Abstract

Amylin is a member of calcitonin or calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) family. Immunohistochemical study revealed a dense network of amylin-immunoreactive (irAMY) cell processes in the superficial dorsal horn of the mice. Numerous dorsal root ganglion and trigeminal ganglion cells expressed moderate to strong irAMY. Reverse transcriptase- polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) revealed amylin receptor mRNA in the mouse spinal cord, brain stem, cortex, hypothalamus and hippocampus. The nociceptive or antinociceptive effects of amylin were evaluated in the acetic acid-induced writhing test. Amylin (0.1, 0.5 and 1 mg/kg, i.p. or 1-10 μg, i.t.) reduced the number of writhes in a dose-dependent manner. Pretreatment of the mice with the amylin receptor antagonist salmon calcitonin (8-32), either by i.p. or i.t., antagonized the effect of amylin on acetic acid-induced writhing test. Locomotor activity was not significantly modified by amylin injected either i.p. (0.01-1 mg/kg) or i.t. (1-10 μg). Measurement of c-fos mRNA by RT-PCR or proteins by Western blot showed that the levels were up-regulated in the spinal cord of mice injected with acetic acid and the increase was attenuated by pretreatment with amylin (10 μg, i.t.). Collectively, our result demonstrates that irAMY is expressed in dorsal root ganglion neurons with their cell processes projecting to the superficial layers of the dorsal horn, and that the peptide by interacting with amylin receptors in the spinal cord may be antinociceptive.

Keywords: antinociception, dorsal root ganglia, intrathecal, c-fos, amylin receptor

Introduction

Amylin, a 37 amino acid peptide secreted from pancreatic β-cells upon stimulation by meal or glucose (Cooper et al., 1987; Westermark et al., 1987), is a member of the calcitonin family which includes calcitonin (CT), calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) and adrenomedullin (AM) (Muff et al., 2004). Amylin-like immunoreactivity (irAMY) has been reported in the gut (Mulder et al., 1994), osteoblast (Gilbey et al., 1991) and central nervous system of humans and rats (Skofitsch et al., 1995; D'Este et al., 2000). Amylin is abundantly expressed in rat dorsal root ganglion cells, some of which contain substance P and pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide (Mulder et al., 1995). Further, irAMY and CGRP-immunoreactivity overlaps in the motor nuclei of the hindbrain and spinal cord (Skofitsch et al., 1995; Gebre-Medhin et al., 1998).

Amylin is structurally similar to both salmon CT (sCT, about 30% homology) and CGRP (about 50% homology) (van Rossum et al., 1997). Similar to CGRP receptors, amylin receptors are heterodimeric complex of calcitonin receptor (CTR) and receptor activity modifying proteins (RAMP) (Christopoulos et al., 1999). High affinity amylin binding sites are located in many regions of the rat and monkey brains; including the hypothalamus, nucleus accumbens, dorsal raphe and area postrema (Stridsberg et al., 1993; Sexton et al., 1994; Paxinos et al., 2004). Little is known relative to the function of amylin in the mammalian nervous system. Amylin has been proposed as an anorexigen affecting the gastrointestinal system and ingestive behavior (Riediger et al., 2001;Young, 2005; Edelman et al., 2008). The peptide has also been shown to exert anti-inflammatory activity (Clementi et al., 1995) and protect gastric mucosa in various ulcer models (Samonina et al., 2004). Variable results have been reported relative to its involvement in nociception. For example, central administration of amylin failed to induce antinociception (Bouali et al., 1995; Sibilia et al., 2000), while peripheral administration (subcutaneous or intraperitoneal) produced antinociception (Young, 1997).

In the pain signaling pathways, the immediate early gene c-fos is promptly expressed in neurons in response to a painful stimulus (Sagar et al., 1988). Several reports have shown that the expression of c-fos mRNA or immunoreactivity is up-regulated in the spinal cord following noxious visceral stimulation (Rodella et al., 1998; de los Santos-Arteaga et al., 2003; Lee and Seo, 2008). In contrast, expression of c-fos in the spinal cord was attenuated by pretreatment of analgesia (Lee and Seo, 2008). Thus, expression of c-fos mRNA or protein can be used as a marker of neurons activated by pain sensation (Harris, 1998).

In this study, results from a multidisciplinary approach including immunohistochemistry, molecular biology and in vivo pharmacology, support the hypothesis that amylin is antinociceptive in an acetic acid-induced writhing mouse model.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Experimental Animals

Adult male ICR mice (Ace Animal Inc., Boyertown, PA) weighing 25-30g were used in this study. Experimental protocols were reviewed and approved by the Temple University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee, in accordance with the 1996 NIH Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. Animals were housed under a 12-h light/dark cycle with free access to food and water. Animals were moved to the behavioral testing room one day prior to testing and were acclimated in the observation box at least one hour before the experiments. Efforts were made to minimize the number of mice and animal suffering from pain-related studies.

Immunohistochemistry

Mice anesthetized with urethane (1.2 g/kg, i.p.) were intracardially perfused with cold 0.1 M phosphate buffered saline (PBS) followed by freshly prepared 4% paraformaldehyde/0.2% picric acid in PBS. Tissue were processed for amylin-immunoreactivity (irAMY) by the avidin-biotin complex procedure (Dun et al., 2006). Sections were incubated in amylin antiserum (1:3000 dilution, a rabbit polyclonal against feline amylin; Phoenix Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Burlingame, CA) for 48 hrs. Sections were then incubated in biotinylated anti-rabbit IgG (1:300 dilution, Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) for 2 hr, and rinsed with PBS and incubated in avidin-biotin complex solution for 1.5 hr (1:100 dilution, Vector Laboratories). Following several washes in Tris-buffered saline, sections were developed in 0.05% diaminobenzidine/0.001% H2O2 solution and washed for at least 2 hr with Tris-buffered saline. Sections were mounted on slides with 0.25% gel alcohol, air-dried, dehydrated with absolute alcohol followed by xylene, and coverslipped with Permount.

In the control study, several sections of dorsal root ganglion or spinal cord from each animal were incubated in amylin antiserum pre-absorbed with amylin peptide (1 μg/ml, Phoenix Pharmaceuticals, Inc.) overnight. Quantification of irAMY neurons in DRG was conducted using the image analysis software (ImageJ 1.41o, Wayne Rasband, NIH). Images were captured at ×40 magnification. One hundred neuron profiles were measured from five DRG sections. Each irAMY neuron was sorted into six groups according to their diameters (1-20, 20-25, 25-30, 30-35, 35-40 or >40 μm) and expressed as a percentage of 100 neurons.

Acetic acid-induced writhing test

Procedures for acetic acid-induced writhing test are described in detail (Collier et al., 1968). Amylin (0.03, 0.1, 0.5 or 1 mg/kg) or vehicle was injected i.p.15 min before an i.p. injection of acetic acid (0.6%, 0.3 ml/30 g). The number of writhes was counted between 5 and 15 min after the last injection. For the antagonist experiment, sCT [8-32] (0.5 mg/kg) or vehicle was injected i.p.15 min before the administration of amylin (0.1 mg/kg). Acetic acid tests were conducted 15 min after the injection of amylin. Intrathecal administration of amylin (0.3, 1, 5 or 10 μg/mouse) or vehicle was given 10 min before an i.p. injection of acetic acid (0.6%, 0.3 ml/30 g). sCT [8-32] (5 μg/mouse, i.t.) was given 10 min before amylin (5 μg/mouse, i.t.) and acetic acid or acetic acid alone.

Locomotor activity test

Locomotor activity of the mice was measured by a computerized monitoring system (Digiscan DMicro, Accuscan Inst, Columbus, OH), which consists of a metal frame containing 16 parallel infrared photobeams and receivers into which a standard plastic cage (42 × 20 × 20 cm) was placed. Photobeam breaks were recorded as total activity (TACTV) and stored on a computer coupled to the activity monitors. Groups of mice were tested for 10 min before and 50 min post i.p. injection (vehicle, amylin 0.01, 0.1 or 1 mg/kg) or 45 min post i.t. injection (vehicle, amylin 1, 5 or 10 μg/mouse). TACTV was determined by the number of times the animal broke the light beams and used for statistical analysis.

CTR and RAMP mRNA analysis by RT-PCR

Mice anesthetized with urethane (1.2 g/kg, i.p.) were decapitated with guillotine and various brain regions were dissected out. Total RNA was extracted using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. First-strand cDNA was synthesized using SuperScript II first-strand synthesis system for RT-PCR (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). PCR was performed with a 5′ primer (TGGTTGAGGTTGTGCCCAATGGA) and a 3′ primer (CTCGTGGGTTTGCCTCATC TTGGTC) for CTR (Wang et al., 1998), and a 5′ primer (TCGTACCACAGGCATTGTGATGGA) and a 3′ primer (ACTCCTGCTTGCTGATCCACATCT) for β-actin under the following conditions: 95°C for 2 min; 40 cycles at 95°C for 30 sec, 62°C for 30 sec and 72°C for 1 min; and then 72°C for 10 min (CTR); 94°C for 2 min; 29 cycles at 94°C for 30 sec, 55°C for 45 sec and 72°C for 1 min; and finally 72°C for 10 min (β-actin). The primers of CTR generated a product of 503bp from the CTRb mRNA, and a product of 392 bp from the CTRa mRNA (Wang et al., 1998). Similarly, primer sequences for RAMP1 with a 5′ primer (AGGACTTGAGAGTGGCTCTGCATT) and a 3′ primer (ATGCTGTCACTACTGTCC ATGGCT) and the conditions: 94°C for 2 min; 38 cycles at 94°C for 30 sec, 55°C for 45 sec and 72°C for 1 min; and finally 72°C for 10 min. Primer sequences for RAMP3 with a 5′ primer (TCATCACTGGAATCCA CAGGCAGT) and a 3′ primer (GTGGCCAAAGCAAACCAGACAGAA) and the conditions: 94°C for 2 min; 37 cycles at 94°C for 30 sec, 55°C for 45 sec and 72°C for 45 sec; and finally 72°C for 10 min. The amplified products were subjected to electrophoresis in a 1% agarose gel and stained with ethidium bromide. The image was acquired with a FujiFilm Las-1000 imaging system (FujiFilm Medical Systems, Stamford, CT). The digitized images were quantified with the Image Gauge software (FujiFilm Medical Systems, Stamford, CT).

c-fos mRNA analysis by RT-PCR

Mice anesthetized with urethane (1.2 g/kg, i.p.) were decapitated with guillotine and spinal cords were dissected out 30-40 min after writhing test. Total RNA was extracted using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. First-strand cDNA was synthesized using SuperScript II first-strand synthesis system for RT-PCR (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). PCR was performed with a 5′ primer (AAACCGCATGGAGTGTGTTGTTCC) and a 3′ primer (TCAGACCACCTCGACAATGCATGA) for c-fos, and a 5′ primer (TCGTACCACAGGCATT GTGATGGA) and a 3′ primer (ACTCCTGCTTGCTGATCCACATCT) for β-actin under the following conditions: 94°C for 2 min; 30 cycles at 94°C for 30 sec, 55°C for 45 sec and 72°C for 45 sec; and finally 72°C for 10 min (c-fos); 94°C for 2 min; 29 cycles at 94°C for 30 sec, 55°C for 45 sec and 72°C for 1 min; and finally 72°C for 10 min (β-actin). The amplified products were subjected to electrophoresis in a 1% agarose gel and stained with ethidium bromide. The image was acquired with a FujiFilm Las-1000 imaging system (FujiFilm Medical Systems, Stamford, CT). The digitized images were quantified with the Image Gauge software (FujiFilm Medical Systems, Stamford, CT). Three groups of mice were analyzed as follows: vehicle, vehicle with acetic acid, and amylin (10 μg /mouse, i.t.) with acetic acid (n=6).

c-fos analysis by Western blot

Three groups of mice were analyzed in this series of experiments: vehicle, vehicle with acetic acid, and amylin (10 μg /mouse, i.t.) with acetic acid (n=6). Fresh-frozen spinal cord samples were obtained 2 h after writhing test and immediately stored at −80°C. Samples of approximately 100mg were lysed in ice-cold lysis buffer [10mM Tris pH 7.6, 1% Triton X-100, protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche Diagnostics, Manheim, Germany)], and protein concentrations were determined following the standard protocols of Bradford method (BioRad, Hercules, CA). Equal amount of protein (50μg) of each sample was loaded per well onto a 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gel, separated and transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane, which was incubated over night with rabbit polyclonal anti-c-fos antiserum (1:1000 dilution; Sigma-Aldrich Inc., St. Louis, MO). The secondary antibody used (1:2500 dilution) was a HRP-conjugated anti-rabbit (Affinity BioReagents, Rockford, IL, USA). The signal was detected by chemiluminescence reagent (Super Signal West Pico Kit, Pierce, IL, USA). The image was acquired with a FujiFilm Las-1000 imaging system (FujiFilm Medical Systems, Stamford, CT). The digitized images were quantified with the Image Gauge software (FujiFilm Medical Systems, Stamford, CT).

Chemicals

Amylin (Feline), salmon calcitonin [8-32] (sCT [8-32]) was purchased from Phoenix Pharmaceuticals, Inc. Amylin was dissolved in 10% DMSO as stock solution (10 mg/ml) and diluted with vehicle (0.9 % saline) immediately before administration. sCT [8-32] (4mg/ml) was dissolved in deionized water and frozen until use. The peptide was thawed and diluted with saline immediately before use. Pharmacological agents were delivered intraperitoneally (i.p.) or intrathecally (i.t.).

Statistical analyses

Results are expressed as mean ± SEM of the measurements from a group of six to eight mice. For writhing test, the number of abdominal constrictions in each test period was normalized to the mean calculated from the control (vehicle) group as percent inhibition of writhing (% inhibition): (Tomizawa et al., 2001). Statistical analysis was performed with GraphPad Prism program (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA). Differences among multiple groups were determined by one or two way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by post-hoc Bonferroni test. Differences between two groups were determined by the Student t test. Statistical significance was set at P<0.05.

RESULTS

irAMY in the spinal cord and sensory ganglia

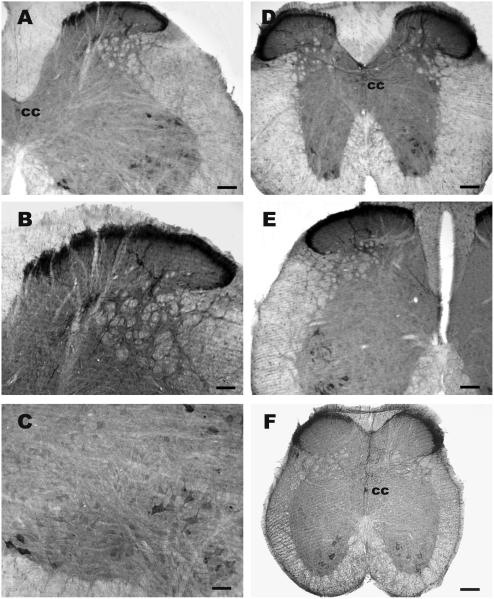

Examination of tissue sections prepared from the spinal cord of six mice showed that irAMY is conspicuously expressed in two regions: the superficial dorsal horn and ventral horn (Fig.1). A dense plexus of irAMY fibers was observed in laminae I and II of the dorsal horn in all levels of the spinal cord including cervical, thoracic, lumbar and sacral sections (Fig. 1A, B, D, E and F). Some of the ventral horn neurons, particularly those in the dorsolateral and ventromedial nuclei, were irAMY (Fig. 1A, C, D, E and F).

Fig 1.

Mouse cervical, thoracic, lumbar and sacral spinal sections labeled with amylin antiserum. A, D, E and F, a cervical, thoracic, lumbar and sacral spinal section, where a dense plexus of amylin-immunoreactive fibers is observed in the lamina I of the dorsal horn, and some of the ventral horn neurons are labeled. B, a higher magnification of A, where numerous irAMY fibers are noted in the superficial layer of the dorsal horn; some of the fibers extend down to deeper layers. C, a higher magnification of section A, where irAMY is observed in several ventral horn neurons; cc, central canal. Scale bar: A, D, E and F, 250 μm; B,100 μm; C, 50 μm.

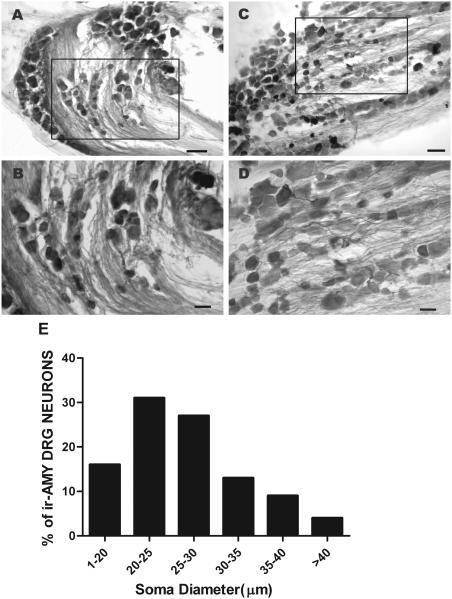

With respect to the sensory ganglia, a moderate to intense irAMY was detected in a large population of dorsal root ganglion (DRG) cells (Fig. 2A and B) and trigeminal ganglion cells (TRG) (Fig. 2C and D). The majority of irAMY DRG neurons were small to medium and a small percentage of cells were large (Fig. 2E). Quantitative analysis shows that 87% of irAMY neurons were within the range of small (<25μm) to medium size (<35 μm, Fig. 2E).

Fig. 2.

Sections of mouse dorsal root ganglion (DRG) and trigeminal ganglion (TRG) labeled with amylin antiserum. A and B, lower and higher magnification of a DRG section, where irAMY is strongly expressed in some of the ganglion cells. C and D, lower and higher magnification of a TRG section, where irAMY is strongly expressed in some of the cells. E, cell diameter-frequency distribution histogram reveals that 87% of irAMY neurons are within the range of small (<25 μm in soma diameter) to medium (25-35 μm in soma diameter) neurons. Scale bar: A and C, 100 μm; B and D, 50 μm.

In the control experiments, irAMY was not detected in any spinal cord or dorsal root ganglion sections processed with amylin antiserum pre-absorbed with the peptide (1 μg/ml) overnight.

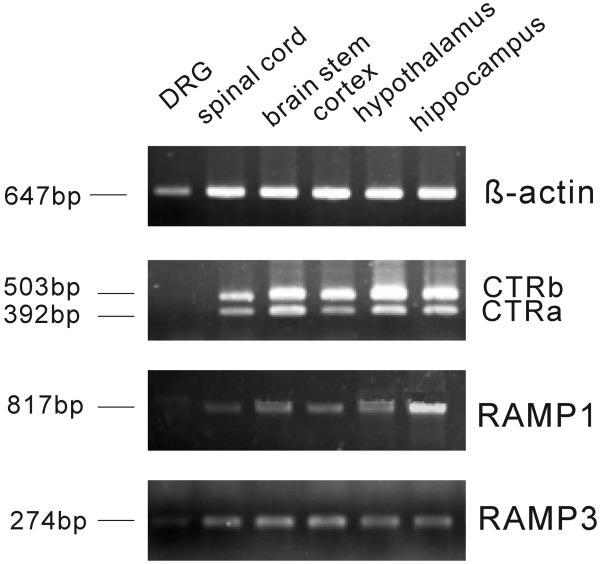

Expression of CTR and RAMPs mRNA in brain

Amylin receptors are heterodimers consisting of CTR and RAMPs. There are two forms of CTR: CTRa and CTRb. RAMPs comprise of three members designated RAMP 1, 2 and 3. In the proposed amylin receptor subtypes, two appear to predominate: CTRa dimerizes with RAMP1 to form amylin receptor 1 or with RAMP3 to form amylin receptor 3 (Young, 2005). Here, RT-PCR results showed that both CTRa and CTRb mRNA are expressed in the following mouse brain regions: spinal cord, brain stem, cortex, hypothalamus and hippocampus; whereas, expression was not detected in the DRG (Fig. 3). Expression of RAMP1 and RAMP3 mRNAs was detected in all regions studied; although RAMP1 expression was barely detectable in the DRG, and RAMP3 was low in the DRG (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Expression of CTRa, CTRb, RAMP1 or RAMP3 mRNA in the brains. Basal expression of CTRa (392bp), CTRb (503bp), RAMP1 (817bp) and RAMP3 (274bp) mRNA in mice DRG, spinal cord, brain stem, cortex, hypothalamus and hippocampus. β-actin mRNA (647 bp) serves as control. (n=3).

Effects of amylin on pain

When administered intraperitoneally (i.p.) 15 min before acetic acid challenge, amylin (0.1 mg/kg) significantly reduced the number of writhes per 10-min period 5 min after acetic acid challenge as compared to the vehicle group (P<0.001). For this reason, the 15-min time-point was chosen and applied to all the remaining studies. Amylin in the doses of 0.03, 0.1, 0.5 and 1mg/kg, inhibited acetic acid-induced writhing by 13.38±3.54%, 43.55±4.62%, 22.14±5.87% and 27.98±4.68% (Fig. 4A). Amylin produced a significant antinociceptive effect at the medium dose of 0.1 mg/kg (P<0.001) or higher doses of 0.5 (P<0.05) and 1 mg/kg (P<0.01); but not the lower dose of 0.03 mg/kg (P>0.05). Hence, the dose of 0.1 mg/kg was selected in the next series of studies. Pretreating the mice with the amylin receptor antagonist sCT [8-32] (0.5mg/kg) 15-min before administration of amylin (0.1 mg/kg) significantly lowered the antinociceptive effect of amylin, as compared to the amylin injected group (P<0.05, 39±3.36 vs. 29±2.37). sCT [8-32] alone did not reduce the number of writhes to a significant level as compared to the vehicle group (P>0.05, 55±5.82 vs. 51±2.43).

Fig. 4.

Effects of amylin on writhing reflex. A, dose-response of amylin on writhing test.; vehicle or amylin (0.03, 0.1, 0.5 or 1 mg/kg) given i.p. 15 min before 0.6% acetic acid injection. B, dose-response of amylin on writhing test; vehicle or amylin (0.3, 1, 5 or 10 μg) given i.t. 10 min before 0.6% acetic acid injection. * indicates significant antinociception compared to vehicle group (P<0.05), ** P<0.01 and *** P<0.001. (n=8-10).

Similarly, intrathecal (i.t.) administration of amylin decreased dose-dependently the number of writhes caused by acetic acid (Fig. 4B). Amylin at the minimal effective dose of 1 μg significantly inhibited writhing reflexes to 42.36 ±11.18%. At the higher doses of 5 and 10 μg, amylin reduced the number of writhes to 62.16 ± 11.48 (P<0.01) and 80.08 ± 8.17% (P<0.001). Amylin at the lowest dose (0.3 μg) did not produce a significant inhibition (29.95 ± 11.36%). For this reason, 5 μg amylin was selected in the study of the antagonist profile, and 10 μg was selected in c-fos experiments. sCT [8-32] (5 μg) significantly attenuated the inhibitory effect of amylin as compared to the amylin group (P<0.05, 36±4.36 vs.18±5.55), while it alone did not produce a significant antinociception compared to the vehicle group (P>0.05, 38±5.44 vs. 48±2.94).

Both the i.p. and i.t. methods of amylin administration reduced the writhing reflex induced by acetic acid to a significant level as compared to the vehicle groups. However, the minimal effective dose in decreasing writhing was 30-fold lower for i.t. administration (1 μg/mouse, equivalent to 0.03 mg/kg) than for i.p. administration (0.1 mg/kg). Further, amylin by intrathecal administration inhibited the writhing reflex up to 80%, while intraperitoneal injection only reduced to 43%.

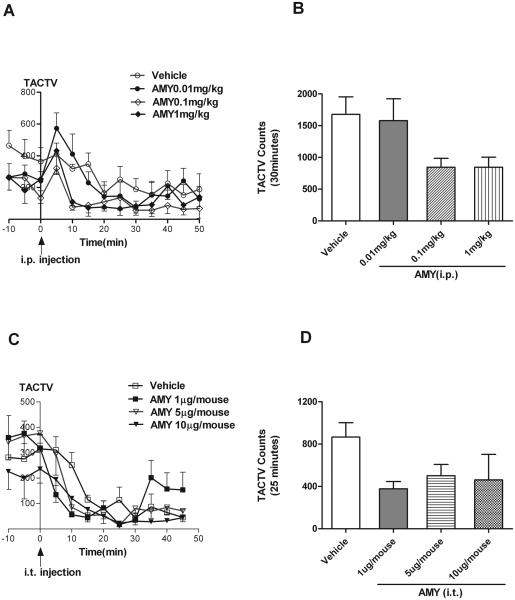

Locomotor activity

The antinociceptive effect of amylin might be a result of behavioral depression. For this reason, locomotor activity of mice pretreated with amylin was monitored. The time-course of activity 10 min prior to and 50 min post intraperitoneal injection of vehicle or 0.01-1 mg/kg AMY or 45 min post intrathecal administration of vehicle or 1-10 μg AMY was shown in Fig. 5. Two-way ANOVA and Bonferroni post-hoc comparison show that there was no significant difference between vehicle and treatment groups at every time-interval before or after administration (Fig. 5 A or C, P>0.05). Intraperitoneal administrations of vehicle or amylin caused a transient increase in TACTV (total activity) 5 min post injection in each group; whereas, the overall TACTV in 50-min period did not show any statistical significance among the vehicle and amylin treatment groups. Intrathecal administrations caused a transient decrease in TACTV within 10-min post injection, and remained stable for the remaining 35-min. It should be pointed out that the time frame of 0 to 30 min post i.p. injection or 0 to 25 min post i.t. injection was taken as the observation duration for writhing tests. In both methods of administration, no significant difference was seen between groups previously exposed to vehicle or amylin (Fig. 5B and D, vehicle vs. amylin; Bonferroni's Multiple Comparison test: P>0.05). Hence, there was no detectable change on locomotor activities in mice injected either peripherally or centrally with amylin.

Fig. 5.

Effects of amylin or vehicle on locomotor activity. A, effect of vehicle or amylin administered intraperitoneally at a dose of 0.01, 0.1 or 1 mg/kg on locomotor activity plotted as a function of time. C, effect of vehicle or amylin administered intrathecally at a dose of 1, 5 or 10 μg on locomotor activity plotted as a function of time. Cumulative dose response data are shown in B and D. (n=6-8). (TACTV: total activity.)

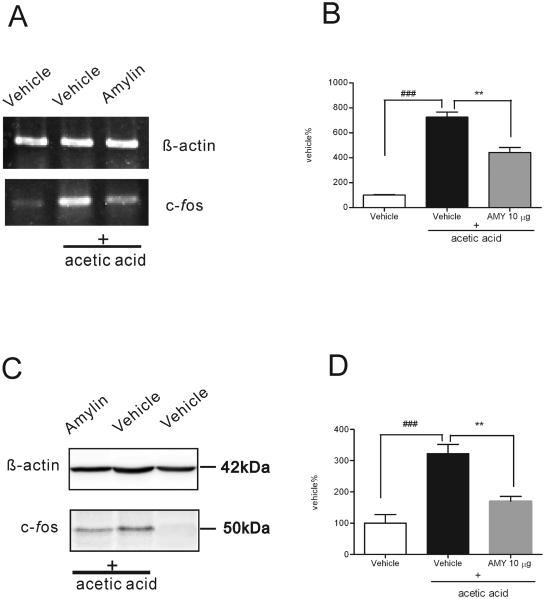

c-fos expression in spinal cord

Expression of c-fos mRNA and protein in spinal cords was consistently up-regulated after acetic acid challenge as compared to the vehicle-treated group (P<0.001, Fig. 6A and C), and the increase was attenuated by pretreatment with 10 μg amylin administered intrathecally (Fig. 6A and C). There was a significant reduction of c-fos expression at the mRNA and protein level (P<0.01),) in acetic acid/amylin-treated mice as compared to acetic acid/vehicle treated mice (Fig. 6B and D).

Fig. 6.

Effect of vehicle or amylin on c-fos expression in spinal cord after acetic acid injection. A, expression of c-fos mRNA (369 bp) in mouse spinal cord in vehicle alone, vehicle + acetic acid or 10 μg amylin (i.t.) + acetic acid (i.p. injection). β-actin mRNA (647 bp) serves as control. B, quantitation of c-fos mRNA from Fig. 6A (n=6). C, expression of c-fos in mouse spinal cord in vehicle alone, vehicle + acetic acid or 10 μg amylin (i.t.) + acetic acid (i.p. injection). β-actin served as control. D, quantitation of c-fos from Fig. 6C (n=6). ### indicate statistically significant (vehicle vs vehicle + acetic acid, P<0.001), ** indicate statistically significant (vehicle + acetic acid vs amylin + acetic acid, P<0.01).

DISCUSSION

Immunohistochemical result shows that amylin is expressed in the mouse spinal cord, DRG and TRG. This observation together with the finding that amylin receptor mRNA is detected in the spinal cord, brain stem, cortex, hypothalamus and hippocampus, raises the possibility that amylin may participate in neural signaling. In vivo experiments show that amylin injected intrathecally or intraperitoneally to mice reduced significantly the number of writhes in acetic acid challenge, but not locomotor activity. The antinociceptive effect of amylin is significantly reduced by the amylin receptor antagonist sCT[8-32] (Silvestre et al., 1996). Lastly, amylin by intrathecal administration decreases c-fos expression in the spinal cord following acetic acid challenge.

Several earlier reports show that irAMY is abundantly expressed in sensory neurons of the rat (Mulder et al., 1995; Skofitsch et al., 1995). Our immunohistochemical result reveals a similar pattern of expression of irAMY in the mouse; i.e., a large population of dorsal root and trigeminal ganglion cells with small to medium size, and in cell processes of superficial layers of the dorsal horn from all levels of the spinal cord. RT-PCR result shows that CTRs, RAMP 1 and RAMP 3 mRNA are expressed in the mouse spinal cord, brain stem, cortex, hypothalamus and hippocampus. While CTRs mRNA is not, RAMP 3 mRNA is detectable in the mouse DRG. Amylin receptor is a heterodimer of calcitonin receptor and RAMPs (Christopoulos et al., 1999). The amylin receptor is formed by a combination of CTR and RAMP in the above-mentioned neural tissues, except the DRG where CTR and RAMP1 mRNAs appear to be absent. Similarly, a study using in vitro autoradiography shows amylin binding sites in the hypothalamus, amygdala, accumbens nucleus, dorsal raphe and area postrema (Paxinos et al., 2004). RAMP 1-, 2- and 3-immunoreactive neurons are enriched in the spinal cord, especially in the laminae I and II layers of the spinal dorsal horn (Ma et al., 2006). Unlike CGRP which may act on pre-and post-synaptic receptors in the spinal cord, amylin receptors are not expressed in the DRG (Cottrell et al., 2005), implying that the major site of action of amylin is on the dorsal horn cells.

Two reports where amylin was found not to have a significant analgesic effect in an acute pain model (Bouali et al., 1995; Sibilia et al., 2000) prompted us to explore an antinociceptive effect of amylin in a visceral pain model. In the acetic acid writhing test, amylin exhibits antinociception in mice. The antinociceptive effect induced by intraperitoneal or intrathecal administration differs in terms of dose, efficacy and time course. A possible explanation for these apparent differences could be related to the route of administration. For example, amylin by intrathecal administration may act primarily in the spinal cord to inhibit writhing reflex; whereas, the response following intraperitoneal administration may reflect the sum of responses from different target sites (Olsson et al., 2007). Calcitonin receptors are located on certain serotoninergic neurons of the mouse brain including the raphe nuclei and the lateral paragigantocellular nucleus that are associated with pain processing (Nakamoto et al., 2000). Systemic injection of amylin increases the concentrations of serotonin (5-HT) in the hypothalamus (Chance et al., 1993), which may explain the peripheral antinociceptive effect of amylin. In our experiments, peripheral or central administration of amylin does not significantly change locomotor activity in a photocell-activated apparatus at doses ranging from 0.01 to 1 mg/kg (i.p.) or 1-10 μg (i.t.). Several studies showed that amylin reduces locomotor activity and exploratory behaviors (Bouali et al., 1995; Clementi et al., 1996; Baldo and Kelley, 2001). In these published studies, different time frames were employed for behavioral evaluations; either as short as 4-min (Clementi et al., 1996) or as long as 3-h, 6-h and 24-h after administration (Kovacs and Telegdy, 1996). Also, different injection sites, such as nucleus accumbens or intracerebroventricular, may activate amylin receptors located at different brain areas. Collectively, route of administration, doses and site of injection may contribute to the apparent discrepancy relative to the nociceptive or antinociceptive effect of amylin reported in earlier studies.

In the present study, sCT [8-32] by intraperitoneal or intrathecal administration suppressed amylin-induced antinociception. sCT [8-32] has been proposed as a potent amylin receptor antagonist; and it blocks amylin 1(a) and amylin 3(a) receptors (Silvestre et al., 1996; Young, 2005). Results from our study raise the possibility that the amylin receptor located on the spinal cord belongs to the amylin 1(a) and/or 3(a) receptor.

Lastly, it is clearly documented that c-fos expression is a valuable tool in pain research, especially in spinal nociceptive processes. de los Santos-Arteaga et al.(2003) reported an up-regulation of c-fos in dorsal spinal cord at the mRNA and protein level in the acetic acid writhing model. In our study, c-fos mRNA and proteins in the spinal cord are up-regulated under acetic acid challenge (P<0.001); and, it is decreased significantly following pre-treatment with amylin in comparison to the vehicle-treated group (P<0.01). This is the first report suggesting a spinal analgesic effect of amylin. Following peripheral noxious stimuli, spinal neurons that express c-fos are located in laminae I and II, and laminae V and VI of the dorsal horn (Harris, 1998). The distribution of irAMY fibers overlaps with the same regions of spinal cord expressing c-fos upon noxious stimulation. Alternatively, glutamate acting on NMDA receptors or substance P may trigger c-fos expression in the rat spinal cord (Sandkuhler et al., 1996; Badie-Mahdavi et al., 2001). Viewed in this context, amylin may inhibit c-fos expression in the dorsal horn cells by modulating the release of mediators such as glutamate and/or substance P.

To conclude, our study supports the hypothesis that amylin acting on amylin receptors 1 or 3 in the spinal cord is antinociceptive as assessed by the acetic acid writhing model.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

This work was supported by NIH Grants NS18710 and HL51314. The technical assistance of Mrs. Siok L. Dun and Dr. Xin Gao is gratefully acknowledged.

List of abbreviations

- AM

adrenomedullin

- irAMY

amylin-immunoreactive

- CT

calcitonin

- CTR

calcitonin receptor

- CGRP

calcitonin gene-related peptide

- cc

central canal

- DRG

dorsal root ganglion

- i.p.

intraperitoneally

- i.t.

intrathecally

- PACAP

pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide

- RAMP

receptor activity modifying protein

- RT-PCR

reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction

- sCT [8-32]

salmon calcitonin [8-32]

- SEM

standard error of the mean

- TACTV

total activity

- TRG

trigeminal ganglion.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- Badie-Mahdavi H, Worsley MA, Ackley MA, Asghar AU, Slack JR, King AE. A role for protein kinase intracellular messengers in substance P- and nociceptor afferent-mediated excitation and expression of the transcription factor Fos in rat dorsal horn neurons in vitro. Eur J Neurosci. 2001;14:426–434. doi: 10.1046/j.0953-816x.2001.01656.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldo BA, Kelley AE. Amylin infusion into rat nucleus accumbens potently depresses motor activity and ingestive behavior. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2001;281:R1232–1242. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.2001.281.4.R1232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouali SM, Wimalawansa SJ, Jolicoeur FB. In vivo central actions of rat amylin. Regul Pept. 1995;56:167–174. doi: 10.1016/0167-0115(95)00009-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chance WT, Balasubramaniam A, Stallion A, Fischer JE. Anorexia following the systemic injection of amylin. Brain Res. 1993;607:185–188. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(93)91505-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christopoulos G, Perry KJ, Morfis M, Tilakaratne N, Gao Y, Fraser NJ, Main MJ, Foord SM, Sexton PM. Multiple amylin receptors arise from receptor activity-modifying protein interaction with the calcitonin receptor gene product. Mol Pharmacol. 1999;56:235–242. doi: 10.1124/mol.56.1.235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clementi G, Caruso A, Cutuli VM, Prato A, de Bernardis E, Fiore CE, Amico-Roxas M. Anti-inflammatory activity of amylin and CGRP in different experimental models of inflammation. Life Sci. 1995;57:PL193–197. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(95)02100-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clementi G, Valerio C, Emmi I, Prato A, Drago F. Behavioral effects of amylin injected intracerebroventricularly in the rat. Pept. 1996;17:589–591. doi: 10.1016/0196-9781(96)00062-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collier HO, Dinneen LC, Johnson CA, Schneider C. The abdominal constriction response and its suppression by analgesic drugs in the mouse. Br J Pharmacol Chemother. 1968;32:295–310. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1968.tb00973.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cottrell GS, Roosterman D, Marvizon JC, Song B, Wick E, Pikios S, Wong H, Berthelier C, Tang Y, Sternini C, Bunnett NW, Grady EF. Localization of calcitonin receptor-like receptor and receptor activity modifying protein 1 in enteric neurons, dorsal root ganglia, and the spinal cord of the rat. J Comp Neurol. 2005;490:239–255. doi: 10.1002/cne.20669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Este L, Casini A, Wimalawansa SJ, Renda TG. Immunohistochemical localization of amylin in rat brainstem. Pept. 2000;21:1743–1749. doi: 10.1016/s0196-9781(00)00325-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de los Santos-Arteaga M, Sierra-Dominguez SA, Fontanella GH, Delgado-Garcia JM, Carrion AM. Analgesia induced by dietary restriction is mediated by the kappa-opioid system. J Neurosci. 2003;23:11120–11126. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-35-11120.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dun SL, Brailoiu E, Wang Y, Brailoiu GC, Liu-Chen LY, Yang J, Chang JK, Dun NJ. Insulin-like peptide 5: expression in the mouse brain and mobilization of calcium. Endocrin. 2006;147:3243–3248. doi: 10.1210/en.2006-0237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edelman S, Maier H, Wilhelm K. Pramlintide in the treatment of diabetes mellitus. BioDrugs. 2008;22:375–386. doi: 10.2165/0063030-200822060-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gebre-Medhin S, Mulder H, Zhang Y, Sundler F, Betsholtz C. Reduced nociceptive behavior in islet amyloid polypeptide (amylin) knockout mice. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 1998;63:180–183. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(98)00269-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbey SG, Ghatei MA, Bretherton-Watt D, Zaidi M, Jones PM, Perera T, Beacham J, Girgis S, Bloom SR. Islet amyloid polypeptide: production by an osteoblast cell line and possible role as a paracrine regulator of osteoclast function in man. Clin Sci (Lond) 1991;81:803–808. doi: 10.1042/cs0810803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris JA. Using c-fos as a neural marker of pain. Brain Res Bull. 1998;45:1–8. doi: 10.1016/s0361-9230(97)00277-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovacs AM, Telegdy G. The effects of amylin on motivated behavior in rats. Physiol Behav. 1996;60:183–186. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(95)02254-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee IO, Seo Y. The effects of intrathecal cyclooxygenase-1, cyclooxygenase-2, or nonselective inhibitors on pain behavior and spinal Fos-like immunoreactivity. Anesth Analg. 2008;106:972–977. doi: 10.1213/ane.0b013e318163f602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma W, Chabot JG, Quirion R. A role for adrenomedullin as a pain-related peptide in the rat. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:16027–16032. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0602488103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muff R, Born W, Lutz TA, Fischer JA. Biological importance of the peptides of the calcitonin family as revealed by disruption and transfer of corresponding genes. Pept. 2004;25:2027–2038. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2004.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulder H, Leckstrom A, Uddman R, Ekblad E, Westermark P, Sundler F. Islet amyloid polypeptide (amylin) is expressed in sensory neurons. J Neurosci. 1995;15:7625–7632. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-11-07625.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulder H, Lindh AC, Ekblad E, Westermark P, Sundler F. Islet amyloid polypeptide is expressed in endocrine cells of the gastric mucosa in the rat and mouse. Gastroenter. 1994;107:712–719. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(94)90118-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamoto H, Soeda Y, Takami S, Minami M, Satoh M. Localization of calcitonin receptor mRNA in the mouse brain: coexistence with serotonin transporter mRNA. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 2000;76:93–102. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(99)00335-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olsson M, Herrington MK, Reidelberger RD, Permert J, Arnelo U. Comparison of the effects of chronic central administration and chronic peripheral administration of islet amyloid polypeptide on food intake and meal pattern in the rat. Pept. 2007;28:1416–1423. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2007.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paxinos G, Chai SY, Christopoulos G, Huang XF, Toga AW, Wang HQ, Sexton PM. In vitro autoradiographic localization of calcitonin and amylin binding sites in monkey brain. J Chem Neuroanat. 2004;27:217–236. doi: 10.1016/j.jchemneu.2004.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riediger T, Schmid HA, Lutz T, Simon E. Amylin potently activates AP neurons possibly via formation of the excitatory second messenger cGMP. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2001;281:R1833–1843. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.2001.281.6.R1833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodella L, Rezzani R, Gioia M, Tredici G, Bianchi R. Expression of Fos immunoreactivity in the rat supraspinal regions following noxious visceral stimulation. Brain Res Bull. 1998;47:357–366. doi: 10.1016/s0361-9230(98)00123-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sagar SM, Sharp FR, Curran T. Expression of c-fos protein in brain: metabolic mapping at the cellular level. Sci. 1988;240:1328–1331. doi: 10.1126/science.3131879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samonina GE, Kopylova GN, Lukjanzeva GV, Zhuykova SE, Smirnova EA, German SV, Guseva AA. Antiulcer effects of amylin: a review. Pathophysiol. 2004;11:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.pathophys.2003.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandkuhler J, Treier AC, Liu XG, Ohnimus M. The massive expression of c-fos protein in spinal dorsal horn neurons is not followed by long-term changes in spinal nociception. Neurosci. 1996;73:657–666. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(96)00073-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sexton PM, Paxinos G, Kenney MA, Wookey PJ, Beaumont K. In vitro autoradiographic localization of amylin binding sites in rat brain. Neurosci. 1994;62:553–567. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(94)90388-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sibilia V, Pagani F, Lattuada N, Rapetti D, Guidobono F, Netti C. Amylin compared with calcitonin: competitive binding studies in rat brain and antinociceptive activity. Brain Res. 2000;854:79–84. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(99)02286-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silvestre RA, Salas M, Rodriguez-Gallardo J, Garcia-Hermida O, Fontela T, Marco J. Effect of (8-32) salmon calcitonin, an amylin antagonist, on insulin, glucagon and somatostatin release: study in the perfused pancreas of the rat. Br J Pharmacol. 1996;117:347–350. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1996.tb15197.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skofitsch G, Wimalawansa SJ, Jacobowitz DM, Gubisch W. Comparative immunohistochemical distribution of amylin-like and calcitonin gene related peptide like immunoreactivity in the rat central nervous system. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 1995;73:945–956. doi: 10.1139/y95-131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stridsberg M, Tjalve H, Wilander E. Whole-body autoradiography of 123I-labelled islet amyloid polypeptide (IAPP). Accumulation in the lung parenchyma and in the villi of the intestinal mucosa in rats. Acta Oncol. 1993;32:155–159. doi: 10.3109/02841869309083905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomizawa M, Cowan A, Casida JE. Analgesic and toxic effects of neonicotinoid insecticides in mice. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2001;177:77–83. doi: 10.1006/taap.2001.9292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Rossum D, Hanisch UK, Quirion R. Neuroanatomical localization, pharmacological characterization and functions of CGRP, related peptides and their receptors. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 1997;21:649–678. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(96)00023-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Rout UK, Bagchi IC, Armant DR. Expression of calcitonin receptors in mouse preimplantation embryos and their function in the regulation of blastocyst differentiation by calcitonin. Development. 1998;125:4293–4302. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.21.4293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young AA. Amylin Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; Patent, US 5677279 Methods and compositions for treating pain with amylin or agonists thereof. 1997

- Young AA. Amylin: physiology and pharmacology. Elsevier; 2005. [Google Scholar]