Abstract

Purpose

To evaluate geriatric assessment (GA) domains in relation to clinically important outcomes in older breast cancer survivors.

Methods

Six hundred sixty women diagnosed with primary breast cancer in four US geographic regions (Los Angeles, CA; Minnesota; North Carolina; and Rhode Island) were selected with disease stage I to IIIA, age ≥ 65 years at date of diagnosis, and permission from attending physician to contact. Data were collected over 7 years of follow-up from consenting patients' medical records, telephone interviews, physician questionnaires, and the National Death Index. Outcomes included self-reported treatment tolerance and all-cause mortality. Four GA domains were described by six individual measures, as follows: sociodemographic by adequate finances; clinical by Charlson comorbidity index (CCI) and body mass index; function by number of physical function limitations; and psychosocial by the five-item Mental Health Index (MHI5) and Medical Outcomes Study Social Support Survey (MOS-SSS). Associations were evaluated using t tests, χ2 tests, and regression analyses.

Results

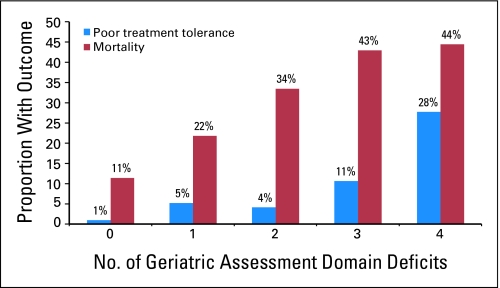

In multivariable regression including age and stage, three measures from two domains (clinical and psychosocial) were associated with poor treatment tolerance; these were CCI ≥ 1 (odds ratio [OR] = 2.49; 95% CI, 1.18 to 5.25), MHI5 score less than 80 (OR = 2.36; 95% CI, 1.15 to 4.86), and MOS-SSS score less than 80 (OR = 3.32; 95% CI, 1.44 to 7.66). Four measures representing all four GA domains predicted mortality; these were inadequate finances (hazard ratio [HR] = 1.89; 95% CI, 1.24 to 2.88; CCI ≥ 1 (HR = 1.38; 95% CI, 1.01 to 1.88), functional limitation (HR = 1.40; 95% CI, 1.01 to 1.93), and MHI5 score less than 80 (HR = 1.34; 95% CI, 1.01 to 1.85). In addition, the proportion of women with these outcomes incrementally increased as the number of GA deficits increased.

Conclusion

This study provides longitudinal evidence that GA domains are associated with poor treatment tolerance and predict mortality at 7 years of follow-up, independent of age and stage of disease.

INTRODUCTION

The fastest growing segment of the US population is adults ≥ 65 years old, which is projected to be 20% by 2030, with 70% of cancers occurring in this population.1,2 Breast cancer is the most common cancer among older women.3 Of the estimated 182,460 women diagnosed with breast cancer in 2008, almost half of the patients are women ≥ 65 years old, who have a relative survival rate of 89% at 5 years.4

Despite documented undertreatment, surgery and adjuvant treatment are well tolerated, effectively decrease relapse, and improve survival in many older patients with cancer, including women with breast cancer ≥ 80 years old.5–15 Studies show that older adults are willing to receive treatment for cancer just as readily as younger patients.16–21 However, the challenge of managing older patients with cancer is the ability to accurately assess whether the expected benefits of treatment outweigh risks. Because aging is a heterogeneous process, older patients with cancer need individualized management.5,22 Chronologic age is not a reliable estimate of future life expectancy, functional reserve, or the risk of treatment complications.23,24 Moreover, older patients with cancer are seldom comprehensively evaluated. Rather, they are managed primarily according to the treating physician's experience and extrapolations from clinical trials involving younger adults because efficacy data in older adults are lacking.25 This lack of comprehensive evaluation and efficacy data restricts the basis of treatment modifications to factors such as chronologic age and has retarded the development of interventions to optimize cancer treatment in older adults.

Multidimensional geriatric assessment (GA) is a promising strategy that captures a range of patient factors and can inform individualized treatment plans designed to optimize clinical management and health outcomes.26–29 Unfortunately, the efficacy evidence supporting cancer-specific GA (C-SGA) is indirect with limited longitudinal outcome-based follow-up.30–32 Nearly a decade's worth of publications, including recommendations from the International Society of Geriatric Oncology task force on GA and practice guidelines published by the National Comprehensive Cancer Network, recommend it's use and call for prospective studies to determine C-SGA's ability to predict relevant outcomes such as choice of treatment, treatment tolerance, treatment completion, survival, and quality of life in older patients with cancer.6,24,31,33-41 Notwithstanding, to our knowledge, there are few published prospective outcome-based studies of C-SGA.42–45 To address this void, we conducted a secondary analysis of baseline and 7-year data from a longitudinal follow-up study of older breast cancer survivors to evaluate GA domains in relation to clinically important outcomes in older breast cancer survivors.

METHODS

Study Population

The longitudinal study design and participant recruitment procedures have been reported elsewhere.46 In brief, patients with newly diagnosed breast cancer were identified through regular review of pathology reports at hospitals or collaborating tumor registries in four geographic US regions (Los Angeles, CA; Minnesota; North Carolina; and Rhode Island) with institutional review board approval of the study in each setting. Women were eligible for the study if they had stage I disease and a tumor diameter ≥ 1 cm or stage II to IIIA disease; were ≥ 65 years old on the date of diagnosis; and had permission from the attending physician to be contacted for study participation. Additional inclusion criteria included no prior history of primary breast cancer, no simultaneously diagnosed or treated second primary tumor at another site, ability to speak English, and competency for interview with satisfactory hearing. Eligible participants were mailed an enrollment package and called by a research staff member from each site who explained the study's purpose and participation requirements; potential participants were given an opportunity to decline participation, and those who verbally agreed to participate were asked to return a signed consent form approved by the institutional review board at each site. Three months after their definitive surgery, enrolled patients completed their first interview, resulting in a baseline study population of 660 women. After participant consent, each treating physician (oncologists, or surgeons when oncologist response was unavailable) was asked to complete a questionnaire assessing the physician's recommendations for tamoxifen treatment, resulting in a subpopulation of 480 women with a physician assessment.

Data Collection Procedures

Telephone interviews were conducted at 3 months (baseline) after definitive surgery. A definitive surgery date based on medical record review was assigned to each participant. Trained interviewers conducted the interview, which took on average 45 minutes to complete, and ascertained sociodemographic information, psychosocial status, health status, and breast cancer therapies received. Tumor and type of surgery were collected at time of diagnosis by medical record review at least 3 months after date of definitive surgery. Chemotherapy, radiation therapy, and tamoxifen use were obtained by interview. Before baseline interviews, treating physicians completed patient-specific tamoxifen treatment recommendation forms, including an overall assessment of health at breast cancer diagnosis. Mortality data were collected after up to 7 years of follow-up using the National Death Index and Social Security Death Index.

Analytic Variables

Treatment tolerance.

Patient interviews assessed overall past/present treatment tolerance using a single question that asked, “How well do you think that you are dealing with treatment side effects that you might have been experiencing or are experiencing?” Participants responded on a four-level scale (not too well at all, not too well, fairly well, and very well). We categorized poor treatment tolerance as not too well at all and not too well and good treatment tolerance as fairly well and very well.

Mortality.

Decedents were identified by first and last name, middle initial, Social Security number, date of birth, sex, race, marital status, and state of residence matched against National Death Index records; first and last name, middle initial, date of birth, and Social Security number were matched against Social Security Death Index records.

Sociodemographic characteristics.

We classified patient age as 65 to 69, 70 to 79, or ≥ 80 years old; race was classified as white or nonwhite; education was classified as less than high school, high school, or more than high school; marital status was classified as being or not being married; and financial status was classified as having or not having adequate finances to meet needs.

Breast cancer characteristics.

We classified disease stage as I to III using the TNM classification.47 We classified primary tumor therapy as mastectomy, breast-conserving surgery (BCS) followed by radiation therapy, or BCS alone. Receipt of chemotherapy and adjuvant tamoxifen therapy was classified as yes or no.

Health-related characteristics.

We determined the number and type of underlying diseases present at time of diagnosis from patient interview data using the Charlson comorbidity index (CCI) scaled from 0 to 3, with higher scores indicating more comorbidity.48–50 Self-rated health status before diagnosis was assessed using a single-item measure, as follows: “In general, would you say that your health before your breast cancer was diagnosed was excellent, very good, good, fair, or poor?” Self-rated health was dichotomized as excellent, very good, or good versus fair or poor. We asked physicians the following question: “Aside from her breast cancer, how would you rate this patient's health at time of admission to the hospital for breast cancer surgery?” Medical doctor–rated health was categorized as not ill/mildly ill or moderately ill/severely ill. Body mass index was derived from patients' baseline self-reported weight and height and dichotomized as ≤ 30 kg/m2 versus obesity (> 30 kg/m2). We calculated the total number of limiting physical functions based on the 10-item Physical Function Index of the Medical Outcomes Study Short Form-36 and categorized limitations as none or ≥ one limitation.51,52 We used count instead of derived physical function score for ease of interpretation and greater clinical transparency. General mental health was assessed using the five-item Mental Health Index (MHI5), a five-item measure of mental health from the Medical Outcomes Study Short Form-36 scored on a 0 to 100 scale (higher scores indicate better mental health).51,52 This scale has been widely used in many populations with chronic disease and cancer; a score of ≥ 80 is considered good general mental health, and an 8-point change is clinically significant.10,53-57 Social support was measured using a reduced set of eight items derived from the 19-item Medical Outcomes Study Social Support Scale (MOS-SSS).58 The scale (Cronbach's α > .89) is comprised of four emotional social support items (someone available to have a good time with, someone to turn to for suggestions about dealing with a personal problem, someone who understands your problems, and someone to love and make you feel wanted) and four instrumental social support items (help if confined to bed, help to take you to the doctor, help to prepare meals if you are unable, and help with daily chores).59 The score based on each of the eight items was scaled from 0 to 100, with higher scores indicating more support and a score of ≥ 80 considered good social support.

GA.

The following four GA domains were described by six individual measures: sociodemographic by adequate finances; clinical by CCI and body mass index; function by number of physical function limitations; and psychosocial by MHI5 and MOS-SSS. Deficits in GA domains were counted and dichotomized as ≤ two versus ≥ three, because zero or one deficit does not represent the essential GA advantage of incorporating multiple domains of information. Measures were selected for literature-based relevance from available study data.60 For example, social support was chosen instead of marital status because, although marital status is often used as proxy, social support is a more comprehensive measure shown to be related to the health and well-being of older adults.61,62

Other assessment measures.

Age, CCI, self-rated health, and medical doctor–rated health (described earlier) were considered other commonly used assessment measures.

Analytic Strategy

We obtained descriptive statistics (univariate, proportion, and frequency) on all study variables. We then examined bivariate distributions between independent and outcome variables (treatment tolerance and mortality) using Spearman correlations, t tests, χ2 tests, and Cochran-Armitage test for trend when appropriate. Unadjusted and multivariable adjusted logistic and Cox proportional hazards regression models were fit to evaluate associations between the outcome and independent variables. Independent variables demonstrating a significant association with outcome variables were evaluated for potential inclusion in multivariable models.63 Final adjusted models were validated by refitting the models using backward stepwise regression techniques. Small sample size precluded split-sample validation. Participants with missing data for independent or outcome variables were excluded from models (n < 19).

To evaluate potential bias, we compared characteristics of the subpopulation with physician assessment (n = 480) with characteristics of the baseline population (N = 660; Table 1) and the subpopulation without physician assessment (n = 180); no statistically significant differences were observed. Our findings, although less precise, remained unchanged when stratified by adjuvant treatment and/or restricted to the physician assessment subpopulation. All analyses were performed using SAS version 9.1 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC), and all P values were two-sided.

Table 1.

Baseline Sociodemographic, Clinical, and Health-Related Characteristics in a Population of Older Survivors of Breast Cancer (1997-2006)

| Characteristic | No. of Patients (N = 660) | % |

|---|---|---|

| Sociodemographic | ||

| Enrollment site | ||

| Los Angeles, CA | 150 | 23 |

| Rhode Island | 163 | 25 |

| Minnesota | 188 | 28 |

| North Carolina | 159 | 24 |

| Age, years | ||

| 65-69 | 172 | 26 |

| 70-79 | 372 | 56 |

| 80+ | 116 | 18 |

| Race | ||

| White | 620 | 94 |

| Other | 40 | 6.1 |

| Education, years | ||

| < 12 | 115 | 17 |

| 12 | 228 | 35 |

| > 12 | 316 | 48 |

| Married | 304 | 46 |

| Adequate finances | 587 | 90 |

| Breast cancer | ||

| Stage | ||

| I | 336 | 51 |

| II | 298 | 45 |

| III | 25 | 3.8 |

| Therapy | ||

| Mastectomy | 316 | 49 |

| BCS with radiation | 215 | 33 |

| BCS without radiation | 102 | 16 |

| Other | 17 | 2.6 |

| Chemotherapy | 145 | 22 |

| Tamoxifen | 498 | 75 |

| Health related | ||

| CCI ≥ 1 | 280 | 42 |

| Good self-rated health | 564 | 85 |

| Obesity (BMI > 30 kg/m2) | 140 | 21 |

| ≥ 1 physical limitation | 247 | 37 |

| Good mental health (MHI5 score ≥ 80) | 455 | 69 |

| High-level of social support (MOS-SSS score ≥ 80) | 333 | 51 |

| Geriatric assessment | ||

| Deficits in ≥ 3 GA domains | 286 | 43 |

Abbreviations: BCS, breast-conserving surgery; CCI, Charlson comorbidity index; BMI, body mass index; MHI5, five-item Mental Health Index; MOS-SSS, Medical Outcomes Study Social Support Survey; GA, geriatric assessment.

RESULTS

Characteristics of the Study Population

Sociodemographic, breast cancer, and health-related characteristics of the baseline study population (N = 660) are listed in Table 1. Approximately one quarter of the population came from each of the four study sites. The majority of patients were ≥ 70 years old. Most patients were white and had a high school education or greater. Approximately half of the women had stage I disease; the majority received either a mastectomy or BCS followed by radiation. Nearly 60% of women had a CCI of 0 (range, 0 to 2), 85% had self-reported good health, and less than one quarter were obese. Fifty percent or more of women exhibited high levels of general mental health and physical function.

GA Domains, Poor Treatment Tolerance, and Mortality

No difference in age in relation to treatment tolerance was observed, although as expected, decedents were somewhat older (Δ3.83 years; SE = 0.50 years; P < .0001). Women with poor treatment tolerance, compared with women with good treatment tolerance, had clinically meaningfully lower MHI5 scores (65.73 [SE = 3.7] v 81.48 [SE = 1.6], respectively; P = .0002) and MOS-SSS scores (64.02 [SE = 3.1] v 76.64 [SE = 1.8], respectively; P = .0004). In contrast, decedents, compared with patients still alive, showed no meaningful differences in MHI5 scores (77.64 [SE = 1.4] v 81.88 [SE = 1.8], respectively; P = .009) or MOS-SSS scores (73.52 [SE = 1.6] v 76.63 [SE = 1.9], respectively; P = .08).

Table 2 lists the crude and adjusted effects of age, stage, and individual measures representing GA domains in relation to outcomes in the baseline population. In regression models adjusted for age and stage, three measures from two domains (clinical and psychosocial) were associated with poor treatment tolerance. Four measures representing all four GA domains predicted mortality.

Table 2.

Effect Measures for Poor Treatment Tolerance and Mortality Based on Geriatric Assessment Domains in a 7-Year Longitudinal Study of Older Breast Cancer Survivors (N = 660; 1997-2006)

| Factor | Poor Treatment Tolerance* |

Mortality† |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crude OR | 95% CI | Adjusted OR‡ | 95% CI | Crude HR | 95% CI | Adjusted HR‡ | 95% CI | |

| Age, years | ||||||||

| 65-69 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||||

| 70-79 | 1.46 | 0.64 to 3.31 | 1.41 | 0.60 to 3.33 | 1.72 | 1.13 to 2.62 | 1.83 | 1.19 to 2.82 |

| 80+ | 1.18 | 0.40 to 3.48 | 0.92 | 0.27 to 3.14 | 4.29 | 2.74 to 6.73 | 4.20 | 2.60 to 6.81 |

| Stage | ||||||||

| I | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||||

| II | 1.84 | 0.92 to 3.66 | 1.93 | 0.94 to 3.97 | 1.45 | 1.07 to 1.96 | 1.39 | 1.02 to 1.89 |

| III | 1.94 | 0.41 to 9.05 | 1.28 | 0.15 to 10.82 | 2.91 | 1.67 to 5.06 | 2.76 | 1.54 to 4.94 |

| Sociodemographic domain | ||||||||

| Inadequate finances | 2.99 | 1.35 to 6.64 | 1.91 | 0.80 to 4.57 | 1.93 | 1.29 to 2.89 | 1.89 | 1.24 to 2.88 |

| Clinical domain | ||||||||

| CCI ≥ 1 | 2.75 | 1.38 to 5.49 | 2.49 | 1.18 to 5.25 | 1.73 | 1.30 to 2.31 | 1.38 | 1.01 to 1.88 |

| Obesity (BMI > 30 kg/m2) | 1.17 | 0.54 to 2.53 | 1.19 | 0.52 to 2.73 | 1.23 | 0.88 to 1.72 | 1.27 | 0.89 to 1.81 |

| Function domain | ||||||||

| ≥ 1 physical function limitation | 1.39 | 0.72 to 2.69 | 1.21 | 0.56 to 2.63 | 1.96 | 1.47 to 2.62 | 1.40 | 1.01 to 1.93 |

| Psychosocial domain | ||||||||

| MHI5 score < 80 | 3.68 | 1.88 to 7.22 | 2.36 | 1.15 to 4.86 | 1.58 | 1.18 to 2.12 | 1.34 | 1.01 to 1.85 |

| MOS-SSS score < 80 | 3.57 | 1.66 to 7.67 | 3.32 | 1.44 to 7.66 | 1.56 | 1.17 to 2.08 | 1.30 | 0.96 to 1.77 |

Abbreviations: OR, odds ratio; HR, hazard ratio; CCI, Charlson comorbidity index; BMI, body mass index; MHI5, five-item Mental Health Index; MOS-SSS, Medical Outcomes Study Social Support Survey.

Logistic regression.

Cox proportional hazards regression.

Regression models adjusted for all variables listed in table.

Figure 1 shows the proportion of the baseline population with either poor treatment tolerance or mortality in relation to the number of GA domain deficits. The proportion of women with a poor outcome statistically significantly increased as the number of deficits in GA domains increased, exhibiting an incremental increasing trend.

Fig 1.

Proportion of older survivors of breast cancer (N = 660) with poor treatment tolerance and mortality within each group of geriatric assessment domain deficits (1997 to 2006; Cochran-Armitage test for trend, P < .0001 for poor treatment tolerance and mortality).

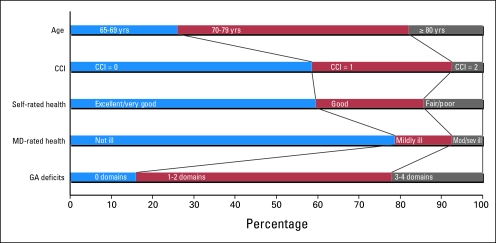

GA, Other Assessment Measures, Poor Treatment Tolerance, and Mortality in the Subpopulation With Physician Assessment

Figure 2 shows the subpopulation of women with a physician assessment in relation to different assessment measures including GA domains. The characterization of the subpopulation varied broadly. Of note, physician assessment of a patient's health status was the only measure not associated with poor treatment tolerance.

Fig 2.

Description of the subpopulation of older survivors of breast cancer with physician assessment (n = 480) based on age, comorbidity, self-rated health, medical doctor (MD) –rated health, and geriatric assessment domain deficits (1997 to 2006). CCI, Charlson comorbidty index; Mod/sev, moderately/severely; GA, geriatric assessment.

These variations were underscored by inconsistent cross-classification between assessment measures; 59.43% and 23.81% of women with ≥ three deficits in GA domains were assessed by physicians as not ill and had excellent/very good self-rated health, respectively. Correlations further emphasize the differences, with the strongest statistically significant correlation between number of GA deficits and CCI (r = 0.62; P < .0001) and weakest correlation between CCI and age (r = 0.07; P = .11). Although self-rated health and CCI seemed to have the most similar distributions, they were not the most strongly correlated measures (r = 0.38; P < .0001).

In this subpopulation of women with physician assessment, ≥ three deficits in GA domains was most strongly associated with poor treatment tolerance and among the strongest predictors of mortality (Table 3). CCI ≥ 1, fair/poor self-rated health, and having ≥ three deficits in GA domains were all strong statistically significant determinants of both poor treatment tolerance and mortality.

Table 3.

Effect Measures for Poor Treatment Tolerance and Mortality Based on Geriatric Assessment and Three Other Health Assessment Measures in a 7-Year Longitudinal Study of a Subpopulation of Older Survivors of Breast Cancer With Physician Assessment (n = 480; 1997-2006)

| Factor | Poor Treatment Tolerance |

Mortality |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI* | HR | 95% CI* | |

| CCI ≥ 1 | 2.61 | 1.17 to 5.83 | 1.82 | 1.28 to 2.57 |

| Fair/poor self-rated health | 4.25 | 1.86 to 9.69 | 2.33 | 1.55 to 3.50 |

| Moderately/severely ill MD-rated health | 1.34 | 0.38 to 4.83 | 2.67 | 1.69 to 4.21 |

| Deficits in ≥ 3 GA domains | 4.86 | 2.19 to 10.77 | 2.31 | 1.40 to 2.94 |

Abbreviations: OR, odds ratio; HR, hazard ratio; MD, medical doctor; CCI, Charlson comorbidity index; GA, geriatric assessment.

Results from four individual regression models for each outcome, adjusted for age, stage, and the assessment measure listed on the corresponding row.

DISCUSSION

This study provides longitudinal evidence that GA domains are associated with poor treatment tolerance and predict mortality at 7 years of follow-up, independent of age and stage of disease. Even in this select population (ie, a reasonably healthy functional population of older breast cancer survivors), differences in health according to type of assessment and variations in GA domains across outcomes were evident. Furthermore, the proportion of participants with poor treatment tolerance or mortality increased as the number of GA deficits increased. These findings highlight the need for assessment of a range of patient characteristics when treating older patients with cancer. They suggest that C-SGA may provide an effective tool to identify targets for intervention to optimize the management and outcomes (eg, lower rate of treatment adverse effects and improved survival) of older patients with cancer. It is conceivable that these results under-represent what might be seen in more heterogeneous populations characterized by, for example, less affluence, more comorbidity, or poorer functional status.

Chronologic age alone should not be the sole reason for not offering an older patient with cancer treatment; the effects of aging on function, physiology, and the availability of social supports are important and need to be considered during the treatment decision-making process. Our findings underscore this point and are supported by both the geriatric and cancer literature linking individual clinical, function, and psychosocial GA domains to increased risk of worse treatment tolerance and mortality.21,30-32,35,38,64 The added benefit of multidimensional GA is that it provides physicians and patients/families with information to guide clinical management and to identify vulnerabilities that may be mitigated by interdisciplinary interventions. Specifically, GA can identify reversible problems that may interfere with cancer treatment, such as poor mental health, insufficient social support, or functional limitations that might be modified to reduce their impact on treatment and/or treatment effects.

The measures in this study were not administered as part of a comprehensive GA or for patient care purposes. GA generally refers to in-person multidimensional clinical, functional, psychosocial, and environmental evaluation of an older patient's resources and problems as a basis for further treatment. In this study, information was collected by telephone interview. We also had no information regarding whether or not treating physicians used C-SGA in their practices, although this is unlikely. The deficits identified by the measures in this study were not reported back to physicians and, therefore, could not have directly influenced patient care or outcomes. The individual measures used in this study were brief, reliable, valid, predictive of morbidity and mortality in geriatric patients, and sensitive to change over time.60 Although not administered as part of a pretreatment objective assessment, they did predict cancer outcomes in this population and could be combined into a brief (ie, low physician/patient burden) GA for busy clinical settings and research purposes.5,65 We do not imply that these are the only GA domains or the best measures for implementation, but merely that these findings provide evidence of their potential as part of geriatric oncology care.

Several limitations of this study should be considered. These findings may not be generalizable to general populations of older patients with cancer or to populations outside the geographic areas included or the United States. Because of the eligibility criteria of the study, older women with cognitive impairment, advanced breast cancer, other cancers, or multiple primary cancers were excluded from this sample. In addition, our study population was a largely white, well-educated, fairly healthy group of older women, limiting generalizability to other populations of older breast cancer survivors. Another limitation is related to selection bias resulting from only a subset of women having had a physician assessment. However, comparison of women with physician assessment to those without assessment regarding sociodemographic, tumor, and treatment characteristics showed minimal differences between the two groups. The potential confounding effect of adjuvant treatment modalities in this research was minimal. However, caution should be exercised when interpreting these results because of imprecision and the challenge of confounding by indication.66 Lastly, we used a single question to define overall past/present treatment tolerance based on self-report. Results may have been different had we relied on past-only data resulting from physician assessment, relied on information in the medical record, or recognized toxicity criteria, all of which were unavailable.

This study demonstrates that GA domains can predict cancer-specific outcomes in older patients with breast cancer. Taken in context with other research seeking to identify which assessment tools best predict outcomes, it will add to the knowledgebase required to translate C-SGA into evidence-based practice. C-SGA offers clinicians and patients the promise of an effective strategy for integrating multiple factors into clinical decision making to optimize cancer care for older adults—a worthy goal for future GA research agendas and vital to the treatment and survivorship experience of the growing numbers of older patients with cancer.67

Footnotes

Supported by Grants No. CA106979, CA/AG 70818, and CA84506 from the National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, MD.

Presented in part at the 9th Annual Meeting of the International Society of Geriatric Oncology, October 16-18, 2008, Montreal, Quebec, Canada.

Authors' disclosures of potential conflicts of interest and author contributions are found at the end of this article.

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The author(s) indicated no potential conflicts of interest.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: Kerri M. Clough-Gorr, Rebecca A. Silliman

Financial support: Rebecca A. Silliman

Administrative support: Kerri M. Clough-Gorr

Provision of study materials or patients: Rebecca A. Silliman

Collection and assembly of data: Kerri M. Clough-Gorr, Soe Soe Thwin, Rebecca A. Silliman

Data analysis and interpretation: Kerri M. Clough-Gorr, Andreas E. Stuck, Soe Soe Thwin, Rebecca A. Silliman

Manuscript writing: Kerri M. Clough-Gorr, Andreas E. Stuck, Soe Soe Thwin, Rebecca A. Silliman

Final approval of manuscript: Kerri M. Clough-Gorr, Andreas E. Stuck, Soe Soe Thwin, Rebecca A. Silliman

REFERENCES

- 1.Administration on Aging, US Department of Health and Human Services: A profile of older Americans: 2007. http://www.aoa.gov/AoAroot/Aging_Statistics/Profile/2007/docs/2007profile.pdf.

- 2.Jemal A, Siegel R, Ward E, et al. Cancer statistics, 2007. CA Cancer J Clin. 2007;57:43–66. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.57.1.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.American Cancer Society. Breast cancer facts and figures, 2007-2008. http://www.cancer.org/downloads/STT/BCFF-Final.pdf.

- 4.Wieland D, Ferrucci L. Multidimensional geriatric assessment: Back to the future. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2008;63:272–274. doi: 10.1093/gerona/63.3.272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hurria A, Lichtman SM, Gardes J, et al. Identifying vulnerable older adults with cancer: Integrating geriatric assessment into oncology practice. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55:1604–1608. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01367.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Muss HB, Biganzoli L, Sargent DJ, et al. Adjuvant therapy in the elderly: Making the right decision. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:1870–1875. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.10.3457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Extermann M. Management issues for elderly patients with breast cancer. Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2004;5:161–169. doi: 10.1007/s11864-004-0048-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Muss HB. Adjuvant treatment of elderly breast cancer patients. Breast. 2007;16(suppl 2):S159–S165. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2007.07.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bouchardy C, Rapiti E, Blagojevic S, et al. Older female cancer patients: Importance, causes, and consequences of undertreatment. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:1858–1869. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.10.4208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Silliman RA, Troyan SL, Guadagnoli E, et al. The impact of age, marital status, and physician-patient interactions on the care of older women with breast carcinoma. Cancer. 1997;80:1326–1334. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.DeMichele A, Putt M, Zhang Y, et al. Older age predicts a decline in adjuvant chemotherapy recommendations for patients with breast carcinoma: Evidence from a tertiary care cohort of chemotherapy-eligible patients. Cancer. 2003;97:2150–2159. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goodwin JS, Hunt WC, Samet JM. Determinants of cancer therapy in elderly patients. Cancer. 1993;72:594–601. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19930715)72:2<594::aid-cncr2820720243>3.0.co;2-#. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Silliman RA, Balducci L, Goodwin JS, et al. Breast cancer care in old age: What we know, don't know, and do. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1993;85:190–199. doi: 10.1093/jnci/85.3.190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Alibhai SM, Krahn MD, Cohen MM, et al. Is there age bias in the treatment of localized prostate carcinoma? Cancer. 2004;100:72–81. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schrag D, Cramer LD, Bach PB, et al. Age and adjuvant chemotherapy use after surgery for stage III colon cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2001;93:850–857. doi: 10.1093/jnci/93.11.850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Extermann M, Albrand G, Chen H, et al. Are older French patients as willing as older American patients to undertake chemotherapy? J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:3214–3219. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.08.091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Silvestri G, Pritchard R, Welch HG. Preferences for chemotherapy in patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer: Descriptive study based on scripted interviews. BMJ. 1998;317:771–775. doi: 10.1136/bmj.317.7161.771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Slevin ML, Stubbs L, Plant HJ, et al. Attitudes to chemotherapy: Comparing views of patients with cancer with those of doctors, nurses, and general public. BMJ. 1990;300:1458–1460. doi: 10.1136/bmj.300.6737.1458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yellen SB, Cella DF, Leslie WT. Age and clinical decision making in oncology patients. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1994;86:1766–1770. doi: 10.1093/jnci/86.23.1766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bremnes RM, Andersen K, Wist EA. Cancer patients, doctors and nurses vary in their willingness to undertake cancer chemotherapy. Eur J Cancer. 1995;31A:1955–1959. doi: 10.1016/0959-8049(95)00513-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Extermann M, Balducci L, Lyman GH. What threshold for adjuvant therapy in older breast cancer patients? J Clin Oncol. 2000;18:1709–1717. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.8.1709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Balducci L, Beghe C. Cancer and age in the USA. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2001;37:137–145. doi: 10.1016/s1040-8428(00)00109-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wedding U, Honecker F, Bokemeyer C, et al. Tolerance to chemotherapy in elderly patients with cancer. Cancer Control. 2007;14:44–56. doi: 10.1177/107327480701400106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Senior Adult Oncology, Practice Guidelines in Oncology. ed 2. Fort Washington, PA: National Comprehensive Cancer Network; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Basso U, Tonti S, Bassi C, et al. Management of frail and not-frail elderly cancer patients in a hospital-based geriatric oncology program. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2008;66:163–170. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2007.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ellis G, Langhorne P. Comprehensive geriatric assessment for older hospital patients. Br Med Bull. 2004;71:45–59. doi: 10.1093/bmb/ldh033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stuck AE, Siu AL, Wieland GD, et al. Comprehensive geriatric assessment: A meta-analysis of controlled trials. Lancet. 1993;342:1032–1036. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(93)92884-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wieland D, Hirth V. Comprehensive geriatric assessment. Cancer Control. 2003;10:454–462. doi: 10.1177/107327480301000603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Huss A, Stuck AE, Rubenstein LZ, et al. Multidimensional preventive home visit programs for community-dwelling older adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2008;63:298–307. doi: 10.1093/gerona/63.3.298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chen CC, Kenefick AL, Tang ST, et al. Utilization of comprehensive geriatric assessment in cancer patients. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2004;49:53–67. doi: 10.1016/s1040-8428(03)00098-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Extermann M, Aapro M, Bernabei R, et al. Use of comprehensive geriatric assessment in older cancer patients: Recommendations from the task force on CGA of the International Society of Geriatric Oncology (SIOG) Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2005;55:241–252. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2005.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Extermann M, Hurria A. Comprehensive geriatric assessment for older patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:1824–1831. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.10.6559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lichtman SM. Guidelines for the treatment of elderly cancer patients. Cancer Control. 2003;10:445–453. doi: 10.1177/107327480301000602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cohen HJ. The cancer aging interface: A research agenda. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:1945–1948. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.10.6807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Maas HA, Janssen-Heijnen ML, Olde Rikkert MG, et al. Comprehensive geriatric assessment and its clinical impact in oncology. Eur J Cancer. 2007;43:2161–2169. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2007.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Balducci L, Extermann M. A practical approach to the older patient with cancer. Curr Probl Cancer. 2001;25:6–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Klepin H, Mohile S, Hurria A. Geriatric assessment in older patients with breast cancer. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2009;7:226–236. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2009.0016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schubert CC, Gross C, Hurria A. Functional assessment of the older patient with cancer. Oncology. 2008;22:916–922. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Marenco D, Marinello R, Berruti A, et al. Multidimensional geriatric assessment in treatment decision in elderly cancer patients: 6-year experience in an outpatient geriatric oncology service. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2008;68:157–164. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2008.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Droz JP, Chaladaj A. Management of metastatic prostate cancer: The crucial role of geriatric assessment. BJU Int. 2008;101(suppl 2):23–29. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2007.07486.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Albrand G, Terret C. Early breast cancer in the elderly: Assessment and management considerations. Drugs Aging. 2008;25:35–45. doi: 10.2165/00002512-200825010-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Extermann M, Meyer J, McGinnis M, et al. A comprehensive geriatric intervention detects multiple problems in older breast cancer patients. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2004;49:69–75. doi: 10.1016/s1040-8428(03)00099-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hurria A, Gupta S, Zauderer M, et al. Developing a cancer-specific geriatric assessment: A feasibility study. Cancer. 2005;104:1998–2005. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.McCorkle R, Strumpf NE, Nuamah IF, et al. A specialized home care intervention improves survival among older post-surgical cancer patients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2000;48:1707–1713. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2000.tb03886.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rao AV, Hsieh F, Feussner JR, et al. Geriatric evaluation and management units in the care of the frail elderly cancer patient. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2005;60:798–803. doi: 10.1093/gerona/60.6.798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Silliman RA, Guadagnoli E, Rakowski W, et al. Adjuvant tamoxifen prescription in women 65 years and older with primary breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:2680–2688. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.08.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fleming ID, Cooper JS, Henson DE, et al. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. ed 5. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, et al. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: Development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40:373–383. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Charlson ME, Sax FL, MacKenzie CR, et al. Assessing illness severity: Does clinical judgment work? J Chronic Dis. 1986;39:439–452. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(86)90111-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Katz JN, Chang LC, Sangha O, et al. Can comorbidity be measured by questionnaire rather than medical record review? Med Care. 1996;34:73–84. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199601000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ware JE. SF-36 Health Survey, Manual and Interpretation Guide. Boston, MA: The Health Institute; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ware JE, Jr, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36): I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care. 1992;30:473–483. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Clough-Gorr KM, Ganz PA, Silliman RA. Older breast cancer survivors: Factors associated with change in emotional well-being. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:1334–1340. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.09.8665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Demissie S, Silliman RA, Lash TL. Adjuvant tamoxifen: Predictors of use, side effects, and discontinuation in older women. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:322–328. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.2.322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ganz PA, Coscarelli A, Fred C, et al. Breast cancer survivors: Psychosocial concerns and quality of life. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 1996;38:183–199. doi: 10.1007/BF01806673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ganz PA, Rowland JH, Desmond K, et al. Life after breast cancer: Understanding women's health-related quality of life and sexual functioning. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16:501–514. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1998.16.2.501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Silliman RA, Dukes KA, Sullivan LM, et al. Breast cancer care in older women: Sources of information, social support, and emotional health outcomes. Cancer. 1998;83:706–711. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sherbourne CD, Stewart AL. The MOS social support survey. Soc Sci Med. 1991;32:705–714. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(91)90150-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ganz PA, Guadagnoli E, Landrum MB, et al. Breast cancer in older women: Quality of life and psychosocial adjustment in the 15 months after diagnosis. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:4027–4033. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.08.097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.McDowell I. Measuring health: A guide to rating scales and questionnaires. ed 3. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lubben J, Gironda M. Social support networks. In: Osterweil D, Brummel-Smith K, Beck JC, editors. Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment. New York, NY: McGraw Hill; 2000. pp. 121–137. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lubben J, Gironda M. Centrality of social ties to the health and well-being of older adults. In: Berkman B, Harootyan U, editors. Social Work and Health Care in an Aging Society: Education, Practice, and Research. New York, NY: Springer; 2003. pp. 319–350. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Greenland S. Chapter 21: Introduction to regression modeling. In: Rothman K, Greenland S, editors. Modern Epidemiology. ed 2. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott-Raven; 1998. pp. 401–434. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Satariano WA, Ragland DR. The effect of comorbidity on 3-year survival of women with primary breast cancer. Ann Intern Med. 1994;120:104–110. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-120-2-199401150-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Overcash JA, Beckstead J, Moody L, et al. The abbreviated comprehensive geriatric assessment (aCGA) for use in the older cancer patient as a prescreen: Scoring and interpretation. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2006;59:205–210. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2006.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Bosco JLF, Silliman RA, Thwin SS, et al. A most stubborn bias: No adjustment method fully resolves confounding by indication in observational studies. J Clin Epidemiol. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.03.001. epub ahead of print on May 19, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Clough-Gorr KM, Silliman RA. Translation requires evidence: Does cancer-specific CGA lead to better care and outcomes? Oncology. 2008;22:925–928. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]