Abstract

Acquired T-cell immunity is central for protection against infection. However, the immunological consequences of exposing memory T cells to high antigen loads during acute and persistent infection with systemic pathogens are poorly understood. We investigated this using infection with Anaplasma marginale, a ruminant pathogen that replicates to levels of 109 bacteria per ml of blood during acute infection and maintains mean bacteremia levels of 106 per ml during long-term persistent infection. We established that immunization-induced antigen-specific peripheral blood CD4+ T cell responses were rapidly and permanently lost following infection. To determine whether these T cells were anergic, sequestered in the spleen, or physically deleted from peripheral blood, CD4+ T lymphocytes from the peripheral blood specific for major surface protein (MSP)1a T-cell epitope were enumerated by DRB3*1101 tetramer staining and FACS analysis throughout the course of immunization and challenge. Immunization induced significant epitope-specific T lymphocyte responses that rapidly declined near peak bacteremia to background levels. Concomitantly, the mean frequency of tetramer+ CD4+ cells decreased rapidly from 0.025% before challenge to a pre-immunization level of 0.0003% of CD4+ T cells. Low frequencies of tetramer+ CD4+ T cells in spleen, liver, and inguinal lymph nodes sampled 9-12 weeks post-challenge were consistent with undetectable or unsustainable antigen-specific responses and the lack of T-cell sequestration. Thus, infection of cattle with A. marginale leads to the rapid loss of antigen-specific T cells and immunologic memory, which may be a strategy for this pathogen to modulate the immune response and persist.

Keywords: Other Animals, T Cells, Bacterial, Vaccination

Introduction

Pathogens that cause chronic infection have evolved many different strategies to persist in an immunocompetent host, which involve subversion or evasion of host innate or acquired immune responses (1-4). Continual exposure to high antigen load during persistent viral infection can lead to induction of regulatory T cells that suppress protective effector T cells, and to a poorly understood progressive dysfunction whereby T cells lose effector function in response to antigen, and are eventually deleted (4, 5). Furthermore, with certain persistent viral infections, such as hepatitis C virus, antigen-specific T cells can be compartmentalized to the liver (5). There are very few examples in the literature of how bacteria block acquired immune responses (reviewed in ref. 2 and 3), and specifically the consequences of high antigen load during persistent infection with blood-borne bacterial or protozoal pathogens such as Anaplasma, Borrelia, and Trypanosoma on antigen-specific memory and effector T cell responses have not been well characterized.

Anaplasma marginale is a tick-borne, intra-erythrocytic rickettsial pathogen that causes significant morbidity and mortality, and life-long persistent infection in ruminants. Notably, naïve cattle infected with A. marginale develop high levels of bacteremia, reaching 109 bacteria per ml of blood, within two to five weeks post-infection. The infection results in anemia, abortion, and mortality as high as 30%, but cattle that survive acute disease remain persistently infected for life with cyclically peaking, but subclinical levels of bacteremia averaging 106 bacteria per ml of blood (6, 7). Persistence is due, at least in part, to extensive antigenic variation in immunodominant and abundant major surface protein (MSP2)2 and MSP3 (8). Antigenic variation in MSP2, which is rich in T and B lymphocyte epitopes, allows the organism to continually escape specific adaptive immune responses (9-13).

In a previous study, we unexpectedly observed the rapid loss of immunization-induced MSP2-specific CD4+ T lymphocyte responses from peripheral blood following A. marginale challenge (13). Proliferation and IFN-γ responses disappeared coincident with peak bacteremia, and remained undetectable for up to one year, when the study was terminated. In contrast, responses to unrelated Clostridium sp. vaccine antigen administered prior to MSP2 immunization, remained intact throughout the course of the study (13). This rapid loss of antigen-specific T-cell responses following infection contradicts the paradigm that once established, memory CD4+ T cells rapidly expand and execute effector functions upon infection. Furthermore, the modulation of specific host immunity by high antigen load during infection may represent an important mechanism to facilitate persistent infection by A. marginale. Whether high antigen load drives antigen-specific cells to physical deletion via activation induced cell death, to anergy from exposure of specific-T cells to antigenically variant epitopes (14, 15), or to sequestration in peripheral lymphoid tissues, such as the spleen, is unknown.

To distinguish among these possibilities, and to determine if ablation of the pre-existing immune response following infection occurs with a non-variant immunogen, the present study tracked antigen-specific CD4+ T lymphocytes in calves immunized with a conserved T cell epitope from A. marginale MSP1a, peptide F2-5 (16, 17), before and after homologous strain challenge. F2-5-specific CD4+ T cell responses were measured and specific T cells were enumerated by analyzing CD4+ T lymphocytes stained with a bovine major histocompatibility (MHC) class II tetramer linked to the F2-5B peptide epitope (18). The results are consistent with an A. marginale-induced rapid death of antigen-specific CD4+ T cells that results in a loss of functional memory and, more broadly, may represent an important means for persistence of this pathogen in the immunocompetent host.

Materials and Methods

Cattle

Holstein calves serologically negative for A. marginale received Vision 7® killed Clostridium spp. vaccine (Intervet) prior to the start of the study. All calves were heterozygous for the MHC class II DRB3*1101 gene haplotype, which optimally presents the MSP1a F2-5 T-cell epitope GGVSYNDGNASAARSVLETLAGHVDALGIS (16, 19). Calves were immunized intradermally as described with the mammalian VR-1055 vector encoding the DRB3*1101-restricted 30-mer F2-5 epitope (17). Control calves were inoculated intradermally with empty vector. All calves were boosted on day 105 post-immunization with 20 μg MSP1a F2-5 peptide in alum (Pierce) diluted in PBS pH 7.2, and administered subcutaneously. Blood was collected every 1-2 wks and PBMC were cryopreserved in liquid nitrogen. All animal studies were conducted using an approved Institutional Animal Care and Use Center protocol.

Challenge with A. marginale

Eleven months after the primary immunization, four immunized and four control calves were challenged intravenously with 1 × 106 erythrocytes infected with viable Florida strain A. marginale. The packed cell volume, percent infected erythrocytes, determined by light microscopy of Giemsa-stained blood films, and general health were monitored daily. Blood was collected weekly, and PBMC purified by Histopaque® (Sigma) density gradient centrifugation were either used immediately for proliferation assays or cryopreserved for additional assays.

Spleen, liver and lymph node lymphocytes

All immunized and two control calves were euthanized between 63 and 89 days post-challenge and samples of spleen, liver, and inguinal lymph nodes (LN) were collected. Lymphocytes were purified from gently disrupted spleen and LN samples by Histopaque gradient centrifugation, repeatedly washed with HBSS, and resuspended in RPMI-1640 medium (Sigma) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 100 mM L-glutamine, 5 × 10−5 M β-mercaptoethanol, 24 mM HEPES buffer, and 0.05 mg/ml gentamycin sulfate (complete medium). A sample of liver was perfused with cold PBS, ground in a meat grinder with RPMI-1640 medium, digested with 0.002% DNase I (Sigma) and 0.05% bovine collagenase IV (Sigma) in RPMI medium for 50 min at 37°C, and lymphocytes were extracted by repeated Histopaque centrifugation and washing in HBSS. Lymphocytes from the tissues were used directly in proliferation assays and extra cells were cryopreserved.

Lymphocyte proliferation and IFN-γ ELISPOT assays

Lymphocyte proliferation assays were performed in triplicate using 2.5 × 105 viable cells/well in complete medium (12, 13), and unless indicated otherwise, freshly obtained PBMC were used. Cryopreserved PBMC were used for the day 144 post-immunization time point for the data shown in Fig. 4. Antigens consisted of 1 and 10 μg/ml A. marginale Florida strain homogenate, uninfected erythrocyte membranes (URBC), MSP1a peptide F2-5, and negative control peptides B. bovis rhoptry associated protein-1 (RAP-1) peptide P2 [(LRFRNGANHGDYHYFVTGLLNNNVVHEEGT; (20)], and A. marginale MSP2 peptide P1 [MSAVSNRKLPLGGVLMALVAAVAPIHSLLA; (21)] designated MSP2 P1. T cell growth factor diluted 1:10 and Clostridium spp. vaccine antigen diluted 1:100 or 1:1000 in complete medium were positive controls. After 6 days, cells were labeled with 0.25 μCi 3[H] thymidine for 8 hr, harvested, and counted in a β—counter. Statistical significance was determined using a one-way ANOVA with a Tukey correction for multiple comparisons, and results were considered significant when P <0.05. For IFN-γ ELISPOT assays (12, 13, 17), cryopreserved PBMC from multiple time points were tested in the same assay to eliminate assay-to-assay variation. Cells were thawed, purified over Histopaque®, and cultured in triplicate at 5 × 105 cells/well with 5 × 105 irradiated PBMC/well from a donor homozygous for DRB3*1101, and 1 or 10 μg/ml peptide F2-5 or negative control peptide RAP-1 P2. A mixture of PHA (Sigma) (1 μg/ml) plus 0.01 ng/ml recombinant human IL-12 (Genetics Institute) was a positive control. Results are presented as the mean number (no.) of spot forming cells (SFC)/106 PBMC after subtracting the background mean no. SFC from cells cultured with RAP-1 P2 peptide. Significant responses to peptide F2-5 were determined using a Student’s one-tailed t-test where P <0.05.

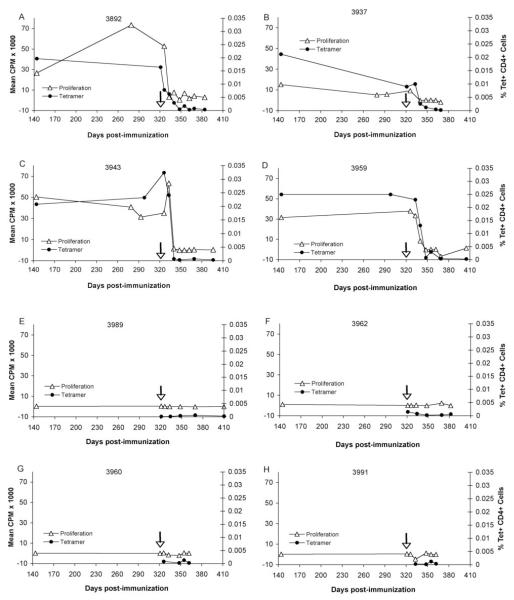

Figure 4.

T lymphocyte proliferation and enumeration of tetramer+ CD4+ cells in PBMC from vaccinates and controls before and after A. marginale infection. PBMC were obtained on day 141 post-immunization and at select time points thereafter and following challenge on day 321 (arrow). Cryopreserved PBMC were stained with the tetramer and analyzed by FACS. A-D, Results are presented for all vaccinates. E-H, Results are presented for all control animals. For proliferation assays, lymphocytes from animals 3960 and 3991 were cryopreserved, whereas lymphocytes remaining animals were fresh. The data represent the percentages of tetramer+ CD4+ cells of the total CD4+ T cells (black circles) or the mean CPM of triplicate cultures with 1 μg/ml peptide F2-5 after subtracting the background mean CPM in response to medium (white triangles).

Construction of DRB3*1101-F2-5B and DQA*1001/DQB*1002-F3-3 tetramers

Construction of the phycoerythrin (PE)-labeled DRB3*1101-F2-5B tetramer was previously described (18). The Anaplasma marginale MSP1a F3-3 peptide (30-mer) was previously identified as a CD4+ T cell epitope restricted by MHC class II DQA*1001/DQB*1002 (16, 19) and the epitope was further defined to a 15-mer peptide, PAGQEKTAEPEHEAA. To construct the DQA*1001/DQB*1002-F3-3 tetramer, eukaryotic expression vectors (pcDNA3.1) expressing the DQA*1001-basic leucine zipper-biotinylation sequence (DQA*1001-blz-bs) and the DQB*1002-acidic leucine zipper-FLAG (DQB*1002-abz-FLAG) were generated using the same PCR method as previously described (18). The templates for the PCR were pCR3.1BoLADQA*1001 and pCR3.1BoLADQB*1002, respectively (19). The DQB*1002-abz-FLAG construct was further modified by linking the T-cell epitope, PAGQEKTAEPEHEAA, between the signal sequence and the N-terminal end of matured DQB*1002 sequence with 16 amino acid linker using the same protocol as previously described (18). The signal sequence was later replaced with the DRB3*1201 leader sequence (18) for better expression. The primers used for the construction of the DQA*1001/DQB*1002F3-3 tetramer are listed in Table I or were previously described (18). Production and purification of soluble DQA*1001/DQB*1002F3-3 dimers and construction of the PE-labeled tetramer were performed as previously described (18), and this tetramer was used as a negative control.

Table I.

Primers used for constructing the DQA*1001/DQB*1002-F3-3 tetramer

| Construct | Name | Primer sequence (5′ to 3′) |

|---|---|---|

| QA*1001-blz-bs | DQA-bLZF | CTATGTCAGAGCTGACAGAGTCGTCAGCAGACCTGGTTCC |

| DQA-bLZR | GGAACCAGGTCTGCTGACGACTCTGTCAGCTCTGACATAG | |

| DQB*1002F3-3-alz-FLAG | DQB-aLZF | CTGAATCTGCCCAGAGCAAGTCGTCAGCAGACCTGGTTCC |

| DQB-aLZR | GGAACCAGGTCTGCTGACGACTTGCTCTGGGCAGATTCAG | |

| DQBRBR | TACACGAAATCCTTTGGGATCTCCCTGGCCCAG | |

| DRBQBF | CTGGGCCAGGGAGATCCCAAAGGATTTCGTGTA | |

| DQBLinkerF | TGGGTCCCCAAAGGATTTCGTGTA | |

| DQBLinkerR | TACACGAAATCCTTTGGGGACCCACCTCCTCCAGAGCCCCGTGG | |

| DQBF3-3R1 | TTTCTCTTGCCCCGCAGGGATCTCCCTGGCCCAGGC | |

| DQBF3-3R2 | TGCTCAGGTTCGGCAGTTTTCTCTTGCCCCGCAGG | |

| DQBF3-3R3 | AGTGAGCCACCACCTCCCGCAGCCTCATGCTCAGGTTCGGCAGT |

Enumeration of F2-5-specific CD4+ T cells by tetramer staining

The previously described PE-labeled DRB3*1101-F2-5B tetramer (18) was used to enumerate F2-5-specific T cells in PBMC and tissue lymphocytes, after selecting tetramer+ cells with anti-PE microbeads (Miltenyi Biotec) (22). The 16-mer F2-5B peptide (ARSVLETLAGHVDALG) T-cell epitope in peptide F2-5, is presented by DRA/DRB3*1101 (16, 18, 19). For each animal, cryopreserved PBMC from multiple time points were tested in the same assay to eliminate assay-to-assay variation. A number of samples were also independently stained by two individuals to verify reproducibility of the staining. PBMC (up to 20 × 106) were purified by Histopaque gradient centrifugation, washed 3 times and resuspended in complete medium, mixed with 20 μg/ml of PE-labeled DRB3*1101-F2-5B tetramer, and incubated in the dark at room temp for 1 h. Cells were then stained with a mixture of FITC-conjugated mouse anti-bovine CD4+ monoclonal antibody (MAb) MCA1365 (Serotec), Alexa Fluor (AF)-647 conjugated mouse anti-human CD14 MAb MCA1568A647 (Serotec), and MAbs obtained from the Washington State University MAb Center specific for bovine CD8 (7C2B), CD21 (GB25A), and the TCR δ chain (GB21A), each conjugated with AF-647 (Invitrogen) and used at a final concentration of 10 μg/ml. 7-amino-actinomycin D (10 μg/ml) (Sigma) was added to label and later exclude any dead cells. Cells were incubated in the dark at room temp for 20 min, washed three times with MACS buffer (1X PBS, Ph 7.2, 0.5% bovine serum albumin, and 2 mM EDTA). Cells (10%) were set aside for FACS analysis, and 90% were resuspended to 160 μl of bead buffer, mixed with 40 μl mouse anti-PE microbeads (Miltenyi Biotec), incubated in the dark for 20 min at 4°C, and passed through a MS column placed in a magnetic field (Miltenyi Biotec) to positively select PE-tetramer stained cells. Cells were analyzed using four-color flow cytometry (18), and frequencies of F2-5-specific CD4+ T cells were derived by dividing the number of tetramer+ CD4+ cells by the total number of CD4+ T cells in the starting population, reported as a percentage of this population of cells. Significant differences in frequencies of tetramer+ CD4+ T cells in the vaccinates at different times and in different tissues were determined using one-tailed, paired t-tests where P<0.05.

Results

Loss of A. marginale peptide F2-5-specific IFN-γ secreting cells following infection

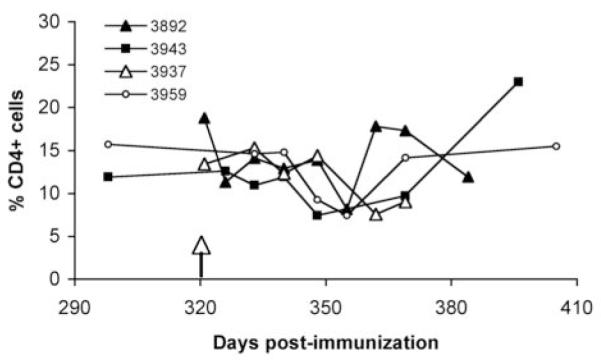

We wanted to determine if the previously observed sudden loss of effector responses following infection is specific to the highly abundant and antigenically variable MSP2 (13), or is reproducible for other A. marginale antigens. We used animals immunized with a DNA construct that had developed strong CD4+ T cell responses directed against a very immunogenic epitope in the conserved MSP1a protein, peptide F2-5 (17). Cattle immunized with the construct encoding the MSP1a F2-5 T cell epitope were infected 11 months later, monitored for anaplasmosis, and F2-5-specific IFN-γ secreting cells in PBMC obtained weekly after challenge were enumerated by ELISPOT. Because calves were immunized with a construct encoding just one T-cell epitope and one B-cell epitope from MSP1a, we did not expect any protection against challenge. As predicted, all four vaccinates and four controls developed acute anaplasmosis, with bacteremias reaching maximal levels of 1.0-3.3% infected erythrocytes between 25-37 days post-infection (data not shown). Infection was associated with anemia determined as a 33-51% decrease in packed cell volumes. All cattle resolved acute bacteremia by seven weeks post-infection. Weekly total leukocyte and differential white blood cell counts indicated no evidence of leukopenia or lymphopenia data (data not shown). Overall, there was no significant change in CD4+ T cell percentages throughout the course of infection, although all calves experienced a mild decline in the percentage of CD4+ T cells during acute infection at the peak of bacteremia (Fig. 1). Additionally, histologically prepared tissue sections of liver and spleen from immunized calf 3959 and control calf 3989 at 11 weeks post-challenge lacked significant lesions (data not shown).

Figure 1.

Enumeration of CD4+ cells in PBMC during A. marginale infection of vaccinates. Cryopreserved PBMC from the four immunized animals (indicated by symbols) were stained with FITC-conjugated anti-CD4 MAb MCA1365 (Serotec) and analyzed by FACS. PBMC were obtained just prior to challenge on day 321 (arrow), and at select time points thereafter until infection was controlled. A one-way ANOVA for multiple comparisons showed no significant difference in the percentages of CD4+ cells in the animals before and after infection (P=0.35).

Previous results from these animals showed that after a single DNA immunization, significant numbers of CD4+ IFN-γ secreting cells were detected in all vaccinates, and specific responses were significantly elevated following a peptide boost (17). At the time of challenge, significant numbers of IFN-γ secreting cells were still detected in PBMC (Table II). In three animals, infection appeared to expand the number of IFN-γ secreting cells two weeks post-infection. However, this response was no longer significant in any animal by four weeks post-infection, concomitant with peak bacteremias. These results are similar to those reported earlier for animals immunized repeatedly with MSP2 (13), except that in all MSP2 vaccinates there was a decreased frequency of IFN-γ secreting cells between two to three weeks post-challenge (13). F2-5-specific IFN-γ secreting cell numbers remained at background levels, similar to those of two control animals that were also followed, until the animals were euthanized five to nine weeks later. Thus, our results show that following A. marginale infection, the loss of antigen-specific T lymphocyte recall responses elicited by repeated immunization is not unique for the immunodominant and variable MSP2 protein, but occurs similarly in animals primed to a defined and conserved CD4+ T cell epitope of MSP1a. Additionally, the route and type of immunization used to establish a specific T lymphocyte response was not a factor in the loss of the recall response, as the results were similar when CD4+ T lymphocyte responses were generated using protein inoculation with multiple protein boosts (13) or a single DNA inoculum with one protein boost (17). However, neither of these experiments can distinguish between a loss of effector function (i.e. IFN-γ secretion) or T cell anergy and a physical loss of antigen-specific T cells. Because we immunized with an MSP1a construct that contained a single T cell epitope, we were able to use this model to ask whether the loss of antigen-specific responses was caused by physical deletion of cells from the peripheral blood by staining F2-5-specific T cells with a bovine MHC class II tetramer.

Table II.

Comparison of IFN-γ secreting cells in PBMC before and after challenge

| No. SFC per 106 PBMC from animals in the following groupa | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Immunized |

Control |

|||||

| Antigen | 3892 | 3937 | 3943 | 3959 | 3962 | 3989 |

| Pre-challengeb | 128 | 377 | 833 | 521 | 20 | −97 |

| Post-challengec | ||||||

| 2 wk | 179 | 163 | 827 | 683 | 91 | 5 |

| 4 wk | 290 | 71 | 17 | −18 | −15 | 2 |

| 6 wk | 84 | −23 | −19 | −55 | 94 | −25 |

| 9-12 wk | 180 | 17 | 104 | −72 | −79 | −260 |

Cryopreserved PBMC from immunized or control animals were stimulated in triplicate wells for 40 hr with 1.0 μg/ml of F2-5 peptide (PBMC) or negative control RAP-1 P2 peptide. Results are presented as the mean number of SFC per 106 PBMC after subtracting the response to negative control peptide. Significantly greater responses to F2-5 peptide are indicated in bold, determined by a Student’s one-tailed paired t-test where P<0.05.

Pre-challenge PBMC were obtained the day of challenge, except for animal 3943, where PBMC were obtained 3 wk before challenge. The response to F2-5 had too many spots to count so the no. SFC was estimated at 600 per 5 × 105 cells/well.

PBMC were obtained from animals euthanized between 9-12 weeks post challenge.

DRB3*1101-F2-5B tetramer staining detects CD4+ T cells in PBMC

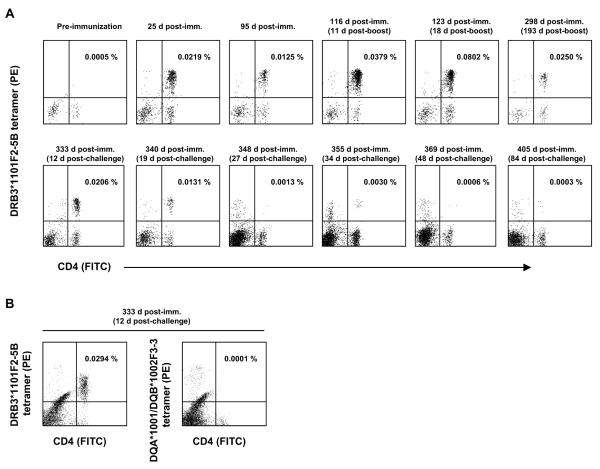

We have previously shown that bovine MHC class II tetramers were able to detect antigen-specific T cells in cell lines or clones expanded from PBMC in vitro, and the specificity of the DRB3*1101-F2-5B tetramer was also demonstrated (18). This tetramer specifically stained T cells from an MSP1-immunized steer that were expanded ex vivo after several rounds of stimulation with native MSP1a and peptide F2-5B, whereas the same tetramer loaded with an irrelevant peptide did not (18). However, the frequency of antigen-specific CD4+ T cells is too low in peripheral blood for direct detection by tetramer staining. We therefore enriched PE-labeled tetramer+ cells in PBMC with anti-PE beads prior to analysis using a method established for staining human PBMC with tetramers (22). To verify that this technique would enable direct detection of F2-5-specific T cells in PBMC, cryopreserved PBMC obtained before and after DNA immunization, and after the protein boost on day 105 were stained with the tetramer, enriched, and analyzed by flow cytometry. Cells obtained from multiple time points from an individual animal were stained in one experiment to eliminate any assay-to-assay variation. Fig. 2A presents results from animal 3959 from before immunization to day 298 post-immunization. The numbers in the upper right quadrants are the calculated percentages of tetramer+ CD4+ T cells of the total number of CD4+ T cells. In this animal, tetramer+ CD4+ T cells increased from a baseline of 0.0005% to 0.022 % by day 25 post-immunization, fell to about 50% of this level by day 95, and increased rapidly in response to the peptide boost on day 105 so that by 18 days post-boost, there was a frequency of 0.08% tetramer+ CD4+ T cells. This then declined to 0.025% on day 193 post-boost. To confirm the reproducibility of tetramer staining using cryopreserved T cells, and to document the specificity of staining, PBMC obtained at day 133 post immunization were thawed and stained again with the DRB3*1101-F2-5B tetramer or with an irrelevant tetramer composed of DQA/DQB molecules and peptide MSP1a-F3-3 (16, 19, 23) not found in the immunogen (Fig. 2B). In this experiment, 0.0294% of the CD4+ T cells were stained with the DRB3*1101-F2-5B tetramer, whereas a background level of staining was observed with the nonspecific DQ-F3-3 tetramer. In contrast, the DQ tetramer stained 87.9% of cells in a T cell line from MSP1a-immunized animal 4919 (23) cultured with MSP1a for six weeks (data not shown). Thus, the specificity of the tetramer is documented by the lack of specific staining of PBMC obtained prior to immunization, and by the lack of non-specific staining by a tetramer containing a non-stimulatory peptide.

Figure 2.

Enumeration of antigen-specific CD4+ T cells in peripheral blood of animal 3959 before and after immunization and A. marginale infection. A, Cryopreserved PBMC were stained with the DRB3*1101-F2-5B tetramer at the indicated time points and analyzed by FACS. Dot plots indicate the percentage of tetramer+ CD4+ cells after anti-PE magnetic bead selection. The upper panel shows cells obtained before and after immunization and after the peptide boost on day 105. The bottom panel shows cells obtained 12-84 days following A. marginale challenge. B, Cryporeserved PBMC obtained 12 days post-challenge were thawed and stained with either the DRB3*1101F2-5B tetramer or an unrelated DQA*1101/DQB*1102F3-3 tetramer after anti-PE magnetic bead selection. The numbers in the upper right quadrants are the calculated percentage of tetramer+ CD4+ T cells of the total CD4+ T cells in the samples.

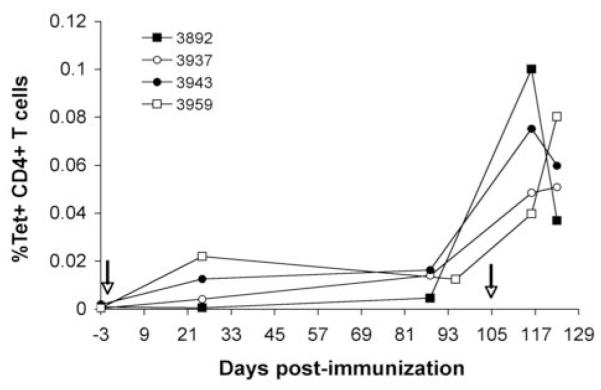

The other three vaccinated animals had a similar pattern of expansion of peptide F2-5-specific T cells following immunization and boost, with baseline frequencies of tetramer+ CD4+ T cells of 0.0003% (animal 3937), 0.00196% (animal 3943) and 0.0009% (animal 3892) and reaching maximum frequencies of 0.051% (3937), 0.075% (3943) and 0.100% (3892) of the total CD4+ T cell population following the peptide boost (Fig. 3). The increase in tetramer+ CD4+ cells in PBMC obtained following the peptide boost is consistent with significantly elevated CD4+ T cell proliferation and numbers of IFN-γ secreting cells from these animals after the boost (17). Therefore, we proceeded to enumerate antigen-specific T cells after infection with A. marginale.

Figure 3.

Enumeration of tetramer+ CD4+ cells in PBMC from all vaccinates before and after immunization and peptide boost. Cryopreserved PBMC were stained with the tetramer and analyzed by FACS. PBMC were obtained 3 days before immunization (arrow) and at several time points thereafter and following the peptide boost on day 105 (arrow). Individual animals are indicated. The data represent the percentage of tetramer+ CD4+ cells of the total CD4+ T cells.

Loss of antigen-specific responses corresponds with loss of tetramer+ CD4+ T cells in PBMC

In addition to measuring IFN-γ secreting cells, proliferation was also used to measure antigen-specific T lymphocyte responses before and after challenge. Because the majority of proliferation assays were performed with fresh cells, whereas IFN-γ ELISPOT and tetramer staining experiments were performed with cryopreserved cells, there was a possibility that cryopreserved cells do not adequately represent the response of fresh cells. However, a direct comparison of lymphocyte proliferation to peptide F2-5 using fresh PBMC and cryopreserved PBMC obtained at the same time and tested 17 months later demonstrates that there was no loss of antigen-specific proliferation when the same number of PBMC were tested in each assay (Table III).

Table III.

Comparison of antigen-specific proliferation using fresh and cryopreserved pre-challenge PBMC

| Animala | Proliferation (mean CPM +/− 1 SD) against the following antigens:b |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MSP1a F2-5 | MSP2 P1 | MSP1a F2-5 | MSP2 P1 | |

| Immunized | Fresh PBMC | Cryopreserved PBMC | ||

| 3982 | 39,752 +/− 3,352 | Negc | 48,564 +/− 5,784 | 715 +/− 790 |

| 3937 | 13,802 +/− 2,021 | 2,522 +/− 1,472 | 27,744 +/− 6,736 | 442 +/− 395 |

| 3943 | 43,608 +/− 8,025 | Neg | 57,972 +/− 6,898 | Neg |

| 3959 | 39,360 +/− 1,828 | 761 +/− 223 | 44,298 +/− 6,426 | 733+/− 755 |

| Controls | Fresh PBMC | Cryopreserved PBMC | ||

| 3962 | Neg | Neg | 114 +/− 61 | 10 +/− 13 |

| 3989 | Neg | Neg | 194 +/− 156 | 367 +/− 766 |

| 3960 | Neg | Neg | 83 +/− 49 | 778 +/− 1,084 |

| 3991 | 744 +/− 1,555 | 1,223 +/− 2,231 | 198 +/− 259 | 16 +/− 82 |

PBMC were obtained on day 144 post immunization from vaccinates or controls and were tested immediately in a proliferation assay or cryopreserved in liquid nitrogen until they were tested approximately 17 months later.

Peptides were used at a final concentration of 10 μg/ml. Results are presented as the mean CPM +/− 1 SD of triplicate samples after subtracting the background response to medium. Responses significantly greater than the negative control MSP2 P1 peptide are in bold.

Neg indicates the responses was < 0 after subtracting the medium control.

Antigen-specific proliferation was compared with the frequency of antigen-specific cells, detected by tetramer staining, in peripheral blood of all four vaccinates from day 144 post-immunization, until challenge on day 321 and thereafter until acute bacteremias had resolved and the animals were euthanized (Fig. 4A-D). As expected, immunized calves had significant F2-5-specific T lymphocyte proliferative recall responses prior to challenge on day 321 and at 5 days post-challenge (day 326). On days 12 and 19 post-challenge, only PBMC from animals 3943 and 3959 still had significant proliferation to peptide F2-5, but by day 26 post-challenge (at or just preceding peak levels of bacteremia, day 340 post immunization) and thereafter F2-5-specific T lymphocyte proliferative responses had sharply decreased in all immunized animals to background levels. Control animals had no response to peptide F2-5 at any time point during infection (Fig. 4E-H). These results show that both IFN-γ secreting cells and proliferating cells specific for peptide F2-5 dramatically decline to background levels following challenge, as observed previously for MSP2-vaccinated and challenged calves (13).

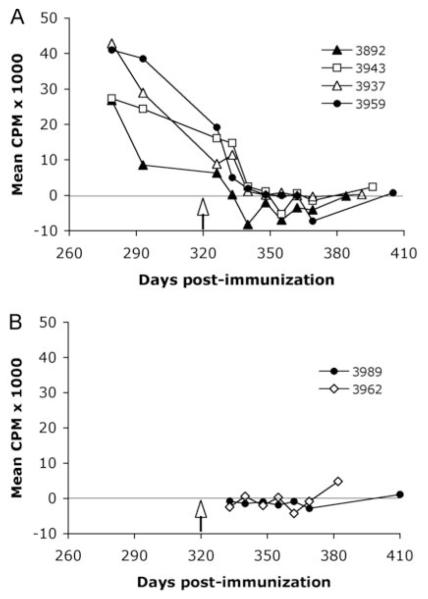

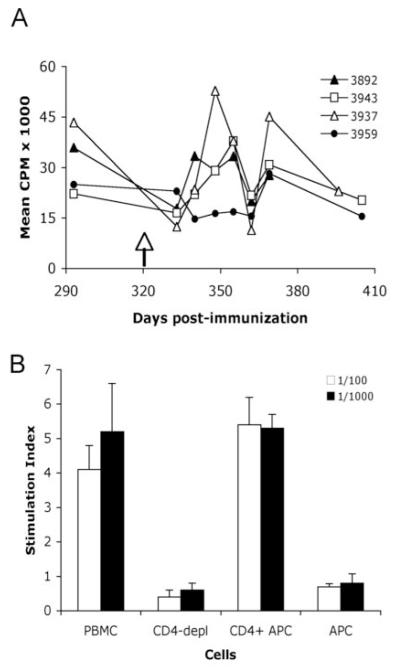

Proliferative responses to A. marginale homogenate were also significant in all immunized animals at both time points before challenge and at 5 days post-challenge (Fig. 5A). On days 12 and 19 post-challenge, only PBMC from animals 3937 and 3943 had significant proliferation to A. marginale, and thereafter all animals had insignificant responses when compared to either URBC or medium. Neither control animal tested had significant proliferation to A. marginale at any time point (Fig. 5B). In contrast, proliferative responses to a Clostridium vaccine antigen remained significantly positive throughout acute and resolving bacteremia when compared to either medium or URBC (Fig. 6A). The response to Clostridium vaccine is CD4+ T-cell mediated (Fig. 6B), indicating that A. marginale infection does not simply induce a generalized suppression of CD4+ T-cell responses.

Figure 5.

Proliferation of PBMC against A. marginale homogenate before and after A. marginale infection. A, PBMC from the four vaccinates or B, two controls (indicated by symbols) were obtained before and at various time points after challenge on day 321 (arrow) and fresh cells were cultured in triplicate for 6 days with A. marginale homogenate at 10 μg/ml. Data are presented as the mean CPM after subtracting background responses to 10 μg/ml URBC antigen. Responses were significantly greater than those to either medium or URBC in all vaccinates on both days before and on day 5 post-challenge. There was no significant response to A. marginale in either control animal at any time point.

Figure 6.

Proliferation of PBMC from immunized animals to Clostridium vaccine antigen before and after A. marginale infection. A, PBMC from the four immunized animals (indicated by symbols) were obtained before and at various time points after challenge on day 321 (arrow) and fresh cells were cultured in triplicate for 6 days with Clostridium antigen diluted 1:1000. Data are presented as the mean CPM after subtracting background responses to medium. Responses were significantly greater than those to medium or URBC for all animals at all time points. B, CD4+ T cells were positively selected from cryopreserved bovine PBMC with anti-CD4 MAb ILA-11 bound to goat anti-mouse IgG beads (Miltenyi Biotec) passed over a magnetic field. Cells were stained for CD4+ cells by FACS using MAb CACT138A. Undepleted PBMC (28.2% CD4+ T cells), enriched CD4+ T cells (79.1% CD4+ T cells), and PBMC depleted of CD4+ T cells (3.4% CD4+ T cells) were tested in a proliferation assay using Clostridium antigen diluted 1:100 and 1:1,000, with 2.5 × 105 PBMC or CD4-depleted PBMC/well, 2.5 × 105 CD4+ enriched cells, plus 2 × 105 irradiated PBMC as APC/well, or APC alone. Results are presented as the stimulation index, calculated as the mean CPM of cells cultured with antigen/mean CPM of cells cultured with complete medium. Statistically significant responses to antigen are indicated by asterisks, where P<0.05.

Importantly, the sharp loss of antigen-specific responses by all vaccinates following infection was mirrored by a rapid decline in tetramer+ CD4+ T cells in PBMC (Fig. 2 lower panel, Fig. 4, and Table II). For example, on day 369 (48 days post-challenge), the frequencies of antigen-specific cells ranged from 0.0002-0.0008%, which were not significantly different from pre-immunization levels (P=0.177), but were ~100-fold less than those near the time of challenge, which was significant (P=0.014). Reproducibility of the tetramer staining with two or more aliquots of cryopreserved PBMC is documented in Table IV. The replicate samples were stained, in most cases, by different individuals and show similar results, and the mean values were used in Fig. 4 where more than one tetramer staining assay was performed. PBMC from the control animals showed background levels of staining with the tetramer, which further supports the specificity of this tetramer for staining antigen-specific T cells (Fig. 4E-H). The rapid drop in antigen-specific T cells from peripheral blood of vaccinates cannot be attributed to natural homeostasis of memory CD4+ T cells, which in mice have a reported half-life of ~400 days in the late contractual phase beyond 180 days post-infection (24). These results are most consistent with rapid physical deletion of antigen-specific T cells following high levels of bacteremia during acute infection, but there was a possibility that antigen-specific cells sequestered out of the peripheral blood, presumably to the spleen where blood-borne pathogens are typically removed (25). To address this question, antigen-specific lymphocytes from the spleen, a peripheral LN, and the liver were examined.

Table IV.

Reproducibility of tetramer staining

| Cell sourcea | Frequency (%) of tetramer+ CD4+ cells from animalb: | |

|---|---|---|

| 3892 | 3959 | |

| PBMC | ||

| Day 326 | 0.0078 +/− 0.0014 | NDc |

| Day 333 | 0.0063 +/− 0.0018 | 0.023+/− 0.0034 |

| Day 340 | 0.0029 +/− 0.0025 | ND |

| Day 348 | 0.0005 +/− 0.0005 | 0.0008+/− 0.0006 |

| Day 355 | ND | 0.0028+/− 0.0002 |

| Day 369 | 0.0008 +/− 0.0007 | 0.0004+/− 0.0003 |

| Day 384 | 0.0004 +/− 0.0003 | ND |

| Liver | 0.0019 +/− 0.008 | ND |

| Spleen | 0.0004 +/− 0.00005 | ND |

Cells were cryopreserved from PBMC or tissues at the indicated days post-immunization.

Results are presented as the mean frequency +/− 1SD of two to four replicate aliquots.

Not determined for more than one sample at these time points.

Antigen-specific T-cells in spleen, inguinal LN, and liver

To determine if effector CD4+ T cells sequestered to the spleen or other tissues, all vaccinates and two control animals were euthanized from 9-13 weeks post-challenge, and antigen-specific responses of spleen, liver, and inguinal LN lymphocytes were determined. Weak but statistically significant F2-5-specific lymphocyte proliferative responses were detected in lymphocytes derived from fresh spleen samples of two vaccinates (3943 and 3959) and from fresh liver samples of three vaccinates (3892, 3943, and 3959) (Table V). However, we did not detect antigen-specific proliferation with cryopreserved spleen or liver cells from animals 3943 and 3892 (data not shown), whereas cryopreserved cells from animal 3959 continued to have significant responses (Table V). Responses were not detected in the LN of any vaccinate or from any tissue derived from the two controls. To determine whether a low frequency of responding T lymphocytes in liver and spleen could be expanded, we repeatedly attempted to culture cryopreserved spleen and liver lymphocytes from animals 3892, 3943, and 3959 with antigen, or with antigen plus human recombinant IL-2, but were unsuccessful. In contrast, short-term cultures of peptide F2-5-specific lymphocytes were easily derived from responsive PBMC from the same donors (data not shown) as we normally do to establish CD4 T cell lines (11, 16).

Table V.

F2-5 specific T lymphocyte proliferative responses from PBMC, spleen, LN and liver at euthanasia

| Proliferation (Stimulation Index) from the following groupa | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Immunized |

Control |

|||||||

| Cellsb | Antigen | 3892 | 3937 | 3943 | 3959 | 3959c | 3962 | 3989 |

| PBMC | F2-5 (1) | 1.3 | 1.8 | 1.0 | 3.1 | 2.0 | 0.7 | 0.7 |

| F2-5 (10) | 1.0 | 0.3 | 0.9 | 1.9 | 2.7 | 1.2 | 1.0 | |

| Spleen | F2-5 (1) | 1.5 | 1.9 | 12.2 | 1.0 | 4.3 | 0.9 | 1.0 |

| F2-5 (10) | 2.0 | 2.0 | 13.2 | 2.1 | 4.7 | 1.3 | 1.8 | |

| LN | F2-5 (1) | 0.8 | 1.6 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.9 | 2.4 | 0.9 |

| F2-5 (10) | 0.7 | 1.8 | 1.8 | 0.2 | 2.4 | 1.2 | 1.4 | |

| Liver | F2-5 (1) | 11.3 | 0.8 | 2.8 | 0.7 | 10.2 | 0.8 | 1.0 |

| F2-5 (10) | 8.3 | 1.3 | 3.4 | 5.0 | 7.0 | 1.0 | 0.9 | |

Peptides F2-5 and MSP2 P1 were tested at 1 and 10 μg per ml. Results are shown as stimulation index calculated as mean CPM of triplicate cultures of peptide F2-5 peptide/mean CPM of triplicate cultures with medium. Responses significantly greater than those to medium and negative control peptide MSP2 P1 (P<0.05) are bolded.

Lymphocytes were obtained at euthanasia and used immediately.

Lymphocytes from animal 3959 were also used after cryopreservation.

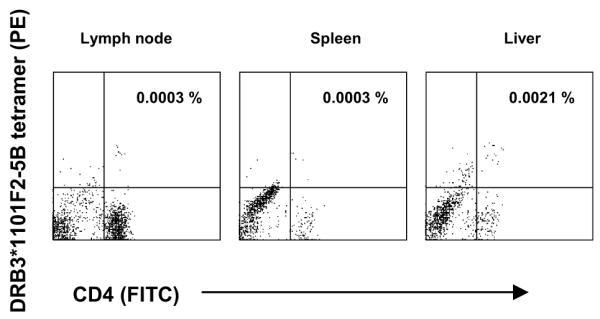

These data suggest that the weak and inconsistent responses detected in spleen and liver, which could not be expanded in culture, may either represent cells undergoing the early stages of apoptosis, or that specific cells in these tissues are present but anergic. Activated antigen-specific human and mouse CD8+ T lymphocytes commonly traffic to the liver where they undergo apoptosis, resulting in the removal of these cells from the peripheral blood, and it has been proposed that activated antigen-specific CD4+ T lymphocytes undergo similar trafficking and apoptosis (26). To try to distinguish these possibilities, cryopreserved lymphocytes from spleen, LN, and liver were examined by flow cytometry after staining with the DRB3*1101-F2-5B tetramer and enriching the stained cells with anti-PE beads. Representative dot plots showing the frequency of F2-5-specific CD4+ T lymphocytes in mononuclear cells from tissues of vaccinate 3959 are shown in Fig. 7, and the results from all animals are summarized in Table VI. For comparison, we have included the baseline frequencies of tetramer+ CD4+ cells in PBMC obtained prior to immunization, and either on the day of challenge or 5-12 days later (time points where enough cells were available for analysis). Compared with PBMC at the time of euthanasia, all immunized animals had approximately 10-fold higher frequencies of F2-5B-specific T cells in liver, which was significant (P=0.008), but significant differences were not found in spleen or lymph node.

Figure 7.

Enumeration of antigen-specific CD4+ T cells in the inguinal LN, spleen, and liver from animal 3959. Cryopreserved lymphocytes were stained with the DRB3*1101-F2-5B tetramer and analyzed by FACS. The dot plots indicate the tetramer+ CD4+ cells after selection on anti-PE magnetic beads. The numbers in the upper right quadrants are the calculated percentages of tetramer+ CD4+ T cells of total CD4+ T cells.

Table VI.

Frequencies of tetramer+ CD4+ cells in PBMC, spleen, LN, and liver at euthanasia

| Frequency (%) of tetramer+ CD4+ cells from the following groupa | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Immunized |

Control |

|||||

| Cell sourceb | 3892 | 3937 | 3943 | 3959 | 3962 | 3989 |

| PBMC (pre-immunization) | 0.0009 | 0.0003 | 0.0020 | 0.0005 | ||

| PBMC (challenge) | 0.0361 | 0.0090 | 0.0324 | 0.0206 | 0.0015 | 0.0001 |

| PBMC (death) | 0.0003 | 0.0002 | 0.0003 | 0.0003 | 0.0006 | 0.0002 |

| Spleen (death) | 0.0004 | 0.0018 | 0.0048 | 0.0003 | 0.0006 | NDc |

| LN (death) | 0.0013 | 0.0001 | 0.0026 | 0.0003 | 0.0018 | 0.0007 |

| Liver (death) | 0.0019 | 0.0027 | 0.0032 | 0.0021 | NDc | 0.0009 |

Cryopreserved lymphocytes were thawed, and viable cells stained with the *1101-F2-5B tetramer. The percentage of tetramer+ CD4+ cells of total CD4+ T cells was calculated. Numbers in bold represent significantly higher mean frequencies of tetramer+ CD4+ T cells in compared with those in PBMC pre-immunization using a one-tailed paired t-test (P= 0.008 for liver and P= 0.014 for PBMC at the time of challenge).

Cryopreserved PBMC were obtained before immunization, on the day of challenge (day 321 post immunization; animals 3892, 3937, 3989, 3962), 5 days post-challenge (animal 3943), 12 days post-challenge (animal 3959), and at the time of death (day 63, animals 3892 and 3962; day 69, animal 3937; day 75, animal 3943; day 84, animal 3959, and day 89 post-challenge, animal 3989).

Not determined because of insufficient cell numbers.

Discussion

The current understanding of how pathogens evade and/or modulate the immune system of an immunocompetent host to achieve persistent and even lifelong infection is still in its infancy. However, unraveling these mechanisms is vital to the eventual control of many persistent infections in people and animals. In this study we demonstrate that following infection with A. marginale, a rickettsial pathogen that replicates to high numbers in erythrocytes during acute and persistent infection, antigen-specific CD4+ T cells elicited by prior immunization rapidly disappear from peripheral blood near the peak of rickettsemia. This discovery likely explains the previously reported sudden loss of MSP2-specific CD4+ T cell-mediated IFN-γ and proliferative responses after infection (13). Additionally, the loss of antigen-specific CD4+ T cell responses upon infection occurs with T cells specific for a conserved (MSP1a) as well as antigenically variable (MSP2) membrane protein, in animals immunized by subcutaneous inoculation of protein antigen in adjuvant or by intradermal DNA immunization followed by a peptide boost.

MSP2 is an immunodominant and highly abundant protein that is one of the primary targets of T cell and antibody recognition in animals immunized with outer membranes (27, 28) and is the major antigen recognized by antibody during infection (29). MSP2-immunized animals mounted strong antigen specific responses to multiple epitopes on the protein, in both conserved and hypervariable regions (11-13, 21). Both proliferation and IFN-γ secreting cells, measured by ELISPOT assay, were rapidly lost after infection (13). Thus in this experiment, the loss of T cells is unlikely explained by lack of sufficient MSP2 presentation to enable survival of the primed T cells. Similarly, the loss of antigen-specific CD4+ T cells documented in the present study does not likely result from a failure of MSP1a F2-5-specific T cells to receive survival signals due to insufficient antigen presentation during infection. First, PBMC from calves immunized with the protective outer membrane fraction proliferate to native MSP1, a heterodimer of MSP1a and MSP1b (27), and MSP1b is poorly immunogenic for T cells (30). Second, CD4+ T cell clones derived from two calves immunized with native MSP1 and specific for MSP1a F2-5 peptide presented by DRA/DRB3*1101 (19) proliferated strongly to both peptide and A. marginale lysate (16). Finally, we have shown that in the present study, MSP1a F2-5-specific T cells obtained before challenge from immunized animals proliferated strongly to both the immunizing peptide and to A. marginale homogenate. These observations demonstrate that A. marginale contains sufficient MSP1a to elicit a recall response in vitro, which should also be sufficient for presentation to T cells by APC in vivo following infection.

Exosomes are small membrane vesicles released from APC that contain MHC molecules and pathogen epitopes, and have been shown to directly activate antigen-specific T cells in vitro in a variety of models (31-35). It is therefore highly unlikely that exosomes containing A. marginale MSP1a F2-5 released in vivo during peak bacteremia from APC are binding to specific T cells and blocking tetramer binding. If such exosomes were present, the T cells should be activated to proliferate and secrete IFN-γ, but instead we observed a rapid loss of these effector functions.

Because A. marginale is a blood borne intraerythrocytic pathogen and is presumably removed from the circulation by phagocytosis in the spleen, the possibility that circulating antigen-specific T cells would traffic to the spleen was evaluated. However, only weak and unsustainable antigen-specific T lymphocyte proliferation was detected in the spleens of two of the four immunized calves at the time of necropsy, which was consistent with an insignificant frequency of tetramer staining cells. Additionally, neither antigen-specific T cell responses nor tetramer+ CD4+ T cells were detected in the inguinal lymph node. Thus, the present study shows that infection-induced loss of A. marginale-specific memory T cell responses from peripheral blood is not due to induction of anergy in circulating T cells or sequestration to the spleen or LN, because the antigen-specific T cells disappeared from blood and could not be accounted for in the spleen or LN where effector memory (spleen) or central memory (LN) T cells would be expected to reside.

It is interesting that ~10-fold higher frequencies of CD4+ tetramer+ T cells were detected in liver samples when compared with PBMC, spleen, or LN obtained at the same time. Lymphocytes obtained from fresh liver samples from three vaccinates proliferated to antigen in vitro, and cryopreserved liver lymphocytes from animal 3959 proliferated as well, showing the cells were not dead (Table V). Nevertheless, the antigen specific cells could not be expanded from viable cryopreserved PBMC of animals 3892, 3943, or 3959 by antigen stimulation in vitro, whereas antigen-specific cells could readily be expanded from cryopreserved PBMC obtained at time points when cells did respond. Together, our findings are most consistent with activation induced cell death of antigen-specific CD4+ T cells upon exposure to continuous high antigenic load during infection and pre-apoptotic cells that have migrated to this organ to be removed (26). Attempts to stain tetramer+ CD4+ T cells from various tissues and at different time points for markers of apoptosis (annexin V) were unsuccessful due to the high background staining on the cells, even with cells which had strong proliferative responses pre-challenge (data not shown). Staining with annexin V does not necessarily indicate cell death; rather annexin V stains cells at the early stage of apoptosis when membrane perturbations occur. The high background staining with annexin V likely reflects the procedures used to freeze and thaw the cells and stain them with the tetramer, as it is well known that any procedure that affects the integrity of the plasma membrane will result in cells positive for annexin V. Enrichment of MHC class II tetramer-positive cells using the microbead selection method has proved to be a very useful tool to enable detection of low frequency CD4+ T cells in peripheral blood (22). However, the enrichment process may make detection of early stage apoptosis technically difficult.

Studies by others have also followed the fate of antigen-specific T cells in response to either antigen or pathogen challenge. Using a T-cell receptor transgenic mouse model, Hayashi et al. (36) observed that adoptively transferred, or in vivo-primed, antigen-specific T cells rapidly became activated, expressed IFN-γ, and divided following an intravenous antigen challenge. However, within 48 hours, the frequency of specific cells in blood, spleen, LN, and liver rapidly decreased to barely detectable levels, and residual cells remained anergic. The mechanism of T cell depletion in this study was not determined. In a different model, malaria-specific, protective CD4+ T cells were expanded ex vivo from immunized mice and adoptively transferred to naïve mice (37). Following challenge with Plasmodium, the antigen-specific cells were rapidly deleted from blood and tissues, which was dependent on IFN-γ, but not on TNF or Fas pathways. However, in both of these rodent models, abnormally high numbers of antigen-specific T cells were present, which could result in competition for antigen and affect normal cell signaling. In a third example, CD4+ T cells from mice infected with Brugia pahangi microfilariae displayed defective antigen-specific T cell proliferative responses and underwent apoptosis when stimulated with antigen ex vivo (38). T cell apoptosis was shown to be IFN-γ dependent using IFN-γ knockout mice, and in vitro studies further demonstrated apoptosis was dependent on nitric oxide (NO) produced by macrophages. However, antigen-specific T cells in the B. pahangi-infected mice did produce IFN-γ, indicating persistence of functional antigen-specific T cells, unlike the T cells isolated during acute and persistent A. marginale infection in the present study. In another example of systemic Bacille Calmette-Guérin (BCG) infection in mice, antigen-specific CD4+ T cells rapidly expanded after infection, and then underwent homeostatic contraction to normal levels (39). The contraction phase was shown to be due to IFN-γ-dependent T cell apoptosis, and was also dependent on NO production by macrophages when examined in vitro. However, this study also differs from ours in that not all effector cells were deleted, and considerable numbers remained in the spleens of wild-type mice following contraction of the effector cells (39). More recently, the same group reported that in this model, IFN-γ acts directly on CD4+ T cells to upregulate mRNA and protein expression from genes encoding intrinsic apoptosis machinery involved in promoting damage to the cell mitochondria (40). It was further shown that IFN-γ also induced expression of cell-extrinsic pro-apoptotic signals TRAIL and TNF-α from CD4+ T cells as well as NO and TNF-α from macrophages (40). These studies demonstrate a key role of IFN-γ produced by antigen-specific CD4+ T cells in response to antigen or infection in directly or indirectly promoting T cell apoptosis, to restore a normal homeostatic response.

Our studies have not yet defined a mechanism of antigen-specific T cell deletion following A. marginale infection, so we cannot rule out the potential importance of IFN-γ secreted by the T cells themselves in promoting apoptosis. However, our studies differ from the mouse studies, in that tetramers were used to track the specific T cells in vivo, and our results show that the specific T cells in peripheral blood are at background pre-immunization levels by 9-12 weeks post-challenge, which is coincident with insignificant proliferation and numbers of IFN-γ secreting cells. Thus, we were unable to detect IFN-γ secreting cells using ELISPOT assays at the same time points when proliferation was undetectable. Our studies also differ from the mouse pathogen models described above because even one year after infection, immunization-induced T cell responses could not be elicited ex vivo (13), indicating that functional memory cells were absent. Furthermore, unlike BCG (39-41), malarial parasites (42), and Babesia bovis, an intraerythrocytic cattle pathogen that does induce a strong febrile and inflammatory response in vivo and inflammatory cytokines in vitro (43-45), there is no evidence that intraerythrocytic A. marginale similarly activates a potent inflammatory response. For example, during acute infection, clinical signs are predominantly related to anemia. Splenomegaly does occur, but cattle do not reproducibly demonstrate sustained elevated body temperatures (13). Furthermore, A. marginale lacks LPS and peptidoglycan (46), two well-known pathogen-associated molecular patterns present in many other gram-negative bacteria that activate macrophages through toll like receptors. Finally, in the two animals examined, no evidence of inflammation was observed in spleen or liver biopsies obtained at necropsy. Our results, therefore, extend the mouse studies that describe apoptosis of CD4+ T cells during infection with several different pathogens known to activate an inflammatory response. We document in a large outbred animal, the rapid loss of a physiologically relevant number of antigen-specific T cells following infection with a naturally occurring pathogen that induces minimal inflammation, and persists indefinitely.

The rapid deletion of immunization-induced A. marginale-specific CD4+ T cells in response to infection may, importantly, indicate another mechanism by which A. marginale modulates the immune response. It is well known that antigenic variation of MSP2 results in immune evasion (10, 11). As new antigenic variants of MSP2 and MSP3 continually arise during persistent infection when bacteria can reach 107 per ml of blood (7-9), ascending bacteremia may cause rapid antigen-induced deletion of CD4+ T cells specific for new variants. Our data showing a lack of CD4+ T cell responses to A. marginale and immunodominant MSP2 following infection of control animals that were not previously immunized with any A. marginale protein (13) and a similar lack of response to A. marginale in our vaccinated and control animals following infection in the present study support this hypothesis.

Acknowledgments

We thank Bev Hunter, Shelley Whidbee, and Stephanie Leach for technical help.

Glossary

3 Abbreviations used in this paper

- MSP

major surface protein

- LN

lymph node

- MAb

monoclonal antibody

- BCG

Bacille Calmette-Guérin.

Footnotes

Disclosures The authors have no financial conflict of interest.

National Institutes of Health Grants R01-AI053692 and R01-AI44005 supported this work.

References

- 1.Sacks D, Sher A. Evasion of innate immunity by parasitic protozoa. Nat. Immunol. 2002;3:1041–1047. doi: 10.1038/ni1102-1041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hornef MW, Wick MJ, Rhen M, Normark S. Bacterial strategies for overcoming host innate and adaptive immune responses. Nat. Immunol. 2002;3:1033–1040. doi: 10.1038/ni1102-1033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Finlay BB, McFadden G. Anti-immunology: evasion of the host immune system by bacterial and viral pathogens. Cell. 2006;124:767–782. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.01.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Belkaid Y. Regulatory T cells and infection: a dangerous necessity. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2007;7:875–888. doi: 10.1038/nri2189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Klenerman P, Hill A. T cells and viral persistence: lessons from diverse infections. Nat. Immunol. 2005;6:873–879. doi: 10.1038/ni1241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Palmer GH, Rurangirwa FR, Kocan KM, Brown WC. Molecular basis for vaccine development against the ehrlichial pathogen Anaplasma marginale. Parasitol. Today. 1999;15:281–286. doi: 10.1016/s0169-4758(99)01469-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Futse JE, Brayton KA, Dark MJ, Knowles DP, Palmer GH. Superinfection as a driver of genomic diversification in antigenically variant pathogens. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:2123–2127. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0710333105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Palmer GH, Brayton KA. Gene conversion is a convergent strategy for pathogen antigenic variation. Trends Parasitol. 2007;23:408–413. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2007.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.French DM, McElwain TF, McGuire TC, Palmer GH. Expression of Anaplasma marginale major surface protein 2 variants during persistent cyclic rickettsemia. Infect. Immun. 1998;66:1200–1207. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.3.1200-1207.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.French DM, Brown WC, Palmer GH. Emergence of Anaplasma marginale antigenic variants during persistent rickettsemia. Infect. Immun. 1999;67:5834–5840. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.11.5834-5840.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brown WC, Brayton KA, Styer CM, Palmer GH. The hypervariable region of Anaplasma marginale major surface protein 2 (MSP2) contains multiple immunodominant CD4+ T lymphocyte epitopes that elicit variant-specific proliferative and IFN-γ responses in MSP2 vaccinates. J. Immunol. 2003;170:3790–3798. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.7.3790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Abbott JR, Palmer GH, Howard CJ, Hope JC, Brown WC. Anaplasma marginale major surface protein 2 CD4+-T-cell epitopes are evenly distributed in conserved and hypervariable regions (HVR), whereas linear B-cell epitopes are predominantly located in the HVR. Infect. Immun. 2004;72:7360–7366. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.12.7360-7366.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Abbott JR, Palmer GH, Kegerreis KA, Hetrick PF, Howard CJ, Hope JC, Brown WC. Rapid and long-term disappearance of CD4+ T lymphocyte responses specific for Anaplasma marginale major surface protein-2 (MSP2) in MSP2 vaccinates following challenge with live A. marginale. J. Immunol. 2005;174:6702–6715. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.11.6702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bielekova B, Martin. R. Antigen-specific immunomodulation via altered peptide ligands. J. Mol. Med. 2001;79:552–565. doi: 10.1007/s001090100259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Plebanski M, Lee EA, Hill AV. Immune evasion in malaria: altered peptide ligands of the circumsporozoite protein. Parasitology. 1997;115(Suppl):S55–S66. doi: 10.1017/s0031182097002035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brown WC, McGuire TC, Mwangi W, Kegerreis K/A, Macmillan H, Lewin HA, Palmer GH. Major histocompatibility complex class II DR-restricted memory CD4+ T lymphocytes recognize conserved immunodominant epitopes of Anaplasma marginale major surface protein 1a. Infect. Immun. 2002;70:5521–5532. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.10.5521-5532.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mwangi W, Brown WC, Splitter GA, Davies CJ, Howard CJ, Hope JC, Aida Y, Zhuang Y, Hunter BJ, Palmer GH. DNA vaccine construct incorporating intercellular trafficking and intracellular targeting motifs effectively primes and induces memory B- and T-cell responses in outbred animals. Clin. Vaccine Immunol. 2007;14:304–311. doi: 10.1128/CVI.00363-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Norimine J, Han S, Brown WC. Quantitation of Anaplasma marginale major surface protein (MSP)1a and MSP2 epitope-specific CD4+ T lymphocytes using bovine DRB3*1101 and DRB3*1201 tetramers. Immunogenetics. 2006;58:726–739. doi: 10.1007/s00251-006-0140-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Norimine J, Brown WC. Intrahaplotype and interhaplotype pairing of bovine leukocyte antigen DQA and DQB molecules generate functional DQ molecules important for priming CD4+ T-lymphocyte responses. Immunogenetics. 2005;57:750–762. doi: 10.1007/s00251-005-0045-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Norimine J, Mosqueda J, Suarez C, Palmer GH, McElwain TF, Mbassa G, Brown WC. Stimulation of T-helper cell gamma interferon and immunoglobulin G responses specific for Babesia bovis rhoptry-associated protein 1 (RAP-1) or a RAP-1 protein lacking the carboxy-terminal repeat region is insufficient to provide protective immunity against virulent B. bovis challenge. Infect. Immun. 2003;71:5021–5032. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.9.5021-5032.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brown WC, McGuire TC, Zhu D, Lewin HA, Sosnow J, Palmer GH. Highly conserved regions of the immunodominant major surface protein 2 of the genogroup II ehrlichial pathogen Anaplasma marginale are rich in naturally derived CD4+ T lymphocyte epitopes that elicit strong recall responses. J. Immunol. 2001;166:1114–1124. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.2.1114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Scriba TJ, Purbhoo M, Day CL, Robinson N, Fidler S, Fox J, Weber JN, Klenerman P, Sewall AK, Phillips RE. Ultrasensitive detection and phenotyping of CD4+ T cells with optimized HLA class II tetramer staining. J. Immunol. 2005;175:6334–6343. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.10.6334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Macmillan H, Norimine J, Brayton KA, Palmer GH, Brown WC. Physical linkage of naturally complexed bacterial outer membrane proteins enhances immunogenicity. Infect. Immun. 2008;76:1223–1229. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01356-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Homann D, Teyton L, Oldstone MB. Differential regulation of antiviral T-cell immunity results in stable CD8+ but declining CD4+ T-cell memory. Nat. Med. 2001;7:913–919. doi: 10.1038/90950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mebius RE, Kraal G. Structure and function of the spleen. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2005;5:606–616. doi: 10.1038/nri1669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Crispe IN, Dao T, Klugewitz K, Mehal WZ, Metz DP. The liver as a site of T-cell apoptosis: graveyard, or killing field? Immunol. Rev. 2000;174:47–62. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0528.2002.017412.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brown WC, Shkap V, Zhu D, McGuire TC, Tuo W, McElwain TF, Palmer GH. CD4+ T-lymphocyte and immunoglobulin G2 responses in calves immunized with Anaplasma marginale outer membranes and protected against homologous challenge. Infect. Immun. 1998;66:5406–5413. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.11.5406-5413.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lopez JE, Siems WF, Palmer GH, Brayton KA, McGuire TC, Norimine J, Brown WC. Identification of novel antigenic proteins in a complex Anaplasma marginale outer membrane immnogen by mass spectrometry and genomic mapping. Infect. Immun. 2005;73:8109–8118. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.12.8109-8118.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Palmer GH, Barbet AF, Musoke AJ, Katende JM, Rurangirwa F, Shkap V, Pipano E, Davis WC, McGuire TC. Recognition of conserved surface protein epitopes on Anaplasma centrale and Anaplasma marginale isolates from Israel, Kenya, and the United States. Int. J. Parasitol. 1988;18:33–38. doi: 10.1016/0020-7519(88)90033-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brown WC, Palmer GH, Lewin HA, McGuire TC. CD4+ T lymphocytes from calves immunized with Anaplasma marginale major surface protein 1 (MSP1), a heteromeric complex of MSP1a and MSP1b, preferentially recognize the MSP1a carboxyl terminus that is conserved among strains. Infect. Immun. 2001;69:6853–6862. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.11.6853-6862.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kovar M, Boyman O, Shen X, Hwang I, Kohler R, Sprent J. Direct stimulation of T cells by membrane vesicles from antigen-presenting cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:11671–11676. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0603466103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Admyre C, Johansson SM, Paulie S, Gabrielsson S. Direct exosome stimulation of peripheral human T cells detected by ELISPOT. Eur. J. Immunol. 2006;36:1772–1781. doi: 10.1002/eji.200535615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Colino J, Snapper CM. Exosomes from bone marrow dendritic cells pulsed with diptheria toxoid preferentially induce type I antigen-specific IgG responses in naïve recipients in the absence of free antigen. J. Immunol. 2006;177:3757–3762. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.6.3757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Giri PK, Schorey JS. Exosomes derived from M. bovis BCG infected macrophages activate antigen-specific CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in vitro and in vivo. PLoS ONE. 2008;3:e2461. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schorey JS, Bhatnagar S. Exosome function: from tumor immunology to pathogen biology. Traffic. 2008;9:871–881. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2008.00734.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hayashi N, Liu D, Min B, Ben-Sasson SZ, Paul WE. Antigen challenge leads to in vivo activation and elimination of highly polarized TH1 memory T cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2002;99:6187–6191. doi: 10.1073/pnas.092129899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Xu H, Wipsa J, Yan H, Zeng M, Makobongo MO, Finkelman FD, Kelso A, Good MF. The mechanism and significance of deletion of parasite-specific CD4+ T cells in malaria infection. J. Exp. Med. 2002;195:881–892. doi: 10.1084/jem.20011174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jenson JS, O’Connor R, Osborne J, Glasgow GB. Infection with Brugia microfilariae induces apoptosis of CD4+ T lymphocytes: a mechanism of immune unresponsiveness in filariasis. Eur. J. Immunol. 2002;32:858–867. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200203)32:3<858::AID-IMMU858>3.0.CO;2-E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dalton DK, Haynes L, Chu C-Q, Swain SL, Wittmer S. Interferon γ eliminates responding CD4 T cells during mycobacterial infection by inducing apoptosis of activated CD4 T cells. J. Exp. Med. 2000;192:117–122. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.1.117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Li X, McKinstry KK, Swain SL, Dalton DK. IFN-γ acts directly on activated CD4+ T cells during mycobacterial infection to promote apoptosis by inducing components of the intracellular apoptosis machinery and by inducing extracellular proapoptosis signals. J. Immunol. 2007;179:939–949. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.2.939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Demangel C, Britton WJ. Interaction of dendritic cells with mycobacteria: where the action starts. Immunol. Cell. Biol. 2000;78:318–324. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1711.2000.00935.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Grau GE, Piguet P-F, Vassalli P, Lambert P–H. Tumor necrosis factor and other cytokines in cerebral malaria: experimental and clinical data. Immunol. Rev. 1989;112:49–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1989.tb00552.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wright IG, Goodger BV. Pathogenesis of babesiosis. In: Ristic M, editor. Babeosis of Domestic Animals and Man. CRC Press; Boca Raton, FL: 1988. pp. 99–118. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gale KR, Waltisbuhl DJ, Bowden JM, Jorgensen WK, Matheson J, East IJ, Zakrzewski H, Leatch G. Amelioration of virulent Babesia bovis infection in calves by administration of the nitric oxide synthase inhibitor aminoguanidine. Parasite Immunol. 1988;20:441–445. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3024.1998.00169.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shoda LKM, Palmer GH, Florin-Christensen J, Florin-Christensen M, Godson DL, Brown WC. Babesia bovis-stimulated macrophages express interleukin-1β, interleukin-12, tumor necrosis factor-α, and nitric oxide and inhibit parasite replication in vitro. Infect. Immun. 2000;68:5139–5145. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.9.5139-5145.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Brayton KA, Kappmeyer LS, Herndon DR, Dark MJ, Tibbals DL, Palmer GH, McGuire TC, Knowles DP., Jr. Complete genome sequencing of Anaplasma marginale reveals that the surface is skewed to two superfamilies of outer membrane proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:844–849. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0406656102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]