Summary

Esthesioneuroblastoma is a rare tumour, for which a multimodal approach, including a combination of surgery and radiation, appears to provide the best disease-free and overall survival. Well-known for its tendency for local recurrence and distant spreading by both lymphatic and haematogenous routes, the most common sites of metastases are lungs and bones, followed by liver, spleen, scalp, breast, adrenals and ovary. One single case of metastasis to the trachea has been reported in the literature. The case is reported here of a patient who developed metastatic esthesioneuroblastoma to the trachea 18 months after primary surgery and radiation therapy. The patient was treated by two subsequent N-YAG laser endoscopic resections and chemotherapy.

Keywords: Trachea, Malignant tumours, Esthesioneuroblastoma, Tracheal metastasis

Riassunto

L’estesioneuroblastoma è un raro tumore, per il quale un approccio combinato comprendente chirurgia e radioterapia permette di ottenere la migliore sopravvivenza libera da malattia e la miglior sopravvivenza globale. Noto per la propensione alla recidiva locale e per la diffusione a distanza, per via linfatica ed ematica, le più comuni sedi di metastasi sono il polmone e l’osso, seguiti da fegato, milza, cuoio capelluto, mammella, surrene e ovaio. In letteratura un solo caso di metastasi tracheale è stato riportato sino ad oggi. Noi riportiamo il caso di una paziente che ha sviluppato una metastasi tracheale da estesioneuroblastoma 18 mesi dopo la chirurgia del primitivo e la radioterapia. La paziente è stata trattata con due successive resezioni endoscopiche con N-YAG laser e chemioterapia.

Introduction

Esthesioneuroblastoma (ENB), also known as olfactory neuroblastoma, is an uncommon neoplasm arising from the olfactory neuroepithelium of the upper nasal cavity at the interface with the anterior cranial fossa 1 2. This neurogenic tumour has very little in common with neuroblastomas elsewhere in the body. It accounts for 6% of nasal and paranasal sinuses tumours and for 0.3% of upper aerodigestive malignancies 3.

ENB occurs with a bimodal peak in the second and sixth decades of life and without predominance of sex or race. It is often locally aggressive, with symptoms related to local extension of the disease: nasal obstruction, intermittent epistaxis, local pain, headache, rhinorrhea, anosmia, diplopia. The mean time from the initial symptoms to diagnosis, by computed tomography (CT)-scan or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), is approximately 6 months 4.

Although ENB is uncommon, some consistent features of the disease have been established: local recurrences in 30% of patients, cervical nodes metastases in 23%, distant metastases in 8% of cases 5 with sites involved including lung, liver, eye, parotid, central nervous system (CNS), bone, adrenal gland, spleen, scalp, breast, ovary, aorta 6 7. A single case of metastasis to the trachea has so far been reported in the literature 7.

The first and most common staging system was developed by Kadish et al. 8 then modified by Morita et al. 9 to obtain a system that divides tumours into four groups:

tumour limited to the nasal cavity;

tumour involving the nasal and paranasal sinuses;

tumour involving cribriform plate, base of the skull, orbit or intra-cranial cavity;

tumour with metastasis to cervical nodes or distant sites.

Other staging systems have also been used, but no single staging classification has been universally adopted for this tumour to date, as the prognostic utility of each system has not been proved 10.

Cantù et al. 11 suggested a classification system for ethmoid tumours, called INT classification (Istituto Nazionale dei Tumori classification) involving the anterior skull base. This system is based upon anatomic, and not only on pathologic, criteria, it considers the possibilities and limitations of standard treatment for ethmoid tumours in achieving radical resection and it satisfies a main goal of tumour staging, that is i.e., the progressive worsening of prognosis for different classes.

According to the histopathological features ENB was divided, by Hyams et al. 12 into four grades of differentiation: from grade I for well differentiated forms to grade IV for undifferentiated forms.

Universal treatment of ENB has not yet been recognized: surgery, with a combined transfacial and transcranic approach, followed by radiotherapy at a dose of 60 Gy, should achieve the best results. In some cases, stereotactic radiotherapy can be considered. In recent years, endoscopic microsurgical techniques have been employed in the treatment of ENB. With complete endoscopic surgical resection, followed by radiation therapy, local recurrence, morbidity and cosmetic deformity have been minimized 13 14. Another novel therapeutic approach combines endoscopic sinus surgery and Gamma Knife radiosurgery. This treatment has led to favourable results and can be considered a promising approach 15. Chemotherapy is employed in patients with recurrent or metastatic disease and in the neoadjuvant setting to reduce the extent of tumour before surgery.

The mean 5-year survival, according to the Kadish-Morita staging system, is approximately 72% for group A, 59% for B, 47% for C, 29% for D. According to the histopathologic classification, mean 5-year survival is 56% for grades I/II and 25% for grades III/IV, the presence of nodal metastases at presentation being the most important prognostic factor for survival (5-year overall survival is reported to be 29% in patients with nodal metastases at presentation vs 64% in patients without metastases). Local recurrence can occur even more than 10 years after primary treatment: therefore long-term follow-up is mandatory 6.

Loco-regional and distant spreading are through the lymphatic and haematogenous routes. The possible routes of metastases to the trachea are discussed, and previous reports of tumours metastatic to the trachea are reviewed.

Case report

In June 1998, a 50-year-old female was referred to the IRCCS Istituto Nazionale dei Tumori, Milan, on account of progressive left nasal obstruction and rhinorrhoea.

A CT scan of the craniofacial district revealed a polypoid mass projecting into the lumen of the left nasal cavity. A histological diagnosis of adenoid-cystic carcinoma was formulated according to a trans-nasal biopsy.

Pre-operative staging of disease did not reveal any distant metastases, therefore the patient underwent anterior craniofacial resection.

The definitive histological diagnosis was not in agreement with the biopsy sample, identifying an olfactory neuroblastoma, staged T2 N0 M0 (WHO Staging System).

Adjuvant radiotherapy was performed with a total dose of 60 Gy.

The patient was observed at regular follow-up until January 2000, when she was admitted to our Institution for more severe dyspnoea.

A chest X-ray excluded pneumonia or hypertensive pneumo-thorax.

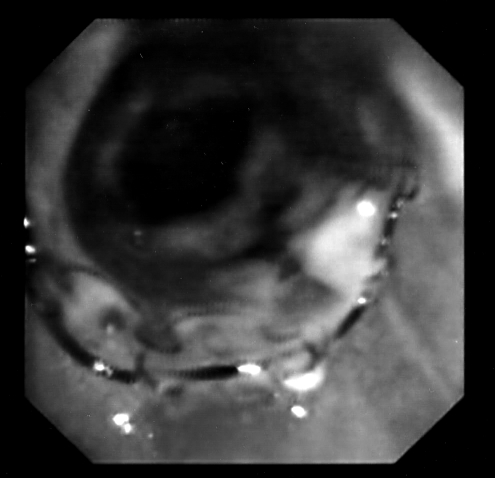

Due to hypoxia, at arterial blood gas measurement, and acute respiratory failure, the patient was submitted to an emergency flexible endoscopic laryngo-tracheal examination (Fig. 1a), which reavealed stenosis of the trachea, due to the presence of a mass penetrating into the tracheal lumen. Bleeding from two detached mucous vegetations was detected 5 cm below the glottis. The first was located on the left side of the tracheal lumen, the second on the pars membranacea of the tracheal wall. The longitudinal extension was 2 cm, resulting in a lumen reduction of 95%.

Fig. 1a.

Endoscopic imaging of endotracheal metastasis at first presentation. Two mucous vegetations are evident, causing a 95% reduction of tracheal lumen.

A N-YAG laser resection of the mass was performed, with subsequent introduction of two expansible metal stents (Nitinol stents, introduced by means of a rigid endoscope), diameter 1.4 x 4 cm), leading to a satisfactory grade of tracheal patency (Fig. 1b) and complete recovery from respiratory symptoms. A CT-scan of the thorax showed a significant tissutal thickening of the tissue between the trachea and oesophagus, without evidence of mediastinal or lung metastases (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1b.

Endoscopic imaging after N-Yag laser resection and double stent placement. Patency of tracheal lumen is achieved.

Fig. 2.

Post-treatment CT-scan: significant tissue thickening between trachea and oesophagus is evident. Metal stent allows optimal patency of trachea.

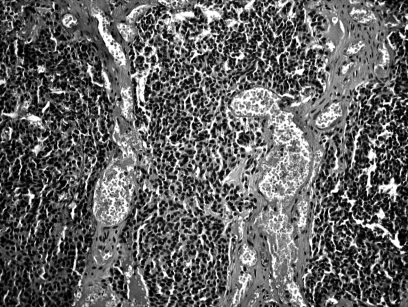

A biopsy specimen of the mass revealed ENB, histologically identical to the primary tumour (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

E.E. specimen: in typical neuroendocrine-type esthesioneuroblastoma, low-power microscopy reveals rather monitonous-looking cells arranged in lobules on delicate fibrovascular stroma. Some esthesioneuroblastomas contain true Homer-Wright rosettes and axons may be demonstrated with special stains.

Further endoscopic laser treatment was performed, a few days later, to remove necrotic tissue and to improve tracheal patency.

MRI of the brain, whole body bone-scan and oesophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) did not reveal any other sites of disease.

One month later, the patient presented recurrence of increasing respiratory stress and a fibroendoscopic laryngo-tracheal examination demonstrated a new stenosis of the trachea, just above the first tracheal stent, with a longitudinal extension of 2 cm.

Photocoagulation with N-YAG laser was again performed and a third metal stent was introduced.

Due to the aggressive behaviour of the disease, the patient underwent 2 cycles of systemic chemotherapy with epirubicine and hiphosphamyde.

A further fibroendoscopic laryngo-tracheal examination, in March 2000, showed normal tracheal canalization and no further relapse of disease.

Another four cycles of chemotherapy were performed.

Two months later, MRI of the neck and thorax revealed the presence of pathological tissue on the left wall of the trachea and posteriorly, around the initial tract of the right superior lobar stump. The tracheal carena was deformed and able to capture gadolinium.

Following evidence of multiple sites of loco-regional relapse of the disease, the patient underwent palliative radiotherapy

Three months later, multiple hepatic metastases were found. The patient died on account of progression of the disease both loco-regionally and at distant sites.

Discussion

Treatment of tracheal metastases, in ENB, is no different from any other neoplastic stenoses of the airways, clinically characterized by severe respiratory failure.

The first publication on endotracheal metastases goes back to 1954, when Divertie et al. 16 described a case of metastatic colorectal adenocarcinoma.

These metastases are very unusual, representing 2-5% of all autopsy surveys in patients dying from cancer 17.

More recently, with improvements in endoscopic techniques, it is possible to obtain earlier and more precise diagnosis, even if all cases of endotracheo-bronchial metastases have to be considered as advanced disease with an unfavourable prognosis.

Many different kinds of tumours can metastasize to the trachea: breast and colorectal carcinoma being the most common, melanoma, thyroid carcinoma, sarcoma and hepatocarcinoma.

A few Authors have described endobronchial metastases from distant malignancies, generally as sporadic events 17–21.

The first case of tracheal metastases of ENB was published in 1987, by Franklin et al. 7 who reported a case similar to that described here: a patient submitted to craniofacial resection who presented a single site of relapse to the trachea one year later.

The Authors also presented a detailed and pertinent review of the literature regarding tracheal primitive neoplasms and mestastases, from which the rarity of the primitive forms are primarily related (< 0.1% among all patients who died from cancer) compared with those in a laryngeal site, which are 75 times more frequent.

From a clinical point of view, an endotracheal mass produces characteristic symptoms when the tracheal lumen is reduced to 75%. For this reason, diagnosis is usually achieved only when the tumour is already of large dimensions.

A significant difference between tracheal and endo-bronchial lesions is that, in the former, inspiratory “cornage is typically present”, which is absent in the latter.

Tracheal deviation is rarely provoked by an endotracheal mass; instead, this is a common finding in an extraluminal mass arising in the lung, oesophagus or thyroid.

Following correct evaluation of an endotracheal tumour, it is necessary to plan appropriate treatment aimed at removing the obstruction and preserving endoluminal patency.

The first step in the treatment of tracheal malignancies consists in establishing the airway, by means of endoscopic removal, photodynamic therapy, electro-coagulation and endo-cavitary brachitherapy.

Patients’ clinical features, entity of the tracheal obstruction, number of lesions, experience in using one of these techniques, will determine the choice of therapy.

In our patient, N-Yag laser was used and was repeated each time relapse of the disease occurred, until possible 22.

Once the airway has been established, it is necessary to introduce metal stents compatible with eventual radiation treatment.

Following endoscopic resection, a clinical check-up is necessary to confirm correct placement of the stent and to exclude relapse of the disease. When necessary, the endoscopic procedure can be repeated, eventually associated with chemo or radiotherapy.

The patient described in this report achieved immediate recovery of shortness of breath and a satisfactory local control of the disease. Prognosis of the patient was determined by distant metastases, despite multiple local recurrences.

As far as concerns the pathogenesis of the peculiar location of these metastases, we can exclude the possibility of insemination of the trachea, by ethmoidal tumoural cells, during oro-tracheal intubation, when the patient undergoes anterior cranio-facial resection for primary tumour. The lymphatics, as a route giving rise to metastases in the trachea has been definitely ruled out, following evidence that the lymphatic circulation is completely independent in the head/neck and the tracheo-bronchial anatomic districts, as demonstrated by Welsh in 1964 23.

It is more likely that the trachea is reached by ENB cells through the blood circulation, as is the case for metastases to the trachea from a carcinoma.

Also in the present case, when considering the aggressive behaviour developed by the disease, the detection of metastasis seems to have matched the onset of haemato- genous diffusion.

Research on multifaceted aspects of micrometastasis, including proliferation and differentiation of various clones from the primary tumour, the acquisition of adhesion molecules, the process of lymphangiogenesis vs. angiogenesis, and host interaction with the microscopic tumour, may lead to a better understanding of the mechanisms of metastasis.

In this perspective, future biological models of clinical cancer behaviour will have to incorporate aspects focusing on understanding the metastatic cascade, and particularly the host factors that permit progressive growth from micrometastases to clinical metastases.

Conclusions

Endotracheal obstruction, due to primary carcinoma or metastases from extrapulmonary tumours, is a rare and life-threatening complication in cancer patients. The trachea is an extremely rare location for metastases from non-lung tumours. The present report refers to a patient with ENB who developed almost complete obstruction of the trachea and who was successfully managed by endoscopic resection.

To our knowledge, this is the second report describing metastatic tracheal dissemination from ENB.

References

- 1.Klepin HD, McMullen KP, Lesser GJ. Esthesioneuroblast-oma. Curr Treat Options Oncol 2005;6:509-18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Davaiah AK, Larsen C, Tawfik O, O’Boynick P, Hoover LA. Esthesioneuroblastoma: endoscopic nasal and anterior craniotomy resection. Laryngoscope 2003;113:2086-90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ferlito A, Rinaldo A. Rhys-Evans PH. Contemporary clinical commentary: Esthesioneuroblastoma: An update on management of the neck. Laryngoscope 2003;113:1935-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dias FL, Sà GM, Lima RA, Kligerman J, Leoncio MP, Freitas EQ, et al. Patterns of failure and outcome in esthesioneuroblastoma. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2003;129:1186-92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chao KSC, Kaplan C, Simpson JR, Haughey B, Spector GJ, Sessions DG, et al. Esthesioneuroblastoma: the impact of treatment modality. Head Neck 2001;23:749-57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bradley PJ, Jones NS, Robertson I. Diagnosis and management of esthesioneuroblastoma. Curr Op in Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2003;11:112-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Franklin D, Miller RH Bloom MGK, Easley J, Stiernberg CM. Esthesioneuroblastoma metastatic to the trachea. Head Neck Surg 1987;10:102-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kadish S, Goodman M, Wang CC. Olfactory neuroblastoma. A clinical analysis of 17 cases. Cancer 1976;37:1571-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Morita A, Ebersold MJ, Olsen KD, Foote RL, Lewis JE, Quast LM. Esthesioneuroblastoma: prognosis and management. Neurosurgery 1993;32:706-14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jethanamest D, Morris LG, Sikora AG, Kutler DI. Esthesioneuroblastoma. A population-based analysis of survival and prognostic factors. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2007;133:276-80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cantù G, Solero CL, Miceli R, Mariani L, Mattavelli F, Squadrelli-Saraceno M, et al. Which classification for ethmoid malignant tumors involving the anterior skull base? Head Neck 2005;27:224-31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hyams VJ. Papillomas of the nasal cavity and paranasal sinuses. A clinicopathological study of 315 cases. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 1971;80:192-206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Castelnuovo P, Pagella F, Delù G, Benazzo M, Cerniglia M. Endoscopic resection of nasal hemangiopericytoma. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 2003;260:244-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Buchmann L, Larsen C, Pollack A, Tawfik O, Sykes K, Hoover LA. Endoscopic techniques in resection of anterior skull base/paranasal sinus malignancies. Laryngoscope 2006;116:1749-54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Unger F, Haselsberger K, Walch C, Stammberger H, Papaefthymiou G. Combined endoscopic surgery and radiosurgery as treatment modality for olfactory neuroblastoma. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 2005;147:595-601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Divertie MB, Schmidt HW. Tracheal obstruction from metastatic carcinoma of the colon: report of case. Proc Staff Meet Mayo Clin 1954;29:403-5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Salud A, Porcel JM, Rovinosa A, Bellmunt J. Endobronchial metastatic disease: analysis of 32 cases. J Surg Oncol 1996;62:249-52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shapshay SM, Strong MS. Tracheobronchial obstruction from metastatic distant malignancies. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 1982;91:648-51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Heitmiller RF, Marasco WJ, Hruban RH, Marsh BR. Endobronchial metastases. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1996;106:537-42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Omerod LP, Horsfield N, Alani FS. How frequently do endobronchial secondaries occur in an unselected series? Respir Med 1998;92:599-600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Katsimbri PP, Bamias AT, Froudarakis ME, Peponis IA, Constantantopoulos SH, Pavlidis NA. Endobronchial metastases secondary to solid tumors: report of eight cases and review of the literature. Lung Cancer 2000;28:163-70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Spinelli P, Mancini A, Calarco G, Spinelli A. The use of laser in surgical oncology. From lasers in medicine, surgery and dentistry. European Medical Association 2003. p. 499-509. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Welsh LW. The normal laryngeal lymphatics. Ann Otol 1964;73:569-83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]