Abstract

Background

We have previously reported significant response to placebo in randomized controlled trials of treatments for cancer related fatigue (CRF). We conducted a retrospective study to determine the frequency and predictors of response to placebo effect and nocebo effect in patients with CRF treated in those trials.

Methods

We reviewed the records of 105 patients who received placebo in two previous randomized clinical trials conducted by our group and determined the proportion of patients who demonstrated clinical response to fatigue, defined as an increase in FACIT-F score of 7 or greater from baseline to day 8, and the proportion of patients with a nocebo effect, defined as those reporting >2 side effects. Baseline patient characteristics and symptoms recorded using the Edmonton Symptom Assessment Scale (ESAS) were analyzed to determine their association with placebo and nocebo effects.

Results

59 (56%) patients had a placebo response. Worse baseline anxiety and well-being subscale score (univariate) and well-being (multivariate) were significantly associated with placebo response. Common side effects reported were insomnia (79%), anorexia (53%), nausea (38%) and restlessness (34%). Multivariate analysis showed that worse baseline (ESAS) sleep, appetite, and nausea were associated with increased reporting of the corresponding side effects.

Conclusions

More than half of advanced cancer patients enrolled in CRF trials had a placebo response. Worse baseline physical well-being score was associated with placebo response. Patients experiencing specific symptoms at baseline were more likely to report these as side effects of the medication. These findings should be considered in the design of future CFR trials.

Keywords: fatigue, placebo, nocebo, neoplasms

Introduction

Cancer related fatigue (CRF) is defined as “a distressing persistent, subjective sense of tiredness or exhaustion related to cancer or cancer treatment that is not proportional to recent activity and interferes with usual functioning and does not usually resolve with rest”.1 CRF is the most common symptom reported in patients with advanced cancer 2, 3 and is estimated to be present in about 60–90% of patients receiving active treatment, and in 30–75% of cancer survivors.4–6 Multiple therapeutic approaches have been proposed to treat this condition. To date, however, there is no single drug intervention considered standard treatment from CRF.

In two randomized controlled trials, our group investigated the psychostimulant methylphenidate and the anticholinesterase inhibitor donepezil in the treatment of CRF. These trials failed to demonstrate a significant difference between the drugs and placebo. In both trials, we noted considerable response to placebo.7, 8 This so-called placebo effect has previously been extensively described in the literature for pain, Parkinson’s disease, the immune system, asthma and depression.9–12

Placebo is described as a biologically inert substance, or any other form of therapy or intervention, that when given as an intervention is not expected to produce favorable outcomes. A placebo effect is any favorable psychobiological effect following the administration of a placebo.13 To distinguish the therapeutic effect of an inert substance from the harmful effects that it may cause, the term nocebo, which in Latin means “I will harm”, is used. A nocebo effect is defined as any distressing effect of a placebo, and is less studied in the literature.14

As with randomized controlled trials of treatments for other symptoms, such as pain, randomized controlled trials of treatment for fatigue may be influenced by significant confounding effect of the placebo effect and nocebo effect which may prevent accurate estimation of the power needed to determine efficacy. To our knowledge, no studies have been published that show the placebo and nocebo effects on fatigue. The purpose of our study was to determine the frequency and predictors of placebo and nocebo effect in patients with CRF, which could allow for better design of future fatigue treatment trials and also aid future researchers in their interpretation of results, particularly with regard to reported side effects.

Methods

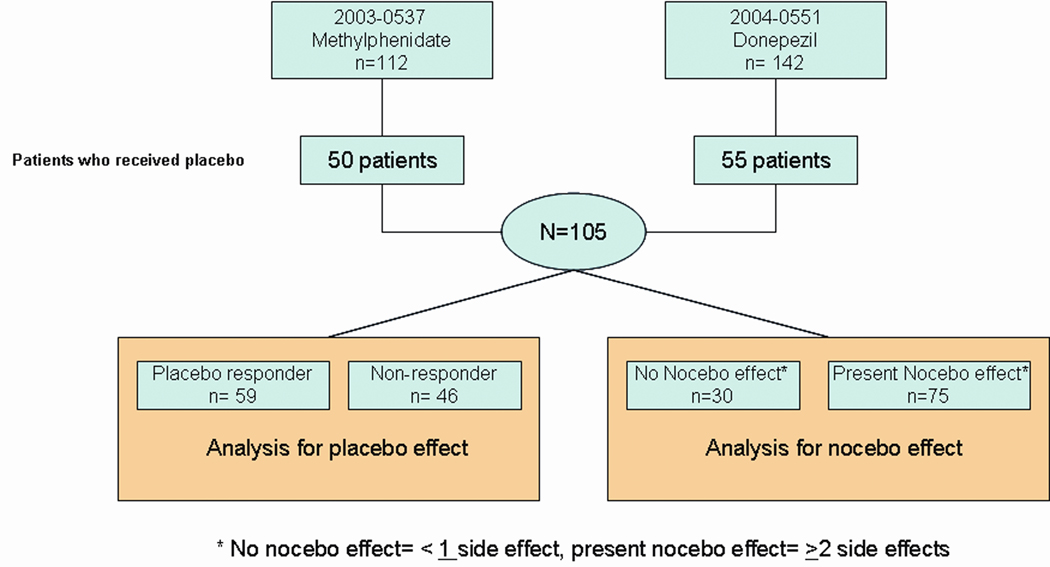

We conducted new analyses of data already collected from 254 patients with CRF who participated in two clinical trials previously conducted by our team between July, 1st, 2003 and July 6, 2006. The current study was approved by the institutional review board of The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center. Two trials have already been reported.7, 8 In one trial, patients were randomly assigned to receive either methylphenidate or placebo, and in the other trial, patients were randomly assigned to receive either donepezil or placebo. The patients took their medications for 7 days. All patients had advanced cancer and reported a fatigue score of at least 4 on the Edmonton Symptom Assessment Scale (ESAS)15 during the last 24 hours on at least 4 consecutive days. Medications, including chemotherapy that the patients were already taking prior to the trial were not restricted or discontinued. Patients taking anti-depressants were on stable doses during the study period. The patients were included in the current retrospective study if they received placebo as an intervention for fatigue. There were 22 patients randomized to placebo who were not evaluable due to dropping out or missing data. A total of 105 patients who received placebo in the two previous trials were pooled for analysis. Data collection is described in the flowchart in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Study Flowchart.

Patients who received placebo from two randomized clinical trials on fatigue were pooled for analysis for placebo and nocebo effect.

The following demographic information was collected: age, gender, race, marital status, educational level, and primary cancer diagnosis. Also collected were Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy-Fatigue (FACIT-F) scores, ESAS scores, Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE) scores, and reported side effects was also collected.15–17 FACIT-F is an assessment tool that has been validated for use in CRF. It is composed of 4 domains of well-being (physical, social, emotional and functional) and an additional 13 point fatigue sub score. The patient rates the intensity of fatigue and other symptoms on a scale of 0 –4. The scores range from 0–54, and higher scores correspond to less fatigue.16 The ESAS is a validated tool that is used to assess the intensity of nine common symptoms in patients with cancer or chronic illness (pain, fatigue, nausea, depression, anxiety, anorexia, drowsiness, shortness of breath, and sleep) as well as feeling of well-being. The patient rates each symptom on a scale of 0 to 10, with 0 being no symptom and 10 being the worst possible symptom.15, 18 The MMSE is a 30 point assessment tool that is used to determine cognitive status, with the higher number denoting more intact cognition.17

In both studies, the patients were asked if they developed side effects from the drug. The side effects listed were slurred speech, restlessness, behavioral change, dizziness, vertigo, tachycardia, insomnia, and anorexia.

Our study had two parts, the placebo part and the nocebo part. In this paper, the term placebo will be used to designate the positive and therapeutic effects of the inert substance, and nocebo will be used to denote the effects of the inert substance that were considered harmful to the patient. For the placebo part, patients that were included in the study were classified as either responders or non-responders to placebo. A patient was considered to be a responder if there was an improvement (increase) in FACIT-F score of at least 7 points between baseline and end of study (day 8). This definition of responder was taken from our previous studies.7, 8 For the nocebo part of our study, patients who reported ≥2 side effects from the inert drug were considered to have a nocebo effect. This cut-off point was based on the fact that the median number of side effects reported by patients was 2.

To determine the association between baseline characteristics, FACIT-F Scores, ESAS scores, MMSE and response to placebo, the responders and non-responders were compared using the Chi Square test for categorical variables and a Wilcoxon rank-sum test for continuous variables. Subsequent multivariate regression analysis was done using variables that were noted to be significant to determine the best model for predictors. Significance levels less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant. The same statistical analyses were done to determine the association between various factors and nocebo effect.

Results

Patient demographic characteristics are summarized in Table 1. Among the 105 patients included in this analysis, 63 (60%) were females, 79 (75%) were Caucasians, 69 (68%) were married, and 52 (51%) had a college degree or higher. The most common primary malignancy was breast cancer, which was the primary malignancy in 35 (33%) patients.

Table 1.

Demographics of Patients that received Placebo in Fatigue Clinical Trials

| Patient Characteristics | Number of Patients (%) n=105 |

|---|---|

| Female Gender | 63 (60) |

| Race | |

| Asian | 2 (2) |

| Black | 10 (10) |

| Caucasian | 79 (75) |

| Hispanic | 13 (12) |

| Other | 1 (1) |

| Marital Status | |

| Married | 69 (68) |

| Divorced | 16 (16) |

| Single | 16 (16) |

| Education | |

| College or higher | 52 (51) |

| High school | 28 (27) |

| Less than high school | 22 (22) |

| Primary Cancer Diagnosis | |

| Breast | 35 (33) |

| Gastrointestinal | 7 (7) |

| Genitourinary | 12 (11) |

| Lung | 20 (19) |

| Gynecologic | 4 (4) |

| Head and neck | 6 (6) |

| Hematologic | 14 (13) |

| Others | 7 (7) |

Fifty nine (56%) patients reported a response to the placebo. Patient characteristics of responders and non-responders to placebo are summarized in Table 2. On univariate analysis, factors significantly associated with response to placebo were worse baseline ESAS anxiety and worse baseline FACIT-F physical well-being subscale score, fatigue subscale score and total FACIT-F score (Table 2). Other variables tested did not show any significant association with response to placebo. On multivariate regression analysis, only worse baseline FACIT-F physical well-being subscale score was found to be a significant predictor of placebo response (OR= 0.86, p= 0.001).

Table 2.

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of Responders and Non-responders to Placebo in Fatigue Clinical Trials

| Responders (n= 59; 56%) |

Non-responders (n= 46; 44%) |

P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||

| Female | 37 (63) | 26 (57) | 0.52 |

| Race | 0.53 | ||

| Asian | 1 (2) | 1 (2) | |

| Black | 7 (12) | 3 (7) | |

| Caucasian | 43 (73) | 36 (78) | |

| Hispanic | 7 (12) | 6 (13) | |

| Other | 1 (2) | 0 (0) | |

| Median Age (Range), in years | 59 (37–84) | 58 (37–78) | 0.63 |

| Marital Status | 0.75 | ||

| Married | 40 (70) | 29 (66) | |

| Divorced | 9 (16) | 7 (16) | |

| Single | 8 (14) | 8 (18) | |

| Education | 0.16 | ||

| College or higher | 28 (49) | 24 (53) | |

| High school | 13 (23) | 15 (33) | |

| Less than high school | 16 (28) | 6 (14) | |

| Primary Cancer Diagnosis | 0.49 | ||

| Breast | 18 (31) | 17 (37) | |

| Gastrointestinal | 5 (8) | 2 (4) | |

| Genitourinary | 4 (7) | 8 (17) | |

| Lung | 13 (22) | 7 (15) | |

| Gynecologic | 2 (3) | 2 (4) | |

| Head and neck | 5 (8) | 1 (2) | |

| Hematologic | 9 (15) | 5 (11) | |

| Others | 3 (5) | 4 (9) | |

| Mini-Mental Score (Median, Range) | 30 (24–30) | 30 (24–30) | 0.70 |

| PerformanceStatus (Median, Range) | 2(0–4) | 2 (0–3) | 0.169 |

|

Median Baseline FACIT-F Score (Range) |

|||

| Physical Wellbeing | 13 (3–25) | 17 (7–24) | 0.001 |

| Social/Family | 23 (7–28) | 24 (13–28) | 0.17 |

| Emotional | 18 (6–24) | 18 (9–24) | 0.72 |

| Functional | 12 (4–25) | 14 (6–28) | 0.19 |

| Fatigue subscale | 16 (1–47) | 19 (4–43) | 0.045 |

| Total FACIT-F score | 80 (38–141) | 94 (61–134) | 0.004 |

| Median Baseline ESAS (Range) | |||

| Pain | 4 (0–10) | 3 (0–10) | 0.112 |

| Fatigue | 7 (4–10) | 7 (4–10) | 0.44 |

| Nausea | 0 (0–9) | 0 (0–6) | 0.24 |

| Depression | 3 (0–8) | 2 (0–9) | 0.11 |

| Anxiety | 3 (0–8) | 2 (0–8) | 0.01 |

| Drowsiness | 5 (0–10) | 4 (0–10) | 0.88 |

| Shortness of breath | 2 (0–10) | 2 (0–10) | 0.42 |

| Appetite | 3 (0–10) | 3 (0–10) | 0.89 |

| Sleep | 5 (0–10) | 5 (0–10) | 0.34 |

| Well-Being | 5 (0–9) | 5 (0–9) | 0.44 |

Pooled patients reported 10 different side effects. These side effects and the proportions of patients who reported each side effect are listed in Table 3. Eight side effects reported by patients in both studies. In the methylphenidate study, nausea was reported in addition to the other eight side effects. In the donepezil study, skin changes were reported in addition to the other eight side effects. The most common side effects reported were insomnia (79%), followed by anorexia (53%), nausea (33%) and restlessness (34%).

Table 3.

Side Effects Reported by Patients Who Received Placebo

| Side Effects* | Number of patients (%) |

|---|---|

| Slurred speech | 5/105 (5) |

| Restlessness | 35/104 (34) |

| Behavioral change | 14/105 (13) |

| Dizziness | 31/105 (30) |

| Vertigo | 14/105 (13) |

| Tachycardia | 13/102 (13) |

| Insomnia | 83/105 (79) |

| Anorexia | 56/105 (53) |

| Nausea | 21/55 (33) |

| Skin problems | 10/50 (20) |

All listed side effects were reported by patients in both studies expect for nausea, which was reported only by patients in the methylphenidate study, and skin problems, which were reported only by patients in the donepezil study.

There was no association between the reporting of side effects and response or lack of response to placebo. Multivariate analysis for each of the symptom showed that worse baseline ESAS sleep, appetite, and nausea were associated with increased reporting of these side effects. With each unit increase in FACIT-F functional well-being score, patients were 15% less likely to report insomnia. With each unit increase in the FACIT-F fatigue subscale score is associated with patients reporting less anorexia. Patients with baseline nausea are twice as likely to report nausea as a side effect and those with baseline anxiety are more likely to report restlessness. Other variables that showed significant association in our multivariate logistic regression model are shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Multivariate Logistic Regression Analyses of Nocebo Effect

| Side Effect | Variables of Nocebo Effect | OR | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Restlessness | Baseline FACIT-F Total Score | 1.00 | 0.94 |

| Baseline FACT-G Physical Well-being score | 0.99 | 0.87 | |

| Baseline Performance Status | 1.39 | 0.20 | |

| Baseline ESAS Anxiety | 1.24 | 0.02 | |

| Baseline ESAS Pain | 1.07 | 0.41 | |

| Baseline ESAS Drowsiness | 1.05 | 0.53 | |

| Baseline ESAS Shortness of breath | 1.00 | 0.96 | |

| Baseline ESAS Well-being | 1.05 | 0.65 | |

| Behavioral change | Age | 1.10 | 1.01 |

| Baseline ESAS Fatigue | 0.67 | 0.05 | |

| Baseline ESAS Nausea | 0.84 | 0.41 | |

| Primary cancer diagnosis | 3.29 | 0.08 | |

| Mini-Mental Exam Score | 0.87 | 0.63 | |

| Baseline FACT-G Social/Family well-being | 0.84 | 0.11 | |

| Dizziness | Baseline FACIT-F Total Score | 1.01 | 0.46 |

| Baseline FACT-G Physical Well-being | 0.99 | 0.95 | |

| Baseline Performance status | 1.87 | 0.03 | |

| Baseline Drowsiness | 1.04 | 0.62 | |

| Baseline ESAS Sleep | 1.06 | 0.50 | |

| Baseline ESAS Well-being | 1.20 | 0.06 | |

| Tachycardia | Marital Status | 0.58 | 0.46 |

| Educational Level | 4.83 | 0.06 | |

| Baseline FACT-G Fatigue subscale | 1.23 | 0.001 | |

| Baseline Performance Status | 3.97 | 0.03 | |

| Baseline ESAS Depression | 1.54 | 0.02 | |

| Baseline ESAS Sleep | 1.40 | 0.04 | |

| Baseline ESAS Drowsiness | 0.85 | 0.46 | |

| Baseline ESAS Nausea | 1.04 | 0.83 | |

| Baseline ESAS Well-being | 1.04 | 0.84 | |

| Insomnia | Baseline Mini Mental Score | 1.80 | 0.01 |

| Baseline FACIT-F Total Score | 1.01 | 0.77 | |

| Baseline FACT-G Functional Well-being | 0.85 | 0.01 | |

| Baseline FACT-G Physical well-being | 0.90 | 0.17 | |

| Baseline FACT-G Emotional well-being | 0.86 | 0.27 | |

| Baseline Performance Status | 1.32 | 0.49 | |

| Baseline ESAS Nausea | 0.76 | 0.04 | |

| Baseline ESAS Sleep | 1.26 | 0.04 | |

| Baseline ESAS Anxiety | 1.11 | 0.51 | |

| Baseline ESAS Drowsiness | 1.02 | 0.87 | |

| Baseline ESAS Pain | 1.02 | 0.91 | |

| Anorexia | Gender | 0.55 | 0.21 |

| Marital Status | 0.85 | 0.71 | |

| Baseline ESAS Appetite | 1.23 | 0.01 | |

| Baseline FACIT-F Total Score | 1.00 | 0.91 | |

| Baseline FACT-G Fatigue subscale | 0.92 | 0.01 | |

| Baseline FACT-G Functional Well-being | 1.01 | 0.91 | |

| Baseline FACT-G Physical Well-being | 0.98 | 0.72 | |

| Baseline ESAS Fatigue | 0.90 | 0.53 | |

| Baseline ESAS Drowsiness | 1.04 | 0.66 | |

| Baseline Shortness of breath | 1.08 | 0.33 | |

| Baseline ESAS Sleep | 1.14 | 0.12 | |

| Baseline ESAS Well-being | 1.07 | 0.51 | |

| Nausea | Age | 0.97 | 0.33 |

| Educational Level | 2.73 | 0.05 | |

| Mini Mental Score | 1.72 | 0.19 | |

| Baseline FACIT-F Total Score | 1.00 | 0.80 | |

| Baseline FACT-G Physical Well-being | 1.11 | 0.50 | |

| Baseline ESAS Nausea | 2.10 | 0.004 | |

| Baseline ESAS Anxiety | 0.97 | 0.85 | |

| Baseline ESAS Shortness of breath | 1.02 | 0.84 | |

Reporting of other side effects such as slurred speech, vertigo, and skin problems were not significantly associated with any of the variables tested for nocebo effect.

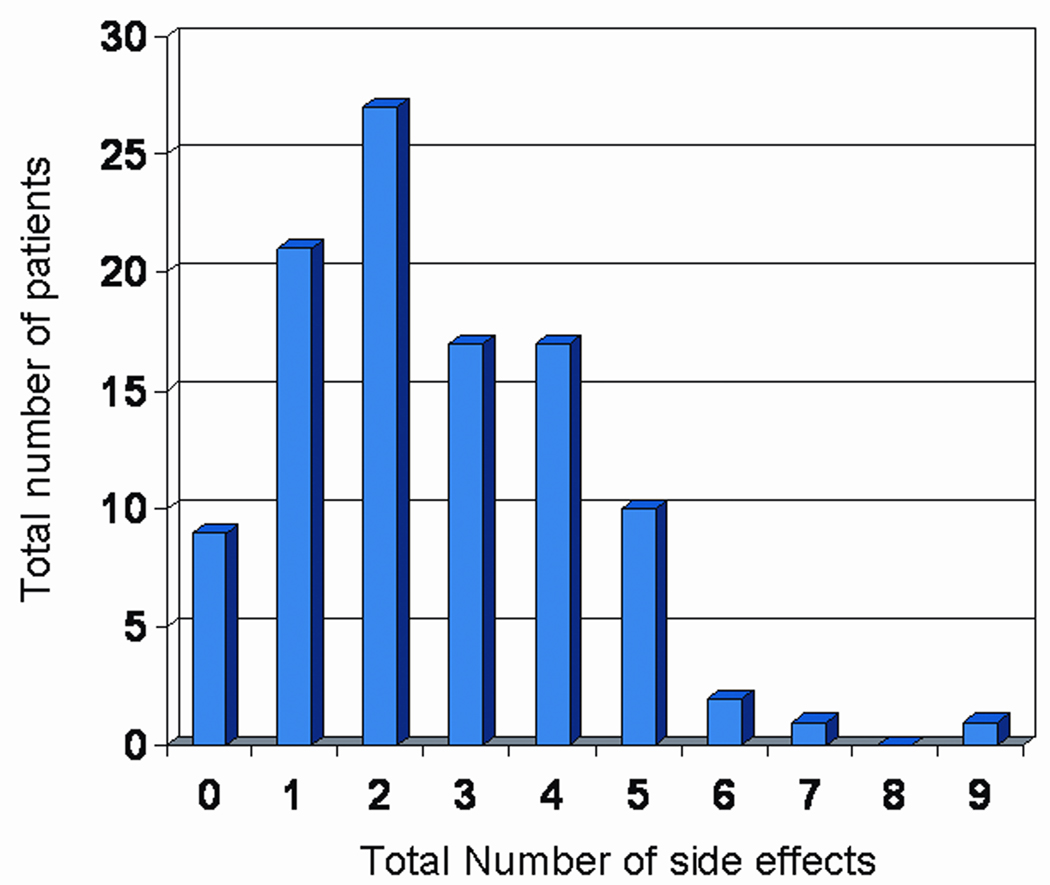

96 (91%) of patients reported at least one side effect to the placebo drug. Using the cut-off of 2 as a basis of grouping those with nocebo effect and those that do not have, we found that 30 (29%) of patients were considered to have no nocebo effect and 75 (71%) patients reported nocebo effects. Worse baseline pain (p=0.05), drowsiness (p=0.05), and sleep (p=0.03) were associated with nocebo effect. Multivariate analysis showed that patients with worse baseline sleep were more likely to report more side effects (OR=1.20, p=0.021), The frequency of reported side effects is illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Frequency of reported side effects in patients who received placebo.

Discussion

More than half of the patients in this study responded to placebo. Earlier studies by Beecher et al. showed placebo effects in about 35% of patients and Brown reported that placebo effect occurred in around 30–40% of patients.13, 19 It has been suggested that the nature of the disorder or symptom influences whether a placebo effect occurs and that subjective symptoms such as pain, anxiety, and depression are more amenable to placebo effects than are more objective measures such as blood pressure.20 It is not surprising, then, that a subjective symptom such as fatigue, can be influenced by the placebo effect.

The mechanisms underlying the placebo effect is not fully understood. One proposed mechanism involves the brain’s reward circuitry. On the basis of findings from studies on pain and Parkinson’s disease, it has been hypothesized that expectations of reward or clinical improvement and great desire for effect play a critical role in the placebo effect.10, 21, 22 This may in part explain why there was a significant association in our current study between worse baseline FACT-G physical well-being score and placebo response. Patients with worse baseline fatigue may have had greater desire for effect and might also have increased expectations of improvement given their higher symptom burden. Unfortunately, we did not measure patients’ expectation and this should be done in future research. Another possible explanation for the observed placebo effect in this group of patients may be related to the concept of regression to the mean where the measured change could be secondary to non-systematic variations.

Although some patients were on medications that can affect fatigue such as chemotherapy or anti-depressants, they were on stable doses during the duration of the study. We therefore believe, that their potential to confound our findings are not significant, particularly in these short-term 7 days studies.

The concept of a direct relationship between expectation of a desired effect and the actual occurrence of such an effect has been supported by other studies. Linde et al reported that in 864 patients who received acupuncture for the treatment of pain, improvement was significantly associated with high expectations of treatment effect.23 In a study of 26 pre-menopausal women with irritable bowel disease, investigators concluded that placebo analgesia was associated with increased expectations of pain relief and decrease in negative emotions such as anxiety.9 Other authors have shown this same relationship for other conditions.11, 24, 25

Kaptchuk et al reported that there were specific personalities that respond to placebo interventions.26 In earlier studies by the pain placebo pioneer team of Lasagna and Beecher, the investigators reported that only 13 of 93 patients who received placebo twice and reported therapeutic response were reliable placebo responders and that these 13 patients were more anxious, more self-centered, and had more baseline somatic complaints than patients who were non-responders or inconsistent placebo responders.27 Our study findings that patients with higher baseline ESAS anxiety were more likely to respond to placebo are consistent with those reports.

Other characteristics that were previously shown to contribute to placebo response such as gender and age were not observed in this study.28–30 As pointed out by previous investigators, the variables reported in different disease conditions are very difficult to replicate, not generalizable and inconsistent.31, 32 It could be that these factors would only be contributory to other conditions and not for fatigue. Hyland reported that most variables are related to symptoms and disease characteristics and not patient characteristics.33, 34

The nocebo effect is even less understood than the placebo effect but is thought to be related, like the placebo effect to some neurobiological mechanism involving negative expectations about treatment outcome, expectations of harm, worsening or vulnerability,14 prior conditioning as by previous untoward experience such as adverse reactions to drugs or interventions,35 and certain psychological characteristics.

Nearly a quarter of patients taking a placebo experience side effects.36 Rosenweig et al reported that 19% of healthy volunteers taking placebo reported side effects.37 Pogge reported in a review of 67 placebo-controlled trials, that at least 23% of patients who received a placebo reported at least one side effect.38 In our study, 91% of the patients reported at least one side effect from a placebo drug, and 71% of patients were considered to have nocebo effect. It is likely that the higher frequency reported in our study as compared with other studies can be explained by negative expectations and symptoms that were already reported to be present even prior to treatment. Providing a list of all the potential side effects of the active drug may have created a negative expectation of treatment outcome and harm. It has been shown for example, that negative expectations result in the amplification of the pain being reported.10 The list of side effects may have conditioned the patient to expect these to develop over the course of the trial.

To our knowledge, there are no reports in the literature of specific patient characteristics associated with the nocebo effect. Some investigators reported that people who tend to be anxious, to be depressed are more at risk of developing nocebo effect in response to attempts at treatment. 35 Our study showed that patients with anxiety were more likely to report restlessness and that those with depression were more likely to report more tachycardia. These findings suggests, as has been reported in previous studies that the nocebo effect is related to somatization whereby the patient expresses emotional distress as physical symptoms.

We found interesting results for those patients who reported nocebo effect. Patients who had insomnia at baseline were more likely to report more nocebo effect. We speculate that if patients did not feel particularly well at baseline, they were much more likely to express their symptoms as a side effect.

Many commonly reported nocebo effects in patients taking placebo are more generalized such as: nausea, fatigue, drowsiness and insomnia.31 These were observed in our patients as well, with insomnia being the most frequently reported, followed by anorexia, nausea and restlessness. What was of interest was that, patients had reported some of these as symptoms (insomnia, anorexia and nausea) in their baseline ESAS assessment. It would seem that patients were misattributing these symptoms as nocebo effects rather than as resulting from the underlying disease. This has been described previously for pain by Turner et al.31 More research is needed to test this hypothesis.

Our hypothesis that patient’s expectations of outcome, whether positive or negative, are associated with either the placebo and nocebo effect needs to be interpreted cautiously due to the retrospective nature of the study. Future research is needed to test this hypothesis. Second, our study consisted of a very small cohort of patients and future studies, with larger patient population are needed to confirm our findings.

Previous authors described placebo side effects which are side effects attributed to taking the placebo drug and is not considered a nocebo effect.14 In the case of the nocebo effect, there is a negative expectation associated with the reporting of side effects. In the context of clinical trials, as was in the two trials that we have analyzed, when potential side effects to the active drug are enumerated to the patient, negative expectations can occur.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to specifically look at placebo and nocebo in CRF. We found that a good proportion of patients experienced placebo effect and an even greater proportion reported nocebo effects. The implications of these findings are important in the context of research and treatment. Clinical trials on CRF should take into consideration placebo and nocebo effect when designing clinical trials. When patients randomized to placebo demonstrate substantial clinical response, it would be difficult for patients that received the treatment drug to show an even greater response.39, 40 Failure to consider the placebo effect may explain why previous trials have failed to demonstrate significant therapeutic effects of drugs over placebo. Strategies in research design aimed at perhaps minimizing the placebo effect, such as a bigger sample size, longer trial period, are needed to more effectively evaluate the real effect of treatment. Our observation of a nocebo effect, further justifies use of a placebo in clinical trials as it permits better appraisal of side effects of active drug. Researchers need to recognize that the nocebo phenomenon exists. Our findings on the nocebo effect, also raises the question of about disclosures of potential side effects in the daily clinical setting. If negative expectations can influence reporting of adverse events, how then should we inform our patients about the possibility of side effects without causing harm or suffering?

With increasing interest in and better understanding of the placebo and nocebo phenomena, supportive therapy along with pharmacologic intervention aimed to maximize treatment benefit may be more incorporated in routine patient care.

Conclusion

More than half of advanced cancer patients enrolled in the fatigue trials responded to placebo. Worse baseline physical well-being score was associated with placebo response. Patients experiencing specific symptoms at baseline were more likely to report these as side effects of the medication. These findings should be considered in the design of future clinical trials of treatments of CRF.

Acknowledgments

Sources of support: Eduardo Bruera is supported in part by National Institutes of Health grant numbers R01NR010162-01A1, R01CA1222292-01, and R01CA124481-01. David Hui is funded by a fellowship from the Clinician Investigator Program, Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada.

Footnotes

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.NCCN. Cancer Related Fatigue. In: Network NCC, editor. Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bruera E, Neumann C, Brenneis C, Quan H. Frequency of symptom distress and poor prognostic indicators in palliative cancer patients admitted to a tertiary palliative care unit, hospices, and acute care hospitals. J Palliat Care. 2000;16(3):16–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vogelzang NJ, Breitbart W, Cella D, Curt GA, Groopman JE, Horning SJ, et al. Patient, caregiver, and oncologist perceptions of cancer-related fatigue: results of a tripart assessment survey. The Fatigue Coalition. Semin Hematol. 1997;34(3 Suppl 2):4–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cella D, Davis K, Breitbart W, Curt G. Cancer-related fatigue: prevalence of proposed diagnostic criteria in a United States sample of cancer survivors. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19(14):3385–3391. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.14.3385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lawrence DP, Kupelnick B, Miller K, Devine D, Lau J. Evidence report on the occurrence, assessment, and treatment of fatigue in cancer patients. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2004;(32):40–50. doi: 10.1093/jncimonographs/lgh027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cella D, Peterman A, Passik S, Jacobsen P, Breitbart W. Progress toward guidelines for the management of fatigue. Oncology (Williston Park) 1998;12(11A):369–377. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bruera E, Valero V, Driver L, Shen L, Willey J, Zhang T, et al. Patient-controlled methylphenidate for cancer fatigue: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(13):2073–2078. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.02.8506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bruera E, El Osta B, Valero V, Driver LC, Pei BL, Shen L, et al. Donepezil for cancer fatigue: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(23):3475–3481. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.10.9231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vase L, Robinson ME, Verne GN, Price DD. Increased placebo analgesia over time in irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) patients is associated with desire and expectation but not endogenous opioid mechanisms. Pain. 2005;115(3):338–347. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2005.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vase L, Robinson ME, Verne GN, Price DD. The contributions of suggestion, desire, and expectation to placebo effects in irritable bowel syndrome patients. An empirical investigation. Pain. 2003;105(1–2):17–25. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(03)00073-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pollo A, Amanzio M, Arslanian A, Casadio C, Maggi G, Benedetti F. Response expectancies in placebo analgesia and their clinical relevance. Pain. 2001;93(1):77–84. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(01)00296-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pollo A, Torre E, Lopiano L, Rizzone M, Lanotte M, Cavanna A, et al. Expectation modulates the response to subthalamic nucleus stimulation in Parkinsonian patients. Neuroreport. 2002;13(11):1383–1386. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200208070-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brown WA. The placebo effect. Sci Am. 1998;278(1):90–95. doi: 10.1038/scientificamerican0198-90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hahn RA. The nocebo phenomenon: concept, evidence, and implications for public health. Prev Med. 1997;26(5 Pt 1):607–611. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1996.0124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bruera E, Kuehn N, Miller MJ, Selmser P, Macmillan K. The Edmonton Symptom Assessment System (ESAS): a simple method for the assessment of palliative care patients. J Palliat Care. 1991;7(2):6–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cella D. The Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Anemia (FACT-An) Scale: a new tool for the assessment of outcomes in cancer anemia and fatigue. Semin Hematol. 1997;34(3 Suppl 2):13–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. "Mini-mental state". A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12(3):189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chang VT, Hwang SS, Feuerman M. Validation of the Edmonton Symptom Assessment Scale. Cancer. 2000;88(9):2164–2171. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(20000501)88:9<2164::aid-cncr24>3.0.co;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Beecher HK. The powerful placebo. J Am Med Assoc. 1955;159(17):1602–1606. doi: 10.1001/jama.1955.02960340022006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hrobjartsson A, Gotzsche PC. Is the placebo powerless? An analysis of clinical trials comparing placebo with no treatment. N Engl J Med. 2001;344(21):1594–1602. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200105243442106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Colloca L, Benedetti F. How prior experience shapes placebo analgesia. Pain. 2006;124(1–2):126–133. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2006.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Colloca L, Sigaudo M, Benedetti F. The role of learning in nocebo and placebo effects. Pain. 2008;136(1–2):211–218. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2008.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Linde K, Witt CM, Streng A, Weidenhammer W, Wagenpfeil S, Brinkhaus B, et al. The impact of patient expectations on outcomes in four randomized controlled trials of acupuncture in patients with chronic pain. Pain. 2007;128(3):264–271. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2006.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McRae C, Cherin E, Yamazaki TG, Diem G, Vo AH, Russell D, et al. Effects of perceived treatment on quality of life and medical outcomes in a double-blind placebo surgery trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61(4):412–420. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.4.412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Benedetti F, Mayberg HS, Wager TD, Stohler CS, Zubieta JK. Neurobiological mechanisms of the placebo effect. J Neurosci. 2005;25(45):10390–10402. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3458-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kaptchuk TJ, Kelley JM, Deykin A, Wayne PM, Lasagna LC, Epstein IO, et al. Do "placebo responders" exist? Contemp Clin Trials. 2008;29(4):587–595. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2008.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lasagna L, Beecher HK. The analgesic effectiveness of nalorphine and nalorphine-morphine combinations in man. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1954;112(3):356–363. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Averbuch M, Katzper M. Gender and the placebo analgesic effect in acute pain. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2001;70(3):287–291. doi: 10.1067/mcp.2001.118366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rheims S, Cucherat M, Arzimanoglou A, Ryvlin P. Greater response to placebo in children than in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis in drug-resistant partial epilepsy. PLoS Med. 2008;5(8):e166. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0050166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lewis DW, Winner P, Wasiewski W. The placebo responder rate in children and adolescents. Headache. 2005;45(3):232–239. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2005.05050.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Turner JA, Deyo RA, Loeser JD, Von Korff M, Fordyce WE. The importance of placebo effects in pain treatment and research. Jama. 1994;271(20):1609–1614. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Talley NJ, Locke GR, Lahr BD, Zinsmeister AR, Cohard-Radice M, D'Elia TV, et al. Predictors of the placebo response in functional dyspepsia. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2006;23(7):923–936. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2006.02845.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hyland ME, Whalley B, Geraghty AW. Dispositional predictors of placebo responding: a motivational interpretation of flower essence and gratitude therapy. J Psychosom Res. 2007;62(3):331–340. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2006.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Whalley B, Hyland ME, Kirsch I. Consistency of the placebo effect. J Psychosom Res. 2008;64(5):537–541. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2007.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Barsky AJ, Saintfort R, Rogers MP, Borus JF. Nonspecific medication side effects and the nocebo phenomenon. Jama. 2002;287(5):622–627. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.5.622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shepherd M. The placebo: from specificity to the non-specific and back. Psychol Med. 1993;23(3):569–578. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700025356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rosenzweig P, Brohier S, Zipfel A. The placebo effect in healthy volunteers: influence of experimental conditions on the adverse events profile during phase I studies. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1993;54(5):578–583. doi: 10.1038/clpt.1993.190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pogge RC. The toxic placebo. I. Side and toxic effects reported during the administration of placebo medicine. Med Times. 1963;91:773–778. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Price DD, Milling LS, Kirsch I, Duff A, Montgomery GH, Nicholls SS. An analysis of factors that contribute to the magnitude of placebo analgesia in an experimental paradigm. Pain. 1999;83(2):147–156. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(99)00081-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Montgomery SA. The failure of placebo-controlled studies. ECNP Consensus Meeting, September 13, 1997, Vienna. European College of Neuropsychopharmacology. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 1999;9(3):271–276. doi: 10.1016/s0924-977x(98)00050-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]