A 1.9 Å resolution crystal structure of the isolated kinase domain from the α2 subunit of human AMPK, the first from a multicellular organism, is presented.

Keywords: AMP-activated kinases, kinases, DFG-out conformation

Abstract

The AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) is a highly conserved trimeric protein complex that is responsible for energy homeostasis in eukaryotic cells. Here, a 1.9 Å resolution crystal structure of the isolated kinase domain from the α2 subunit of human AMPK, the first from a multicellular organism, is presented. This human form adopts a catalytically inactive state with distorted ATP-binding and substrate-binding sites. The ATP site is affected by changes in the base of the activation loop, which has moved into an inhibited DFG-out conformation. The substrate-binding site is disturbed by changes within the AMPKα2 catalytic loop that further distort the enzyme from a catalytically active form. Similar structural rearrangements have been observed in a yeast AMPK homologue in response to the binding of its auto-inhibitory domain; restructuring of the kinase catalytic loop is therefore a conserved feature of the AMPK protein family and is likely to represent an inhibitory mechanism that is utilized during function.

1. Introduction

The AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) is a conserved eukaryotic protein complex that regulates cell metabolism in response to a drop in the supply of the immediate energy-storage molecule ATP (Hardie, 2007b ▶). Once activated, AMPK raises ATP levels by promoting the breakdown of long-term energy-storage supplies such as fatty acids (Hardie & Pan, 2002 ▶); it phosphorylates multiple key proteins, bringing about an inhibition of anabolic ATP-consuming pathways and promoting catabolic ones. As such, the role of AMPK has often been described as a cell’s ‘low-fuel warning system’ (Hardie & Carling, 1997 ▶), a warning system that seeks to restore balance but also influences cell fate by coordinating energy-intensive processes such as proliferation with carbon-source availability (Jones et al., 2005 ▶).

In multicellular organisms, the AMPK complex undertakes roles additional to its action as a cellular fuel gauge; the complex integrates signals from extracellular sources such as hormones and cytokines as well as responding to intracellular energy levels (Hardie & Carling, 1997 ▶). When such extracellular signals are integrated by AMPK, they are able to influence whole-body energy expenditure and food intake (Hardie et al., 2006 ▶). This whole-body response is of pharmacological interest owing to its connection with metabolic disorders such as diabetes and obesity (Hardie, 2007a ▶; Towler & Hardie, 2007 ▶). For example, the antidiabetic drugs metformin and rosiglitazone exert their pharmacological effect in part through AMPK (Musi, 2006 ▶; Fujii et al., 2006 ▶); moreover, the promotion of glucose transport and cellular uptake by aminoimidazole carboxamide ribonucleotide (AICAR) arises through its action as an AMPK agonist (Fujii et al., 2006 ▶).

The molecular mechanics by which AMPK exerts its effects are beginning to be understood. The AMPK complex is heterotrimeric, consisting of a single copy each of the catalytic α subunit and the regulatory β and γ subunits. Cellular energy availability is sensed through the [AMP]/[ATP] ratio, with both molecules binding competitively to sites within the γ subunit; AMP binding has a stimulating effect on kinase activity, whereas ATP binding is inhibitory. The complex is thus inactive when adequate energy is available. Regulation of activity occurs predominantly through conformational rearrangements that lead to changes in the phospho-status of the kinase domain; however, internal changes within the heterotrimer can also have a direct affect on catalytic turnover.

The three AMPK subunits have multiple functional domains (Fig. 1 ▶ a) and come in several human isoforms (two α, two β and three γ). The energy-sensing γ subunit forms a stable core of the complex about which the other components organize. This subunit encodes four cystathionine β-synthase (CBS) motifs that fold into a disk shape constructing two Bateman domains (Kemp, 2004 ▶; Scott et al., 2004 ▶). From structures of the regulatory portion of the mammalian AMPK heterotrimer (Fig. 1 ▶ a; Xiao et al., 2007 ▶), it is clear that two exchangeable adenyl-binding sites within the Bateman domains serve the purpose of converting fluctuations in the [AMP]/[ATP] levels to changes in catalytic activity. However, the absence of the kinase domain in such structures means that the molecular mechanism that transmits the energy-sensing signal to the catalytic subunit is only partially understood.

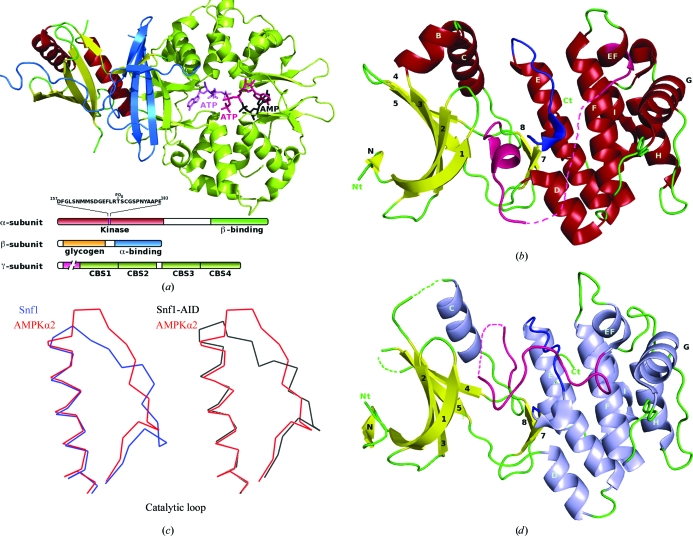

Figure 1.

(a) A guide showing the extent of the different domains within the three human AMPK subunits. The γ-subunit isoforms all share a common ATP/AMP-sensing core but have different N-terminal extents. Above is a cartoon representation of the mammalian AMPK regulatory heterotrimer of Xiao et al. (2007 ▶); the γ subunit is in green with the bound ATP/AMP molecules labelled, the β subunit is in blue and the C-terminal section of the α subunit is portrayed with helices coloured red, β-strands yellow and loop regions green. (b) Cartoon representation of the AMPKα2 kinase domain structure; secondary-structural elements are labelled in black or white and the N- and C-termini in light green. The ‘activation loop’ is highlighted in pink and the ‘catalytic loop’ in blue. Dotted lines represent regions of the protein not observed in electron density. (c) Cα backbone alignments highlighting changes in the catalytic loop during the HRD flip; comparisons are made between AMPKα2 (in red) and the Snf1 structure (in blue) of Nayak et al. (2006 ▶) or the inhibited Snf1–AID structure (in grey) of Chen et al. (2009 ▶). (d) For the sake of comparison with (b), a similar cartoon representation of the Snf1 structure of Nayak et al. (2006 ▶) is shown. Colouring and highlights are maintained, except that the Snf1 helices are coloured slate for distinction.

The catalytic Ser/Thr protein kinase domain of AMPK is encoded within the 280 N-terminal residues of the α subunit, a region over which the human α1 and α2 isoforms are almost identical (94% sequence identity). The enzymatic activity of this domain requires that a residue within the activation loop be phosphorylated on a conserved threonine by an upstream kinase (Thr172 in AMPKα2). Under conditions of adequate energy supply, when ATP is bound within the energy-sensing γ subunit, the regulatory domains prevent upstream kinases from recognizing Thr172 as a substrate and promote its processing by phosphatases, mechanisms which are reversed upon AMP binding (Hardie, 2007b ▶). Immediately following the kinase domain is a stretch of ∼70 residues that form an auto-inhibitory domain (AID). When the phosphorylated but truncated AMPKα1 kinase domain is expressed it possesses moderate activity that is insensitive to AMP/ATP concentrations. However, this constitutive activity is dramatically reduced in longer constructs containing the AID (Crute et al., 1998 ▶). The AID is therefore thought to connect to the energy-sensing apparatus of the full-length complex, being part of an inhibitory mechanism that is relieved upon AMP binding to the γ subunit (Chen et al., 2009 ▶). The ∼550-residue α subunits also have a small C-terminal domain involved in complex formation that is necessary and sufficient for the association of the α subunit with the β subunit and through it the γ subunit (Iseli et al., 2005 ▶). The details of this arrangement have been elucidated in the structure described by Xiao et al. (2007 ▶) (Fig. 1 ▶ a). However, it remains to be understood how the kinase domain or the remainder of the α subunit are juxtapositioned within this regulatory framework and through which residues AMP/ATP binding is communicated. We were thus interested in obtaining further structural information about the catalytic subunit of a mammalian AMPK.

In this paper, we present the first crystal structure of a human AMPK kinase domain: that of the α2 isoform. The structure of the isolated kinase domain is noteworthy in that it has undergone both a DFG flip within its activation loop and a concomitant restructuring of its catalytic loop. This inactive form of the enzyme represents a specialized regulatory mechanism within AMPK that is conserved in the yeast homologue (Chen et al., 2009 ▶), where such distortions are seen to occur in a longer construct containing both the kinase domain and a bound AID. We propose that activation-loop and catalytic loop rearrangements may be connected to ATP/AMP sensing in mammalian AMPKs and that such structural changes are linked to intersubunit- and intrasubunit-mediated interactions involving the auto-inhibitory domain.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Cloning and expression

cDNA corresponding to the AMPKα2 kinase domain (AMPKα2-KD; residues 6–279) was cloned into the pET-28 expression vector using the InFusion cloning system (Clontech Inc.). The resulting vector was transformed into BL21 (DE3) Escherichia coli cells, which were grown in 4 l Terrific Broth at 310 K to OD600 values of between 4 and 6. The temperature was then decreased to 287 K and protein expression was allowed to occur overnight after induction with 1 mM IPTG.

Cells were harvested, resuspended in buffer A (50 mM Tris–HCl, 500 mM NaCl, 5 mM imidazole, 0.5 mM TCEP) and then lysed by two passes through a microfluidizer (Microfluidics). Cell debris was pelleted by centrifugation and the resulting supernatant was applied onto nickel–NTA affinity resin (Qiagen) which was extensively washed with buffer A. The protein was eluted from the resin using three washes with buffer A containing an increasing concentration of imidazole (40, 80 and 400 mM). The protein’s hexahistidine tag was then removed via a thrombin-cleavage step for 16 h at 277 K before applying the product onto a HiLoad S200 16/60 gel-filtration column (GE Healthcare). The AMPKα2 kinase domain eluted from this column in the void volume but was nonetheless able to be concentrated to 5–8 mg ml−1 for crystallographic applications.

2.2. Crystal growth and data collection

Crystals of AMPKα2-KD were grown in a sitting-drop setup using protein at approximately 7 mg ml−1. Prior to being set into trays, the protein was incubated on ice for 30 min with 5 mM 5′-adenylyl-β,γ-imidodiphosphate (AMPPnP) and 5 mM MgCl2. In the crystal trays, 400 nl of the protein/AMPPnP/MgCl2 mixture was then set into drops with 400 nl reservoir solution and sealed; crystals were observed to grow over a two-week period. The reservoir that yielded the crystal from which diffraction data were obtained consisted of 18.6%(w/v) PEG 4000, 0.1 M (NH4)2SO4, 0.1 M Tris–HCl pH 8.5 and 15%(v/v) 2-propanol.

The crystal was harvested and transferred into a drop containing Paratone, the surrounding aqueous surface layer was removed and the crystal was frozen in liquid nitrogen. Diffraction data were collected at 100 K on a Rigaku FR-E rotating-anode source using a Cu anode. The crystal diffracted to 1.85 Å resolution and belonged to space group P21, with unit-cell parameters a = 39.4, b = 67.4, c = 50.5 Å, β = 91.3° (see Table 1 ▶ for data-collection and refinement statistics).

Table 1. Data-collection and refinement statistics for AMPKα2.

Values in parentheses are for the highest resolution shell.

| Data-collection statistics | |

| No. of crystals | 1 |

| Space group | P21 |

| Unit-cell parameters (Å, °) | a = 39.4, b = 67.4, c = 50.5, β = 91.3 |

| Resolution limits (Å) | 19.7–1.85 (1.90–1.85) |

| Completeness (%) | 98.8 (86.3) |

| No. of reflections | 21209 (1344) |

| Multiplicity | 3.5 (2.3) |

| Rmerge | 0.047 (0.504) |

| 〈I/σ(I)〉 | 26.9 (1.6) |

| Wilson B factor (Å2) | 28.5 |

| Model refinement statistics | |

| R factor† | 0.188 |

| Rfree† | 0.227 |

| No. of protein atoms | 2068 |

| No. of waters | 164 |

| Ramachandran plot‡ | |

| Most favoured (%) | 98.4 |

| Generously allowed (%) | 1.6 |

| Disallowed (%) | 0.0 |

| R.m.s.d. bonds‡ (Å) | 0.015 |

| R.m.s.d. angles‡ (°) | 1.50 |

2.3. Data processing, model building and refinement

The diffraction data collected on a home Rigaku FR-E source equipped with an R-AXIS IV++ detector were integrated and scaled using HKL-2000 (Minor et al., 2006 ▶). Phases were obtained by molecular replacement with Phaser (McCoy et al., 2007 ▶) using a single protein subunit of the yeast Snf1 kinase domain (PDB code 2fh9) as a search probe (Nayak et al., 2006 ▶). Initial rounds of automatic model building were performed with ARP/wARP (Morris et al., 2003 ▶), after which rounds of manual building and restrained maximum-likelihood refinement were performed using the graphics program O (Jones et al., 1991 ▶) and REFMAC5.2 (Murshudov et al., 1997 ▶). TLS (Painter & Merritt, 2006 ▶) and restrained refinement was used in later stages, with initial TLS parameters obtained from the TLSMD server. The final R factor was 0.188 and R free was 0.227.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. The kinase fold and comparison with Snf1

Crystals of the human AMPKα2 kinase domain (residues 6–279) were grown and a data set was collected to 1.85 Å resolution. Phases were obtained by molecular replacement, yielding electron density that allowed the visualization of residues 10–166 and 180–278. The missing residues correspond to the C-terminal half of the activation loop of the kinase; these are likely to be disordered in our structure as mass spectrometry did not indicate any evidence of sample degradation prior to crystal growth.

Globally, AMPKα2 adopts a typical bilobed kinase fold (see Fig. 1 ▶ b) similar to that observed for the homologous yeast protein sugar nonfermenting 1 (Snf1; Nayak et al., 2006 ▶; Rudolph et al., 2005 ▶; Chen et al., 2009 ▶), which has 61% sequence identity in this domain. Snf1 is part of a heterotrimeric complex with a similar domain structure to AMPK and many comparisons have been made between the two proteins; however, some care needs to be taken owing to the possibility of orthologue-specific differences. The N-terminal ATP-binding lobe of AMPK consists of two α-helices (αB and αC) and a six-stranded mixed β-sheet (β1–5 and βN) with a high degree of twist. The C-terminal substrate-binding lobe contains six large α-helices (αD, αE, αF, αG, αH and αI), one short αEF helix following the activation segment and two β-strands (β7 and β8). Strands β6 and β9 are not present in this form of AMPKα2 owing to the disordered activation segment. Protein kinases are typically capable of a degree of rigid-body motion about a hinge region between their two lobes; as such, they are often trapped in either an open or closed state during crystallization. In yeast Snf1 (Nayak et al., 2006 ▶; Rudolph et al., 2005 ▶; Chen et al., 2009 ▶) open lobe conformations are observed in three of the four known kinase-domain structures; the sole closed-lobe Snf1 form is an inhibited AID-bound Schizosaccharomyces pombe structure (Chen et al., 2009 ▶). Interestingly, the lobe orientation of the AMPKα2 kinase domain aligns most closely with this AID-bound form of Snf1.

3.2. The activation loop and a distorted ATP-binding site

One of the most notable features of the AMPKα2 structure is the distorted nature of its activation loop. In protein kinases this is a long flexible segment connecting β8 to αEF; it has major effects on catalytic activity as it mediates interactions with the substrate and consequently it is often an important site of regulation. The activation loop is delineated by two sequence motifs that are conserved within the protein-kinase superfamily: an invariant DFG sequence following β8 on the N-terminal side (residues 157DFG159) and a semi-conserved 181APE183 sequence within helix αEF on the C-terminal side. In AMPKα2 the DFG motif and the seven residues immediately C-terminal to it are ordered but adopt a nonproductive conformation (see Fig. 1 ▶ b). The backbone of the residues within the invariant DFG motif has flipped around and as a result the ATP site is adversely affected and is incompatible with binding. This may explain why despite the presence of MgCl2 and a nondegradable ATP analogue in our crystallization experiment neither were observed to be bound to the active site of the kinase.

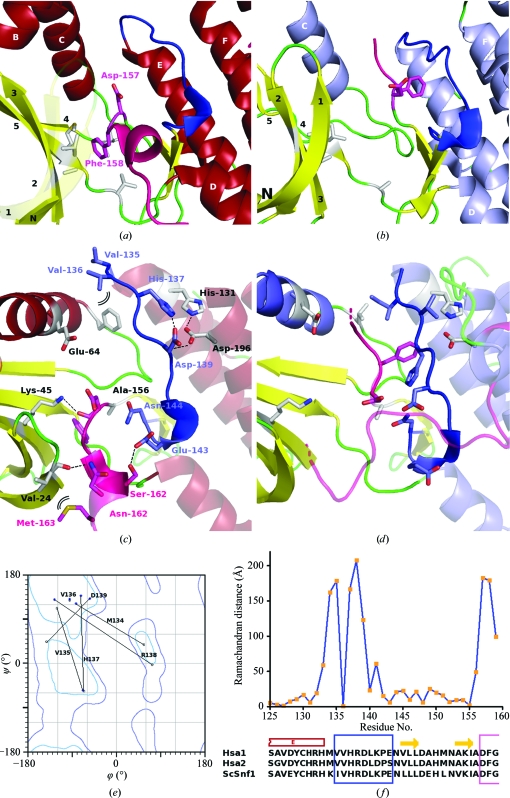

In a productive kinase ATP-binding mode, the aspartate residue within the DFG motif chelates the magnesium ions required for coordination of the ATP phosphate groups and the phenylalanine residue interacts with the αC helix, stabilizing a catalytically necessary ion pair (Glu64 and Lys45 in AMPKα2; Huse & Kuriyan, 2002 ▶). In contrast, our inactive form of AMPKα2 has undergone large-scale backbone rearrangements that produce a significantly different conformation (as seen by comparing Figs. 2 ▶ a and 2 ▶ b). The backbone torsion angle ϕ of Asp157 has rotated by 180° with respect to the conformation of its counterpart in the active Snf1 structures. This has the effect of distorting the ATP-binding site in multiple ways: the side chain of the conserved aspartate is moved away from a position in which it could productively coordinate Mg2+ ions and the aromatic ring of Phe158 inserts deeply into the hydrophobic adenyl-binding pocket, blocking ATP binding. In addition, the backbone structure immediately following the DFG motif now blocks the entrance to the ATP-binding site. This portion of the activation loop forms a single helical turn that packs against the β1 strand and catalytic loop; the remainder of the loop remains disordered.

Figure 2.

(a) A cartoon representation of the blocked AMPKα2 ATP-binding site and the structure of its activation loop (pink) and substrate-binding loop (blue). All three regions appear to be distorted from standard catalytically active forms. The side chains of the conserved aspartate and phenylalanine within the DFG activation-loop sequence are shown and labelled. β1 and β2 are shown transparently to help visualize the ATP site itself. (b) For comparison, a similar view of the more standard activation-loop structure of Snf1 is shown with its open ATP-binding site available for binding (Nayak et al., 2006 ▶). (c) Detailed view of the interactions that stabilize the structure. (d) The analogous residues in yeast Snf1. (e) Ramachandran plot comparing the torsion angles of residues within the distorted AMPKα2 catalytic loop (blue squares) with their counterparts within the more standard conformations observed in the Snf1 structure of Nayak and coworkers (grey squares). (f) A plot of the Ramachandran distance (in Å) between each of the AMPKα2 and Snf1 counterpart residues highlighting the hinge regions of the change.

Of the ∼130 different protein kinases for which structures are known, distorted ATP-binding sites similar to that of AMPKα2 have only been observed in a handful of structures, with the archetypal example being the insulin receptor tyrosine kinase (Hubbard et al., 1994 ▶). Owing to the altered nature of the invariant DFG motif, this inactivation mechanism has been referred to as the DFG-out conformation (Levinson et al., 2006 ▶). This structure is thought to be a transiently populatable state that is accessible to the kinase folds of a number of unrelated proteins. Convergent evolutionary processes appear to have co-opted the DFG-out state in different regulatory systems that control enzymatic function through dynamic interactions that stabilize or destabilize this inactive form of a kinase fold, a stabilization that is typically influenced through additional domains or post-translational modifications (Levinson et al., 2006 ▶). A new class of inhibitors, those designated as having a type II binding mode, exploit kinases that transiently access a DFG-out conformation by artificially trapping them in this state. It is interesting that we have crystallized the kinase domain in this way as AMPK has been reported to exist in a default off state in the absence of AMP. It is possible that the AMPK kinase domain may have an inherently long dwell time in this inactive state and requires external factors to promote its correct folding.

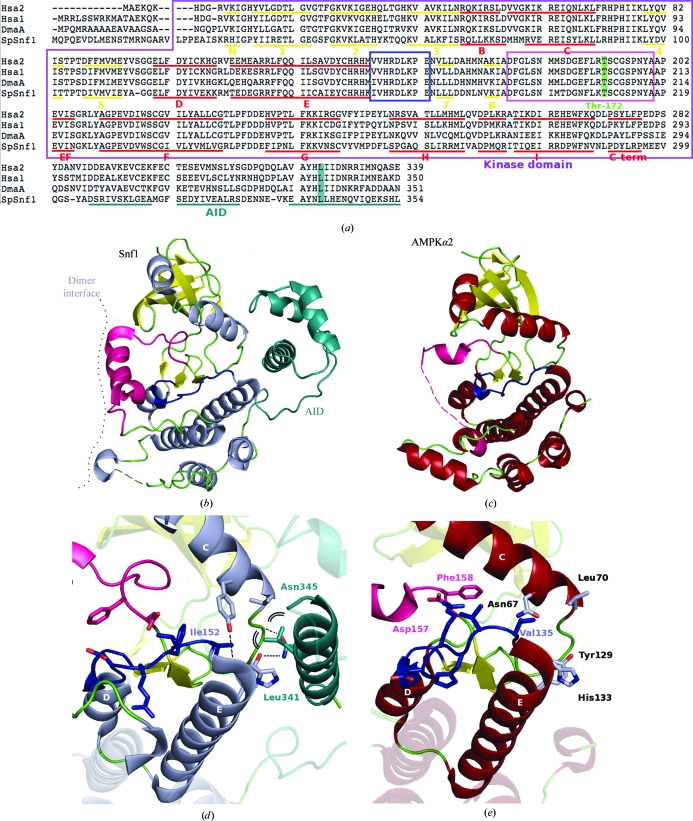

Three of the four known Snf1 structures only contain the kinase domain and have productively folded activation loops. However, a fourth S. pombe Snf1 structure contains both the kinase domain and its C-terminal auto-inhibitory region (Fig. 3 ▶ b; Chen et al., 2009 ▶). This AID-bound Snf1 structure also displays a DFG-out-type conformation (see Fig. 3 ▶ d), albeit one that is subtly different to that observed in the isolated AMPKα2-KD. This is in part a consequence of the remainder of the activation loop being structured and involved in an extensive dimer interface (Chen et al., 2009 ▶), whereas the mammalian AMPKs are monomeric (Xiao et al., 2007 ▶) and display no abnormally extensive crystal-packing contacts. In the Snf1 AID structure the activation loop forms a short turn within the ATP-binding site such that the aromatic ring of the DFG phenylalanine is removed from its stabilizing position near αC and instead moves to pack against a large helix formed by the remainder of the activation loop. This unusual ordered activation-loop helix is a major part of the interface between the two Snf1 kinase domains (Chen et al., 2009 ▶); hence, its physiological significance is currently unclear.

Figure 3.

(a) Kinase-domain sequence alignment of Hsa2 (the human AMPK α2 subunit), Hsa1 (the human α1 subunit), DmaA (the Drosophila melanogaster α subunit, A isoform) and ScSnf1 (Saccharomyces cerevisiae Snf1 protein). Secondary-structure elements are underlined, the activation segment is shown in a pink box, the catalytic loop is shown in a blue box and the Snf1 AID helices are underlined in teal. (b) Cartoon representation of the S. pombe kinase domain with bound AID. (c) A view of the equivalent orientation in AMPKα2. (d) Residues involved in binding the AID are shown and highlighted and their equivalents within AMPKα2 are shown in (e).

There are a number of protein kinase structures with DFG-out configurations, including the tyrosine kinases Abl, the insulin receptor, c-Kit, Csk, VEGFR2, Flt3 and Pyk2 as well as the Ser/Thr kinases Lck, Raf and p38 (Levinson et al., 2006 ▶; Griffith et al., 2004 ▶; Han et al., 2009 ▶; Harmange et al., 2008 ▶; Hubbard et al., 1994 ▶; Jacobs et al., 2008 ▶; Mol et al., 2004 ▶). Along with AMPKα2 and Snf1, the insulin receptor, c-Kit and Flt3 reflect native inactivation mechanisms, while the other DFG-out structures are trapped type II drug-bound forms. Additionally, a DFG to DIG mutation has been used as a means of trapping the short-lived state of p38 in the absence of inhibitors (Bukhtiyarova et al., 2007 ▶). The inactive conformations of Snf1, c-Kit and Flt3 are partially imposed by interactions with extra domains; these extraneous segments serve to lock the two kinase lobes together through contacts with helix αC or to stabilize new activation-loop structures promoting the DFG flip. In contrast, the fact that only the minimal kinase domains of AMPKα2 and the insulin receptor alone crystallize in a DFG-out form suggest that intrinsic features of the domain are able to stabilize the inactive state. The activation loop of both structures exits the interlobe interface near the entrance of the expected ATP site and in doing so makes significant contacts with residues from both kinase lobes, promoting lobe closure (see Fig. 2 ▶ c).

3.3. Changes in the catalytic loop

AMPKα2 and Snf1 are unique amongst inhibited kinases in that the remodelling of the DFG motif is concomitant with rearrangements within the catalytic loop (see the blue segments in Figs. 2 ▶ a–2d, 3 ▶ b and 3 ▶ c). In AMPKα2 these changes stabilize the altered structure by allowing residues that have lost hydrogen-bonding partners as a result of the DFG flip to form new ones elsewhere in the protein. The largest changes occur within HRD-triad residues of the catalytic loop (see Figs. 2c–2f) that are contained within the conserved protein kinase sequence 137HRDLKxxN144. The residues within this motif have been evolutionarily maintained for structural reasons (Leu140 and His137) or for their roles in ATP binding (Asn144 is a magnesium ion-chelating residue) or catalysis (Asp139).

Significant changes in the backbone position and local environment occur for many of the catalytic loop residues (Figs. 2 ▶ e and 2 ▶ f). This includes the conserved-triad histidine (His137), the two preceding hydrophobic residues (Val135 and Val136) and the invariant catalytic base aspartate (Asp139). In a functional kinase-activation and catalytic loop conformation, the side chain of His137 would be expected to hydrogen bond to the backbone of the DFG motif’s aspartate, the preceding two hydrophobic residues would form strand β6, part of a small dynamic β-sheet that includes a strand from within the phosphorylated activation loop, and the side chain of Asp139 would be positioned near a magnesium-chelating asparagine awaiting phosphotransfer. Each of these interactions are broken in the new DFG-out conformation as the activation loop moves in space to pack against the entrance to the ATP site. To compensate for lost interactions, His137 and Asp139 flip towards the C-terminal lobe to take part in a hydrogen-bond network with His131 from αE, Asp196 from αF and Tyr190 from a nearby loop (see Fig. 2 ▶ c). The formation of this network requires the displacement of Val136 from its standard position near αE to a hydrophobic pocket at the base of helix αC, a pocket originally filled by Val135, which is in turn expelled out of the active site and into a relatively solvent-exposed environment. Each of these changes within the HRD triad serves to move important residues away from their standard catalytically active configuration, preventing substrate binding.

The expulsion of Val135 towards solvent during the structural change is a potential connection point between the external surface of the kinase domain and its internal catalytic machinery. It is particularly intriguing in light of the recent S. pombe Snf1 kinase domain–AID structure (Chen et al., 2009 ▶). The Snf1 AID consists of a bundle of three helices, the last of which interacts directly with the αC and αE helices of the kinase domain and is presumed to modulate interlobe motions (see Fig. 3 ▶ b). Three Snf1 structures of the isolated kinase domain are known and all have productively folded DFG motifs and catalytic loops; AID binding therefore seems to induce a DFG-out flip in the Snf1 activation loop and also a refolding of the catalytic loop like that observed in the isolated human AMPKα2 kinase domain. One caveat that must be made when comparing Snf1 with AMPK is that their respective auto-inhibitory domains display significant sequence divergence. While structure-guided sequence alignments (Fig. 3 ▶ a) and biochemical evidence (Chen et al., 2009 ▶) do suggest a common mechanism, this assumption has not yet been concretely proven and the AMPK AID could still be significantly different.

The refolding of the Snf1 catalytic loop is stabilized by direct and indirect interactions with the AID; one stabilizing factor is the provision of a hydrophobic surface that promotes the expulsion of Snf1Ile152, the residue equivalent to Val135 in AMPKα2 (see Fig. 3 ▶ d). In Snf1 the side chain of Snf1Ile152 shifts out of the active site upon AID binding and moves to form part of a hydrophobic cluster with Snf1Leu341 from the AID, αC residues Snf1Leu88 and Snf1Tyr85 and αE residues Snf1Tyr146 and Snf1His150 (see Fig. 3 ▶ d). An Snf1-like AID-binding site may also be present in AMPK as each of these residues are either identical (see Figs. 3 ▶ a and 3 ▶ e) or have conservative substitutions (e.g. Snf1Ile152 to AMPKα2Val135). Moreover, Chen and coworkers showed that when this hydrophobic cluster was disrupted in mammalian AMPKs the AID no longer reduced protein-kinase activity (Chen et al., 2009 ▶). It could therefore be said that our human AMPKα2 structure represents an inactive state that could accommodate the binding of an Snf1-like AID with minimal conformational changes. Subtle differences exist in the kinase domains of human AMPKα2 and AID-bound Snf1. In particular, the HRD histidine does not move towards the C-terminal lobe in Snf1 and the backbone structure surrounding the expelled hydrophobic residue C-terminal to αE is not identical (see the overlay in Fig. 1 ▶ c). A low-resolution inactive AMPKα2-KD structure identical to ours has also recently been reported for a construct that contains the T172D phosphomimicking mutation (PDB code 2yza; S. Saijo, T. Takagi, S. Yoshikawa, S. Kishishita, M. Shirouzu & S. Yokoyama, unpublished work). This structure indicates that in solution, despite showing near-full activity, the phosphorylated kinase domain is still in equilibrium with the nonproductive DFG-out state. As it is active, phosphorylation must necessarily shift the various equilibria away from each of the nonproductive forms of the kinase; however, the conditions of crystallization presumably dominate this process in vitro.

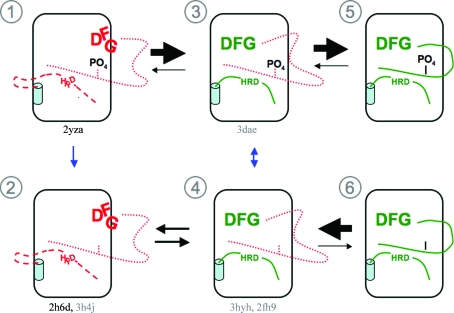

AMPK activation occurs primarily through phosphorylation-dependent activation mechanisms but also through the allosteric effect of AMP binding (Hardie & Carling, 1997 ▶). Phosphorylated AMPKα1 or AMPKα2 heterotrimers have been reported to show threefold or 13-fold increases in activity, respectively, in response to elevated AMP concentrations (Stein et al., 2000 ▶). One model attempting to explain this allosteric activation is through an AID-mediated link between the KD and the γ subunit; in this model, an AID-bound form of the KD represents a low-activity state in which interlobe motion is more restrained (Chen et al., 2009 ▶). Our analysis of the AMPKα2 and Snf1 catalytic and activation loops indicates that owing to the movements of catalytically important residues no catalysis would be possible in either form as is. The hydrophobic residues that form β6 in a catalytically active form of the kinase are involved in the formation of the S. pombe AID-binding site; thus, even a low-activity state would require complete AID dissociation followed by catalytic loop refolding in order to function. Most protein kinases have an inherent equilibrium between the productively folded and nonproductively folded forms of the C-terminal section of the activation loop (states 3–6 in Fig. 4 ▶). Phosphorylation site(s) within the loop, such as Thr172 in AMPKα2, drastically stabilize the productive form and often act as the primary activation signal for the kinase. We propose that in AMPK secondary equilibria also exist for productive and nonproductive forms of its DFG motif and catalytic loop (states 1 and 2 in Fig. 4 ▶). Post-transcriptional modifications, such as phosphorylation of the activation loop and the presence of AMP within the γ subunit, may alter these equilibria, enhancing activity by altering the conformational energy landscape to promote the formation of a catalytically active kinase. At any given time AMPK activity would therefore be determined by the percentage of molecules that are productively folded, which in turn is influenced by the factors stabilizing or destabilizing the novel nonproductive states.

Figure 4.

The possible conformational states of AMPK-KD are shown and numbered. Within each kinase representation the DFG motif is shown in either the productive (green) or the nonproductive (red) folded forms; the remaining C-terminal section of the activation loop as well as its phosphorylation status are shown below this, with the catalytic loop and its HRD triad at the bottom. Below each state the PDB-file coordinates for the structures adopting them are given; these are in grey for Snf1 structures and in black for AMPK structures. Blue arrows indicate changes in phospho-status and black arrows indicate conformational equilibria.

4. Conclusion

We have determined the structure of the kinase domain of AMPKα2 in an inactive state. Enzymatic action is hindered by distortions in the activation loop of the kinase domain and a restructuring of the catalytic loop into a previously unseen conformation packed against the C-terminal lobe. In order to fulfil its role as a master regulator of energy homeostasis, multiple inhibitory mechanisms keep the kinase domain of AMPK in check, preventing unwanted signalling events and enabling signal activity to be throttled to different levels depending on need. The inhibited state that we observe in the α2 kinase domain provides insight into the means by which catalytic activity may be regulated in vivo.

Interestingly, in its inhibited state the distorted AMPKα2 activation loop is similar to that of the insulin receptor tyrosine kinase, a protein from a distant evolutionary branch of the human kinome (Manning et al., 2002 ▶). Moreover, the newly identified catalytic loop structure of AMPKα2 is stabilized in its new state by residues that are highly conserved in the Ser/Thr protein kinase family (His131 and Asp196). Sequence constraints imposed by the catalytic mechanism of phosphotransfer within the kinase fold may have led to easily accessible inhibited conformations of the fold itself that have convergently evolved to become part of the regulatory mechanisms of a number of protein kinases.

Supplementary Material

PDB reference: AMPK kinase domain, 2h6d

References

- Bukhtiyarova, M., Karpusas, M., Northrop, K., Namboodiri, H. V. & Springman, E. B. (2007). Biochemistry, 46, 5687–5696. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Chen, L., Jiao, Z. H., Zheng, L. S., Zhang, Y. Y., Xie, S. T., Wang, Z. X. & Wu, J. W. (2009). Nature (London), 459, 1146–1149. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Crute, B. E., Seefeld, K., Gamble, J., Kemp, B. E. & Witters, L. A. (1998). J. Biol. Chem.273, 35347–35354. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Fujii, N., Jessen, N. & Goodyear, L. J. (2006). Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab.291, E867–E877. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Griffith, J., Black, J., Faerman, C., Swenson, L., Wynn, M., Lu, F., Lippke, J. & Saxena, K. (2004). Mol. Cell, 13, 169–178. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Han, S., Mistry, A., Chang, J. S., Cunningham, D., Griffor, M., Bonnette, P. C., Wang, H., Chrunyk, B. A., Aspnes, G. E., Walker, D. P., Brosius, A. D. & Buckbinder, L. (2009). J. Biol. Chem.284, 13193–13201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Hardie, D. G. (2007a). Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol.47, 185–210. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Hardie, D. G. (2007b). Nature Rev. Mol. Cell Biol.8, 774–785. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Hardie, D. G. & Carling, D. (1997). Eur. J. Biochem.246, 259–273. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Hardie, D. G., Hawley, S. A. & Scott, J. W. (2006). J. Physiol.574, 7–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Hardie, D. G. & Pan, D. A. (2002). Biochem. Soc. Trans.30, 1064–1070. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Harmange, J. C. et al. (2008). J. Med. Chem.51, 1649–1667. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Hubbard, S. R., Wei, L., Ellis, L. & Hendrickson, W. A. (1994). Nature (London), 372, 746–754. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Huse, M. & Kuriyan, J. (2002). Cell, 109, 275–282. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Iseli, T. J., Walter, M., van Denderen, B. J., Katsis, F., Witters, L. A., Kemp, B. E., Michell, B. J. & Stapleton, D. (2005). J. Biol. Chem.280, 13395–13400. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Jacobs, M. D., Caron, P. R. & Hare, B. J. (2008). Proteins, 70, 1451–1460. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Jones, R. G., Plas, D. R., Kubek, S., Buzzai, M., Mu, J., Xu, Y., Birnbaum, M. J. & Thompson, C. B. (2005). Mol. Cell, 18, 283–293. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Jones, T. A., Zou, J.-Y., Cowan, S. W. & Kjeldgaard, M. (1991). Acta Cryst. A47, 110–119. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Kemp, B. E. (2004). J. Clin. Invest.113, 182–184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Laskowski, R. A., MacArthur, M. W., Moss, D. S. & Thornton, J. M. (1993). J. Appl. Cryst.26, 283–291.

- Levinson, N. M., Kuchment, O., Shen, K., Young, M. A., Koldobskiy, M., Karplus, M., Cole, P. A. & Kuriyan, J. (2006). PLoS Biol.4, e144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Manning, G., Whyte, D. B., Martinez, R., Hunter, T. & Sudarsanam, S. (2002). Science, 298, 1912–1934. [DOI] [PubMed]

- McCoy, A. J., Grosse-Kunstleve, R. W., Adams, P. D., Winn, M. D., Storoni, L. C. & Read, R. J. (2007). J. Appl. Cryst.40, 658–674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Minor, W., Cymborowski, M., Otwinowski, Z. & Chruszcz, M. (2006). Acta Cryst. D62, 859–866. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Mol, C. D., Dougan, D. R., Schneider, T. R., Skene, R. J., Kraus, M. L., Scheibe, D. N., Snell, G. P., Zou, H., Sang, B. C. & Wilson, K. P. (2004). J. Biol. Chem.279, 31655–31663. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Morris, R. J., Perrakis, A. & Lamzin, V. S. (2003). Methods Enzymol.374, 229–244. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Murshudov, G. N., Vagin, A. A. & Dodson, E. J. (1997). Acta Cryst. D53, 240–255. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Musi, N. (2006). Curr. Med. Chem.13, 583–589. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Nayak, V., Zhao, K., Wyce, A., Schwartz, M. F., Lo, W. S., Berger, S. L. & Marmorstein, R. (2006). Structure, 14, 477–485. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Painter, J. & Merritt, E. A. (2006). Acta Cryst. D62, 439–450. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Rudolph, M. J., Amodeo, G. A., Bai, Y. & Tong, L. (2005). Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun.337, 1224–1228. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Scott, J. W., Hawley, S. A., Green, K. A., Anis, M., Stewart, G., Scullion, G. A., Norman, D. G. & Hardie, D. G. (2004). J. Clin. Invest.113, 274–284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Stein, S. C., Woods, A., Jones, N. A., Davison, M. D. & Carling, D. (2000). Biochem. J.345, 437–443. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Towler, M. C. & Hardie, D. G. (2007). Circ. Res.100, 328–341. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Xiao, B., Heath, R., Saiu, P., Leiper, F. C., Leone, P., Jing, C., Walker, P. A., Haire, L., Eccleston, J. F., Davis, C. T., Martin, S. R., Carling, D. & Gamblin, S. J. (2007). Nature (London), 449, 496–500. [DOI] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

PDB reference: AMPK kinase domain, 2h6d

PDB reference: AMPK kinase domain, 2h6d