Abstract

Antibody-enzyme conjugate (AbE) has been widely studied for site-specific prodrug activation in tumors. The purpose of this study is to characterize the pharmacokinetics and tissue distribution of HuCC49ΔCH2-β-galactosidase conjugate. HuCC49ΔCH2 and β-galactosidase were chemically conjugated and injected into a LS 174T colon cancer xenograft model. A colorimetric assay was developed to quantify the HuCC49ΔCH2-β-galactosidase levels in plasma and tissues. The HuCC49ΔCH2-β-galactosidase conjugate distributed into tumor tissue as early as 6 hours with the tumor/blood ratio of 5. This favored distribution of conjugate activity in the tumor tissue was maintained up to 4 days post conjugate injection, while the conjugate was cleared rapidly from blood and other normal tissues (heart, spleen, lung, liver, kidney and stomach). At a high dose of 3000 U/kg, HuCC49ΔCH2-β-galactosidase conjugate saturated the antigen binding sites and yielded decreased tumor/normal tissue ratios compared to 1500 U/kg. These data suggest that HuCC49ΔCH2-β-galactosidase specifically target to the tumors to increase tumor selectivity.

Keywords: Biodistribution, ADEPT, HuCC49ΔCH2, antibody, pharmacokinetics

1. Introduction

One of the major challenges for the current cancer chemotherapy is the lack of specificity for the tumor tissues. Most anticancer drugs are designed to act on the fast proliferating cancer cells, whereas rapid proliferation is also the feature of some normal cells such as bone marrow, hair follicles, and intestinal epithelium, thus leading to unwanted side effects (Tietze and Krewer, 2009). A delicate dose regimen is usually required to balance drug’s efficacy and toxicity as well as to reduce drug resistance. To increase the efficacy and decrease the toxicity of the anticancer drugs, novel approaches would be desired to specifically deliver or activate the anticancer drugs in tumors while sparing the normal tissues.

A variety of targeted delivery or site-specific activation systems have been developed and tested in vitro and in vivo for their activity. Antibodies are of particular interest as tumor targeting moieties employing their innate high binding affinity to tumor associated antigens which are overexpressed on the surface of tumor cells or in the tumor interstitium. Antibodies have been used to deliver radioisotopes (such as 177Lu (Meredith et al., 2001), 131I (Baranowska-Kortylewicz et al., 2007)), toxins (such as ricin A chain (Frankel, 1985)) and chemotherapeutic agents (such as geldanamycin (Mandler et al., 2000)) to tumors (Stribbling et al., 1997; Senter and Springer, 2001). However, long retention time and poor extravasation and diffusion through the tumor of the antibody-drug conjugates might lead to non-specific tissue damage and limited therapeutic effect (Stribbling et al., 1997).

Therefore, a two step antibody directed enzyme prodrug therapy (ADEPT) strategy was proposed (Bagshawe, 1987; Bagshawe et al., 1988). In ADEPT, an antibody-enzyme conjugate is first administered to allow accumulation in the tumor tissue while it is cleared from the blood and normal tissues. Subsequently, a non-toxic prodrug is administered and is converted to active drug by the antibody-enzyme conjugate in the tumor tissue (Alderson et al., 2006). ADEPT strategy has following advantages: (1) ADEPT provides high specificity and limited toxicity through antibody targeting; (2) ADEPT exhibits amplification effect: one molecule of the tumor bound antibody-enzyme conjugate may catalyze the conversion of many molecules of prodrug into the active drug, which enables accumulation of active drugs in the tumor tissue (Springer and Niculescu-Duvaz, 1997); (3) ADEPT shows bystander effect: active drug is released extracellular and could diffuse to neighboring tumor cells, and thus eliminates the cancer cells (Cheng et al., 1999; Tietze and Krewer, 2009).

A key issue for the development of ADEPT system would be the selection of the appropriate antibody to act as targeting moiety which requires consideration of both specificity and immunogenicity. The clinical studies of the ADEPT system revealed that host immune response against the administered murine monoclonal antibodies limited the therapeutic effect (Sharma et al., 1992; Sharma et al., 2005). Thus humanized monoclonal antibodies are preferred in ADEPT to reduce immunogenicity.

We have applied monoclonal antibodies against tumor associated glycoprotein 72 (TAG-72) for tumor detection in colon cancer patients (Xiao et al., 2005; Fang et al., 2007). Anti-TAG-72 antibodies (murine B72.3, murine CC49 and humanized HuCC49ΔCH2) detected 77% to 89% of primary colorectal tumors (Nieroda et al., 1990; Cohen et al., 1991) and 78% to 97% of metastatic lesions (Bertsch et al., 1995; Arnold et al., 1998; Agnese et al., 2004; Xiao et al., 2005). Furthermore, these antibodies not only detect visible gross tumors but also clinically occult disease within lymph nodes in more than 70% of the cases (LaValle et al., 1997; Martin and Thurston, 1998; Sun et al., 2007), which are normally undetectable by traditional surgical exploration and pathological examination. The successful detection of additional occult tumors and the subsequent complete resection of the antibody-bound tissues significantly improved survival rates (Bertsch et al., 1995; Bertsch et al., 1996).

However, despite anti-TAG-72 antibodies detecting both visible gross and occult tumors, a clinical study with primary or recurrent colorectal cancer patients found that more than 50% tumors were unresectable (Ahn et al., 2003; Fuchs et al., 2003; Kabbinavar et al., 2003). In these patients, the anti-TAG-72 antibody was localized in the remaining tumor tissues after surgery, but the antibody itself did not offer therapeutic benefits.

Hence, we intend to take advantage of the tumor-bound antibody to integrate both intraoperative tumor detection for surgery and ADEPT strategy into one system with the same tumor targeting antibody. We hypothesize that HuCC49ΔCH2 (conjugated with enzyme) will target gross tumors, occult tumors, and lymph nodes for tumor detection. In cases where surgery is impossible, we will utilize the tumor-localized antibody-enzyme conjugate for site-specific activation of inactive prodrug in the tumor.

In our previous study, we chemically conjugated HuCC49ΔCH2 and β-galactosidase for the geldanamycin (GA) prodrug activation. The conjugate was confirmed to activate the GA prodrug in cell culture, reducing the prodrug IC50 more than 25-fold (Cheng et al., 2005; Fang et al., 2006). The aims of this study are to investigate the pharmacokinetics and biodistribution of HuCC49ΔCH2-β-galactosidase conjugates in the LS174T colorectal cancer xenograft model.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemicals and Reagents

Beta-galactosidase was purchased from Roche (Basel, Switzerland, catalog number 10567779001). ONPG (o-Nitrophenyl-β-D-galactopyranoside) was from Pierce (Rockland, IL, USA catalog number 34055). The nude mice (6–8 weeks age) were purchased from Charles River (MA, USA). The colon cancer cell line LS174T was from ATCC (Manassas, VA, USA).

2.2. Conjugation of HuCC49ΔCH2 to β-galactosidase

The chemical conjugation method for antibody and enzyme was described previously (Fang et al., 2006). Briefly, four milligram β-galactosidase was combined with 0.05 mg of SATA in 500 μL PBS buffer and stirred for 1 hour at room temperature. Mixed 1.0 mL modified enzyme solution with 100 μL hydroxylamine deacetylation solution followed by incubation at room temperature for 2 hours. Five mgs HuCC49ΔCH2 were combined with 0.3 mg MBS (m-maleimidobenzoyl-N-hydroxysuccinimide ester, Pierce, Rockland, IL, USA) in 500 μl PBS buffer for 1 hour. The modified enzyme was mixed with the modified antibody. The resulting mixture was then adjusted to pH7.4. The reaction was kept under anaerobic condition (under N2) and stirring at room temperature for 2 hours. The concentrated conjugate was purified from aggregate, unreacted enzyme or antibody, and small molecules by FPLC chromatography on Sephadex G-150 column. One major peak was obtained from FPLC. The estimated purity is more than 90% (Cheng et al., 2005; Fang et al., 2006).

2.3. Western blot analysis

Cancer tissues and normal tissues were homogenized in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) with 1% protease inhibitor cocktail (P8340, Sigma). Protein concentration was determined using BCA protein assay method (PIERCE). The homogenates were incubated with 2x SDS loading buffer and boiled for 5 minutes. Then 30 μg of protein was subjected to electrophoresis in 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gels (Bio-Rad). The protein was transferred to nitrocellulose membrane and incubated with HuCC49ΔCH2 antibody (1:1000 diluted in 5% milk Tris-buffered saline with 0.1% tween-20 (TBS-T)) at room temperature for 1 hr. The membrane was washed 4 times with TBS-T for 15 minutes, and then incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody (1:2000 diluted in 5% milk Tris-buffered saline with 0.1% tween-20 (TBS-T), Jackson ImmunoResearch Labs, West Grove, PA) for 1 hr at room temperature. An enhanced chemiluminescence system ECL (Amersham) was used to detect TAG-72 expression level.

2.4. Biodistribution of HuCC49ΔCH2-β-galactosidase in the LS174T xenograft mouse model

LS174T tumor monolayer cultures and histocultures were maintained in DMEM, at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2. All culture media was supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 2 mM L-glutamine, 0.1 mM non-essential amino acids, 90 μg/mL gentamicin, and 90 μg/ml cefatoxime. LS174T cells were harvested from subconfluent cultures using EDTA/trypsin and injected subcutaneously (s.c.) into the flanks on both sides of a mouse to generate the xenograft model in female athymic nu/nu mice (nu/nu, 5-6 weeks of age, n=5–6). After 7–9 days, animals bearing tumors that reached a diameter of 5-6 mm were used for experiments. Animals were administered HuCC49ΔCH2-β-galactosidase conjugates (1000 U/kg, 1500 U/kg or 3000 U/kg) through tail veil, while control mice received a PBS injection. At indicated time points, the mice in each group were sacrificed to collect tumor and normal organs for analysis of enzyme activity as described below. The removed tissues were rinsed in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and weighed, and homogenized in PBS to obtain a 5% (w/v) homogenate for activity measurement of antibody-enzyme conjugates.

2.5. Measurement of HuCC49ΔCH2 and β-galactosidase in blood and tissue homogenates

An aliquot (100μl) of homogenate or plasma was incubated with 100 μl of 3 mM ONPG (o-Nitrophenyl-β-D-galactopyranoside), 10 mM MgCl2, 0.1 mM 2-mercaptoethanol in PBS for 30 minutes. At the same time, 100 μl tissue homogenate aliquots were incubated with 100 μl PBS and used as background control. The reaction was stopped with 5μL of 1M sodium carbonate. The absorbance was measured at 405–410 nm. The background reading was deducted from each corresponding tissue or tumor samples. The tissue sample from the control mice were treated in the same way.

2.6. Pharmacokinetic analysis

Pharmacokinetic analysis of the blood conjugate concentration – time profile was carried out by Winnolin software (Pharsight, Mountain View, CA). Data were fitted to a two compartment IV bolus model with equation as C(t) = Ae−αt + Be−βt.

2.7. Staining of HuCC49ΔCH2-β-galactosidase in tumor tissues

The staining method was previously reported (Cao et al., 2007). Tumors were excised and embedded in Tissue-Tek OCT (Sakura Finetechnical, Torrance, CA), frozen at −80 °C, and sectioned into 10-μm slices. All slides were quenched for 5 minutes in a 3% hydrogen peroxide solution in water to block for endogenous peroxidase. Tissues were antigen retrieved using citrate buffer in a vegetable steamer. The frozen sections were incubated with anti-human IgG antibodies (staining for HuCC49ΔCH2) for 1 hour. Slides were then placed on a Dako Autostainer immunostaining system (Carpinteria, CA). The detection system used was a labeled Streptavidin-Biotin Complex. This method is based on the consecutive application of 1) a primary antibody against the antigen to be localized; 2) biotinylated linked secondary antibody against primary antibody; 3) peroxidase conjugated streptavidin to bind to biotin; and 4) enzyme substrate chromogen (DAB) for detection. Tissues were avidin and biotin blocked prior to the application of the biotinylated secondary antibody. Slides were then counterstained in Richard Allen hematoxylin, dehyrated through graded ethanol solutions. The staining was examined under a microscope (Zeiss Axiovert).

3. Results

3.1. TAG-72 is expressed in xenograft tumors and human colon cancer tissues

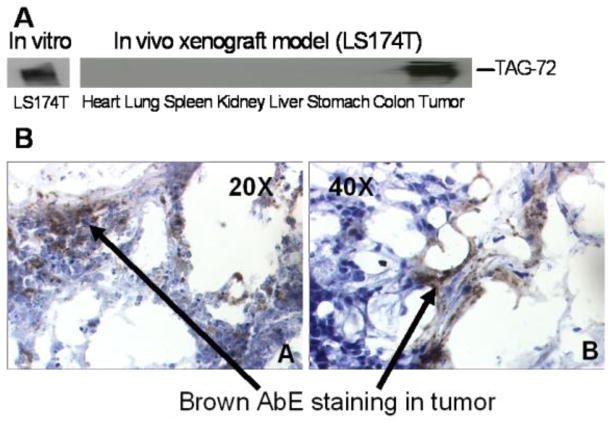

We used western blotting to confirm the expression levels of TAG-72 in a mouse xenograft model (Fig 1A). Only xenograft tumors (LS-174T) expressed high levels of TAG-72, while all other normal organs did not show detectable levels of TAG-72. Fig 1B shows HuCC49ΔCH2-β-galactosidase conjugates accumulate in the tumors after antibody-enzyme in LS174T xenograft for 3 days. This data indicates the conjugation of the enzyme β-galactosidase to HuCC49ΔCH2 did not affect the antigen binding affinity of HuCC49ΔCH2. This is consistent with our previous report that antibody-enzyme conjugate specifically bind to TAG-72-positive cancer cells (LS174T) and human colon cancer tissues, while not binding to TAG-72-negative cancer cells HT-28, SW-620 and human normal tissues (Cheng et al., 2005; Fang et al., 2006).

Fig 1.

A, The TAG-72 expression was detected using western blot in colorectal cancer cells (LS174T) in vitro, normal tissues and xenograft tumors in vivo. B, Immunostaining of HuCC49ΔCH2-β-galactosidase conjugates in the LS174T xenograft tumors 3 days post antibody-enzyme administration. 1, 20X; 2, 40X.

3.2. Assay development to evaluate the antibody-enzyme conjugate concentrations in blood and the tissue homogenates

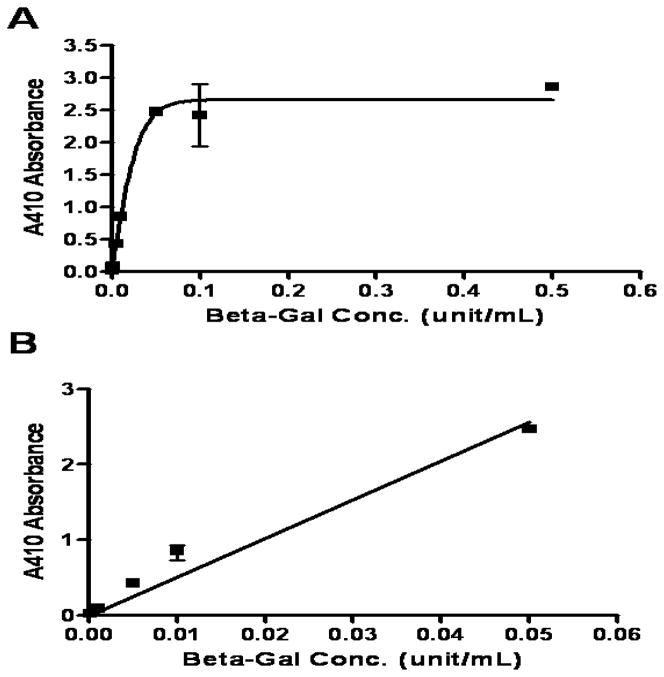

To assess the concentration and biodistribution of antibody-enzyme conjugates, two different methods are normally used, one is to assess the concentration of antibody, and another one is to assess the enzyme activity. Since enzyme activity would better represent the activity of the conjugates to convert the prodrug to active drug molecules, we applied a colorimetric assay to examine the enzyme activity of the conjugates in blood and the tissue homogenates. ONPG appeared as a good substrate for β-galactosidase (BioTek, 2001), since it was shown to be converted by the β-galactosidase to a colored product and exhibited high absorbance at 410 nm. The absorbance is proportional to enzyme concentration when substrate is sufficiently supplied. As shown in Figure 2, when β-galactosidase concentration in the homogenate was under 0.05 U/mL, an excellent linear regression was obtained: Absorbance=51.25 × Concentration (R2=0.9796). However, when β-galactosidase concentration was higher than 0.05 U/mL, the absorbance reached the plateau. Therefore, to better evaluate the conjugate concentration in the tissue homogenates, the tissue homogenates were diluted before the assay was performed in the linear range.

Figure 2.

Standard Curve of colorimetric assay of enzymatic activity of β-galactosidase.

3.3. Pharmacokinetic profile of HuCC49ΔCH2-β-galactosidase following iv bolus administration

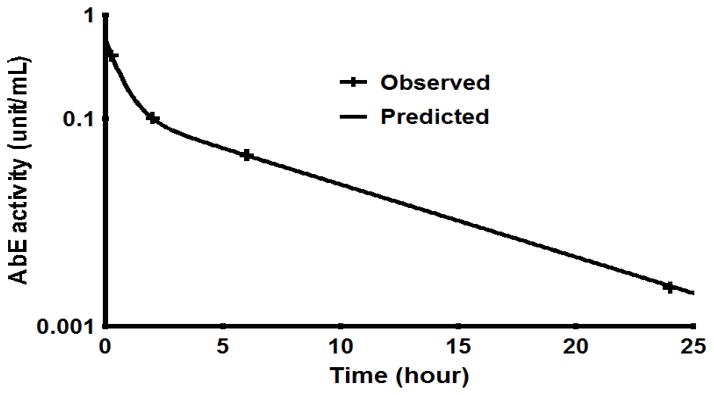

Figure 3 shows the semi-logarithmic blood concentration – time profile of AbE conjugate following iv bolus of 1000 U/kg AbE conjugate. At 24 hr, the AbE conjugate activity was under 0.002 U/mL (below 0.5% of AbE activity at 0.25 hr post administration). Pharmacokinetic analysis was carried out by Winnolin. The data were well fitted to a two compartment model, indicating two phase disposition. The pharmacokinetic parameters derived from the concentration time profile are shown in Table 1. The T1/2α and T1/2β half-lives were determined as 0.42 and 4.31 hr, respectively. In a previous report, Milenic et al. conducted pharmacokinetic analysis of radioimmunoconjugates of HuCC49ΔCH2 radiolabeled with 177Lu using different ligands and found that the T1/2α and T1/2β half-lives were ranging from 0.10 to 0.22 hr and from 4.5 to 6.0 hr respectively for different conjugates (Milenic et al., 2002), which are comparable to the T1/2α and T1/2β half-lives (0.42 and 4.31 hr, respectively) of the HuCC49ΔCH2-β-galactosidase conjugate in our study.

Figure 3.

Plasma concentration vs. time of HuCC49ΔCH2-β-galactosidase conjugate activity after i.v. bolus administration (1000 units/kg) in the LS174T xenograft.

Table 1.

Summary of pharmacokinetic parameters of HuCC49ΔCH2-β-galactosidase following iv administration (means ± SEM).

| PK Parameters | Estimated Values |

|---|---|

| AUC (U/mL·hr) | 0.99 ± 0.08 |

| α (U/mL) | 0.44 ± 0.01 |

| t1/2α (hr) | 0.42 ± 0.12 |

| β (U/mL) | 0.12 ± 0.03 |

| t1/2β; (hr) | 4.31 ± 1.18 |

| CL (mL/hr) | 22.14 ± 1.74 |

| Vss (mL) | 104.06 ± 14.28 |

3.4. Tissue distribution of HuCC49ΔCH2-β-galactosidase

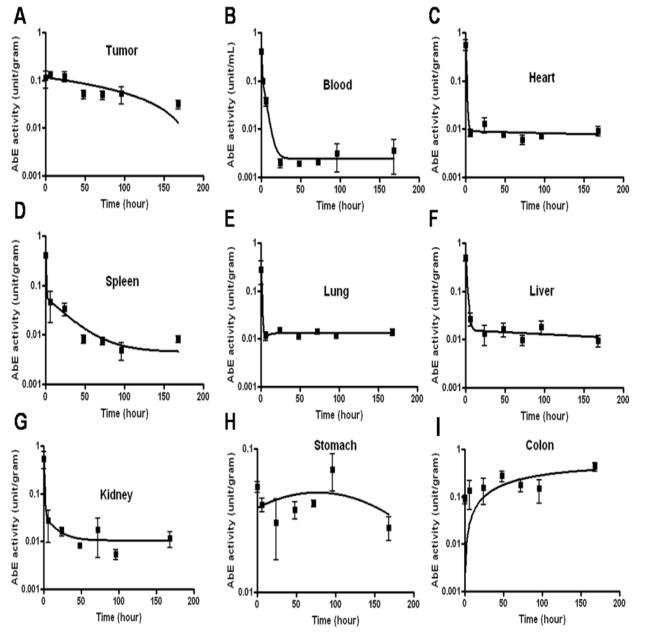

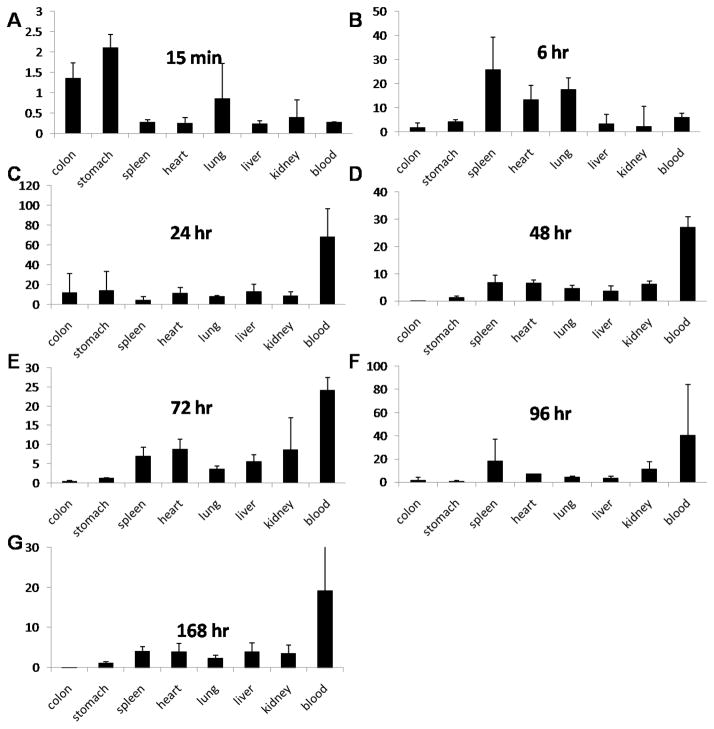

We next tested the distribution of the antibody-enzyme conjugate in a xenograft mouse model to test whether the conjugate was able to specifically localize to the tumor tissues. In this study, antibody-enzyme conjugates (AbE) (1000 U/kg) were injected into the mice through the tail vein. At the indicated time points, the mice were sacrificed to collect tumor and normal tissues. The conjugate activities in individual tissues/organs were measured at various time points post administration in nude mice bearing the LS174T human colon cancer xenograft. The selected time points were the following: 15 minutes, 6 hours, 1, 2, 3, 4 and 7 days. The conjugate activity in tumor tissue was around 0.2 U/gram as early as 15 minutes and maintained this level during the first day. The decay of the conjugate activity in the tumor tissue was very slow and the conjugate activity was maintained around 0.1 U/gram up to 4 days. Seven days post conjugate injection, the conjugate activity dropped under 0.05 U/gram (Figure 4A).

Figure 4.

HuCC49ΔCH2-β-galactosidase conjugate activity (U/gram or U/mL) in tumor, plasma and normal tissues at various time points post injection of the conjugate (1000 units/kg)

Interestingly, the conjugate was cleared from blood circulation rapidly. Total of 1000 U/kilogram conjugate dose showed a plasma conjugate activity of 0.4 U/mL at 15 minutes post injection. The conjugate activity was detected to be under 0.1U/mL plasma as early as 2 hours. After 24 hours, the conjugate activity was almost undetectable (under 0.002 U/mL, Figure 4B). For normal tissues, such as heart, spleen, lung, liver, kidney and stomach, the initial conjugate activity in the tissues were 0.3 to 0.6 U/gram 15 minutes after injection. Similarly, the conjugate activity decayed rapidly in these tissues and the activity dropped under 0.05 U/gram after 6 hours (Figure 4C to 4L). The initial conjugate activity at 15 minutes in the colon tissue was relatively low (0.1 U/gram) compared to other normal tissues (around 0.3 to 0.6 U/gram); however, the conjugate activity in the colon was sustained and increased to 0.4 U/gram at 7 days post injection, while other tissues’ conjugate activity diminished to the minimal level.

Figure 5 shows the ratios of the conjugate concentration in the tumor to that in the normal tissues. The conjugate exhibited excellent retention in tumor and fast clearance from the other tissues, with tumor: normal tissue (stomach, spleen, heart, lung, liver, kidney, and blood exception of colon) ratios around 5 to 100-fold after 6 hours (Figure 5). These results indicate that the antibody-enzyme conjugate was able to specifically target the tumor tissues in vivo.

Figure 5.

Tumor: normal tissue ratios of HuCC49ΔCH2-β-galactosidase conjugate at various time points post conjugate injection (1000 units/kg).

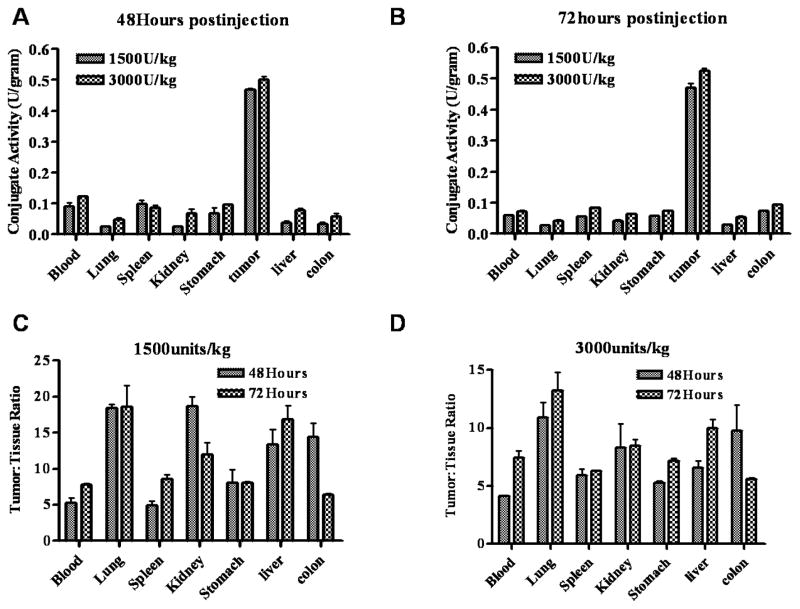

3.5. Tumor tissue antigen binding sites were saturated by higher doses of HuCC49ΔCH2-β-galactosidase conjugate

To further illustrate the dose response on the conjugate concentration and tissue distribution, we administered two higher doses (1500 and 3000 U/kg) to the xenograft mice and investigated conjugate’s biodistribution. As shown in figure 6A and 6B, a dose of 1500 U/kg conjugate exhibited a higher local concentration in the tumors (0.5 U/gram) compared to that of 1000 U/Kg dose (0.2 U/gram), however, a higher dose of 3000 U/kg conjugate did not increase the concentration in the tumor significantly. This lack of increase of conjugate concentration in the tumor is probably due to the saturation of antigen binding sites for doses beyond 1500 U/kg. The ratios of tumor to normal tissues (blood, lung, spleen, kidney, stomach, liver and blood) are 4.2 to 20-fold for the dose of 1500 U/kg at 48 and 72 hours post conjugate injection. Although the higher dose (3000 U/kg) did show slightly higher levels of AbE in tumors, blood, and normal tissues, it showed similar or decreased ratios of tumor to normal tissues at both 48 and 72 hours, which is probably due to the saturation of antigen binding in the tumor tissues by the higher dose.

Fig 6.

Biodistribution of HuCC49ΔCH2-β-galactosidase activity in xenograft mice. Groups of 4–5 mice received 1500 or 3000 units/kg of conjugates. At 48 and 72 hours, the animals were sacrificed and the enzymatic activity of conjugates in tumors and normal organs was determined as described in method section (A and B). The tumor: tissue ratios are presented in C and D.

4. Discussion

We had previously studied anti-TAG-72 antibodies for tumor detection to improve surgical precision. For unresectable cancers, utilization of the tumor-localized antibody-enzyme conjugate for site-specific activation of inactive prodrug in the tumor is a complementary treatment option. This antibody-directed enzyme prodrug therapy (ADEPT) strategy takes advantage of the high specificity and affinity of antibody-antigen reaction to deliver the drug activation enzyme (using tumor-targeting antibody) to the tumor sites specifically. And then a non-toxic prodrug is administered systemically and is converted to the active drug with high local concentration in tumors to achieve more specific tumor targeting. Meanwhile, the prodrug remains inactive (without drug-activating enzyme) in normal tissues and thus decreasing its nonspecific toxicity.

However, due to the complexity of the ADEPT system, many difficulties and concerns exist. The most raised concerns are the following: (A) whether sufficient amount of antibody-enzyme conjugates (AbE) can specifically target tumor tissues with minimal background in normal tissues; (B) whether the antibody-enzyme conjugate is enzymatically efficient to activate prodrug molecules. To answer these questions, the current biodistribution study was carried out. First, we developed a simple and sensitive colorimetric assay to measure enzymatic activity of conjugates in mouse tissue homogenates. In the literature, antibody-enzyme conjugate localization in tumors is examined by either detecting antibody with radiolabeling or by measuring enzyme activity with ex vivo enzymatic assay. In considering selective drug activation aspect, the enzyme activity measurement is a better way for determining the distribution of antibody-enzyme conjugate than radiolabeling approach, because the pretargeted enzyme will convert prodrug to active drug, not the antibody itself. In addition, some inconsistency was observed between antibody distribution and enzyme activity distribution (Francis et al., 2004). In a previous similar study, MTX was used as the substrate and the cleaved product by conjugate, DAMPA, was measured by HPLC (Stribbling et al., 1997). Compared to this current colorimetric method, the HPLC approach is more costly and time-consuming. In addition, the colorimetric method is more sensitive. AbE conjugate concentration as low as 0.002 U/mL can be accurately detected.

As indicated in previous studies, the efficacy of ADEPT therapy is dependent on the high localized concentration of AbE conjugate at tumor sites (Stribbling et al., 1997). The challenge in using ADEPT for clinical studies is also attributed to insufficient tumor selective distribution of antibody-enzyme conjugates (AbE). Thus it is critical to achieve high tumor/plasma or normal tissue ratios of antibody-enzyme conjugates. The primary objective of this study is to find the most optimal time window for prodrug injection. A 1000 U/kg AbE conjugate was injected into mice through the tail vein. Subsequent pharmacokinetic and biodistribution studies revealed that the conjugate was cleared from blood circulation and normal tissues rapidly. The conjugate concentration in the plasma was under 0.1 U/mL in 2 hours. As a result, the conjugate exhibited short half-lives with T1/2α and T1/2β half-lives determined as 0.42 and 4.31 hr, respectively, which were consistent with the findings in the literature (Milenic et al., 2002). Similar rapid decay was observed in other normal tissues, such as heart, spleen, lung, liver, kidney and stomach. One day after conjugate injection, the conjugate concentration dropped under 0.05 U/gram for the blood and other normal tissues. On the other hand, the tumor conjugate concentration remained at 0.2 U/gram for the first day and maintained at 0.1 U/gram up to 4 days. The resulting tumor/plasma or normal tissue ratios of conjugate activity are the highest at 4 days post conjugate injection. Thus, 4 days might be an optimal time to start the prodrug injection. In previous study, we have developed a predictive physiologically based pharmacokinetic (PBPK) model to explore optimal therapeutic regimens for ADEPT in vivo. The model suggested that the AbE reach highest levels in tumors at 4 days when AbE concentration in tumors was used as criteria to select dose interval. In the previous modeling, when the AUC ratio of active drug in tumor vs. plasma was used as selection criteria, the optimal dosing interval between AbE and prodrug administration is between 3 and 5 days (Fang and Sun, 2008). Although the model predicted that the 3-day dosing interval between AbE and prodrug gave a lower AUC ratio of active drug in tumor vs. plasma compared to 5-day dosing interval, the difference is not significant. The current data is in agreement with previous modeling.

Furthermore, the dose-response of antibody-enzyme conjugates (AbE) was also studied for its own concentration and tissue distribution. A single dose of 1500 U/kg AbE resulted in much higher conjugate concentrations in tumor compared to the 1000 U/kg dose, whereas a dose of 3000 U/kg did not increase the conjugate concentration in the tumor significantly. These data suggested that a higher dose than 1500 U/gram probably would result in antigen binding saturation in the tumor. Therefore, a dose of 1500 U/kg would be the best dose regimen as it increases the conjugate concentration in tumor substantially compared to a dose of 1000 U/kg, while minimizing the conjugate concentration in normal tissues compared to a dose of 3000 U/kg.

Acknowledgments

This study is partially supported by NIH funding RO1 CA 120023, University of Michigan Cancer Center Research Grant (Munn), University of Michigan Cancer Center Core Grant to DS.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Agnese DM, Abdessalam SF, Burak WE, Jr, Arnold MW, Soble D, Hinkle GH, Young D, Khazaeli MB, Martin EW., Jr Pilot study using a humanized CC49 monoclonal antibody (HuCC49DeltaCH2) to localize recurrent colorectal carcinoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2004;11:197–202. doi: 10.1245/aso.2004.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahn JH, Kim TW, Lee JH, Min YJ, Kim JG, Kim JC, Yu CS, Kim WK, Kang YK, Lee JS. Oral doxifluridine plus leucovorin in metastatic colorectal cancer: randomized phase II trial with intravenous 5-fluorouracil plus leucovorin. Am J Clin Oncol. 2003;26:98–102. doi: 10.1097/01.COC.0000017089.68491.1F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alderson RF, Toki BE, Roberge M, Geng W, Basler J, Chin R, Liu A, Ueda R, Hodges D, Escandon E, Chen T, Kanavarioti T, Babe L, Senter PD, Fox JA, Schellenberger V. Characterization of a CC49-based single-chain fragment-beta-lactamase fusion protein for antibody-directed enzyme prodrug therapy (ADEPT) Bioconjug Chem. 2006;17:410–8. doi: 10.1021/bc0503521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnold MW, Young DM, Hitchcock CL, Barbera-Guillem E, Nieroda C, Martin EW., Jr Staging of colorectal cancer: biology vs. morphology. Dis Colon Rectum. 1998;41:1482–7. doi: 10.1007/BF02237292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagshawe KD. Antibody directed enzymes revive anti-cancer prodrugs concept. Br J Cancer. 1987;56:531–2. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1987.237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagshawe KD, Springer CJ, Searle F, Antoniw P, Sharma SK, Melton RG, Sherwood RF. A cytotoxic agent can be generated selectively at cancer sites. Br J Cancer. 1988;58:700–3. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1988.293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baranowska-Kortylewicz J, Abe M, Nearman J, Enke CA. Emerging role of platelet-derived growth factor receptor-beta inhibition in radioimmunotherapy of experimental pancreatic cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:299–306. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-1702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertsch DJ, Burak WE, Jr, Young DC, Arnold MW, Martin EW., Jr Radioimmunoguided Surgery system improves survival for patients with recurrent colorectal cancer. Surgery. 1995;118:634–8. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6060(05)80029-7. discussion 638–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertsch DJ, Burak WE, Jr, Young DC, Arnold MW, Martin EW., Jr Radioimmunoguided surgery for colorectal cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 1996;3:310–6. doi: 10.1007/BF02306288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BioTek. 2001 http://www.biotek.com/products/tech_res_detail.php?id=52.

- Cao X, Fang L, Gibbs S, Huang Y, Dai Z, Wen P, Zheng X, Sadee W, Sun D. Glucose uptake inhibitor sensitizes cancer cells to daunorubicin and overcomes drug resistance in hypoxia. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2007;59:495–505. doi: 10.1007/s00280-006-0291-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng H, Cao X, Xian M, Fang L, Cai TB, Ji JJ, Tunac JB, Sun D, Wang PG. Synthesis and enzyme-specific activation of carbohydrate-geldanamycin conjugates with potent anticancer activity. J Med Chem. 2005;48:645–52. doi: 10.1021/jm049693a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng TL, Wei SL, Chen BM, Chern JW, Wu MF, Liu PW, Roffler SR. Bystander killing of tumour cells by antibody-targeted enzymatic activation of a glucuronide prodrug. Br J Cancer. 1999;79:1378–85. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6690221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen AM, Martin EW, Jr, Lavery I, Daly J, Sardi A, Aitken D, Bland K, Mojzisik C, Hinkle G. Radioimmunoguided surgery using iodine 125 B72.3 in patients with colorectal cancer. Arch Surg. 1991;126:349–52. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1991.01410270095015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang L, Battisti RF, Cheng H, Reigan P, Xin Y, Shen J, Ross D, Chan KK, Martin EW, Jr, Wang PG, Sun D. Enzyme specific activation of benzoquinone ansamycin prodrugs using HuCC49DeltaCH2-beta-galactosidase conjugates. J Med Chem. 2006;49:6290–7. doi: 10.1021/jm060647f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang L, Holford NH, Hinkle G, Cao X, Xiao JJ, Bloomston M, Gibbs S, Saif OH, Dalton JT, Chan KK, Schlom J, Martin EW, Jr, Sun D. Population pharmacokinetics of humanized monoclonal antibody HuCC49deltaCH2 and murine antibody CC49 in colorectal cancer patients. J Clin Pharmacol. 2007;47:227–37. doi: 10.1177/0091270006293758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang L, Sun D. Predictive physiologically based pharmacokinetic model for antibody-directed enzyme prodrug therapy. Drug Metab Dispos. 2008;36:1153–65. doi: 10.1124/dmd.107.019182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francis RJ, Mather SJ, Chester K, Sharma SK, Bhatia J, Pedley RB, Waibel R, Green AJ, Begent RH. Radiolabelling of glycosylated MFE-23::CPG2 fusion protein (MFECP1) with 99mTc for quantitation of tumour antibody-enzyme localisation in antibody-directed enzyme pro-drug therapy (ADEPT) Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2004;31:1090–6. doi: 10.1007/s00259-004-1474-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frankel AE. Antibody-toxin hybrids: a clinical review of their use. J Biol Response Mod. 1985;4:437–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs CS, Moore MR, Harker G, Villa L, Rinaldi D, Hecht JR. Phase III comparison of two irinotecan dosing regimens in second-line therapy of metastatic colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:807–14. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.08.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kabbinavar F, Hurwitz HI, Fehrenbacher L, Meropol NJ, Novotny WF, Lieberman G, Griffing S, Bergsland E. Phase II, randomized trial comparing bevacizumab plus fluorouracil (FU)/leucovorin (LV) with FU/LV alone in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:60–5. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.10.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaValle GJ, Martinez DA, Sobel D, DeYoung B, Martin EW., Jr Assessment of disseminated pancreatic cancer: a comparison of traditional exploratory laparotomy and radioimmunoguided surgery. Surgery. 1997;122:867–71. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6060(97)90326-3. discussion 871–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandler R, Wu C, Sausville EA, Roettinger AJ, Newman DJ, Ho DK, King CR, Yang D, Lippman ME, Landolfi NF, Dadachova E, Brechbiel MW, Waldmann TA. Immunoconjugates of geldanamycin and anti-HER2 monoclonal antibodies: antiproliferative activity on human breast carcinoma cell lines. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92:1573–81. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.19.1573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin EW, Jr, Thurston MO. Intraoperative radioimmunodetection. Semin Surg Oncol. 1998;15:205–8. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-2388(199812)15:4<205::aid-ssu2>3.0.co;2-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meredith RF, Alvarez RD, Partridge EE, Khazaeli MB, Lin CY, Macey DJ, Austin JM, Jr, Kilgore LC, Grizzle WE, Schlom J, LoBuglio AF. Intraperitoneal radioimmunochemotherapy of ovarian cancer: a phase I study. Cancer Biother Radiopharm. 2001;16:305–15. doi: 10.1089/108497801753131381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milenic DE, Garmestani K, Chappell LL, Dadachova E, Yordanov A, Ma D, Schlom J, Brechbiel MW. In vivo comparison of macrocyclic and acyclic ligands for radiolabeling of monoclonal antibodies with 177Lu for radioimmunotherapeutic applications. Nucl Med Biol. 2002;29:431–42. doi: 10.1016/s0969-8051(02)00294-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nieroda CA, Mojzisik C, Sardi A, Ferrara PJ, Hinkle G, Thurston MO, Martin EW., Jr Radioimmunoguided surgery in primary colon cancer. Cancer Detect Prev. 1990;14:651–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senter PD, Springer CJ. Selective activation of anticancer prodrugs by monoclonal antibody-enzyme conjugates. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2001;53:247–64. doi: 10.1016/s0169-409x(01)00206-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma SK, Bagshawe KD, Begent RH. Advances in antibody-directed enzyme prodrug therapy. Curr Opin Investig Drugs. 2005;6:611–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma SK, Bagshawe KD, Melton RG, Sherwood RF. Human immune response to monoclonal antibody–enzyme conjugates in ADEPT pilot clinical trial. Cell Biophys. 1992;21:109–20. doi: 10.1007/BF02789482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Springer CJ, Niculescu-Duvaz II. Antibody-directed enzyme prodrug therapy (ADEPT): a review. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 1997;26:151–172. doi: 10.1016/s0169-409x(97)00032-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stribbling SM, Martin J, Pedley RB, Boden JA, Sharma SK, Springer CJ. Biodistribution of an antibody-enzyme conjugate for antibody-directed enzyme prodrug therapy in nude mice bearing a human colon adenocarcinoma xenograft. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 1997;40:277–84. doi: 10.1007/s002800050659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun D, Bloomston M, Hinkle G, Al-Saif OH, Hall NC, Povoski SP, Arnold MW, Martin EW., Jr Radioimmunoguided surgery (RIGS), PET/CT image-guided surgery, and fluorescence image-guided surgery: past, present, and future. J Surg Oncol. 2007;96:297–308. doi: 10.1002/jso.20869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tietze LF, Krewer B. Antibody-directed enzyme prodrug therapy: a promising approach for a selective treatment of cancer based on prodrugs and monoclonal antibodies. Chem Biol Drug Des. 2009;74:205–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-0285.2009.00856.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao J, Horst S, Hinkle G, Cao X, Kocak E, Fang J, Young D, Khazaeli M, Agnese D, Sun D, Martin E., Jr Pharmacokinetics and clinical evaluation of 125I-radiolabeled humanized CC49 monoclonal antibody (HuCC49deltaC(H)2) in recurrent and metastatic colorectal cancer patients. Cancer Biother Radiopharm. 2005;20:16–26. doi: 10.1089/cbr.2005.20.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]