Abstract

Motivation: A major limitation in modeling protein interactions is the difficulty of assessing the over-fitting of the training set. Recently, an experimentally based approach that integrates crystallographic information of C2H2 zinc finger–DNA complexes with binding data from 11 mutants, 7 from EGR finger I, was used to define an improved interaction code (no optimization). Here, we present a novel mixed integer programming (MIP)-based method that transforms this type of data into an optimized code, demonstrating both the advantages of the mathematical formulation to minimize over- and under-fitting and the robustness of the underlying physical parameters mapped by the code.

Results: Based on the structural models of feasible interaction networks for 35 mutants of EGR–DNA complexes, the MIP method minimizes the cumulative binding energy over all complexes for a general set of fundamental protein–DNA interactions. To guard against over-fitting, we use the scalability of the method to probe against the elimination of related interactions. From an initial set of 12 parameters (six hydrogen bonds, five desolvation penalties and a water factor), we proceed to eliminate five of them with only a marginal reduction of the correlation coefficient to 0.9983. Further reduction of parameters negatively impacts the performance of the code (under-fitting). Besides accurately predicting the change in binding affinity of validation sets, the code identifies possible context-dependent effects in the definition of the interaction networks. Yet, the approach of constraining predictions to within a pre-selected set of interactions limits the impact of these potential errors to related low-affinity complexes.

Contact: ccamacho@pitt.edu; droleg@pitt.edu

Supplementary information: Supplementary data are available at Bioinformatics online.

1 INTRODUCTION

Zinc finger (ZF) transcription factors are the largest family of nucleic acid binding factors in eukaryotes (Laity et al., 2001). Due to the relatively promiscuous interactions of these factors (Wolfe et al., 2000), the majority of their cognate DNA binding sites are still poorly resolved. Indeed, a major limitation on the analysis of ZF–DNA interactions and other factors is the lack of reliable experimental techniques to map their specificity to other targets (Camenisch et al., 2008). Given this vacuum, the development of computational methods to assist in the identification of protein–DNA physical interactions can play an important role in revealing the molecular basis of how genes are activated/repressed, leading to normal cell function or to the acquisition of specific pathogenic traits.

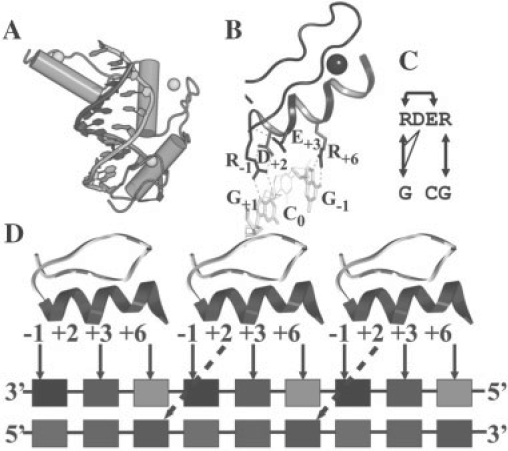

The regularity of the structure of C2H2 ZF genes (Pavletich and Pabo, 1991; Pavletich and Pabo, 1993; Segal et al., 2006) and the dominant binding mode (Elrod-Erickson et al., 1996; Elrod-Erickson et al., 1998) make this family an ideal system to be studied both theoretically and experimentally. The classical Early Growth Factor (EGR) gene, zif268 (Fig. 1) shows the main recognition motif, a helix binding to the major groove of the DNA. Three ZFs of EGR wrap around the major groove of DNA (Fig. 1A). This gene was found to have the consensus DNA sequence  for ZF binding, where a high affinity for guanine in DNA recognition is frequently observed. The recognition motif typically involves helix positions -1, +3 and +6 (numbered from the start of the helix), each residue coordinating one nucleotide (Fig. 1B). However, high-resolution crystal structures (Elrod-Erickson et al., 1996) have also shown that water-mediated contacts and bonds to position (pos.) +2 might also occur. It is important to note that other interactions with DNA bases showing non-classical binding modes are also physically possible, but less common (Siggers et al., 2005; Wolfe et al., 2000).

for ZF binding, where a high affinity for guanine in DNA recognition is frequently observed. The recognition motif typically involves helix positions -1, +3 and +6 (numbered from the start of the helix), each residue coordinating one nucleotide (Fig. 1B). However, high-resolution crystal structures (Elrod-Erickson et al., 1996) have also shown that water-mediated contacts and bonds to position (pos.) +2 might also occur. It is important to note that other interactions with DNA bases showing non-classical binding modes are also physically possible, but less common (Siggers et al., 2005; Wolfe et al., 2000).

Fig. 1.

Interactions of ZF-DNA triplets. (A) EGR–DNA complex (Elrod-Erickson et al., 1996). (B) Binding mode of finger I of EGR. H-bonds are shown as pink dashed lines. Binding site residues are indicated. (C) 2D representation of the interaction network of finger I of EGR to its DNA target. Inter-molecular H-bonds are indicated by arrows between residues and DNA, side-chain backbone and side-chain–side-chain intra-molecular bonds are noted as arrows over the top and lines below the protein sequence, respectively. (D) Typical interaction network of an EGR-like ZF. H-bonds typically form at positions −1, +2, +3 and +6 with respect to the beginning of the helix. Dashed lines in fingers II and III from pos +2 show the possible H-bonds by Ser residues to C (finger II) or A (finger III) in the complementary strand.

Modeling protein interactions is a challenging problem in computational structural biology. Indeed, despite recent advances in the field (see, e.g. Mendez et al., 2005), empirical potentials are still quite limited (Camacho et al., 2006). For instance, the best outcome on a recent benchmark (Bueno et al., 2007b) of some of the best known methods (machine learning, physical and knowledge based) to predict changes in folding free energy for single mutants of aliphatic side chains was a mere 72% success rate on Δ Δ Gs within ± 1 kcal/mol of the experimental data. The reasons for this dismal outcome are the same for protein–DNA interactions, i.e. the poor sampling of complexes (Morozov et al., 2005) and the difficulty in assessing changes in polar and water-mediated interactions (see, e.g. Bueno and Camacho, 2007a; Ernst et al., 1995). More interestingly, the aforementioned benchmark revealed that all methods resulted in more or less equivalent predictions despite the fact that the number of free parameters varied widely between 5 and 40, reflecting the poor assessment of model over-fitting.

Recently, a 2 year effort mapping structural models to high-quality binding affinity data of ZF/DNA complexes (Temiz and Camacho, 2009) led to the development of a novel interaction code. The key feature of this approach is the pre-selection of structural models based on distance constraints as opposed to optimizing an imperfect scoring function. A 10 parameter ZF/DNA atomic interaction code was developed using five crystals (Elrod-Erickson et al., 1996; Elrod-Erickson et al., 1998; Kang, 2007) as templates for homology models of ZF structures and binding modes, a minimal set of binding affinities from seven mutants of finger I of EGR (Liu and Stormo, 2005) and three mutants of finger III (Bae et al., 2003). Predictions on independent validation sets resulted in structural models for the mutant complexes, as well as in differences between mutant (multiple amino acid and nucleotide mutations) and wild-type (WT) binding affinities, ΔΔGbind, of just a few tenths of a kcal/mol.

From a methodological point of view, the code assumed that the experimental ΔΔGbind of the selected mutants were exact. This is not a common assumption for this type of data. However, the manual optimization of a full binding affinity database of feasible structural models (referred to as ‘submodels’) involved the difficult task of checking an exponentially large number of submodel combinations. For instance, Figure 2 shows a simple example for two data points where each mutant has three different arrangements of possible inter-molecular bonds, leading to 32 combinations. For all 35 mutants available for EGR finger I (Liu and Stormo, 2005), one has roughly 335 possible ways of minimizing ΔΔGbind. To provide a mathematical framework to solve this type of problems and validate the experimentally based approach to decode protein interactions, we develop a novel non-linear mixed integer programming (MIP) method which optimizes over all mutants of EGR finger I.

Fig. 2.

Sketch of three feasible submodels for two mutants, and the nine possible combinations (I,…, IX) in which, depending on the value and number of parameters, different submodels minimize the binding free energy (see text). Arrows correspond to H-bonds, circles and squares correspond to desolvation penalties and half open or filled triangles indicate the absence or presence of excess water molecules near the indicated interaction. For details and color codes see (Temiz and Camacho, 2009).

The scalability of the method allows us to probe the over-fit and under-fit of the method by solving interaction codes with different number of parameters i.e. from 12 interactions all the way down to five independent variables. The resulting codes strongly support the robustness of the physical parameters obtained in (Temiz and Camacho, 2009), improving the correlation coefficient R2 to 0.998 with just seven free parameters (minimum over-fitting). Further decreasing the number of parameters negatively under-fits the predictions in the validation sets. To demonstrate that the MIP is independently capturing the underlying interactions, we systematically eliminated all seven finger I mutants used to map the original code, obtaining in a few minutes almost equivalent interaction codes. Finally, given that the homology (sub)models of finger II and III mutants of EGR involved the extra challenge of predicting water-filled cavities at the binding interface, we show how one can use the unprecedented accuracy of our MIP-based code to further validate water positions.

2 METHODS

2.1 ZF/DNA interactions

The basic assumption of the experimentally based approach to represent ZF/DNA interactions (Temiz and Camacho, 2009) is that changes in the affinity of a complex due to mutations are uniquely determined by changes in the contact energies and solvation factors between the structures. Based on the above, we developed the following scheme to decode the interaction potential:

Build homology submodels of mutant TF based on templates from known complex structures. Based on the conservation of the tetrahedral coordination of the zinc ion and helical binding domain, predicting both quality alignment and backbone submodels is relatively straightforward (Prasad et al., 2003).

Perform MD simulations of the homology submodels in the absence of DNA in explicit solvent to readily identify feasible intra-molecular hydrogen bonds (H-bonds).

ZF/DNA homology submodels are built by superposition in crystallographically validated binding modes. DNA structures considered in our submodels are from DNA bound to ZFs; if not available, DNA triplets are taken from the PDB. Inter-molecular H-bonds are deemed feasible if side chain conformations sampled from the MD in the absence of DNA are within an empirical 4 Å distance threshold of the DNA acceptor/donor. With this pre-screening, we define a series of submodels of feasible low energy combinations of intra- and-inter-molecular H-bond networks for each complex (see, e.g. Fig. 2).

Unless crystal information is available, water molecules are placed in all cavities that can fit one. These waters are used to predict whether bonds are more or less exposed to solvent, and to determine whether the accessibility water factor is applicable (see below).

- Effective free energies are assigned to all H-bonds: eij to inter-molecular H−bonds, δi to atomic desolvation penalties triggered by unmatched hydrogen bond donors or acceptors and buried hydrophobic residues. These interactions are further modulated by a novel water factor λw that is applied depending on the number of water molecules contacting the atomic interactions. Thus, given a submodel, these assignments allow us to compute the binding energy as:

the water factor is f(λw)=(1 − λw) for multiple waters surrounding a H-bond and 1/(1 − λw) for a water free bond. Then, the change in binding free energy relative to a reference state (often, the wild type (WT) configuration) is ΔΔGbind=ΔGCalc (submodel) − ΔGCalc (WT), which is related to biochemical binding data using the ratio of the dissociation constants Kd as

(1)

where R and T are the gas constant and temperature, respectively, and Mut refers to the mutation relative to WT.

(2)

Using just seven mutant complexes of finger I [see ref. (Temiz and Camacho, 2009) for details], the interaction code was solved for a seven parameter interaction potential. These include: (i) three H-bonds, (a) the two (bidentate) H-bonds between Arg and Guanine, e1 ≡ Arg = G, which is assumed to be twice the strength of both a single K − G H-bond and of a side chain phosphate backbone (bb) H-bond, (b) the bidentate e2 ≡ Gln = A H-bond, which is assumed to have the same strength as Asn=A with the strength of individual H-bonds (e.g. Asn.OD-A) partitioned proportional to their partial charges, (c) e3 ≡ Asp-C H-bond used to estimate all bonds involving Asp side chains; (ii) three desolvation penalties (a) e4 ≡δNH2 for unmatched side chain NH2 groups, (b) e5 ≡ δOD for a free side chain with an unmatched oxygen group at the binding interface from Gln, Asn, Glu or Asp and (c) e6 ≡ δHB for burying a sc-sc H-bond between any two interface residues at positions −1, +2, +3 or +6 and leaving at least one oxygen unmatched; and (iii) the water factor λw, corresponding to the fraction by which the transition state of H-bonds exposed to extra waters is decreased. Three other mutants from finger III of EGR were used to model interactions not present in finger I.

2.2 Mixed integer programming

Mixed integer programming (MIP) is a mathematical tool which can be used to find solutions to problems involving some combinatorial structure. MIP formulation may include both integer and continuous variables, constraints (which typically enforce restrictions on permissible variable combinations), as well as an objective function, which provides for a means of evaluating the quality of a given solution satisfying the constraints (Floudas and Pardalos, 2009; Pardalos and Resende, 2002). Three standard methods for solving different classes of MIPs include exact methods [e.g. branch-and-bound, branch-and-cut, branch-and-price, cutting plane (Nemhauser and Wolsey, 1988)], metaheuristic techniques (Glover and Kochenberger, 2003; Vazirani, 2001), as well as approximation algorithms (Vazirani, 2001). MIPs have being successfully applied to a broad range of problems including bioinformatics (Floudas and Pardalos, 2000), protein design (Fung et al., 2005) and structural alignment (Dundas et al., 2007).

2.3 Mapping interaction code into a MIP

Variable definition (Fig. 3):

ek: parameters in the interaction code (0 ≤ ek ≤ 4), H-bonds and desolvation factors;

λw: unknown water factor (0 ≤ λw ≤ 1);

xij = 1 if submodel j ⊂Si (where Si is a list of feasible submodels for ZF/DNA complex i) is assigned to complex i; xij = 0 otherwise.

Fig. 3.

Mapping of MIP parameters onto a free energy landscape of four submodels (‘j’) of complex (‘i’) QDNR/GAC. The condition that only one submodel minimizes the free energy is imposed by the constraint Σjxij = 1. H-bonds are represented by two letters, the first letter corresponding to the residue and the second the nucleotide. In practice, the arrangement of submodels on the funnel is given by the solution of the MIP application.

Data modeling:

Submodel j(∈ Si) for i is defined as the sum of the interactions of the submodel relative to a reference, i.e. ∑kwijk(λw)ek, where wijk is either a known coefficient or a known function of λw. When ek is not present, wijk is defined as 0.

ΔΔGi: experimental change in binding energy for complex i.

Basic MIP optimization formulation:

- Objective function minimizes binding energy over all complexes:

(3) - the constraint that exactly one submodel is correct for each complex i:

(4) - the constraint that the correct submodel for each complex i has the lowest energy of all submodels for that complex:

for all i, j ∈ Si, for all ℓ ∈ Si and ℓ ≠ j;

(5) - and constraints on type and bounds of variables:

(6)

Equivalent non-linear mixed 0–1 reformulation of (3-6):

- Formulation (3)-(6) is simplified by reformulating the non-linear integer program into a mixed integer problem, which is linear for a fixed λw. Objective function (3) is replaced by:

where Ei is ΔΔGi and new variables ti serve to eliminate the non-linear absolute value terms in (3). Depending on the sign of Ei − ∑j∈Si yij, minimization of (7) yields either ti≥Ei−∑j∈Si yij or ti≥−Ei+∑j∈Si yij ∀i.

(7)

Note that we still retain the constraint (4).

New variables yij=xij · ∑k wijk (λw)ek serve to linearize the non-linear terms inside absolute values in (3) via the following constraints (8)-(9), which force yij to be equal to ∑k wijk (λw)ek if xij=1 and 0 otherwise:

| (8) |

| (9) |

where Mij is a constant chosen to be large enough to give a valid upper bound on variable yij.

Formulation (4), (7)-(11) is a much simplified version of (3)–(6). While it is still non-linear on the parameter λw, we can further transform it into a standard (linear) MIP through a straightforward discretization-linearization procedure.

3 RESULTS

3.1 Solving MIP formulation to decode protein interactions

While formulation (7)–(11) eliminates the difficulties of the absolute values present in the objective (3) as well as non-linear constraints (5), there remains the presence of non-linearities in the ∑k wijk(λw)ek expressions. However, these non-linearities always appear in the form of a product of some ek parameters together with expressions involving λw. By representing continuous parameter λw as its binary representation, we are able to introduce further linearizations which transform the problem into a mixed integer program without any non-linearities.

Assuming we desire to represent λw within accuracy ε = 10−p, where p is some positive integer, then we need exactly

| (12) |

binary variables zℓ ∈ {0, 1}, so that λw≈∑ℓ=1Z2−ℓzℓ.

The products involving λw and ek appear in two distinct forms: (a) (1−λw)ek and (b) ek/(1−λw). To reformulate (a) using the binary representation of λw, any product (1−λw)ek can be represented as ek−λwek=ek−∑ℓ=1Zek2−ℓzℓ, where each ek2−ℓzℓ is a product of a continuous variable ek and binary variable zℓ. Let cℓk=zℓek, ℓ=1,…, Z, where the equality over non-linear products is imposed via a standard linearization technique using four additional constraint sets, see, e.g. (Prokopyev et al., 2005; Wu, 1997). Then (a) can be rewritten as ek−∑ℓ=1Z2−ℓcℓk. For the reformulation of (b), first let uk=ek/(1−λw). Then we can equivalently write ek=uk−λwuk. The term λwuk can be linearized in the same manner as previously described; let vℓk=zℓuk, ℓ=1,…, Z. Then by enforcing ek=uk−∑ℓ=1Z2−ℓvℓk, together with the additional four constraint sets on the vℓk variables, we can replace any occurrence in the form of expression (b) with uk. The four additional constraint sets necessary to enforce the equality of cℓk=zℓek, ℓ=1,…, Z and vℓk=zℓuk, ℓ=1,…, Z, respectively, are 0≤cℓk≤ek and ek−4(1−zℓ)≤cℓk≤4zℓ (for cℓk), and 0≤vℓk≤uk and uk−Mk (1−zℓ)≤vℓk≤Mkzℓ (for vℓk), where Mk is a large enough constant upper bounding uk.

After the aforementioned discretization-linearization procedure is performed, we obtain a linear mixed 0–1 programming problem, which can be tackled utilizing any standard MIP solver, e.g. CPLEX (ILOG, 2007). Each solution in our computational experiments was obtained within 30 min using a Dual-core Intel Xeon machine with 3 GB of RAM.

3.2 Avoiding over-fitting

We use the MIP formulation to optimize a 12 parameter interaction code (six H-bonds, five desolvation penalties and the water factor λw), mapping the 35 mutants of EGR finger I (Liu and Stormo, 2005). In Figure 4, we compare the MIP solution to the parameters obtained based on Equation (2), i.e. directly reading the interactions from well-defined mutants [no optimization; see (Temiz and Camacho, 2009)], as well as the corresponding correlation coefficient R2. It is important to stress that these parameters are all fundamental interactions (H-bonds and desolvation energies), including the novel water accessibility factor λw that corresponds to an implicit solvation parameter. For a 12 parameter representation, we obtain a correlation coefficient R2=0.99857.

Fig. 4.

Convergence of MIP optimization code based on EGR mutants of finger I. Top panel shows the R2 correlation coefficient as a function of the number of parameters. Lower panel displays changes in the optimal parameters as equivalent parameters are collapsed into one. For comparison, we show the results of (Temiz and Camacho, 2009) with no optimization (boxed points and black square). The two symbols for six parameters correspond to whether a H-bond or a desolvation penalty is further eliminated as a free parameter.

Upon inspection of the results, one immediately notices possible correlations on the parameters that in hindsight could easily correspond to chemically equivalent interactions. Hence, the power of our MIP formulation is perhaps best reflected in that testing this possibility, say, whether the desolvation penalty of an unmatched NH (δNH) is half that of a NH2 (δNH2) group, is as simple as introducing one additional constraint, i.e. δ NH2=2δNH. The new set of parameters with now 11 parameters is shown in Figure 4, resulting in a R2=0.99855. Further analysis of the code in Figure 4 suggests an equivalence between a single H-bond of Arg-G and a Arg-phosphate DNA backbone H-bond, followed by matching the Arg-A and Arg-G bonds by simply scaling the bonds according with the AMBER (Cornell et al., 1995) partial charges of the different nucleotides A and G. The elimination of these two free parameters yields an almost identical R2 value.

Although the chemistry behind the H-bonds Gln=A and Asn=A is identical, our parameters suggest that the Gln=A bonds are slightly weaker, consistent with the extra entropy loss entailed by the larger Gln side chain. Nevertheless, we assess the impact of equating the strength of these two sets of H-bonds, obtaining almost no change in the quality of our predictions. Finally, equating an oxygen desolvation from Asp, Gln and Asn results in a seven parameter potential with R2=0.9983, as compared with the same parameters decoded from Equation (2) using individual mutants R2=0.9975.

It is important to emphasize that the solutions of the MIP formulation not only extract an accurate interaction code but also predict the interaction submodels that minimize the binding free energy of each complex. For instance, for 12 parameters, the combination of submodels V in Figure 2 minimized the free energy, whereas for 9 parameters submodels II are selected. It is only with seven parameters that the MIP solution converged to the pair of submodels in I. The shift from one set of optimal submodels to another is expected. In fact, this is what makes the problem of optimizing a structure-based energy score difficult (i.e. different set of parameters lead to possibly different minima). However, contrary to other methods, our approach benefits from searching for the optimal solution among a set of feasible pre-defined structures (e.g. Fig. 3) such that predictions are at least consistent with known protein–DNA structures.

Besides eliminating parameters, our approach could as easily eliminate mutants. Supplementary Table S1 shows the MIP results for seven parameters after the systematic elimination of all seven finger I complexes used to map the original code, demonstrating the underlying consistency of the parameters and not just the fact that we have already found a good solution based on selected mutants. Moreover, we note that for all the MIP solutions, the submodels that optimized the objective function did not change.

Our approach to reduce over-fitting is somewhat similar to iterative backward elimination, a standard technique in regression to remove superfluous parameters. However, in general this phenomenon is virtually impossible to eliminate. The results of any such prediction technique which minimizes the distance between observed and fitted values (including our MIP formulation) are fundamentally influenced by multiple factors, including the criteria by which we minimize error, as well as the quantity and accuracy of experimental data. While minimizing the L2-norm (least squares) is a standard means to minimize residual error, our alternate choice to minimize the L1-norm (least absolute values) is also a widely accepted approach to minimize error, and has the further advantage of making our formulation more amenable to the subsequent linearizations that we implement. A distinct advantage of our applied exact solution technique versus other possible heuristic approaches is that it guarantees the global optimality of the obtained solution for the considered mathematical programming formulation, rather than just an adequate solution. Hence, our contribution for this paper is at least as much the introduction of the novel MIP optimization approach to solve such problems, as it is in getting definitive results on the protein–DNA interactions with the initial dataset we solved.

3.3 Avoiding under-fitting

Numerically, the formulation would allow us to continue eliminating parameters. However, contrary to a neural net or a scoring function where parameters do not have a clear meaning, here there is no intuition to equate, say, the magnitude of the Gln = A H-bonds of −0.90 kcal/mol and the NH2 + 0.95 kcal/mol desolvation penalty. On the other hand, further equating parameters of the same type (either H-bonds or desolvation) are detrimental to the mapping of the binding data (Figs 4 and 5).

Fig. 5.

Predictions of ΔΔGbind in independent validation datasets of fingers II and III mutants of EGR. R2 correlation coefficient of predicted and experimental changes in binding affinities for MIP solutions with different number of parameters. Open spheres and open squares show correlation coefficients for finger II and III mutants of EGR, respectively. Solid sphere and solid square show the original predicted correlation coefficient (Temiz and Camacho, 2009). The two symbols for six parameters correspond to whether a H-bond or a desolvation penalty is further eliminated as a free parameter.

It is important to point out that the assessment of whether the representation under-fit the data depends on the expected accuracy. It is quite possible that, as more high-quality binding data is available, mapping some of the small differences that were inconsequential for the present analysis might subsequently turn out to be statistically significant.

3.4 Submodel reassessment and validation based on MIP-optimal parameters

We test the different set of optimized parameters against two independent sets of finger II and III mutants that were not part of the MIP optimization process. Predictions of the complex structures and binding affinities on these validation datasets resulted in correlations of R2 = 0.97 (Fig. 5 and Supplementary Figure S1). Although these correlations are good, they are not as good as EGR finger I. One reason is that homology submodels for fingers II and III are naturally less reliable than those of finger I, since most of our templates are from finger I co-crystals.

Since placing water molecules in a protein interface is still a challenging problem (Bonvin et al., 1998; Dennis et al., 2000), it is not surprising that some of the largest deviations between predicted and experimental binding affinities were in submodels where water molecules play a critical role modulating the interactions (Fig. 6). This problem is compounded by context-dependent effects from adjacent ZFs (Liu and Stormo, 2008; Pabo et al., 2001; Segal et al., 1999). This is the case of the binding modes that have a Gln or Asp at pos. −1 that show different solvation patterns in the finger I crystals and in the validation dataset for finger II models. Crystal structures (Elrod-Erickson et al., 1998) show side chains at pos. −1 are partially solvated, while the binding interfaces at pos. +3 and +6 are desolvated, relative to WT (see shaded and open triangles). Similar submodels for finger II (Temiz and Camacho, 2009) reflected the excess of water molecules at pos. +3 and +6 observed in the WT finger II crystal structure, and the extra protection of side chains at pos. −1 relative to WT finger I that has solvent at its 5′ end.

Fig. 6.

Re-examining context-dependent solvation effects in finger II mutants of EGR. (A) Changes in solvation patterns for finger II mutants. First column shows the finger I crystal complex of Q (dark boxes) and D (light boxes) binding modes (Elrod-Erickson et al., 1998). Second column shows the original solvation patterns (Temiz and Camacho, 2009) and third column shows the updated solvation patterns (this study). (B) Cartoon of the updated submodel QGDR/GCA complex. DNA is shown in dark sticks. Asp+3 is shown in light sticks. Crystal waters are shown as spheres. Dashed lines indicate H-bond interactions. Gln-1 and Arg+6, shown in light sticks, protect Asp+3 from solvation. Light colored numbers are predicted affinities using optimized code (in parenthesis are affinities based on unoptimized code, and black numbers are predicted and experimental relative affinities.

Based on the increased accuracy of the MIP formulation, we found that predictions for at least two of these original submodels became worse. Close inspection of these models led to a reassessment of the solvation patterns, leading us to conclude that bonds at pos. +3 might not be as solvated as expected. For instance, Figure 6B shows a new submodel of QGDR/GCA using the crystal waters visible in WT, where the Asp+3-C H-bond is >3 Å away from the closest water molecule. Moreover, contrary to our earlier submodels, we now estimate that the extra waters modeled in complexes involving purines, as in QSNR/GAA, are blocked by the Ser+2-C′ H−bond (but not necessarily by the Ser+2-A′ in finger III). Thus, the Gln−1 bonds are now desolvated as in QGDR/GCA. Something similar occurs with Asp−1-C in the D binding mode. As shown in Figure 6A, these updated solvation patterns in the new submodels are not only more consistent among each other but also have greatly improved some of the worst predictions in (Temiz and Camacho, 2009). Using Equation 2, the new relative affinities (in red in updated submodels) lead to ΔΔ Gs of −0.65, −1.82 and −0.58 for the three finger II mutants QGDR/GCA, QSNR/GAA and DGNR/GAC compared with the experimental values of −0.95, −1.77, −0.71, respectively. Overall, the correlation coefficient R2 of finger II mutants improved from 0.957 to 0.971.

4 CONCLUSION

Our understanding of how transcription factors work cooperatively to regulate gene expression is still in its infancy. A major challenge for computational biology in the coming years is to develop tools that help us understand the molecular basis of how transcription factors identify and bind their multiple targets. The most important missing pieces of this puzzle are the lack of a quantitative understanding of protein–DNA interactions and experimental techniques that can account for DNA specificity.

Here, we demonstrate that the problem of decoding protein–DNA interactions using a pre-selected set of feasible homology submodels is particularly suited to be tackled via a method involving mixed integer programming. Specifically, the MIP solution of the interaction code for C2H2 ZF transcription factors resulted in an almost exact mapping of the change in binding free energies of a set of 35 mutants of EGR finger I, as well as that of two validation sets of mutants of fingers II and III of EGR (Fig. 5 and Supplementary Figure S1). It is also clear that using MIP can further expedite the discovery and validation of relevant parameters by providing an efficient tool to optimize the increasing complexity of the objective function that minimizes the difference between the predicted lowest binding free energy submodel of each complex and experimental data. Three key advantages of our mathematical formulation are its inherent flexibility, extensibility and scalability. Thus, as we receive or gather more complete information in the form of new crystals or binding data, results can be automatically updated and re-optimized, eliminating the need for manual intervention of every ZF and ensuring an optimal prediction power.

The removal of constraints and variables from our representation is just as important as their addition. As shown here, a given solution can suggest the convergence of physical parameters, which can reduce the number of parameters by simply enforcing a new relationship. Doing so lowers the available degrees of freedom in our representation, resulting in a more compact interaction code less prone to over-fitting. Here, the convergence of the interactions as the number of free parameters were reduced strongly support the universality of the selected physical parameters, which include three H-bonds, three desolvation penalties and a water factor. Other interactions can now be further built based on other sets of mutants (e.g. from finger III) to obtain a more complete representation of possible interactions. It is important to stress, however, that the combination of high-quality crystal structures and binding data of finger I mutants of EGR is not available for other ZFs.

Our unique methodology also eliminates most false positives by scoring the lowest binding free energy submodel in each complex, significantly limiting the effect of missing the ‘true’ complex structure by simply selecting a related feasible submodel belonging to the same funnel (see Figs 3 and 6). Moreover, close inspection of outliers can be used as a self consistent proof checking of initial submodels. Such a feedback was used in Figure 6 to suggest new submodels for finger II mutants, and, in all likelihood, should prove useful elucidating other context-dependent effects from adjacent ZFs or DNA, which are quite subtle to generalize.

In summary, the combination of biochemical data, structural information and the described MIP mathematical framework, provides an easily scalable and efficient tool for the (i) automatic selection of exactly one submodel for each complex; (ii) each selected submodel has the lowest energy for each complex; and (iii) parameters as well as selected submodels provide the closest fit to the experimental data for the considered objective function with minimum over-fitting.

Funding: National Science Foundation (MCB-0744077 to C.J.C., CMMI0825993 to O.A.P.); US Air Force Office of Scientific Research (FA95500810268 to O.P.); US Department of Education Graduate Assistance in Areas of National Need Fellowship Program (P200A060149 to A.T.).

Conflict of Interest: none declared.

Supplementary Material

REFERENCES

- Bae KH, et al. Human zinc fingers as building blocks in the construction of artificial transcription factors. Nat. Biotechnol. 2003;21:275–280. doi: 10.1038/nbt796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonvin AM, et al. Water molecules in DNA recognition II: a molecular dynamics view of the structure and hydration of the trp operator. J. Mol. Biol. 1998;282:859–873. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.2034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bueno M, Camacho CJ. Acidic groups docked to well defined wetted pockets at the core of the binding interface: a tale of scoring and missing protein interactions in CAPRI. Proteins. 2007a;69:786–792. doi: 10.1002/prot.21722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bueno M, et al. SIMPLE estimate of the free energy change due to aliphatic mutations: superior predictions based on first principles. Proteins. 2007b;68:850–862. doi: 10.1002/prot.21453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camacho CJ, et al. Scoring a diverse set of high-quality docked conformations: a metascore based on electrostatic and desolvation interactions. Proteins. 2006;63:868–877. doi: 10.1002/prot.20932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camenisch TD, et al. Critical parameters for genome editing using zinc finger nucleases. Mini. Rev. Med. Chem. 2008;8:669–676. doi: 10.2174/138955708784567458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornell WD, et al. A 2Nd generation force-field for the simulation of proteins, nucleic-acids, and organic-molecules. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1995;117:5179–5197. [Google Scholar]

- Dennis S, et al. Continuum electrostatic analysis of preferred solvation sites around proteins in solution. Proteins. 2000;38:176–188. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dundas J, et al. Topology independent protein structural alignment. BMC Bioinformatics. 2007;8:388. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-8-388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elrod-Erickson M, et al. High-resolution structures of variant Zif268-DNA complexes: implications for understanding zinc finger-DNA recognition. Structure. 1998;6:451–464. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(98)00047-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elrod-Erickson M, et al. Zif268 protein-DNA complex refined at 1.6 A: a model system for understanding zinc finger-DNA interactions. Structure. 1996;4:1171–1180. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(96)00125-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ernst JA, et al. Demonstration of positionally disordered water within a protein hydrophobic cavity by Nmr. Science. 1995;267:1813–1817. doi: 10.1126/science.7892604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Floudas C, Pardalos P. Optimization in Computational Chemistry and Molecular Biology: Local and Global Approaches. Dordrecht, Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Pub.; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Floudas C, Pardalos P. Encyclopedia of Optimization. New York: Springer; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Fung H, et al. Computational comparison studies of quadratic assignment like formulations for the in silico sequence selection problem in de novo protein design. J. Comb. Optim. 2005;10:41–60. [Google Scholar]

- Glover F, Kochenberger G. Handbook of Metaheuristics. Dordrecht, Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- ILOG. CPLEX 11.0 User's Manual. ILOG CPLEX Division. Incline Village, NV: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Kang JS. Correlation between functional and binding activities of designer zinc-finger proteins. Biochem. J. 2007;403:177–182. doi: 10.1042/BJ20061644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laity JH, et al. Zinc finger proteins: new insights into structural and functional diversity. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2001;11:39–46. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(00)00167-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J, Stormo GD. Quantitative analysis of EGR proteins binding to DNA: assessing additivity in both the binding site and the protein. BMC Bioinformatics. 2005;6:176. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-6-176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J, Stormo GD. Context-dependent DNA recognition code for C2H2 zinc-finger transcription factors. Bioinformatics. 2008;24:1850–1857. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btn331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendez R, et al. Assessment of CAPRI predictions in rounds 3-5 shows progress in docking procedures. Proteins. 2005;60:150–169. doi: 10.1002/prot.20551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morozov AV, et al. Protein-DNA binding specificity predictions with structural models. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:5781–5798. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nemhauser G, Wolsey L. Integer and Combinatorial Optimization. New York: Wiley; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Pabo CO, et al. Design and selection of novel Cys2His2 zinc finger proteins. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2001;70:313–340. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.70.1.313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pardalos P, Resende M. Handbook of Applied Optimization. New York: Oxford University Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Pavletich NP, Pabo CO. Zinc finger-DNA recognition: crystal structure of a Zif268-DNA complex at 2.1 A. Science. 1991;252:809–817. doi: 10.1126/science.2028256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pavletich NP, Pabo CO. Crystal structure of a five-finger GLI-DNA complex: new perspectives on zinc fingers. Science. 1993;261:1701–1707. doi: 10.1126/science.8378770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prasad JC, et al. Consensus alignment for reliable framework prediction in homology modeling. Bioinformatics. 2003;19:1682–1691. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prokopyev O, et al. On multiple-ratio hyperbolic 0-1 programming problems. Pac. J. Optim. 2005;1/2:327–345. [Google Scholar]

- Segal DJ, et al. Structure of Aart, a designed six-finger zinc finger peptide, bound to DNA. J. Mol. Biol. 2006;363:405–421. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segal DJ, et al. Toward controlling gene expression at will: selection and design of zinc finger domains recognizing each of the 5’-GNN-3’ DNA target sequences. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1999;96:2758–2763. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.6.2758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siggers TW, et al. Structural alignment of protein–DNA interfaces: insights into the determinants of binding specificity. J. Mol. Biol. 2005;345:1027–1045. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Temiz NA, Camacho CJ. Experimentally based contact energies decode interactions responsible for protein-DNA affinity and the role of molecular waters at the binding interface. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:4076–4088. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vazirani V. Approximation Algorithms. Berlin: Springer; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Wolfe SA, et al. DNA recognition by Cys2His2 zinc finger proteins. Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biomol. Struct. 2000;29:183–212. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.29.1.183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu T.-H. A note on a global approach for general 0–1 fractional programming. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 1997;101:220–223. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.