Abstract

To provide a continuous and prolonged delivery of the substrate D-luciferin for bioluminescence imaging in vivo, luciferin was encapsulated into liposomes using either the pH-gradient or acetate-gradient method. Under optimum loading conditions, 0.17 mg luciferin was loaded per mg of lipid with 90–95% encapsulation efficiency, where active loading was 6 to 18-fold higher than obtained with passive loading. Liposomal luciferin in a long-circulating formulation had good shelf stability, with 10% release over 3-month storage at 4°C. Pharmacokinetic profiles of free and liposomal luciferin were then evaluated in transgenic mice expressing luciferase. In contrast to rapid in vivo clearance of free luciferin (t1/2=3.54 min), luciferin encapsulated into long-circulating liposomes showed a prolonged release over 24 hours. The first order release rate constant of luciferin from long-circulating liposomes, as estimated from the best fit of the analytical model to the experimental data, was 0.01 h−1. Insonation of luciferin-loaded temperature sensitive liposomes directly injected into one tumor of Met1-luc tumor-bearing mice resulted in immediate emission of light. Systemic injection of luciferin-loaded long-circulating liposomes into Met1-luc tumor-bearing mice, followed by unilateral ultrasound-induced hyperthermia, produced a gradual increase in radiance over time, reaching a peak 4–7 h post-ultrasound.

Keywords: Bioluminescence Imaging, Liposome, D-luciferin, Active loading, Hyperthermia, Ultrasound

1. Introduction

Bioluminescence imaging provides a highly sensitive method for noninvasive, cost-effective, and real-time monitoring of sophisticated biological processes in intact animals, in part due to the favorable spectral properties and lack of toxicity of the substrate D-luciferin [1–5]. In vivo bioluminescence imaging requires the exogenous delivery of luciferin, which is rapidly cleared from blood circulation, and thus, provides only a short imaging window [6]. Imaging based on repeated injections of luciferin cannot track rapid biological events due to variable levels of luciferin delivery and the time-frame of substrate elimination from body. A pump-assisted mode of delivery of luciferin has been proposed for continuous delivery of luciferin; in vivo monitoring of the signal transduction process with an enhanced temporal resolution was reported with this system [7, 8]. Here, we choose to locally deliver luciferin as a means of assessing the utility of activatable drug delivery vehicles—radiance is increased when luciferin is released from the vehicles.

We encapsulated D-luciferin within a liposomal system incorporating concentrations of polyethelene glycol (PEG) up to 10 mole % [9, 10]. Liposomes can protect their contents from metabolism and inactivation in the plasma, reduce drug toxicity and prolong the blood circulation of encapsulated materials [11–14]. We consider both long-circulating liposomes (LCLs) incorporating cholesterol and temperature-sensitive liposomes (TSLs) incorporating lysolipids using previously published formulations [15–17]. TSLs are well suited for direct delivery to tumors when combined with hyperthermia to induce a burst release [18, 19]. Here, we can directly visualize the radiance resulting from the enzymatic reaction that follows the release of luciferin.

The most widely used method of encapsulation uses passive loading, in which liposomes are formed in the presence of drug. With passive loading, the maximum concentration of the encapsulating material achieved inside the liposomes never exceeds the concentration that is applied to the outside the liposomes; in most cases, the encapsulation efficiencies are not greater than 10% [20]. Alternatively, active loading, which is based on formation of a transmembrane pH or salt gradient, can increase the encapsulation efficiency, as reported for amphipathic chemotherapeutics such as doxorubicin and vincristine [21–23]. Due to the amphipathic nature of these molecules in aqueous solutions, they coexist in neutral and charged forms [24, 25]. Upon inducing a pH imbalance across the lipid bilayer of liposomes, neutral forms permeate the bilayer membrane faster than the charged form. Protonation of the permeated species results in entrapment of the molecule at a concentration that is higher than the extra-liposomal concentration [21, 26].

D-luciferin (Fig. 1) is a small amphipathic molecule, which is uncharged below pH 4.0, negatively charged at higher pH values and is known to permeate through the lipid bilayer in its neutral form [27]. This motivated us to explore active loading via the pH-gradient and the acetate gradient methods to encapsulate luciferin at a concentration that is sufficient to obtain a detectable signal level for extended imaging studies. Factors that affect loading such as lipid formulation, molar ratio of PEG lipids and loading temperature were investigated and optimized.

Figure 1.

Chemical structure of D-luciferin.

The efficiency and stability of liposomal luciferin are evaluated in transgenic mouse models expressing the luciferase reporter gene [28, 29]; first, we characterize the pharmacokinetics (PK) following systemic injection. A mathematical model describing the pharmacokinetics of free and liposomal luciferin was developed and PK parameters are calculated here. Furthermore, the effects of hyperthermia induced by ultrasound on activation of liposomal luciferin are studied. Radiance before and after tumor insonation with systemic and intratumoral injection is quantified. While systemic injection is desirable, local injection and activation provide an opportunity to increase drug concentration and assess release from the capsule [30, 31].

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

1,2-dipalmitoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (DPPC), 1,2-distearoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (DSPC), L-α-phosphatidylcholine, hydrogenated soy (HSPC), 1,2 distearoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine-N-[Methoxy(Polyethylene glycol)-2000] (DSPE-PEG2k), 1-palmitoyl-2-hydroxy-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (lyso-palmitoyl PC) and cholesterol were purchased from Avanti Polar Lipids Inc. (Alabaster, AL). Firefly luciferase, ATP disodium salt, EDTA, dithiothreitol (DTT), bovine serum albumin (BSA), sodium acetate, magnesium acetate, sodium sulfate, and HEPES were supplied by Sigma (St. Louis, MO). Buffers and purification reagents were obtained as follows: tris [tris (hydroxymethyl) aminomethane] from EM Science (Gibbstown, NJ), Dulbacco phosphate buffer without calcium and magnesium, pH 7.4 (DPBS) from Gibco (Grand Island, NY), calcium acetate from MP Biomedical (Santa Ana, CA), CENTRISART, centrifugal ultra filtration units with 20,000 MWCO from Sartorius North America, Inc. (Edgewood, NY), and Sephadex G75 from GE Healthcare, Biosciences AB (Uppsala, Sweden). D-luciferin potassium salt (luciferin) was obtained from Gold Bio Technology, Inc (St. Louis, MO), while mouse serum complement was obtained from Innovative Research Inc. (Southfield, MI).

2.2. Methods

2.2.1. Liposomes and loading

Liposomal formulations used in this study are as follows:

Temperature sensitive liposomes composed of DPPC:lyso-palmitoyl PC:DSPE-PEG2k with molar ratios of 86:10:4, and 86:4:10 [32]. TSLs described here use 4% PEG, unless otherwise stated.

Long-circulating liposomes prepared from SoyPC:chol:DSPE-PEG2k (56:39:5) [33].

2.2.1.1. Passive loading

Lipids, as listed for each liposomal preparation, were added in chloroform to a test tube with total lipid mass of 12 mg. Liposomes were formed in 0.3 ml of Dulbecco’s phosphate buffered saline (DPBS, without Ca2+ and Mg2+, Invitrogen) with adjusted osmolarity at 300 mOsm and in the presence of luciferin at 1 and 20 mg/ml concentrations in TSLs and LCLs, respectively, as described earlier [34, 35]. The multi-lamellar lipid solution at a final concentration of 40 mg/mL was extruded above the phase transition temperature of the lipid mixture through a polycarbonate membrane with a pore diameter of 100 nm. Luciferin-loaded liposomes were then separated from non-encapsulated luciferin by passing the extruded liposomal solution through a column of Sephadex G-75 (10 × 1 cm). Elution of the liposomes was monitored by turbidity measurements at 300 nm using a NanoDrop ND-100 spectrophotometer (NanoDrop Technologies, Inc., Wilmington, DE).

2.2.1.2. Active loading

For our in vitro studies, active loading of luciferin by several methods was compared and summarized in Table 1. In vivo studies were performed with the acetate gradient method, as previous studies suggest that the stability of weak acid loading is greatest with this method [26] and our preliminary in vivo data showed ~10% greater circulation of luciferin using this method compared to the pH-gradient method (data not shown). Three steps were involved in either the pH or acetate gradient methods as described below:

Step 1) In the pH gradient method, liposomes were prepared in either 300 mM Hepes buffer (pH 8.0) or 300 mM Tris buffer (pH 10.0) at a total lipid concentration of 40 mg/mL, as described in the previous section. After extrusion using 100 nm polycarbonate membranes, the extra-liposomal pH was adjusted to 5.0 by passing the liposomal solution through a column of Sephadex G-75 equilibrated with 20 mM citric acid, including 150 mM NaCl, pH 5.0. By this method, liposomes with intra-liposomal pH of 8.0 or 10.0 and extra-liposomal pH of 5.0 are formed. In the acetate gradient method, liposomes were prepared in 120 mM of either calcium acetate or magnesium acetate or in 150 mM sodium acetate, pH 6.0. The extra-liposomal medium was then changed to 120 mM sodium sulfate, pH 6.0 using a Sephadex G-75 column.

Step 2) Luciferin was dissolved in the extra-liposomal buffer. At a final volume of 50 µL, luciferin was added with a mass of 143, 290 or 725 µg to 300 µL of the eluted liposomes to create a luciferin/lipid ratio of 5/100, 10/100 or 25/100 (w/w), respectively. The mixture was incubated at room temperature for 20–24 h unless otherwise stated.

Step 3) Luciferin-loaded liposomes were then separated by a Sephadex G-75 column and equilibrated with either the extra-liposomal buffer used in the first column or DPBS (pH 7.4).

Table 1.

Luciferin loading into liposomes. For passive loading, each formulation is summarized. For active loading, results were similar between formulations and the average is provided. Here, temperature-sensitive liposomes (TSLs) are comprised of DPPC:lyso-palmitoyl PC:DSPE-PEG2k (86:10:4) and long circulating liposomes (LCLs) of SoyPC:chol:DSPE-PEG2k (56:39:5)

| Loading Method | Intraliposomal pH |

Extraliposomal pH |

Luciferin loaded (µg)/ lipid (mg) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ave | Std | ||||

| Passive | TSLs | 7.4 | 7.4 | 9.3 | 0.3 |

| LCLs | 7.4 | 7.4 | 28.8 | 0.4 | |

| pH gradient 10/5 |

10.0 | 5.0 | 172.0 | 5.1 | |

| pH gradient 8/5 |

8.0 | 5.0 | 73.6 | 1.3 | |

| Na-acetate gradient |

6.0 | 6.0 | 85.0 | 0.3 | |

| Ca-acetate gradient |

6.0 | 6.0 | 100.0 | 0.1 | |

| Mg-acetate gradient |

6.0 | 6.0 | 108.0 | 0.0 | |

The loading efficiency was determined as:

| (1) |

2.2.2. Size and concentration measurements of liposomes

The liposomal diameter was ~100 nm (99.9 nm ± 11.1 nm), as measured using a NICOMP™ 380 ZLS submicron particle analyzer (Particle Sizing System Inc., Santa Barbara, CA). Lipid concentration was measured using the Phospholipids C assay kit (Wako Chemicals USA, Richmond, VA). The final solution of liposome-loaded luciferin (after the second Sephadex column) had a lipid concentration of 3–4 mg/mL.

2.2.3. Measurements of luciferin loaded into liposomes

The in vitro quantification of luciferin was performed by both an absorbance measurement of luciferin at 330 nm using a NanoDrop ND-100 spectrophotometer and a luciferase assay. For the luciferase assay, a 1.0 mM solution of ATP was prepared by dissolving ATP in 25 mM HEPES buffer, pH 7.5, containing 2 mM EDTA. A luciferase solution was prepared by dissolving 1 mg of luciferase in 50 ml of 25 mM HEPES buffer, pH 7.5, containing 24 mM magnesium acetate, 3 mg BSA, 2 mg DTT, and 2 mM EDTA [36]. The luciferase solution was then stored in aliquots of 1.0 ml at − 20°C. The 200 µl of the bioluminescence reaction mixture in each well of a 96-well microplate consisted of 50 µl of the luciferase solution, 25 µl of luciferin or liposomal luciferin solution and 125 µl of the ATP solution to initiate the reaction. The relative light units (RLU) were recorded by the FLx800 Multi-Detection Microplate Reader (BIO-TEK Instruments, Inc., Winooski, VT) for 10 s.

The released luciferin from the liposomal preparation was separated using centrifugal ultra filtration units with a molecular cut off of 20 kD at 2000×g, 15°C for 20 min prior to luciferin quantification using either spectrophotometric or enzymatic methods.

2.2.4. Permeability of luciferin across the liposomal bilayer

LCLs were prepared by creating a Ca-acetate gradient across the lipid bilayer with 120 mM Ca-acetate, pH 6.0 inside and 120 mM sodium sulfate, pH 6.0 outside the liposomes. Loading of luciferin into the preformed liposomes was studied by the addition of free luciferin to the liposomal solution pre-warmed to 50°C at a luciferin/lipid ratio of 25/100 (w/w). The mixture was then incubated with gentle mixing for varied time intervals at 50°C and for 24 h at room temperature. At the end of the incubation, the mixture was placed briefly into an icy water bath to cool the solution down to room temperature. Luciferin-loaded liposomes were separated from non-encapsulated luciferin by running the sample through a Sephadex G-75 column as described in the previous section. The amount of luciferin loaded was measured spectrophotometrically at 330 nm. Triplicate measurements were performed for each time point.

We assume that only uncharged luciferin can cross the lipid bilayer of liposomes. A two-step sequential reaction mechanism is hypothesized for protonation of negatively-charged luciferin (L−) to its uncharged form in the extraliposomal solution (LH) and for deprotonation of uncharged luciferin following permeation into the intraliposomal solution. The permeation rate of unchanged luciferin can be formulated into Eq. 2, and simplified as Eq. 3, where k+1 and k+2 are the reaction rate constants of the protonation and deprotonation reactions, and C1 and C2 are the constants, respectively. Integrating Eq. 3 results in Eq. 4, where the constants C3 and C4 can be determined by applying the initial and boundary conditions.

| (2) |

| (3) |

| (4) |

The constant C5 was estimated to be 0.13 from the best fit of the equation to the experimental data (Fig. 2D, R2= 0.98) and t1/2, the half-time of luciferin permeation, can be calculated from Eq. 5 by substituting [LH](t) with ½[LH]max.

| (5) |

Figure 2.

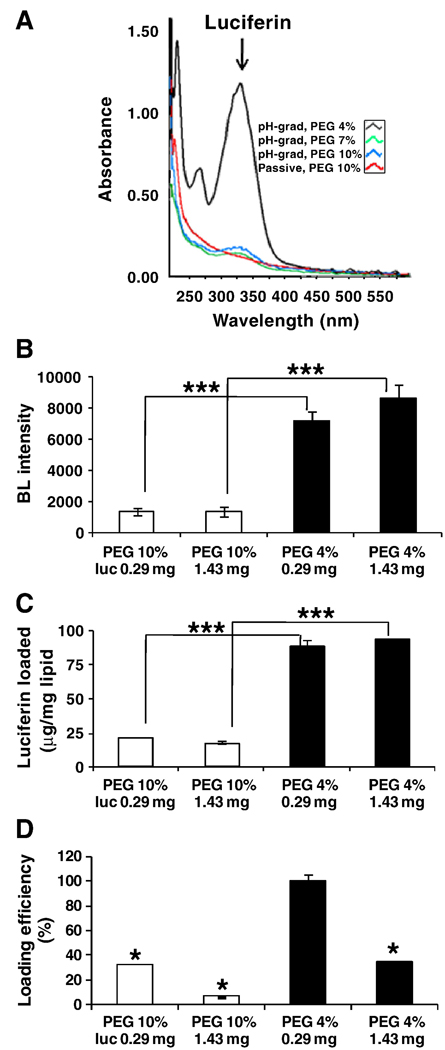

Luciferin loaded in temperature-sensitive liposomes (TSLs) by the pH-gradient 8/5 method compared to the passive method, as a function of PEG2k molar ratio and initial concentration of luciferin. A) Spectra of luciferin loaded. B) Bioluminescence intensity of luciferin loaded. C) Absorbance read of luciferin loaded. D) Loading efficiency assayed by spectrophotometer. Significant difference compared with PEG 4%, 0.29 mg. (* p< 0.05, *** p<0.005).

Permeability is then defined from its relationship with t1/2 according to the following equation:

| (6) |

where r and P are the average radius of liposomes and the permeability coefficient of the solute, respectively [26].

2.2.5. In vitro stability of luciferin loaded liposomes

A stability assay was performed by the addition of 10 µl of luciferin-loaded liposomes (3–4 mg/ml) to 1.0 ml of either DPBS or mouse serum pre-incubated at 25, 37, 42°C. An aliquot of 100 µl was acquired at 0, 1, 5, 15, 30, 60 and 90 min in a 0.5-ml Eppendorf tube and cooled down immediately in an icy water bath to terminate the release. To determine the radiance associated with 100% release, an aliquot of 100 µl was added to a 0.5-ml Eppendorf tube containing 1 µl of 10% Triton X-100 at room temperature (RTX). Luciferin released at t=0 and as a function of time was then quantified as R0 and Rt, respectively, by the enzymatic assay described previously. The percent luciferin released was calculated as:

| (7) |

2.2.6. In vivo studies

All animal handling was performed in accordance with University of California, Davis (UCD), Animal Use and Care Committee guidelines. Transgenic luciferase-expressing animal models supplied by Caliper Life Sciences (Mountain View, CA) and used in this study are the GAPDH-luc model (n=2, each ~25 g), which constitutively expresses luciferase in all tissues with the highest levels in kidney, gonads, brain, and skeletal muscle and the RIP-luc model (n=2, each ~30 g), with the highest luciferase reporter gene expression in the pancreas. In order to assess luciferin delivery within tumors, we also imaged the transplantable FVB polyomavirus middle T oncogene transgenic Met-1 mammary tumor line transfected with the luciferase gene (termed Met1-luc) (n=10, each ~25 g ) [37]. Tumor fragments of approximately 1 mm3 were transplanted into both inguinal fat pads of 3–5 week old FVB females (Charles River Breeding Laboratories). Tumors were grown for 4–6 weeks after transplantation to 0.8–1.2 cm in longitudinal diameter, as measured with calipers. The animals were anesthetized by 3.5% isoflurane and maintained at 2.0–2.5% during the injection and imaging. Each mouse was injected with either free (~2.5 mg luciferin/kg body weight) or liposomal luciferin (~2.5 mg luciferin/kg body weight and ~25 mg lipid/kg body weight). For intravenous injection, 160 µL was delivered through a catheter placed in the tail vein. For intratumoral injection (IT), one tumor per animal was injected in two tumor locations with 80 µl of either free or liposomal luciferin using a 1-ml syringe equipped with a 28G×1/2" needle. Each 1-min injection was guided by ultrasound imaging to insure a uniform distribution of injected material throughout the tumor, with the injections separated by 10 min. Whole body images of mice were acquired before and after injection as described below. In all in vivo studies, a total of 70 µg of luciferin was injected in the free or liposomal form.

2.2.7. In vivo imaging and quantification of bioluminescence data

The in vivo IVIS™ Imaging System (Xenogen Corp., Alameda, CA) was utilized, consisting of a cooled CCD camera mounted on a light-tight specimen chamber (dark box), a camera controller, a camera cooling system and a Windows computer system for data acquisition and analysis. Each mouse was placed in the dark box at 37°C, with the CCD camera cooled to −105°C and a field of view set at 15 cm. The exposure time and f/stop values were set at 1–5 min, f/1, respectively. The photon emission was measured and the gray scale photographic images and bioluminescence color image were superimposed using the LivingImage v. 2.50 software (Xenogen Corp., Alameda, CA). A region of interest (ROI) was manually selected, the area of the ROI was kept constant and the intensity was recorded as average radiance (photons/s/cm2/sr) within an ROI.

64Cu-labeled lipids were included within the liposomes and used to monitor circulation and biodistribution of the lipid shell, as described in [38]. Lipid conjugated with the bisamine bisthiol (BAT) chelator was incorporated within the lipid bilayer of liposomes at a low concentration (0.5 mol %) and the 64Cu isotope was added and purified before injection. Positron Emission Tomography (PET) images were acquired over 24 hours.

2.2.8. Pharmacokinetic modeling of free and liposomal luciferin

A simplified model to describe the whole body disposition of free and liposomal luciferin was derived from a pharmacokinetic (PK) model created previously by Qin et. al. [39] . The two-compartment model for free luciferin includes tissue and plasma; the three-compartment model for liposomal luciferin adds a compartment for the reticulo-endothelial system (RES) [39–41]. Luciferin was introduced into the blood circulation and the tissue compartment via free luciferin administration or release from liposomes (kr), and was eliminated from the body with a first-order rate constant rate of ke. The first order rate of uptake of liposomal luciferin by the RES and the first order release rate of luciferin by the RES are kR and k, respectively. For complete parameter definitions and diagram illustration, please refer to Qin et. al. [39]. In our mathematical modeling, we assumed the quantified light intensity was a direct measure of the velocity of the enzymatic reaction and also considered the bioluminescence reaction as a unireactant enzymatic reaction [42]. To simulate the model and determine the PK parameters, the mass balance equations were derived assuming a first order rate process for uptake, release and elimination processes. PK parameters were estimated by the nonlinear least squares method applying the in vivo imaging data to the luciferin concentration in the plasma [39].

2.2.9. Activation of liposomes by ultrasound-mediated local hyperthermia

Insonation was accomplished using a Siemens SONOLINE ANTARES™ diagnostic ultrasound scanner (Siemens Medical Solutions USA, Inc. Mountain View, CA) that was modified to accept custom probes. The ultrasound probe used in this study was a three-array design consisting of two parallel outside rows of 64 elements operating at 1.5 MHz for therapeutic insonation and a center row of 128 elements operating at 5 MHz for imaging [43]. Temperature feedback was accomplished using a 30-gauge needle thermocouple (HYP-1, Omega Engineering, Inc., Stanford, CT), interfaced to a data acquisition system controlled using LabVIEW™ (National Instruments Corp. Austin, TX) running on a PC. A proportional-integral differential control (PID) system was used to maintain the desired temperature by controlling the transmitted output power on the ultrasound scanner. The ultrasound pulses consisted of 100-cycle bursts at 1.54 MHz center frequency, with variable pulse-repetition frequency (PRF) ranging from 100 Hz up to 5 kHz, and variable peak transmitter voltage ranging from 0 to 20 V. Using a radiation force balance (model UPM-DT-1AV, Ohmic Instruments Co. Easton, MD), the total acoustic power (TAP) measured in deionized water at the peak operating parameters of 5 kHz PRF (32.5% duty-cycle) and 20 V was 4.1 W. Using a needle hydrophone (Müller-Platte Needle Probe, ONDA Inc., Sunnyvale, CA), the peak-negative acoustic pressure at the focus of beam at 35 mm operating depth was measured to be 2.2 MPa, which corresponds to a mechanical index (MI) of 1.8.

For in vivo tumor studies incorporating ultrasound, the region surrounding the tumor was shaved. The animal’s core temperature was monitored using a rectal thermocouple and was maintained above 35°C during the experiment. A custom probe holder directed the ultrasound beam vertically-upward into a small bath of water maintained at 37°C. The water bath served as an acoustic standoff and as a means to maintain the tumor at 37°C. The tumor on one side of the mouse was submerged in the water bath and the needle thermocouple was inserted into the center of the tumor. The tumor was located on the 5 MHz B-mode image, and the beam was focused in the vicinity of the thermocouple. The ultrasound intensity was increased to full power (4.1 W TAP), and the tumor temperature was maintained at 39°C and 42°C for mild hyperthermia for 1 and 5 min, respectively. For intratumoral injection combined with ultrasound, the tumor injected with TSLs was insonified immediately post injection. Following intravenous injection of LCLs, one tumor was insonified at a time from -1 h (1 h pre-injection), to 2 h, 5 h and 12 h post-injection.

2.2.10. Statistical analysis

Data points represent the average of triplicate measurements and the error bars are the standard deviations of the triplicate measurements. Statistical analysis was performed using a one-tailed t-Test assuming unequal variances. Statistical significance was set at p<0.05. The statistical differences are represented as * p<0.05, ** p<0.01, and *** p<0.005.

3. Results

3.1. Active versus passive loading of luciferin

Active loading of luciferin within both LCLs and TSLs peaked at ~172 µg luciferin/mg lipid, and varied with loading method with pH gradient 10/5> Mg-acetate > Ca-acetate > Na-acetate > pH gradient 8/5 > passive loading (Table 1). Passive loading of luciferin in both formulations was low (9.3 µg/mg for TSLs and 28.9 µg/mg for LCLs). For all active loading methods, the luciferin loaded was not significantly different between the formulations. Loading was also smaller when a PEG2k-lipid molar ratio of 7–10% was incorporated into the liposomal membrane. Decreasing the PEG2k lipid concentration to 4–5 mol% increased luciferin loading (p<0.005) (Fig. 2). Loading efficiency was greater than 90% in both TSLs and LCLs when luciferin was actively loaded and the PEG2k lipid concentration was 5 mol% or less (Fig. 2D).

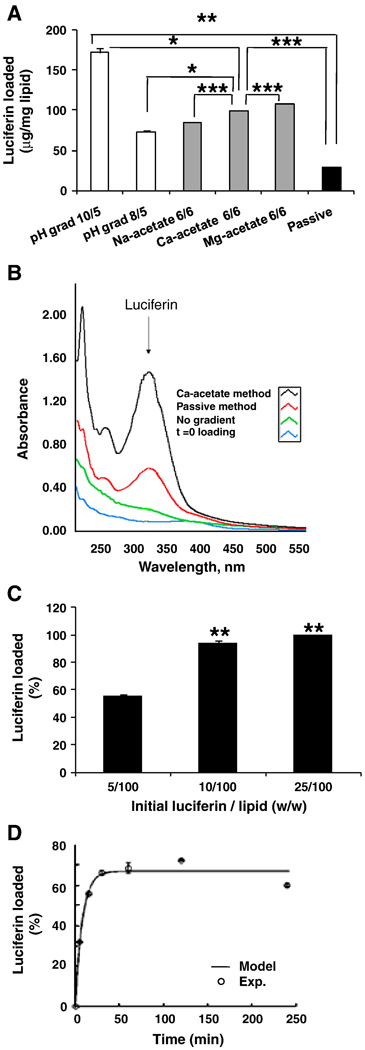

As an alternative to the proton imbalance generated by the pH-gradient across the liposomal membrane, luciferin was loaded with a sustained pH imbalance that was created by a transmembrane difference in acetate concentration. As presented in Table 1 and Fig. 3A, luciferin loading was efficient in the acetate-gradient method with 85, 100, 108 µg luciferin loaded per mg lipid in Na-, Ca-, and Mg-acetate method, respectively, as compared to 73.6 µg/mg-lipid with a pH-gradient 8/5 (p<0.05).

Figure 3.

Luciferin loaded in long-circulating liposomes (LCLs). A) Ratio of luciferin to lipid across different methods of loading. B) Absorbance spectrum following loading with Ca-acetate gradient, passive, no gradient, and t=0 loading. C) Percent loading as a function of luciferin/lipid ratios using the Ca-acetate gradient method. D) Percent loading as a function of time when using Ca-acetate gradient method at 50°C, compared to 100% loading achieved at room temperature after 24h. * Significant difference compared with 5/100 (w/w) initial luciferin/lipid. (* p< 0.05, ** p<0.01, *** p<0.005).

Loading increases in the presence of the acetate gradient and is a function of incubation time (Figs. 3B, 3D). Increasing the luciferin/lipid ratio to 10/100 improved both the total loading and the loading efficiency; additional increases with higher concentrations were small (Fig. 3C). With the Ca-gradient method, luciferin loading increased by 10-fold and 3.5-fold in TSLs and LCLs, respectively, compared with passive loading (Table 1).

3.2. Loading temperature and time, and estimation of luciferin permeability across the liposomal membrane

The effects of temperature and time on luciferin loading were investigated in LCLs using the Ca-acetate method. Loading proceeded faster at 50° C than room temperature. Within 30 min, a plateau was achieved equal to 65% of the maximum loading achievable in 24 h at room temperature (Fig. 3D). A longer incubation of 48 h did not increase loading. The best fit of Eq. 5 to the experimental values (Fig. 3D, R2=0.98), resulted in a calculation of t1/2 and the permeability coefficient as 5.33 min and 3.6×10−9 cm/s, respectively.

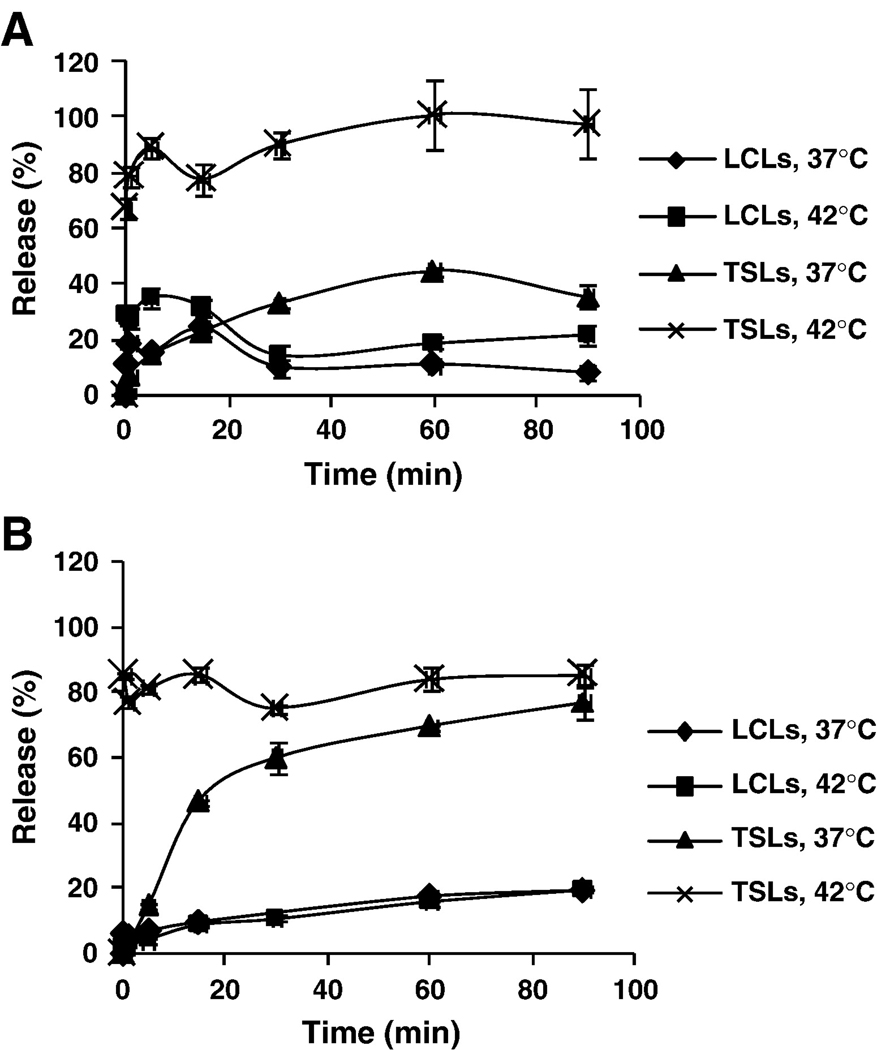

3.3. In vitro release of luciferin

Stability of liposomal luciferin was evaluated in vitro in DPBS buffer and mouse serum at 37°C and 42°C using the enzymatic assay as shown in Fig. 4. The TSLs released nearly 100% of the encapsulated luciferin within 5 minutes of incubation at 42°C in buffer or serum. In contrast, the long-circulating formulation was stable in either buffer or serum, releasing less than 20% of the encapsulated luciferin over 90 minutes.

Figure 4.

In vitro release kinetic of luciferin loaded by Ca-acetate gradient method into TSLs and LCLs at 37°C and 42°C in DPBS (A) and mouse serum (B).

After 3 months of storage, 12% release of liposomal luciferin from LCLs was observed, as compared to TSLs with 30% release (data not shown).

3.4. Pharmacokinetic profiles of free and liposomal luciferin

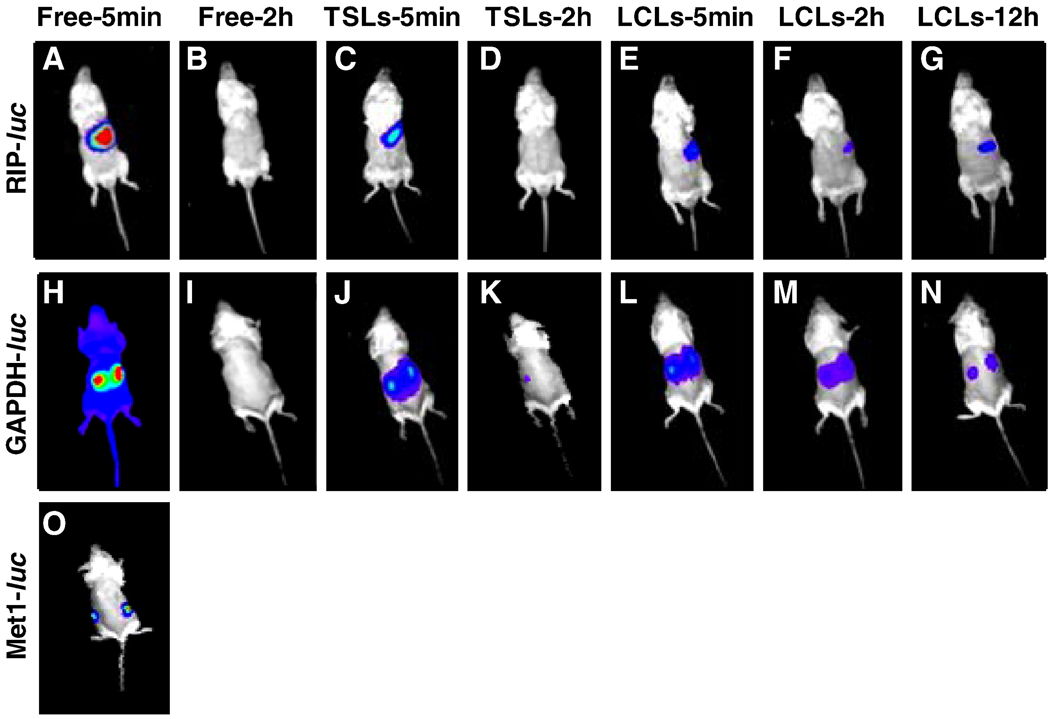

Free luciferin was cleared from circulation within 30 min, as is apparent in 4 min and 2 h images in both the RIP-luc and GAPDH-luc models (Fig. 5A–5B, 5H–5I).

Figure 5.

Images of genetically-engineered mouse models expressing the luc transgene. (A–O) Bioluminescence images acquired post-intravenous injection of free or liposomal luciferin loaded by the Ca-acetate gradient method (70 µg luciferin in all cases). Color map was matched with that of free luciferin in the corresponding animal model. (A–G) Bioluminescence images of transgenic RIP-luc mice; (A–B) Injected with free luciferin (A) and imaged at 5 min and 2 h (B) after injection; (C–D) Injected with TSLs and images acquired after 5 min (C) and 2 h (D); (E–G) Injected with LCLs and images acquired at 5 min (E), 2 h (F), and 12 h (G). (H–N) Bioluminescence images of transgenic GAPDH-luc mice. (H–I) Injected with free luciferin and imaged after 5 min (H) and 2 h (I). (J– K) Injected with TSLs and imaged after 5 min (J) and 2 h (K); (L–N) Injected with LCLs and imaged after 5 min (L), 2 h (M) and 12 h (N). (O) Met1-luc tumor mice injected with free luciferin and imaged after 5 min.

With a matched intensity color map and total injected luciferin, the images acquired for liposomal luciferin in TSLs and LCLs are compared to that of free luciferin for the corresponding animal models (Fig. 5C–5G for RIP-luc and Fig. 5J–5N for GAPDH-luc). A general trend of short circulation of free luciferin, fast release from TSLs, and slow release from LCLs over time is observed for both transgenic RIP-luc and GAPDH-luc animal models. Although the kidneys in the GAPDH-luc mice showed a higher radiance as compared to that of other tissues, bioluminescence intensities quantified by drawing an ROI on each kidney as well as on the lower back of the animal showed similar PK profiles (data not shown).

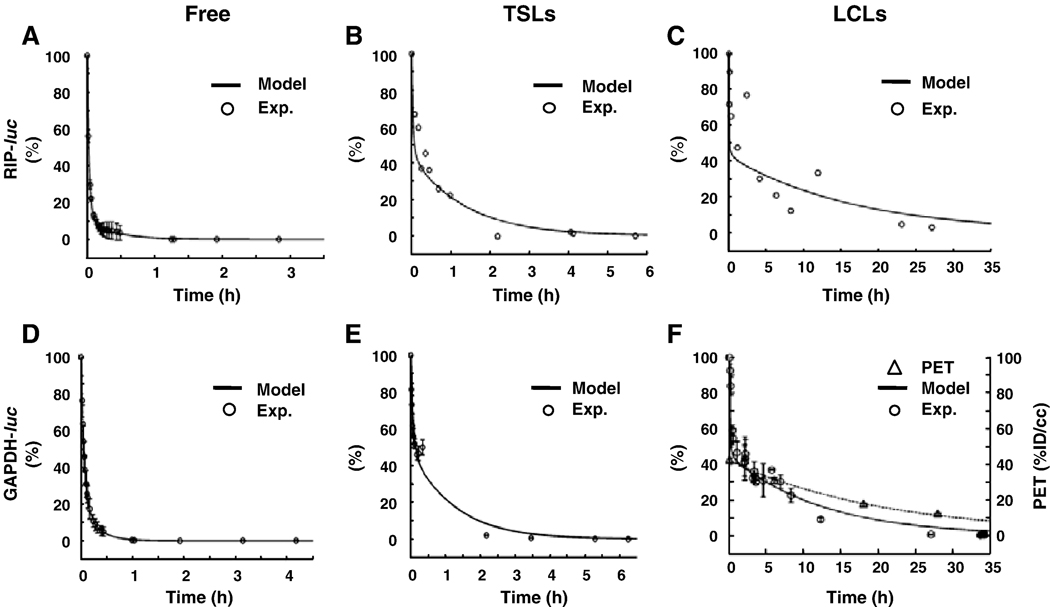

The bioluminescence images were then quantified and used to evaluate the pharmacokinetics of free and liposomal luciferin in RIP-luc (Fig. 6A–6C) and GAPDH-luc mice (Fig. 6D–6F). A rapid clearance of free luciferin was observed with a similar kinetic in all models (Fig. 6A, 6D) with an estimated t1/2 value of 3.54 min. Liposomal luciferin, however, showed a two-phase release kinetic, a rapid release in the early phase (t<30 min) followed by a slower release kinetic (Figs. 6B, 6C, 6E, 6F). Radiance resulting from the injection of TSLs decreased over the first 2 hours. With LCLs, during the first 30 minutes, a rapid decrease in radiance was observed; after 30 minutes, a steady and continuous release profile was demonstrated over a period of 35 h. After 30 minutes, the radiance of LCLs showed a similar trend to the radioactivity of the lipid shell when the chelator BAT-lipid was radiolabeled with 64Cu and quantified by PET (Fig. 6F) [38].

Figure 6.

In vivo circulation assessed from optical radiance and positron emission tomography (PET) of luciferin or liposomes intravenously-injected into transgenic RIP-luc (A–C) and GAPDH-luc (D–F) mice. (A, D) Free luciferin. (B, E) TSLs. (C, F) LCLs. Loading (70 µg luciferin) was performed using Ca-acetate gradient method. For optical data, the Y-axis represents percent of the maximum radiance. (F) Optical radiance (in normalized percentage over time) in the GAPDH-luc (D–F) mice and PET tracer accumulation using an equivalent particle in an FVB mouse (%ID/cc). Liposomal shell was labeled for PET imaging as in [38].

Quantitation of the radiance was accomplished using a compartmental model (Fig. 6, Table 2), demonstrating that circulation and stability vary as LCLs>TSLs>free luciferin in both Transgenic RIP-luc and GAPDH-luc mice. Luciferin loaded in LCLs had a 100-fold greater phase II half-life in circulation as compared to free luciferin. After 30 minutes, the rate of release from LCLs is slow, as shown by the calculated release rate (kr) which approaches zero for LCLs after 30 minutes.

Table 2.

Pharmacokinetic parameters of free and liposomal luciferin in transgenic-luc mouse models

| Transgenic GAPDH-luc mice | Transgenic RIP-luc mice | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| t1/2 (min) |

k (h−1) |

R2 | t1/2 (min) |

k (h−1) |

R2 | |||

| I | II | I | II | |||||

| Free luciferin |

3.3 | 4.35 | ke 9.25 |

0.9999 | 1.6 | 16.8 | ke 14.2 |

0.9995 |

| Luciferin in TSLs |

8.4 | 46.2 | kr 0.26 |

0.9595 | 4.2 | 49.5 | kr 0.16 |

0.9135 |

| Luciferin in LCLs |

12 | 490.8 | kr 0.01 |

0.9995 | 5.4 | 693 | kr 0.00 |

0.4579 |

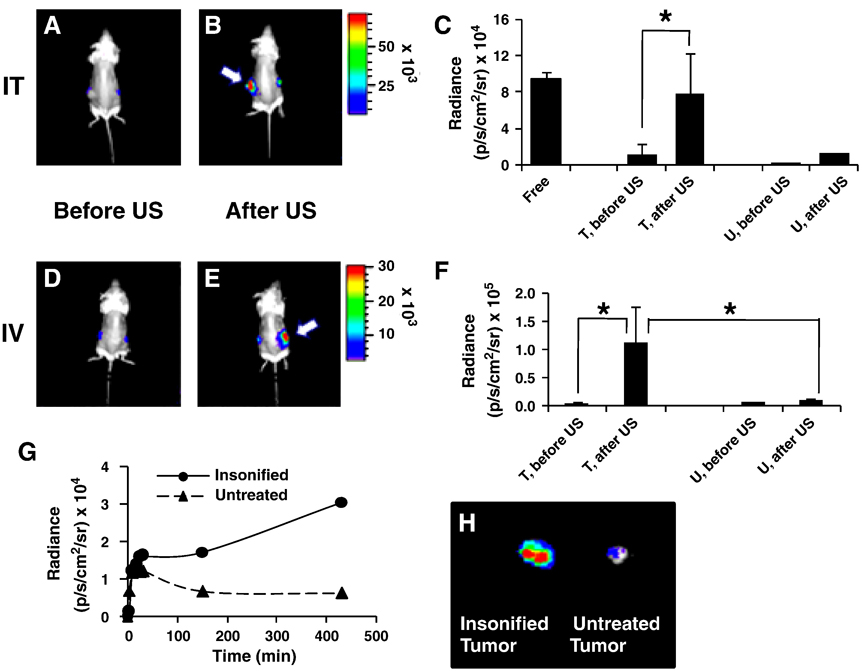

3.5. Local hyperthermia-mediated luciferin release from liposomes by ultrasound

After intratumoral injection, the insonation-mediated release of luciferin from TSLs (39°C for 1 min) was immediately apparent (Fig. 7A and 7B). A 6.5-fold higher radiance was quantified in the insonified tumor compared to that before ultrasound (p<0.05, Fig. 7C). The radiance of the contralateral tumor increased 3.5 fold after ultrasound (Fig. 7C). Radiance was increased from baseline for ~20 minutes, whereas tumor temperature returned to baseline within 5 minutes. Heat-activated release can also be achieved following systemic injection; however, the kinetics are difficult to quantify due to the higher release rate associated with systemic injection.

Figure 7.

Images and radiance before and after insonation of tumors containing liposomes loaded with luciferin by the Ca-acetate method. (A–C) Left tumor received intratumoral injection (IT) of TSLs (n=3, total 70 µg luciferin per each tumor). Injected tumor was immediately insonified (39°C for 1 min). (A–B) Bioluminescence images of Met1-luc tumor-bearing mice before and after ultrasound (arrows indicate the insonified tumor). C) Comparison of peak radiance for insonified tumor (T) vs. contralateral tumor (U) before and after ultrasound (n=8). (D–F) Tail vein injection (IV) of LCLs (n=4, total 70 µg luciferin). At ~6 h post injection, one tumor was insonified (42°C for 5 min) and images were collected ~3 h post- ultrasound. (D–E) Images before (D) and after (E) ultrasound (arrows indicate the insonified tumor). F) Peak radiance of the insonified tumor (T) before and after ultrasound vs. contralateral tumor (U). G) Time profile of radiance of insonified tumor compared with contralateral tumor (5 min at 42°C), following intravenous injection of LCLs (total 70 µg luciferin) one hour post-ultrasound. H) Radiance of dissected tumors. (* p< 0.05).

Tumor insonation following injection of LCLs did not immediately increase radiance. To further study the effect of insonation following systemic injection, a longer study with a higher ultrasound dose was conducted. From 1 hour before to 12 hours after intravenous injection of LCLs, one tumor of each mouse was insonified for 5 minutes with the temperature maintained within the tumor at 42°C during insonation. The radiance of the insonified tumor increased slowly, reaching an average of 20-fold higher magnitude at 4–7 h post ultrasound, as compared to the initial time point (p<0.05, Fig.7D–7F). Following an increase in radiance after injection, the radiance of the contralateral tumor in the same mouse decreased with time. As one example of the kinetics of the observed radiance (Fig. 7G–7H), an 18-fold increase in radiance of insonified tumor was quantified seven hours after the application of ultrasound, with the ex vivo tumors removed at the final time point shown in Fig. 7H. In this small study, the radiance of the insonified tumor increased regardless of the timing of ultrasound relative to injection of the liposomes; however, a larger study is required to characterize the time course.

4. Discussion

The firefly luciferin substrate, D-luciferin, is an amphipathic molecule which is charged at physiological pH due to its carboxyl group; however, at a lower pH when the luciferin molecule is protonated, luciferin can be efficiently loaded within liposomes. The half life and permeability coefficient of uncharged luciferin were calculated to be 5.33 min and 3.6×10−9 cm/s, respectively. This motivated us to design a gradient method to actively load luciferin into liposomes.

Two formulations have been presented and discussed here, where the first formulation contains lyso-palmitoyl PC, known to release at a low-temperature and the second formulation contains HSPC and cholesterol, known to increase stability. In each case, not surprisingly, we found active loading of luciferin to be highly sensitive to PEG concentration. The presence of PEG lipids at a concentration higher than 5% greatly reduced the loading of luciferin.

Under optimized conditions, the maximum luciferin loaded by the Ca-acetate method exceeded an intra-liposomal concentration of 150 mM, which was 3.5- to 10-fold higher than that obtained by passive loading in LCLs and TSLs, respectively. The efficiency of luciferin loading was greatest using a larger pH gradient (10/5) or using the acetate-gradient method. A transmembrane gradient of acetate (~0.1 M) has been shown to create a net transfer of protons from the inside of liposomes to the external medium, resulting in a pH gradient in liposomes of 3 units [26]. Here, acetate gradient methods achieved greater loading efficiency than directly imposing a pH gradient of 3 units. Additionally, acetate gradient methods are preferred since the presence of cations acts as a reservoir for sustaining the pH difference across the membrane. Bivalent cations are known to favor the formation of a complex with a weak acid inside liposomes, thus ensure the stability of the loading and we therefore chose to perform the in vivo studies using acetate-gradient loading [26]. We observed that non-permeable cations such as Na, Ca, Mg increased the loading of luciferin with the order of Mg>Ca>Na.

The stability of liposomal luciferin was first studied in vitro by monitoring luciferin release in buffer and serum at 37°C (physiological temperature) and 42°C (mild-hyperthermia). Liposomal luciferin in TSLs showed a rapid release in 10–20 seconds at 42°C (above the phase transition temperature), with more than 80% release of luciferin in both buffer and serum. In contrast, LCLs were more stable with an average release of 20% in either buffer or serum at 42°C. Liposomal luciferin in LCLs showed good shelf stability with 10% release after a period of 3 months at 4°C.

To evaluate the in vivo stability of liposomal luciferin loaded using the Ca-acetate gradient method in either TSLs or LCLs, liposomes were intravenously administrated via the tail vein into transgenic mice. Free luciferin cleared rapidly (within 30 min) with a biphasic time course. Luciferin encapsulated in TSLs cleared in less than 2 h, as reported elsewhere [19]. For a period of 30 min, both liposomal formulations demonstrated an early and rapid release similar to free luciferin. For LCLs, this was followed by a slow release in the second phase, which is more likely the release of the encapsulated luciferin. We hypothesize that the early rapid release observed for luciferin in LCLs results from ~20% of the total luciferin that is initially associated with the membrane and further studies will be required to fully stabilize the loaded luciferin in LCLs.

Here, we applied ultrasound as a non-invasive, site-specific, image-guided means of heating. With TSLs, a burst of light was immediately detected from the insonified tumor. The increase was quantified here for the simplified case of intratumoral injection, indicating that the luciferin was indeed released upon insonation. After insonation, a 6.5-fold increase in the peak radiance was estimated for the injected and heated tumor, compared with a 3.5-fold increase in the contralateral tumor. Thus, following intratumoral injection, it is feasible to achieve a higher luciferin concentration at the site of insonation than in other tissues, even after release. This temperature sensitive formulation provides a probe for optimizing ultrasound methods for local release.

Following the injection of LCLs, insonation did not produce an immediate increase in radiance. Instead, for systemic injection, a slow increase in radiance of the insonified tumor was observed over 4–7 hours even when insonation occurred hours post-injection. We hypothesize that the increased radiance results from an increased tumor accumulation of the particles which is induced by insonation, confirming that a significant volume of encapsulated luciferin remains in circulation. We have also observed that radiolabeled particles accumulate following insonation (data not shown). Thus, the encapsulation of luciferin within radiolabeled LCLs may facilitate an evaluation of ultrasound-enhanced particle accumulation and release.

5. Conclusion

D-luciferin was efficiently encapsulated into liposomes using active loading generated by a pH-gradient or acetate gradient across the liposomal membrane. Luciferin encapsulated in long-circulating liposomes delivered more than 0.1 mg luciferin per mg lipid, with sufficient radiance for more than 12 hours of imaging when systemically administrated to transgenic mice expressing luciferase. Pharmacokinetic studies revealed a longer circulation of luciferin when encapsulated in long-circulating liposomes as compared with temperature-sensitive liposomes and free luciferin. Furthermore, liposomal luciferin was responsive to hyperthermia induced by ultrasound following intratumoral injection of temperature-sensitive particles, demonstrating an increased local concentration. For insonation following systemic injection of long circulating particles, enhanced radiance was observed over many hours.

Acknowledgement

This work was funded by NIH R01 CA103828 and R21 EB009434

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Edinger M, Sweeney TJ, Tucker AA, Olomu AB, Negrin RS, Contag CH. Noninvasive assessment of tumor cell proliferation in animal models. Neoplasia (New York) 1999;1(4):303–310. doi: 10.1038/sj.neo.7900048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sweeney TJ, Mailander V, Tucker AA, Olomu AB, Zhang WS, Cao YA, Negrin RS, Contag CH. Visualizing the kinetics of tumor-cell clearance in living animals. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1999;96(21):12044–12049. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.21.12044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tang Y, Shah K, Messerli SM, Snyder E, Breakefield X, Weissleder R. In vivo tracking of neural progenitor cell migration to glioblastomas. Human Gene Therapy. 2003;14(13):1247–1254. doi: 10.1089/104303403767740786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhang W, Feng JQ, Harris SE, Contag PR, Stevenson DK, Contag CH. Rapid in vivo functional analysis of transgenes in mice using whole body imaging of luciferase expression. Transgenic Research. 2001;10(5):423–434. doi: 10.1023/a:1012042506002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Contag CH, Bachmann MH. Advances in vivo bioluminescence imaging of gene expression. Annual Review of Biomedical Engineering. 2002;4:235–260. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bioeng.4.111901.093336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Berger F, Paulmurugan R, Gambhir SS. Uptake kinetics and biodistribution of 14C-D-Luciferin, a radiolabeled substrate for the firefly luciferase catalyzed bioluminescent reaction. Soc Nuclear Medicine Inc. 2003:1135. doi: 10.1007/s00259-008-0870-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gross S, Abraham U, Prior JL, Herzog ED, Piwnica-Worms D. Continuous delivery of D-luciferin by implanted microosmotic pumps enables true real-time bioluminescence imaging of luciferase activity in vivo. Molecular Imaging. 2007;6(2):121–130. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gross S, Piwnica-Worms D. Real-time imaging of ligand-induced IKK activation in intact cells and in living mice. Nature Methods. 2005;2(8):607–614. doi: 10.1038/nmeth779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chou TH, Chu IM. Thermodynamic characteristics of DSPC/DSPE-PEG(2000) mixed monolayers on the water subphase at different temperatures. Colloids and Surfaces B-Biointerfaces. 2003;27(4):333–344. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Teshima M, Kawakami S, Fumoto S, Nishida K, Nakamura J, Nakashima M, Nakagawa H, Ichikawa N, Sasaki H. PEGylated liposomes loading palmitoyl prednisolone for prolonged blood concentration of prednisolone. Biological & Pharmaceutical Bulletin. 2006;29(7):1436–1440. doi: 10.1248/bpb.29.1436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Drummond DC, Meyer O, Hong KL, Kirpotin DB, Papahadjopoulos D. Optimizing liposomes for delivery of chemotherapeutic agents to solid tumors. Pharmacological Reviews. 1999;51(4):691–743. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Torchilin VP. Recent advances with liposomes as pharmaceutical carriers. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery. 2005;4(2):145–160. doi: 10.1038/nrd1632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Allen TM. Long-Circulating (Sterically Stabilized) Liposomes for Targeted Drug-Delivery. Trends in Pharmacological Sciences. 1994;15(7):215–220. doi: 10.1016/0165-6147(94)90314-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Woodle MC. Sterically stabilized liposomes as drug delivery systems for biotechnology therapeutics. Biopharm-the Technology & Business of Biopharmaceuticals. 1996;9(8):46–49. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kong G, Braun RD, Dewhirst MW. Hyperthermia enables tumor-specific nanoparticle delivery: Effect of particle size. Cancer Res. 2000;60(16):4440–4445. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kong G, Dewhirst MW. Hyperthermia and liposomes. Int. J. Hyperthermia. 1999;15(5):345–370. doi: 10.1080/026567399285558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gaber MH, Wu NZ, Hong KL, Huang SK, Dewhirst MW, Papahadjopoulos D. Thermosensitive liposomes: Extravasation and release of contents in tumor microvascular networks. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 1996;36(5):1177–1187. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(96)00389-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bao AD, Phillips WT, Goins B, Zheng XP, Sabour S, Natarajan M, Woolley FR, Zavaleta C, Otto RA. Potential use of drug carried-liposomes for cancer therapy via direct intratumoral injection. International Journal of Pharmaceutics. 2006;316(1–2):162–169. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2006.02.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ponce AM, Wright A, Dewhirts MW, Needham D. Targeted bioavailability of drugs by triggered release from liposomes. Future Lipidology. 2007;1(1):25–34. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hwang SH, Maitani Y, Qi XR, Takayama K, Nagai T. Remote loading of diclofenac, insulin and fluorescein isothiocyanate labeled insulin into liposomes by pH and acetate gradient methods. International Journal of Pharmaceutics. 1999;179(1):85–95. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5173(98)00392-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Haran G, Cohen R, Bar LK, Barenholz Y. Transmembrane Ammonium-Sulfate Gradients in Liposomes Produce Efficient and Stable Entrapment of Amphipathic Weak Bases. Biochimica Et Biophysica Acta. 1993;1151(2):201–215. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(93)90105-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mayer LD, Bally MB, Hope MJ, Cullis PR. Uptake of Antineoplastic Agents into Large Unilamellar Vesicles in Response to a Membrane-Potential. Biochimica Et Biophysica Acta. 1985;816(2):294–302. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(85)90497-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhigaltsev IV, Maurer N, Akhong QF, Leone R, Leng E, Wang J, Semple SC, Cullis PR. Liposome-encapsulated vincristine, vinblastine and vinorelbine: A comparative study of drug loading and retention. Journal of Controlled Release. 2005;104(1):103–111. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2005.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ceh B, Lasic DD. A rigorous theory of remote loading of drugs into liposomes: Transmembrane potential and induced pH-gradient loading and leakage of liposomes. Journal of Colloid and Interface Science. 1997;185(1):9–18. doi: 10.1006/jcis.1996.4555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nichols JW, Deamer DW. Catecholamine Uptake and Concentration by Liposomes Maintaining pH-gradients. Biochimica Et Biophysica Acta. 1976;455(1):269–271. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(76)90169-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Clerc S, Barenholz Y. Loading of amphipathic weak acids into liposomes in response to transmembrane calcium acetate gradients. Biochimica Et Biophysica Acta-Biomembranes. 1995;1240(2):257–265. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(95)00214-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McElroy WD, Strehler BL. Bioluminescence. Bacteriological Reviews. 1954;18(3):177–194. doi: 10.1128/br.18.3.177-194.1954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen XJ, Zhang XM, Larson CS, Baker MS, Kaufman DB. In vivo bioluminescence imaging of transplanted islets and early detection of graft rejection. Transplantation. 2006;81(10):1421–1427. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000206109.71181.bf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chen XJ, Zhang XM, Larson C, Xia GL, Kaufman DB. Prolonging islet allograft survival using in vivo bioluminescence imaging to guide timing of antilymphocyte serum treatment of rejection. Transplantation. 2008;85(9):1246–1252. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e31816b66b0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Medina L, Goins B, Rodríguez-Villafuerte M, Bao A, Martínez-Davalos A, Awasthi V, Galván OO, Santoyo C, Phillips WT, Brandan ME. Spatial dose distributions in solid tumors from 186Re transported by liposomes using HS radiochromic media. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2007;34(7):1039–1049. doi: 10.1007/s00259-006-0297-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang SX, Bao A, Herrera SJ, Phillips WT, Goins B, Santoyo C, Miller FR, Otto RA. Intraoperative 186Re-Liposome Radionuclide Therapy in a Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma Xenograft Positive Surgical Margin Model. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14(12):3975–3983. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-4149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Anyarambhatla GR, Needham D. Enhancement of the phase transition permeability of DPPC liposomes by incorporation of MPPC: A new temperature-sensitive liposome for use with mild hyperthermia. Journal of Liposome Research. 1999;9(4):491–506. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gabizon AA, Barenholz Y, Bialer M. Prolongation of the Circulation Time of Doxorubicin Encapsulated in Liposomes Containing a Polyethylene Glycol-Derivatized Phospholipid - Pharmacokinetic Studies in Rodents and Dogs. Pharmaceutical Research. 1993;10(5):703–708. doi: 10.1023/a:1018907715905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kheirolomoom A, Dayton PA, Lum AFH, Little E, Paoli EE, Zheng HR, Ferrara KW. Acoustically-active microbubbles conjugated to liposomes: Characterization of a proposed drug delivery vehicle. Journal of Controlled Release. 2007;118(3):275–284. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2006.12.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kheirolomoom A, Ferrara KW. Cholesterol transport from liposomal delivery vehicles. Biomaterials. 2007;28(29):4311–4320. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2007.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nakata N, Kamidate T. Enhanced firefly bioluminescent assay of adenosine 5'-triphosphate using liposomes containing cationic cholesterols. Luminescence (Chichester) 2001;16(4):263–269. doi: 10.1002/bio.648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Borowsky AD, Namba R, Young LJT, Hunter KW, Hodgson JG, Tepper CG, McGoldrick ET, Muller WJ, Cardiff R, Gregg JP. Syngeneic mouse mammary carcinoma cell lines: Two closely related cell lines with divergent metastatic behavior. Clinical & Experimental Metastasis. 2005;22(1):47–58. doi: 10.1007/s10585-005-2908-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Seo JW, Zhang H, Kukis DL, Meares CF, Ferrara KW. A Novel Method to Label Preformed Liposomes with (CU)-C-64 for Positron Emission Tomography (PET) Imaging. Bioconjugate Chem. 2008;19(12):2577–2584. doi: 10.1021/bc8002937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Qin S, Seo JW, Zhang H, Qi J, Curry FR, Ferrara KW. An Imaging-Driven Model for Liposomal Stability and Circulation. Mol Pharm. 2009 Aug 28; doi: 10.1021/mp900122j. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rahman A, Carmichael D, Harris M, Roh JK. Comparative Pharmacokinetics of Free Doxorubicin and Doxorubicin Entrapped in Cardiolipin Liposomes. Cancer Research. 1986;46(5):2295–2299. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Harashima H, Tsuchihashi M, Iida S, Doi H, Kiwada H. Pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic modeling of antitumor agents encapsulated into liposomes. Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews. 1999;40(1–2):39–61. doi: 10.1016/s0169-409x(99)00039-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Segel IH. Enzyme Kinetics: Behavior and analysis of rapid equilibrium and steady-state enzyme systems. New York: John Wiley & Sons; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Stephens DN, Kruse DE, Ergun AS, Barnes S, Lu XM, Ferrara KW. Efficient array design for sonotherapy. Physics in Medicine and Biology. 2008;53(14):3943–3969. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/53/14/014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]