Abstract

Purpose

In 2001, the National Cancer Institute (NCI) formed the Central Institutional Review Board (CIRB) to conduct a single human subjects review for its multisite phase III oncology trials. The goal of this study was to assess whether NCI's CIRB was associated with lower effort, time, and cost in processing adult phase III oncology trials.

Methods

We conducted an observational study and compared sites affiliated with the NCI CIRB to unaffiliated sites that used their local IRB for review. Oncology research staff and IRB staff were surveyed to understand effort and timing. Response rates were 60% and 42%, respectively. Analysis of these survey data yielded information on effort, timing, and costs. We combined these data with CIRB operational data to determine the net savings of the CIRB using a societal perspective.

Results

CIRB affiliation was associated with faster reviews (33.9 calendar days faster on average), and 6.1 fewer hours of research staff effort. CIRB affiliation was associated with a savings of $717 per initial review. The estimated cost of running the CIRB was $161,000 per month. The CIRB yielded a net cost of approximately $55,000 per month from a societal perspective. Whether the CIRB results in higher or lower quality reviews was not assessed because there is no standard definition of review quality.

Conclusion

The CIRB was associated with decreases in investigator and IRB staff effort and faster protocol reviews, although savings would be higher if institutions used the CIRB as intended.

INTRODUCTION

For the past 40 years, organizations have used institutional review boards (IRBs) to oversee research involving human subjects. Most research organizations have their own institutionally based IRB (a local IRB), and multisite trials need IRB approvals for each site. Variation in how local IRBs review the same research protocol have led to delays and additional costs for multisite clinical trials.1–4 Some researchers have advocated for a re-evaluation of our human subjects protections,5 with one option being a central IRB (CIRB) for multisite research.

Federal regulations permit the use of a central IRB, and commercial IRBs that serve as the single IRB for multisite trials have operated since the late 1960s. In 2001, the National Cancer Institute (NCI) created a CIRB for its phase III oncology trials.6 Originally, the CIRB was limited to adult trials, but a second CIRB was eventually added to review pediatric trials.

In this study, we investigated the effort and timing associated with NCI's adult CIRB. In addition, we estimated costs and determined whether savings in local research and IRB effort offset the cost of the CIRB, resulting in a net savings from a societal perspective.

METHODS

Background on the CIRB

The NCI developed the Clinical Trials Cooperative Group Program in 1955 to conduct studies of chemotherapy. Over time, the cooperative group program expanded in scope and it now includes 10 cooperative groups that design and run clinical trials to evaluate new anticancer treatments. More than 1,700 institutions enroll approximately 25,000 patients annually onto clinical trials conducted by these groups.

NCI's Cancer Therapy Evaluation Program (CTEP), in collaboration with the cooperative groups, developed the CIRB for adult, multisite, phase III cancer treatment clinical trials in 2001. CTEP worked with the Office of Human Research Protections to ensure that the CIRB would adhere to all of the regulatory requirements.

Institutions that are interested in using the CIRB must meet basic requirements as listed on the CIRB Web site (www.ncicirb.org) and sign an authorization agreement. After the CIRB, which maintains expertise in medical oncology, pharmacology, bioethics, and biostatistics, reviews and approves the study protocol, the protocol is distributed to all of the sites interested in enrolling patients onto the protocol. Sites that are not enrolled with the CIRB must have their local IRB conduct a full board review as they would with any research study. Sites enrolled with the CIRB have their local IRB conduct a facilitated review, a new review category. This process involves the local IRB chairperson or a small subcommittee of the full IRB reviewing the recommendations of the CIRB posted on the CIRB Web site (ie, a facilitated review). If these reviewers are satisfied, then they can accept the CIRB as the IRB of record for this particular protocol. Minor alterations are permitted to tailor the informed consent document for the local context. However, if the local IRB is not satisfied with the CIRB's review, they can conduct their own full board review and assume all responsibilities. If the local IRB accepts the facilitated review, then the CIRB assumes full responsibility for handling continuing reviews, amendments, and serious adverse event (SAE) reports, with the sole exception being SAEs that occur at the local site. These latter SAEs must still be reported to the local IRB by the investigator.

Study Design

We used a case-control framework. Institutions enrolled with the CIRB adult board were classified as cases and all others were classified as controls. We used an intent-to-treat approach that classified sites according to whether or not they used the CIRB at all, without respect to whether they used it precisely as intended (ie, did not review amendments or continuing reviews) or whether they always accepted the facilitated review. In the discussion, we highlight the potential savings if these sites used the CIRB as intended. Our study protocol was approved by the Stanford University IRB.

To assess the NCI CIRB, we developed surveys to ask research and IRB staff about the timing of reviews and the effort involved. After pilot testing at CIRB member and nonmember sites, and receiving input from an advisory panel, we conducted the surveys to assess timing and effort, and used the results in an economic model to assess the net cost of the CIRB. A technical appendix describes the survey methods in more detail and the surveys are available on request.

For the research staff survey, we sent an invitation to 574 study coordinators to participate in a web survey. Seventy-six emails were returned as undeliverable, and of the remaining 498, 300 completed the survey (60% response rate). Nonrespondents were not significantly different than respondents in terms of CIRB enrollment or the volume of initial reviews, continuing reviews, and amendments that they oversaw. Missing data prevented some responses from being used; a total of 253 cases were included in the final analytic data set.

For the IRB staff survey, we sent surveys to reviewers at 120 willing IRBs, and followed up with three e-mail reminders. A total of 50 respondents (42%) completed the survey. A nonresponse analysis was not possible with this sample as many respondents were anonymous.

Analysis

For hours of effort, we used linear regression to determine if there was an association with CIRB enrollment, controlling for the respondents' educational level. For elapsed time, which is a count of calendar days, we used negative binomial regression to determine if there was an association with CIRB enrollment, controlling for the respondents' educational level.7 We used robust SEs, which are valid in the presence of heteroskedasticity.8

We also tested whether CIRB enrollment was associated with decreased variability in timing, which would indicate that the timing is more predictable. We assessed variability using a likelihood ratio test for groupwise heteroskedasticity.9 Analyses of survey data were conducted in Stata version 9.2 (Stata Corp, College Station, TX).

We estimated the cost of operating the adult CIRB using billing data from NCI's contractor. All costs were based on 2008 dollars. We conducted a number of additional analyses to determine if the results were sensitivity to the analytic methods. We tried log-linear models and we checked for cases with extreme leverage using Cooks distance. For analyses with the research staff data, the sample size was large enough to permit including a random effect for the protocol (ie, the clinical trial identifier). The results were robust; at no point in the analysis did the β coefficient for CIRB enrollment reverse (eg, from expediting research to slowing research down).

For the net cost analysis, the survey data yielded the marginal savings per initial review for researchers and IRB staff. We combined this point estimate with data from Cancer Trial Support Unit on the total number of reviews for CIRB and non-CIRB sites. Cancer Trial Support Unit provided 27 months of data, permitting an overall analysis as well as a monthly analysis. We compared the marginal savings of the CIRB with the monthly cost of running the CIRB in Excel (Microsoft Corp, Redmond, WA). We used an indirect to direct cost ratio of 33%, which was governmental indirect rate reported by Arthur Andersen.10 We then varied the indirect rate ±10 percentage points in the sensitivity analysis.

RESULTS

Research Staff

Table 1 shows the sample characteristics of the research staff respondents. The prototypical respondent was a study coordinator with a nursing background. There were no statistically significant differences in respondent's education and role between sites that used the CIRB and those that did not.

Table 1.

Sample Characteristics for Research and IRB Staff

| Characteristic | % |

P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| CIRB | Non-CIRB | ||

| Research staff | |||

| Education | .905 | ||

| Masters or more | 16.0 | 16.7 | |

| Nurse | 35.0 | 31.4 | |

| BA/BS | 19.0 | 24.5 | |

| Other* | 13.0 | 11.8 | |

| Missing | 17.0 | 15.7 | |

| Role | .907 | ||

| PI | 2.0 | 1.0 | |

| Study coordinator | 76.0 | 79.2 | |

| RA | 16.0 | 14.9 | |

| Other | 6.0 | 5.0 | |

| IRB staff | |||

| Respondent education | .221 | ||

| PhD, MD, PharmD, JD | 20.7 | 52.4 | |

| RN | 13.8 | 9.5 | |

| MA/MS | 6.9 | 4.8 | |

| BA | 13.8 | 4.8 | |

| Other or missing | 44.8 | 28.6 | |

| Respondent role | .01 | ||

| Chair | 12.5 | 46.7 | |

| Committee member | 12.5 | 33.3 | |

| Office director | 16.7 | 6.7 | |

| Coordinator | 58.3 | 13.3 | |

| Less than 5 years experience | 17.2 | 14.3 | .778 |

Abbreviations: CIRB, central institutional review board; PI, principal investigator; RA, research assistant; IRB, institutional review board.

Includes less than college; specialty certifications; and other entries, such as years of experience.

Initial reviews took an average of 7.9 hours for CIRB sites, which was significantly less than the 14 hours of average effort reported by non-CIRB sites (Table 2). There were no significant differences for continuing reviews and amendments. In all but one case, the maximums were considerably higher for the sites that did not use the CIRB, and there was significantly more variability with the local IRBs. On average, CIRB sites reported that the local facilitated review took 13.1 calendar days between submission and approval, compared with 35.5 days for the full board review from non-CIRB sites. Overall, from the date the research staff started the paperwork until IRB approval, it took 28.3 days for CIRB sites and 62.3 days for non-CIRB sites (P = .04).

Table 2.

Effort, Elapsed Time, and Costs for Research Staff

| Parameter | Site Uses CIRB |

Site Uses Local IRB |

Average Diff | Adjusted P | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | Mean | SD | Max | No. | Mean | SD | Max | |||

| Effort in hours | ||||||||||

| Initial review* | 58 | 7.9 | 7.0 | 40.5 | 37 | 14.0 | 13.9 | 71.0 | 6.1 | .02 |

| Post initial review | 47 | 0.3 | 1.0 | 5.3 | 65 | 0.6 | 1.9 | 10 | 0.3 | .20 |

| Continuing review | 20 | 0.4 | 1.3 | 5.3 | 35 | 0.7 | 1.9 | 9.2 | 0.2 | .44 |

| Amendment* | 27 | 0.2 | 0.8 | 4.0 | 30 | 0.6 | 2.0 | 10.0 | 0.5 | .30 |

| Elapsed time in calendar days | ||||||||||

| Initial review | ||||||||||

| Started paperwork to submission* | 46 | 16.6 | 23.8 | 89.0 | 30 | 25.3 | 33.9 | 127.0 | 8.7 | .18 |

| Submission date to approval date* | 38 | 13.1 | 14.0 | 59.0 | 28 | 35.5 | 67.2 | 253.0 | 22.4 | .07 |

| Total: paperwork to approval date* | 38 | 28.3 | 24.2 | 104.0 | 28 | 62.3 | 83.3 | 317.0 | 33.9 | .02 |

| Continuing review: submission to approval* | 20 | 18.1 | 15 | 52 | 30 | 17.4 | 25 | 92 | −0.7 | .62 |

| Amendment: submission to approval* | 26 | 18 | 21 | 88 | 30 | 14.2 | 17 | 66 | −3.8 | .25 |

| Costs | ||||||||||

| Initial review* | 58 | 380 | 392 | 2144 | 37 | 622 | 597 | 2957 | 241.7 | .04 |

| Post initial review | 48 | 11.1 | 47.3 | 297 | 65 | 24.5 | 76.6 | 387 | 13.4 | .27 |

| Continuing review* | 21 | 19.2 | 67 | 297 | 35 | 23.9 | 72 | 387 | 4.7 | .64 |

| Amendment* | 27 | 4.81 | 23 | 120 | 30 | 25.3 | 83 | 350 | 20.4 | .26 |

NOTE. All P values use robust standard errors to correct for groupwise heteroskedasiticy. Adjusted P values for effort and cost control for respondent role and education and include a protocol random effect. Adjusted P value for time uses a negative binomial model that controls for respondent role and education.

Abbreviations: IRB, institutional review board; CIRB, central institutional review board; SD, standard deviation; Max, maximum; Diff, difference.

Evidence of groupwise heteroskedasticity P < .01.

The estimated direct cost for the research staff to obtain an initial review was $380 for CIRB sites and $622 for non-CIRB sites (a difference of $241.7). Costs for continuing review were considerably less than the initial review and were not statistically different between the two groups. The difference of $241.7 is direct costs only. With the organization's overhead, the total savings was $321 per initial review.

IRB Staff

IRB staff spent an average of 3.9 hours conducting an initial review of a NCI protocol at non-CIRB sites. At CIRB sites, the initial review, which is called a facilitated review, took 1.6 hours on average. The difference between CIRB and non-CIRB sites was marginally significant (Table 3). Time estimates include the time spent by IRB coordinators and reviewers. This is a conservative estimate; time spent discussing the protocol in committee was included, but we did not ask how many people were in the committee meeting and multiply this number by the time estimate.

Table 3.

Effort and Costs for IRB Staff

| Parameter | Site Uses CIRB |

Site Uses Local IRB |

Average Diff | Adjusted P | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | Mean | SD | Max | No. | Mean | SD | Max | |||

| Effort in hours | ||||||||||

| Initial review | 6 | 1.6 | 1.9 | 4.0 | 5 | 3.9 | 2.1 | 7.0 | 2.3 | 0.108 |

| Post initial review | 17 | 2.0 | 2.1 | 7.0 | 10 | 3.0 | 2.9 | 9.0 | 1.0 | 0.145 |

| Continuing review | 13 | 2.1 | 2.4 | 7.0 | 3 | 3.1 | 1.8 | 4.3 | 1.0 | 0.509 |

| Amendment | 4 | 1.4 | 0.7 | 2.1 | 8 | 2.5 | 2.2 | 6.5 | 1.2 | 0.108 |

| Adverse avent reports | 29 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.4 | 21 | 0.2 | 0.4 | 1.4 | 0.2 | 0.068 |

| Direct costs | ||||||||||

| Initial review | 6 | 91.1 | 94.4 | 240.0 | 5 | 388.7 | 219.2 | 559.0 | 297.7 | 0.014 |

| Post initial review | 17 | 106.0 | 147.2 | 525.0 | 10 | 254.1 | 257.3 | 838.5 | 148.1 | 0.070 |

| Continuing review | 13 | 113.3 | 164.7 | 525.0 | 3 | 276.0 | 245.1 | 559.0 | 162.7 | 0.315 |

| Amendment | 4 | 82.6 | 78.2 | 193.5 | 8 | 214.2 | 261.1 | 838.5 | 131.5 | 0.238 |

| Adverse event reports | 29 | 1.8 | 4.8 | 21.0 | 21 | 12.4 | 26.5 | 104.8 | 10.7 | 0.074 |

NOTE. Adjusted P values for costs control for respondent role and education and include a protocol random effect.

Abbreviations: IRB, institutional review board; CIRB, central institutional review board; SD, standard deviation; Max, maximum; Diff, difference.

Time spent reviewing amendments and continuing reviews was lower, on average, at CIRB sites than non-CIRB sites. Fewer respondents reported on this information; individually, differences for amendments and continuing reviews were not statistically significant. Taken together, they were marginally significant (P = .070). CIRB sites that accept the CIRB as the IRB of record do not have to review amendments, continuing reviews, or adverse event reports, unless they elect to conduct these reviews or they rejected the CIRB review. Two CIRB sites (6.9%) reported rejecting the CIRB review in the past year (following intent to treat principles, these sites remained CIRB sites). CIRB sites spent less time handling adverse event reports than non CIRB sites, and this difference was marginally significant.

Estimated direct costs for the initial review were $297.7 less at CIRB sites than non-CIRB sites (Table 3). This difference was statistically significant, and more significant than reported hours of effort, indicating that CIRB sites use less expensive staff to conduct these reviews than non-CIRB sites. Indirect costs were an additional $98, yielding a total cost of $396.

Net Cost Analysis

Each CIRB site that conducts an initial review saves $717, of which $321 was related to research staff savings the remaining $396 was associated with IRB staff savings. According to our calculations (technical appendix), the average monthly cost of running the adult CIRB was approximately $161,000. The ability of the CIRB to save money, in a societal perspective, depends on the number of initial reviews conducted by the CIRB. Operational data show that each CIRB site processes several initial reviews per month, and when combined, all of the CIRB sites process an average of 147 initial reviews per month. Multiplying the number of initial reviews per month by the marginal savings per review, and then subtracting the cost of running the CIRB, indicated that the CIRB was associated with a net cost of approximately $55,000 per month under the most conservative estimates. If we assume that the administrative costs of running the CIRB are proportional to direct costs, then the net cost is approximately $14,000.

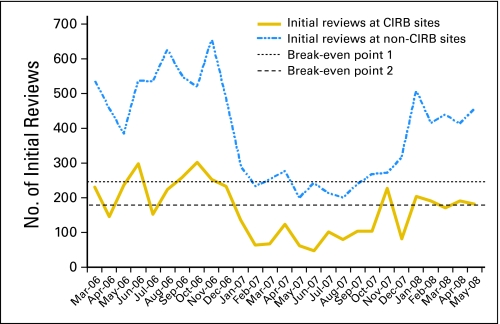

CIRB sites handled an average of 147 initial reviews per month. Figure 1 shows the volume of initial reviews by month. If the number of initial reviews at CIRB sites increased to 246 (break-even point 1), then the CIRB would break even under the most conservative calculations. If we assume the administrative cost of operating the CIRB are proportional to the direct costs, the break-even point is 178 initial reviews per month (break-even point 2). This break-even calculation only focuses on savings related to the initial review.

Fig 1.

Break-even calculations for Central Institutional Review Board (CIRB) between March 2006 and May 2008, showing the number of initial reviews at CIRB and non-CIRB sites between March 2006 and May 2008. The horizontal dashed lines represent thresholds above which the CIRB had a net savings. The top dashed line assumes that all of the administrative costs of operating the adult and pediatric CIRB are borne by the adult CIRB. The bottom dashed line assumes adult and pediatric CIRBs share the administrative costs.

DISCUSSION

The CIRB was associated with a total savings of $717 per initial review. About half of this was associated with time savings for research staff and the remainder was associated with savings for the IRB staff. Given the substantial number of NCI protocols reviewed by some local sites, the savings was notable, but it did not exceed the cost of operating the CIRB, resulting in a net cost of approximately $55,000 per month from a societal perspective. In addition to the economic savings, the CIRB was associated with faster and more predictable (ie, less variable) review times. We did not attempt to value the opportunity cost of faster and more predictable reviews, but many sponsors value faster and more predictable reviews and are willing to pay to use private central IRBs.11

The current structure requires the CIRB to review and approve the protocol before it is sent to the sites. In this study, we tracked effort and timing once the protocol was sent to the local sites. Some have suggested that parallel processing might be faster, because the approval process for phase III trials is lengthy and complex.12,13 These data cannot speak to whether parallel processing would be faster. These results, while encouraging for proponents of the CIRB, do not provide insights on whether the system is operating efficiently or optimally. Some sites used the CIRB as intended, and this resulted in faster processing, as has also been noted in a single site study.14 However, IRBs at a number of CIRB sites reported spending time on amendments and continuing reviews, even though the regulations allow this responsibility to be delegated to the CIRB. If we rerun our analysis assuming that CIRB sites used the CIRB as intended, the CIRB would save a considerable amount of money ($125,000 per month), largely because CIRB sites handle approximately 428 continuing reviews per month. This suggests that saving money with the CIRB may be possible, even if this requires spending more money on outreach and the CIRB help desk.

There are a number of limitations to this study that should be considered. This study evaluated the NCI CIRB, and some issues and processes are idiosyncratic to its structure and the operation of phase III oncology trials. Another limitation is the reliance on self-report data. Pilot testing indicated that asking about the most recent complete protocol would lead to more accurate information than asking about a specific protocol because this minimizes memory decay associated with a lengthy recall period.15 We were able to develop a sampling frame for the investigator survey, but collecting data from IRB staff proved to be challenging. Many IRBs were willing to participate in our study, but asked us to send them the survey and they would forward it to the appropriate reviewer. We sent three reminders, but ultimately we had a lower response rate with the IRB survey than the investigator survey.

Other limitations involve analytic assumptions. The billing data from the contractor that runs the CIRB included work on the adult and pediatric CIRBs. In our primary calculations, we assumed that all of the technical and administrative support was borne by the adult CIRB and that the pediatric CIRB required no technical or administrative support. This is a very conservative assumption. Changing this assumption resulted in lower net cost of $14,000 per month. This assumption proved to have a large effect on the cost calculations; varying other input parameters, such as salaries, did not alter the results as much. The net savings analysis also depended on the number of initial reviews conducted by CIRB sites. If the NCI budget does not permit as many trials in the future, then this will affect the net savings associated with the CIRB. Finally, we excluded from the net cost calculation any review fees charged by local IRBs. It is unclear if sites using commercial IRBs would be charged less when the CIRB is utilized. However, if they were, there could be additional net savings for the local institution.

According to standards,16 start-up costs should be excluded. The CIRB started in 2001, and many of the kinks were worked out of the system by the time this study started. However, just before our study, the main contractor changed and the new contractor may have had some start-up costs. In addition, the CIRB continues to enroll new sites and these new sites can encounter start-up costs. We had no explicit way of removing these start-up costs and if they exist, they would make the CIRB look more expensive.

In conclusion, the review at sites using the NCI CIRB was associated with less effort and faster reviews when compared to non-CIRB sites. The effects were statistically significant for initial reviews, leading to a cost savings of approximately $717 per initial review for each site involved in a multisite study. Overall, the analysis suggests that the CIRB yields a net cost of approximately $55,000 per month for the NCI's cooperative group clinical trials program. This calculation is based solely on the effort of the initial reviews. Benefits of a more predictable and faster approval process are not included in this calculation but clearly they have a benefit. Efforts to expand enrollment in the CIRB and to encourage sites to use the CIRB, as intended, for continuing, amendment, and adverse event reviews could result in administrative inefficiencies, but based on prior research,17 increased efficiencies and net savings are likely.

Acknowledgment

We benefitted from an advisory panel (Erica Heath, Jon Merz, Jeffrey Braff, and Marisue Cody) and research assistance from Cherisse Harden and Nicole Flores. Finally, we benefited from discussions with Angela Bowen and Western Institutional Review Board staff.

Appendix

Research staff survey.

The sampling frame for the research staff survey was study coordinators for National Cancer Institute (NCI) -sponsored phase III oncology trials. NCI's Cancer Trial Support Unit (CTSU) provided contact information for each local site involved in a phase III adult oncology trial between March 2006 and March 2007. We sent emails to 574 study coordinators inviting them to participate in a web survey. Seventy-six emails were returned as undeliverable, and of the remaining 498, 300 completed the survey (60% response rate). We sent three reminders to nonrespondents, and participation was encouraged by a support letter from the American Society for Clinical Oncology.

We conducted a nonresponse analysis using the data provided by CTSU. For this analysis, we excluded the 76 coordinators whose emails were returned as undeliverable. Nonrespondents were not significantly different than respondents in terms of CIRB enrollment or the volume of initial reviews, continuing reviews, and amendments that they oversaw.

For study coordinators who opened the survey, the first page included a consent form and confirmed that the person worked on NCI-sponsored phase III adult oncology trials. The survey then asked about the last NCI phase III trial on which they received an IRB approval and the type of approval (initial, continuing, or amendment). After identifying the type of approval, skip logic in the survey directed people to questions specific to the review they indicated. The questions asked about submission and approval dates, whether the IRB asked for clarification or changes, and effort. For dates, we asked for the date they started to complete the paperwork, the date they first submitted the paperwork, the date they heard back from the IRB, and the date the protocol was approved. We included probes to help improve recall of the dates (eg, “When did the IRB approve the protocol? The exact date would be very helpful to us. It should be on the approval letter.”) The survey is available on request.

For the questions on effort, we asked the respondent to report on their own effort (in hours and minutes), and then in a second series of questions we asked about other researchers involved in the IRB protocol and the amount of time they spent.

We estimated the dollar value of staff effort using unit wages from salary.com based on the person's title and their educational level. For example, the salary for a study coordinator with a nursing degree was $63,631 and the salary for a study coordinator with a bachelor's degree was $47,053 (Appendix Table A1). To these salary estimates, we added 30% for benefits and then calculated an hourly wage by dividing the total by 2088. We allowed for variation in wages by simulating estimates 1,000 times using a normal distribution and information on wage variation provided by salary.com. Facility and administrative costs (ie, organizational overhead) were included based on an adjusted indirect to direct cost ratio of 33%.6

Respondents were asked to provide information on the IRB they use, whether their IRB used the NCI CIRB for adult oncology trials and some background information (role and education). If they did not know if their IRB used the CIRB, then we linked their IRB name with the list of CIRB enrolled institutions (www.ncicirb.org). Missing data prevented some responses from being used; a total of 253 cases were included in the final analytic data set.

IRB staff survey.

The sampling frame for the IRB staff survey was IRB reviewers who review NCI-sponsored phase III oncology trials. There is no existing database that provides contact information consistent with this sampling frame. We identified eligible participants using a combination of methods and databases. The CTSU provided information on the study coordinators and the research site. We also obtained the Office of Human Subjects Protection list of Federalwide Assurance approved institutions and their IRBs. We merged these two databases. This data merge is imperfect for a number of reasons. Organizations must update their Office of Human Research Protections data periodically, and some information can be out of date. Second, organizations can use an internal IRB for some protocols and contract with an external IRB for other protocols. Finally, none of these data sets provide information on who in the IRB office reviewed the protocol.

We randomized the merged data and used the Office of Human Research Protections contact numbers to contact the IRB. In some cases, we attempted to find updated information using internet search engines. Our goal was 60 respondents. We contacted each IRB by phone, explained our study, and that our objective was to survey IRB staff who reviews NCI-sponsored oncology trials. In some cases, the IRB provided this person's information over the phone. In other cases, they asked us to send them the link to the survey and they forwarded it on to the appropriate person. At the end of our study, we sent surveys to 120 IRB staff members who expressed willingness to complete the survey, and followed up with three e-mail reminders. A total of 50 respondents (42%) completed the survey. A nonresponse analysis was not possible with this sample as many respondents were anonymous.

The survey asked questions about the respondent's role (chair, committee member, administrative, or other) and effort on the last NCI phase III oncology trial initial review, continuing review, and amendment. Respondents also provided information on whether their site used the NCI CIRB for adult trials.

We estimated dollar value of IRB staff effort based on salary data for IRB professionals from Public Responsibility in Medicine and Research (PRIMR). The annual salary for IRB chairs (mostly physicians), committee members, IRB directors, and IRB coordinators was: $188,546, $109,620, $87,000, and $51,156, respectively. To these salary estimates, we added an additional 30% for staff benefits, and then calculated an hourly wage by dividing the total by 2088. We allowed for variation in wages by simulating estimates 1,000 times using a normal distribution and information on wage variation provided by PRIMR. Indirect costs were included at a rate of 33%.6

CIRB cost data.

NCI contracts with an external organization to run the CIRB. The contractor provided us with staff labor hours for them and their subcontractors for 2007 and the first 6 months of 2008. The contractor's labor hours were provided by staff member by month. Job titles were provided for each staff member.

We estimated national salaries by linking job title to salary information from salary.com for administrative/technical job titles and PRIMR salary data for IRB professionals (Appendix Tables A1 and A2). We added an additional 30% for benefits. We allowed for variation in wages by simulating estimates 1,000 times using a normal distribution and information on wage variation provided by salary.com and PRIMR. The contractor provided us with billing invoices to validate our cost analyses, but we agreed not to disclose these data to safeguard the contractor's competitive status.

From the labor data, we were able to exclude staff who provided direct support to NCI's pediatric CIRB, as this study was limited to the adult CIRB. However, the majority of the labor hours were for administrative/technical support to both boards. We assumed that all of the administrative and technical support is needed for the adult board. This is analogous to assuming that the pediatric board has no marginal cost and this generates the most conservative (ie, most expensive) estimate. An alternative method would involve an assumption of proportionality—that is, the administrative support is in proportion to the amount of adult board support relative to pediatric board support. Because the adult board receives approximately twice the support of the pediatric board, assuming proportionality would assign that two thirds of the administrative costs are to the adult board. For the main analysis, discussed below, we used the most conservative assumption and used the proportionality assumption in a sensitivity analysis.

Savings per initial review.

We analyzed the survey data to determine effort and costs for the initial review, continuing review, and amended reviews. In these regression models, the β coefficient on enrollment with the CIRB, our key independent variable, was the marginal savings associated with being enrolled with the CIRB. Because the savings for the continuing reviews and amendments was not significant, we did not include these parameters in the net savings analysis or the break even analysis.

Net savings analysis and break even analysis.

We combined the annual cost of the CIRB from the CIRB cost analysis, described above, with the annual savings for all of the initial reviews conducted by CIRB enrolled institutions. We calculated the annual savings by multiplying the savings per initial review, from the statistical analysis, by the number of initial reviews conducted by CIRB enrolled institutions in a year. The NCI CTSU provided us with information on the number of IRB reviews per month from March 1, 2006, to May 31, 2008.

The net savings analysis is an aggregate analysis for 1 year. We also analyzed the data by month. The overall result from this analysis is consistent with the net savings analysis. However, it also provides monthly information for benchmarking purposes.

Table A1.

Salary Estimates Used in the Calculations

| Job Title | Estimate Title/Source | Estimated Costs |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 25% ($) | 75% ($) | Base ($) | Base With Benefits ($) | SD | ||

| Project director | Project director* | 89,854 | 125,246 | 52 | 67 | 9 |

| Deputy project manager | Project manager* | 86,048 | 110,228 | 47 | 61 | 12 |

| Portal systems admin | Web software developer* | 59,562 | 82,762 | 34 | 44 | 5 |

| Integration developer | Integration engineer* | 59,159 | 73,392 | 32 | 41 | 6 |

| Technical analyst | Business systems analyst II* | 56,652 | 72,791 | 31 | 40 | 8 |

| QA director | Business systems analyst II* | 56,652 | 72,791 | 31 | 40 | 8 |

| Documentation specialist | Documentation specialist* | 46,773 | 63,270 | 26 | 34 | 6 |

| Help desk | Help desk* | 39,734 | 50,611 | 22 | 28 | 4 |

| Project support | Help desk* | 39,734 | 50,611 | 22 | 28 | 4 |

| Project support specialist | Help desk* | 39,734 | 50,611 | 22 | 28 | 4 |

| IRB admin | PRIMR salary survey | 45,000 | 75,000 | 22 | 28 | 17 |

| IRB coordinator | PRIMR salary survey* | 45,000 | 75,000 | 22 | 28 | 17 |

| Administrative assistant | Administrative assistant I* | 31,977 | 40,837 | 17 | 23 | 3 |

Abbreviations: SD, stable disease; QA, quality assurance; IRB, institutional review board; PRIMR, Public Responsibility in Medicine and Research.

Source was salary.com unless noted otherwise.

Table A2.

Monthly Data in the Break-Even Analysis

| Date and Year | Central Institutional Review Board |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Not Enrolled |

Enrolled |

|||||

| Initial Reviews | Continuing Reviews | Amendments | Initial Reviews | Continuing Reviews | Amendments | |

| March 2006 | 536 | 402 | 427 | 231 | 131 | 63 |

| April 2006 | 454 | 751 | 424 | 146 | 179 | 47 |

| May 2006 | 383 | 886 | 109 | 236 | 622 | 134 |

| June 2006 | 537 | 930 | 39 | 299 | 390 | 17 |

| July 2006 | 535 | 957 | 255 | 152 | 88 | 28 |

| August 2006 | 625 | 815 | 192 | 223 | 376 | 25 |

| September 2006 | 549 | 1,051 | 89 | 258 | 708 | 24 |

| October 2006 | 519 | 860 | 49 | 301 | 824 | 88 |

| November 2006 | 654 | 963 | 39 | 252 | 718 | 27 |

| December 2006 | 481 | 927 | 30 | 233 | 774 | 11 |

| January 2007 | 289 | 866 | 28 | 136 | 387 | 55 |

| February 2007 | 233 | 625 | 12 | 64 | 249 | 2 |

| March 2007 | 252 | 749 | 50 | 68 | 359 | 7 |

| April 2007 | 277 | 847 | 50 | 123 | 124 | 77 |

| May 2007 | 199 | 899 | 123 | 61 | 159 | 83 |

| June 2007 | 241 | 902 | 153 | 48 | 143 | 120 |

| July 2007 | 212 | 968 | 46 | 101 | 428 | 4 |

| August 2007 | 200 | 1,039 | 62 | 80 | 682 | 27 |

| September 2007 | 238 | 791 | 109 | 103 | 499 | 7 |

| October 2007 | 267 | 1,095 | 73 | 104 | 227 | 8 |

| November 2007 | 271 | 1,087 | 243 | 228 | 670 | 57 |

| December 2007 | 314 | 719 | 48 | 81 | 252 | 127 |

| January 2008 | 507 | 1,146 | 16 | 204 | 421 | 7 |

| February 2008 | 414 | 869 | 93 | 190 | 784 | 27 |

| March 2008 | 438 | 1,078 | 224 | 171 | 278 | 134 |

| April 2008 | 412 | 1,175 | 463 | 191 | 501 | 133 |

| May 2008 | 454 | 1,128 | 226 | 181 | 603 | 36 |

Footnotes

Supported by the National Cancer Institute.

Presented at the National Cancer Institute Oncology Group Chairs meeting, September 19, 2008 and to seminar participants at the University of California San Francisco.

Authors' disclosures of potential conflicts of interest and author contributions are found at the end of this article.

All of the conclusions are the authors' own and do not necessarily reflect those of the Department of Veterans Affairs, Standford University, or the National Cancer Institute.

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The author(s) indicated no potential conflicts of interest.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: Todd H. Wagner, Jacquelyn Goldberg, Jeanne M. Adler, Jeffrey Abrams

Financial support: Todd H. Wagner, Jacquelyn Goldberg, Jeanne M. Adler, Jeffrey Abrams

Administrative support: Todd H. Wagner, Christine Murray, Jacquelyn Goldberg, Jeffrey Abrams

Provision of study materials or patients: Todd H. Wagner, Christine Murray, Jacquelyn Goldberg, Jeanne M. Adler

Collection and assembly of data: Todd H. Wagner, Christine Murray

Data analysis and interpretation: Todd H. Wagner, Christine Murray

Manuscript writing: Todd H. Wagner, Christine Murray, Jacquelyn Goldberg, Jeanne M. Adler, Jeffrey Abrams

Final approval of manuscript: Todd H. Wagner, Christine Murray, Jacquelyn Goldberg, Jeanne M. Adler, Jeffrey Abrams

REFERENCES

- 1.Humphreys K, Trafton J, Wagner TH. The cost of institutional review board procedures in multicenter observational research. Ann Intern Med. 2003;139:77. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-139-1-200307010-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shah S, Whittle A, Wilfond B, et al. How do institutional review boards apply the federal risk and benefit standards for pediatric research? JAMA. 2004;291:476–482. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.4.476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hirshon JM, Krugman SD, Witting MD, et al. Variability in institutional review board assessment of minimal-risk research. Acad Emerg Med. 2002;9:1417–1420. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2002.tb01612.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bennett CL, Sipler AM, Parada JP, et al. Variations in institutional review board decisions for HIV quality of care studies: A potential source of study bias. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2001;26:390–391. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200104010-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burman WJ, Reves RR, Cohn DL, et al. Breaking the camel's back: Multicenter clinical trials and local institutional review boards. Ann Intern Med. 2001;134:152–157. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-134-2-200101160-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Christian MC, Goldberg JL, Killen J, et al. A central institutional review board for multi-institutional trials. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:1405–1408. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200205023461814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cameron AC, Trivedi PK. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press; 1998. Regression Analysis of Count Data. [Google Scholar]

- 8.White H. A heteroskedasticity-consistent covariance matrix estimator and a direct test for heteroskedasticity. Econometrica. 1980;48:817–838. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Greene WH. Econometric Analysis. ed 4. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice-Hall; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Andersen AL. Chicago, IL: Prepared for the Government-University-Industry Research Roundtable of the National Academy of Sciences, National Academy of Engineering, and the Institute of Medicine; 1996. The Costs of Research: Examining Patterns of Expenditures Across Research Sectors. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Saillot J-L. Costs, Timing, and Loss of Revenue: Industry Sponsor's Perspective. Presented at Alternative Ways to Organize IRBs, sponsored by OHRP and AAMC; November 20, 2006; Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dilts DM, Sandler AB, Baker M, et al. Processes to activate phase III clinical trials in a cooperative oncology group: The case of Cancer and Leukemia Group B. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:4553–4557. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.7819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dilts DM, Sandler A, Cheng S, et al. Development of clinical trials in a cooperative group setting: The Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:3427–3433. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-5060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hahn K. Measuring IRB efficiency: Comparing the use of the National Cancer Institute central IRB to local IRB methods. Socra Source. 2009:49–52. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bhandari A, Wagner T. Self-reported utilization of health care services: Improving measurement and accuracy. Med Care Res Rev. 2006;63:217–235. doi: 10.1177/1077558705285298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gold MR, Siegel JE, Russell LB, et al., editors. Cost-Effectiveness in Health and Medicine. Oxford, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wagner TH, Cruz AM, Chadwick GL. Economies of scale in institutional review boards. Med Care. 2004;42:817–823. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000132395.32967.d4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]