Abstract

Purpose

To analyze the prognostic significance of NPM1 mutations, and the associated gene- and microRNA-expression signatures in older patients with de novo, cytogenetically normal acute myeloid leukemia (CN-AML) treated with intensive chemotherapy.

Patients and Methods

One hundred forty-eight adults age ≥ 60 years with de novo CN-AML, enrolled onto Cancer and Leukemia Group B protocols 9720 and 10201, were studied at diagnosis for NPM1, FLT3, CEBPA, and WT1 mutations, and gene- and microRNA-expression profiles.

Results

Patients with NPM1 mutations (56%) had higher complete remission (CR) rates (84% v 48%; P < .001) and longer disease-free survival (DFS; P = .047; 3-year rates, 23% v 10%) and overall survival (OS; P < .001; 3-year rates, 35% v 8%) than NPM1 wild-type patients. In multivariable analyses, NPM1 mutations remained independent predictors for higher CR rates (P < .001) and longer DFS (P = .004) and OS (P < .001), after adjustment for other prognostic clinical and molecular variables. Unexpectedly, the prognostic impact of NPM1 mutations was mainly observed in patients ≥ 70 years. Gene- and microRNA-expression profiles associated with NPM1 mutations were similar across older patient age groups and similar to those in younger (< 60 years) patients with CN-AML. These profiles were characterized by upregulation of HOX genes and their embedded microRNAs and downregulation of the prognostically adverse MN1, BAALC, and ERG genes.

Conclusion

NPM1 mutations have favorable prognostic impact in older patients with CN-AML, especially those age ≥ 70 years. The gene- and microRNA-expression profiles suggest that NPM1 mutations constitute a marker defining a biologically homogeneous entity in CN-AML that might be treated with specific and/or targeted therapies across age groups.

INTRODUCTION

The majority of patients with newly diagnosed acute myeloid leukemia (AML) in the United States are age ≥ 60 years.1 Although the outcome of younger adults (< 60 years) has improved, the prognosis of older patients remains poor, with complete remission (CR) rates of 40% to 60% and long-term overall survival (OS) rates of 5% to 16%.2–6 The worse outcome of older patients has been attributed to such factors as preceding hematologic disorders, over-representation of high-risk cytogenetics, or other adverse prognostic clinical characteristics.4–9 However, in approximately 65% to 75% of older patients, AML arises de novo,9–11 and in 45% to 50% of these patients, leukemic blasts are cytogenetically normal (CN).3,6

During the last decade, de novo CN-AML has been found to be heterogeneous at the submicroscopic level in younger adults,12 with mutations in the NPM1 gene being the most frequent genetic alterations.13–20 Indeed, AML with NPM1 mutations has been added as a provisional entity in the 2008 World Health Organization classification of AML.21 The frameshift caused by an NPM1 mutation results in aberrant cytoplasmic localization of the nucleophosmin protein, which likely interferes with its biologic functions in ribosomal assembly and the p53 and ARF pathways.22

Most studies investigating the prognostic impact of NPM1 mutations in CN-AML have been conducted in patients ≤ 60 years,13,14,19,20 or in cohorts comprising both younger and older patients.15–18 Although analyses of NPM1 mutations alone yielded inconsistent results in CN-AML, when considered along with the FLT3-internal tandem duplication (FLT3-ITD) status, NPM1 mutations conferred more favorable prognosis in patients lacking FLT3-ITD in comparison with the outcomes of patients with wild-type NPM1 or FLT3-ITD, or both.13–20

To our knowledge, no study has analyzed the predictive significance of NPM1 mutations as a single marker in the context of other prognostic factors in older patients with CN-AML.6,23–25 Therefore, we evaluated NPM1 mutations in a relatively large set of adults ≥ 60 years with CN-AML treated with intensive chemotherapy and characterized comprehensively with regard to clinical and molecular features. Furthermore, to gain biologic insights, we determined the gene- and microRNA-expression signatures associated with NPM1 mutations in these older patients.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Patients, Cytogenetic Analysis, and Treatment

We studied pretreatment bone marrow (BM) samples of 148 patients age ≥ 60 years with de novo CN-AML and material available for analysis. Cytogenetic analyses at diagnosis were performed by Cancer and Leukemia Group B (CALGB) –approved institutional cytogenetic laboratories as part of the cytogenetic companion study 8461 and confirmed by central karyotype review.26,27 To establish CN-AML, ≥ 20 metaphase cells from diagnostic BM had to be analyzed and the karyotype found to be normal.27 Institutional review board–approved informed consent for participation in the studies was obtained from all patients. Patients with preceding hematologic disorders or treatment-related AML were excluded, as were those who later underwent transplantation in first CR. The patients were enrolled onto CALGB front-line treatment protocols 972010,28 (n = 83) or 1020129 (n = 65; for treatment details see Appendix, online only).

Analysis of NPM1 and Other Molecular Markers

Sample preparation is described in the Appendix. NPM1 mutational analysis was performed as previously reported.14 Briefly, DNA fragments spanning the entire NPM1 exon 12 were amplified by polymerase chain reaction and directly sequenced. Reference sequences for mutational analyses are under NCBI accession numbers NM_002520.5 and NP_002511.1. Other molecular markers, that is, FLT3-ITD,30 FLT3-tyrosine kinase domain mutations (FLT3-TKD),31 CEBPA mutations,32 and WT1 mutations33 were assessed centrally as previously reported.

Genome-Wide Expression Analyses

Gene- and microRNA-expression was profiled using the Affymetrix U133 plus 2.0 array (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA) and the Ohio State University custom microRNA array (OSU_CCC version 4.0), respectively, as reported previously,32,34,35 and described in the Appendix.

Statistical Analysis

Definitions of clinical end points (ie, CR, disease-free survival [DFS], and OS) are provided in the Appendix. Associations between patients with and without NPM1 mutations for baseline demographic, clinical, and molecular features were compared using the Fisher's exact and Wilcoxon rank sum tests for categorical and continuous variables, respectively. Estimated probabilities of OS and DFS were calculated using the Kaplan-Meier method, and the log-rank test was used to evaluate differences between survival distributions.

Multivariable analyses are detailed in the Appendix. Multivariable logistic regression models were constructed to analyze factors related to the probability of achieving CR using a limited backward selection procedure. Multivariable proportional hazards models were constructed for OS and DFS to evaluate the impact of NPM1 mutations by adjusting for other variables using a limited backward selection procedure. For achievement of CR, estimated odds ratios, and for survival end points, hazard ratios with their corresponding 95% CIs, were obtained for each significant prognostic factor. All outcome end point models (CR, DFS, OS) were adjusted for treatment protocol (9720 v 10201).

For expression profiling, summary measures of gene and microRNA expression were computed, normalized, and filtered (Appendix). Expression signatures were derived by comparing gene and microRNA expression between NPM1 mutated (NPM1mut) and NPM1 wild-type (NPM1wt) patients. Univariable significance levels of .001 for gene- and .005 for microRNA-expression profiling were used to determine, respectively, the probe sets and microRNA probes that composed the signatures. Prediction of NPM1 mutation status using gene- and microRNA-expression profiles is described in the Appendix. All analyses were performed by the CALGB Statistical Center.

RESULTS

Clinical Characteristics and Molecular Markers at Diagnosis

Overall, 83 (56%) patients harbored NPM1 mutations. The most frequent was a type A mutation (n = 67 [81%]), that is, the duplication of TCTG at position c.860_863 (NCBI Accession NM_002520.5).13 Additional mutations included type B (n = 4 [5%]), type D (n = 3 [4%]), and others (n = 9 [11%]) (Appendix Table A1, online only).13 NPM1mut patients were younger (P = .01), had higher white blood counts (WBC; P = .01) and higher percentages of blood (P = .01) and BM (P = .02) blasts, experienced gum hypertrophy more often (P = .02), and were more frequently FLT3-ITD positive (P = .01) than NPM1wt patients (Table 1).

Table 1.

Clinical and Molecular Characteristics According to NPM1 Mutation Status in Older Patients With Cytogenetically Normal De Novo Acute Myeloid Leukemia

| Characteristic |

NPM1 Mutated (n = 83) |

NPM1 Wild-Type (n = 65) |

P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | % | No. | % | ||

| Age, years | .01 | ||||

| Median | 67 | 71 | |||

| Range | 60-81 | 60-83 | |||

| Age group, years | .01 | ||||

| 60-69 | 52 | 63 | 27 | 42 | |

| ≥ 70 | 31 | 37 | 38 | 58 | |

| Sex | .40 | ||||

| Male | 43 | 52 | 39 | 60 | |

| Female | 40 | 48 | 26 | 40 | |

| Race | .36 | ||||

| White | 77 | 94 | 56 | 89 | |

| Nonwhite | 5 | 6 | 7 | 11 | |

| Performance status* | .84 | ||||

| Fully active (0) | 20 | 24 | 18 | 29 | 0/1 v 2/3/4 |

| Ambulatory (1) | 46 | 56 | 31 | 50 | |

| In bed < 50% of time (2) | 14 | 17 | 13 | 21 | |

| In bed > 50% of time (3) | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |

| Completely bedridden (4) | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |

| Hemoglobin, g/dL | .12 | ||||

| Median | 9.4 | 9.3 | |||

| Range | 6.0-15.0 | 6.5-13.6 | |||

| Platelet count, × 109/L | .32 | ||||

| Median | 59.5 | 69.5 | |||

| Range | 17-356 | 11-510 | |||

| WBC, × 109/L | .01 | ||||

| Median | 26.2 | 7.0 | |||

| Range | 1.0-249.3 | 1.0-434.1 | |||

| Percentage of PB blasts | .01 | ||||

| Median | 44.5 | 30 | |||

| Range | 0-97 | 0-96 | |||

| Percentage of BM blasts | .02 | ||||

| Median | 66 | 47 | |||

| Range | 11-93 | 7-96 | |||

| FAB† | — | ||||

| M0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 9 | |

| M1 | 15 | 31 | 5 | 15 | |

| M2 | 9 | 19 | 13 | 39 | |

| M4 | 11 | 23 | 6 | 18 | |

| M5 | 10 | 21 | 5 | 15 | |

| M6 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 3 | |

| Extramedullary involvement | 20 | 25 | 15 | 23 | .85 |

| CNS | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | — |

| Hepatomegaly | 3 | 4 | 3 | 5 | 1.00 |

| Splenomegaly | 5 | 6 | 8 | 12 | .25 |

| Lymphadenopathy | 3 | 4 | 4 | 6 | .70 |

| Skin infiltrates | 3 | 4 | 4 | 6 | .70 |

| Gum hypertrophy | 12 | 15 | 2 | 3 | .02 |

| Mediastinal mass | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | — |

| FLT3-ITD | .01 | ||||

| Present | 33 | 40 | 13 | 20 | |

| Absent | 50 | 60 | 52 | 80 | |

| FLT3-TKD | .43 | ||||

| Present | 10 | 12 | 5 | 8 | |

| Absent | 73 | 88 | 60 | 92 | |

| WT1 | .73 | ||||

| Mutated | 4 | 5 | 4 | 6 | |

| Wild-type | 79 | 95 | 61 | 94 | |

| CEBPA | .07 | ||||

| Mutated | 6 | 7 | 11 | 17 | |

| Wild-type | 77 | 93 | 54 | 83 | |

| Protocol | .50 | ||||

| 9720 | 49 | 59 | 34 | 52 | |

| 10201 | 34 | 41 | 31 | 48 | |

| Induction treatment and protocol | — | ||||

| ADE (9720) | 44 | 53 | 32 | 49 | |

| ADEP (9720) | 5 | 6 | 2 | 3 | |

| AD (10201) | 21 | 25 | 17 | 26 | |

| ADG (10201) | 13 | 16 | 14 | 22 | |

Abbreviations: PB, peripheral blood; BM, bone marrow; FAB, French-American-British classification; FLT3-ITD, internal tandem duplication of the FLT3 gene; FLT3-TKD, tyrosine kinase domain mutations of the FLT3 gene; in induction treatment: A, cytarabine; D, daunorubicin; E, etoposide; P, valspodar (PSC 833); G, oblimersen sodium (Genasense, G3139; Genta, Berkeley Heights, NJ).

Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group/Zubrod/WHO performance status score.

FAB classifications are centrally reviewed.

Prognostic Impact of NPM1 Mutations

NPM1mut patients had a significantly better CR rate than NPM1wt patients (84% v 48%; P < .001; Table 2). In multivariable analyses, mutated NPM1 was independently associated with CR achievement (P < .001), after adjustment for WBC (P = .001). NPM1mut patients had more than nine-fold higher odds of achieving CR compared with NPM1wt patients (Table 3).

Table 2.

Outcomes According to NPM1 Mutation Status in Older Patients With Cytogenetically Normal De Novo Acute Myeloid Leukemia, Separately in Those Age 60-69 Years and ≥ 70 Years

| Outcome | NPM1 Mutated | NPM1 Wild-Type | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| All patients | n = 83 | n = 65 | |

| Complete remission | < .001 | ||

| No. | 70 | 31 | |

| % | 84 | 48 | |

| Disease-free survival | .047 | ||

| Median, years | 1.1 | 0.7 | |

| % disease free at 3 years | 23 | 10 | |

| 95% CI | 14-33 | 2-23 | |

| Overall survival | < .001 | ||

| Median, years | 1.6 | 1.1 | |

| % alive at 3 years | 35 | 8 | |

| 95% CI | 25-45 | 3-16 | |

| Patients age 60-69 years | n = 52 | n = 27 | |

| Complete remission | .031 | ||

| No. | 43 | 16 | |

| % | 83 | 59 | |

| Disease-free survival | .48 | ||

| Median, years | 0.9 | 0.7 | |

| % disease free at 3 years | 19 | 13 | |

| 95% CI | 9-31 | 2-33 | |

| Overall survival | .22 | ||

| Median, years | 1.3 | 1.2 | |

| % alive at 3 years | 29 | 11 | |

| 95% CI | 17-41 | 3-26 | |

| Patients age ≥ 70 years | n = 31 | n = 38 | |

| Complete remission | < .001 | ||

| No. | 27 | 15 | |

| % | 87 | 39 | |

| Disease-free survival | .018 | ||

| Median, years | 1.5 | 0.7 | |

| % disease free at 3 years | 30 | 7 | |

| 95% CI | 14-47 | 0-26 | |

| Overall survival | < .001 | ||

| Median, years | 2.5 | 0.9 | |

| % alive at 3 years | 45 | 5 | |

| 95% CI | 27-61 | 1-16 |

Outcomes according to NPM1 mutation status are indicated for the whole study population of 148 patients ≥ 60 years (range, 60-83 years) with cytogenetically normal de novo acute myeloid leukemia, and separately for the age groups comprising 79 patients age 60-69 years and 69 patients age ≥ 70 years.

Table 3.

Multivariable Analyses for Outcome According to the NPM1 Mutation Status in All Older Patients With Cytogenetically Normal De Novo Acute Myeloid Leukemia, and Separately in Those Age 60-69 Years and ≥ 70 Years

| Group | CR |

DFS |

OS |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | P | HR | 95% CI | P | HR | 95% CI | P | |

| All patients | |||||||||

| NPM1, mutated v wild-type | 9.35 | 3.73 to 23.26 | < .001 | 0.48 | 0.29 to 0.78 | .004 | 0.43 | 0.30 to 0.63 | < .001 |

| WBC, each 50 unit increase | 0.43 | 0.26 to 0.71 | .001 | 1.78 | 1.26 to 2.51 | .005 | 1.19 | 1.05 to 1.36 | .008 |

| FLT3-ITD, present v absent | 1.87 | 1.10 to 3.18 | .012 | 1.66 | 1.11 to 2.48 | .014 | |||

| Patients age 60-69 years | |||||||||

| NPM1, mutated v wild-type | 4.7 | 1.3 to 16.8 | .017 | ||||||

| WBC, each 50 unit increase | 0.4 | 0.2 to 0.9 | .021 | ||||||

| Patients age ≥ 70 years | |||||||||

| NPM1, mutated v wild-type | 19.23 | 3.98 to 90.90 | < .001 | 0.31 | 0.14 to 0.68 | .003 | 0.27 | 0.15 to 0.48 | < .001 |

| WBC, each 50 unit increase | 0.43 | 0.22 to 0.86 | .017 | ||||||

NOTE. ORs > 1 (< 1) mean higher (lower) CR rate for the first category listed for dichotomous variables and for the higher (lower) values of continuous variables. HRs < 1 (> 1) indicate lower (higher) risk for an event for the first category listed for dichotomous variables and for the lower (higher) values of continuous variables. Variables considered in the model were those significant at α = .20 from the univariable models. Variables considered in the models were as follows: for CR, NPM1 (mutated v wild-type), platelets, WBC, and age; for DFS, NPM1 (mutated v wild-type), CEBPA (mutated v wild-type), FLT3-ITD (present v absent), WBC, and race (white v nonwhite); for OS, NPM1 (mutated v wild-type), FLT3-ITD (present v absent), WT1 (mutated v wild-type), platelets, WBC, and race (white v nonwhite). Patients who had both FLT3-ITD and FLT3-TKD present were considered as FLT3-ITD present only for all outcome analyses.

Abbreviations: CR, complete remission; DFS, disease-free survival; OS, overall survival; OR, odds ratio; HR, hazard ratio; FLT3-ITD, internal tandem duplication of the FLT3 gene.

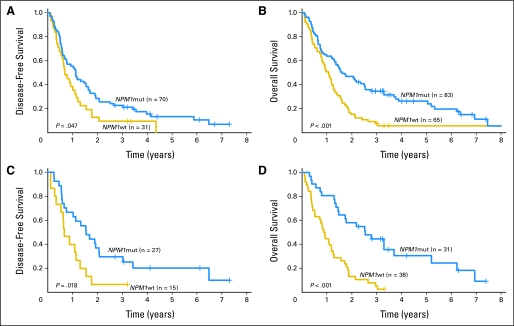

The median follow-up of living patients was 3.5 years (range, 2.3 to 9.7 years). Among patients who achieved CR, those with NPM1 mutations had better DFS (P = .047; 3-year rates, 23% v 10%; Table 2; Fig 1A). In multivariable analyses, NPM1 mutations were independently associated with longer DFS (P = .004), after adjustment for WBC (P = .005) and FLT3-ITD status (P = .012; Table 3).

Fig 1.

(A) Disease-free survival and (B) overall survival of patients age ≥ 60 years with cytogenetically normal de novo acute myeloid leukemia according to NPM1 mutation status. (C) Disease-free survival and (D) overall survival of patients age ≥ 70 years with cytogenetically normal de novo acute myeloid leukemia according to NPM1 mutation status. NPM1mut, NPM1 mutated; NPM1wt, NPM1 wild-type.

NPM1mut patients also had a significantly longer OS compared with NPM1wt patients (P < .001; 3-year rates, 35% v 8%; Table 2; Fig 1B). In multivariable analyses, NPM1 mutations were independently associated with longer OS (P < .001), after adjustment for WBC (P = .008) and FLT3-ITD status (P = .014; Table 3).

Prognostic Impact of NPM1 Mutations by Age Groups

The prognosis of adult patients with AML worsens with increasing age, with patients age ≥ 70 years having a particularly poor outcome.4,7-9,36 Although age on its own was not significantly associated with outcome in our patient set, we observed an interaction between age groups (60 to 69 v ≥ 70 years) and NPM1 mutational status for OS (P = .057). NPM1 mutational status was significant for OS in patients age ≥ 70 years, but not in those age 60 to 69 years. Therefore, we dichotomized the study population into patients age 60 to 69 years (n = 79; median age, 64 years; Appendix Table A2, online only) and those age ≥ 70 years (n = 69; median age, 74 years; Appendix Table A3, online only), and assessed whether the prognostic value of NPM1 mutations differed between the age groups.

In the 60 to 69 years age group, NPM1 mutations were associated with a higher CR rate (83% v 59%; P = .031; Table 2) and remained independent predictors for achievement of CR (P = .017), after accounting for WBC (P = .021; Table 3). However, NPM1 mutations did not significantly affect DFS or OS duration (Tables 2, 3).

In the ≥ 70 years age group, NPM1mut patients also had significantly better CR rates than NPM1wt patients (87% v 39%; P < .001; Table 2), and mutated NPM1 was independently associated with achievement of CR (P < .001), after adjustment for WBC (P = .017; Table 3). In addition, in contrast to patients age 60 to 69 years, those age ≥ 70 years with NPM1 mutations had longer DFS (P = .018; 3-year rates, 30% v 7%; Table 2; Fig 1C) and OS (P < .001; 3-year rates, 45% v 5%; Table 2; Fig 1D) than those with wild-type NPM1. In multivariable analyses, mutated NPM1 was independently associated with longer DFS (P = .003) and OS (P < .001), whereas no other variables remained in the final models (Table 3). NPM1 mutations conferred 69% and 73% reduction in the risk of relapse or death, respectively, compared with wild-type NPM1 (Table 3).

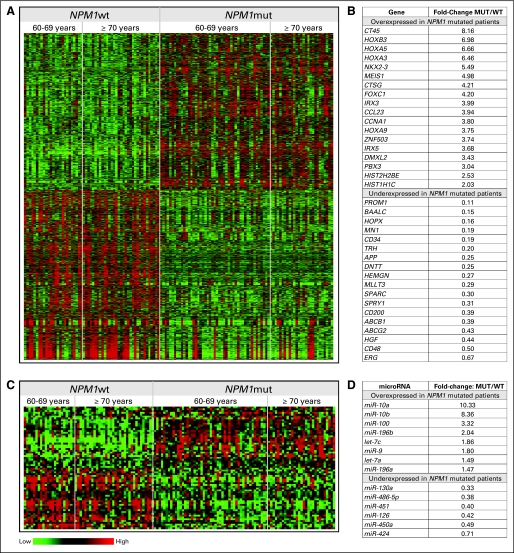

Genome-Wide Gene-Expression Analysis

A gene-expression signature associated with NPM1 mutations was derived from the whole study population, comprising 3,577 probe sets differentially expressed between NPM1mut (n = 74) and NPM1wt (n = 58) patients. A total of 1,719 probe sets corresponding to 912 named genes were upregulated, and 1,858 probe sets corresponding to 969 named genes were downregulated, in NPM1mut patients (Figs 2A, 2B; Data Supplement 1).

Fig 2.

Heat maps of the (A) gene- and (C) microRNA-expression signatures associated with NPM1 mutations in older patients with cytogenetically normal de novo acute myeloid leukemia. Rows represent probe sets (A) or microRNA probes (C), and columns represent patients. Patients are grouped by NPM1 mutational status and ordered by age within these groups. Expression values of the probe sets and microRNA probes are represented by color, with green indicating expression less than, and red indicating expression greater than, the median value for the given probe set or microRNA probe. (B) Fold-changes for selected genes of the signature. Genes are sorted by fold-change in expression between the NPM1mut and NPM1wt groups (MUT/WT). For genes with more than one corresponding probe set in the signature, the geometric mean of the fold-changes of these probe sets is displayed. (D) Fold-changes for selected microRNAs in the signature. MicroRNAs are sorted by fold-change in expression between the NPM1mut and NPM1wt groups (MUT/WT). Fold-change is displayed for those probes hybridizing with the respective mature microRNA. For microRNAs with more than one corresponding probe in the signature, the geometric mean of the fold-changes of these probes is given. Selection of genes and microRNAs is based on the fold-change and previous reports of these genes and microRNAs associated with NPM1 mutations, leukemia, or other malignancies.

Noteworthy features associated with NPM1 mutations were upregulation of HOXA and HOXB genes, HOX cofactors MEIS1 and PBX3, and other genes involved in embryonic development, for example, FOXC1, NKX2-3, IRX3, and ZNF503.37–41 One of the most upregulated probe sets in NPM1mut patients recognizes six members of the CT45 family.42 Other upregulated genes were CTSG, encoding the promyelocyte-specific serine protease cathepsin G 43; CCL23, encoding a protein capable of suppressing myeloid progenitor proliferation 44; CCNA1, the overexpression of which in transgenic mice leads to abnormal myelopoiesis 45; and several histone genes.46

Downregulated in the NPM1mut group were genes whose low expression is associated with better prognosis in CN-AML, that is, BAALC,47,48 MN1,49,50 and ERG,51,52 and multidrug resistance genes ABCB1(MDR1)2 and ABCG2(BCRP).53 Other downregulated genes included APP, which is overexpressed in complex karyotype AML with 21q amplification54; HEMGN, which is upregulated in CN-AML with high ERG expression52; and HGF and CD200, genes reported to adversely affect AML outcome.55,56 Among the most downregulated genes were CD34, PROM1(CD133), and CD48. Also downregulated in the NPM1mut group were DNTT, which is regulated through histone modifications57; HOPX, which mediates transcriptional repression by recruiting histone deacetylase activity58; and SPARC, a gene with low expression in several neoplasms that can be upregulated in myelodysplastic syndromes responsive to lenalidomide.59,60

The expression pattern of genes composing the signature was similar between the subsets of patients age 60 to 69 years and those age ≥ 70 years (Fig 2A). Among the probe sets forming the signature, no significant interaction effects between age group (60 to 69 and ≥ 70 years) and NPM1 mutation status on gene-expression levels were observed.

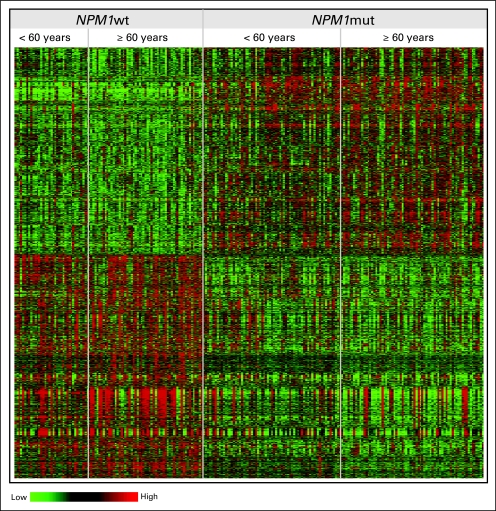

We also tested whether NPM1 mutation status could be predicted using gene-expression profiles. In leave-one-out cross-validated analysis, the mutation status of 89.4% of patients was correctly predicted (sensitivity = 91.9%, specificity = 86.2%; Table 4). Moreover, we applied the predictor derived from the gene-expression signature associated with NPM1 mutations in older patients to a cohort of younger (< 60 years) CALGB patients with CN-AML.50,61 NPM1 mutation status was accurately predicted for 86.3% of these patients (sensitivity= 89.4%, specificity = 80.6%; Table 4), similar to the performance of the predictor in the older cohort. This suggests that the expression patterns of the genes forming the signature associated with NPM1 mutations are age independent (Appendix Fig A1).

Table 4.

Prediction Accuracy of NPM1 Mutation Status of Patients Age ≥ 60 Years and < 60 Years With Cytogenetically Normal De Novo Acute Myeloid Leukemia, Using the Gene-Expression Profile Derived in Patients Age ≥ 60 Years

| Predictor | ≥ 60 years (n = 132) | < 60 years (n = 102) |

|---|---|---|

| Overall accuracy | 89.4% | 86.3% |

| Sensitivity | 91.9% | 89.4% |

| Specificity | 86.2% | 80.6% |

Prediction of NPM1 mutation status by leave-one-out cross-validated analysis using the gene-expression profiles derived in patients age ≥ 60 years with cytogenetically normal de novo acute myeloid leukemia (AML). The same predictor was then applied to a cohort of younger (< 60 years) patients with cytogenetically normal AML. Sensitivity is the probability that gene-expression analysis correctly predicts the presence of NPM1 mutation; specificity is the probability that gene-expression analysis correctly predicts wild-type NPM1.

Genome-Wide MicroRNA-Expression Analysis

We also derived a microRNA-expression signature associated with NPM1 mutations in our cohort of older patients. Sixty-eight microRNA probes were differentially expressed between NPM1mut (n = 78) and NPM1wt (n = 56) patients. Thirty-four microRNA probes were upregulated and 34 downregulated in NPM1mut patients (Figs 2C, 2D; Data Supplement 2).

The prominent feature of the signature associated with NPM1 mutations was upregulation of microRNAs embedded in the HOX cluster: miR-10a, miR-10b, miR-196a and miR-196b.62 Also overexpressed were members of the let-7 family, which target oncogenes RAS and MYC63; miR-100, upregulated in t(15;17)-positive AML64,65; and miR-9, which targets NFκB and can be hypermethylated in cancer.66,67 Downregulated were miR-126, the expression of which we recently positively correlated with MN1 expression in younger patients with CN-AML,50 and miR-130a and miR-451, which are involved in megakaryocytic differentiation and erythropoiesis, respectively.68,69

Similar to the gene-expression signature, the microRNA-expression pattern in the signature was comparable between patients age 60 to 69 years and those age ≥ 70 years (Fig 2C). Among the probes forming the signature, no significant interaction effects between age group and NPM1 mutation status on microRNA-expression levels were observed. Furthermore, NPM1 mutation status could be predicted with a high degree of accuracy on the basis of microRNA-expression profiles. In leave-one-out cross-validated analysis, the mutation status of 92.5% of patients in our cohort was correctly predicted (sensitivity = 96.2%, specificity = 87.5%).

DISCUSSION

CN-AML in older patients is generally associated with poor prognosis, but the reasons why outcome of this age group is worse than that of younger patients, and to what extent prognosis of older patients depends on molecular markers, are largely unknown. In this study, we evaluated the prognostic impact of NPM1 mutations in a relatively large series of patients age ≥ 60 years with de novo CN-AML, treated with intensive chemotherapy, in the context of molecular variables known to affect the outcome of younger patients with CN-AML.12

The incidence of NPM1 mutations at diagnosis and their association with FLT3-ITD, higher WBC, and increased blast percentages in our older patients' cohort were similar to data reported in studies comprising younger patients.13–20 However, in contrast to these studies, in which analyses of NPM1 mutations as a single outcome predictor yielded inconsistent results,13–20 we found that in older CN-AML patients, NPM1 mutations had a favorable prognostic impact independent of other molecular and clinical prognosticators.

We showed that NPM1 mutations were associated with relatively high odds of achieving CR even after adjustment for other predictive variables. These results are consistent with a recent report by Schneider et al,24 although these authors tested the predictive value of NPM1 mutations using only univariable analysis. Importantly, we showed that the CR rate of older CN-AML patients with NPM1 mutations is similar to that observed in younger NPM1mut patients treated in CALGB front-line clinical trials.61 This suggests that NPM1 mutations may represent a marker that can be used to stratify older patients with CN-AML to up-front intensive chemotherapy. More intensive treatment has often been avoided in older patients because of disappointing clinical results and low therapeutic index. However, the favorable outcome associated with NPM1 mutations was even more pronounced in the oldest subgroup (≥ 70 years) of our cohort, thereby emphasizing that older age alone should not exclude patients from more intensive chemotherapy.

We also demonstrated that NPM1 mutations in older patients with CN-AML independently predicted better DFS and OS. The impact of NPM1 mutations on survival of such patients was analyzed in two recent studies.6,25 In a smaller study, Schlenk et al25 reported that relapse-free survival and OS were longer for NPM1mut patients than for those with wild-type NPM1, but only in the absence of FLT3-ITD and only in patients receiving all-trans-retinoic acid in addition to chemotherapy. Similarly, in a study focused on age-related risk profiles, Büchner et al6 evaluated the prognostic value of NPM1 mutations only together with FLT3-ITD mutational status, and showed that patients with NPM1 mutations lacking FLT3-ITD appeared to have longer remission duration and OS than the remaining patients. In contrast to our study, neither of these reports established the prognostic impact of NPM1 mutations as a single marker, evaluated separately patients age ≥ 70 years, or assessed the biologic significance of NPM1 mutations in older patients with CN-AML using gene- and microRNA-expression profiling.

Our subset outcome analyses of patients age 60 to 69 years and those age ≥ 70 years revealed that in the 60 to 69 years group, NPM1 mutations predicted higher CR rates but had no significant impact on survival. In contrast, in the ≥ 70 years group, NPM1 mutations were a strong, independent predictor not only for higher CR rates, but also for longer DFS and OS. To our knowledge, this is the first example of a molecular marker whose favorable prognostic impact seems to become stronger with increased age in adults.

It should be underscored that despite the favorable outcome of older NPM1mut patients compared with that of NPM1wt patients, their DFS and OS remain disappointing and worse than those in younger NPM1mut patients with CN-AML.14–20,61 Whether this is caused by differences in the postremission therapy administered, disease biology, or other age-related factors remains to be established. To gain insight into potential biologic differences associated with age, we performed genome-wide gene- and microRNA-expression analyses. We found that expression of genes in the NPM1 mutation-associated signature appeared similar in both groups of older patients (ie, 60 to 69 and ≥ 70 years). Moreover, the main features of our gene- and microRNA-expression signatures were similar to those reported by other groups in studies comprising mainly younger patients.65,70–72 Indeed, we showed that the gene-expression signature derived from older patients could predict accurately the NPM1 mutation status in younger (18 to 59 years) CALGB patients with CN-AML. Similar gene-expression patterns across the age groups support the notion that NPM1mut CN-AML is a unique biologic entity and that differences in outcome may be related to differences in treatment or the influence of other clinical and molecular factors.

A noteworthy feature of our gene-expression signature associated with NPM1 mutations in older patients was upregulation of homeobox genes, including HOXA and HOXB. This was accompanied by upregulation of miR-10a, miR-10b, miR-196a, and miR-196b, which are colocalized with and target various HOX genes.62 Moreover, consistent with the favorable prognostic impact of NPM1 mutations, the multidrug resistance genes ABCB1(MDR1) and ABCG2(BCRP),2,53 and BAALC, MN1, and ERG, the high expression of which is associated with poor prognosis in CN-AML,47–52 were downregulated in the NPM1mut group. As in our previous study of younger patients with CN-AML,50 a positive correlation between MN1 expression and miR-126 was also observed in the older patients. MiR-126 is reportedly hypermethylated in various neoplasms,64,67 and downregulation of miR-126 increases apoptosis in leukemia cells.64 Finally, in accordance with our recently described signature associated with BAALC expression in younger CN-AML patients,48 CT45 was highly upregulated in the NPM1mut group.

In conclusion, we show that NPM1 mutations constitute a strong, independent prognostic factor for favorable treatment response and survival in older patients with CN-AML treated with intensive chemotherapy. The gene- and microRNA-expression signatures of older NPM1mut CN-AML patients appear similar to those in younger patients, thereby suggesting that CN-AML with NPM1 mutations may be a single entity in all age groups. Future studies should prospectively validate our findings and test whether older patients with CN-AML with NPM1 mutations would benefit from up-front allocation to therapies similar to those received by the younger patients with NPM1 mutations.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

We thank Donna Bucci of the Cancer and Leukemia Group B Leukemia Tissue Bank at Ohio State University Comprehensive Cancer Center, Columbus, OH, for sample processing and storage services, and Lisa J. Sterling and Colin G. Edwards for data management.

Appendix

Participating Institutions

The following Cancer and Leukemia Group B institutions, principal investigators, and cytogeneticists participated in this study: The Ohio State University Medical Center, Columbus, OH: Clara D. Bloomfield, Karl S. Theil, Diane Minka, and Nyla A. Heerema (Grant No. CA77658); Wake Forest University School of Medicine, Winston-Salem, NC: David D. Hurd, Wendy L. Flejter, and Mark J. Pettenati (Grant No. CA03927); University of Iowa Hospitals, Iowa City, IA: Daniel A. Vaena and Shivanand R. Patil (Grant No. CA47642); North Shore–Long Island Jewish Health System, Manhasset, NY: Daniel R. Budman and Prasad R. K. Koduru (Grant No. CA35279); Roswell Park Cancer Institute, Buffalo, NY: Ellis G. Levine and AnneMarie W. Block (Grant No. CA02599); Duke University Medical Center, Durham, NC: Jeffrey Crawford, Mazin B. Qumsiyeh, John Eyre, and Barbara K. Goodman (Grant No. CA47577); University of Chicago Medical Center, Chicago, IL: Hedy L. Kindler, Diane Roulston, Yanming Zhang, and Michelle M. Le Beau (Grant No. CA41287); University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC: Thomas C. Shea and Kathleen W. Rao (Grant No. CA47559); Ft. Wayne Medical Oncology/Hematology, Ft. Wayne, IN: Sreenivasa Nattam and Patricia I. Bader; Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis, MO: Nancy L. Bartlett, Michael S. Watson, Peining Li, and Jaime Garcia-Heras (Grant No. CA77440); Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, MA: Harold J. Burstein, Leonard L. Atkins, Paola Dal Cin, and Cynthia C. Morton (Grant No. CA32291); Eastern Maine Medical Center, Bangor, ME: Harvey M. Segal and Laurent J. Beauregard (Grant No. CA35406); Vermont Cancer Center, Burlington, VT: Hyman B. Muss, Elizabeth F. Allen, and Mary Tang (Grant No. CA77406); University of Massachusetts Medical Center, Worcester, MA: William W. Walsh and Vikram Jaswaney (Grant No. CA37135); Mount Sinai School of Medicine, New York, NY: Lewis R. Silverman and Vesna Najfeld (Grant No. CA04457); University of Puerto Rico School of Medicine, San Juan, PR: Eileen I. Pacheco, Leonard L. Atkins, and Cynthia C. Morton; SUNY Upstate Medical University, Syracuse, NY: Stephen L. Graziano and Constance K. Stein (Grant No. CA21060); Minneapolis VA Medical Center, Minneapolis, MN: Vicki A. Morrison and Sugandhi A. Tharapel (Grant No. CA47555); University of Illinois at Chicago: David J. Peace, Maureen M. McCorquodale, and Kathleen E. Richkind (Grant No. CA74811); University of Nebraska Medical Center, Omaha, NE: Anne Kessinger and Warren G. Sanger (Grant No. CA77298); University of Maryland Cancer Center, Baltimore, MD: Martin J. Edelman and Yi Ning (Grant No. CA31983); Western Pennsylvania Hospital, Pittsburgh, PA: John Lister and Gerard R. Diggans; Dartmouth Medical School, Lebanon, NH: Konstantin Dragnev and Thuluvancheri K. Mohandas (Grant No. CA04326); Georgetown University Medical Center, Washington, DC: Minnetta C. Liu and Jeanne M. Meck (Grant No. CA77597); Long Island Jewish Medical Center CCOP, Lake Success, NY: Kanti R. Rai and Prasad R. K. Koduru (Grant No. CA11028); Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA: Jeffrey W. Clark, Leonard L. Atkins and Cynthia C. Morton (Grant No. CA 12,449); University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN: Bruce A. Peterson and Betsy A. Hirsch (Grant No. CA16450); University of Missouri/Ellis Fischel Cancer Center, Columbia, MO: Michael C. Perry and Tim H. Huang (Grant No. CA12046); Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston, SC: Mark R. Green and Daynna J. Wolff (Grant No. CA03927); Rhode Island Hospital, Providence, RI: William Sikov and Shelly L. Kerman (Grant No. CA08025); Christiana Care Health Services, Newark, DE: Stephen S. Grubbs and Digamber S. Borgaonkar (Grant No. CA45418).

Treatment

Patients enrolled onto CALGB 9720 received induction chemotherapy consisting of cytarabine in combination with daunorubicin and etoposide, with or without the multidrug resistance protein modulator valspodar (PSC 833).10,28 Patients with persistent disease received a second, shorter induction course. Those who achieved complete remission (CR) received a single consolidation course identical to the reinduction regimen and were randomly assigned to low-dose recombinant interleukin-2 maintenance therapy or no therapy. Patients in CALGB 10201 received induction chemotherapy consisting of cytarabine and daunorubicin, with or without the Bcl-2 antisense oligonucleotide oblimersen sodium (Genasense, G3139; Genta, Berkeley Heights, NJ).29 Patients with persistent disease received a second, shorter induction course. The consolidation regimen included two cycles of cytarabine (2 g/m2/d) with or without oblimersen.

Sample Preparation

Patients enrolled onto the treatment protocols were also enrolled onto the companion protocols CALGB 9665 (leukemia tissue bank) and CALGB 20202 (molecular studies in acute myeloid leukemia [AML]), and consented for pretreatment bone marrow (BM) and peripheral-blood collection. Samples were subjected to the Ficoll-Hypaque gradient, and mononuclear cells were cryopreserved until use. Genomic DNA and total RNA sample extraction and quality control of the extracted nucleic acids were performed as reported elsewhere (Calin GA, Sevignani C, Dumitru CD et al: Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101:2999-3004, 2004;33).

Definition of Clinical End Points

CR required an absolute neutrophil count of ≥ 1,500/μL, platelet count of ≥ 100,000/μL, no leukemic blasts in the blood, BM cellularity greater than 20% with maturation of all cell lines, no Auer rods, less than 5% BM blast cells, and no evidence of extramedullary leukemia, all of which had persisted for at least 1 month (Cheson BD, Cassileth PA, Head DR, et al: J Clin Oncol 8:813-819, 1990). Relapse was defined by ≥ 5% BM blasts, circulating leukemic blasts, or the development of extramedullary leukemia. Overall survival (OS) was measured from the date on study until the date of death, and patients alive at last follow-up were censored. Disease-free survival (DFS) was measured from the date of CR until the date of relapse or death; patients alive and relapse free at last follow-up were censored.

Multivariable Models

Multivariable logistic regression models were constructed to analyze factors related to the probability of achieving CR, using a limited backward selection procedure. In addition to NPM1 mutational status, variables that were considered for model inclusion were age, sex, race, hemoglobin, platelet count, WBC, FLT3-ITD (present v absent), FLT3-TKD (present v absent), and CEBPA (mutated v wild-type). Variables considered for inclusion in the logistic models were those significant at α = .20 from the univariable models. Variables remaining in the final models were significant at α = .05.

Multivariable proportional hazards models were constructed for OS and DFS to evaluate the impact of NPM1 mutations by adjusting for other variables, using a limited backward selection procedure. Variables in addition to NPM1 mutational status that were considered for model inclusion were age, sex, race, hemoglobin, platelet count, WBC, FLT3-ITD (present v absent), FLT3-TKD (present v absent), CEBPA (mutated v wild-type), and WT1 (mutated v wild-type). Variables significant at α = .20 from the univariable analyses were considered for multivariable analyses. The proportional hazards assumption was checked for each variable individually. If the proportional hazards assumption was not met for a particular variable, then an artificial time-dependent covariate was included in all models that contained that variable (Klein JP, Moeschberger MP: Survival Analysis: Techniques for Censored and Truncated Data. New York, NY, Springer-Verlag, 1997).

Genome-Wide Gene- and MicroRNA-Expression Analyses

For gene-expression microarrays, summary measures of gene expression were computed for each probe set using the robust multichip average method, which incorporates quantile normalization of arrays. Expression values were logged (base 2) before analysis. A filtering step was performed to remove probe sets that did not display significant variation in expression across arrays. In this procedure, a χ2 test was used to test whether the observed variance in expression of a probe set was significantly larger than the median observed variance in expression for all probe sets using α = .01 as the significance level. A total of 24,437 probe sets passed the filtering criterion. A comparison of gene expression was made between NPM1mut and NPM1wt patients (NPM1mut, n = 74 v NPM1wt, n = 58), using a univariable significance level of .001.

For microRNA microarrays, signal intensities were calculated for each spot, with an adjustment made for local background. Intensities were log-transformed, and log-intensities from replicate spots were averaged. Quantile normalization was performed on arrays using all human and mouse microRNA probes represented on the array. For each microRNA probe, an adjustment was made for batch effects (ie, differences in expression related to the batch in which arrays were hybridized). Further analysis was limited to the 895 unique human probes represented on the array. A comparison of microRNA expression was made between NPM1mut and NPM1wt patients (NPM1mut, n = 78 v NPM1wt, n = 56), using a univariable significance level of .005.

Analyses were performed using BRB-ArrayTools Version 3.8.0 Beta_1 Release (http://linus.nci.nih.gov/BRB-ArrayTools.html), developed by Richard Simon and Amy Peng Lam. For in silico target prediction of microRNAs, the online applications miRBase Targets Version 5 (rebranded as microCosm, available at www.ebi.ac.uk/enright-srv/microcosm/htdocs/targets/v5/) and Targetscan Release 5.0 (www.targetscan.org) were used.

Testing of an Interaction Between Age Group and NPM1 Mutation Status on the Expression Signature

We tested for an interaction between age group (60 to 69 years, ≥ 70 years) and NPM1 mutation status for each probe set and microRNA probe in the gene- and microRNA-expression signature, respectively. We accomplished this by fitting an analysis of variance model with expression of the probe set or microRNA probe as the response variable, and age group, NPM1 mutation status, and age group × NPM1 mutation status interaction as explanatory variables in the model. Interaction effects with a P value less than .001 and .005 were considered significant for probe sets and microRNA probes, respectively.

Prediction of NPM1 Mutation Status From Expression Profiles

We implemented compound covariate prediction using leave-one-out cross-validation to predict NPM1 mutation status of patients from gene- and microRNA-expression profiles (Radmacher MD, McShane LM, Simon R: J Comput Biol 9:505-511, 2002). For gene-expression arrays, each patient was, one at a time, removed from analysis and the expression profiles of the remaining NPM1mut and NPM1wt patients were compared to derive a gene-expression signature. A compound covariate was then computed for each patient on the basis of this signature: the value of the compound covariate for patient i was ci = Σ wj xij, where xij is the log-transformed expression value for probe set j in patient i, and wj is the weight assigned to probe set j (in this case, wj was set equal to the two-sample t statistic for the comparison of the NPM1mut and NPM1wt groups for probe set j). The sum is over all j probe sets included in the signature. A classification threshold was computed to be the midpoint of the means of the compound covariate values for the NPM1mut and NPM1wt groups. The compound covariate was then calculated for the left-out patient, and its NPM1 mutation status was predicted by comparing its value to the classification threshold. This entire process was repeated until every patient had been left out one time and his or her mutation status predicted. The same strategy was used for prediction of mutation status based on microRNA-expression profiles. The overall accuracy of the prediction is indicated, as are the sensitivity and specificity for prediction of NPM1 mutations.

We also tested the ability of the NPM1 mutation–associated gene-expression signature derived from the full set of older patients to predict the mutation status of a set of 102 younger (< 60 years) patients with CN-AML enrolled onto CALGB trial 19808. Gene-expression profiling was performed for these patients as previously reported.48 For each of the 3,577 probe sets that formed the gene-expression signature associated with NPM1 mutations in older patients, we shifted the expression values of the younger patients so that they had the same median value as those of the older patients. We then computed a compound covariate for each younger patient on the basis of the signature in older patients and compared these values to the classification threshold computed for the entire set of older patients in order to predict mutation status of the younger patients.

Fig. A1.

Comparison of the gene-expression signatures associated with NPM1 mutations in younger (< 60 years) and older (≥ 60 years) patients with cytogenetically normal de novo acute myeloid leukemia. The heat map is derived using the 3,577 probe sets that formed the signature in the older cohort. Rows represent probe sets, and columns represent patients. Patients are grouped by NPM1 mutational status and ordered by age within these groups. Expression values of the probe sets are represented by color, with green indicating expression less than, and red indicating expression greater than, the median value for the given probe set.

Table A1.

NPM1 Mutation Types and Their Frequency

| Type | n | % | Nucleotide Change | Amino Acid Change |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 67 | 81 | c.860_863dupTCTG | p.W288CfsX12 |

| B | 4 | 5 | c.863_864insCATG | p.W288CfsX12 |

| D | 3 | 4 | c.863_864insCCTG | p.W288CfsX12 |

| Others | 2 | 3 | c.863_864insTCAG | p.W288CfsX12 |

| Others | 1 | 1 | c.863_864insTATG | p.W288CfsX12 |

| Others | 1 | 1 | c.863_864insCCGA | p.W288CfsX12 |

| Others | 1 | 1 | c.862delinsATTAA | p.W288IfsX12 |

| Others | 1 | 1 | c.869_873 GGAGG>GCCTCGAGA | p.W290CfsX10 |

| Others | 1 | 1 | c.869_873 GGAGG>CCCTAGCCC | p.W290SfsX10 |

| Others | 1 | 1 | c.869_873 GGAGG>GTTTCTCCC | p.W290CfsX10 |

Percentages are calculated from the total number of NPM1 mutations detected in the study population (n = 83). Nucleotide sequences are numbered according to Genebank accession number NM_002520.5. The sequence variations are designated according to the current recommendations of the Human Genome Variation Society (http://www.hgvs.org/mutnomen/). The amino acid changes are theoretically deduced. The more frequent mutation types are designated as A, B, and D (Falini B, Mecucci C, Tiacci E, et al: N Engl J Med 352:254-266, 2005). Other mutation types are indicated as “others.”

Table A2.

Clinical and Molecular Characteristics According to NPM1 Mutation Status of Patients Age 60-69 Years With Cytogenetically Normal De Novo Acute Myeloid Leukemia

| Characteristic | NPM1 Mutated (n = 52) |

NPM1 Wild-Type (n = 27) |

P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | % | No. | % | ||

| Age, years | .38 | ||||

| Median | 64 | 65 | |||

| Range | 60-69 | 60-69 | |||

| Sex | .15 | ||||

| Male | 27 | 52 | 19 | 70 | |

| Female | 25 | 48 | 8 | 30 | |

| Race | .02 | ||||

| White | 51 | 98 | 22 | 81 | |

| Nonwhite | 1 | 2 | 5 | 19 | |

| Performance status* | .32 | ||||

| Fully active (0) | 17 | 33 | 8 | 33 | (0/1 v 2/3/4) |

| Ambulatory (1) | 24 | 47 | 14 | 58 | |

| In bed < 50% of time (2) | 8 | 16 | 2 | 8 | |

| In bed > 50% of time (3) | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | |

| Completely bedridden (4) | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | |

| Hemoglobin, g/dL | .22 | ||||

| Median | 9.4 | 9.1 | |||

| Range | 7.3-12.4 | 6.8-13.6 | |||

| Platelet count, × 109/L | .22 | ||||

| Median | 59 | 88 | |||

| Range | 17-270 | 18-510 | |||

| WBC, × 109/L | .01 | ||||

| Median | 30.9 | 9.5 | |||

| Range | 1.6-165.0 | 1.0-434.1 | |||

| Percentage of PB blasts | .07 | ||||

| Median | 40 | 16 | |||

| Range | 0-96 | 0-89 | |||

| Percentage of BM blasts | .01 | ||||

| Median | 66.5 | 43 | |||

| Range | 18-91 | 15-94 | |||

| FLT3-ITD | .13 | ||||

| Present | 19 | 37 | 5 | 19 | |

| Absent | 33 | 63 | 22 | 81 | |

| FLT3-TKD | .41 | ||||

| Present | 6 | 12 | 1 | 4 | |

| Absent | 42 | 88 | 26 | 96 | |

| WT1 | 1.00 | ||||

| Mutated | 3 | 6 | 1 | 4 | |

| Wild-type | 49 | 94 | 26 | 96 | |

| CEBPA | .08 | ||||

| Mutated | 4 | 8 | 6 | 22 | |

| Wild-type | 48 | 92 | 21 | 78 | |

Abbreviations: PB, peripheral blood; BM, bone marrow; FLT3-ITD, internal tandem duplication of the FLT3 gene; FLT3-TKD, tyrosine kinase domain mutations of the FLT3 gene.

Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group/Zubrod/WHO performance status score.

Table A3.

Clinical and Molecular Characteristics According to NPM1 Mutation Status of Patients Age ≥ 70 Years With Cytogenetically Normal De Novo Acute Myeloid Leukemia

| Characteristic |

NPM1 Mutated n = 31 |

NPM1 Wild-Type n = 38 |

P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | % | No. | % | ||

| Age, years | .96 | ||||

| Median | 74 | 73 | |||

| Range | 71-81 | 70-83 | |||

| Sex | 1.00 | ||||

| Male | 16 | 52 | 20 | 53 | |

| Female | 15 | 48 | 18 | 47 | |

| Race | .40 | ||||

| White | 26 | 87 | 34 | 94 | |

| Nonwhite | 4 | 13 | 2 | 6 | |

| Performance status* | .41 | ||||

| Fully active (0) | 3 | 10 | 10 | 26 | 0/1 v 2/3/4 |

| Ambulatory (1) | 22 | 71 | 17 | 45 | |

| In bed < 50% of time (2) | 6 | 19 | 11 | 29 | |

| In bed > 50% of time (3) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Completely bedridden (4) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Hemoglobin, g/dL | .39 | ||||

| Median | 9.5 | 9.4 | |||

| Range | 6.0-15.0 | 6.5-11.4 | |||

| Platelet count, × 109/L | .85 | ||||

| Median | 60 | 69 | |||

| Range | 20-356 | 11-280 | |||

| WBC, × 109/L | .42 | ||||

| Median | 19.5 | 6.9 | |||

| Range | 1.0-249.3 | 1.0-248.4 | |||

| Percentage of PB blasts | .07 | ||||

| Median | 48.5 | 31.5 | |||

| Range | 0-97 | 0-96 | |||

| Percentage of BM blasts | .27 | ||||

| Median | 66 | 57 | |||

| Range | 11-93 | 7-96 | |||

| FLT3-ITD, no. (%) | .04 | ||||

| Present | 14 | 45 | 8 | 21 | |

| Absent | 17 | 55 | 30 | 79 | |

| FLT3-TKD | 1.00 | ||||

| Present | 4 | 13 | 4 | 11 | |

| Absent | 27 | 87 | 34 | 89 | |

| WT1 | .62 | ||||

| Mutated | 1 | 3 | 3 | 8 | |

| Wild-type | 30 | 97 | 35 | 92 | |

| CEBPA | .45 | ||||

| Mutated | 2 | 6 | 5 | 13 | |

| Wild-type | 29 | 94 | 33 | 87 | |

Abbreviations: PB, peripheral blood; BM, bone marrow; FLT3-ITD, internal tandem duplication of the FLT3 gene; FLT3-TKD, tyrosine kinase domain mutations of the FLT3 gene.

Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group/Zubrod/WHO performance status score.

Footnotes

Supported in part by National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, MD, Grants No. CA101140, CA114725, CA31946, CA33601, CA16058, CA77658, and CA129657; The Coleman Leukemia Research Foundation; and the Deutsche Krebshilfe—Dr. Mildred Scheel Cancer Foundation (H.B.).

Presented in part at the 45th Annual Meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology, Orlando, FL, May 29-June 2, 2009.

Authors' disclosures of potential conflicts of interest and author contributions are found at the end of this article.

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Although all authors completed the disclosure declaration, the following author(s) indicated a financial or other interest that is relevant to the subject matter under consideration in this article. Certain relationships marked with a “U” are those for which no compensation was received; those relationships marked with a “C” were compensated. For a detailed description of the disclosure categories, or for more information about ASCO's conflict of interest policy, please refer to the Author Disclosure Declaration and the Disclosures of Potential Conflicts of Interest section in Information for Contributors.

Employment or Leadership Position: None Consultant or Advisory Role: None Stock Ownership: None Honoraria: None Research Funding: Thomas H. Carter, GeminX Pharmaceuticals Expert Testimony: None Other Remuneration: Thomas H. Carter, Genzyme

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: Heiko Becker, Guido Marcucci, Clara D. Bloomfield

Financial support: Heiko Becker, Guido Marcucci, Michael A. Caligiuri, Clara D. Bloomfield

Administrative support: Michael A. Caligiuri, Richard A. Larson, Clara D. Bloomfield

Provision of study materials or patients: Guido Marcucci, Bayard L. Powell, Thomas H. Carter, Jonathan E. Kolitz, Meir Wetzler, Maria R. Baer, Michael A. Caligiuri, Richard A. Larson, Clara D. Bloomfield

Collection and assembly of data: Heiko Becker, Guido Marcucci, Kati Maharry, Michael D. Radmacher, Krzysztof Mrózek, Susan P. Whitman, Yue-Zhong Wu, Sebastian Schwind, Peter Paschka, Andrew J. Carroll

Data analysis and interpretation: Heiko Becker, Guido Marcucci, Kati Maharry, Michael D. Radmacher, Krzysztof Mrózek, Dean Margeson, Susan P. Whitman, Clara D. Bloomfield

Manuscript writing: Heiko Becker, Guido Marcucci, Kati Maharry, Michael D. Radmacher, Krzysztof Mrózek, Clara D. Bloomfield

Final approval of manuscript: Heiko Becker, Guido Marcucci, Kati Maharry, Michael D. Radmacher, Krzysztof Mrózek, Dean Margeson, Susan P. Whitman, Yue-Zhong Wu, Sebastian Schwind, Peter Paschka, Bayard L. Powell, Thomas H. Carter, Jonathan E. Kolitz, Meir Wetzler, Andrew J. Carroll, Maria R. Baer, Michael A. Caligiuri, Richard A. Larson, Clara D. Bloomfield

REFERENCES

- 1.Ries LAG, Melbert D, Krapcho M, et al. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute; 2008. SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975-2005. http://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2005. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Leith CP, Kopecky KJ, Godwin J, et al. Acute myeloid leukemia in the elderly: Assessment of multidrug resistance (MDR1) and cytogenetics distinguishes biologic subgroups with remarkably distinct responses to standard chemotherapy. A Southwest Oncology Group study. Blood. 1997;89:3323–3329. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Farag SS, Archer KJ, Mrózek K, et al. Pretreatment cytogenetics add to other prognostic factors predicting complete remission and long-term outcome in patients 60 years of age or older with acute myeloid leukemia: Results from Cancer and Leukemia Group B 8461. Blood. 2006;108:63–73. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-11-4354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fröhling S, Schlenk RF, Kayser S, et al. Cytogenetics and age are major determinants of outcome in intensively treated acute myeloid leukemia patients older than 60 years: Results from AMLSG trial AML HD98-B. Blood. 2006;108:3280–3288. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-04-014324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kantarjian H, O'Brien S, Cortes J, et al. Results of intensive chemotherapy in 998 patients age 65 years or older with acute myeloid leukemia or high-risk myelodysplastic syndrome: Predictive prognostic models for outcome. Cancer. 2006;106:1090–1098. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Büchner T, Berdel WE, Haferlach C, et al. Age-related risk profile and chemotherapy dose response in acute myeloid leukemia: A study by the German Acute Myeloid Leukemia Cooperative Group. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:61–69. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.15.4245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Appelbaum FR, Gundacker H, Head DR, et al. Age and acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2006;107:3481–3485. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-09-3724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Estey E. Acute myeloid leukemia and myelodysplastic syndromes in older patients. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:1908–1915. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.10.2731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Juliusson G, Antunovic P, Derolf A, et al. Age and acute myeloid leukemia: Real world data on decision to treat and outcomes from the Swedish Acute Leukemia Registry. Blood. 2009;113:4179–4187. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-07-172007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Baer MR, George SL, Dodge RK, et al. Phase 3 study of the multidrug resistance modulator PSC-833 in previously untreated patients 60 years of age and older with acute myeloid leukemia: Cancer and Leukemia Group B study 9720. Blood. 2002;100:1224–1232. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goldstone AH, Burnett AK, Wheatley K, et al. Attempts to improve treatment outcomes in acute myeloid leukemia (AML) in older patients: The results of the United Kingdom Medical Research Council AML11 trial. Blood. 2001;98:1302–1311. doi: 10.1182/blood.v98.5.1302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mrózek K, Marcucci G, Paschka P, et al. Clinical relevance of mutations and gene-expression changes in adult acute myeloid leukemia with normal cytogenetics: Are we ready for a prognostically prioritized molecular classification? Blood. 2007;109:431–448. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-06-001149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Falini B, Mecucci C, Tiacci E, et al. Cytoplasmic nucleophosmin in acute myelogenous leukemia with a normal karyotype. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:254–266. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa041974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Döhner K, Schlenk RF, Habdank M, et al. Mutant nucleophosmin (NPM1) predicts favorable prognosis in younger adults with acute myeloid leukemia and normal cytogenetics: Interaction with other gene mutations. Blood. 2005;106:3740–3746. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-05-2164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schnittger S, Schoch C, Kern W, et al. Nucleophosmin gene mutations are predictors of favorable prognosis in acute myelogenous leukemia with a normal karyotype. Blood. 2005;106:3733–3739. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-06-2248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Boissel N, Renneville A, Biggio V, et al. Prevalence, clinical profile and prognosis of NPM mutations in AML with normal karyotype. Blood. 2005;106:3618–3620. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-05-2174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Suzuki T, Kiyoi H, Ozeki K, et al. Clinical characteristics and prognostic implications of NPM1 mutations in acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2005;106:2854–2861. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-04-1733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thiede C, Koch S, Creutzig E, et al. Prevalence and prognostic impact of NPM1 mutations in 1485 adult patients with acute myeloid leukemia (AML) Blood. 2006;107:4011–4020. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-08-3167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schlenk RF, Döhner K, Krauter J, et al. Mutations and treatment outcome in cytogenetically normal acute myeloid leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:1909–1918. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa074306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gale RE, Green C, Allen C, et al. The impact of FLT3 internal tandem duplication mutant level, number, size, and interaction with NPM1 mutations in a large cohort of young adult patients with acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2008;111:2776–2784. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-08-109090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Arber DA, Vardman JW, Brunning RD, et al. Acute myeloid leukaemia with recurrent genetic abnormalities. In: Swerdlow SH, Campo E, Harris NL, et al., editors. WHO Classification of Tumours of Haematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues. Lyon, France: IARC; 2008. pp. 110–123. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Falini B, Bolli N, Liso A, et al. Altered nucleophosmin transport in acute myeloid leukaemia with mutated NPM1: Molecular basis and clinical implications. Leukemia. 2009;23:1731–1743. doi: 10.1038/leu.2009.124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Scholl S, Theuer C, Scheble V, et al. Clinical impact of nucleophosmin mutations and Flt3 internal tandem duplications in patients older than 60 yr with acute myeloid leukaemia. Eur J Haematol. 2008;80:208–215. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0609.2007.01019.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schneider F, Hoster E, Unterhalt M, et al. NPM1 but not FLT3-ITD mutations predict early blast cell clearance and CR rate in patients with normal karyotype AML (NK-AML) or high-risk myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) Blood. 2009;113:5250–5253. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-09-172668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schlenk RF, Döhner K, Kneba M, et al. Gene mutations and response to treatment with all-trans retinoic acid in elderly patients with acute myeloid leukemia. Results from the AMLSG Trial AML HD98B. Haematologica. 2009;94:54–60. doi: 10.3324/haematol.13378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Byrd JC, Mrózek K, Dodge RK, et al. Pretreatment cytogenetic abnormalities are predictive of induction success, cumulative incidence of relapse, and overall survival in adult patients with de novo acute myeloid leukemia: Results from Cancer and Leukemia Group B (CALGB 8461) Blood. 2002;100:4325–4336. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-03-0772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mrózek K, Carroll AJ, Maharry K, et al. Central review of cytogenetics is necessary for cooperative group correlative and clinical studies of adult acute leukemia: The Cancer and Leukemia Group B experience. Int J Oncol. 2008;33:239–244. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Baer MR, George SL, Caligiuri MA, et al. Low-dose interleukin-2 immunotherapy does not improve outcome of patients age 60 years and older with acute myeloid leukemia in first complete remission: Cancer and Leukemia Group B study 9720. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:4934–4939. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.17.0472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Marcucci G, Moser B, Blum W, et al. A phase III randomized trial of intensive induction and consolidation chemotherapy ± oblimersen, a pro-apoptotic Bcl-2 antisense oligonucleotide in untreated acute myeloid leukemia patients > 60 years old. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(suppl):360s. abstr 7012. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Thiede C, Steudel C, Mohr B, et al. Analysis of FLT3-activating mutations in 979 patients with acute myelogenous leukemia: Association with FAB subtypes and identification of subgroups with poor prognosis. Blood. 2002;99:4326–4335. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.12.4326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Whitman SP, Ruppert AS, Radmacher MD, et al. FLT3 D835/I836 mutations are associated with poor disease-free survival and a distinct gene-expression signature among younger adults with de novo cytogenetically normal acute myeloid leukemia lacking FLT3 internal tandem duplications. Blood. 2008;111:1552–1559. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-08-107946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Marcucci G, Maharry K, Radmacher MD, et al. Prognostic significance of, and gene and microRNA expression signatures associated with, CEPBA mutations in cytogenetically normal acute myeloid leukemia with high-risk molecular features: A Cancer and Leukemia Group B study. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:5078–5087. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.17.5554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Paschka P, Marcucci G, Ruppert AS, et al. Wilms' tumor 1 gene mutations independently predict poor outcome in adults with cytogenetically normal acute myeloid leukemia: A Cancer and Leukemia Group B study. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:4595–4602. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.15.2058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Calin GA, Liu C-G, Sevignani C, et al. MicroRNA profiling reveals distinct signatures in B cell chronic lymphocytic leukemias. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:11755–11760. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0404432101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Radmacher MD, Marcucci G, Ruppert AS, et al. Independent confirmation of a prognostic gene-expression signature in adult acute myeloid leukemia with a normal karyotype: A Cancer and Leukemia Group B study. Blood. 2006;108:1677–1683. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-02-005538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Peterson BA, Bloomfield CD. Treatment of acute nonlymphocytic leukemia in elderly patients: A prospective study of intensive chemotherapy. Cancer. 1977;40:647–652. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197708)40:2<647::aid-cncr2820400209>3.0.co;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Moens CB, Selleri L. Hox cofactors in vertebrate development. Dev Biol. 2006;291:193–206. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2005.10.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pabst O, Zweigerdt R, Arnold HH. Targeted disruption of the homeobox transcription factor Nkx2-3 in mice results in postnatal lethality and abnormal development of small intestine and spleen. Development. 1999;126:2215–2225. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.10.2215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gómez-Skarmeta JL, Modolell J. Iroquois genes: Genomic organization and function in vertebrate neural development. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2002;12:403–408. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(02)00317-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lehmann OJ, Sowden JC, Carlsson P, et al. Fox's in development and disease. Trends Genet. 2003;19:339–344. doi: 10.1016/S0168-9525(03)00111-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.McGlinn E, Richman JM, Metzis V, et al. Expression of the NET family member Zfp503 is regulated by hedgehog and BMP signaling in the limb. Dev Dyn. 2008;237:1172–1182. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.21508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chen Y-T, Scanlan MJ, Venditti CA, et al. Identification of cancer/testis-antigen genes by massively parallel signature sequencing. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:7940–7945. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0502583102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hanson RD, Connolly NL, Burnett D, et al. Developmental regulation of the human cathepsin G gene in myelomonocytic cells. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:1524–1530. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Patel VP, Kreider BL, Li Y, et al. Molecular and functional characterization of two novel human C-C chemokines as inhibitors of two distinct classes of myeloid progenitors. J Exp Med. 1997;185:1163–1172. doi: 10.1084/jem.185.7.1163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Liao C, Wang XY, Wei HQ, et al. Altered myelopoiesis and the development of acute myeloid leukemia in transgenic mice overexpressing cyclin A1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:6853–6858. doi: 10.1073/pnas.121540098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Marzluff WF, Wagner EJ, Duronio RJ. Metabolism and regulation of canonical histone mRNAs: Life without a poly(A) tail. Nat Rev Genet. 2008;9:843–854. doi: 10.1038/nrg2438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Baldus CD, Tanner SM, Ruppert AS, et al. BAALC expression predicts clinical outcome of de novo acute myeloid leukemia patients with normal cytogenetics: A Cancer and Leukemia Group B study. Blood. 2003;102:1613–1618. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-02-0359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Langer C, Radmacher MD, Ruppert AS, et al. High BAALC expression associates with other molecular prognostic markers, poor outcome, and a distinct gene-expression signature in cytogenetically normal patients younger than 60 years with acute myeloid leukemia: A Cancer and Leukemia Group B (CALGB) study. Blood. 2008;111:5371–5379. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-11-124958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Heuser M, Beutel G, Krauter J, et al. High meningioma 1 (MN1) expression as a predictor for poor outcome in acute myeloid leukemia with normal cytogenetics. Blood. 2006;108:3898–3905. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-04-014845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Langer C, Marcucci G, Holland KB, et al. Prognostic importance of MN1 transcript levels, and biologic insights from MN1-associated gene and microRNA expression signatures in cytogenetically normal acute myeloid leukemia: A Cancer and Leukemia Group B study. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:3198–3204. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.6110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Marcucci G, Baldus CD, Ruppert AS, et al. Overexpression of the ETS-related gene, ERG, predicts a worse outcome in acute myeloid leukemia with normal karyotype: A Cancer and Leukemia Group B study. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:9234–9242. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.6137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Marcucci G, Maharry K, Whitman SP, et al. High expression levels of the ETS-related gene, ERG, predict adverse outcome and improve molecular risk-based classification of cytogenetically normal acute myeloid leukemia: A Cancer and Leukemia Group B study. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:3337–3343. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.10.8720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Benderra Z, Faussat AM, Sayada L, et al. MRP3, BCRP, and P-glycoprotein activities are prognostic factors in adult acute myeloid leukemia. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:7764–7772. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-1895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Baldus CD, Liyanarachchi S, Mrózek K, et al. Acute myeloid leukemia with complex karyotypes and abnormal chromosome 21: Amplification discloses overexpression of APP, ETS2, and ERG genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:3915–3920. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400272101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Verstovsek S, Kantarjian H, Estey E, et al. Plasma hepatocyte growth factor is a prognostic factor in patients with acute myeloid leukemia but not in patients with myelodysplastic syndrome. Leukemia. 2001;15:1165–1170. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2402182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tonks A, Hills R, White P, et al. CD200 as a prognostic factor in acute myeloid leukaemia. Leukemia. 2007;21:566–568. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Su R-C, Brown KE, Saaber S, et al. Dynamic assembly of silent chromatin during thymocyte maturation. Nat Genet. 2004;36:502–506. doi: 10.1038/ng1351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kook H, Lepore JJ, Gitler AD, et al. Cardiac hypertrophy and histone deacetylase-dependent transcriptional repression mediated by the atypical homeodomain protein Hop. J Clin Invest. 2003;112:863–871. doi: 10.1172/JCI19137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.DiMartino JF, Lacayo NJ, Varadi M, et al. Low or absent SPARC expression in acute myeloid leukemia with MLL rearrangements is associated with sensitivity to growth inhibition by exogenous SPARC protein. Leukemia. 2006;20:426–432. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Pellagatti A, Jädersten M, Forsblom A-M, et al. Lenalidomide inhibits the malignant clone and up-regulates the SPARC gene mapping to the commonly deleted region in 5q- syndrome patients. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:11406–11411. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0610477104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Paschka P, Marcucci G, Maharry K, et al. Prognostic impact of NPM1 mutations in cytogenetically normal (CN) acute myeloid leukemia (AML) is adversely affected by high expression of ERG gene: A Cancer and Leukemia Group B (CALGB) study. Haematologica. 2007;92(suppl 1):145. abstr 396. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Yekta S, Tabin CJ, Bartel DP. MicroRNAs in the Hox network: An apparent link to posterior prevalence. Nat Rev Genet. 2008;9:789–796. doi: 10.1038/nrg2400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Büssing I, Slack FJ, Großhans H. Let-7 microRNAs in development, stem cells and cancer. Trends Mol Med. 2008;14:400–409. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2008.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Li Z, Lu J, Sun M, et al. Distinct microRNA expression profiles in acute myeloid leukemia with common translocations. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:15535–15540. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0808266105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Jongen-Lavrencic M, Sun SM, Dijkstra MK, et al. MicroRNA expression profiling in relation to the genetic heterogeneity of acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2008;111:5078–5085. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-01-133355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Bazzoni F, Rossato M, Fabbri M, et al. Induction and regulatory function of miR-9 in human monocytes and neutrophils exposed to proinflammatory signals. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:5282–5287. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0810909106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Lujambio A, Calin GA, Villanueva A, et al. A microRNA DNA methylation signature for human cancer metastasis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:13556–13561. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0803055105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Garzon R, Pichiorri F, Palumbo T, et al. MicroRNA fingerprints during human megakaryocytopoiesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:5078–5083. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0600587103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Masaki S, Ohtsuka R, Abe Y, et al. Expression patterns of microRNAs 155 and 451 during normal human erythropoiesis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2007;364:509–514. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.10.077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Verhaak RGW, Goudswaard CS, van Putten W, et al. Mutations in nucleophosmin (NPM1) in acute myeloid leukemia (AML): Association with other gene abnormalities and previously established gene expression signatures and their favorable prognostic significance. Blood. 2005;106:3747–3754. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-05-2168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Alcalay M, Tiacci E, Bergomas R, et al. Acute myeloid leukemia bearing cytoplasmic nucleophosmin (NPMc+ AML) shows a distinct gene expression profile characterized by up-regulation of genes involved in stem-cell maintenance. Blood. 2005;106:899–902. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-02-0560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Garzon R, Garofalo M, Martelli MP, et al. Distinctive microRNA signature of acute myeloid leukemia bearing cytoplasmic mutated nucleophosmin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:3945–3950. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0800135105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.