Abstract

Drosophila translational elongation factor-1γ (EF1γ) interacts in the yeast two-hybrid system with DOA, the LAMMER protein kinase of Drosophila. Analysis of mutant EF1γ alleles reveals that the locus encodes a structurally conserved protein essential for both organismal and cellular survival. Although no genetic interactions were detected in combinations with mutations in EF1α, an EF1γ allele enhanced mutant phenotypes of Doa alleles. A predicted LAMMER kinase phosphorylation site conserved near the C terminus of all EF1γ orthologs is a phosphorylation site in vitro for both Drosophila DOA and tobacco PK12 LAMMER kinases. EF1γ protein derived from Doa mutant flies migrates with altered mobility on SDS gels, consistent with it being an in vivo substrate of DOA kinase. However, the aberrant mobility appears to be due to a secondary protein modification, since the mobility of EF1γ protein obtained from wild-type Drosophila is unaltered following treatment with several nonspecific phosphatases. Expression of a construct expressing a serine-to-alanine substitution in the LAMMER kinase phosphorylation site into the fly germline rescued null EF1γ alleles but at reduced efficiency compared to a wild-type construct. Our data suggest that EF1γ functions in vital cellular processes in addition to translational elongation and is a LAMMER kinase substrate in vivo.

THE Darkener of apricot (Doa) locus encodes the Drosophila member of the LAMMER/Clk protein kinase family. Doa is essential for embryonic and adult cuticular development (Yun et al. 1994), and strong mutant alleles are cell lethal in both the soma and germline, demonstrating a vital role for the kinase in all cell types (Yun et al. 2000). LAMMER protein kinases are best known for their roles in the regulation of alternative splicing via the phosphorylation of SR proteins (Colwill et al. 1996a,b; Nayler et al. 1997; Savaldi-Goldstein et al. 2000). In Drosophila, a cascade of regulated alternative splicing determines somatic sexual determination (Lopez 1998). Consistent with a role for LAMMER kinases in the regulation of alternative splicing, Doa alleles induce male-specific development and splicing of dsx in chromosomally female individuals, as well as hypophosphorylation and delocalization of some SR and SR-like proteins (Du et al. 1998).

While primarily recognized for their role in the regulation of splicing, LAMMER kinases are also likely to be involved in mediating one or more signaling cascades. For example, in tobacco, the LAMMER kinase PK12 is post-transcriptionally and post-translationally induced in response to the hormone ethylene (Sessa et al. 1996). In mammalian cell cultures, CLK1 and -2 phosphorylate and activate PTP1b, a cytoplasmic tyrosine phosphatase involved in insulin signaling (Moeslein et al. 1999).

Results in cultured mammalian cells initially described LAMMER kinases as exclusively nuclear (Colwill et al. 1996b; Nayler et al. 1997, 1998), but subsequent studies have shown that the mammalian CLK kinases are also cytoplasmic (Moeslein et al. 1999; Menegay et al. 2000; Prasad and Manley 2003), suggesting the possibility of shuttling between the two intracellular compartments. At least six Doa isoforms are produced via alternative promoter utilization (Kpebe and Rabinow 2008a), of which at least three possess differentiable functions (Kpebe and Rabinow 2008b). Of these isoforms, at least one is nuclear and another cytoplasmic (Yun et al. 2000).

In eukaryotes, the soluble elongation factors EF1 and EF2, analogous to the bacterial elongation factors EF-Tu/Ts and EF-G, are required for translational elongation. EF1 is composed of three or four subunits, EF1α, -β, -γ, and -δ in higher eukaryotes.

EF1α is an abundant protein, the majority of which is isolated as a monomer (Dasmahapatra et al. 1981), but the protein is also found associated with EF1β, -γ, and -δ subunits in a high molecular weight complex (Carvalho et al. 1984). The α subunit of EF1 binds aminoacyl-tRNA in a GTP-dependent manner. This ternary complex then binds to the ribosome (reviewed in Riis et al. 1990). GTP is hydrolyzed to GDP after the cognate aminoacyl-tRNA is bound at the ribosomal A site. The GDP remains tightly bound to EF1α following this reaction. EF1β stimulates nucleotide exchange to regenerate EF1α-GTP for the next elongation cycle (Slobin and Moller 1978). In Drosophila, recessive lethal alleles of EF1α exist, but loss-of-function mutations in EF1β are not described.

Changes to the nomenclature of eukaryotic translation elongation factors were proposed, whereby the EF1 subunits have been renamed (Merrick and Nyborg 2000; Le Sourd et al. 2006). EF1γ for example, has been renamed eEF1Bγ. However, for the purposes of simplicity and consistency with the terminology used in FlyBase, we use the older nomenclature (EF1γ) in this article.

Although suggested to stimulate the nucleotide exchange activity of EF1β (Janssen and Moller 1988), there is little evidence of a function for EF1γ in translation. EF1γ is completely dispensable for translation in vitro, and its absence fails to affect rates of translational elongation. Indeed, the identification of the protein as an “elongation factor” is due to the fact that it co-isolates with EF1β.

While a function of EF1γ in translation thus remains largely conjectural, other observations suggest alternative and perhaps multiple roles for the protein (reviewed in Ejiri 2002). For example, the EF1γ of Artemia salina co-immunoprecipitates with tubulin (Janssen and Moller 1988). Drosophila EF1γ (CG11901), was also identified in a screen for microtubule-binding proteins, supporting this observation (Hughes et al. 2008). It might be noted that DOA kinase was also identified in the same screen. Interactions of EF1γ with keratin have also been observed, and this association is the single report suggesting effects of EF1γ on rates of protein translation (Kim et al. 2007). Human EF1γ was also described as specifically binding to the 3′-UTR of vimentin mRNA (Al-Maghrebi et al. 2002). Intriguingly, EF1γ was recently identified in a proteomic screen as a member of the pre-mRNA 3′ end cleavage complex (Shi et al. 2009), reinforcing the finding of RNA-binding properties for the protein and suggesting roles for it in functions in addition to translational elongation.

One phenotype involving EF1γ is constitutive resistance to oxidative stress in yeast mutants, although without detectable alterations to translation (Olarewaju et al. 2004). The primary sequence and structure of the N terminus of the yeast EF1γ encoded by the TEF3 locus resembles the θ class of human glutathione S-transferase (Jeppesen et al. 2003), and this region is conserved among EF1γ orthologs. EF1 also interacts with the 26S proteasome in Xenopus oocytes, and the interaction is stabilized by phosphorylation (Tokumoto et al. 2003). A possible link between human disease and EF1γ is suggested by the fact that the protein is overexpressed in several cancers (Lew et al. 1992; Mimori et al. 1995, 1996; Mathur et al. 1998), although the effects, if any, of this overexpression remain unknown.

EF1γ is transcriptionally induced at the onset of autophagy in the Drosophila salivary gland (Gorski et al. 2003), similarly to Doa (Lee et al. 2003), suggesting roles for both gene products and the possibility of their interaction. EF1γ was also identified in an RNAi-based screen for genes required for the innate immune response in S2 cells (Foley and O'Farrell 2004), as well as in a proteomics approach for proteins associated with the Drosophila phagosome (Stuart et al. 2007).

Here we report the first genetic characterization of Drosophila EF1γ in a higher organism, and its in vitro and in vivo interactions with Doa. EF1γ activity is required for the viability of both whole animals and individual cells. Recessive lethality occurs during early larval development, consistent with an extensive maternal contribution of the RNA and protein to the embryo. One transcript isoform is also transcriptionally induced by the ecdysone-dependent transcription factor E93 during salivary gland autophagy. EF1γ protein is found in pupal nuclei, inconsistent with a role exclusively in translational elongation. However, its overexpression reveals almost no aberrant phenotypes. Drosophila EF1γ is phosphorylated in vitro by DOA and tobacco PK12 LAMMER protein kinases on a site that is strictly conserved in all orthologs, and aberrant migration of the protein obtained from Doa mutants suggests that it may also be an in vivo substrate of the kinase, although altered migration appears to be due to a secondary post-translational modification. Amino acid replacement of the phosphorylated serine and insertion of the construct into the Drosophila germline shows that although the mutated protein is capable of rescuing loss-of-function alleles, rescue is noticeably less efficient in females.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Drosophila culture, mutagenesis, and crosses:

Drosophila stocks and crosses were maintained on standard cornmeal agar medium. Crosses were performed at 25°, except as noted. Crosses to generate heteroallelic Doa individuals were previously described (Rabinow et al. 1993; Kpebe and Rabinow 2008b). GE29510, a P-element insertion at the 5′ end of EF1γ (CG11901), was purchased from Genexel, and its insertion site verified. Additional alleles were recovered from imprecise excisions of the initial insertion. DrMio/TMS, P{ry[+t7.2] Δ2-3} males were crossed with yw67c23; P[w+ EF1γ] GE29510/TM3 females; F1 Δ2-3/P[w+ EF1γ] GE29510 males were crossed with yw67c23; TM2/TM3 females. Stocks derived from F2 white-eyed males were screened for complementation of deficiency Df(3R)Exel6212 (99A1-99A5), which removes EF1γ. Twenty-eight reversions of 104 recovered were lethal. Four of these were imprecise excisions generating deficiencies of the locus or retaining only part of the initial P-element: 3 were hypomorphs and 1, a null allele. Of 5 chromosomes viable over Df(3R)Exel6212 analyzed, 4 were precise excisions, while the fifth retained 43 bp of the initial element. Somatic clones were generated with the FLP/FRT system (Xu and Rubin 1993), using the FRT at 82B. Recombinants between Doa and EF1γ, which are separated by only ∼297 kb, were obtained by crossing a Pr DoaHD chromosome in a w− background to the w+-marked EF1γGE29510. Heterozygous females were crossed with a double-balanced stock and F1 w+; Pr males were selected. These were then crossed individually to w−; DoaHD/TM3 females. Crosses yielding only flies carrying a third-chromosome balancer were selected and complementation tested for the presence of the HD allele. Approximately 6300 total chromosomes were screened, 90 Pr w+ chromosomes analyzed, and 4 identified as recombinants between Doa and EF1γ, yielding a map distance of ∼0.06 cM between the two loci.

Transgenic lines expressing EF1γ:

cDNAs encoding wild-type EF1γ and a Ser294Ala substitution were subcloned into pUAS-T for P-element mediated transformation. Embryos were injected by BestGene. At least two lines were analyzed for each construct for each phenotype. Two lines producing interfering RNA (RNAi) specific for EF1γ were obtained from the National Institute of Genetics (NIG), Genetic Strains Research Center. Crosses using GAL4-directed expression were performed at 29° to enhance phenotypes.

Immunocytochemistry and in situ hybridization:

In situ hybridization to whole embryos was carried out as described (Tautz and Pfeifle 1989). Staging of embryos was as per Campos-Ortega and Hartenstein (1997). Immunocytochemical staining of embryos was performed as described (Ashburner 1989), using rat anti-Drosophila EF1γ at a dilution of 1:1000.

Molecular Biology:

Molecular biological methods were performed according to standard techniques (Ausubel et al. 1989). RNA preparations, Northern transfers, and probe preparation were performed as described (Kpebe and Rabinow 2008a). Loading controls were performed by rehybridizing the transfers with a probe for rp49 (O'Connell and Rosbash 1984). RT–PCR experiments utilized the following primers: 2063F, GCTGAATTTGCCACTATATCGT; 2006F, TGTTTCCGTCCCTTCTCTTC; and 2370R, TCTCGCCGAACTTGAAGTTG.

Site-specific mutagenesis of Ser294 to Ala in EF1γ cDNAs (nucleotide 25047082 on chromosome 3R in the EF1γ locus, made use of the Quick Change kit (Stratagene), and the oligonucleotide 5′-TCC AAG CGC GTG TAC GCC AAT GAG GAC GAG GCC-3′, where the underlined “G” was substituted for the “T” in the wild-type sequence. Sequenced PCR products were inserted into pGEX 2T for protein expression and into pUAS-T for Drosophila germline transformation. Computerized searches of sequence databases and alignments were generated using GCG software.

Yeast strains and methods and plasmid constructions:

The yeast two-hybrid plasmids pAS1, pACT, and pACTII were gifts from S. Elledge (Durfee et al. 1993), as was a generous gift of an unpublished Drosophila third instar cDNA library. cDNA inserts were cloned at the XhoI site of the vector. False positive control and murine Clk1 fusion plasmids were gifts of K. Colwill (Colwill et al. 1996b). The clones used to eliminate false positive interactions included fusions with the GAL4 DNA-binding domain in pAS1 and p53, lamin, and the CDK2 and SNF1 kinases. The yeast strains were Y153 (Staudinger et al. 1993) and pJ69-4A (James et al. 1996), a gift from R. Lahue. Lithium acetate transformants were selected on Leu− Trp− medium, single colonies selected, and streaked onto selective (Leu− Trp− His−) medium for analysis. Many yeast two-hybrid and kinase-expression plasmids used in these studies were described previously (Du et al. 1998; Nikolakaki et al. 2002). Those generated here were:

pACT: EF1γ−Ctm (C-terminal) was the original two-hybrid cDNA clone encoding the C-terminal domain of Drosophila EF1γ interacting with DOA kinase.

pAS1CYH2: EF1γ−Ctm, the 800-bp XhoI fragment encoding the C-terminal domain of Drosophila EF1γ in pACT was digested with SalI, isolated, and religated into pAS1CYH2 digested with SalI.

pAS1CYH2: EF1γ−FL (full-length), the 1.7-kb cDNA insert of BDGP EST clone LD07046 was excised from its original vector (pBluescript SK+) via digestion with NcoI and XhoI, and cloned into NcoI/SalI cut pAS1CYH2.

pAS1CYH2: TaqIΔ, digestion of LD07046 with TaqI and NcoI yielded a 0.7-kb fragment encoding the 5′ end of the cDNA, which was cloned into NcoI/SmaI double-digested pAS1CYH2.

pAS1CYH2: PstIΔ, PstI digestion of pAS1CYH2: EF1γ−FL removed a 1.3-kb PstI/PstI internal fragment of the cDNA (see map, Figure 1), and the remaining DNA was religated on itself, leaving a 0.4-kb fragment encoding the N-terminal-most fragment of EF1γ.

Figure 1.—

Drosophila EF1γ interacts with DOA kinase in the yeast two-hybrid system. (A) Left: a Leu− Trp− plate demonstrates growth of the streaked double-transformant colonies under nonselective conditions; right: a duplicate Leu− Trp− His− plate, revealing protein–protein interactions based upon His+ prototrophy. Streaking of the two plates was performed in parallel. The indicated kinases were expressed from the pACTII vector, and the EF1γ proteins were expressed from the pAS1 vector. The initial screen was performed with DOA kinase expressed in pAS1 and the initial EF1γ–C-terminal domain-encoding clone was recovered in pACT (data not shown). Similar results were obtained in expression of EF1γ–Ctm, DOA and hCLK2 from reciprocal plasmids (data not shown). Ctm, C-terminal domain; FL, full length. (1) pAS1: EF1γ–Ctm; (2) pAS1: EF1γ–FL; (3) pAS1: EF1γ−TaqI; and (4) pAS1: EF1γ−PstI. (B) A schematic representation of the EF1γ cDNA constructs screened for two-hybrid interactions in A. The C-terminal clone was the initial isolate; the full-length clone is BDGP EST LD07046. The open reading frame is contained in the diagonally slashed box.

Immunoblot analysis verified that constructs containing full-length DOA, hCLK2, the N terminus of DOA, and the Drosophila EF1γ constructs were stably expressed as GAL4 activation-domain protein fusions.

Protein analysis:

Full-length and C-terminal domains of Drosophila EF1γ proteins were expressed and affinity purified as fusions with the glutathione-S-transferase protein fusion vector pGEX2T (Pharmacia) and the maltose-binding protein vector pMalC2 (New England Biolabs), respectively. The junctions of the recombinant plasmids were sequenced to verify in-frame translation of the EF1γ moiety. Thrombin cleavage of the recombinant GST–EF1γ fusion proteins followed the manufacturer's conditions. The expression and purification of recombinant DOA kinase catalytic domain and in vitro phosphorylation reactions were previously described (Lee et al. 1996; Du et al. 1998; Nikolakaki et al. 2002). Lambda and CIP phosphatases were used according to the manufacturer's instructions (NEB). Protocols for use of potato acid phosphatase (Sigma, type III) were previously described (Papavassiliou and Bohmann 1992; Du et al. 1998).

Antibodies against the full-length GST–EF1γ fusion protein were produced in both chickens and rats (Eurogentec). Preimmune sera and yolk preparations (IgY) did not detect reacting material on immunoblots of Drosophila proteins or recombinant EF1γ (not shown). Anti-EF1γ from either source was used at 1:1000 on immunotransfers and for immunocytochemistry.

SDS gel electrophoresis, protein transfers, and immunoblots were performed as described (Ausubel et al. 1989), using an 8% separating gel. Separated proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose via semi-dry transfer, blots were blocked in 5% nonfat milk, and probed with rat anti-EF1γ antibody SE62 (1:1000) and anti-rat HRP-conjugated antibody at 1:4000. ECL chemiluminescence (Amersham) was used for detection. Protein loading was controlled with anti-α-tubulin monoclonal antibody DM1A (Sigma).

Immunohistochemical staining of embryos was performed as described (Ashburner 1989). Crude anti-EF1γ serum was used at dilutions 1:1000. Preimmune serum was used as control. For DAB staining, tissues were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, and the VECTASTAIN Elite ABC kit was used. After blocking at 37° in PBT and 1% normal rabbit serum for 1 hr, embryos were incubated with diluted primary antibodies and then 1:200 diluted biotinylated anti-rat serum at 37° for 1 hr. Embryos were then incubated in ABC reagent followed by washing and staining with 0.1% DAB and 0.02% hydrogen peroxide. For immunofluorescence, tissues were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, 1.5% glutaraldehyde in PBS, permeabilized with 0.3% Triton X-100 in PBS, and blocked with 5% normal chicken serum in PBT. After washing, tissues were incubated in 1:2000 diluted primary antibodies and 1:2000 diluted Alexa594-conjugated chicken anti-rat secondary antibody for 2 hr and washed three to four times with PBS-Triton. Tissues were mounted in Mowiol. Images were acquired on a Zeiss LSM-410 microscope.

Drosophila protein preparations:

Embryos 0- to 24 hr old, first and third instar larvae, 0- to 24-hr-old pupae, and 0- to 24-hr-old adults were collected, washed in PBS, and homogenized in TBS (0.1 m NaCl, 20mm Tris pH 7.4), containing 0.2 mm PMSF, 1 μg/ml leupeptin and 0.2 μg/ml pepstatin A. Nuclear extracts from 0- to 24-hr-old pupae were prepared according to Dorsett (1990).

Bacterial strains, infections, and survival analysis:

Microbial septic injuries were performed as described (Romeo and Lemaitre 2008), by pricking adult flies under the wing in the lateral part of the thorax with a thin needle previously dipped into a concentrated (OD600) culture of Erwinia carotovora subsp. carotovora 15, a gift from F. Leulier. Three parallel vials with 20 flies in each were established for each genotype tested for survival. The flies were cultured at 29° and examined at different time points to monitor survival after septic injury. Infected flies were transferred to fresh vials daily.

β-galactosidase assays:

Forty adults of the same age and sex were homogenized in 200 μl of Z buffer (0.01 m KCl; 0.06 m Na2HPO4; 0.04 m NaH2PO4; 0.001 m MgSO4; 0.05 m β-mercaptoethanol), to which an additional 800 μl of buffer was added. Following vortexing, the lysate was cleared by centrifugation, to which 20 μl 0.1% SDS was added to triplicate samples of 200 μl, 700 μl of ONPG solution (1 mg/ml in Z buffer), preheated to 30°, was added. Reactions were stopped by the addition of 500 μl 1 m Na2CO3. Following centrifugation, ODs were read at 420 nm.

RESULTS

DOA kinase interacts with the C terminus of Drosophila EF1γ:

We screened ∼106 transformants of a Drosophila third instar cDNA library kindly provided by S. Elledge, in a yeast two-hybrid assay to identify proteins interacting with DOA kinase, using a near-full length cDNA clone encoding the 55 kDa DOA isoform (Yun et al. 2000; Kpebe and Rabinow 2008a,b). Among the colonies displaying histidine prototrophy (Figure 1A) was a clone encoding the C-terminal portion of Drosophila translational elongation factor 1γ (EF1γ; CG11901; 99A1-6). This clone expressed β-galactosidase at high levels, did not autoactivate transcription and did not interact with nonspecific GAL4–DNA binding domain fusion proteins.

The initial cDNA included a poly(A) tail, identifying the 3′ end of the transcript. Screening of a pupal cDNA library isolated a near-full length EF1γ cDNA almost completely overlapping the initial C-terminal clone, but lacking a poly(A) tail. Sequences of the initial clones were aligned and submitted to GenBank (accession no. AF148813). EST clone LD07046 encoding the full-length open reading of EF1γ was sequenced in its entirety. The EST terminates just upstream of poly(A) sequences in our initial cDNA isolate (Figure 1B).

For additional characterization and validation of two-hybrid interactions, the initial EF1γ cDNA and the full-length EF1γ EST clone LD07046 were both recloned into the pAS1 vector. Kinase constructs were made in the pACT II vector. Verification of previously observed interactions was made in the reciprocal orientation as an additional control (Figure 1A, Table 1). These constructs demonstrated that the human LAMMER kinase CLK2 also interacted with Drosophila EF1γ protein. However, isolated catalytic and noncatalytic subdomains of DOA and human CLK2 kinases did not support two-hybrid interactions with EF1γ (Table 1). The necessity for both catalytic and noncatalytic domains of LAMMER kinases for yeast two-hybrid interactions with substrates has been previously noted (Colwill et al. 1996b; Du et al. 1998; Nikolakaki et al. 2002).

TABLE 1.

Yeast two-hybrid interactions between LAMMER protein kinases and EF1γ constructs

| Vector | Vector insert | pAS1: EF1γ–Ctm | pAS1: EF1γ–FL | pAS1: EF1γ–TaqI | pAS1: EF1y–PstI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pACTII | None | (−) | (−) | (−) | (−) |

| pACTII | DOA-FL | (++) | (++) | (−) | (−) |

| pACTII | DOA-C | (−) | (−) | (−) | (−) |

| pACTII | hCLK2-FL | (+) | (+) | (−) | (−) |

| pACT: EF1γ–Ctm | |||||

| pAS1 | None | (−) | |||

| pAS1 | DOA-FL | (++) | |||

| pAS1 | DOA-N | (++) | |||

| pAS1 | DOA-C | (−) | |||

| pAS1 | hCLK2-FL | (++) | |||

| pAS1 |

hCLK2-N |

(−) |

(++), strong interaction; (+), moderate interaction; (−), no interaction; EF1γ–Ctm, C-terminal domain; FL, full-length; N, N-terminal noncatalytic domain; C, kinase catalytic domain.

The EF1γ domain responsible for interaction with the LAMMER kinases was refined via construction of two truncated constructs, PstIΔ and TaqIΔ, truncating the protein at amino acid residues 142 and 212, respectively (Figure 1B). These remove different stretches of C-terminal residues in the 431 amino acid protein. Neither truncated protein interacted with any LAMMER kinase construct, demonstrating that the C-terminal domain of EF1γ is necessary and sufficient for interaction with LAMMER protein kinases.

High levels of sequence identity characterize EF1γ proteins from diverse species:

We next embarked on characterization of Drosophila EF1γ to provide further insight into its function, as well as the possible significance of its interaction with DOA kinase. Drosophila EF1γ is remarkably similar in amino acid sequence when compared with orthologs from widely diverged species. For example, Drosophila EF1γ is 56% identical to the human protein (supporting information, Table S1) (Le Sourd et al. 2006; Gillen et al. 2008). These relationships span the entire length of the open reading frames. The high level of sequence identity among widely diverged species suggests essential and conserved functions for EF1γ proteins.

EF1γ expression during development:

Northern transfers show a single predominant mRNA species throughout development (Figure 2A). RT–PCR analysis, however, demonstrated the expression of an alternatively initiated mRNA with virtually identical transcript length encoding the same protein throughout development (Figure 2, B and C), as suggested by FlyBase.

Figure 2.—

EF1γ transcript expression is widespread and under control of E93. (A) A Northern transfer of wild-type developmentally staged RNA shows EF1γ is expressed at high levels throughout development. Lane 1, embryos 0–4 hr; lane 2, embryos 4–8 hr; lane 3, embryos 8–12 hr; lane 4, embryos 12–16 hr; lane 5, embryos 16–20 hr; lane 6, embryos 20–24 hr; lane 7, third instar larvae; lane 8, pupae 0–24 hr; lane 9, male adults 0–24 hr; and lane 10, female adults 0–24 hr. (B) A map derived from the BDGP representation for CG11901 (EF1γ), showing the location of the primers used for PCR analysis in C and F. Two EF1γ transcripts of approximately equal length and identical protein-coding capacity are produced via the use of alternative promoters and splicing. (C) RT–PCR analysis shows that both RNA isoforms of EF1γ are produced throughout development. Lane 1, embryos 0–4 hr; lane 2, embryos 0–24 hr; lane 3, first instar larvae; lane 4, third instar larvae; lane 5, pupae 0–24 hr; lane 6, adult females 0–24 hr; lane 7, adult males 0–24 hr; lane 8, female third instar larvae; and lane 9, male third instar larvae. (D) EF1γ transcript accumulation is regulated by the E93 transcription factor in the ecdysone pathway. Larvae and pupae were aged at 18° as described by Gorski et al. (2003). Lanes 1 and 2, third instar larvae; lanes 3 and 4, 16-hr pupae; lanes 5 and 6, 24-hr pupae. Lanes 1, 3, and 5, E93/Df(3R)93Fx2; lanes 2, 4, and 6, Canton-S (Cs) wild type. Note the relative reduction of EF1γ transcripts in 24-hr E93 pupae (lane 5), relative to similarly aged CS (lane 6). (E) Quantitation of the transfer shown in D, normalized to the rp49 loading control demonstrates that E93 mutant 24-hr pupae possess ∼50% of the level of EF1γ transcripts as wild-type pupae at this stage. Quantitation was performed using ImageJ software. (F) RT–PCR of individual EF1γ transcripts in E93 mutant pupae shows that only the RA transcript is under ecdysone control. Lanes 1 and 3, E93/Df(3R)93Fx2; lanes 2 and 4, CS. Lanes 1 and 2, 16-hr pupae; lanes 3 and 4, 24-hr pupae. Note the equivalent amplification in 16-hr samples (lanes 1 and 2), compared with the relative reduction of the RA transcript in the 24-hr E93/Df(3R)93Fx2 sample, (lane 3) compared to CS (lane 4), despite being evenly loaded (rp49 or RB).

Transcriptional regulation of EF1γ−RA by E93:

Gorski et al. (2003) showed that EF1γ transcripts are induced at the onset of autophagy, as are those encoding Doa (Kpebe and Rabinow 2008a). We therefore asked whether the locus was under control of the ecdysone-dependent transcription factor E93, as is Doa. As shown in Figure 2, D and E, flies of genotype E931/Df(3R)93Fx2 possess roughly equivalent levels of EF1γ transcripts as wild type (Canton-S, CS), at the end of the third larval instar and at 16 hr following pupation. However, at 24 hr following pupariation, EF1γ transcripts are reduced by ∼50% in E931/Df(3R)93Fx2, compared with CS controls, as determined by quantitation of the EF1γ signal, normalized to rp49 as a loading control. Semi-quantitative RT–PCR analysis further revealed that only the EF1γ–RA transcript is reduced in E93 mutants (Figure 2F), demonstrating isoform specificity in the effects of ecdysone signaling on EF1γ expression.

C. Cocco and L. Rabinow (unpublished data) show that the transcription factor RELISH also transcriptionally regulates Doa and it co-induces additional loci during the onset of autophagy in cooperation with E93. We therefore asked whether rel mutations might also affect EF1γ transcript accumulation. No effects were observed on EF1γ transcripts, as analyzed by RT–PCR, (not shown), indicating divergence, as well as similarities in the transcriptional control networks regulating these interacting gene products.

Ubiquitous but nonuniform EF1γ expression during embryogenesis:

In situ hybridization during embryonic development shows ubiquitous expression of EF1γ, including a maternal RNA contribution (Figure 3, left column). An antibody developed in rats against a recombinant Drosophila GST–EF1γ fusion protein was validated on an immunoblot of a strain carrying Df(3R)3450, a deficiency of the locus (Figure 4A). When this antibody was used to stain developing embryos for EF1γ protein (Figure 3, right column; also see Figure S1), general congruence with the in situ hybridization patterns was observed.

Figure 3.—

Ubiquitous but dynamic expression of EF1γ during embryogenesis. EF1γ expression during embryogenesis via in situ hybridization (A–E, left) and immunocytochemical staining (A–E, right). Anterior is to the left. Developmental stages based on Campos-Ortega and Hartenstein (1997). In A, precellular blastoderms show an anterior-to-posterior gradient of EF1γ RNA, which, however, is not clearly reflected with an antibody raised against the protein and DAB staining (however, see F). In cellularized blastoderms just prior to gastrulation (B), high levels of EF1γ RNA are observed ventrally (left, white arrow) and also at the posterior pole (white arrowhead). Curiously, EF1γ RNA is virtually absent at the ventral-anterior margin (black arrow). Lowered protein levels are also observed at the ventral-anterior margin (right, arrow), although posterior and ventral protein levels do not reflect the dramatic differences in mRNA concentrations. (C) An early stage-6 (left) and stage-8 embryo (right). mRNA is seen accumulating in a more uniform pattern at stage 6 than in previous stages (left). The beginnings of the cephalic furrow are just visible (white arrow and arrowhead). EF1γ protein at stage 8 (right) appears more heavily expressed in the developing ventral neurogenic region (arrows). (D) Stage-12 embryos, showing accumulation of particularly high RNA and protein levels in the developing and extending midgut (arrows). (E) Stage 13/14 embryos in which the midgut has fused. Higher levels of EF1γ continue to be expressed in the midgut, but protein accumulation is also noticeable in the condensing ventral nerve cord (arrow). (F) Immunofluorescence staining of precellular blastoderms demonstrates that EF1γ protein is localized to the posterior pole, (arrow, left). Hoechst staining of the same embryo (right). The posterior concentration of EF1γ is deposited maternally. Even the two pronuclei have not yet fused (white arrow). Similar posterior localization of EF1γ is also observed in later precellular blastoderms, in which nuclei have migrated to the embryonic cortex (Figure S1 C).

Figure 4.—

EF1γ protein is both cytoplasmic and partially microtubule-associated, but also nuclearly localized. (A) The specificity of antisera raised against a GST–EF1γ fusion protein was confirmed by probing protein extracts from Drosophila strain Df(3R)3450/TM6B, thus carrying only a single copy of the region 98E3 to 99A6-8, which includes EF1γ at 99A1-6. Extracts were compared for EF1γ immunoreactivity with CS (wild type) protein extracts on immunoblots. Lanes 1 and 3, Df(3R)3450/TM6B; lanes 2 and 4, CS. Equal amounts of total protein were loaded in lanes 1 and 2 (5 μg) and lanes 3 and 4 (10 μg). The same immunoblot was reprobed with anti-tubulin as a loading control. As an example, although lane 3 contains twice as much protein as lane 2, as shown by the tubulin-loading control, equal EF1γ signal is observed in these two lanes, demonstrating that the protein detected is encoded in the region deleted in Df(3R)3450. Similarly, twice as much EF1γ signal is observed in lane 4 compared with lane 3, although total protein loaded is equal. (B) EF1γ antibody diffusely labels the cytoplasm of Drosophila embryos at the cellular blastoderm stage (red), as shown by its exclusion from nuclei, but also colocalizes with the tubulin cytoskeleton (green), as indicated by the arrows showing some examples of colabeling. (C) EF1γ is found in total extracts (lane 1), but also in nuclear fractions (lane 2), in 0- to 24-hr pupal extracts.

An anterior-to-posterior gradient of maternally contributed EF1γ RNA is observed in precellular blastoderms (Figure 3A, left panel). Although widely distributed even at this stage when revealed with DAB staining (Figure 3A, right panel), immunofluorescent staining (Figure 3F, left) reveals that EF1γ protein is predominantly concentrated at the posterior pole of the embryo, which is maintained until at least formation of the cellular blastoderm (Figure S1). Immunocytochemical staining at later stages comparing fluorescence and DAB staining showed essentially identical patterns (Figure S1 and data not shown).

Immunoblot analysis of protein samples throughout development shows that EF1γ protein is expressed at all stages as a single protein species (data not shown). Cellular blastoderms stained with anti-EF1γ antibody reveal dispersed cytoplasmic staining but also stained punctae (Figure 4B). Inspection of embryos costained with anti-tubulin reveal that the punctae of concentrated EF1γ colocalize with tubulin (arrows), providing independent evidence supporting association of the proteins, as noted previously (Janssen and Moller 1988; Hughes et al. 2008). Although largely, if not exclusively cytoplasmic during embryogenesis, a nuclear EF1γ component was observed on immunotransfers in subcellular fractionations of 0- to 24-hr pupae (Figure 4C). This finding supports the notion that the protein may shuttle between the two compartments and that it possesses functions in addition to its presumed role in protein elongation.

EF1γ encodes a vital function:

Pbac{PB}Ef1γc01148 is inserted at the penultimate codon of EF1γ (CG11901), (http://flybase.org/; Figure 5), but completely complements Df(3R)Exel6212 (99A1–99A5), which deletes the locus. In contrast, GE29510, a P-element insertion, obtained from Genexel, carries an insertion at nucleotide 25,045,881 on 3R near the 5′ end of the EF1γ transcript (Figure 5), is recessive lethal, and fails to complement Df(3R)Exel6212. To determine whether the recessive lethality was due to a mutation induced in EF1γ and to generate a null allele, we mobilized the P-element in GE29510. Of 104 w− revertants recovered, 76 chromosomes complemented Df(3R)Exel6212. Four were sequenced and are precise excisions of the GE29510 P-element (accession no. EF192543). Among 28 imprecise excisions generating small deficiencies removing part or all of EF1γ or retaining only part of the original P-element insertion, allele A70 is a presumed null, since it deletes the 5′ third of EF1γ coding sequences, including the translation start site (Figure 5, accession no. EF192542). A70 fails to complement the recessive lethality of Df(3R)Exel6212 and of GE29510, demonstrating that the initial P-element insertion is also an authentic EF1γ allele.

Figure 5.—

Genomic structure of wild-type and EF1γ insertion and imprecise excision mutants. The region encoding EF1γ is 1948 bp long. The two transcripts, RA and RB, are shown under the scale bar. Both encode the same protein. The initial P-element insertion used in generation of alleles, EP(3) GE29510 is inserted at the beginning of the transcribed region. The null allele EF1γA70 was recovered by imprecise excision of the GE29510 P-element, deleting 662 bp and removing the first third of the coding region, but retaining 21 bp of the initial P-element insertion. The insertion site of PBac{PB}Ef1γc01148 at the penultimate codon of the locus is also indicated, although this insertion produces no phenotype. Untranslated regions of the transcripts are hatchmarked.

Three hypomorphic alleles, A15, A28, and A42 carry partial excisions of the original P-element and partial deletions of EF1γ (accession nos. EF192544, EF192545, and EF192546, respectively). Although they fail to complement Df(3R)Exel6212, they are homozygous viable and produce EF1γ protein at reduced quantities compared with wild-type (data not shown). The vast majority of EF1γA28 homozygotes die during pupation, and escaping adults cannot walk. They also display rough eyes and duplicated scutellar bristles. A42 homozygotes possess slightly rough eyes and duplicated scutellar bristles, while A15 homozygotes display no abnormal phenotypes.

Recessive lethality of the null EF1γA70 homozygotes occurs during larval stages, since 96% of embryos hatch as larvae in crosses between heterozygotes. Subsequently 73% of larvae emerge as pupae, 98% of which eclose as adults. Similar results were obtained in crosses between GE29510 heterozygotes. These observations are consistent with the maternally provided EF1γ RNA and protein providing function to the developing embryo and larvae.

Cell clones of the A70 null allele generated with FLP site-specific recombinase showed survival of the wild-type w twinspot in the eye, but no homozygous mutant cells (Figure 6A). Additionally, induction of transgenes expressing interfering RNA (IR), for EF1γ in sensory organ precursor cells with the sca–GAL4 driver eliminated thoracic bristles (data not shown), while their induction in the eye with GMR–GAL4 resulted in disrupted morphology (Figure 6D). Finally, expression of EF1γ–IR alleles with the strong ubiquitous da–GAL4 driver yielded lethality. Taken together with the results demonstrating recessive larval lethality, we conclude that EF1γ protein is required for both organismal and cellular viability.

Figure 6.—

EF1γ mutant and overexpression phenotypes. (A) GMR–GAL4/+, wild-type control. (B) GMR–GAL4/+; UAS–EF1γWT, line 1-2M. Note slightly roughened eyes in the color photo and occasional fused facets in the scanning electron micrograph (arrows). (C) GMR–GAL4/+; UAS–EF1γSer294Ala line 2-6M, also with slightly roughened eyes. Fused facets are also seen in the scanning electron micrograph. (D) EF1γ cell clones are cell lethal, since only wild-type homozygous (w) recombinant clones were observed; no w+/w+ homozygous mutant cells were recovered. (E) UAS–EF1γ−IR driven with GMR–GAL4 also yields roughened eyes. (F) Mild enhancement of Doa phenotypes was observed in EF1γGE29510 DoaHD/DoaDEM animals. This example shows failure of the posterior cross-vein to attach and ectopic wing venation (arrows). Other malformed wings showed misplaced posterior cross-veins and spurs on posterior cross-veins.

We also generated transformants of a full-length EF1γ cDNA in the pUAS-T vector. No aberrant phenotypes were observed when expression of the construct was driven with da–GAL4 or sca–GAL4 in wild-type backgrounds. Slightly roughened eyes were induced by expression of wild-type EF1γ transgenes via GMR–GAL4 (Figure 6C). Expression of EF1γ from these constructs using the ubiquitous da–GAL4 driver efficiently rescued recessive lethality of the EF1γA70 allele, demonstrating the functionality of the transgene.

No evident role for EF1γ in innate immunity:

Because EF1γ had been implicated in the innate immune response and as a component of the Drosophila phagosome (Foley and O'Farrell 2004; Stuart et al. 2007), we tested whether mutants at the locus were particularly susceptible to bacterial infection. However, survival times of either A15 homozygotes or A70 heterozygotes following septic injury were not different from wild-type controls (data not shown). Moreover, no differences in β-galactosidase activity expressed from a dipt–lacZ transgene in response to septic or aseptic injury were observed in A70 heterozygotes (data not shown). We conclude that EF1γ plays at best a subtle role in innate immunity in response to septic injury.

Genetic interactions of EF1γ:

We tested for genetic interactions between EF1γ alleles and those in one of the two paralogous EF1α loci in Drosophila melanogaster. Trans-heterozygotes between EF1γGE29510 and two recessive lethal alleles of the EF1α 48D locus, EF1α01275 or EF1αk06102, revealed no aberrant phenotypes and were also fertile. We also tested the A70 allele of EF1γ as a heterozygote for interactions with homozygous mutations in thor, the Drosophila ortholog of eIF4E-binding protein, since thor alleles both presumably affect translation and the immune response (Bernal and Kimbrell 2000). No visible phenotypes were observed.

In contrast to the lack of visible genetic interactions with EF1α or thor, we observed slight abnormalities in trans-heterozygous DoaHD EF1γGE29510/DoaDEM flies. Ectopic wing venation, failure of either of the cross-veins to attach, particularly the posterior cross-vein in males (Figure 6F), aberrantly formed cross-veins, occasional eye roughness, curved wings, and rarely, partial rotation of the female genitalia were noted (data not shown).

We also crossed both the GE29510 and A70 alleles to tra/+, tra2/+ and double-heterozygous tra2/+; tra/+ flies, to test whether EF1γ had any role in somatic sex determination, as does Doa. Because EF1γ was recently identified as a component of the 3′ end cleavage process, and Doa alleles reduce accumulation of RNA prematurely terminated in the copia element inserted in the apricot allele of white, we also tested whether heterozygous or homozygous EF1γ alleles would act as second-site modifiers of wa. No interactions in any of these mutant combinations were observed, however.

LAMMER kinases phosphorylate Drosophila EF1γ in vitro:

To further investigate the interactions between EF1γ and DOA kinase we first asked whether the former was an in vitro substrate for the latter. The cDNA encoding full-length EF1γ from BDGP EST clone LD07046 was expressed and purified as a fusion protein from the pGEX2T vector. The initial EF1γ cDNA clone interacting with DOA in the two-hybrid screen encoding the carboxy-terminal third of the protein was inserted into the pMalC2 plasmid, expressed, and purified on amylose columns. Both purified EF1γ fusion proteins were phosphorylated in vitro by recombinant DOA kinase (Figure 7), whereas the isolated GST or maltose binding domains were not (data not shown), demonstrating that phosphorylation of the recombinant EF1γ sequences occurs in its carboxy terminal, and not on the fusion domains. To examine the generality of EF1γ as a LAMMER kinase substrate, we tested both fusion proteins for phosphorylation by the tobacco LAMMER kinase PK12 (Sessa et al. 1996; Savaldi-Goldstein et al. 2000). Both EF1γ proteins were phosphorylated, demonstrating their generality as LAMMER kinase substrates. Attempts to further demonstrate direct protein–protein interactions between DOA and EF1γ via GST “pull-down” experiments to precipitate DOA kinase from Drosophila extracts were unsuccessful (data not shown), but it may be that the complex is insufficiently stable to survive.

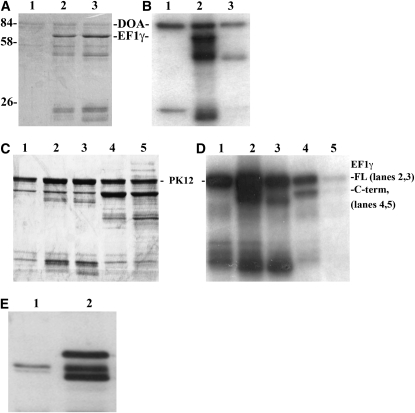

Figure 7.—

LAMMER kinases phosphorylate Drosophila EF1γ. (A–D) Purified recombinant EF1γ proteins were subjected to in vitro phosphorylation by DOA (A and B) and the tobacco LAMMER kinase, PK12 (C and D). (A and C) Coomassie stained gels, autoradiographed in B and D. (A and B) Lane 1, purified recombinant DOA kinase catalytic domain, showing autophosphorylation at 84 kDa and a presumed partial degradation product at roughly 25 kDa. Lane 2, DOA + wild-type full-length GST–EF1γ. Lane 3, DOA + GST–EF1γ Ser294Ala full-length protein. Note the virtual elimination of labeling of the intact 60 kDa EF1γ protein in lane 3 (Ser294Ala) compared with lane 2 (wild-type EF1γ protein), although the purified protein concentrations were equal (A). Some labeling of a presumed partially degraded EF1γ protein is observed in lane 3, as well as lane 2 at roughly 50 kDa, suggesting the existence of one or more secondary DOA phosphorylation sites in EF1γ. (C and D) Lane 1, purified PK12 kinase; lane 2, PK12 + full-length wild type EF1γ (the kinase and the full-length EF1γ fusion protein comigrate); lane 3, PK12 + full-length Ser193Ala EF1γ; lane 4, PK12 + C-terminal wild-type EF1γ fusion protein; PK12 + C-terminal Ser294Ala EF1γ. Drastically reduced phosphorylation of not only the mutant EF1γ protein, but also the autophosphorylation of PK12 kinase (lane 5), despite identical protein concentrations (C) suggests that the Ser294Ala mutation generated a competitive inhibitor. Similar results were obtained with DOA (data not shown). (E) EF1γ protein from Doa mutants migrates aberrantly. Lane 1, wild-type (Canton-S) 0- to 24-hr-old pupal protein extracts were compared for EF1γ protein mobility with extracts from Doa heteroallelic mutants (DoaHD/DoaDEM, lane 2). Aberrant migration of EF1γ from this mutant combination was observed repeatedly, whereas it was not observed in protein extracts prepared from heterozygotes for several Doa alleles, including these two (data not shown).

The principal LAMMER kinase in vitro phosphorylation site is conserved in all EF1γ orthologs:

Scanning of the translated protein sequence of Drosophila EF1γ at Scansite (http://scansite.mit.edu/) (Yaffe et al. 2001), identified a single likely LAMMER kinase phosphorylation site (Nikolakaki et al. 2002), at amino acid residue 294 in the Drosophila sequence. The essential features of this site (Arg at −3, Ser at P, are identical in EF1γ proteins from widely diverged species (Table 2). Moreover, acidic or highly charged residues (Glu/Asp at −7, −6, +2, and +3 relative to the phosphorylation site), are invariant among EF1γ proteins and also constitute important features of LAMMER kinase phosphorylation sites. The extreme conservation of these sequences suggests that they are critical to EF1γ function and that their phosphorylation by LAMMER kinases is also conserved.

TABLE 2.

Comparison of LAMMER protein kinase consensus phosphorylation sites with a sequence present in all EF1γ orthologs

| Position | −7 | −6 | −5 | −4 | −3 | −2 | −1 | 0 | +1 | +2 | +3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LAMMER kinase consensus | R/D | R/K | R/H | E/R | R | E/R | H/R | S | R | R/E | D/R |

| D | E | A | E | D | E | ||||||

| EF1γ consensus |

D |

D/E |

F/Y/W |

K |

R |

— |

Y |

S |

N |

E |

D |

The one-letter amino acid code is used. Boldface letters in the LAMMER kinase consensus sequence indicate amino acids that were most preferentially selected (selectivity value >2.0), while underlined residues are invariant in all identified substrates. Residues are numbered relative to the phosphorylation site at 0, data from Nikolakaki et al. (2002). Boldface letters in the EF1γ consensus indicate identical amino acids present in at least 9 of the 10 arbitrarily selected species compared; underlined residues are invariant. Serine 294 is the principal residue phosphorylated in Drosophila EF1γ by DOA and and PK12 kinases. The 9 arbitrarily chosen species and 11 orthologs compared were: D. melanogaster, Homo sapiens, Oryctolagus cuniculus, Artemia salina, Caenorhabditis elegans, Trypanosoma cruzi, Schizosaccharomyces pombe, and two paralogs each from Xenopus laevis and Saccharomyces cerevisiae.

We eliminated Ser294 via site-directed mutagenesis (Ser294Ala) to test whether it was a LAMMER kinase phosphorylation site, and tested the wild-type and modified full-length and C-terminal fusion proteins as substrates for both DOA and PK12 LAMMER kinases. The Ser294Ala amino acid replacement almost completely eliminated phosphorylation of the full-length EF1γ protein by both kinases, suggesting that we had identified the major LAMMER kinase phosphorylation site, but that additional minor sites also may exist (Figure 7). Phosphorylation of the modified C-terminal fusion EF1γ protein was completely eliminated by the Ser294Ala replacement for both DOA and PK12 kinases. Interestingly, reduced autophosphorylation of both DOA and PK12 was also observed when incubated with the Ser294Ala EF1γ C-terminal protein, suggesting that this modification generated a competitive inhibitor of these kinases.

Doa mutations induce altered mobility of EF1γ protein in vivo:

Mobility of EF1γ was examined on immunoblots of wild-type Drosophila protein extracts compared to those of a combination of Doa alleles (DoaDEM/DoaHD), to determine whether its phosphorylation was altered. EF1γ migrating at a molecular weight of ∼45 kDa was observed in both wild-type and Doa mutant extracts (Figure 7E). However, an additional band slightly lower in apparent molecular weight was observed in the Doa heteroallelic extracts, as well as a third band at a slightly higher apparent molecular weight of ∼48 kDa.

To rule out the possibility of different genetic backgrounds producing EF1γ proteins of different molecular weights, we tested the dependence of the novel band in Doa heteroallelic mutants as being dependent on the genotype at the Doa locus. Protein extracts from heterozygotes for the two alleles used in the heteroallelic test (DoaHD/+ and DoaDEM/+), as well as several additional alleles were examined on immunoblots. No aberrant migration of EF1γ protein was observed (data not shown), confirming that altered EF1γ migration depends upon the combination of mutant alleles at Doa and supporting the hypothesis that EF1γ is a DOA kinase substrate in vivo as well as in vitro. EF1γ migrating at the wild-type molecular weight in Doa mutant extracts is presumably due to the fact that the heteroallelic Doa combination is hypomorphic, and thus residual amounts of kinase are present.

We next tested whether treatment with three different nonspecific phosphatases (calf intestinal phosphatase, lambda phosphatase, and potato acid phosphatase), could induce EF1γ from wild-type Drosophila protein extracts to migrate aberrantly. Our prediction was that reduced phosphorylation would induce aberrant migration of the wild-type protein. However, none of the three phosphatases altered the mobility of wild-type EF1γ on immunoblots (data not shown). Treatment of Doa heteroallelic mutant extracts with the same phosphatases also failed to alter mobility EF1γ mobility (data not shown). Our results suggest that phosphorylation of EF1γ by DOA kinase prevents a secondary type of post-translational modification, whose nature remains unknown. Alternatively, DOA might be interacting with EF1γ at least in part via some indirect intermediate, which in turn could modify the latter protein. These two alternatives are not mutually exclusive. Attempts to analyze the presumed post-translational modification on EF1γ in Doa mutants by mass spectrometry were blocked because our antibodies were incapable of immunoprecipitation.

Rescue of EF1γ recessive lethality by transgene constructs is compromised by Ser294Ala mutations:

As noted above, a wild-type UAS–EF1γ cDNA transgene rescued recessive lethality of the EF1γA70 null allele when expressed via the da–GAL4 driver. Overexpression of this construct in the eye via the GMR–GAL4 driver also produced slightly roughened eyes (Figure 6C). To characterize further the role of DOA kinase phosphorylation might play in EF1γ function, we constructed Drosophila lines carrying cDNA transgenes carrying the Ser294Ala site-directed substitution. When expressed via GMR–GAL4, the mutant EF1γ transgenes also roughened the fly eye to approximately the same extent as the wild type (Figure 6, compare E and C). However, we noted distinctly lower survival of females in lines in which the mutant EF1γ transgene was used to rescue recessive lethality of the A70 null allele, in comparison with those expressing the wild-type cDNA (Table S2). To recapitulate the table, transgenes expressing the wild-type EF1γ cDNA rescued the approximate percentage of expected zygotes of both sexes (25% of the cross) for the two lines tested (n = 92 total for line 1-2M; 25.4% females and 27.3% males were of the rescued genotype; for line 1-4M, n = 157 total; 16.7% of the F1 were rescued females, 22.8% were rescued males). Transgenes expressing the Ser294Ala cDNA construct rescued males approximately as well as the wild type for both lines tested (line 2-3M, n = 28, 28.6% survival; line 2-4M, n = 69, 18.8% survival). In contrast, the Ser294Ala transgenes rescued female A70 homozygotes only poorly (line 2-3M, n = 60, 8.3% survival; line 2-4M, n = 73, 8.2% survival).

These results are supported by the observation that each of the two stocks of the wild-type and mutant UAS-driven transgenes behave differently. Two lines balanced for the wild-type transgene on the second chromosome and the EF1γA70 null allele on the third lose the TM6 balancer and become homozygous mutant, even without the presence of a GAL4 driver element. However, these lines still carry the A70 allele, as verified via complementation tests. The presence of low levels of EF1γ protein in these flies was confirmed on immunoblots (data not shown). The survival of homozygotes is thus apparently due to leaky transcription from the UAS promoter, yielding sufficient EF1γ expression to rescue the recessive lethality of the A70 allele. In contrast to the wild-type lines, neither of the two lines carrying the Ser294Ala transgene on the second chromosome lose their third-chromosome balancers, suggesting that they are impaired in their ability to rescue recessive lethality of A70 at low expression levels. Taken together, these results suggest that the Ser294Ala substitution partially compromises EF1γ activity, but that the protein retains the ability to perform some of its functions, particularly in males.

DISCUSSION

Our data show that the EF1γ locus is essential for both organismal and cellular viability and that the protein partially colocalizes to the microtubule network, as suggested by biochemical studies. We also detected EF1γ in pupal nuclear extracts, implying a role for it in processes in addition to translational elongation. Our observation is supported by the recent finding that EF1γ participates in the pre-mRNA 3′ end cleavage complex (Shi et al. 2009), which is also consistent with demonstrations that the protein binds RNA.

Expression patterns of EF1γ suggest that it may function in the formation of the anterior/posterior axis during Drosophila embryogenesis. We did not obtain any evidence suggesting a role for the protein in the innate immune response, in contrast to previously reported results. This discrepancy may be due to the use of a cell-culture model in the previous study, although we cannot rule out the possibility that other bacterial challenges might have elicited aberrant immune responses in EF1γ mutants.

Xenopus EF1γ is phosphorylated by cdc2 (CDK1) kinase at residue 230 at the onset of oocyte maturation (Bellé et al. 1989; Cormier et al. 1991; Mulner-Lorillon et al. 1992), but the function of this phosphorylation remains unknown. A possible role in elongation rates of protein synthesis is suggested by the finding that in vitro translation rates were affected, albeit in different and message-specific directions, by CDK1/cyclin B phosphorylation of EF1δ and EF1γ (Monnier et al. 2001). Sequence alignments reveal, however, that the CDK1 phosphorylation site in EF1γ is not conserved outside of vertebrate species (data not shown), in contrast to the LAMMER kinase phosphorylation site found in all orthologs described here. Thus the CDK1 phosphorylation presumably serves a function restricted to vertebrates, whereas the LAMMER kinase phosphorylation would appear to be more universal.

Although we did not identify a specific cellular function for EF1γ, our data show that it interacts with and is a substrate for DOA kinase in vitro and is also likely to be one in vivo. Several lines of evidence demonstrate interaction between the Doa and EF1γ loci and their proteins. Genetic interactions between the two loci suggest a functional role for this interaction in patterning wing venation and in other tissues as well. The reduced ability of a Ser294Ala EF1γ construct to rescue lethality of a null allele compared with the wild type suggests that this phosphorylatable residue, an in vitro phosphorylation site for DOA and other LAMMER kinases, is required for full EF1γ activity. Moreover, the extreme conservation of the LAMMER kinase phosphorylation site in all EF1γ orthologs, as well as the interaction and phosphorylation of EF1γ with human and plant LAMMER protein kinases support the hypothesis that this phosphorylation is universally conserved among eukaryotes.

Our results also suggest that phosphorylation of EF1γ by DOA kinase prevents a secondary and unknown post-translational modification. DOA kinase was isolated in genomewide yeast two-hybrid screens with a number of ubiquitin-related conjugating or hydrolyzing enzymes (Giot et al. 2003; Stanyon et al. 2004), and EF1γ is associated with proteosomal components during oocyte maturation in Xenopus (Tokumoto et al. 2003). It is thus tempting to speculate that phosphorylation of EF1γ by LAMMER kinases may also play a role in this association and the subsequent modification of EF1γ.

Acknowledgments

The advice of Lenore Neigeborn was essential to the success of the two-hybrid screen. We thank Steve Elledge, Karen Colwill, Bruce Edgar, and Bob Lahue for providing published and unpublished materials and François Leulier for bacterial strains and detailed protocols for the immunity assays. Flies were obtained from the Indiana University Drosophila stock center, the Japanese National Institute of Genetics Genetic Strains Research Center, and Genexel. Sheila Norton of the University of Nebraska Medical Center (UNMC) Molecular Biology Core Laboratory at the National Cancer Institute (NCI)-supported UNMC/Eppley Cancer Center performed initial DNA sequencing, and Severine Domenichini (Plateforme Microscopie Electronique, Imagerie-Biocellulaire IFR87, Orsay-Gif, Université Paris 11), the scanning electron micrography. This work was supported by grants IBN9724006 from the National Science Foundation, the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique (CNRS), and the Université Paris Sud 11. Additional funding was provided by the French Ministry of Research and the CNRS (03G138), in the Biological Resource Center program for fundamental research: “Natural and induced variants in Drosophila” and by the Division de la Recherche, Université Paris 11. Y.F. was supported by graduate fellowships from the Université de Paris Sud 11 and the China Scholarship Council.

Supporting information is available online at http://www.genetics.org/cgi/content/full/genetics.109.109553/DC1.

References

- Al-Maghrebi, M., H. Brule, M. Padkina, C. Allen, W. M. Holmes et al., 2002. The 3′ untranslated region of human vimentin mRNA interacts with protein complexes containing eEF-1gamma and HAX-1. Nucleic Acids Res. 30 5017–5028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashburner, M., 1989. Drosophila: A Laboratory Handbook. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY.

- Ausubel, F. M., R. Brent, R. E. Kingston, D. D. Moore, J. G. Seidman et al. (Editors), 1989. Current Protocols in Molecular Biology. Greene/Wiley Publishing, New York.

- Bellé, R., J. Derancourt, R. Poulhe, J.-P. Capony, R. Ozon et al., 1989. A purified complex from Xenopus oocytes contains a P-47 protein, an in vivo substrate of MPF, and a p30 protein respectively homologous to elongation factors EF1γ and EF1B. FEBS Lett. 255 101–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernal, A., and D. A. Kimbrell, 2000. Drosophila Thor participates in host immune defense and connects a translational regulator with innate immunity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97 6019–6024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campos-Ortega, J. A., and V. Hartenstein, 1997. The Embryonic Development of Drosophila melanogaster. Springer, Berlin.

- Carvalho, M. G., J. F. Carvalho and W. C. Merrick, 1984. Biological characterization of various forms of elongation factor 1 from rabbit reticulocytes. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 234 603–611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colwill, K., L. L. Feng, J. M. Yeakley, G. D. Gish, J. F. Caceres et al., 1996. a SRPK1 and Clk/STY protein kinases show distinct substrate specificities for Serine/Arginine-rich splicing factors. J. Biol. Chem. 271 24569–24575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colwill, K., T. Pawson, B. Andrews, J. Prasad, J. L. Manley et al., 1996. b The Clk/STY protein kinase phosphorylates SR splicing factors and regulates their intranuclear distribution. EMBO J. 15 265–275. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cormier, P., H. B. Osborne, J. Morales, T. Bassez, R. Poule et al., 1991. Molecular cloning of Xenopus elongation factor 1g, major M-phase promoting factor substrate. Nucleic Acids Res. 19 6644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dasmahapatra, B., L. Skogerson and K. Chakraburtty, 1981. Protein synthesis in yeast II. Purification and properties of elongation factor 1 from Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Biol. Chem. 256 10005–10011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorsett, D., 1990. Potentiation of a polyadenylation site by a downstream protein-DNA interaction. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 87 4373–4377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du, C., M. E. McGuffin, B. Dauwalder, L. Rabinow and W. Mattox, 1998. Protein phosphorylation plays an essential role in the regulation of alternative splicing and sex determination in Drosophila. Mol. Cell 2 741–750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durfee, T., K. Becherer, P. L. Chen, S. H. Yeh, Y. Yang et al., 1993. The retinoblastoma protein associates with the protein phosphatase type 1 catalytic subunit. Genes Dev. 7 555–569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ejiri, S., 2002. Moonlighting functions of polypeptide elongation factor 1: from actin bundling to zinc finger protein R1-associated nuclear localization. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 66 1–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foley, E., and P. H. O'Farrell, 2004. Functional dissection of an innate immune response by a genome-wide RNAi screen. PLoS Biol. 2 1091–1106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillen, C. M., Y. Gao, M. M. Niehaus-Sauter, M. R. Wylde and M. G. Wheatly, 2008. Elongation factor 1Bgamma (eEF1Bgamma) expression during the molting cycle and cold acclimation in the crayfish Procambarus clarkii. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. B Biochem. Mol. Biol. 150 170–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giot, L., J. S. Bader, C. Brouwer, A. Chaudhuri, B. Kuang et al., 2003. A protein interaction map of Drosophila melanogaster. Science 302 1727–1736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorski, S. M., S. Chittaranjan, E. D. Pleasance, J. D. Freeman, C. L. Anderson et al., 2003. A SAGE approach to discovery of genes involved in autophagic cell death. Curr. Biol. 13 358–363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes, J. R., A. M. Meireles, K. H. Fisher, A. Garcia, P. R. Antrobus et al., 2008. A microtubule interactome: complexes with roles in cell cycle and mitosis. PLoS Biol. 6 785–795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James, P., J. Halladay and E. A. Craig, 1996. Genomic libraries and a host strain designed for highly efficient two-hybrid selection in yeast. Genetics 144 1425–1436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janssen, G. M. C., and W. Moller, 1988. Elongation factor 1βγ from Artemia: purification and properties of its subunits. Eur. J. Biochem. 171 119–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeppesen, M. G., P. Ortiz, W. Shepard, T. G. Kinzy, J. Nyborg et al., 2003. The crystal structure of the glutathione S-transferase-like domain of elongation factor 1Bgamma from Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Biol. Chem. 278 47190–47198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S., J. Kellner, C. H. Lee and P. A. Coulombe, 2007. Interaction between the keratin cytoskeleton and eEF1Bg affects protein synthesis in epithelial cells. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 14 982–983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kpebe, A., and L. Rabinow, 2008. a Alternative promoter usage generates multiple evolutionarily conserved isoforms of Drosophila DOA kinase. Genesis 46 132–143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kpebe, A., and L. Rabinow, 2008. b Dissection of DOA kinase isoform functions in Drosophila. Genetics 179 1973–1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Sourd, F., S. Boulben, R. Le Bouffant, P. Cormier, J. Morales et al., 2006. eEF1B: at the dawn of the 21st century. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1759 13–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee, K., C. Du, M. Horn and L. Rabinow, 1996. Activity and autophosphorylation of LAMMER protein kinases. J. Biol. Chem. 271 27299–27303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee, C. Y., E. A. Clough, P. Yellon, T. M. Teslovich, D. A. Stephan et al., 2003. Genome-wide analyses of steroid- and radiation-triggered programmed cell death in Drosophila. Curr. Biol. 13 350–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lew, Y., D. V. Jones, W. M. Mars, D. Evans, D. Byrd et al., 1992. Expression of elongation factor-1 gamma-related sequence in human pancreatic cancer. Pancreas 7 144–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez, A. J., 1998. Alternative splicing of pre-mRNA: developmental consequences and mechanisms of regulation. Annu. Rev. Genet. 32 279–305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathur, S., K. R. Cleary, N. Inamdar, Y. H. Kim, P. Steck et al., 1998. Overexpression of elongation factor-1gamma protein in colorectal carcinoma. Cancer 82 816–821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menegay, H. J., M. P. Myers, F. M. Moeslein and G. E. Landreth, 2000. Biochemical characterization and localization of the dual specificity kinase CLK1. J. Cell Sci. 113 3241–3253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merrick, W. C., and J. Nyborg (Editors), 2000. The Protein Synthesis Elongation Cycle. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY.

- Mimori, K., M. Mori, S. Tanaka, T. Akiyoshi and K. Sugimachi, 1995. The overexpression of elongation factor 1 gamma mRNA in gastric carcinoma. Cancer 75 1446–1449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mimori, K., M. Mori, H. Inoue, H. Ueo, K. Mafune et al., 1996. Elongation factor 1 gamma mRNA expression in oesophageal carcinoma. Gut 38 66–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moeslein, F. M., M. P. Myers and G. E. Landreth, 1999. The CLK family kinases CLK1 and CLK2 phosphoryate and activate the tyrosine phosphatase PTP-1B. J. Biol. Chem. 274 26697–26704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monnier, A., R. Belle, J. Morales, P. Cormier, S. Boulben et al., 2001. Evidence for regulation of protein synthesis at the elongation step by CDK1/cyclin B phosphorylation. Nucleic Acids Res. 29 1453–1457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulner-Lorillon, O., P. Cormier, J. Cavadore, J. Morales, R. Poulhe et al., 1992. Phosphorylation of Xenopus elongation factor-1g by cdc2 protein kinase: identification of the phosphorylation site. Exp. Cell Res. 202 549–551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nayler, O., S. Stamm and A. Ullrich, 1997. Characterization and comparison of four serine- and arginine-rich (SR) protein kinases. Biochem. J. 326 693–700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nayler, O., F. Schnorrer, S. Stamm and A. Ullrich, 1998. The cellular localization of the murine Serine/Arginine-rich protein kinase CLK2 is regulated by Serine 141 autophosphorylation. J. Biol. Chem. 273 34341–34348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikolakaki, E., C. Du, J. Lai, L. Cantley, T. Giannakouros et al., 2002. Phosphorylation by LAMMER protein kinases: determination of a consensus site, identification of in vitro substrates and implications for substrate preferences. Biochemistry 41 2055–2066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Connell, P. O., and M. Rosbash, 1984. Sequence, structure and codon preference of the Drosophila ribosomal protein 49 gene. Nucleic Acids Res. 12 5495–5513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olarewaju, O., P. A. Ortiz, W. Q. Chowdhury, I. Chatterjee and T. G. Kinzy, 2004. The translation elongation factor eEF1B plays a role in the oxidative stress response pathway. RNA Biol. 1 e12–e17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papavassiliou, A. G., and D. Bohmann, 1992. Dephosphorylation of phosphoproteins with potato acid phosphatase. Methods Mol. Cell. Biol. 3 149–152. [Google Scholar]

- Prasad, J., and J. L. Manley, 2003. Regulation and substrate specificity of the SR protein kinase Clk/Sty. Mol. Cell. Biol. 23 4139–4149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabinow, L., S. L. Chiang and J. A. Birchler, 1993. Mutations at the Darkener of apricot locus modulate transcript levels of copia and copia-induced mutations in Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics 134 1175–1185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riis, B., S. I. S. Rattan, B. F. C. Clark and W. C. Merrick, 1990. Eukaryotic protein elongation factors. Trends Biol. Chem. 15 420–424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romeo, Y., and B. Lemaitre, 2008. Drosophila immunity: methods for monitoring the activity of Toll and Imd signaling pathways. Methods Mol. Biol. 415 379–394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savaldi-Goldstein, S., G. Sessa and R. Fluhr, 2000. The ethylene-inducible PK12 kinase mediates the phosphorylation of SR splicing factors. Plant J. 21 91–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sessa, G., V. Raz, S. Savaldi and R. Fluhr, 1996. PK12, a plant dual-specificity protein kinase of the LAMMER family, is regulated by the hormone ethylene. Plant Cell 8 2223–2234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi, Y., D. Campigli Di Giammartino, D. Taylor, A. Sarkeshik, W. J. Rice et al., 2009. Molecular architecture of the human pre-mRNA 3′ processing complex. Mol. Cell 33 365–375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slobin, L. I., and W. Moller, 1978. Purification and properties of an elongation factor functionally analogous to bacterial elongation factor Ts from embryos of Artemia salina. Eur. J. Biochem. 84 69–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanyon, C. A., G. Liu, B. A. Mangiola, N. Patel, L. Giot et al., 2004. A Drosophila protein-interaction map centered on cell-cycle regulators. Genome Biol. 5 R96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staudinger, J., M. Perry, S. J. Elledge and E. N. Olson, 1993. Interactions among vertebrate helix-loop-helix proteins in yeast using the two-hybrid system. J. Biol. Chem. 268 4608–4611. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stuart, L. M., J. Boulais, G. M. Charriere, E. J. Hennessy, S. Brunet et al., 2007. A systems biology analysis of the Drosophila phagosome. Nature 445 95–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tautz, D., and C. Pfeifle, 1989. A non-radioactive in situ hybridization method for the localization of specific RNAs in Drosophila embryos reveals translational control of the segmentation gene hunchback. Chromosoma 98 81–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tokumoto, T., A. Kondo, J. Miwa, R. Horiguchi, M. Tokumoto et al., 2003. Regulated interaction between polypeptide chain elongation factor-1 complex with the 26S proteasome during Xenopus oocyte maturation. BMC Biochem. 4 6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu, T., and G. M. Rubin, 1993. Analysis of genetic mosaics in developing and adult Drosophila tissues. Development 117 1223–1237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yaffe, M. B., G. G. Leparc, J. Lai, T. Obata, S. Volinia et al., 2001. A motif-based scanning approach for genome-wide prediction of signaling pathways. Nat. Biotech. 19 348–353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yun, B., R. Farkas, K. Lee and L. Rabinow, 1994. The Doa locus encodes a member of a new protein kinase family, and is essential for eye and embryonic development in Drosophila melanogaster. Genes Dev. 8 1160–1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yun, B., K. Lee, R. Farkas, C. Hitte and L. Rabinow, 2000. The LAMMER protein kinase encoded by the Doa locus of Drosophila is required in both somatic and germ-line cells, and is expressed as both nuclear and cytoplasmic isoforms throughout development. Genetics 156 749–761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]