X spend time with family and friends?

The last 7 filter questions ask whether the event occurred and are answered with a yes/no response.

11a. Was X touched or hugged by her/his loved ones?

12a. Were all of X ’s health care costs taken care of?

13a. Did X say goodbye to loved ones?

14a. Did X have one or more visits from a religious or spiritual advisor?

15a. Was a mechanical ventilator or kidney dialysis used to prolong X ’s life?

16a. Did X have the means to end her/his life if s/he needed to?

17a. Did X have her/his funeral arrangements in order prior to death?

After each filter question, the respondent rates the decedent’s experience, using the following scale:

1b to 17b. How would you rate this aspect of X ’s dying experience?

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Steinhauser KE, Christakis NA, Clipp EC, et al. Factors considered important at the end of life by patients, family, physicians, and other care providers. JAMA. 2000;284:2476–2482. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.19.2476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Downey L, Engelberg RA, Curtis JR, Lafferty WE, Patrick DL. Shared priorities for the end-of-life period. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2009;37(2):175–188. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2008.02.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Emanuel EJ, Emanuel LL. The promise of a good death. Lancet. 1998;351(Suppl 2):21–29. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(98)90329-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Byock IR, Merriman MP. Measuring quality of life for patients with terminal illness: the Missoula-VITAS quality of life index. Palliat Med. 1998;12:231–244. doi: 10.1191/026921698670234618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Singer PA, Martin DK, Kelner M. Quality end-of-life care: patients’ perspectives. JAMA. 1999;281:163–168. doi: 10.1001/jama.281.2.163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Martin DK, Thiel EC, Singer PA. A new model of advance care planning: observations from people with HIV. Arch Intern Med. 1999;159:86–92. doi: 10.1001/archinte.159.1.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fowler FJ, Coppola KM, Teno JM. Methodological challenges for measuring quality of care at the end of life. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1999;17:114–119. doi: 10.1016/s0885-3924(98)00133-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stewart AL, Teno J, Patrick DL, Lynn J. The concept of quality of life of dying persons in the context of health care. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1999;17:93–108. doi: 10.1016/s0885-3924(98)00131-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Steinhauser KE, Clipp EC, McNeilly M, et al. In search of a good death: observations of patients, families, and providers. Ann Intern Med. 2000;132:825–832. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-132-10-200005160-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Emanuel LL, Alpert HR, DeWitt CB, Emanuel EJ. What terminally ill patients care about: toward a validated construct of patients’ perspectives. J Palliate Med. 2000;3:419–431. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2000.3.4.419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Patrick DL, Engelberg RA, Curtis JR. Evaluating the quality of dying and death. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2001;22:717–726. doi: 10.1016/s0885-3924(01)00333-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Teno JM, Clarridge B, Casey V, Edgman-Levitan S, Fowler J. Validation of toolkit after-death bereaved family member interview. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2001;22:752–758. doi: 10.1016/s0885-3924(01)00331-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Steinhauser KE, Bosworth HB, Clipp EC, et al. Initial assessment of a new instrument to measure quality of life at the end of life. J Palliat Med. 2002;5:829–841. doi: 10.1089/10966210260499014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cohen SR, Leis A. What determines the quality of life of terminally ill cancer patients from their own perspective? J Palliat Care. 2002;18:48–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pierson CM, Curtis JR, Patrick DL. A good death: a qualitative study of patients with advanced AIDS. AIDS Care. 2002;14:587–598. doi: 10.1080/0954012021000005416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chochinov HM, Hack T, McClement S, Kristjanson L, Harlos M. Dignity in the terminally ill: a developing empirical model. Soc Sci Med. 2002;54:433–443. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(01)00084-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schwartz CE, Mazor K, Rogers J, Ma Y, Reed G. Validation of a new measure of concept of a good death. J Palliat Med. 2003;6(4):575–584. doi: 10.1089/109662103768253687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bosworth HB, Steinhauser KE, Orr M, et al. Congestive heart failure patients’ perceptions of quality of life: the integration of physical and psychosocial factors. Aging Ment Health. 2004;8:83–91. doi: 10.1080/13607860310001613374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cohen LM, Germain MJ. Measuring quality of dying in end-stage renal disease. Semin Dial. 2004;17:376–379. doi: 10.1111/j.0894-0959.2004.17348.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Emanuel L, Bennett K, Richardson VE. The dying role. J Palliat Med. 2007;10:159–168. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2006.0134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Knight SJ, Emanuel L. Processes of adjustment to end-of-life losses: a reintegration model. J Palliat Med. 2007;10:1190–1198. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2006.0068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Munn JC, Zimmerman S, Hanson LC, et al. Measuring the quality of dying in long-term care. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55:1371–1879. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01293.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Steinhauser KE. Measuring end-of-life care outcomes prospectively. J Palliat Med. 2005;8(Suppl 1):S30–S41. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2005.8.s-30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.George LK. Research design in end-of-life research: state of science. Gerontologist. 2002;42(3):86–98. doi: 10.1093/geront/42.suppl_3.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Goffman E. The presentation of self in everyday life. Doubleday; New York: 1959. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Turner RH. Role taking: process versus conformity. In: Rose AM, editor. Human behavior and social processes: an interactionist approach. Houghton Mifflin; Boston: 1962. pp. 20–40. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Glaser BG, Strauss AL. Awareness contexts and social interaction. In: Fulton R, editor. Death and identity. Revised ed. Charles Press Publishers; Bowie, MD: 1976. pp. 144–158. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wells LE, Stryker S. Stability and change in self over the life course. In: Baltes PB, Featherman DL, Lerner RM, editors. Life-span development and behavior. Vol. 8. Erlbaum; Hillsdale, NJ: 1988. pp. 191–229. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ichiyama MA. The reflected appraisal process in small-group interaction. Soc Psychol Q. 1993;56:87–99. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cast AD, Stets JE, Burke PJ. Does the self conform to the views of others? Soc Psychol Q. 1999;62:68–82. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stryker S. Symbolic interactionism: a social structural version. Blackburn Press; Caldwell, NJ: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hewitt JP. Self and society: a symbolic interactionist social psychology. 9th ed. Allyn and Bacon; Boston: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Burke PJ, Owens TJ, Serpe R, Thoits PA, editors. Advances in identity theory and research. Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers; New York: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Francis LE. Feeling good, feeling well: identity, emotion, and health. In: Burke PJ, Owens TJ, Serpe RT, Thoits PA, editors. Advances in identity theory and research. Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers; New York: 2003. pp. 123–134. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Burke PJ. Identity change. Soc Psychol Q. 2006;69:81–96. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Koole SL, Greenberg J, Pyszczynski T. Introducing science to the psychology of the soul: experimental existential psychology. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 2006;15:212–216. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Charmaz K. The social reality of death: death in contemporary America. Addison-Wesley; Reading, MA: 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Field D. Awareness and modern dying. Mortality (Abingdon) 1996;1:255–265. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Parker-Oliver D. The social construction of the “dying role” and the hospice drama. Omega (Westport) 19992000;40:493–512. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Valentine C. The “moment of death.”. Omega (Westport) 2007;55:219–236. doi: 10.2190/OM.55.3.d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Curtis JR, Patrick DL, Engelberg RA, et al. A measure of the quality of dying and death: initial validation using after-death interviews with family members. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2002;24:17–31. doi: 10.1016/s0885-3924(02)00419-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Engelberg RA, Patrick DL, Curtis JR. Correspondence between patients’ preferences and surrogates’ understandings for dying and death. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2005;30:498–509. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2005.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Downey L, Diehr P, Standish LJ, et al. Might massage or guided meditation provide “means to a better end”? primary outcomes from an efficacy trial with patients at the end of life. J Palliat Care. in press. AU: ANY UPDATE? [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. [Accessed on April 7, 2009];Quality of Death and Dying Questionnaire (original interview instrument) Available at: http://depts.washington.edu/eolcare/instruments/uwqodd-soadi.pdf.

- 45.Brown TA. Confirmatory factor analysis for applied research. The Guilford Press; New York: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus user’s guide. 4th ed. Muthén & Muthén; Los Angeles: 19982006. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yu C-Y. Evaluating cutoff criteria of model fit indices for latent variable models with binary and continuous outcomes [dissertation] UCLA; Los Angeles: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chochinov HM, Kristjanson LJ, Hack TF, et al. Dignity in the terminally ill: revisited. J Palliat Med. 2006;9:666–672. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2006.9.666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Block SD. Psychological considerations, growth, and transcendence at the end of life: the art of the possible. JAMA. 2001;285:2898–2905. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.22.2898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Singer PA, MacDonald N. Bioethics for clinicians: quality end-of-life care. CMAJ. 1998;159:159–162. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hanson LC, Henderson M, Menon M. As individual as death itself: a focus group study of terminal care in nursing homes. J Palliat Med. 2002;5:117–125. doi: 10.1089/10966210252785088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Steinhauser KE, Christakis NA, Clipp EC, et al. Preparing for the end of life: preferences of patients, families, physicians, and other care providers. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2001;22:727–737. doi: 10.1016/s0885-3924(01)00334-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Vig EK, Pearlman RA. Quality of life while dying: a qualitative study of terminally ill older men. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51:1595–1601. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2003.51505.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Byock I. Dying well: peace and possibilities at the end of life. Riverhead Books; New York: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Charmaz K. Loss of self: a fundamental form of suffering in the chronically ill. Sociol Health Illn. 1983;5:168–195. doi: 10.1111/1467-9566.ep10491512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Steinhauser KE, Clipp EC, Tulsky JA. Evolution in measuring the quality of dying. J Palliat Med. 2002;5:407–414. doi: 10.1089/109662102320135298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Steinhauser KE, Voils CI, Clipp EC, et al. “Are you at peace?” One item to probe spiritual concerns at the end of life. Ann Intern Med. 2006;166:101–105. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.1.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Chochinov HM, Kristjanson LJ, Hack TF, et al. Burden to others and the terminally ill. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2007;34:463–471. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2006.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Tilden VP, Tolle S, Drach L, Hickman S. Measurement of quality of care and quality of life at the end of life. Gerontologist. 2002;42(3):71–80. doi: 10.1093/geront/42.suppl_3.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Teno JM. Measuring end-of-life care outcomes retrospectively. J Palliat Med. 2005;8(Suppl 1):S42–S49. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2005.8.s-42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Higginson I, Priest P, McCarthy M. Are bereaved family members a valid proxy for a patient’s assessment of dying? Soc Sci Med. 1994;38:553–557. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(94)90251-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hinton J. How reliable are relatives’ retrospective reports of terminal illness? patients’ and relatives’ accounts compared. Soc Sci Med. 1996;43:1229–1236. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(95)00437-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.National Center for Health Statistics [Accessed March 28, 2008];Deaths by place of death, age, race, and sex: United States. 2002 Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/dvs/mortfinal2002_work309.pdf.

- 64.U.S. Census Bureau [Accessed March 28, 2008];Educational attainment of people 18 years and over, by metropolitan and nonmetropolitan residence, age, sex, race and Hispanic origin. 2002 March; Available at: http://www.census.gov/population/socdemo/education/ppl-169/tab11.pdf.

- 65.Hales S, Zimmermann C, Rodin G. The quality of dying and death. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168:912–918. doi: 10.1001/archinte.168.9.912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]