Abstract

Non-Hodgkin's lymphoma very rarely involves the esophagus, occurring in less than 1% of patients with gastrointestinal lymphoma. A few cases of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma of the esophagus have been reported in the English literature. To our knowledge, there has been no report of MALT lymphoma of the esophagus coexistent with bronchus-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma (BALT) of the lung. This report details the radiological and clinical findings of this first concurrent case.

Keywords: Esophagus, MALT lymphoma, lung, BALT lymphoma

INTRODUCTION

Mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphomas arise not only in the gut but also in the lung (bronchus-associated lymphoid tissue: BALT), thyroid (derived from the primitive foregut), salivary glands, skin, conjunctiva, soft tissue, dura, orbit, and liver.1 Within the gastrointestinal tract, the stomach is the most common site of MALT lymphoma, although these tumors have been reported throughout the intestine.1 The esophagus is the least common site of gastrointestinal involvement of lymphoma, accounting for only about 1% of cases.2 Both non-Hodgkin's and, less commonly, Hodgkin's lymphoma may involve the esophagus. A few cases of MALT lymphoma of the esophagus have been reported in the English literature. To our knowledge, there is no report of MALT lymphoma of the esophagus coexistent with BALT lymphoma of the lung concurrently in the same patient.

CASE REPORT

A 65-year-old man was admitted to the hospital for evaluation of swallowing difficulty, which had progressively worsened over the last year. Swallowing difficulty was the only complaint of the patient, and the physical examination and laboratory findings were normal. No palpable lymph nodes were detected in the neck or trunk.

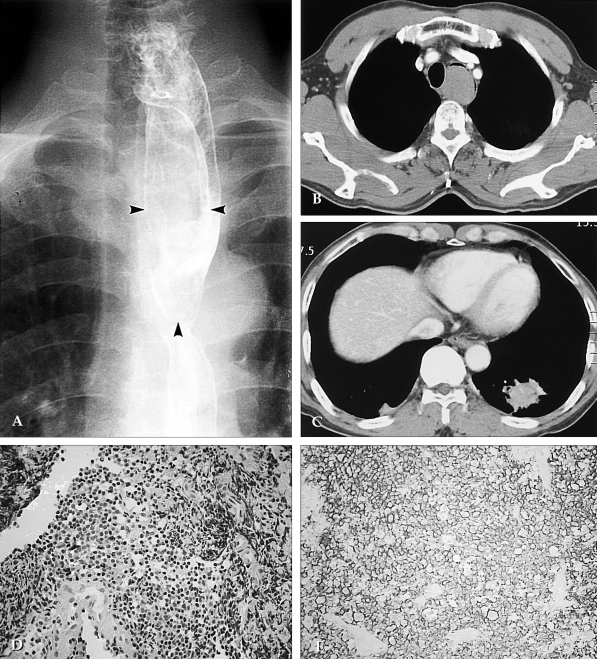

Endoscopic examination revealed a large submucosal mass without ulceration on the overlying mucosa in the upper thoracic esophagus. Double-contrast esophagography (Fig. 1A) showed a well demarcated submucosal mass of 10×3×3 cm in size in the upper thoracic esophagus with intact mucosa. Upon chest CT scan, a well-circumscribed homogeneous intramural mass was seen in the upper thoracic esophagus (Fig. 1B). Additionally, an ill-defined mass, about 4×3 cm in size, with internal air bronchograms, was also seen in the lateral basal segment of the lower lobe of the left lung (Fig. 1C). Several slightly enlarged paraesophageal lymph nodes were seen around the esophageal tumor.

Fig. 1.

A 65-year-old man with esophageal MALT lymphoma and concurrent BALT lymphoma of the lung. (A) A barium swallow study revealed a well-demarcated submucosal mass (arrowheads) of 10×3×3 cm in size in the upper thoracic esophagus without surface ulceration or a stalk. (B) A chest CT scan showed a sharply demarcated homogeneous mass within the esophagus. Note the eccentric location, crescent-shape esophageal lumen (compressed by the mass), and the laterally displaced trachea. (C) A chest CT scan of the lower lung showed an ill-defined 4×3 cm size mass in the lateral basal segment of the lower lobe of the left lung. A small focal subpleural consolidation was also seen in the right lower lung; however, this consolidation was not seen in the follow-up CT scan taken before chemotherapy. (D) Upon histologic examination, dense atypical lymphocytic infiltrations were noted in the submucosa of esophagus. The tumor cells showed dark nuclei with abundant clear cytoplasm and occasional Dutcher bodies (H & E stain, ×200). (E) Upon immunohistochemical stain, the esophageal tumor cells showed extensive strong immunoreactivity for the B-cell marker and L26, and monoclonal reactivity for kappa light chain immunoglobulin along the cytoplasmic membranes (×200).

Following endoscopic biopsy, a histologic examination of the esophageal tumor revealed homogenously dense atypical lymphocytic infiltrations in the submucosa of the esophagus, while the mucosa itself was intact. The atypical lymphocytes were small to medium in size with dark nuclei and abundant, clear cytoplasm. Partial differentiation of plasma cells was observed with occasional Dutcher bodies (Fig. 1D). Upon immunohistochemical staining, the lymphocytes showed extensively homogenous immunoreactivity for the B-cell markers L26 and CD79a, no staining for the T-cell markers CD3 and UCHL-1, and appeared monoclonal for kappa light chain immunoglobulin (Fig. 1E). The results of the immunohistochemical stain for other B-cell lymphoma subclassification markers (cyclin D-1, CD10, CD5, CD23, and bcl-2) were negative. This ruled out the possibilities of mantle cell lymphoma, follicular lymphoma, and small lymphocytic lymphoma.

A transbronchial lung biopsy of the mass in the lower left lung revealed the same histological and immunohistochemical findings as those of the esophageal submucosal tumor, indicating low-grade lymphoma of the BALT. A bone marrow biopsy revealed no lymphoma involvement. There was no splenic or hepatic involvement, and the patient had a normal white cell count. Lymphoma involvement was not found in the other gastrointestinal tract organs by endoscopy, small bowel follow-through barium study, or colonoscopy. There was no lymphadenopathy in the neck, abdomen or pelvic cavity by CT scan.

The patient was treated with a total of 6 courses of chemotherapy with cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine and prednisolone. Both the esophageal and lung masses were markedly reduced in size with improvement of swallowing difficulty after chemotherapy for 6 months. He has been living well for 2 years after the initial treatment.

DISCUSSION

The mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) is a specially adapted component of the immune system that has evolved to protect the freely permeable surface of the gastrointestinal tract and other mucosa that are directly exposed to the external environment.3 In healthily individuals, the organized MALT is found throughout the small and large intestines in the form of Peyer's patches, intraepithelial lymphocytes, and lymphoid cells in the lamina propria.4,5 However, there is no known MALT in the esophageal mucosa or submucosa except in cases of Barrett's esophagus (5%).6

In the case described here, several paraesophageal lymph nodes larger than 5mm in diameter were detected, but the direct involvement of the esophageal wall by the paraesophageal lymph nodes was not histologically proven. Therefore, we cannot conclusively determine the relationship between MALT lymphoma of the esophagus and BALT lymphoma of the lung in this case, even though both lesions showed identical histology. Nevertheless, the possibility of synchronous primary tumors in both esophagus and lung should be considered as there is no known direct lymphatic or hematogenous route between the lung and the esophageal submucosal layer.

MALT lymphoma usually develops from acquired MALT rather than the primary organized MALT.5 This acquired MALT tends to appear in patients through chronic antigenic stimulation triggered by persistent infection and/or autoimmune processes.7 A causative relationship between Helicobacter pylori infection and low-grade B-cell lymphoma arising from MALT involving the stomach is well known.4 However, the patient in our case was H. pylori negative.

All four cases of previously reported esophageal MALT5,8-10 showed a submucosal tumor-like lesion with a smooth, elongated protruded mass. Two5,8 of these were located in the mid and distal esophagus and the remaining two9,10 were located in the thoracic esophagus. In the first case,8 Ga-67 scintigraphy revealed the characteristic intense accumulation in the esophageal wall. The second case9 showed two elevated submucosal tumor-like lesions measuring 1cm longitudinally, and the third case5 showed a well-defined, poorly enhanced mass in the distal esophagus by dynamic chest CT scan. In the last case,10 fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography revealed an abnormal accumulation corresponding to the submucosal tumor, which was not found on barium esophagography. The case described in this report also showed a submucosal mass with a well-defined elongated shape by barium esophagography and well-circumscribed homogeneous mass by chest CT scan.

Multi-organ involvement has been found in almost a quarter of patients with MALT lymphoma.7 Because multi-organ MALT lymphomas rarely achieve complete remission by treatment with combination chemotherapy or irradiation, MALT lymphomatous lesions should be evaluated carefully, especially in the large intestine.11 Extragastrointestinal MALT lymphoma occurs simultaneously at different anatomic sites more frequently than MALT lymphoma involving the gastrointestinal tract.7

Bronchus-associated lymphoid tissue (BALT) in the lung is thought to develop after exposure to various infections and unknown antigens and is responsible for the immunological response initiated by antigens at the bronchial surface.14 Lymphoid follicles organized from resident immune cells in the bronchi are present within peribronchial lymph nodes or inside the bronchial mucosa within so-called BALT,12 however, BALT is not considered to be constitutively present or to play a central role in the pulmonary immune system of healthy adults.13

Up to 70% of primary lymphomas of the lung are BALT lymphomas arising from the BALT in the lung. The most common radiographic abnormalities of BALT lymphoma of the lung consist of solitary or multiple pulmonary nodules or multiple areas of patchy consolidation with air-bronchograms. 14 Other findings include diffuse bilateral air space consolidation, segmental or lobar atelectasis, and a mosaic pattern of inhomogeneous attenuation.14-18 In BALT lymphomas of the lung, hilar and mediastinal lymphadenopathies are very rare, unlike secondary pulmonary lymphomas in which these are prominent features.

In summary, the patient described had MALT lymphoma of the esophagus which showed a well-defined elongated submucosal tumor and concurrent BALT lymphoma of the lung, which showed nodular or patchy consolidation with internal air bronchograms.

References

- 1.John DV, Jr, Levin B, Salem P. Intestinal lymphomas, including immunoproliferative small intestinal disease. In: Feldman M, Scharschmidt BF, Sleisenger MN, editors. Sleisenger & Fordtran's Gastrointestinal and liver disease. Philadelphia: Saunders; 1988. pp. 1844–1857. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Oğuzkurt L, Karabulut N, Çakmakci E, Besim A. Primary non-Hodgkin's lymphoma of the esophagus. Abdom Imaging. 1997;22:8–10. doi: 10.1007/s002619900129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Isaacson PG. Gastrointestinal lymphomas and lymphoid hyperplasias. In: Knowles DM, editor. Neoplastic hematopathology. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2001. pp. 1235–1261. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lee HJ, Han JK, Kim TK, Kim YH, Kim AY, Kim KW, et al. Primary colorectal lymphoma: spectrum of imaging findings with pathologic correlation. Eur Radiol. 2002;12:2242–2249. doi: 10.1007/s00330-002-1307-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shim CS, Lee JS, Kim JO, Cho JY, Lee MS, Jin SY, et al. A case of primary esophageal B-cell lymphoma of MALT type, Presenting as a submucosal tumor. J Korean Med Sci. 2003;18:120–124. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2003.18.1.120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weston AP, Cherian R, Horvat RT, Lawrinenko V, Dixon A, McGregor D. Mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) in Barrett's esophagus: prospective evaluation and association with gastric MALT, MALT lymphoma, and Helicobacter pylori. Am J Gastroenterol. 1997;92:800–804. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Raderer M, Vorbeck F, Formanek M, Osterreicher C, Valencak J, Penz M, et al. Importance of extensive staging in patients with mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT)-type lymphoma. Br J Cancer. 2000;83:454–457. doi: 10.1054/bjoc.2000.1308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nishiyama Y, Yamamoto Y, Ono Y, Satoh K, Ohkawa M, Yamauchi A, et al. Visualization of esophageal non-Hodgkin's lymphoma with Ga-67 scintigraphy. Ann Nucl Med. 1999;13:419–421. doi: 10.1007/BF03164937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hosaka S, Nakamura N, Akamatsu T, Fujisawa T, Ogiwara Y, Kiyosawa K, et al. A case of primary low grade mucosa associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma of the oesophagus. Gut. 2002;51:281–284. doi: 10.1136/gut.51.2.281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kitamoto Y, Hasegawa M, Ishikawa H, Saito J, Yamakawa M, Kojima M, et al. Mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma of the esophagus: A case report. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2003;36:414–416. doi: 10.1097/00004836-200305000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yoshino T, Ichimura K, Mannami T, Takase S, Ohara N, Okada H, et al. Multiple organ mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphomas often involve the intestine. Cancer. 2001;91:346–353. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20010115)91:2<346::aid-cncr1008>3.0.co;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sminia T, van der Brugge-Gamelkoorn GJ, Jeurissen SH. Structure and function of bronchus-associated lymphoid tissue (BALT) Crit Rev Immunol. 1989;9:119–150. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pabst R. Is BALT a major component of the human lung immune system? Immunol Today. 1992;13:119–122. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(92)90106-H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McCulloch GL, Sinnatamby R, Stewart S, Goddard M, Flower CDR. High-resolution computed tomographic appearance of MALToma of the lung. Eur Radiol. 1998;8:1669–1673. doi: 10.1007/s003300050609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee DK, Im JG, Lee KS, Lee JS, Seo JB, Goo JM, et al. B-cell lymphoma of bronchus-associated lymphoid tissue (BALT): CT features in 10 patients. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2000;24:30–34. doi: 10.1097/00004728-200001000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee IJ, Kim SH, Koo SH, Kim HB, Hwang DH, Lee KS, et al. Bronchus-associated lymphoid tissue (BALT) lymphoma of the lung showing mosaic pattern of inhomogeneous attenuation on thin-section CT: A case report. Korean J Radiol. 2000;1:159–161. doi: 10.3348/kjr.2000.1.3.159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Takamori M, Noma S, Kobashi Y, Inoue T, Gohma I, Mino M, et al. CT findings of BALTOMA. Radiat Med. 1999;17:349–354. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Varoczy L, Gergely L, Illes A. Diagnostics and treatment of pulmonary BALT lymphoma: a report on four cases. Ann Hematol. 2003;82:363–366. doi: 10.1007/s00277-003-0658-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]