Abstract

Purpose

To determine whether spiritual care from the medical team impacts medical care received and quality of life (QoL) at the end of life (EoL) and to examine these relationships according to patient religious coping.

Patients and Methods

Prospective, multisite study of patients with advanced cancer from September 2002 through August 2008. We interviewed 343 patients at baseline and observed them (median, 116 days) until death. Spiritual care was defined by patient-rated support of spiritual needs by the medical team and receipt of pastoral care services. The Brief Religious Coping Scale (RCOPE) assessed positive religious coping. EoL outcomes included patient QoL and receipt of hospice and any aggressive care (eg, resuscitation). Analyses were adjusted for potential confounders and repeated according to median-split religious coping.

Results

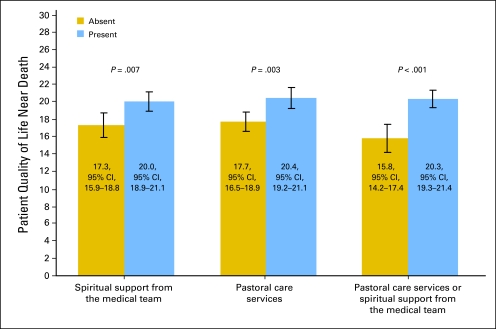

Patients whose spiritual needs were largely or completely supported by the medical team received more hospice care in comparison with those not supported (adjusted odds ratio [AOR] = 3.53; 95% CI, 1.53 to 8.12, P = .003). High religious coping patients whose spiritual needs were largely or completely supported were more likely to receive hospice (AOR = 4.93; 95% CI, 1.64 to 14.80; P = .004) and less likely to receive aggressive care (AOR = 0.18; 95% CI, 0.04 to 0.79; P = .02) in comparison with those not supported. Spiritual support from the medical team and pastoral care visits were associated with higher QOL scores near death (20.0 [95% CI, 18.9 to 21.1] v 17.3 [95% CI, 15.9 to 18.8], P = .007; and 20.4 [95% CI, 19.2 to 21.1] v 17.7 [95% CI, 16.5 to 18.9], P = .003, respectively).

Conclusion

Support of terminally ill patients' spiritual needs by the medical team is associated with greater hospice utilization and, among high religious copers, less aggressive care at EoL. Spiritual care is associated with better patient QoL near death.

INTRODUCTION

With physical decline and death in view, many patients with advanced illness seek hope,1–3 meaning,4,5 and comfort5–7 in their connection to the transcendent. Spirituality can be characterized as an individual's relationship to and experience of the transcendent, whether through religion or other paths.8 Religion, a related concept, can be described as a set of beliefs about the transcendent shared by a community, often associated with common sacred writings and practices.8,9

The majority of patients with advanced illness view religion and/or spirituality (R/S) as personally important10–13 and experience spiritual needs.14–16 Among ethnic minorities facing advanced illness, the importance of R/S12 and the frequency of spiritual needs15 is particularly prominent. R/S is also associated with improved coping and quality of life (QoL),13,17,18 whereas negative religious coping (eg, anger with God) is associated with inferior QoL.17,19 Patient R/S also has important implications for medical decision making,12,20 with patients exhibiting high religious coping having a higher likelihood of receiving aggressive care at the end of life (EoL).21

Although spiritual care—care that recognizes patient R/S and attends to spiritual needs—has been incorporated into national care guidelines, including the Joint Commission22 and the National Consensus Project on Quality Palliative Care,23 it remains notably absent for most patients at the EoL.12 Preliminary data suggest that spiritual care is associated with better patient QoL.12,24 However, there is a paucity of data examining the prospective associations of spiritual care on patient well-being just before death (QoL near death). Furthermore, the association of religious coping with more aggressive care at EoL21 prompts the question of whether medical care that recognizes the spiritual components of facing terminal illness may aid in preventing futile, aggressive care at the EoL by addressing spiritual needs and better integrating patients' R/S beliefs into discussions regarding EoL care. Hence data characterizing the prospective associations of spiritual care with patient QoL and medical care near death are required.

The Coping with Cancer study is a multi-institutional study of patients with advanced cancer designed to investigate how psychosocial factors, including spiritual care, influence patients' EoL care and QoL near death. We hypothesized that spiritual care would be associated with better patient QoL and less aggressive care near death. We secondarily hypothesized that the associations of spiritual care with these EoL outcomes would be greatest among those exhibiting high religious coping.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Study Sample

Patients were recruited from September 1, 2002, to August 28, 2008, from seven outpatient sites: Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA; New Hampshire Oncology Hematology, Hookset, NH; Parkland Hospital, Simmons Comprehensive Cancer Center, Dallas, TX; Veterans' Affairs Connecticut Comprehensive Cancer Clinics, West Haven, CT; and Yale University Cancer Center, New Haven, CT. Eligibility criteria included an advanced cancer diagnosis with disease refractory to first-line chemotherapy or presence of metastatic disease; age ≥ 20 years; presence of an informal (nonpaid) caregiver; and adequate stamina to complete the interview. Exclusion criteria for patient-caregiver dyads included patient or caregiver meeting criteria for dementia or delirium by neurocognitive examination or inability to speak English or Spanish. All participants provided written, informed consent according to protocols approved by participating centers' human subjects committees.

Study Protocol

Research staff underwent a 2-day training program in the protocol, chart extraction, and interviewing. Potential participants were identified from outpatient appointment schedules. On enrollment, patients participated in a baseline interview. Patients' medical records were reviewed to extract disease/treatment variables. A second assessment was performed within 2 to 3 weeks after the participant's death, including chart extraction to obtain EoL care information and a postmortem interview of a formal or informal caregiver present during the final week of life.

Of 944 eligible patients approached, 670 patients (71%) accepted participation. Recruitment did not include specific reference to R/S. The most common reasons for nonparticipation included “not interested” (n = 109) and “caregiver refuses” (n = 35). There were no significant differences between nonparticipants and participants in sex, age, race, or education. At the time of this analysis, 379 patients had died, and a postmortem interview was performed. Of 379 patients, 36 patients lacked complete postmortem or spiritual care data, resulting in a final sample of 343 patients (91% of 379).

Baseline Measures

Spiritual care variables.

Spiritual care from the medical system (eg, doctors, nurses, chaplains) was assessed by two patient-reported measures: (1) a rating of spiritual support from the medical team scored from 0 to 4, and (2) receipt of pastoral care services. The spiritual care questions and response options are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Baseline Patient and Postmortem Caregiver Interview Questions

| Question | Item Response Option |

|---|---|

| Baseline patient interview | |

| Medical system spiritual care items | |

| To what extent are your religious/spiritual needs being supported by the medical system (eg, doctors, nurses, chaplains)? | Not at all |

| To a small extent | |

| To a moderate extent | |

| To a large extent | |

| Completely supported | |

| Have you received pastoral care services within the clinic or hospital? | Yes or No |

| Religious community spiritual support items | |

| To what extent are your religious/spiritual needs being supported by your religious community (eg, clergy, members of your congregation)? | Not at all |

| To a small extent | |

| To a moderate extent | |

| To a large extent | |

| Completely supported | |

| Have you been visited by a member of the clergy from outside of the hospital system? | Yes or No |

| Patient–physician relationship items | |

| Do you think your doctors see you as a whole person? | Yes or No |

| Do you think your doctors here treat you with respect? | Yes or No |

| Do you respect your doctors here? | Yes or No |

| Do you trust your doctors here? | Yes or No |

| How comfortable are you asking your doctor questions about your care? | Very uncomfortable |

| Fairly uncomfortable | |

| Neither comfortable or uncomfortable | |

| Fairly comfortable | |

| Very comfortable | |

| Baseline end-of-life care items | |

| Have you and your doctor discussed any particular wishes you have about the care you would want to receive if you were dying? | Yes or No |

| Do you have a signed: (1) living will, (2) health care proxy and/or durable power of attorney, (3) both, or (4) neither? | 1, 2, 3, or 4 |

| If you could choose, would you prefer: (1) a course of treatment that focused on extending life as much as possible, even if it meant more pain and discomfort, or (2) a plan of care that focused on relieving pain and discomfort as much as possible, even if that meant not living as long? | 1 or 2 |

| Postmortem caregiver interview | |

| Quality-of-life near-death items | |

| In your opinion, just before the death of the patient (his/her last week, or when you last saw the patient), how would you rate his/her level of psychological distress? | 0 (no distress) to 10 (extremely upset) |

| In your opinion, just before the death of the patient (his/her last week, or when you last saw the patient), how would you rate his/her level of physical distress? | 0 (no distress) to 10 (extremely distressed) |

| In your opinion, how would you rate the overall quality of the patient's death/last week of life? | 0 (worst possible) to 10 (best possible) |

Religious variables.

Patients rated religion as “not at all,” “somewhat,” or very important.” Religious community spiritual support was assessed by a patient-reported rating (0 to 4) of spiritual support from religious communities and receipt of clergy visits (Table 1). Pargament's Brief Religious Coping Scale (RCOPE),25 a previously validated, 14-item questionnaire, measured positive and negative religious coping, with possible scores of 0 to 21 (with higher scores indicating greater religious coping).

Other baseline variables.

The McGill QoL questionnaire is a previously validated instrument26,27 designed to measure QoL at all stages of life-threatening illness that includes physical, psychological, existential, support, and overall QoL subscales. Items were scored 0 to 10, reverse coded where appropriate, and summed (with higher scores reflecting better QoL). Analogous to the QoL at EoL measure, patient baseline QoL was assessed with the physical, psychological, and overall QoL domains (possible 0 to 70); the existential and support domains were used separately as measures of baseline existential well-being (possible 0 to 60) and social support (possible 0 to 20). To control for confounding of spiritual care with site/practitioner-specific tendencies that might be associated with study outcomes (eg, sites where practitioners perform spiritual care may more frequently refer to hospice), recruitment sites were categorized according to spiritual supportiveness: (1) Simmons Comprehensive Cancer Center, Parkland Hospital, and New Hampshire Oncology Hematology (44% to 54% of patients reporting minimal to no spiritual support); or (2) Yale University Cancer Center, Veterans' Affairs Connecticut Comprehensive Cancer Clinics, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, and Massachusetts General Hospital (83% to 99% reporting minimal to no spiritual support). The patient-doctor relationship was assessed with five items (Table 1, scored 0 to 1) measuring trust, mutual respect, feeling viewed as a whole person, and comfort asking questions about care that were summed (higher scores indicating a better relationship). A history of an EoL discussion with a physician, presence of advanced directives, and patients' preferences for aggressive versus nonaggressive EoL care were also assessed (Table 1). Age, sex, race/ethnicity (dichotomized to white v nonwhite), years of education, and insurance status were patient reported. Karnofsky performance status was obtained by physician assessment.

EoL Outcomes

EoL care.

Hospice care at EoL was defined as receipt of inpatient or outpatient hospice versus no hospice care in the last week of life. Aggressive EoL care was defined by having received one or more of the following established indicators in the last week of life: care in an intensive care unit, ventilation, or resuscitation.28

QoL near death.

Postmortem interviews of caregivers contained three items assessing patient QoL near death (Table 1): psychological distress near death, physical distress near death, and overall QoL near death. Items (scored 0 to 10) were reverse coded where appropriate and summed (with higher scores reflecting better QoL near death, possible 0 to 30). Caregiver assessments of patient QoL near death are considered an adequate surrogate based on the significant, positive association between caregiver and patient assessments of baseline patient QoL (McGill QoL scale, r = 0.55, P < .001).

Statistical Analysis

To compare the relationship of spiritual support from the medical team with receipt of pastoral care services, χ2 testing was used. Univariate relationships of the spiritual care variables to EoL care and QoL near death were analyzed using logistic regression for the dichotomous EoL outcomes and linear regression for the continuous QoL near death outcome.

Simultaneous multivariable logistic regression models assessed the relationships of the spiritual care variables to the EoL care measures. Spiritual support from the medical system was categorized into tertiles (“not at all supported,” “supported to a small or moderate extent,” and “largely or completely supported”) for this analysis, with “not at all supported” being the referent category. All models were adjusted for variables potentially related to spiritual care and to EoL care, including the following: race,29,30 EoL treatment preferences,31,32 EoL discussion,31,33 advance care planning, positive religious coping,21 and religiousness.12,34 EoL care models were also adjusted for religious community spiritual support, the patient-physician relationship, and recruitment site. Additional confounds considered were age, sex, education, health insurance status, performance status, baseline existential well-being, baseline social support, baseline QoL, negative religious coping, and receipt of visits from outside hospital/clinic clergy. Variables were entered into the model if they changed the spiritual care parameter estimate by more than 10% and retained when the P value remained significant (P < .05) after controlling for other confounds. Multivariable models were repeated according to median-split positive religious coping (building on data demonstrating that high religious copers, defined by median split, have an increased risk of aggressive care at EoL21).

Simultaneous multivariable linear regression models determined the relationships of the spiritual care variables to QoL at EoL. Given data supporting an association between EoL care and QoL near death,31 all models were adjusted for receipt of hospice and aggressive EoL care. All QoL models were adjusted for baseline QoL, existential well-being, social support, the person reporting QoL near death (informal v a formal caregiver), recruitment site, spiritual support from religious communities, and the patient-physician relationship. Additional confounds considered were age, sex, race, education, health insurance status, performance status, religiousness, positive religious coping, negative religious coping, and receipt of outside hospital clergy visits. Variables were entered into the model if they changed the spiritual care parameter estimate by more than 10% and retained when the P value remained significant (P < .05) after controlling for other confounds. Multivariable analyses were repeated as an analysis of variance procedure with least-square means to compare near-death QoL estimates in patients for whom spiritual care was absent versus present, including the following: (1) receipt of spiritual support from the medical team (absent when spiritual needs were not at all supported and present when they were supported to a small extent or more), (2) receipt of pastoral care services, and (3) receipt of any spiritual care (absent when patients reported both no pastoral care services and spiritual needs not at all supported and present when patients reported receipt of pastoral care or any spiritual support from the medical team). The multivariable model assessing the association of receipt of spiritual care with QoL near death was repeated in high and low religious copers, and least-square mean QoL estimates were obtained. Statistical analyses were performed with SAS version 9.1 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). All reported P values are two-sided and considered significant when less than .05.

RESULTS

Sample Baseline and EoL Characteristics

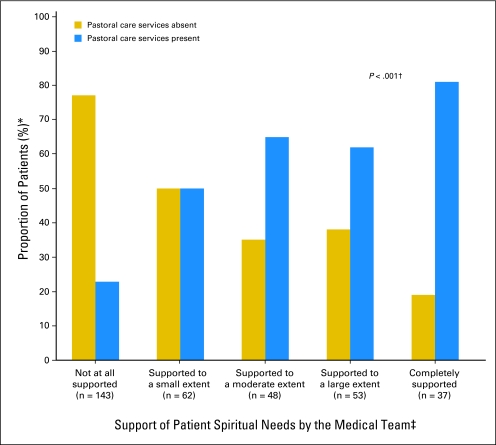

Patient baseline characteristics are shown in Table 2. The majority (60%) reported their spiritual needs were minimally or not at all supported, and 54% had not received pastoral care visits. Figure 1 displays receipt of pastoral care services by spiritual support from the medical team.

Table 2.

Baseline Characteristics of the Study Sample (n = 343)

| Characteristic | No. of Patients | % |

|---|---|---|

| Age, years | ||

| Mean | 58.3 | |

| SD | 12.5 | |

| Male sex | 185 | 53.9 |

| Nonwhite race | 128 | 37.3 |

| Education, years | ||

| Mean | 12.4 | |

| SD | 4.0 | |

| Health insurance | 193 | 56.3 |

| Karnofsky performance status* | ||

| Mean | 63.2 | |

| SD | 16.1 | |

| Recruitment site | ||

| Yale Cancer Center (CT) | 66 | 19.2 |

| Veterans Association of Connecticut Cancer Center (CT) | 13 | 3.8 |

| Simmons Comprehensive Cancer Center (TX) | 34 | 9.9 |

| Parkland Hospital (TX) | 154 | 44.9 |

| Dana-Farber Cancer Institute/Massachusetts General Hospital (MA) | 7 | 2.0 |

| New Hampshire Oncology Hematology (NH) | 66 | 19.2 |

| McGill Quality of life† | ||

| Mean | 45.1 | |

| SD | 14.2 | |

| Existential well-being† | ||

| Mean | 45.7 | |

| SD | 10.2 | |

| Social support† | ||

| Mean | 17.2 | |

| SD | 3.4 | |

| Religiousness | ||

| Not at all important | 38 | 11.1 |

| Somewhat important | 71 | 20.7 |

| Very important | 233 | 67.9 |

| Positive religious coping‡ | ||

| Mean | 11.1 | |

| SD | 6.4 | |

| Negative religious coping§ | ||

| Mean | 2.1 | |

| SD | 3.6 | |

| Spiritual support from medical system | ||

| Not at all | 143 | 41.6 |

| To a small extent | 62 | 18.1 |

| To a moderate extent | 48 | 14.0 |

| To a large extent | 53 | 15.5 |

| Completely supported | 37 | 10.8 |

| Receipt of pastoral care services in hospital or clinic | 158 | 46 |

| Spiritual support from religious communities | ||

| Not at all | 110 | 32.1 |

| To a small extent | 43 | 12.5 |

| To a moderate extent | 43 | 12.5 |

| To a large extent | 55 | 16.0 |

| Completely supported | 92 | 26.8 |

| Receipt of visits from clergy outside the medical system | 152 | 44 |

| End-of-life discussion with a physician | 126 | 37 |

| Patient-physician relationship‖ | ||

| Mean | 4.8 | |

| SD | 0.5 | |

| Preference for aggressive treatment measures at end of life | 86 | 25 |

NOTE. Data were missing in < 3% of patients for the following variables: health insurance status, Karnofsky performance status, recruitment site, quality of life, existential well-being, social support, religiousness, positive religious coping, negative religious coping, patient-physician relationship, and preferences for aggressive treatment measures at end of life.

Abbreviation: SD, standard deviation.

A measure of functional status that is predictive of survival, where 0 is dead and 100 is perfect health.

A validated measure of quality of life with five domains: overall quality of life, physical, psychological, existential, and social support. Existential items and support items were removed and used as separate predictors. McGill quality of life, possible scores 0 to 70. Social support, possible scores 0 to 20. Existential well-being, possible scores 0 to 60.

A measure of positive religious appraisals in coping with illness (eg, “I've been seeking God's love and care”), scale 0 to 21.

A measure of negative religious appraisals in coping with illness (eg, “I've been wondering whether God has abandoned me”), scale 0 to 21.

Measure of patient-physician relationship (scale 0 to 5) assessing patient: trust in the physician, sense of being cared for as a “whole person,” sense of being respected, respect for the physician, and comfort asking questions about care.

Fig 1.

Receipt of hospital/clinic pastoral care services by spiritual support from the medical team among patients with advanced cancer (n = 343). (*) Percentage represents the proportion of patients receiving or not receiving pastoral care visits over total patients in each spiritual support category. (†) χ2 test, df = 4. (‡) Medical team includes all health care providers involved in the patient's care in the medical setting, such as doctors, nurses, and chaplains.

Patients died a median of 116 days (interquartile range, 5 to 255 days) after the baseline interview. In the final week of life, 251 patients (73%) received hospice care and 58 patients (17%) received any aggressive care. Patients' mean near-death QoL score was 19.0 (standard deviation = 7.9).

Spiritual Care and Medical Care Received at EoL

The adjusted associations of spiritual care to EoL care are shown in Table 3. Patients whose spiritual needs were largely or completely supported by the medical team were more likely to receive hospice care at EoL. Spiritual support from the medical team was not associated with receipt of aggressive EoL care in the full sample. Receipt of pastoral care services was not associated with receiving hospice (adjusted odds ratio [AOR] = 1.04; 95% CI, 0.60 to 1.79; P = .89) or aggressive care (AOR = 1.42; 95% CI, 0.69 to 2.91; P = .34) at the EoL. In analyses according to religious coping, pastoral care services were not associated with receipt of hospice in the high (AOR = 1.05; 95% CI, 0.50 to 2.22; P = .68) or low religious coping group (AOR = 1.17; 95% CI, 0.49 to 2.80; P = .72) and was not associated with receipt of aggressive care in high (AOR = 0.82; 95% CI, 0.29 to 2.32; P = .72) or low religious copers (AOR = 2.34; 95% CI, 0.66 to 8.30; P = .19). High religious coping patients whose spiritual needs were largely or completely supported by the medical team were more likely to receive hospice and less likely to receive aggressive care at the EoL in comparison with those not receiving spiritual support (Table 4).

Table 3.

Odds of Receiving Hospice Care and Aggressive Life-Sustaining Interventions at the End of Life by Patient-Rated Spiritual Support From the Medical Team (n = 325)

| Patient-Rated Spiritual Support From the Medical Team | Received Hospice Care at the End of Life |

Received Aggressive Care at the End of Life* |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adjusted OR† | 95% CI | P | Adjusted OR† | 95% CI | P | |

| Spiritual needs not at all supported | Ref | Ref | ||||

| Spiritual needs supported to a small or moderate extent | 1.38 | 0.75 to 2.54 | .31 | 1.70 | 0.77 to 3.78 | .19 |

| Spiritual needs supported to a large extent or completely | 3.53 | 1.53 to 8.12 | .003 | 0.46 | 0.15 to 1.36 | .16 |

NOTE. Sample was reduced to 325 patients because of missing data. Analyses were repeated with missing data imputed to their mean values (n = 343), and the results were unchanged.

Abbreviations: OR, odds ratio; Ref, reference category.

Receipt of aggressive end-of-life care was defined as any of the following in the last week of life: care in an intensive care unit, resuscitation, or ventilation.

Adjusted models controlled for race, recruitment site, religiousness, positive religious coping, religious community spiritual support, advanced care planning, end-of-life treatment preferences, end-of-life discussion, and patient–physician relationship.

Table 4.

Odds of Receiving Hospice Care and Aggressive Life-Sustaining Interventions at the End of Life for High and Low Religious Coping Patients According to Patient-Rated Spiritual Support From the Medical Team (n = 325)

| Patient-Rated Spiritual Support From the Medical Team | Received Hospice Care at the End of Life |

Received Aggressive Care at the End of Life* |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adjusted OR† | 95% CI | P | Adjusted OR† | 95% CI | P | |

| High religious coping patients (n = 168) | ||||||

| Spiritual needs not at all supported (n = 55) | Ref | Ref | ||||

| Spiritual needs supported to a small or moderate extent (n = 53) | 1.82 | 0.70 to 4.72 | .23 | 1.62 | 0.37 to 7.14 | .52 |

| Spiritual needs supported to a large extent or completely supported (n = 60) | 4.93 | 1.64 to 14.80 | .004 | 0.18 | 0.04 to 0.79 | .02 |

| Low religious coping patients (n = 157) | ||||||

| Spiritual needs not at all supported (n = 78) | Ref | Ref | ||||

| Spiritual needs supported to a small or moderate extent (n = 57) | 1.08 | 0.45 to 2.62 | .86 | 3.14 | 0.86 to 11.52 | .08 |

| Spiritual needs supported to a large extent or completely supported (n = 22) | 3.73 | 0.74 to 18.74 | .11 | 0.53 | 0.05 to 6.24 | .61 |

NOTE. Sample was reduced to 325 patients because of missing data. Analyses were repeated with missing data imputed to their mean values (n = 343), and the results were unchanged.

Abbreviations: OR, odds ratio; Ref, reference category.

Receipt of aggressive end-of-life care was defined as any of the following in the last week of life: care in an intensive care unit, resuscitation, or ventilation.

Adjusted models controlled for race, recruitment site, religiousness, positive religious coping, religious community spiritual support, advanced care planning, end-of-life treatment preferences, end-of-life discussion, and patient–physician relationship.

Spiritual Care and Patient QoL at the EoL

Greater spiritual support from the medical team was associated with better patient QoL near death, both in unadjusted (standardized β = 0.11, P = .047) and adjusted models (standardized β = 0.13, P = .04). Receipt of pastoral care services was associated with better patient QoL near death in unadjusted (standardized β = 0.12, P = .02) and adjusted models (standardized β = 0.17, P = .003). Among patients reporting spiritual support only from nonchaplaincy medical caregivers (eg, doctors, nurses), greater spiritual support was associated with improved patient QoL near death (adjusted standardized β = 0.18, P = .03). Adjusted near-death QoL estimates revealed significantly higher QoL scores among those receiving spiritual care (Fig 2). Receipt of any spiritual care was associated with better near-death QoL scores in both low (20.4 [95% CI, 18.8 to 22.0] v 16.1 [95% CI, 14.0 to 18.1], P = .003) and high religious coping patients (20.1 [95% CI, 18.8 to 21.4] v 15.9 [95% CI, 13.2 to 18.5], P = .006).

Fig 2.

Adjusted estimates of quality of life near death by receipt of spiritual care in patients with advanced cancer (n = 299). All models are adjusted for baseline quality of life, baseline social support, baseline existential well-being, recruitment site, patient-physician relationship, spiritual support from religious communities, receipt of outside-hospital clergy visits, receipt of hospice care at end of life, receipt of any aggressive care at end of life, and the person reporting quality of life near death. Sample has been reduced to 299 patients because of missing data. Analyses were repeated with missing data imputed to their mean values (n = 343), and the results were unchanged. Quality of life in the last week of life, possible scores 0 to 30. Whole sample: mean = 19.0, standard deviation = 7.9.

DISCUSSION

This study demonstrated that patients with advanced cancer whose spiritual needs are met by the medical team have more than three-fold greater odds of receiving hospice care at the EoL in comparison with those not supported. High religious coping patients receiving full support of their spiritual needs had near five-fold greater odds of receiving hospice care and more than five-fold decreased odds of receiving aggressive care at EoL as compared with those not supported. These associations were over and above established predictors of EoL care, such as race29,30 and EoL care preferences.31,32 Additionally, spiritual care was found to be associated with better patient QoL at the EoL. Near-death QoL scores were increased 28% on average among patients receiving either pastoral care services or spiritual support from the medical team in comparison with those receiving no spiritual care. The associations of spiritual care with patient QoL near death are notable given adjustment for multiple potential confounds, such as baseline QoL, the patient-physician relationship, and care received at EoL. To our knowledge, this is the first study demonstrating prospective associations of spiritual care with medical care and QoL near death, findings that highlight the relevance of existing national spiritual care guidelines.22,23

The significant associations of spiritual support from the medical team with receipt of hospice and, among high religious coping patients, with receipt of aggressive care are consistent with data supporting the role of spiritual matters in EoL decision making. Silvestri et al,20 in a study of factors important to the medical decision making of patients with advanced lung cancer, found that among seven factors ranked by patients (eg, chances of cure), patients' faith in God ranked second in importance only to their oncologists' treatment recommendations. Additionally, religiousness and religious coping have been shown to be associated with greater preference for12,34 and receipt of21 aggressive EoL care, associations that may in part reflect unresolved spiritual issues in religious patients. Spiritual support may facilitate patients' facing spiritual issues and finding spiritual peace at EoL, thereby creating more receptivity to a transition away from aggressive care. Furthermore, discussion regarding the role of R/S beliefs in medical decision making may help patients more fully recognize EoL care options that are consistent with their R/S beliefs. Interestingly, the association of spiritual support with EoL care was present for spiritual support from the medical team, but not for receipt of pastoral care services. Caregivers such as doctors and nurses are generally the individuals providing counsel regarding medical decision making. Their acknowledgment of the R/S components of illness may be of particular importance in helping patients face the spiritual issues most directly impacting their care decisions.

The association of spiritual care with patient QoL at the EoL is supported by studies demonstrating the importance of R/S to patients confronting advanced illness5,10-13 and by studies revealing better QoL among patients with increased spiritual well-being13,18 and among those receiving spiritual support.12,24,35 Furthermore, advanced illness has been shown to raise spiritual concerns for most patients14,15—a notable finding in light of the association of spiritual distress with QoL decrements.17,19 Finally, spiritual peace has been identified as a fundamental component of QoL near death.36 Steinhauser et al,36 in a random, national sample of 340 patients with advanced illness, found that of nine EoL attributes ranked in importance by patients, being at peace with God was, together with pain control, ranked highest. Spiritual care may allow patients to both express and explore the spiritual dimensions of approaching EoL, ultimately assisting them in attaining spiritual peace. The finding that spiritual care from chaplains and other members of the medical team were each associated with improved patient QoL near death reinforces their complementary roles in providing spiritual care.37 Chaplains play an essential role as professional providers of spiritual care; other medical providers also have a crucial role, including by performing spiritual assessments, recognizing spiritual needs, and making pastoral care referrals.

This study's limitations include the fact that, though models were adjusted for many potential confounds, there may be incomplete adjustment or unforeseen confounds not incorporated. Furthermore, the study's generalizability to those with noncancerous terminal illnesses and to those in other cultural contexts remains unclear. Studies on spiritual care in other populations are required. Patients assessed support of their spiritual needs without a stated definition of spiritual support, though the significant relationship of patient-rated spiritual support with receipt of pastoral care services suggests this measure is correlated with spiritual care provision. Finally, the study is limited by the undefined content and context of spiritual care performed by chaplains and other medical providers; further studies are required to more fully characterize its relationship to EoL outcomes.

In conclusion, spiritual care from the medical system seems to have important ramifications for patients at the EoL—helping them transition to hospice and improving their well-being near death. Furthermore, among high religious coping patients, spiritual support seems to reduce their risk of receiving aggressive interventions at EoL. However, despite national guidelines,22,23 spiritual care often remains absent for patients at the EoL.12 These findings underscore the need to educate medical caregivers in their appropriate roles in providing patient-centered spiritual care and the importance of integrating pastoral care into multidisciplinary medical teams.

Footnotes

Supported in part by the following grants to H.G.P.: Grant No. MH63892 from the National Institute of Mental Health, Grant No. CA 106370 from the National Cancer Institute, and a Fetzer Foundation grant. This research was also supported in part by an American Society of Clinical Oncology Young Investigator Award to T.A.B.

Presented in part at the 45th Annual Meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology, May 29-June 2, 2009, Orlando, FL.

Authors' disclosures of potential conflicts of interest and author contributions are found at the end of this article.

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The author(s) indicated no potential conflicts of interest.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: Tracy Anne Balboni, Mary Elizabeth Paulk, Michael J. Balboni, Andrea C. Phelps, Elizabeth Trice Loggers, Alexi A. Wright, Susan D. Block, Holly Gwen Prigerson

Financial support: Holly Gwen Prigerson

Administrative support: Mary Elizabeth Paulk, Holly Gwen Prigerson

Provision of study materials or patients: Mary Elizabeth Paulk

Collection and assembly of data: Mary Elizabeth Paulk

Data analysis and interpretation: Tracy Anne Balboni, Michael J. Balboni, Andrea C. Phelps, Elizabeth Trice Loggers, Alexi A. Wright, Susan D. Block, Eldrin F. Lewis, John R. Peteet, Holly Gwen Prigerson

Manuscript writing: Tracy Anne Balboni, Michael J. Balboni, Andrea C. Phelps, Elizabeth Trice Loggers, Alexi A. Wright, Susan D. Block, Eldrin F. Lewis, John R. Peteet, Holly Gwen Prigerson

Final approval of manuscript: Tracy Anne Balboni, Mary Elizabeth Paulk, Michael J. Balboni, Andrea C. Phelps, Elizabeth Trice Loggers, Alexi A. Wright, Susan D. Block, Eldrin F. Lewis, John R. Peteet, Holly Gwen Prigerson

REFERENCES

- 1.Reynolds MA. Hope in adults, ages 20-59, with advanced stage cancer. Palliat Support Care. 2008;6:259–264. doi: 10.1017/S1478951508000394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Saleh US, Brockopp DY. Hope among patients with cancer hospitalized for bone marrow transplantation: A phenomenologic study. Cancer Nurs. 2001;24:308–314. doi: 10.1097/00002820-200108000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fanos JH, Gelinas DF, Foster RS, et al. Hope in palliative care: From narcissism to self-transcendence in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J Palliat Med. 2008;11:470–475. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2007.0098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McClain CS, Rosenfeld B, Breitbart W. Effect of spiritual well-being on end-of-life despair in terminally-ill cancer patients. Lancet. 2003;361:1603–1607. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13310-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gall TL, Cornblat MW. Breast cancer survivors give voice: A qualitative analysis of spiritual factors in long-term adjustment. Psychooncology. 2002;11:524–535. doi: 10.1002/pon.613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Johnson SC, Spilka B. Coping with breast cancer: The role of clergy and faith. J Relig Health. 1991;30:21–33. doi: 10.1007/BF00986676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sodestrom K, Martinson IM. Patients' spiritual coping strategies: A study of nurse and patient perspective. Oncol Nurs Forum. 1987;14:41–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sulmasy DP. The Rebirth of the Clinic: An Introduction to Spirituality in Health Care. Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Koenig HG. Medicine, Religion, and Health: Where Science and Spirituality Meet. West Conshohocken, PA: Templeton Foundation Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Koenig HG. Religious attitudes and practices of hospitalized medically ill older adults. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 1998;13:213–224. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-1166(199804)13:4<213::aid-gps755>3.0.co;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Roberts JA, Brown D, Elkins T, et al. Factors influencing views of patients with gynecologic cancer about end-of-life decisions. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1997;176:166–172. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(97)80030-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Balboni TA, Vanderwerker LC, Block SD, et al. Religiousness and spiritual support among advanced cancer patients and associations with end-of-life treatment preferences and quality of life. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:555–560. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.07.9046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nelson CJ, Rosenfeld B, Breitbart W, et al. Spirituality, religion, and depression in the terminally ill. Psychosomatics. 2002;43:213–220. doi: 10.1176/appi.psy.43.3.213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Astrow AB, Wexler A, Texeira K, et al. Is failure to meet spiritual needs associated with cancer patients' perceptions of quality of care and their satisfaction with care? J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:5753–5757. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.12.4362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moadel A, Morgan C, Fatone A, et al. Seeking meaning and hope: Self-reported spiritual and existential needs among an ethnically-diverse cancer patient population. Psychooncology. 1999;8:378–385. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-1611(199909/10)8:5<378::aid-pon406>3.0.co;2-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hermann CP. The degree to which spiritual needs of patients near the end of life are met. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2007;34:70–78. doi: 10.1188/07.ONF.70-78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tarakeshwar N, Vanderwerker LC, Paulk E, et al. Religious coping is associated with the quality of life of patients with advanced cancer. J Palliat Med. 2006;9:646–657. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2006.9.646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brady MJ, Peterman AH, Fitchett G, et al. A case for including spirituality in quality of life measurement in oncology. Psychooncology. 1999;8:417–428. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-1611(199909/10)8:5<417::aid-pon398>3.0.co;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sherman AC, Simonton S, Latif U, et al. Religious struggle and religious comfort in response to illness: Health outcomes among stem cell transplant patients. J Behav Med. 2005;28:359–367. doi: 10.1007/s10865-005-9006-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Silvestri GA, Knittig S, Zoller JS, et al. Importance of faith on medical decisions regarding cancer care. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:1379–1382. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.08.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Phelps AC, Maciejewski PK, Nilsson M, et al. Religious coping and use of intensive life-prolonging care near death in patients with advanced cancer. JAMA. 2009;301:1140–1147. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Joint Commission. Spiritual Assessment. Oakbrook Terrace, IL: Joint Commission; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 23.National Consensus Project for Quality Palliative Care. Clinical Practice Guidelines for Quality Palliative Care. Pittsburgh, PA: National Consensus Project for Quality Palliative Care; 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kristeller JL, Rhodes M, Cripe LD, et al. Oncologist Assisted Spiritual Intervention Study (OASIS): Patient acceptability and initial evidence of effects. Int J Psychiatry Med. 2005;35:329–347. doi: 10.2190/8AE4-F01C-60M0-85C8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pargament KI, Koenig HG, Perez LM. The many methods of religious coping: Development and initial validation of the RCOPE. J Clin Psychol. 2000;56:519–543. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4679(200004)56:4<519::aid-jclp6>3.0.co;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cohen SR, Mount BM, Bruera E, et al. Validity of the McGill Quality of Life Questionnaire in the palliative care setting: A multi-centre Canadian study demonstrating the importance of the existential domain. Palliat Med. 1997;11:3–20. doi: 10.1177/026921639701100102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cohen SR, Mount BM, Strobel MG, et al. The McGill Quality of Life Questionnaire: A measure of quality of life appropriate for people with advanced disease—A preliminary study of validity and acceptability. Palliat Med. 1995;9:207–219. doi: 10.1177/026921639500900306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Earle CC, Neville BA, Landrum MB, et al. Trends in the aggressiveness of cancer care near the end of life. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:315–321. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.08.136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Smith AK, Earle CC, McCarthy EP. Racial and ethnic differences in end-of-life care in fee-for-service Medicare beneficiaries with advanced cancer. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57:153–158. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.02081.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Smith AK, McCarthy EP, Paulk E, et al. Racial and ethnic differences in advance care planning among patients with cancer: Impact of terminal illness acknowledgment, religiousness, and treatment preferences. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:4131–4137. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.8452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wright AA, Zhang B, Ray A, et al. Associations between end-of-life discussions, patient mental health, medical care near death, and caregiver bereavement adjustment. JAMA. 2008;300:1665–1673. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.14.1665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cosgriff JA, Pisani M, Bradley EH, et al. The association between treatment preferences and trajectories of care at the end-of-life. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22:1566–1571. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0362-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Prigerson HG. Socialization to dying: Social determinants of death acknowledgement and treatment among terminally ill geriatric patients. J Health Soc Behav. 1992;33:378–395. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.True G, Phipps EJ, Braitman LE, et al. Treatment preferences and advance care planning at end of life: The role of ethnicity and spiritual coping in cancer patients. Ann Behav Med. 2005;30:174–179. doi: 10.1207/s15324796abm3002_10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rummans TA, Clark MM, Sloan JA, et al. Impacting quality of life for patients with advanced cancer with a structured multidisciplinary intervention: A randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:635–642. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Steinhauser KE, Christakis NA, Clipp EC, et al. Factors considered important at the end of life by patients, family, physicians, and other care providers. JAMA. 2000;284:2476–2482. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.19.2476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Puchalski CM, Lunsford B, Harris MH, et al. Interdisciplinary spiritual care for seriously ill and dying patients: A collaborative model. Cancer J. 2006;12:398–416. doi: 10.1097/00130404-200609000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]